Abstract

Vitamin E, as all-rac α-tocopheryl-acetate (TAc), has a bioavailability of only 5.4% in swine and, therefore, is a poor vitamin E source. Tocopheryl-phosphate (TP) has been used successfully as a vitamin E source around 1940 but it was subsequently replaced by TAc as it was easier to manufacture. Recently, it has been proposed as an in vivo intermediate in vitamin E metabolism with possibly gene-regulatory functions. TP may be more bioavailable than TAc as intestinal hydrolysis and emulsification are not required. The objective of this work was to compare the bioavailability of TAc and TP in swine. Piglets (18.6 ± 0.6 kg) fitted with jugular catheters received a single test meal (350 g) containing either deuterated (trimethyl-d9) TAc or TP (75 IU/kg body weight, n = 8 per treatment). Twelve serial blood samples were obtained starting premeal until 78 h postmeal for analysis of deuterated T and TP using LC MS/MS. Results were standardized by dividing them by the dose per kg body weight and were subsequently modeled with a multicompartment model. T from TAc had a slow appearance rate (0.040 ± 0.014 h−1) and rapid disappearance rate (0.438 ± 0.160 h−1) with a plateau value of 0.414 ± 0.129 µM/(µmol/kg BW). TP appeared faster in plasma (0.119 ± 0.058 h−1, P = 0.01) while the elimination rate was similar (0.396 ± 0.098 h−1, P = 0.51). The plateau value of TP was only numerically higher (0.758 ± 0.778 µM/(µmol/kg BW), P = 0.34). TP was quickly converted to T; its appearance rate was 0.026 ± 0.009 h−1, slower than the appearance rate of T from TAc (P = 0.01), whereas the elimination rate was 0.220 ± 0.062 h−1, slower than that of T from TAc (P = 0.00). The conversion of TP to T may have been incomplete, as its plateau value was only 0.315 ± 0.109 µM/(µmol/kg BW). The area under the curve, expressed relative to area under the curve for T from TAc, was 34.5% for TP and 107.3% for T from TP. These data confirm that TP is more quickly absorbed than T from TAc. TP is also converted to T and thus a functional precursor of T. Nevertheless, as a source of T, TP failed to offer a clear advantage over TAc in bioavailability.

Keywords: bioavailability, plasma kinetics, swine, α-tocopherol, tocopheryl-phosphate, vitamin E

INTRODUCTION

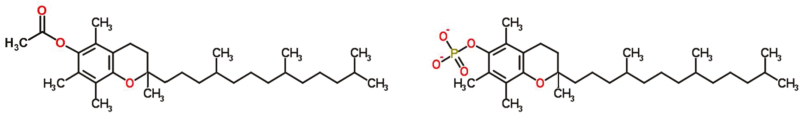

Vitamin E is a lipid-soluble antioxidant in vivo and is routinely supplemented into livestock diets. The form used most commonly is all-rac α-tocopheryl acetate (TAc; Figure 1). α-Tocopherol (T) is acetylated for stability, whereas chemical synthesis results in a racemic blend. Both steps, however, negatively affect the biological value of TAc relative to RRR-T. Desmarchelier et al. (2013) showed that TAc is only partially hydrolyzed to T in the intestines, whereas Jensen and Lauridsen (2007) showed that the non-natural isomers were actively metabolized. Bruno et al. (2006) also showed that the absorption of RRR α-TAc was compromised in low-fat diets. Previously, we showed that bioavailability of TAc was only 5.4% in swine (van Kempen et al., 2016).

Figure 1.

α-Tocopheryl-acetate (TAc, left), α-tocopheryl phosphate (TP, right) (Chemspider).

Early in the history of vitamin E supplementation, all-rac α-tocopheryl-phosphate (TP; Figure 1) was used (Govier and Gibbons, 1949). Although an effective vitamin E form, TP was difficult to synthesize as its production is strongly exothermic (West, 2000). More recently, there has been renewed interest in TP as it has been detected in vivo, and as it has been implicated in gene regulation (Ogru et al., 2003). Azzi (2007) claimed that TP is the true functional form of vitamin E through its gene regulation. The polarity of TP means that it can directly be absorbed and transferred into the blood, which could well translate into a better bioavailability.

The objective of this experiment was to compare the bioavailability of TP with the industry-standard TAc in piglets. For this study, blood T profiles from piglets that consumed a single meal containing TAc were compared with T and TP profiles from piglets that received a single meal of TP. Deuterated forms were used to uniquely track the test materials.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal care procedures were approved by the University of Utrecht Animal Ethics Committee (2014.III.06.056).

Test Materials

Deuterated (trimethyl-d9) TAc was purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Zwijndrecht, NL). TP was custom synthesized by Chiroblock (Bitterfeld-Wolfen, Germany) using the D9-TAc. The procedure for the custom synthesis was derived from the work of Lamb and Lamb (2006). In brief, D9-TAc was hydrolyzed to D9-T. To synthesize D9-TP, the D9-T was reacted first with pyridine, subsequently reacted with phosphorus oxychloride, and lastly alkalized with sodium hydroxide which results in the precipitation of α-TP, disodium salt. The identity of the test product was verified using mass spectroscopy and 1H-NMR.

Animals and Treatments

Healthy intact female piglets (n = 16, Hypor x Maxter breed) were selected at weaning (24 d of age with an average BW of 8.0 ± 0.6 kg) and subsequently adapted to a diet containing TAc at 75 IU/kg (75 mg/kg) and 6% fat. The TAc used was synthetic vitamin E oil adsorbed onto silica for a final concentration of TAc of 50%. Diets were formulated in line with commercial practices (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Ingredient composition of the experimental diet

| Ingredient | g/kg |

|---|---|

| Barley | 350 |

| Wheat | 200 |

| Maize | 132 |

| Wheat bran | 40 |

| Soybean meal Brazil | 100 |

| Potato protein Protamyl | 30 |

| Enzymatically processed soy protein | 61.7 |

| Soybean oil | 38.8 |

| DL-Methionine 99% | 1.36 |

| L-Lysine HCl 98% | 4.86 |

| L-Threonine 98% | 1.61 |

| L-Tryptophan 98% | 1.19 |

| L-Valine 96.5% | 0.46 |

| Na bicarbonate | 4.32 |

| Ca carbonate | 11.3 |

| Monocalcium phosphate | 5.92 |

| Choline chloride | 0.30 |

| Salt (NaCl) | 3.11 |

| Sugar | 3.00 |

| Vitamin E 50% adsorbatea | 1.50 |

| Piglet premix (without vit. E)b | 10.0 |

| Phytase (Phyzyme XP 5000 TPT) | 0.10 |

aNot included in the test meal.

bThe premix contributed per kg feed: 8000 IU vit. A, 2000 IU vit. D3, 1.5 mg vit. K3, 1 mg thiamine, 4 mg riboflavin, 1 mg pyridoxine, 20 µg vit. B12, 20 mg niacin, 12 mg panthothenic acid, 0.31 mg folic acid, 150 mg choline-chloride, 1 mg I (KI), 0.3 mg Se (Na2SeO3), 100 mg Fe (FeSO4.H2O), 160 mg Cu (CuSO4.5H2O), 30 mg Mn (MnO), and 100 mg Zn (ZnSO4.H2O).

Table 2.

Analyzed nutrient content of the experimental diet (as-fed basis)

| Nutrient | g/kg |

|---|---|

| DM | 894 |

| CP | 176 |

| Ether extract | 61 |

| Crude fiber | 42 |

| Ash | 46 |

| Vitamin Ea | 0.106 |

Methods used: DM = EU 152/2009 appendix IIIA; CP = NEN-EN-ISO 16634-1 (Dumas); Ether extract = EU 152/2009, appendix IIIH method A; Crude fiber = NEN-EN-ISO 6865; Ash = EU 152 L54/50 26Feb2009; Vitamin E: NEN-EN 12822. Analyses were carried out in an ISO17025 certified lab.

1Analyzed in the adaptation feed.

Eleven days before the start of the experiment (45 d of age), piglets were housed individually in 1.55 m2 pens and adapted to twice daily meal feeding at the rate of 350 g/meal. Midway during this period, they were catheterized in the jugular vein by inserting a needle into the vein, through which the catheter was inserted as described previously (van Kempen et al., 2016). On day −1, the evening meal was withheld to assure that animals were hungry the next morning so that the test meal would be consumed within a brief period. Animals averaged 18.6 ± 0.6 kg BW on day −1 at 55 d of age.

On day 0, immediately before the test meal, a time 0 blood sample was obtained. Subsequently, animals received the experimental diet with the supplemental vitamin E (75 IU/kg) replaced with an equivalent amount of either D9-TAc (76.4 mg/kg) or D9-TP (as the disodium salt, 88.4 mg/kg). Nonconsumed feed was removed after 30 min and weighed for determination of actual feed intake for each animal.

The time of providing the test feed was set as time 0 (with 2 min between animals). Subsequently, jugular blood samples were taken at 1, 1.5, 2.25, 3.42, 5.25, 8, 13, 23, 32, 48, and 78 h. These time points were chosen, based on our previous studies (van Kempen et al., 2016) as they are useful to describe plasma T appearance/disappearance when D9-Tac is administered. Blood samples (approximately 8 mL) were collected in 9-mL EDTA-containing tubes; plasma was isolated after centrifugation for 10 min at 2000 g and 4 °C and then stored at −80 °C.

Vitamin E Analysis

For the extraction and analysis of both deuterated and nondeuterated T from plasma (for both treatment groups), the procedure of Speek (1989) was used as described in van Kempen et al., (2016).

TP Analysis

For the extraction of both deuterated and nondeuterated TP, plasma samples were acidified with acetic acid and subsequently extracted using acetonitrile. To quantify TP, this extract was analyzed using a Phenomenex Synergi 4µ MAX-RP 250 x 4.60 mm column (Utrecht, NL) on a Thermo Endura LC MS/MS (Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization Source; APCI) with an Ultimate 3000 pump and auto sampler (Waltham, MA, USA). The elution buffer was a blend of 70% water containing 0.025% NH3 and 30% acetonitrile changing linearly over a period of 6 min to 20% water containing 0.025% NH3 and 80% acetonitrile at which ratio it was kept for 1 additional min, followed by a 5-min re-equilibration using the starting conditions. The limit of detection was 3 nM, whereas the limit of quantification was 6 nM.

Data Analysis

For each animal, the actual amount of test material consumed was calculated in µmol/kg BW (averaging 2.88 µmol/kg BW across all animals). Concentration data were subsequently divided by the amount consumed on a BW basis to obtain standardized data: (µM measured)/(µmol consumed/kg BW). Standardized data were modeled with pharmacokinetic equations using scheduled sample collection times, as deviations between actual and scheduled were minor. It was planned to use a single-phase model that incorporated a lag phase to allow for eating time and gastric emptying, as per van Kempen et al., 2016. This model, though, failed to yield error estimates for the TP group. Instead, a multicompartment model from the work of Dhanoa et al. (1985) was used as a basis:

where A is the plateau, Ka is the appearance rate, Ke is the elimination rate, and N is the number of compartments (effectively a lag parameter).

This model is a simplification of an N-compartment model in which 2 compartments are dominant. Dhanoa et al. (1985) used this model for predicting fecal excretion rather than plasma concentrations. Consequently, K1 in the original equation was replaced with Ka (rate of appearance), and K2 with Ke (rate of disappearance). N effectively acts as a lag factor but in contrast to the lag model used earlier, it allows for a gradual and thus more physiological appearance.

This model was modified by including the term [1+d1*parameter modifier for TP-fed animals] for each parameter; d1 (dummy1) was 1 for animals that received TP, and 0 for control. The parameter modifier was used to test if parameters were significantly (P < 0.05) different between the 2 treatments.

Models were fitted using SAS JMP Pro 13.0 (Cary, NC, USA) using piglet as a group parameter. Modeled data were integrated from 0 to 240 h with a step of 0.1 h for calculation of the area under the curve (AUC). For AUC, there is consequently no error measure or statistical comparison possible.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Test meal intake averaged 338 ± 17 g, and animals gained on average 0.28 kg/d between days 1 and 3 without any treatment effect (P = 0.71).

Plasma appearance and disappearance of D9-T and D9-TP showed typical appearance/disappearance curves (Figure 2). Some variability is seen between animals and between time points; this variation is in line with expectations. For D9-TP, few time points were collected on the downward part of the curve and from 48 h onwards data are effectively zero, which likely explains why these data were harder to model (below). Data could be modeled well with the model modified after Dhanoa et al. (1985) (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Top: plasma profiles for D9-T of animals fed D9-TAc. Middle: plasma profiles for D9-TP of animals fed D9-TP. Bottom: plasma profiles for D9-T of animals fed D9-TP. Lines with markers: individual animal data (each line is one animal). Bold line without markers: average across animals. Standardized data are µM/(µmol/kg BW).

Figure 3.

LSmeans ± SD and modeled responses for D9-T from animals fed D9-TAc, or D9-T and D9-TP from animals fed D9-TP. Data used for modeling are in µM/(µmol/kg BW.

As expected, D9-T from D9-TAc had a very slow appearance into circulation (0.040 ± 0.014 h−1) when compared with D9-TP (0.119 ± 0.058 h−1, P = 0.01, Table 3). Likely, this is because the D9-T is transported through the lymph before entering the blood stream while TP can be absorbed directly into the blood stream. Elimination rate of D9-T from D9-TAc, however, again is quick (0.438 ± 0.160 h−1, equating to a half-life of 1.58 h), in line with our earlier work (van Kempen et al., 2016). The elimination rate for D9-T from D9-TP is similar to the elimination rate of D9-T from D9-TAc (0.396 ± 0.098 h−1, P = 0.51). Plasma values of D9-T from D9-TAc peaked at 9.5 h, compared with 8.6 h for D9-TP and 18.7 h for D9-T from D9-TP.

Table 3.

Parameters describing the plateau (A), plasma appearance (Ka), and plasma elimination (Ke) kinetics as well as the area under the curve (AUC) based on modeled plasma responses

| Parameter | D9-T from D9-TAc (1) | D9-TP from D9-TP (2) | D9-T from D9-TP (3) | P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | SD | Estimate | SD | Estimate | SD | 1 vs. 2 | 1 vs. 3 | |

| A (plateau) | 0.414 | 0.129 | 0.758 | 0.778 | 0.315 | 0.109 | 0.34 | 0.11 |

| N | 6.388 | 1.817 | 6.644 | 1.064 | 7.021 | 1.720 | 0.74 | 0.56 |

| Ka | 0.040 | 0.014 | 0.119 | 0.058 | 0.026 | 0.009 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Ke | 0.438 | 0.160 | 0.396 | 0.098 | 0.220 | 0.062 | 0.51 | 0.00 |

| Half-life | 1.58 | 1.75 | 3.15 | |||||

| AUC/(AUC for D9-T from D9-TAc) | 100.0 | 34.5 | 107.3 | |||||

A = plateau (µM/(µmol/kg BW)), N = number of compartments (lag factor), Ka = appearance rate (h-1), Ke = elimination rate (h-1), half-life (h), AUC (%) = area under the curve, based on modeled data extrapolated to 240 h.

D9-TP had a plateau value that was numerically nearly twice the plateau value of D9-T from D9-TAc (0.758 ± 0.778 vs. 0.414 ± 0.129 h−1, P = 0.34). This difference, however, failed statistical significance, likely because the D9-TP curve was difficult to fit as blood sampling points had been optimized for D9-T from D9-TAc; in hindsight, we should have had additional time points during the first 48 h of the experiment. This numeric difference implies a better bioavailability for D9-TP, but this will require verification. The area under the curve for D9-TP, however, was only 34.5% of that obtained with D9-T from D9-TAc.

D9-T obtained from dietary D9-TP appeared slower into the circulation than D9-T from D9-TAc (0.026 ± 0.009 vs. 0.040 ± 0.014 h−1, P = 0.01). A slow lymph stream is likely not the cause here, but the intermediate step in which TP is converted into T. Our data suggest that this conversion occurred systemically, likely in the liver, because TP was measured first in the bloodstream and because its disappearance from the bloodstream appeared to match the appearance of T from TP.

The elimination rate of D9-T from D9-TP was 0.220 ± 0.062 h−1 equating to a half-life of 3.15 h, which is double that of D9-T from D9-TAc (1.58; P = 0.00). We can only speculate why this difference exists. D9-T from D9-TAc reached a 1.5-fold higher blood concentration which could have induced a more rapid catabolism. However, as the D9-T was only 20% to 30% of the total blood content of unlabeled T at its peak, it is unlikely that the supplementation had a strong inductive effect on catabolism. A more likely explanation is that D9-T is formed from D9-TP in tissues, likely the liver, from which it is slowly released back into circulation, increasing its half-life.

The AUC based on modeled data was effectively the same (+7.3%) for D9-T from D9-TP and for D9-T from D9-TAc. This implies that TP is equally effective as TAc as a precursor of circulating T, which contrasted with expectations. TAc has a compromised bioavailability because the hydrolysis of its acetyl-group is incomplete (Desmarchelier et al., 2013). In addition, because T is lipophilic absorption is poor in animals fed low-fat diets (Bruno et al., 2006). Indeed, numerically, a 2-fold higher (P = 0.34) plateau value was observed with TP, but possibly the conversion of D9-TP into D9-T is not 100% complete as the plateau value and the area under curve for D9-T from D9-TP were effectively identical to those of D9-T from D9-TAc. Based on the data from Bruno, TP may well become a more interesting vitamin E source when fat contents in feed drop below 6% or when gut health perturbs fat digestion. In contrast, when dietary fat content increases, the use of TP likely becomes less attractive.

Unlabeled (native) T averaged 3.2 µM (Figure 4), which is in line with earlier findings (Michiels et al., 2013; Prévéraud et al. 2015; van Kempen et al., 2016). In contrast to earlier work, no significant time effect was observed.

Figure 4.

Effect of treatment on unlabeled tocopherol (T). No significant time (P = 0.33) nor treatment (P = 0.86) effect was observed.

Unlabeled TP, measured at time 0, averaged 5.8 ± 2.9 nM. This value is notably lower than what Ogru et al. (2003) found and used in subsequent (disputed) work but of the same order of magnitude as the 28 ± 19 nM in man reported by Zingg et al. (2010), roughly 1/1000th the concentration of T. These data indicate that TP is quantitatively not an important form of tocopherol in plasma, but it is not possible to draw any conclusions as to its biological effects.

In conclusion, these data suggest that, based on plateau values, TP may well have a higher bioavailability than T from TAc by a factor of 2 (P = 0.34). The plateau value observed for T derived from TP, however, was similar to the plateau value for T from TAc implying that there is an inefficiency in the conversion of TP into T. Based on the area under the curve, which likely is the most relevant comparison, nearly identical values were obtained for T from TAc and T from TP (+7.3%). Hence, TP is equally effective as a source of T in healthy swine fed a diet containing 6% fat, despite it being a water-soluble compound that can be directly absorbed into the blood stream.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jean-Baptiste Daniel for his input in the models used for data analysis.

Footnotes

Employed by Trouw Nutrition (premix producer) where the study was performed.

Received financial support for research from DSM.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

T.v.K. and M.G.T. involved in the design of study, data interpretation; M.H.R. in tocopherol analysis; T.v.K. in data analysis, lead author; C.d.B. in trial management. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

LITERATURE CITED

- Azzi A. 2007. Molecular mechanism of alpha-tocopherol action. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 43:16–21. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruno R. S., Leonard S. W., Park S. I., Zhao Y., and Traber M. G.. 2006. Human vitamin E requirements assessed with the use of apples fortified with deuterium-labeled alpha-tocopheryl acetate. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 83:299–304. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.2.299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmarchelier C., Tourniaire F., Prévéraud D. P., Samson-Kremser C., Crenon I., Rosilio V., and Borel P.. 2013. The distribution and relative hydrolysis of tocopheryl acetate in the different matrices coexisting in the lumen of the small intestine during digestion could explain its low bioavailability. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 57:1237–1245. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201200720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhanoa M. S., Siddons R. C., France J., and Gale D. L.. 1985. A multicompartmental model to describe marker excretion patterns in ruminant faeces. Br. J. Nutr. 53:663–671. doi:10.1079/BJN19850076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govier W. M., and Gibbons A. J.. 1949. Alpha-tocopherol, alpha-tocopheryl phosphate, and phosphorylation mechanisms. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 52:163–166. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1949.tb55264.x [Google Scholar]

- Jensen S. K. and Lauridsen C.. 2007. Alpha-tocopherol stereoisomers. Vitam. Horm. 76:281–308. doi: 10.1016/S0083-6729(07)76010-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb R., and Lamb C. S.. 2006. Vitamin E phosphate/phosphatidylcholine liposomes to protect from or ameliorate cell damage. United States Patent Application US2006/0228395 A1. [Google Scholar]

- Michiels J., De Vos M., Missotten J., Ovyn A., De Smet S., and Van Ginneken C.. 2013. Maturation of digestive function is retarded and plasma antioxidant capacity lowered in fully weaned low birth weight piglets. Br. J. Nutr. 109:65–75. doi: 10.1017/S0007114512000670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogru E., Gianello R., Libinaki R., A. Smallridge R. Bak S. Geytenbeek D. Kannar, and West S.. 2003. Vitamin E phosphate: an endogenous form of vitamin E. Medimond Med. Pub, Englewood, NJ: p. 127–132. [Google Scholar]

- Prévéraud D. P., Desmarchelier C., Rouffineau F., Devillard E., and Borel P.. 2015. A meta-analysis to assess the effect of the composition of dietary fat on α-tocopherol blood and tissue concentration in pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 93:1177–1186. doi: 10.2527/jas.2014-8422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speek A. J. 1989. Vitamin analysis in body fluids and foodstuffs with high-performance liquid chromatography. Accuracy and precision under routine conditions. PhD Diss. TNO-CIVO Toxicology and Nutrition Institute, Zeist, NL. [Google Scholar]

- van Kempen T. A., Reijersen M. H., de Bruijn C., De Smet S., Michiels J., Traber M. G., and Lauridsen C.. 2016. Vitamin E plasma kinetics in swine show low bioavailability and short half-life of α-tocopheryl acetate. J. Anim. Sci. 94:4188–4195. doi: 10.2527/jas.2016-0640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West S. M. 2000. Improved process for phosphorylation and compounds produced by this process. International patent application WO 2000/069865. [Google Scholar]

- Zingg J. M., Libinaki R., Lai C. Q., Meydani M., Gianello R., Ogru E., and Azzi A.. 2010. Modulation of gene expression by α-tocopherol and α-tocopheryl phosphate in THP-1 monocytes. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 49:1989–2000. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.09.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]