To the Editors:

BACKGROUND

HIV testing is important among female sex workers (FSWs) because they are at increased risk of HIV acquisition compared with members of the general population.1,2 The World Health Organization recommends that FSWs retest for HIV frequently to detect early HIV infection.3 Frequent HIV testing is also important for engagement in HIV prevention interventions, including treatment as prevention4,5 and pre-exposure prophylaxis.6,7

HIV self-testing is a promising new HIV testing strategy in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) that has been shown to increase HIV testing in diverse populations.8–14 The benefits of HIV testing (eg, initiation of HIV care, prevention behaviors), however, rely on correct interpretation of self-test results. HIV self-testing randomized controlled trials among FSWs in Uganda13 and Zambia14 found that HIV self-testing achieved near-universal HIV testing coverage and substituted for facility-based testing. In traditional HIV testing and counseling, HIV test results are interpreted by a trained health care professional. With HIV self-testing, the tester must correctly interpret the self-test results without professional assistance and often only the aid of the manufacturer's self-test instructions.

A number of oral HIV self-testing performance studies conducted in SSA found high participant-interpreted HIV self-test sensitivity and specificity (≥94% sensitivity and >98% specificity).15–24 In most of these studies, participants received pretest training and interpreted their own self-test result.15–22,24 None of these HIV self-testing performance studies were conducted among FSWs,15–24 an important key population for HIV prevention interventions.

We explore how well FSWs in Kampala, Uganda, who received pretest training and had 2 previous opportunities to HIV self-test, can interpret images of HIV self-test results.13

METHODS

From October to November 2016, participants were enrolled in a three-armed HIV self-testing cluster randomized controlled trial in Kampala, Uganda.13 Eligible participants were: 18 years or older, reported exchanging sex for money or goods (past month), HIV status naive or HIV-negative and did not report recent HIV testing (past 3 months), and Kampala-based.13 For this study, we only included participants randomized to the HIV self-testing intervention arms: direct provision of an HIV self-test from a peer educator or provision of coupon exchangeable for an HIV self-test at a health care facility from a peer educator, shortly after enrollment and 3 months later.13 The trial used OraQuick Rapid HIV-1/2 Antibody Tests (OraSure Technologies, Bethlehem, PA), which came with a written and pictorial instruction guide (available in both English and Luganda). The trial received ethical approval from Mildmay Uganda and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.13 All participants provided written informed consent.

We used peer educators to conduct pretest HIV self-test training in a group setting (1 peer educator and 8 participants). The training occurred shortly after enrollment during a peer educator visit that lasted approximately 45 minutes and included information on how to use an HIV self-test and interpret the results. The peer educators had a standardized guide that they were instructed to follow and were observed by research assistants to ensure the quality and consistency of information transmitted.

Participants completed a quantitative assessment at 4 months after enrollment. Here, they were asked to interpret standardized images of HIV self-test results: strong HIV-negative, strong HIV-positive, inconclusive, and weak HIV-positive. Images were presented to scale, in color, on laminated cards and were identical to those included in the manufacturer's instruction guide, which participants received to aid their interpretations. Participants were first shown an image of a strong HIV-positive or strong HIV-negative result. The image presented first reflected the result of their last HIV test, self-reported at 1 month after enrollment. Inconclusive and weak HIV-positive results were next presented in a random order. At 4 months, participants were given the option to complete a rapid HIV test (Alere Determine HIV-1/2, Waltham, MA). We collected electronic data using CommCare (Dimagi, Inc., Cambridge, MA).

We calculated the percentage of participants who incorrectly interpreted each of the self-test results and measured FSW-interpreted HIV self-test sensitivity and specificity. We used participant interpretations of the strong HIV-positive and strong HIV-negative self-test result images to respectively calculate self-test sensitivity and specificity; the interpretation of these images specified in the manufacturer's instruction guide were used as a reference for these measurements. We measured FSW-interpreted HIV self-test negative predictive values and positive predictive values using our sensitivity and specificity measurements and the HIV prevalence of our study population measured at 4 months with rapid HIV testing. Binomial 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated for all measures. We used Stata 13.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) for all analyses.

RESULTS

At enrollment, the majority of participants were younger than 30 years (58%, 314/544), self-reported the ability to read and write (86%, 466/544), completed up to 9 years of education (53%, 286/544), and had previously tested for HIV (95%, 517/544). At 4 months, almost all participants reported using an HIV self-test at least once (95%, 517/544), and participation in rapid HIV testing was 83% (452/544).

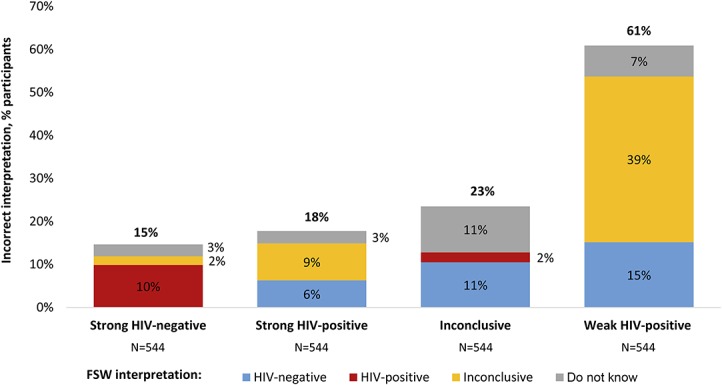

Figure 1 shows the percentage of participants who incorrectly interpreted the images of HIV self-test results and how each result was misinterpreted. Images of strong HIV-negative, strong HIV-positive, inconclusive, and weak HIV-positive self-test results were incorrectly interpreted by 15% (80/544), 18% (97/544), 23% (126/543), and 61% (328/541) of participants, respectively. The majority of participants (74%, 401/544) incorrectly interpreted at least 1 of the 4 images of HIV self-test results. FSW-interpreted HIV self-test sensitivity was 82% (95% CI: 79% to 85%) and specificity was 85% (95% CI: 82% to 88%), which is also the percentage of participants who correctly interpreted the strong positive and strong negative HIV self-test results, respectively. HIV prevalence among our study participants was 28% at 4 months, which translates into an FSW-interpreted HIV self-test positive predictive value of 68% (95% CI: 64% to 71%) and self-test negative predictive value of 92% (95% CI: 89% to 94%).

FIGURE 1.

Percentage of FSWs who incorrectly interpreted images of HIV self-test results. The heights of the vertical bars indicate the overall percentage of misinterpreted tests; the color-coded components of the bars indicate the type of misinterpretation: HIV-negative (blue), HIV-positive (red); inconclusive (yellow); do not know (gray).

DISCUSSION

Incorrect interpretation of HIV self-test results is common among Kampala-based FSWs, even after pretest training and 2 previous opportunities to HIV self-test. The FSW-interpreted HIV self-test sensitivity and specificity measurements in this study are far below those measured in most of the previous SSA HIV self-testing performance studies.15–22,24

Our HIV self-test performance measurements may differ from those in previous studies as a result of differences in pretest training. In previous HIV self-test performance studies, the pretest training provided was often individualized, extensive, and likely unrealistic or too expensive for a scalable HIV self-testing intervention.15–22 The peer-led pretest training in this study represents a realistic model for FSWs because peer educators are already a common approach for providing public sector health services to FSWs in SSA.25–28 Early at-home pregnancy tests went through a number of redesigns to make the test results more interpretable to users (eg, a plus sign for a positive result; digital results).29,30 To reduce misinterpretation of self-test results among FSWs, more research studies should be conducted on the design of HIV self-tests, the appropriate level of pre-test training, and the usefulness of on-demand support.

Methodological differences between our study and previous HIV self-testing performance studies may additionally explain our lower HIV self-test performance measurements. In our study, participants interpreted images of HIV self-test results rather than self-tests used to test themselves. In previous studies, measurements of self-test performance may have been biased because participants' previous knowledge of their HIV status may have influenced their interpretation of self-test results.15–24 Understanding how well individuals can interpret HIV self-test results without the influence of previous HIV status knowledge is important because HIV self-testing has the potential to move HIV testing outside the health care system.13 In this unregulated environment, individuals may use HIV self-tests for first-time HIV testing or to test the HIV status of other individuals, such as a child or sexual partner.

Unique characteristics of FSWs may also explain the lower HIV self-test performance measurements in this study. Compared with other populations, FSWs may have challenges interpreting HIV self-test results for reasons including lower levels of health literacy,31 higher prevalence of substance use,32–34 and differences in educational attainment.35–37

Concerns related to incorrect interpretation of HIV self-test results vary, based on which results are misinterpreted and how they are misinterpreted. Participant misinterpretation of inconclusive and weak HIV-positive self-test results was common, but in real-world settings, these results are rare.16,17,20,22 Participant misinterpretation of strong HIV-negative and strong HIV-positive self-test results was less common, but more concerning: false perceptions of HIV-positive status may cause emotional distress,38 result in stigma and discrimination,39 and alter prevention behaviors,40–43 whereas false perceptions of HIV-negative status may delay linkage to care, increasing the risk of poor health outcomes44 and secondary transmission of HIV.

This study has several limitations. First, participants did not interpret self-test results in a random order and thus, exposure to previous results may have influenced interpretations of later results.45 Second, we did not collect self-tests used by participants and thus were unable to measure the prevalence of weak HIV-positive and inconclusive self-test results. Third, participants may have paid less careful attention when interpreting an image of a self-test result rather than their own self-test result.

HIV self-testing has the potential to dramatically increase HIV testing and aid in the achievement of 90% HIV status knowledge among all individuals living with HIV by 2020.46 The effect of HIV self-testing may be diminished, however, if self-testers do not correctly interpret self-test results. To avoid misinterpretation of HIV self-test results that can result in false perceptions of HIV status, policy makers should considering implementation of realistic pretest training and on-demand HIV self-test support, whereas HIV self-test manufacturers consider redesign of HIV self-tests.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank all the study participants who took time participating in this study as well as the research assistants who took time collecting this data. K.F.O., D.K.M., J.E.H., M.M., J.A.S., T.B., and C.E.O. conceptualized the study. D.K.M., T.N., A.N., and K.F.O. oversaw data collection. K.F.O. conducted the analysis and wrote the first draft. All authors edited the draft. J.E.H., M.M., J.A.S., T.B., and C.E.O. supervised the analysis.

No funding bodies had any involvement in study design, analysis and interpretation of data, and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

The International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3ie) funded this research. K.F.O. was supported in part by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (T32AI007535, PI: Seage). J.E.H. was supported in part by the National Institute of Health (K24MH114732, PI: Haberer). T.B. was supported by the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation through the endowed Alexander von Humboldt Professorship funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research, as well as by the Wellcome Trust, the European Commission, the Clinton Health Access Initiative, and by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01-HD084233, PIs: Bärnighausen and Tanser), the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (R01-AI124389, PIs: Bärnighausen and Tanser), and the Fogarty International Center (D43-TW009775, PI: Bärnighausen). C.E.O. was supported in part by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (T32DA013911, PI: Flanigan and R25MH083620, PI: Nunn). The remaining authors have no funding or conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baral S, Beyrer C, Muessig K, et al. Burden of HIV among female sex workers in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:538–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.CDC. The Crane Survey: Female Sex Workers (FSW) in Kampala. Kampala, Uganda: CDC; 2009. Available at: https://docs.google.com/viewer?a=v&pid=sites&srcid=ZGVmYXVsdGRvbWFpbnxjcmFuZXN1cnZleXxneDo3NzE4MjNjM2YwYzRkY2E4. Accessed March 28, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO. Consolidated Guidelines on HIV Testing Services; 5Cs: Consent, Confidentiality, Counseling, Correct Results and Connection. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2015. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/179870/1/9789241508926_eng.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donnell D, Baeten JM, Kiarie J, et al. Heterosexual HIV-1 transmission after initiation of antiretroviral therapy: a prospective cohort analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:2092–2098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:493–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO. Guideline on When to Start Antiretroviral Therapy and on Pre-exposure Prophylaxis for HIV. WHO; Available at: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/earlyrelease-arv/en/. Accessed November 14, 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:399–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gichangi A, Wambua J, Gohole A, et al. Provision of Oral HIV Self-Test Kits Triples Uptake of HIV Testing Among Male Partners of Antenatal Care Clients: Results of a Randomized Trial in Kenya. 21st International AIDS Conference; July 18-22, 2016; Durban, South Afirca. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Masters SH, Agot K, Obonyo B, et al. Through secondary distribution of HIV self-tests: a randomized clinical trial. PLoS Med. 2016;13:e1002166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thirumurthy H, Masters SH, Mavedzenge SN, et al. Promoting male partner HIV testing and safer sexual decision making through secondary distribution of self-tests by HIV-negative female sex workers and women receiving antenatal and post-partum care in Kenya: a cohort study. Lancet HIV. 2016;3:e266–e274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jamil MS, Prestage G, Fairley CK, et al. Effect of availability of HIV self-testing on HIV testing frequency in gay and bisexual men at high risk of infection (FORTH): a waiting-list randomised controlled trial. Lancet HIV. 2017;4:e241–e250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson CC, Kennedy C, Fonner V, et al. Examining the effects of HIV self-testing compared to standard HIV testing services: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017:20:21594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ortblad K, Kibuuka Musoke D, Ngabirano T, et al. Direct provision versus facility collection of HIV self-tests among female sex workers in Uganda: a cluster-randomized controlled health systems trial. PLoS Med. 2017;14:e1002458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chanda M, Ortblad K, Mwale M, et al. HIV self-testing among female sex workers in Zambia: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Plos Med. 2017;14:e1002442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choko AT, MacPherson P, Webb EL, et al. Uptake, accuracy, safety, and linkage into care over two years of promoting annual self-testing for HIV in Blantyre, Malawi: a community-based prospective study. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choko AT, Desmond N, Webb EL, et al. The uptake and accuracy of oral kits for HIV self-testing in high HIV prevalence setting: a cross-sectional feasibility study in Blantyre, Malawi. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1001102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Asiimwe S, Oloya J, Song X, et al. Accuracy of un-supervised versus provider-supervised self-administered HIV testing in Uganda: a randomized implementation trial. AIDS Behav. 2014;18:2477–2484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kurth AE, Cleland CM, Chhun N, et al. Accuracy and acceptability of oral fluid HIV self-testing in a general adult population in Kenya. AIDS Behav. 2016;20:870–879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pai NP, Behlim T, Abrahams L, et al. Will an unsupervised self-testing strategy for HIV work in health care workers of South Africa? A cross sectional pilot feasibility study. PLoS One. 2013;8:e79772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dong M, Regina R, Hlongwane S, et al. Can Laypersons in Highprevalence South Africa Perform an HIV Sefl-test Accurately? 20th International AIDS Conference; 2014; Melbourne, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Napierala Mavedzenge S, Sibanda E, Mavengere Y, et al. Supervised HIV self-testing to inform implementation and scale up of self-testing in Zimbabwe. J Int AIDS Soc. Available at: https://www.rti.org/publication/supervised-hiv-self-testing-inform-implementation-and-scale-self-testing-zimbabwe. Accessed May 11, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martínez Pérez G, Steele SJ, Govender I, et al. Supervised oral HIV self-testing is accurate in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Trop Med Int Health. 2016;21:759–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nangendo J, Obuku EA, Kawooya I, et al. Diagnostic accuracy and acceptability of rapid HIV oral testing among adults attending an urban public health facility in Kampala, Uganda. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0182050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Figueroa C, Johnson C, Ford N, et al. Reliability of HIV rapid diagnostic tests for self-testing performed by self-testers compared to healthcare workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet HIV. 2017;5:e277–e290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.George A, Blankenship KM. Peer outreach work as economic activity: implications for HIV prevention interventions among female sex workers. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0119729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luchters S, Chersich MF, Rinyiru A, et al. Impact of five years of peer-mediated interventions on sexual behavior and sexually transmitted infections among female sex workers in Mombasa, Kenya. BMC Public Health. 2018;8:143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ngugi EN, Wilson D, Sebstad J, et al. Focused peer-mediated educational programs among female sex workers to reduce sexually transmitted disease and human immunodeficiency virus transmission in Kenya and Zimbabwe. J Infect Dis. 1996;174(suppl 2):S240–S247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shahmanesh M, Patel V, Mabey D, et al. Effectiveness of interventions for the prevention of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections in female sex workers in resource poor setting: a systematic review. Trop Med Int Health. 2008;13:659–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tomlinson C, Marshall J, Ellis JE. Comparison of accuracy and certainty of results of six home pregnancy tests available over-the-counter. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24:1645–1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pike J, Godbert S, Johnson S. Comparison of volunteers' experience of using, and accuracy of reading, different types of home pregnancy test formats. Expert Opin Med Diagn. 2013;7:435–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parker RG, Perez-Brumer A, Garcia J, et al. Prevention literacy: community-based advocacy for access and ownership of the HIV prevention toolkit. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016:19:21092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chersich MF, Bosire W, King'ola N, et al. Effects of hazardous and harmful alcohol use on HIV incidence and sexual behaviour: a cohort study of Kenyan female sex workers. Glob Health. 2014;10:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.White D, Wilson KS, Masese LN, et al. Alcohol use and associations with biological markers and self-reported indicators of unprotected sex in human immunodeficiency virus-positive female sex workers in Mombasa, Kenya. Sex Transm Dis. 2016;43:642–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lancaster KE, Lungu T, Mmodzi P, et al. The association between substance use and sub-optimal HIV treatment engagement among HIV-infected female sex workers in Lilongwe, Malawi. AIDS Care. 2017;29:197–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scorgie F, Chersich MF, Ntaganira I, et al. Socio-demographic characteristics and behavioral risk factors of female sex workers in sub-saharan Africa: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2012;16:920–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ngugi EN, Roth E, Mastin T, et al. Female sex workers in Africa: epidemiology overview, data gaps, ways forward. SAHARA J. 2012;9:148–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shannon K, Strathdee SA, Goldenberg SM, et al. Global epidemiology of HIV among female sex workers: influence of structural determinants. Lancet Lond Engl. 2015;385:55–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.L'akoa RM, Noubiap JJN, Fang Y, et al. Prevalence and correlates of depressive symptoms in HIV-positive patients: a cross-sectional study among newly diagnosed patients in Yaoundé, Cameroon. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Naigino R, Makumbi F, Mukose A, et al. HIV status disclosure and associated outcomes among pregnant women enrolled in antiretroviral therapy in Uganda: a mixed methods study. Reprod Health. 2017;14:107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kabiru CW, Luke N, Izugbara CO, et al. The correlates of HIV testing and impacts on sexual behavior: evidence from a life history study of young people in Kisumu, Kenya. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bunnell R, Ekwaru JP, Solberg P, et al. Changes in sexual behavior and risk of HIV transmission after antiretroviral therapy and prevention interventions in rural Uganda. AIDS Lond Engl. 2006;20:85–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Delavande A, Wagner Z, Sood N. The impact of repeat HIV testing on risky sexual behavior: evidence from a randomized controlled trial in Malawi. J AIDS Clin Res. 2016;7:549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weinhardt LS, Carey MP, Johnson BT, et al. Effects of HIV counseling and testing on sexual risk behavior: a meta-analytic review of published research, 1985-1997. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1397–1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bor J, Herbst AJ, Newell ML, et al. Increases in adult life expectancy in rural South Africa: valuing the scale-up of HIV treatment. Science. 2013;339:961–965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Strack F. “Order Effects” in survey research: activation and information functions of preceding questions. In: Context Effects in Social and Psychological Research. New York, NY: Springer; 1992:23–34. [Google Scholar]

- 46.UNAIDS. 90-90-90; an Ambitious Treatment Target to Help End the AIDS Epidemic. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS; 2014. Available at: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/90-90-90_en_0.pdf. [Google Scholar]