Abstract

There is need for a more efficient cell-based assay amenable to high-throughput drug screening against Giardia lamblia. Here, we report the development of a screening method utilizing G. lamblia engineered to express red-shifted firefly luciferase. Parasite growth and replication were quantified using D-luciferin as a substrate in a bioluminescent read-out plateform. This assay was validated for reproducibility and reliability against the Medicines for Malaria Venture (MMV) Pathogen Box compounds. For G. lamblia, forty-three compounds showed ≥ 75% inhibition of parasite growth in the initial screen (16 μM), with fifteen showing ≥ 95% inhibition. The Pathogen Box was also screened against Nanoluciferase expressing (Nluc) C. parvum, yielding 85 compounds with ≥ 75% parasite growth inhibition at 10 μM, with six showing ≥ 95% inhibition. A representative set of seven compounds with activity against both parasites were further analyzed to determine the effective concentration that causes 50% growth inhibition (EC50) and cytotoxicity against mammalian HepG2 cells. Four of the seven compounds were previously known to be effective in treating either Giardia or Cryptosporidium. The remaining three shared no obvious chemical similarity with any previously characterized anti-parasite diarrheal drugs and offer new medicinal chemistry opportunities for therapeutic development. These results suggest that the bioluminescent assays are suitable for large-scale screening of chemical libraries against both C. parvum and G. lamblia.

Author summary

Development of effective single agent therapy that could be used to treat either cryptosporidiosis or giardiasis could significantly benefit those in developing regions of the world where diagnosis may be delayed or uncertain. However, asymptomatic presentations of these diseases and overlapping symptomatology with other parasitic diarrheal diseases are significant public health challenges for which there are limited available remedies. An effective drug developed based on phenotypic properties against G. lamblia and C. parvum would likely have some impact on other diarrheal parasites and be useful as a prophylactic indication against asymptomatic diseases. An important step towards this goal is the use of fast and inexpensive methods to identify new potential drug candidates. Among the goals of this study is the design of an efficient bioluminescent assay that can be used to measure growth inhibition of G. lamblia trophozoites in an efficient, high-throughput screen of large compound libraries. Stable expression of the luciferase gene introduced into Giardia was observed over a 24-hour incubation period. The assay was validated for reproducibility and reliability against known G. lamblia drugs with the obtained EC50 values within a statistically acceptable range, compared to literature values. A test of the high-throughput drug screening capability of the assay was verified in a parallel screen of G. lamblia and C. parvum with the aim of finding potential dual pathogen-inhibiting molecules. Seven compounds inhibited both parasites at low micromolar levels as confirmed by follow up assays. This series of inhibitors could be further developed as therapeutics and potentially become an important new tool for giardiasis and cryptosporidiosis treatments.

Introduction

Cryptosporidium and Giardia are widely acknowledged as significant waterborne pathogens, as both are major contributors to the global health burden of diarrheal diseases in children under the age of five [1, 2]. Since Giardia and Cryptosporidium infections are among the most common cause of clinical and asymptomatic parasitic diseases in children in resource-limited environments, a new “dual use” therapeutic would be a very valuable treatment option. Giardia replicates through binary fission and colonizes the small intestine of vertebrate hosts by attachment through a ventral disk [3, 4]. This can affect the host’s ability to effectively absorb necessary nutrients [5]. Young children can suffer physical stunting and wasting, cognitive impairment, and fine motor movement problems [5, 6]. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved treatments for giardiasis include metronidazole, chemically related nitroimidazole drugs, and albendazole. However, a substantial number of clinical presentations are resistant to these treatments [7, 8]. A combined treatment regimen of metronidazole and albendazole or quinacrine can be highly effective for patients with metronidazole-resistant giardiasis [9, 10] but toxicity often limits therapy. Cryptosporidium infections are chronic and, in some cases, fatal in immune compromised patients [11–14]. Infection is caused by ingestion of environmentally resistant infective stages, called cysts (G. lamblia) or oocysts (C. parvum), upon passage in the feces [15]. Ingestion of as few as 10 cysts or oocysts can lead to clinical episodes [16–18]. Nitazoxanide is the only FDA-approved therapy for cryptosporidiosis. However, nitazoxanide has shown little efficacy in immunocompromised patients [19] and is not approved for use in children under the age of one [20]. Consequently, there is an increasing need to develop alternative drugs for both cryptosporidiosis and giardiasis [21].

Methods to accelerate drug discovery by high-throughput screening of large chemical libraries will require development of assay platforms that provide reliability, sensitivity, have easily observable readouts, and are both cost and time efficient. A bioluminescent assay that fits these criteria for high-throughput drug screening of inhibitors against C. parvum was recently described [22, 23]. Screening of molecules against G. lamblia parasites traditionally involved microscopic counting of parasites [24], or utilizing a MOXI cell coulter counter [25], both of which require manual counting of each well in an assay plate. Semi high-throughput assays using resazurin to measure cell viability [26] and another based on automated image analysis by cell stained-DAPI signal read-out have also been explored [27]. Most recently, a digital phase-contrast microscopy morphology-based assay method with enumeration by software was developed, which does not require cell staining [28]. The morphology-based assay is comparable to the previously reported DAPI stain method, but it relies solely on expensive software to identify and count parasites based on size and morphology [27, 28]. Stable expression of Escherichia coli β-glucuronidase A (GusA) as a reporter gene for G. lamblia growth measurement was also described as suitable for high-throughput drug screening [29]. We now describe the development of an efficient bioluminescent assay for measuring growth inhibition of trophozoites using an engineered G. lamblia strain expressing a red-shifted firefly luciferase PpyRE9h gene [30].

The Pathogen Box (www.pathogenbox.org; Medicines for Malaria Venture (MMV), Geneva, Switzerland) is a set of 400 molecules directed to a variety of “neglected disease” pathogens, including Plasmodium, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, helminths, kinetoplastids, Cryptosporidium, Toxoplasma, and dengue virus. Among the 400 molecules are 26 reference compounds [31] that are known bioactives against particular pathogens (https://www.pathogenbox.org/about-pathogen-box/composition). The Pathogen Box was screened for activity against G. lamblia and C. parvum cells, in an attempt to find potential dual pathogen-inhibiting molecules.

Materials and methods

Chemical inhibitors

The Pathogen Box (MMV) molecules were obtained as 10 mM DMSO stocks and stored at -20 °C. Metronidazole (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), a commercially available drug, was included in the study as a preliminary control of the assay, while quinacrine was used in cytotoxicity screening.

Parasite cultures

Giardia lamblia (WBC6, ATCC 50803) trophozoites were grown in TYI-S-33 medium supplemented with 10% bovine serum and 0.05 mg/mL bovine bile [32]. Transgenic C. parvum strain UGA1 expressing Nanoluciferase (Nluc) [22] used in this study was grown in HCT-8 cells. Cultures were incubated at 37°C.

G. lamblia expression construct, electroporation and selection of luciferase expressing parasite strains

Oligonucleotide pairs used to generate the Giardia transfection construct are the RE9 primers (5' ACCATGGAATCTAGAATGGAGGACGCCAAGAACAT 3' and 5' TGGATCCTCTTAATTAATCAGATCTTGCCGCCCTTCTTGGCC 3'); pBetaTub-Gib-forward (5' TCTGCAAGTTAATTTTTGGCCCCTAGGTCGGATCAAGACTTCAAATTAGAAA 3') and BetaTubUTR-Gib-reverse (5' TTATTTGACCATCGTACTTGCAACTAGTGAGCTCGGTACCAGCTGATCGGCGC 3'). The expression plasmid (pBetaTubulinPro::PpyRE9h::BetaTubulin3'UTR/pPAC-integ) was constructed by cloning the PpyRE9h luciferase gene downstream of a β-Tubulin promoter. First, the entire open reading frame of the RE9hum (thermostable red-shifted firefly luciferase PpyRE9h) was digested from the parent plasmid vector pTRIX2-RE9h using XbaI and BamHI. The RE9hum fragment, representing the 2.8 kb region, was amplified and subcloned into mNeonGreen-C18-β-tubulin [33] after excising the tubulin gene and mNeonGreen with NcoI and BamHI and digesting the amplicon with the same enzymes forming pβTub::PpyRE9h::βTub3’UTR. The pβTub::PpyRE9h::βTub3’UTR fragment was amplified using Phusion High-fidelity DNA polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL) and cloned into pPacV-integ digested with EcoRI and PmlI, using Gibson cloning. The vector pβTub::PpyRE9h::βTub3’UTR/pPacV-integ was used to integrate into chromosome 5 by homologous recombination [34]. For integration, 30 μg of pβTub::PpyRE9h::βTub3’UTR/pPacV-integ was linearized with SwaI overnight, precipitated with ethanol and incubated with 300 μL of chilled G. lamblia cells (~13x106/mL) for 30 minutes before electroporation (Bio-Rad GenePulser X at 375 V, 1000 uF, 750 ohms). After electroporation, cells were incubated on ice for 10 minutes before being transferred to fresh media at 37 °C. Transfectants were selected with puromycin after overnight recovery, as previously described [35].

Assay parameters determination for G. lamblia

To determine optimal D-luciferin (Gold BioTechnology Inc., St. Louis, MO) concentration, substrate was serially diluted 1:2 in PBS from 100 mg/mL to 0.052 mg/mL. Parasite numbers were kept constant at 50,000 cells/mL in a volume of 250 μL per well. Plates were incubated for 30 minutes at 37 °C on a plate shaker. Wild-type G. lamblia (non-luciferase expressing) was used as a control.

To determine the optimal parasite concentration, an initial cell concentration of ~1x106 cells/mL was serially diluted 1:2, to a minimum concentration of ~500 cells/mL. Luminescence was measured at 20, 30 and 40 minutes in white polystyrene, flat bottom 96-well plates (Corning Incorporated, Kennebunk, ME) on an EnVision plate reader (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA).

G. lamblia luciferase strain assay condition validation with metronidazole

Preliminary effective concentration that causes 50% growth inhibition (EC50) assays were performed on the luciferase expressing and wild-type (control) G. lamblia cells to establish a correlation between manually counted cells and the bioluminescent signal read out. Trophozoites were harvested by chilling cultures on ice for 30 minutes and plated by adding 150 μL per well at a concentration of 250,000 cells/mL. Metronidazole (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was used as a control and was serially diluted 1:2 from 40 μM to 0.04 μM and 150 μL was added to the 150 μL of the G. lamblia trophozoites. Plates were covered in plastic low-evaporation lids, sealed in individual anaerobic BD GasPak Bio-Bags (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) and incubated at 37 °C for 24 hours. Plates were then iced for 30 minutes and 250 μL of resuspended cells were transferred to a solid white 96-well plate and 50 μL of 10 mg/mL D-luciferin was added to a final reaction concentration of 1.67 mg/mL. Plates were incubated on a plate shaker at 37 °C for 30 minutes and read on an EnVision Plate Reader. A duplicate plate was concurrently set up and assayed using a MOXI Z Mini Automated Cell Counter Kit (Orflo, Ketchum, ID). Results obtained from the bioluminescence assay and the MOXI counter data were compared to evaluate their correlation to each another. Albendazole (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), an alternative giardiasis therapeutic, was assayed in concentrations from 4 μM to 0.004 μM with only the luciferase expressing G. lamblia cells.

In vitro activity of compounds against C. parvum

Growth inhibition and EC50 determination assays were performed using UGA1 Nluc expressing C. parvum strain in HCT-8 cells (ATCC©, Manassas, VA) as previously described [23]. HCT-8 cells were inoculated onto 96-well plates and allowed to grow for 48 hours to 90–100% confluence and then treated with single concentration (10 μM) or serially diluted compounds prior to oocyst infection. C. parvum oocysts were incubated for 10 minutes in 10% bleach at room temperature and then washed with DPBS. One thousand oocysts per well were applied to the 96 well plates with RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% horse serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin at the same time as compound addition and incubated for 48 hours. The cell monolayers were lysed for 1 hour before adding Nano-Glo® luciferase reagent (Promega, Madison, WI), and measuring relative luminescence units (RLU) in an EnVision Plate Reader (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA). Several parameters, including reproducibility and reliability, were previously evaluated to optimize this assay for low and high-throughput (HTP) screening of small molecule compounds against C. parvum [23]. EC50 values were calculated using Prism 7 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Pathogen Box molecule screening

The 400 compounds in the Pathogen Box were initially screened against the bioluminescent strain of G. lamblia in duplicate at 16 μM as described above. Further experiments were carried out to determine the EC50 values of molecules that were found to have ≥ 95% inhibition of G. lamblia or C. parvum cell growth after the initial screen. Compounds were serially diluted 1:2 starting at an initial concentration of 8 μM to a final 0.015 μM for G. lamblia. C. parvum screening against the Pathogen Box compounds was performed as previously described starting at a concentration of 10 μM [23]. Assays to determine EC50 values were also performed for a subset of compounds found to have ≥ 75% growth inhibition of both G. lamblia and C. parvum in the initial screens as potential dual inhibiting molecules.

Cytotoxicity against HepG2 cells

Mammalian cell cytotoxicity assay data performed on HepG2 (human hepatocellular carcinoma) cells and described as CC20 or CC50 values are provided in supporting documentation that accompanied the Pathogen Box for approximately three quarters of the 400 compounds. However, no details of the assay conditions or parameters were provided [31]. In this study, selected compounds were further tested for cytotoxicity against HepG2 cells as previously described [36]. Briefly, cells were exposed to two-fold serial dilutions of compounds for 48 hours and cytotoxicity was assessed using the AlamarBlue® viability assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Each dilution was assayed in quadruplicate and concentrations causing 50% growth inhibition (CC50) were calculated by non-linear regression using GraphPad Prism 7 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Statistical analysis

The data was analysed in Microsoft Excel and Prism 7 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). A nonlinear regression sigmoidal dose-response curve fit was applied to dose-response data for both half maximal effective concentration and half maximal cytotoxic concentrations.

Results

Red-shifted luciferase expressing G. lamblia strains and assay parameter optimization

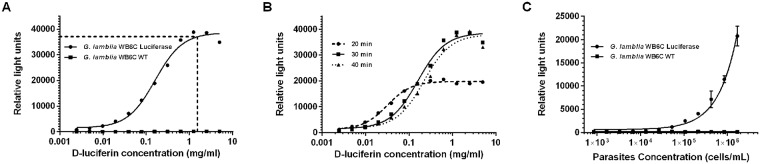

Wild-type G. lamblia cells were transfected with pβTub::PpyRE9h::βTub3’UTR/pPacV-integ (Fig 1), selected clones express red-shifted firefly luciferase PpyRE9h as validated by detectable bioluminescence signals when incubated with serial concentrations of D-luciferin in parallel to the wild-type strain (Fig 2a). Optimum luminescence was achieved after 30 minutes of incubation with D-luciferin (Fig 2b). The optimal concentration of D-luciferin was determined to be 1.67 mg/mL, as bioluminescence signals plateaued above this concentration within 30 minutes (Fig 2b) demonstrating no reasonable need for higher concentrations. The amount of red-shifted firefly luciferase-driven bioluminescence activity was proportional to the number of viable transfected G. lamblia parasites per well, as determined by a comparative analysis with direct cell count of both the wild type and transfectant strains (Fig 2c). Considering G. lamblia’s doubling time of 8 hours [33], the optimal starting concentration of cells to achieve the highest bioluminescent signal was determined to be ~125,000 cells/mL, as this would result in an ending concentration of ≥106 cells/mL after 24 hours of growth (Fig 2c).

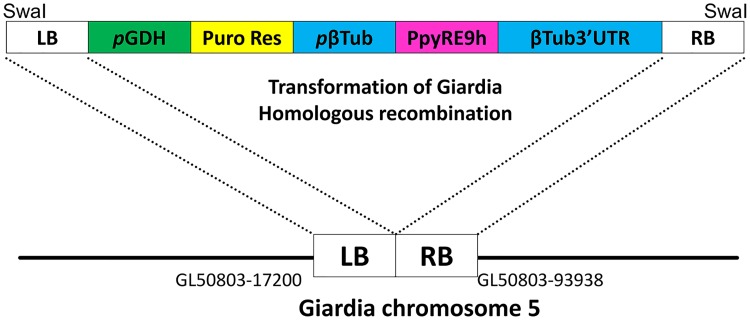

Fig 1. Schematic of targeting vector and homologous recombination.

The expression cassette containing pGDH::Puro Res and pβTub::PpyRE9h:: β3’TubUTR was used for homologous recombination to target a genomic intergenic region which is flanked with GL50803_17200 and GL50803_93938. After electroporation, puromycin was used to select for transfected cells. LB = left border, pGDH = Promoter of glutamate dehydrogenase (GL50803_21942), Puro Res = puromycin N-acetyltransferase, pβTub = β tubulin promoter, PpyRE9h = red-shifted luciferase coding sequence, β3’Tub UTR = β tubulin 3’UTR, RB = right border.

Fig 2. Assay parameters determination.

A. D-luciferin concentration in relation to RLU. Serial concentration of D-luciferin relative to the wild-type strain to determine the optimal concentration of D-luciferin to use in assays. The reaction was carried out for 30 min. The line shows the RLU data-points at 10 mg/ml of D-luciferin. (RLU: relative light units). B. Optimization of incubation time. D-luciferin concentration in relation to relative light units (RLU) was measured at different time points. C. Parasite concentration and RLU values. The plot showed bioluminescence read out from the wild type strain and the transfectant strain correlating number of cells to RLU. The values of both the luciferase strain and wild-type strain are shown with respective RLU at 30 min. (P-value of luciferase strain < 0.001: Wild-type p = 0.854). RLU versus parasite concentration helps to determine the ideal maximal end concentration without overgrowth carrying out the reaction for 30 min.

Assay condition validation with metronidazole and albendazole

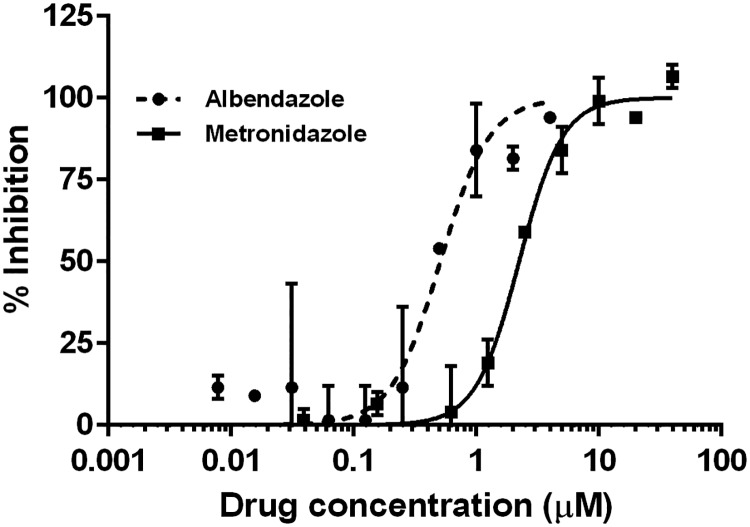

A preliminary experiment to determine the reliability of the bioluminescence-based G. lamblia assay for drug inhibitory activities was performed using metronidazole and albendazole. The metronidazole EC50 values obtained from 125,000 cells/mL by MOXI coulter counter (EC50 = 1.06 μM) and the luciferase-based assay (EC50 = 2.24 μM) are within the acceptable range for experimental errors. The luciferase-based assay EC50 value of 0.41 μM was obtained for albendazole (Fig 3). These EC50 values confirmed the reliability of the luminescence signal-based assay as compared to previous cell counting methods. Furthermore, the experimentally derived EC50 value of standard clinical giardiasis therapies using this new assay track with previously documented literature values of ~5 μM [37] or 8.65 μM [38] for metronidazole and 0.23 μM for albendazole (reference strain—WB) [38].

Fig 3. A plot of the EC50 of values of metronidazole and albendazole.

Growth of red-shifted luciferase expressing Giardia trophozoite was inhibited by metronidazole and albendazole with EC50 of 2.24 μM and 0.41 μM, respectively.

Initial screening hits and EC50 against Giardia and Cryptosporidium

The screening of the Pathogen Box against G. lamblia at 16 μM led to the identification of one hundred and four compounds with ≥ 50% inhibition, forty-three compounds with ≥ 75% inhibition of cell growth, among which twenty-two showed ≥ 90% and fifteen compounds showed ≥ 95% inhibition (S1 Table and Table 1). EC50 values determined for thirteen of the molecules with ≥ 95% inhibition ranged from 0.5 to >10 μM (Table 1). Two (MMV153413 and MMV688283) of the fifteen hits with ≥ 95% inhibition at 16 μM initial screening were deemed to be false positives since they were not potent in the follow up serial titration of the drugs. Screening against C. parvum at 10 μM yielded one hundred and eighty-five compounds with >50% inhibition, eighty-six compounds with ≥75% inhibition, twenty-five compounds with ≥ 90% inhibition and six compounds with ≥ 95% inhibition (S1 Table). The six compounds with cell growth inhibition ≥95% were tested to determine their EC50 values against C. parvum. The compounds MMV676477, MMV688853, MMV002817, MMV085499, MMV019189 and MMV102872 have C. parvum EC50 values of 0.22, >10, 0.48, 1.93, 2.52, and 0.14 μM respectively.

Table 1. Pathogen Box compounds tested for dose response against G. lamblia.

| Common name | MMV Compound ID | G. lamblia EC50 | HepG2 CC50 (μM) (this study) | HepG2 CC50 (μM) (literature values) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (μM) | (μM) | |||

| Nifurtimox | MMV001499 | 0.64 ± 0.12 | >40 | >80*^ |

| N/A | MMV022478 | 2.41 ± 0.12 | >40 | >10* |

| N/A | MMV028694 | 3.88 ± 1.27 | 15.87 | 8.10* |

| N/A | MMV495543 | 2.77 ± 0.21 | >40 | 47.60* |

| N/A | MMV676395 | 1.57 ± 0.20 | >40 | >100* |

| Clofazimine | MMV687800 | 1.79 ± 0.23 | 26.43 | >20+ |

| N/A | MMV687807 | 0.51 ± 0.06 | <5 | 0.70* |

| N/A | MMV687812 | 1.25 ± 0.12 | 5.33 | 3.90* |

| Delamanid | MMV688262 | 0.55 ± 0.04 | >40 | 72.50* |

| N/A | MMV688755 | 1.57 ± 0.38 | >40 | >50* |

| N/A | MMV688844 | 2.30 ± 0.43 | >40 | >50* |

| Auranofin | MMV688978 | 3.74± 0.46 | 0.50 | 4.50# |

| Nitazoxanide | MMV688991 | 0.80 ± 0.10 | 10.73 | 6.35*^ |

* Pathogen_Box_Activity_Biological_Data_ Structure & Smiles (https://www.pathogenbox.org/about-pathogen-box/composition)

N/A–not applicable;

^ HepG2 CC20 (μM)

+ reference [41];

# reference [56]

Of the 400 Pathogen Box molecules, there were sixteen molecules with activity against both parasites at ≥75% inhibition. EC50 analysis was performed for a representative subset of seven of these dual hit molecules. All seven molecules had EC50 values of ≤ 5 μM on both parasites within the selected cytotoxicity criteria (HepG2 ≥5-fold of the observed EC50 value). Previously described anti-giardia and/or anti-cryptosporidiosis drugs auranofin [39, 40], nitazoxanide [41], nifurtimox [38], and clofazimine [41] were found as dual hits in this screen. Furthermore, EC50s obtained using the new assay platform are very similar to those obtained for the wild-type G. lamblia strain and available literature-based comparisons (Table 2, S2 Table). Auranofin is highlighted as a potent hit against G. lamblia and C. parvum (Table 2), in agreement with literature results (G. lamblia EC50 = 4–6 μM in [40]; C. parvum EC50 = 2 μM in [39]). Clofazimine (G. lamblia EC50 = 1.79 μM and C. parvum EC50 = 3.3 μM) is a promising dual treatment option to further explore. The remaining tested hits (Table 2) share no obvious chemistry with these previously characterized anti-parasitic drugs. One of the best examples of this novel dual-inhibiting compound is MMV010576 which had 3.0 and 1.9 μM EC50 against C. parvum and G. lamblia in cell proliferation assays, respectively (Table 2). The other is MMV676501 with detectable cytostatic effects on mammalian cells at high concentrations of 50.1 μM (Table 2). These have reasonable safety indices (EC50 of both parasites/CC50 against mammalian cells) for further exploration.

Table 2. Representative set of dual hits against Giardia and Cryptosporidium with ≥ 75% inhibition.

EC50: 50% effective concentration, CC50: 50% cytotoxic concentration, % inh: percentage inhibition.

| Common name | MMV Compound ID | G. lamblia EC50 (μM) | C. parvum EC50 (μM) | HepG2 CC50 (μM) (this study) | HepG2 CC50 (μM) (literature values) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iodoquinol | MMV002817 | 2.52 ± 0.45 | 0.48± 0.2 | ~40 | 2.50*^ |

| N/A | MMV010576 | 1.9 ± 0.28 | 2.99 ± 2.1 | >40 | >10* |

| N/A | MMV028694 | 3.88 ± 1.27 | 1.56 ± 0.5 | 15.87 | 8.10* |

| N/A | MMV676501 | 1.40 ± 0.2 | 4.96 ± 1.8 | >40 | 50.10* |

| Clofazimine | MMV687800 | 1.79 ± 0.2 | 3.33 ± 1.2 | 26.43 | >20+ |

| Auranofin | MMV688978 | 3.74 ± 0.46 | 3.34 ± 2.7 | 0.50 | 4.50# |

| Nitazoxanide | MMV688991 | 0.80 ± 0.10 | 3.10 ± 0.4 | 10.73 | 6.35*^ |

* Pathogen_Box_Activity_Biological_Data__ Structure & Smiles (https://www.pathogenbox.org/about-pathogen-box/composition)

N/A–not applicable;

^ HepG2 CC20 (μM)

+ reference [41];

# reference [56]

There were no specific data on the biological activity of inhibitors against G. lamblia as documented for C. parvum in the MMV Pathogen_Box_Activity_Biological_Data_Smiles (https://www.pathogenbox.org/about-pathogen-box/composition). This makes direct comparison of biological activity for G. lamblia obtained in our study against the Pathogen Box data sheet challenging. However, 11 compounds in the Pathogen Box series were designated as anti-cryptosporidiosis agents. Pathogen Box datasheet reported EC50s between 0.05 μM and >5 μM for compounds MMV675968, MMV675993, MMV675994, MMV676050, MMV676053, MMV676599, MMV688853 and MMV688854. Initial screening data in our study found C. parvum cell growth inhibition at 10 μM to be between 79 and 96% with substantially lower effects on G. lamblia trophozoites (S1 Table). Hence, they were not progressed to the next stage of EC50 determination based on our dual hit selection criteria. Compound MMV675968 was however, a dual hit in the initial screen with 88 and 90% inhibition of C. parvum and G. lamblia growth, respectively. In the follow up serial dilution assays, MMV675968 had EC50s of 2.1 μM and >10 μM for C. parvum and G. lamblia, respectively, thus ruling it out as a dual hit. MMV676191 had a 36% inhibitory activity on C. parvum cells in our initial screen at 10 μM, in agreement with the Pathogen Box datasheet reported EC50 of >10 μM. Dual hit compounds MMV676604 (C. parvum EC50 of 2.9 μM) and MMV676602 (C. parvum EC50 of 0.31 μM) were also not effective in the follow up EC50 assay against G. lamblia. The most obvious conclusion from the comparative analysis of anti-Cryptosporidiosis activity as provided by the MMV Pathogen Box datasheet with those obtained in this study is that there is great overlap in the results against C. parvum cells.

Cytotoxicity

Compounds with parasite EC50s ≤5 μM and within the selected cytotoxicity criteria (on mammalian HepG2 cells) were deemed potent hits. Sixteen compounds are dual hits with ≥75% initial growth inhibition against both parasites, three molecules were dropped from further consideration due to HepG2 cytotoxicity data from MMV and reduced efficacy in the follow up assay to determine their EC50s for G. lamblia. These include compounds MMV676602 and MMV676604. Recent interest in compound MMV687807 as a potential compound that may be further developed as an agent against Candida albicans [42] and Toxoplasma gondii [43] despite undesirable activity at 0.7 μM against HepG2 (Table 2) argues for its inclusion in our analysis against G. lamblia. However, MMV687807 was too toxic to the HCT-8 host cells in the C. parvum assay that a reliable EC50 value could not be determined. Although auranofin showed high cytotoxicity levels of 0.50 μM against HepG2 cells (Tables 1 and 2), it has already entered clinical trials as a possible anti-giardial [44]. Similarly, nitazoxanide showed activity against C. parvum and was considered a legitimate hit being already approved for clinical use. Altogether, seven molecules with EC50s ≤5 μM and within the selected cytotoxicity barrier (in HepG2 ≥5-fold of the observed EC50) were deemed potent dual hits.

Discussion

Despite the significant health impact of giardiasis and cryptosporidiosis, research into new drug treatments are only beginning to move ahead with promising strategies and new drug leads [45]. Cryptosporidiosis and giardiasis illness can be self-limiting or persistent without overt symptoms, but still exert a detrimental effect on growth [46]. When these infections become symptomatic, the overlap in symptomatology with a host of other enteric infections is plentiful. Co-infection of Cryptosporidium and Giardia, as well as co-infections with other pathogens, have been reported in studies from a number of developing countries [46–48] where rapid diagnostics may be available but not widely used. Even in resource-rich communities where specific diagnostics could be used routinely, definite identification of etiologic agent of mixed parasitic infections each with overlapping symptomatology could be challenging. The potential for devastating consequences of giardiasis and cryptosporidiosis in immunocompromised patients and malnourished children as clinical or asymptomatic presentations emphasize the need for an effective therapy that could be used as point of care treatment. This point of care treatment will be appropriate where diagnosis may be delayed or uncertain. Such treatments could be useful as a prophylactic in combating asymptomatic presentations in regions with lagging sanitary conditions. An important step towards this goal is the use of fast and inexpensive methods to identify new potential drug candidates. A recently described bioluminescence assay [22, 23] effectively solved this problem for C. parvum. The luciferase expressing strain of G. lamblia described here offers a similar tool for use in the search for new giardiasis treatments.

The assay described here may be compared to a previously reported ATP-based screening in G. lamblia [38] that employed ATP lite, a Luminescence ATP Detection System (Perkin Elmer) that requires a cell lysis step and exogenous supplementation of the reaction mixture with luciferase protein and D-luciferin in a well-controlled pH environment, to ensure no endogenous ATP degrading enzyme activity [38]. The engineered luciferase expressing G. lamblia strain described here employs the same principle. However, it has the advantage of requiring neither a lysis step nor exogenous luciferase supplementation since this G. lamblia strain constitutively expresses the luciferase needed for the read out, thereby reducing the resources needed for screening.

We have shown here that the engineered Giardia strain PpyRE9h-Tub is an effective tool for phenotypic screening of compounds with potential anti-giardial activity. The bioluminescence measurement provided by this strain offers similar efficiency when adapted to high-throughput screening as the previously described GusA G. lamblia [29]. Strain PpyRE9h-Tub has additional benefit for a broader range of assays, in particular the potential for non-invasive imaging of parasite load in Giardia-infected animals. Evidence of use of the luciferase reporter in a mouse model of giardiasis was recently reported [49]. Comparative analysis showed that the luciferase-based assay described here has a high level of reliability and reproducibility based on the assay of a known standard drug, metronidazole, a previously-known alternative, albendazole, and determination of EC50s for selected hits from the Pathogen Box library. This assay overcomes the limitation of drug screening platforms that rely on assessment of parasite numbers without regard to parasite viability [27, 28], since only viable parasite cells can produce the ATP required for the D-luciferin reaction.

One limitation of the luminescence screening platform is less efficient parasite growth in volumes lower than 300 μL per well in 96-well plates, due to G. lamblia’s surface area to volume requirement. Lower reaction volume seems to result in higher oxygen exposure during handling that prevents optimum cell replication [27]. The luciferase assay is further constrained by only detecting the bioluminescent signal, while the digitized methods, using DAPI or phenotypic recognition, both have potential for retrospective analysis of cytology [28]. However, this could be more appropriately re-evaluated further downstream during drug development. The set-up of the assay as described here includes a relatively high inoculum incubated for 24 hours. This may have the disadvantage of missing compounds with slower mode of action, which may explain why reference compounds with known efficacies against G. lamblia such as mebendazole (MMV003152) and pentamidine (MMV000062) did not show up in the screen with the luciferase readout described here. This can be remedied with a set-up using lower inoculum for a longer incubation time (48 hours). An unfortunate shortcoming of cell based high-throughput screens is the poor correlation that is sometimes observed between percent inhibition at fixed concentration (initial screen) and the EC50 obtained in a dose response assay. Hence, the initial dual hit MMV024114 as well as a number of hits were not potent in the follow up serial dilution assays to determine their EC50s for G. lamblia (MMV675968, MMV676602, MMV676604 and MMV688283) and C. parvum (MMV024406 and MMV676395). Previous studies have shown that false positive and/or negative rates could be high [50]. Furthermore, assigning cut off points for the selection of inhibitors for further evaluation may sometimes miss compounds that perform excellently in vivo. An example in this study is the calcium dependent protein kinase inhibitor, BKI-1294 (MMV688854), with 79% inhibition at the initial screening concentration of 10 μM which is not within the 95% cut off. BKI-1294 (MMV688854) was previously shown to be effective (EC50 2.7 μM) using the same strain of Nluc C. parvum in an in vivo mouse model of cryptosporidiosis [23]. Nonetheless, the bioluminescent assay is an efficient and inexpensive method for high-throughput screening that does not require counting, staining, or lysis and can be further used to study efficacy with in vivo models of infection [49, 51].

The top hits from screening against G. lamblia trophozoites (Table 1) include two drugs, nitazoxanide and nifurtimox, which share the same free-radical mediated mode of action as the current front-line anti-giardial metronidazole. Both have been previously noted for potential anti-giardial use [41, 52] and nitazoxanide has been used against C. parvum demonstrating some clinical efficacy including a significantly lower mortality rate in one trial [53]. There is a strong potential for cross resistance since these compounds share their mechanism of action with metronidazole [41, 45].

Another known drug identified in the screen, iodoquinol, is primarily used for anti-amoebiasis but is also used as an anti-giardial drug, in combination with metronidazole [54]. Iodoquinol chelates ferrous ions that are essential for metabolism in amoeba. To the best of our knowledge, it had not been used for treatment of cryptosporidiosis, but can be included as a candidate for dual use.

The FDA-approved drug auranofin has gained interest in regards to a possible repurposing strategy due to its anti-parasitic activities in S. mansoni, T. brucei, E. histolytica and G. lamblia [40]. Auranofin was previously identified as potent against C. parvum [39] in screens to re-profile FDA-approved drugs for new therapy for neglected tropical diseases. The mechanism of action of auranofin mainly consists of inhibiting reduction/oxidation enzymes, thereby damaging pathogens by oxidative stress. Auranofin activity against C. parvum and G. lamblia trophozoites as shown here (Table 2) is consistent with previous findings of its usefulness as a broad anti-diarrheal agent [39]. It has already entered clinical trials as a possible anti-giardial [44]. Auranofin and iodoquinol provide the best argument for the possibility of drug candidates with therapeutic effects on multiple diarrheal parasites that can be carefully deployed for syndromic use at the point of care.

Clofazimine also shows promise for use in treatment of both cryptosporidiosis and giardiasis. Good clinical outcomes in experimental models have increased enthusiasm for clofazimine as a potential drug repurposing candidate for the treatment of human cryptosporidiosis [41]. It is currently being evaluated in clinical trials as a potential anti-cryptosporidiosis agent. It would be of scientific interest to further study clofazimine’s efficacy and safety for treatment of both pathogens, as it is a regulatory approved drug that has been used for over 50 years for leprosy and more recently for the therapy of multi-drug resistant tuberculosis.

MMV010576 selectively kills both parasites with little to no cytotoxicity to mammalian cells. The scaffold for this compound was originally identified from a high throughput screen of a BioFocus DPI SoftFocus kinase library of selective anti-plasmodial hits. MMV010576 belongs to a novel class of orally active 3,5-diarylaminopyridine series, which combines good in vitro activity against P. falciparum with efficacy in a P. berghei mouse model following administration of single oral doses [55]. MMV010576 is a kinase inhibitor [31] found to have selective inhibition of C. parvum and G. lamblia cell proliferation relative to a mammalian cell line (Table 2). The properties of MMV010576 provide preliminary evidence that dual parasite inhibiting kinase inhibitors could be identified in a phenotypic HTS assay. It raises the potential for development and use of kinase inhibitors for syndromic treatment of either cryptosporidiosis or giardiasis. Together with three similarly uncharacterized hits retrieved from recent screening of the Malaria Box [28], these constitute a valuable starting point for the development of dual anti-giardial and anti-cryptosporidiosis drugs.

Concluding remarks

The bioluminescent assay for Giardia growth described here was optimized and found to be comparable to assays performed with automated cell counters. Reproducibility was validated by comparing known literature EC50s of metronidazole, auranofin, nitazoxanide and nifurtimox, finding all to be within a two-fold difference of our results. This suggests that the described bioluminescent assay can efficiently be used for semi high-throughput drug screening. Furthermore, the found dual-inhibiting compounds are of great public health importance since these could be suitable for co-infections or in situations where the precise diarrheal-causing pathogens cannot be determined. The luciferase-expressing G. lamblia strain could also be adapted for in vivo experimentation in infected animal models, advancing drug development and screening for G. lamblia similar to the way that Nluc expressing C. parvum has for Cryptosporidium [22, 23].

Supporting information

Mean percentage inhibition was calculated as the inhibition when compared to the mean values of wells grown with 1 μL DMSO in place of compound.

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Evotec and MMV for providing us the Pathogen Box compound library. The authors will like to thank Dr. Wesley C. Van Voorhis for helpful discussions. The PpyRE9h gene plasmid vector pTRIX2-RE9h was a kind gift from Dr. Bruce Branchini of Connecticut University (USA).

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

The study was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (USA) and National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health (USA) under the award numbers R01AI089441, R01AI111341, R01AI110708, R21AI119715, R21 AI127493, R21AI123690, R01GM086858 and R01HD080670. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Donowitz JR, Alam M, Kabir M, Ma JZ, Nazib F, Platts-Mills JA, et al. A Prospective Longitudinal Cohort to Investigate the Effects of Early Life Giardiasis on Growth and All Cause Diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(6):792–7. 10.1093/cid/ciw391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Platts-Mills JA, Babji S, Bodhidatta L, Gratz J, Haque R, Havt A, et al. Pathogen-specific burdens of community diarrhoea in developing countries: a multisite birth cohort study (MAL-ED). Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3(9):e564–75. 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00151-5 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Owen RL, Nemanic PC, Stevens DP. Ultrastructural observations on giardiasis in a murine model. I. Intestinal distribution, attachment, and relationship to the immune system of Giardia muris. Gastroenterology. 1979;76(4):757–69. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katelaris PH, Naeem A, Farthing MJ. Attachment of Giardia lamblia trophozoites to a cultured human intestinal cell line. Gut. 1995;37(4):512–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carvalho-Costa FA, Gonçalves AQ, Lassance SL, Silva Neto LMd, Salmazo CAA, Bóia MN. Giardia lamblia and other intestinal parasitic infections and their relationships with nutritional status in children in Brazilian Amazon. Revista do Instituto de Medicina Tropical de São Paulo. 2007;49(3):147–53. 10.1590/s0036-46652007000300003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Botero-Garces JH, Garcia-Montoya GM, Grisales-Patino D, Aguirre-Acevedo DC, Alvarez-Uribe MC. Giardia intestinalis and nutritional status in children participating in the complementary nutrition program, Antioquia, Colombia, May to October 2006. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2009;51(3):155–62. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nash TE, Ohl CA, Thomas E, Subramanian G, Keiser P, Moore TA. Treatment of patients with refractory giardiasis. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33(1):22–8. 10.1086/320886 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nabarro LE, Lever RA, Armstrong M, Chiodini PL. Increased incidence of nitroimidazole-refractory giardiasis at the Hospital for Tropical Diseases, London: 2008–2013. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21(8):791–6. 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.04.019 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bawa S, Kumar S, Drabu S, Kumar R. Structural modifications of quinoline-based antimalarial agents: Recent developments. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2010;2(2):64–71. 10.4103/0975-7406.67002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leitsch D. Drug Resistance in the Microaerophilic Parasite Giardia lamblia. Curr Trop Med Rep. 2015;2(3):128–35. 10.1007/s40475-015-0051-1 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thompson RC, Olson ME, Zhu G, Enomoto S, Abrahamsen MS, Hijjawi NS. Cryptosporidium and cryptosporidiosis. Adv Parasitol. 2005;59:77–158. 10.1016/S0065-308X(05)59002-X . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feasey NA, Healey P, Gordon MA. Review article: the aetiology, investigation and management of diarrhoea in the HIV-positive patient. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34(6):587–603. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04781.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Connor R M, Shaffie R, Kang G, Ward HD. Cryptosporidiosis in patients with HIV/AIDS. AIDS. 2011;25(5):549–60. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283437e88 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shirley DA, Moonah SN, Kotloff KL. Burden of disease from cryptosporidiosis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2012;25(5):555–63. 10.1097/QCO.0b013e328357e569 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kirkpatrick CE. Feline Giardiasis—a Review. J Small Anim Pract. 1986;27(2):69–80. 10.1111/j.1748-5827.1986.tb02124.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DuPont HL, Chappell CL, Sterling CR, Okhuysen PC, Rose JB, Jakubowski W. The infectivity of Cryptosporidium parvum in healthy volunteers. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(13):855–9. 10.1056/NEJM199503303321304 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okhuysen PC, Chappell CL, Crabb JH, Sterling CR, DuPont HL. Virulence of three distinct Cryptosporidium parvum isolates for healthy adults. J Infect Dis. 1999;180(4):1275–81. 10.1086/315033 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Busatti HG, Santos JF, Gomes MA. The old and new therapeutic approaches to the treatment of giardiasis: where are we? Biologics. 2009;3:273–87. . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sparks H, Nair G, Castellanos-Gonzalez A, White AC Jr. Treatment of Cryptosporidium: What We Know, Gaps, and the Way Forward. Curr Trop Med Rep. 2015;2(3):181–7. 10.1007/s40475-015-0056-9 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fox LM, Saravolatz LD. Nitazoxanide: a new thiazolide antiparasitic agent. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40(8):1173–80. 10.1086/428839 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Checkley W, White AC Jr., Jaganath D, Arrowood MJ, Chalmers RM, Chen XM, et al. A review of the global burden, novel diagnostics, therapeutics, and vaccine targets for cryptosporidium. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(1):85–94. 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70772-8 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vinayak S, Pawlowic MC, Sateriale A, Brooks CF, Studstill CJ, Bar-Peled Y, et al. Genetic modification of the diarrhoeal pathogen Cryptosporidium parvum. Nature. 2015;523(7561):477–80. 10.1038/nature14651 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hulverson MA, Vinayak S, Choi R, Schaefer DA, Castellanos-Gonzalez A, Vidadala RSR, et al. Bumped-Kinase Inhibitors for Cryptosporidiosis Therapy. J Infect Dis. 2017;215(8):1275–84. 10.1093/infdis/jix120 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fisher BS, Estrano CE, Cole JA. Modeling long-term host cell-Giardia lamblia interactions in an in vitro co-culture system. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e81104 10.1371/journal.pone.0081104 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hennessey KM, Smith TR, Xu JW, Alas GC, Ojo KK, Merritt EA, et al. Identification and Validation of Small-Gatekeeper Kinases as Drug Targets in Giardia lamblia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10(11):e0005107 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005107 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benere E, da Luz RA, Vermeersch M, Cos P, Maes L. A new quantitative in vitro microculture method for Giardia duodenalis trophozoites. J Microbiol Methods. 2007;71(2):101–6. 10.1016/j.mimet.2007.07.014 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gut J, Ang KK, Legac J, Arkin MR, Rosenthal PJ, McKerrow JH. An image-based assay for high throughput screening of Giardia lamblia. J Microbiol Methods. 2011;84(3):398–405. 10.1016/j.mimet.2010.12.026 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hart CJ, Munro T, Andrews KT, Ryan JH, Riches AG, Skinner-Adams TS. A novel in vitro image-based assay identifies new drug leads for giardiasis. Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist. 2017;7(1):83–9. 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2017.01.005 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muller J, Nillius D, Hehl A, Hemphill A, Muller N. Stable expression of Escherichia coli beta-glucuronidase A (GusA) in Giardia lamblia: application to high-throughput drug susceptibility testing. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;64(6):1187–91. 10.1093/jac/dkp363 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Branchini BR, Ablamsky DM, Davis AL, Southworth TL, Butler B, Fan F, et al. Red-emitting luciferases for bioluminescence reporter and imaging applications. Anal Biochem. 2010;396(2):290–7. 10.1016/j.ab.2009.09.009 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duffy S, Sykes ML, Jones AJ, Shelper TB, Simpson M, Lang R, et al. Screening the Medicines for Malaria Venture Pathogen Box across Multiple Pathogens Reclassifies Starting Points for Open-Source Drug Discovery. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;61(9). 10.1128/AAC.00379-17 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Keister DB. Axenic culture of Giardia lamblia in TYI-S-33 medium supplemented with bile. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1983;77(4):487–8. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hardin WR, Li R, Xu J, Shelton AM, Alas GCM, Minin VN, et al. Myosin-independent cytokinesis in Giardia utilizes flagella to coordinate force generation and direct membrane trafficking. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017. 10.1073/pnas.1705096114 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stefanic S, Morf L, Kulangara C, Regos A, Sonda S, Schraner E, et al. Neogenesis and maturation of transient Golgi-like cisternae in a simple eukaryote. J Cell Sci. 2009;122(Pt 16):2846–56. 10.1242/jcs.049411 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krtkova J, Thomas EB, Alas GC, Schraner EM, Behjatnia HR, Hehl AB, et al. Rac Regulates Giardia lamblia Encystation by Coordinating Cyst Wall Protein Trafficking and Secretion. MBio. 2016;7(4). 10.1128/mBio.01003-16 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vidadala RS, Ojo KK, Johnson SM, Zhang Z, Leonard SE, Mitra A, et al. Development of potent and selective Plasmodium falciparum calcium-dependent protein kinase 4 (PfCDPK4) inhibitors that block the transmission of malaria to mosquitoes. Eur J Med Chem. 2014;74:562–73. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.12.048 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ranade RM, Zhang Z, Gillespie JR, Shibata S, Verlinde CL, Hol WG, et al. Inhibitors of methionyl-tRNA synthetase have potent activity against Giardia intestinalis trophozoites. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(11):7128–31. 10.1128/AAC.01573-15 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen CZ, Kulakova L, Southall N, Marugan JJ, Galkin A, Austin CP, et al. High-throughput Giardia lamblia viability assay using bioluminescent ATP content measurements. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55(2):667–75. 10.1128/AAC.00618-10 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Debnath A, Ndao M, Reed SL. Reprofiled drug targets ancient protozoans: drug discovery for parasitic diarrheal diseases. Gut Microbes. 2013;4(1):66–71. 10.4161/gmic.22596 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tejman-Yarden N, Miyamoto Y, Leitsch D, Santini J, Debnath A, Gut J, et al. A Reprofiled Drug, Auranofin, Is Effective against Metronidazole-Resistant Giardia lamblia. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2013;57(5):2029–35. 10.1128/AAC.01675-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Love MS, Beasley FC, Jumani RS, Wright TM, Chatterjee AK, Huston CD, et al. A high-throughput phenotypic screen identifies clofazimine as a potential treatment for cryptosporidiosis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11(2):e0005373 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005373 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vila T, Lopez-Ribot JL. Screening the Pathogen Box for Identification of Candida albicans Biofilm Inhibitors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;61(1). 10.1128/AAC.02006-16 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spalenka J, Escotte-Binet S, Bakiri A, Hubert J, Renault JH, Velard F, et al. Discovery of New Inhibitors of Toxoplasma gondii via the Pathogen Box. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018;62(2). 10.1128/AAC.01640-17 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Capparelli EV, Bricker-Ford R, Rogers MJ, McKerrow JH, Reed SL. Phase I Clinical Trial Results of Auranofin, a Novel Antiparasitic Agent. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;61(1). 10.1128/AAC.01947-16 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miyamoto Y, Eckmann L. Drug Development Against the Major Diarrhea-Causing Parasites of the Small Intestine, Cryptosporidium and Giardia. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:1208 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01208 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Garzon M, Pereira-da-Silva L, Seixas J, Papoila AL, Alves M. Subclinical Enteric Parasitic Infections and Growth Faltering in Infants in Sao Tome, Africa: A Birth Cohort Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(4). 10.3390/ijerph15040688 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abdel-Messih IA, Wierzba TF, Abu-Elyazeed R, Ibrahim AF, Ahmed SF, Kamal K, et al. Diarrhea associated with Cryptosporidium parvum among young children of the Nile River Delta in Egypt. J Trop Pediatrics. 2005;51(3):154–9. 10.1093/tropej/fmh105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gatei W, Wamae CN, Mbae C, Waruru A, Mulinge E, Waithera T, et al. Cryptosporidiosis: Prevalence, genotype analysis, and symptoms associated with infections in children in Kenya. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2006;75(1):78–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pham JK, Nosala C, Scott EY, Nguyen KF, Hagen KD, Starcevich HN, et al. Transcriptomic Profiling of High-Density Giardia Foci Encysting in the Murine Proximal Intestine. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2017;7:227 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00227 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang Z, Guan N, Li T, Mais DE, Wang M. Quality control of cell-based high-throughput drug screening. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B. 2012;2(5):429–38. 10.1016/j.apsb.2012.03.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lewis MD, Francisco AF, Taylor MC, Kelly JM. A new experimental model for assessing drug efficacy against Trypanosoma cruzi infection based on highly sensitive in vivo imaging. J Biomol Screen. 2015;20(1):36–43. 10.1177/1087057114552623 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nava-Zuazo C, Chavez-Silva F, Moo-Puc R, Chan-Bacab MJ, Ortega-Morales BO, Moreno-Diaz H, et al. 2-acylamino-5-nitro-1,3-thiazoles: preparation and in vitro bioevaluation against four neglected protozoan parasites. Bioorg Med Chem. 2014;22(5):1626–33. 10.1016/j.bmc.2014.01.029 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Amadi B, Mwiya M, Musuku J, Watuka A, Sianongo S, Ayoub A, et al. Effect of nitazoxanide on morbidity and mortality in Zambian children with cryptosporidiosis: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360(9343):1375–80. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11401-2 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stark D, Barratt J, Roberts T, Marriott D, Harkness J, Ellis J. A review of the clinical presentation of dientamoebiasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;82(4):614–9. 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0478 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Younis Y, Douelle F, Feng TS, Gonzalez Cabrera D, Le Manach C, Nchinda AT, et al. 3,5-Diaryl-2-aminopyridines as a novel class of orally active antimalarials demonstrating single dose cure in mice and clinical candidate potential. J Med Chem. 2012;55(7):3479–87. 10.1021/jm3001373 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Harbut MB, Vilcheze C, Luo XZ, Hensler ME, Guo H, Yang BY, et al. Auranofin exerts broad-spectrum bactericidal activities by targeting thiol-redox homeostasis. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(14):4453–8. 10.1073/pnas.1504022112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Mean percentage inhibition was calculated as the inhibition when compared to the mean values of wells grown with 1 μL DMSO in place of compound.

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.