Abstract

This article answers several questions: Which subgroups of the U.S. population—designated by race, ethnicity, family structure, educational status, income, wealth, consumption, or other characteristics—appear to be particularly vulnerable to a lack of economic opportunity based on household characteristics of the family and its children? To what degree does poor access to economic advancement appear to reflect low income or wealth, or do additional barriers contribute substantially to some subgroups’ limited opportunities? Similarly, what advantages accrue to high-income and other privileged groups, such as those born into a well-established married family? What does current research tell us about the mechanisms through which barriers operate and policies that might be effective in reducing them?

Keywords: opportunity, black, high school dropout, unmarried mother, income, wealth, consumption

Economic opportunity and mobility are not the same thing. But without more opportunity, we are unlikely to see a systematic increase in social and economic intergenerational mobility (IGM) (see Jencks and Tach 2006; Smeeding 2014). Policymakers concerned about these issues should be thinking both about how to overcome barriers to create more opportunity for those left behind, and about how to overcome barriers to make greater opportunity translate into more mobility. Not everyone takes advantage of opportunities and often personal agency leads to less mobility, even when better opportunities are available, for example, when young, unmarried partners have a baby (see Sawhill 2014). Social scientists therefore need a framework to trace out progress against reducing barriers that inhibit increases in opportunity and IGM, especially for groups who have multiple disadvantages.

The traditional literature on the study of IGM does not help us much in creating such a framework. Most scholarly discussions focus on the inheritance of income mobility in past decades. In other words, they ask how the relative economic status of grown children (ages thirty-five to forty) compares with their parents’ status when they were young (between 1966 and 1979). Some of these studies tell us that overall mobility has not declined in recent decades, which is not surprising for an economy where income gains were widespread across the population and living standards rose across the distribution up until the 1980s. We also know from national and cross-national research the great deal of stickiness at both the top and bottom of the relative IGM matrix of parental and child incomes: the children of the rich tend to remain rich and the children of the poor, poor. Further, we know that the resource levels separating poor from rich have grown in magnitude since the inequality generation was born in the 1980s, and that absolute mobility for the children of the bottom quintile has fallen since 1980 as returns to education and assortative mating have strengthened the differences between the top and bottom of the family income distributions (Autor 2014; Schwartz 2013; McLanahan and Jacobsen 2014). Although the economic landscape has changed since the 1970s, the experiences of older cohorts still may be important—even if the intergenerational mobility of older baby boomers may look very different from that of the post–baby boom Generation X or Millennials (those born between 1980 and 2000), and the generation born since—because they are the parents of today’s children.

If we are to push for policies to enhance opportunity and improve IGM for the next generation, we need to look at the factors that are affecting today’s and tomorrow’s children’s chances at upward mobility. Borrowing from William Julius Wilson (1987), we are concerned here with upward mobility among only truly disadvantaged families with multiple obstacles facing them and their children. In our analyses, we sometimes refer to the truly advantaged at the top of the social and economic heap. A life cycle approach can help us assess trajectories by setting up markers of success or failure along the road to greater IGM from birth through adulthood. As we view IGM from this perspective, we are able to observe factors that affect parents and children’s opportunities and mobility. It allows us to identify the obstacles that vulnerable groups face and to focus on policies to aid them across the life course to reach the American Dream of a stable middle-class lifestyle.

In this article, I set out to apply the life cycle model to determine which subgroups of the U.S. population—designated by race, family structure, and education, as well as by income, consumption, and wealth—appear to be particularly vulnerable to a lack of economic opportunity. I assess the social and economic circumstances that create barriers to opportunity and mobility and examine how they contribute to limit opportunities for the vulnerable. These barriers are not just low economic resources, but also include a set of mechanisms and processes that either discourage or encourage opportunity. I therefore turn to policies that might be effective in reducing these barriers.

From this perspective, at least three sets of forces influence social mobility, as enablers for some and as barriers for others, all of which have changed in the decades since the 1970s:

Family. Family instability and insecurity create barriers for many disadvantaged families, while good parenting skills and abundant resources give upper-income and wealthy families a large advantage. We are increasingly seeing a parenting gap or diverging destinies, where parents at the top are able to spend both more and better time and more money on activities to promote their child’s educational and social development, buy into safe neighborhoods with good schools, and so on, than lower-income parents.

Markets, especially labor markets. Individuals deploy their skills in markets to improve family economic resources, but the returns to the skilled and the educated have blossomed, whereas those to the unskilled and undereducated have fallen. Both income and wealth matter, because they limit consumption and education spending on children’s enrichment and school opportunities for the disadvantaged while enhancing the chances of the rich and well educated.

Public policy and social institutions. Policy and social institutions are important forces because they create opportunities for some children and reduce them for others. We need to know how to reduce growing class gaps, especially in family formation, family resources, health, education, and neighborhoods.

The family income package (Rainwater and Smeeding 2003) is determined by these three institutions, all of which play a role in IGM. Family, markets, and policy and social institutions interact with one another and together determine both opportunity and mobility. They serve as resources that can play especially large roles at strategic transfer points in the life course (that is, places where more investments from parents or institutions make a big difference in child outcomes). Some come early, such as parent-child interactions and the development of cognitive skills and character (social competency, perseverance, and good habits) at home and in preschool. Some come from schooling choices, and some come later on through paying for college, providing funding for a child to experience an unpaid internship, direct job provision in family firms (nepotism), or helping children enter the housing market.

Of course, stagnant earnings and incomes in the 2000s suggest that the barriers we identify are a worry for the absolute mobility of the strapped middle classes, not just poor families with children. The difference between a poverty budget that allots just enough to feed, clothe, and shelter one’s children, and a budget that allows for the higher cost of a “well-raised” child is substantial. Consideration is due as well to the important issue of the sharing of child-rearing costs between parents/families and the public sector. Hence mobility is a middle-class issue as well as a poor family issue.

Finally, the belief in the opportunity to reach the American Dream is in question today. It once was a strongly and widely held view that if you worked hard and played by the rules, you could get ahead in America. But this has changed. Today, only 42 percent of Americans agree that if you work hard you will get ahead. Also, notably, fewer than 33 percent of African Americans believe that hard work gets you ahead today, and one in seven (14 percent) never believed it (Jones, Cox, and Navarro-Rivera 2014). More to the point for IGM analyses, half of Americans believe that their own generation is better off financially than their children’s generation will be. Most Americans (55 percent) believe that one of the biggest problems in the country is that not everyone is given an equal chance to succeed in life. Other recent surveys have shown the same result—parents’ confidence in their children being better off than they are is at or near the lowest point ever recorded.1 Overall, we must conclude that Americans are expressing significant concerns about the economic future for themselves and their children, and about their beliefs in America being an equal opportunity society. This is especially the case for the vulnerable groups we focus on here.

LIFE CYCLE MODEL AND VULNERABLE POPULATIONS

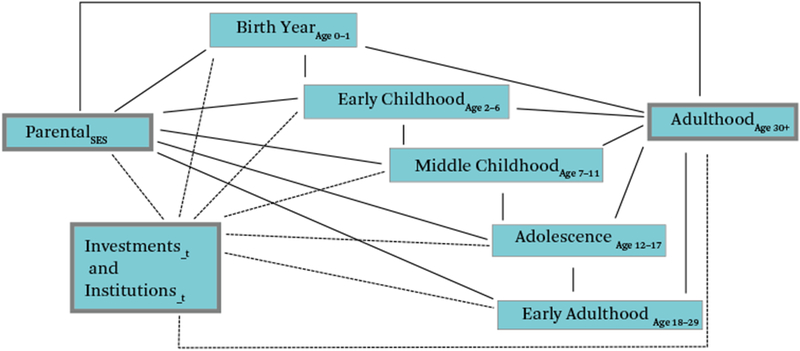

A recent pair of cross-national research volumes took the life cycle approach to studying the influence of parental education and income on child outcomes from birth to age thirty (Smeeding, Erikson, and Jäntti 2011; Ermisch, Jäntti, and Smeeding 2012). Figure 1 summarizes our model of the life course process from birth to adulthood for one generation, moving from origin (parental social economic status, or SES) to destination (children’s adulthood SES) across six life stages. Parental investments, income, wealth, and social institutions affect each step of the life course, where intermediate gains or losses are measured in multiple domains.

Figure 1.

A Model of Intergenerational Transmission of Advantage by Life Stage

Source: Ermisch, Jäntti, and Smeeding 2012, figure 1.2.

This structure allowed us to observe different cohorts at different times, with every outcome in every country ranked by adult educational differences. Taken as a whole, these cross-national studies reveal a powerful effect of parental SES on child outcomes in health, cognitive testing, sociobehavioral outcomes, school achievement, and adult social and economic outcomes. Examination of standardized outputs across eleven countries found a definite and universal pattern that the higher the adult SES as measured by educational attainment, the larger the positive effect on children’s outcomes, and vice versa. These effects were observed from birth onward and they did not diminish as children matured into adulthood. Moreover, the slopes of the relationships between parental SES and child outcomes were steepest in the United States. But not all the steps were filled in for any one country, save Sweden (see Mood, Jonsson, and Bihagen 2012), and most outcomes were measured for only one cohort. This method proved a useful way to assess cross-national differences in IGM, and the same structure is also a useful way to assess how various cohorts of younger generation U.S. children will be affected by growing gaps in parental SES (education, earnings, wealth, and income) in our own nation.

Another domestic project approaching this question in the same way began at just about the same time the international work was published. The objective was to ask what one needs to accomplish at various life stages to achieve the American Dream. The Brookings-Urban Institute-Child Trends Social Genome Model (SGM) has now estimated a set of factors for assessing progress toward reaching the American Dream.2 That is, the model maps out the steps one needs to take across the life course to progress to become a family with incomes at three times the poverty line in middle age, which is more or less making it well into the middle-income quintile or higher.

Both of these models and steps provide a framework to examine the parental-investment and institutional forces that boost life chances for some and provide barriers for others across the life cycle. The steps might be thought of as hurdles to overcome or descriptive markers of life progress and processes. One can still succeed if one stumbles at any one stage, but momentum and cumulative forces propel one along given courses. Richard Reeves and Isabel Sawhill (2015) review the overall patterns and contours of the SGM and how progress or lack thereof in each of these stages has affected recent generations. Here we use a similar framework to assess the characteristics of the most disadvantaged and vulnerable populations who have an especially hard time negotiating the life cycle process.

Reeves and Sawhill (2015) argue that overall social mobility is unacceptably low in the United States today: between 36 and 40 percent of those born into the bottom quintile remain there as adults, versus 30 to 34 percent of those born into the top quintile staying at the top when they grow up.3 They define the parameters of their SGM model using the 1979 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY) for adults and the Children of the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (CNLSY) for the children of these adults as they move through the life course. These are the best parameters we have for assessing mobility outcomes and how children move through the various life course steps.4

Among the most striking descriptive findings in the SGM literature are the vast divisions in mobility across family types by race, family status/stability, and education. This article dwells on vulnerable families and children differentiated by race, family status, and education, and I limit my interest to the most vulnerable and disadvantaged among these. In particular, I focus on adult outcomes for black children, children coming from families with low levels of adult education, and children growing up in single-parent and complex families, all of whose absolute and relative mobility out of the bottom quintile is the most pressing matter for IGM policy.

Table 1 is based on the Social Genome Model.5 It presents the stark differences among the most disadvantaged children (those coming from the bottom income quintile) in the income status they have achieved when they are observed as adults. Although the results are mainly about the mobility of the adult generation today, I argue that the circumstances of children in these groups suggest even lower mobility for the current generation born into these same circumstances. Some low-income groups are obviously more successful than others in reaching the middle class (third quintile) or above. Half the black children born into the bottom quintile remained there in adulthood, whereas fewer than one in four whites in this cohort did so. Only 10 percent of low-income blacks made it to the top two income quintiles as adults, beyond the middle class, but 35 percent of disadvantaged white children did, despite their parents’ starting in the bottom quintile.

Table 1.

Distribution of Adult Outcomes (Income Quintile as an Adult) for Children Born into Bottom Quintile

| Percent in Each Adult Income Quintile*: |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bottom | Next | Middle | Top Two | |

|

| ||||

| Characteristics | 20 | 20 | 20 | 40 |

| Race | ||||

| Black | 51 | 27 | 12 | 10 |

| (White) | (23) | (19) | (23) | (35) |

| Family status of mother | ||||

| Never-married | 50 | 24 | 13 | 14 |

| Discontinuously married | 32 | 24 | 20 | 24 |

| (Continuously married) | (17) | (23) | (20) | (40) |

| Educational status of parent | ||||

| Less than high school | 54 | 26 | 13 | 6 |

| High school degree and some college | 30 | 24 | 18 | 26 |

| (College graduate) | (16) | (17) | (26) | (41) |

Source: Author’s calculations based on the Brookings Institution Social Genome Model.

Each row adds to 100 percent (except for rounding); under equal opportunity a full 20 percent of each group would be in each quintile.

Parental differences in family status and structure mirror race differences, in that 50 percent of the low-income children who grew up with never-married parents remained in the bottom quintile as adults, and only 14 percent rose above the middle class to one of the top two quintiles as adults. Those from the bottom who were in married-parent families at some point do a little better, but these children still had a 56 percent chance of ending up in the bottom two quintiles when they grow up. Poor children who grew up with continuously married parents did much better, though marriage is now rapidly shrinking in this group for those with less than a college education (Cherlin 2014). A general pattern of greater upward mobility is seen as we move up the family status scale to the continuously married.

Failure of an adult to graduate high school, even with a GED (general educational development) certificate, greatly depresses upward mobility rates (Murnane 2013). Bottom income quintile children in table 1 who were raised by a parent without a high school diploma had a 54 percent chance of remaining in the bottom quintile as adults, and only 6 percent made it to the top two quintiles in this cohort. Among low-income children whose parents achieved high school degrees by adulthood, 54 percent ended up in the bottom 40 percent of their adult income distribution. The bottom-quintile children who grew up in households headed by a college graduate had only a 30 percent chance of ending up in the bottom two quintiles when they reached adulthood, and a 41 percent chance of making it into the top quintile in their cohort as adults. Higher levels of education and degree completion among low-income parents are clearly associated with higher rates of upward mobility for their children when they reach adulthood.

Summarizing table 1, in the end, what do we have? At least half of all bottom-quintile children who were African American, whose parents did not finish high school, or who grew up with a never-married mother, remained in the bottom quintile as adults. Three-quarters or more (74, 78, and 80 percent, respectively) ended up in the bottom 40 percent of the income distribution as adults, thereby failing to realize the American Dream.6 Moreover, the three groups in table 1 overlap, making it difficult to separate effects by race, family status, or parental education. In fact, future research needs to move beyond these bivariate associations and stratify by more than one disadvantage to understand mobility for those with multiple disadvantages. For instance, being born to a black unwed mother who grew up in a low-income family and who did not complete high school, and being born to an upper-income class married, white, college-graduate mother are the opposite ends of the “diverging destinies” for children in this cohort (McLanahan 2004; McLanahan and Jacobsen 2014).

THE ROLE OF MONEY: INCOME, WEALTH, AND CONSUMPTION

Money matters for opportunity and mobility, especially in America. Low incomes as a child and as an adult are one key element of vulnerability, as seen in table 1. For those children living in the bottom quintile, especially when very young or for an extended period, low incomes have a well-established negative impact on brain development, social-emotional development, and lifelong outcomes. The effects range all the way from negative impacts on educational success and employment to longer-term health effects, such as heart disease and stress-related diseases showing up in adulthood that can be tracked to extended experiences of (economic) deprivation, trauma, and stress as a child (Smeeding 2016).

At the same time, a little more money makes a big difference to children on the bottom rungs of the ladder. A host of recent studies have shown that refundable tax credits—the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), the refundable portion of the Child Tax Credit (CTC), and the Additional Child Tax Credit (ACTC)—improve child outcomes in health, including birth outcomes for mothers, and the learning of young children (Evans and Garthwaite 2014; Hoynes, Miller, and Simon 2015; Dahl and Lochner 2012; Milligan and Stabile 2009). Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) receipt during childhood is also shown to improve child health and learning outcomes, and to foster significant reduction in the incidence of metabolic syndrome (obesity, high blood pressure, and diabetes) and, for women, an increase in economic self-sufficiency (Almond, Hoynes, and Schanzenbach 2011; Hoynes, Schanzenbach, and Almond 2014; Hoynes, Miller, and Simon 2015). More generally, in childhood, higher incomes for low-income families have a large number of positive effects (for summaries, see Duncan, Morris, and Rodrigues 2011; Duncan, Magnuson, and Votruba-Drzal 2014; Cooper and Stewart 2013). The simple summary is that higher benefits from the EITC, CTC/ACTC, and SNAP lead to better outcomes for children and parents, especially positive longer-term developmental effects on low-income children.

Mobility also depends on how far apart the incomes of parents are. Because absolute differences between the top and bottom incomes of parents have changed a great deal since 1979, the stakes for remaining at the bottom or the top of the distribution are now much larger. Congressional Budget Office estimates of after-tax and transfer incomes show that the gap in incomes between the richest and poorest quintiles of families with children rose by almost $112,000 or 115 percent from 1979 to 2010 (see Smeeding 2016; Congressional Budget Office 2013). This is a huge difference across a fairly short time span. The main basis of income for parents and their children is employment and earnings. If anything, the Great Recession has made differences in economic status much worse, as we see increasingly stark differences in employment and wages by education and age, with earnings gains mainly above the bachelor’s degree level where the IGM correlation of parents’ and children’s education is highest (Torche 2011). Cross-national research suggests that the premiums in pay for the highest educated are largest in the United States as well, meaning that the minority who reach college graduation and beyond do better in the U.S. labor market than their less-educated countrymen (Autor 2014; Blanden et al. 2014; Ermisch, Jäntti, and Smeeding 2012).

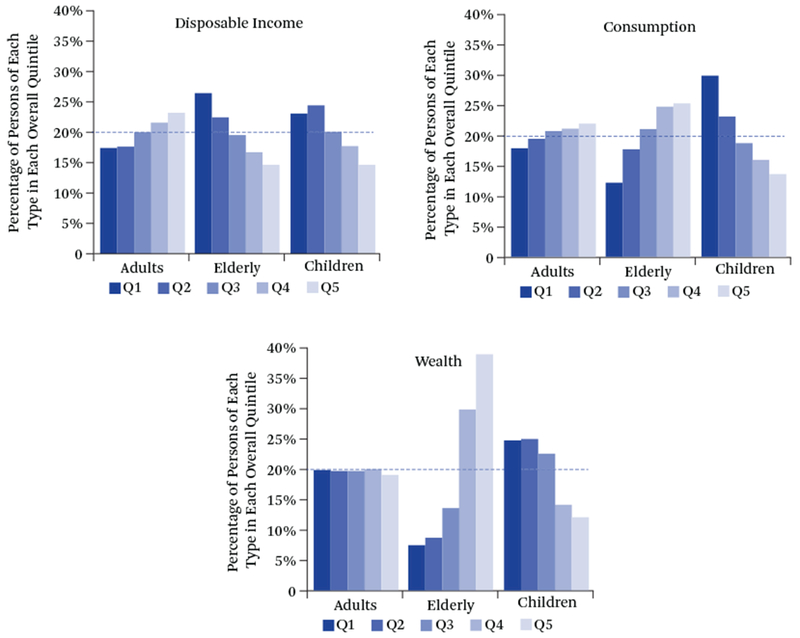

Money matters, but it is not just about income; consumption and wealth also matter. In figure 2 we document how the demography of income, consumption, and wealth differs among various age groups. This figure ranks distributions so that 20 percent of all people are in each quintile by each measure, and then focuses on where adults, elders, and children (as measured by their family variables) are located in each distribution (equivalence-scale adjusted) in 2010. In other words, if we were to look at the overall distribution of all people by any one of these measures, exactly 20 percent would be in each quintile. Those who are less likely to be well off are overrepresented in the bottom quintiles, and those who are better off are more heavily represented in the top quintiles. The takeaway is that children and elders in particular are located in very different parts of the distribution in terms of wealth and consumption compared to income. The position of children in the lowest 40 percent of each distribution, especially the consumption and wealth distributions, should cause concern about their upward mobility compared with that of the minority of advantaged children who are at the top of the wealth and consumption scales and whose grandparents as well as parents can help them overcome financial obstacles to upward mobility. Indeed, Janet Yellen (2014, figure 8) shows that the mean net worth of the top 5 percent of families with children was greater than $3 million in 2013, versus $500 or less for the bottom half of all families with children. And those children at the very bottom of the income distribution today are in large part the sons and daughters of the adults seen in the first two columns (first two quintiles) in table 1.

Figure 2.

Demography of Inequality by Age, 2010

Source: Fisher et al. 2015.

Note: The data are for number of persons by age: children (under age eighteen); elders (age sixty-five and over), so person weighted. Overall inequality is not shown, but if so, it would be at 20 percent of the population overall in each quintile. Each quintile is ranked by its own measure (income, consumption, or wealth) with an equivalence scale adjustment using the square root of household size. Adults include those currently living with elders or children under age eighteen, as well as childless adults.

None of the current analyses of inequality have yet captured the full effect of net worth (assets, debt, and wealth) on consumption or income by considering all three measures of well-being simultaneously for the same households, though we know that each gives a different and important perspective on the distribution of economic well-being, and likely a different outcome when considering the effects of inequality on IGM.7 Wealth is the most elusive, because it is a stock and not a flow. Evidence from the Survey of Consumer Finances (Yellen 2014, figure 3) suggests rising wealth inequality in the United States, the top 5 percent increasing their shares and the others losing out, including a precipitous decline in mean wealth for the bottom half of the wealth distribution, where most U.S. children and their parents increasingly can be found (see figure 2). Among the bottom half of all wealth holders, mean wealth fell from $32,000 to $12,000 between 2007 and 2013 (Yellen 2014, figure 4).

Fabian Pfeffer and Martin Hällsten (2012) and Timothy Smeeding (2016) argue that the impact of parental wealth on children works through its insurance effects (think of a “private family safety net”). High family wealth creates the ability to finance 529s and pre-fund college with tax-free interest and capital gains; as well as the greater ability to do more for well-timed intervivos transfers, especially for the following generations (Kirkegaard 2015; Banerjee 2015). Richard Reeves (2014) and Smeeding (2014) refer to this as the glass floor effect. Wealthy families (parents and grandparents) pay college tuition, including graduate school, leaving their graduating children and grandchildren debt-free after graduation. They subsidize rent and provide apprenticeship funds for children to move to high income-growth areas without jobs. Often they can and do provide jobs directly in family-run businesses (Bingley, Corak, and Westergard-Nielson 2012; Corak and Piraino 2011; Stinson and Wignall 2014; Yellen 2014). And they pass on homeownership subsidies to capture upswings in real estate by cosigning low-interest mortgages for children who do not qualify for the best rates. Of course, they also provide other glass floor advantages, such as good lawyers, subsidized travel for children’s human capital building, good schools, and safe neighborhoods. Moreover, if we omit wealth or lack of it from our mobility analyses, we may be attributing some important true wealth effects to demographic variables like marriage or to race.

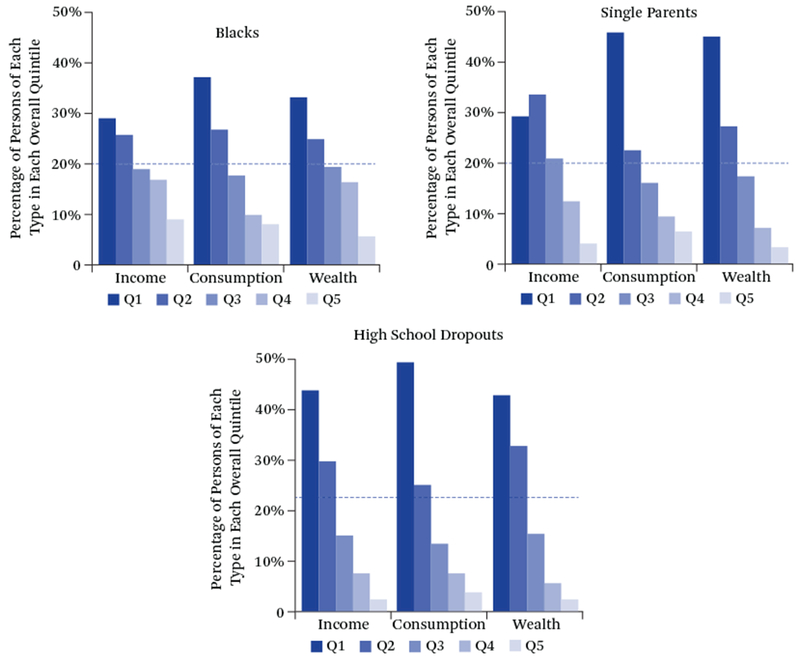

What about differences in income, wealth, and consumption among our key disadvantaged groups? In a recent paper, Jonathan Fisher and his colleagues (2015, figure 3) map rankings and patterns of income, consumption, and wealth for each of our vulnerable groups using the same method as in figure 2. Once again, an equal distribution across the three spectrums (income, consumption, and wealth) would show 20 percent of each group in each quintile. The picture is quite different in each case in figure 2, however. The income and demographic groupings correspond to those in table 1, but now we add consumption and wealth to the picture.8

Racial differences are stark. Considering the relative consumption and wealth positions of African Americans makes their economic status even worse than when we consider income alone. Ranking children’s family status, we find even more skewed results. Tom Shapiro, Tatjana Meschede, and Sam Osoro (2013) also examine black and white wealth using the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID), and find that the total wealth gap between white and black families nearly tripled in twenty-five years, from $85,000 in 1984 to $236,500 in 2009. The Great Recession was particularly devastating to the young black middle class because they were the ones who bought homes at the top of the market, between 2000 and 2006, often with subprime loans. Differences in housing wealth and homeownership, but also income, unemployment, inheritance, and financial transfers, all help explain this gap.

Fisher and his colleagues (2015) are unable to differentiate between never-married mothers and their discontinuously married counterparts, but it is clear that children being raised by single parents in 2010 were predominately in the bottom 40 percent in each distribution (see also Painter, Frech, and Williams 2015). Perhaps the most differential rankings have to do with the educational status of adults, where high school dropouts are most heavily clustered in the bottom 40 percent of each distribution.

These snapshots of economic status allow us to look at the three dimensions of economic inequality for our three vulnerable parental groups whose experiences and achievements when growing up in the bottom quintiles are shown in table 1 and whose children we are most concerned about here. For the most part, net worth and consumption differences reinforce income differences, suggesting that the disadvantaged groups in whom we are most interested—blacks, nonmarried parents, and those with a high school education or less—find themselves in very poor economic positions by each index. Although a small proportion of children do well in terms of income, wealth, and consumption (figure 2), mostly they live with college-educated white families. The most vulnerable children are found near the bottom end of each distribution by each characteristic. Obviously the poor and lower middle-income groups are at risk simply because they have too little income (consumption and wealth) to afford the neighborhoods, schools, lifestyles, and other elements of raising a child well. Hence, lack of economic resources is correlated with many other disadvantages for these adults and their children.

THE TRULY DISADVANTAGED AND VULNERABLE

Most of our knowledge of group-specific mobility comes from the panel datasets and models based on them, and which have been part and parcel of economic and social research on mobility. Although these data cannot be used directly as policy guides, they have helped identify groups who have been historically likely to be vulnerable and in need of help to create and seize opportunities for their children (see table 1 and figure 3). As shown, vulnerabilities come in clumps, as do advantages, making it hard to apportion the influence of separate factors, despite the fact that each separate grouping has important negative consequences for opportunity and mobility (for an attempt to separate the effects of race from SES, see VanderWeele and Robinson 2014).

Figure 3.

Vulnerable Groups in 2010

Source: Fisher et al. 2015.

Note: The data are for number of persons by race, all blacks; all children and adults who are single parents with children under age eighteen; and all adults (age twenty-one and over) who did not finish high school. Each quintile is ranked by its own measure (income, consumption, or wealth) for the whole population with an equivalence scale adjustment using the square root of household size. Hence, the figure shows where each group is located in the overall distributions of income, consumption, and wealth.

Race and Incarceration

African Americans are much less likely to succeed even holding multiple parental status variables constant. Research on differences in mobility between blacks and whites reveals stark variances. On average, blacks experience less upward mobility and whites less downward mobility, corroborating the Social Genome and economic rankings shown above. In fact, whites are on average 20 to 30 percentage points more likely to experience upward mobility than blacks are (Mazumder 2014). Studies of older cohorts find that almost 50 percent of black children born into the bottom 20 percent of the income distribution were in the same position as adults, but that only 23 percent of white children born in that quintile were (see table 1; see also Mazumder 2014; Sawhill, Winship, and Grannis 2012; Isaacs, Sawhill, and Haskins 2008; Acs 2011; Hertz 2005).9 A range of personal and background characteristics—such as parental occupational status, individual educational attainment, and marital status—help explain this race gap. But, taking into account differences in Armed Forces Qualification Test (AFQT) scores between white and black men explains most of the variation in results, giving us some hope that educational treatments might improve black mobility outcomes in general if they can raise AFQT scores and college graduation rates (Mazumder 2014).10

Although family structure, parental and personal education, family background, income, and neighborhood all played a role in these disturbing findings, one important source of downward mobility for black men remains largely unaccounted for. Much of low black mobility, which is not yet fully recorded because of the age of the individuals involved, is affected by the spectacular rise in imprisonment in America between 1970 and 2010, and its negative long-term economic consequences for less-educated black men and their families, who are now mainly young or middle-aged adults (Pettit 2012; Pager 2003; Western and Pettit 2010; Pew Charitable Trusts 2010).

A thorough National Academy of Sciences report (Travis, Western, and Redburn 2014) concluded that among recent cohorts of black men, about one in five who have never been to college have served time in state or federal prison at some point in their lives. Among black male high school dropouts, about two-thirds have a prison record by age thirty—more than twice the rate for their white counterparts. IGM is most severely limited for those who have been in the prison system. In 2012, the overall correctional population—those incarcerated in prison, jail, or being supervised on parole—was about seven million persons, mainly originating from the most disadvantaged segments of the population. In 2007, before the onset of the Great Recession, only half of the ex-incarcerated were able to find jobs (Schmitt and Ware 2010).

Those most affected by incarceration are mainly minority (especially black) men under age forty who are poorly educated, often have mental illness issues, and lack formal work preparation or experience. These coincidental conditions and attributes make it difficult to precisely estimate effects of incarceration, as these conditions are each liable to reduce mobility for this population, while negatively affecting their communities and families. But even given these other barriers to progress, an incarceration history adds to the negative effects of poor schooling and race in ways we have just begun to explore. In fact, the growth of incarceration rates among black men in recent decades combined with the sharp drop in black employment rates during the Great Recession have left most black men in an economic position relative to white men that is really no better than in 1970 (Neal and Rick 2014). This of course affects intragenerational mobility as well: among former inmates in the bottom quarter of the earnings distribution in 1986, two-thirds remained there in 2006, twice the rate of nonincarcerated men. Further, only 2 percent of previously incarcerated men who started in the bottom fifth of the earnings distribution made it to the top fifth twenty years later, against 15 percent of all men who started at the bottom but were never incarcerated (Pew Charitable Trusts 2010).

Most of the men and women in prison have children. Nationally, about 53 percent of men and 61 percent of women in the U.S. prison population are parents (Maruschak, Glaze, and Mumola 2010). Christopher Wildeman (2009) and Becky Pettit (2012) calculate the probability that a child would experience a parent’s being sent to prison by the child’s teenage years. Among black children, parental imprisonment in the 1990 birth cohort was about 25 percent. Further, although 15 percent of white children whose parents had not completed high school had had a parent sent to prison by age seventeen, 62 percent of their African American counterparts experienced some time with one parent in jail or prison (Wakefield and Wildeman 2013). Of course, these recent cohorts are too young to fully capture the effect of parental imprisonment, but the numbers are stunningly large and new evidence on the effects of parental incarceration on children is beginning to emerge (Lee, Fang, and Luo 2013; Hagan and Foster 2012).

Incarceration is highly correlated with family hardship, including housing insecurity and behavioral problems in children, especially boys. Prison stresses relationships within families and reduces child involvement postrelease. Studies that focus exclusively on incarcerated men have found that partners and children of male prisoners are particularly likely to experience adverse outcomes if the men were positively involved with their families prior to incarceration. But only about four in ten men reported living with their children before incarceration and studies are mixed on the effects of child separation from incarcerated parents, because, for example, being away from violent men can improve children’s life chances (Travis, Western, and Redburn 2014, chapter 9). Many of these differences are hard to assess because of difficulty in following young men in and out of prison, especially among recent cohorts. Any new research on IGM ought to make such study a priority, because very few formerly incarcerated individuals are tracked by our datasets.

Declining manufacturing sector employment in inner cities accompanied the prison boom, as Wilson classically describes (1987, 1996), where the outmigration of whites and the rising black middle class left behind pockets of concentrated disadvantage. These poor, racially segregated neighborhoods are characterized not just by high rates of poverty and crime but also high rates of unemployment, single parenthood, and multiple-partner fertility (adults living with children from two or more partners). These neighborhoods were heavily populated by blacks, but Charles Murray (2012) shows similar effects appearing in former white middle-class neighborhoods as well.

FAMILY STATUS, STABILITY, AND PARENTING

Family status and stability as well as parenting practices may matter even more than incomes for equality of opportunity and IGM. As Sara McLanahan and Wade Jacobsen have established (McLanahan 2004; McLanahan and Jacobsen 2014), we are seeing a growing class divide in America— in income, in education, and in family formation. Children born into continuously married families have much better economic mobility than those in single-parent families, especially unmarried mothers, or families where the parents break up (see table 1). Indeed, family differences begin at birth. It is often useful to illustrate the middle ground of an issue by looking at its endpoints. If we examine both what is considered to be the best process by which to become a parent and the worst process, we can better understand the point of diverging destinies. The “best” way to become a parent for men and women alike is through living the American Dream: finish your schooling, find a decent job, find a partner you can rely on, make plans for a future together including marriage as a commitment device (see Lundberg and Pollak 2013), and then have a baby. Following this process will likely mean that parents are middle class or better and close to the age of thirty when a first child is born.11 Parents who follow this process are (in some ways by definition) older, more educated, and more likely to have a stable marriage. They have better parenting skills, smaller families, and more income, benefits, and assets to support their children. These characteristics translate almost directly into more opportunities for their children.

At the other end of the spectrum, the “worst” way to become a parent is to have a baby as an adolescent or young adult between the ages of sixteen and twenty-two, preceding all the other steps. These parents typically have not finished schooling, do not have a steady or well-paying job, do not have a stable marriage or steady partnership, and likely never had a life plan for raising their children. They have less education (high school or less), are younger and less skilled, have lower wages and fewer benefits, have far less partnership experience, and will have more multiple-partner fertility. The result is less social and economic stability and fewer resources and opportunities for their children (Smeeding, Garfinkel, and Mincy 2011; Smeeding 2016).

More than 40 percent of all births in 2013 were out of wedlock, up from 19 percent in 1980. For those under age thirty, half of all births were to unmarried mothers (Hamilton et al. 2014). For these single women under thirty, almost 70 percent of births are unplanned as young adults “drift” into parenthood because of failed contraception or ambivalence about school and life goals (Sawhill 2014). Black out-of-wedlock births have risen from 57 percent in 1980 to more than 70 percent in 2013 (Hamilton et al. 2014). Marriage rates have never been high for blacks but are now falling, as they are for noncollege graduate whites (Murray 2012; Cherlin 2014). The fraction of never-married mothers with children under age eighteen is more than 20 percent for those who did not graduate secondary school and 15 percent for high school graduates, as compared to 3 percent for those with a bachelor’s degree or more (Smeeding 2016). Not only is out-of-wedlock childbearing highest among the least educated, but these births occur mainly to younger mothers, most of whom are poor or near poor and have unstable living conditions in terms of both partners and housing (Edin, DeLuca, and Owens 2012; Tach 2015). Moreover, these mothers have more children per woman than the average mother over her lifetime (Smeeding, Garfinkel, and Mincy 2011). In contrast, well-educated parents have fewer children later (in marriage) under much better economic circumstances (McLanahan and Jacobsen 2014; Sawhill 2014).

Family complexity and instability are detrimental to upward mobility, but are also high among unmarried parents. In 2010, 20 percent of all births and roughly half of all births to unmarried mothers were to cohabiting couples at the time of a focal child’s birth (Perelli-Harris et al. 2010). These families are highly unstable, however, almost 80 percent having a different partner by the time the child reaches age fifteen (Andersson 2002). Additionally, 67 percent of all unmarried cohabiting parents had found another partner within five years of the breakup (Andersson 2002). Multiple-partner fertility also comes into play here (Carlson and Furstenberg 2006). The Fragile Families data, from a sample of urban births, mainly among the vulnerable groups we emphasize here, finds that 79 percent of unmarried parents of the focal child have had a child with another partner within nine years of the focal birth. Among the married births, 25 percent had another child with another partner over this period (Carlson et al. 2013). Being raised by continuously married parents has a strong correlation with upward mobility for black children, but far too few of them grow up in such circumstances (Mazumder 2012).

Parenting is also highly unequal and parental endowments of skills are also important in determining life opportunities. More-educated, higher-income parents often have more parenting skills than their lower-income, less-educated counterparts. Hence, some types of skills training may offer overlapping benefits for parenting and the labor soft skills such as conflict resolution or knowing how to respond to setbacks, which also are better taught by highly educated parents (Heckman and Mosso 2014). High-skill parents not only realize the value of education, but also make every effort to make sure their children succeed in reaching a high level of educational attainment. In contrast, in the face of low education, family instability, complexity, and low income, most unmarried mothers live stressful lives that are not good for themselves or their children (Aizer and Currie 2014). For instance, hours spent reading to a young child or talking with a young child is where large differences in early language development begin and which also make a big difference in mobility outcomes. Various studies document that time spent with young children in reading and personal interaction is much more developmentally oriented in older and more educated married-couple families than in younger, single, unmarried-mother families (Kalil, Ryan, and Corey 2012; Phillips 2011). Using a measure of parenting quality, Richard Reeves and Kimberly Howard (2013) establish that the children of lowest quartile parents do worse at every stage of the Social Genome Model compared with highest quartile parents, with differences in success rates between these groups on the order of 30 to 45 percent at each life stage.

EDUCATION

The final at-risk groups are those without a normal high school diploma, including those with a GED degree or less, by age thirty.12 Formal schooling is the major vehicle for a child’s upward mobility; but those who have not done well in school themselves will have a much harder time navigating school choices and embracing the elements of school success for their own children. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (2014) has singled out the United States as being particularly deficient in one measure: the chances are greater than 70 percent that an American will not attend a four-year college if his or her parents do not have a college degree. The structure of our education system, not just secondary schools and colleges, but also early childhood education (ECE) and preschools and career and technical education (CTE) systems, has a large effect on who succeeds and who does not.

The correlation between parental and child education has been studied at least back through Gary Becker and Nigel Tomes (1986). Their model, and subsequent tests by others, establish that intergenerational correlations in socioeconomic status can arise from the greater ability of richer parents to invest in their children’s human capital, from genetic or cultural inheritance, or from all of the above (Solon 2014). Because these different sources of intergenerational status transmission produce similar empirical results, distinguishing those processes from each other is a difficult task. The literature has established that large gaps exist in early childhood education and in school readiness by parental education and income, which are more pronounced in the United States than in other Anglo nations (Waldfogel and Washbrook 2011).

We also know that these gaps are larger now than in the past, in part because a good share of consumption among parents at the top end of the distribution is related to developmentally oriented goods and activities; indeed almost seven times as much is spent per child in the top than at the bottom (Kaushal, Magnuson, and Waldfogel 2011).13 We also know that high-quality ECE programs are critical for disadvantaged children. Good preschools offer children productive teacher-child interactions, encouragement from teachers, and opportunities to engage with varied materials. Teacher quality and retention are also key ingredients for producing better outcomes for disadvantaged children. But these conditions are hard to establish or maintain in low-income areas (Magnuson and Duncan 2015).

Cross-national research in Denmark and France, where universal ECE is the norm, shows that effective high-quality preschools do reduce the gaps in achievement between children from high- and low-education backgrounds. But the remaining differences in both cognitive and behavioral outcomes are still significant when outcomes are ranked by parental education and income (Bingley, Corak, and Westergaard-Nielsen 2012; Dumas and Lefranc 2012). This significance suggests that though ECE can improve opportunity and mobility from the bottom, it is not by itself a magic bullet for desirable levels of IGM.

We also know that a child should accumulate human capital in elementary and middle school such that reading, math, and social-emotional skills are at acceptable levels to take full advantage of secondary school. Evidence from the Brookings Institution, however, reveals that 38 percent of children cannot cross this adequacy bar by fifth grade (Sawhill, Winship, and Grannis 2012). Sean Reardon (2011) has shown that differences in skills—such as test skills and reading attainment—by parents’ education and income have increased over the past forty years. Moreover, gaps are substantial in self-regulation and externalizing behavior by income and education dating back to the 1980s or earlier (Cunha and Heckman 2008). Given that richer and better-educated parents buy into better schools and that poorer parents often are forced to send their children to inferior schools, the rise in incomes and wealth at the top of the distribution has propelled the children of the highest income parents still higher, increasing the achievement gap between children at the 90th percentile of parental income and the middle children at the 50th percentile (Reardon 2013; Reardon and Owens 2014).

College attendance and graduation clearly matter for mobility and especially for those born poor (table 1). Not everyone needs a four-year degree to reach the middle class, but some sort of credential is increasingly needed in today’s labor market. Community colleges and CTE offer some hope of job advancement to noncollege goers, but the evidence of its success is limited at this time (Heinrich and Smeeding 2014b, 2014a). On the other hand, we know that most college-going and college-attainment gains have gone to upper-income classes. The gap in the fraction of children entering college and graduating college by income quartile has steadily expanded (Bailey and Dynarski 2011). Indeed, the children of the richest parents are increasingly likely to graduate within five years of starting college, most likely to attend and graduate from a high-quality college or university, receive family support while attending college, and graduate without college debt (Reardon, Baker, and Klasik 2012; Smeeding, Erikson, and Jäntti 2011). At the same time, evidence indicates that equally well-qualified lower-income children consistently choose lesser institutions than those for which they are qualified (Hoxby and Avery 2012). Reasons for not seizing the best opportunity are many and varied, including poor college counseling in urban high schools and inability to correctly gauge the actual cost of college-going.

These differences are also magnified by race. Postsecondary attendance among high school graduates at two-year and four-year postsecondary institutions is now 65 percent for blacks to 69 percent for whites (Casselman 2013). But college completion rates differ markedly: 62 percent of whites and only 40 percent of blacks receiving diplomas within six years of first attendance. Moreover, graduation rates among blacks differ substantially by gender, 48 percent of black women but only 35 percent of black men graduating.14 Antidiscrimination acts, civil rights legislation, and school desegregation led to improved educational conditions and outcomes for African Americans and other minorities beginning in the late 1960s. But low-income students of all colors and races have always lagged behind wealthy students. As a result, Reardon reports the gap today between white and black children is 40 percent smaller than it was in the 1970s, but only about half the size of that between rich and poor children (2011, 2013). Reardon, Rachel Baker, and Daniel Klasik (2012) also find that while 15 percent of high-income students from the 2004 graduating class of high school enrolled in a highly selective college or university, only 5 percent of middle-income graduates and 2 percent of low-income graduates did so.

Bhashkar Mazumder (2014) shows that education can make a difference for all races. According to his calculations, almost 90 percent of whites with a college degree escape the bottom quintile, compared with 75 percent of whites with a terminal high school degree. For blacks, rates of upward mobility rise sharply for those who attain more than a high school education. He shows that only 28 percent of blacks with a high school degree will move up from the bottom quintile, compared with 69 percent of blacks with fourteen years of schooling. For college graduates, the rate of upward mobility from the bottom quintile of parental income is just about the same for blacks and whites. The problem is that only about 15 percent of all blacks have attained a college degree in the NLSY data Mazumder analyzes.

ETHNICITY

We do not yet know enough about a number of other subpopulations to fully assess their progress or regress in IGM terms. For example, we know far less about the mobility of ethnic minorities, especially immigrants, because they are not part of older panel datasets. For instance, the PSID and various NLS and NLSY surveys help assess IGM, but are constrained by study and sample designs that begin with the original adult samples in the 1960s or 1970s and follow their children, hence excluding all immigrants arriving in the United States after the survey sample was drawn, except for those who have “married into” the dataset. We can still learn some things from these data, for instance, the NLSY79 oversampled Hispanics whose children are now reaching adulthood, but used small samples as they attained adulthood (Acs 2011).15 Further, cross-cohort studies of minorities, such as those Brian Duncan and Stephen Trejo mention (2015), are plagued by “ethnic sample attrition,” whereby children reclassify themselves as something other than Hispanic as they age. What we know about Latino IGM, then, is sparse and again includes only those who emigrated before 1980. Hence data are limited about economic mobility among Hispanic families, who tend to have lower incomes than non-Hispanic blacks and whites, but more stable family structures than blacks.16

The importance of ethnicity looms large in America’s future as the racial and ethnic makeup of today’s children is changing rapidly. In 2011, for the first time, fewer than half of the children born in America were to two Anglo American partners. Soon, all children will be “minority” children—the traditional racial and ethnic minorities, who will be in the majority by the numbers, and Anglo children, who will become the new minority. By 2050, Anglo Americans will make up less than 50 percent of the population. Hispanics, Asians, and multiracial populations are expected to double over the next forty years as the result of immigration, higher birth rates among minority populations already here, and more interracial marriages. These changes will challenge the nation’s legal, political, and economic systems, but are already beginning to affect the youngest of the emerging ethnic groups just now entering our school systems. Indeed, one should not forget that the children whose mobility we are trying to improve early on are unlikely to be white and Anglo-Saxon by heritage (Frey 2014). The combination of this explosion with the diminishing numbers of Anglo baby boomers will produce generational competition in future decades over resources and governmental priorities (see Brownstein and Taylor 2014; Brownstein 2015).

SUMMARY, CONCLUSION, AND POLICY IMPLICATIONS

This brief summary of vulnerable populations suggests many barriers to mobility, especially for black men and their children, those who grow up in unmarried-parent households, and the less educated. It also suggests that vulnerability comes in batches, and that low income, unstable family status, and especially lack of money inhibit upward IGM for the children of especially vulnerable groups. Changes in fertility and marriage, cohabitation and divorce, and education are also reinforcing differences in income inequality and further reducing economic mobility among disadvantaged children. The added effects of incarceration on black male mobility are largely unknown and underestimated.

Evidence is ample of diverging opportunities in the economic, sociological, social policy, demography, child well-being, and education literatures (Duncan and Murnane 2011; Ermisch, Jäntti, and Smeeding 2012; Smeeding, Garfinkel, and Mincy 2011). A widening gap in income, wealth, and consumption inequality is also likely to result in a decline in economic mobility (Corak 2013; Kenworthy 2012; Kenworthy and Smeeding 2014; Fisher et al. 2015). Parental earnings, adult skills, family structure, and neighborhood segregation all affect IGM. Higher returns to education encourage more investment in education, which affects opportunities, incentives, and degrees of mobility for rich versus poor children. However, not everyone has the capacity to make their own investments. Families with greater human capital, income, and wealth can invest more in their children and provide social connections to jobs and the labor market. Parents with higher incomes tend to provide supports and safety nets for their children. Less-educated, low-income, low-wealth, and unmarried parents do not enjoy these advantages and must rely on the public sector to provide education and health care for their children. Hence a set of social and economic factors can both boost opportunities for some and make upward mobility difficult for other, more vulnerable groups.

Policy

The two most important preventive measures that will increase family stability and child quality, as well as increase IGM, are, first, to improve the economic and social prospects of the bottom half in terms of job stability, income, and wage growth; and, second, to provide the means to reduce unplanned pregnancies and births. America’s policy efforts to date have not increased much-needed skills among young men who do not have them. Without improved efforts in building human capital, it may take the better part of a decade to reach a point where demand for workers helps raise wages and increase job quality among younger low-skill workers, especially men (Heinrich and Smeeding 2014a). The solution for the hardest to employ should involve a stronger EITC (including one for single adults), larger refundable child tax credits, and a higher minimum wage (Sawhill and Karpilow 2014) so that low-skill parents who work have higher in-comes. Although such a package would continue to help mitigate poverty, the labor market solution has to involve more than targeted programs alone for the poor if we are to provide greater chances for lower-middle-class children to succeed.

Changes in incarceration policy are in their infancy. For a long time, researchers have known about the effects of prison on earnings outcomes (Pager 2003), and more recently on the effects of imprisonment of parents on their children in terms of health (Wilbur et al. 2007; Lee, Fang, and Luo 2013) and education (Hagan and Foster 2012). Although we can begin to change sentencing guidelines and penalties for first-time offenders to reduce the effects of criminal behavior on the next generation, the best studies of the “de-carceration” initiative suggest that the dismantling of the prison state will take some time, and much damage has already been done to those currently imprisoned. Policies to reduce effects of imprisonment on the incarcerated and on their children, including more visitation while in prison and added employment and family reunification support after release, can help (Carter and McCarthy 2015). Reduction in legal exclusions for ex-inmates will also help them reintegrate into the community and workplace (Waters and Kasinitz 2015). However, most prisoners come from low-income backgrounds to begin with, suggesting that although changes in incarceration policy are important, they are not a panacea for social and economic mobility issues for disadvantaged adults and their children in and of themselves (Dolan and Carr 2015).

Despite this article’s gloomy reports, we are making some limited progress in improving child mobility and life chances for the next generation. For example, United States fertility is at an all-time low, reaching a rate of 1.86 children per woman of childbearing age in 2013. More important, the way that American fertility has reached its record low is by falling birth-rates among teens and women in their early twenties. This is indeed good news for improving the upward mobility of children, keeping young women who are having children too early out of poverty, and bringing the U.S. teen pregnancy rate closer to rates in other rich countries (Hamilton et al. 2014). Much of this success has come because of the spread of effective long-acting reverse contraceptives, which are much more effective than conventional birth control in preventing unplanned pregnancies (Sawhill 2014).

But prevention is only half of the policy package. We must at the same time do everything we can to improve the chances of today’s disadvantaged children. Labor market and child outcomes suggest that soft skills such as conflict resolution and how to respond to setbacks should be emphasized more in preschools and in parenting classes (Heckman and Mosso 2014). And because parents are so important for child outcomes, we should try to make better parents, too. Although in the new policy realm of parental improvement, ideas and efforts so far outstrip evidence of success, with a few exceptions (King, Coffey, and Smith 2013), some parenting interventions, effective preschool programs, and successful K–12 programs have been shown to greatly improve mobility if each program is implemented and has the same success it had in experimental evaluations. The effect of a set of these programs simulated by the Social Genome team has been shown to reduce income gaps in the life course stages from 6 to 24 percentage points and racial gaps by a significant amount, 6 to 13 percentage points, depending on life stage. If all three treatments were applied successfully and continuously, the fraction of all children who start and remain in the bottom income quintile would be reduced by 11 percentage points, from 34 to 23 percent (Sawhill and Venator 2014).

We must be modest in our expectations because we will never achieve full equality of opportunity or mobility. The role of parents is important no matter where on the family SES spectrum a family lies (Duncan and Murnane 2011; Ermisch, Jäntii, and Smeeding 2012; Smeeding 2016). It is very difficult for society to directly interfere with parental access to resources and opportunities—in effect to limit what rich parents can do for their children. For example, promoting integrated schools with low-SES and high-SES children being instructed together might lead the rich to set up their own system of private and exclusive schools, as in the United Kingdom and to a lesser extent in the United States, thus perpetuating inequality of life chances (Blanden et al. 2014; Ermisch, Jäntti, and Smeeding 2012).

Taken altogether, these trends suggest that increasing social and economic inequality has a large tangible cost—that of diverging destinies for children as witnessed by trends toward less-equal life chances and lower social mobility for vulnerable children. Further, no single policy will by itself correct this inequity. Although evidence-based policy can make a difference and can ostensibly increase upward mobility for the truly disadvantaged, as Isabel Sawhill and Joanne Venator (2014) suggest, unless we add these proven and cost-effective programs to our policy arsenal and maintain them for a considerable period, opportunity and mobility will not increase for the most disadvantaged. In a society that falsely prides itself on equality of opportunity, this is indeed discouraging news.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the Boston Federal Reserve Bank for its support in completing this paper, and the Russell Sage Foundation for support for parts of it. Emily Cuddy and Jonathan Fisher helped with data preparation; Deborah Johnson, David Chancellor, and Dawn Duren provided additional editorial help. Angela Glover Blackwell, Joseph R. Fishkin, Katharine Bradbury, Robert Triest, two referees, and the participants at the Boston Federal Reserve Bank Conference on Inequality of Economic Opportunity held October 17–18, 2014, are thanked for comments on an earlier draft and presentation. All errors of commission and omission are the responsibility of the author alone.

Footnotes

William Galston (2014) documents at least five recent (mid-2014) surveys that show the same result.

For more on SGM, see the Social Genome Project (http://www.social-genome.org/), the Brookings guide to the model (http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/Centers/ccf/sgm_guide.pdf), and Reeves and Sawhill 2015.

The ranges depend on the exact specifications, but combining NLSY and Panel Study of Income Dynamics results, the range delineates the stickiness in the tails (see Reeves and Sawhill 2015; Jäntti et al. 2006).

The CNLSY is used in the Social Genome Model to estimate patterns of mobility for children as they move through the life course. The CNLSY sample currently ranges in age from under five to over thirty-five and these parameters are closer to the current generation than are those in the NLSY. The oldest of the CNLSY’s economic mobility sample can be traditionally measured in about five to ten years, when their incomes and earnings are best observed (Auten, Gee, and Turner 2013). The data in table 1 refer to the NLSY parents and their experiences growing up because it is summarizing adult outcomes of the IGM process.

Thanks to Emily Cuddy at Brookings who provided the Social Genome matrices underlying table 1. The parameters are taken from the 1979 NLSY panel and thus are based on the experiences of this particular cohort.

In fact, in terms of current policy interest in absolute mobility, the living standards of the bottom 40 percent are precisely the key foci for those who want “growth with equity” (Cingano 2014), “shared prosperity” (Jolliffe and Lanjouw 2014), and “inclusive prosperity” (Summers and Balls 2015).

For instance, recent work shows that since 2001, with wealth measured in early 2013, wealth inequality has increased and income inequality with it (Yellen 2014; Pfeffer, Danziger, and Schoeni 2014; Bricker et al. 2014). And financial wealth has increased by 20 percent since the time of both surveys. Indeed, Fabian Pfeffer (2011) argues that wealth is more important than income for IGM.

Table 1 looks at single mothers but figure 3 includes single fathers (who make up about 10 percent of all single parents).

Gregory Acs also finds that black men raised in middle-class families are 17 percentage points more likely to be downwardly mobile than white men raised in the middle class are: 38 percent of black men fall out, compared with 21 percent of white men (2011).

The AFQT is a measure of aptitude used mainly by the armed forces and by researchers who want to measure aptitudes in young adults. Scores are computed using the standard scores from four subtests: arithmetic reasoning, mathematics knowledge, paragraph comprehension, and word knowledge.

Indeed, findings are that the median age of first birth for women who are college graduates is twenty-nine (Smeeding, Garfinkel, and Mincy 2011).

These include high school dropouts but also high school graduates as the literature on educational mobility tends to favor the latter. Table 1 suggests that those with high school only do better than those who dropped out, but much worse than those who graduate college.

The amounts spent on developmental goods and services by top and bottom quintile parents in 2006 were $8,872 and $1,315, respectively.

Ben Casselman (2013) and the Journal of Blacks in Higher Education (2014) also establish that blacks are more likely than whites to attend two-year institutions, to go part time and not full time, and to need remedial classes.

For instance, the one study we know of that uses the NLSY 1979 cohort for this purpose (Acs 2011) focuses on downward mobility from the middle class for youth who were age fourteen to seventeen in 1979 and who lived in their parents’ homes in 1979 and 1980. Their adult economic status was then assessed in 2004 and 2006, when they were between thirty-nine and forty-four. The Acs study covers white, black, and the NLSY sample of Hispanic youth from middle-class families (parents’ incomes in 1979 between 30th and 70th percentiles) who appear in the NLSY as adults in the 2004 to 2006 period. The Hispanic sample in adulthood then is only 201, despite the fact that originally 1,783 Hispanics-Latinos (encompassing at least seven national origins) were interviewed in 1979. Differences in follow-up are due to sample attrition as well as the study age and income selections. Acs found about 20 to 29 percent of Hispanics were, using three measures of downward mobility, in a worse economic position than their parents. In each case, the mobility was less than that of blacks but more than that of whites when they became adults.

One more promising approach is for future studies to begin with the current population and trace back to find their parental heritage instead of the other way around (Grusky, Smeeding, and Snipp 2015). In fact, Duncan and Trejo (2015) mention that the 1997 NLSY has in its tenth round begun to collect grandparent’s country of origin to attempt to measure immigrant assimilation and mobility, hence starting with a more recent cohort and moving back to trace parental and grandparental origin.

REFERENCES

- Acs Gregory. 2011. “Downward Mobility from the Middle Class: Waking Up from the American Dream.” Economic Mobility Project report, September. Washington, D.C.: Pew Charitable Trusts. [Google Scholar]

- Aizer Anna, and Currie Janet. 2014. “The Intergenerational Transmission of Inequality: Maternal Disadvantage and Health at Birth.” Science 344(6186): 856–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almond Douglas, Hoynes Hilary W., and Schanzenbach Diane W.. 2011. “Inside the War on Poverty: The Impact of Food Stamps on Birth Outcomes.” Review of Economics and Statistics 93(2): 387–403. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson Gunnar. 2002. “Children’s Experience of Family Disruption and Family Formation: Evidence from 16 FFS Countries.” Demographic Research 7(7): 343–64. [Google Scholar]

- Auten Gerald, Gee Geoffrey, and Turner Nicholas. 2013. “Income Inequality, Mobility and Turnover at the Top in the U.S., 1987–2009.” American Economic Review 103(3): 168–72. [Google Scholar]

- Autor David H. 2014. “Skills, Education, and the Rise of Earnings Inequality among the other 99 Percent.” Science 344(6186): 843–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey Martha J., and Dynarski Susan M.. 2011. “Gains and Gaps: A Historical Perspective on Inequality in College Entry and Completion.” In Whither Opportunity?: Rising Inequality, Schools, and Children’s Life Chances, edited by Duncan Greg and Murnane Richard. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee Sudipto. 2015. Intra-Family Cash Transfers in Older American Households. Issue Brief #415 Washington, D.C.: Employee Benefit Research Institute; Accessed April 7, 2016 http://www.ebri.org/pdf/EBRI_IB_415.June15.Transfers.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker Gary S., and Tomes Nigel. 1986. “Human Capital and the Rise and Fall of Families.” Journal of Labor Economics 4(July): S1–S39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingley Paul, Corak Miles, and Westergaard-Nielsen Neils. 2012. “Equality of Opportunity and Intergenerational Transmission of Employers.” In From Parents to Children: The Intergenerational Transmission of Advantage, edited by Ermisch John, Jäntti Markus, and Smeeding Timothy. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Blanden Jo, Haveman Robert, Smeeding Timothy, and Wilson Kathryn. 2014. “Intergenerational Mobility in the United States and Great Britain: A Comparative Study of Parent-Child Pathways.” Review of Income and Wealth 60(3): 425–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bricker Jesse, Dettling Lisa J., Henriques Alice, Hsu Joanne W., Moore Kevin B., Sabelhaus John, Thompson Jeffrey, and Windle Richard A.. 2014. “Changes in U.S. Family Finances from 2010 to 2013: Evidence from the Survey of Consumer Finances.” Federal Reserve Bulletin 100(4)(September): 1–40. Accessed December 5, 2015 http://www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/bulletin/2014/pdf/scf14.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Brownstein Ronald. 2015 “The States that Will Pick the President: The Sunbelt.” National Journal, February 4, 2015. Accessed December 5, 2015 http://www.nationaljournal.com/next-america/newsdesk/the-states-that-will-pick-the-president-the-sunbelt-20150204.

- Brownstein Ronald, and Taylor Paul. 2014. The Next America: Boomers, Millennials, and the Looming Generational Showdown. Philadelphia, Pa.: Perseus Books. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson Marcia J., and Furstenberg Frank F.. 2006. “The Prevalence and Correlates of Multipartnered Fertility among Urban U.S. Parents.” Journal of Marriage and Family 68(3): 718–32. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson Marcia J., Furstenberg Frank F., McLahanan Sara S., and VanOrman Alicia G.. 2013. “Multi-Partnered Fertility and Child Well-Being Among Urban U.S. Families.” Paper presented at the annual meetings of the Association for Public Policy Analysis and Management, Washington, D.C. (November 8, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- Carter Angela, and McCarthy Bill. 2015. “Reducing the Effects of Incarceration on Children and Families.” Policy Brief 3, no. 10 Davis, Calif.: Center for Poverty Research. [Google Scholar]

- Casselman Ben. 2013 “Race Gap Narrows in College Enrollment, But Not in Graduation.” FiveThirtyEight Economics Blog. Last modified April 30, 2014. Accessed December 5, 2015 http://fivethirtyeight.com/features/race-gap-narrows-in-college-enrollment-but-not-in-graduation/.

- Cherlin Andrew J. 2014. Labor’s Love Lost: The Rise and Fall of the Working-Class Family in America. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Cingano Federico. 2014. “Trends in Income Inequality and Its Impact on Economic Growth.” Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers no. 163. Paris: OECD Publishing; Accessed December 5, 2015 http://www.oecd.org/els/soc/trends-in-income-inequality-and-its-impact-on-economic-growth-SEM-WP163.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Congressional Budget Office. 2013. “Trends in the Distribution of Household Income Between 1979 and 2010.” Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; Accessed December 5, 2015 http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/113th-congress-2013-2014/reports/44604-AverageTaxRates.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper Kerris, and Stewart Kitty. 2013 “Does Money Affect Children’s Outcomes? A Systematic Review.” October 2013. Yokr, UK: Joseph Rowntree Foundation; Accessed December 5, 2015 http://sticerd.lse.ac.uk/dps/case/cr/casereport80.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Corak Miles. 2013. “Income Inequality, Equality of Opportunity, and Intergenerational Mobility.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 27(3): 79–102. [Google Scholar]

- Corak Miles, and Piraino Patrizio. 2011. “The Intergenerational Transmission of Employers.” Journal of Labor Economics 29(1): 37–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha Flavio, and Heckman James J.. 2008. “Formulating, Identifying and Estimating the Technology of Cognitive and Noncognitive Skill Formation.” Journal of Human Resources 43(4): 738–82. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl Gregory B., and Lochner Lance. 2012. “The Impact of Family Income on Child Achievement: Evidence from the Earned Income Tax Credit.” American Economic Review 102(5): 1927–56. [Google Scholar]

- Dolan Karen, and Carr Jodi L.. 2015. “The Poor Get Prison: The Alarming Spread of the Criminalization of Poverty.” Washington, D.C.: Institute for Policy Studies; Accessed December 5, 2015 http://www.ips-dc.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/IPS-The-Poor-Get-Prison-Final.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Dumas Christelle, and Lefranc Arnaud. 2012. “Early Schooling and Later Outcomes.” In From Parents to Children: The Intergenerational Transmission of Advantage, edited by Ermisch John, Jäntti Markus, and Smeeding Timothy. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan Greg J., Magnuson Katherine, and Votruba-Drzal Elizabeth. 2014. “Boosting Family Income to Promote Child Development.” Future of Children 24(1): 99–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan Greg J., Morris Pamela, and Rodrigues Chris. 2011. “Does Money Really Matter? Estimating Impacts of Family Income on Young Children’s Achievement with Data from Random-Assignment Experiments.” Developmental Psychology 47(5): 1263–79. doi: 10.1037/a0023875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan Greg J., and Murnane Richard, eds. 2011. Whither Opportunity: Rising Inequality, School, and Children’s Life Chances. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan Brian, and Trejo Stephen J.. 2015. “Assessing the Socioeconomic Mobility and Integration of U.S. Immigrants and Their Descendants.” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 657 (January): 108–35. [Google Scholar]

- Edin Kathryn, DeLuca Stefanie, and Owens Ann. 2012. “Constrained Compliance: Solving the Mystery of MTO Lease-Up Rates and Why Mobility Matters.” Cityscape 14(2): 181–94. [Google Scholar]

- Ermisch John, Jäntti Markus, and Smeeding Timothy, eds. 2012. From Parents to Children: The Intergenerational Transmission of Advantage. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Evans William N., and Garthwaite Craig L.. 2014. “Giving Mom a Break: The Impact of Higher EITC Payments on Maternal Health.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 6(2): 258–90. [Google Scholar]