Abstract

Incarceration is strongly associated with post-release STI/HIV risk. One pathway linking incarceration and STI/HIV risk may be incarceration-related dissolution of protective network ties. Among African American men released from prison who were in committed partnerships with women at the time of incarceration (N = 207), we measured the association between committed partnership dissolution during incarceration and STI/HIV risk in the 4 weeks after release. Over one-quarter (28%) experienced incarceration-related partnership dissolution. In adjusted analyses, incarceration-related partnership dissolution was strongly associated with post-release binge drinking (adjusted odds ratio (AOR) 4.2, 95% confidence interval (CI); 1.4–15.5). Those who experienced incarceration-related partnership dissolution were much more likely to engage in multiple/concurrent partnerships or sex trade defined as buying or selling sex (64%) than those who returned to the partner (12%; AOR 20.1, 95% CI 3.4–175.6). Policies that promote maintenance of relationships during incarceration may be important for protecting health.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11524-018-0274-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Incarceration, STI, HIV, African American, Partnerships

Introduction

Incarceration is considered a social determinant of STI/HIV in the US [1] given its consistent association with post-release sexual risk behavior and STI/HIV [2–8]. One pathway that may link incarceration and STI/HIV risk is incarceration-related disruption of protective network ties. Incarceration disrupts substantial proportions of committed partnerships [9, 10]. If an inmate loses a partner during incarceration, he may seek new partners upon release. Partnership dissolution may impact mental health [11], leading to self-medication with substance use [12]; both mental disorders and substance use are established risk factors for sexual risk-taking and infection [13–15].

The purpose of this study was to describe the association between dissolution of committed partnerships during incarceration and former inmates’ post-release STI/HIV-related sex risk-taking. We describe 1-month follow-up findings of Project DISRUPT, a study conducted among African American men incarcerated in North Carolina who were in heterosexual committed partnerships at prison entry and who were followed during community re-entry. We measure 1-month post-release outcomes given this is a period of instability and drug risk-taking [16, 17]; substantial proportions initiate sexual activity within weeks of release [18] and evidence suggests risky behaviors during this time period are common [19]. We recruited incarcerated men, because men experience a disproportionate burden of incarceration [20] and understanding STI/HIV determinants among men has relevance to risk among women given of the majority of women are infected as a result of sex with a male partner [21]. The study focused on heterosexual partnerships given strong extant evidence suggesting incarceration influences sexual risk behavior and STI/HIV among former male inmates and their female partners [2–8]. The aim of this study was to measure associations between incarceration-related committed partnership dissolution and STI/HIV-related sex risk [9, 10], as well as mental health and substance use factors given the association of these factors with STI/HIV risk [13–15].

Methods

Study Setting and Population

As previously described [22], Project DISRUPT recruited participants from minimum and medium security facilities in the North Carolina Department of Public Safety (NCDPS) from September 2011 to January 2014. Participants were African American men at least 18 years of age scheduled to be released within 2 months; incarcerated less than 36 months; HIV-negative at prison entry based on testing at prison intake; not held in segregation; not currently incarcerated for rape, murder, or kidnapping; in a committed partnership with a woman at prison entry (i.e., “a woman in your life who you were having sex with regularly and who you felt committed to”); residing in the community for at least 6 months before the current incarceration; able to read and write in English; and willing to provide informed consent and post-release contact information. Of 477 eligible individuals, 207 enrolled. The Institutional Review Boards of NCDPS, New York University School of Medicine, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and the University of Florida approved all study activities.

Data Collection

At the baseline (in-prison) and follow-up study visit, trained research assistants (RAs) administered a survey that measured sociodemographics, mental health, substance use, sexual risk behavior, partner characteristics, and relationship characteristics. The 1-month follow-up visit window was 2–14 weeks after release; the median number of days after release that 1-month visits occurred was 43 days. Participants completing the visit in the window were asked to report on experiences and behaviors in the past 4 weeks. Among 14 participants who participated in a follow-up visit outside the study visit window, we administered a “one month catch-up” module and asked participants to report on behaviors and experiences in the 4 weeks after release from incarceration.

Post-release interviews were conducted by RAs either in-person in a private setting in the participant’s community (73%) or via telephone when not feasible such as when the participant had moved outside of central NC (27%). Most of the survey components in face-to-face interviews used audio computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI) software to reduce social desirability bias. Remuneration for study participation was not provided during incarceration, per NCDPS policies. After release, participants received $50 for completion of each follow-up interview.

Measures

Exposure

Committed partnership dissolution was based on report of the relationship status at baseline. However, to prevent exposure misclassification, additional information from follow-up was used to code exposure status among 29% of participants who were unaware of the relationship status during the incarceration (i.e., the partner may have ended the relationship yet the participant was not yet aware of this until after release).

Outcomes

Mental disorder symptoms, substance use, sexual risk-taking in the 4 weeks after release.

Mental Disorder Symptoms

Depressive symptoms were measured using a five-item version of the Centers for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) scale, with scores ≥ 4 indicating symptoms indicative of major depressive disorder, the cut-point proportional to that for complete 20-item CES-D [13, 14, 22, 23]. Participants rated stress assessing domains including overall stress and stress about housing, food security, health, employment, and violence on a one to 10 scale [24]; responses to each of six topics were summed to create a score and dichotomized at the 75th percentile given the strong associations with psychopathology using this cut-point [14].

Substance Use

Binge drinking was defined as consuming ≥ 5 standard drinks on a typical day. We analyzed use of marijuana, the most commonly used drug, and crack/cocaine given the high prevalence and consistent correlations with sexual risk behaviors at baseline [22]. Use of these drugs was assessed using a modified version of the National Institute on Drug Abuse Risk Behavior Assessment (RBA) Tool [25].

Sexual Risk-Taking

We examined a combined indicator of multiple/concurrent sex partners or sex trade (concurrent partnerships, non-concurrent multiple partnerships, or buying or selling sex). Inconsistent condom use with new/casual partners was defined as failure to use a condom 100% of the time when having sex with these partners. Participants who reported having sex while drunk and/or high were considered to have had sex while intoxicated. Participants who reported sex with partners who “definitely” or “probably” had other sexual partners currently, had ever engaged in sex work, or had ever been diagnosed with an STI were coded as having sex with a partner at elevated risk of infection.

Potential Confounders

Antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) was measured using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV module [13, 26] and executive function (EF) with the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test [27] in which a raw perseverative error score at the highest quartile (score ≥ 14) was considered indicative of impaired executive function; history of perpetration of intimate partner violence by report of whether the participant and/or his partner used physical violence and/or a weapon against the other in the 6 months before the incarceration; and relationship happiness at baseline by report of being “very happy,” “extremely happy,” or “perfect” in the relationship. We considered the baseline measure of each outcome as a potential confounder. Because age, socioeconomic factors (education, employment), length of incarceration, and the number of children/dependents were not associated with partnership loss and/or the outcomes, these factors were not assessed as confounders to optimize statistical power.

Baseline Characteristics to Evaluate Differences by Follow-up Participation

We compared potential confounders and background factors including baseline age, education, employment, most serious offense for the current incarceration, marital status, and biologically confirmed STI based on urine nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) for detection of Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae (Aptima Combo 2, Hologic|Gen-Probe, Inc.), and Trichomonas vaginalis (Aptima T. vaginalis analyte-specific reagents, Hologic|Gen-Probe, Inc.) by follow-up participation status and relationship dissolution status.

Analyses

We compared characteristics by participation status and relationship dissolution status using t tests and chi-squared tests. We estimated unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for associations between committed partnership dissolution and adverse outcomes. We used backwards elimination to identify the set of confounding variables necessary to include in each final model to optimize validity and parsimony [28] ensuring the OR derived from each final model was no greater than 10% different than the OR derived from the fully-adjusted model which included all potential confounders. All analyses were conducted using SAS v9.4 (Cary, NC).

Results

Participant Baseline Characteristics

Approximately 55% were lost to follow-up (LTF). Those who completed follow-up were comparable to those LTF on most factors (Table 1). However, participation was associated with higher levels of lifetime crack/cocaine use, and though not significant at the 0.05 level, higher risk of buying and/or selling sex, ASPD, and violence in relationships, suggesting participators represented a group at elevated STI/HIV risk versus those LTF.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics among participants who participated in follow-up versus did not participate in follow-up (n = 207)

| Characteristic | Participated in follow-up (n = 94)* n(%)/mean ± std | Did not participate in follow-up (n = 113)* n(%)/mean ± std | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 36.9 ± 9.6 | 32.4 ± 9.0 | < 0.001 |

| Education status | 0.84 | ||

| Completed high school | 58 (67.4) | 70 (66.0) | |

| Did not complete high school | 28 (32.6) | 36 (34.0) | |

| Employment status† | 0.99 | ||

| Employed full/part-time | 49 (61.3) | 62 (61.4) | |

| Not employed | 31 (38.8) | 39 (38.6) | |

| Current incarceration for a violent crime | 0.99 | ||

| Yes | 25 (26.6) | 30 (26.6) | |

| No | 69 (73.4) | 83 (73.4) | |

| Married to committed partner | 0.11 | ||

| Yes | 20 (23.8) | 15 (14.6) | |

| No | 64 (76.2) | 88 (85.4) | |

| Degree of relationship happiness† | 0.82 | ||

| Happy | 29 (34.9) | 34 (33.3) | |

| Unhappy | 54 (65.1) | 68 (66.7) | |

| Participant perpetrated IPV† | 0.07 | ||

| Yes | 36 (45.0) | 32 (31.7) | |

| No | 44 (55.0) | 69 (68.3) | |

| Committed partner perpetrated IPV† | 0.46 | ||

| Yes | 45 (55.6) | 50 (50.0) | |

| No | 36 (44.4) | 50 (50.0) | |

| Depressive symptoms† | 0.64 | ||

| Yes | 32 (34.0) | 42 (37.2) | |

| No | 62 (66.0) | 71 (62.8) | |

| Elevated stress† | 0.29 | ||

| Yes | 21 (25.0) | 33 (32.0) | |

| No | 63 (75.0) | 70 (68.0) | |

| Antisocial personality disorder | 0.07 | ||

| Yes | 17 (20.0) | 11 (10.7) | |

| No | 68 (80.0) | 92 (89.3) | |

| Impaired executive function | 0.70 | ||

| Yes | 22 (26.2) | 29 (28.7) | |

| No | 62 (73.8) | 72 (71.3) | |

| Binge drinking on typical day† | 0.49 | ||

| Yes | 19 (24.4) | 19 (20.0) | |

| No | 59 (75.6) | 76 (80.0) | |

| Lifetime frequent marijuana use | 0.03 | ||

| Yes | 50 (60.2) | 76 (75.3) | |

| No | 33 (39.8) | 25 (24.8) | |

| Lifetime crack/cocaine use | 0.03 | ||

| Yes | 40 (48.2) | 33 (32.4) | |

| No | 43 (51.8) | 69 (67.6) | |

| Multiple/concurrent partnerships† | 0.49 | ||

| Yes | 41 (50.6) | 45 (45.5) | |

| No | 40 (49.4) | 54 (54.5) | |

| Sex trade involvement† | 0.15 | ||

| Yes | 12 (14.5) | 8 (7.8) | |

| No | 71 (85.5) | 94 (92.2) | |

| Inconsistent condom use with new/casual partners† | 0.53 | ||

| Yes | 37 (46.3) | 49 (51.0) | |

| No | 43 (53.8) | 47 (49.0) | |

| Sex while intoxicated† | 0.92 | ||

| Yes | 67 (82.7) | 83 (82.2) | |

| No | 14 (17.3) | 18 (17.8) | |

| Sex with high-risk partners† | 0.80 | ||

| Yes | 21 (26.6) | 28 (28.3) | |

| No | 58 (73.4) | 71 (71.7) | |

| Biologically -confirmed STI | 0.51 | ||

| Yes | 9 (10.7) | 8 (7.9) | |

| No | 75 (89.3) | 93 (92.1) | |

| Partnership status | 0.73 | ||

| Together | 60 (71.4) | 75 (72.8) | |

| Not together | 15 (18.9) | 19 (18.5) | |

| Do not know | 8 (9.5) | 9 (8.7) |

*Individual indicator percentages may not sum to totals due to missing value

†In the 6 months before participant’s incarceration

Associations between Partnership Dissolution during Incarceration and Baseline Characteristics

Among those who participated in the follow-up, 28% (n = 26) were categorized as having experienced incarceration-related committed partnership dissolution. Relationship dissolution status was not associated with most characteristics measured on the baseline interview (Table 2). However, those who experienced relationship dissolution during incarceration were more likely to report experience of depressive symptoms, frequent marijuana use, and sexual risk behaviors in the 6 months before incarceration versus those who remained with partners during incarceration.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics by incarceration-related partnership dissolution status (N = 94)

| Characteristic | Still with committed partner (N = 67) n(%)/mean ± std |

No longer with committed partner (N = 26) n(%)/mean ± std |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 37.3 ± 9.4 | 36.2 ± 10.5 | 0.62 |

| Education status | 0.91 | ||

| Completed high school | 40 (66.7) | 17 (68.0) | |

| Did not complete high school | 20 (33.3) | 8 (32.0) | |

| Employment status† | 0.96 | ||

| Employed full/part-time | 35 (61.4) | 14 (60.9) | |

| Not employed | 22 (38.6) | 9 (39.1) | |

| Current incarceration for a violent crime | 0.08 | ||

| Yes | 14 (20.9) | 10 (38.5) | |

| No | 53 (79.1) | 16 (61.5) | |

| Married to committed partner | 0.15 | ||

| Yes | 17 (27.9) | 3 (13.0) | |

| No | 44 (72.1) | 20 (87.0) | |

| Degree of relationship happiness† | 0.38 | ||

| Happy | 38 (62.3) | 16 (72.7) | |

| Unhappy | 23 (37.7) | 6 (27.3) | |

| Participant perpetrated IPV† | 0.75 | ||

| Yes | 25 (43.9) | 11 (47.8) | |

| No | 32 (56.1) | 12 (52.2) | |

| Committed partner perpetrated IPV† | 0.04 | ||

| Yes | 28 (48.3) | 17 (73.9) | |

| No | 30 (51.7) | 6 (26.1) | |

| Depressive symptoms† | 0.05 | ||

| Yes | 19 (28.4) | 13 (50.0) | |

| No | 48 (71.6) | 13 (50.0) | |

| Elevated stress† | 0.20 | ||

| Yes | 13 (21.3) | 8 (34.8) | |

| No | 48 (78.7) | 15 (65.2) | |

| Antisocial personality disorder | 0.14 | ||

| Yes | 10 (16.1) | 7 (30.4) | |

| No | 52 (83.9) | 16 (23.5) | |

| Impaired executive function | 0.10 | ||

| Yes | 13 (21.3) | 9 (39.1) | |

| No | 48 (78.7) | 14 (60.9) | |

| Binge drinking on typical day† | 0.49 | ||

| Yes | 9 (16.4) | 10 (43.5) | |

| No | 46 (83.6) | 13 (56.5) | |

| Lifetime frequent marijuana use | 0.04 | ||

| Yes | 32 (53.3) | 18 (78.3) | |

| No | 28 (46.7) | 5 (21.7) | |

| Lifetime crack/cocaine use | 0.15 | ||

| Yes | 26 (43.3) | 14 (60.9) | |

| No | 34 (56.7) | 9 (39.1) | |

| Multiple/concurrent partnerships† | 0.002 | ||

| Yes | 23 (39.7) | 18 (78.3) | |

| No | 35 (60.3) | 5 (21.7) | |

| Sex trade involvement† | 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 4 (6.7) | 8 (34.8) | |

| No | 56 (93.3) | 15 (65.2) | |

| Inconsistent condom use with new/casual partners† | 0.24 | ||

| Yes | 24 (42.1) | 13 (56.5) | |

| No | 33 (57.9) | 10 (43.5) | |

| Sex while intoxicated† | 0.01 | ||

| Yes | 44 (75.9) | 23 (100.0) | |

| No | 14 (24.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Sex with high-risk partners† | 0.02 | ||

| Yes | 11 (19.3) | 10 (45.4) | |

| No | 46 (80.7) | 12 (54.6) | |

| Biologically -confirmed STI | 0.22 | ||

| Yes | 5 (8.2) | 4 (17.4) | |

| No | 56 (91.8) | 19 (82.6) |

*Individual indicator percentages may not sum to totals due to missing values

†In the 6 months before participant’s incarceration

Relationship dissolution status was not significantly different among those who completed the survey with ACASI (28%) versus a phone interview (23%;’ p = 0.61).

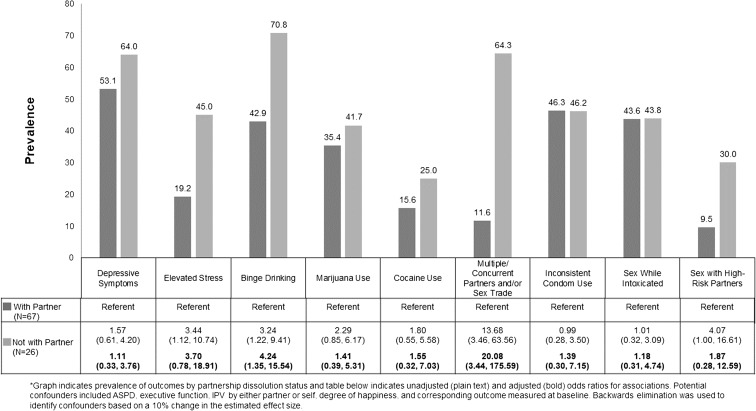

Associations between Partnership Dissolution during Incarceration and Mental Health, Substance Use, and Sexual Risk-Taking in the 4 Weeks after Release

Incarceration-related partnership dissolution was not associated with post-release depressive symptoms (Fig. 1) but was strongly associated with stress (OR = 3.44, 95% CI 1.12, 10.74). In adjusted models, the strength of the association appeared to remain, though it became less precise and was not significant at the 0.05 level (adjusted OR = 3.70, 95% CI 0.78, 18.91) (see Supplemental Table for confounders retained in backwards elimination model-building procedure). In both unadjusted and adjusted analyses, incarceration-related partnership dissolution was associated with binge drinking (AOR = 4.24, 95% CI 1.35, 15.54) but was not statistically significantly associated with drug use. Participants who experienced incarceration-related partnership dissolution were much more likely to report having multiple/concurrent sex partners or sex trade (64%) than those who returned to a partner (12%; OR = 13.68, 95% CI 3.46, 63.56). The association remained in multivariable models though adjustment greatly reduced precision (AOR = 20.1, 95% CI 3.44, 175.6). Those who lost a partner during incarceration were more likely than those returning to a partner to have sex with someone at elevated infection risk after release (OR = 4.07, 95% CI 1.00, 16.61) but the association was attenuated in adjusted models and became less precise. Loss of a committed partner was not associated with inconsistent condom use with new/casual partners or sex while intoxicated.

Fig. 1.

Associations between dissolution of committed partnerships during incarceration and mental health, substance use, and sexual risk-taking in the 4 weeks after release*

Discussion

In this small cohort, we observed that African American men who experienced incarceration-related partnership dissolution faced disproportionate stress, binge drinking, sexual risk behavior, and exposure to high-risk sex partners in the weeks after release compared with those returning to partners. Over 60% who experienced partnership dissolution reported multiple/concurrent partnerships or sex trade upon release versus approximately 10% of those whose partnerships remained intact, and this strong association persisted in multivariable analyses that considered a broad range of confounders measured at baseline including mood and personality factors, executive function, relationship characteristics, and baseline drug and sexual risk factors. The most important study limitation is the modest cohort size which was further diminished by considerable attrition. Though participators were comparable to those lost to follow-up on most characteristics, analyses suggest those who participated may represent a somewhat higher-risk group. There is no extant literature to inform understanding of the impact of losing a partner during incarceration in higher- versus lower-risk populations hence we cannot make inferences about the direction of the potential bias. Additional important limitations include the potential for social desirability bias which may have been differential by relationship status though underreporting was mitigated by ACASI use across groups and by the potential for residual confounding despite attempts to carefully measure and control for a range of confounders.

Despite study limitations, the results provide preliminary evidence to suggest dissolution of partnerships during incarceration/release plays a role in the established association between incarceration and post-release STI/HIV risk.[2–8]. The results highlight the need for further research on incarceration-related partnership dissolution and STI/HIV risk in larger samples and different types of couples and for testing of couple-level STI/HIV prevention interventions that foster relationship skills while reducing relationship violence [29–32]. The findings also indicate criminal justice policies that maintain current levels of visitation and reduce barriers to communication during incarceration, important for inmates’ well-being, may protect against post-release STI/HIV risk.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 24 kb)

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by NIDA R01DA028766 (Principal Investigator: Khan) and the University of North Carolina Center for AIDS Research (AI050410). Dr Golin’s salary was partially supported by K24 HD06920. Laboratory testing for sexually transmitted infections was supported, in part, by Southeastern Sexually Transmitted Infections Cooperative Research Center Grant U19-AI031496 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

References

- 1.Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ. Social context, sexual networks, and racial disparities in rates of sexually transmitted infections. J Infect Dis. 2005;191(Suppl 1):S115–S122. doi: 10.1086/425280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hammett TM. HIV/AIDS and other infectious diseases among correctional inmates: transmission, burden, and an appropriate response. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(6):974–978. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khan MR, Berger A, Hemberg J, O'Neill A, Dyer TP, Smyrk K. Non-injection and injection drug use and STI/HIV risk in the United States: the degree to which sexual risk behaviors versus sex with an STI-infected partner account for infection transmission among drug users. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(3):1185–1194. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0276-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khan MR, Doherty IA, Schoenbach VJ, Taylor EM, Epperson MW, Adimora AA. Incarceration and high-risk sex partnerships among men in the United States. J Urban Health. 2009;86(4):584–601. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9348-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khan MR, Epperson MW, Mateu-Gelabert P, Bolyard M, Sandoval M, Friedman SR. Incarceration, sex with an STI- or HIV-infected partner, and infection with an STI or HIV in Bushwick, Brooklyn, NY: a social network perspective. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(6):1110–1117. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.184721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Epperson MW, El-Bassel N, Chang M, Gilbert L. Examining the temporal relationship between criminal justice involvement and sexual risk behaviors among drug-involved men. J Urban Health. 2010;87(2):324–336. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9429-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Epperson MW, Khan MR, Miller DP, Perron BE, El-Bassel N, Gilbert L. Assessing criminal justice involvement as an indicator of human immunodeficiency virus risk among women in methadone treatment. J Subst Abus Treat. 2010;38(4):375–383. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Martinson FE, et al. Heterosexually transmitted HIV infection among African Americans in North Carolina. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;41(5):616–623. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000191382.62070.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khan MR, Behrend L, Adimora AA, Weir SS, Tisdale C, Wohl DA. Dissolution of primary intimate relationships during incarceration and associations with post-release STI/HIV risk behavior in a Southeastern City. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38(1):43–47. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181e969d0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khan MR, Behrend L, Adimora AA, Weir SS, White BL, Wohl DA. Dissolution of primary intimate relationships during incarceration and implications for post-release HIV transmission. J Urban Health. 2011;88(2):365–375. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9538-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kawachi I, Berkman LF. Social ties and mental health. J Urban Health. 2001;78(3):458–467. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.3.458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khantzian EJ. Addiction as a self-regulation disorder and the role of self-medication. Addiction. 2013;108(4):668–669. doi: 10.1111/add.12004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scheidell JD, Lejuez CW, Golin CE, Adimora AA, Wohl DA, Keen LD, II, Hammond M, Judon-Monk S, Khan MR. Patterns of mood and personality factors and associations with STI/HIV-related drug and sex risk among African American male inmates. Subst Use Misuse. 2017;52:929–938. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2016.1267221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scheidell JD, Lejuez CW, Golin CE, Hobbs MM, Wohl DA, Adimora AA, Khan MR. Borderline personality disorder symptom severity and sexually transmitted infection and HIV risk in African American incarcerated men. Sex Transm Dis. 2016;43(5):317–323. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meade CS, Sikkema KJ. HIV risk behavior among adults with severe mental illness: a systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2005;25(4):433–457. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Binswanger IA, Blatchford PJ, Mueller SR, Stern MF. Mortality after prison release: opioid overdose and other causes of death, risk factors, and time trends from 1999 to 2009. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(9):592–600. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-9-201311050-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Binswanger IA, Nowels C, Corsi KF, Glanz J, Long J, Booth RE, Steiner JF. Return to drug use and overdose after release from prison: a qualitative study of risk and protective factors. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2012;7:3. doi: 10.1186/1940-0640-7-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stephenson BL, Wohl DA, McKaig R, Golin CE, Shain L, Adamian M, Emrick C, Strauss RP, Fogel C, Kaplan AH. Sexual behaviours of HIV-seropositive men and women following release from prison. Int J STD AIDS. 2006;17(2):103–108. doi: 10.1258/095646206775455775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morrow KM, Project SSG. HIV, STD, and hepatitis risk behaviors of young men before and after incarceration. AIDS Care. 2009;21(2):235–243. doi: 10.1080/09540120802017586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carson EA. Prisoners in 2016 US Department of Justice - Bureau of Justice Statistics. 2018. Available at:https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/p16.pdf. Accessed 20 June 2017.

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV among Women. 2017; https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/gender/women/index.html. Accessed September, 2017.

- 22.Khan MR, Golin CE, Friedman SR, Scheidell JD, Adimora AA, Judon-Monk S, Hobbs MM, Dockery G, Griffin S, Oza KK, Myers D, Hu H, Medina KP, Wohl DA. STI/HIV sexual risk behavior and prevalent STI among incarcerated African American men in committed partnerships: the significance of poverty, mood disorders, and substance use. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(8):1478–1490. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1062-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Radloff L. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Comfort M, Reznick O, Dilworth SE, Binson D, Darbes LA, Neilands TB. Sexual HIV risk among male parolees and their female partners: the relate project. J Health Dispar Res Pract 2014;7(6):42–69. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.National Institute on Drug Abuse . Risk Behavior Assessment. 3. Rockville: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 26.First MB, Vettorello N, Frances AJ, Pincus HA. Changes in mood, anxiety, and personality disorders. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1993;44(11):1034–1036, 1043. doi: 10.1176/ps.44.11.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robinson AL, Heaton RK, Lehman RA, Stilson DW. The utility of the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test in detecting and localizing frontal lobe lesions. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1980;48(5):605–614. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.48.5.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maldonado G, Greenland S. Simulation study of confounder-selection strategies. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;138(11):923–936. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.El-Bassel N, Gilbert L, Terlikbayeva A, et al. Effects of a couple-based intervention to reduce risks for HIV, HCV, and STIs among drug-involved heterosexual couples in Kazakhstan: a randomized controlled trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;67(2):196–203. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.El-Bassel N, Gilbert L, Wu E, et al. Couple-based HIV prevention for low-income drug users from New York City: a randomized controlled trial to reduce dual risks. Jaids-J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;58(2):198–206. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318229eab1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.El-Bassel N, Witte SS, Gilbert L, et al. The efficacy of a relationship-based HIV/STD prevention program for heterosexual couples. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(6):963–969. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.6.963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.El-Bassel N, Witte SS, Gilbert L, et al. Long-term effects of an HIV/STI sexual risk reduction intervention for heterosexual couples. AIDS Behav. 2005;9(1):1–13. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-1677-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 24 kb)