Abstract

Women living in urban settings who are engaged in the criminal justice system are disproportionately affected by HIV and also contend with poor sexual and reproductive health (SRH). While studies have examined environmental influences of HIV, few have examined how these influences relate to poor SRH among this population. We used baseline data from an HIV-risk reduction study among substance-using women with a pregnancy history in community corrections in New York City (N = 299). We examined risk environment factors typically associated with HIV, and SRH outcomes of abortion, and miscarriage. We used logistic regression models to examine associations between risk environment factors with SRH outcomes. Most women identified as black and ranged in age from 18 to 62. Approximately half had miscarriages and/or abortions in their lifetime. Few women used birth control despite not wanting children in the future. While most women faced high rates of environmental influences of HIV risk, only intimate partner violence (IPV) was associated with SRH outcomes. Women experiencing IPV were significantly more likely to report both miscarriage and abortion. Community corrections present a unique opportunity for intervention around HIV risk reduction and SRH outcomes, given that effective programming for each often requires multiple and formal contacts with health providers.

Keywords: Criminal justice, Intimate partner violence, HIV, Reproductive health, Risk environment

Introduction

The USA has had the highest rate of incarceration globally since 2002 [1, 2]. Though most recent national data indicate steady declines in rates of incarceration, the rate of female incarceration has increased at nearly double the rate of male incarceration since 2002 [3]. Black and Latina women from urban settings are overrepresented in the criminal justice system. Recent data show that 30 and 16% of incarcerated women are black and Latina, respectively [4]. Black women are incarcerated at four times the rate of white women [3, 5, 6]. Further, there are approximately one million American women in community correction programs, such as probation, parole, or alternative-to-incarceration programs [7]. Community correction programs represent the largest and fastest growing segment of the criminal justice population, with over-representation of women living in urban settings [7].

Given the rapidly expanding rate of incarcerated women, it is important that we consider the unique health concerns of this population. Women in the criminal justice system do not receive the health care they need and have lower rates of utilization prior to entering [8–12]. Using programs for women that were designed for male-majority prisons result in programming incongruent with the unique needs of women [10, 11]. Research examining the sexual and reproductive health of women involved in the criminal justice system, though limited, indicates substantial need for better understanding and programming to improve sexual and reproductive health among this population of vulnerable women [8–10]. Unplanned pregnancies among incarcerated women are common and often associated with delivery complications due to lack of access to and/or utilization prenatal care [13]. Clarke and colleagues examined pregnancy attitudes among women entering US jails and found that though almost half of their sample did not want to become pregnant, that these women were more likely to report having a history of unplanned pregnancies and abortions [13]. Contraceptive use among this population is also low. Sufrin and colleagues found that among a sample of incarcerated women, over half (55%) reported prior abortions, and that only 68% of women reported current use of contraception [2].

Black and Latina women, who make up a large proportion of women in community corrections in the USA, suffer from alarmingly poor sexual and reproductive health. This population of women has the lowest rates of contraceptive use in the USA [14], and according to the most recent national data, non-Hispanic black women had the highest abortion rate and ratio, relative to other racial groups in 2012 [15]. Further, black and Latina women suffer from higher rates of negative pregnancy outcomes. Black women are significantly more likely to have spontaneous preterm birth and fetal growth restriction [16], though little is known as to causes of such high rates of negative health outcomes in this population. Finally, multiple studies indicate that black women have increased risk of miscarriage relative to other racial groups in the USA [17–20].

Existing research on sexual health among women from urban settings engaged in the criminal justice system has primarily focused on women’s HIV risk behaviors and outcomes, mostly in relation to their substance use history (injection drug use) [21]. HIV prevalence among substance-using women engaged with the criminal justice system ranges between 13 and 17% [22]. In addition to contending with poor reproductive health, black and Latina women also have the highest rates of HIV among cases transmitted through heterosexual sexual contact. In 2014, in the USA, black and Latina heterosexual women accounted for 5814 new cases of HIV (compared to 1115 new cases among white women) [23]. However, studies show that this population of women also contends with increased risk for HIV due to high rates of unprotected sex, often as a result of coercion from male partners. High rates of unprotected sex not only leave women vulnerable to HIV acquisition, but also puts them at risk for adverse reproductive health concerns (unwanted pregnancy, limited contraceptive use, pregnancy complications). While much attention has been focused on HIV as a product of high rates of unprotected sex among this population, much less attention has been focused on the reproductive health outcomes that also come from these risky behaviors. Further, little is known about how environmental influences may be associated with reproductive health outcomes of women engaged in the criminal justice system.

Pregnancies that end in abortions are generally considered unintended [24, 25] and are more likely to occur as a result of IPV [24, 26, 27]. Studies document positive association between women’s experience of IPV victimization and lack of control over their reproductive decision-making (e.g., contraceptive use) [28, 29]. Having control over contraception and reproduction is often further compounded if women are exchanging sex for resources (money, housing, etc). Additional studies indicate that women facing negative relationship factors, such as difficult relationships or having partners unable to support a baby, were more likely to have abortions [30].

The majority of miscarriages are thought to be caused by biological factors such as aneuploidy, uterus abnormalities, and endocrine disorders [31, 32]. However, a growing body of literature indicates that some social (IPV, racial discrimination-related stress) and behavioral (substance use, poor nutrition, trauma) factors are also associated with miscarriage [33, 34]. Despite the high rate of miscarriage among minority populations in the USA, few studies have examined environmental risk factors that may influence women’s risk for miscarriage.

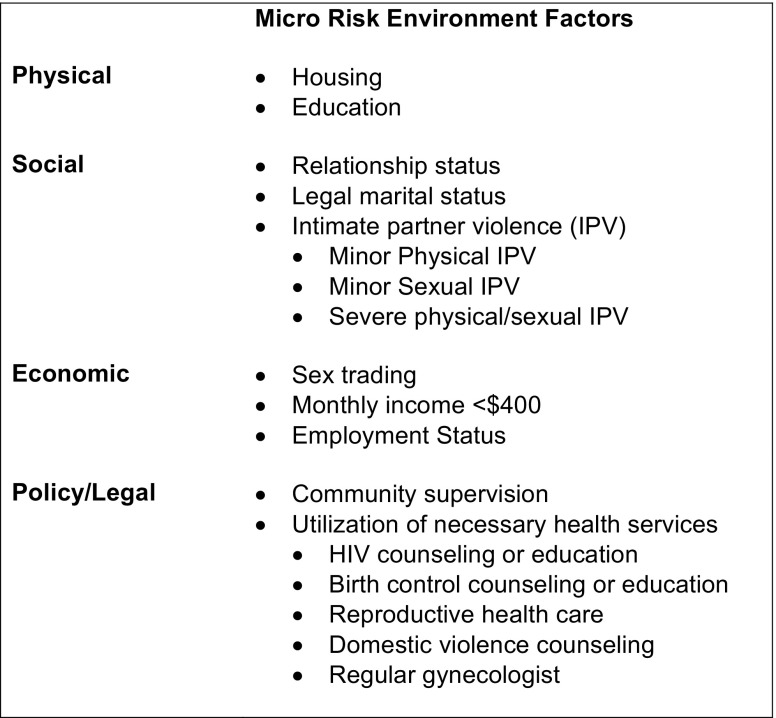

Rhodes and colleagues [35, 36] developed a conceptual model described as the risk environment framework, to understand multilevel (micro and macro) physical, social, economic, and policy/legal factors (intimate partner violence, sex work, homelessness, lack of access to health services, etc) that contribute to health disparities, drug use, and HIV risk behaviors. We used the micro level of this framework to understand the environmental influences associated with reproductive health concerns of abortion and miscarriage. The micro environments are as follows: micro-physical (housing, education), micro-social (relationship status, legal marital status IPV), micro-economic (sex trading, monthly income, employment status), and micro-policy/legal (community supervision, utilization of health services) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Environmental influences of abortion and miscarriage among substance-using women recruited from community correction sites in New York City

This paper addresses a major gap in the literature by describing sexual reproductive health (abortion, miscarriage, contraceptive use, access, and use of reproductive services) of substance-using women involved in the criminal justice system. We further examine the association of two major reproductive health outcomes (abortion and miscarriage) with risk environment factors including micro physical (homelessness, low education), social (intimate partner violence, relationship status, legal marital status), economic (sex trading, low income, unemployment), and policy/legal (community supervision and utilization of health services) factors. We hypothesize that women who are exposed to micro risk environment factors are more likely to experience abortion and miscarriage.

Methods

Study Population and Data Collection

This paper uses baseline data (N = 337) from Project WORTH (Women on the Road to Health). WORTH is an HIV risk reduction intervention study for women under community supervision evaluated through a randomized controlled trial. Full details on WORTH study methodology are published elsewhere [37, 38]. Women completed baseline interviews via Computer Assisted Self-Interview (CASI) programming and were tested for HIV and STIs. Research staff recruited women from community courts and probation sites in New York City.

Eligibility Criteria for Project WORTH

Eligibility criteria for study participation included being the following: (1) 18 years or older and biologically female at birth; (2) under community supervision, on probation or parole, or under drug treatment court supervision within the past 90 days; (3) reporting one or more incidents of illicit drug use within the past 6 months; (4) reporting one or more acts of unprotected intercourse within the past 90 days; and (5) being HIV positive or at risk for HIV. Research staff administered surveys at baseline, 3-month, 6-month, and 12-month follow-up periods, with biological testing conducted at baseline and 12-month follow-up.

Study participants completed written informed consent for participation and were compensated with $30 for completing the baseline CASI interview and biological testing. Study procedures were approved by institutional review boards at Columbia University and the Center for Court Innovation.

Measures

For this paper, we used a number of micro-level risk environment factors (physical, social, economic, policy/legal) that we hypothesize to be associated with abortion and miscarriage (Fig. 1).

Individual Factors

Demographic

Data were collected from participants on their age (measured continuously in years) and race/ethnicity [categorized as black or African American, Hispanic or Latina, or Other (white/Caucasian, Caribbean/West Indian, American Indian/Alaskan Native, Asian, Southeast Asian, or Pacific Islander, other)].

Biological Factors

HIV tests were collected through oral swabs (OraQuick ADVANCE Rapid HIV Test), and women provided self-collected vaginal swab specimens to be tested for chlamydia, trichomoniasis, and gonorrhea.

Substance Use Factors

The risk behavior assessment [39] was used to assess individual risk factors of substance use history ever in life. Binge drinking was based on women’s reports of drinking four or more alcoholic drinks within a 6-h period [40]. Heroin and crack cocaine use were measured separately and included all methods of ingestion (smoking and injecting) for both drugs.

Micro Risk Environmental Factors

Micro-Physical

Homelessness in the past 90 days, women’s education, and community supervision involvement were factors considered in the macro-physical risk environment.

Micro-Social

We assessed the micro-physical risk environment through assessment of lifetime history of intimate partner violence. IPV victimization was measured through a shortened 8-item version of the Revised Conflict Tactic Scale [41]. Subscales with separate questions for minor physical, minor sexual, and severe physical and/or sexual violence experiences were used for the present analyses. Internal consistency of the subscales ranged from 0.87 (minor sexual IPV) to 0.89 (minor physical IPV and severe physical/sexual IPV).

Women were asked their legal marital status, and if they were currently in a relationship with someone or not, as part of their micro-social risk environment.

Micro-Economic

In order to assess women’s micro-economic risk environment, women were asked if they traded sex for money, drugs, alcohol, food, and/or other resources in the past 90 days. We assessed for women’s employment status and monthly income (responses less than $400 per month or greater than $400 per month).

Micro-Policy/Legal

Community supervision involvement was assessed by asking women if they had (1) ever been arrested and/or incarcerated, (2) ever been arrested due to a drug charge, (3) ever been in jail, (4) ever been in prison, (5) ever been under community supervision in community court, (6) ever been on probation, or (7) ever been on parole.

Women’s access and utilization of health services were used to understand the micro-policy/legal risk environment in which women operated. Access to health services was assessed by asking women if, in the past 90 days, they received a health service, and if they had not received the service, if they needed this service. Women were also asked if they had a regular gynecologist.

Reproductive Health Outcomes

We asked the participants regarding their history of abortion and miscarriage, which were measured as follows: women who reported a history of pregnancy were asked how many of their pregnancies had ended in abortions or miscarriage (separately). In both cases, we dichotomized the responses to women reporting 1 or more abortions or miscarriages as “yes” (all else “no”).

Additional Reproductive Health Factors

Other reproductive factors were considered descriptively: number of pregnancies, women not trying to have children in the future, if women were pregnant at time of survey, and current birth control [pill, IUD, permanent methods (tubal ligation, uterectomy, or ovarectomy), injectables, natural methods, none].

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics (proportions and frequencies) were calculated to describe the sample of women who completed the baseline survey and had a history of pregnancy pregnant (N = 299). We compared women who had abortions with those who had not through been pregnant using Chi-square tests for non-continuous variables, and t tests for continuous variables. We conducted the same analyses for miscarriages. We conducted univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses to estimate associations between risk environment factors and each reproductive health outcome (abortion and miscarriage). We included risk environmental factors achieving significance at p < 0.05 from the univariate analysis simultaneously in multivariate models. Collinearity was assessed across all variables; however, in order to address co-linearity, three separate multivariate models were created (one for each form of IPV—physical IPV, sexual IPV, severe physical/sexual IPV) for outcomes of abortion and miscarriage. All analyses were conducted using SPSS 24 (Durham, NC).

Results

Reproductive Health Outcomes: Abortion and Miscarriage

Table 1 illustrates that over half of women (53%, n = 157) reported having an abortion in their lifetime, with 1.1 abortions on average per woman (SD: 1.6, range 0–10 abortions). Close to half (46%) of women reported having miscarriages in their lifetime. Women had 4.7 pregnancies on average (SD: 3.0, range: 0–20), with 45% reporting 5 or more pregnancies in their lifetime. At the time of the interview, 4% of women were pregnant, the majority (90%) was not trying to get pregnant, and 67% said they did not plan on getting pregnant in the future.

Table 1.

Sexual and reproductive health among substance-using women recruited from community correction sites in New York City (N = 299)

| Reproductive health characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Number of pregnancies [mean, (SD, range)] | 4.7 (3.0, 0–20) |

| History of miscarriage | 137 (46%) |

| History of abortions | 157 (53%) |

| Not trying to get pregnant (currently) | 269 (90%) |

| Do not plan to have children in the future | 226 (67%) |

| Currently pregnant | 13 (4%) |

| Birth controla (current) | |

| Condoms | 22 (9%) |

| Pill | 27 (10%) |

| IUD | 17 (5%) |

| Injection (depo)/implants/patch | 16 (6%) |

| Permanent Methods | 60 (23%) |

| Abstinence/withdrawal/rhythm | 9 (4%) |

| Health service utilization | |

| Did not receive health service in past 90 days, but needed service | |

| HIV counseling or education (n = 146) | 36 (25%) |

| STD counseling or education (n = 162) | 36 (22%) |

| Birth control counseling or education (n = 200) | 25 (13%) |

| Reproductive health care (n = 188) | 37 (20%) |

| Domestic violence counseling (n-187) | 21 (11%) |

| Assistance from police regarding domestic violence (n = 196) | 6 (3%) |

| Drug or alcohol counseling/treatment (n = 115) | 13 (11%) |

| Women who do not have a regular gynecologist | 110 (37%) |

aWomen trying to get pregnant (n = 30) and pregnant women (n = 13) were excluded

Table 1 shows that among those women who were not trying to get pregnant and were not pregnant at the time of the survey, 9% reported condom use as a method of birth control, 10% reported using hormonal contraceptive pills, 5% reported using intrauterine devices (IUDs), and 6% reported using a non-oral hormonal contraceptive. Permanent methods of contraception were slightly more popular among women, and some women (4%) reported using natural methods (abstinence, withdrawal, or rhythm method) as birth control.

Individual Factors

Demographic Factors

Table 1 shows that the average age for the sample was 42 years (SD = 10.0) and ranged from 18 to 62 years of age. Over half of the sample (67%) identified as black or African American, and 17% identified as Hispanic or Latina. Demographic factors did not vary based on miscarriage or abortion history.

Biological Factors

As Table 2 shows, 14 and 26% of women tested positive for HIV and STIs, respectively. Similar proportions of women were HIV-positive among those who had abortions (12%) and miscarriage (11%). Though a larger proportion of women with a history of miscarriage tested positive for STIs (36%) relative to those who had abortions (22%), no significant differences were seen across groups for either outcome.

Table 2.

Associations between micro-risk environment framework factors and sexual and reproductive health (abortion and miscarriage) among substance-using women recruited from community correction sites in New York City (N = 299)

| Variable | Total | History of abortion (n = 157) | History of miscarriage (n = 137) |

|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 299) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | ||

| Individual factors | |||

| Demographic factors | |||

| Age [mean (SD, range)] | 42.0 (10.0, 18–62) | 40.9 (10.0, 19–58) | 42.7 (9.7, 20–58) |

| 0.98 (0.95, 1.00) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.04) | ||

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Black or African American | 199 (67%) | 97 (62%) | 85 (62%) |

| Hispanic or Latina | 51 (17%) | 31(20%) | 26 (19%) |

| Other | 49 (16%) | 29 (19%) | 26 (19%) |

| 1.29 (0.95, 1.75) | 1.25 (0.93, 1.69) | ||

| Biological factors | |||

| HIV-positive | 41 (14%) | 19 (12%) | 15 (11%) |

| 0.75 (0.39, 1.45) | 0.63 (0.32, 1.25) | ||

| Any STI | 78 (26%) | 34 (22%) | 35 (36%) |

| 0.62 (0.37, 1.04) | 0.95 (0.57, 1.60) | ||

| Substance use factors (ever) | |||

| Binge drinking | 167 (56%) | 95 (61%) | 83 (61%) |

| 1.49 (0.94, 2.36) | 1.43 (0.90, 2.26) | ||

| Heroin | 61 (20%) | 33 (21%) | 26 (19%) |

| 1.08 (0.62, 1.91) | 0.85 (0.48, 1.50) | ||

| Crack cocaine | 240 (80%) | 125 (80%) | 109 (80%) |

| 0.92 (0.52, 1.62) | 0.92 (0.52, 1.63) | ||

| Micro-physical risk environment | |||

| Homelessness, past 90 days | 31 (10%) | 13 (8%) | 10 (7%) |

| 0.622 (0.29, 1.32) | 0.53 (0.24, 1.17) | ||

| <HS diploma/no formal education | 126 (42%) | 59 (38%) | 58 (42%) |

| 0.67 (0.43, 1.07) | 1.02 (0.64, 1.61) | ||

| Micro-social risk environment | |||

| Relationship status | |||

| In a relationship | 244 (82%) | 126 (80%) | 110 (80%) |

| Not in a relationship | 55 (18%) | 31 (20%) | 27 (20%) |

| 0.83 (0.46, 1.49) | 0.85 (0.47, 1.53) | ||

| Marital status | 251 (84%) | 135 (86%) | 115 (84%) |

| Single | 48 (16%) | 22 (14%) | 22 (16%) |

| Married | 1.38 (0.74, 2.56) | 1.00 (0.54, 1.86) | |

| Lifetime history of intimate partner violence (IPV) | |||

| Minor physical IPV | 186 (62%) | 106 (68%)* | 100 (73%)** |

| 1.61 (1.01, 2.58) | 2.39 (1.47, 3.89) | ||

| Minor sexual IPV | 168 (56%) | 98 (62%)* | 88 (64%)* |

| 1.71 (1.08, 2.71) | 1.84 (1.16, 2.93) | ||

| Severe physical and/or sexual IPV | 174 (58%) | 100 (64%)* | 94 (69%)** |

| 1.61 (1.02, 2.56) | 2.24 (1.39, 3.60) | ||

| Micro-economic risk environment | |||

| Unemployment | 272 (91%) | 137 (87%)* | 124 (91%) |

| 2.82 (1.15, 6.88) | 1.11 (0.50, 2.45) | ||

| Monthly income <$400 | 169 (57%) | 85 (54%) | 69 (50%) |

| 1.23 (0.78, 1.94) | 1.59 (1.00, 2.52) | ||

| Sex trading (past 90 days) | 79 (26%) | 47 (30%) | 36 (26%) |

| 1.47 (0.87, 2.47) | 0.99 (0.49, 1.65) | ||

| Micro-policy/legal risk environment | |||

| Community supervision | |||

| Ever arrested | 296 (98%) | 154 (98%) | 136 (99%) |

| 1.11 (0.22, 5.58) | 4.33 (0.50, 37.53) | ||

| Arrested due to drug charge | 156 (52%) | 72 (46%)* | 70 (52%) |

| 0.59 (0.37, 0.93) | 0.92 (0.59, 1.46) | ||

| Ever in jail | 266 (89%) | 141 (90%) | 120 (88%) |

| 1.20 (0.58, 2.47) | 0.77 (0.38, 1.60) | ||

| Ever in prison | 124 (42%) | 61 (39%) | 60 (44%) |

| 0.80 (0.50, 1.26) | 1.19 (0.75, 1.89) | ||

| Ever in community court, probation, or parole | 269 (90%) | 142 (90%) | 124 (91%) |

| 1.12 (0.53, 2.38) | 1.12 (0.52, 2.39) | ||

| Health service utilization: did not receive health service, but needed service (past 90 days) | |||

| HIV counseling or education (n = 146) | 36 (25%) | 20 (25%) | 22 (31%) |

| 1.08 (0.51, 2.30) | 1.89 (0.88, 4.06) | ||

| Birth control counseling or education (n = 200) | 25 (13%) | 15 (15%) | 14 (15%) |

| 1.52 (0.66, 3.56) | 1.62 (0.70, 3.77) | ||

| Reproductive health care (n = 188) | 37 (20%) | 19 (20%) | 22 (25%) |

| 1.07 (0.52, 2.20) | 1.84 (0.89, 3.82) | ||

| Domestic violence counseling (n = 187) | 21 (11%) | 11 (11%) | 11 (12%) |

| 0.89 (0.36, 2.20) | 1.15 (0.47, 2.86) | ||

| Does not have a regular gynecologist | 110 (37%) | 62 (40%) | 56 (41%) |

| 0.78 (0.49, 1.26) | 0.72 (0.45, 1.16) | ||

*p < 0.05

Substance Use Factors

Over half (56%) of women reported lifetime experiences of binge drinking, 80% reported crack cocaine use, and 20% reported heroin. Similar proportions of women reported using these substances among those with a history of abortion and miscarriage, and no significant differences were seen between women who had a history of abortion or miscarriage and those who had not.

Micro Risk Environmental Factors

Micro-Physical Risk Environment

One-tenth of the sample reported homelessness in the past 90 days, and a little less than half (42%) had less than a high school diploma or equivalent (or reported not having any formal education). There were no significant differences in education level and recent homelessness between women who had a history of abortion or miscarriage and those who had not.

Micro-Social Risk Environment

As shown in Table 2, all forms of IPV were all highly prevalent in our sample of women. Among the total sample, 62% reported minor physical IPV, 56% reported minor sexual IPV, and 58% reported severe physical and/or sexual IPV. Experiences of IPV were higher than the total sample among those with a history of abortion (minor physical IPV: 68%; minor sexual IPV: 62%; severe IPV: 64%). Women with a history of IPV were significantly more likely to report a history of abortion relative to those who had not experienced IPV (minor physical IPV: p = 0.047, minor sexual IPV: p = 0.022, severe IPV: p = 0.043). IPV was highest among those reporting miscarriage, and women reporting all forms of IPV were significantly more likely to report a history of miscarriage relative to those without IPV victimization (minor physical IPV: p < 0.001, minor sexual IPV: p = 0.022, severe IPV: p < 0.001).

The majority (82%) of women were in a relationship, and 16% of the sample was legally married. Neither relationship status nor legal marital status varied among women who did or did not have abortions or miscarriages.

Micro-Economic Risk Environment

The majority (91%) of women reported being unemployed at baseline, and over half (57%) reported having a monthly income less than $400. Women who reported unemployment were significantly more likely to have abortions relative to women with employment (p = 0.019). Women with a monthly income less than $400 were also significantly more likely to report having a miscarriage relative to those who had monthly incomes greater than $400 (p = 0.048). Approximately one-quarter (26%) of women reported exchanging sex for money, drugs, alcohol, food, and/or other resources in the past 90 days. However, no significant differences were seen across groups for either outcome.

Micro-Policy/Legal Risk Environment

History of Criminal Justice Involvement

The majority (98%) of women reported being arrested in their lives, and approximately half (52%) of arrests were due to a drug charge. Of the total sample, 89% reported being in jail at some point in their lifetime, while a little less than half reported ever being in prison (42%) or community court (44%). Almost half (46%) of women who had abortions reported that they were arrested due to a drug charge. Women who were arrested due to drug charge were significantly less likely than those not arrested for drug charges to have an abortion (p = 0.022).

Health Service Utilization

Less than one-quarter reported that they had not received HIV counseling or education (25%), or reproductive health care (20%), when they needed that service, and 37% reported that they did not have a regular gynecologist. Similar proportions of health service utilization and need were seen across reproductive health outcomes (no significant differences were detected).

Multivariate Associations between Risk Environment Factors and Reproductive Health Outcomes (Abortion, Miscarriage)

We tested the hypothesis that women experiencing risk environment factors would be more likely to report negative reproductive health outcomes. We included risk environment factors achieving significance at p < 0.05 from the univariate analyses. For our first outcome of abortion, this included all three forms of IPV, arrests due to drug charge, and unemployment. As described previously, we conducted three separate multivariate regressions based on form of IPV given high collinearity between the IPV variables.

Table 3 shows micro risk environment factors independently associated with women’s history of abortion. These models included the following factors: physical IPV, arrests due to drug charge, and unemployment, which were significant in the univariate models (p < 0.05). Women with a history of physical IPV (AOR: 1.62, 95% CI: 1.00, 2.62), arrests due to drug charge (AOR: 0.61, 95% CI: 0.38, 0.97), and unemployment (AOR: 2.65, 95% CI: 1.07, 6.56) were all significantly more likely to report having a history of abortion. Similar results were observed for models 2 (sexual IPV) and 3 (severe physical and/or sexual IPV). Women’s history of sexual IPV (AOR: 1.78, 95% CI: 1.11, 2.85), arrests due to drug charge (AOR: 0.61, 95% CI: 0.38, 0.97), and unemployment (AOR: 2.80, 95% CI: 1.13, 6.56) were all independently associated with women’s history of abortion. Finally, severe physical and/or sexual IPV (AOR: 1.61, 95% CI: 1.01, 2.58), arrests due to drug charge (AOR: 0.61, 95% CI: 0.38, 0.98), and unemployment (AOR: 2.65, 95% CI: 1.017, 6.54) all remained significantly associated with women’s reports of abortion in the final adjusted model, as well.

Table 3.

Factors independently associated with women’s history of abortion among substance-using women in community corrections in New York City (N = 299)

| Model 1a | Model 2b | Model 3c | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | AOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) |

| Micro-social risk environment | |||

| Lifetime history of intimate partner violence (IPV) | |||

| Minor physical IPV | 1.62 (1.00, 2.62)* | - | - |

| Minor sexual IPV | - | 1.78 (1.11, 2.85)* | - |

| Severe physical and/or sexual IPV | - | - | 1.61 (1.01, 2.58)* |

| Micro-policy/legal risk environment | |||

| Community supervision | |||

| Arrested due to drug charge | 0.61 (0.38, 0.97)* | 0.61 (0.38, 0.97)* | 0.61 (0.38, 0.98)* |

| Micro-economic risk environment | |||

| Unemployment | 2.65 (1.07, 6.56)* | 2.80 (1.13, 6.95)* | 2.65 (1.07, 6.54)* |

*p < 0.05

**p < 0.001

aModel 1 = physical IPV

bModel 2 = sexual IPV

cModel 3 = severe physical/sexual IPV

Table 4 illustrates the relationship between micro risk environment factors independently associated with miscarriage. These models included the following factors, which were found to be significant in the univariate analyses (p < 0.05). Three forms of IPV (minor physical, minor sexual, and severe physical and/or sexual IPV) and monthly income less than $400 with women’s history of miscarriage. While monthly income less than $400 did not remain significant after including any form of IPV in each model, all three forms of IPV remained significantly associated with women’s history of miscarriage after controlling for monthly income (physical IPV-AOR: 2.38, 95% CI: 1.46, 3.89; sexual IPV-AOR: 1.79, 95% CI: 1.12, 2.86; and severe physical and/or sexual IPV-AOR: 2.19, 95% CI: 1.36, 3.53).

Table 4.

Factors independently associated with women’s history of miscarriage among substance-using women in community corrections in New York City (N = 299)

| Model 1a | Model 2b | Model 3c | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | AOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) |

| Micro-social risk environment | |||

| Lifetime history of intimate partner violence (IPV) | |||

| Minor physical IPV | 2.38 (1.46, 3.89)** | - | - |

| Minor sexual IPV | - | 1.79 (1.12, 2.86)* | - |

| Severe physical and/or sexual IPV | - | - | 2.19 (1.36, 3.53)* |

| Micro-economic risk environment | |||

| Monthly income <$400 | 1.58 (0.99, 2.53) | 1.53 (0.96, 2.44) | 1.53 (0.95, 2.44) |

*p < 0.05

**p < 0.001

aModel 1 = physical IPV

bModel 2 = sexual IPV

cModel 3 = severe physical/sexual IPV

Discussion

This paper addresses an important gap in the literature by examining the sexual and reproductive health concerns of substance-using women in community corrections. Our findings show that approximately half of the women in our study had abortions and/or miscarriages in their lifetime, building on the scarce existing literature on the topic, and providing additional data for future intervention research with this population.

Our findings are consistent with Sufrin and colleagues [2], who found that 54% of their sample of women in San Francisco jails had abortions in their lifetime. Though our findings on abortion rates are similar to this study, it is important to note that Sufrin’s sample was limited to a small sample of women who had long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARC) inserted while in prison. Women opting for LARC are the minority in not only community correction populations [2, 12], but also in the general population [42]. Our findings build on this research and highlight similar rates of abortion in our population at heightened risk for HIV. We found rates of abortion that were higher than research published by Clarke and colleagues [13, 43], examining reproductive health among incarcerated women in Rhode Island (35% of their population reported abortions). However, less than half of this population identified as black or Latina, whereas the women in our study were primarily black and Latina women.

Our study also contributes to the small body of literature documenting unmet need for family planning services among women in community corrections [2, 44]. At the time of survey, 90% of our sample reported that they were not trying to get pregnant, and 67% reported that they did not plan to have children in the future. This is startling given that entry criteria into our study included women reporting one or more acts of unprotected intercourse within 90 days prior to survey. The level of unmet need in our sample was greater than existing studies; however, other studies focused on incarcerated women, rather than among our larger population of women in community corrections.

Data on miscarriage rates among women in community corrections are primarily based in research on rates of pregnancy complications associated with substance-using women who are often engaged with the criminal justice system. The majority of this research has focused on the negative effects of substance misuse during pregnancy and the resulting negative biological and behavioral effects to the fetus [34]. Previous research has also shown higher rates of pregnancy loss among black and Latina women [17]. In our sample, women who had a history of binge drinking and/or using crack cocaine made up the majority of those having abortions and/or miscarriages. However, associations between women’s drug use and reproductive health outcomes were not significant. We saw the same for women’s race; there were no significant associations between [18–20, 45] race and women’s experiences of abortion or miscarriage. However, in both unadjusted and adjusted models examining associations between women’s history of arrests due to a drug charge and abortion, we saw that women who were arrested due to drug charge were significantly less likely to report having abortions. These results are in contrast to our hypotheses that women experiencing micro-level risk environment factors would be more likely to report negative sexual and reproductive health outcomes. While further research must be conducted to better understand such associations, one plausible explanation is that women who were arrested due to drug possession may represent a segment of the study population that had further competing concerns relative to those who were not arrested for drug charges, which may have inhibited their access to abortion services.

Various factors in the micro-economic risk environment were significantly associated with abortion and miscarriage in our sample. We found women’s unemployment (micro-economic risk environment) to be significantly associated with women’s history of abortion. Financial factors, such as unemployment, have been cited elsewhere as motivations for women to discontinue pregnancies [30]. In model testing associations with miscarriage, we found that women who had a monthly income less than $400 were more likely to report having miscarriages, though this association did not remain significant in the final multivariate models. It is possible that women who had lower monthly income had lower access to food and prenatal care necessary to ensure a healthy pregnancy and delivery.

The micro-social environment had the greatest number of factors significantly associated with both reproductive health outcomes. IPV was highly prevalent in both the total sample and among those who had abortions and miscarriages. In all IPV models, women experiencing IPV were more likely to have abortions and/or miscarriages. These findings are in line with existing literature documenting the relationship between IPV and poor sexual and reproductive health in a variety of settings both in the USA and globally [46–49]. However, our results are the first to document such a relationship within the community correction setting. Studies have shown that women experiencing IPV often have limited control over their contraceptive decision-making [50], and as a result often have higher rates of unintended pregnancies relative to women not experiencing IPV [26, 51]. Much of this research has been generated from the HIV literature, showing that women face challenges in condom negotiation with partners who perpetrate violence, or in relationships characterized by imbalanced power dynamics [51]. Clarke and colleagues [43] found that women in their study were at high risk for contracting HIV and STIs (multiple sexual partners and low consistent condom use). Given that women in this study were recruited from the baseline survey of an HIV risk reduction intervention study with eligibility criteria of high-risk HIV behaviors (including sexual risk behaviors), it is clear that women in this sample face dual risk in HIV/STI risk, as well as having unintended pregnancies (resulting in abortions).

Understanding the relationship between IPV and miscarriage may also be tied to some of the same relationship dynamics that may have led to limited control over contraceptive use among this population. Research from the USA shows that women experiencing partner violence are less likely to access and utilize prenatal care and other necessary pregnancy services [52]. In our sample, one-fifth of the population did not receive reproductive health care when they needed it, and almost 40% said they did not have a regular gynecologist. The majority of incarcerated women have at least one child of minor age [53], and between six and 10% of female prisoners are pregnant upon entering incarceration [54, 55], demonstrating the need for better access to sexual and reproductive care for this population.

Our findings must be considered in light of a number of limitations. Given that we analyzed cross-sectional data without information on temporal sequence of events, we are not able to assess causal relationships between HIV risk environment factors and women’s history of abortion or miscarriage. Related to this, there were a few environmental factors, which were only asked regarding the 90 days prior to survey, which differs significantly from other measures used in the analyses, which asked women about lifetime history of their experiences. In addition, due to the nature of phrasing around birth control use (lack of specific timeframe), we were not able to assess relationship between contraceptive use and our outcomes. Finally, the findings from this study should not be generalized to the larger population of women engaged in the criminal justice system, given the specific entry criteria (especially around HIV risk behaviors) women met in order to take the baseline survey.

Despite these limitations, our findings offer insight into the sexual and reproductive health needs of women in urban criminal justice settings. Simultaneously, there are calls for women seeking contraception and abortion services to also receive services and programming around IPV, and for better integration of reproductive health (contraception and abortion) services for women in the correction system [56]. Health services within the criminal justice system present an opportunity for women in community corrections to receive the necessary integrated health care they need.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Study procedures were approved by institutional review boards at Columbia University and the Center for Court Innovation.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the assistance of the Center for Court Innovation and the New York City Department of Probation for supporting the implementation of this study and we want to particularly thank the women who participated in this study. We also wish to acknowledge the National Institute on Drug Abuse for providing funding " A multimedia HIV/STI intervention for black drug-involved women on probation" (5R01DA03812204).

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institute of Drug Abuse (grant #R01DA025878, and grant #DA037801), and the National Institute of Mental Health (grant #MH019139).

Contributor Information

Anindita Dasgupta, Phone: +1-212-851-2300, Email: ad3341@columbia.edu.

Alissa Davis, Email: ad3324@cumc.columbia.edu.

Louisa Gilbert, Email: lg123@columbia.edu.

Dawn Goddard-Eckrich, Email: dg2121@columbia.edu.

Nabila El-Bassel, Email: ne5@columbia.edu.

References

- 1.Tsai T, Scommenga P. U.S. has world's highest incarceration rate. 2012. http://www.prb.org/Publications/Articles/2012/us-incarceration.aspx. Accessed 15 May 2017.

- 2.Sufrin C, Oxnard T, Goldenson J, Simonson K, Jackson A. Long-acting reversible contraceptives for incarcerated women: feasibility and safety of on-site provision. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2015;47(4):203–211. doi: 10.1363/47e5915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.INCITE. Women of Color & Prisons. 2014. http://www.incite-national.org/page/women-color-prisons. Accessed 15 May 2017.

- 4.American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). Facts about the over-incarceration of women in the United States. 2016. https://www.aclu.org/other/facts-about-over-incarceration-women-united-states. Accessed 15 May 2017.

- 5.Glaze L, Bonczar T. Probation and parole in the United States, 2012. Washington, D.C.: Bureau of Justice Statitistics; 2012.

- 6.Sabol W, Couture H. Prison inmates at midyear, 2007. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2008. NCJ 221944

- 7.Maruschak L, Bonczar T. Probation and parole in the United States, 2012. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statitistics; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freudenberg N. Adverse effects of US jail and prison policies on the health and well-being of women of color. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(12):1895–1899. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.92.12.1895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Covington SS. Women and the criminal justice system. Womens Health Issues. 2007;17(4):180–182. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hotelling BA. Perinatal needs of pregnant, incarcerated women. J Perinat Educ. 2008;17(2):37–44. doi: 10.1624/105812408X298372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fearn N, Parker K. Washington State's residential parenting program: an integrated public health, education and social service resource for pregnant inmates and pregnant mothers. Californian Journal of Health Promotion. 2004;2(4):34–48. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sufrin CB, Creinin MD, Chang JC. Contraception services for incarcerated women: a national survey of correctional health providers. Contraception. 2009;80(6):561–565. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2009.05.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clarke JG, Hebert MR, Rosengard C, Rose JS, DaSilva KM, Stein MD. Reproductive health care and family planning needs among incarcerated women. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(5):834–839. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.060236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daniels K, Daughterty J, Jones J, Mosher W. Division of vital statistics. Current contraceptive use and variation by selected characteristics among women aged 15–44: United States, 2011–2013. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics; 2015.

- 15.Pazol K, Creanga A, Jamieson D. Abortion surveillance — United States, 2012. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) 2015;64(SS10):1–40. doi: 10.15585/ss6410a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Janevic T, Stein CR, Savitz DA, Kaufman JS, Mason SM, Herring AH. Neighborhood deprivation and adverse birth outcomes among diverse ethnic groups. Ann Epidemiol. 2010;20(6):445–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Khalil A, Rezende J, Akolekar R, Syngelaki A, Nicolaides KH. Maternal racial origin and adverse pregnancy outcome: a cohort study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;41(3):278–285. doi: 10.1002/uog.12313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mukherjee S, Velez Edwards DR, Baird DD, Savitz DA, Hartmann KE. Risk of miscarriage among black women and white women in a U.S. prospective cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177(11):1271–1278. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oliver-Williams CT, Steer PJ. Racial variation in the number of spontaneous abortions before a first successful pregnancy, and effects on subsequent pregnancies. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2015;129(3):207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Samaja M, Rovida E, Niggeler M, Perrella M, Rossi-Bernardi L. The dissociation of carbon monoxide from hemoglobin intermediate. J Biol Chem. 1987;262(10):4528–4533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strathdee SA, West BS, Reed E, et al. Substance use and HIV among female sex workers and female prisoners: risk environments and implications for prevention, treatment, and policies. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69(Suppl 2):S110–S117. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Belenko S, Langley S, Crimmins S, Chaple M. HIV risk behaviors, knowledge, and prevention education among offenders under community supervision: a hidden risk group. AIDS Educ Prev. 2004;16(4):367–385. doi: 10.1521/aeap.16.4.367.40394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, (Atlanta, Georgia).

- 24.Guttmacher Institute. Unintended pregnancy in the United States. 2016. https://www.guttmacher.org/sites/default/files/factsheet/fb-unintended-pregnancy-us_0.pdf Accessed 15 May 2017.

- 25.Santelli J, Rochat R, Hatfield-Timajchy K, et al. The measurement and meaning of unintended pregnancy. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2003;35(2):94–101. doi: 10.1363/3509403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gazmararian JA, Petersen R, Spitz AM, Goodwin MM, Saltzman LE, Marks JS. Violence and reproductive health: current knowledge and future research directions. Matern Child Health J. 2000;4(2):79–84. doi: 10.1023/A:1009514119423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsui AO, McDonald-Mosley R, Burke AE. Family planning and the burden of unintended pregnancies. Epidemiol Rev. 2010;32(1):152–174. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxq012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller E, Decker MR, McCauley HL, et al. Pregnancy coercion, intimate partner violence and unintended pregnancy. Contraception. 2010;81(4):316–322. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller E, Silverman JG. Reproductive coercion and partner violence: implications for clinical assessment of unintended pregnancy. Expert Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2010;5(5):511–515. doi: 10.1586/eog.10.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Finer LB, Frohwirth LF, Dauphinee LA, Singh S, Moore AM. Reasons U.S. women have abortions: quantitative and qualitative perspectives. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2005;37(3):110–118. doi: 10.1363/3711005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alijotas-Reig J, Garrido-Gimenez C. Current concepts and new trends in the diagnosis and management of recurrent miscarriage. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2013;68(6):445–466. doi: 10.1097/OGX.0b013e31828aca19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krieg S, Westphal L. Immune function and recurrent pregnancy loss. Semin Reprod Med. 2015;33(4):305–312. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1554917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ahmadi R, Ziaei S, Parsay S. Association between nutritional status with spontaneous abortion. Int J Fertil Steril. 2017;10(4):337–342. doi: 10.22074/ijfs.2016.4577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coleman PK, Reardon DC, Cougle JR. Substance use among pregnant women in the context of previous reproductive loss and desire for current pregnancy. Br J Health Psychol. 2005;10(Pt 2):255–268. doi: 10.1348/135910705X25499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rhodes T. The 'risk environment' a framework for understanding and reducing drug-related harm. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2002;13(2):85–94. doi: 10.1016/S0955-3959(02)00007-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rhodes T. Risk environments and drug harms: a social science for harm reduction approach. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2009;20(3):193–201. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.El-Bassel N, Gilbert L, Goddard-Eckrich D, et al. Efficacy of a group-based multimedia HIV prevention intervention for drug-involved women under community supervision: project WORTH. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e111528. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gilbert L, Goddard-Eckrich D, Hunt T, et al. Efficacy of a computerized intervention on HIV and intimate partner violence among substance-using women in community corrections: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(7):1278–1286. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Needle R, Fisher D, Weatherby N, et al. Reliability of self-reported HIV risk behaviors of drug users. Psychology Addictive Behavior. 1995;9(4):242–250. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.9.4.242. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results form the 2013 National Survey on drug use and health: summary of national findings. Rockville: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality; 2013. HHS Publication No. (SMA)14-4863

- 41.Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The revised conflict tactics scale (CTS2): development and preliminary psychometric data. J Fam Issues. 1996;17:283–316. doi: 10.1177/019251396017003001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guttmacher Institute. Contraceptive Use in the United States. 2016. https://www.guttmacher.org/fact-sheet/contraceptive-use-united-states. Accessed 15 May 2017.

- 43.Clarke JG, Rosengard C, Rose J, Hebert MR, Phipps MG, Stein MD. Pregnancy attitudes and contraceptive plans among women entering jail. Women Health. 2006;43(2):111–130. doi: 10.1300/J013v43n02_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sufrin C, Kolbi-Molinas A, Roth R. Reproductive justice, health disparities and incarcerated women in the United States. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2015;47(4):213–219. doi: 10.1363/47e3115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang H, Bracken MB. Tree-based, two-stage risk factor analysis for spontaneous abortion. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;144(10):989–996. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hall M, Chappell LC, Parnell BL, Seed PT, Bewley S. Associations between intimate partner violence and termination of pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2014;11(1):e1001581. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moore AM, Frohwirth L, Miller E. Male reproductive control of women who have experienced intimate partner violence in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(11):1737–1744. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roth L, Sheeder J, Teal SB. Predictors of intimate partner violence in women seeking medication abortion. Contraception. 2011;84(1):76–80. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Silverman JG, Decker MR, McCauley HL, et al. Male perpetration of intimate partner violence and involvement in abortions and abortion-related conflict. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(8):1415–1417. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.173393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bergmann JN, Stockman JK. How does intimate partner violence affect condom and oral contraceptive use in the United States?: a systematic review of the literature. Contraception. 2015;91(6):438–455. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2015.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Miller E, McCauley HL, Tancredi DJ, Decker MR, Anderson H, Silverman JG. Recent reproductive coercion and unintended pregnancy among female family planning clients. Contraception. 2014;89(2):122–128. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2013.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cha S, Masho SW. Intimate partner violence and utilization of prenatal care in the United States. J Interpers Violence. 2014;29(5):911–927. doi: 10.1177/0886260513505711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Flavin J. Our bodies, our crimes: the policing of women’s reproduction in America. New York, NY: New York University Press; 2009.

- 54.Clarke JG, Phipps M, Tong I, Rose J, Gold M. Timing of conception for pregnant women returning to jail. J Correct Health Care. 2010;16(2):133–138. doi: 10.1177/1078345809356533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maruschak LM. Medical problems of jail inmates. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Justice; 2006.

- 56.Paltrow LM. Roe v Wade and the new Jane crow: reproductive rights in the age of mass incarceration. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(1):17–21. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]