Abstract

Although the number of older adults who are arrested and subject to incarceration in jail is rising dramatically, little is known about their emergency department (ED) use or the factors associated with that use. This lack of knowledge impairs the ability to design evidence-based approaches to care that would meet the needs of this population. This 6-month longitudinal study aimed to determine the frequency of 6-month ED use among 101 adults aged 55 or older enrolled while in jail and to identify factors associated with that use. The primary outcome was self-reported emergency department use within 6 months from baseline. Additional measures included baseline socio-demographics, physical and mental health conditions, geriatric factors (e.g., recent falls, incontinence, functional impairment, concern about post-release safety), symptoms (pain and other symptoms), and behavioral and social health risk factors (e.g., substance use disorders, recent homelessness). Chi-square tests were used to identify baseline factors associated with ED use over 6 months. Participants (average age 60) reported high rates of multimorbidity (61%), functional impairment (57%), pain (52%), serious mental illness (44%), recent homelessness (54%), and/or substance use disorders (69%). At 6 months, 46% had visited the ED at least once; 21% visited multiple times. Factors associated with ED use included multimorbidity (p = 0.01), functional impairment (p = 0.02), hepatitis C infection (p = 0.01), a recent fall (p = 0.03), pain (p < 0.001), loneliness (p = 0.04), and safety concerns (p = 0.01). In this population of older adults in a county jail, geriatric conditions and distressing symptoms were common and associated with 6-month community ED use. Jail is an important setting to develop geriatric care paradigms aimed at addressing comorbid medical, functional, and behavioral health needs and symptomatology in an effort to improve care and decrease ED use in the growing population of criminal justice-involved older adults.

Keywords: Geriatrics, Jail, Correctional health, Underserved populations, Emergency medicine

Introduction

Older adults are among the fastest growing sub-populations in the criminal justice system. While the arrest rate for adults age 18–54 fell by 11% from 2002 to 2012, it rose 27% among adults age 55 or older, resulting in more than 600,000 arrests of older adults in 2012, the last year for which such data are publically available [1]. Adults in the criminal justice system are generally considered “older” in their 50s due to a disproportionately high prevalence of early-onset multimorbidity and disability [2–5]. The great majority of people whose arrest leads to an incarceration will spend time either awaiting trial or serving their sentence in a local jail (compared to prisons, which are typically used for people serving sentences of one or more years) [6]. Over 95% of those in jail return to the community within 6 months [4]. While there is increasing interest in understanding and improving the health of criminal justice-involved populations [7, 8], few jail health studies focus on older adults.

Understanding the health and healthcare utilization patterns of older adults cycling in and out of jail is critical in developing cost-efficient care models that meet their needs across the healthcare continuum and reducing costly acute care utilization. Among older adults in general, emergency department (ED) use is often a marker for unmet physical, social, and psychological symptom control, and results in high healthcare costs [9–12]. A study of older jail inmates found that over half (56%) reported using the ED in the 3 months prior to their arrest [13]. Health and health-related factors common in older jail inmates (e.g., multimorbidity, functional impairment, distressing symptoms, and homelessness) are associated with ED use in community-dwelling older adults [2, 3, 13–19]. In addition, ED use in the short period following release from jail or prison is common among persons of all ages [20,21]. However, studies have not described the frequency or unique drivers of ED use among criminal justice-involved older adults.

Evidence from incarceration-to-community transitional care programs has shown promise for improving the health of criminal justice-involved populations [22, 23], including the potential to prevent unnecessary ED use [24–28]. Yet, little longitudinal research with this medically vulnerable population of older adults has been conducted and no such clinical programs have been developed to specifically meet their needs. An important first step in developing in-jail and transitional care models for these individuals is to understand the frequency of their ED use following incarceration and to identify the baseline factors associated with such use. Therefore, this study demonstrates methods for conducting longitudinal research with this population, describes the frequency of 6-month ED use following jail incarceration in a cohort of older adults, and assesses the baseline medical, geriatric, and behavioral health factors associated with that use.

Methods

Study Design and Sample

This longitudinal cohort study enrolled older adults (age 55 or older) in an urban county jail between March and August 2015 to explore the prevalence of and outcomes associated with symptom burden in multiple domains (i.e., physical, psychological, spiritual), chronic geriatric conditions, and chronic health conditions in this understudied population. To do so, we conducted monthly check-in and follow-up interviews for 6 months from the baseline interview. Relevant socio-demographic, social, behavioral health, and healthcare utilization factors were also explored. Consistent with other studies, age 55 was used to define “older” adults because of the disproportionately high rates of early-onset multimorbidity and disability that are common in criminal justice-involved populations [2–5].

Study eligibility included having been incarcerated for at least 48 h, being deemed not to pose a safety risk by the sheriff’s deputy on duty, and speaking English or Spanish. The 48-h requirement was used because jail inmates are often in transit or have court appearances within 48 h of arrest and are therefore not available to participate in a research study. Research consent was obtained using a teach-to-goal method, an approach to achieving informed consent in studies that enroll older adults with low literacy [29, 30]. Native-speaking interviewers read questionnaires to participants in private interview rooms, and responses were transcribed by the interviewer.

To enhance retention, all participants received a monthly “check-in” appointment. Interviews conducted at months 1, 3, and 6 from baseline were identical to the baseline interview. Check-ins were conducted at months 2 and 5 from the baseline interview and included brief questions about healthcare utilization since the participant’s last contact with the study. All participants who completed the baseline and 6-month interviews were considered to have completed the study even if they did not complete every monthly check-in or follow-up interview.

Community-based interviews (following release from jail) were completed in a private university-affiliated clinical research office in the central urban neighborhood to which many participants returned following their release. For those who were not released or who were re-incarcerated during the study, interviews were conducted in a private room in the jail. Consistent with federal regulations governing human subject research involving prisoners and relevant ethical considerations [31], participants received $20 per completed interview. For jail-based interviews, the $20 was placed in the participant’s jail canteen account and could be used in jail or received as cash upon release. This study was approved by the Human Research Protection Program at the University of California, San Francisco.

Measures

Emergency Department Use

This study’s primary outcome was 6-month community ED use, defined as an answer of “Yes” to the question, “Since we last interviewed you, did you visit a hospital emergency room?” during any of the monthly check-in or follow-up interviews. We also assessed hospitalization (“Did you stay overnight in the hospital?”) and clinic visits (“Did you receive healthcare from a community clinic?”) over the 6-month period. It was possible for participants to use the ED or be hospitalized while in jail, for example, in the case of a fracture resulting from a fall. Self-reports of ED use, hospitalization, and clinic use have been validated among the previously incarcerated and those experiencing homelessness [32, 33]. Deaths occurring over the 6-month follow-up period were coded as having used the ED, and study involvement was censored at the time of death. Participants who missed a monthly follow-up or check-in interview were prompted by interviewers at their next study contact to remember when their last study contact took place and report any ED visits or hospitalizations since that time.

Socio-demographics

Self-reported baseline socio-demographics included age, race/ethnicity, gender, income, and education level. Annual income was categorized as above or below $15,000 because this is the approximate eligibility criterion for receiving income-related Medicaid (133% below the federal poverty line) [33]. Baseline homelessness was defined as spending at least one night outside or in a homeless shelter within 30 days prior to arrest [34].

Medical and Behavioral Health

Baseline chronic conditions were assessed using a combination of jail medical record review and self-report via validated questions from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) [35]. Self-report of medical conditions is well-validated in older populations and among the homeless [32, 36]. Jail medical record review was used to increase detection of diagnoses for those participants who do not know their medical conditions. Serious mental illness was defined using the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ definition (any major depressive, mania, or psychotic disorder) and was also determined using a combination of self-report and jail medical record review [37]. Drug use was determined using the validated Drug Abuse Screening Test-10 (DAST-10) and defined as any “moderate,” “substantial,” or “severe” drug use [38]. Because the DAST-10 does not assess specific drug use, affirmative responses describe any type of use that the participant feels significant enough to report (including even cannabis use). Problem alcohol use was defined as a positive screen for “hazardous drinking” or having an “active alcohol use disorder” using the three-item Modified Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C) [39].

Geriatric Conditions

Baseline multimorbidity (defined as having two or more chronic medical conditions) and functional impairment (reporting difficulty with one or more activity of daily living [ADL] including dressing, bathing, eating, transferring, and toileting) were measured because of their association among older adults with increased risk of acute care utilization [9,10,20]. Additional geriatric factors were also assessed at baseline including a recent fall (self-report of a fall in the last month), mobility impairment (requiring a mobility-assistive device [cane, walker, or wheelchair]), incontinence (a response of “yes” to the question, “In the last month, have you lost any urine beyond your control?”), and being very concerned about “staying safe” after release from jail (8 or higher on a scale of 1–10).

Symptoms

Symptoms (e.g., pain, anxiety, shortness of breath) are common risk factors for ED use in community-dwelling older adults [10, 13]. We assessed pain at baseline using the brief pain inventory (any pain in the last week beyond “minor headaches, sprains, or toothaches”). We assessed other baseline physical symptoms using the validated Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (MSAS), which has been used with vulnerable populations, including those with HIV, substance dependence, and mental illness [40, 41].

Additional forms of distress were also assessed at baseline, including psychological distress (“depressive symptoms” defined as a positive score on the PHQ-2 and/or “anxiety symptoms” defined as a positive score on the GAD-2 [42]), loneliness (one or more positive responses on the validated three-item loneliness scale [43]), and existential distress (reporting that any one of the ten measures of distress in the patient dignity inventory [44] constituted a “major” or “overwhelming” problem). The patient dignity inventory is a 25-item questionnaire developed to inform the clinical provision of palliative care for seriously ill patients on the part of health providers, social workers, pastoral care providers, and others. As such, it is descriptive and not a validated screening tool. This study includes ten items from the patient dignity inventory that we believed would be most relevant outside the context of serious illness. Based on prior work showing the high prevalence of unique forms of existential distress among older prisoners [45–47], we also assessed two additional measures: “Fear of dying in jail or prison instead of as a free person,” and “Feeling like you have missed out on things or relationships in life because of alcohol or substance abuse.”

Analysis

Baseline participant demographics, health, behavioral health, and health-related social factors were analyzed using descriptive statistics. We used chi-square tests to determine the association of baseline sociodemographics, chronic health conditions, geriatric conditions, distressing symptoms, behavioral health, and health-related social factors with any ED use over the 6-month study period. Analyses were performed using Stata, version 12 software (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture [48].

Results

Participant Characteristics

During the study period, 158 adults were arrested and detained for 48 h or more and met eligibility criteria. Of these, 13 (8%) were released prior to being contacted and 15 (10%) declined to participate, resulting in 130 (82%) recruited to the study. Of these 130 participants, 5 (3.8%) were excluded: 4 could not provide informed consent via the teach-to-goal process and 1 violated the study protocol during the baseline interview and was withdrawn from the study. This resulted in the enrollment of 125 participants. During the 6-month follow-up period, 5 (4%) were transferred to state prison and could not continue with the study, 3 (2.4%) left the jurisdiction and could not come to the study center for an interview, and 16 (12%) were lost to follow-up. This resulted in a sample size of 101 (87%) participants who either completed the study (99) or died (2) by the time of their 6-month interview. Of 606 potential monthly check-in or follow-up interviews to report healthcare utilization between study contacts for this cohort, participants completed 508 (84%). All participants completed at least two contacts, and 88 (87%) completed three or more of six possible monthly check-in or follow-up contacts. Nearly all (93 and 92%) participants were released to the community during their participation in the study.

Socio-demographics

The mean age of participants was 60 years (range 55–87). Most were male (93%) and black (65%). The majority (85%) had annual incomes below the Medicaid eligibility cutoff (< $15,000). More than half (54%) had experienced recent homelessness.

Medical and Behavioral Health

Medical conditions were common among participants, including hypertension (62%), hepatitis C (48%), and arthritis (43%) (Table 1). Overall, 44% had a serious mental illness. Drug use was endorsed by 69% and problem alcohol use by 40%.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and factors associated with 6-month ED use in older jail adults

| Independent predictors | Overall (N = 101) | No ED use (N = 55) | ED use at 6 months (N = 46) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-demographics | ||||

| Age (years) mean ± SD | 60.25 ± 4.8 | 60.1 ± 5.3 | 60.4 ± 4.3 | 0.74 |

| Female, N (%) | 7 (7%) | 4 (7%) | 3 (7%) | 1 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Black | 66 (65%) | 36 (65%) | 30 (65%) | 0.28 |

| White | 20 (20%) | 12 (22%) | 8 (17%) | |

| Asian | 3 (3%) | 3 (5%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Latino | 8 (8%) | 3 (5%) | 5 (11%) | |

| Other | 4 (4%) | 1 (2%) | 3 (7%) | |

| Annual income < $15,000 | 86 (85%) | 46 (84%) | 40 (87%) | 0.64 |

| Community clinic visit | 39 (39%) | 15 (27%) | 24 (52%) | 0.01 |

| Medical/behavioral health | ||||

| Recent homelessnessa | 54 (54%) | 32 (58%) | 22 (49%) | 0.35 |

| Diabetes | 16 (16%) | 8 (15%) | 8 (18%) | 0.66 |

| Hypertension | 63 (62%) | 28 (51%) | 35 (76%) | 0.01 |

| Chronic lung disease | 19 (19%) | 7 (13%) | 12 (26%) | 0.09 |

| Cardiac diseaseb | 12 (12%) | 5 (9%) | 7 (15%) | 0.36 |

| Congestive heart failure | 5 (5%) | 1 (2%) | 4 (9%) | 0.17 |

| Hepatitis C | 48 (48%) | 20 (20%) | 28 (28%) | 0.01 |

| HIV/AIDS | 8 (8%) | 3 (6%) | 5 (11%) | 0.47 |

| Cancer (not skin) | 3 (3%) | 1 (2%) | 2 (4%) | 0.59 |

| Stroke | 7 (7%) | 4 (7%) | 3 (7%) | 1 |

| Arthritis | 43 (43%) | 24 (44%) | 19 (42%) | 0.89 |

| Serious mental illnessc | 44 (44%) | 20 (36%) | 24 (52%) | 0.11 |

| Drug used | 70 (69%) | 36 (65%) | 34 (74%) | 0.36 |

| Problem alcohol usee | 40 (40%) | 23 (42%) | 17 (37%) | 0.62 |

| Geriatric Conditions | ||||

| Multimorbidityf | 62 (61%) | 27 (49%) | 35 (76%) | 0.01 |

| 1+ ADL impairmentg | 58 (57%) | 26 (47%) | 32 (70%) | 0.02 |

| Fallsh | 33 (33%) | 13 (24%) | 20 (43%) | 0.03 |

| Mobility Impairmenti | 47 (47%) | 17 (31%) | 30 (65%) | < 0.001 |

| Incontinencej | 26 (26%) | 10 (18%) | 16 (36%) | 0.049 |

| Very concerned about “staying safe”k | 39 (39%) | 15 (27%) | 24 (52%) | 0.01 |

| Symptoms | ||||

| Painl | 52 (52%) | 20 (36%) | 32 (71%) | < 0.001 |

| Depressive symptomsm | 24 (24%) | 12 (22%) | 12 (26%) | 0.62 |

| Anxious symptomsn | 30 (30%) | 16 (29%) | 14 (30%) | 0.88 |

| Lonelinesso | 46 (46%) | 20 (36%) | 26 (57%) | 0.04 |

| Existential distressp | 55 (54%) | 28 (51%) | 27 (59%) | 0.43 |

aSpending one or more nights on the street or in a homeless shelter in the 30 days prior to incarceration

bHeart attack, coronary disease, or angina

cDefined as any major depressive, mania, or psychotic disorder using the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ definition

dDefined as any “moderate,” “substantial,” or “severe” drug use using the validated Drug Abuse Screening Test-10 (DAST-10)

eDefined as a positive screen for “hazardous drinking” or having an “active alcohol use disorder” using the three-item Modified Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C)

fTwo or more chronic medical conditions

gSelf-report of difficulty with one or more activity of daily living [ADL] including dressing, bathing, eating, transferring, and toileting

hDefined by self-report of a fall in the last month

iDefined as requiring a mobility-assistive device [cane, walker, or wheelchair]

jA response of “yes” to the question, “In the last month, have you lost any urine beyond your control?”

kVery concerned defined as 8 or greater on a ten-point scale

lAssessed pain using the brief pain inventory

mDefined as a positive score on the PHQ-2

nDefined as a positive score on the GAD-2

oOne or more positive responses on the validated three-item loneliness scale

pAny one of the ten measures of distress in the patient dignity inventory constituted a “major” or “overwhelming” problem

Geriatric Conditions

Over half of participants experienced multimorbidity (61%), and 57% reported one or more ADL impairment. A fall in the past month was experienced by 33%, and 47% required the use of assistive devices for ambulation. One fourth (26%) reported incontinence. Thirty-nine percent reported being very concerned about their safety following release from jail. Loneliness was endorsed by 46% of participants.

Symptoms

Many participants reported symptomatic distress: 52% experienced pain, and 46% reported at least one non-pain distressing physical symptom, with difficulty in sleeping (14%), itching (10%), lack of energy (8%), and shortness of breath (8%) among the most common. Nearly one in four participants (24%) had symptoms of depression and 30% of anxiety while 54% reported one or more symptom of existential distress including, most commonly, “fear of dying in jail rather than as a free person” (25%), and a feeling that they had “missed out on things or relationships in life because of alcohol or substance abuse” (31%).

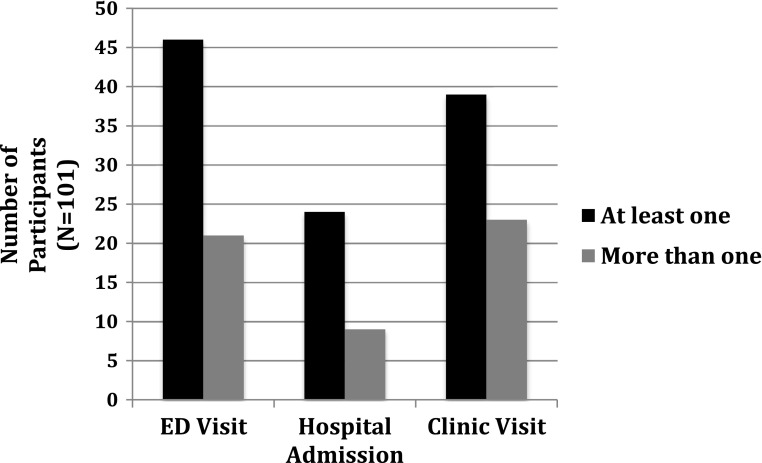

Emergency Department Use

At 6 months, 46 (46%) participants had used the ED at least once, including 2 of 8 (25 and 4% of all ED users) participants who remained in jail throughout their study participation, and 21% visited multiple times. During the same time period, 39 (42%) of the 93 participants who were released to the community during the study reported visiting a community clinic (Fig. 1). In bivariate analyses, those with one or more ED visit were more likely to have a diagnosis of hepatitis C virus (HCV) (28 vs. 20%, p = 0.01) or hypertension (76 vs. 51%, p = 0.01) and report distressing pain (71 vs. 36%, p < 0.001). They were also more likely to report geriatric conditions, including functional impairment (70 vs. 47%, p = 0.02), a recent fall (43 vs. 24%, p = 0.03), mobility impairment (65 vs. 31%, p < 0.001), multimorbidity (76 vs. 49%, p = 0.01), incontinence (36 vs. 18%, p = 0.05), loneliness (57 vs. 36%, p = 0.04), and safety concerns (52 vs. 27%, p = 0.01) (Table 1). Participants who visited the ED were more likely to report visiting a community clinic in the same time period compared to those who did not visit the ED (52 vs. 27%, p = 0.01).

Fig. 1.

Healthcare utilization outcomes for older jail adults at 6 months. Nearly half (46%) of older adults aged 55 or over who were incarcerated in a county jail reported visiting the emergency department within 6 months of their incarceration. One in five (21%) visited multiple times. In the same time period, 42% of the 93 participants who were released to the community during the study period reported visiting a community clinic.

Discussion

In this study of ED use among older jail inmates with an average age of 60, we found a rate of 6-month ED use (46%) similar to that found among older adults in the last month of life (51%) [49] and more than double the rate of 1-year ED use (19.1%) found in a nationally representative sample with a similar average age (59.6 years) [50] and among all Americans 65 years or older (22%) according to the Centers for Disease Control [51]. This finding supports other studies showing that criminal justice-involved individuals are at high risk for post-release ED use. For example, an intervention study of adults with an average age of 43 years, who were transitioning to the community from state prison (where they would have served sentences of at least 1 year), found a 1-year ED use rate of 39% for those in the control group [22]. We also found that select chronic conditions, multiple geriatric conditions, pain, and loneliness were each common and associated with 6-month ED use. The significant association of many geriatric conditions with ED use in this study (e.g., incontinence, loneliness) reflects the fundamental impact that these same syndromes have been shown to have on health and healthcare utilization among older adults in many other studies [52–54]. This study adds support to those findings and suggests that despite a relatively young average age, geriatric conditions among older adults in jail are also indicators of poor overall health and healthcare utilization. Taken together, these results suggest that a multifaceted, interdisciplinary approach to care—rather than attention to one specific disease or area of need—is required to address the healthcare needs and high rates of ED use among the growing number of high-need, high-cost older adults cycling in and out of jails [55].

These findings also underscore the importance of assessing older adults in jail for geriatric conditions even at relatively young ages. Participants with an average age of 60 experienced multimorbidity, pain, and functional impairment at rates similar to those found in community-dwelling adults with a median age of 75 [56]. Geriatric conditions were common and represented the majority of health-related conditions associated with 6-month ED use. Participants also reported a high burden of non-pain symptoms across multiple domains, including existential distress, loneliness, depression, and anxiety. The high proportion of participants reporting concern for their post-release safety further underscores the complex health-related challenges that they face, as neighborhood safety, for example, is associated with functional decline in older adults [57]. Taken together, these findings point to a chronically ill and functionally impaired population that is often managing distressing symptoms with limited financial or social support and reinforce the notion that older adults in the criminal justice system in their 50s should be considered “geriatric” from a medical perspective [2–5].

This study found that pain among older jail inmates is associated with future ED use just as it is among non-incarcerated older adults [13, 14]. This highlights a challenge in jails, where pharmacological treatment of pain may be complicated by concerns about diversion and abuse [14, 58]. The association between pain and future ED use suggests a pressing need for improved approaches to addressing pain in this population—perhaps through expansion of access to non-pharmacological treatment or improved prescribing guidelines for patients with complex chronic disease and a concurrent history of substance use disorder. Programs that proactively connect inmates to appropriate pain management resources upon release may also help reduce this population’s reliance on emergency departments for pain management [14].

This study also demonstrated an association between two chronic health conditions—HCV and hypertension—and ED use. The association between HCV and ED use emphasizes the urgent need for a global response to HCV by correctional health systems [59–61]. It is estimated that up to 40% of US prisoners are infected with HCV [62]. The Center for Disease Control recommends universal testing of older adults born between 1945 and 1965 [59, 63], a recommendation that correctional health systems should heed as the number of incarcerated older adults continues to grow [59, 64]. This study adds evidence to support calls for enhanced attention to the healthcare needs of patients with HCV in jails and during their community reentry. In the case of hypertension, while it is not likely that hypertension led to ED use, the presence of a diagnosis of hypertension among ED users may suggest that this population is accessing health care (enough to be diagnosed as hypertensive). Indeed, participants with ED use were significantly more likely to visit community clinics than those who did not visit an ED. This could suggest that much of the ED use observed in this study would not have been averted through greater access to community clinics. As such, the existence of a strong clinic safety network, as currently exists in San Francisco [65], and expanded Medicaid enrollment, as is promised by the Affordable Care Act, may be insufficient to reduce ED use and improve health outcomes in this population absent targeted interventions that engage patients in wrap-around programs designed to meet their social, behavioral, and healthcare needs concomitantly.

There are several limitations to consider when interpreting these results. This study was conducted in one urban jail system with a relatively low incarceration rate (172.6 per 100,000 adults in San Francisco compared to the average for 58 California counties of 247.1), which may limit its generalizability. However, since this community uses incarceration more sparingly than many others and offers access to a robust clinic network and universal insurance to low-income patients in need of preventive or non-emergency acute care, the high rates of post-jail ED use found in this study likely underestimate rates occurring in other communities. Similarly, we excluded a likely substantial number of older adults who left jail within 48 h of their incarceration, most of them because they were ordered released at their first court hearing or were able to post monetary bail. However, the ultimate aim of this study is to better understand the healthcare needs and utilization patterns of the growing number of older adults relying on jails and community safety-net health systems for their care. As a result, we believe the 48-h eligibility criterion resulted in a more representative sample than had enrollment into the study occurred, for example, within hours of incarceration. In addition, measures of existential distress in this study have not been validated outside of a palliative care setting. However, the high number of older adults experiencing ED use concurrent with chronic illness, multiple geriatric conditions, and loneliness suggests that existential distress is an appropriate domain of inquiry in this and future research investigating the needs of this population. Last, this study, the first of its kind to enroll and follow older adults in jail and following their release, had a relatively small sample size, limiting our ability to assess confounding factors. However, our findings describe a high prevalence of co-occurring medical, geriatric, symptomatic, and social vulnerabilities in this population alongside a high rate of ED use in an understudied population. The findings from this exploratory study thus underscore the need for a multifaceted care model to meet the complex needs of this population, for future research to better understand the complex relationships between health domains and health care utilization in this population, and to help target emerging models of care.

Overall, this study suggests that jail is an important healthcare site for the routine assessment of geriatric conditions among individuals age 55 or older and an important site to target efforts to reduce ED use in an understudied population of high utilizers. Results of geriatric assessments could then guide services and care during incarceration and inform planning for transitions to the community. Integrated care models that incorporate symptom management and geriatric care, such as the home-based GRACE program [66], have demonstrated cost savings and improved health outcomes in medically vulnerable low-income older adults outside of the criminal justice system. Such models, appropriately adapted for the high rate of homelessness in this population, may also improve outcomes for older adults in correctional institutions, nearly all of whom will eventually be returning to the community [67]. Because physical, social, and psychological symptoms are complex, particularly in the presence of multimorbidity and multiple geriatric conditions, future research with larger studies should explore interactions between relevant factors, for example, to assess how loneliness might mediate the role that physical symptoms play in these older adults’ ED use or how injection drug use mediates the connection between HCV and ED use. This study is the first to describe model methods for enrolling and following this understudied population in larger future studies. As communities increasingly invest in services for persons returning from jail, this study underscores the importance of developing jail and transitional care programs specifically targeted to meet the health-related needs of the growing population of criminal justice-involved older adults.

Acknowledgements

This manuscript was supported by a pilot grant from the National Palliative Care Research Center, the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), Department of Medicine; the National Institute on Aging (3P30AG044281-02S1; K23AG033102); and Tideswell at UCSF. The sponsors did not have any role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collections, analysis, or preparation of the paper. The findings in this study do not necessarily reflect the official policies of the city and county of San Francisco, nor does mention of the city and county of San Francisco necessarily imply its endorsement.

Author Contributions

All those who contributed to the manuscript meet authorship criteria and are listed as authors on the title page.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

This study was approved by the Human Research Protection Program at the University of California, San Francisco.

Prior Presentations

This paper was accepted for poster presentation at the American Academy Hospice and Palliative Medicine national conference in Chicago, IL, in March 2016.

References

- 1.Snyder HN, Mulako-Wangota J. Bureau of Justice statistics. (National estimates, annual tables, offense by age). Generated using the arrest data analysis tool at https://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=datool&surl=/arrests/index.cfm. Last accessed 22 Aug 2017.

- 2.Binswanger IA, Krueger PM, Steiner JF. Prevalence of chronic medical conditions among jail and prison inmates in the USA compared with the general population. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009;63(11):912–919. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.090662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loeb SJ, Steffensmeier D, Lawrence F. Comparing incarcerated and community-dwelling older men’s health. West J Nurs Res. 2008;30(2):234–249. doi: 10.1177/0193945907302981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams BA, McGuire J, Lindsay RG, et al. Coming home: health status and homelessness risk of older pre-release prisoners. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(10):1038–1044. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1416-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Binswanger IA, Stern MF, Deyo RA, et al. Release from prison—a high risk of death for former inmates. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(2):157–165. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa064115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Subramanian R, et al. Incarceration’s front door: the misuse of jail in America. New York, NY: Vera Institute of Justice, 2015. Available online at: https://storage.googleapis.com/vera-web-assets/downloads/Publications/incarcerations-front-door-the-misuse-of-jails-in-america/legacy_downloads/incarcerations-front-door-report_02.pdf. Last accessed 22 Aug 2017.

- 7.Rich JD, Chandler R, Williams BA, et al. How health care reform can transform the health of criminal justice-involved individuals. Health Aff Proj Hope. 2014;33(3):462–467. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Health and incarceration: a workshop summary. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2013. http://www.nap.edu/catalog/18372. Accessed 4 Aug 2016. [PubMed]

- 9.Liu B, Taylor DM, Ling SL-Y, MacGibbon P. Non-medical needs of older patients in the emergency department. Australas J Ageing. 2016; 10.1111/ajag.12265. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Gruneir A, Silver MJ, Rochon PA. Emergency department use by older adults: a literature review on trends, appropriateness, and consequences of unmet health care needs. Med Care Res Rev MCRR. 2011;68(2):131–155. doi: 10.1177/1077558710379422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Samaras N, Chevalley T, Samaras D, Gold G. Older patients in the emergency department: a review. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56(3):261–269. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahalt C, Trestman RL, Rich JD, Greifinger RB, Williams BA. Paying the price: the pressing need for quality, cost, and outcomes data to improve correctional health care for older prisoners. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(11):2013–2019. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chodos AH, Ahalt C, Cenzer IS, Myers J, Goldenson J, Williams BA. Older jail inmates and community acute care use. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(9):1728–1733. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams BA, Ahalt C, Stijacic-Cenzer I, Smith AK, Goldenson J, Ritchie CS. Pain behind bars: the epidemiology of pain in older jail inmates in a county jail. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(12):1336–1343. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2014.0160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Handtke V, Wolff H, Williams BA. The pains of imprisonment: challenging aspects of pain management in correctional settings. Pain Manag. 2016;6(2):133–136. doi: 10.2217/pmt.15.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams BA, Lindquist K, Hill T, et al. Caregiving behind bars: correctional officer reports of disability in geriatric prisoners. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(7):1286–1292. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams BA, Lindquist K, Sudore RL, Strupp HM, Willmott DJ, Walter LC. Being old and doing time: functional impairment and adverse experiences of geriatric female prisoners. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(4):702–707. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Noonan M, Rohloff H, Ginder S. Mortality in local jails and state prisons, 2000–2013 Statistical Tables. U.S. Department of Justice. Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2015. http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/mljsp0013st.pdf. Accessed 11 Apr 2016.

- 19.Bolano M, Ahalt C, Ritchie C, Stijacic Cenzer I, Williams B. Detained and distressed: persistent distressing symptoms in a population of older jail inmates. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64:2349–2355. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frank JW, Andrews CM, Green TC, Samuels AM, Trinh TT, Friedmann PD. Emergency department utilization among recently released prisoners: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Emerg Med. 2013;13:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-227X-13-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frank JW, Linder JA, Becker WC, Fiellin DA, Wang EA. Increased hospital and emergency department utilization by individuals with recent criminal justice involvement: results of a national survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(9):1226–1233. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2877-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang EA, Hong CS, Shavit S, Sanders R, Kessell E, Kushel MB. Engaging individuals recently released from prison into primary care: a randomized trial. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(9):e22–e29. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teixeira PA, Jordan AO, Zaller N, Shah D, Venters H. Health outcomes for HIV-infected persons released from the New York City jail system with a transitional care-coordination plan. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(2):351–357. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freudenberg N. Jails, prisons, and the health of urban populations: a review of the impact of the correctional system on community health. J Urban Health Bull N Y Acad Med. 2001;78(2):214–235. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.2.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hammett T, Roberts C, Kennedy S. Health-related issues in prisoner reentry. Crime Delinq. 2001;47:290–409. doi: 10.1177/0011128701047003006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williams B, Abraldes R. Growing older: challenges of prison and reentry for the aging population. In: Greifinger RB, editor. Public Health behind Bars. New York: Springer; 2007. pp. 56–72. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Freudenberg N, Daniels J, Crum M, Perkins T, Richie BE. Coming home from jail: the social and health consequences of community reentry for women, male adolescents, and their families and communities. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(9 Suppl):S191–S202. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.98.Supplement_1.S191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lincoln T, Kennedy S, Tuthill R, Roberts C, Conklin TJ, Hammett TM. Facilitators and barriers to continuing healthcare after jail: a community-integrated program. J Ambul Care Manage. 2006;29(1):2–16. doi: 10.1097/00004479-200601000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sudore RL, Landefeld CS, Williams BA, Barnes DE, Lindquist K, Schillinger D. Use of a modified informed consent process among vulnerable patients: a descriptive study. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(8):867–873. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00535.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Quick guide to health literacy. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; 2016. http://health.gov/communication/literacy/quickguide/quickguide.pdf. Accessed 11 Apr 2016.

- 31.Hanson R, Letourneau E, Olver M, Miner M. Incentives for offender research participation are both ethical and practical. Crim Justice Behav. 2012;39:1391–1404. doi: 10.1177/0093854812449217. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maisto SA, Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Corroboration of drug abusers’ self-reports through the use of multiple data sources. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1982;9(3):301–308. doi: 10.3109/00952998209002632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hwang SW, Chambers C, Katic M. Accuracy of self-reported health care use in a population-based sample of homeless adults. Health Serv Res. 2016;51(1):282–301. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marquez M. Homeless Emergency Assistance and Rapid Transition to Housing (HEARTH): defining “homeless” final rule. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development; 2011. https://www.hudexchange.info/resources/documents/HEARTH_HomelessDefinition_FinalRule.pdf. Accessed 11 Apr 2016.

- 35.Growing older in America: health and retirement study: participant lifestyle questionnaire 2012. National Institute on Aging, National Institues of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2012. http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/modules/meta/2012/core/qnaire/online/HRS2012_SAQ_Final.pdf. Accessed 11 Apr 2016.

- 36.Bush TL, Miller SR, Golden AL, Hale WE. Self-report and medical record report agreement of selected medical conditions in the elderly. Am J Public Health. 1989;79(11):1554–1556. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.79.11.1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.James DJ, Glaze LE. Mental health problems of prison and jail inmates. Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report; 2006. http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/mhppji.pdf. Accessed 11 Apr 2016.

- 38.Skinner HA. The drug abuse screening test. Addict Behav. 1982;7(4):363–371. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(82)90005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(16):1789–1795. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Portenoy RK, Thaler HT, Kornblith AB, et al. The Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale: an instrument for the evaluation of symptom prevalence, characteristics and distress. Eur J Cancer Oxf Engl 1990. 1994;30A(9):1326–1336. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(94)90182-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Merlin JS, Cen L, Praestgaard A, et al. Pain and physical and psychological symptoms in ambulatory HIV patients in the current treatment era. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2012;43(3):638–645. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Löwe B. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ-4. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(6):613–621. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.6.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Perissinotto CM, Stijacic Cenzer I, Covinsky KE. Loneliness in older persons: a predictor of functional decline and death. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(14):1078–1083. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chochinov HM, Hassard T, McClement S, et al. The patient dignity inventory: a novel way of measuring dignity-related distress in palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2008;36(6):559–571. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vanhooren S, Leijssen M, Dezutter J. Loss of meaning as a predictor of distress in prison. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol. 2015; 10.1177/0306624X15621984. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Marlow E. The impact of health care access on the community reintegration of male parolees. In: Presentation: 42nd annual communicating nursing research conference. Salt Lake City: Western Institute of Nursing; 2008.

- 47.Adler F, Mueller G, Laufer W. Criminology and the criminal justice system. Chapter 18: A research focus on corrections in criminology and the criminal justice system. In: 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2006.

- 48.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smith AK, McCarthy E, Weber E, et al. Half of older Americans seen in emergency department in last month of life; most admitted to hospital, and many die there. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31(6):1277–1285. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brown RT, Kiely DK, Bharel M, Mitchell SL. Geriatric syndromes in older homeless adults. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(1):16–22. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1848-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2016: With chartbook on long-term trends in health. Table 74: emergency departments visits within the past 12 months among adults aged 18 and over, by selected characteristics: United States, selected years 1997-2015. Hyattsville, Maryland. 2017. Available online from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/2016/074.pdf. Last accessed 22 Aug 2017.

- 52.Lee PG, Cigolle C, Blaum C. The co-occurrence of chronic diseases and geriatric syndromes: the health and retirement study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:511–516. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Buurman BM, Hoogerduijn JG, de Haan RJ, Abu-Hanna A, Lagaay AM, Verhaar HJ, et al. Geriatric conditions in acutely hospitalized older patients: prevalence and one-year survival and functional decline. PLoS One. 2011;6(11):e26951. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Morris V, Wagg A. Lower urinary tract symptoms, incontinence and falls in elderly people: time for an intervention study. Int J Clin Pract. 2007;61:320–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2006.01174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Blumenthal D, Chernof B, Fulmer T, Lumpkin J, Selberg J. Caring for high-need, high-cost patients—an urgent priority. N Engl J Med. July 2016; 10.1056/NEJMp1608511. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Sawyer P, Bodner EV, Ritchie CS, Allman RM. Pain and pain medication use in community-dwelling older adults. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2006;4(4):316–324. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sun VK, Stijacic Cenzer I, Kao H, Ahalt C, Williams BA. How safe is your neighborhood? Perceived neighborhood safety and functional decline in older adults. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(5):541–547. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1943-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rich JD, Boutwell AE, Shield DC, et al. Attitudes and practices regarding the use of methadone in US state and federal prisons. J Urban Health Bull N Y Acad Med. 2005;82(3):411–419. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rich JD, Allen SA, Williams BA. Responding to hepatitis C through the criminal justice system. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(20):1871–1874. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1311941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Iacomi F, Iannicelli G, Franceschini A, et al. HCV infected prisoners: should they be still considered a difficult to treat population? BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:374. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Spaulding AC, Thomas DL. Screening for HCV infection in jails. JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 2012;307(12):1259–1260. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Varan AK, Mercer DW, Stein MS, Spaulding AC. Hepatitis C seroprevalence among prison inmates since 2001: still high but declining. Public Health Rep Wash DC 1974. 2014;129(2):187–195. doi: 10.1177/003335491412900213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Recommendations for the identification of chronic hepatitis c virus infection among persons born during 1945–1965. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr6104a1.htm. Accessed 1 July 2016. [PubMed]

- 64.Rich JD, Allen SA, Williams BA. The need for higher standards in correctional healthcare to improve public health. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(4):503–507. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-3142-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Finley DS, Brigham T. Creating a network of care: healthy San Francisco connects uninsured residents to a primary care home. Healthc Exec. 2011;26(3):72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Counsell SR, Callahan CM, Buttar AB, Clark DO, Frank KI. Geriatric Resources for Assessment and Care of Elders (GRACE): a new model of primary care for low-income seniors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(7):1136–1141. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Freeman RB. Can we close the revolving door? Recidivism vs. employment of ex-offenders in the U.S. In: Urban Institute Reentry Roundtable, Employment Dimensions of Reentry: Understanding the Nexus between Prisoner Reentry and Work. New York: New York University Law School; 2003.