Abstract

Prison inmates suffer from a heavy burden of physical and mental health problems and have considerable need for healthcare and coverage after prison release. The Affordable Care Act may have increased Medicaid access for some of those who need coverage in Medicaid expansion states, but inmates in non-expansion states still have high need for Medicaid coverage and face unique barriers to enrollment. We sought to explore barriers and facilitators to Medicaid enrollment among prison inmates in a non-expansion state. We conducted qualitative interviews with 20 recently hospitalized male prison inmates who had been approached by a prison social worker due to probable Medicaid eligibility, as determined by the inmates’ financial status, health, and past Medicaid enrollment. Interviews were transcribed verbatim and analyzed using a codebook with both thematic and interpretive codes. Coded interview text was then analyzed to identify predisposing, enabling, and need factors related to participants’ Medicaid enrollment prior to prison and intentions to enroll after release. Study participants’ median age, years incarcerated at the time of the interview, and projected remaining sentence length were 50, 4, and 2 years, respectively. Participants were categorized into three sub-groups based on their self-reported experience with Medicaid: (1) those who never applied for Medicaid before prison (n = 6); (2) those who unsuccessfully attempted to enroll in Medicaid before prison (n = 3); and (3) those who enrolled in Medicaid before prison (n = 11). The six participants who had never applied to Medicaid before their incarceration did not hold strong attitudes about Medicaid and mostly had little need for Medicaid due to being generally healthy or having coverage available from other sources such as the Veteran’s Administration. However, one inmate who had never applied for Medicaid struggled considerably to access mental healthcare due to lapses in employer-based health coverage and attributed his incarceration to this unmet need for treatment. Three inmates with high medical need had their Medicaid applications rejected at least once pre-incarceration, resulting in periods without health coverage that led to worsening health and financial hardship for two of them. Eleven inmates with high medical need enrolled in Medicaid without difficulty prior to their incarceration, largely due to enabling factors in the form of assistance with the application by their local Department of Social Services or Social Security Administration, their mothers, medical providers, or prison personnel during a prior incarceration. Nearly all inmates acknowledged that they would need health coverage after release from prison, and more than half reported that they would need to enroll in Medicaid to gain healthcare coverage following their release. Although more population-based assessments are necessary, our findings suggest that greater assistance with Medicaid enrollment may be a key factor so that people in the criminal justice system who qualify for Medicaid—and other social safety net programs—may gain their rightful access to these benefits. Such access may benefit not only the individuals themselves but also the communities to which they return.

Keywords: Prison, Healthcare, Health coverage, Medicaid, Disability

Introduction

It is well recognized that people in the criminal justice system, as compared to the general population, have a heavier burden of mental health problems, substance use disorders, infectious diseases, and other chronic health conditions [1]. Given this heavy burden of health problems, access to healthcare is increasingly recognized as an important pillar in supporting successful re-entry from correctional settings back into the community. Possible benefits of health insurance coverage and appropriate care utilization for people released from correctional environments include supporting their own health, decreasing the use of emergency care, minimizing medical debt, and—when applicable—lowering the risk of infectious disease transmission.

Studies conducted prior to the implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) suggest that rates of health insurance were low among released prisoners. For example, in a study of released Ohio and Texas prisoners, 68% of men and 58% of women were without health insurance at 8–10 months following their release. The ACA, and in particular, its expansion of Medicaid in 32 states, has been widely recognized as a potentially important mechanism for people involved in the US criminal justice system to gain healthcare coverage when returning to their communities [2–6]. However, with all of the well-deserved discussion around the possible impact of Medicaid expansion for criminal justice-involved populations, much less attention has been given to the health of incarcerated persons with serious medical problems who are living in one of the 18 Medicaid non-expansion states.

In Medicaid non-expansion states, eligibility remains restricted to those who both have severe financial need and qualify as (1) aged, blind, or disabled; (2) pregnant; or (3) are otherwise categorical eligible through programs such as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) which requires having dependents. As a result, millions of those with limited financial means and health problems fall within the Medicaid “gap” in which they are unable to afford private insurance and yet do not qualify for Medicaid [7, 8]. As a result, in non-expansion states, the vast majority of those in the coverage gap are adults without dependent children, and men are more likely to be in the gap than women. In the context of more restricted eligibility criteria in Medicaid non-expansion states, maximizing rates of Medicaid enrollment among those who qualify may be a crucial avenue to healthcare coverage, particularly for criminal justice-involved persons who face significant barriers to accessing public programs and limited access to other sources of coverage. Yet, despite the importance of Medicaid enrollment for those involved with the criminal justice system who qualify for Medicaid, little is known about this population’s experiences enrolling in Medicaid.

To address this gap, we conducted in-depth qualitative interviews with incarcerated men in a non-expansion state who, because of compromised health and low assets, were deemed by prison administrators as likely to qualify for “traditional” Medicaid. We used the “Gelberg-Andersen Model of Health Services Utilization among Vulnerable Populations” as a framework to understand factors affecting respondents’ (1) pre-incarceration Medicaid enrollment and (2) likelihood of enrolling in Medicaid following prison release [9]. In doing so, we also described respondents’ community healthcare experiences and their healthcare coverage from sources other than Medicaid. A greater understanding of these healthcare coverage experiences and intentions can inform resources to strengthen Medicaid enrollment for qualifying incarcerated persons in anticipation of their return to their communities.

Methods

Setting, Recruitment, and Eligibility

As of 2015, there were approximately 1.9 million North Carolinians enrolled in Medicaid, including one in eight NC adults aged less than 65 years. As in other non-expansion states, Medicaid eligibility in North Carolina is based on income level and categorical eligibility: parents of children may qualify for Medicaid if they earn 44% or less of the federal poverty level, and the aged, blind, or disabled must earn no more than 100% of the federal poverty level to qualify for Medicaid [10]. In North Carolina, 79% of those in the coverage gap in 2016 were adults without dependent children, 60% were in a family with at least one employed adult, and 57% were male [8].

The North Carolina prison system operates a program to facilitate Medicaid enrollment for state prisoners experiencing community inpatient hospitalization during their incarceration. We conducted qualitative interviews with male prison inmates who had returned from a community hospitalization and were subsequently approached by a program social worker to assess potential Medicaid eligibility. If the inmate is determined disabled by his local Department of Social Services (DSS) office and successfully enrolled in Medicaid, the federal government’s financial contribution to the inmates’ benefits (based on the federal medical assistance percentage) can be used to retroactively reimburse the prison system for part of the hospitalization expense; however, successful enrollment is generally temporary (lasting less than 1 year) and does not guarantee that benefits will be available upon release. Post-release Medicaid benefits require released inmates to, at the least, activate benefits at their county DSS, and in cases when more than a year has elapsed since their hospitalization, submit a new application. Further details about this program are described elsewhere [11].

The researcher recruiting inmates and conducting the interviews was a licensed professional counselor with 8 years of correctional research experience. Eligibility for study participation included being aged 18–64 years old, housed within the prison’s hospital following an inpatient community hospitalization, and approached by prison social workers to complete a Medicaid application.

All study procedures were approved by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Office of Human Research Ethics and the North Carolina Department of Public Safety’s Human Subjects Review Committee.

Qualitative Interview Guide

We developed semi-structured interview guides informed by (1) a literature review of common barriers to Medicaid enrollment and predictors of healthcare access and utilization and (2) interviews with prison social workers about inmates’ experiences with Medicaid and healthcare outside of prison [11]. Major discussion topics covered in the interview guide were (1) the inmate’s recent community hospitalization and precipitating health conditions; (2) pre-incarceration health problems, healthcare utilization, and healthcare coverage; and (3) attitudes, barriers, and facilitators to accessing healthcare outside of prison. To avoid over-burdening respondents with long interviews, we developed two similar interview guides with similar broad topics (e.g., medical history, experience with Medicaid enrollment before prison) but also some complementary points of emphasis. One guide emphasized social security programs and interaction with prison social workers about Medicaid, and the other emphasized past experience with health insurance prior to incarceration.

The study team met weekly during data collection to discuss emergent themes and add probes to the interview guides to cover new relevant issues.

Codebook Development and Transcript Coding

All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim for data analysis using Dedoose [12]. Our analysis approach was guided by the “Diving In” and “Stepping Back” process outlined by Maietta and Mihas [13]. Four team members, including the interviewer, divided up all of the interviews to read and inserted memos describing major themes and potential interpretations of the text. These memos, along with the interview guide, served to create the foundation for a codebook. We developed three types of codes: (1) structural codes for specific questions from the interview guide and their immediate answers; (2) topical codes for discussion of a specific topic or experience such as “Paying out-of-pocket for healthcare” or “Emergency room visits”; and (3) interpretive codes for text based on concepts such as “Unmet need for healthcare” or “Feelings and attitudes about Medicaid.”

After developing the initial codebook, three team members (CAG, ARM, CMB) used it to code the same two interviews independently and used differences in coding to inform refinement of the codebook for greater clarity and comprehensiveness. After another round of coding and editing, the three team members applied the revised codebook to the remainder of the interviews, with each interview coded by one team member and 25% (n = 5) coded by all three team members to allow for continuous comparison of codes and identification of problems with the codebook and coding application.

Analysis

During the coding process, team members created summaries of main interview topics for each participant (e.g., experience with Medicaid, reason for hospitalization, main health conditions) in a table for ease of reading across or within participants as needed. Four team members examined the interview summaries along with select code reports related to Medicaid enrollment to classify factors according to constructs from the Gelberg-Andersen Model, Health Belief Model, and Theory of Reasoned Action [9, 14, 15]. The relevant constructs identified from each model all seemed to fit conceptually under the three main factors described in the Gelberg-Andersen Model: (a) predisposing: factors that exist before the onset of an illness, such as demographics, social factors, and beliefs; (b) enabling: factors that affect an individual’s ability to secure health services in the community, such as personal, family, and community resources; and (c) need: individual’s actual and perceived health problems. Summaries of these three main factors were created for each participant, and comparisons were made across participants. Similarities clustered within three groups of participants based on their self-reported experiences with Medicaid enrollment prior to this incarceration: (1) never applied, (2) applied but had an application rejected, and (3) enrolled without significant obstacles. We reported results by cluster. For each cluster, we generally described respondents’ predisposing, need, and enabling factors as well as their perspectives on post-release Medicaid enrollment; however, enabling factors were not relevant and therefore not presented for respondents who never enrolled in Medicaid prior to their incarceration.

Results

Study participants consisted of 20 men with a mean age of 50 (range 26–65); 8 identified as White, 7 as Black/African American, 2 as American Indian, and 3 as more than one race (2 American Indian and White, and 1 African American and White) (Table 1). At the time of the interview, inmates had been incarcerated a median of 4 years (range 18 days to 22 years) and were projected to be released from prison in a median of 2 years (range 1 month to 21 years). About a third of participants were expected to be released from prison within 1 year, and a quarter after more than 10 years. At the time of writing this manuscript, three participants had died before their projected release date. Participants reported a history of multiple serious health conditions including heart attack or stroke (n = 5); substance abuse or mental health diagnoses including depression, psychosis, and anxiety disorders (n = 8); epilepsy or seizures (n = 4); paraplegia (n = 3); cirrhosis (n = 3); major injuries, such as from gunshots or car accidents (n = 6); late-stage cancer (n = 2); HIV (n = 2); rheumatoid arthritis (n = 2); and neuropathy (n = 2).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and Medicaid knowledge of total sample and Medicaid history groups

| Total sample (n = 20) | Never applied for Medicaid before prison (n = 6) | Experienced difficulties enrolling in Medicaid before prison (n = 3) | Received Medicaid before prison (n = 11) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (range) | 50 (26–65) | 54 (29–63) | 54 (46–58) | 51 (26–55) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 9 | 4 | 2 | 3 |

| Black | 7 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| American | ||||

| Indian | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Multiple races | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| At least GED or high school graduate | 16 | 5 | 3 | 8 |

| Experienced a prior incarceration | 12 | 4 | 3 | 5 |

Participants were categorized into three sub-groups based on their self-reported experience with Medicaid: (1) those who never applied for Medicaid before prison (n = 6); (2) those who unsuccessfully attempted to enroll in Medicaid before prison (n = 3); (3) and those who had Medicaid before prison (n = 11).

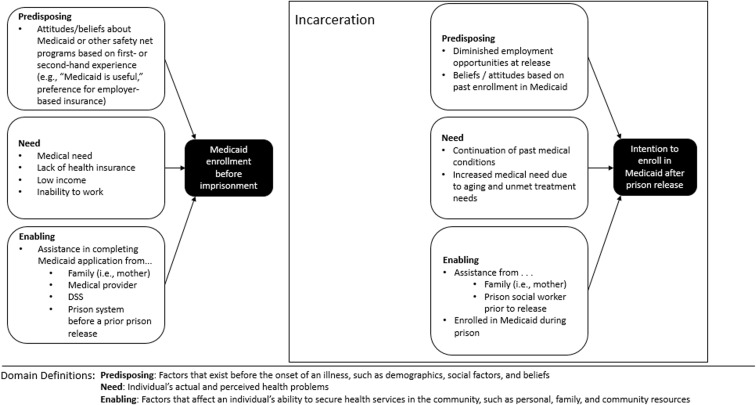

Below, we describe the emergent predisposing, enabling, and need factors described by our participants; common factors are also outlined in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Predisposing, enabling, and need factors related to past and future Medicaid enrollment for recently hospitalized incarcerated persons in a southern prison system

Context and Participant Knowledge of Medicaid Eligibility in North Carolina

Eligibility criteria based on income and disability played a critical role in participants’ history of Medicaid enrollment and likelihood of enrollment post-release, even though eligibility was not well understood by participants. Only about half of participants (n = 11) reported having any basic knowledge about Medicaid, most of whom had been enrolled in Medicaid (n = 8) prior to their incarceration. Five participants reported they had very little or no knowledge of Medicaid, including eligibility criteria, despite having a history of Medicaid enrollment.

Participants Who Never Applied for Medicaid before This Incarceration

The six participants who reported never having applied for Medicaid before prison varied in their past experiences with insurance and healthcare. Two participants reported having had consistent health coverage, one through Medicare which he received through Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) due to disability from a traumatic brain injury, and the other through the Veteran’s Affairs office (VA). Three participants spent significant periods of time being uninsured, with occasional periods of coverage by employer-based plans (n = 2) or, in the case of the youngest participant, his mother’s insurance. One participant reported no history of health coverage.

Never Applied: Predisposing Factors before Prison

For the most part, these six participants did not describe factors or attitudes predisposing them toward Medicaid enrollment before prison. Two perceived minor barriers to Medicaid enrollment which may have led to a negative predisposition toward enrollment: one thought he was too young to enroll (“Well I feel that, as young as I was, too young to apply… The government ain’t going to take care of me. And at the age I am, when I’m able to work, I don’t need physical help. So [Medicaid] was out for me then”), and another stated a friend had difficulties enrolling in Medicaid and his mother had difficulties getting Medicaid to cover aspects of her medical care, concluding “I’d rather work.” Only one participant who received SSDI and Medicare before prison reflected a positive attitude toward Medicaid based on experience receiving another type of government-funded insurance for his children: “I don’t know what Medicaid pays for, but I know NC Choice[insurance program for children of families whose income exceeds Medicaid criteria], it’s a really good insurance because… I think we were paying maybe $5.00 for a visit and $1.00 for prescription drugs.”

Never Applied: Need Factors before Prison

Most participants reported having little need for Medicaid enrollment prior to incarceration. Two participants described being generally healthy before their incarceration and not seeking healthcare frequently; one said “…if your health real good and you feel real good about yourself, you don’t have the money, you’re not just going to go and make bills that you can’t pay.” However, this participant also reported that he had trouble affording yearly checkups and medical care for his dentures without insurance. Two other participants described needing minor healthcare but having it covered by the VA and their mother’s insurance, respectively. One participant had significant medical need due to a brain injury but received SSDI and Medicare and reported receiving “great care” outside of prison.

One participant struggled considerably to access the mental healthcare he needed due to inability to pay during lapses in his employer-based insurance coverage. Although he received SSDI for a short time, he lost it when he returned to work; he also had trouble getting insurance coverage for his pre-existing conditions: “Yeah, there were several times that I didn’t have any insurance, and with pre-existing, when I did get insurance, I’d have to pay in for like two years before I was ever covered.” He even attributes his lapse in insurance and mental health medications for his current incarceration: “I didn’t have the money to go back [to my psychiatrist], so then I ended up getting committed and then ended up getting in trouble with the law…. I figure if Obamacare would’ve went through a year earlier, I wouldn’t be here [in prison].”

Never Applied: Intentions to Enroll in Medicaid after Prison

Participants anticipated their need for healthcare and coverage after release from prison would be higher than their need before prison. One believes that he will need health insurance when he is released because he is getting older and having more health issues, and does not anticipate being able to find a job or afford going to the doctor on his own. “I’m going to need [insurance] real bad…. I really ain’t had too many medical issues over my life, I’ve been in pretty good health. But after I turned 50, everything started turning around. So I’m going to need the insurance now. I’m going to need Medicare or something.” Another was diagnosed with terminal lung cancer in prison and does not think he will be able to work, but intends to return to receiving care at the VA: “If this medical release would come through, I’m lucky, very lucky that I’ve got the VA, and I would probably just go back there. That would be the best thing for me, because I know what to expect there.” The four remaining participants reported that health insurance (one specified Medicaid, and one their Medicare from pre-incarceration) would be useful after release in helping them pay for current medications and treatment.

Participants Who Encountered Obstacles to Medicaid Enrollment before Current Incarceration

Three participants said they tried to enroll in SSI or Medicaid and failed multiple times before their current incarceration. One participant had his SSI application denied twice because “[DSS] didn’t have enough information,” before prison doctors from a previous incarceration assisted with a successful application to help cover care for his kidney problems and liver cancer after a prior release from prison. Another applied unsuccessfully on his own several times to cover care for neuropathy and injuries before he successfully enrolled in SSI and Medicaid with assistance from a local hospital following a stroke. The third participant applied for Medicaid several times to help cover care for multiple chronic conditions, cocaine addiction, and a MRSA bone infection, but was always denied because, as he explained, “…If you had kids you would qualify. For a single white male not working to support himself, there’s really nothing out there.”

Obstacles to Enrollment: Need Factors before Prison

All three participants described significant need for healthcare coverage prior to incarceration. One was employed for 17 years as a truck driver and had employer-based insurance before becoming self-employed and developing health problems he could not pay for, which resulted in inability to work and significant financial loss: “I had a home, a swimming pool, a new Chevrolet pickup; I had to let it all go…. And ended up living in public housing.” Only after having a stroke was he able to start receiving SSI and receive enough money to move out of public housing. The participant who never successfully enrolled in Medicaid had always been self-employed as a contractor and was only periodically able to afford private insurance, resulting in inconsistent treatment for a lifelong cocaine addiction (to which he attributes his current incarceration) and work-related infection (to which he attributes his current disability and amputated toe).

All three participants made statements reflecting concern about worsening health conditions resulting from lack of health insurance. Two stated that they received poor healthcare while they were uninsured, one of whom explained how lack of coverage led to inadequate treatment that ultimately worsened his health condition: “If someone had the finances or was able to commit me into a hospital where I could’ve gotten the six weeks of intravenous Vancomycin… then the [MRSA] problem would’ve ended a long time ago. No one wanted to invest that in me.” Conversely, another participant reported receiving good care even when he was uninsured: “It wasn’t about the money. And [the local hospital] let me know that right quick…. ‘Even if we never get paid—you’re gonna hear from us from time to time, but even if you can’t pay it, we’re not worried about it—we’re worried about you.’”

However, in spite of receiving good healthcare and benefitting from charity programs at local hospitals, this participant also reported having accumulated several thousand dollars in medical debt from his time spent uninsured. The participant who never successfully enrolled also described debt resulting from being uninsured:

I’m financially ruined…. I spent probably 20 days.... in the hospital and they – I’m still getting letters every – you know, I haven’t gotten a letter in a while because I’ve been [in prison] but for creditors coming after me and it’s just destroyed my credit. And it wasn’t stellar to begin with but… they’d laugh at me if I applied for a credit card now…. [the hospital] still sends me bills and quite rudely calls me demanding their money when the bastards gave me [a serious infection] and then refused to treat me for it properly and… still has the gall to call and complain and say they need their money and turn me over to bill collectors and everything else.

Obstacles to Enrollment: Predisposing Factors before Prison

The three participants with obstacles to enrollment mentioned attitudes toward Medicaid that were closely linked to their medical need and their experiences enrolling in and receiving Medicaid. One participant who successfully enrolled in Medicaid after a period without insurance reported that he received poor healthcare when he did not have Medicaid, but that once he enrolled, Medicaid benefits were “100% helpful.” The participant who was never enrolled in Medicaid before his incarceration, on the other hand, harbored negative attitudes toward Medicaid that are reflected in this explanation of why he was successfully enrolled in prison: “I think that’s the only reason [Medicaid accepted my application] is because the state owes another department of the state money… It’s not because they give a [expletive] about [me].”

Obstacles to Enrollment: Enabling Factors before Prison

Two participants had significant enabling factors for Medicaid enrollment in the form of assistance from medical providers in completing an SSI application. After one inmate’s stroke, his local hospital helped him fill out paperwork for disability that was ultimately accepted; it is unclear whether it was the assistance from the hospital or the increased eligibility from the stroke, or both, that resulted in his application being accepted after repeated past denials. Another was released from prison shortly after he was diagnosed with stage 2 lung cancer, and his prison doctors helped him enroll in disability and Medicaid for after release: “They done it in an amazing time, because [DOCTORS’ NAMES] had set me up for getting disability and Medicaid and all that. They took very good care of me…. They got it started… in less than five months.” The participant who never successfully enrolled in Medicaid was encouraged to apply by a medical provider who predicted he would be eligible, but completed the application without assistance and was denied several times: “There’s always a reason why I specifically [was denied] – ‘well, you would qualify but you didn’t make at least $11,600.00 for Obamacare, or you don’t have children, or you this, or you that’.”

Obstacles to Enrollment: Intentions to Enroll in Medicaid after Prison

These participants anticipated their need for healthcare and coverage after release from prison would be high. One stated that he could not work or go to school after release and so would need another source of health coverage. Another stated that when he is released, he assumes he will go to the Social Security office and re-start his disability and Medicare, which is what happened 4 years earlier when he was released from a previous incarceration. The participant who never successfully enrolled in Medicaid expressed doubt that the Medicaid he acquired in prison would continue after release if he applied for himself: “When I get out in June, I’ll have Medicaid until December probably and then right back in the same boat…. I don’t know what the hell I’ll do. Just hope I don’t get sick, I guess, you know?”

Participants Who Enrolled in Medicaid with Minimal Difficulty before Prison

Eleven participants said they enrolled in Medicaid with no failed attempts before their current incarceration. Four were covered by Medicaid, Medicare, and disability before prison; three had both Medicaid and disability; and four had Medicaid only. Most (n = 8) of these participants reported working before receiving Medicaid; however, they had varied experiences with insurance coverage before enrolling in Medicaid. Six participants had a history of employer-based insurance before enrolling in Medicaid, one of whom also received VA benefits.

Two participants spent their adult lives uninsured despite having an employment history before enrolling in Medicaid; one was able to access needed HIV care in spite of being uninsured, but the other often went without needed healthcare. It is unclear whether another two participants worked before enrolling in long-term Medicaid: one of them was uninsured and mostly accessed healthcare through the emergency department before Medicaid enrollment, and the other enrolled in Medicaid as a young adult. Another participant received Medicaid since childhood.

Enrolled without Difficulty: Predisposing Factors before Prison

Three participants made statements reflecting some ambivalence toward accepting Medicaid coverage. Two of these believed that some people enroll in Medicaid who do not really need it, but those who really need Medicaid should be able to get it. One explained:

If I was able to walk and to take care of myself, I wouldn’t never applied for it [Medicaid]. I would try to get a job if it had to be somewhere low until I could get myself up. That’s what I would have chose. But I feel like, being in my condition, I can understand what Medicaid things is. But I feel that some people can get off Medicaid, and Medicaid just still takes care of them.

Similarly, the other said, “There’s been Medicaid if that’s the one I’m thinking about the ones that really need it should of got it, but there was a whole bunch that didn’t need it, but they got it.” A third participant believed he could have gotten private insurance if he needed it and preferred to work rather than receive Medicaid.

Enrolled without Difficulty: Need Factors before Prison

Although two participants described little need for Medicaid enrollment prior to incarceration, including one participant who had Medicaid since childhood, the majority (n = 9) described significant need due to debilitating health conditions, inability to work, difficulty in accessing healthcare, and trouble in paying medical bills.

One explained that he needed health insurance because he could not obtain employment due to difficulties arising both from health issues and his status as a felon: “I couldn’t have a job. I couldn’t get a job to get the money to pay for insurance.” Another participant described how he was often forced to go without basic medical care without insurance: “You would have to have some kind of insurance card or something. So, basically, if I needed help, I would just heal myself.”

Several participants described onset of a serious or debilitating health condition as precipitating the need for Medicaid. One explained: “Yeah I wanted some help…. I can’t afford the high dollar amount. I had a case [of medicine] about that long and about that wide and about that tall.” One needed health insurance only after experiencing an expensive hospitalization for cryptococcal meningitis, and another felt that his health insurance through his employer and family “was just a waste of money” until he started dialysis. Other participants found themselves no longer able to work and receive employer-based insurance due to complications from rheumatoid arthritis, AIDS, and mental health conditions.

Enrolled without Difficulty: Enabling Factors before Prison

All 11 participants had significant enabling factors for Medicaid enrollment in the form of assistance from their local Department of Social Services or Social Security Administration (SSA), their mothers (n = 3), medical providers (n = 2), and prison personnel during a previous incarceration (n = 1).

Those who went to the SSA reported that the office provided what they needed to enroll in Medicaid. One stated he received not only Medicaid but other services as well: “I was introduced to Medicaid when I got out […] of the military. When I went and had to get a Social Security card and all that stuff, my driver’s license. They actually had everything right there at the Social Security department.” One participant applied through SSA with the help of his disability caseworker: “Disability put me on it…. They told me a couple weeks before it started it about a month before I started on it. They told me to go out there fill out for her to see and everything.” Another participant successfully enrolled in Medicaid multiple times through the SSA: “Sometimes when I really couldn’t work, they gave me a temporary Medicaid card through social service. That took care of a lot of things.”

Three participants stated that their mothers took care of their Medicaid application process. One described how his mother stepped in when he lost his job: “I lost my job and my insurance and everything. And mama just went and got help to pay for that”; another mother enrolled her son so that he could access care, “My mother was a big help when she was living. And she had got me Medicaid started so that I could take the Medicaid card and go to her doctor or the emergency room.” The third participant acknowledged that he understood little about the process himself: “My mama got me on Medicaid. I don’t know how. I just all of a sudden was getting a little blue card. I don’t know, it would come through the mail every month. That’s all I know. I don’t know nothing. I don’t know about going to the mental health – I don’t go to the Medicaid building or nothing like that. I mean, I don’t know how she got me on that.”

Two participants received significant help from their medical providers in applying for Medicaid. A healthcare provider signed one participant up for Medicaid while he was in the hospital: “I signed up for it when I was in the hospital when they told me that I was paralyzed. So that’s when one of the healthcare providers at [NAME OF HOSPITAL] come around, and she signed me up for that, and to get me checked, and then all of that stuff, to try to make sure that I was all right.” Another received help from his HIV doctor to apply for Medicaid after he contracted cryptococcal meningitis: “[DOCTOR’S NAME] helped me out and got me on Medicaid and Medicaid went back two years and paid all my medical bills.”

One participant described how a prison case manager from a previous incarceration helped him apply for disability, which in turn helped him apply for Medicaid: “The case manager that I had in [NAME OF PRISON], they applied for [disability] before I got out of prison… And then by applying for disability, you could get Medicaid.” Upon his release from prison, he went to social services to complete his application and quickly enrolled in Medicaid: “Right when I got released, I had to go to the offices and do the – fill everything out and all that. But I had it within a week, I’m pretty sure.”

Enrolled without Difficulty: Intentions to Enroll in Medicaid after Prison

All of the participants who had Medicaid before their current incarceration mentioned factors predisposing them toward Medicaid enrollment after prison. Several stated that the Medicaid enrollment process is relatively easy. Many described perceived benefits of having Medicaid such as access to care and ability to afford medical expenses. One participant felt that he received medical care in a “timely fashion” and “smoothly” while having Medicaid, and that with Medicaid, “They treat you the same as if you had insurance. They don’t treat you no different.” Another mentioned several perceived benefits to having Medicaid, including the opportunity to receive treatment for his Hepatitis C: “When you’re on the street they might say something about the cost but if you got Medicare and Medicaid most doctors out there will figure out a way to get you treated.” One participant explained how Medicaid helps avoid debt for medical expenses by giving recipients access to preventive care: “It allows you an avenue to get the care that you need so that your problems don’t become a $500,000.00 hospital bill because they was ignored, left alone or overlooked until it ended up being a huge problem, and you ended up being in a really bad medical situation where you almost die, and it runs up this huge hospital bill.”

A few participants mentioned negative aspects of Medicaid enrollment, including that Medicaid enrollment limits which providers recipients can see, or does not cover all necessary medical expenses, or denies coverage for experimental treatments for paraplegia. For example, one explained:

they might be a specialist that deals with the stuff that's going on with my nerves. He might be able to fix it because he's really good at it, and he's on the edge of this, that, or the third. He might want to do a surgery or something like this or whatever. But you can't see him because they don't accept Medicaid.

All participants anticipated their need for healthcare and coverage after release from prison would be high. Some participants anticipated that they would need Medicaid after prison until they could get another type of health coverage, such as through employment or Medicare benefits. One stated that he needs Medicaid now but prefers to 1 day have private health insurance:

If I didn’t have my condition, I would want to try to get health insurance. That’s why I’m like, I’ve been wanting to try to work to try to get something. And I still might go. I don’t want to be on Medicaid forever. I want to try to get off of it, get myself together, and be an entrepreneur, and give it to somebody that actually needs it. But right now, I do need it.

However, many acknowledged that they would need Medicaid in the long term due to an inability to work or to needing intensive medical treatments. When asked about how useful health insurance would be after prison, a dialysis patient who had Medicare, Medicaid, and SSI before his incarceration replied “Yeah. I mean, I have to have that. I’m on dialysis. I mean; I would die without any kind of health insurance.”

Almost all (n = 10) mentioned factors that would enable their enrollment in Medicaid after incarceration. Some understood that prison personnel will start the Medicaid application process before they are released from prison, but that they will need to go to social services to complete their enrollment: “I know my social worker, last time I talked to her, that was a couple years ago. But she say when I get out, she’ll get back with me and then would give me a package with everything to take to social service and Social Security place.” Another stated that his mother would need to help him with his Medicaid application again after release. And three participants mentioned that having enrolled in Medicaid either before prison or while in prison should make it easier to get Medicaid after prison. One stated, “I’m pretty sure I can reapply for it [Medicaid] when I get out, and it won’t be no problem getting it then. I mean, it ain’t hard to do, I don’t think. I mean, once I had it, I can always get it again.”

Discussion

Despite the widely acknowledged importance of healthcare for formerly incarcerated persons, few studies have sought to understand the contextual factors that might facilitate or impede Medicaid enrollment following prison release. As a first step in addressing this gap, we sought to explore the past healthcare and Medicaid experiences among incarcerated persons who had serious medical conditions and were—based on prison system assessment—likely to qualify for Medicaid upon their release. Compounding the restrictive nature of the traditional Medicaid eligibility criteria in non-expansion states, our respondents’ experiences generally suggest the need for greater enrollment assistance among those likely to qualify for Medicaid.

Among the 20 respondents we interviewed, about half had been enrolled in Medicaid prior to their imprisonment, and more than half reported that they would need to enroll in Medicaid to gain healthcare coverage following their release. In examining their experiences using the Gelberg-Andersen Model, we found that these clustered within three groups based on respondents’ pre-incarceration Medicaid experience: never applied, encountered obstacles, and enrolled with little difficulty. Synthesizing the finding across these groups, we found that most respondents had a high level of medical need—particularly those in the latter two groups—but there was wide variation in their (a) predisposing factors such as Medicaid knowledge and attitudes, and (b) enabling factors, such as familial and institutional support.

Enabling factors seemed to be most closely related to past successes or failures enrolling in Medicaid. Those who successfully enrolled in disability or Medicaid received help with their application from (or had the application submitted on their behalf by) their mother, an employee of a hospital or prison at discharge from those facilities, or a DSS employee. Eleven inmates received such help with their first application and enrolled without difficulty, but two applied unsuccessfully on their own before receiving help, which enabled their enrollment. One respondent who never enrolled in Medicaid despite multiple attempts was advised to apply for Medicaid by a medical provider, but did not receive tangible help on an application. Given the inconsistency of available family advocates, these findings illustrate the importance of agencies helping individuals with their SSI and Medicaid applications. In theory, all participants who had applied for Medicaid prior to incarceration would have had access to assistance from a DSS officer; however, our prior interviews with prison system personnel tasked with submitting Medicaid applications on prisoners’ behalf suggest that there is wide variation in the resources and responsiveness of county DSS offices in North Carolina. Nevertheless, agency support may be especially important to incarcerated individuals who are often less educated and stable than the overall Medicaid-eligible population. These findings also highlight the role of socially supportive resources for sustaining men’s connection to formal healthcare systems.

For many respondents, attitudes toward and knowledge of Medicaid likely had a more distal impact on Medicaid enrollment than the availability of enrollment support, as there were some respondents who had low levels of knowledge or conflicting attitudes, but with assistance still enrolled in Medicaid. Respondents’ attitudes seemed to be largely influenced by medical need. Those with few significant pre-incarceration health problems often had formulated ideas, positive or negative, about Medicaid based on family members’ experiences with the program. Most of those who had enrolled in Medicaid before their incarceration expressed positive experiences with the program, and we found little evidence of stigma associated with needing Medicaid benefits. However, a few respondents believed that many Medicaid enrollees have little medical need for this coverage, and stated that they preferred to receive employer-based insurance over Medicaid. It is important to note that employment is not necessarily an exclusion criteria for Medicaid; however, many participants reported that Medicaid was more applicable for them after they lost the income from their job or were sick enough that they could not work. This phenomenon also may be reflected nationally, in that about 60% of non-elderly Medicaid-enrolled adults without SSI work either full or part time, but among enrollees who are disabled and have SSI, only 7% work [16, 17].

The most favorable attitudes about Medicaid enrollment were expressed by those with significant health problems who had difficulty enrolling in Medicaid pre-incarceration. For these respondents, the perceived consequences of not having Medicaid benefits were severe and grounded in actual experiences with lack of medical treatment, worsening health conditions, and financial hardship. Beyond attitudes, we found that Medicaid knowledge among respondents was very low overall, even among those who had Medicaid for multiple years prior to their incarceration. A lack of knowledge about the Medicaid program is not unique to correctional populations [18, 19]. Nevertheless, incarceration may provide an opportunity to educate prisoners about Medicaid. We are currently conducting a systematic survey of inmates regarding Medicaid and other social safety net programs to more thoroughly assess their knowledge of these programs and to identify content areas for which they would like more information.

Part of our rationale for examining respondents’ pre-incarceration enrollment in Medicaid was to gain insights into their future barriers and facilitators accessing Medicaid following their release from prison. Most respondents anticipated needing Medicaid or other sources of healthcare coverage at the time of their release. However, we speculate that similar to their pre-incarceration experiences, their ability to enroll may in large part hinge on whether they receive support in the enrollment process. There is a small but growing literature demonstrating that support provided in preparation for inmates’ release can be effective in fostering enrollment in Medicaid. For example, in a small study in Oklahoma of released prisoners with severe mental illness, those who were provided assistance enrolling in Medicaid (n = 77) during discharge planning were more likely to use Medicaid-funded mental health services within the first 90 days post-release than those without assistance [20]. And Morrissey et al. found that Washington state prisoners who were referred for expedited Medicaid enrollment in anticipation of release had greater rates of Medicaid enrollment and community healthcare than those without referral [21, 22]. Despite the potential impact of Medicaid enrollment, assistance remains uncommon, even in prison systems located in Medicaid expansion states. For example, a 2016 survey found that only six state prison systems in Medicaid expansion states were submitting applications for greater than 25% of their released inmates [23, 24].

In addition to providing context around prisoners’ pre-incarceration Medicaid enrollment experiences, our findings illustrate the dire consequences of failure or delayed enrolling in Medicaid for those who need it. Those in need of Medicaid who did not receive it experienced extreme financial hardship, unmet medical need, and worsening health conditions and even attributed their imprisonment to a lack of behavioral healthcare. Without post-release enrollment in Medicaid or other sources of healthcare coverage, our respondents are at risk for experiencing these same poor outcomes when they return to the community. Since conducting the interviews, at least three of our respondents died while still incarcerated, further emphasizing the extreme healthcare needs of this population during their incarceration and following release.

Even with optimal predisposing, enabling, and need factors, North Carolina as a non-expansion state has restrictive income and disability eligibility requirements, and childless adults without a disability are not typically eligible for Medicaid. Less restrictive eligibility criteria such as those implemented in states that expanded Medicaid under the ACA would serve as an important facilitator of enrollment.

This study has several limitations. We initially explored the use of several models to understand factors impacting Medicaid enrollment. Of these, we found that the Gelberg-Andersen Model provided the most useful framework, but we acknowledge that the model was designed to describe access to healthcare rather than enrollment in healthcare coverage. Given the importance of healthcare coverage as a means to access healthcare and minimize medical-related debt, we recommend the development of new models that are specific to healthcare coverage. Second, the number of respondents in our sample was limited. Nevertheless, this population was sufficient to convey a wide array of health and healthcare coverage experiences, expanding our understanding of the complexity of these issues among those involved in the criminal justice system. In fact, to our knowledge, the current analysis represents the only qualitative examination of community healthcare coverage experiences among justice-involved persons. Our study was cross-sectional and subject to recall bias. Although some respondents had been incarcerated for several years at the time of their interview, we found that many were able to relate detailed information about their experiences, particularly if the respondents had difficulty accessing healthcare coverage and care. In the future, we will build upon our current findings by employing population-based methods using existing data to examine the long-term trajectories of Medicaid coverage among criminal justice-involved populations with serious medical conditions. North Carolina is one of the majority of states that has a 1115 Waiver application for a Medicaid Reform Demonstration pending approval. North Carolina’s model includes managed care plans specifically tailored for high-utilizing populations such as Medicaid enrollees with behavioral health care needs. This and other proposed plan features could affect the take up of Medicaid coverage as well as access to covered services for criminal justice-involved adults. Finally, our study is limited by its focus on only one US state. Our results may not be generalizable to other states, particularly those who have expanded Medicaid or are located outside of the US South. At the same time, the lack of Medicaid enrollment of criminal justice-involved populations in other states—including in Medicaid expansion states—suggests that our results may have wider applicability than only North Carolina.

In summary, we found that in a Medicaid non-expansion state, inmates with serious health conditions reported a wide range of health and healthcare coverage experiences. Most had limited knowledge of Medicaid, even though about half had relied on Medicaid as an adult for healthcare coverage. Although more population-based assessments are necessary, the current findings indicate that greater assistance with Medicaid enrollment may be a key factor so that people in the criminal justice system who qualify for Medicaid—and other social safety net programs—may gain their rightful access to these benefits. Such access may benefit not only the individuals themselves but also the communities to which they return.

Acknowledgements

We thank the NC prison system administrators and inmates who made this project possible. This project was funded by the National Institutes of Health (R01 MD008979 and R21 MH099162). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The project was also supported by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Center for AIDS Research (CFAR, NIH Funded program P30 AI50410) and the UNC Criminal Justice Working Group. Drs. Golin and Wohl were also supported by career development grants (K24 HD069204 and K24 DA037101, respectively).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

All study procedures were approved by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Office of Human Research Ethics and the North Carolina Department of Public Safety’s Human Subjects Review Committee.

References

- 1.Mallik-Kane K, Visher CA. Health and prisoner reentry: how physical, mental, and substance abuse conditions shape the process of reintegration. Washington, DC: Urban Institute: Justice Policy Center; 2008.

- 2.Bandara SN, Huskamp HA, Riedel LE, McGinty EE, Webster D, Toone RE, Barry CL. Leveraging the affordable care act to enroll justice-involved populations in Medicaid: state and local efforts. Health Affairs (Project Hope) 2015;34(12):2044–2051. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Center CoSGJ . Policy brief: opportunities for criminal justice systems to increase Medicaid enrollment, improve outcomes, and maximize state and local budget savings. New York, NY: Council of State Governments Justice Center; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bainbridge AA. The affordable care act and criminal justice: intersections and implications. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Assistance, US Department of Justice; 2012.

- 5.Blair P, Griefinger R, Stone TH, Somers S. Increasing access to health insurance coverage for pre-trial detainees and individuals transitioning from correctional facilities under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Community-Oriented Correctional Health Services. 2011. (Exploring health reform and criminal justice: rethinking the connection between jails and community health).

- 6.Cuellar AE, Cheema J. As roughly 700,000 prisoners are released annually, about half will gain health coverage and care under federal laws. Health Affairs (Project Hope) 2012;31(5):931–938. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosen DL, Grodensky CA, Holley TK. Federally-assisted healthcare coverage among male state prisoners with chronic health problems. PLoS One. 2016;11(8):e0160085. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0160085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garfield R, Damico A. The coverage gap: uninsured poor adults in states that do not expand Medicaid. San Francisco, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2017.

- 9.Stein JA, Andersen R, Gelberg L. Applying the Gelberg-Andersen behavioral model for vulnerable populations to health services utilization in homeless women. J Health Psychol. 2007;12(5):791–804. doi: 10.1177/1359105307080612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Toledo LA. Understanding Medicaid and its impact in North Carolina: a chart book. In: Center NCJCBT, ed. 2017. p. 1–27.

- 11.Rosen DL, et al. Implementing a prison Medicaid enrollment program for inmates with a community inpatient hospitalization. J Urban Health. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.SocioCultural Research Consultants L. Dedoose ersion 7.0.23 web application for managing, analyzing, and presenting qualitative and mixed method research data. 2016. www.dedoose.com. Accessed December 2016.

- 13.Maietta RC, Mihas P. Sort & sift, think and shift: let the data be your guide, in ResearchTalk Fall Seminar Series 2015. Chapel Hill, NC.

- 14.Glanz K, R.B, Viswanath KV. Health belief model. In: Health behavior and health education: theory research and practice. 4th ed. San Francisco, CA; 2008.

- 15.Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Predicting and changing behavior: the reasoned action approach. New York, NY: Psychology Press (Taylor & Francis); 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foundation KF. How might Medicaid adults with disabilities be affected by work requirements in section 1115 waiver programs? San Francisco, CA; 2018.

- 17.Foundation KF. Understanding the intersection of Medicaid and work. San Francisco, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2018.

- 18.Fryling LR, Mazanec P, Rodriguez RM. Barriers to homeless persons acquiring health insurance through the Affordable Care Act. J Emerg Med. 2015;49(5):755–762.e752. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2015.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kenney GM, Haley JM, Anderson N, Lynch V. Children eligible for Medicaid or CHIP: who remains uninsured, and why? Acad Pediatr. 2015;15(3 Suppl):S36–S43. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2015.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wenzlow AT, Ireys HT, Mann B, Irvin C, Teich JL. Effects of a discharge planning program on Medicaid coverage of state prisoners with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv (Washington, DC) 2011;62(1):73–78. doi: 10.1176/ps.62.1.pss6201_0073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morrissey JP, Domino ME, Cuddeback GS. Expedited Medicaid enrollment, mental health service use, and criminal recidivism among released prisoners with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv (Washington, DC) 2016;67(8):842–849. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201500305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cuddeback GS, Morrissey JP, Domino ME. Enrollment and service use patterns among persons with severe mental illness receiving expedited medicaid on release from state prisons, county jails, and psychiatric hospitals. Psychiatr Serv (Washington, DC) 2016;67(8):835–841. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201500306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwartzapfel B. Out of prison, uncovered: Medicaid for ex-prisoners saves money and lives, but millions are released without it. The Marshall Report: Nonprofit Journalism about Criminal Justice. New York, NY; 2016.

- 24.Schwartzapfel B, Hancock J. Personal communication with author. 2017.