Abstract

Obesity is often associated with increased pain, but little is known about the effects of obesity and diet on postoperative pain. In this study, effects of diet and obesity were examined in the paw incision model, a preclinical model of postoperative pain. Long-Evans rats were fed high-fat diet (40% calories from butter fat) or low-fat normal chow. Male rats fed high-fat diet starting 6 weeks prior to incision (a diet previously shown to induce markers of obesity) had prolonged mechanical hypersensitivity and an overall increase in spontaneous pain in response to paw incision, compared to normal chow controls. Diet effects in females were minor. Removing high-fat diet for two weeks prior to incision reversed the diet effects on pain behaviors, although this was not enough time to reverse high-fat diet-induced weight gain. A shorter (one week) exposure to high-fat diet prior to incision also increased pain behaviors in males, albeit to a lesser degree. The 6 week high-fat diet increased macrophage density as examined immunohistochemically in lumbar DRG even prior to paw incision, especially in males, and sensitized responses of peritoneal macrophages to lipopolysaccharide stimuli in vitro. The nerve regeneration marker growth-associated protein 43 (GAP43) in skin near the incision (day 4) was higher in the high-fat diet group, and wound healing was delayed. In summary, high-fat diet increased postoperative pain particularly in males, but some diet effects did not depend on weight gain. Even short-term dietary manipulations, that do not affect obesity, may enhance postoperative pain.

Keywords: obesity, high-fat diet, postoperative pain, paw incision, macrophage

Introduction

Obesity co-morbidities include cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and cancer [68]. Obesity is also associated with a greater incidence and severity of chronic pain conditions [1; 32], partly due to the accompanying low-grade chronic inflammation [26]. Macrophages are increased in obese adipose tissue; these are polarized towards type 1 (“classical”) inflammation macrophages [31]. Leptin, produced by adipose tissue and elevated in obesity, is pro-inflammatory in addition to playing metabolic roles [35].

In perioperative medicine, obesity affects airway management, drug dosing, thrombosis, and sleep apnea [33], and is associated with impaired wound healing and increased infection risk [37; 54].

Preclinical experiments using genetic and diet-induced obesity models show increased pain in neuropathic, radicular, and inflammatory pain models [11; 49; 55; 57; 58]. However, there are few preclinical studies of obesity effects on postoperative pain, which has distinct mechanisms from inflammatory and neuropathic pain [4]. Here, we used the rodent paw incision model of postoperative pain [4; 5], that leads to thermal and mechanical hypersensitivity to evoked stimuli, and to guarding behavior, a measure of spontaneous pain. Both spontaneous and evoked pain are observed in human surgery patients [4].

Most obesity is caused by environmental, not genetic, factors with particular emphasis on high-fat diets [68]. We used an established rat model of diet-induced obesity, feeding Long-Evans rats a high-fat diet that induces increased body weight and other hallmarks of human obesity such as increased percent body fat and plasma leptin, and insulin resistance [59]. Both sexes are affected by the diet [47; 59]. Recent studies emphasize the importance of studying both sexes in pain research [14], so both sexes were included in our study. This led us to observe unexpected differences between the sexes in the interaction between postoperative pain and diet.

Material and Methods

Animals

Additional details about the methods used are provided in Supplemental Digital Content 1. All surgical procedures and the experimental protocol were approved by the institutional animal care and use committee of the University of Cincinnati and conformed to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines for animal research. Long-Evans rats of both sexes were used, as indicated. Rats were housed two per cage at 22°± 0.5°C under a controlled diurnal cycle of 14-h light and 10-h dark with free access to water and food. Rats were switched from the conventional open formula low fat chow to a synthetic semi-purified diet with 40% of the calories from fat, primarily butter fat (Research Diets, catalog D03082706, “Tso diet”) as indicated, and compared to control age-matched rats that continued to receive the normal (low fat) chow.

Plantar Incisional Model of Postoperative Pain

The surgery was performed as previously described by Brennan et al. [5] Briefly, under isoflurane anesthesia, a longitudinal incision was made through skin and fascia of the plantar aspect of the right hind paw starting 0.5 cm from the proximal edge of the heel and extending 1 cm. The plantaris muscle was elevated and blunt dissected longitudinally. The muscle origin and insertion remained intact. The skin was closed with two 5-0 nylon sutures.

Behavioral Testing

Mechanical paw withdrawal threshold (MPWT) was tested with six applications of von Frey filaments, using the up-and-down method [9], at the medial side of the wound (site 1). In the first experiment a site remote to the end of the incision (site 2) was also tested (see Supplemental Digital Content 2 which includes a diagram of the test sites). A cutoff value of 15-gram was used, which rarely evoked a response in normal rats. In the first experiment, thermal paw withdrawal latency (TPWL) was measured by applying a focused radiant heat source from beneath a glass floor to site 1. A cutoff of 20 s was set to avoid tissue damage. The TPWL was calculated as the average of four of the six measurements, excluding the highest and lowest values. Since diet effects on thermal pain behaviors were small, this test was omitted in later experiments.

Spontaneous pain was measured according to the method originally described by Brennan et al. [5]. Briefly, both hindpaws were closely observed 6 times at 5 minute intervals. The guarding score was determined by the position of the paw for the majority of time during the 1 min observation period as 0: no guarding, paw flat on the mesh; 1: the paw touched the mesh gently without any blanching or distortion; and 2: the paw was completely off the mesh. These six scores were recorded just before each application of the von Frey filament and the sum is presented as the spontaneous pain score.

It was not feasible to blind the experimenter to the diet status of the animals, due to obvious weight gain and to the presence of dye in the high-fat diet that discolors the feces.

Immunohistochemistry

Rats were perfused with 0.1 M phosphate buffer followed by 4% paraformaldehyde, and the ipsilateral L4 and L5 DRGs or paw skin were dissected, and post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. 40-μm sections were stained with the following primary antibodies: goat anti-Iba-1, (Abcam, catalog ab5076, diluted 1:500), a general marker for macrophages and microglia [19–21]; rabbit anti-GAP43 (Abcam, catalog ab507616053, diluted 1:500); and goat anti-β tubulin (Abcam, catalog ab6046, diluted 1:500). Images were obtained from multiple DRG sections that were randomly selected without regard to the signal level. Only regions containing neuronal cell bodies were captured. Paw skin sections were taken from the area within 1 mm in either direction from the central wound site. Images were captured using an Olympus BX61 fluorescent microscope with Slidebook 6.1 imaging acquisition software (Intelligent Imaging Innovation, Denver, CO) and overall intensity density (summed value of the signal above background divided by the area) was measured. Data from multiple sections was averaged to get the mean values for each rat, which were then used in the statistical analysis. The density of the Iba-1 in high-fat diet group was normalized to that from paired normal chow rats observed side-by-side.

Peritoneal macrophage isolation and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) treatment

Peritoneal macrophages were isolated as described by Zhang et al. [66], by lavage of the peritoneal cavity. Cells were pelleted and resuspended into a 24-well plate with (per well) 4×105 cell in 1 mL DMEM culture medium (Thermo Fisher), rinsed after 45 minutes to remove non-adherent cells, then cultured in the indicated doses of LPS for 20 hours before isolation of total RNA.

Quantitative PCR

Total RNA was isolated from cultured macrophages, reverse transcribed, and diluted, then stored at −20°C until further analysis. Quantitative real time RT-PCR (qPCR) was performed on a QuantStudio™ 3 Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher) using FastStart Universal SYBR Green Master (Roche). Gene expression was normalized by the house keeping gene hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase 1 (HPRT) from the same sample and is presented as the fold increase from the baseline without LPS treatment. The relative gene expression was calculated with the standard 2−ΔΔCT method [43].

Electrophysiological recording in isolated whole DRG preparations

Spontaneous activity, resting potential, and action potential parameters were measured in current clamp mode at 36 – 37°C using microelectrodes in an acutely isolated whole DRG preparation, as previously described [61]. This preparation allows neurons to be recorded without enzymatic dissociation, with the surrounding satellite glia cells and neighboring neurons remaining intact [48; 65]. Cells were classified as myelinated if they had action potential durations <1.5 msec, and as C cells if they had action potential durations ≥1.5 msec, based on a previous study [62] in which dorsal root conduction velocity was measured.

Data Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Prism, La Jolla, CA), except for 3-way ANOVA analysis which was done using GBStat analysis software (Dynamic Microsystems Inc., Silver Spring, MD). Data are presented as mean ± SEM except where indicated. Weight time course, behavioral time course data in experiments with only males, and LPS dose-response data, were analyzed with two-way repeated measure ANOVA to determine overall differences between diet groups, with Bonferroni posttests to determine significance of differences between groups at each individual time point or dose. Where indicated, dose-response data were also analyzed with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s posttest within each group, to determine at which times or doses values differed significantly from baseline. Behavioral data in experiments including both males and females was analyzed with 3-way ANOVA using sex, diet, and time (repeated measure) as factors. For experiments in which an overall diet effect was significant, the protected Newman-Keuls posttest was used to determine on which days the high-fat diet group differed from controls. Very similar findings were obtained using the Tukey-Kramer posttest. For clarity these experiments are presented with the male and female data plotted separately. Immunohistochemical expression was analyzed with the Mann-Whitney test. Electrophysiological data were analyzed with the Kruskal Wallace test with Dunn’s multiple comparison posttest, as indicated. Significance was ascribed for p<0.05. Level of significance is indicated by the number of symbols: e.g., *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001.

Results

High-fat diet for 6 weeks prolonged incisional pain in a sex-dependent manner

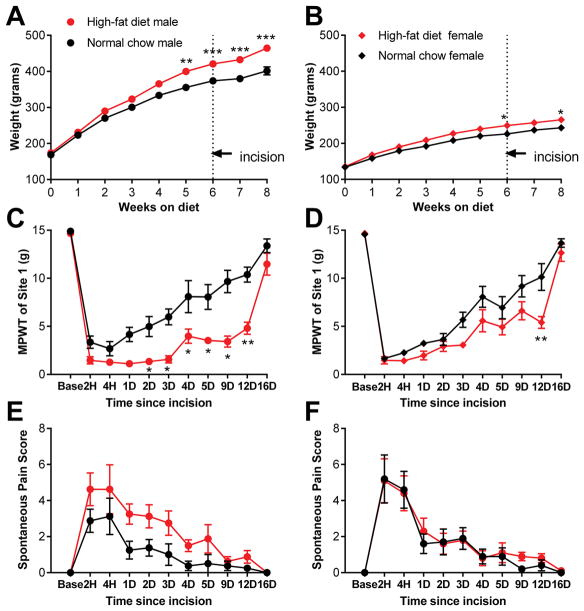

We first used the obesity model described by Woods et al. [59] who showed that ad libitum feeding of Long-Evans rats with a semi-synthetic defined high-fat (primarily butter fat) diet leads to increased body weight, plasma leptin, and percent body fat (which is more dramatic and robust than the overall weight increase), as well as insulin resistance, in both sexes. We have previously confirmed that the diet has similar effects as implemented in our laboratory, with increased weight, percent body fat, insulin, and leptin measured after 6 – 8 weeks on the diet [49]. Rats were maintained on this high-fat diet for 6 weeks, at which point the paw incision model of postoperative pain was implemented. The diet was then continued and pain measurements were made for another 2 weeks. Control, age-matched rats continued to receive normal (low fat) chow throughout the duration of the experiment. As shown in Figure 1, differences in body weight were significant in both males and females at the time of paw incision (significance of diet factor, p = 0.0025 in males and p = 0.02 in females). There were no effects of diet or sex on baseline behavior measurements made before paw incision, although it should be noted that most of the measures we used are not designed to measure baseline nociception, since they have floor or ceiling effects in normal animals. Paw incision induced robust mechanical hypersensitivity and spontaneous pain in both diet groups and both sexes. In male rats fed the high-fat diet, mechanical hypersensitivity was prolonged, with the threshold for paw withdrawal remaining significantly lower than normal chow-fed rats for over a week. In females, the effect of high-fat diet was much more modest, with differences between the diet groups reaching significance at only one post-incision time point. The 3-way ANOVA analysis showed a main effect of diet (p<0.001) and sex X diet interaction (p =0.046) for the von Frey test. A marked prolongation of mechanical pain in males on the high-fat diet was also observed during testing of a hindpaw site that was remote from the incision site (see Supplemental Digital Content 2, which contains additional behavioral data from this experiment). Spontaneous pain scores (Figure 1E, F) showed a main effect of diet (p = 0.04), although this did not reach significance on individual days in the posttest and appeared to primarily reflect lower scores in the male normal chow group. Thermal withdrawal latencies were also reduced by paw incision, and this effect was mildly exacerbated by high-fat diet in males, as there were significant main effects of diet and sex in the 3-way ANOVA that did not reach significance in posttests for individual days (Supplemental Digital Content 2).

Figure 1.

Effect of high-fat diet-induced obesity on incisional pain model differs between the sexes. Data from males is on the left, females on the right. A, B, weight of rats maintained for indicated time on high-fat diet (red) or continued on normal chow (black). Paw incision was performed after 6 weeks on the diet. *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001, significant difference between the high-fat and normal chow groups of the same sex at the indicated time points, based on 2-way repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni posttest. Pain measurements at the indicated hours (H) or days (D) after paw incision are indicated in C – F. Baseline measurements (“base”) are the average of 2 measurements prior to incision. C, D, mechanical pain withdrawal threshold (MPWT; von Frey test) at site 1, near incision. E, F, Spontaneous pain scores. N = 12 male and 10 female rats per group. *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; significant difference between the high-fat and normal chow groups of the same sex at the indicated time points, based on 3-way repeated measures ANOVA with Newman-Keuls posttest. Two females per group were not tested on the day 16 time point, so no data from that time point was included in the ANOVA analysis, but the average of the remaining 8 females per group, and of the males, is shown to aid visual comparisons.

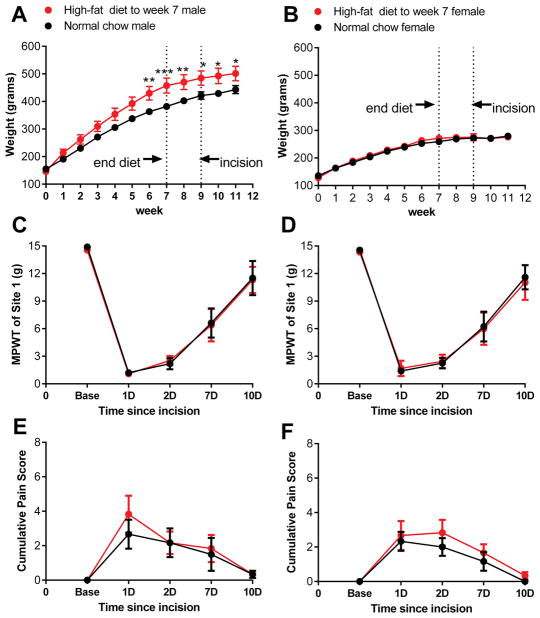

Switching back to normal chow for two weeks mitigated high-fat diet effects on incisional pain

We next performed an experiment to determine whether a short-term return to the normal low-fat chow prior to paw excision could mitigate the effects of high-fat diet on incisional pain. Rats were fed high-fat diet for 7 weeks, then switched back to normal chow for 2 weeks prior to paw incision. As shown in figure 2, after this short-term reversal of diet, no effects of diet on either mechanical or spontaneous pain were observed. The 3-way ANOVA analysis showed no main effects of diet or sex, or diet x sex interaction, for either von Frey or guarding behavior measures. Both sexes responded to paw incision with very similar pain behaviors, with an overall trajectory similar to that observed in rats maintained throughout on normal chow (compare to figure 1). It should be noted that this particular cohort of female rats did not gain body weight on the high-fat diet. While the reasons for the variable body weight response in females are not clear, the data indicate that short term high-fat diet does not markedly impact post-incision pain behavior in females regardless of whether they gain body weight on the diet (Figure 1) or not (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Short term removal of high-fat diet mitigates diet effects on incisional pain. Data from males is on the left, females on the right. A, B, weight of rats maintained on high-fat diet for 7 weeks before being switched back to normal chow (red) or continued on normal chow throughout (black). *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001, significant difference in weight between the high-fat and normal chow groups at the indicated time points (2-way repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni posttest). Paw incision was performed at 9 weeks, i.e. 2 weeks after removal of the high-fat diet. Pain measurements at the indicated hours (H) or days (D) after paw incision are indicated: C, D, mechanical pain withdrawal threshold (MPWT; von Frey test) at site 1, near incision and E, F, spontaneous pain scores, did not differ between diet-exposure groups, or between the sexes), based on 3-way ANOVA analysis (male and female data plotted on same axes but separate graphs, for comparison). N = 6 male and 6 female rats per group.

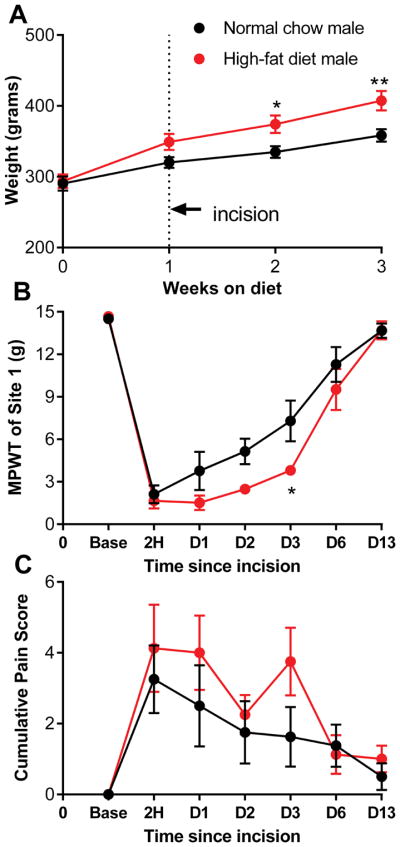

Just one-week of high-fat diet consumption affects pain behaviors

As prolonged high-fat diet intake increased pain behaviors specifically in male rats, we next determined whether a much shorter exposure to high-fat diet could similarly increase pain behaviors after paw incision. (Note that this experiment was conducted in male rats only, as high-fat diet intake was unable to markedly alter pain behaviors in females even after 6 weeks of consumption.) Once chow-fed rats reached ~300 grams body weight (so that the body weight at the time of paw incision was comparable to that in the other experiments), they were switched to the high-fat diet. Paw incision was performed after one week on the high-fat diet and the diet was continued after the incision. As shown in Figure 3, one week of high-fat feeding prolonged the post-incision mechanical pain, but this effect was not as marked as after 6 weeks of high-fat diet feeding. Two-way repeated measures ANOVA did not indicate an overall significance between the two diet groups, but the interaction between time and diet was significant (p = 0.04) and posttests indicated significance on day 4 for the von Frey test.

Figure 3.

Short term exposure to high-fat diet has a smaller effect on incisional pain. A, weight of rats maintained for indicated time on high-fat diet (red) or continued on normal chow (black). Paw incision was performed 1 week after starting the high-fat diet. Pain measurements at the indicated hours (H) or days (D) after paw incision are indicated: B, mechanical pain withdrawal threshold (MPWT; von Frey test) at site 1, near incision and C, spontaneous pain scores. *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001, significant difference between the high-fat and normal chow groups in weight at the indicated time points (2-way repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni posttest). N = 8 male rats per group.

High-fat diet and paw incision had minor effects on DRG cell excitability

Recordings in whole DRG preparations isolated from male rats maintained on high-fat diet for 6 weeks showed only minor effects of diet on sensory neuron excitability (Supplemental Digital Content 3, 4 and 5, which show electrophysiological data from both diet groups, before and at 4 days after paw incision). Compared to DRG from matched controls maintained on normal chow, high-fat diet increased the rheobase of myelinated DRG cells, and reduced the percentage of myelinated cells firing multiple action potentials with suprathreshold stimuli, indicating that the high-fat diet reduced excitability in the absence of a pain model. No significant differences were observed in C cells before paw incision. In contrast, paw incision significantly increased excitability in myelinated cells only in the high-fat diet groups. Measures of increased excitability included decreased rheobase, increased spontaneous activity, increased percentage of cells firing more than 2 action potentials with suprathreshold stimuli, and increased number of action potentials evoked by a stimulus. C cells showed only the latter effect of paw incision, plus a small hyperpolarization, that were both observed only in the high-fat diet group. Overall the excitability changes and degree of spontaneous activity were much smaller than that observed in other pain models under the same recording conditions [60; 63].

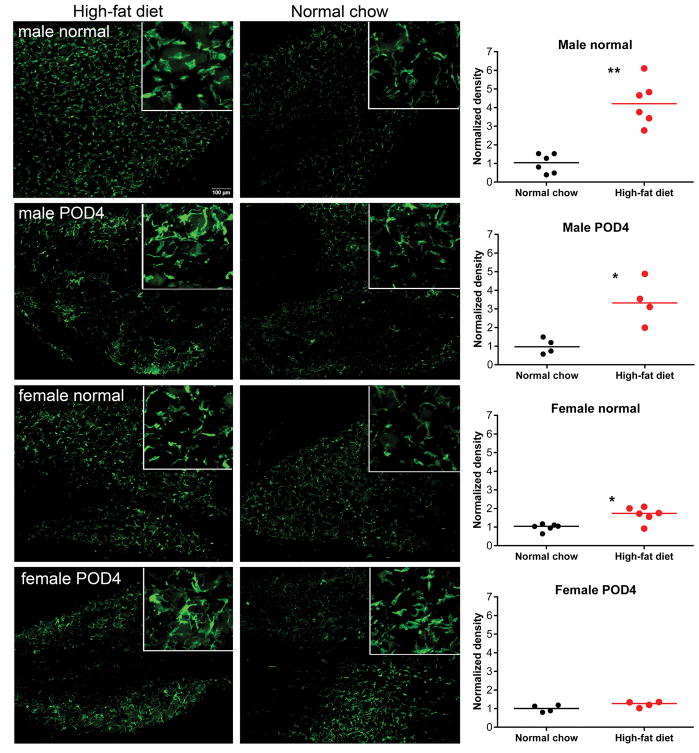

High-fat diet increased macrophage density in the DRG

Changes in macrophages occur in obesity, and macrophages within the DRG play a role in several pain models [27]. In addition, macrophages and their brain counterparts, microglia, have been implicated in sex differences in pain mechanisms (see Discussion). We next examined the effect of the 6-week high-fat diet exposure on macrophage density in the DRG, using Iba-1, a marker of microglia and peripheral macrophages with broad specificity[19–21]. As shown in Figure 4, 6-week exposure to high-fat diet in the absence of any pain model increased Iba-1-positive immunolabeling in L4/L5 DRG. This effect was significantly larger (p = 0.02, Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s posttest) in males (>4 fold) than in females (~1.7-fold). Moreover, high-fat diet increased Iba-1-positive immunolabeling in DRG of males, but not females, at four days after paw incision. Notably, the macrophages appeared to be larger and have more lamellipodia after incision in both males and females.

Figure 4.

Effect of diet on macrophages in the DRG. Example sections are shown of L4/L5 DRG immunolabeled with the macrophage marker Iba-1 in the absence of a pain model (“normal”) or at 4 days after ipsilateral paw incision. Rats in the high-fat diet group were fed high-fat diet starting 6 weeks prior to paw incision or isolation of normal DRG samples. Insets, 3x higher magnification. Summary data show median and scatter plots (each point represents one animal average from measurement of signal density in 15 – 20 sections). *, p< 0.05; **, p<0.01; significant difference between the groups (Mann-Whitney test). In each of the four experiments shown, values in the high-fat group were normalized to the average value in the normal chow group measured side-by-side.

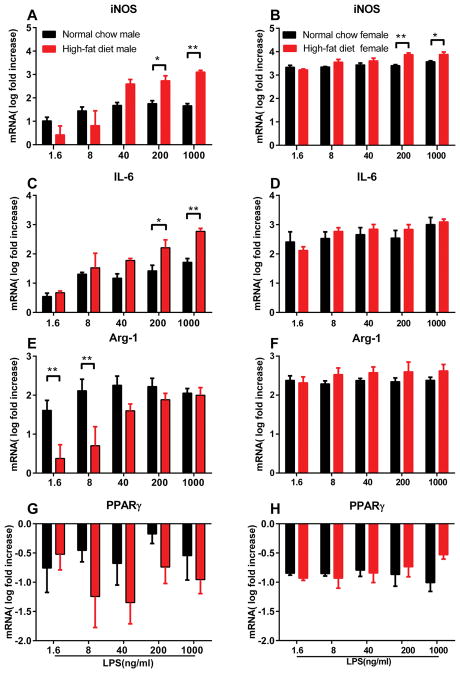

High-fat diet altered in vitro LPS sensitivity of resident peritoneal macrophages

Peritoneal macrophages acutely isolated from rats maintained on normal chow or the high-fat diet for 6 weeks were treated with LPS in vitro for 20 hours, and the expression of genes related to macrophage activation was measured with real time PCR. We found that the survival of macrophages from high-fat vs. normal chow male rats was quite different, even in preparations prepared side by side, making absolute comparisons less meaningful. Despite appearing similar during isolation and initial culture, the number of macrophages surviving to the next day was much lower in cultures from male rats maintained on the high-fat diet. Therefore, to investigate LPS sensitivity, we examined the expression of target genes as fold-increases from the expression at baseline (no added LPS) within each group. As shown in figure 5, LPS treatment increased expression of the M1-markers inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) in macrophages in all groups (one-way ANOVAs with Dunnett’s posttest within each group). However, lower doses of LPS were effective in upregulating iNOS and IL-6 in macrophages taken from males on high-fat diet vs normal chow. In females, the effect of diet was less striking, with a diet effect observed only at the highest doses (iNOS), or not at all (IL-6). However, the absolute values of the fold-induction of these two genes was much higher in females, even at the lowest doses.

Figure 5.

Effect of diet and sex on in vitro LPS response of peritoneal macrophages. Peritoneal macrophages were isolated after 6 weeks on the indicated diet, cultured, and exposed to the indicated concentration of LPS for 20 hours prior to isolation of RNA and synthesis of cDNA. Gene expression data (normalized to housekeeping gene HPRT) is presented normalized to the expression in 0 LPS within each group and log10 transformed. Data from males is on the left, from females on the right. A, B, iNOS expression; C, D, IL-6 expression; E, F, arginase-1 expression; G, H, PPARγ expression. N = 5 male rats (normal chow group), 6 male rats (high-fat diet group), and 4 female rats per group. *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001, significant difference between the high-fat and normal chow groups on gene expression at the indicated LPS doses (2-way repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni posttest performed on the log-transformed ratios).

We also examined expression of Arg-1. Though considered a marker of M-2 activation, Arg-1 can also be increased by LPS in macrophages (albeit more slowly than iNOS) [22; 25; 42]. Arg-1 expression increased with LPS treatment in all groups; there was also an effect of diet specifically in males, with the normal chow group showing significantly higher expression than the high-fat group at the lower LPS concentrations tested.

Expression of the M2 marker PPARγ was generally down-regulated by LPS, although the latter effect did not reach significance in the male normal chow group (one-way ANOVAs with Dunnett’s posttest within each group). There was no effect of diet on expression of PPARγ in either sex.

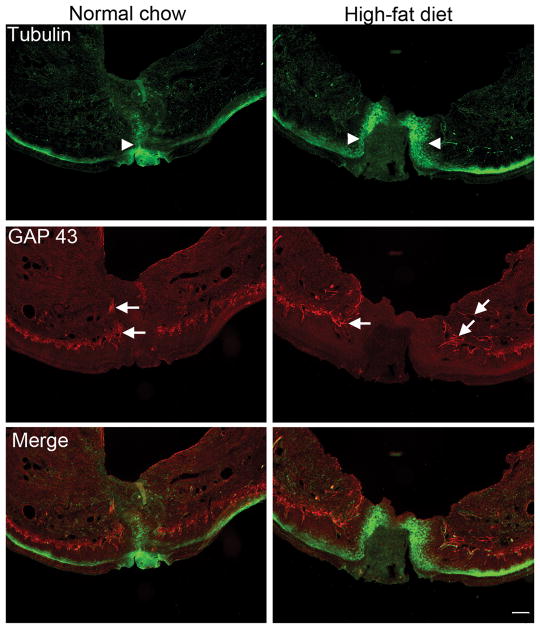

High-fat diet delayed skin wound healing and increased the density of regenerating nerve fibers near the incision site

Obesity is associated with impaired wound healing (see Discussion). Examination of cross-sections of paw skin at the incision site showed that the wound was closed at 4 days after incision in male rats fed normal chow, but that a substantial gap was still evident in male rats fed high-fat diet for 6 weeks prior to incision (Figure 6). GAP43, a biochemical marker for actively regenerating nerve fibers, has been found to be associated with the persistence of neuropathic pain in a recent study [64]. GAP43 was largely absent in paw skin from normal rats regardless of diet, but was evident especially around the incision site 4 days after incision. Moreover, the intensity of GAP43 staining was ~4 times higher in rats fed the high-fat diet (p = 0.03, Mann Whitney test; summary data shown in Supplemental Digital Content 6), consistent with the delay in healing.

Figure 6.

High-fat diet prolongs wound healing and GAP43-positive immunolabeling after paw incision. Representative micrographs of paw skin at 4 days after paw incision, from rats fed normal chow (left) or high-fat diet for 6 weeks prior to incision (right). Tubulin-positive immunolabeling (marker for peripheral nerve fibers), green; GAP43; red. Arrowheads indicate edge of incision wound. Arrows indicate examples of GAP43-positive fibers. Scale bar, 400 μm. Similar observations were made in 4 male rats per group. Summary data of GAP43 labeling intensity is shown in Supplemental Digital Content 6.

Discussion

Postoperative pain is distinct from inflammatory and neuropathic pain [4]. Understanding postoperative pain is important not only because of the large number of surgeries performed each year resulting in acute pain, but because higher levels of acute postoperative pain are a risk factor for development of chronic pain [30]. Here, we investigated effects of high-fat diet and obesity in a postoperative pain model.

A primary finding of this study is that a commonly used model of diet-induced obesity, feeding Long-Evans rats a high-fat (primarily butter fat) diet, prolongs pain behaviors and delays wound healing in a model of postoperative pain induced by hindpaw incision, and that these effects occur to a larger extent in male versus female rats. Previous preclinical studies have shown exacerbation of pain by diet-induced or genetically-induced obesity in models of other types of pain, and clinical studies also support a relationship between obesity and pain (see Introduction). An unexpected finding in our study was that in males a two-week return to low-fat chow prior to the paw incision was sufficient to block the pro-nociceptive effect of the high-fat diet exposure, even though this is not enough time to reverse weight gain (Fig. 2) or obesity [16]. Conversely, even a very short exposure to the high-fat diet (one week) was sufficient to enhance some pain behaviors in males, despite being insufficient to induce weight gain. These findings indicate that some pain-enhancing effects of high-fat diet may be dissociated from body weight and/or obesity per se. A similar dissociation has been observed in other preclinical pain models [49; 57]. This dissociation has important implications for clinical studies and possibly clinical practice. Given the great difficulty in reversing obesity in humans [15; 40], it is encouraging to think that perhaps simply changing the diet for a few weeks before a planned surgery might improve postoperative pain even if no weight loss occurs. In addition, most human studies in this field use the body mass index (BMI) as an indicator of obesity, and do not directly examine the short-term or long-term dietary intake of the subjects. It may be important to include this variable in future studies, particularly since preclinical studies show that other consequences of obesogenic diets (e.g., on fat mass, immune function, and various metabolic parameters or pathologies associated with obesity) may also occur before or even in the absence of significant total body weight gain (e.g. [6; 28; 38; 53]).

In our study the effects of diet on pain behaviors were predominantly observed in males. This is in contrast to our previous study [49] of effects of the same diet on models of radicular pain and peripheral inflammatory pain, in which sex differences were minimal. Similar to other studies in both rats and mice [2; 7; 24], we did not observe marked sex differences in the response to paw incision in animals fed normal chow. However, the responses to the incisional pain model are affected by manipulations of the prolactin system only in females [34]. In humans, studies of sex differences in postoperative pain have yielded mixed results [12], or shown relatively small differences that may not be clinically significant [13]. Some studies suggest pain is greater in females, but one study showed this difference was accounted for by differences in pre-surgical chronic pain, as well as differences in age [67]. Most of these studies did not examine diet or obesity as possible confounding variables in addition to sex.

We observed a delay in wound healing in our obese animals, as indicated by a larger unclosed wound and continued presence of actively regenerating nerve fibers on day 4. This is consistent with other preclinical [29; 36; 45] and clinical [37] studies. During wound healing, inflammation progresses from type 1 (classical inflammation) to type 2 (tissue repair). The obesity-induced skewing towards type 1 inflammation has been proposed to play a role in prolonged wound healing [37]. The prolonged pain behaviors we observed may in part reflect this prolongation of wound healing, which in turn may be due to systemic effects of the diet on the immune system.

In a recently study, we found that active nerve regeneration contributes to the prolongation of neuropathic pain [64]. The density of GAP43-positive regenerating nerve fibers in the vicinity of the incision in high-fat diet-fed rats is associated with the process of wound healing, and may also contribute to the observed prolongation of pain behaviors.

In comparison to other pain models, the direct effects of diet and paw incision on electrophysiological properties of sensory neurons were relatively small. We did not differentiate between the many functional subtypes of sensory neurons, except to define myelinated and unmyelinated, so effects on a particular subset would likely not have been detected. The lack of large effects of paw incision could also be due to a smaller proportion of lumbar sensory neurons being affected by this model, since we recorded from whole DRGs without identifying the subset of neurons that innervate the hindpaw. In addition, if obesity caused an increase in circulating molecules that affected sensory neuron excitability, these might have been ‘washed out’ in our in vitro recording conditions. A study of large DRG neurons using methods similar to ours showed no changes in excitability at 72 hours after incision [39]. Although we observed almost no effects of either paw incision or high-fat diet on unmyelinated C cells, fiber recording studies showed increased nociceptor (C and Aδ fiber) spontaneous activity in the paw incision model, and unlike our study, examined only axons originating near the incision. This activity could be blocked by local anesthetics near the incision site [4]; it is therefore not surprising that this increase in spontaneous activity was not captured by recordings in isolated DRG. More generally, obesity has been shown to increase small-fiber neuropathy [17], which in turn can be a cause of chronic pain as well as slowed wound healing [18].

Macrophages play important roles in mediating the low-grade inflammatory state induced by obesity [8; 44]. We observed sex-dependent skewing of macrophage function towards a more M1 phenotype in cultured peritoneal macrophages from obese animals, and a high-fat diet-induced increase in macrophage density in the sensory ganglia that was more marked in males. Regarding the latter finding, it is interesting that a recent study of chemotherapy-induced pain showed that an intact gut microbiome was required for induction of pain (in both sexes); that this effect was mediated by macrophages; and that macrophage infiltration into the DRG was reduced when the gut microbiome was reduced by antibiotics [46]. More generally, alterations in the gut microbiome have been proposed to play a role in the low-grade inflammation seen in obesity or during high-fat diets, in part due to macrophage activation. LPS derived from gut microbes acting on LPS receptors such as the toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) is one proposed mechanism for this macrophage activation [41]. Sex differences in macrophage responses have been described, including generally higher expression of TLR4 receptors in males, which would be consistent with the findings of our study. However, in general it is thought that females mount stronger innate immune responses and are more susceptible to inflammation [23; 41]. Moreover, many individual components of the diet, including particular types of fat, may have specific effects on the immune system, inflammation, and pain [56], which suggests additional mechanisms for a dissociation between the effects of diet and obesity per se on pain phenotypes.

We initially focused on macrophages because previous studies showed that sex differences in pain mechanisms may reflect sex-differences in immune cells, especially macrophages or their CNS counterparts, microglia [3; 10]. For example, responses to the spared nerve injury model of neuropathic pain rely on microglia in males, but on T cells in females [51], and direct activation of spinal microglia receptors induced pain only in males [50]. Although inflammatory and neuropathic pain models may lead to increased microglia activation as measured by the broad-specificity macrophage/microglia marker Iba-1 in both sexes, this similarity masks crucial differences in downstream signaling pathways that differ between the sexes [10; 52]. The diet-induced increase in DRG macrophages (Iba-1 signal) we observed may be a peripheral counterpart to the diet-induced increases in spinal microglia observed with a more naturalistic obesity-inducing diet, prior to any pain model, that interestingly also showed sex-specific increases in systemic cytokines with females having more T-cell related cytokines [55]. Rapidly increased microglia activation (Iba-1 signal) has also been observed in rat hypothalamus after high-fat diet [53]. It will be of interest to examine effects of diet on DRG macrophages with specific markers of macrophage subtypes and downstream signaling pathways, to determine whether effects analogous to those seen in spinal cord and brain studies occur in the periphery, and whether the Iba-1 increase reflects macrophage activation, proliferation, and/or infiltration.

In summary, this study shows that a high-fat diet increases pain behaviors in a post-surgical pain model. Some of these effects occur rapidly, and independently of body weight gain. Diet effects on the immune system provide one likely mechanism.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by in part by grants from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NS045594, NS055860 to J-M Zhang), and National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (AR068989 to J-M Zhang), Bethesda, MD, USA; and the National Natural Science Foundation of China, Changsha, PRC, (81300958, to Z. Song). Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

List of supplemental materials

The supplemental materials file (.pdf) contains the following:

Supplemental Digital Content 1: Supplemental Material and Methods

Supplemental Digital Content 2: Supplemental Figure 1, additional behavioral data.

Supplemental digital content 3: Supplemental Table 1, Electrophysiological parameters of DRG neurons

Supplemental Digital Content 4: Supplemental Figure 2: Electrophysiological parameters of myelinated cells.

Supplemental Digital Content 5: Supplemental Figure 3: Electrophysiological parameters of C cells.

Supplemental Digital Content 6. Supplemental Figure 4: Summary data of GAP43 intensity for Figure 6

References for Supplemental Digital Content

References

- 1.Arranz LI, Rafecas M, Alegre C. Effects of obesity on function and quality of life in chronic pain conditions. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2014;16(1):390. doi: 10.1007/s11926-013-0390-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banik RK, Woo YC, Park SS, Brennan TJ. Strain and sex influence on pain sensitivity after plantar incision in the mouse. Anesthesiology. 2006;105(6):1246–1253. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200612000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berta T, Qadri YJ, Chen G, Ji RR. Microglial Signaling in Chronic Pain with a Special Focus on Caspase 6, p38 MAP Kinase, and Sex Dependence. J Dent Res. 2016;95(10):1124–1131. doi: 10.1177/0022034516653604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brennan TJ. Pathophysiology of postoperative pain. Pain. 2011;152(3 Suppl):S33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brennan TJ, Vandermeulen EP, Gebhart GF. Characterization of a rat model of incisional pain. Pain. 1996;64(3):493–501. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(95)01441-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brunner AM, Henn CM, Drewniak EI, Lesieur-Brooks A, Machan J, Crisco JJ, Ehrlich MG. High dietary fat and the development of osteoarthritis in a rabbit model. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2012;20(6):584–592. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cao J, Wang PK, Tiwari V, Liang L, Lutz BM, Shieh KR, Zang WD, Kaufman AG, Bekker A, Gao XQ, Tao YX. Short-term pre- and post-operative stress prolongs incision-induced pain hypersensitivity without changing basal pain perception. Mol Pain. 2015;11:73. doi: 10.1186/s12990-015-0077-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castoldi A, Naffah de Souza C, Camara NO, Moraes-Vieira PM. The Macrophage Switch in Obesity Development. Front Immunol. 2016;6:637. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaplan SR, Bach FW, Pogrel JW, Chung JM, Yaksh TL. Quantitative assessment of tactile allodynia in the rat paw. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 1994;53(1):55–63. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(94)90144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen G, Luo X, Qadri MY, Berta T, Ji RR. Sex-Dependent Glial Signaling in Pathological Pain: Distinct Roles of Spinal Microglia and Astrocytes. Neurosci Bull. 2018;34(1):98–108. doi: 10.1007/s12264-017-0145-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Croci T, Zarini E. Effect of the cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonist rimonabant on nociceptive responses and adjuvant-induced arthritis in obese and lean rats. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;150(5):559–566. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fillingim RB, King CD, Ribeiro-Dasilva MC, Rahim-Williams B, Riley JL., 3rd Sex, gender, and pain: a review of recent clinical and experimental findings. J Pain. 2009;10(5):447–485. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerbershagen HJ, Pogatzki-Zahn E, Aduckathil S, Peelen LM, Kappen TH, van Wijck AJ, Kalkman CJ, Meissner W. Procedure-specific risk factor analysis for the development of severe postoperative pain. Anesthesiology. 2014;120(5):1237–1245. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greenspan JD, Craft RM, LeResche L, Arendt-Nielsen L, Berkley KJ, Fillingim RB, Gold MS, Holdcroft A, Lautenbacher S, Mayer EA, Mogil JS, Murphy AZ, Traub RJ. Studying sex and gender differences in pain and analgesia: a consensus report. Pain. 2007;132(Suppl 1):S26–45. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guyenet SJ, Schwartz MW. Clinical review: Regulation of food intake, energy balance, and body fat mass: implications for the pathogenesis and treatment of obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(3):745–755. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-2525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hariri N, Thibault L. High-fat diet-induced obesity in animal models. Nutr Res Rev. 2010;23(2):270–299. doi: 10.1017/S0954422410000168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herman RM, Brower JB, Stoddard DG, Casano AR, Targovnik JH, Herman JH, Tearse P. Prevalence of somatic small fiber neuropathy in obesity. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007;31(2):226–235. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Illigens BM, Gibbons CH. A human model of small fiber neuropathy to study wound healing. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e54760. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Imai Y, Ibata I, Ito D, Ohsawa K, Kohsaka S. A novel gene iba1 in the major histocompatibility complex class III region encoding an EF hand protein expressed in a monocytic lineage. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;224(3):855–862. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Imai Y, Kohsaka S. Intracellular signaling in M-CSF-induced microglia activation: role of Iba1. Glia. 2002;40(2):164–174. doi: 10.1002/glia.10149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kanazawa H, Ohsawa K, Sasaki Y, Kohsaka S, Imai Y. Macrophage/microglia-specific protein Iba1 enhances membrane ruffling and Rac activation via phospholipase C-gamma-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(22):20026–20032. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109218200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klasen S, Hammermann R, Fuhrmann M, Lindemann D, Beck KF, Pfeilschifter J, Racke K. Glucocorticoids inhibit lipopolysaccharide-induced up-regulation of arginase in rat alveolar macrophages. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;132(6):1349–1357. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klein SL, Flanagan KL. Sex differences in immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16(10):626–638. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kroin JS, Buvanendran A, Nagalla SK, Tuman KJ. Postoperative pain and analgesic responses are similar in male and female Sprague-Dawley rats. Can J Anaesth. 2003;50(9):904–908. doi: 10.1007/BF03018737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Louis CA, Reichner JS, Henry WL, Jr, Mastrofrancesco B, Gotoh T, Mori M, Albina JE. Distinct arginase isoforms expressed in primary and transformed macrophages: regulation by oxygen tension. Am J Physiol. 1998;274(3 Pt 2):R775–782. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.274.3.R775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lumeng CN. Innate immune activation in obesity. Mol Aspects Med. 2013;34(1):12–29. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moalem G, Tracey DJ. Immune and inflammatory mechanisms in neuropathic pain. Brain Res Rev. 2006;51(2):240–264. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muntzel MS, Al-Naimi OA, Barclay A, Ajasin D. Cafeteria diet increases fat mass and chronically elevates lumbar sympathetic nerve activity in rats. Hypertension. 2012;60(6):1498–1502. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.194886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nascimento AP, Costa AM. Overweight induced by high-fat diet delays rat cutaneous wound healing. Br J Nutr. 2006;96(6):1069–1077. doi: 10.1017/bjn20061955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neil MJ, Macrae WA. Post Surgical Pain- The Transition from Acute to Chronic Pain. Rev Pain. 2009;3(2):6–9. doi: 10.1177/204946370900300203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nguyen JC, Killcross AS, Jenkins TA. Obesity and cognitive decline: role of inflammation and vascular changes. Front Neurosci. 2014;8:375. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2014.00375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Okifuji A, Hare BD. The association between chronic pain and obesity. J Pain Res. 2015;8:399–408. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S55598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ortiz VE, Kwo J. Obesity: physiologic changes and implications for preoperative management. BMC Anesthesiol. 2015;15:97. doi: 10.1186/s12871-015-0079-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patil MJ, Green DP, Henry MA, Akopian AN. Sex-dependent roles of prolactin and prolactin receptor in postoperative pain and hyperalgesia in mice. Neuroscience. 2013;253:132–141. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.08.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paz-Filho G, Mastronardi C, Franco CB, Wang KB, Wong ML, Licinio J. Leptin: molecular mechanisms, systemic pro-inflammatory effects, and clinical implications. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2012;56(9):597–607. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27302012000900001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pence BD, DiPietro LA, Woods JA. Exercise speeds cutaneous wound healing in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44(10):1846–1854. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31825a5971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pierpont YN, Dinh TP, Salas RE, Johnson EL, Wright TG, Robson MC, Payne WG. Obesity and surgical wound healing: a current review. ISRN Obes. 2014;2014:638936. doi: 10.1155/2014/638936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pollock AH, Tedla N, Hancock SE, Cornely R, Mitchell TW, Yang Z, Kockx M, Parton RG, Rossy J, Gaus K. Prolonged Intake of Dietary Lipids Alters Membrane Structure and T Cell Responses in LDLr−/− Mice. J Immunol. 2016;196(10):3993–4002. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1501261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ririe DG, Liu B, Clayton B, Tong C, Eisenach JC. Electrophysiologic characteristics of large neurons in dorsal root ganglia during development and after hind paw incision in the rat. Anesthesiology. 2008;109(1):111–117. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31817c1ab9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ryan KK, Woods SC, Seeley RJ. Central nervous system mechanisms linking the consumption of palatable high-fat diets to the defense of greater adiposity. Cell Metab. 2012;15(2):137–149. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saad MJ, Santos A, Prada PO. Linking Gut Microbiota and Inflammation to Obesity and Insulin Resistance. Physiology (Bethesda) 2016;31(4):283–293. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00041.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Salimuddin, Nagasaki A, Gotoh T, Isobe H, Mori M. Regulation of the genes for arginase isoforms and related enzymes in mouse macrophages by lipopolysaccharide. Am J Physiol. 1999;277(1 Pt 1):E110–117. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1999.277.1.E110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc. 2008;3(6):1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schultze JL, Schmieder A, Goerdt S. Macrophage activation in human diseases. Semin Immunol. 2015;27(4):249–256. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2015.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seitz O, Schurmann C, Hermes N, Muller E, Pfeilschifter J, Frank S, Goren I. Wound healing in mice with high-fat diet- or ob gene-induced diabetes-obesity syndromes: a comparative study. Exp Diabetes Res. 2010;2010:476969. doi: 10.1155/2010/476969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shen S, Lim G, You Z, Ding W, Huang P, Ran C, Doheny J, Caravan P, Tate S, Hu K, Kim H, McCabe M, Huang B, Xie Z, Kwon D, Chen L, Mao J. Gut microbiota is critical for the induction of chemotherapy-induced pain. Nat Neurosci. 2017 doi: 10.1038/nn.4606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Solomon MB, Jankord R, Flak JN, Herman JP. Chronic stress, energy balance and adiposity in female rats. Physiol Behav. 2011;102(1):84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Song XJ, Hu SJ, Greenquist KW, Zhang J-M, LaMotte RH. Mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia and ectopic neuronal discharge after chronic compression of dorsal root ganglia. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1999;82(6):3347–3358. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.6.3347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Song Z, Xie W, Chen S, Strong JA, Print MS, Wang JI, Shareef AF, Ulrich-Lai YM, Zhang JM. High-fat diet increases pain behaviors in rats with or without obesity. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):10350. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10458-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sorge RE, LaCroix-Fralish ML, Tuttle AH, Sotocinal SG, Austin JS, Ritchie J, Chanda ML, Graham AC, Topham L, Beggs S, Salter MW, Mogil JS. Spinal cord Toll-like receptor 4 mediates inflammatory and neuropathic hypersensitivity in male but not female mice. J Neurosci. 2011;31(43):15450–15454. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3859-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sorge RE, Mapplebeck JC, Rosen S, Beggs S, Taves S, Alexander JK, Martin LJ, Austin JS, Sotocinal SG, Chen D, Yang M, Shi XQ, Huang H, Pillon NJ, Bilan PJ, Tu Y, Klip A, Ji RR, Zhang J, Salter MW, Mogil JS. Different immune cells mediate mechanical pain hypersensitivity in male and female mice. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18(8):1081–1083. doi: 10.1038/nn.4053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Taves S, Berta T, Liu DL, Gan S, Chen G, Kim YH, Van de Ven T, Laufer S, Ji RR. Spinal inhibition of p38 MAP kinase reduces inflammatory and neuropathic pain in male but not female mice: Sex-dependent microglial signaling in the spinal cord. Brain Behav Immun. 2016;55:70–81. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thaler JP, Yi CX, Schur EA, Guyenet SJ, Hwang BH, Dietrich MO, Zhao X, Sarruf DA, Izgur V, Maravilla KR, Nguyen HT, Fischer JD, Matsen ME, Wisse BE, Morton GJ, Horvath TL, Baskin DG, Tschop MH, Schwartz MW. Obesity is associated with hypothalamic injury in rodents and humans. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(1):153–162. doi: 10.1172/JCI59660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thelwall S, Harrington P, Sheridan E, Lamagni T. Impact of obesity on the risk of wound infection following surgery: results from a nationwide prospective multicentre cohort study in England. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21(11):1008, e1001–1008. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Totsch SK, Quinn TL, Strath LJ, McMeekin LJ, Cowell RM, Gower BA, Sorge RE. The impact of the Standard American Diet in rats: Effects on behavior, physiology and recovery from inflammatory injury. Scand J Pain. 2017;17:316–324. doi: 10.1016/j.sjpain.2017.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Totsch SK, Waite ME, Sorge RE. Dietary influence on pain via the immune system. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2015;131:435–469. doi: 10.1016/bs.pmbts.2014.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Totsch SK, Waite ME, Tomkovich A, Quinn TL, Gower BA, Sorge RE. Total Western Diet Alters Mechanical and Thermal Sensitivity and Prolongs Hypersensitivity Following Complete Freund’s Adjuvant in Mice. J Pain. 2016;17(1):119–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2015.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang J, Zhang Q, Zhao L, Li D, Fu Z, Liang L. Down-regulation of PPARalpha in the spinal cord contributes to augmented peripheral inflammation and inflammatory hyperalgesia in diet-induced obese rats. Neuroscience. 2014;278:165–178. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.07.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Woods SC, Seeley RJ, Rushing PA, D’Alessio D, Tso P. A controlled high-fat diet induces an obese syndrome in rats. J Nutr. 2003;133(4):1081–1087. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.4.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xie W, Chen S, Strong JA, Li A-L, Lewkowich IP, Zhang J-M. Localized sympathectomy reduces mechanical hypersensitivity by restoring normal immune homeostasis in rat models of inflammatory pain. J Neurosci. 2016;36(33):8712–8725. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4118-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xie W, Strong JA, Kim D, Shahrestani S, Zhang JM. Bursting activity in myelinated sensory neurons plays a key role in pain behavior induced by localized inflammation of the rat sensory ganglion. Neuroscience. 2012;206:212–223. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xie W, Strong JA, Ye L, Mao JX, Zhang J-M. Knockdown of sodium channel NaV1. 6 blocks mechanical pain and abnormal bursting activity of afferent neurons in inflamed sensory ganglia. Pain. 2013;154:1170–1180. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.02.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xie W, Strong JA, Zhang JM. Local knockdown of the NaV1. 6 sodium channel reduces pain behaviors, sensory neuron excitability, and sympathetic sprouting in rat models of neuropathic pain. Neuroscience. 2015;291:317–330. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Xie W, Strong JA, Zhang JM. Active Nerve Regeneration with Failed Target Reinnervation Drives Persistent Neuropathic Pain. eNeuro. 2017;4(1) doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0008-17.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang J-M, Song XJ, LaMotte RH. Enhanced excitability of sensory neurons in rats with cutaneous hyperalgesia produced by chronic compression of the dorsal root ganglion. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1999;82(6):3359–3366. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.6.3359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang X, Goncalves R, Mosser DM. The isolation and characterization of murine macrophages. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2008;Chapter 14(Unit 14):11. doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im1401s83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zheng H, Schnabel A, Yahiaoui-Doktor M, Meissner W, Van Aken H, Zahn P, Pogatzki-Zahn E. Age and preoperative pain are major confounders for sex differences in postoperative pain outcome: A prospective database analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(6):e0178659. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0178659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zobel EH, Hansen TW, Rossing P, von Scholten BJ. Global Changes in Food Supply and the Obesity Epidemic. Curr Obes Rep. 2016;5(4):449–455. doi: 10.1007/s13679-016-0233-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.