Abstract

The activation of NLRP3 inflammasome in innate immune cells is associated with enhanced production of pro-inflammatory lipid mediator eicosanoids that play a crucial role in propagating inflammation. Gamma-tocotrienol (γT3) is an unsaturated vitamin E that has been demonstrated to attenuate NLRP3-inflammasome. However, the role of γT3 in regulating eicosanoid formation is unknown. We hypothesized that γT3 abolishes the eicosanoid production by modulating the macrophage lipidome. LPS-primed bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM) were stimulated with saturated fatty acids (SFA) along with γT3, and the effects of γT3 in modulating macrophage lipidome were quantified by using mass spectrometry based-shotgun lipidomic approaches. The SFA-mediated inflammasome activation induced robust changes in lipid species of glycerolipids (GL), glycerophospholipids (GPL), and sphingolipids in BMDM, which were distinctly different in the γT3-treated BMDM. The γT3 treatment caused substantial decreases of lysophospholipids (LysoPL), diacylglycerol (DAG), and free arachidonic acid (AA, C20:4), indicating that γT3 limits the availability of AA, the precursor for eicosanoids. This was confirmed by the pulse-chase experiment using [3H]-AA, and by diminished prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) secretion by ELISA. Concurrently, γT3 inhibited LPS-induced cyclooxygenases 2 (COX2) induction, further suppressing prostaglandin synthesis. In addition, γT3 attenuated ceramide synthesis by transcriptional downregulation of key enzymes for de novo synthesis. The altered lipid metabolism during inflammation is linked to reduced ATP production, which was partly rescued by γT3. Taken together, our work revealed that γT3 induces distinct modification of the macrophage lipidome to reduce AA release and corresponding lipid mediator synthesis, leading to attenuated cellular lipotoxicity.

Keywords: gamma tocotrienol, NLRP3 inflammasome, lipidomics, arachidonic acid, eicosanoids, PGE2

1. Introduction

Obesity and insulin resistance are regarded as inflammatory diseases in which NFκB activation orchestrates the innate immune responses [1, 2]. Aberrant NFκB activation and proinflammatory cytokine secretion are important regulators for pathogenic progression of obesity. Nod-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome is an innate immune effector that recognizes molecular patterns of dangerous signals to maturate and secrete cytokines IL-1β and IL-18 [3]. In addition to pathogen-associated molecular patterns, NLRP3 inflammasome assembly is activated by damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) such as free fatty acids (FFA) [4]. The elevated levels of FFA, arising from either the lipolysis of inflamed adipose tissue or excessive dietary intake, serve as a key DAMP signal to instigate NLRP3 inflammasome in adipose tissue macrophages (ATM), thereby perpetuating lipotoxicity [5].

In addition to the release of cytotoxic cytokines such as IL-1β, activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in ATM is accompanied by large quantities of lipid mediator production including eicosanoids and ceramides, which propagates the metabolic damages to systemic level via autocrine and paracrine signaling [6]. It is proposed that NFκB activation alters lipid profiles in macrophages [7, 8], albeit it has not been completely understood regarding the role of FFA in modulating the proinflammatory lipid mediators in macrophages. Understanding the interplay between lipotoxicity-mediated NLRP3 inflammasome activation and synthesis of lipid mediators may provide insights into the pathogenic progression of obesity to type 2 diabetes.

Gamma-tocotrienol (γT3) is an unsaturated form of vitamin E that has been demonstrated to attenuate adipose inflammation and obesity-induced insulin resistance [9]. Accumulating lines of evidence showed that γT3 inhibits NFκB activation in innate immune cells such as macrophages as well as metabolic cells such as adipocytes and hepatocytes [10, 11]. Recently, our group reported the immunomodulatory role of γT3 demonstrating that γT3 suppresses NLRP3 inflammasome in cultured macrophages as well as ATM in diabetic leptin receptor knockout mice (DB) [12]. Given the fat-soluble nature of γT3 and its potential to modify signaling in cell membranes, it is speculative that γT3 may exert direct roles in altering lipid metabolism in macrophages in favor of attenuated synthesis of pro-inflammatory lipid mediators. Hitherto, γT3 has been shown to decrease ceramide production by inhibiting the dihydroceramide desaturase activity in cancerous cells [13]. However, it is largely unknown whether γT3 has a potential to alter macrophage lipidome, especially in conditions of SFA-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation.

The aim of this study is to investigate the role of γT3 in regulating the production of lipid mediators in macrophages under the NLRP3 inflammasome-stimulated conditions by endotoxin LPS in combination with palmitate, C16:0 saturated fatty acid (SFA). By using lipidomic approaches, we identified that γT3 significantly alters arachidonic acid (AA) and sphingolipid metabolism in macrophages, resulting in reduced eicosanoid production and protection of energy metabolism from aberrant immune response-mediated metabolic damages.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

Gamma-tocotrienol (γT3; with 90% purity) was kindly provided by Carotech (Edison, NJ, USA). γT3 was prepared as previously described [12]. Pam3CSK4, a TLR2 agonist, was purchased from R&D Systems. All other chemicals and reagents were purchased from Sigma Chemical unless otherwise stated.

2.2. Preparation of bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM)

Primary bone marrows were isolated from 6-week-old C57BL/6 mice (Jackson Laboratory) as we conducted previously [10]. All animal experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Ca1re and Use Committee at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Briefly, bone marrows were obtained by flushing the femur, and the cells were suspended and cultured in DMEM containing 20% FBS, penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml), in the presence of 30 % L929-cell conditioned medium containing monocyte stimulating factor. Differentiated macrophages (BMDM, unstimulated, M0) were allowed to attach and form a monolayer for 7–10 days [14].

2.3. Activation of NLRP3 inflammasome

The differentiated bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) were pretreated with either 1μM of γT3 or vehicle (DMSO) for 24 hours. BMDM were first primed with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (100 ng/ml) for 1 hour, and with palmitic acid (400 μM) for 12 hours to activate NLRP3 inflammasome (LPS/pal). For separate activation of toll like receptor 2 (TLR2) and 4 (TLR4), BMDM were stimulated with pharmacological agonist of Pam3CSK4 (200 ng/mL, R&D systems) or KLA (100 ng/mL, Sigma), respectively.

2.4. Shotgun lipidomics study using LC-MS/MS

After stimulation of NLRP3 inflammasome, BMDMs (10 × 106) were harvested with ice-cold HBSS and pelleted for keeping in −80 °C until lipid profile analysis. Two hundred μL of cell suspension were used for protein quantification, and 800 μL of suspension were analyzed with an LC-MS/MS (AB Sciex TripleTOF 5600 system). The data was processed using the software Peakview & lipidview. All data were normalized to mg protein. A detailed description of this method has been previously described [15].

2.5. qPCR

Gene expression levels were measured using real-time qPCR [12]. Gene-specific primers for real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) were synthesized from Integrated DNA Technologies (Chicago, IL, USA). Total RNA were isolated with Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). To remove the potential genomic DNA contamination, mRNA will be treated with DNase (DNAase free kit, Invitrogen), and 2 μg of mRNA were converted into cDNA in a total volume of 20 μL (iScript cDNA synthesis kit, Bio-Rad). Gene expression was determined by real-time qPCR (QuantStudio 6 Flex Real-Time PCR, Applied Biosystem) using SYBR green (Fisher scientific), and relative gene expression were normalized to the average of reference gene, hypoxanthine guanine phosphoribosyltransferase (Hprt).

2.6. Measurement of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2)

To measure PGE2 levels, BMDMs were stimulated with LPS/palmitate for 12 hours and medium was collected, centrifuged to remove cell debris, and used for measurement of PGE2 by ELISA kit (Cayman chemical, #514010) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.7. [3H]-radiolabeled Arachidonic acid (AA) release

To measure the Arachidonic acid (AA) release, we used the pulse-chase metabolic chasing method according to the published protocol [16]. The AA [5,6,8,9,11,12,14,15-3H(N)] was purchased from PerkinElmer. Briefly, BMDMs were plated at a density of 0.5 ×106 million/per well in 6-well plate and incubated overnight at 37 °C in a humidified incubator. The cells were pretreated with or without 1 μM of γT3 for 12 hours, then incubated [3H]-AA (0.5 μCi/1mL/well) for 18 h at 37 °C for loading. The cells were washed three times with 2 mg/mL of bovine serum albumin in phosphate-buffered saline to remove unincorporated [3H]-AA, followed by NLRP3 inflammasome stimulation using LPS/palmitate as described in 2.3. After 6 hours of NLRP3 inflammasome activation, released [3H]-AA to the culture medium was collected, centrifuged to remove cell debris, and used for measurement of [3H] radioactivity by liquid scintillation counter (Tri-carb 2900TR liquid scintillation analyzer, Perkin Elmer).

2.8. Measurement of mitochondrial respiration and glycolysis

The Mito Stress tests were conducted to measure basal respiration, maximal respiration, and ATP production in BMDM by using XFe24 extracellular flux analyzer (Seahorse) as we described previously [17]. Briefly, macrophages were seeded in gelatin-coated seahorse microplates, and pretreated with or without 1 μM of γT3 for 24 hrs. The Oxygen consumption rate (OCR) was calculated by plotting the O2 tension of the medium in the microenvironment above the cells as a function of time (pmol of O2/min). Glycolysis Stress tests were conducted to measure glycolysis, glycolytic capacity, and glycolytic reserve under the same conditions for mitochondrial respiration using the BMDM. The Extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) was calculated by measuring the acidity of the medium above the cells as a function of time (mpH/min). Once the assay was finished, total the protein was collected from each well and used to normalize the data.

2.9. Western Blot Analysis

For Western blot analysis, total cell extract of BMDM were prepared [12]. The antibodies recognizing phospho(p)-cPLA(Ser505), and Iκ-Bα were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

The heat map production and principal component analysis (PCA) were performed with JMP software (SAS Institute Inc. Cary, NC, USA). The heatmap was depicted with every row for each lipid species and the relative abundance data were auto-scaled for multivariate analyses. From the green to red, it represents low to high concentration of each lipid profile. In PCA analysis, the data was transformed from the original variables to principal components. For the statistical analyses of two-group comparisons, two-tailed Student’s t-test was used. P values less than 0.05 (P<0.05) were considered significant. The values were expressed as mean ± SEM. Analysis for multi-group comparisons were performed by a one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6 (version 6.02).

3. Results

3.1. Shotgun lipidomic analysis revealed that γT3 distinctively modifies macrophage lipidome against SFA-induced NLRP3 inflammasome

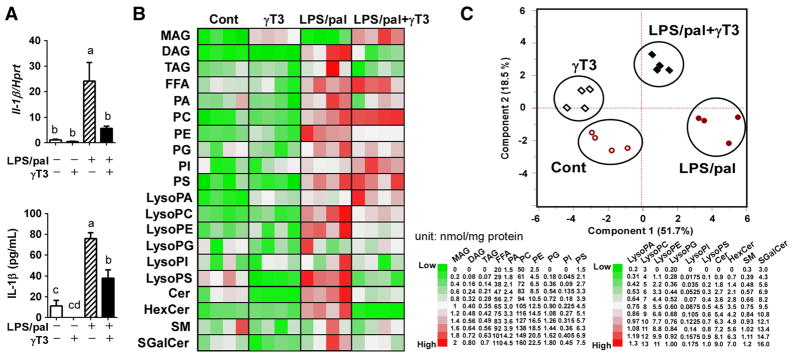

To gain an insight into whether SFA-driven inflammasome activation alters macrophage lipid metabolism and to determine the potential role of γT3, LPS-primed BMDM were stimulated with palmitate (LPS/pal) in the presence or absence of γT3 (1μM). Before the lipidomics assay, the suppression of NLRP3 inflammasome activation by γT3 was confirmed by IL-1β gene expression and secretion to the medium (Fig 1A). Lipidomic analyses were performed in both unstimulated conditions (Cont vs. γT3) and NLRP3 inflammasome-stimulated conditions (LPS/pal vs. LPS/pal+γT3). By using 14 internal standard lipids, shotgun lipidomic analyses resulted in the identification of total 209 lipid species from the major 20 (sub) classes. The heatmap visualization of the distribution of the different lipid classes (by summing the individual lipid species) demonstrated that LPS/pal stimulation robustly promoted the synthesis of the majority of lipid classes in inflammasome-stimulated BMDM (LPS/pal) compared to unstimulated control (Cont) (Fig 1B). To gain an initial overview, multivalent principal component analysis (PCA) relative to the lipid composition was performed. As we expected, PCA with compositional data resulted in a pronounced separation of unstimulated and LPS/pal-stimulated BMDM. More importantly, there was a distinct γT3-dependent difference in the lipid profiles of BMDM in both unstimulated as well as LPS/pal-stimulated conditions (Fig 1C). Collectively, these results suggest that γT3 significantly modulates cellular lipid profiles and the magnitude of lipid profile differences was more evident in NLRP3 inflammasome-stimulated conditions in the primary murine BMDM.

Figure 1. γT3 distinctively modulated macrophage lipidome against SFA-induced NLRP3 inflammasome.

Bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDM) were stimulated for NLRP3 inflammasome by LPS/pal with or without γT3 pretreatment. Then, the total cellular lipids were extracted and subjected to LC-MS/MS for shotgun lipidomic analysis. (A) IL-1β gene expression and its secretion to medium were measured in the same samples for lipidomic analysis by qPCR and ELISA, respectively (n=6 per group). (B) Heatmap representation of the lipid profile changes in response to LPS/pal stimulation with or without γT3 treatment (n=4 each group). The content of each lipid (nmol/mg protein) was color-coded from green (low) to red (high). Ranges of lipid classes were placed to the right. (C) Principal component analysis (PCA) scatterplot obtained from shotgun LC-MS/MS spectra of BMDM lipid extracts. Values are presented as mean ± SEM in (A). Bars with different letters are significantly different (a>b>c, P<0.05) by one-way ANOVA. Abbreviation used: FFA: free fatty acids, MAG: monoacylglyceride, DAG: diacylglyceride, TAG: triacylglyceride, PA: phosphatidic acid, PC: phosphatidyl choline, PE: phosphatidyl ethanolamine, PG: phosphatidyl glycerol, PI: phsphatidyl inositol, PS: phosphatidyl serine, LPA: lysophosphatidic acid, LPC: lysophosphatidyl choline, LPE: lysophosphatidyl ethanolamine, LPG: lysophosphatidyl glycerol, LPI: lysophosphatidyl inositol, LysoPS: lysophosphatidyl serine, Cer: Ceramide, HexCer: hexosyl ceramide, SM: sphingomyelin, SGalCer: sulfategalactosylceramide

3.2. γT3 suppressed AA formation in BMDM against palmitate-induced inflammasome

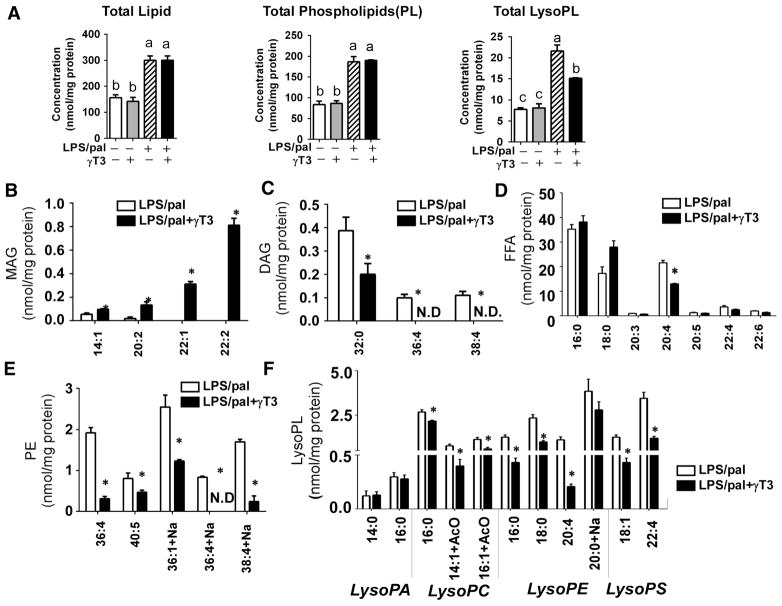

Regardless of γT3 treatment, the increase of total phospholipid (PL) content was phenomenal in response to LPS/pal stimulation, suggesting that palmitate is incorporated into PL. However, the total lysophospholipids (LysoPL) were significantly lower in γT3-received BMDM than LPS/pal alone (Fig 2A). To identify the individual lipid distinguishing the impact of γT3 in response to SFA-mediated NLRP3 inflammasome, we compared lipid composition between LPS/pal and LPS/pal+γT3. Interestingly, monoacylglycerol (MAG) content was higher in the presence of γT3, and the magnitude was further increased by LPS/pal especially in 14:1, 20:2, 22:1, and 22:2 MAG (Fig 2B). In contrast, there was an opposite trend in diacylglycerol (DAG) regulation. LPS/pal stimulation dramatically induced the 32:0, 36:4 and 38:4 DAG in BMDM, which were dampened by γT3 treatment (Fig 2C). Although there was no difference in total FFA level, arachidonic acid (AA, 20:4) content was significantly reduced with γT3 treatment (Fig 2D). Among the PL classes, phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) levels, but not phosphatidylcholine (PC), were significantly lower in the presence of γT3 especially in 36:4, 40:5, 36:1, and 38:4 PE (Fig 2E). Consequently, PC/PE ratio was significantly lowered in LPS/pal than LPS/pal+γT3 (data not shown). It is also noteworthy that increased levels of LysoPL during NLRP3 inflammasome activation were significantly reduced in γT3-treated BMDM in the major species of lysophosphatidyl choline (16:0, 14:1, 16:1 LysoPC), lysophosphatidyl ethanolamine (16:0, 18:0, 20:4, 20:0 LysoPE), and lysophosphatidyl serine (18:1, 22:4 LysoPS) (Fig 2F).

Figure 2. γT3 altered the specific lipid profiles of DAG, LysoPL, PE, and arachidonic acid in NLRP3-inflammasome stimulated BMDM.

BMDMs were stimulated with LPS/palmitic acid, and lipidomic analyses were performed using LC-MS/MS. (A) Concentrations of total lipid, total phospholipids (PL), and total Lysophospholipids (LysoPL). Changes in lipid species in monoacylglycerol (MAG) (B), Diacylglycerol (DAG) (C), Free fatty acids (FFA) (D), Phosphatidyl ethanolamine (E), Lysophospholipids (LysoPL) (F) in NLRP3 inflammasome-stimulated BMDM without (white) or with γT3 (black) treatment. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n= 4). Bars with different letters are significantly different (P<0.05) by one-way ANOVA in A. *P<0.05 (LPS/pal vs. LPS/pal+γT3) by student’s t-test in B-F.

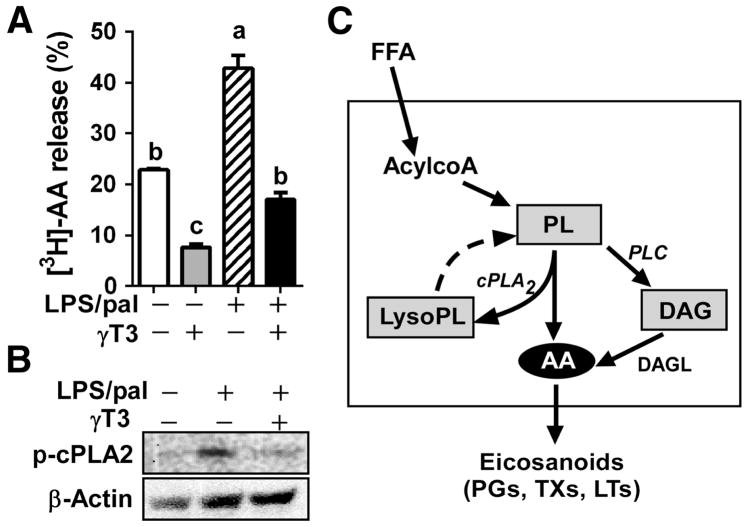

Given that AA release is a rate-limiting step for proinflammatory eicosanoid synthesis, we further examined the direct effects of γT3 on AA release by using 3[H]-AA as a molecular probe. BMDM were first incubated with [3H]-AA in the absence or presence of γT3 for membrane loading. After removing unincorporated AA, BMDM were stimulated by LPS/pal for 6 hours, and the medium was collected to measure the released radiolabeled-AA and its metabolites. There was no significant difference in 3[H]-AA loading to the BMDM between two groups (data not shown). However, the release of 3[H]-AA and its metabolites were markedly lower in the presence of γT3 (Fig 3A). In addition, the LPS/pal-induced phosphorylation of cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2) (Ser505), a sign for cPAL2 activation, was significantly reduced by γT3 (Fig 3B). This result implicate that γT3 considerably represses inflammation-mediated AA release by diminishing the membrane PL hydrolysis via cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2) resulting in reduced lysophosphatidic acid (lysoPA) and AA release. In combination with lipidomic data (Fig 1 and 2), these results suggest that γT3 reduces AA release from membrane PL via mechanisms in which γT3 1) diminishes cPLA2-mediated membrane PL hydrolysis resulting in reduced lysophosphatidic acid (lysoPA) and AA levels, and 2) inhibits DAG formation from the de-phosphorylation of phosphatidic acid (PA), presumably due to reduced phospholipase C activation (Fig 3C).

Figure 3. γT3 attenuated the release of free AA and its metabolites in the inflammasome-stimulated BMDM.

(A) BMDMs were loaded with [3H]-AA overnight before stimulation with LPS/pal for 6 hours, then the release of AA and its metabolites to the medium was quantified by [3H]-radioactivity. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Bars with different letters are significantly different (P<0.05) by one-way ANOVA. (B) Western blot analysis of phosphor-cPLA2 as a marker for cPLA2 activation. (C) Schematic diagram to explain the arachidonic acid (AA) generation in FFA-stimulated inflammatory conditions. The exogenous FFA will be activated to acyl CoA and incorporated into PL. Subsequently, PL are hydrolyzed to LysoPL and AA by cPLA2 (de-acylation), or de-phosphorylated into DAG by PLC. Dotted line is showing the regeneration of PL from AA (re-acylation) in the unstimulated conditions. The increased levels of AA are used for production of eicosanoids.

3.3. γT3 reduced prostaglandin E2 production by blocking cyclooxygenase 2 induction in BMDMs

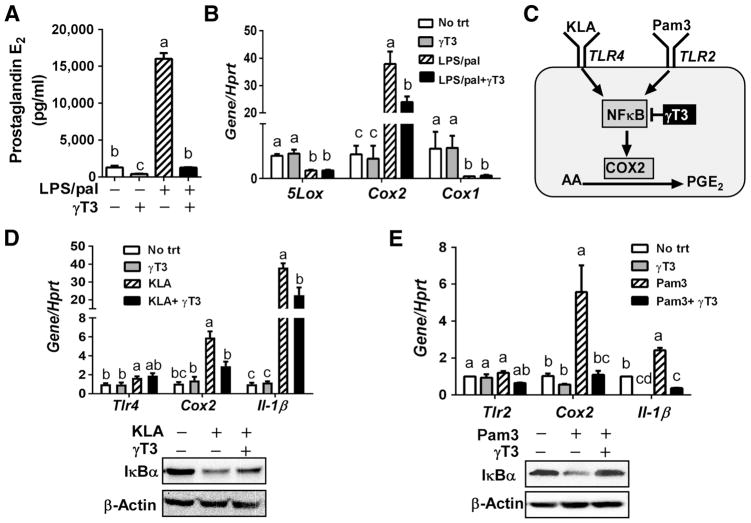

Eicosanoids include prostaglandins, thromboxanes (TXs), and leukotrienes (LTs). Prostaglandins and TXs, which are generated by the two isoforms of cyclooxygenases (COX), COX-1 and COX-2, whereas LTs are generated by 5-lipoxygenase (5-LOX). We quantified prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) levels from the BMDM medium that was used for lipidomic analysis in Fig 1. The activation of inflammasome led to a dramatic secretion of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), which was abolished by γT3 comparable to unstimulated levels (Fig 4A). Consistent with PGE2 secretion, there was over 40-fold induction of Cox2 gene expression upon inflammasome activation, while it was reduced to approximately to half in the presence of γT3. However, Cox1 and 5-Lox were not increased by LPS/pal-induced inflammasome conditions (Fig 4B), suggesting that production of prostaglandins by COX2 is the major constituent for eicosanoid storms in response to LPS/pal stimulation.

Figure 4. γT3 attenuated Cox2 induction in BMDM against toll-like receptor agonist 2 and 4.

Bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDM) were stimulated for NLRP3 inflammasome by LPS/pal with or without pretreatment of γT3. (A) PGE2 secretion to the medium by ELISA. (B) mRNA expression levels of Cox1, Cox2 and 5Lox upon LPS/pal stimulation. (C) Schematic representation to explain the inhibition of TLR2/4-NFκB axis by γT3 resulting in decreased Cox2 induction and corresponding PGE2 production. (D) mRNA expressions of Cox2, Tlr4 and Il-1β upon stimulation with KLA (100ng/mL), TLR4 agonist, for 3hr. (E) mRNA expressions of Cox2, Tlr2, and Il-1β upon stimulation with Pam3Csk4 (200ng/mL), TLR2 agonist. (Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n=3). Bars with different letters are significantly different (P<0.05) by one-way ANOVA.

It is known that COX2 is induced by toll-like receptor (TLR)/NFκB pathways [18]. To tease out the separate role of γT3 on TLR2 and TLR4-mediated COX2 activation, BMDM were either stimulated with Kdo2 lipid A (KLA), a TLR4-specific agonist, or Pam3CSK4 (Pam3), a TLR2-specific agonist (Fig 4C). The increase of Cox2 and Il-1β by both KLA and Pam3 was significantly suppressed by γT3 comparable to the unstimulated levels (Fig 4D, E). As we expected, γT3 treatment significantly reduced KLA and Pam3-induced IκBα degradation (Fig 4D, E). These results suggest that γT3 inhibits TLR2/NFκB signaling axis as well as TLR4/NFκB, thereby synergistically reducing COX2 induction and corresponding PGE2 formation.

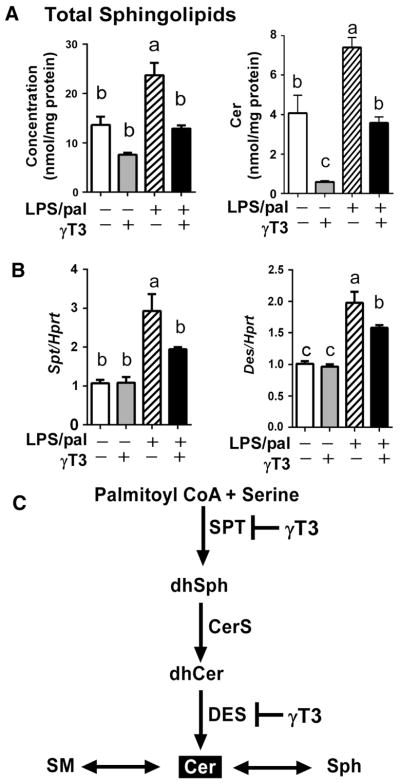

3.4. γT3 suppressed the NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated ceramide synthesis

Sphingolipids (SL) are crucial lipid mediators of inflammatory diseases [19, 20]. The lipidomic analysis showed that total SL [sums of Ceramide (Cer), hexosyl-ceramide (HexCer), sulfategalatosyl-ceramide (SGalCer), and sphingomyelin (SM)], as well as ceramide alone, were significantly increased in NLRP3 inflammasome-stimulated BMDM. This effects were reversed by γT3 pretreatment (Fig 5A, B). The gene expression levels of key enzymes for de novo synthesis of ceramide were measured using qPCR. The inflammasome-induced mRNA transcripts of serine-palmitoyltransferase (Spt) and dihydroceramide desaturase (Des) were significantly lower in γT3-treated BMDM than Control (Fig 5C). Combining the results from lipidomic analysis and qPCR, it is suggestive that palmitate-induced inflammasome promotes de novo ceramide synthesis, which is attenuated by γT3 partly through the transcriptional suppression of key enzymes for ceramide biosynthesis (Fig 5D).

Figure 5. γT3 modulated sphingolipid metabolism in the inflammasome-stimulated BMDM.

(A) The cellular content of total SPL and Cer. (B) The mRNA levels of key enzymes for Ceramide biosynthesis, serine palmitoyl transferase (Spt) and dihydroceramide desaturase (Des). (C) The schematic presentation to show γT3 decreases the de novo ceramide formation by transcriptional repression of key Spt and Des. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Bars with different letters are significantly different (P<0.05) by one-way ANOVA. CerS, ceramide synthase; DES, dihydroceramide desaturase; dhCer, dihydroceramide; dhSph, dihydrophingosine; sph, sphingosine; SPT, serine palmitoyltransferase; SM, sphingomyelin.

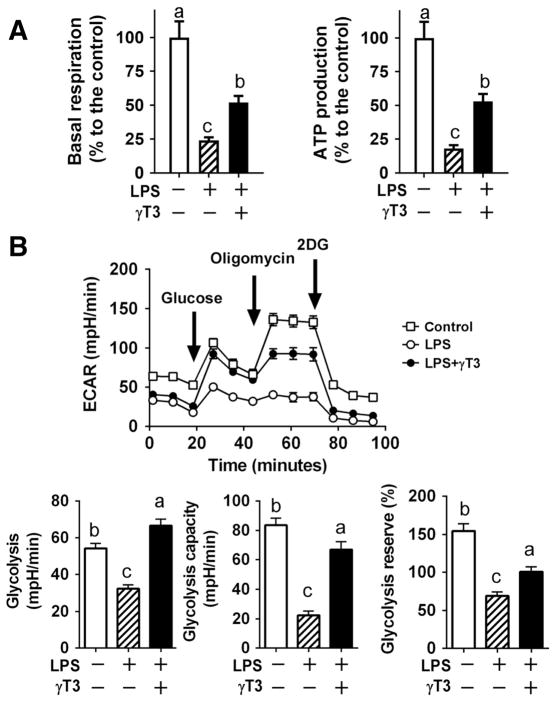

3.5. γT3 protected from inflammation-mediated impairment of energy metabolism

Emerging evidence suggests that energy-sensing mechanisms are linked with immunity. The reduced ATP production in innate immune cells triggers innate immune responses including NLRP3 inflammasome activation in macrophages [21, 22]. Next, we hypothesized that reduced inflammation and lipid remodeling by γT3 help maintain the energy production capacity of macrophages, contributing to suppression of excessive immune responses. The LPS-stimulation impaired respiration rate and dampened mitochondrial ATP production. In contrast, γT3-treated BMDM were able to maintain mitochondrial function and rescue the mitochondrial ATP production ~50 % (Fig 6A). Similarly, LPS-stimulation substantially decreased glycolytic functions, while γT3 treatment help maintains glycolytic function comparable to unstimulated macrophages (Fig 6B). These results led us to speculate that the unique lipidomic signature modulated by γT3 (e.g., decreased AA release) may contribute to maintaining energy homeostasis by protecting glycolytic and mitochondrial function.

Figure 6. γT3 attenuated LPS-induced metabolic dysfunction in BMDM.

BMDM treated with either vehicle, LPS, or LPS plus γT3. (A) Changes in basal respiration rate and ATP production measured by Seahorse XF analyzer (average of three separate experiments, n=5/experiment). (B) Glycolytic flux measured by Seahorse analyzer. Arrow indicates the addition of glucose, oligomycin, 2-deoxyglucose (2DG) (upper). The basal and oligomycin-stimulated glycolysis, and reserved glycolysis (%) were calculated (lower). Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n=6 per group). Bars with different letters are significantly different (P<0.05) by one-way ANOVA.

4. Discussion

Inflamed adipose tissue is a reservoir of FFA that serves as a potent DAMP signal to instigate NLRP3 inflammasome in ATM. The activation of inflammasome accompanies a massive production of lipid mediators, so-called eicosanoid storm [23, 24]. This study is designed to define the changes of macrophage lipidome by γT3 in the SFA-stimulated NLPR3 inflammasome. Here, we demonstrated that γT3 substantially modulates inflammasome-mediated lipid profiles in BMDM (Fig 1, 2), inhibiting AA release (Fig 3) and suppressing COX2 induction and subsequent PGE2 production (Fig 4). Our work also showed that γT3 was effective in decreasing ceramide formation against excess SFA-stimulated inflammasome (Fig 5). Moreover, γT3 at least partly reversed the inflammation-mediated impairment of mitochondrial and glycolytic function (Fig 6). This work demonstrated that γT3 suppresses the aberrant production of pro-inflammatory lipid mediators and protects the energy metabolism of macrophages against SFA-driven NLPR3 inflammasome.

In this study, we focused on lipidomic changes caused by γT3 in the unstimulated and NLRP3 inflammasome-stimulated BMDM. In the unstimulated conditions, changes of lipidome by γT3 were negligible except MAG content. The overall content of MAG was fairly low in both basal and stimulated BMDM. In contrast, γT3 treatment promoted MAG levels even in unstimulated conditions, which was further augmented by inflammasome-stimulated conditions (Fig 1B, 2B). There is increasing knowledge that monoacylglycerol lipase (MAGL) is an important regulator of simultaneous prostaglandins synthesis [25]. Additionally, MAGL can hydrolyze endocannabinoid 2-arachidonoyl glycerol (2-AG) yielding glycerol and AA, which further metabolizes into prostaglandins [26, 27]. Based on this, we assumed γT3 might play a role as MAGL inhibitor, thereby accumulating MAG but decreasing AA production. Unfortunately, it is unlikely because we found Magl message levels were very low, and they were not increased by γT3 treatment (data not shown). Currently, it is uncertain whether the increased content of MAG is a part of the anti-inflammatory mechanism of γT3 or metabolic side effects unrelated with inflammation. Further research is warranted to determine the exact role of increased MAG by γT3 in macrophages regarding metabolic and immunological consequences.

In our experimental setting, γT3 treatment has minimal effects on FFA activation of acyl CoA or its conversion into PL, as we did not see any differences in the total content of GPL. Importantly, the most conspicuous change by γT3 was the modulation of AA metabolism. Despite no difference of total FFA content, free AA content was significantly lower in γT3-treated BMDM (Fig 2D). It is well known that availability of free AA is a rate-limiting step for eicosanoids production in innate immune cells [28]. The AA levels are modulated by two opposing reactions, phospholipid de-acylation by cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2) and re-acylation back into phospholipid by lysophospholipid acyltransferase (LPLAT) [29]. In the stimulated conditions, cPLA2-mediated de-acylation dominates over re-acylation, resulting in elevated levels of free AA, while the availability of AA is limited in unstimulated conditions due to dominant re-acylation reaction [29]. In the presence of γT3, there were marked reductions in LysoPL as well as free AA (Fig 1, 2F), suggesting that γT3 suppressed the LPS/pal-induced cPLA2 activation and its enzymatic action to hydrolyze PL into LysoPL and AA. It is reported that cPLA2 levels are decreased by α-tocotrienol in neuronal cells [30]. However, it was unknown whether γT3 inhibits cPLA2 activation in innate immune cells. Here, we provided the first evidence that γT3 decreases cPLA2 activation against inflammation in macrophages (Fig 3B). Moreover, γT3 treatment dampened the increase of DAG, another source of AA, suggesting the possibility that γT3 may inhibit the phospholipase C (PLC) action to dephosphorylate PL into DAG. Although further verification is required to determine whether γT3 inhibits cPLA2 and/or PLC, we demonstrated that γT3 decreased the substrate availability for eicosanoids by limiting AA release (Fig 3, 4).

The released AA from membrane PL is subsequently metabolized to form a wide variety of oxygenated metabolites (eicosanoids) including prostaglandins and TXs by cyclooxygenase (COX), and LTs by lipoxygenase (LOX). The uncontrolled formation of eicosanoids upon stimulation with FFA-mediated inflammation can be self-destructive and lead to irreversible damage [31]. In addition to reduced AA, we examined that γT3 inhibits induction of Cox2 (Fig 4B). Consistent with our results, there are lines of evidence that γT3 suppresses Cox2 expression in Raw macrophages [32, 33] likely through inhibition of NFκB activation (reviewed in [34]). In fact, NFκB signaling is the most critical and common denominator for both priming of the NLRP3 inflammasome and proinflammatory eicosanoid production. By using the agonists specific to TLR2 and 4 (Fig 4D and E), our results reinforce the notion that γT3 attenuates the TLR2/TLR4-NFκB signaling axis activation, resulting in reduced NLRP3 inflammasome activation as well as proinflammatory eicosanoid production.

It is notable that emerging research indicates the positive feedback loop between biosynthesis of PGE2 and innate immune responses; 1) the inhibition of COX2 activity by Celecoxib abolished NLRP3 inflammasome activation [35], and 2) the enhanced COX2 activity and PGE2 production are required for priming of pro-IL-1β [36]. Considering this intimate relationship, the ability of γT3 to decrease PGE2 production may be a fundamental mechanism that γT3 inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome activation. In addition to the reduced NFκB activation, AA release, and PGE2 production, other lipidomic changes induced by γT3 may contribute to attenuation of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. In support of our notion, Scholz et al. proposed that an increase of LysoPC triggers caspase-1 activation and NLRP3 inflammasome activation in microglia [37]. Based on this study, decreased LysoPC by γT3 could be an additional mechanism to downregulate NLRP3 inflammasome activation.

It has been demonstrated that TLR4 signaling in combination with palmitate upregulates ceramide synthesis [38]. As we expected, ceramide content was considerably increased by combined stimuli of LPS/pal in our experimental setting, while γT3 significantly decreased ceramide content in both basal and stimulated conditions (Fig 1B, 5A). It is consistent with the reports that γT3 inhibits de novo synthesis of ceramide by inhibiting the dihydroceramide desaturase activities in various cancer cells without altering mRNA levels [13, 39, 40]. Unlike the previous cancer cell studies, γT3 significantly downregulated the LPS/pal-induced transcriptional augmentation of serine-palmitoyl transferase and dihydroceramide desaturase in BMDM (Fig 5B). Although the crosstalk of sphingolipids and inflammasome has been well-known [41], the role of ceramide in regulating obesity-mediated inflammasome is controversial; Camell et al. showed that de novo synthesis of ceramide is not necessary for inflammasome-driven inflammation and insulin resistance [42]. By using the primary BMDM, we demonstrated that γT3 can decrease SFA-mediated ceramide formation by transcriptional activation, but its impact on macrophage metabolism and immunity may require further verification.

The energy sensing mechanism is intertwined with immune responses in innate immune cells such as macrophages [21, 22]. In our studies, γT3 treatment was effective in sustaining ATP production capacity against inflammation (Fig 6). We propose that protection of energy metabolism in macrophage would be another important mechanism by which γT3 suppresses aberrant innate immune responses. The PC and PE are the two major PL, and PC/PE ratio is critical index for membrane integrity. The decreased PC/PE ratio, due to an ineffective conversion of PE to PC and the corresponding accumulation of PE, promotes membrane permeability and influences energy metabolism [43, 44]. In this regard, we had the very interesting observation that PC/PE molar ratio was significantly different in the presence of γT3; PC/PE ratio was decreased upon LPS/pal stimulation from 10.4±0.5 (unstimulated) to 8.3±1.9 (LPS/pal). In contrast, γT3-treatment decreased PE content (PE) recovering the PC/PE ratio similar to the unstimulated range, 11.0 ± 0.6 (Fig 1, 2E). We speculate that reduced PC/PE ratio in the inflamed macrophage is responsible for reduced glycolytic flux and mitochondrial ATP production, which was partly rescued by γT3. Although more research is warranted to identify the molecular targets to explain the specific reduction of PE by γT3, our study provides insights into γT3-mediated lipidomic changes, energy metabolism, and innate immunity.

In summary, shotgun lipidomic analysis revealed that γT3 not only suppresses cytokine IL-1β secretion but also interferes with lipid remodeling for eicosanoid production in BMDM. Moreover, γT3 protects energy metabolism against inflammation, maintaining the ATP production capacity. Our results implicate that γT3 possesses the translational potential to prevent and/or delay the pathogenic progression from obesity to type 2 diabetes by preventing pyroptotic cell death and disconnecting the propagation of lipotoxic damages. Based on our study, the inclusion of γT3 as personalized medicine may be useful for those who are obese and susceptible to obesity-driven type 2 diabetes.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by American Heart Association SDG grant to S.C. (13SDG14410043), USDA-Hatch grant at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, and National Institutes of Health grants R01 HL122283 and P50 AA024333 (J.M.B.). Development of lipid mass spectrometry methods reported here were supported by generous pilot grants from the Clinical and Translational Science Collaborative of Cleveland (4UL1TR000439) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) component of NIH and the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research, the Case Comprehensive Cancer Center (P30 CA043703), the VeloSano Foundation, and a Cleveland Clinic Research Center of Excellence Award.

Abbreviations

- AA

arachidonic acid

- ATM

adipose tissue macrophages

- BMDM

bone marrow-derived macrophages

- Cer

ceramide

- COX2

cyclooxygenase 2

- DAG

diacylglycerol

- DAMP

damage-associated molecular pattern

- Des

dihydroceramide desaturase

- FFA

free fatty acid

- γT3

gamma tocotrienol

- GPL

glycerophospholipids

- NLRP3

NOD-like receptor protein 3

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- LPS/pal

palmitate stimulation in LPS-primed conditions

- LysoPA

lysophosphatidic acid

- LysoPC

lysophosphatidyl choline

- LysoPE

Lysophosphatidyl ethanolamine

- LysoPL

lysophospholipids

- LysoPS

lysophosphatidyl serine

- PA

phosphatidic acid

- PC

phosphatidyl choline

- PE

phosphatidyl ethanolamine

- PL

phospholipids

- cPLA2

cytosolic phospholipase A2

- PLC

phospholipase C

- PGE2

prostaglandin E2

- Spt

serine-palmitoyl transferase

- SM

sphingomyelin

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Greenberg AS, Obin MS. Obesity and the role of adipose tissue in inflammation and metabolism. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83(2):461s–465s. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.2.461S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weisberg SP, et al. Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. J Clin Invest. 2003;112(12):1796–808. doi: 10.1172/JCI19246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haneklaus M, O’Neill LA. NLRP3 at the interface of metabolism and inflammation. Immunol Rev. 2015;265(1):53–62. doi: 10.1111/imr.12285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carta S, et al. DAMPs and inflammatory processes: the role of redox in the different outcomes. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;86(3):549–55. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1008598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Legrand-Poels S, et al. Free fatty acids as modulators of the NLRP3 inflammasome in obesity/type 2 diabetes. Biochem Pharmacol. 2014;92(1):131–41. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2014.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dennis EA, Norris PC. Eicosanoid storm in infection and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15(8):511–23. doi: 10.1038/nri3859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maurya MR, et al. Analysis of inflammatory and lipid metabolic networks across RAW264.7 and thioglycolate-elicited macrophages. J Lipid Res. 2013;54(9):2525–42. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M040212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sims K, et al. Kdo2-lipid A, a TLR4-specific agonist, induces de novo sphingolipid biosynthesis in RAW264.7 macrophages, which is essential for induction of autophagy. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(49):38568–79. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.170621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao L, et al. Regulation of Obesity and Metabolic Complications by Gamma and Delta Tocotrienols. Molecules. 2016;21(3):344. doi: 10.3390/molecules21030344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao L, et al. Gamma-tocotrienol attenuates high-fat diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance by inhibiting adipose inflammation and M1 macrophage recruitment. Int J Obes (Lond) 2015;39(3):438–46. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2014.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao L, et al. Muscadine grape seed oil as a novel source of tocotrienols to reduce adipogenesis and adipocyte inflammation. Food Funct. 2015;6(7):2293–302. doi: 10.1039/c5fo00261c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim Y, et al. Suppression of NLRP3 inflammasome by gamma-tocotrienol ameliorates type 2 diabetes. J Lipid Res. 2016;57(1):66–76. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M062828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jang Y, Rao X, Jiang Q. Gamma-tocotrienol profoundly alters sphingolipids in cancer cells by inhibition of dihydroceramide desaturase and possibly activation of sphingolipid hydrolysis during prolonged treatment. J Nutr Biochem. 2017;46:49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2017.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang X, Goncalves R, Mosser DM. The isolation and characterization of murine macrophages. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2008;Chapter 14(Unit 14.1) doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im1401s83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gromovsky AD, et al. Delta-5 Fatty Acid Desaturase FADS1 Impacts Metabolic Disease by Balancing Proinflammatory and Proresolving Lipid Mediators. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2018;38(1):218–231. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.117.309660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suram S, et al. Regulation of cytosolic phospholipase A2 activation and cyclooxygenase 2 expression in macrophages by the beta-glucan receptor. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(9):5506–14. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509824200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim J, et al. Eicosapentaenoic Acid Potentiates Brown Thermogenesis through FFAR4-dependent Up-regulation of miR-30b and miR-378. J Biol Chem. 2016;291(39):20551–62. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.721480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Souza CO, et al. Palmitoleic acid reduces the inflammation in LPS-stimulated macrophages by inhibition of NFkappaB, independently of PPARs. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2017;44(5):566–575. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aslan M, et al. Inhibition of neutral sphingomyelinase decreases arachidonic acid mediated inflammation in liver ischemia-reperfusion injury. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7(11):7814–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edsfeldt A, et al. Sphingolipids Contribute to Human Atherosclerotic Plaque Inflammation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36(6):1132–40. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.116.305675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanman LE, et al. Disruption of glycolytic flux is a signal for inflammasome signaling and pyroptotic cell death. Elife. 2016;5:e13663. doi: 10.7554/eLife.13663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nomura J, et al. Intracellular ATP Decrease Mediates NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation upon Nigericin and Crystal Stimulation. J Immunol. 2015;195(12):5718–24. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wen H, et al. Fatty acid-induced NLRP3-ASC inflammasome activation interferes with insulin signaling. Nat Immunol. 2011;12(5):408–15. doi: 10.1038/ni.2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Norris PC, et al. Phospholipase A2 regulates eicosanoid class switching during inflammasome activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(35):12746–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1404372111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alhouayek M, Masquelier J, Muccioli GG. Controlling 2-arachidonoylglycerol metabolism as an anti-inflammatory strategy. Drug Discov Today. 2014;19(3):295–304. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2013.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Labar G, Wouters J, Lambert DM. A review on the monoacylglycerol lipase: at the interface between fat and endocannabinoid signalling. Curr Med Chem. 2010;17(24):2588–607. doi: 10.2174/092986710791859414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fowler CJ. Monoacylglycerol lipase - a target for drug development? Br J Pharmacol. 2012;166(5):1568–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.01950.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peters-Golden M, et al. Glucocorticoid inhibition of zymosan-induced arachidonic acid release by rat alveolar macrophages. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1984;130(5):803–9. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1984.130.5.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perez-Chacon G, et al. Control of free arachidonic acid levels by phospholipases A2 and lysophospholipid acyltransferases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1791(12):1103–13. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khanna S, et al. Nanomolar vitamin E alpha-tocotrienol inhibits glutamate-induced activation of phospholipase A2 and causes neuroprotection. J Neurochem. 2010;112(5):1249–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06550.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hardwick JP, et al. Eicosanoids in metabolic syndrome. Adv Pharmacol. 2013;66:157–266. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-404717-4.00005-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yam ML, et al. Tocotrienols suppress proinflammatory markers and cyclooxygenase-2 expression in RAW264.7 macrophages. Lipids. 2009;44(9):787–97. doi: 10.1007/s11745-009-3326-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Y, Jiang Q. gamma-Tocotrienol inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced interlukin-6 and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor by suppressing C/EBPbeta and NF-kappaB in macrophages. J Nutr Biochem. 2013;24(6):1146–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2012.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jiang Q. Natural forms of vitamin E: metabolism, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory activities and their role in disease prevention and therapy. Free Radic Biol Med. 2014;72:76–90. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hua KF, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 regulates NLRP3 inflammasome-derived IL-1beta production. J Cell Physiol. 2015;230(4):863–74. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zaslona Z, et al. The Induction of Pro-IL-1beta by Lipopolysaccharide Requires Endogenous Prostaglandin E2 Production. J Immunol. 2017;198(9):3558–3564. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1602072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scholz H, Eder C. Lysophosphatidylcholine activates caspase-1 in microglia via a novel pathway involving two inflammasomes. J Neuroimmunol. 2017;310:107–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2017.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schilling JD, et al. Palmitate and lipopolysaccharide trigger synergistic ceramide production in primary macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(5):2923–32. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.419978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang Y, et al. Vitamin E gamma-Tocotrienol Inhibits Cytokine-Stimulated NF-kappaB Activation by Induction of Anti-Inflammatory A20 via Stress Adaptive Response Due to Modulation of Sphingolipids. J Immunol. 2015;195(1):126–33. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1403149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jiang Z, Yin X, Jiang Q. Natural forms of vitamin E and 13′-carboxychromanol, a long-chain vitamin E metabolite, inhibit leukotriene generation from stimulated neutrophils by blocking calcium influx and suppressing 5-lipoxygenase activity, respectively. J Immunol. 2011;186(2):1173–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luheshi NM, et al. Sphingosine regulates the NLRP3-inflammasome and IL-1beta release from macrophages. Eur J Immunol. 2012;42(3):716–25. doi: 10.1002/eji.201142079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Camell CD, et al. Macrophage-specific de Novo Synthesis of Ceramide Is Dispensable for Inflammasome-driven Inflammation and Insulin Resistance in Obesity. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(49):29402–13. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.680199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li Z, et al. The ratio of phosphatidylcholine to phosphatidylethanolamine influences membrane integrity and steatohepatitis. Cell Metab. 2006;3(5):321–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van der Veen JN, et al. The critical role of phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylethanolamine metabolism in health and disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2017;1859(9 Pt B):1558–1572. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2017.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]