Abstract

Yersiniosis belongs to the common foodborne diseases around the world, and frequently manifests as diarrhea that can be treated with probiotics. Colicin FY is an antibacterial agent produced by bacteria and it is capable of specific growth inhibition of Yersinia enterocolitica, the causative agent of gastrointestinal yersiniosis. In this study, recombinant E. coli producing colicin FY were constructed, using both known probiotic strains EcH22 and EcColinfant, and the newly isolated murine strains Ec1127 and Ec1145. All E. coli strains producing colicin FY inhibited growth of pathogenic Y. enterocolitica during co-cultivation in vitro. In dysbiotic mice treated with streptomycin, E. coli strains producing colicin FY inhibited progression of Y. enterocolitica infections. This growth inhibition was not observed in mice with normal gut microflora, likely due to insufficient colonization capacity of E. coli strains and/or due to spatial differences in intestinal niches. Isogenic Y. enterocolitica producing colicin FY was constructed and shown to inhibit pathogenic Y. enterocolitica in mice with normal microflora. Evidence of in vivo antimicrobial activity of colicin FY may have utility in the treatment of Y. enterocolitica infections.

Introduction

A total of 6,861 confirmed cases of yersiniosis (i.e., infections caused by Yersinia enterocolitica) were reported in the European Union in 2016, making yersiniosis the third most common human zoonosis in the EU1. In the United States, Yersinia enterocolitica causes an estimated 100,000 infections annually2,3. Infections caused by Y. enterocolitica range from self-limited enteritis to life-threatening systemic infections, however, the most common manifestation is diarrhea, and occurs mainly in children4–7. Several studies also support the idea that Y. enterocolitica infection may be associated with the development of chronic inflammatory bowel diseases8. Although antibiotic treatment is recommended for serious cases, the benefits of antibiotic therapy in uncomplicated cases have not been well demonstrated9,10. Instead, rehydration and use of probiotics are often suggested for simple diarrheal cases.

Probiotics are live microorganisms that confer a health benefit on the host when administrated in adequate amounts11. Many probiotic products are based on particular strains of lactic acid bacteria, such as Lactobacillus, Lactococcus, or Bifidobacterium species; however, Escherichia coli and other bacteria (and even yeast species) have been used as probiotics12. Among several probiotic strains patented for commercial applications, E. coli strains are part of three approved human probiotic drugs: Mutaflor (Ardeypharm GmbH; Herdecke, Germany), Symbioflor-2 (Symbiopharm GmbH; Herborn, Germany), and Colinfant New Born (Dyntec; Terezín, Czech Republic)12.

Production of antimicrobial substances is one of the most important features in the context of bacterial fitness and also in terms of probiotic efficacy13. Bacteriocins are antimicrobial peptides or proteins produced by many bacterial species, including probiotic strains, and bacteriocin preparations have been successfully used in food preservation and in veterinary medicine (reviewed in14,15). In the Enterobacteriaceae family, bacteriocins are frequently produced by E. coli strains16,17. Among E. coli, two molecular types of bacteriocins have been described, including microcins (peptides) and colicins (proteins). To date, more than twenty colicins have been characterized in various levels of detail (reviewed in18,19) and several colicin types have been shown to specifically inhibit pathogenic bacteria in vitro20–25. One of the well-characterized colicins, colicin FY, is produced by Yersinia frederiksenii Y27601, which harbors a plasmid with colicin FY activity and immunity genes (cfyA and cfyI, respectively). Besides the in vitro activity against several nonpathogenic and opportunistic yersiniae (i.e., Y. frederiksenii, Y. aldovae, Y. kristensenii, and Y. intermedia), colicin FY is also very effective against Y. enterocolitica, the causative agent of gastrointestinal yersiniosis. The exceptionally wide susceptibility of Y. enterocolitica strains to colicin FY, together with an absence of activity towards bacterial strains outside the Yersinia genus, is a consequence of the interaction between colicin FY and the yersinia-specific outer membrane protein YiuR, which also serves as a colicin FY receptor molecule20,21.

In this study, recombinant probiotic E. coli strains, producing colicin FY, were constructed and their therapeutic potential against Y. enterocolitica was analyzed in vitro and in vivo. The in vivo activity of colicin FY was also studied using isogenic and recombinant colicin FY producing Yersinia strain.

Results

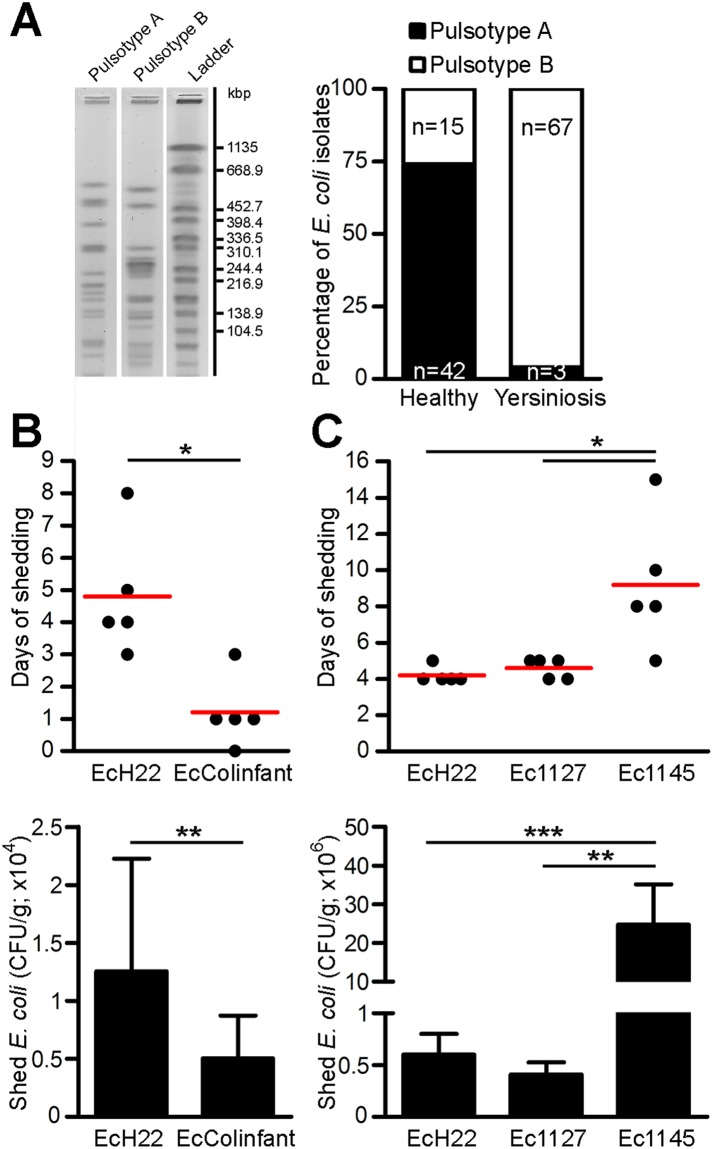

Escherichia coli strains and their intestinal colonization capacity

Since human E. coli strains are weak colonizers of the murine gut26,27, murine E. coli strains were isolated and used in this study. Among 127 murine E. coli isolates, pulsed field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) analysis found only two E. coli pulsotypes (Fig. 1A; see Methods). While strain Ec1127 was the dominant E. coli in mice with yersiniosis, strain Ec1145 was frequently isolated from healthy controls. In addition to Ec1127 and Ec1145, two E. coli strains with known probiotic features (EcH22 and EcColinfant) were used12,28.

Figure 1.

Characterization of murine E. coli isolates and colonization capacity of recombinant E. coli strains producing colicin FY. (A) Feces from four healthy mice and five mice with yersiniosis were collected for five days. A set of 127 E. coli isolates was obtained and resolved using PFGE, which found two pulsotypes. Strain Ec1127 was predominant in mice with yersiniosis, while strain Ec1145 was frequently isolated from healthy mice. The original gel is in Supplementary Fig. S1. (B,C) Mice (n = 5; each group) were inoculated with 107 CFU of E. coli and the fecal counts of recombinant E. coli were monitored for 15 days. The duration of shedding (top; red bar, mean) and the numbers of shed E. coli during the first five days (bottom; mean ± SEM) were plotted. EcH22 showed longer and stronger colonization capacity than EcColinfant (B). While Ec1127 showed colonization comparable to EcH22, Ec1145 displayed superior length and strength relative to E. coli shedding (C). The end of colonization was defined as two consecutive days without shedding of recombinant E. coli. Two-tailed Mann–Whitney–U test was used for statistical comparisons (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). Raw data for colonization capacity of E. coli strains are shown in Supplementary Fig. S1.

All four E. coli strains were transformed to stably maintain the recombinant colicinogenic plasmid and then tested for their capacity to colonize the murine gastrointestinal tract. While human EcH22 and murine Ec1127 showed similar colonization capacities, the colonization capacity of EcColinfant was considerably lower (*p < 0.05). EcColinfant was not detectable after day three of the experiment and lower amounts of bacteria were shed compared to EcH22 (**p < 0.01; Figs 1B and S1). The best colonization capacity was observed for murine Ec1145, which was detected up to fifteen days post infection (*p < 0.05) and the number of bacteria in mice feces during the first five days was approximately 40-times higher than for EcH22 and Ec1127 (***p < 0.001 and **p = 0.001, respectively; Figs 1C and S1). In addition, recombinant colicin producers showed similar colonization capacity compared to isogenic nonproducers (Supplementary Fig. S2).

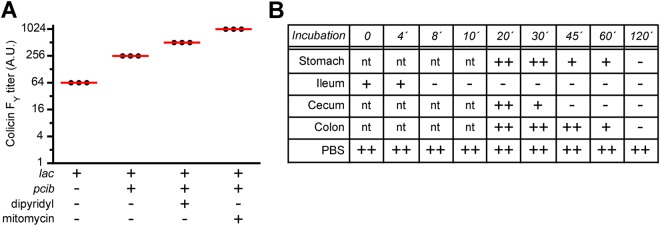

Recombinant expression and intestinal stability of colicin FY

Recombinant expression of colicin FY was tested in vitro using two recombinant expression systems, i.e., one with the basal lac expression of colicin FY and the second was with colicin FY expression controlled by the lac promoter and also by the gut inflammation-dependent promoter of colicin Ib (pcib) (constructs pDS1006 and pDS1281, respectively; see Methods). The presence of the pcib promoter enhanced colicin FY expression compared to expression from the lac promoter alone; moreover, colicin FY expression was inducible with iron limitation and the SOS response in vitro (Fig. 2A). Colicin FY recombinant expression controlled by both promoters was used throughout this study.

Figure 2.

Recombinant expression and stability of colicin FY under gastrointestinal conditions. (A) Colicin FY expression from the lac promoter alone, or in combination with pcib promoter was analyzed in vitro by spotting dilutions of colicin FY extracts on agar plates with susceptible Yersinia. The pcib promoter enhanced colicin FY expression and allowed the inducible expression of colicin FY by iron limitation (dipyridyl) and the SOS response (mitomycin). Three independent experiments are shown (red bar, mean). A.U. (arbitrary unit) – an inverted value of the highest dilution of crude colicin extract causing growth inhibition. (B) Colicin FY extract was incubated with murine gastrointestinal fractions, and the residual activity of colicin FY, at various time-points, was measured by spotting diluted suspensions on agar plates with susceptible Yersinia. Colicin FY stayed active for more than forty-five minutes in the colon contents. A representative result from three independent experiments is shown. ++activity of 10-fold diluted colicin FY; +activity of non-diluted colicin FY; −undetectable activity; nt, not tested.

To analyze colicin activity under gastrointestinal tract conditions, the contents of murine stomach, ileum, cecum, and colon were collected. Colicin FY was incubated with gastrointestinal fractions and its activity was analyzed over time. While ileum contents inactivated colicin FY within a few minutes, colicin FY stayed active for more than 45 minutes when cultivated with the colon contents (Fig. 2B).

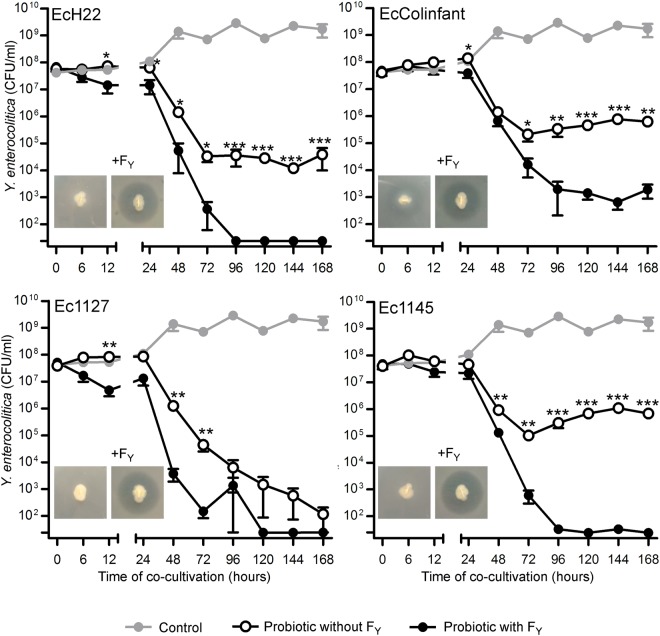

In vitro activity of recombinant colicinogenic E. coli against pathogenic Y. enterocolitica

The activity of recombinant colicin producers and isogenic colicin FY-nonproducing controls against Y. enterocolitica was tested on agar plates and also during continuous in vitro co-cultivation in broth (Fig. 3). On agar plates, production of colicin FY resulted in inhibition of Y. enterocolitica. In broth, Y. enterocolitica retained a stable concentration of approximately 109 CFU/ml when grown alone, while the presence of E. coli producing colicin FY significantly reduced the numbers of pathogen after 48 h of co-cultivation (Fig. 3). Due to competition, colicin FY nonproducers were also able to decrease the numbers of pathogenic Y. enterocolitica in co-cultivation; however, production of colicin FY enhanced inhibition activity of the tested E. coli strains and the Y. enterocolitica was completely or nearly completely eliminated after five days of co-cultivation (Fig. 3). In the presence of colicin FY, pathogen elimination was observed for strains EcH22, Ec1127, and Ec1145, but not for EcColinfant, where Y. enterocolitica persisted at detectable levels.

Figure 3.

In vitro activity of colicin FY-producing E. coli strains against pathogenic Y. enterocolitica. Y. enterocolitica was co-cultivated (37 °C, 200 rpm) with recombinant E. coli strains that either produced or did not produce colicin FY. Numbers of Y. enterocolitica were counted at various time-points and plotted (mean ± SEM). Production of colicin FY enhanced inhibition activity of the E. coli strains. Y. enterocolitica was eliminated within five days of co-cultivation, with the exception of EcColinfant where a small subpopulation of Y. enterocolitica persisted. Two-tailed Student’s t-test was used for statistical comparisons (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). Data were obtained from three independent experiments. The detection limit of the method was 25 CFU/ml. The microphotographs show inhibition zones resulting from probiotic colicin FY production on agar plates with susceptible Y. enterocolitica; isogenic colicin FY nonproducers did not form inhibition zones (except for a presence of a weak halo around EcColifant). The numbers of recombinant colicinogenic E. coli strains during co-cultivation are shown in Supplementary Fig. S3.

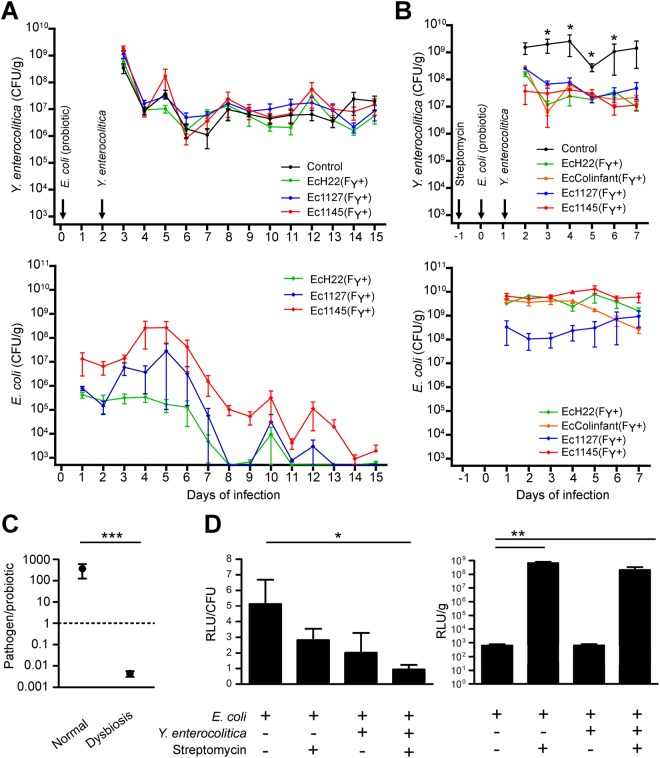

In vivo activity of recombinant colicinogenic E. coli against pathogenic Y. enterocolitica

Colicin FY activity was tested in vivo under several experimental settings. First, colicin FY activity was tested in mice with normal microflora. Since EcColinfant showed low colonization capacity and had weak inhibition during co-cultivation, only the remaining three colicin FY-producing E. coli strains were used during experimental Y. enterocolitica infection of mice. Recombinant E. coli was applied to experimental animals via drinking water and after 48 hours, animals were infected with pathogenic Y. enterocolitica in the same way. Clinical manifestations and the number of pathogenic Yersinia (and also recombinant E. coli) in the feces were monitored daily; both parameters stayed unaffected during the 15 days of the experiment (Figs 4A and S4). The use of different applications, inoculation doses, administration times, and application of various recombinant E. coli strains had no effect on Y. enterocolitica (Supplementary Fig. S4).

Figure 4.

In vivo activity of recombinant colicin FY-producing E. coli against Y. enterocolitica. (A) Mice with a normal microflora (n = 5; each group) were inoculated with colicin FY-producing E. coli and then with Y. enterocolitica. Only Y. enterocolitica was administered to controls (n = 5). Numbers of shed Y. enterocolitica were counted and plotted (mean ± SEM). No statistical differences in Y. enterocolitica numbers were observed between treated and untreated animals (top). Based on the E. coli numbers, recombinant E. coli colonized the intestines transiently (bottom). Raw data are shown in Supplementary Fig. S4. (B) Streptomycin-treated mice (n = 5; each group) were inoculated with colicin FY-producing E. coli, and then infected with Y. enterocolitica. Only Y. enterocolitica was administered to the streptomycin-treated controls (n = 3). Numbers of shed Y. enterocolitica were counted and plotted (mean ± SEM). For all the probiotics used, significant decreases of pathogen numbers were found between days D3 and D6 (top). At the same time, the E. coli numbers remained stable during the experiment (bottom). (C) Based on the numbers of bacteria in the first five days of infection, the ratio of Y. enterocolitica to Ec1145 in normal mice versus the streptomycin-treated mice showed that the pathogen significantly outgrew the probiotic in the normal mice, while Ec1145 dominated in the dysbiotic mice. (D) Mice (n = 5; each group) were treated or not with streptomycin and/or with Y. enterocolitica a day later. After another 24 h, mice were inoculated with Ec1145 expressing the luciferase under lac-pcib regulation; the colon contents were collected two days later and subjected to a luciferase assay. Reporter expression calculated for a single bacterial cell (CFU) was within a range of one order of magnitude across the treatments (left), but the total levels of reporter were significantly increased in the intestinal dysbiosis compared to intestines with normal microflora (right). Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. RLU, relative luciferase unit per second. (A–D) Two-tailed Mann–Whitney–U test was used for statistical comparisons (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

Second, the in vivo activity of colicin FY was tested using a mouse model, in which streptomycin was used to decrease the gut microflora and to promote gut inflammation26. Four recombinant E. coli (including EcColinfant) strains with colicin FY expression regulated by lac-pcib promoters were used during experimental Y. enterocolitica infection of streptomycin-treated mice. Twenty-four hours after streptomycin application, recombinant colicinogenic E. coli was applied to experimental animals via drinking water, and after another 24hours, the animals were infected with pathogenic Y. enterocolitica in the same way. The clinical manifestation and number of pathogenic Yersinia (and also recombinant E. coli) in feces were monitored daily. Y. enterocolitica infection was decreased by the presence of colicinogenic E. coli in the gastrointestinal tract of streptomycin-treated mice by one to two orders of magnitude (*p < 0.05; Fig. 4B). The levels of all tested recombinant E. coli strains remained stable throughout the experiments (Fig. 4B). Based on the pathogen-to-probiotic ratio, the relative amount of probiotic E. coli was elevated by almost 6-orders in the streptomycin model compared to mice with normal gut microflora (***p < 0.001; Fig. 4C). In addition, promoter activity regulating colicin FY expression in mice intestines was analyzed using the luciferase assay. While the reporter gene expression by a single bacterium was similar (i.e., difference between signals within one order of magnitude) in mice with normal and streptomycin-treated microflora, the total reporter signal in the colon contents was raised by several orders of magnitude in the streptomycin-treated mice (**p < 0.01; Fig. 4D). Taken together, intestinal dysbiosis increased the colonization capacity and allowed in vivo activity of the colicinogenic E. coli against the pathogenic Y. enterocolitica.

In vivo activity of colicin FY using recombinant isogenic Y. enterocolitica strains

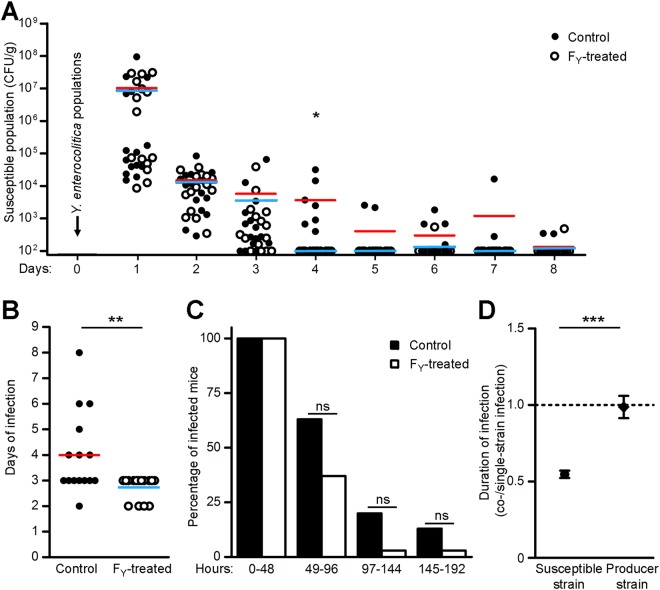

Besides the colonization resistance shown by intestines with normal microflora, the activity of recombinant E. coli against Y. enterocolitica could also be limited by spatial differences in their intestinal niches, i.e., avoiding their direct interaction. Therefore, two isogenic strains of Y. enterocolitica, a colicin producer and a colicin-susceptible indicator, were constructed (see Methods) and tested in mice with normal gut microflora using simultaneous administration. Compared to the control group (without a colicin producer), administration of colicin-producing Y. enterocolitica limited the numbers of the colicin-susceptible strain (*p < 0.05 on day four; Fig. 5A), shortened the infection period of the susceptible strain (**p < 0.01; Fig. 5B), and showed a tendency towards lower numbers of infected animals with the susceptible strain (Fig. 5C). While the infection period of susceptible Y. enterocolitica was decreased in the presence of colicin FY, the infection period of the colicin producer was not affected (Fig. 5D); thus, the infection period limitation of colicin-susceptible strain was not due to co-cultivation.

Figure 5.

Colicin FY activity in mice with normal gut microflora using two isogenic populations of Y. enterocolitica. Fifteen mice were simultaneously inoculated with two recombinant isogenic Y. enterocolitica strains, one a colicin FY producer and the other a colicin-susceptible indicator. In the control group (n = 15), only the colicin-susceptible Y. enterocolitica indicator strain was administered. Numbers of shed Y. enterocolitica were counted, plotted and two-tailed Mann–Whitney–U test was used for statistical comparisons (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01). Compared to the control group (black dot; red bar, mean), animals treated with the colicin-producer (white dot; blue bar, mean) showed lower numbers of colicin-susceptible Y. enterocolitica (A) and a shorter duration of infection (B). (C) In the presence of a colicin FY producer, mice showed a tendency towards less frequency of susceptible Y. enterocolitica infection than the control animals (Fisher’s exact test). ns, not significant. (D) The ratio of the co-infection period to the single infection period for the susceptible strain and for the producer strain. While susceptible Y. enterocolitica infection was shorter in the presence of colicin FY than in controls, the shedding period of colicin-producing Y. enterocolitica was not affected. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM and two-tailed Mann–Whitney–U test was used for statistical comparison (***p < 0.001). Detection limit of the method was 100 CFU/g of feces (A). The end of infection was defined as two consecutive days without the pathogen being detected (B,D).

Discussion

In this study, recombinant probiotic E. coli strains producing colicin FY were shown to inhibit Y. enterocolitica in vitro and in vivo. Besides colicin FY20, pesticin I and enterocoliticin were characterized at various levels of detail and both showed activity against pathogenic yersiniae in vitro29,30; however, their activity was not clearly confirmed in vivo31. As shown in a previous study, colicin FY inhibited all tested Y. enterocolitica isolates belonging to the most common serotypes21 and therefore production of colicin FY was predicted as a promising feature of probiotic strains in the treatment of gastrointestinal yersiniosis21. To date, production of colicin FY had not been identified in E. coli isolates; therefore, recombinant E. coli strains producing colicin FY had to be constructed for this study.

Out of four E. coli strains used, probiotic features were previously ascribed to EcH22 and EcColinfant. The human probiotic EcH22 was shown to produce microcin C7 (and several other antimicrobial substances), which mediated an inhibition of pathogenic Shigella in the gnotobiotic mice model28. The EcColinfant strain is a component of the probiotic product “Colinfant New Born” marketed by Dyntec (Terezín, Czech Republic). In the Czech Republic, it is used for several conditions in newborns and infants, such as disorders in the composition of intestinal microflora after antibiotic treatment (reviewed in12). Since human E. coli strains were shown to be weak colonizers of the murine gut26,27, two additional strains, Ec1127 and Ec1145, were isolated from mice and used in this study. The mice model used to study of colicin FY activity against pathogenic Yersinia is well-established model for human yersiniosis32,33.

As shown in this study, recombinant E. coli producing FY eliminated the growth of Y. enterocolitica serotype 0:3 during in vitro cultivation over five days. In general, production of bacteriocins is regarded as an important feature for probiotic efficacy13 and several theoretical studies have suggested that bacteriocin producers have a competitive advantage over non-producers when colonizing the same ecological niche34–36. In fact, activity of bacteriocins against other (pathogenic) bacteria has been described in many experimental in vitro studies, but bacteriocin activity in animal models is not well established (reviewed in13,37,38). Studies of colicin activity in vivo often show no or only subtle effects of colicin synthesis35,39,40. Inactivation of colicins by intestinal proteases or reduced colicin activity under anaerobic conditions have been suggested as the underlying reasons for their in vivo inactivity41,42. Using the luciferase assay, we showed that colicin FY recombinant promoters (i.e., lac-pcib) were active in mice guts and moreover, colicin FY stayed fully active for more than forty-five minutes when cultivated with the contents of the murine colon.

Despite expression of colicin FY and its intestinal stability, together with in vitro activity, the in vivo activity of colicin FY against Y. enterocolitica using mice with normal gut microflora was not observed. On the other hand, recombinant E. coli producing colicin FY inhibited Y. enterocolitica in streptomycin-treated mice. Gut inflammation, often associated with dysbiosis and expansion of Enterobacteriaceae, results in stress conditions including induction of the SOS-response and iron limitation43–45. Expression of colicins is tightly regulated by the SOS-response promoter, and in addition, colicins Ia, Ib, and FY are also regulated by the iron-dependent Fur promoter20,46,47. Recently, several studies showed that bacteriocin activity is associated with inflammatory conditions in the gut27,43,47. Using streptomycin-treated mice (mouse Salmonella-colitis model), Deriu et al.43 showed that the probiotic strain E. coli Nissle 1917, producing bacteriocins mM and mH47, outcompeted and reduced S. Typhimurium colonization; and the probiotic activity depended on iron acquisition by E. coli Nissle 1917. Sassone-Corsi et al.27 demonstrated that microcins H47 and M enabled the probiotic E. coli Nissle 1917 to limit the expansion of competing enterobacteria (including pathogenic S. Typhimurium) during intestinal inflammation using the mouse colitis model. Another study analyzed competition between colicin Ib-producing Salmonella Typhimurium and colicin-susceptible E. coli and revealed that gut inflammation promotes the effects of colicin Ib via the iron-dependent Fur promoter, which increases colicin production and also expression of its cognate receptor CirA, which mediates susceptibility of the competitor47.

While colicin FY expression was shown to be in vitro inducible (up to approximately ten-times) by iron limitation and the SOS-response via the gut inflammation-dependent promoter of colicin Ib (Fig. 2), the luciferase assay of recombinant E. coli strains present in the mice colon contents showed that the expression level from a single bacterial cell (RLU/CFU) was similar for mice with normal gut microflora, for streptomycin-treated mice, and for the yersiniosis model (3 days post infection of pathogen). Moreover, the expression per cell was lower in the yersiniosis model than in healthy mice (Fig. 4D), while Nedialkova et al.47 showed enhanced in vivo expression from the colicin Ib promotor (pcib) using the Salmonella-colitis model. These data could indicate no or subtle inflammation caused by streptomycin or yersiniosis in animal models (contrary to the Salmonella-colitis model48). In contrast, the total amount of reporter signal (RLU/g) was significantly increased (approximately 1,000,000-times) in streptomycin-treated mice (Fig. 4D). These data are consistent with a scenario in which gut inflammation in the streptomycin/yersiniosis model is not sufficient to upregulate colicin FY synthesis; however, the colonization capacity of recombinant colicinogenic E. coli is significantly enhanced as a result of dysbiosis (i.e., elimination of gram negative bacteria) in streptomycin-treated mice.

In this study, recombinant colicinogenic E. coli colonized the gut of normal mice with yersiniosis, but only transiently, while streptomycin-treatment allowed a robust, stable, and long-term E. coli colonization of the mouse gut (Fig. 4). The increased number of E. coli found in streptomycin-treated mice suggests that colonization resistance is the major limitation of the use of mice with a normal gut microflora. Colonization resistance is defined as an inhibition of invading microorganisms by resident microflora during healthy homeostasis49. Streptomycin treatment reduces colonization resistance and opens the E. coli niches, which are occupied by the resident strains during homeostasis.

To avoid the effect of E. coli colonization resistance and to show in vivo colicin FY activity, an alternative approach was used. Since colonization resistance was not observed for pathogenic Y. enterocolitica, a model of two isogenic Y. enterocolitica populations was used to study colicin FY in mice with normal microflora. In this model, colicin FY-producing Y. enterocolitica inhibited colicin-susceptible Y. enterocolitica (Fig. 5) and thus, in vivo colicin FY activity was, for the first time, demonstrated using animals with normal intestinal microflora.

In conclusion, the activity of colicin FY in vivo was clearly demonstrated; however, the use of probiotic E. coli strains synthesizing colicin FY in the normal mice model was not successful since the active colicin FY molecule was not delivered to the target Y. enterocolitica cells, most likely because of a combination of colonization resistance and spatially different intestinal niches. Besides attenuated/nonpathogenic Yersinia, other candidates for delivery of colicin FY to target could be tested among the relatively abundant classes of Firmicutes or Bacteroidetes (e.g., Lactococcus, Lactobacillus, and Pediococcus50–55). Alternatively, sufficient in vivo quantities of the active molecule could be ensured by direct application of the purified bacteriocin56,57.

Moreover, this study demonstrated that colicin FY synthesis could be an important feature of probiotic E. coli strains. Although the effect of probiotic E. coli strains is limited under healthy conditions, the potential effect of probiotic E. coli strains and synthesized bacteriocin molecules appear to be more effective under dysbiotic conditions in the gut. Taken together, colicin FY itself appears to have sufficient activity for treatment of gastrointestinal yersiniosis, however, the suitable application form needs to be experimentally determined.

Methods

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

Yersinia frederiksenii strain Y27601 producing colicin FY20, two pathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica strains (serotypes O:3 and O:8)58, and two Escherichia coli strains with probiotic features including E. coli O83:K24:H31 (EcColinfant; isolated from “Colinfant New Born”) and E. coli H22 (EcH22)28, were obtained from our laboratory stock. Two murine E. coli strains (i.e., Ec1127 and Ec1145) were isolated and characterized in this study (see below). The list of strains and plasmids constructed in this work is shown in Supplementary Table S1.

Tryptone-yeast (TY) broth consisting of 8 g/l tryptone (Hi-Media), 5 g/l yeast extract (Hi-Media), and 5 g/l sodium chloride in water was used throughout the study. For cultivation on solid media, TY broth was supplemented with agar powder (1.2%, w/v; Hi-Media). TY agar plates supplemented with chloramphenicol (final concentration 0.025 g/l; Sigma-Aldrich) or kanamycin (0.050 g/l; Sigma-Aldrich) were used for selection and maintenance of recombinant strains. Pathogenic Y. enterocolitica was cultivated on plates with selective diagnostic CIN agar (Cefsulodin-Irgasan-Novobiocin; Hi-Media). Streptomycin-resistant variants of strains used in this work were selected by cultivation on agar plates supplemented with streptomycin (0.050 g/l; Sigma-Aldrich). The cultivations of E. coli and Y. enterocolitica strains were performed at 37 °C and 30 °C, respectively.

Identification and characterization of murine E. coli isolates

For five days, the feces from four healthy control BALB/c mice and five BALB/c mice with experimental yersiniosis and stably shedding Y. enterocolitica (for twenty days) were collected. All feces were diluted in PBS, homogenized, and spread on selective diagnostic Endo agar (Hi-Media). After cultivation (overnight, 37 °C), three colonies were picked from each plate and taxonomically identified using ENTEROtest16 (Erba Lachema, Brno, Czech Republic). All 127 identified murine E. coli isolates were analyzed using XbaI digestion of genomic DNA and pulsed field gel electrophoresis (PFGE; PulseNet protocol (CDC 2002))59. PFGE profiles were analyzed using BioNumerics fingerprinting software (Applied Math).

For in vivo colonization capacity, animal experiments were performed by a licensed staff at an accredited facility of the Veterinary Research Institute (Brno, Czech Republic). Female BALB/c mice (6–9 weeks old) were kept individually in conditions without the presence of specific pathogens. Each experimental group contained five mice, which were orally infected with a single dose of recombinant E. coli strain (107 CFU using a gastric probe). During 15 days, fresh feces from each mouse were collected daily, homogenized in PBS, 10-fold serially diluted, and spread on agar plates with kanamycin. Numbers (CFU/g feces) of shed recombinant E. coli were calculated.

Construction of recombinant strains

Two recombinant plasmids harbouring colicin FY locus were used in this study including the pDS1006 with colicin FY expression under the control of lac promoter and the pDS1281 with colicin FY expression under the control of lac-pcib promoters. pDS1006 was described previously20; briefly, colicin FY activity and immunity genes (cfyA and cfyI, respectively) from the original producer Y. frederiksenii Y27601 was cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO vector using a TOPO TA Cloning Kit (Invitrogen). The pDS1281 is a modification of the pDS1006 that harbors additional colicin Ib promoter (pcib)47 and it was constructed in this study using an In-Fusion HD Cloning kit (Clontech). Briefly, the pcib (200 nt in length) was amplified from genomic DNA of E. coli 360/79 (i.e., from the original producer of colicin Ib) using Pfu polymerase (Fermentas) and specific primers with overlaps complementary to the pDS1006 (Supplementary Table S1). The pcib amplicon was cloned (via recombination) into pDS1006 upstream of colicin FY gene, between lac promoter and colicin FY gene. Both plasmids, pDS1006 and pDS1281, were transformed into strains EcH22, EcColinfant, Ec1127, and Ec1145, which resulted in 8 various recombinant E. coli strains, all producing colicin FY.

To test the colicin FY recombinant expression, the pJB008 harboring a reporter gene (i.e, a firefly luciferase; luc) downstream of lac-pcib promoters was constructed. Briefly, luc gene was amplified from the vector pGL4.17 (Promega) using Pfu polymerase (Fermentas) and specific primers with overlaps complementary to the pDS1281 (Supplementary Table S1). Then, colicin FY gene in the pDS1281 was replaced by luc gene (via recombination) using E. cloni® 10G (Lucigen Corporation).

For construction of recombinant isogenic Y. enterocolitica strains, a commercial vector, pBeloBAC11 (New England Biolabs), encoding chloramphenicol resistance was electro-transformed into the colicin FY-susceptible indicator Y. enterocolitica strain 8081. Alternatively, a modified suicide vector pNKBOR60 carrying the recombinant colicinogenic locus pcib-cfyA-cfyI was constructed (pJB001) and used for stable insertion of the recombinant colicinogenic locus into the Y. enterocolitica 8081 chromosome, resulting in the Y. enterocolitica citE::cfyA-cfyI strain. The insertion was mapped to the citE gene (YE2651; NC_008800.161, position 2,868,244) and this insertion did not significantly affect the in vitro grown of mutant strain (Fig. S5).

Streptomycin-resistant variants of selected bacterial strains were obtained by cultivation in the presence of streptomycin (see above). A spontaneous mutation in the rpsL gene (position 248T) was identified by sequencing.

Analysis of colicin FY recombinant expression

Crude colicin FY extract was prepared as previously described20. Briefly, a 20-fold-diluted overnight TY culture of a colicinogenic strain was cultivated (37 °C, 200 rpm, 4 h), induced by mitomycin C (final concentration 500 µg/l) or iron limitation (0.2 mM 2,2′-dipyridyl and 0.1 mM Nitrilotriacetic acid trisodium salt), cultivated for additional 4 h (37 °C, 200 rpm), and centrifuged (15 min, 4,000 × g). The bacterial pellet was resuspended in 5 ml of distilled water, washed twice, and sonicated. The resulting bacterial lysate was centrifuged for 15 min at 4,000 × g, and the supernatant was used as a crude colicin FY extract. Colicin activity was tested by spotting 2-fold serial dilutions of colicin extract on agar plates with a thin layer of 0.75% agar containing a colicin-susceptible Yersinia strain (inoculated with 108 cells). After overnight incubation of plates at 37 °C, the inhibition zones of susceptible Yersinia were determined. The highest dilution of colicin suspension causing growth inhibition represented expression of colicin FY.

Analysis of colicin stability in the gastrointestinal tract

Female BALB/c mice (ca. 20 weeks old) were kept in conditions without the presence of specific pathogens. After cervical dislocation, mice intestinal contents from the stomach, ileum, cecum, and colon were separately collected in four fractions. For each intestine fraction, content was homogenized in PBS buffer (1 ml) by pippeting, centrifuged briefly (1 min, 14,000 × g), and supernatants were stored at −20 °C.

For analysis of colicin FY stability under gastrointestinal tract conditions, crude colicin FY extract (see above) was mixed with isolated fractions of intestinal contents (volume 1:1), incubated at 37 °C, and stopped at various time-points (i.e., at 0, 4, 8, 10, 20, 30, 45, 60, and 120 minutes) using a protease inhibitor cocktail (cOmplete™; Roche). Residual colicin activity was tested by spotting 10-fold serial dilutions of suspensions on agar plates with a colicin-susceptible Yersinia strain. After overnight incubation, the highest dilution of suspension causing growth inhibition of Yersinia was determined.

Analysis of colicin activity in vitro

Overnight cultures of Y. enterocolitica Y11 (30 °C, 200 rpm) and colicin FY producer (kanamycin, 37 °C, 200 rpm) were separately cultivated overnight in TY broth. Then, they were mixed (100 µl each) in fresh TY broth (5 ml) and were co-cultivated (37 °C, 200 rpm). The mixed bacterial suspension (100 µl) was inoculated daily into fresh TY broth (5 ml) for 15 days. In addition, aliquots of the bacterial suspension were collected and 10-fold serial PBS dilutions were spread on selective agar plates (i.e., kanamycin plates for colicin producer and CIN plates for Y. enterocolitica). Plates were cultivated overnight (37 °C) and bacterial numbers were counted.

Analysis of colicin activity in vivo

Animal experiments and handling were performed by a licensed staff at an accredited facility of the Veterinary Research Institute (Brno, Czech Republic). Female BALB/c mice (6–9 weeks old) were kept in conditions without the presence of specific pathogens. In the experiment, each group contained at least five experimental mice and each mouse was kept in the individual cage. Mice were orally infected (108 CFU/ml of the drinking water) with pathogenic Y. enterocolitica Y11. Recombinant strains producing colicin FY were also orally administered (108 CFU/ml) to experimental animals. Mice were monitored for weight, for condition of feces, and for clinical manifestation of yersiniosis. In addition, fresh feces were collected daily and processed, within 2 hours, for microbiological analysis. Fecal sample from each mouse was homogenized in PBS, 10-fold serially diluted, and spread on selective agar plates. While Y. enterocolitica was cultivated on CIN agar, recombinant E. coli producing colicin FY were selected on agar plates with kanamycin. Numbers (CFU/g feces) of pathogenic Y. enterocolitica and colicin-producers were calculated. In the streptomycin-treated mice model, streptomycin (5 g/l) was added to the drinking water 24 hours before inoculation and was applied during the whole experiment.

Analysis of colicin in vivo expression using luciferase assay

Luciferase assays were performed using a Luciferase assay system (E1500; Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and as previously described Nedialkova et al.47. Briefly, the mice (i.e., conventional mice, streptomycin-treated mice, and mice infected by Y. enterocolitica Y11; 5 mice per group) were inoculated with Ec1145 expressing a luciferase reporter (pJB008). Two days after application of reporter Ec1145, the colon contents were aseptically harvested from mice, thoroughly suspended in PBS (1,000 µl), and filtered through a 40 µm cell filter (Corning Cell Strainer). A defined volume of colon suspension (500 µl) was pelleted (4 °C, 10 min, 14,000 × g), the pellet was suspended in 1 M K2HPO4/20 mM EDTA (10 µl), frozen on dry ice (1 min), and stored at −80 °C. After thawing at room temperature, suspensions were mixed with 300 µl of fresh lysis buffer (1xCell Culture Lysis Reagent [E1531, Promega], 1,25 mg/ml lysozyme, and 2,5 mg/ml BSA), incubated (10 min, RT), and bacterial lysates (10 µl) were transferred into 96-well plates (3922; Costar). Using a TriStar2 LB 942 Modular Multimode Microplate Reader (Berthold Technologies), luciferase reagent was added to each well (40 µl), luminescence was measured, and relative light units per second (RLU) were calculated. Only values above the detection limit (control caecum contents) were considered. In addition, aliquots (50 µl) of colon suspensions were 10-fold serially diluted in PBS and spread on selective agar plates. After overnight cultivation, the amount (CFU) of reporter strain was determined and RLU per CFU of reporter strain was calculated.

Statistical analysis

Prism 5 software (GraphPad) was used for statistical analyses. Bacterial growth during in vitro experiments was analyzed using the unpaired Student’s t-test. The non-parametric Mann–Whitney–U test was used to analyze bacterial CFUs in feces, RLU/CFU in colon contents, and infection length. In addition, Fisher’s exact test was used for analysis of the frequency of yersiniosis. P-values less than 0.05 (2-tailed) were considered statistically significant, and were denoted with asterisks (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001).

Ethical approval and informed consent

The experimental protocol was approved by the Branch Commission for Animal Welfare of the Ministry of Agriculture of the Czech Republic (permission 22019/2016-MZe-17214) in accordance with Act No. 246/1992 Coll., on the protection of animals against torture, as subsequently amended, and with Decree 419/2012 Coll. on the protection, breeding and use of experimental animals.

Electronic supplementary material

Fig S1, Fig S2, Fig S3, Fig S4, Fig S5, Table S1

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Grant Agency of the Czech Republic (GA16-21649S) to D.Š. and by funds from the Faculty of Medicine, Masaryk University (ROZV/25/LF/2017) to junior researcher J.B. M.F. and E.G. were supported from the National Program of Sustainability LO1218. L.M. thanks the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic (the RECETOX research infrastructure: LM2015051) and the European Structural and Investment Funds (the RECETOX research infrastructure: CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/16_013/0001761) for additional support. We thank Thomas Secrest (Secrest Editing, Ltd.) for his assistance with the English revision of the manuscript.

Author Contributions

J.B. and D.Š. conceived and designed the study. J.B. performed the experiments together with M.H., K.P., L.M. and M.K.B. J.B. analysed the data with D.Š. and M.K.B. M.F. and E.G. were responsible for animal experiments. J.B. wrote the first draft of the manuscript; M.K.B., D.Š., M.F. and P.K. contributed to the writing of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved of the final manuscript.

Data availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-30729-7.

References

- 1.EFSA (European Food Safety Authority) and ECDC (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control) The European Union summary report on trends and sources of zoonoses, zoonotic agents and food‐borne outbreaks in 2016. EFSA J. 15, 10.2903/j.efsa.2017.5077 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Scallan E, et al. Foodborne illness acquired in the United States–major pathogens. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011;17:7–15. doi: 10.3201/eid1701.P11101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ong KL, et al. Changing epidemiology of Yersinia enterocolitica infections: markedly decreased rates in young black children, Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network (Food Net), 1996–2009. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012;54:S385–S390. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bottone EJ. Yersinia enterocolitica: the charisma continues. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1997;10:257–276. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.2.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ray SM, et al. Population‐based surveillance for Yersinia enterocolitica infections in FoodNet Sites, 1996–1999: higher risk of disease in infants and minority populations. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2004;38:S181–S189. doi: 10.1086/381585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duan R, et al. Prevalence of Yersinia enterocolitica Bioserotype 3/O:3 among children with diarrhea, China, 2010–2015. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2017;23:1502–1509. doi: 10.3201/eid2309.160827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marimon JM, et al. Thirty years of human infections caused by Yersinia enterocolitica in northern Spain: 1985–2014. Epidemiol. Infect. 2017;145:2197–2203. doi: 10.1017/S095026881700108X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saebo A, Vik E, Lange OJ, Matuszkiewicz L. Inflammatory bowel disease associated with Yersinia enterocolitica O:3 infection. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2005;16:176–182. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bottone EJ. Yersinia enterocolitica: overview and epidemiologic correlates. Microbes Infect. 1999;1:323–333. doi: 10.1016/S1286-4579(99)80028-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abdel-Haq NM, Asmar BI, Abuhammour WM, Brown WJ. Yersinia enterocolitica infection in children. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2000;19:954–958. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200010000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pineiro M, Stanton C. Probiotic bacteria: legislative framework–requirements to evidence basis. J. Nutr. 2007;137:850S–3S. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.3.850S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wassenaar TM. Insights from 100 years of research with probiotic E. coli. Eur. J. Microbiol. Immunol. 2016;6:147–161. doi: 10.1556/1886.2016.00029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dobson A, Cotter PD, Ross RP, Hill C. Bacteriocin production: a probiotic trait? Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012;78:1–6. doi: 10.1128/AEM.05576-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gillor O, Kirkup BC, Riley MA. Colicins and microcins: the next generation antimicrobials. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 2004;54:129–146. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2164(04)54005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diez-Gonzalez F. Applications of bacteriocins in livestock. Curr. Issues Intest. Microbiol. 2007;8:15–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Micenková L, Bosák J, Vrba M, Ševčíková A, Šmajs D. Human extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli strains differ in prevalence of virulence factors, phylogroups, and bacteriocin determinants. BMC Microbiol. 2016;16:218. doi: 10.1186/s12866-016-0835-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Micenková L, et al. Bacteriocin-encoding genes and ExPEC virulence determinants are associated in human fecal Escherichia coli strains. BMC Microbiol. 2014;14:109. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-14-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Šmarda J, Šmajs D. Colicins–exocellular lethal proteins of Escherichia coli. Folia Microbiol. (Praha). 1998;43:563–582. doi: 10.1007/BF02816372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cascales E, et al. Colicin biology. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2007;71:158–229. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00036-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bosák J, Laiblová P, Šmarda J, Dědičová D, Šmajs D. Novel colicin FY of Yersinia frederiksenii inhibits pathogenic Yersinia strains via YiuR-mediated reception, TonB import, and cell membrane pore formation. J. Bacteriol. 2012;194:1950–1959. doi: 10.1128/JB.05885-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bosák J, et al. Unique activity spectrum of colicin FY: All 110 characterized Yersinia enterocolitica isolates were colicin FY susceptible. Plos One. 2013;8:e81829. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bosák J, Micenková L, Doležalová M, Šmajs D. Colicins U and Y inhibit growth of Escherichia coli strains via recognition of conserved OmpA extracellular loop 1. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2016;306:486–494. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2016.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patton BS, Dickson JS, Lonergan SM, Cutler SA, Stahl CH. Inhibitory activity of colicin E1 against Listeria monocytogenes. J. Food Prot. 2007;70:1256–1262. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-70.5.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Šmajs D, Pilsl H, Braun V. Colicin U, a novel colicin produced by Shigella boydii. J. Bacteriol. 1997;179:4919–4928. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.15.4919-4928.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Šmajs D, Weinstock GM. The iron- and temperature-regulated cjrBC genes of Shigella and enteroinvasive Escherichia coli strains code for colicin Js uptake. J. Bacteriol. 2001;183:3958–3966. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.13.3958-3966.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spees AM, et al. Streptomycin-induced inflammation enhances Escherichia coli gut colonization through nitrate respiration. MBio. 2013;4:e00430–13. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00430-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sassone-Corsi, M. et al. Microcins mediate competition among Enterobacteriaceae in the inflamed gut. Nat. Publ. Gr. 540, 10.1038/nature20557 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Cursino L, et al. Exoproducts of the Escherichia coli strain H22 inhibiting some enteric pathogens both in vitro and in vivo. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2006;100:821–829. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2006.02834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hu PC, Yang GC, Brubaker RR. Specificity, induction, and absorption of pesticin. J. Bacteriol. 1972;112:212–219. doi: 10.1128/jb.112.1.212-219.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Strauch E, et al. Characterization of enterocoliticin, a phage tail-like bacteriocin, and its effect on pathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2001;67:5634–5642. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.12.5634-5642.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Damasko C, et al. Studies of the efficacy of enterocoliticin, a phage-tail like bacteriocin, as antimicrobial agent against Yersinia enterocolitica serotype O3 in a cell culture system and in mice. J. Vet. Med. Ser. B. 2005;52:171–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0450.2005.00841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heesemann J, Gaede K, Autenrieth IB. Experimental Yersinia enterocolitica infection in rodents: a model for human yersiniosis. APMIS. 1993;101:417–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1993.tb00130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schippers A, et al. Susceptibility of four inbred mouse strains to a low-pathogenic isolate of Yersinia enterocolitica. Mamm. Genome. 2008;19:279–291. doi: 10.1007/s00335-008-9105-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kerr B, Riley MA, Feldman MW, Bohannan BJM. Local dispersal promotes biodiversity in a real-life game of rock–paper–scissors. Nature. 2002;418:171–174. doi: 10.1038/nature00823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kirkup BC, Riley MA. Antibiotic-mediated antagonism leads to a bacterial game of rock–paper–scissors in vivo. Nature. 2004;428:412–414. doi: 10.1038/nature02429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Riley MA, Wertz JE. Bacteriocins: evolution, ecology, and application. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2002;56:117–137. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.56.012302.161024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hegarty JW, Guinane CM, Ross RP, Hill C, Cotter PD. Bacteriocin production: a relatively unharnessed probiotic trait? F1000Research. 2016;5:2587. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.9615.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sassone-Corsi M, Raffatellu M. No vacancy: how beneficial microbes cooperate with immunity to provide colonization resistance to pathogens. J. Immunol. 2015;194:4081–4087. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1403169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ikari NS, Kenton DM, Young VM. Interaction in the germfree mouse intestine of colicinogenic and colicin-sensitive microorganisms. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1969;130:1280–1284. doi: 10.3181/00379727-130-33773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gillor O, Giladi I, Riley MA. Persistence of colicinogenic Escherichia coli in the mouse gastrointestinal tract. BMC Microbiol. 2009;9:165. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-9-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kelstrup J, Gibbons RJ. Inactivation of bacteriocins in the intestinal canal and oral cavity. J. Bacteriol. 1969;99:888–890. doi: 10.1128/jb.99.3.888-890.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Braun V, Frenz J, Hantke K, Schaller K. Penetration of colicin M into cells of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1980;142:162–168. doi: 10.1128/jb.142.1.162-168.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deriu E, et al. Probiotic bacteria reduce Salmonella Typhimurium intestinal colonization by competing for iron. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;14:26–37. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schumann S, Alpert C, Engst W, Loh G, Blaut M. Dextran sodium sulfate-induced inflammation alters the expression of proteins by intestinal Escherichia coli strains in a gnotobiotic mouse model. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012;78:1513–1522. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07340-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stecher B. The roles of inflammation, nutrient availability and the commensal microbiota in enteric pathogen infection. Metabolism and Bacterial Pathogenesis. 2015;3:297–320. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.MBP-0008-2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gillor O, Vriezen JAC, Riley MA. The role of SOS boxes in enteric bacteriocin regulation. Microbiology. 2008;154:1783–1792. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/016139-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nedialkova LP, et al. Inflammation fuels colicin Ib-dependent competition of Salmonella serovar Typhimurium and E. coli in enterobacterial blooms. Plos Pathog. 2014;10:e1003844. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barthel M, et al. Pretreatment of mice with streptomycin provides a Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium colitis model that allows analysis of both pathogen and host. Infect. Immun. 2003;71:2839–2858. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.5.2839-2858.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lawley TD, Walker AW. Intestinal colonization resistance. Immunology. 2013;138:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2012.03616.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Corr SC, et al. Bacteriocin production as a mechanism for the antiinfective activity of Lactobacillus salivarius UCC118. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:7617–7621. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700440104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Frick JS, et al. Lactobacillus fermentum attenuates the proinflammatory effect of Yersinia enterocolitica on human epithelial cells. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2007;13:83–90. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Frick JS, et al. Identification of commensal bacterial strains that modulate Yersinia enterocolitica and dextran sodium sulfate-induced inflammatory responses: implications for the development of probiotics. Infect. Immun. 2007;75:3490–3497. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00119-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.De Montijo-Prieto S, et al. A Lactobacillus plantarum strain isolated from kefir protects against intestinal infection with Yersinia enterocolitica O9 and modulates immunity in mice. Res. Microbiol. 2015;166:626–632. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2015.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Millette M, et al. Capacity of human nisin- and pediocin-producing lactic acid bacteria to reduce intestinal colonization by vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008;74:1997–2003. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02150-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Walsh MC, et al. Predominance of a bacteriocin-producing Lactobacillus salivarius component of a five-strain probiotic in the porcine ileum and effects on host immune phenotype. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2008;64:317–327. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2008.00454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lopez FE, Vincent PA, Zenoff AM, Salomón RA, Farías RN. Efficacy of microcin J25 in biomatrices and in a mouse model of Salmonella infection. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2007;59:676–680. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stern NJ, et al. Bacteriocins reduce Campylobacter jejuni colonization while bacteria producing bacteriocins are ineffective. Microb. Ecol. Health Dis. 2008;20:74–79. doi: 10.1080/08910600802030196. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Batzilla J, Antonenka U, Höper D, Heesemann J, Rakin A. Yersinia enterocolitica palearctica serobiotype O:3/4–a successful group of emerging zoonotic pathogens. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:348. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Micenková L, et al. Human Escherichia coli isolates from hemocultures: Septicemia linked to urogenital tract infections is caused by isolates harboring more virulence genes than bacteraemia linked to other conditions. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2017;307:182–189. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2017.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rossignol M, Basset A, Espéli O, Boccard F. NKBOR, a mini-Tn10-based transposon for random insertion in the chromosome of Gram-negative bacteria and the rapid recovery of sequences flanking the insertion sites in Escherichia coli. Res. Microbiol. 2001;152:481–485. doi: 10.1016/S0923-2508(01)01221-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thomson NR, et al. The complete genome sequence and comparative genome analysis of the high pathogenicity Yersinia enterocolitica strain 8081. Plos Genet. 2006;2:e206. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig S1, Fig S2, Fig S3, Fig S4, Fig S5, Table S1

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.