Abstract

Pemetrexed is a candidate chemotherapy regimen for anthracycline- and taxane-pretreated advanced breast cancer. However, to the best of our knowledge, no efficient treatment efficacy biomarkers have been identified. In the present study, the potential correlation between thymidylate synthase (TYMS) expression and clinical response to pemetrexed was examined in advanced breast cancer. A retrospective collection was performed by using 77 advanced breast cancer subjects, who received at least three cycles of pemetrexed treatment in the Second Hospital of Shandong University hospital. TYMS expression was detected using immunohistopathological staining. The correlations between TYMS and therapeutic efficacies of different chemotherapy treatment were analyzed. The objective response rate (ORR) and disease control was 31.17 and 64.94%, respectively. Immunohistochemical staining demonstrated that TYMS expression was observed in the cytoplasm and nuclei of breast cancer cells. High TYMS expression was observed in 32 specimens. Elevated TYMS expression was correlated with higher histological grade and lymph node metastasis (P<0.05). Furthermore, significantly higher TYMS expression was observed in treatment-resistant patients than response ones (P<0.05). Patients with low expression level of TYMS exhibit significantly higher ORR. Cox regression analysis indicated that elevated TYMS expression was a detrimental factor for pemetrexed treatment for advanced breast cancer patients. The present results suggested that TYMS expression levels predicts therapeutic sensitivity of pemetrexed chemotherapy in advanced breast cancer, indicating that it may be a useful biomarker to choose chemotherapy regimens.

Keywords: advanced breast cancer, thymidylate synthase, pemetrexed, therapeutic efficacy, correlation

Introduction

Chemotherapy is the predominant option for advanced breast cancer patients. Efficacious chemotherapeutic protocols will prevent metastasis and recurrence, thereby to increase the possibility of surgical resection and to extend survival time. Single cytotoxic agents and combination chemotherapy regimens are recommended for the treatment of patients with metastatic disease (1,2). Nowadays, the optional chemotherapy specimens included anthracycline, paclitaxol and anti-metabolism medicines (3). Collective studies supported that pemetrexed effectively prolongs survival estimation in a proportion of advanced breast cancer patients, which was an optional specimen, especially followed with anthracycline- and taxane-containing regimens (4–6). However, the biomarkers which can effectively screen out suitable patients to receive pemetexed treatment is still unclear so far (5).

As a multi-targeted anti-metabolite, pemetrexed inhibits multiple targets of folic acid metabolic pathway, especially thymidylate synthase (TYMS) and other DNA synthase in folic acid metabolism (7,8). Previous researches indicated that pemetrexed efficacy was correlated with TYMS in lung adenocarcinoma and gastric cancer (9,10). Therefore, these enzymes are promising biomarkers for predicting the efficacy of pemetrexed chemotherapy. Here in our study, we investigated the correlation between clinical efficacy of pemetrexed chemotherapy and the expression of TYMS in advanced breast cancer.

Materials and methods

Patients and pemetrexed chemotherapy

Total 77 patients with advanced breast cancer at The Second Hospital of Shandong University (Jinan, China) from 2013 to 2015 were collected in this retrospective study. Pemetrexed chemotherapy was administrated in all the patients after anthracycline- and taxane-containing regimens. The regimen plan was pemetrexed (600 mg/m2) i.v. which was administered on day 1 of each 21-day cycle until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity or patient's refusal. Dexamethasone, folic acid and vitamin B12 supplement were administered according to chemotherapy protocol. Follow-up was performed to evaluate chemotherapy response after every two cycles according to RECIST. The objective response rate (ORR) was combined proportion of complete response (CR) and partial response (PR). The disease control rate (DCR) was combined proportion of CR, PR, and stable disease (SD).

Tumor specimens and tissue microarray (TMA)

The resected specimens of primary breast cancer were collected for TMAs, which were stored with formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue blocks. The representative areas of tumors were selected using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining slides of each tissue. TMA sections were prepared for immunohistochemical (IHC) staining at 5 µm of thickness. The pathological characteristics of each patient were determined by experienced pathologists, including histologic grade, lymph node metastasis and expression status of estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR) and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of The Second Hospital of Shandong University.

IHC staining and evaluation of staining

IHC staining was performed with TMAs according to the following steps: Dewaxing with dimethylbenzene, hydration with a gradient concentration of alcohol, antigen retrieval with citrate buffer (pH 6.0), endogenous peroxidase blockage with 0.3% H2O2 solution, TYMS antibody incubation (mAb; clone TYMS106/4H4B1, 1:50 dilution; Zymed, San Francisco, CA, USA) overnight at 4°C, staining with peroxidase-conjugated avidin and 3,3-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB), hematoxylin blue counterstain. Positive control was assigned IHC positive tissues, and control IgG was used as negative control. TMAs were blindedly evaluated by experienced pathologists. By using IHC staining, TYMS is located in both cytoplasm and nucleus of cancer cells. Both percentage and intensity of positive staining were evaluated for TYMS scores with a semi-quantitative scale (11). The intensity was evaluated into three groups: 0, no staining; 1, weak staining; and 2, strong staining. Summed scores of each tissue are ranging from 0 to 2.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS 19.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The cutoff values of TYMS IHC scores were studied with receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. The correlation between TYMS and other clinical characteristics, therapeutic efficiency was studied with χ2 test or Fisher's exact test. The effect of potential predictive variable was analyzed with cox proportional hazards regression model. The estimated relative risks were showed as adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Patient characteristics and pemetrexed treatment response

All the 77 patients were administrated with pemetrexed chemotherapy after anthracycline- and taxane-containing regimens as followed chemotherapy for advanced disease (Table I). The median age of the patients at diagnosis was 44 years (range 26-79 years). Approximately 54.55% of the patients were HR-positive, 9.09% were HER2-positive but HR-negative, and 36.36% were triple negative. Cancer metastasis was observed in lymph nodes (37.66%), bone (31.17%), lung (25.97%), liver (19.48%) and brain (6.49%). The median duration of pemetrexed treatment was 3.66 months (range, 1.40-5.62 months), and two patients only received three cycles of pemetrexed treatment because of disease progression and serious side-effects. Efficacy assessments showed that 3 cases had CR, 21 cases PR, 26 cases SD, and 27 cases PD. The total ORR for the patients was 31.17%, and DCR was 64.94%.

Table I.

Patients' characteristics.

| Variable | No. of patients | Percentage, % |

|---|---|---|

| Median age (years) | 44 (range, 26-79) | |

| Median duration (months) | 3.66 (range, 1.40-5.62) | |

| Subtype | ||

| HR+ | 42 | 54.55 |

| HER2+ | 7 | 9.09 |

| TN | 28 | 36.36 |

| Metastases | ||

| Liver | 15 | 19.48 |

| Lung | 20 | 25.97 |

| Bone | 24 | 31.17 |

| Brain | 5 | 6.49 |

| Lymph nodes | 29 | 37.66 |

| Response | ||

| CR | 3 | 3.90 |

| PR | 21 | 27.27 |

| SD | 26 | 33.77 |

| PD | 27 | 35.06 |

| ORR | 24 | 31.17 |

| DCR | 50 | 64.94 |

HR, hormone receptor; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; TN, triple-negative; CR, complete response; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease; ORR, objective response rate; DCR, disease control rate.

Relationship between TYMS and clinicopathological parameters

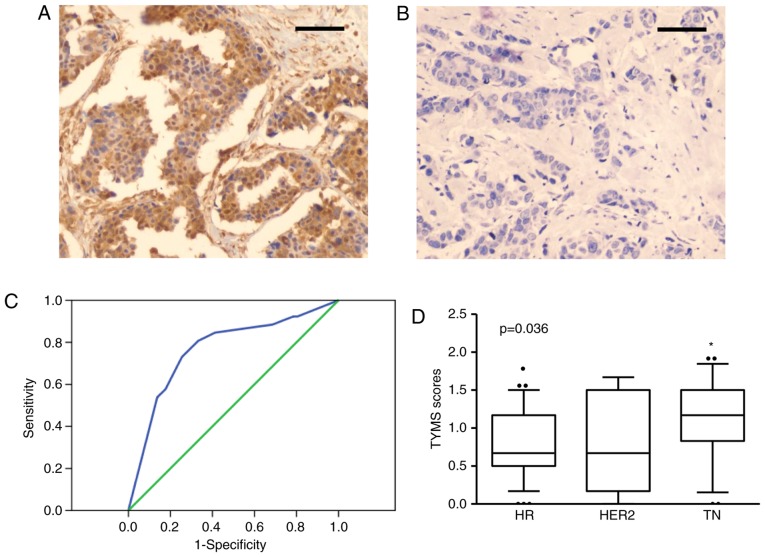

IHC staining shows that TYMS was mainly localized in cytoplasm and nucleus of the breast cancer cells (Fig. 1A). As described previously, TYMS expression was also observed in a large proportion of normal tissues, which is consistent with previous report (12). To further evaluate the correlation between TYMS and clinicopathological parameters, the patients were analyzed into two groups according TYMS scores: TYMS-high and TYMS-low. The cutoff value of TYMS score was 1.09 according to ROC curves analysis (AUC=0.768, P<0.001, 95% CI: 0.651-0.886, Fig. 1B). Totally 32 patients are in TYMS-high group, and 45 patients in TYMS-low group. No significant correlation was observed between TYMS expression and age, tumor size, expression of ER, PR and HER-2 (P>0.05 for each; Table II). However, high TYMS expression correlated with high histopathological grade and lymph node metastasis (P<0.05 for each; Table II). Notably, high TYMS expression was more common in patients with the triple-negative (TN) subtype than in those with other subtypes (P=0.036; Fig. 1C and D).

Figure 1.

TYMS expression in breast cancer specimens. (A and B) IHC staining of TYMS in breast cancer tissues. Representative image of (A) TYMS-high and (B) -low expression were shown. Bar, 50 µm. (C) Cut-off value of TYMS scores was analyzed with ROC. Cut-off Score=1.09, AUC=0.768, P<0.001, 95% CI, 0.651-0.886. (D) TYMS scores comparation between different subtypes of breast cancer tissues: HR positive (HR), HER2 positive (HER2) and triple negative (TN) ones. Data were analyzed with Fisher's exact test. P=0.036. *P<0.05 vs group HR or HER2. TYMS, thymidylate synthase; HR, hormone receptor; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2.

Table II.

Association between clinical characteristics and TYMS expression.

| TYMS expression | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Number (%) | Positive (%) | Negative (%) | P-value |

| Total | 77 | (32, 41.6) | (45, 58.4) | |

| Age, years | ||||

| <50 | 43 (55.8) | 17 (22.1) | 26 (33.8) | 0.685 |

| ≥50 | 34 (44.2) | 15 (19.5) | 19 (24.7) | |

| Tumor size, cm | ||||

| ≤2 | 17 (25.0) | 6 (7.8) | 11 (14.3) | 0.267 |

| 2~5 | 45 (58.4) | 17 (22.1) | 28 (36.4) | |

| ≥5 | 15 (19.5) | 9 (11.7) | 6 (7.8) | |

| Histological status | ||||

| I | 19 (24.7) | 3 (3.9) | 16 (20.8) | 0.012 |

| II | 48 (62.3) | 22 (28.6) | 26 (33.8) | |

| III | 10 (13.0) | 7 (9.1) | 3 (3.9) | |

| Lymph node status | ||||

| 0 | 22 (28.6) | 4 (5.2) | 18 (23.4) | 0.031 |

| 1-3 | 40 (51.9) | 20 (26.0) | 20 (26.0) | |

| ≥4 | 15 (19.5) | 8 (10.4) | 7 (9.1) | |

| ER | ||||

| Positive | 38 (49.4) | 14 (18.2) | 22 (31.2) | 0.407 |

| Negative | 39 (50.6) | 18 (23.4) | 23 (27.3) | |

| PR | ||||

| Positive | 42 (54.5) | 14 (18.2) | 28 (36.4) | 0.109 |

| Negative | 35 (45.5) | 18 (23.4) | 17 (22.1) | |

| HER2 | ||||

| Positive | 14 (18.2) | 3 (3.9) | 11 (14.3) | 0.091 |

| Negative | 63 (81.8) | 29 (37.7) | 34 (44.2) | |

TYMS, thymidylate synthase; ER, estrogen receptor; PR, progesterone receptor; HER-2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2. Two-sides Chi-square tests were used.

Clinical response and TYMS expression

The duration of response to pemetrexed chemotherapy in TYMS-high group was shorter than TYMS-low group (10.60 vs. 16.95 months, P<0.001; Fig. 2A). TYMS-high patients showed significant lower overall response rate (ORR) compared with TYMS-low ones (3.13 vs. 46.67%, P<0.001; Fig. 2B). TYMS-high patients also showed significant lower DCR than TYMS-low ones (40.63 vs. 82.22%, P<0.001; Fig. 2C). Notably, significantly higher TYMS scores were observed in the disease-progression patients in comparison with those responses to chemotherapy (P=0.0002; Fig. 2D).

Figure 2.

The correlation between TYMS expression and pemetrexed chemotherapy response. (A) The duration time of response to pemetrexed chemotherapy in TYMS-high group and TYMS-low group (P<0.001). (B) Overall response rate (ORR) of TYMS-high patients and TYMS-low patients (P<0.001). (C) Disease control rate (DCR) of TYMS-high patients and TYMS-low patients, P<0.001. (D) TYMS scores of the patients between disease-progression patients (Progression) and those responses to pemetrexed chemotherapy (Response), (P=0.0002). Data were analyzed with x2 test.

Relationship between therapeutic outcomes and TYMS expression

Univariate and multivariate analysis were performed to evaluate therapeutic outcomes of pemetrexed treated patients. As shown in Table III, elevated TYMS expression significantly correlated with poor PFS (HR, 4.775; 95% CI, 2.004-11.379, P<0.001) and OS (HR, 3.786; 95% CI, 1.734-8.265; P=0.001). Multivariate analysis also showed that high TYMS expression was a detrimental factor in DFS (HR, 4.321; 95% CI, 1.442-12.943; P=0.009), and also for OS (HR, 4.569; 95% CI, 1.657-12.595; P=0.003). Moreover, ER expression was also correlated to a better prognosis for pemetrexed treated advanced breast cancer patients in multivariate analysis (HR, 0.139; 95% CI, 0.027-0.706; P=0.017). However, HER2 expression was a detrimental factor for both DFS and OS (HR, 4.281; 95% CI, 1.222-14.996; P=0.023; HR, 5.035; 95% CI, 1.686-15.040; P=0.004).

Table III.

Cox regression analyses of disease-free survival and overall survival for TYMS expression.

| DFS | OS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable analysis | HR | 95.0% CI | P | HR | 95.0% CI | P |

| Univariate | ||||||

| TYMS | 4.775 | 2.004-11.379 | <0.001 | 3.786 | 1.734-8.265 | 0.001 |

| Multivariate | ||||||

| Age | 1.235 | 0.449-3.401 | 0.683 | 1.541 | 0.610-3.893 | 0.361 |

| Size | 1.132 | 0.409-3.133 | 0.812 | 1.172 | 0.481-2.857 | 0.727 |

| LNM | 3.950 | 0.833-18.739 | 0.084 | 3.726 | 0.824-16.845 | 0.088 |

| Grade | 0.761 | 0.194-2.982 | 0.695 | 1.179 | 0.308-4.514 | 0.810 |

| ER | 0.139 | 0.027-0.706 | 0.017 | 0.385 | 0.100-1.481 | 0.165 |

| PR | 1.188 | 0.322-4.376 | 0.796 | 0.847 | 0.229-3.132 | 0.804 |

| HER2 | 4.281 | 1.222-14.996 | 0.023 | 5.035 | 1.686-15.040 | 0.004 |

| TYMS | 4.321 | 1.442-12.943 | 0.009 | 4.569 | 1.657-12.595 | 0.003 |

HR, hazard ratios; CI, confidence interval; TYMS, Thymidylate synthase; LNM, Lymph node metastasis; ER, estrogen receptor; PR, progesterone receptor; HER-2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2. The variables were compared in the following ways: Age, >44 years vs. ≤44 years; size, >5 cm vs. ≤5 cm; Grade, G2-3 vs. G1; ER, PR and HER2, positive vs. negative; TYMS, high vs. low.

Discussion

Pemetrexed chemotherapy was a choice for advanced breast cancer patients (13). However, only a part of patients benefit from pemetrexed chemotherapy. Our study indicated that TYMS expression correlated with high histopathological grade and lymph node metastasis. More importantly, high TYMS expression predicts therapeutic sensitivity of pemetrexed chemotherapy in advanced breast cancer, suggesting that it may be a useful biomarker to choose chemotherapy regimens.

Anthracycline- and taxane-based chemotherapy regimens is a common treatment for advanced breast cancer. As a third-line chemotherapy specimen, pemetrexed is a multitarget anti-metabolite chemotherapy drug that inhibits folate metabolism and DNA synthesis enzymes. It has been widely used in non-small cell lung cancer, gastrointestinal cancer during recent years (14–16). However, variable treatment response of pemetrexed chemotherapy was observed in patients with different pathological type of tumors (17). Here in this study, 77 patients with advanced breast cancer who received pemetrexed chemotherapy were evaluated for treatment efficiency. The ORR of these patients was 31.17% and DCR was 64.94%, which were similar to the efficacy of pemetrexed combined with cyclophosphamide in the treatment of advanced breast cancer (6). A large proportion of patients suffered disease progression during pemetrexed treatment (5,17). Thus, appropriate chemotherapy options are valuable for advanced breast cancer patients.

Previous studies have shown that gene expression differences are responsible for chemotherapeutic response variability between individuals (18). Selected patients according to biomarker will improve the chemotherapy efficacy (19). TYMS participates in deoxythymidine monophosphate synthesis, which is critical for DNA synthesis and repair. Breast cancer specimens have showed increased mRNA and protein expression level of TYMS. The breast cancer with TYMS expression showed a significant aggressive phenotype and poor prognosis (20,21). Among the 77 patients in this study, the TYMS scores are variable from 0 to 2 by IHC staining, suggesting the diversity of TYMS expression in different breast cancer patients. Elevated TYMS expression is correlated with high histological grade and lymph node metastasis, rather than ER, PR and HER2 expression, which is consistent with previous report (22). Our study indicated that TYMS was involved in disease progression and treatment resistance of advanced breast cancer (23).

As a multitargeted antifolate, pemetrexed inhibits several de novo synthesis enzymes for purine and pyrimidine, including TYMS. Previous clinical and in vitro studies showed that cancer cell lines with TYMS expression showed poor sensitivity to cisplatin- and taxane-based chemotherapy regimens (24,25). Pemetrexed treatment in non-small cell lung cancer patients indicated that low TYMS mRNA expression was associated with increased ORR (26), and TYMS was an appropriate biomarker for pemetrexed chemotherapy response in non-small cell lung cancer (9,10,27). Furthermore, breast cancer with elevated TYMS expression showed poor prognosis in a long-term follow-up study (10,28). Our study indicated that the expression of TYMS was correlated with treatment resistance to pemetrexed in advanced breast cancer. More importantly, significantly elevated TYMS expression was observed in the patients with resistance than those with objective response. Moreover, TYMS low expression group showed significantly higher ORR than those with high expression group. Consistent with above conclusions, our study further confirmed that TYMS is an important marker for pemetrexed chemotherapy efficacy. Previous studies suggested pemetrexed resistance correlated with membrane transport deficiency and acidic microenvironment (7,29). Further studies will be performed to verify their correlation to TYMS expression.

As a candidate option, pemetrexed chemotherapy efficacy provided a promising choice for advanced breast cancer patients (6,30). However, our study only analyzed short-term clinical efficacy of pemetrexed treatment of advanced breast cancer due to limited cases and short observation time. Moreover, it was reported that breast cancer patients with TYMS polymorphism of a 6-bp deletion within TYMS 3′-UTR would benefit from 5-FU and capecitabine chemotherapy (28,31–33). Further studies will be employed to analyze the long-term efficacy and gene sequencing in the future, which will provide a firm evidence for best chemotherapy options by detecting TYMS expression levels.

In conclusion, TYMS expression levels predicts therapeutic sensitivity of pemetrexed chemotherapy in advanced breast cancer. The breast cancer cells with high TYMS expression are more likely resistant to pemetrexed chemotherapy. These patients should be excluded from pemetrexed chemotherapy candidate.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Department of Pathology of The Second Hospital of Shandong University for their helpful assistance.

Funding

This study was supported by granst from Shinan District of Science and Technology plan item 2016-3-020-YY and National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81502283).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

Preparation of the tissue microarrays, IHC staining and clinical data collection were performed by FS and YLS. The slides were analyzed by YLL and QW. Statistical analysis was performed by FS and QW. The manuscript was written by FS and QW.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the Ethical and Protocol Review Committee of The Second Hospital of Shandong University. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Second Hospital of Shandong University and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Van Poznak C, Somerfield MR, Bast RC, Cristofanilli M, Goetz MP, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Hicks DG, Hill EG, Liu MC, Lucas W, et al. Use of biomarkers to guide decisions on systemic therapy for women with metastatic breast cancer: American society of clinical oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2695–2704. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khatcheressian JL, Hurley P, Bantug E, Esserman LJ, Grunfeld E, Halberg F, Hantel A, Henry NL, Muss HB, Smith TJ, et al. Breast cancer follow-up and management after primary treatment: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:961–965. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.9859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deng QQ, Huang XE, Ye LH, Lu YY, Liang Y, Xiang J. Phase II trial of Loubo® (Lobaplatin) and pemetrexed for patients with metastatic breast cancer not responding to anthracycline or taxanes. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:413–417. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2013.14.1.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garin A, Manikhas A, Biakhov M, Chezhin M, Ivanchenko T, Krejcy K, Karaseva V, Tjulandin S. A phase II study of pemetrexed and carboplatin in patients with locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;110:309–315. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9722-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Llombart-Cussac A, Theodoulou M, Rowland K, Clark RS, Nakamura T, Carrasco E, Cruciani G. Pemetrexed in patients with locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer who had received previous anthracycline and taxane treatment: Phase II study. Clin Breast Cancer. 2006;7:380–385. doi: 10.3816/CBC.2006.n.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dittrich C, Solska E, Manikhas A, Eniu A, Tjulandin S, Anghel R, Musib L, Frimodt-Moller B, Liu Y, Krejcy K, Láng I. A phase II multicenter study of two different dosages of pemetrexed given in combination with cyclophosphamide as first-line treatment in patients with locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Invest. 2012;30:309–316. doi: 10.3109/07357907.2012.658938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vandana M, Sahoo SK. Reduced folate carrier independent internalization of PEGylated pemetrexed: A potential nanomedicinal approach for breast cancer therapy. Mol Pharm. 2012;9:2828–2843. doi: 10.1021/mp300131t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pandyra AA, Berg R, Vincent M, Koropatnick J. Combination silencer RNA (siRNA) targeting Bcl-2 antagonizes siRNA against thymidylate synthase in human tumor cell lines. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;322:123–132. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.115394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang M, Fan WF, Pu XL, Meng LJ, Wang J. The role of thymidylate synthase in non-small cell lung cancer treated with pemetrexed continuation maintenance therapy. J Chemother. 2017;29:106–112. doi: 10.1080/1120009X.2016.1254940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen CY, Chang YL, Shih JY, Lin JW, Chen KY, Yang CH, Yu CJ, Yang PC. Thymidylate synthase and dihydrofolate reductase expression in non-small cell lung carcinoma: The association with treatment efficacy of pemetrexed. Lung Cancer. 2011;74:132–138. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akbar S, Jordan LB, Purdie CA, Thompson AM, McKenna SJ. Comparing computer-generated and pathologist-generated tumour segmentations for immunohistochemical scoring of breast tissue microarrays. Br J Cancer. 2015;113:1075–1080. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fukushima M, Morita M, Ikeda K, Nagayama S. Population study of expression of thymidylate synthase and dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase in patients with solid tumors. Int J Mol Med. 2003;12:839–844. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Llombart-Cussac A, Martin M, Harbeck N, Anghel RM, Eniu AE, Verrill MW, Neven P, De Grève J, Melemed AS, Clark R, et al. A randomized, double-blind, phase II study of two doses of pemetrexed as first-line chemotherapy for advanced breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:3652–3659. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richards DA, Loesch D, Vukelja SJ, Wu H, Hyman WJ, Nieves J, Wang Y, Hu S, Shonukan OO, Tai DF. Phase I study of pemetrexed and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in patients with refractory breast, ovarian, primary peritoneal, or fallopian tube cancer. Invest New Drugs. 2011;29:963–970. doi: 10.1007/s10637-010-9414-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jensen SA, Vainer B, Witton CJ, Jørgensen JT, Sørensen JB. Prognostic significance of numeric aberrations of genes for thymidylate synthase, thymidine phosphorylase and dihydrofolate reductase in colorectal cancer. Acta Oncol. 2008;47:1054–1061. doi: 10.1080/02841860801942158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Le François BG, Maroun JA, Birnboim HC. Expression of thymidylate synthase in human cells is an early G(1) event regulated by CDK4 and p16INK4A but not E2F. Br J Cancer. 2007;97:1242–1250. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robert NJ, Conkling PR, O'Rourke MA, Kuefler PR, McIntyre KJ, Zhan F, Asmar L, Wang Y, Shonukan OO, O'Shaughnessy JA. Results of a phase II study of pemetrexed as first-line chemotherapy in patients with advanced or metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;126:101–108. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1286-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Denduluri N, Somerfield MR, Eisen A, Holloway JN, Hurria A, King TA, Lyman GH, Partridge AH, Telli ML, Trudeau ME, Wolff AC. Selection of optimal adjuvant chemotherapy regimens for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-negative and adjuvant targeted therapy for HER2-positive breast cancers: An American Society of Clinical Oncology Guideline adaptation of the cancer care ontario clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2416–2427. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.0182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krop I, Ismaila N, Andre F, Bast RC, Barlow W, Collyar DE, Hammond ME, Kuderer NM, Liu MC, Mennel RG, et al. Use of biomarkers to guide decisions on adjuvant systemic therapy for women with early-stage invasive breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Focused Update. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:2838–2847. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.74.0472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu Z, Sun J, Zhen J, Zhang Q, Yang Q. Thymidylate synthase predicts for clinical outcome in invasive breast cancer. Histol Histopathol. 2005;20:871–878. doi: 10.14670/HH-20.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaira K, Okumura T, Ohde Y, Takahashi T, Murakami H, Kondo H, Nakajima T, Yamamoto N. Prognostic significance of thymidylate synthase expression in the adjuvant chemotherapy after resection for pulmonary metastases from colorectal cancer. Anticancer Res. 2011;31:2763–2771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takagi K, Miki Y, Nakamura Y, Hirakawa H, Kakugawa Y, Amano G, Watanabe M, Ishida T, Sasano H, Suzuki T. Immunolocalization of thymidylate synthase as a favorable prognostic marker in estrogen receptor-positive breast carcinoma. Histol Histopathol. 2015;30:1223–1232. doi: 10.14670/HH-11-619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marverti G, Ligabue A, Paglietti G, Corona P, Piras S, Vitale G, Guerrieri D, Luciani R, Costi MP, Frassineti C, Moruzzi MS. Collateral sensitivity to novel thymidylate synthase inhibitors correlates with folate cycle enzymes impairment in cisplatin-resistant human ovarian cancer cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;615:17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.04.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Calascibetta A, Martorana A, Cabibi D, Aragona F, Sanguedolce R. Relationship between thymidylate synthase and p53 and response to FEC versus taxane adjuvant chemotherapy for breast carcinoma. J Chemother. 2011;23:354–357. doi: 10.1179/joc.2011.23.6.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quintero-Ramos A, Gutiérrez-Rubio SA, Del Toro-Arreola A, Franco-Topete RA, Oceguera-Villanueva A, Jiménez-Pérez LM, Castro-Cervantes JM, Barragán-Ruiz A, Vázquez-Camacho JG, Daneri-Navarro A. Association between polymorphisms in the thymidylate synthase gene and risk of breast cancer in a Mexican population. Genet Mol Res. 2014;13:8749–8756. doi: 10.4238/2014.October.27.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shimizu T, Nakanishi Y, Nakagawa Y, Tsujino I, Takahashi N, Nemoto N, Hashimoto S. Association between expression of thymidylate synthase, dihydrofolate reductase, and glycinamide ribonucleotide formyltransferase and efficacy of pemetrexed in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:4589–4596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ceppi P, Papotti M, Scagliotti G. New strategies for targeting the therapy of NSCLC: The role of ERCC1 and TS. Adv Med Sci. 2010;55:22–25. doi: 10.2478/v10039-010-0017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee SJ, Choi YL, Park YH, Kim ST, Cho EY, Ahn JS, Im YH. Thymidylate synthase and thymidine phosphorylase as predictive markers of capecitabine monotherapy in patients with anthracycline- and taxane-pretreated metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2011;68:743–751. doi: 10.1007/s00280-010-1545-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li L, Sham YY, Bikadi Z, Elmquist WF. pH-dependent transport of pemetrexed by breast cancer resistance protein. Drug Metab Dispos. 2011;39:1478–1485. doi: 10.1124/dmd.111.039370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wan F, Chen X, Dong LF, Cheng YH, Long JP. A systemic analysis on pemetrexed in treating patients with breast cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:4567–4570. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.11.4567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fujishima M, Inui H, Hashimoto Y, Azumi T, Yamamoto N, Kato H, Hojo T, Yamato M, Matsunami N, Shiozaki H, Watatani M. Relationship between thymidylate synthase (TYMS) gene polymorphism and TYMS protein levels in patients with high-risk breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 2010;30:4373–4739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.da Silva Nogueira J, Jr, de Lima Marson FA, Silvia Bertuzzo C. Thymidylate synthase gene (TYMS) polymorphisms in sporadic and hereditary breast cancer. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:676. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang B, Walsh SJ, Saif MW. Pancytopenia and severe gastrointestinal toxicities associated with 5-fluorouracil in a patient with Thymidylate Synthase (TYMS) Polymorphism. Cureus. 2016;8:e798. doi: 10.7759/cureus.798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.