Abstract

Engagement in intimate social interactions and relationships has an important influence on well-being. However, recent advances in Internet and mobile communication technologies have lead to a major shift in the mode of human social interactions, raising the question of how these technologies are impacting the experience of interpersonal intimacy and its relationship with well-being. Although the study of intimacy in online social interactions is still in its early stages, there is general agreement that a form of online intimacy can be experienced in this context. However, research into the relationship between online intimacy and well-being is critically limited. Our aim is to begin to address this research void by providing an operative perspective on this emerging field. After considering the characteristics of online intimacy, its multimodal components and its caveats, we present an analysis of existing evidence for the potential impact of online intimacy on well-being. We suggest that studies thus far have focused on online social interactions in a general sense, shedding little light on how the level of intimacy in these interactions may affect well-being outcomes. We then consider findings from studies of different components of intimacy in online social interactions, specifically self-disclosure and social support, to indirectly explore the potential contribution of online intimacy to health and well-being. Based on this analysis, we propose future directions for fundamental and practical research in this important new area of investigation.

Keywords: Online intimacy, Online interactions, Online social support, Online self-disclosure, Well-being

Highlights

-

•

Intimacy in social interactions has an important influence on health and well-being.

-

•

A form of intimacy can be experienced in online interactions.

-

•

Research into the relationship between online intimacy and well-being is critically limited.

-

•

Analysis of components of intimacy sheds light on its contribution to health and well-being.

-

•

Future directions for fundamental and practical research are proposed.

1. Introduction

Engagement in meaningful and intimate social interactions and relationships is one of the key components through which social factors influence general health and well-being (Berkman et al., 2000, Cohen, 2004, Helliwell and Putman, 2004, Holt-Lunstad et al., 2010, Kawachi and Berkman, 2001, Ryff and Singer, 2000). However, the recent and widespread integration of Internet and mobile communication technologies into our daily lives is changing the principal modalities through which we engage with others (Amichai-Hamburger, 2013, Steinfield et al., 2012, Zhong, 2011). In light of these changes, it is critical to consider how interpersonal intimacy experienced in the context of online social engagement may influence health and well-being outcomes in the digital age.

Social factors act at multiple levels to influence health and well-being, including upstream effects of social-structural conditions (e.g., cultural and socioeconomic factors) and social network characteristics (e.g., size, density, reciprocity), as well as downstream effects of psychosocial mechanisms of interpersonal behavior, including intimate interactions (Berkman et al., 2000). These effects ultimately converge at behavioral, psychological and physiological pathways that are linked more directly to particular health and well-being outcomes. Similarly, the social contexts of the Internet can be considered at multiple levels, from the explosion in the capacity for social connectivity enabled by online social networking applications (Dunbar, 2012, Steinfield et al., 2012) to interactions that facilitate interpersonal disinhibition and intimate self-disclosure (Jiang et al., 2011, Joinson and Paine, 2007, Ledbetter et al., 2011, Shim et al., 2011). While online social networking can increase one's social capital (Ellison et al., 2007, Steinfield et al., 2008), increased connectivity, however, does not necessarily translate to an increase in meaningful social connections (Dunbar, 2012). This has been described by some as the condition of being “alone together” (Ducheneaut et al., 2006, Schultze, 2010). Conversely, factors such as increased online disinhibition and self-disclosure favor online intimacy (Jiang et al., 2011, McKenna et al., 2002, Valkenburg and Peter, 2011), promoting increased satisfaction in online interpersonal interactions (Bane et al., 2010, Ko and Kuo, 2009). Thus, certain aspects of Internet-mediated interactions can facilitate meaningful and intimate social interactions, highlighting the potential of this medium for cultivating well-being through high-quality social engagement online.

The existing literature on the impact of the social use of the Internet on psychological health and well-being points to both benefits and draw-backs of this medium of social interaction (Bessiere et al., 2010, Kang, 2007, Moody, 2001, Shaw and Gant, 2002, van den Eijnden et al., 2008). However, there has been little consideration of the quality or the intimacy of different online interactions in relation to health and well-being outcomes. Furthermore, there has been no systematic exploration of the specific relationship between online intimacy and well-being. In light of this research void, the aim of this review is to consider the existing evidence in this emerging field to identify potential starting points for more systematic research in order to understand how online intimacy may influence well-being in the digital age.

We begin by considering the concept of intimacy in the digital age by identifying the characteristics of intimacy in online social interactions, its multimodal components and its caveats. We then summarize the evidence for the influence of online social interactions on health and well-being outcomes and consider findings from studies of different components of intimacy in online social interactions, mainly self-disclosure and social support, to shed light on the potential contribution of online intimacy to health and well-being. Finally, we discuss future directions for fundamental and practical research in this important new field.

2. Interpersonal intimacy in the digital age

2.1. Characterizing online intimacy

Interpersonal intimacy is regarded to be at the core of the most fulfilling, affirming, and gratifying human social exchanges (Prager, 1995, Ryff and Singer, 2000, Sperry, 2010). It is commonly related to a number of comparable concepts, such as love, closeness, self-disclosure, support, bonding, attachment, and sexuality, with the boundaries between them often considered to be continuous rather than distinct (Prager, 1995, Sperry, 2010). Although a number of definitions of the concept of intimacy exist (Register and Henley, 1992, Reis and Shaver, 1988, Waring, 1985, Wilhelm and Parker, 1988), in a broad sense, intimacy can be defined as a dyadic exchange that involves sharing what is personal and private (Prager, 1995). It can be realized in the context of intimate interactions and relationships that encompass both verbal and non-verbal communication, as well as shared behavioral, physical, emotional, and cognitive experience (Prager, 1995).

Advances in Internet-based communication and social networking applications over the last several decades have lead to a major shift in the mode of human social engagement (Amichai-Hamburger, 2013, Steinfield et al., 2012, Zhong, 2011). This shift has resulted in new ways to experience and actualize intimacy, both in the context of pre-existing relationships and interactions with strangers. Physical proximity and direct face-to-face contact are becoming less prevalent in day to day interpersonal interactions with close individuals (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2010, McPherson et al., 2006, Putnam, 2000). This is indicated by changes in family lifestyles, including increased numbers of dual-career families, reduced intergenerational living, greater mobility, delayed marriage, and the increase in single-residence households, as well as by the increase in the number of individuals who report not having a confidant (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2010, McPherson et al., 2006, Putnam, 2000). In contrast, Internet and mobile applications such as email, instant messaging, and video chat have become the mainstays of daily social contact with family and friends (Broadbent, 2012, Wilding, 2006). Likewise, social networking platforms, such as Facebook and Twitter, have amassed millions of users throughout the world (Ellison et al., 2007, Pujazon-Zazik and Park, 2010, Steinfield et al., 2008) and multiuser virtual environments, such as massive multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPGs) and other virtual social platforms, have become one of the most popular forms of online social entertainment (Cole and Griffiths, 2007, Ducheneaut et al., 2006, Zhong, 2011).

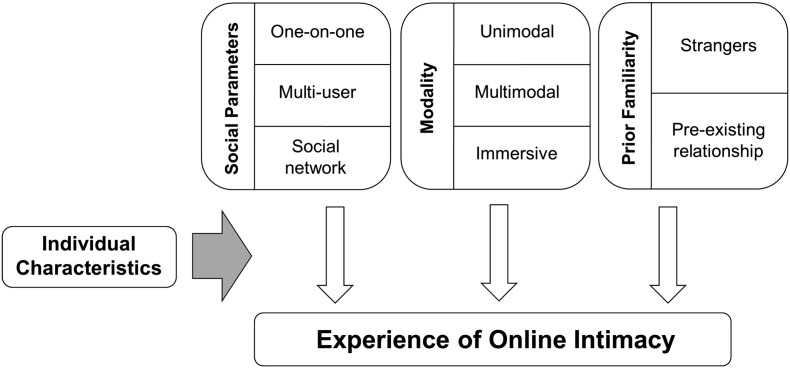

Since the early days of the Internet, researchers have questioned whether it would be possible to foster intimate relationships using this medium (Kiesler et al., 1984, Rice and Love, 1987). It is now evident that the development and maintenance of friendships and romantic relationships online is common and that these relationships can be similar in meaning, intimacy, and stability in comparison to conventional offline relationships (Broadbent, 2012, Ellison et al., 2007, Hsu et al., 2011, McKenna et al., 2002, Pace et al., 2010, Parks and Roberts, 1998, Whitty, 2008, Whitty, 2013). However, online contexts vary according to the features of different platforms, such as the number of participants (social parameters), the modalities of interaction (text, audio, video, etc.), or whether they facilitate contact and establishment of new relationships between strangers or the maintenance of existing offline relationships. Individual differences can also influence which online contexts users prefer and how they engage with others online (Amichai-Hamburger and Hayat, 2013, McKenna et al., 2002, Nadkarni and Hofmann, 2012). Therefore, a number of factors may influence the way in which intimacy is expressed and perceived by users in interpersonal exchanges online. Owing to the relative novelty of this field of research, there are still many outstanding questions regarding the contribution of these factors to the experience of online intimacy. For instance, what is the frequency of occurrence of intimacy in different online contexts and how does this differ from the occurrence of intimacy in conventional offline contexts? How do the modalities of interaction and the richness of the media, from text-based to immersive, contribute to the occurrence of online intimacy? Does the experience of intimacy differ when interacting with individuals who we already know offline compared to those we meet online? Although the lack of evidence to answer these types of questions does not permit an elaboration of a concrete model of online intimacy at this point, we summarize some of the factors that are important to consider in understanding how intimacy is experienced online in Fig. 1. We discuss these factors in more detail below.

Fig. 1.

Potential factors influencing the experience of online intimacy. A number of factors may influence the experience of online intimacy, including social parameters, modality, and prior familiarity. Social parameters refer to the online context in which interpersonal interactions occur, including one-on-one, multi-user or social networking contexts. Prior familiarity relates to online interactions either with strangers or with individuals with whom one has a prior offline relationship. Modality encompasses the physical features of the online setting, including unimodal text-based platforms, multimodal text, audio and video platforms, or immersive 3-dimensional online environments. Finally, individual characteristics modulate the perception of the different features of online contexts to influence the experience of online intimacy.

2.2. Intimacy in new relationships established online

Many Internet and mobile applications facilitate social contact between strangers. Certain types of online platforms, such as online dating websites (e.g., eHarmony, PlentyOfFish) and mobile applications (e.g., Tinder), are specifically designed to facilitate meeting strangers for the purpose of subsequently establishing intimate interactions and relationships offline. Finkel et al. (2012) provide a comprehensive review of advantages and disadvantages of online dating for meeting potential partners online and subsequent relationship outcomes. Other platforms, that are not designed for this purpose, can nevertheless foster intimacy online. In particular, by preserving anonymity online contexts can promote the disclosure of personal information, opinions, and feelings much more readily than in face-to-face interactions (Joinson, 2001, McKenna et al., 2002). Meeting and maintaining interactions online also enables individuals to overcome certain “gating features” that may otherwise deter them from engaging with others, such as personal characteristics related to sex, gender, age, race, any physical features of appearance, disability, or any form of real or perceived stigma (McKenna et al., 2002). In particular, in many online multi-user virtual worlds or role-playing games, users are able to create avatars that portray personas as similar to or as different from themselves as they choose by varying their appearance, gender, species or form (Guitton, 2012b, Guitton, 2015, Lomanowska and Guitton, 2012). These online social platforms also allow individuals to share common experiences as they explore virtual settings together or participate in role-playing games (Chen et al., 2008, Guitton, 2012b, Guitton, 2015). Taken together, these features of online interactions between strangers can actually accelerate intimacy formation in comparison to offline contexts (Genuis and Genuis, 2005, Rosen et al., 2008). Indeed, as is the case for online dating websites (Finkel et al., 2012), relationships formed and maintained in other online contexts can lead to subsequent face-to-face interactions that continue to develop in the real world, and in some cases they have been shown to lead to lasting romantic partnerships and marriages (Baker, 2002, Cole and Griffiths, 2007, Ramirez and Zhang, 2007).

2.3. Online intimacy and existing offline relationships

Much of the social interactions occurring via the Internet and mobile applications involve pre-existing offline relationships (Broadbent, 2012, Ellison et al., 2007, McDaniel and Drouin, 2015, Valkenburg and Peter, 2011, Wilding, 2006). For instance, the most popular social networking websites, such as Facebook, mostly promote interactions within existing relationships as users are typically not anonymous (Ellison et al., 2007, Hsu et al., 2011, Subrahmanyam et al., 2008). Social networking also facilitates the maintenance of weak ties between acquaintances, but does not typically increase the level of intimacy in these relationships (Ellison et al., 2007, Hsu et al., 2011). Therefore, in these contexts, individuals generally engage in more intimate online behavior with those who they are already close to offline (Hsu et al., 2011). Furthermore, various digital applications are commonly used as a means of maintaining long-distance relationships with family and friends, fostering a sense of belonging, shared space and time, and perceived proximity (Bacigalupe and Lambe, 2011, Madianou and Miller, 2012, Vetere et al., 2005, Wilding, 2006). As with social networking interactions, the existing nature and closeness of offline relationships is generally maintained in electronic exchanges (Wilding, 2006), although in the case of established close relationships, online communication can actually enhance intimate self-disclosure (Valkenburg and Peter, 2007). Overall, the distinction between online and offline social engagement and intimacy among individuals who have a prior relationship is becoming somewhat blurred, with online interactions becoming an extension of offline relationships (Ellison et al., 2007, Hsu et al., 2011, Subrahmanyam et al., 2008).

2.4. Multimodal aspects of online intimacy

Although the existing evidence indicates that Internet technologies can facilitate online intimacy, it is important to consider how the multimodal characteristics of these new media affect the quality of the individual experience of intimacy. Internet media differ according to the number of individuals that one can interact with, including interacting one-on-one, with a select group of individuals, or within a massively multi-user context. As well, Internet-based communication interfaces can vary according to the modalities used, from unimodal asynchronous interfaces (e.g., email, text messaging) to synchronous multimodal (e.g., video chat or fully immersive settings such as virtual environments). For instance, increasing the modalities of media that are used by a virtual community is related to an increase in the potential for inter-individual connections (Guitton, 2012a), while the potential for shared social experiences as measured by increased social density is related to the redundancy of communication within a medium (Guitton, 2015).

One important difference between intimate exchanges online and offline is the lack of physical proximity and contact between online partners. Advances in virtual reality technology have enhanced the immersiveness of online experience in a way that mimics some aspects of physical proximity and contact between individuals. The use of 3D human-like avatars in currently available online virtual world interfaces allows for simulated physical interactions between individuals that are realistic in nature (Cole and Griffiths, 2007, Gottschalk, 2010). Even though these interactions are perceived mainly through visual and auditory stimulation, individuals can experience a sense of embodiment within their own avatar as well as the ‘palpable’ presence of another person through symbolic sensation of awareness and contact (Pace et al., 2010, Schultze, 2010). With the addition of haptic feedback devices to these virtual interfaces, actual tactile sensation can also be incorporated into the virtual experience (Bailenson et al., 2007). Alternatively, the digital transmission of intimate physical contact has also been explored through the use physical objects that are integrated with Internet-enabled devices (Vetere et al., 2005). Furthermore, recent developments in mobile technologies and augmented reality promise continued advancements in the digital simulation of conventional physical contact (Long et al., 2014).

It is important to note that distinguishing online intimacy from conventional offline intimacy does not necessarily mean that the definition of intimacy fundamentally differs in these two forms of communication (face-to-face vs. online), but rather that intimacy is actualized differently depending of the medium. Furthermore, recent work demonstrates that intimate interpersonal exchanges in the digital age regularly involve multiple modalities of communication, with online exchanges serving as an extension of conventional offline interactions (Broadbent, 2012, Broadbent, 2015) and with individuals seamlessly integrating multiple types of media in their digital exchanges (Madianou and Miller, 2012). Indeed, the contemporary expression of intimacy spans both the online and offline realms, with individuals supplementing conventional offline interactions with intimate contact through various types of media, including text and video messaging, social media, and virtual environments. The individual experience of interpersonal intimacy in the digital age involves a unique combination of media use based on applications, platforms and modalities (including both online and offline) that suit the particular needs of specific interactions and relationships.

2.5. Caveats of online intimacy

Despite the potential of the Internet to facilitate online intimacy, it also has a number of shortcomings as a medium for positive relational experience. While accelerated intimacy in anonymous online communication may facilitate relationship development, it may also lead to excessive self-disclosure, sexual disinhibition, and unrealistic expectations about online partners (Genuis and Genuis, 2005, Padgett, 2007, Whitty, 2008). At the same time, there is a greater inherent risk of encountering dishonesty, deceit, and exploitation in such anonymous interactions (Genuis and Genuis, 2005, Robson and Robson, 1998, Whitty and Joinson, 2009). Furthermore, as social networking applications become more integrated into everyday lives, the distinction between private and public space becomes blurred (Bateman et al., 2011), marring the appeal of online intimate disclosure and posing a risk to vulnerable individuals. In particular, the emergence of cyber-harassment, cyber-bullying and cyber-stalking among adolescents and adults poses a serious threat to positive online social engagement (Guan and Subrahmanyam, 2009, Whitty, 2008). Finally, the added sense of obligation or the perception of continued surveillance related to sustaining regular contact with family and friends via the Internet and digital media may in some cases reduce the satisfaction of maintaining intimate relationships using this medium (Madianou and Miller, 2012, Wilding, 2006). These concerns may compromise healthy relationship development and maintenance online and beyond the Internet realm. Nevertheless, the availability and continuous advancement of various platforms, applications, and websites designed for different types of social interactions has the potential to mitigate many of these shortcomings.

3. Relationship of online intimacy to health and well-being

The beneficial effects of social relationships have been observed across a wide range of physiological and mental health outcomes, with research particularly highlighting the importance of high-quality intimate social interactions (Berkman, 1995, Karelina and DeVries, 2011, Kawachi and Berkman, 2001, Ryff and Singer, 2000). However, research on the health impact of the social use of Internet technologies is still in its early stages, with studies focusing mainly on psychosocial outcomes. A number of studies have reported positive effects on psychosocial well-being related to online social interactions, including increased self-esteem and self-efficacy (LaRose et al., 2001, Shaw and Gant, 2002, Steinfield et al., 2008), better mood (Green et al., 2005), greater perceived social support and reduced loneliness (Kang, 2007, Reeves, 2000, Shaw and Gant, 2002), as well as lower incidence of depression and anxiety (Bessiere et al., 2010, LaRose et al., 2001, Selfhout et al., 2009, Shaw and Gant, 2002). Other studies have reported an opposite relationship between the social use of the Internet and psychosocial well-being, including increased loneliness and depression (Moody, 2001, van den Eijnden et al., 2008). These discrepancies are likely related to differences in the populations studied. In fact, the direction of the relationship between social use of the Internet and psychosocial well-being can vary depending on a number of factors, including the type of online social application used, the type of feedback received in online interactions, as well as sex, personality and social disposition, and the level of existing offline social engagement (Blais et al., 2008, Donchi and Moore, 2004, Morahan-Martin and Schumacher, 2003, Swickert et al., 2002, Valkenburg et al., 2006). However, studies so far have focused on online social interactions in a general sense, thus shedding little light on how the level of intimacy in these interactions may affect well-being outcomes.

3.1. Comparing online and offline intimacy

An important question to ask when considering the role of online intimacy in health and well-being is whether the features of intimacy that contribute to health-related outcomes differ between offline and online interactions. According to the characteristics of online intimacy described above, certain aspects of intimacy, such as self-disclosure can be experienced in various online settings, whereas others, such as physical contact are very difficult to convey virtually. In addition, the time-course of intimacy development online, particularly with respect to intimate self-disclosure, can often be accelerated compared to conventional offline contexts (Jiang et al., 2011, McKenna et al., 2002, Valkenburg and Peter, 2011). Therefore, in order to begin to elucidate whether online intimacy differs from offline intimacy with respect to its health effects, it is necessary to examine what is known regarding the contribution of different aspects of intimate interactions to health and well-being. Here we consider three aspects of intimate interactions which have been examined individually in the health and well-being literature, self-disclosure, social support and physical contact. We then consider how self-disclosure and social support in online contexts may influence health-related outcomes.

Self-disclosure (especially in the sense of confiding) and social support are thought to be particularly important in mediating the positive effects of intimacy on health and well-being (Prager, 1995, Reis and Franks, 1994, Robles and Kiecolt-Glaser, 2003, Ryff and Singer, 2000). Self-disclosure through talking or writing is known to be beneficial as a means of coping with negative emotions, conflict, stress, or traumatic events (Pennebaker, 1993, Pennebaker, 1999, Ryff and Singer, 2000). One of the immediate effects of self-disclosure is reduced autonomic nervous system activity, while the long-term benefits include enhanced immune function and improved physical and mental health (Pennebaker, 1999). Intimate interactions are also a vital source of social support, for instance, when one partner discloses personal feelings and the other provides understanding and reassurance (Reis and Franks, 1994, Ryff and Singer, 2000). Social support, particularly one's perceived availability of support, has received a lot of attention as an important mediator of many of the health benefits attributed to social engagement and intimacy (Berkman et al., 2000, Haber et al., 2007, Reis and Franks, 1994, Uchino et al., 1996). Social support encompasses many aspects, including emotional, instrumental, appraisal, and informational support. Intimate interactions are important in facilitating the emotional aspects of social support, which help individuals to gain confidence in their own ability to cope with distressing circumstances, thus enhancing self-efficacy and self-esteem (Berkman et al., 2000, Ryff and Singer, 2000).

Physical contact has also been shown to mediate some of the health benefits of intimate interactions (Ryff and Singer, 2000). Physical proximity, touching, massaging, hugging, holding hands or kissing, and sexual contact in the case of romantic partners, are important components of intimate interactions (Prager, 1995, Register and Henley, 1992). There is an extensive literature on the beneficial and therapeutic effects of physical contact drawing on both human and animal research (Duhn, 2010, Field, 2002, Fleming et al., 1999, Lomanowska et al., 2011). Physical contact is particularly influential in the context of parent-infant interactions (Charpak et al., 2005, Duhn, 2010), health care provision (Moyer et al., 2004, Wilkinson et al., 2002), and sexual and non-sexual contact between romantic partners (Brody, 2010, Ditzen et al., 2008, Grewen et al., 2005, Levin, 2007). For instance, warm physical contact has been shown to reduce stress reactivity among romantic partners (Ditzen et al., 2008, Grewen et al., 2005), while the frequency of sexual intercourse has been associated with a number of health benefits, including better mood and satisfaction with psychological well-being, increased analgesia, improved cardiovascular function and stress reactivity, decreased cancer risk, and longevity (Brody, 2010, Levin, 2007).

Overall, all three of the above features of intimate interactions have been shown to individually contribute positively to health-related outcomes. However, it is unclear at this time whether certain aspects of intimate interactions are more influential than others with respect to health and well-being, or whether they may exert their influence in concert.

3.2. Online self-disclosure and social support

Online contexts are known to promote and facilitate self-disclosure in interpersonal communication (Barak and Gluck-Ofri, 2007, Henderson and Gilding, 2004, Joinson and Paine, 2007). The health-related effects of self-disclosure online have been studied in the context of Internet support groups for individuals coping with various health and emotional issues (Barak and Gluck-Ofri, 2007, Shaw et al., 2006, Shim et al., 2011, Tichon and Shapiro, 2003). These studies indicate that self-disclosure in this context has positive effects on the users' emotional well-being and self-efficacy. Although little is known about the health benefits of self-disclosure in online relationships, there is evidence that self-disclosure on social networking sites and blogs can improve subjective well-being (Ko and Kuo, 2009, Lee et al., 2011) and can also promote the exchange of social support online (Barak and Gluck-Ofri, 2007, Ko and Kuo, 2009, Tichon and Shapiro, 2003).

Online contexts have also become popular settings for social support (Barak et al., 2008). The health effects of online social support have been primarily examined in individuals with health concerns who participate in online support communities. Participants of these communities have been shown to experience some benefits, such as an increased sense of self-efficacy and well-being as well as a reduction in negative mood and other symptoms of depression (Griffiths et al., 2009, Shaw et al., 2006, Shim et al., 2011). However, there is still a paucity of well-controlled studies to clearly evaluate the effectiveness of the Internet as a medium for social support (Griffiths et al., 2009). Thus, online interactions characterized by certain components of interpersonal intimacy may hold promise for enhancing health and well-being, but further research is necessary to carefully assess these outcomes.

Overall, surprisingly little attention has been given to the study of intimate online interactions in relation to their impact on health and well-being. At this time, one can only speculate about how the health and well-being effects of online intimacy compare to intimacy in conventional offline contexts. The challenge for future research in this area is to take advantage of existing knowledge regarding the influence of conventional intimate interactions on health and well-being to examine how online intimacy contributes to these outcomes.

4. Future directions for research

Future directions for research in this area encompass both fundamental questions regarding the nature of online intimacy compared to offline intimacy in the context of health and well-being as well as practical implications for psychologists and other practitioners. In order to promote more systematic study of the influence of online intimacy on health and well-being, it is important to continue to study online intimacy itself to more clearly characterize and understand this phenomenon. One starting point for this research is the development of instruments to assess online intimacy, for instance, to measure interest in seeking meaningful and lasting companionship through online relationships (Stanton et al., 2016). Another aspect that requires operationalization and the development of appropriate assessment measures relates to the actual experience of online intimacy, particularly in relation to the different features of online environments (Fig. 1). It is important to assess how individuals perceive and express intimacy in the context of different online interactions, ranging from shared communications in text-based settings to shared experiences of physical proximity and contact in more immersive online settings. We are currently conducting observational studies in online virtual worlds to examine how these environments enable physical proximity and contact and how individuals take advantage of these possibilities. Furthermore, while most research on online intimacy tends to focus on a single type of media, such as social networking, virtual worlds, or online dating, the reality of online social experience, even for the same individuals, is much more complex and typically involves multiple media. Therefore, in order to gain a clearer understanding of how online intimacy is experienced, future research will need to develop measures that establish more unified models. Importantly, an examination of online intimacy as an extension of conventional offline forms of intimacy will be important to consider in this unified approach.

A further important direction for future research is the incorporation of measures of well-being as well as interpersonal and/or relationship satisfaction into studies of online intimacy. This could be accomplished by using existing measurement tools, with necessary modifications (Diener et al., 2010, Ryff and Keyes, 1995, Vaughn and Matyastik Baier, 1999). In the same vein, studies aiming to better understand the role of social interactions and relationships in health and well-being would also benefit from including online social experiences in their assessments. In addition, it would also be important to examine physiological responses to intimate social interactions in online contexts in order to shed light on potential physiological mechanisms through which online intimacy may contribute to health and well-being, and to determine whether and how online experiences may differ in this regard from intimacy experienced in offline contexts.

Finally, as the study of the phenomenon of online intimacy continues, the question of the practical applicability of this emerging field also needs to be addressed. How do psychologists and other practitioners incorporate online intimacy into assessment and treatment approaches? How do the potential benefits and drawbacks of intimate social interactions online fit within the framework of promoting social engagement for better mental and physical health outcomes? How do individual differences contribute to experiences of intimacy in online and offline contexts? Addressing these and related questions is critical for updating psychological practice for the digital age.

5. Conclusion

As the nature of human social interactions in the digital age continues to evolve alongside ongoing advancements in Internet technologies, it is critical to gain a better understanding of the immediate and long-terms effects of these changes on health and well-being outcomes. Given the recognized importance of high quality intimate social interactions, particular focus on the influence of online intimacy on health and well-being is needed. Research to date demonstrates that intimate relationships formed online can indeed be similar in meaning, intimacy, and stability to conventional offline relationships and online contact can also enrich existing offline relationships. As well, augmented reality devices can be used to simulate some of physical aspects of intimate interactions. There is also evidence of positive psychosocial effects associated with online social interactions, including those characterized by key components of intimacy, self-disclosure and social support. However, little is still known about the benefits and risks of online intimacy in relation to health and well-being. Future work in this area should take advantage of exiting knowledge of the pathways mediating the wellness benefits of conventional offline intimate interactions to examine their involvement in online intimacy. Since many online social platforms have become well-established, assessment on a large scale of the long-term effects of online intimate social engagement on both psychological and physiological health and wellness outcomes has now become feasible. In order to ensure that the well-recognized benefits of interpersonal intimacy are sustained in modern society, research and wellness promotion programs must take into account the new digital realm of human social interactions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Meir Steiner for helpful comments on earlier versions of the manuscript. This work was supported by grants to AML and to MJG from the “Fonds de Recherche du Québec - Santé” (FRQ-S).

References

- Amichai-Hamburger Y. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2013. The social net: Understanding our online behavior. [Google Scholar]

- Amichai-Hamburger Y., Hayat Z. Internet and personality. In: Amichai-Hamburger Y., editor. The social net: Understanding our online behaviour. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2013. pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Bacigalupe G., Lambe S. Virtualizing intimacy: Information communication technologies and transnational families in therapy. Fam. Process. 2011;50:12–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2010.01343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailenson J.N., Yee N., Brave S., Merget D., Koslow D. Virtual interpersonal touch: Expressing and recognizing emotions through haptic devices. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2007;22:325–353. [Google Scholar]

- Baker A. What makes an online relationship successful? Clues from couples who met in cyberspace. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2002;5:363–375. doi: 10.1089/109493102760275617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bane C.M.H., Cornish M., Erspamer N., Kampman L. Self-disclosure through weblogs and perceptions of online and “real-life” friendships among female bloggers. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2010;13:131–139. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2009.0174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barak A., Gluck-Ofri O. Degree and reciprocity of self-disclosure in online forums. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2007;10:407–417. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2006.9938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barak A., Boniel-Nissim M., Suler J. Fostering empowerment in online support groups. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2008;24:1867–1883. [Google Scholar]

- Bateman P.J., Pike J.C., Butler B.S. To disclose or not: Publicness in social networking sites. Inform. Technol. People. 2011;24:78–100. [Google Scholar]

- Berkman L.F. The role of social relations in health promotion. Psychosom. Med. 1995;57:245–254. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199505000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman L.F., Glass T., Brissette I., Seeman T.E. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Soc. Sci. Med. 2000;51:843–857. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bessiere K., Pressman S., Kiesler S., Kraut R. Effects of internet use on health and depression: A longitudinal study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2010;12 doi: 10.2196/jmir.1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blais J.J., Craig W.M., Pepler D., Connolly J. Adolescents online: The importance of Internet activity choices to salient relationships. J. Youth Adolesc. 2008;37:522–536. [Google Scholar]

- Broadbent S. Approaches to personal communication. In: Horst H.A., Miller D., editors. Digital anthropology. Berg Publishers; New York: 2012. pp. 127–145. [Google Scholar]

- Broadbent S. Left Coast Press; Walnut Creek, CA: 2015. Intimacy at work: How digital media bring private life to the workplace. [Google Scholar]

- Brody S. The relative health benefits of different sexual activities. J. Sex. Med. 2010;7:1336–1361. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charpak N., Ruiz J.G., Zupan J., Cattaneo A., Figueroa Z., Tessier R., Cristo M., Anderson G., Ludington S., Mendoza S., Mokhachane M., Worku B. Kangaroo Mother Care: 25 years after. Acta Paediatr. 2005;94:514–522. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2005.tb01930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C.H., Sun C.T., Hsieh J. Player guild dynamics and evolution in massively multiplayer online games. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2008;11:293–301. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2007.0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. Social relationships and health. Am. Psychol. 2004;59:676–684. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.8.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole H., Griffiths M.D. Social interactions in massively multiplayer online role-playing gamers. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2007;10:575–583. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2007.9988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E., Wirtz D., Tov W., Kim-Prieto C., Choi D.-w., Oishi S., Biswas-Diener R. New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Soc. Indic. Res. 2010;97:143–156. [Google Scholar]

- Ditzen B., Hoppmann C., Klumb P. Positive couple interactions and daily cortisol: On the stress-protecting role of intimacy. Psychosom. Med. 2008;70:883–889. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318185c4fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donchi L., Moore S. It's a boy thing: The role of the internet in young peoples psychological wellbeing. Behav. Chang. 2004;21:76–89. [Google Scholar]

- Ducheneaut N., Yee N., Nickell E., Moore R.J. ACM; Montreal, Quebec, Canada: 2006. “Alone together?”: Exploring the social dynamics of massively multiplayer online games, proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems. [Google Scholar]

- Duhn L. The importance of touch in the development of attachment. Adv. Neonatal. Care. 2010;10:294–300. doi: 10.1097/ANC.0b013e3181fd2263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar R.I.M. Social cognition on the internet: Testing constraints on social network size. Philos. Trans. R. Soc., B. 2012;367:2192–2201. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2012.0121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison N.B., Steinfield C., Lampe C. The benefits of Facebook “friends:” social capital and college Students' use of online social network sites. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2007;12:1143–1168. [Google Scholar]

- Field T. Massage therapy. Med. Clin. North Am. 2002;86:163–171. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(03)00078-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel E.J., Eastwick P.W., Karney B.R., Reis H.T., Sprecher S. Online dating: a critical analysis from the perspective of psychological science. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest. 2012;13:3–66. doi: 10.1177/1529100612436522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming A.S., O'Day D.H., Kraemer G.W. Neurobiology of mother-infant interactions: Experience and central nervous system plasticity across development and generations. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 1999;23:673–685. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(99)00011-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genuis S.J., Genuis S.K. Internet interactions: Adolescent health and cyberspace. Can. Fam. Physician. 2005;51(329–331):334-336. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottschalk S. The presentation of avatars in second life: self and interaction in social virtual spaces. Symb. Interact. 2010;33:501–525. [Google Scholar]

- Green M.C., Hilken J., Friedman H., Grossman K., Gasiewskj J., Adler R., Sabini J. Communication via Instant Messenger: Short- and long-term effects. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2005;35:445–462. [Google Scholar]

- Grewen K.M., Girdler S.S., Amico J., Light K.C. Effects of partner support on resting oxytocin, cortisol, norepinephrine, and blood pressure before and after warm partner contact. Psychosom. Med. 2005;67:531–538. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000170341.88395.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, K.M., Calear, A.L., Banfield, M., 2009. Systematic review on Support Groups (ISGs) and depression (1): Do ISGs reduce depressive symptoms? J. Med. Internet Res. 11, e40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Guan S.S., Subrahmanyam K. Youth internet use: risks and opportunities. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2009;22:351–356. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32832bd7e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guitton M.J. The immersive impact of meta-media in a virtual world. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012;28:450–455. [Google Scholar]

- Guitton M.J. Living in the Hutt Space: Immersive process in the Star Wars Role-Play community of Second Life. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012;28:1681–1691. [Google Scholar]

- Guitton M.J. Swimming with mermaids: Communication and social density in the Second Life merfolk community. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015;48:226–235. [Google Scholar]

- Haber M., Cohen J., Lucas T., Baltes B. The relationship between self-reported received and perceived social support: A meta-analytic review. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2007;39:133–144. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9100-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helliwell J.F., Putman R.D. The social context of well–being. Philo. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2004;359:1435–1446. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson S., Gilding M. 'I've never clicked this much with anyone in my life': Trust and hyperpersonal communication in online friendships. New Media Soc. 2004;6:487–506. [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad J., Smith T.B., Layton J.B. Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review. PLoS Med. 2010;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu C.-W., Wang C.-C., Tai Y.-T. The closer the relationship, the more the interaction on Facebook? Investigating the case of Taiwan users. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2011;14:473–476. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2010.0267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L.C., Bazarova N.N., Hancock J.T. The disclosure–intimacy link in computer-mediated communication: An attributional extension of the hyperpersonal model. Hum. Commun. Res. 2011;37:58–77. [Google Scholar]

- Joinson A.N. Self-disclosure in computer-mediated communication: The role of self-awareness and visual anonymity. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001;31:177–192. [Google Scholar]

- Joinson A.N., Paine C.B. Self-disclosure, privacy and the Internet. In: Joinson A.N., McKenna K.Y.A., Postmes T., Reips U.-D., editors. The Oxford Handbook of Internet Psychology. Oxford University Press; New York: 2007. pp. 237–252. [Google Scholar]

- Kang S. Disembodiment in online social interaction: Impact of online chat on social support and psychosocial well-being. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2007;10:475–477. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2006.9929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karelina K., DeVries A.C. Modeling social influences on human health. Psychosom. Med. 2011;73:67–74. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3182002116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi I., Berkman L.F. Social ties and mental health. J. Urban Health. 2001;78:458–467. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.3.458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiesler S., Siegel J., McGuire T.W. Social psychological aspects of computer-mediated communication. Am. Psychol. 1984;39:1123–1134. [Google Scholar]

- Ko H.C., Kuo F.Y. Can blogging enhance subjective well-being through self-disclosure? Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2009;12:75–79. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2008.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaRose R., Eastin M.S., Gregg J. Reformulating the Internet paradox: Social cognitive explanations of Internet use and depression. J. Online Behav. 2001;1 [Google Scholar]

- Ledbetter A.M., Mazer J.P., DeGroot J.M., Meyer K.R., Mao Y., Swafford B. Attitudes toward online social connection and self-disclosure as predictors of Facebook communication and relational closeness. Commun. Res. 2011;38:27–53. [Google Scholar]

- Lee G., Lee J., Kwon S. Use of social-networking sites and subjective well-being: A study in South Korea. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2011;14:151–155. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2009.0382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin R.J. Sexual activity, health and well-being- the beneficial roles of coitus and masturbation. Sex Relat. Ther. 2007;22:135–148. [Google Scholar]

- Lomanowska A.M., Guitton M.J. Virtually naked: Virtual environment reveals sex-dependent nature of skin disclosure. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomanowska A.M., Melo A.I. Deconstructing the function of maternal stimulation in offspring development: Insights from the artificial rearing model in rats. Horm. Behav. 2016;77:224–236. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2015.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long B., Seah S.A., Carter T., Subramanian S. Rendering volumetric haptic shapes in mid-air using ultrasound. ACM Trans. Graphs. 2014;33:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Madianou M., Miller D. Polymedia: Towards a new theory of digital media in interpersonal communication. Int. J. Cult. Stud. 2012;16:169–187. [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel B.T., Drouin M. Sexting among married couples: Who is doing it, and are they more satisfied? Cyberpsychol Behav. Soc. Netw. 2015;18:628–634. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2015.0334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna K.Y.A., Green A.S., Gleason M.E.J. Relationship formation on the internet: What's the big attraction? J. Soc. Issues. 2002;58:9–31. [Google Scholar]

- McPherson M., Smith-Lovin L., Brashears M.E. Social isolation in America: Changes in Core discussion networks over two decades. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2006;71:353–375. [Google Scholar]

- Moody E.J. Internet use and its relationship to lonelines. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2001;4:393–401. doi: 10.1089/109493101300210303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morahan-Martin J., Schumacher P. Loneliness and social uses of the Internet. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2003;19:659–671. [Google Scholar]

- Moyer C.A., Rounds J., Hannum J.W. A meta-analysis of massage therapy research. Psychol. Bull. 2004;130:3–18. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadkarni A., Hofmann S.G. Why do people use Facebook? Personal. Individ. Differ. 2012;52:243–249. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace T., Bardzell S., Bardzell J. ACM; Atlanta, Georgia, USA: 2010. The rogue in the lovely black dress: Intimacy in world of warcraft, Proceedings of the 28th international conference on Human factors in computing systems. [Google Scholar]

- Padgett P. Personal safety and sexual safety for women using online personal ads. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy. 2007;4:27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Parks M.R., Roberts L.D. `making Moosic': The development of personal relationships on line and a comparison to their off-line counterparts. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 1998;15:517–537. [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker J.W. Putting stress into words: Health, linguistic, and therapeutic implications. Behav. Res. Ther. 1993;31:539–548. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(93)90105-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker J.W. The effects of traumatic disclosure on physical and mental health: The values of writing and talking about upsetting events. Int. J. Emerg. Ment. Health. 1999;1:9–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prager K.J. The Guilford Press; New York, NY: 1995. The psychology of intimacy. [Google Scholar]

- Pujazon-Zazik M., Park M.J. To tweet, or not to tweet: Gender differences and potential positive and negative health outcomes of adolescents' social internet use. Am. J. Mens Health. 2010;4:77–85. doi: 10.1177/1557988309360819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam R.D. Simon & Schuster; New York, NY: 2000. Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez A., Jr., Zhang S. When online meets offline: The effect of modality switching on relational communication. Commun. Monogr. 2007;74:287–310. [Google Scholar]

- Reeves P.M. Coping in cyberspace: The impact of Internet use on the ability of HIV-positive individuals to deal with their illness. J. Health Commun. 2000;(5 Suppl):47–59. doi: 10.1080/10810730050019555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Register L.M., Henley T.B. The phenomenology of intimacy. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 1992;9:467–481. [Google Scholar]

- Reis H.T., Franks P. The role of intimacy and social support in health outcomes: Two processes or one? Pers. Relat. 1994;1:185–197. [Google Scholar]

- Reis H.T., Shaver P.R. Intimacy as interpersonal process. In: Duck S., editor. Handbook of personal relationships: Theory, relationships, and interventions. Wiley; Chichester, UK: 1988. pp. 367–389. [Google Scholar]

- Rice R.E., Love G. Electronic emotion: Socioemotional content in a computer-mediated communication network. Commun. Res. 1987;14:85–108. [Google Scholar]

- Robles T.F., Kiecolt-Glaser J.K. The physiology of marriage: Pathways to health. Physiol. Behav. 2003;79:409–416. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(03)00160-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robson D., Robson M. Intimacy and computer communication. Br. J. Guid. Couns. 1998;26:33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen L.D., Cheever N.A., Cummings C., Felt J. The impact of emotionality and self-disclosure on online dating versus traditional dating. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2008;24:2124–2157. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff C.D., Keyes C.L.M. The structure of psychological well-being revisited. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1995;69:719–727. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.4.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff C.D., Singer B. Interpersonal flourishing: A positive health agenda for the new millennium. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2000;4:30–44. [Google Scholar]

- Schultze U. Embodiment and presence in virtual worlds: A review. J. Inf. Technol. 2010;25:434–449. [Google Scholar]

- Selfhout M.H.W., Branje S.J.T., Delsing M., ter Bogt T.F.M., Meeus W.H.J. Different types of internet use, depression, and social anxiety: The role of perceived friendship quality. J. Adolesc. 2009;32:819–833. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw L.H., Gant L.M. In defense of the internet: The relationship between Internet communication and depression, loneliness, self-esteem, and perceived social support. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2002;5:157–171. doi: 10.1089/109493102753770552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw B.R., Hawkins R., McTavish F., Pingree S., Gustafson D.H. Effects of insightful disclosure within computer mediated support groups on women with breast cancer. Health Commun. 2006;19:133–142. doi: 10.1207/s15327027hc1902_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim M., Cappella J.N., Han J.Y. How does insightful and emotional disclosure bring potential health benefits? Study based on online support groups for women with breast cancer. J. Commun. 2011;61:432–454. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2011.01555.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperry L. Intimacy: Definition, contexts, and models for understanding its development and diminishment. In: Carlson J., Sperry L., editors. Recovering intimacy in love relationships: A Clinician's Guide. Routledge; New York, NY: 2010. pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Stanton K., Ellickson-Larew S., Watson D. Development and validation of a measure of online deception and intimacy. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2016;88:187–196. [Google Scholar]

- Steinfield C., Ellison N.B., Lampe C. Social capital, self-esteem, and use of online social network sites: A longitudinal analysis. J. App. Dev. Psychol. 2008;29:434–445. [Google Scholar]

- Steinfield C., Ellison N., Lampe C., Vitak J. Online social network sites and the concept of social capital. In: Lee F.L., Leung L., Qiu J.S., Chu D., editors. Frontiers in New Media Research. Routledge; New York: 2012. pp. 115–131. [Google Scholar]

- Subrahmanyam K., Reich S.M., Waechter N., Espinoza G. Online and offline social networks: Use of social networking sites by emerging adults. J. App. Dev. Psychol. 2008;29:420–433. [Google Scholar]

- Swickert R.J., Hittner J.B., Harris J.L., Herring J.A. Relationships among internet use, personality, and social support. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2002;18:437–451. [Google Scholar]

- Tichon J.G., Shapiro M. The process of sharing social support in cyberspace. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2003;6:161–170. doi: 10.1089/109493103321640356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchino B.N., Cacioppo J.T., Kiecolt-Glaser J.K. The relationship between social support and physiological processes: A review with emphasis on underlying mechanisms and implications for health. Psychol. Bull. 1996;119:488–531. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.119.3.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valkenburg P.M., Peter J. Preadolescents' and adolescents' online communication and their closeness to friends. Dev. Psychol. 2007;43:267–277. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valkenburg P.M., Peter J. Online communication among adolescents: An integrated model of its attraction, opportunities, and risks. J. Adolesc. Health. 2011;48:121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valkenburg P.M., Peter J., Schouten A.P. Friend networking sites and their relationship to Adolescents' well-being and social self-esteem. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2006;9:584–590. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2006.9.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Eijnden R.J., Meerkerk G.J., Vermulst A.A., Spijkerman R., Engels R.C. Online communication, compulsive internet use, and psychosocial well-being among adolescents: A longitudinal study. Dev. Psychol. 2008;44:655–665. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.3.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn M.J., Matyastik Baier M.E. Reliability and validity of the relationship assessment scale. Am. J. Fam. Ther. 1999;27:137–147. [Google Scholar]

- Vetere F., Gibbs M.R., Kjeldskov J., Howard S., Mueller F.F., Pedell S., Mecoles K., Bunyan M. ACM; Portland, Oregon, USA: 2005. Mediating intimacy: Designing technologies to support strong-tie relationships, Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human factors in computing systems. [Google Scholar]

- Waring E.M. Measurement of intimacy: Conceptual and methodological issues of studying close relationships. Psychol. Med. 1985;15:9–14. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700020882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitty M.T. Liberating or debilitating? An examination of romantic relationships, sexual relationships and friendships on the net. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2008;24:1837–1850. [Google Scholar]

- Whitty M.T. Online romantic relationships. In: Amichai-Hamburger Y., editor. The Social Net: Understanding our online behavior. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Whitty M.T., Joinson A.N. Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group; New York, NY, US: 2009. Truth, lies and trust on the Internet. [Google Scholar]

- Wilding R. ‛Virtual’ intimacies? Families communicating across transnational contexts. Glob. Netw. 2006;6:125–142. [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm K., Parker G. The development of a measure of intimate bonds. Psychol. Med. 1988;18:225–234. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700002051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson D.S., Knox P.L., Chatman J.E., Johnson T.L., Barbour N., Myles Y., Reel A. The clinical effectiveness of healing touch. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2002;8:33–47. doi: 10.1089/107555302753507168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong Z.-J. The effects of collective MMORPG (Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Games) play on gamers' online and offline social capital. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011;27:2352–2363. [Google Scholar]