Abstract

Clinical supervision is integral to continuing professional development of health professionals. With advances in technology, clinical supervision too can be undertaken using mediums such as videoconference, email and teleconference. This mode of clinical supervision is termed as telesupervision. While telesupervision could be useful in any context, its value is amplified for health professionals working in rural and remote areas where access to supervisors within the local work environment is often diminished. While telesupervision offers innovative means to undertake clinical supervision, there remain gaps in the literature in terms of its parameters of use in clinical practice. This article outlines ten evidence-informed, practical tips stemming from a review of the literature that will enable health care stakeholders to use technology effectively and efficiently while undertaking clinical supervision. By highlighting the “how to” aspect, telesupervision can be delivered in the right way, to the right health professional, at the right time.

Keywords: Clinical supervision, Telesupervision, Continuing professional development, Workforce development/issues

Introduction

Continuing professional development requires robust support mechanisms to maximise opportunities for achieving best practice in clinical settings (Parkinson et al., 2010). Clinical or professional supervision is one mechanism to do this (Moran et al., 2014). Clinical supervision has been shown to benefit the patient, the health professional and the organisation (Bambling et al., 2006, Farnan et al., 2012, Fitzpatrick et al., 2012). While the benefits of supervision is widely accepted, the terminology about and the definition of clinical supervision is marred by confusion (Dawson et al., 2012, Martin et al., 2014, Ducat and Kumar, 2015). In this article, clinical supervision is defined as a formal process of professional support and learning which enables individual practitioners to develop knowledge and competence (Edwards et al., 2005, Simpson and Sparkes, 2008).

The need for clinical supervision in non-metropolitan settings where health professionals face a number of challenges in accessing professional support is well-documented (Ducat and Kumar, 2015, Edwards et al., 2005, Simpson and Sparkes, 2008, Martin and Kumar, 2013). While supervision has historically been provided face-to-face, the use of distance supervision using technology is on the rise (Brandoff and Lombardi, 2012). Distance supervision or telesupervision refers to clinical supervision conducted by using technology such as telephone, email or videoconferencing (Brandoff and Lombardi, 2012). Videoconferencing is the use of video in real time to connect and this includes use of platforms such as Skype. This usually occurs when the supervisor and supervisee are not co-located. With the rise of social media, tools such as blog, micro-blog, wiki, video chat, virtual world, podcast and social networks can also play a role in telesupervision (Kind et al., 2014). Moving from traditional face-to-face supervision to telesupervision calls for clear guidelines and recommendations for using technology to undertake clinical supervision. It is important to recognise that telesupervision is not the same as tele/distance education (which also uses technology). While tele/distance education has a particular focus on teaching and learning and as such been researched extensively (Chi and Demiris, 2015, Bain et al., 2015), the use of technology to support health professionals is the focus of telesupervision.

To date, there is only limited information in the literature on the quality and effectiveness of telesupervision (Ducat and Kumar, 2015, Manosevitz, 2006, Wood et al., 2005, Robson and Whelan, 2007). Manosevitz (2006) noted that supervision using technology, such as telephone, while frequently used is rarely evaluated. He argued that there was a dearth of information on how supervision using technology is best undertaken and highlighted the need to address persistent knowledge gaps. More recently, Ducat and Kumar (2015) completed a systematic review of professional supervision experiences of allied health practitioners working in non-metropolitan health care settings. They echoed Manosevitz's (2006) observations and noted that the concept of, and the impact from, telesupervision requires more attention. Telesupervision has the potential to achieve the same benefits as face-to-face supervision and offers a very promising approach to supervision, particularly for geographically isolated practitioners (Miller et al., 2010, McColgan and Rice, 2012, Rousmaniere et al., 2014). This article, based on a review of the literature, outlines ten evidence-informed, practical tips that will enable health care stakeholders to use technology effectively and efficiently while undertaking clinical supervision. This can assist health care stakeholders to become better informed and confident while engaging in telesupervision.

1. Set clear expectations and goals for telesupervision

Clinical supervision has been shown to have consistent positive outcomes when the purpose and goals of supervision are explicitly stated and roles of the supervisor and supervisee are clarified at the outset (Martin et al., 2014, Kenny and Allenby, 2013). This is true for all types of clinical supervision, regardless of the mode or medium used and therefore is a critical first step. Supervision goals are set at the start of the supervision partnership. During this stage, a supervision agreement is developed between the supervisor and the supervisee (Martin et al., 2014). This may take one or more sessions and is dependent on various factors such as the experience level of the supervisor and supervisee, supervision needs of the supervisee, organisational policies around professional support activities etc.

Where possible, it is recommended that the initial sessions where goals and expectations are discussed and supervision contract developed, be undertaken face-to-face before transitioning into telesupervision. If initial face-to-face supervision sessions are not feasible, telesupervision using videoconference is recommended (as opposed to using a telephone). This is because the ability to read non-verbal cues is preserved while using videoconference. Furthermore, cohesion between participants has been shown to improve when non-verbal cues are able to be seen (Hambley et al., 2007).

2. There is no one size fits all with the medium and mode of telesupervision

Wood et al. (2005) recommend that a range of telecommunication options be incorporated into the supervisory process to maximise the benefits of telesupervision. Different health professionals engage with telesupervision differently, have different learning styles and this flexibility recognises there is no one size fits all. It is essential that the medium of technology used in telesupervision is carefully considered. This will largely be dictated by the clinical supervision needs of the supervisee. For example, a supervisee with a learning need related to a hands-on skill or clinical task, such as bandaging a limb, would find videoconference more beneficial than teleconference. To a lesser extent factors such as equipment, network capacity and technical support available may also influence the choice of medium used. Optimal and effective use of technology has been shown to lead to positive supervision outcomes (Ducat et al., 2015). Hence it is imperative that the supervisee and supervisor are proficient and competent in the technologies being used (Rousmaniere et al., 2014). Some supervisees or supervisors may benefit from targeted initial training in the use of equipment related to the medium chosen (e.g., videoconference). Such training should aim to educate participants about the mechanics and the use of the equipment and provide an opportunity for hands-on practice operating the equipment as means of familiarisation (Wood et al., 2005, Cameron et al., 2015).

Furthermore, it is recommended that face-to-face meetings should complement telesupervision in an ad hoc or opportunistic manner. This recommendation is generally supported in the telesupervision literature (Manosevitz, 2006, Wood et al., 2005, Martin et al., 2015, Reese et al., 2009, Sorlie et al., 1999). Some studies found that augmenting telesupervision with face-to-face supervision resulted in the supervisee rating their supervision as more effective (Martin et al., 2015, Reese et al., 2009). Furthermore, Martin et al. (2015) found that the reverse was also true in that some supervisees that had no prior face-to-face contact with their supervisors reported concerns about their telesupervision partnership.

3. Embed telesupervision into a sound framework based on educational principles

Professional support activities achieve best outcomes when they are underpinned by established frameworks and educational principles (Schichtel, 2009, Nancarrow et al., 2014). Doing so will ensure that clinical supervision theory and practice are linked. As health professionals are confused about the pragmatics of the clinical supervision process (Dawson et al., 2012, Martin et al., 2014), it is essential for the supervisee and supervisor to clarify what clinical supervision means and how it will be undertaken. The Proctor's model of clinical supervision is informed by rigorous research and commonly used in practice (Martin et al., 2014, Winstanley and White, 2003). As per this model, clinical supervision is divided into formative, normative and restorative domains (Winstanley and White, 2003). These domains can be used to structure supervision sessions. More recently, Nancarrow et al. (2014) proposed a supervision and support framework, developed by thematic analysis of existing supervision frameworks, called ‘connecting practice’. This is a practitioner-centred framework that recognises the tacit and explicit knowledge that the supervisor and supervisee bring to the supervision partnership (Nancarrow et al., 2014). Embedding telesupervision onto a framework, which is paired with educational principles, is likely to maximise supervision outcomes (Sorlie et al., 1999).

4. Focus on the supervisory relationship

Supervisor-supervisee fit, which results in a positive supervisory relationship, has been shown to be a critical factor for effective and high quality supervision (Martin et al., 2014, Martin et al., 2015, Ducat et al., 2015, Wetchler et al., 2007), especially in telesupervision. A positive supervisory relationship is achieved by mutual trust and respect for each other (Sorlie et al., 1999). Some reports of telesupervision in the literature note that participants felt telesupervision was on par with face-to-face supervision when the supervisor and supervisee had a positive supervisory relationship and had met face-to-face previous to entering the telesupervision arrangement (Manosevitz, 2006, Cameron et al., 2015, Sorlie et al., 1999, Mason and Hayes, 2007). Therefore it is recommended that the supervisee is matched with the right supervisor for an optimal supervisor-supervisee fit and where possible is provided with a choice of supervisor (Martin et al., 2015, Martin et al., 2016).

5. Formulate a plan to manage technical problems

Technology is not without its limitations with poor reliability and connectivity being the commonly reported technological problems. It is therefore essential to anticipate and manage technical problems proactively (Chou et al., 2012) in telesupervision. Benefits of supervision undertaken via technology is maximised when there is an action plan for managing technological glitches. Chou et al. (2012) argue that a plan outlining anticipatory solutions to common technical issues need to be in place before a telesupervision session. Proposed strategies include having a back-up plan for contacting other participants involved in the teleconference (e.g., via email or another phone number), and identifying a technical support point person to help with resolving issues (Chou et al., 2012). It is recommended that a plan to manage technical problems be developed and included in the clinical supervision contract. This plan is likely to vary depending on the medium of technology used, with dedicated teleconferencing systems more likely to require technical support than mobile technologies. It is recommended that aspects such as other means of contact, back-up phone numbers and training in the use of equipment be considered.

6. Pay attention to communication

Developments in technology provide new opportunities for understanding the role of communication in the process of building relationships (Cameron et al., 2015, Sorlie et al., 1999). However, the absence of physical cues in virtual meeting environments, such as those created while engaging in telesupervision, may lead to unwanted hazards such as distraction and the temptation to multi-task (Manosevitz, 2006, Wasson, 2004). It is useful for the supervisor and supervisee to discuss upfront the use of silence, minimising distractions and avoiding unrelated multi-tasking during supervision sessions. The supervisee and supervisor need to consider the use of silence during sessions and define a period that will be allowed and accepted by both parties. When reflection occurs within supervision (Martin et al., 2014), it is expected to be accompanied by some silence. While using the telephone for supervision, the supervisor and supervisee will need to be comfortable with silence when it occurs. Having an explicit discussion about this and defining a time period after which the supervisee or supervisor may interject is crucial in this process.

The supervisee and supervisor need to be mindful of avoiding multi-tasking during the supervision session. Whilst some multi-tasking activities such as conducting a concurrent literature search on the topic discussed may be helpful, some other tasks such as having a cross-conversation with a third party (e.g. via email or text message which is not obvious to the other supervision partner) may act as a deterrent to the supervision session (Chou et al., 2012). A dedicated space to undertake supervision situated away from the regular work space may help eliminate some distractions (Martin et al., 2014). Another important consideration is the use of a good speaking etiquette. This includes appropriate turn-taking, being clear while speaking, using the mute button while listening, paraphrasing and use of questions (Martin et al., 2014). Therefore, it is recommended that more attention is paid to communication while using media such as the telephone or web conferencing where there is no access to physical cues.

7. Rethink continuity

Telesupervision is likely to be more successful when the involved parties prioritise continuity over co-location. This means that the disadvantage created by the increased distance between the supervisor and the supervisee in a telesupervision partnership is overcome by increased supervisor availability between supervision sessions. Wearne et al. (2014) explored one approach of remote supervision of registrars in isolated rural practice through thematic analysis of data from eleven in-depth interviews. They concluded that responsibility and continuity may be as important as supervisor proximity for experienced registrars. Similarly, Martin et al.'s (2015) research of occupational therapy supervisees identified that the availability of supervisor between clinical supervision sessions enhanced the perceived effectiveness of supervision. The issue of continued, or increased, availability should be discussed at the outset of the telesupervision partnership. Ad hoc contact between the supervision sessions may take the form of an email and/or limited to critical times. This is best discussed upfront and revisited during regular telesupervision reviews.

8. Protect online security, safety, confidentiality

It is essential that the supervisor and supervisee undertaking telesupervision adhere to responsible and ethical use of technology (Quinn and Phillips, 2010). Roby et al. (Roby and Panos, 2004) outline the various ethical and legal issues surrounding telesupervision such as liability, protecting confidentiality and adhering to professional practice standards. Users should be aware of their legal and professional practice guidelines and liability related to the use of technology in supervision (Wood et al., 2005, Roby and Panos, 2004, Rousmaniere and Kuhn, 2016). While face-to-face supervision must also uphold confidentiality, telesupervision can be particularly risky as it involves transferring confidential information using technology. For example, an email with client information can be accidentally sent to a third party or information about a client could be faxed to an incorrect number thereby breaching confidentiality. Furthermore, supervisors need to ensure that supervision is timely, adequate and within the supervisor's scope of practice (Quinn and Phillips, 2010, Roby and Panos, 2004). Rousmaniere and Kuhn (2016) outline various practical strategies to ensure internet security for clinical supervisors such as setting strong passwords, performing regular computer backups and tips for avoiding phishing attacks.

9. Factor in additional time

It is important for supervisees and supervisors to set aside and protect clinical supervision time. This becomes particularly crucial in telesupervision, as additional time may be needed for trouble shooting issues with technology and to prepare for telesupervision sessions (Wood et al., 2005, Rousmaniere et al., 2014, Cameron et al., 2015). Setting and forwarding the agenda prior to the session will ensure that maximum benefits are reaped from the telesupervision session (Mason and Hayes, 2007). Therefore, it is recommended that supervisees and supervisors set aside and protect additional supervision time through all the phases of telesupervision.

10. Review telesupervision arrangement regularly

Regular monitoring and evaluation of telesupervision processes and outcomes are critical to ensuring agreed goals and objectives are being met (Brandoff and Lombardi, 2012). Martin et al. (2014) summarise a range of formal and informal methods to evaluate clinical supervision on a regular basis. They recommend that factors such as the style of supervision, whether the needs of the supervisee are being met, the effectiveness of feedback provided, the nature of the supervisory relationship and the support provided be evaluated. The evaluation and review should be followed by changes to the clinical supervision contract or arrangement if required (Martin et al., 2014). With regards to telesupervision, additional consideration should be provided to the medium used to determine if the supervisee's learning goals are being met using this medium. A decision should then be made about continuing with the same medium, changing the medium or augmenting the existing medium with other options.

Conclusions

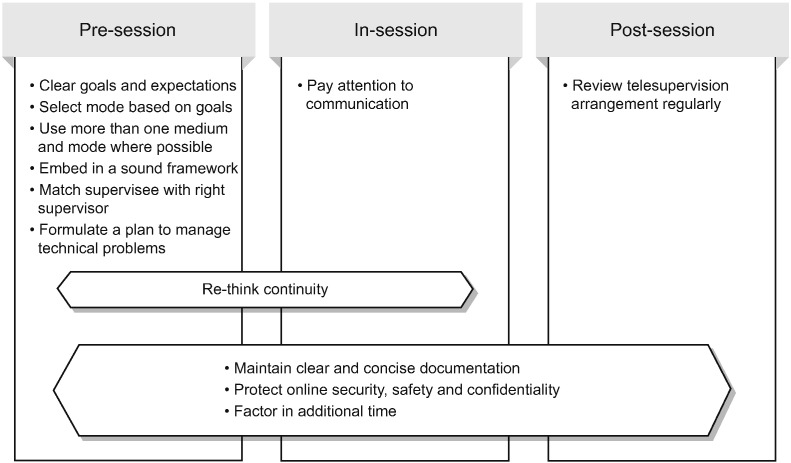

Telesupervision offers an opportunity to overcome the tyrannies of distance, access and time. However, improved access to technology and connectivity does not necessarily equate to quality telesupervision. Based on contemporary research evidence and real-world experience from the coal face, this article provides ten practical tips (also shown in Fig. 1) that will enable health care stakeholders to use technology effectively and efficiently through all the stages of telesupervision namely pre-session, in-session and post-session.

Fig. 1.

Tips aligned with telesupervision phases.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

Nil.

Authors' contributions

PM developed the idea for the paper and completed the literature search. PM, SK and LL contributed to the synthesis of information from the literature search. All authors contributed to writing the paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mr. Daniel McDonald, librarian, Darling Downs Hospital and Health Service for assisting with the literature search. The first author acknowledges the Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship that funds her PhD.

Biographies

Priya Martin is an advanced clinical educator at the Cunningham Centre, Darling Downs Hospital and Health Service, Queensland, Australia. She is also a PhD candidate with the School of Health Sciences, University of South Australia.

Saravana Kumar is a senior lecturer and researcher at the School of Health Sciences and the Sansom Institute for Health Research, University of South Australia.

Lucylynn Lizarondo is a research fellow for Implementation Science at the Joanna Briggs Institute, University of Adelaide.

Contributor Information

Priya Martin, Email: Priya.Martin@health.qld.gov.au.

Saravana Kumar, Email: Saravana.Kumar@unisa.edu.au.

Lucylynn Lizarondo, Email: Lucylynn.Lizarondo@adelaide.edu.au.

References

- Bain T.M., Jones M.L., O'Brian C. Feasibility of smartphone-delivered diabetes self-management education and training in an underserved urban population of adults. J. Telemed. Telecare. 2015;21(1):58–60. doi: 10.1177/1357633X14545426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bambling M., King R., Raue P. Clinical supervision: its influence on client-rated working alliance and client symptom reduction in the brief treatment of major depression. Psychother. Res. 2006;16(3):317–331. [Google Scholar]

- Brandoff R., Lombardi R. Miles apart: two art therapists' experience of distance supervision. Art Ther. 2012;29(2):93–96. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron M., Ray R., Sabesan S. Remote supervision of medical training via videoconference in northern Australia: a qualitative study of perspectives of supervisors and trainees. BMJ Open. 2015;5 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi N., Demiris G. A systematic review of telehealth tools and interventions to support family caregivers. J. Telemed. Telecare. 2015;21(1):37–44. doi: 10.1177/1357633X14562734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou C.L., Promes S.B., Souza K.H. Twelve tips for facilitating successful teleconferences. Med. Teach. 2012;34(6):445–449. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.668241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson M., Phillips B., Leggat S.G. Effective clinical supervision for regional allied health professionals: the supervisee's perspective. Aust. Health Rev. 2012;36:92–97. doi: 10.1071/AH11006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducat W.H., Kumar S. A systematic review of professional supervision experiences and effects for allied health practitioners working in non-metropolitan health care settings. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2015;8:397–407. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S84557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducat W., Martin P., Kumar S. Oceans apart yet connected: findings from a qualitative study on professional supervision in rural and remote allied health services. Aust. J. Rural Health. 2015;24(1):29–35. doi: 10.1111/ajr.12192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards D., Cooper L., Burnard P. Factors influencing the effectiveness of clinical supervision. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2005;12:405–414. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2005.00851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farnan J.M., Petty L.A., Georgitis E. A systematic review: the effect of clinical supervision on patient and residency education outcomes. Acad. Med. 2012;87(4):1–15. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31824822cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick S., Smith M., Wilding C. Quality allied health clinical supervision policy in Australia: a literature review. Aust. Health Rev. 2012 doi: 10.1071/AH11053. 10.1071/AH11053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hambley L.A., O'Neill T.A., Kilne T.J.B. Virtual team leadership: the effects of leadership style and communication medium on team interaction styles and outcomes. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2007;103:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny A., Allenby A. Implementing clinical supervision for Australian nurses. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2013;13(3):165–169. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2012.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kind T., Patel P.D., Lie D.L. Twelve tips for using social media as a medical educator. Med. Teach. 2014;36(4):284–290. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2013.852167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manosevitz M. Supervision by telephone. An innovation in psychoanalytic training – a roundtable discussion. Psychoanal. Psychol. 2006;23(3):579–582. [Google Scholar]

- Martin P., Kumar S. Making the most of what you have: challenges and opportunities from funding restrictions on health practitioners' professional development. Inter. J. Allied Health Sci. Pract. 2013;11(4) [Google Scholar]

- Martin P., Copley J., Tyack Z. Twelve tips for effective clinical supervision based on a narrative literature review and expert opinion. Med. Teach. 2014;36:201–207. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2013.852166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin P., Kumar S., Lizarondo L. Enablers of and barriers to high quality supervision among occupational therapists across Queensland in Australia: findings from a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2015;15(1) doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-1085-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin P., Kumar S., Lizarondo L., Tyack Z. Factors influencing the quality of clinical supervision of occupational therapists in one Australian State. Aust. Occup. Ther. J. 2016 doi: 10.1111/1440-1630.12314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason R., Hayes H. Telephone peer supervision and surviving as an isolated consultant. Psychiatr. Bull. 2007;31:215–217. [Google Scholar]

- McColgan K., Rice C. An online training resource for clinical supervision. Nurs. Stand. 2012;26(24):35–39. doi: 10.7748/cnp.v1.i9.pg45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller T.W., Miller J.M., Burton D. Telehealth: A model for clinical supervision in allied health. Inter. J. Allied Health Sci. Pract. 2010;1(2) [Google Scholar]

- Moran A.M., Coyle J., Pope R. Supervision, support and mentoring interventions for health practitioners in rural and remote contexts: an integrative review and thematic analysis of the literature to identify mechanisms for successful outcomes. Hum. Resour. Health. 2014;12:10. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-12-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nancarrow S.A., Wade R., Moran A. Connecting practice: a practitioner centred model of supervision. Clin. Gov. 2014;19(3):235–252. [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson S., Lowe C., Keys K. Professional development enhances the occupational therapy work environment. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 2010;73(10):470–476. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn A., Phillips A. Online synchronous technologies for employee- and client-related activities in rural communities. J. Technol. Hum. Serv. 2010;28:240–251. [Google Scholar]

- Reese R.J., Aldarondo F., Anderson C.R. Telehealth in clinical supervision: a comparison of supervision formats. J. Telemed. Telecare. 2009;15(7):356–361. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2009.090401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robson M., Whelan L. Virtue out of necessity? Reflections on a telephone supervision relationship. Couns. Psychother. Res. 2007;6(3):202–208. [Google Scholar]

- Roby J.L., Panos P.T. Recent developments in laws and ethics concerning videosupervision of international field students. J. Technol. Hum. Serv. 2004;22(4):73–91. [Google Scholar]

- Rousmaniere T., Kuhn N. Internet security for clinical supervisors. In: Rousmaniere, Renfro-Michel, editors. ACA Using Technology to Enhance Clinical Supervision. 2016. Wiley.com. [Google Scholar]

- Rousmaniere T., Abbass A., Frederickson J. New developments in technology-assisted supervision and training: a practical overview. J. Clin. Psychol. 2014;70(11):1082–1093. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schichtel M. A conceptual description of potential scenarios of e-mentoring in GP specialist training. Educ. Prim. Care. 2009;20(5):360–364. doi: 10.1080/14739879.2009.11493818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson S., Sparkes C. Supervision (2) – models and barriers. Speech Lang. Ther. Pract. 2008;1000:18. [Google Scholar]

- Sorlie T., Gammon D., Bergvik S. Psychotherapy supervision face-to-face and by videoconferencing: a comparative study. Br. J. Psychother. 1999;15(4):452–462. [Google Scholar]

- Wasson C. Multitasking during virtual meetings. Hum. Resour. Plan. 2004;27:47–60. [Google Scholar]

- Wearne S.M., Teunissen P.W., Dornan T. Physical isolation with virtual support: registrars' learning via remote supervision. Med. Teach. 2014;37(7):670–676. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2014.947941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetchler J.L., Trepper T.S., Mccollum E.E. Videotape supervision via long-distance telephone. Am. J. Fam. Ther. 2007;21(3):242–247. [Google Scholar]

- Winstanley J., White E. Clinical supervision: models, measures and best practice. Nurs. Res. 2003;10(4):7–38. [Google Scholar]

- Wood J.A.V., Miller T.W., Hargrove D.S. Clinical supervision in rural settings: a telehealth model. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2005;36(2):173–179. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.