Abstract

Targeting protein for Xenopus kinesin-like protein 2 (TPX2) activates Aurora kinase A during mitosis and targets its activity to the mitotic spindle, serving an important role in mitosis. It has been associated with different types of cancer and is considered to promote tumor growth. The aim of the present study was to explore the role of TPX2 in diagnosing prostate cancer (PCa). It was identified that TPX2 expression in PCa tissues was increased compared with benign prostate tissues. Microarray analysis demonstrated that TPX2 was positively associated with the Gleason score, tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) stage, clinicopathological stage, metastasis, overall survival and biochemical relapse-free survival. In vitro studies revealed that the high expression of TPX2 in PCa cells improved proliferative, invasive and migratory abilities, and repressed apoptosis of the PCa cells, without affecting tolerance to docetaxel. The results suggested that TPX2 serves as a tumorigenesis-promoting gene in PCa, and a potential therapeutic target for patients with PCa.

Keywords: prostate cancer, targeting protein for Xenopus kinesin-like protein 2, prostate cancer diagnosis, prostate cancer prognosis

Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in men. In 2016, there were an estimated 1,685,210 incident cases of PCa in the USA (1). The annual change in prostate cancer incidence was 4.7% between 2005–2011 in China (2). PCa is clinically divided into different risk groups, based on the levels of serum prostate specific antigen (PSA), clinical tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) (3) and Gleason score (3). PSA has been used as a biomarker in the diagnosis of PCa for almost 30 years (4). However, the false-positive or false-negative rates of PSA-based diagnosis restrict its use as a sole criterion (4). It was demonstrated that 49.6% patients with PCa were misdiagnosed using PSA only (5). Therefore, there is an urgent requirement to identify a highly specific and accurate biomarker for PCa diagnosis and prognosis.

Targeting protein for Xenopus kinesin-like protein 2 (TPX2) belongs to the Microtubule-associated protein family. All members of this family contain a conserved TPX2 motif that interacts with microtubules (6). The interaction regulates microtubule dynamics or certain microtubule functions, including the maintenance of cell morphology and proliferation (6). Overexpression of TPX2 induces the amplification of the centrosome and leads to DNA polyploidy (7). Its expression is tightly regulated by the cell cycle, and this protein is detected during the G1-S stage and disappears following the completion of mitosis (7). During the early stage of mitosis, TPX2 is released in a Ran GTP-dependent manner and serves an important role in mitotic spindle formation and proper segregation of chromosomes during cell division (7). TPX2 may promote the centromere-associated microtubule formation and increase the rate of centrosome-associated microtubule assembly (7).

Previous evidence indicated that increased TPX2 expression was observed in different cancer types: It has been demonstrated that high TPX2 expression was associated with tumor progression and poor survival rate of gastric cancer (8,9). Previous studies have also revealed the upregulation of TPX2 expression in breast and pancreatic cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, colon cancer and other types of cancer (10–13). Furthermore, TPX2 serves as an oncogenic protein and promotes the expression of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) through the activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Protein kinase B (Akt) signaling pathway in colon cancer (14). Depletion of TPX2 with TPX2 small interfering RNA weakens the ability of invasion and proliferation in SMMC-7721 and HepG2 cells (14). However, the role of TPX2 in PCa remains unclear. According to the results of one previous study, TPX2 functions as a novel co-regulator on the MYC pathway (15). Inhibiting the Aurora kinase A (AURKA)/TPX2 axis may be a novel synthetic lethal therapeutic approach for MYC-driven types of cancer (15). Furthermore, TPX2 overexpression increases the mortality in patients with breast cancer (16). Therefore, the present study investigated whether the overexpression of TPX2 in PCa cells contributed to tumor progression and was able to predict poor prognosis in patients with PCa.

Materials and methods

Patients and tissue samples

These procedures were approved by the Research Ethics Committee of The Third Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University (Guangzhou, China). A tissue microarray (TMA) containing 73 primary PCa tissues and 7 adjacent noncancerous prostate tissues was purchased from Alenabio (cat no. PR803c; Xi'an, China). None of the patients from which the samples were taken had undergone chemotherapy or radiotherapy prior to surgery. The Taylor dataset (Gene Expression Omnibus accession no., GSE21032), an online PCa dataset that included 150 primary PCa tissues and 29 adjacent noncancerous prostate tissues, was downloaded from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi. The primary criterion was biochemically-measured recurrence-free survival time of serum PSA levels. An additional analysis criterion was the overall survival time. All patients who succumbed to diseases other than PCa or unexpected events were excluded. The clinical features of the patients used in the TMA (age range, 20–87 years old) and Taylor datasets (age range, 37–83 years old) are summarized in Table I.

Table I.

Clinical features of patients.

| Dataset | ||

|---|---|---|

| Clinical features | TMAa | Taylor dataset |

| Benign tissue, cases | 7 | 29 |

| Prostate cancer, cases | 73 | 150 |

| Age, years | ||

| Mean | 68.29±10.20 | 58.33±7.10 |

| <66 | 23 | 124 |

| ≥66 | 44 | 26 |

| Serum PSA | ||

| <4 | – | 21 |

| 4–10 | – | 81 |

| ≥10 | – | 42 |

| Gleason score | ||

| ≤6 | – | 41 |

| 7 | – | 76 |

| ≥8 | – | 22 |

| Pathological stage | ||

| I–II | 43 | 86 |

| III–IV | 27 | 55 |

| TNM stage | ||

| ≤T2A | 45 | 135 |

| ≥T2B | 27 | 10 |

Immunohistochemical analysis. TMA, tissue microarray; PSA, prostate serum antigen; TNM, tumor-node-metastasis.

Western blotting

Proteins of LNCap, PC3 and DU145 cells were extracted by RIPA lysis buffer (cat no. P0013B; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) for 30 min at 4°C, using the protease inhibitor phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (100 mM; cat no. ST506; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) and the supernatant liquid was centrifuged at 13780 × g. Protein quantification was performed using BCA (cat no. 23227; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA), and 15 µg protein/lane was separated using 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Subsequent to blocking with 10% skim milk (Kang Long Group, Inc., Inwood, NY, USA) for 1 h at room temperature, the membrane was incubated with the TPX2 polyclonal rabbit antibody (dilution, 1:100; cat no. HPA005487; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) and β-actin antibody (dilution, 1:200; cat no. BM0627; Boster Biological Technology, Pleasanton, CA, USA) at 4°C overnight. Subsequent to washing three times with Tris-buffered saline with 0.25% Tween-20, the membrane was incubated with a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody (goat anti-rabbit IgG; dilution, 1:400; cat no. BA1060; Boster Biological Technology) for a further 2 h at room temperature. Finally, the immunoreactive protein bands were detected by a Chemiluminescence imaging analysis system (5200; Tanon Science and Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). The relative density of protein expression was quantified using Image J software 1.46 (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Immunohistochemistry analysis

Immunohistochemistry staining of the tissue microarray slice was conducted with the DAKO EnVision system (Dako Diagnostics, Zug, Switzerland) on Dako automated immunostaining instruments, according to the protocol of our previous studies (17) The primary antibodies against TPX2 (Anti-TPX2 antibody, rabbit polyclonal antibody; cat no. HPA005487; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) were used at a dilution of 1:200. HRP-labeled antibodies and alkaline-phosphatase-labeled antibodies [dilution, 1:200; UltraSensitive SP (Mouse/Rabbit) IHC kit] were employed to detect the specifically-bound primary antibodies. Immunostaining was scored by 2 independent experienced pathologists (The Third Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou, China) who were blinded to the clinicopathological data and clinical outcomes of the patients. The scores of the 2 pathologists were compared, and any discrepant scores were resolved through re-examining the staining by the pathologists to achieve a consensus score. The number of stained cells in 10 representative microscopic fields was counted and the percentage of positive cells was calculated using a light microscope (Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Due to the homogeneity of the staining of the target proteins, tumor specimens were scored in a semi-quantitative manner. The percentage of immunoreactive cells was separated into five groups as follows: 0, 0%; 1, 1–10%; 2, 11–50%; 3, 51–80%; and 4, >80%. The staining intensity was visually scored and stratified as follows: 0, negative; 1, weak; 2, moderate; and 3, strong. Final immunoreactivity scores were obtained for each case by multiplying the percentage and the intensity score.

Cell culture and stable cell line generation

The three human PCa DU145, PC3 (CVCL_0035) and LNCaP cell lines used in the present study were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA) and were maintained in the high-glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Hyclone; GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Logan, UT, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The cells were cultured at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator. The TPX2 coding sequence (Genebank: NM_012112.4) was synthesized and cloned into lentivirus-vector by Shanghai Generay Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China), and the plasmid was verified by sequencing. The lentivirus of TPX2-overexpresion and blank vector were produced by Guangzhou HYY Medical Science Co., Ltd. (Guangzhou, China). Subsequently, the LNCaP, DU145 and PC3 cell lines were transfected by the lentivirus of TPX2-overexpresion and blank vector, as the negative control, and finally the stable cell line was produced through puromycin treatment.

Cell viability assay

A Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay (cat. no., C0038; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) was used to evaluate the proliferation of PCa cells. A total of ~2×103 LnCap and PC3 cells/well were seeded into 96-well plates and cultured for 24, 48, and 72 h at 37°C. Cells were then incubated with 10 µl CCK-8 for 2 h at 37°C. The absorbance at a wavelength of 450 nm was measured with a spectrophotometer (Multiskan™ MK3, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) of three independent experiments.

Apoptosis

Apoptosis was analyzed using an Annexin V- allophycocyanin (APC)/7-aminoactinomyocin (7-AAD) Apoptosis Detection kit (BD Pharmingen; BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). The cultured cells were collected and suspended in 1× Binding Buffer (from the apoptosis detection kit) followed by incubation with Annexin V-APC/7AAD for 15 min at room temperature (Annexin V-APC/7AAD kit, cat no. 4224750). Apoptotic analyses were conducted on a BD FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences), and a minimum of 1×106 cell counts were used for each experimental sample. Docetaxel (10 nmol; Shanghai Yu Yan Biotech Co, Ltd, Shanghai, China) was added to the PC3 cells for 48 h at 37°C and the experiments were repeated. Only PC3 cells were used due to patients with androgen-dependent prostate cancer primarily receiving emasculation therapy, with patients with non-androgen-dependent prostate cancer being treated with chemotherapy. LNCap is an androgen-dependent cell and PC3 is a non-androgen-dependent cell (18); therefore, only PC3 cells were treated with chemotherapy.

Scratch wound healing assay

The scratch wound healing assay was performed to evaluate the migratory ability of the PCa cells. The transfections with the TPX2 or negative control vectors were performed when the cells (LnCap and PC3) reached 80–90% confluence using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (cat no. 11668019; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. After 24 h transfection, a scratch was made with a 10 µl pipette tip. The cells were then returned to the incubator until the indicated times (24, 48 and 72 h) at 37°C. Representative images were captured, and the distance that the cells that had migrated from the wound edge were counted at each time point use ImageJ Pro-Plus 6.0 (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). Data are presented as mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

Transwell invasion assay

The CytoSelect Cell Migration and Invasion kit (Cell Biolabs, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) was used according to the manufacturer's protocol. After 24 h transfection, PCa cells were re-suspended in a serum-free RPMI-1640 medium (cat no. sh30809.01B; HyClone; GE Healthcare Life Sciences) to a density of 25×104/ml. The suspended cells (200 µl) were seeded in the upper chambers, and the lower chamber contained 10% fetal bovine serum as a chemoattractant. Following incubation at 37°C for 48 h, the cells that had migrated through the membrane were stained by 0.1% crystal violet (cat no. BS234b; Biosharp, Hefei, China) at room temperature for 15 min and quantified by counting 9 independent symmetrical visual fields under a light microscope (Nikon Corporation). Data are presented as mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

Statistical analysis

The software of SPSS 13.0 for Windows (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis. Continuous variables are presented as mean ± SD. The Kaplan-Meier method was used for the survival analysis, and a log-rank test was used to analyze the difference between survival times. The Student's t-test was used for data analysis. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Overexpression of TPX2 is associated with the clinicopathological characteristics of PCa and tumor recurrence time in patients with PCa

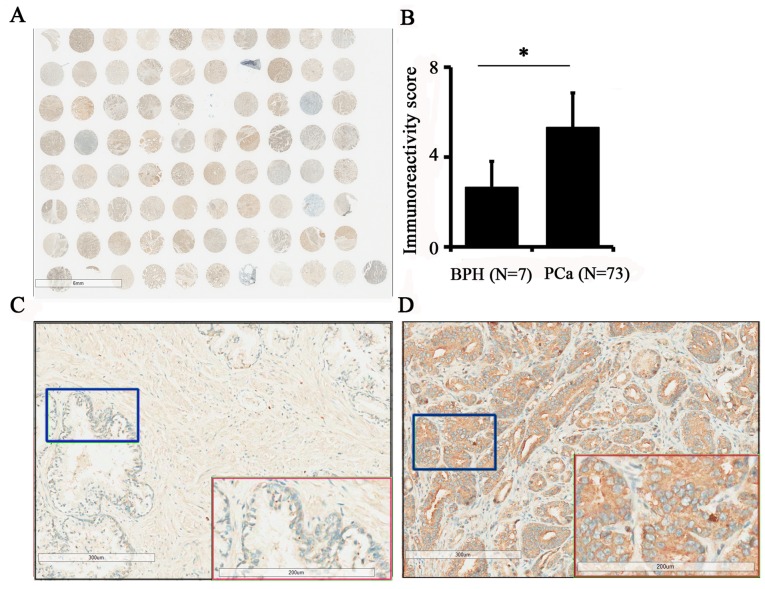

To assess TPX2 protein expression in PCa, a prostate tissue chip containing 7 benign prostate tissues and 73 prostate cancer tissues was evaluated by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 1A). The results demonstrated that the expression of TPX2 in PCa was increased compared with benign tissues (5.12±2.91 vs. 2.43±1.72; P=0.019; Fig. 1B). In addition, the expression of TPX2 protein was positively associated with pathological stage (3) and TNM stage (3) (Table II). Additionally, TPX2 was primarily located in the nucleus and cytoplasm, indicating that the expression of TPX2 was positively associated with the progression of PCa. Images of TPX2 staining in non-cancer tissues and PCa are presented in Fig. 1C and D, respectively.

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemical staining for TPX2 protein expression in PCa and adjacent benign tissues. (A) The whole scanned image of the tissue array (B) Statistical analyses indicated an increased immunoreactivity score in cancer tissues compared with benign tissues. (C) Enlarged image of BPH tissue indicated that TPX2 was only weakly expressed in benign tissues. Red box demonstrates the blue box at a magnification. (D) Enlarged image of PCa tissue demonstrated that TPX2 was highly abundant in the nucleus and cytoplasm of tumor cells. Red box demonstrates the blue box at a magnification. TPX2, Targeting protein for Xenopus kinesin-like protein 2; PCa, prostate cancer; BPH, benign prostatic hypertrophy. *P<0.05.

Table II.

Association of TPX2 expression with clinicopathological characteristics of prostate cancer.

| Dataset | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TMA dataseta | Taylor dataset | |||||

| Clinical features | Case | Mean ± SD | P-value | Case | Mean ± SD | P-value |

| Tissue | ||||||

| Benign | 7 | 2.43±1.72 | 0.019 | 29 | 5.79±0.16 | <0.001 |

| Cancer | 73 | 5.12±2.91 | – | 150 | 6.20±0.61 | – |

| Age | ||||||

| <66 | 24 | 5.17±2.88 | 0.930 | 12 | 56.18±0.57 | 0.421 |

| ≥66 | 49 | 5.10±2.95 | – | 25 | 6.29±0.75 | – |

| Serum PSA | ||||||

| <10 | – | – | – | 105 | 6.08±0.47 | 0.009 |

| ≥10 | – | – | – | 42 | 6.37±0.63 | – |

| Gleason score | ||||||

| ≤7 | – | – | – | 117 | 6.05±0.44 | 0.004 |

| ≥8 | – | – | – | 22 | 6.59±0.77 | – |

| Pathological stage | ||||||

| I–II | 43 | 4.26±2.37 | 0.002 | 86 | 6.03±0.41 | 0.007 |

| III–IV | 27 | 6.63±3.25 | – | 55 | 6.30±0.66 | – |

| TNM stage | ||||||

| ≤T2A | 45 | 4.16±2.25 | 0.001 | 135 | 6.14±0.55 | 0.028 |

| ≥T2B | 27 | 6.78±3.22 | – | 10 | 6.55±0.76 | – |

| Metastasis | ||||||

| No | – | – | – | 122 | 6.02±0.37 | <0.001 |

| Yes | – | – | – | 28 | 6.96±0.81 | – |

| PSA rise following treatment | ||||||

| Negative | – | – | – | 104 | 6.01±0.37 | 0.001 |

| Positive | – | – | – | 36 | 6.46±0.73 | – |

| Overall survival | ||||||

| Alive | – | – | – | 131 | 6.46±0.73 | 0.002 |

| Succumbed | – | – | – | 19 | 6.90±0.96 | – |

Data correspond with immunoreactive score from immunohistochemical analysis; TMA, tissue microarray; PSA, prostate serum antigen; TNM, Tumor-Node-Metastasis; SD, standard deviation; TPX2, Targeting protein for Xenopus kinesin-like protein 2.

As the tissue chip data did not contain additional clinicopathological parameters, including metastasis, PSA level or biochemical recurrence time, the Taylor dataset, an online PCa dataset, was used for the analysis of survival and prognosis. The results of the analysis of the Taylor dataset revealed that PCa at later pathological stages (III–IV) demonstrated increased TPX2 expression compared with PCa in earlier pathological stages (I–II). In addition, statistical analyses of the Taylor dataset also indicated that PCa with a Gleason Score ≥8 exhibited a higher expression of TPX2 compared with those with a Gleason Score <8 (P=0.004) at the mRNA level (Table II).

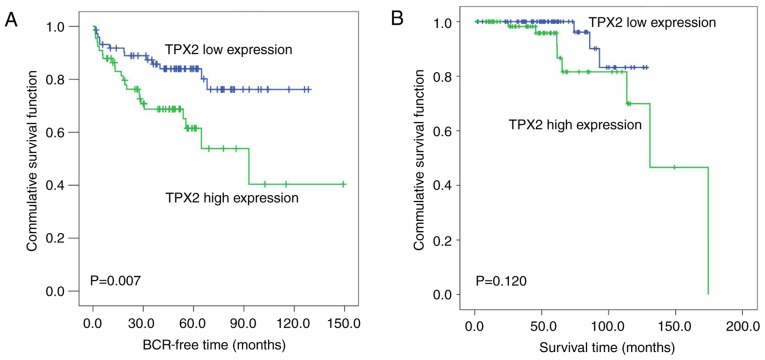

The Kaplan-Meier method was then used to analyze the association of TPX2 expression levels with the biochemical recurrence-free time and the overall survival time of patients with PCa in the Taylor dataset. The median TPX2 expression (~6.03) in all PCa patients was used as the cutoff to divide all PCa tissues into high (n=74) and low (n=74) TPX2 expression groups. As demonstrated in Fig. 2A, the biochemical recurrence-free time of the high TPX2 group was shorter compared with the low group (P=0.007; Fig. 2A). However, no significant association between the overall survival time and TPX2 expression was observed in patients with PCa (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

High TPX2 expression is associated with poor prognosis in patients with PCa. (A) Kaplan-Meier analysis of the BCR time of patients with PCa with high TPX2 expression levels was shorter compared with those with low TPX2 expression levels (P=0.007). (B) The overall survival time of patients with PCa was not associated with TPX2 expression levels (P=0.120). TPX2, Targeting protein for Xenopus kinesin-like protein 2; PCa, prostate cancer; BCR, biochemical recurrence-free time.

Overexpression of TPX2 enhances the proliferation of PCa cells

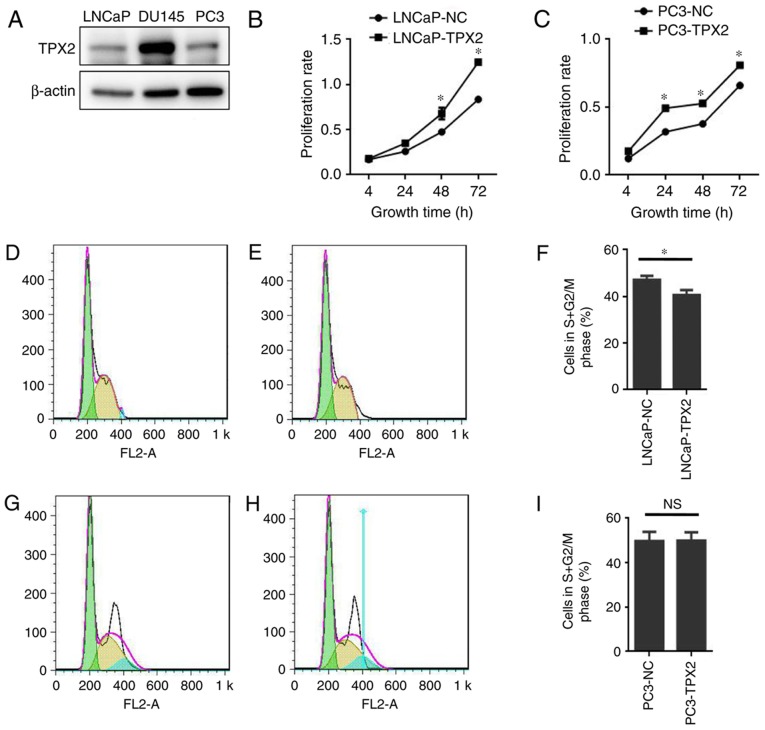

To assess the expression of TPX2 in human PCa cells, the expression of TPX2 in three established PCa cell lines: LNCaP; DU145; and PC3, was first assessed. Notably, TPX2 was highly expressed in the DU145 cell line, and weakly expressed in the LNCaP and PC3 cell lines (Fig. 3A). To determine the activity of TPX2 in PCa cells, LNCaP and PC3 cells were forced to express TPX2 by stable transfection. The CCK8 assay demonstrated that the LNCaP-TPX2 and PC3-TPX2 cell lines exhibited an increased proliferation rate compared with the empty vector-transfected cells (Fig. 3B and C). To determine whether overexpression affected cell proliferation, FACS analysis was used to examine the cell cycle. The results indicated that TPX2 arrested the cell cycle in G0 phase (Fig. 3D-F) in the LNCaP cells, but not in the PC3 cells (Fig. 3G-I).

Figure 3.

TPX2 expression and function in prostate tumor cell lines. (A) Western blotting detected TPX2 protein expression in PCa cell lines. TPX2 was highly expressed in the DU145 cell line, while expressed at low levels in the PC3 and LNCaP cell lines. The CCK8 assay indicated that the overexpression of TPX2 in (B) LNCaP and (C) PC3 cells promoted the proliferation rate of PCa cells compared with the control group. The flow cytometry assay conducted in (D) LNCaP-NC and (E) LNCaP-TPX2 cells suggested that TPX2 inhibited cell cycle transit from G0/G1 to S/M phase in LNCaP-TPX2 cells. (F) The average proportion of cells in S+G2 phase was 40.607±2.172 in the LNCaP-TPX2 group, while it was 47.09±1.804 in the LNCaP-NC group (P=0.016). (G) PC3-NC and (H) PC3-TPX2 cells were also examined using flow cytometry. (I) No significant difference in PC3 cells was observed (P>0.05). TPX2, Targeting protein for Xenopus kinesin-like protein 2; PCa, prostate cancer; NC, negative control; NS, not significant. *P<0.05.

Overexpression of TPX2 suppresses apoptosis in LNCaP cells

The data indicated that the LNCaP-TPX2 cells exhibited fewer apoptotic cells compared with the vector-transfected LNCaP cells (Fig. 4A-C). Docetaxel is a potent apoptosis inducer (19). Therefore, docetaxel-induced apoptosis in PC3 cells with or without forced expression of TPX2 was determined by Annexin V staining. Notably, there was no significant difference in apoptosis between PC3-TPX2 and PC3-NC cells when treated with docetaxel (36.92±1.49 vs. 38.49±2.36, respectively; P=0.383; Fig. 4D-F), suggesting that the anti-apoptotic activity of TPX2 was attenuated by docetaxel treatment.

Figure 4.

Overexpression of TPX2 inhibits apoptosis in LNCaP and PC3 cells. Cells overexpressing TPX2 were stained using Annexin V, and it was demonstrated that TPX2 decreased the rate of apoptosis in (A) LNCaP-NC and (B) LNCaP-TPX2 cells. (C) The apoptotic rate in the LNCaP-TPX2 group was 2.83±0.42, while it was 4.25±0.13 in the LNCaP-NC group (P=0.005). No difference in the apoptotic rate was observed between (D) PC3-NC and (E) PC3-TPX2 cells treated with docetaxel. (F) The apoptosis rates in the PC3-TPX2 and PC3-NC groups were similar (36.92±1.49 vs. 38.49±2.36; P=0.383). TPX2, Targeting protein for Xenopus kinesin-like protein 2; PCa, prostate cancer; NC, negative control; NS, not significant. *P<0.05.

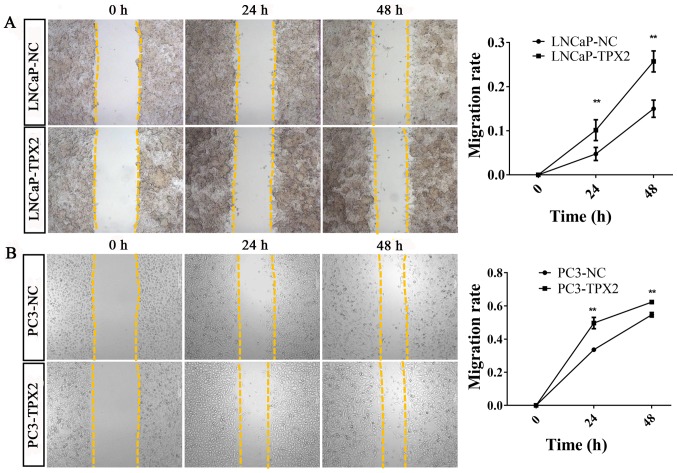

Overexpression of TPX2 enhances cell migration in PCa cells

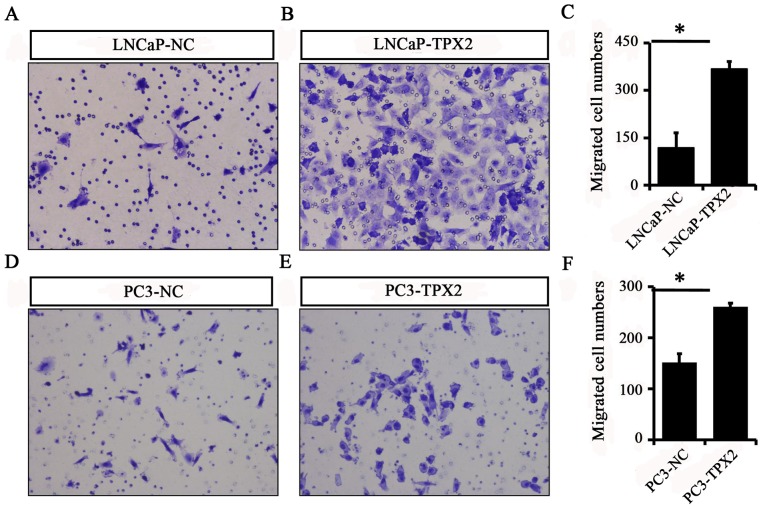

To identify whether TPX2 promoted cell mobility, A Transwell assay was used to assess the migration activity of LNCaP and PC3 cells with or without forced expression of TPX2. The results indicated that the migratory ability of the LNCaP-Tpx2 cells was increased compared with the LNCaP-NC cells (Fig. 5A-C). Similarly, the PC3-Tpx2 cells also exhibited increased migratory activity compared with the PC3-NC cells (Fig. 5D-F). Furthermore, the wound-healing assay revealed similar results to the migration assay (Fig. 6).

Figure 5.

Overexpression of TPX2 promotes the migration of LNCaP and PC3 cells. A Transwell assay was used to detect migration in (A) LNCaP-NC and (B) LNCaP-TPX2 cells. (C) The migration cell number in LNCaP-TPX2 group was 366.7±24.44, while it was 117.3±48.39 in LNCaP-NC group (P=0.022). A Transwell assay was also performed in (D) PC3-NC and (E) PC3-TPX2 cells. (F) The migration cell number in PC3-TPX2 group was increased compared with the PC3-NC group (260.0±8.0 vs. 150.7±18.04; P=0.041). Magnification of all images, ×400. TPX2, Targeting protein for Xenopus kinesin-like protein 2; PCa, prostate cancer; NC, negative control. *P<0.05.

Figure 6.

Overexpression of TPX2 enhanced wound healing of LNCaP and PC3 cells. Wound healing assay analysis was performed at 0, 24 and 48 h with or without TPX2 overexpression. The migratory ability was increased in (A) LNCaP-TPX2 and (B) PC3-TPX2 cells at 24 and 48 h. TPX2, Targeting protein for Xenopus kinesin-like protein 2; NC, negative control. **P<0.01.

Discussion

Although early detection of PCa through serum testing of PSA, and improved procedures of surgical intervention and radiation therapy have significantly decreased the number of fatalities, the prognosis of late-stage PCa remains poor (17). The current diagnostic biomarkers fail to predict the progression of PCa (17). Therefore, it is of importance to develop novel biomarkers for estimating the recurrence and metastatic potential of PCa (17). The TPX2 gene is located at chromosome 20q11.2, upstream of B-cell lymphoma 2. The kinase domain at the N-terminal region that connects to AURKA and the C-terminal region that anchors to the microtubules are the two important domains of TPX2 (20). Previous studies have suggested that the overexpression of TPX2 promoted the development of different types of tumors by enhancing microtubule assembly forming the spindle through activation of Ran-GTP pathway and the AURKA, followed by phosphorylation of Hepatoma upregulated protein, Cytoskeleton-associated protein 5A and Kinesin-like protein KIF2C (20,21). Furthermore, TPX2 was also associated with chromosomal abnormalities and DNA damage (22).

Aberrant activity of TPX2 has been confirmed in several types of cancer (23). Overexpression of TPX2 significantly enhanced the phosphorylation of Akt and increased the expression of cyclin D1 and matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-9 in glioma cells (23). In contrast, TPX2 knockdown inhibited cell proliferation and invasion through decreased Akt phosphorylation and expression of MMP-9 and cyclin D1 (23). Expression of TPX2 was significantly upregulated in renal cell carcinoma (RCC) and promoted the proliferative and invasive ability of RCC cells (24). In addition, it has been proposed that Absent in melanoma 1, Endoplasmic reticulum-Golgi intermediate compartment protein 1, Transmembrane emp24 domain-containing protein 3 and TPX2 are potential drug targets in PCa (25). TPX2 expression was associated with an increase in PSA following prostate cancer treatment, while silencing reduced the expression of PSA (25).

Chemotherapy has served a pivotal role in the treatment of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) since 2004, when docetaxel-based chemotherapy first exhibited modest improvement in survival time compared with mitoxantrone-based therapy as a first-line chemotherapy (26,27). While novel drugs have been developed, docetaxel remains one of the standard initial systemic therapies for patients with mCRPC. It has been recommended as the first-line drug in the 2015 National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines (28). However, a substantial proportion of patients with mCRPC treated with docetaxel eventually become refractory and progress due to the development of drug resistance (28). Docetaxel binding stabilizes microtubules, preventing the normal formation of mitotic spindles and their disassembly (29), while TPX2 promotes spindle assembly. Additional clarification of whether TPX2 overexpression reduces the function of docetaxel in promoting apoptosis is required.

In conclusion, the present study suggested that the overexpression of TPX2 improved the proliferative, invasive and migratory abilities and inhibited apoptosis of PCa cell lines. Overexpression of TPX2 was more frequently observed in high TNM and clinicopathological staging. Statistical analyses of the online Taylor dataset revealed that high TPX2 levels were associated with high Gleason scores, metastasis and PSA rising again following treatment, indicating that high-level TPX2 in PCa tissues indicated poor prognosis. Therefore, the preliminary conclusion of the present study is that the overexpression of TPX2 serves as a potential biomarker for PCa diagnosis and prognosis.

Previous studies have demonstrated that the proliferation and invasion of prostate cancer cells may be promoted by inhibiting the expression of TPX2 (30). The apoptosis results of the present study are in agreement with the published literature (30). The apoptotic rate in the PC3-TPX2 and PC3-NC groups were similar (36.92±1.49 vs. 38.49±2.36, respectively; P=0.383) when treated with docetaxel, which was in agreement with previous studies where the rate of apoptosis in the control groups of PC3 cells was 20–40% following docetaxel treatment (17,31). The apoptosis results obtained in the present study using docetaxel were not significant. Therefore, a different drug should be employed in future studies. In addition, to study the function of a gene, besides overexpression, knockdown of its expression is also important. DU145 cells exhibited high TPX2 expression in the present study, and therefore may considered a good model for conducting future experiments.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- TPX2

targeting protein for Xenopus kinesin-like protein 2

- PCa

prostate cancer

- PSA

prostate specific antigen

- TNM

clinical tumor-node-metastasis

Funding

The present study was supported by grants from the Guangzhou Health Science and Technology General Guidance project [Health Science and technology (2017) 6], Guangzhou Medical University Fund (grant no., 2015C26), Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (grant no., 2014A030310088), the Zhejiang Open Foundation of the Most Important (grant no., YFKJ003), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (grant nos., 2017PY023 and 2017MS127).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

WDZ supervised the entire study, participated in study design and coordination. JZ, RYH, FNJ, DXC, CW, ZDH and YXL performed most of the experiments and statistical analyses, and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

These procedures were approved by the Research Ethics Committee of The Third Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University (Guangzhou, China).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;1:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, Zhang S, Zeng H, Bray F, Jemal A, Yu XQ, He J. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;2:115–132. doi: 10.3322/caac.21338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Partin AW, Kattan MW, Subong EN, Walsh PC, Wojno KJ, Oesterling JE, Scardino PT, Pearson JD. Combination of prostate-specific antigen, clinical stage, and Gleason score to predict pathological stage of localized prostate cancer. A multi-institutional update. JAMA. 1997;277:1445–1451. doi: 10.1001/jama.1997.03540420041027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stamey TA, Caldwell M, McNeal JE, Nolley R, Hemenez M, Downs J. The prostate specific antigen era in the United States is over for prostate cancer: What happened in the last 20 years? J Urol. 2004;172:1297–1301. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000139993.51181.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zare-Mirzaie A, Balvayeh P, Imamhadi MA, Lotfi M. The frequency of latent prostate carcinoma in autopsies of over 50 years old males, the Iranian experience. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2012;2:73–77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Du P, Kumar M, Yao Y, Xie Q, Wang J, Zhang B, Gan S, Wang Y, Wu AM. Genome-wide analysis of the TPX2 family proteins in Eucalyptus grandis. BMC Genomics. 2016;1:967. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-3303-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tulu US, Fagerstrom C, Ferenz NP, Wadsworth P. Molecular requirements for kinetochore-associated microtubule formation in mammalian cells. Curr Biol. 2006;16:536–541. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.01.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shao C, Duan C, Wang J, Luan S, Gao Y, Jin D, Wang D, Li Y, Xu L. Expression of microtubule-associated protein TPX2 in human gastric carcinoma and its prognostic significance. Cancer Cell Int. 2016;16:79. doi: 10.1186/s12935-016-0357-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tomii C, Inokuchi M, Takagi Y, Ishikawa T, Otsuki S, Uetake H, Kojima K, Kawano T. TPX2 expression is associated with poor survival in gastric cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2017;1:14. doi: 10.1186/s12957-016-1095-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang Y, Li DP, Shen N, Yu XC, Li JB, Song Q, Zhang JH. TPX2 promotes migration and invasion of human breast cancer cells. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2015;12:1064–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.apjtm.2015.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miwa T, Kokuryo T, Yokoyama Y, Yamaguchi J, Nagino M. Therapeutic potential of targeting protein for Xklp2 silencing for pancreatic cancer. Cancer Med. 2015;4:1091–1100. doi: 10.1002/cam4.453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang Y, Guo W, Kan H. TPX2 is a prognostic marker and contributes to growth and metastasis of human hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:18148–18161. doi: 10.3390/ijms151018148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wei P, Zhang N, Xu Y, Li X, Shi D, Wang Y, Li D, Cai S. TPX2 is a novel prognostic marker for the growth and metastasis of colon cancer. J Transl Med. 2013;11:313. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-11-313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu Q, Yang P, Tu K, Zhang H, Zheng X, Yao Y. TPX2 knockdown suppressed hepatocellular carcinoma cell invasion via inactivating AKT signaling and inhibiting MMP2 and MMP9 expression. Chin J Cancer Res. 2014;26:410–417. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.1000-9604.2014.08.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takahashi Y, Sheridan P, Niida A, Sawada G, Uchi R, Mizuno H, Kurashige J, Sugimachi K, Sasaki S, Shimada Y, et al. The AURKA/TPX2 axis drives colon tumorigenesis cooperatively with MYC. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:935–942. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aushev VN, Lee E, Zhu J, Gopalakrishnan K, Li Q, Teitelbaum SL, Wetmur J, Esposti Degli D, Hernandez-Vargas H, Herceg Z, et al. Novel predictors of breast cancer survival derived from miRNA activity analysis. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24:581–591. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-0996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fu X, Chen G, Cai ZD, Wang C, Liu ZZ, Lin ZY, Wu YD, Liang YX, Han ZD, Liu JC, Zhong WD. Overexpression of BUB1B contributes to progression of prostate cancer and predicts poor outcome in patients with prostate cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2016;9:2211–2220. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S101994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zeng J, Liu W, Fan YZ, He DL, Li L. PrLZ increases prostate cancer docetaxel resistance by inhibiting LKB1/AMPK-mediated autophagy. Theranostics. 2018;8:109–123. doi: 10.7150/thno.20356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dávila-González D, Choi DS, Rosato RR, Granados-Principal SM, Kuhn JG, Li WF, Qian W, Chen W, Kozielski AJ, Wong H, et al. Pharmacological inhibition of NOS activates ASK1/JNK pathway augmenting docetaxel-mediated apoptosis in triple-negative breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24:1152–1162. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garrido G, Vernos I. Non-centrosomal TPX2-dependent regulation of the aurora A kinase: Functional implications for healthy and pathological cell division. Front Oncol. 2016;6:88. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2016.00088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fu J, Bian M, Xin G, Deng Z, Luo J, Guo X, Chen H, Wang Y, Jiang Q, Zhang C. TPX2 phosphorylation maintains metaphase spindle length by regulating microtubule flux. J Cell Biol. 2015;10:373–383. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201412109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Castro Perez I, Malumbres M. Mitotic stress and chromosomal instability in cancer: The case for TPX2. Genes Cancer. 2012;3:721–730. doi: 10.1177/1947601912473306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gu JJ, Zhang JH, Chen HJ, Wang SS. TPX2 promotes glioma cell proliferation and invasion via activation of the AKT signaling pathway. Oncol Lett. 2016;12:5015–5022. doi: 10.3892/ol.2016.5371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen QI, Cao B, Nan N, Wang YU, Zhai XU, Li Y, Chong T. TPX2 in human clear cell renal carcinoma: Expression, function and prognostic significance. Oncol Lett. 2016;5:3515–3521. doi: 10.3892/ol.2016.4396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vainio P, Mpindi JP, Kohonen P, Fey V, Mirtti T, Alanen KA, Perala M, Kallioniemi O, Lljin K. High-throughput transcriptomic and RNAi analysis identifies AIM1, ERGIC1, TMED3 and TPX2 as potential drug targets in prostate cancer. PLoS One. 2012;7:e39801. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lohiya V, Aragon-Ching JB, Sonpavde G. Role of chemotherapy and mechanisms of resistance to chemotherapy in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Clin Med Insights Oncol. 2016;10(Suppl 1):S57–S66. doi: 10.4137/CMO.S34535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Antonarakis ES, Armstrong AJ. Evolving standards in the treatment of docetaxel-refractory castration-resistant prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2011;14:192–205. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2011.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamashita S, Kohjimoto Y, Iguchi T, Koike H, Kusumoto H, Iba A, Kikkawa K, Kodama Y, Matsumura N, Hara I. Prognostic factors and risk stratification in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer receiving docetaxel-based chemotherapy. BMC Urol. 2016;16:13. doi: 10.1186/s12894-016-0133-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang RC, Chen X, Parissenti AM, Joy AA, Tuszynski J, Brindley DN, Wang Z. Sensitivity of docetaxel-resistant MCF-7 breast cancer cells to microtubule-destabilizing agents including vinca alkaloids and colchicine-site binding agents. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0182400. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pan HW, Su HH, Hsu CW, Huang GJ, Wu TT. Targeted TPX2 increases chromosome missegregation and suppresses tumor cell growth in human prostate cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2017;10:3531–3543. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S136491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Banerjee S, Singh SK, Chowdhury I, Lillard JW, Jr, Singh R. Combinatorial effect of curcumin with docetaxel modulates apoptotic and cell survival molecules in prostate cancer. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 2017;9:235–245. doi: 10.2741/e798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.