Abstract

Background

Depression has a high impact on both patients and the people around them. These non-professional caregivers often experience overburdening and are at risk for developing psychological symptoms themselves. Internet interventions have the potential to be accessible and (cost)-effective in terms of reducing and preventing psychological symptoms. Less is known about their potential to decrease psychological distress among caregivers. The primary aim of this study is to evaluate (1) the user-friendliness and (2) the initial short-term effects on psychological distress of ‘E-care for caregivers’, an internet based guided self-management intervention for non-professional caregivers of depressed patients.

Methods

A pilot randomized controlled trial (RCT: n = 80) comparing ‘E-care for caregivers’ (n = 41) with a waitlist-control group (n = 39). The primary outcome measure (user-friendliness) was assessed with the System Usability Scale (SUS) and semi-structured telephone interviews among participants. Interviews were qualitatively analyzed with thematic content analysis. Secondary outcomes were assessed through online questionnaires administered at baseline and post-intervention at six weeks among caregivers. Statistical analyses were conducted according to the intention-to-treat principle using regression techniques for the secondary outcomes.

Results

All participants were recruited within six weeks through online advertising. Two-thirds of participants experienced higher levels of psychological distress (K10 > 20). The internet intervention was evaluated as user-friendly by caregivers (average score of 81.5, range [0–100]). Results did not show a reduction in psychological distress or other secondary outcome measures. Sensitivity analyses showed a decreased quality of life in the control condition compared to the intervention condition (p = 0.02, Cohen's d = 0.44) and higher levels of mastery (p = 0.02, Cohen's d = 0.48) in the intervention condition compared to controls.

Discussion

The internet intervention was evaluated positively for usability and was considered as easy to use. The study did not show a reduction in symptoms of psychological distress. However, there were some indications that those completing the internet intervention perceived higher levels of mastery and a protective effect in quality of life post-intervention.

Strengths and limitations

As far as we know, this study is the first to examine the user-friendliness and initial effects of an internet intervention specifically designed for non-professional caregivers of depressed patients. As this was a pilot study, the findings should be interpreted with caution. We recommend investigating the possibilities of providing a (partially) sequential design as well as incorporating themes like stigma and expressed emotion in the online course and subsequent evaluation of the internet intervention in a full-scale RCT, with a six-month follow-up.

Trial registration

Netherlands Trial Register: NTR5268. Registered on 30 June 2015.

Keywords: Internet intervention, Pilot study, User-friendliness, Caregivers, Depression, Psychological distress

Highlights

-

•

Non-professional caregivers caring for depressed patients experience high levels of psychological distress and caregiver burden.

-

•

The internet intervention ‘Ecare 4 caregivers’ is an acceptable and feasible method to reach this group of caregivers and was evaluated positively.

-

•

The study did not show a reduction in symptoms of psychological distress.

-

•

Evaluation of the internet intervention in a full-scale RCT with a six-month follow-up is recommended.

1. Background

Depression is both common and disabling. In the Netherlands, the life time prevalence of depression is 20% (de Graaf et al., 2012). Worldwide, depression is the second greatest contributor to disability (Ferrari et al., 2013). It affects not only the depressed person but also their direct environment. Depressed patients require treatment and are in need of social support to deal with their condition (Backs-Dermott et al., 2010, Eom et al., 2012, Pfeiffer et al., 2011, Shimazu et al., 2011, Shim et al., 2012). However, professional help alone is often not sufficient and, due to budget restrictions in mental health care, emotional and practical care for depressed patients increasingly rests with non-professional caregivers (i.e. partners, parents, siblings, friends, neighbours, etc.) (Dutch Coalition Agreement, 2012). This increases the risk of overburden for the non-professional caregivers, and an increased risk for developing anxiety and depressive disorders themselves (Schene and van Wijngaarden, 1993, Struening et al., 2001, Magliano et al., 2006, de Boer et al., 2009, Denno et al., 2013, van Dorsselaer et al., 2007, Magliano et al., 2006, Tower and Kasl, 1996). Recent research in the Dutch general population by Tuithof et al. (2015) showed that non-professional caregivers who offer emotional support, who care for a close loved one and have limited financial resources are especially at risk for developing emotional disorders and should be targeted for prevention. Research by de Boer et al. (2009) has shown that 80% of non-professional caregivers perceive a need for peer support, professional guidance as well as information about depression.

Meta-analytic evidence from 21 RCTs (n = 1589) has shown that both support groups and group-based face-to-face psycho-educational interventions are effective for caregivers of patients with severe mental illnesses (Yesufu-Udechuku et al., 2015). The interventions are well-received, can improve the experience of caregiving and quality of life, and may reduce psychological distress. Yet, face-to-face interventions often do not fit into the full and unpredictable daily lives of the non-professional caregiver. Internet interventions that can be accessed 24/7 from someone's home, have the potential to reach a larger audience and may overcome these practical difficulties. Ample research has shown that internet interventions can be effective in reducing psychological distress, and are effective in preventing depressive- and anxiety disorders (Van 't Hof et al., 2009) and problematic alcohol use (Riper et al., 2014). The effect sizes are comparable to face-to-face treatment (Cuijpers et al., 2010, Andersson et al., 2014), and they have the potential to be more cost-effective (Donker et al., 2015). Internet-interventions are also relatively easy to implement and scalable. Few internet-interventions for non-professional caregivers have been developed, and the ones that were developed are mostly in the field of dementia (Boots et al., 2014, Blom et al., 2015). In a meta-analysis by Boots et al. (2014) of twelve studies, promising results were demonstrated in reducing symptoms of depression and improving self-efficacy, although study quality could be improved. A more recent RCT by Blom et al. (2015) showed the intervention is effective in decreasing symptoms of depression as well as anxiety.

There are some online interventions available for non-professional caregivers, but evidence-base is lacking. To our knowledge, no evidence-based internet intervention is currently available that specifically targets non-professional caregivers looking after a depressed patient. Given the one-year-prevalence of 5.2% of depressive disorders in the general population (de Graaf et al., 2012), a substantial number of caregivers at risk for psychological problems could benefit from more specialized online self-help. Therefore we have developed ‘E-care for caregivers’, a self-management internet intervention for the non-professional caregiver of depressed patients. The development of the internet intervention is described in the protocol paper of this study (Bijker et al., 2016). This paper describes the results of a pilot Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) to evaluate (1) the user-friendliness of ‘E-care for caregivers’, and (2) the initial effects of ‘E-care for caregivers’ on psychological distress, subjective burden, anxiety symptoms, level of mastery and quality of life.

2. Methods

This study is a pilot RCT with two arms. Participants were randomized to the online intervention ‘E-care for caregivers’ or a waitlist control group (WLC). Quantitative assessments were administered at baseline and 6 weeks later (post-intervention). A semi-structured telephone qualitative interview was conducted post-intervention. Participants in the WLC were offered the intervention after having completed the post-intervention assessment.

2.1. Study population

Non-professional adult caregivers of depressed patients (partners, parents, children, siblings, family or friends) were recruited via the Dutch Depression Association (Depressie Vereniging) through online newsletters (i.e. Landelijk Platform GGZ) and by advertisements on websites related to caregivers of people with depression (i.e. Labyrinth in Perspectief). Included were (self-reported) non-professional caregivers aged 18 years or older who looked after a depressed person (i.e. a child, parent, family or friend). Excluded were non-professional caregivers without internet access and those with no proficiency in Dutch.

2.2. Procedure

The Dutch Mental Health Foundation, called MIND (previously known as: Fonds Psychische Gezondheid) hosted the study website which contained information about the study, the option to contact the researcher for additional questions or concerns and the option to sign up. MIND is an independent foundation dedicated to prevent mental health problems and support those afflicted by it. It does so by providing information, conducting- and sponsoring scientific research and organizing national campaigns. The study was advertised at their website. People who registered were automatically directed to an online eligibility questionnaire after they had given online consent to take part. Those who were eligible were randomized to the intervention condition or the waitlist control group. Participants were invited to complete an online assessment 6 weeks after baseline (post-intervention). In addition, a selection of participants in the ‘E-care for caregivers’ intervention was approached for a qualitative interview (n = 11). Participants were selected via purposive sampling on demographic variables (age, gender, type of relationship with the patient). Deviant cases, i.e. participants who were very active or very inactive in their use of the intervention, were actively searched for using information on the internet forum, communication with the coach, or on the basis of their System Usability Scale (SUS) score. Participants who completed all data entry points received an incentive of 25 euro. The study has been reviewed and approved by the ethics committee of VU Amsterdam, Amsterdam, the Netherlands (VCWE- 2015-126).

2.3. Randomization and blinding

Group allocation was conducted by an independent researcher at an individual level stratified by baseline K10 score (cut-off score of 20) (Kessler et al., 2002, Donker et al., 2010). The allocation scheme was created with a computerized random number generator (Random Allocation Software) at an allocation ratio 1:1. Participants were randomized into two groups: E-care for caregivers or WLC. Due to the nature of the study, blinding of participants for group allocation was not possible.

2.4. Sample size

There are no definitive guidelines for sample size regarding pilot-studies. Based on a simulation study (Teare et al., 2014), a sample size of n = 35 per group is recommended to estimate pooled standard deviations for a continuous variable. Therefore, we conclude that a total sample size for a two-arm RCT with a minimum of n = 70 will be satisfactory to estimate pooled standard deviations.

2.5. Intervention: E-care for caregivers

The intervention was based on a self-help manual for family members of depressed people (Cuijpers, 1997), which was adapted based on the results of two focus groups (professional experts and non-professional caregivers who are currently caring for a depressed family member). The intervention comprised eight non-sequential modules based on psychoeducation and CBT-techniques according to Beck et al. (1979). The intervention included themes concerning information about depression, suicidality, communication and setting boundaries in caregiving, stress, burn-out and how to look after yourself. Each module included theory, exercises, examples of caregivers' experiences and short videos. Caregivers were allowed to be flexible regarding the pace – number – and order of the modules to suit their own needs as well as which modules they would like to follow (‘cherry-picking design’). Each module was designed so that it could be followed independently of other modules. The intervention was supported by personalized feedback from a coach in order to provide feedback and motivation. A mediated internet forum for peer contact was developed as a closed group in Facebook and subjects could choose to participate in sharing experiences.

The coach (who was trained in CBT and supervised by a licensed healthcare psychologist who is also a licensed CBT therapist) sent a minimum of four messages in the six-week intervention period to serve as a reminder and encourage participants to follow the modules they wanted as well as offering support. For more information regarding the development and content of the online intervention we refer to the protocol paper of this project (Bijker et al., 2016).

2.6. Assessments

All assessments of short-term effects are self-report measures and were administered online. All questionnaires were assessed both at baseline and post-intervention except for the SUS and semi-structured telephone interview.

2.6.1. System Usability Scale (SUS)

The SUS was used to assess the user-friendliness of the internet intervention post-intervention and is composed of 10 statements that are scored on a 5-point scale of strength of agreement [0–100]. Reliability is good (Cronbach's alpha 0.91) (Bangor et al., 2008).

2.6.2. Psychological distress

The Kessler-10 (K10) (primary outcome of the initial effects) was used to assess psychological distress (Kessler et al., 2002). It consists of 10 items which participants can score on a five-point Likert scale [10–50]. Reliability (Cronbach's α) of the Dutch K10 was 0.94 and validity was good (AUC 0.87). With a cut-off point of 20, the Dutch K10 reached a sensitivity of 0.80 and a specificity of 0.81 for any depressive and/or anxiety disorder (Donker et al., 2010).

2.6.3. Generalized anxiety disorder scale (GAD-7)

Anxiety symptoms were measured with the Dutch version of the GAD-7 (Spitzer et al., 2006). It consists of 7 items on a four-point scale; total score ranges from 0 to 21. With a cut-off point of 12 the web-based Dutch version is reliable and has a sensitivity of 0.83 and a specificity of 0.65 for generalized anxiety disorder (Donker et al., 2011).

2.6.4. Zarit Burden Interview

Subjective burden was measured with the Dutch version of the Zarit Burden Interview (Bédard et al., 2001). This questionnaire measures the consequences of long-term psychiatric- or physical illnesses of patients on non-professional caregivers. It consists of 12 items; total score ranges from 0 to 48. Bédard et al. (2001) found a Cronbach's alpha > 0.88 for the overall scale and high values for the personal strain factor and the role strain factor (respectively 0.89 and 0.77).

2.6.5. Quality of life

Quality of life was assessed with the EQ5D (Euroqol group, 1990). It measures health related quality of life and consists of five dimensions (mobility, self-care, main activity, pain and mood). The EuroQol valuations appear to have good test-retest reliability. The EQ5D thus distinguishes 486 unique health states. Each unique health state has a utility score which ranges from 0 (poor health) to 1 (perfect health). We used the single EQ5D summary index score.

2.6.6. Mastery

Perceived control of events and ongoing situations was assessed using a 5-item version of the Pearlin Mastery Scale (Pearlin and Schooler, 1978). The Mastery Scale has good psychometric properties and shows good reliability. Items were summed for a total mastery score (ranges from 5 to 25) with higher scores indicating greater perceived control (internal locus of control).

2.6.7. Semi-structured telephone interview

A semi-structured telephone interview was conducted after completion of the online intervention (n = 11) to test user-friendliness of the intervention in addition to the SUS. Interviews were held (LB) with non-professional caregivers about what aspects of the intervention they experienced as valuable; what they considered missing- and redundant elements and their thought about the user-friendliness of the program. They were also asked to give their opinion on how well the intervention fitted with and contributed to their everyday life and how they used the intervention to decrease their own burden. The interview started with the ‘grandtour-question’: ‘What was your experience using the online intervention?’ A topic guide was used for the remainder of the interview (see Appendix A.1). The interviews lasted approximately 30 min and were recorded for verbatim transcription.

2.7. Analysis

2.7.1. User-friendliness analysis

The scores of the SUS were analyzed by calculating the mean and standard deviation. Interview data was analyzed using thematic content analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006). The interviews were transcribed by an independent researcher with the help of the program Atlas.ti. Different themes were identified and described (Green and Thorogood, 2004) and subsequently categorized using the overall-themes used in the topic list. The quality of the data collection was ensured by a process of peer debriefing (independent researcher and LB). Participants were included until no new information was obtained.

2.7.2. Statistical analysis of initial short-term effects

The analyses were first conducted based on the intention-to-treat principle (ITT). Data of all participants (n = 80) was included, missing data due to loss of follow-up was imputed using multiple imputation. We imputed the data for all five outcome measures at the level of the total score of the questionnaires using the Fully Conditional Specification (FCS) approach. Missing data were imputed with 75 iterations for the algorithm to converge and 25 multiply imputed datasets. The model type for scale variables was Predictive Mean Matching (PMM). Regression analyses were performed on the 25 datasets and the results were combined into one pooled estimate. Linear regression was performed with the posttest scores as the dependent variable and the condition (E-care for caregivers and WLC) as the independent variable while controlling for baseline scores. To test the robustness of the findings per-protocol (PP) analyses were conducted in sensitivity analyses, meaning the observed data of participants who completed both baseline and posttest measurements (n = 61). Comparisons were made between groups for pre- and post-test measurements.

Results are presented as the mean and standard deviations of the pooled data (ITT). Between and within group effect sizes as well as effectiveness analyses were based on the pooled results of the imputed data (ITT). Standard effect sizes were calculated (Cohen's d) with confidence intervals. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 21 was used.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline characteristics and patient flow

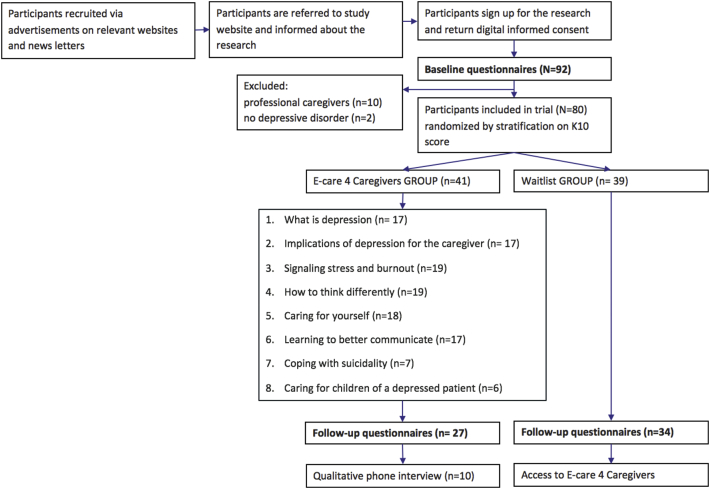

Non-professional caregivers of depressed patients were recruited in September and October 2015. Most of them directly through online channels like advertisements (n = 18) or newsletters (n = 33). The rest were referred indirectly by professional health care (n = 8) or through friends and family (n = 19). The flow of participants through the study is shown in Fig. 1. Ninety-two participants completed the baseline assessment. Twelve subjects were excluded because they did not meet the criteria of being an informal caregiver of someone with depression. After six weeks, 75% of the subjects completed the post-intervention measurements (66% experimental group, 85% WLC).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the trial.

Demographical characteristics of both the caregiver and the depressed patient are shown in Table 1. Non-professional caregivers were mostly female, highly-educated, in a paid job and married. About half of the caregivers lived with their depressed loved one and spent a minimum of 17 h a week on caregiving. In most cases this was a partner, parent or child. Further, 12.5% of the caregivers were using antidepressants or anxiety medication. Most depressed patients were receiving treatment, use antidepressants, and had been struggling with depression for more than two years, in most cases in addition to a comorbid psychological disorder. More than half of the depressed patients had dealt with suicidality. There were no significant differences between the intervention and the WLC condition.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics.

| Participants demographic and other characteristics at baseline | Intervention (n = 41) | Waitlist (n = 39) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (M, SD: range: 21–85) | 50 (12.8) | 49.8 (11.6) | 0.94 |

| Gender (F) | 80.5 (33) | 74.4 (29) | 0.51 |

| Education, n (%) | 0.47 | ||

| Low | 2 (4.9) | 4 (10.3) | |

| Middle | 12 (29.3) | 9 (23.1) | |

| High | 27 (65.9) | 26(66.7) | |

| Marital status, n (%) | 0.17 | ||

| Single | 10 (24.4) | 5 (12.8) | |

| Married/registered partners/living together | 24 (58.6) | 32 (82.0) | |

| Divorced/widowed | 7 (17.0) | 2 (5.2) | |

| Employment, n (%) | 0.12 | ||

| None | 9 (22.0) | 9 (23.1) | |

| < 24 h per week | 7 (17.1) | 6 (15.4) | |

| > 24 h per week | 25 (61.0 | 24 (61.5) | |

| Use of antidepressants or anxiety medication caregiver (n, % yes) | 7 (17.1) | 3 (7.7) | 0.21 |

| Type of relationship with depressed patient, n (%) | 0.09a | ||

| Parent | 14 (34.1) | 4 (10.3) | |

| Child | 6 (14.6) | 4 (10.3) | |

| Sibling | 2 (4.9) | 2 (5.1) | |

| Other relative | 0 (0) | 2 (5.1) | |

| Spouse/partner | 13 (31.7) | 22 (56.4) | |

| Friend | 4 (9.8) | 5 (12.8) | |

| Colleague/classmate | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0) | |

| Other | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0) | |

| Living together with depressed patient, yes n, % | 20 (48.8) | 26 (66.7) | 0.11a |

| Average hours of contact per week with depressed patient | 0.65 | ||

| < 4 h | 11 (26.8) | 10 (25.7) | |

| Between 5 and 16 h | 11 (26.8) | 7 (18.0) | |

| > 17 h | 19 (56.4) | 22 (52.9) | |

| Onset depression current episode, n (%) | 0.60 | ||

| Within the past half year | 4 (9.7) | 3 (7.7) | |

| Between half year and two years | 14 (34.2) | 8 (20.6) | |

| Between two- and five years | 17.1 (7) | 25.6 (10) | |

| More than five years | 39.0 (16) | 46.2 (18) | |

| Comorbid psychological disorder, yes, n (%) | 20 (48.8) | 15 (38.5) | 0.35 |

| Comorbid physical disorder, yes n (%) | 16 (39.0) | 14 (35.9) | 0.77 |

| Current treatment depressed patient | 0.34 | ||

| No treatmentb | 9 (21.9) | 4 (10.3) | |

| Primary care treatment | 5 (12.2) | 2 (5.1) | |

| Secondary mental health care | 26 (53.6) | 29 (74.3) | |

| Admitted to a mental health institution | 4 (9.7) | 4 (10.3) | |

| Other | 1 (2.4) | 2 (5.2) | |

| Use of antidepressants depressed patient, n (%) | 25 (58.5) | 29 (74.4) | 0.14 |

| Suicidality of depressed patient,cn (%) | 0.19 | ||

| Absent | 17 (41.5) | 7 (18.0) | |

| In the past, suicidal thoughts or -attempts | 16 (39.0) | 25 (64.0) | |

| Current suicidal thoughts | 8 (19.5) | 7 (18.0) |

This variable showed a trend but had no significant effect in the results when included as a covariate.

Unknown, no treatment, unwilling to receive treatment or waitlisted.

As assessed by non-professional caregiver.

3.2. Use of eCare

Of the 33 subjects (80%) who started the intervention, 14 subjects (43%) completed more than four modules. Eight caregivers did not start the internet intervention. All modules were equally popular in terms of usage (with an average of 18 subjects per module) with the exception of the modules concerning suicidality and children which were less frequently visited (7- and 6 participants respectively).

User-friendliness of the intervention was further assessed through the System Usability Scale and qualitative telephone interviews. Results of the SUS demonstrate that the online intervention was judged as user-friendly with an average score of 81.5 out of 100 (SD 8.9). Based on cut-off points described by Bangor et al. (2008) the online intervention can be interpreted as a ‘good and usable system’ (between 75 and 85).

Outcomes of the qualitative interviews were grouped in themes: content-, format-, use in everyday life of the intervention, feedback and suggestions for improvement. In Appendix A.2, representative quotes are shown per theme. Overall, the intervention was judged positively by all caregivers. They valued the intervention as being interesting, informative, educational and effective as well as useful and practical. Participants reported that the intervention was helpful in coping with the stressful situation of caring for a depressed loved one. Nevertheless, most caregivers reported that they experienced the intervention also as confronting. Particularly in realizing that they are going through a difficult situation as well, since they are so used to only looking after others instead of themselves. All interviewed caregivers would recommend the intervention to others.

“For me, the intervention has learned me that I need to take better care of myself and set some boundaries. Because that is my weakness, neglecting my own needs.” (p3).

3.2.1. Content of the intervention

The content of the intervention was judged positively. During the intervention, the experiences of two case examples were highly valued and made the caregivers feel less lonely. Some expected the content to focus more on practical advice on how to give better support as opposed to focusing on how to look after themselves.

“The part about ‘dealing with suicidality’ was the most intense for me, because my partner is done with living. But it was very realistic and practical in nature which made it very helpful. Intense though.” (p5).

3.2.2. Format of the intervention

The format in which the intervention was presented was valued as pleasant and organized. The variety in modules was considered to be well thought out. The writing style and tone was experienced as pleasant, friendly and easy to understand. The caregivers valued the flexibility of the program including the 24/7 accessibility and the choice of modules to work on. No technical problems were reported and the layout was experienced as well organized. The length of the modules was valued as pleasant and consistent. Most caregivers preferred to follow one module at a time.

“Very accessible and friendly in tone, no difficult language or something like that. Just very clear and practical. It was very nice, being able to pick and choose which modules I'd like to follow.” (combined p5, p10).

3.2.3. Use in everyday life

Although the intervention was experienced as flexible, caregivers did not find it easy to implement it in their weekly routine. More than half of the interviewed subjects mentioned that they did not want their depressed loved one to know about their participation in this project. Mostly, to protect them from feelings of guilt or to avoid conflicts. Also, for most caregivers the time period of six weeks for the intervention was not enough to follow all the modules they wanted. Many caregivers took notes during the intervention in order to keep information to aid them in the future. Noteworthy is that caregivers experienced that being aware of the burden of caregiving can be stressful and add more pressure in the short-term while they felt not prepared for this.

“I did not want my girlfriend to know I was following this intervention, it would have only made her feel more guilty and I did not want that.” (p2).

3.2.4. Feedback

The personalized feedback was considered helpful and non-judgmental. Some caregivers found it difficult to contact someone they had not met in person. Others found this an advantage because this allowed them to stay anonymous.

“Feedback was pleasant, very nice to have that option both practical and in supporting.” (p2).

3.2.5. Suggestions for improvement

All interviewed caregivers wanted the tools and information from the intervention to stay available for future reference. Other suggestions were to send weekly reminders by text message and making the pre- and post-evaluation accessible for the caregiver in order to track progress.

Caregivers reported that the intervention would benefit by discussing stigma. Caregivers reported having to deal with both stigma from the depressed person themselves (i.e. “I am worthless”) as well as stigma from outsiders (i.e. “She just needs a good night's sleep”). Further, the intervention did not include information on how to deal with comorbid psychological problems such as anxiety, aggression, or substance abuse. Also, some caregivers reported that the first reaction of depressed patients to some aspects of the intervention such as setting boundaries and looking after themselves could be negative. Some caregivers wanted more attention for this problem.

“It was really a shame that I could not look up anything after I finished the intervention. I would have liked to have the information available in case I need it in the future.” (p4).

3.2.6. Conclusion

In conclusion, participants reported and judged the intervention as beneficial and helpful, though confronting at times. This is likely related to the experienced burden that caregivers reported, their feelings of isolation and a tendency among caregivers to stop focusing on their own desires and needs in life.

“You know you have to take care of yourself but that feels like a burden too. In the sense that you are so aware of it, like (sarcastic) ‘You know you can't afford to fall into pieces’. I am not ready for that, if I really look at how I am doing I would break down, so I focus on my son now.” (p6).

3.3. Initial short-term effects

As shown in Table 2, baseline scores did not differ significantly between the experimental- and waitlist condition for the primary outcome measure psychological distress (K10) although the control group seems to experience more distress posttest than at baseline. The baseline scores of the K10 also show that more than half of the caregivers score above the cut-off point of 20 meaning they experience high levels of psychological distress. There were no significant differences between the intervention condition and the waitlist control group with respect to secondary outcome measures.

Table 2.

Intention-to-treat sample: baseline and post intervention outcomes and effectiveness of the intervention compared to the waitlist condition.

| Outcome variable | Intervention (n = 40) |

Waitlist (n = 40) |

P-value | t | Cohen's d between Exp vs. waitlista | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline M (SD) |

Posttest M (SD) |

Cohen's d withina | Baseline M (SD) |

Posttest M (SD) |

Cohen's d withina | ||||

| Psychological stress (K10) | 24.7 (9.6) | 25.3 (8.3) | 0.07 (− 0.37–0.51) | 22.9 (7.9) | 25.5 (6.5) | 0.36 (− 0.08–0.80) | 0.38 | 0.9 | 0.03 (− 0.41–0.47) |

| Anxiety symptoms (GAD-7) | 6.9 (4.8) | 6.0 (4.8) | 0.18 (− 0.62–0.26) | 6.5 (5.1) | 6.3 (4.0) | − 0.03 (− 0.47–0.41) | 0.50 | 0.7 | 0.07 (− 0.37–0.51) |

| Quality of life (EQ-5D) | 0.8 (0.1) | 0.8 (0.2) | 0.05 (− 0.48–0.39) | 0.9 (0.2) | 0.7 (0.2) | − 0.69 (− 1.14 - -0.24) | 0.06 | − 1.9 | 0.35 (− 0.79–0.09) |

| Subjective experienced burden (ZARIT) | 22.3 (9.4) | 21.9 (10.0) | 0.04 (− 0.48–0.40) | 21.11 (7.66) | 22.7 (7.1) | 0.21 (− 0.22–0.66) | 0.40 | 0.8 | 0.09 (− 0.35–0.53) |

| Mastery (Pearlin Scale) | 23.5 (6.2) | 24.9 (5.7) | 0.24 (− 0.21–0.68) | 22.7 (5.2) | 22.7 (5.3) | 0 (− 0.44–0.44) | 0.21 | − 8.8 | 0.40 (− 0.84–0.04) |

95% confidence interval.

Sensitivity analyses (participants who completed both baseline- and posttest measurements) showed that participants in the intervention condition improved significantly on the secondary outcome measure of mastery (p < 0.01). Subjects in the intervention condition experienced a greater sense of mastery with a modest effect size (d = 0.48). Also, subjects in the WLC reported a significant lower quality of life (p = 0.02) at posttest (d = 0.44).

4. Conclusion and discussion

4.1. Discussion

In this pilot-study, the user-friendliness and initial effects of an internet intervention specifically designed for non-professional caregivers of people with depression was evaluated. The intervention was found user-friendly, the intervention was appreciated by participants in terms of content and lay-out. Delivering the intervention via internet was successful as well as recruiting participants for data collection. The quickly reached intended sample size (in six weeks) with minimal advertising compared to other internet interventions for caregivers (Blom et al., 2015) along with the positive reviews suggests the need for an intervention with this specific focus.

With regards to the initial short-term effects of the intervention, there was no effect found in the ITT-analyses. In the sensitivity analyses (those who completed the intervention), no effect for the primary outcome of psychological distress was found either. This is in line with previous research. Yesufu-Udechuku et al. (2015) found in their meta-analysis that psychoeducational interventions for caregivers caring for patients with mental health problems did not show a reduction in psychological distress at post-test either. However, they did find significant effects only at six-month follow-up. It could be that effects of ‘E-care’ becomes visible at a longer follow-up as well.

The absence of a decrease in psychological distress could also be related to the finding that caregivers experienced the intervention as confronting. Subjects reported that they realized how burdened their situation is (e.g. by recognizing stress signals of their body) and that they needed to take care for themselves, instead of only caring for the other person. Increased awareness of their situation is important as a first step to cope with stress and to prevent burn-out. However, it is important to closely monitor psychological distress symptoms during the intervention and to intervene when symptoms increase. Participants in the intervention group did not deteriorate in quality of life as compared to controls. They also demonstrated significantly higher levels of mastery. This means that they feel more capable to influence events around them. Mastery could be a more accurate outcome measure for this specific target group. Interestingly, Khalaila and Cohen (2016) and Maubach et al. (2012) showed in their study among a sample of informal caregivers that higher caregiver burden can effect depression indirectly through reduced mastery. Further research is needed to investigate whether this association also exists in a sample like ours.

More than half of the participants wished to keep their depressed loved ones unaware of the fact they signed up for this intervention, because they did not want their loved ones to feel guilty about their need for support. They followed the intervention when their loved one was not around, which limited accessibility of the course. When implementing the course, it may be recommendable to add a module about how to communicate their need to attend this course to their loved ones.

Although the internet intervention is accessible 24/7 from a location which is preferred by the caregiver, our data demonstrated that caregivers had difficulty implementing the intervention in their everyday life in terms of finding the time to use the interventions. Six weeks to follow an internet intervention might be appropriate for most patients as it provides structure and incentive. However, it does not seem to be suitable for this highly-burdened and busy group. They might benefit from this intervention when they have more time to incorporate the elements into their daily routines.

4.2. Strengths and limitations

A strength of this research is that it is the first study to test an internet intervention in a sample of informal caregivers caring for depressed patients. By using a mixed-methods design the results complement each other in providing more recommendations for future research in internet interventions for caregivers in the future.

There are also a number of limitations in this study. First of all, this research is a pilot study and the initial effects should be interpreted with caution. Although the sample was representative of the diverse nature of this group (e.g. great variance of hours spent caregiving, type of relationship with the depressed patient and severity of the depression), high heterogeneity within the group has made interpretation inconclusive. Also, the coaching during the intervention and the qualitative interviews as well as the self-report measures are collected by one psychologist and guarded by a process of peer debriefing. But this can lead to a bias in data collection.

Lastly, the study drop-out rate of 25% is commonly seen in internet interventions (Eysenbach, 2005) and can be related to the nature of eHealth interventions (anonymous and easy-in-easy-out), but this could have had an effect in the analysis specifically in small samples like this study.

4.3. Recommendations

With regards to the content of the internet intervention it is both noteworthy and worrisome that the baseline scores of this group of non-professional caregivers are relatively high. Participants reported high psychological distress and burden, and a relatively high proportion used antidepressant medication themselves. It is therefore recommended to closely monitor participants and whether they needed referral to more specialized mental health treatment.

Although participants valued the non-sequential delivery of the online course, it is important to consider whether a (partially) sequential route or adding weekly guidance from a coach would decrease psychological distress. Previous research shows that adding guidance to internet interventions may result in larger effect sizes (Cuijpers et al., 2010) compared to unguided internet interventions (Cuijpers et al., 2011). It would also be recommended to adapt a part of the content in light of the lessons learned in this study. Dealing with stigma (both in- and external) is one topic participants missed in this course. Also, previous studies with non-professional caregivers caring for someone with schizophrenia show that educating caregivers about ‘high expressed emotion’ is helpful in increasing effective communication (Waerden et al., 2000). This might also be appropriate for caregivers caring for someone with depression. Lastly, since the course was considered ‘confronting’ at times by participants, it would benefit from more information before starting the course that the goal is to support non-professional caregivers themselves as well as providing information about depression.

Further research is needed to examine the effects of this intervention in a full-scale RCT with a minimum of six-month follow-up. Similar interventions for non-professional caregivers report no decrease in psychological distress at post-test but a reduction is found at six months (Yesufu-Udechuku et al., 2015). Furthermore, this internet intervention requires further investigation into whether mastery is a potential mediator in treatment effect as this could lead to improved treatment guidelines for this sample. In addition, additional research into moderator effects is needed to investigate for whom the intervention would be more beneficial.

4.4. Conclusion

Results presented here underscore the need for more specialized treatment options for non-professional caregivers of depressed patients and subsequent research in order to support this highly burdened-, underrepresented group. The internet intervention was positively valued and seems to be a feasible method and means to reach this group. There was no effect found on psychological distress, there was even a slight, non-significant increase which might be caused by increased awareness of caregivers' burden. However, there was a protective effect found in quality of life and an increase in mastery in the intervention condition. This could be a mediator for a decrease in psychological distress.

Abbreviations

- RCT

Randomized Controlled Trial

- WLC

Waitlist control group

- K-10

Kessler-10

- GAD-7

Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale-7

- ZARIT-12

Zarit Burden Interview

- SUS

System Usability Scale

- SPSS

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

- ITT

intention-to-treat

- PP

per-protocol

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

TD obtained funding for the study, participated in the design and coordinated and supervised the study and data collection. AK, HR and PC obtained funding for the study and participated in the design of the study. AK coordinated the qualitative study. LB was responsible for data collection and analysis. LB, AK, and TD have drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding information

We would like to acknowledge the organizations who have provided funding for this project: Fonds NutsOhra (1303-065), VSB Fonds (20141096), and Fonds Psychische Gezondheid (2014-6819).

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the following people for their valued contribution to the development of the intervention: Nathalie Kelderman of the Depression Association; Jeroen Ruwaard and Wouter van Ballegooijen of the Clinical Psychology Department, VU University Amsterdam; Karin Verbeek, Mezzo National Association of non-professional caregiving and volunteers; Fransisca Goedhart, foundation Labyrinth in Perspectief; Franka Meiland of VU Medical Center Amsterdam; Toon Vriens and Truus Bijker of the LSFVP; Peter Paul Feith, Dementia Online and Geriant; Ad Kerkhof and Bregje van Spijker and their book: ‘Ruminating about suicide’; Stef Linssen, psychiatrist and author of the book: ‘Help, my partner is depressed’; Sybrenne le Mair, psychiatrist; Els Dozeman, nurse practitioner mental health; Joan van Belzen, Teun Griffioen and Evelyn Lakeman; Roxanne Brouwers Design; Matthew Johnstone and the World Health Organization (WHO) and their movie ‘The Black Dog’. For the qualitative analysis we would like to acknowledge Merijam Benkadour.

Appendix A. Qualitative analysis user-friendliness of the intervention

A.1. Topic List

Grandtour question: What was your experience in following this course?

Evaluation of the course

-

-

Would you rate your experience in following this course as positive or negative?

-

-

What was your general opinion regarding this course?

-

-

Was this course of value to you?

-

-

Would you recommend this course to others?

-

-

Could you recognize your own situation in the information that was presented?

-

-

Did you feel supported in this course?

Content

-

-

Which modules did you follow in this course?

-

-

Which modules, in particular, were enjoyable for you?

-

-

Which modules, in particular, were less enjoyable for you?

-

-

Did you learn new skills or receive new information?

-

-

Were there items or information redundant in your opinion?

-

-

Were there items or information you missed?

Form

-

-

What was your opinion regarding the manner in which the course was presented?

-

-

What was your opinion regarding the general lay-out of the course?

-

-

What was your experience in completing the assignments?

-

-

What was your experience in viewing the video fragments?

-

-

How did you feel about being able to read the experiences of two other non-professional caregivers?

-

-

What was your opinion about the length of each module?

-

-

What was your opinion about the technical applications of the course?

Feasibility

-

-

Were you able to follow the course alongside your daily activities?

-

-

What was your opinion regarding the time during which the course was available? (six weeks)

-

-

Did you plan a set day each week to follow the course or was your planning more flexible?

-

-

Did you complete more modules in one sitting?

-

-

Did you perceive any barriers in following this course?

User-friendliness

-

-

Did you perceive the course as easy in use?

-

-

Were there elements in this course you would like to see adapted?

Effects of the course

-

-

Have you acquired new skills or information during the course that you have put into use in your daily life?

-

-

Which skills or information have you put into practice?

-

-

How do you feel now compared to how you felt before the start of the course?

-

-

In what areas of your life have you perceived a change (if any)?

-

-

Do you feel like your relationship with your depressed loved one has changed in any way?

Feedback

-

-

Did you have any contact with the coach?

-

-

What was your experience in the contact with your coach?

-

-

Did you feel supported throughout this course by the coach?

A.2. Qualitative results of the semi-structured interviews

| Themes | Summary | Codes | Quotes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall evaluation of the course | The course was judged accessible and user-friendly. The non-professional caregivers were glad to take part in the experiment and most found it a pleasant experience. They also valued the course as being interesting, informative, educational and effective as well as useful and practical. The course was helpful in coping with the stressful situation of taking care of a depressed loved one’. The non-professional caregivers identified with the information presented in the course and found it applicable. Nevertheless, most caregivers reported the course could also be very confronting. Fortunately they felt the course offered enough support and empowerment and helped in processing the situation. All caregivers would recommend the course to others. Even if they are already involved in the treatment of their loved one suffering from a depression. | I would recommend the course to others I am glad to have participated in this course The course was great The course was confronting The course has helped me The course was practical The course was recognizable The course was accessible The course was strenuous The course was educational |

|

| Content | The content was judged mostly positive. In some cases caregivers were already familiar with the content or the content was not applicable to their situation. Fortunately, they were able to skip these themes. Most caregivers found no missing or incorrect information. During the course, the experiences of two non-professional caregivers were available. These were highly valued. It made the caregivers feel less lonely in their situation. Some expected the content would be focusing more on practical tips on how to better support their loved one suffering from a depression, as opposed to also focusing on how to look after yourself. The course themes were identifiable and illuminating. The information was clear and easily understood. The following aspects were mentioned in particular:

|

Reading about others in the same situation is very pleasant I appreciated the ‘Black dog’ movies The exercise about grieving was very insightful I have been made aware about my automatic thoughts Useful how to better learn to take care of yourself Learning how to better communicate most practical and useful part of the course How to cope with suicidality was intense but realistic I had expected more focus on depression instead of me as caregiver There was no redundant content Information in the course confirmed existing knowledge |

What I really appreciated was reading about two other people and their experiences in looking after a depressed person (p5) I really appreciated the ‘Black dog’ movies, I shared these with more people in my environment (p1) What was really helpful and confronting for me is the realizations in the part about grieving. You're really saying goodbye to someone who has always been there and who is now a different person (p3). I have been made more aware about my automatic thoughts. Very useful, we all do that (p8) It was useful how to better learn to take care of yourself (p1) Particularly learning about how to communicate more effectively was very helpful for me (p8) The part about ‘dealing with suicidality’ was the most intense for me, because my partner is done with living. But it was very realistic and practical in nature which made it very helpful. Intense though (p5) I had expected more focus on how to deal with a depressed person instead of me as caregiver in taking care of yourself. I was not looking for that, it was useful though (p8) There was nothing there that felt like a waste of time (p4) Some things in the course you kind of know already, but to read it is kind of an extra confirmation (p3) |

| Form | The form in which the course is presented was valued as pleasant and organized. The variety in themes is well-thought out. The style of writing was pleasant and easy to understand without sounding too simple or complicated (except for some misspellings). The tone is very friendly. Within the course an option was made available to fill in the name of your loved one which would then appear throughout the text and exercises. Caregivers found this option pleasant and helpful in making the course more personal, although they got a bit wary of doing this before every theme. Physically typing throughout the exercises was educational and for some more effective than talking. A number of caregivers found it unfortunate that the exercises were not available separately as well. Our subjects found it pleasant having the option to freely choose when you work on the course and on which theme. There were no technical problems reported and the layout was well organized. The videos were informative but not everyone watched them. The reasons range from having no sound on home computer to thinking watching videos is a waste of time. |

The form of the course was pleasant The variety in themes is well-thought-out. The style of writing was easy to understand The tone was friendly I was glad to be able to choose which modules I wanted to follow I have not seen the movies The lay-out was visually attractive The length of the modules was consistent There were no technical difficulties Physically typing the answers is more effective than talking It was a shame that I was not able to see my exercises in one convenient location |

The form of the course was pleasant and the variety in themes is well-thought-out. (p9) Very accessible and friendly in tone, no difficult language or something like that. Just very clear and practical (p5) It was very nice, being able to pick and choose which modules I'd like to follow (p10) I have not seen the movies, I followed the course at work, so I did not want to switch the sound on (P10) The lay-out was visually attractive and the length of the modules was consistent. I also experience no technical difficulties. As I work a lot with computers, I notice this kind of stuff (p2) When you write something down, it is more helpful in becoming aware of certain issues (p4) It was a shame that I was not able to see my exercises in one convenient location. In some other courses you can take home a workbook or something similar (p9) |

| Use in everyday life | Although the course was accessible online, caregivers surprisingly did not find it easy to implement it in their weekly routine. Interestingly, a much cited reason for this is that they did not want their depressed loved one to have knowledge about their participation in this project. Mostly, to protect them from feelings of guilt or avoid conflicts. Because most caregivers live with their depressed loved one, this seriously limits the opportunities available to follow the course. Also, for most caregivers six weeks for the course was not enough to follow the desired themes, although each theme took approximately 1 h to complete. There was too little time to integrate the exercises in their everyday life during this period, although later on this would be possible. The caregivers did find it pleasant to be able to do the course in their own timeframe and some even developed their own routine. Many caregivers took notes during the course in order to store some information to aid them in the future. The length of the themes was valued as pleasant and consistent. Most caregivers preferred one theme a time because they feel that otherwise “their head gets too full”. Some caregivers experienced that caring for yourself consciously can be stressful and add more pressure in the short-term and they were not (yet) ready for this. |

My depressed loved one does not know that I am following this course I do not want to add to feelings of guilt Consciously taking care of yourself adds more pressure I followed one module in one sitting The course fits in everyday life I made notes during the course I would have liked more time to follow more modules |

I did not want my girlfriend to know I was following this course, it would have only made her feel more guilty and I did not want that (p2) You know you have to take care of yourself but that feels like a burden too. In the sense that you are so aware of it, like (sarcastic) ‘You know you can't afford to fall into pieces’. I am not ready for that, if I really look at how I am doing I would break down, so I focus on my son now (p6) I took my time and followed one module per session. Because it was a lot of information and I wanted it to sink in and it did need some time to sink in (p5) It was very easy for me to incorporate this course in my daily life. You just take your laptop on your lap on the couch for about half an hour whenever you want to and then you can come back to it later. (p3) There were very good tips throughout the course, I made lots of notes. I even had a little extra notebook (p5) I would have liked more time to follow more modules (p1) |

| Effects of the course | Overall, the caregivers reported they have gathered a lot of information and many practical tools from the course. They report to have learned to stand up for themselves, avoid becoming overinvolved, set boundaries, communicate more effectively and to take better care of themselves. By participating in the course, caregivers also experience more awareness of the influence of the stressful situation on themselves. The caregivers felt less alone thanks to the experiences of others and learned to turn for more (professional) help for themselves. In some cases the changes in the caregivers also had a positive effect on the loved one as well. | I have learned to better look after myself I communicate more effectively now The course has made me confront the current situation I have sought out more professional help Before this course, I felt alone The hardest part was learning I am not able to solve everything The current situation has not yet changed |

For me, the course has learned me that I need to take better care of myself and set some boundaries. Because that is my weakness, neglecting my own needs (p3) I communicate more effectively now (p1) It has made me more aware and confront the situation, you know, just asking directly ‘how are you doing’ or ‘how can I help’ (p6) Two weeks ago, I made my first appointment with a mental health care professional for myself, you know, just to spar about the situation (p4) Before this course, I felt alone. My girlfriend did not want me to share anything with anyone. I now have included her parents and this has taken some of the pressure of me (p2) The hardest part was learning I am not able to solve everything and realizing that it was also not my fault (p8) The current situation has not yet changed, it is a long and ongoing process (p1) |

| Feedback | Most caregivers reported, it was nice knowing the online coach is an actual person, present and always available for support. The coach did not give too many reminders. The personalized feedback was considered helpful and non-judgmental. Some caregivers also experience a barrier to contact someone they do not know face-to-face. Others report this as an advantage because they are able to stay anonymous. | Feedback was pleasant Feedback was non-judgmental It is hard to talk to someone who you don't see or have never met Reminders by the coach were sufficient When something you read gets to you, it is hard that you are not able talk about this directly |

Feedback was pleasant, very nice to have that option both practical and in supporting (p2) Very nice to receive feedback! Which was really helpful and practical and very non-judgmental. I really appreciated that. (p5) For me, I would not write my problems per mail probably because I have never met them. I can imagine it would work beneficial for others because you can remain anonymous. But for me, I would like to see someone face-to-face (p10) Reminders by the coach were sufficient (p1) When something you read gets to you, it is hard that you are not able talk about this directly (p2) |

| Suggestions | When asked if the caregivers had additional suggestions for further development, responses could be grouped in several common themes: Form: Most importantly, caregivers requested a need to have the tools and information in the course to stay available in some shape or form for future reference. It would also be great if the course could continue to be offered for free. Other suggestions are to send a weekly reminder by text message and adding a pre- and post-evaluation accessible for the caregiver. Lastly, the two experience-experts shown throughout the course were both caring for a depressed partner. More variety in the role would be appreciated. Some caregivers had worries about their privacy. More explanation regarding confidentiality and security could be given. Content: According to some caregivers the course would benefit by adding stigma to the content. Caregivers report having to deal with both stigma from the depressed person themselves (i.e. “I am worthless”) as well as stigma from outsiders (i.e. “She just needs a good night's sleep”). Also, frequent comorbid symptoms were not mentioned or how to deal with them, for instance anxiety, aggression, substance abuse, etc. Also, some caregivers report that in setting boundaries and looking after themselves, the first reaction from their depressed loved one could be negative. They would have liked to be made aware of this beforehand as well as tips how to deal with this. |

I would have liked to continue having access to the course for future reference Sending a text message would serve as a useful reminder I would have liked to read the experience of someone who isn't caring for a depressed partner but is family I would have liked to read how to deal with stigma I would like to know how to deal with common factors that frequently co-occur with depression I want to know what happens with all the information I share Starting to take care of myself has led to a negative reaction from my loved one and I was not prepared for this |

It was really a shame that I could not look up anything after I finished the course. I would have like to have the information available in case I need it in the future (p4). Maybe a text message would have been helpful for me, because I get so much email as it is (p7) I would have liked to read the experience of someone who isn't caring for a depressed partner but for someone else, like a parent (p8) You are constantly defending someone from the outside world about what it is to have a depression. Even from the person who has the depression. That kind of stigma, I would have liked some practical advice about how to deal with that (p7) There are other things that come with a depression, like physical things and aggression and anxiety. This alters how you deal with someone. Maybe some advice on that? (p8) Maybe it is something you can extra highlight, you know, what happens with all the information you share and how it is protected and stored (p4) It is just hard to give someone all the extra attention they seem to require, and when I tried to explain that I couldn't, I didn't expect such a strong reaction and I felt that this was a little lacking in the course (p8) |

| Other comments | Finally, there were a few overall comments not regarding the usability of the course. Mostly about the severity of the situation. In most cases the depressed loved one is not aware of the changes caused by the depression and in certain cases he or she is not open to seeking professional help. Caregivers are often in need of contact with fellow-sufferers. There is not much support or help available for caregivers with a loved one suffering from a depression which is why the current course was highly appreciated by many. | My loved one does not want professional help There is no support available for family of depressed patients I am frustrated with mental health care I worry about suicidality |

My partner does not want professional help (p2) I know there used to be support groups but they have all been cut in budget restrictions, which is frustrating because I think it would really help me and other people (p3) I am frustrated with mental health care (p6) I worry about my partner every time he comes home late or when I hear sirens because he has tried to commit suicide in the past (p5) |

References

- Andersson G., Cuijpers P., Carlbring P., Riper H., Hedman E. Guided Internet-based vs. face-to-face cognitive behavior therapy for psychiatric and somatic disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry. 2014;13(3):288–295. doi: 10.1002/wps.20151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backs-Dermott B.J., Dobson K.S., Jones S.L. An evaluation of an integrated model of relapse in depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2010;124:60–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bangor A., Kortum P.T., Miller J.T. An empirical evaluation of the System Usability Scale. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2008;24(6):574–594. [Google Scholar]

- Beck A.T., Rush A.J., Shaw B.F., Emery G. Guilford Press; New York: 1979. Cognitive Therapy of Depression. [Google Scholar]

- Bédard M., Molloy D.W., Squire L., Dubois S., Lever J.A., O'Donnell M. The Zarit Burden Interview: a new short version and screening version. The Gerontologist. 2001;41(5):652–657. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.5.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bijker L., Kleiboer A.M., Riper H., Cuijpers P., Donker T. E-care for caregivers — an online intervention for nonprofessional caregivers of patients with depression: study protocol for a pilot randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2016;17:193. doi: 10.1186/s13063-016-1320-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blom M.M., Zarit S.H., Groot Zwaaftink R.B., Cuijpers P., Pot A.M. Effectiveness of an Internet intervention for family caregivers of people with dementia: results of a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2015;10(2):e0116622. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116622. (13) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- de Boer A., Broese van Groenou M., Timmermans J. Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau; Den Haag: 2009. Non-professional Caregiving: An Overview of the Support of- and to Non-professional Caregivers in 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Boots L.M., de Vugt M.E., van Knippenberg R.J., Kempen G.I., Verhey F.R. A systematic review of Internet-based supportive interventions for caregivers of patients with dementia. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 2014;29(4):331–344. doi: 10.1002/gps.4016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers P. HB Uitgevers; Baarn: 1997. Depression: A Guide for Family Members. (Updated in 2014). [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers P., Donker T., van Straten A., Yuan L., Andersson G. Is guided self-help as effective as face-to-face psychotherapy for depression and anxiety disorders? A systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative outcome studies. Psychol. Med. 2010;21:1–15. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710000772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers P., Donker T., Johansson R., Mohr D.C., van Straten A., Andersson G. Self-guided psychological treatment for Depressive symptoms: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2011;6(6):e21274. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denno M.S., Gillard P.J., Graham G.D., DiBonaventura M.D., Goren A., Varon S.F., Zorowitz R. Anxiety and depression associated with caregiver burden in caregivers of stroke survivors with spasticity. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2013.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donker T., Comijs H.C., Cuijpers P., Terluin B., Nolen W.A., Zitman F.G., Penninx J.H. The validity of the Dutch K10 and EK10 screening scales for depressive and anxiety disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2010;176:45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donker T., van Straten A., Marks I., Cuijpers P. Quick and easy self-rating of generalized anxiety disorder: validity of the Dutch web-based GAD-7, GAD-2 and GAD-SI. Psychiatry Res. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donker T., Blankers M., Hedman E., Ljótsson B., Petrie K., Christensen H. Economic evaluations of Internet interventions for mental health: a systematic review. Psychol. Med. 2015 doi: 10.1017/S0033291715001427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dorsselaer S., de Graaf R., ten Have M. Trimbos-instituut; Utrecht: 2007. Het verlenen van mantelzorg en het verband met psychische stoornissen. (Resultaten van de ‘Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study (NEMESIS)). [Google Scholar]

- Dutch Government Coalition Agreement Rutte II. 2012. http://www.kabinetsformatie2012.nl/actueel/documenten/regeerakkoord.html (Accessed 23 Nov 2012)

- Eom C.S., Shin D.W., Kim S.Y., Yang H.K., Jo H.S., Kweon S.S., Kang Y.S., Kim J.H., Cho B.L., Park J.H. Impact of perceived social support on the mental health and health-related quality of life in cancer patients: results from a nationwide, multicenter survey in South Korea. Psycho-Oncology. 2012 doi: 10.1002/pon.3133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EuroQol Group A new facility for the measurement of health related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16(3):199–208. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenbach G. The law of attrition. J. Med. Internet Res. 2005;7(1):e11. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7.1.e11. (PMID: 15829473 PMCID: PMC1550631) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari A.J. Burden of depressive disorders by country, sex, age, and year: findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. PLoS Med. 2013 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Graaf R., ten Have M., van Gool C., van Dorsselaer S. Prevalence of mental disorders and trends from 1996 to 2009. Results from the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study-2. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2012;47(2):203–213. doi: 10.1007/s00127-010-0334-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green J., Thorogood N. Sage; London: 2004. Qualitative Methods for health Research. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R.C., Andrews G., Colpe G. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol. Med. 2002;32:959–976. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalaila R., Cohen M. Emotional suppression, caregiving burden, mastery, coping strategies and mental health in spousal caregivers. Aging Ment. Health. 2016;20(9):908–917. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2015.1055551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magliano L., Fiorillo A., Malangone C. Patient functioning and family burden in a controlled, real-world trial of family psychoeducation for schizophrenia. Psychiatr. Serv. 2006;57(12):1784–1791. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.12.1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maubach Multiple mediators of the relations between caregiving stress and depressive symptoms. Aging Ment. Health. 2012;16(1):27–38. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2011.615738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin L.J., Schooler C. The structure of coping. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1978;19:2–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer P.N., Heisler M., Piette J.D., Rogers M.A.M., Valenstein M. Efficacy of peer support interventions for depression: a meta-analysis. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry. 2011;33:29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riper H., Blankers M., Hadiwijaya H., Cunningham J., Clarke S., Wiers R. Effectiveness of guided and unguided low-intensity internet interventions for adult alcohol misuse: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e99912. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schene A.H., van Wijngaarden B. Amsterdam Medical Center; Amsterdam: 1993. Family Members of People with a Psychiatric Disorder: A Study Including Ypsilon Members. (1993) [Google Scholar]

- Shim R.S., Ye J., Baltrus P., Fry-Johnson Y., Daniels E., Rust G. Racial/ethnic disparities, social support, and depression: examining a social determinant of mental health. Ethn. Dis. 2012;22(1):15–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimazu K., Shimodera S., Mino Y., Nishida A., Kamimura N., Sawada K., Fujita H., Furukawa T.A., Inoue S. Family psychoeducation for major depression: randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2011;198:385–390. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.078626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer R.L., Kroenke K., Williams J.B.W., Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006;166(10):1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struening E.L., Perlick D.A., Link B., Hellman F., Herman D., Sirey J. The extent to which caregivers believe most people devalue consumers and their families. Psychiatr. Serv. 2001;52(12):1633–1638. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.12.1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teare M.D., Dimairo M., Shephard N., Hayman A., Whitehead A., Walters S.J. Sample size requirements to estimate key design parameters from external pilot randomized controlled trials: a simulation study. Trials. 2014;15:264. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tower R.B., Kasl S.V. Gender, marital closeness, and depressive symptoms in elderly couples. J. Gerontol. Psychol. Sci. 1996;51:115–119. doi: 10.1093/geronb/51b.3.p115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuithof M., ten Have M., van Dorsselear S., de Graaf R. Emotional disorders among informal caregivers in the general population: target groups for prevention. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:23. doi: 10.1186/s12888-015-0406-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van 't Hof E., Cuijpers P., Stein D.J. Self-help and internet-guided interventions in depression and anxiety disorders: a systematic review of meta-analyses. CNS Spectr. 2009;14(s3):34–40. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900027279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waerden A.J., Tarrier N., Barrowclough C., Zastowny T.R., Armstrong Rahill A. A review of expressed emotion research in health care. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2000;20(5):633–666. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yesufu-Udechuku A. Interventions to improve the experience of caring for people with severe mental illness: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2015;206:268–274. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.147561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]