Abstract

A growing number of researchers are using Facebook to recruit for a range of online health, medical, and psychosocial studies. There is limited research on the representativeness of participants recruited from Facebook, and the content is rarely mentioned in the methods, despite some suggestion that the advertisement content affects recruitment success. This study explores the impact of different Facebook advertisement content for the same study on recruitment rate, engagement, and participant characteristics. Five Facebook advertisement sets (“resilience”, “happiness”, “strength”, “mental fitness”, and “mental health”) were used to recruit male participants to an online mental health study which allowed them to find out about their mental health and wellbeing through completing six measures. The Facebook advertisements recruited 372 men to the study over a one month period. The cost per participant from the advertisement sets ranged from $0.55 to $3.85 Australian dollars. The “strength” advertisements resulted in the highest recruitment rate, but participants from this group were least engaged in the study website. The “strength” and “happiness” advertisements recruited more younger men. Participants recruited from the “mental health” advertisements had worse outcomes on the clinical measures of distress, wellbeing, strength, and stress. This study confirmed that different Facebook advertisement content leads to different recruitment rates and engagement with a study. Different advertisement also leads to selection bias in terms of demographic and mental health characteristics. Researchers should carefully consider the content of social media advertisements to be in accordance with their target population and consider reporting this to enable better assessment of generalisability.

Keywords: Facebook, Methodology, Recruitment, Online recruitment, Engagement, Selection bias

Highlights

-

•

Different Facebook advertisement content for the same online study led to different recruitment rates for men.

-

•

Participants recruited from the different advertisements engaged in the study in different ways.

-

•

Participants recruited from the different advertisements varied in their demographic and mental health characteristics.

-

•

Researchers to carefully consider the content of the social media advertisements and consider reporting details.

1. Introduction

Researchers are increasingly turning to the Internet and social media to recruit participants for health, medical, and psychosocial research. Social media networks such as Facebook can instantaneously reach a wide audience or target a specific population with round-the-clock access, providing significant advantages over traditional recruitment methods (Andrews, 2012). In particular, the widespread popularity and targeted advertising capabilities of Facebook make it an important tool for recruiting participants. Facebook has been used to recruit hard to reach groups, such as those in stigmatized communities (Martinez et al., 2014) or minority ethnic groups (Baltar and Brunet, 2012), but also people from the general population (Batterham et al., 2016). Indeed, a recent systematic review reported over 100 studies have used Facebook to recruit participants for health, medical or mental health research, all within the last 8 years (Thornton et al., 2016).

There are two main avenues to recruit participants via Facebook. Researchers can directly promote the study's Facebook page or website through paid text and image-based advertisements displayed on the news feed or side panel. Paid advertisements can be customized towards the interests, demographics, and location of the target population. Facebook also provides a source for snowball recruitment as users can recruit others in their social network into the studies. Most studies have utilized Facebook's paid advertising feature to attract people clicking to the study website (Thornton et al., 2016). Facebook recruitment was found to be cost-effective and rapid, with researchers paying on average USD $17 per completer (range $1.36–$110) for a range of topics, populations, study designs and settings (Thornton et al., 2016). It is likely that more future studies will make use of Facebook as the main source of recruitment.

However, there is limited research on the representativeness of participants recruited from Facebook, and studies that examine this tend to look at demographic factors as proxies of generalizability. For instance, Thornton et al. (2016) reported only 16 out of 110 studies tested the representativeness of their Facebook recruited sample. Their systematic review found that only 36% of studies were representative of the population of interest, although 86% of studies reported similar representativeness to those recruited through traditional methods. Facebook recruits tend to have higher education, but no systematic gender or age differences (Thornton et al., 2016). Further, it has been found that various online recruitment methods attract people from different demographics who engage differently in the same study (Antoun et al., 2016). For example, online recruitment strategies that target people who are not actively looking to participate in research tend to attract more diverse participants, but they were less willing to provide personal information compared to those who were actively looking to participate in research online. Yet many internet and mobile health studies recruiting participants online do not report participant engagement, which is an important metric to determine the generalizability of the study results (Lane et al., 2015).

Specifically, few studies have examined the representativeness of participants recruited from Facebook or social media among studies for mental health problems. Lindner et al. (2015) found that participants seeking internet-administered cognitive behavioural therapy for depression differed in demographic and clinical characteristics depending on the source of recruitment. Another study found that participants recruited from Facebook to an online mental health survey tended to be younger compared to respondents to postal surveys (Batterham, 2014). Further, the study found that there was an over-representation of people with mental health problems recruited from Facebook compared to those recruited via traditional methods, and they were more likely to complete the surveys than those without mental health problems.

It is unclear whether different Facebook advertisements also lead to different participant characteristics and engagement. Studies have often used a range of advertisements to promote a study on Facebook, but then grouped participants recruited from different advertisements together in the results (Fenner et al., 2012, Nelson et al., 2014). It has been found that Facebook advertisements with different wording and images can lead to varying recruitment rates (Ramo and Prochaska, 2012). For example, in comparing different images and message types on Facebook, advertisements with the study logo and general information led to more clicks to an online study (Ramo et al., 2014). This presents potential for self-selection bias if people are more likely to engage in the study because the advertisement interests them, and if they have different characteristics to those who do not participate. For instance, Batterham (2014) found that negative terminology (e.g. “mental health problem”) rather than positive terminology (e.g. emotional well-being”) in Facebook advertisements led to higher completion rates in a mental health survey. This suggests that the content of Facebook advertisements may potentially lead to self-selection bias during recruitment and affect the generalizability of study results.

The current study aimed to address these issues by 1) exploring the impact of different Facebook advertisement content for the same study on recruitment rates and engagement, and 2) examining whether the participants recruited from the different advertisements show systematic selection bias in their demographic and clinical characteristics. This study targeted men only because they are often a difficult group to recruit for mental health research using traditional methods (Woodall et al., 2010), but there is encouraging research suggesting Facebook may increase their participation rate (Ellis et al., 2014).

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants were recruited for an online study known as “Mindgauge” that allowed people to measure different aspects of their mental health and wellbeing. Individuals were eligible to participate in this study if they were 18 years or older, were resident in Australia, and had a reasonable understanding of the English language. As a consequence of the funding for this study, the aim was to target people in male-dominated industries.

2.2. Facebook recruitment

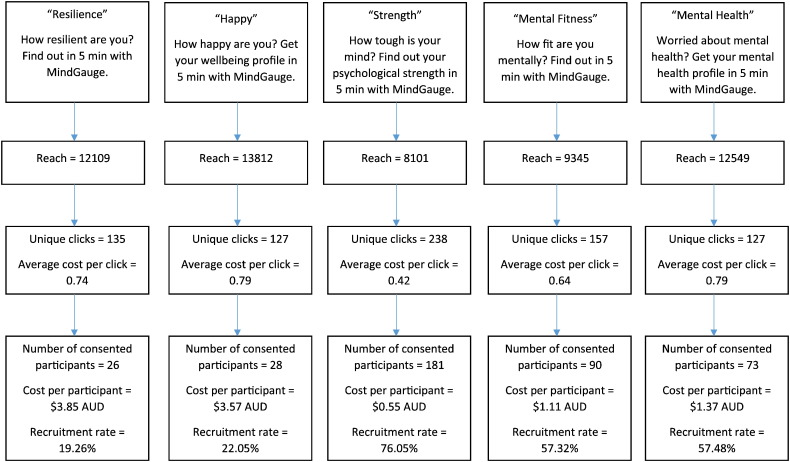

In order to test the impact of different Facebook advertisement content, five Facebook advertisement sets with themes focused on “mental fitness”, “resilience”, “happy”, “strength” and “mental health” were approved and launched simultaneously during 1–30 November 2015. Two proposed advertisement sets on “mental health” and “stress” were not approved by Facebook because the “mental health” image was believed to represent an “idealized body image”, while the use of the word “stress” allegedly contravened Facebook advertising policy. Fig. 1 describes the wording used for each of the remaining five advertisement sets and the flow of Facebook recruitment for each set.

Fig. 1.

Description and participant flow of the various Facebook advertisement sets.

Each advertisement set contained advertisements with the same wording together with one of a few images relevant to that particular set (e.g. a “mental fitness” advertisement had an image of a man sitting contently on a grass field; a “strength” advertisement had an image of a man licking an axe) (Supplementary Fig. A). A user experience specialist selected the images that were thought to align with the theme of each advertisement set. In order to reduce the effect of a certain image attracting users rather than the overall content, each advertisement set contained several different images, and some of these images overlapped between advertisement sets. Facebook displayed all the advertisements within each advertisement set until it is clear which particular image is best performing, and that advertisement will then be displayed the most (Facebook, 2017b). All advertisements also provided information that the study was “funded by Movember” to acknowledge the funding organization and to raise interest among the male target population.

All the Facebook advertisement sets were targeted to males aged from 18 to 65 + years (no upper age limit), in Australia, and in the transportation and moving, military, farming, fishing and forestry, protective service, or construction and extraction industries. Each advertisement set was given a lifetime budget of $100 Australian dollar (AUD) for the one month recruitment period. While the budget only allowed for a certain number of the potential Facebook target audience to be reached, Facebook did not provide information on the mechanisms that determined which advertisement set is shown to whom. However, when advertisement sets from the same advertiser targeted similar audiences, Facebook entered the one with the best performance history and prevented the others from competing to be shown (Facebook, 2017a).

Clicking on the Facebook advertisements directed interested individuals to the study website. Each Facebook advertisement set was tagged with a special code in the link to the study website. This allowed the researchers to cross-reference each participant with the specific Facebook advertisement set they clicked on.

2.3. Study enrolment and participation

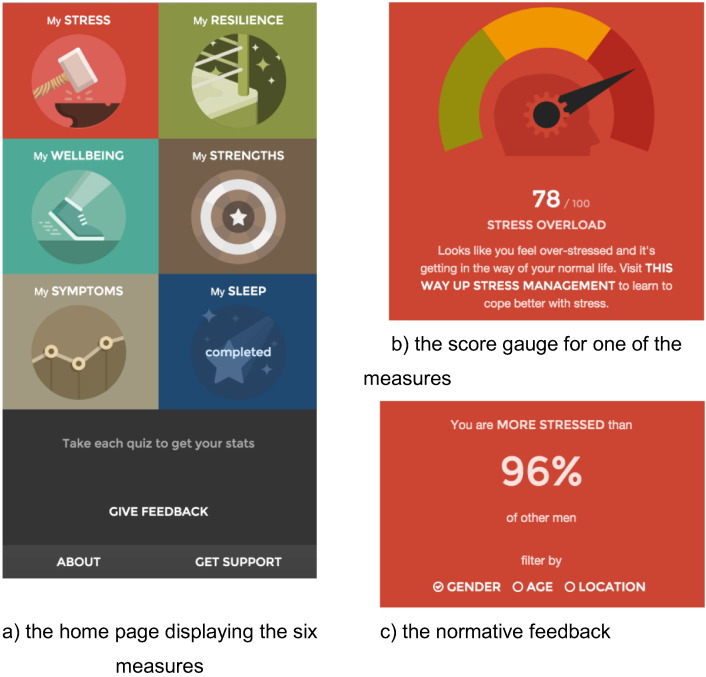

On the website landing page, interested individuals were provided with a participant information sheet outlining what was involved in the study. Individuals were counted as participants from the time they gave consent to participate in the study after reading the participant information sheet. Participants then filled out basic demographic details. As shown in Fig. 2a, the website then provided six different measures on symptoms, wellbeing, resilience, strengths, stress, and sleep (as described in the measures section). All six measures were offered to participants on one screen, with the order in which the measures were listed being varied randomly. Participants could choose to complete any of these measures in any order of their liking.

Fig. 2.

The MindGauge app.

Each measure produced a single numeric score, which was presented to the participant as a simple gauge as shown in Fig. 2b. For the sake of simplicity, all scores were normalized to fall between 0 and 100. The possible scores were subdivided into three ranges—low, medium, and high—which were colour-coded (as red, orange or green) to indicate desirability. For example, a low resilience range was coded red, while a low stress range was coded green. The ranges were generally determined by taking the population mean as the centre of the medium range, and taking one standard deviation each way as the range boundary. The only exceptions were the ranges for the symptoms measure (for which there are already established suitable ranges), and the sleep measure (for which there were no population statistics available and the ranges were simply evenly distributed). Below the gauge, participants were presented with a textual description that either congratulated them or encouraged them to improve matters, depending on the range they fell in. Those with the most undesirable range (as shown for stress in Fig. 2b) were given a link to an appropriate web-based intervention or resource. Participants could also compare their scores against other participants, as shown in Fig. 2c.

2.4. Measures

2.4.1. Facebook recruitment measures

Facebook provides data on the reach, unique clicks, and average cost per click for each advertisement set. Reach is defined as the number of unique users who saw the advertisement set. Unique clicks are the number of clicks to the website from the advertisement set.

The cost per participant was calculated by dividing the lifetime budget of each advertisement set ($100 AUD) by the number of consented participants. The recruitment rate of each advertisement set was calculated by dividing the number of participants by the number of website clicks from Facebook.

2.4.2. Self-reported measures

Participants completed the following self-reported measures within the website. Demographic questions were gender, age range, and employment status. Participants also rated their workplace gender balance on a scale from 1 to 5, with 1 being very female-dominated, 3 being balanced, and 5 being male-dominated.

2.4.2.1. Symptoms: Kessler 6-item scale (K6) (Kessler et al., 2002)

The K6 is a measure of nonspecific psychological distress validated for use among the Australian population (Furukawa et al., 2003). Scores range from 6 to 30, with higher scores indicating greater distress. Cronbach's alpha in the present study was good (α = .88). The K6 is presented on the website as the Symptoms measure.

2.4.2.2. Wellbeing: WHO (five) well-being index (WHO-5) (World Health Organization, 1998)

The WHO-5 is a commonly used measure of subjective wellbeing. Five items produce a score ranging from 0 to 25, with higher scores indicating better quality of life. The WHO-5 had good internal consistency in the current sample (Cronbach's α = .87). This was presented as the Wellbeing measure on the website.

2.4.2.3. Resilience: brief resilience scale (BRS) (Smith et al., 2008)

The BRS measures one's ability to bounce back from difficult times. Scores range from 6 to 30, with higher scores indicating better resilience. Cronbach's alpha in the present study was good (α = .85). The BRS was used as the Resilience measure.

2.4.2.4. Strength: Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC 10) (Campbell-Sills and Stein, 2007)

The CD-RISC 10 measures personal characteristics of resilience, such as the ability to tolerate change, pressure, and personal feelings. The scores ranged from 0 to 40, with higher scores indicating better positive functioning in the face of adversity. The scale had high internal consistency in the current sample (Cronbach's α = .91). The CD-RISC 10 was presented as a measure of Strength on the website.

2.4.2.5. Stress: perceived stress scale (PSS) (Cohen et al., 1983)

The PSS measures the extent to which one feels overwhelmed or under pressure. The 10 item measure produces a score from 0 to 40, with higher scores indicating greater stress. Cronbach's alpha in the present study was good (α = .89). The PSS was labelled as the Stress measure on the website.

2.4.2.6. Sleep measure

The sleep measure was developed for this study and had five questions about current sleep patterns. Participants were asked how often they had difficulties falling asleep, staying asleep, or waking up earlier than they would have liked, based on the Big Sleep Survey (Bin et al., 2012). The possible answers to these items ranged from “never, rarely, a few nights a month, a few nights a week, or almost every night” and were scored on a likert scale ranging from 4 to 0. Participants were also asked on average the number of hours of sleep they had each weekday night and weekend night. A response of “less than 6 h” resulted in a score of 0, “about 6 h” or “9 or more hours” resulted in a score of 1, and “about 7 h” or “about 8 h” resulted in a score of 2, based on recommended hours of sleep (Sleep Health Foundation, 2015). Scores where summed to create a total score ranging from 0 to 16, and a higher score indicated better sleep patterns. Cronbach's alpha in the present study was low (α = .61).

2.4.3. Objective website engagement measures

The study website automatically recorded several measures of engagement: active seconds using the website, whether a particular measure was completed, and the number of measures completed.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Results were analysed using IBM SPSS 24 statistical software. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the effectiveness of each advertisement set using statistics provided by Facebook and to describe the sample. Chi-square and between-group ANOVAs were used to analyse the difference between Facebook advertisement sets on engagement with the website application and scores on the measures. Age was controlled for in the analyses to adjust for age differences between participants in the different advertisement sets. Cohen's d is reported for post-hoc between group analyses.

2.6. Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee at the University of New South Wales (HC15584).

3. Results

3.1. Recruitment rate

During the one month recruitment period, 398 participants were recruited to the study website via paid Facebook advertising. Fig. 1 shows the respective reach of each advertisement set, unique clicks on the Facebook advertisements to the study website, average cost per click, number of participants recruited, average cost per participant for each advertisement set, and the recruitment rate. The advertisements that emphasized “strength” resulted in the most clicks on Facebook, had the lowest cost per click and per participant, and the highest recruitment rate. The “resilience” and “happiness” advertisements recruited the fewest participants despite relatively high reach and resulted in the most expensive cost per participant. The “mental health” and “mental fitness” advertisements resulted in similar recruitment rates.

3.2. Participant characteristics

Although the Facebook advertisement sets targeted men, 372 men and 26 women were recruited. One woman was recruited from the “resilience” advertisement set, four women were recruited from the “happy” set, three from the “strength” set, two from the “mental fitness” set, and 16 from the “mental health” set. The female participants were excluded from further analyses as this study was targeting recruitment for men.

Table 1 displays the demographic characteristics of the male participants across the Facebook advertisement sets. 231 participants (62%) were aged between 18 and 34 years, 100 participants (27%) were aged between 35 and 54 years, and 41 participants (11%) were 55 years or above. Chi-square analysis show significant differences in age range recruited from the different advertisement sets (p < .0005). The “happy” and “strength” advertisement sets recruited more participants in the 18–34 age range. 315 participants (85%) were employed and 57 (15%) were unemployed, retired, or students. There was no difference between advertisement sets on workplace gender balance, which was tending towards being more male-dominated (M = 3.86, SD = 1.01, p > .05).

Table 1.

Demographic and website engagement characteristics of male participants recruited via Facebook advertisements.

| Facebook advertisement set | Resiliencen = 25 | Happyn = 24 | Strengthn = 178 | Mental fitnessn = 88 | Mental healthn = 57 | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age range | ||||||

| 18–34 | 40.0% | 75.0% | 78.7% | 37.5% | 52.6% | χ2 = 65.381, p < .0005 |

| 35–54 | 28.0% | 20.8% | 19.1% | 39.8% | 33.3% | |

| 55 or above | 32.0% | 4.2% | 2.2% | 22.7% | 14.0% | |

| Employment status | ||||||

| Employed | 72.0% | 70.8% | 87.6% | 86.4% | 84.2% | χ2 = 8.049, p = 0.90 |

| Unemployed, retired, or student | 28.0% | 29.2% | 12.4% | 13.6% | 15.8% | |

| Website engagement | ||||||

| Mean active seconds (SD) | 402.88 (270.41) | 294.54 (189.66) | 288.69 (196.53) | 381.97 (221.52) | 358.02 (182.79) | F4, 365 = 2.843, p = .024 |

| Mean number of measures completed (SD) | 4.16 (2.54) | 3.75 (2.47) | 3.38 (2.37) | 4.16 (2.33) | 4.37 (2.18) | F4, 365 = 3.037, p = .017 |

3.3. Engagement with the website application

Measures of engagement with the website application are presented in Table 1. There was a significant difference in the amount of time engaged with the website by participants recruited through the different advertisement sets, as measured by active seconds (F4, 365 = 2.84, p = .024), while controlling for age range. Post-hoc comparisons using Tukey HSD test indicated that participants from the “strength” advertisements used the website for significantly shorter amounts of time than those recruited from the “mental fitness” set (p = .005, Cohen's d = 0.46). There was a significant difference in the number of measures completed among the different advertisement sets (F4, 365 = 3.04, p = .017), while controlling for age range. Post-hoc comparisons using Tukey HSD test showed that participants from the “strength” set completed significantly fewer measures than participants from the “mental health” set (p = .046, Cohen's d = .43). There were significant differences in whether the symptoms (p = .003), wellbeing (p = .002), and sleep (p = .005) measures were completed between the different advertisement sets (Table 2). The participants in the “strength” (53%) and “happy” (58%) sets were less likely to complete the symptoms measure compared to the “mental health” group participants (80%). Similarly, the “strength” (53%) and “happy” (54%) participants were less likely to complete the sleep measure compared to participants recruited from the “mental health” set (77%). Those recruited from the “strength” advertisements (50%) were also less likely to complete the wellbeing measure compared to the other groups (e.g.75% in both the “happy” and “mental health” groups).

Table 2.

Percentage of completion, means, and standard deviations of measures by Facebook advertisement set.

| Facebook advertisement set |

Resiliencen = 25 |

Happyn = 24 |

Strengthn = 178 |

Mental fitnessn = 88 |

Mental healthn = 57 |

Significance |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Completed | Mean (SD) | Completed | Mean (SD) | Completed | Mean (SD) | Completed | Mean (SD) | Completed | Mean (SD) | Completion | Means | Means: Significant post-hoc analyses | |

| Symptoms (K6) | 72.0% | 11.61 (4.43) | 58.3% | 15.50 (5.91) | 53.4% | 14.17 (5.33) | 67.0% | 12.76 (5.01) | 80.7% | 15.89 (5.39) | χ2 = 16.277, p = .003 | F4, 225 = 3.152, p = .015 | Mental health > Resilience (p = 0.029); Mental health > Mental fitness (p = 0.022) |

| Wellbeing (WHO-5) | 60.0% | 12.40 (4.05) | 75.0% | 12.67 (5.09) | 50.0% | 13.54 (5.32) | 65.9% | 14.21 (6.08) | 75.4% | 10.98 (5.57) | χ2 = 16.600, p = .002 | F4, 216 = 2.478, p = .045 | Mental fitness > Mental health (p = 0.032) |

| Strength (CD-RISC 10) | 68.0% | 24.47 (8.30) | 75.0% | 24.78 (8.01) | 62.9% | 26.77 (7.62) | 71.6% | 26.27 (8.02) | 70.2% | 20.85 (9.13) | χ2 = 3.147, p = .534 | F4, 243 = 4.319, p = .002 | Strength > Mental health (p = 0.001); Mental fitness > Mental health (p = 0.009) |

| Stress (PSS) | 72.0% | 16.61 (7.69) | 54.2% | 21.46 (7.38) | 60.7% | 18.53 (7.16) | 73.9% | 16.12 (7.81) | 68.4% | 20.18 (6.22) | χ2 = 6.584, p = .160 | F4, 236 = 2.558, p = .039 | Mental health > Mental fitness (p = 0.048) |

| Resilience (BRS) | 76.0% | 19.05 (4.71) | 58.3% | 19.79 (5.12) | 57.3% | 20.72 (4.27) | 67.0% | 21.20 (4.36) | 64.9% | 18.70 (3.95) | χ2 = 5.043, p = .283 | F4, 224 = 2.318, p = .058 | / |

| Sleep | 68.0% | 8.82 (2.72) | 54.2% | 9.23 (3.32) | 53.4% | 9.07 (3.27) | 70.5% | 8.65 (3.92) | 77.2% | 9.02 (2.76) | χ2 = 14.901, p = .005 | F4, 224 = 0.047, p = .996 | / |

3.4. Mental health characteristics

There was a significant difference in the scores on most of the mental health measures among the participants recruited through the different advertisement sets (symptoms measure: F4, 225 = 3.15, p = .015; wellbeing measure: F4, 216 = 2.48, p = .045; strength measure: F4, 243 = 4.32, p = .002; stress measure: F4, 236 = 2.56, p = .039), and while controlling for age range (Table 2). Post-hoc comparisons using Tukey HSD test showed that on the symptoms measure, participants recruited from the “mental health” advertisements (M = 15.89, SD = 5.39) had significantly higher scores than those recruited from the “resilience” (M = 11.61, SD = 4.43) (p = .029, Cohen's d = .85) and the “mental fitness” (M = 12.76, SD = 5.01) (p = .022, Cohen's d = .61) advertisement sets. Similarly, participants from the “mental health” advertisements (M = 10.98, SD = 5.57) scored significantly lower on the wellbeing measure than those recruited from the “mental fitness” advertisements (M = 14.21, SD = 6.08) (p = .032, Cohen's d = .56). On the strength measure, participants from the “mental health” advertisements (M = 20.85, SD = 9.13) had significantly lower scores compared to those recruited from the “strength” (M = 26.77, SD = 7.62) (p = .001, Cohen's d = .74) and “mental fitness” (M = 26.27, SD = 8.02) (p = .009, Cohen's d = .65) advertisement sets. Participants from the “mental health” advertisement set (M = 20.18, SD = 6.22) also scored significantly higher on the stress measure compared to the “mental fitness” advertisement set (M = 16.12, SD = 7.81) (p = .048, Cohen's d = .56).

Participants from different age ranges differed on their sleep score only (F2, 224 = 4.16, p = .017), while controlling for the Facebook advertisement sets. Post-hoc analysis showed that the 18–34 age group (M = 9.45, SD = 3.18) had better sleep than the 35–54 age group (M = 8.14, SD = 3.32) (p = .029, Cohen's d = .41).

4. Discussion

The results indicated that different Facebook advertisement content for the same study and website application had differential effects on recruitment rates, engagement, and participant characteristics. The different advertisement sets led to varying rates of recruitment for men, with the “strength” advertisement being the most cost-effective and resulting in the highest recruitment rate. It also appeared that participants recruited from the different advertisements engaged in the website in different ways. Participants recruited from the “strength” advertisements spent less time in the website and completed fewer measures. Participants from the “happy” and “strength” advertisements were less likely to complete the symptoms and sleep measure. Finally, participants recruited from the different advertisement sets varied in their demographic and mental health characteristics. Participants attracted to the “happy” and “strength” advertisements tended to be younger than participants recruited from the other advertisements. Participants recruited from the “mental health” advertisements had worse outcomes on most of the mental health measures than those from the other advertisement sets.

It is not surprising that different advertisement content leads to differential recruitment rates as reported in previous studies (Ramo et al., 2014). Similar to the findings in Batterham (2014), this study found that the advertisements with a problem focus (“mental health”, “mental fitness”) performed better than those framed positively (“resilience”, “happiness”). The major exception to this finding was that the “strength” advertisements (which is a positive term) had the highest recruitment rate. However, the participants recruited from the “strength” advertisements were least engaged in the study website, and were less likely to complete the symptoms, sleep, and wellbeing measures. This may have been because the actual measures in the study did not match their expectation of “strength”. Previous studies have suggested advertising content should be most effective when closely aligned with the study material (Batterham, 2014).

The advertisements about “strength” and “happiness” appealed most to younger men. This suggests that studies targeting young men may find that positively framed words without the attached stigma of mental health may be more successful in recruiting participants. However, participants from the “strength” and “happy” advertisements were less interested in completing the symptomatic measures (i.e. symptoms and sleep). These participants may not feel that the symptomatic measures were relevant to them, or that younger participants were less interested in these components. Indeed, this is supported by the finding that the participants from the “strength” advertisements had higher scores on the strength measure. Interestingly, they did not mind completing the stress measure, suggesting the term “stress” can have both positive and negative connotations. On the other hand, participants recruited from other advertisements with more of a psychological focus (“mental health”, “mental fitness”, and “resilience”) had a more even spread in age ranges, and a relatively even completion of the different measures on the website. This could be because the advertisements aligned with the website content, or that these participants were more interested in knowing different aspects of their mental wellbeing.

The participants from the “mental health” advertisement set had significantly worse outcomes on most of the mental health measures compared to the other participants. It appeared that advertising for “worried about mental health?” attracted participants who were more distressed and stressed, and had lower wellbeing and strength. Those recruited from the “mental fitness” campaign (“how fit are you mentally?”) had comparatively better outcomes on these measures. Meanwhile, participants from the “resilience” advertisements had relatively lower distress and the “strength” participants had higher strength scores. This shows that even within the same study, different advertisement content has the potential to bias the sample of participants recruited. The clinical characteristics of the participants varied according to the advertisement they saw and clicked on. Selection bias, a systematic difference between those individuals participating in the study and those who do not, results in a sample that is not representative of the target population. This may or may not be an issue for the generalizability of the study depending on the topic and sampling frame for each study. For instance, it may not be suitable to use Facebook advertising to target certain under-represented online populations or for prevalence research. Additionally, studies of online surveys or interventions often create variations of Facebook advertisements with different wording and images to find which is the most effective (indeed this is encouraged by Facebook), yet few studies report full details of the advertisements (Amon et al., 2014). Further, participants recruited from these different advertisements are treated as one homogenous group in the analyses, yet here we have shown that they can differ quite substantially. Researchers recruiting participants online need to be mindful of the content of the advertisements and the potential for biasing the sample. It is recommended that studies conduct sensitivity analyses of the results in differentially recruited samples.

Although recruitment via Facebook offers many advantages, researchers need to be mindful of its limitations and sources of selection bias. First, certain groups of people are not well represented on the Internet, such as elderly people, people from low socio-economic backgrounds, and lower education. Indeed, even when there is wider access to the Internet, research suggests there is a growing gap between those who can effectively use the Internet for information and knowledge and those who cannot (Wei and Hindman, 2011). Not all those with Internet access use Facebook and other social media sites. There is a social media divide among users and those who have less computer use autonomy, who have reservations about social media, and are limited in social ties (Bobkowski and Smith, 2013). Research suggests that Facebook users tend to be more extraverted and narcissistic than non-users (Ryan and Xenos, 2011). Among those with Facebook accounts, it is unclear how the automatic targeting functioning works, how often Facebook updates the underlying algorithm, and who sees the advertisements (Thornton et al., 2016). Only a proportion of users who see the advertisements will then go on to click on it. Most potential participants will drop-out before completing screeners or committing to engage in the intervention (Pedersen and Kurz, 2016). In our study, 19% to 76% of people who clicked on the respective Facebook advertisement sets consented to participate in the study. Unsurprisingly, after all these filters, the findings of this study show that the remaining self-selected participants differed in their demographics, mental health characteristics, and engagement in the study depending on the advertisement content that attracted them. With these limitations in mind, Facebook advertising still offers efficient and unique access to hard-to-reach populations. It is recommended that researchers carefully consider the pros and cons of Facebook recruitment in the context of their study, as with any traditional or online recruitment strategy.

Finally, our study found that younger adults reported better sleep than middle-aged adults. This is unsurprising as studies have found insomnia is associated with older age (Bin et al., 2012). However, the sleep measure was not validated and the internal consistency in the current sample was low, so this result should be interpreted with caution.

This study has several other limitations. First, the content of the advertisements was the main variable of interest. The advertisement sets had different images, and we were unable to test the impact of these specific images on recruitment rate or engagement. It may be possible that the “strength” advertisements had the most clicks because the images associated were most attractive to men who saw the advertisements. Also, although the images were selected by a user experience specialist, it is possible that some of the images did not correspond well with the wording. However, we attempted to mitigate the impact of the images on the attractiveness of the advertisement sets by including a few relevant images for each set and overlapping some of the images between the sets, yet Facebook's advertising algorithm still promotes competition of images within the advertisement sets. Nonetheless, the analyses examined the impact of the advertisement set as a whole rather than specific advertisements, but future research may also investigate the effect of different image styles. Second, the wording of the advertisement sets were chosen as variations of presenting mental health research to men. These terms may not apply to women, although it was noted that the “mental health” advertisements targeting men appeared to also recruit a few women. Third, the relatively small sample size recruited from the “resilience” and “happiness” advertisements may have masked any significant findings. Fourth, we had few measures of demographics, and thus could only look at a couple of aspects of potential selection bias.

Finally, the black-box nature of the Facebook algorithm presents limitations to the interpretation of the results. Given Facebook does not provide data on the demographics of users the advertisements were shown to, it was not possible to evaluate the differences between people who saw the advertisements, those who clicked on the advertisements, and those who continued to participate in the study, and thus understand how this selection bias arose. Further, it was not possible to determine whether the advertisement sets were randomly shown to users within the target audience. It may be possible that a particular advertisement set was biased towards being shown to particular groups within the target audience, resulting in the observed between-group differences. It may also be possible the Facebook algorithm allowed users to be shown several versions of the advertisements. Facebook users may click on the advertisement after seeing several different versions of the advertisements because of other reasons than the advertisement attracted them. In addition, given the way Facebook advertisement sets with similar target audiences compete with one another, and advertisements within each set also compete against each other, it is possible that early successes in certain advertisements may have led to some of the between-group differences. Although this may have been mitigated by the equal fixed budgets for each advertisement set as initially successful advertisement sets may no longer be shown later in the recruitment period, given these limitations, the results should be interpreted with caution.

5. Conclusions

Our study demonstrated that using different advertisement content on Facebook can lead to different recruitment rates and engagement, and it was possible to introduce selection bias to a general mental health study. Apart from trying to improve the cost-effectiveness of Facebook advertisements, it is crucial that researchers consider the study design and target population when developing the content of the advertisements. We also recommend that researchers consider reporting the advertisement content in the methods or supplementary material such that generalisability can be assessed.

The following is the supplementary data related to this article.

Facebook advertisements used in the respective advertisement sets.

Conflict of interest

The authors confirm that there are no known conflicts of interest associated with this publication including any financial, personal or other relationships with other people or organizations within three years of beginning the submitted work that could inappropriately influence, or be perceived to influence this work.

Acknowledgements

This study was developed in partnership with beyondblue with donations from the Movember Foundation. RAC is funded by an Australian Research Council Future Fellowship (FT140100824). The authors confirm that there are no known conflicts of interest associated with this publication.

References

- Amon K.L., Campbell A.J., Hawke C., Steinbeck K. Facebook as a recruitment tool for adolescent health research: a systematic review. Acad. Pediatr. 2014;14:439–447. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2014.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews C. Social media recruitment: the opportunities and challenges social media provides in the realm of subject recruitment. Appl. Clin. Trials. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Antoun C., Zhang C., Conrad F.G., Schober M.F. Comparisons of online recruitment strategies for convenience samples: Craigslist, Google AdWords, Facebook, and Amazon Mechanical Turk. Field Methods. 2016;28:231–246. [Google Scholar]

- Baltar F., Brunet I. Social research 2.0: virtual snowball sampling method using Facebook. Internet Res. 2012;22:57–74. [Google Scholar]

- Batterham P.J. Recruitment of mental health survey participants using Internet advertising: content, characteristics and cost effectiveness. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2014;23:184–191. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batterham P.J., Calear A.L., Sunderland M., Carragher N., Brewer J.L. Online screening and feedback to increase help-seeking for mental health problems: population-based randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Psychiatry Open. 2016;2:67–73. doi: 10.1192/bjpo.bp.115.001552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bin Y.S., Marshall N.S., Glozier N. The burden of insomnia on individual function and healthcare consumption in Australia. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health. 2012;36:462–468. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2012.00845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobkowski P., Smith J. Social media divide: characteristics of emerging adults who do not use social network websites. Media Cult. Soc. 2013;35:771–781. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Sills L., Stein M.B. Psychometric analysis and refinement of the Connor–Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC): validation of a 10-item measure of resilience. J. Trauma. Stress. 2007;20:1019–1028. doi: 10.1002/jts.20271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S., Kamarck T., Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983;24:385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis L.A., Mccabe K.L., Rahilly K.A., Nicholas M.A., Davenport T.A., Burns J.M., Hickie I.B. Encouraging young men's participation in mental health research and treatment: perspectives in our technological age. Clin. Investig. 2014;4:881–888. [Google Scholar]

- Facebook Dealing with overlapping audiences [Online] 2017. https://www.facebook.com/business/help/1679591828938781 Available: (Accessed 17 January 2017)

- Facebook My ads are similar. Why are they performing differently? [Online] 2017. https://www.facebook.com/business/help/112141358874214?helpref=uf_permalink Available: (Accessed 17 January 2017)

- Fenner Y., Garland S.M., Moore E.E., Jayasinghe Y., Fletcher A., Tabrizi S.N., Gunasekaran B., Wark J.D. Web-based recruiting for health research using a social networking site: an exploratory study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2012;14 doi: 10.2196/jmir.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa T.A., Kessler R.C., Slade T., Andrews G. The performance of the K6 and K10 screening scales for psychological distress in the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Well-Being. Psychol. Med. 2003;33:357–362. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R., Andrews G., Colpe L., Hiripi E., Mroczek D., Normand S.L., Walters E., Zaslavsky A. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol. Med. 2002;32:959–976. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane T.S., Armin J., Gordon J.S. Online recruitment methods for web-based and mobile health studies: a review of the literature. J. Med. Internet Res. 2015;17 doi: 10.2196/jmir.4359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindner P., Nyström M.B.T., Hassmén P., Andersson G., Carlbring P. Who seeks ICBT for depression and how do they get there? Effects of recruitment source on patient demographics and clinical characteristics. Internet Interv. 2015;2:221–225. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez O., Wu E., Shultz A.Z., Capote J., López Rios J., Sandfort T., Manusov J., Ovejero H., Carballo-Dieguez A., Chavez Baray S., Moya E., López Matos J., Delacruz J.J., Remien R.H., Rhodes S.D. Still a hard-to-reach population? Using social media to recruit Latino gay couples for an HIV intervention adaptation study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014;16 doi: 10.2196/jmir.3311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson E.J., Hughes J., Oakes J.M., Pankow J.S., Kulasingam S.L. Estimation of geographic variation in human Papillomavirus vaccine uptake in men and women: an online survey using Facebook recruitment. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014;16 doi: 10.2196/jmir.3506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen E.R., Kurz J. Using Facebook for health-related research study recruitment and program delivery. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2016;9:38–43. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramo D.E., Prochaska J.J. Broad reach and targeted recruitment using Facebook for an online survey of young adult substance use. J. Med. Internet Res. 2012;14 doi: 10.2196/jmir.1878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramo D.E., Rodriguez T.M.S., Chavez K., Sommer M.J., Prochaska J.J. Facebook recruitment of young adult smokers for a cessation trial: methods, metrics, and lessons learned. Internet Interv. 2014;1:58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan T., Xenos S. Who uses Facebook? An investigation into the relationship between the Big Five, shyness, narcissism, loneliness, and Facebook usage. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011;27:1658–1664. [Google Scholar]

- Sleep Health Foundation Sleep needs across the lifespan [Online] 2015. http://www.sleephealthfoundation.org.au/files/pdfs/Sleep-Needs-Across-Lifespan.pdf Available: (Accessed 15 September 2016)

- Smith B.W., Dalen J., Wiggins K., Tooley E., Christopher P., Bernard J. The brief resilience scale: assessing the ability to bounce back. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2008;15:194–200. doi: 10.1080/10705500802222972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton L., Batterham P.J., Fassnacht D.B., Kay-Lambkin F., Calear A.L., Hunt S. Recruiting for health, medical or psychosocial research using Facebook: systematic review. Internet Interv. 2016;4:72–81. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei L., Hindman D.B. Does the digital divide matter more? Comparing the effects of new media and old media use on the education-based knowledge gap. Mass Commun. Soc. 2011;14:216–235. [Google Scholar]

- Woodall A., Morgan C., Sloan C., Howard L. Barriers to participation in mental health research: are there specific gender, ethnicity and age related barriers? BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:1–10. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-10-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . Target 12. E60246. WHO; Geneva: 1998. Use of well-being measures in primary health care - the DepCare project health for all. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Facebook advertisements used in the respective advertisement sets.