Abstract

Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) is a leading cause of the Global Burden of Disease. Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) is an effective treatment for MDD, but access can be impaired due to numerous barriers. Internet-delivered CBT (iCBT) can be utilised to overcome treatment barriers and is an effective treatment for depression, but has never been compared to bibliotherapy. This Randomised Controlled Trial (RCT) included participants meeting diagnostic criteria for MDD (n = 270) being randomised to either: iCBT (n = 61), a CBT self-help book (bCBT) (n = 77), a meditation self-help book (bMED) (n = 64) or wait-list control (WLC) (n = 68). The primary outcome was the Patient Health Questionnaire 9-item scale (PHQ-9) at 12-weeks (post-treatment). All three active interventions were significantly more effective than WLC in reducing depression at post-treatment, but there were no significant differences between the groups. All three interventions led to large within-group reductions in PHQ-9 scores at post-treatment (g = 0.88–1.69), which were maintained at 3-month follow-up, although there was some evidence of relapse in the bMED group (within-group g [post to follow-up] = 0.09–1.04). Self-help based interventions could be beneficial in treating depression, however vigilance needs to be applied when selecting from the range of materials available. Replication of this study with a larger sample is required.

Keywords: Depression, Internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy, Bibliotherapy

Highlights

-

•

Depression is prevalent with access to treatment impaired by numerous factors.

-

•

This novel RCT compared guided internet-delivered CBT with an unguided CBT book and an unguided meditation book.

-

•

All three interventions were more effective in reducing depression than wait-list control at post-treatment.

-

•

No significant differences existed between the intervention groups at post-treatment.

-

•

Self-help treatments could be utilised for depression treatment but vigilance and monitoring needs to be applied.

1. Introduction

Depressive Disorders – including Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) – are a global public health concern and a leading cause of disease burden (Ferrari et al., 2013), with burgeoning individual and societal costs (Ustun et al., 2004). Recent NICE (2009) guidelines recommend non-drug interventions such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) as a first line treatment for mild to moderate depression (www.nice.org.uk/CG90), but dissemination of CBT can be limited due to inadequate resources (Shapiro et al., 2003), particularly in certain geographical locations (Cavanagh, 2014). To address these treatment barriers, there has been a recent surge in innovative ways to deliver CBT (Andersson et al., 2012), specifically in the development of more accessible internet and computerised therapies for the treatment of common mental disorders (Marks et al., 2003).

Internet-delivered CBT (iCBT) programs are based on face-to-face CBT treatment manuals, and typically deliver psycho-education and the key CBT skills (e.g., cognitive restructuring, behavioural activation) via lessons or modules, supplemented with homework activities and practical exercises to complete between lessons. The concept of ‘guided iCBT’ typically takes the form of a therapist or coach supporting the patient throughout the course; this is a distinct difference to unguided iCBT which takes place without support - a purely ‘self-help’ format. Although unguided iCBT programs exist, recent findings indicate that guided iCBT is a more effective treatment for depression (Johansson and Andersson, 2012). Indeed, ‘technician-assisted ‘guidance (whereby a technician provides support and encouragement to patients and responds to general questions about the course) has been shown to be equally as effective as ‘clinician-assisted’ guidance provided by a qualified clinical psychologist (Titov et al., 2010).

The main strengths of iCBT include its accessibility to large amounts of people (Andersson, 2006), the privacy and convenience it invokes for the user (Wootton et al., 2011), and the ability to offer immediate feedback (Andersson et al., 2005). This treatment modality is also scalable, with the scope to be utilised within a stepped-care framework (Andrews and Williams, 2015). ICBT is cost-effective (Hedman et al., 2012) with a recent meta-analysis revealing that guided iCBT and face-to-face CBT produced equivalent overall effects in treating depression (g = 0.05 (95% CI: − 0.19 to 0.30) (Andersson et al., 2014). Although the majority of randomised trials have found positive effects of internet and computerised CBT on depression, there are some exceptions. A recent study found that guided computerised CBT did not achieve better outcomes for people with depression compared to usual (GP) care alone (Gilbody et al., 2015), although there are some concerns with the probity of the REEACT trial (Andrews et al., 2016).

The stages in CBT for depression can be generalised and represented in manuals and ‘self-help’ books. Bibliotherapy - including self-help books - are commonly used to teach self-help tools and strategies (Den Boer et al., 2004), with their usefulness to treat depression - when compared to controls - largely supported (Gregory et al., 2004). However as numerous self-help books are widely available for depression - whereby a specific self-help program is presented and is typically worked through independently - the evidence-base to support them is relatively small (McKendree-Smith et al., 2003), making their impact difficult to establish.

It is not known whether guided iCBT represents an advance in efficacy over the numerous CBT self-help books widely available for treating depression. This question is especially pertinent in an increasingly digital age; however access to the internet is not completely ubiquitous, especially for those on lower incomes (Cline and Haynes, 2001) and those living in rural and remote areas where internet access can be limited. Therefore the first aim of the current study was to compare an evidence-based guided iCBT course (Perini et al., 2009), the ‘Sadness’ program, versus unguided access to a self-help book based on CBT for depression. Participants in the CBT self-help book group were provided with a leading self-help book free of charge, ‘Beating the Blues’ (Tanner and Ball, 2012), which they completed without any form of guidance.

We also compared these two interventions to a third group who received a self-help meditation book, ‘Silence your Mind’ (Manocha, 2013). The self-help meditation book was also unguided and served as an active comparison condition to control for the effects of assessment, monitoring, and active learning and skills practice. We aimed to explore whether there were any significant differences between these active intervention groups at post-treatment. A variety of meditation-based interventions for depression are currently available; given that meditation can result in reduced psychological stress (Goyal et al., 2014), and has shown to be beneficial in treating acute and sub-acute depression (Jain et al., 2015), we expected the meditation book to have some advantageous effects on depression symptoms and to outperform a waiting list control group, but we anticipated that both CBT groups would outperform the meditation book in reducing depression. To our knowledge, this is the first study to compare guided iCBT with two self-help books, one book based on CBT and one based on meditation, for the treatment of MDD.

2. Method

2.1. Design

The current study utilised a randomised controlled trial design to compare an iCBT program, a CBT self-help book, a meditation self-help book, to a wait-list control for participants meeting diagnostic criteria for MDD. Participants were assessed at pre-treatment, mid-treatment, post-treatment and at 3 months post-treatment.

2.2. Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were: (i) aged over 18 years (ii) prepared to provide contact details of their General Practitioner (iii) had access to internet and printer, (iv) resident in Australia, (v) fluent in written and spoken English, (vi) a score between 5 and 23 on the Patient Health Questionnaire 9-item scale (PHQ-9), (vii) met criteria on the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview Version 5.0.0 (MINI) (Sheehan et al., 1998) for DSM-IV criteria for MDD on structured telephone diagnostic interview, (vii) if taking medications for anxiety or depression, were on a stable dose for at least 8 weeks at time of intake interview, and (viii) had not commenced face to face CBT within 4 weeks at time of intake interview. Exclusion Criteria included psychosis or bipolar disorder, drug or alcohol dependency, benzodiazepine use, severe depression PHQ-9 total scores > 24, or current suicidality.

2.3. Procedure

Participants were recruited via the Virtual Clinic (www.virtualclinic.org.au), the research arm of the Clinical Research Unit for Anxiety and Depression, based at St Vincent's Hospital, Sydney and the University of New South Wales. Potential applicants viewed advertisements in the form of leaflets and posters and on social media. Applicants completed online screening questionnaires about demographic information and depressive symptoms as assessed on the PHQ-9 (Kroenke et al., 2001), after reading details about the study. Participants who met online screening criteria then participated in a brief telephone interview. Trained interviewers administered a structured diagnostic interview which consisted of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview Version 5.0.0 (MINI) (Sheehan et al., 1998) MDD and risk assessment modules to confirm whether applicants met for DSM-IV criteria for MDD. Full risk assessment modules (where necessary) were completed by a psychiatry registrar to assess suicidal ideation and determine suitability for the study.

2.4. Participant flow

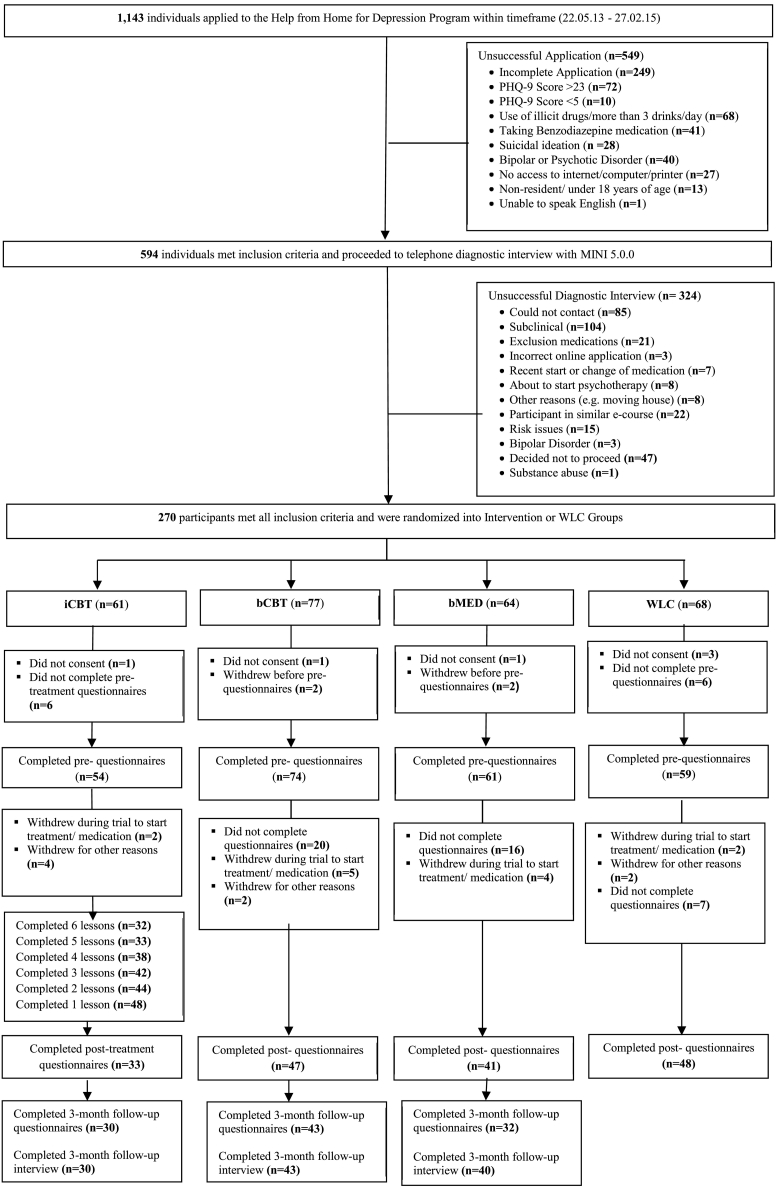

Details of the participant flow are displayed in Fig. 1. A total of 1143 applicants applied online for the study between May 2013 and February 2015. Of these, 549 applicants were excluded after completing initial online screening questions and received an email with information about alternative services. Five hundred and ninety four applicants passed the online screening phase and were telephoned for a diagnostic interview. A further 324 individuals were excluded at telephone interview stage, leaving 270 applicants who met inclusion criteria and were randomised.

Fig. 1.

Participant flow diagram.

Eligible participants were randomised based on a random number sequence generated at www.random.org by an independent person not involved in the study. Group allocation numbers were concealed from the interviewer with the use of opaque sealed envelopes, which were opened once the applicant was deemed eligible to participate. Participants provided electronic informed consent before being enrolled in the study. This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC/13/SVH/29) of St Vincent's Hospital Sydney, Australia. The trial was prospectively registered on ANZCTR (ACTRN12613000502730).

2.5. Interventions

2.5.1. Sadness program (iCBT)

The Sadness program was delivered through www.virtualclinic.org.au. The program has been evaluated in four previous trials and its efficacy has been established (Perini et al., 2008, Perini et al., 2009, Titov et al., 2010, Watts et al., 2013) (between-groups effect sizes: d = 0.8–1.3, within-group pre-post effect sizes: d = 0.9–1.0). The program consisted of 6 online lessons completed over a 12 week period and participants were instructed to complete one lesson every 1–2 weeks of the program. It follows an illustrated story, with a main character who learns how to manage her depressive symptoms using CBT skills. The program content delivers evidence-based CBT including psycho-education, cognitive restructuring, graded exposure, problem solving, effective communication and relapse prevention, with downloadable weekly homework documents (PDF) containing practical tasks to implement between lessons as well as extra resources and patient ‘recovery stories’ to read. The course content is presented in Table 5. All participants in the iCBT program received regular automatic and manual email communication to notify them that a lesson was available and encouragement to complete the lesson. Participants were contacted via email or telephone by research staff (‘The Technician’, JS) after the first two lessons, then as requested, or by a clinician (psychiatry registrar) in response to an increase in distress or suicidal intent.

Table 5.

Lesson content and homework activities in the ‘Sadness’ program (iCBT).

| Lesson title | Lesson content | Homework activities |

|---|---|---|

| Lesson 1: The diagnosis |

|

|

| Lesson 2: Monitoring your thoughts and activities |

|

|

| Lesson 3: Learning to improve your activities and thoughts |

|

|

| Lesson 4: Facing Fears |

|

|

| Lesson 5: Being assertive |

|

|

| Lesson 6: Preventing relapse and getting even better |

|

|

| Extra resources: Frequently asked questions (FAQs), 100 Things To Do (pleasant activity planning ideas), In Case of Emergency, Good Sleep Guide, Structured Problem Solving, About Assertiveness |

Worksheets (Extra Resources): Activity Planning & Monitoring Worksheet, Activity Planning Worksheet, Daily Positives Hunt Worksheet, Thought Challenging Worksheet, Structured Problem Solving Worksheet, Facing Fears Worksheet, Conversation Skills |

2.5.2. Beating the Blues (bCBT) (Tanner and Ball, 2012)

This is a self-help book designed to help people overcome depression and was posted to participants in this group, along with a short (one page) welcome letter from the book authors introducing participants to the concept of cognitive therapy and advising them to tackle the issues presented in the book systematically and one at a time. Participants were asked to work through each of the 12 chapters over 12 weeks and advised to read roughly one chapter per week. The book is self-guiding; the content is based on CBT and organised into various parts, including: Understanding Depression, Our Thinking Habits, Looking After Your Needs and Living with Someone Who is Depressed. The course content is presented in Table 6. Questionnaires and reminders to complete questionnaires were emailed to participants in this group with clinical contact occurring only if a participant reported active suicidal intent. In cases of elevated or increased distress response scores, participants were emailed to advise them where to gain additional support - including telephone counselling numbers, visiting their general practitioner or Emergency Services. No guidance or encouragement was offered.

Table 6.

Chapter content and activities to complete in ‘Beating the Blues’ (bCBT).

| Chapter title | Chapter content | Tasks to complete |

|---|---|---|

| Chapter 1: Understanding depression |

|

|

| Chapter 2: What makes people vulnerable to depression |

|

|

| Chapter 3: How you think your way into feeling down |

|

|

| Chapter 4: Breaking the lethargy circuit |

|

|

| Chapter 5: Our thinking habits: The good, the bad and the ugly |

|

|

| Chapter 6: Changing old thinking habits: the secret to being a happier person |

|

|

| Chapter 7: Are you fully awake? Cultivating mindful awareness |

|

|

| Chapter 8: Boosting your self-esteem |

|

|

| Chapter 9: Overcoming loneliness and jealousy |

|

|

| Chapter 10: Dealing with self-harm, hopelessness and suicidal urges |

|

|

| Chapter 11: Looking after your needs |

|

|

| Chapter 12: Living with someone who is depressed: A chapter for family + friends |

|

2.5.3. Silence your mind (bMED) (Manocha, 2013)

This is a self-help book aimed at teaching people to meditate and was posted to participants in this group, along with an instructional DVD, information booklet and a brief (two page) letter from the author introducing participants to the mediation technique described in the book and advising them to practice the technique for at least 10 min per day. Participants were asked to work through each of the 13 chapters over 12 weeks and advised to read roughly one chapter per week. The book is self-guiding; the content is based on a meditative approach called Mental Silence and is organised into various parts, including: What is Meditation, Meditation is Mental Silence, Health, Wellbeing and the non-mind, Helping our Young People, Flow and Optimal Being, and The Brain in Meditation. The course content is presented in Table 7. Questionnaires and reminders to complete questionnaires were emailed to participants in this group with clinical contact only occurring if a participant reported active suicidal intent. In cases of elevated or increased distress response scores, participants were emailed to advise them where to gain additional support - including telephone counselling numbers, visiting their general practitioner or Emergency Services. No guidance or encouragement was offered.

Table 7.

Chapter content and activities to complete in ‘Silence your Mind’ (bMED).

| Chapter title | Chapter content | Tasks to complete |

|---|---|---|

| Chapter 1: The ants |

|

|

| Chapter 2: The path to research |

|

|

| Chapter 3: Defining Meditation |

|

|

| Chapter 4: Specific effects – understanding the evidence |

|

|

| Chapter 5: Mental silence – a unique discovery |

|

|

| Chapter 6: The ancient paradigm |

|

|

| Chapter 7: A thought experiment that ends in silence |

|

|

| Chapter 8: Stress – the noise in the mind |

|

|

| Chapter 9: Beyond the mind-body connection |

|

|

| Chapter 10: Young minds |

|

|

| Chapter 11: Meditation in the class room |

|

|

| Chapter 12: Meditation and flow |

|

|

| Chapter 13: Brain, mind and non-mind |

|

|

2.5.4. Wait-list control group (WLC)

Participants randomised to the wait-list control (WLC) were able to continue with any course of treatment already specified at intake interview but were withdrawn from the study if they commenced a new treatment during the course of the 12 week waiting period, for example starting psychotherapy or medication for anxiety or depression. Questionnaires and reminders to complete questionnaires were emailed to participants in this group with clinical contact occurring in cases of elevated or increased distress response scores or when a participant reported suicidal intent. Participants had the choice of enrolling in either iCBT or one of the two self-books once their 12 week waiting period had ceased and they had completed all questionnaires.

2.6. Clinician contact

All participants completing the iCBT course received email and/or phone contact with the technician after the first two lessons to answer any questions about the program and to encourage them with the remainder of the course, then as requested. In cases of increased distress, particularly elevated distress and or suicidal intent was reported, the clinician made contact with the participant. Participants in the bCBT and bMED groups with elevated distress were emailed to inform them that their distress was elevated and where to get appropriate external support. The clinician did make contact with participants in these groups who reported suicidal intent.

2.7. Measures

2.7.1. Diagnostic status

The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview Version 5.0.0 (MINI (Sheehan et al., 1998)) MDD and risk assessment modules were administered at intake, and then again at 3 month follow-up for the intervention group participants (assessors were not blinded to the intervention condition).

2.7.2. Primary outcome measure

The Patient Health Questionnaire – 9 (PHQ-9, (Kroenke et al., 2001) is a 9-item self-report scale that was used to assesses DSM-IV criteria for MDD. Participants were asked to rate the frequency of symptoms (including frequency of suicidal ideation with the question “thoughts that you would be better off dead, or of hurting yourself in some way”), over the past two weeks. The scale range is: 0 = not at all, 1 = several days, 2 = more than half of the days and 3 = nearly every day, with total scores ranging from 0 to 27. The PHQ-9 has shown to have excellent reliability and validity (0.86; (Kroenke et al., 2001).

2.7.3. Secondary outcome measures

The Kessler-10 Psychological Distress Scale (K10; (Kessler et al., 2002) is a 10-item self-report scale that was used to measure non-specific psychological distress over the past two weeks. Rated on a 5-point scale, higher scores indicate higher distress levels. The K10 has excellent psychometric properties (Furukawa et al., 2003).

The Generalised Anxiety Disorder 7- item scale (GAD-7; (Spitzer et al., 2006)) was used to measure generalised anxiety disorder symptoms over the past two weeks on the same 4-point scale as the PHQ-9. Scores range from 0 to 21, and this scale has good reliability and validity (0.83; (Spitzer et al., 2006).

The NEO-Five Factor Inventory - Neuroticism Subscale (NEO-FFI, (Costa and McCrae, 1985)) is a 5-point self-report scale which was used to measure the personality dimension of Neuroticism and has good psychometric properties (Cuijpers et al., 2005).

2.7.4. Expectancy of benefit and patient satisfaction

Prior to the start of their respective intervention, participants in iCBT, bCBT and bMED were asked to provide a treatment expectancy rating. Participants were asked to provide a rating ranging from 1 to 9 about how logical the therapy offered to them seemed, and how successful they thought the treatment will be in reducing their symptoms of depression (where 1 = not at all, 5 = somewhat, and 9 = very). To examine treatment satisfaction, participants were asked at post-treatment i) how satisfied they were that the program taught them the skills to manage depression and ii) their confidence in recommending the program to a friend with similar problems (range: 1 = not at all, 5 = somewhat, and 9 = very).

2.8. Outcome measurement

At baseline, participants provided basic demographic details (e.g., age, marital status, gender, employment and educational history), depression history and treatment, and current comorbid physical illnesses (6 questions from the 2007 National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing (Teesson et al., 2011).

All four groups completed outcome measures at baseline, mid-point (Lesson 4 for iCBT and week 6 for the book groups and WLC), post-treatment (one week after Lesson 6 for iCBT or at the end of the 12 weeks for the book groups and WLC) and at 3-month follow-up (for iCBT and the book groups only). The iCBT group completed the K10 before commencing every lesson.

2.9. Power calculations

Prior to commencement of the trial, a power calculation was conducted to set the minimum sample size needed. At 0.8 power (alpha = 0.05), 100 participants per group were needed to have the power to detect a 0.4 effect size difference in efficacy between groups. However, due to unanticipated difficulties with recruitment during the time-period set out for the study, the final sample (N = 270) fell short of the sample size needed (N = 400).

2.10. Statistical analyses

Groups were compared at baseline using t-tests and chi square analyses where the data consisted of categorical data. To explore the impact of the treatment groups on outcome, linear mixed models were conducted separately for each of the dependent variable measures with time, treatment group, and the time by group interaction entered as fixed factors in the model. For each group, planned contrasts were used to compare changes within and between-groups from baseline to post-treatment and 3-month follow-up. Between-group effect sizes using the pooled standard deviation and adjusted for sample size (Hedges g) were calculated to compare between groups at post-treatment and 3-month follow-up. Within-group effect sizes (Hedges g) were calculated between pre- and post-treatment and between pre- and 3-month follow-up for each of the intervention groups.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline demographics and between-groups differences

Two hundred and forty-eight participants completed baseline questionnaires and were included in the data analysis. For baseline demographics and sample characteristics see Table 1. There was no significant difference between the groups in age, F (50,197) = 1.09, p > 0.05), or pre-treatment PHQ-9 (F (22,225) = 0.452, p > 0.05), GAD-7 (F (19,183) = 0.768, p > 0.05), K-10 (F (28,219) = 1.41, p > 0.05), or NEO (F (25,225) = 1.35, p > 0.05) scores. Chi-square analyses demonstrated that there were no between-group differences in any other demographic characteristics including gender, marital status, educational status or employment status (ps > 0.05).

Table 1.

Baseline Demographics and Sample Characteristics for the iCBT, bCBT, bMED and WLC Groups.

| iCBT Group |

bCBT Group |

bMED Group |

WLC Group |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

n = 54 |

n = 74 |

n = 61 |

n = 59 |

|||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Age (years) | 42.50 | 12.63 | 41.38 | 13.01 | 38.08 | 13.21 | 37.59 | 13.29 |

| N | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 8 | 14.8% | 12 | 16.2% | 10 | 16.4% | 15 | 25.4% |

| Female | 46 | 85.2% | 62 | 83.8% | 51 | 83.6% | 44 | 74.6% |

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Single/not or never married | 20 | 37.0% | 25 | 33.8% | 19 | 31.1% | 20 | 33.9% |

| Married/de-facto | 26 | 48.2% | 30 | 40.5% | 33 | 54.1% | 25 | 42.3% |

| Divorced/separated | 8 | 14.9% | 17 | 23.0% | 8 | 13.1% | 13 | 22.1% |

| Widowed | 0 | 0% | 2 | 2.7% | 1 | 1.6% | 1 | 1.7% |

| Educational status | ||||||||

| Masters or doctoral degree | 10 | 18.5% | 6 | 8.1% | 3 | 4.9% | 2 | 3.4% |

| Bachelor's degree | 16 | 29.6% | 19 | 25.7% | 21 | 34.4% | 24 | 40.7% |

| Diploma | 6 | 11.1% | 5 | 6.8% | 5 | 8.2% | 4 | 6.8% |

| Technicians/other Certificate | 12 | 22.2% | 15 | 20.3% | 13 | 21.4% | 10 | 17.0% |

| Trade certificate/apprentice | 2 | 3.7% | 3 | 4.1% | 2 | 3.3% | 3 | 5.1% |

| Year 10/12 certification | 8 | 14.9% | 23 | 31.1% | 17 | 27.9% | 15 | 25.4% |

| No qualification | 0 | 0% | 3 | 4.1% | 0 | 0% | 1 | 1.7% |

| Employment Status | ||||||||

| Full-time paid work | 10 | 18.5% | 23 | 31.1% | 23 | 37.7% | 19 | 32.2% |

| Part-time paid work | 17 | 31.5% | 17 | 23% | 17 | 27.9% | 19 | 32.2% |

| Unemployed | 7 | 13% | 11 | 14.9% | 4 | 6.6% | 5 | 8.5% |

| Student | 7 | 13% | 8 | 10.8% | 6 | 9.8% | 5 | 8.5% |

| Stay at home parent | 5 | 9.3% | 4 | 5.4% | 6 | 9.8% | 5 | 8.5% |

| Retired | 4 | 7.4% | 4 | 5.4% | 3 | 4.9% | 3 | 5.1% |

| Registered sick/disabled | 3 | 5.6% | 4 | 5.4% | 1 | 1.6% | 2 | 3.4% |

| Missing data | 1 | 1.9% | 3 | 4.1% | 1 | 1.6% | 1 | 1.7% |

| Current medication (at interview) | 24 | 44.4% | 37 | 50.0% | 20 | 32.8% | 28 | 47.5% |

| Current medication (class) | ||||||||

| SSRI | 11 | 20.4% | 20 | 27.0% | 9 | 14.8% | 14 | 23.7% |

| SNRI | 6 | 11.1% | 14 | 18.9% | 9 | 14.8% | 13 | 22.0% |

| Other | 7 | 31.2% | 3 | 4.2% | 2 | 3.2% | 1 | 1.7% |

| Current CBT (at interview) | 2 | 3.7% | 6 | 8.1% | 7 | 11.5% | 6 | 10.2% |

| Other psychosocial therapy | 1 | 1.9% | 1 | 1.4% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 1.7% |

| Age of first depressive episode (2 weeks or more) | ||||||||

| Under 12 years | 8 | 14.8% | 12 | 16.2% | 5 | 8.2% | 10 | 16.9% |

| 13–21 years | 23 | 42.6% | 38 | 51.4% | 37 | 60.7% | 29 | 49.2% |

| 22 years or older | 23 | 42.6% | 24 | 32.4% | 19 | 31.1% | 20 | 33.9% |

| Number of past depressive episodes | ||||||||

| 1–2 spells | 7 | 13% | 6 | 8.1% | 7 | 11.5% | 10 | 16.9% |

| 3–4 spells | 8 | 14.8% | 15 | 20.3% | 18 | 29.5% | 18 | 30.5% |

| 5–8 spells | 16 | 29.6% | 20 | 27.0% | 11 | 18.0% | 9 | 15.3% |

| > 8 | 23 | 42.6% | 33 | 44.6% | 25 | 41.0% | 22 | 37.3% |

Note. Except where noted, values refer to number and percentage scores. Educational Status = highest level of education received. M = mean, SD = standard deviation. iCBT = internet cognitive behaviour therapy; bCBT = cognitive behaviour therapy self-help book; bMED = meditation self-help book; WLC = wait-list control. * = significant between-groups difference at p < 0.05 level.

3.2. Adherence

In the iCBT group, 32 of the 54 participants completed all 6 lessons resulting in a 59% adherence rate. Of the 54 participants, 33 participants completed post-treatment assessments (61%) and 30 participants completed 3-month follow-up assessments (56%). In the bCBT group, 47 of the 74 participants provided post-treatment assessments (64%) and 43 completed 3-month follow-up assessments (58%). In the bMED group, 41 of the 61 participants provided post-treatment assessments (67%) and 32 completed 3-month follow-up assessments (52%). In the WLC group, 48 of the 59 participants provided complete data at the post-treatment time point (81%). (See Fig. 1 for participant flow). A total of 30/54 participants in the iCBT group (56%), 43/74 participants in the bCBT group (58%), and 40/61 participants in the bMED group (66%), completed a diagnostic interview to assess for MDD at 3-month follow-up.

3.3. Expectancy of benefit

There were no significant between-group differences in treatment expectancy ratings, either logical ((F (2186) = 1.57, p > 0.05); iCBT: M = 5.81, SD = 2.10; bCBT: M = 6.41, SD = 2.11; bMED: M = 6.39, SD = 5.69) or successful ((F (2186) = 1.84, p > 0.05); iCBT: M = 5.28, SD = 1.65; bCBT: M = 5.85, SD = 1.77; bMED: M = 1.94, SD = 1.63). Results are reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Expectancy of benefit.

| iCBT |

bCBT |

bMED |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

n = 54 |

n = 74 |

n = 61 |

||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| How logical does this therapy seem | 5.81 | 2.10 | 6.41 | 2.11 | 6.39 | 1.94 |

| How successful in symptom reduction | 5.28 | 1.65 | 5.85 | 1.77 | 5.69 | 1.63 |

3.4. Primary and secondary outcome measures and effect sizes at post-treatment

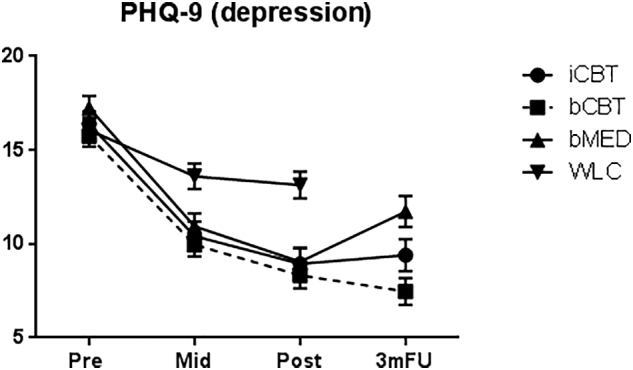

Table 3 presents the results of all groups on primary and secondary outcome measures, and see Fig. 2 for PHQ-9 graph. There were significant group by time interactions for all of the primary and secondary outcome measures (PHQ-9: F (6401.84) = 6.26, p < 0.001, K-10:F (6, 399.82) = 6.39, p < 0.001, GAD-7: F (6, 372.87) = 7.38, p < 0.001, NEO: F (6, 397.28) = 5.30, p < 0.001).

Table 3.

Estimated marginal means and within and between-groups effect sizes at post treatment for internet CBT, book CBT, meditation book and waiting list control groups.

| Baseline (T1) | Mid (T2) | Post (T3) | 3 Month FU (T4) | Within ES (95%CI) T1, T3 | Between ES (95%CI) T3 (post-treatment) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHQ-9 | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | iCBTv WLC | bCBT v WLC | bMED v WLC | iCBT v bCBT | iCBT v bMED | bCBT v bMED | |

| iCBT | 16.39 (5.03) | 10.42 (4.88) | 8.95 (4.77) | 9.41 (4.71) | 1.51 (1.00–2.00) | 0.86 (0.39–1.32)** | 0.98 (0.56–1.41)** | 0.83 (0.40–1.27)** | − 0.12 (− 0.57–0.32), ns | 0.02 (− 0.43–0.48), ns | 0.15 (− 0.56–0.27), ns |

| bCBT | 15.76 (5.03) | 9.96 (4.93) | 8.33 (4.78) | 7.47 (4.72) | 1.09 (0.70–1.48) | ||||||

| bMED | 17.26 (5.03) | 10.95 (4.93) | 9.05 (4.81) | 11.73 (4.67) | 1.55 (1.10–2.00) | ||||||

| WLC | 16.07 (5.03) | 13.60 (4.97) | 13.14 (4.91) | – | 0.50 (0.11–0.89) | ||||||

| K-10 | iCBTv WLC | bCBT v WLC | bMED v WLC | iCBT v bCBT | iCBT v bMED | bCBT v bMED | |||||

| iCBT | 33.67 (6.74) | 25.63 (6.51) | 21.98 (6.36) | 22.92 (6.28) | 1.69 (1.19–2.19) | 0.91 (0.44–1.37)** | 0.83 (0.41–1.25)** | 0.60 (0.17–1.03)** | − 0.08 (− 0.37–0.52), ns | 0.880.31 (− 0.15–0.77), ns | 0.23 (− 0.18–0.65), ns |

| bCBT | 32.26 (6.74) | 24.99 (6.60) | 22.49 (6.37) | 21.83 (6.25) | 1.47 (1.06–1.88) | ||||||

| bMED | 34.56 (6.74) | 26.06 (6.59) | 23.99 (6.42) | 26.21 (6.22) | 1.35 (0.91–1.78) | ||||||

| WLC | 32.69 (6.74) | 29.68 (6.66) | 27.93 (6.57) | – | 0.55 (0.16–0.94) | ||||||

| GAD-7 | iCBTv WLC | bCBT v WLC | bMED v WLC | iCBT v bCBT | iCBT v bMED | bCBT v bMED | |||||

| iCBT | 13.07 (4.58) | 7.14 (4.43) | 6.19 (4.32) | 6.62 (4.26) | 1.43 (0.95–1.92) | 0.73 (0.28–1.19)** | 0.77 (0.36–1.20)** | 0.55 (0.12–0.97)* | − 0.04 (− 0.49–0.40), ns | 0.18 (− 0.27–0.65), ns | − 0.23 (− 0.19–0.65), ns |

| bCBT | 12.36 (5.39) | 8.16 (4.54) | 5.98 (4.38) | 5.56 (4.33) | 1.06 (0.67–1.45) | ||||||

| bMED | 13.27 (5.31) | 8.03 (4.49) | 7.01 (4.38) | 8.11 (4.19) | 1.00 (0.58–1.42) | ||||||

| WLC | 11.86 (4.58) | 10.77 (4.53) | 9.44 (4.43) | – | 0.38 (− 0.01–0.76), ns | ||||||

| NEO | iCBTv WLC | bCBT v WLC | bMED v WLC | iCBT v bCBT | iCBT v bMED | bCBT v bMED | |||||

| iCBT | 37.59 (6.49) | 33.57 (6.26) | 30.72 (6.10) | 29.90 (6.09) | 0.94 (0.48–1.39) | 0.64 (0.18–10.9)** | 0.85 (0.43–1.27)** | 0.77 (0.35–1.21)** | − 0.21 (− 0.66–0.23), ns | − 0.14 (− 0.60–0.31), ns | 0.07 (− 0.34–0.49), ns |

| bCBT | 36.16 (6.49) | 31.50 (6.38) | 29.39 (6.11) | 27.54 (6.03) | 1.02 (0.63–1.41) | ||||||

| bMED | 36.21 (6.49) | 32.29 (6.38) | 29.83 (6.16) | 30.40 (5.95) | 0.88 (0.47–1.30) | ||||||

| WLC | 35.76 (6.49) | 34.80 (6.40) | 34.74 (6.31) | – | 0.13 (− 0.25–0.51), ns | ||||||

Note. ** p < 0.001, ns = p > 0.05. GAD-7 = Generalised Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale; iCBT = internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy group; K-10 = Kessler 10-item Psychological Distress scale; NEO = NEO-Five Factor Inventory – Neuroticism Subscale; PHQ-9 = The Patient Health Questionnaire-9, WLC = waitlist control group. Within-group ES = Hedges g; between-group ES = Hedges g with Hedges pooled SD. T1 = baseline, T2 = mid-treatment, T3 = post-treatment, T4 = 3-month follow-up. N′s T1: iCBT = 54, bCBT = 74; bMED = 61, WLC = 59; T2: iCBT = 40, bCBT = 61; bMED = 50, WLC = 53; T3: iCBT = 33, bCBT = 47; bMED = 41, WLC = 48; T4 iCBT = 30, bCBT = 43; bMED = 32.

Fig. 2.

Figure presents estimated marginal means and standard errors at baseline (pre), mid-point (week 6/Lesson 4), post-treatment and 3-month follow up (for the active interventions only). iCBT = internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy group, bCBT = self-help cognitive behavioural therapy group, bMED = self-help meditation book, WLC = wait- list control group.

There were large within-group effect sizes between baseline and post-treatment on all outcome measures in the iCBT, bCBT and bMED groups (g = 0.88–1.69). The reductions in the WLC group were moderate and significant on the PHQ-9 and K-10 (gs = 0.50–0.55), but were small and not significant on the GAD-7 (g = 0.38, 95% CI: − 0.01–0.76) and NEO (g = 0.13, 95% CI: − 0.25–0.51).

Planned pairwise comparisons showed that each of the intervention groups had significantly lower PHQ-9, K-10, GAD-7 and NEO scores relative to WLC at post-treatment (ps < 0.01). There were large between-groups effect sizes on the PHQ-9 (g's = 0.86–0.98), and on the K-10 (gs = 0.83–0.91), except for a moderate effect size between bMED and WLC on K-10 scores at post-treatment (g = 0.60). We found moderate effect sizes between the intervention groups and WLC on the GAD-7 (gs = 0.55–0.77), and moderate (iCBT v WLC: g = 0.64; bMED v WLC: g = 0.77) to large (bCBT v WLC: g = 0.85) effect size differences on the NEO.

There were no significant differences between iCBT, bCBT or bMED groups on any of the outcome measures at post-treatment (ps > 0.05). The between-groups effect sizes revealed small (but not significant) effect sizes favouring the bCBT group over the bMED group on the GAD-7 and K-10 (gs = 0.23), small but not significant effect sizes favouring iCBT over bMED on the K-10 (g = 0.31), and small but not significant effect sizes favouring bCBT over iCBT on the NEO (g = 0.21).

Of note, post-hoc power calculations indicated that at 0.8 power (α = 0.05), the actual sample size (minimum of 54 per group) had power to detect a between-groups effect size difference of d = 0.54.

3.5. Primary and secondary outcome measures and effect sizes at 3-month follow-up

To explore whether there were any between-groups differences between the iCBT, bCBT and bMED groups between post-treatment and 3-month follow-up, linear mixed-models were conducted separately for each of the dependent variable measures, with time (with post and follow-up scores entered in the model), treatment group, and the group by time interaction entered as fixed factors in the model. Results are reported in Table 4, and see Fig. 2 for PHQ-9 graph.

Table 4.

Estimated marginal means and within and between-groups effect sizes at 3-month follow-up for internet CBT, book CBT, and meditation book groups.

| Post (T3) | 3 Month FU (T4) | Within t(df) T3, T4 | Within ES (95%CI) T3, T4 | Between ES (95%CI) T4 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHQ-9 | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | iCBT v bCBT | iCBT v bMED | bCBT v bMED | ||

| iCBT | 8.70 (5.28) | 9.04 (5.20) | 0.36 (1, 100.10) | 0.06 (− 0.43–0.55) | − 0.27 (− 73–0.20), ns | 0.46 (− 0.04–0.97), ns | 0.73 (0.26–1.20)* |

| bCBT | 8.34 (5.28) | 7.62 (5.25) | 0.92 (1, 97.24) | 0.13 (− 0.29–0.54) | |||

| bMED | 8.81 (5.31) | 11.47 (5.15) | 3.02 (1, 100.21)* | 0.56 (0.09–1.04)* | |||

| K-10 | iCBT v bCBT | iCBT v bMED | bCBT v bMED | ||||

| iCBT | 21.89 (7.35) | 22.50 (7.23) | 0.49 (1, 101.46) | 0.07 (− 0.43–0.56) | − 0.10 (− 0.56–0.37), ns | 0.42 (− 0.08–0.93), ns | 0.52 (− 0.06–0.99), ns |

| bCBT | 22.16 (7.34) | 21.79 (7.21) | 0.37 (1, 98.87) | 0.05 (− 0.36–0.47) | |||

| bMED | 23.53 (7.43) | 25.60 (7.13) | 1.77 (1, 100.66) | 0.30 (− 0.16–0.77) | |||

| GAD-7 | iCBT v bCBT | iCBT v bMED | bCBT v bMED | ||||

| iCBT | 6.12 (4.60) | 6.32 (4.55) | 0.77 (1, 100.39) | 0.13 (− 0.36–0.63) | − 0.18 (− 0.64–0.29), ns | 0.49 (− 0.01–1.00), ns | − 0.68 (0.21–1.16)* |

| bCBT | 5.90 (4.66) | 5.50 (4.39) | 0.60 (1, 96.85) | 0.10 (− 0.31–0.52) | |||

| bMED | 7.06 (4.67) | 8.56 (4.47) | 2.01 (1, 99.59)* | 0.28 (− 0.19–0.74) | |||

| NEO | iCBT v bCBT | iCBT v bMED | bCBT v bMED | ||||

| iCBT | 30.26 (7.64) | 29.58 (7.61) | 0.54 (1, 102.05) | 0.07 (− 0.43–0.56) | − 0.28 (− 0.75–0.18), ns | 0.16 (− 0.33–0.66), ns | 0.45 (− 0.001–0.91), ns |

| bCBT | 29.19 (7.68) | 27.41 (7.54) | 1.71 (1, 2.94) | 0.25 (− 0.16–0.67) | |||

| bMED | 30.07 (7.75) | 30.83 (7.41) | 0.65 (1, 102.50) | 0.10 (− 0.36–0.56) | |||

Note. ** p < 0.001, * p < 0.01, ns = p > 0.05. GAD-7 = Generalised Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale; iCBT = internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy group; K-10 = Kessler 10-item Psychological Distress scale; NEO = NEO-Five Factor Inventory – Neuroticism Subscale; PHQ-9 = The Patient Health Questionnaire-9, WLC = waitlist control group. Within-group ES = Hedges g; between-group ES = Hedges g with Hedges pooled SD. T3 = post-treatment, T4 = 3-month follow-up. T3: iCBT = 33, bCBT = 47; bMED = 41, WLC = 48; T4 iCBT = 30, bCBT = 43; bMED = 32.

There was a significant group by time interaction between post-treatment and 3-month follow-up on the PHQ-9 (F (2, 99.60) = 4.19, p < 0.05). Between-group comparisons revealed that 3-month follow-up scores on the PHQ-9 were significantly higher, with moderate between-groups differences in the bMED relative to the bCBT group (g = 0.73, 95% CI: 0.26–1.20), and a trend towards higher PHQ-9 scores in the bMED compared to iCBT groups (g = 0.46, 95%CI: − 0.04–0.97, p = 0.066). Within-groups comparisons between post-treatment and follow-up revealed that the bMED experienced moderate and significant deterioration in PHQ-9 scores between post-treatment and follow-up (within-group g = 0.56, 95% CI: 0.09–1.04). The changes in PHQ-9 scores in the iCBT and bCBT groups were not significant.

The group by time interactions were not significant for the remaining variables (K-10: F (2, 100.41) = 1.24, p > 0.05, GAD-7: F (2, 99.05) = 1.84, p > 0.05, NEO: F (2, 101.60) = 1.32, p > 0.05). Within-group comparisons between post-treatment and follow-up for each group on the K-10, GAD-7, and NEO scores were not significant (ps > 0.05), although effect sizes indicated small (not significant) increases in GAD-7 (g = 0.28, 95% CI: − 0.19–0.74), and K-10 scores (g = 0.30, 95% CI: 0.16–0.77) in the bMED group, and small (but not significant) decreases in NEO scores in the bCBT group (g = 0.25, 95% CI: − 0.16–0.67).

3.6. Diagnostic status at follow-up

Of the participants that completed a 3-month follow-up telephone interview, 24/30 (80%) in the iCBT group, 34/43 (79%) in the bCBT and 30/40 (75%) in the bMED group no longer met criteria for MDD. There were no statistically significant differences in the proportion of recovered patients in the intervention groups (χ2 (4,n = 189) = 1.66, p = 0.79).

3.7. Clinical significance

Following Jacobson and Truax (1991) reliable change index (RCI) values were calculated for the PHQ-9 scores to determine the proportion of each group who evidenced reliable improvements (or deterioration) in PHQ-9 scores between baseline and follow-up. RCI values were calculated using test-retest reliability values of 0.84 from Kroenke et al. (2001). In order to calculate standard error of measurement values, standard deviations were derived from current sample (PHQ-9 pre-treatment pooled SD = 4.37). A change of 5 points on the PHQ-9 was considered to be statistically reliable change. Of the iCBT group, 21/54 (61.1%) reliably improved compared to 36/74 (48.6%) in the bCBT group, 31/61 (50.8%) in the bMED group, and 21/59 (35.6%) in the WLC group. There was no evidence of deterioration in the iCBT group, but there was evidence of deterioration on the PHQ-9 for one in the bCBT group (1.4%), one in the bMED group (1.6%), and 6 individuals in the WLC group (10.2%).

3.8. Missing data analysis

Because there was a significant proportion of missing data on the primary outcome measure (PHQ-9) at post-treatment, we analysed missing data patterns. First, Little's MCAR test was not significant for post-treatment scores (χ2 = 0.57, p = 0.45), or follow-up scores (χ2 = 1.29, p = 0.26). Second, we conducted independent samples t-tests to explore whether there were any significant differences between those with missing data versus those with complete data at post-treatment. Compared to participants who provided post-treatment data (n = 169: M = 32.73, SD = 6.18), those who had missing data were significantly more distressed at baseline on the K-10 (n = 79: M = 34.32, SD = 5.13) (t(246, = 1.99, p = 0.048), however there were no significant differences between those with and without data at post-treatment on age or other demographics (e.g., marital and education status), baseline PHQ-9 scores, GAD-7 scores, or NEO scores (ps > 0.05). There was also no statistically significant relationship between treatment group and the proportion of participants with missing data (χ2 (3) = 6.73, p = 0.08).

In addition to these analyses, a multiple imputation procedure was used to account for the data lost at post-treatment and 3-month follow-up (for the intervention groups only). We assume the value of the data lost relates to observed variables in the dataset. The multiple imputation procedure was implemented in SPSS, using a chained equations multiple imputation procedure, with five imputations. ANOVAS were conducted on imputed post-treatment and follow-up PHQ-9 data to explore whether the significant between-group differences in the main mixed models analysis remained after imputation. The pooled estimates for the imputed data for the four groups at post-treatment were: iCBT: M = 8.21, SE = 1.03, bCBT: M = 8.15, SE = 0.86, bMed: M = 8.73, SE = 0.78, WLC: M = 13.17, SE = 0.83. The between-group differences between the three intervention groups and WLC remained significant for post-treatment PHQ-9 scores (ps < 0.001), and there were no significant differences between the three intervention groups (iCBT, bCBT, bMed). In addition, mirroring the findings from the mixed models in the main analysis, there was a significant group difference on PHQ-9 scores at 3-month follow-up, with the bCBT reporting significantly lower PHQ-9 scores than the bMed group. The pooled estimates for the imputed data for the three treatment groups at follow-up were: iCBT: M = 8.92, bCBT: M = 7.78, SE = 1.21, SE = 1.39, bMed: M = 11.64, SE = 1.04.

3.9. Clinician contact

There was a significant difference across groups in the total time (minutes) spent contacting the participants (total time spent: F (3, 244) = 15.35, p < 0.001); given the iCBT group was guided, planned comparisons indicated significantly more time was spent by the technician contacting iCBT participants compared to each of the other three groups (p's < 0.001). The technician spent an average of 9.7 min (SD = 5.02, range = 3–21) emailing and calling each participant in the iCBT group during the treatment course (including follow-up period). There were no overall between-group differences in the time spent contacting the participants by the clinician (F (3, 244) = 1.84, p > 0.05). The majority of participants across all groups did not require contact with a clinician (iCBT: 81%; bCBT: 95%; bMED: 92%; WLC: 90%).

3.10. Patient satisfaction

There were no overall between-group differences in either treatment satisfaction ((F(2, 118) = 1.98, p > 0.05); iCBT: M = 6.45, SD = 1.84; bCBT: M = 6.02, SD = 2.14; bMED: M = 5.49, SD = 2.25), or confidence in recommending the program to a friend ((F(2, 118) = 1.57, p > 0.05); iCBT: M = 6.73, SD = 2.32; bCBT: M = 6.15, SD = 2.41; bMED: M = 5.71, SD = 2.62).

4. Discussion

The current study had a unique aim, to explore whether there were any post-treatment differences between unguided self-help books and guided iCBT in treating MDD. At post-treatment, all three interventions - when compared with the wait-list control group - were associated with significantly lower depressive symptoms, distress, anxiety and neuroticism. We found large between-group differences (ds = 0.83 to 0.98) between the active intervention groups compared to WLC on the PHQ-9, and medium to large differences on the secondary outcome measures (K10: ds = 0.60 to 0.91; GAD7: ds = 0.55 to 0.77; NEO: ds = 0.64 to 0.85). These findings provide support for the efficacy of all three intervention groups compared to waiting list.

Although there were no significant differences between the intervention groups at post-treatment, there were significant differences at 3-month follow-up on one outcome (the PHQ-9). Results revealed that although the meditation book was effective in reducing depressive symptoms immediately after treatment, these gains were not sustained at follow-up. In the group that received the meditation self-help book, there was evidence of worsening of symptoms on the PHQ-9 between post-treatment and 3-month follow-up, corresponding to a medium effect size (g = 0.56). In contrast, the changes in PHQ-9 scores within the iCBT and bCBT groups between post-treatment and follow-up were not significant, suggesting the improvements in these groups were maintained. We note that the relapse in symptoms in the bMED group appeared only on the self-reported depressive symptoms on the PHQ-9, and not the other outcome measures assessing anxiety, distress and disability. In addition there were no group differences in the diagnostic status of participants according to diagnostic interviews at 3-month follow up, with a high proportion of participants in all three intervention groups no longer meeting criteria for MDD at follow-up; 75% in bMED, 79% in bCBT and 80% in iCBT. We acknowledge that the group difference at follow-up was only found on the depression outcome measure (the PHQ-9), and not the other outcome measures (e.g., anxiety, distress, neuroticism) so this finding needs to be replicated before definitive conclusions can be made. However, the study outcomes provide evidence that the benefits of CBT appear to last beyond the completion of treatment, and that the longer-term benefits of self-help meditation-based interventions for treatment of depression warrant further investigation (Manocha et al., 2011).

The study findings support the notion that iCBT is a reputable treatment for depression (Hedman et al., 2012); yet, we also found strong evidence supporting the CBT self-help book, ‘Beating the Blues’. Our study results seem to replicate recent findings comparing iCBT with bibliotherapy; in spite of the scant literature available on self-help treatment books, comparisons between iCBT and bibliotherapy for OCD (Wootton et al., 2013) and for social phobia (Furmark et al., 2009) exist and showed both modes of presentation to be equivalent. However it is unknown whether the same outcomes for the self-help books would be replicated if they were delivered outside a controlled environment, or even in routine clinical practice. Participants in this trial were rigorously assessed at intake, and were instructed to read one chapter per week over a strict 12-week period. They also completed regular routine assessments throughout the study period and were closely monitored for suicidality. It is also unclear whether these results generalise to other self-help treatments for depression – specifically other self-help books – that are widely available within the public domain.

It is not known what the role – if any - individual treatment preferences (for the internet or book mode) prior to study randomisation, and any individual depression treatment history, had on final outcomes. Over a third of the sample reported frequent and episodic depression (8 + episodes). It has been suggested that people who have experienced repeated episodes of depression may gain less from internet-delivered self-help treatments (Andersson et al., 2004), although a recent meta-analysis of psychotherapies for depression in adults purported that relapse can be prevented by using CBT, particularly in those with numerous previous episodes (Cuijpers, 2017). Interestingly, only a small number of the sample were undertaking other psychotherapeutic treatments (e.g. face to face CBT) for their depression at intake assessment (10%), but a significantly larger proportion of the total sample were on stable doses of medications for anxiety or depression (44%). For many therefore, the study interventions were adjuncts to existing treatments highlighting the potential usefulness of self-help treatments for depression with concurrent (pharmocological) treatments.

The issue of clinician time spent is also of note as the majority of participants in all three intervention groups did not require any contact with a clinician throughout the duration of the trial (including follow-up stage), indicating the cost-effectiveness of the study interventions. The lack of post-treatment differences between the guided and un-guided interventions is also of note but seemingly not uncommon; in a comparison between guided and unguided internet therapy for depression, no significant effects were found highlighting the ability of internet treatments to be delivered successfully without any form of guidance (Berger et al., 2011). Furthermore, a recent study found that unguided bibliotherapy achieved similar results to an unguided iCBT and guided iCBT group for the treatment of health anxiety, and that all three treatments were significantly more effective than a control group at post-treatment (Hedman et al., 2016), mirroring the current study findings. An interesting finding of this study was that the therapist-guided iCBT group completed significantly more modules than the unguided iCBT group, supporting the association that clinician contact during the iCBT program is associated with improved adherence (Hilvert-Bruce et al., 2012).

The current results must be considered in light of limitations. First, the study was underpowered to detect significant differences between the three intervention groups, and as we conducted multiple group comparisons there is risk of Type II error. Future replications of this study with a larger sample are needed to detect these effects. A significant limitation of the study is that no post-treatment data existed for around 30% of the sample within the intervention groups; although high drop-out rates can be a common drawback of self-help trials (Eysenbach, 2005), the adherence for this research study was generally lower than expected. However this was as true for iCBT (61% completed post-treatment questionnaires), as it was for the self-help books (64% completed post-treatment questionnaires in bCBT and 58% completed post-treatment questionnaires in bMED). Some participants within the iCBT group did remark that they had issues accessing the internet as regularly as the program required.

Thirdly, the study design excluded follow-up comparison between WLC and the three intervention groups; the follow-up period was also brief (only 3 months) - the enduring beneficial outcomes of iCBT, and the long-term superiority of iCBT over WLC warrant further examination (Mahoney et al., 2014). It is of note that not all participants in the intervention groups were able to be contacted to complete the three-month follow-up diagnostic assessment, which may led to an overestimate of the effects of treatment on remission rates from MDD. A further drawback is that the researchers are not clear, due to the limited contact with these participants, on how much a participant randomised to the self-help books adhered to the content and materials presented within the treatment program of the books themselves. It has been asserted that bibliotherapy can be challenging when the reader is not able to understand the materials, which can lead to a loss of motivation and the individual giving up (Team, H. o. N. D. I. P. and Usher, 2013).

In summary, to overcome the burden of depressive disorders, accessible and effective, low-cost interventions are required, and self-help treatments (including bibliotherapy) could be utilised to address these treatment barriers. These study findings are promising; participants who met criteria for mild, moderate and severe (but not very severe) depression engaging in a CBT or meditation-based intervention had significantly reduced depressive symptoms in comparison to participants waiting for treatment at post-treatment. We do include a cautionary note however, that vigilance does need to be applied when selecting from the vast array of self-help treatments publicly available, and would strongly recommend that patients are formally assessed and properly monitored by professionals when embarking on self-help treatments for depression. Replication of this study with a larger sample is required.

Acknowledgements

Financial funding for this study was provided by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) in the form of Fellowships awarded to Jill Newby (1037787) and Alishia Williams (630746). The NHMRC had no involvement in any aspect of the study, nor the preparation of this manuscript.

References

- Andersson G. Internet-based cognitive-behavioral self help for depression. Expert. Rev. Neurother. 2006;6(11):1637–1642. doi: 10.1586/14737175.6.11.1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson G., Bergström J., Holländare F., Ekselius L., Carlbring P. Delivering cognitive behavioural therapy for mild to moderate depression via the internet: predicting outcome at 6-month follow-up. Verhaltenstherapie. 2004;14(3):185–189. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson G., Bergstrom J., Hollandare F., Carlbring P., Kaldo V., Ekselius L. Internet-based self-help for depression: randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2005;187:456–461. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.5.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson G., Paxling B., Wiwe M., Vernmark K., Felix C.B., Lundborg L., Furmark T., Cuijpers P., Carlbring P. Therapeutic alliance in guided internet-delivered cognitive behavioural treatment of depression, generalized anxiety disorder and social anxiety disorder. Behav. Res. Ther. 2012;50(9):544–550. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson G., Cuijpers P., Carlbring P., Riper H., Hedman E. Guided internet-based vs. face-to-face cognitive behavior therapy for psychiatric and somatic disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry. 2014;13(3):288–295. doi: 10.1002/wps.20151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews G., Williams A.D. Up-scaling clinician assisted internet cognitive behavioural therapy (iCBT) for depression: a model for dissemination into primary care. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2015;41:40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews G., Hobbs M.J., Newby J.M. Computerised cognitive behaviour therapy for major depression: a reply to the REEACT trial. Evid. Based Ment. Health. 2016;19(2):43–45. doi: 10.1136/eb-2015-102293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger T., Hämmerli K., Gubser N., Andersson G., Caspar F. Internet-based treatment of depression: a randomized controlled trial comparing guided with unguided self-help. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2011;40(4):251–266. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2011.616531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh K. Geographic inequity in the availability of cognitive behavioural therapy in England and Wales: a 10-year update. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2014;42(4):497–501. doi: 10.1017/S1352465813000568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cline R.J.W., Haynes K.M. Consumer health information seeking on the internet: the state of the art. Health Educ. Res. 2001;16(6):671–692. doi: 10.1093/her/16.6.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa P.T., McCrae R.R. 1985. The NEO personality inventory: Manual, form S and form R, Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers P. Four decades of outcome research on psychotherapies for adult depression: an overview of a series of meta-analyses. Can. Psychol. 2017;58(1):7–19. [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers P., van Straten A., Donker M. Personality traits of patients with mood and anxiety disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2005;133(2–3):229–237. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Den Boer P.C.A.M., Wiersma D., Van Den Bosch R.J. Why is self-help neglected in the treatment of emotional disorders? A meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 2004;34(06):959–971. doi: 10.1017/s003329170300179x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenbach G. The law of attrition. J. Med. Internet Res. 2005;7(1) doi: 10.2196/jmir.7.1.e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari A.J., Charlson F.J., Norman R.E., Patten S.B., Freedman G., Murray C.J., Vos T., Whiteford H.A. Burden of depressive disorders by country, sex, age, and year: findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. PLoS Med./Public Libr. Sci. 2013;10(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furmark T., Carlbring P., Hedman E., Sonnenstein A., Clevberger P., Bohman B., Eriksson A., Hallen A., Frykman M., Holmstrom A., Sparthan E., Tillfors M., Ihrfelt E.N., Spak M., Eriksson A., Ekselius L., Andersson G. Guided and unguided self-help for social anxiety disorder: randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2009;195(5):440–447. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.060996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa T., Kessler R., Slade T., Andrews G. The performance of the K6 and K10 screening scales for psychological distress in the Australian National Survey of mental health and well-being. Psychol. Med. 2003;33(2):357–362. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbody S., Littlewood E., Hewitt C., Brierley G., Tharmanathan P., Araya R., Barkham M., Bower P., Cooper C., Gask L., Kessler D., Lester H., Lovell K., Parry G., Richards D.A., Andersen P., Brabyn S., Knowles S., Shepherd C., Tallon D., White D. Computerised cognitive behaviour therapy (cCBT) as treatment for depression in primary care (REEACT trial): large scale pragmatic randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2015;351 doi: 10.1136/bmj.h5627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal M., Singh S., Sibinga E.M., Gould N.F., Rowland-Seymour A., Sharma R., Berger Z., Sleicher D., Maron D.D., Shihab H.M., Ranasinghe P.D., Linn S., Saha S., Bass E.B., Haythornthwaite J.A., Cramer H. Meditation programs for psychological stress and well-being: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Deut. Z. Akupunktur. 2014;57(3):26–27. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.13018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory R.J., Schwer Canning S., Lee T.W., Wise J.C. American Psychological Association; 2004. Cognitive Bibliotherapy for Depression: A Meta-analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Hedman E., Ljótsson B., Lindefors N. Cognitive behavior therapy via the Internet: a systematic review of applications, clinical efficacy and cost–effectiveness. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 2012;12(6):745–764. doi: 10.1586/erp.12.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedman E., Axelsson E., Andersson E., Lekander M., Ljótsson B. Exposure-based cognitive–behavioural therapy via the internet and as bibliotherapy for somatic symptom disorder and illness anxiety disorder: randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2016;209(5):407–413. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.116.181396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilvert-Bruce Z., Rossouw P.J., Wong N., Sunderland M., Andrews G. Adherence as a determinant of effectiveness of internet cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety and depressive disorders. Behav. Res. Ther. 2012;50(7–8):463–468. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson N.S., Truax P. Clinical significance: a statistical approach to defining meaningul change in psychotherapy research. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1991;59(1):12–19. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain F.A., Walsh R.N., Eisendrath S.J., Christensen S., Rael Cahn B. Critical analysis of the efficacy of meditation therapies for acute and subacute phase treatment of depressive disorders: a systematic review. Psychosomatics. 2015;56(2):140–152. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson R., Andersson G. Internet-based psychological treatments for depression. Expert. Rev. Neurother. 2012;12(7):861–870. doi: 10.1586/ern.12.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R., Andrews G., Colpe L., Hiripi E., Mroczek D., Normand S., Walters E., Zaslavsky A. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol. Med. 2002;32(6):959–976. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K., Spitzer R.L., Williams J.B. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney A.E., Mackenzie A., Williams A.D., Smith J., Andrews G. Internet cognitive behavioural treatment for obsessive compulsive disorder: a randomised controlled trial. Behav. Res. Ther. 2014;63:99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2014.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manocha R. Hachette Australia; 2013. Silence your mind. [Google Scholar]

- Manocha R., Black D., Sarris J., Stough C. A randomized, controlled trial of meditation for work stress, anxiety and depressed mood in full-time workers. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2011;2011 doi: 10.1155/2011/960583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks I.M., Mataix-cols D., Kenwright M., Cameron R., Hirsch S., Gega L. Pragmatic evaluation of computer-aided self-help for anxiety and depression. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2003;183(1):57–65. doi: 10.1192/bjp.183.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKendree-Smith N.L., Floyd M., Scogin F.R. Self-administered treatments for depression: a review. J. Clin. Psychol. 2003;59(3):275–288. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICE Depression: the treatment and management of depression in adults (update). NICE clinical guideline 90. 2009. www.nice.org.uk/CG90 2016, from.

- Perini S., Titov N., Andrews G. The climate sadness program of internet-based treatment for depression: a pilot study. E-J. Appl. Psychol. 2008;4(2):18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Perini S., Titov N., Andrews G. Clinician-assisted internet-based treatment is effective for depression: randomized controlled trial. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry. 2009;43(6):571–578. doi: 10.1080/00048670902873722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro D.A., Cavanagh K., Lomas H. Geographic inequity in the availability of cognitive behavioural therapy in England and Wales. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2003;31(2):185–192. doi: 10.1017/S1352465813000568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan D.V., Lecrubier Y., Sheehan K., Amorim P., Janavs J., Weiller E., Hergueta T., Baker R., Dunbar G.C. The mini-international neuropsychiatric interview (M.I.N.I): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl. 20):22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer R.L., Kroenke K., Williams J.W., Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the gad-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006;166(10):1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner S., Ball J. Susan Tanner and Jillian Ball; 2012. Beating the Blues: A Self Help Approach To Overcoming Depression. [Google Scholar]

- Team, H. o. N. D. I. P., Usher T. Bibliotherapy for depression. Aust. Fam. Physician. 2013;42(4):199–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teesson M., Mitchell P.B., Deady M., Memedovic S., Slade T., Baillie A. Affective and anxiety disorders and their relationship with chronic physical conditions in Australia: findings of the 2007 National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry. 2011;45(11):939–946. doi: 10.3109/00048674.2011.614590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titov N., Andrews G., Davies M., McIntyre K., Robinson E., Solley K. Internet treatment for depression: a randomized controlled trial comparing clinician vs. technician assistance. PLoS One. 2010;5(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ustun T.B., Ayuso-Mateos J.L., Chatterji S., Mathers C., Murray C.J. Global burden of depressive disorders in the year 2000. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2004;184:386–392. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.5.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts S., Mackenzie A., Thomas C., Griskaitis A., Mewton L., Williams A., Andrews G. CBT for depression: a pilot RCT comparing mobile phone vs. computer. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:49. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wootton B.M., Titov N., Dear B.F., Spence J., Kemp A. The acceptability of internet-based treatment and characteristics of an adult sample with obsessive compulsive disorder: an internet survey. PLoS One. 2011;6(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020548. (Jun 2011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wootton B.M., Dear B.F., Johnston L., Terides M.D., Titov N. Remote treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized controlled trial. J. Obsessive-Compulsive Relat. Disord. 2013;2(4):375–384. [Google Scholar]