Abstract

Early initiation of substance use significantly increases one's risk of developing substance use dependence and mental disorders later in life. To interrupt this trajectory, effective prevention during the adolescent period is critical. Parents play a key role in preventing substance use and related harms among adolescents and parenting interventions have been identified as critical components of effective prevention programs. Despite this, there is currently no substance use prevention program targeting both students and parents that adopts online delivery to overcome barriers to implementation and sustainability. The Climate Schools Plus (CSP) program was developed to meet this need. CSP is an online substance use prevention program for students and parents, based on the effective Climate Schools prevention program for students. This paper describes the development of the parent component of CSP including a literature review and results of a large scoping survey of parents of Australian high school students (n = 242). This paper also includes results of beta-testing of the developed program with relevant experts (n = 10), and parents of Australian high school students (n = 15). The CSP parent component consists of 1) a webinar which introduces shared rule ranking, 2) online modules and 3) summaries of student lessons. The parent program targets evidence-based modifiable factors associated with a delay in the onset of adolescent substance use and/or lower levels of adolescent substance use in the future; namely, rule-setting, monitoring, and modelling. To date, this is the first combined parent-student substance use prevention program to adopt an online delivery method.

Keywords: Development, Prevention, Adolescent, Alcohol, Parent

Highlights

-

•

Climate Schools Plus is the first combined student-parent substance use prevention program using an online delivery method

-

•

Development was informed by consultation with 242 parents: They wanted the program to be brief, self-paced and easy to use.

-

•

Participants reported the final program was relevant to parents of high school students, and 80% would recommend it to others.

1. Introduction

Substance use among adolescents is a pressing public health issue (Newton et al., 2017; Degenhardt et al., 2016) and an important concern for parents. In Australia, Western Europe and North America 60 to 95% of 15–19 year olds report using alcohol in the past year (WHO, 2016). Substance use in adolescence has been shown to be associated with increased risk for a range of negative outcomes including short- and long-term alcohol-related harms (WHO, 2014), physical harms such as road traffic accidents and other accidental injuries (Hall et al., 2016), the development of substance use disorders (Hall et al., 2016), and comorbid mental health disorders (Teesson et al., 2009). To interrupt this trajectory, and reduce these harms, effective substance use prevention during adolescence is critical (Newton et al., 2017).

Parents are key agents of adolescent socialisation, especially in the initiation and development of substance use (Ryan et al., 2010), and parenting interventions have been identified as critical components of effective substance use prevention programs in adolescence (Newton et al., 2017; Özdemir and Koutakis, 2016). Despite this, there are currently no integrated models internationally, which adopt an online approach to overcome barriers to implementation and sustainability (Newton et al., 2017). This paper describes the development of an integrated online program that combines a successful student-based universal program (Newton et al., 2009, Newton et al., 2010; Champion et al., 2016a; Newton et al., 2014; Vogl et al., 2009, Vogl et al., 2014; Teesson et al., 2017), with a newly-developed parenting component.

Universal approaches to substance use and harms prevention among adolescents have generally focused on adolescents themselves and have been found to be effective at preventing alcohol and other substance use among this population (Newton et al., 2017; Foxcroft and Tsertsvadze, 2011). The most effective programs have been found to adopt a harm-minimization framework, they are underpinned by a comprehensive social influence approach and they are able to be implemented with high fidelity (Newton et al., 2017; Faggiano et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2016).The innovative Climate Schools model for alcohol and other drug prevention is one such approach (Newton et al., 2011). The universal Climate Schools programs are delivered within the school setting to all students, regardless of level of risk, and are based on a social influence approach to prevention (Newton et al., 2011; Botvin and Griffin, 2007). The courses use cartoon storylines to engage and maintain student interest and are facilitated by the internet, ensuring high implementation fidelity. They are designed to be implemented during high school, before significant exposure to alcohol and other drug use occurs. To date, over 14,000 students from 157 schools have participated in research trials of Climate Schools courses across Australia and the United Kingdom (Newton et al., 2009, Newton et al., 2010; Champion et al., 2016a; Newton et al., 2014; Vogl et al., 2009, Vogl et al., 2014; Teesson et al., 2017). These trials found that, compared to control students who received their usual health and drug education at school, students who received the Climate Schools courses show significant improvements in alcohol- and cannabis-related knowledge, a reduction in average weekly alcohol consumption, a reduction in the frequency of binge drinking and a reduction in the frequency of cannabis use up to three years following the interventions. Despite these positive results, like most universal programs, the effect sizes found in these trials are modest (Foxcroft and Tsertsvadze, 2011; Faggiano et al., 2014; Champion et al., 2013; Hennessy and Tanner-Smith, 2015). It has been suggested that one means of achieving greater effect is to target parents alongside their adolescent children to prevent substance use (Newton et al., 2017; Kumpfer et al., 2003; Smit et al., 2008).

To address the need for an effective, evidence based, substance use prevention program involving both adolescents and their parents, we sought to develop an online parent component to accompany the existing online Climate Schools: Alcohol and Climate Schools: Alcohol & Cannabis courses for students. The combined parent-student intervention, known as the Climate Schools Plus program, is the first combined student- and parent-based substance use prevention program to be developed in an Australian context and the first combined student and parent substance use prevention program to be delivered entirely online. The development and evaluation of the student Climate Schools: Alcohol and Climate Schools: Alcohol & Cannabis courses has been described elsewhere (Newton et al., 2009, Newton et al., 2010; Champion et al., 2016a; Newton et al., 2014; Teesson et al., 2017; Newton et al., 2011). This paper describes the development of the parent component.

2. Development

The development of the Climate Schools Plus parent component was iterative and collaborative. The parent component is based on the Dutch Prevention of Alcohol Use in Students (PAS) program developed by one of the authors (IK), as well as a review of relevant evidence, consultation with parents (end-users) and an expert advisory group (eight academics and clinicians with expertise in school-based substance use prevention, substance use behaviour change and parenting interventions from the NHMRC Centre of Research Excellence in Mental Health and Substance Use, The National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, UNSW, The National Drug Research Institute, Curtin University, Western Australia, Utrecht University, The Netherlands, the School of Medicine and Public Health, and the University of Newcastle, and a lay parent representative) and feedback from beta-testing of materials and program components. These stages are described in detail below and are presented in Fig. 1. All aspects of this research were approved by the University of New South Wales Human Research Ethics Committee (HC16887).

Fig. 1.

The development process of the parent component of Climate Schools Plus.

3. Literature review

A review of the literature reporting the effectiveness of existing, combined student-and-parent prevention programs was conducted in 2016 to inform the development of the Climate Schools Plus parent component (Newton et al., 2017). The main features considered in this review were 1) the content of the program, 2) timing of intervention delivery and 3) the mode of delivery.

3.1. Content of the program

A systematic review of the literature was undertaken to identify programs that adopted a combined student- and parent-based approach to prevent and/or reduce substance use among adolescents (Newton et al., 2017). We identified 22 papers describing 10 different programs, nine of which were found to significantly delay or reduce adolescent alcohol and/or other drug use in at least one trial. Eight programs were reported to be efficacious in reducing alcohol consumption, while three reported significant reductions in cannabis use among adolescents. The majority of programs aimed to equip parents with generic parenting skills, such as parental monitoring and communication, while others included specific substance use parenting strategies, such as rule-setting. The effects of these programs were observed up to 72 months following intervention delivery; suggesting these types of combined programs can have long-lasting effects.

One of the successful combined programs identified in this review, with particularly good effect sizes, was the Dutch Prevention of Alcohol Use in Students (PAS) program (Koning et al., 2009). PAS is a brief, universal prevention program based on the theory of planned behaviour and social cognitive theory, which combines both student- and parent-based components. The PAS parenting intervention specifically targets parental rules about adolescent alcohol use, as lack of rule-setting by parents has been identified as one of the best and most easily modifiable predictors of early adolescent substance use (van der Vorst et al., 2006; McKay, 2015). In this program, parents of high school students in one-year group attend a face-to-face presentation at the beginning of the school year where they receive information about alcohol use among adolescents and the important role of parental attitudes and behaviour. Thereafter, parents are encouraged as a group, to agree upon a set of strict rules regarding alcohol use. They are provided with an information leaflet and a copy of the agreed upon rules, two weeks after the parents' meeting. Six months after the parent component of the program is delivered, students complete an online program in class that consists of four lessons, followed by a hardcopy booster lesson one year later, which aims to increase alcohol refusal skills. Compared to students in the control condition, students who received the PAS program reported a delay in the onset of alcohol use, weekly alcohol use, and heavy weekly alcohol use; as well as less alcohol consumption and heavy weekend alcohol consumption up to 50-months post baseline (Koning et al., 2009, Koning et al., 2015, Koning et al., 2013, Koning et al., 2011).

Yap et al. (2017), reviewed the literature examining modifiable parenting factors associated with adolescent alcohol initiation, later use and misuse of alcohol. Based on a comprehensive review and meta-analysis, they identified a number of key modifiable parenting factors associated with adolescent alcohol use. These factors included three risk factors (parental supply of alcohol, favourable attitudes towards alcohol and parental alcohol use) and four protective factors (parental monitoring, parent-child relationship quality, parental support and parental involvement) for which there was sound evidence of a relationship to adolescents' initiation of alcohol use and levels of later alcohol use and misuse. Parental supply of alcohol emerged as the top risk factor for adolescent alcohol use. Specifically, they found that adolescents whose parents supplied alcohol, or allowed them to drink at home, were more likely to start drinking or have alcohol related problems earlier, drink more frequently, drink at higher quantitates and have more alcohol-related problems later in life. Parental monitoring emerged as the strongest protective factor in their review, indicating that by being more aware of adolescents' activities, whereabouts and friendship networks, parents can help protect their children from later alcohol misuse and related harms. Emerging evidence demonstrated that having clear rules against adolescent alcohol use may protect against early initiation of alcohol use and that family conflict may increase this risk (Yap et al., 2017). Similarly, Kuntsche and Kuntsche (2016) conducted a systematic review of studies reporting on the implementation of parenting programs targeting the prevention of adolescent substance use behaviour. They found that successful programs all attempted to improve parental monitoring, set strict rules against underage substance use and improve parent-child communication.

While this research identified a number of important and potentially modifiable parenting factors that are associated with adolescent alcohol use in particular (see Newton et al., 2017 and Yap et al. (2017) for a detailed discussion of these findings), clear and easily available advice for parents and careers on how they can implement these recommendations is lacking (Ryan et al., 2011). Ryan et al. (2011) reviewed sources of advice for parents and identified 457 recommendations for parents to reduce their adolescent's alcohol use. A panel of 38 Australian experts then rated the importance of these recommendations to produce a comprehensive set of expert-endorsed strategies for preventing or reducing adolescent alcohol consumption, which were written into a document suitable for parents. Many of these strategies (e.g. modelling responsible drinking and attitudes towards alcohol, establishing family rules, monitoring adolescents when unsupervised, establishing and maintaining a good parent-child relationship and talking to adolescents about alcohol) are consistent with the key strategies employed in successful parent-based prevention programs and the modifiable parenting factors found to be associated with adolescent substance use in the literature (Newton et al., 2017; Yap et al., 2017; Kuntsche and Kuntsche, 2016). Other strategies endorsed by the expert panel included: things parents should know about adolescent alcohol use; delaying adolescents' introduction to alcohol, preparing adolescents for peer pressure, unsupervised adolescent drinking, what to do when an adolescent has been drinking without parental permission and hosting adolescent parties. Information from these reviews (Newton et al., 2017; Yap et al., 2017; Kuntsche and Kuntsche, 2016), guidelines (Ryan et al., 2011), and the PAS program (Koning et al., 2009, Koning et al., 2015, Koning et al., 2013, Koning et al., 2011) informed the content of the Climate Schools Plus parent program.

3.2. Timing of the Intervention

Research indicates that intervening early in adolescence, before exposure to alcohol and cannabis has occurred, is optimal for delaying uptake and preventing harmful use (Botvin and Griffin, 2007; Briere et al., 2011; McBride, 2003). Results from the most recent National Drug Strategy Household Survey show that in 2016 in Australia, the average age of alcohol initiation was 16.3 years of age (Year 10/11) (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2016). This suggests that intervening in the early years of high school is optimal. In line with this, other research has demonstrated that interventions involving parents are most likely to be effective when implemented earlier, rather than later, in adolescence (Onrust et al., 2016). Taken together, these results suggest that early adolescence is the ideal time to deliver a prevention program for both adolescents and their parents.

The Climate Schools: Alcohol and Cannabis student course consists of the 6 lesson Climate Schools: Alcohol module and the 6 lesson Climate Schools: Alcohol and Cannabis module. In the past, both modules were delivered in Year 8 of high school when students are approximately 13–14 years of age. However, teacher feedback collected as part of the most recent evaluation of Climate Schools (Teesson et al., 2014), indicated that teacher and student burden would be reduced if the 6-lesson Alcohol and Cannabis module were to be delivered in Year 9, rather than Year 8. This also aligns with a later age of initiation of cannabis use (18.7) in Australia (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2016). Moreover, for the purposes of a combined parent and student program, this allows for a booster module to be delivered to parents one year after delivery of the initial parent program. Booster sessions have been shown to be associated with increased effectiveness among student (Midford et al., 2002; Midford et al., 2001; Rossmanith, 2006), parent-based (Kuntsche and Kuntsche, 2016; Doumas et al., 2013; Koutakis et al., 2008) and combined (Newton et al., 2017) substance use prevention programs.

3.3. Delivery of the program

Much of the literature describing parent-based interventions to prevent substance use among adolescents has identified parent recruitment and engagement as key barriers to success (Newton et al., 2017; Connell et al., 2007; Malmberg et al., 2015; Malmberg et al., 2014; Riesch et al., 2012; Shortt et al., 2007; Toumbourou et al., 2013). A review conducted by Newton et al. (2017) found that across 22 research papers describing 10 different combined parent and student interventions, uptake by parents was low and the suggested barriers to sufficient engagement among parents included lack of time, high costs, childcare and transport issues. The review also identified that online delivery methods have the potential to address many of these barriers and increase uptake and engagement with these types of interventions among parents.

In addition to improving accessibility and potentially increasing parent uptake, online delivery offers a number of advantages over traditional face-to-face prevention programs. Firstly, online programs can typically be implemented with a higher degree of fidelity, as program content is standardized and cannot be adapted or changed (Pankratz et al., 2006). Secondly, online programs foster higher user engagement through the creation of an interactive environment (Bennett and Glasgow, 2009). Finally, online programs are less labour intensive for schools to implement, as trained professionals are not required for their delivery. Koning and ter Bogt (2015) identified that a key challenge in achieving wide implementation of the PAS program has been practical limitations of a small team of prevention workers visiting several schools at the start of each school year. Internet delivery overcomes many resource limitations posed by face-to-face interventions; offering greater sustainability and significantly enhancing potential for translation and widespread implementation (Champion et al., 2016b).

Despite the many advantages to an online delivery method, our recent systematic review (Newton et al., 2017) did not identify an existing combined intervention for students and parents that was delivered online. This review suggests that integrating online evidence-based parent components with online evidence-based student components has the potential to improve prevention outcomes for students as well as improve the quality of implementation, fidelity, accessibility, scalability and sustainability.

4. End-user consultation: Scoping survey

Scoping research with the target audience (i.e., parents of high school-aged children) was conducted to inform the development of the Climate Schools parent program and ensure program acceptability and relevance. Research was approved by the University of New South Wales Human Research Ethics Committee (HC16887).

4.1. Recruitment and participants

Participants were recruited online via paid and unpaid advertisements and were accepted into the study if they had at least one child attending an Australian high school. In total, 242 parents (95.5% female) completed the survey. The survey did not invite co-parents to complete the survey. Most parents were employed either full- (42.1%), or part-time/casual (39.3%). Most parents were residents of major cities (54.6%), but many were from inner (21.2%) and outer (20.6%) regional areas in Australia, with 2.1% from remote, and 1.5% from very remote Australia (‘remote’ is defined as areas greater than 5.93 km and less than 10.53 kms from a service centre; ‘very remote’ is defined as areas at least 10.53 km to a service centre (ABS, 2013). All parents had at least one child in high school and some respondents had multiple children in different school years; 21.3% had a child in Year 7, 26.0% had a child in Year 8, 31.0% had a child in Year 9, 27.9% had a child in Year 10, 26.9% had a child in Year 11 and 24.9% had a child in Year 12. Six percent of parents indicated they were of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander origin and 5% indicated they spoke a language other than English at home. Parents who completed the survey went in a draw to win an iPad.

4.2. Procedure and measures

Participants completed a 29-question online survey that contained both multiple choice, 5-point Likert scale and open-ended responses. Participants were surveyed on their use of technology (e.g., “How often do you use the internet?”) and their preferences for, and willingness to engage with, an online substance use prevention program (e.g., “How long would you be happy to spend using an online parenting program about preventing alcohol and cannabis use in adolescence?”). Questions from the Australian Parental Supply of Alcohol Longitudinal study (APSAL; Aiken et al., 2017) were adapted to survey parents on their rules, expectations and confidence in addressing adolescent substance use (e.g., parents selected on a 5-point scale from “Never” to “Always” how often their adolescent is allowed to “…drink alcohol at home when we are around”). A copy of the full questionnaire is available on request.

4.3. Results

Almost all (97.1%) participants used the internet multiple times a day and were equipped with a ‘smartphone’ (98.3%). In line with this, most parents wanted to access a parenting program about preventing substance use online; either via their school's online portal/website (36%), a mobile application ‘app’ (53.3%), email (50.4%) or a downloadable resource booklet (33.1%); only 18% of parents indicated wanting access to a printed booklet, and 3.7% did not want to access a parenting program at all.

A majority of parents reported it is very/extremely important that a parenting program be interactive (62.4%), self-paced (89.7%), and brief (88.5%); with most parents (52.9%) wanting to spend under 10-min per week on a substance use prevention program. Almost all parents indicated it is very/extremely important that a parenting program contain evidenced-based information (97.9%) and be designed by a reputable institution (89.0%). Most parents were interested in an online program with the following features: fact sheets (83.9%), on-demand webinar (72.7%), cartoon vignette scenarios (66.5%), automatic emails of summaries of student lessons (76.0%) and short video summaries of online materials (64.9%).

Parents generally endorsed strict rules around alcohol use, with most reporting that they never allowed their adolescent (under 15 years) to drink when parents are not around (97.5%), to drink more than one glass at home with parents (94.6%), to drink as much as they like outside the home (96.3%), to drink with friends at a party (93.0%), to come home drunk (96.3%), to become drunk when out with friends (96.7%), to drink alcohol on weekends (89.3%) or to drink alcohol during the week (95.5%). While parents reported being strict in rule setting, open-response feedback exposed specific challenges in implementing alcohol-related rules; in particular, the idea that parents acting in isolation from each other set different rules and expectations around alcohol use (see Table 1 for examples). It is worth noting that a substantial minority (18%) indicated they would ‘rarely’ allow their adolescent to drink alcohol at home with a parent present. This was in line with permissive attitudes towards parental supply of alcohol and supervised drinking, which was communicated in open responses (see Table 2 for examples). Finally, despite parents reporting strict rules around alcohol use, only 19% of parents were confident that they could definitely stop their child from becoming drunk.

Table 1.

Parents' feedback on difficulties setting and implementing rules around adolescent alcohol use.

| Parent feedback | Examples |

|---|---|

| Teen drinking is unavoidable | “[I] Just fear that consumption of drugs and alcohol are so normalised among Australian teenagers, that there is little I can do to protect my teenager.” |

| Other parent's/family's rules make it difficult to implement rules | “I am concerned that there are a lot of parents that seem quite relaxed about drinking. This then puts pressure on other parents to also be relaxed. I do not want my child to be excluded from activities however I generally do not feel confident with or trust other parent's rules. Too often parents are trying to be friends with their children rather than parents.” “Not all parents are on the same page which makes rules hard to enforce.” “From past experience with my two elder children and their friends it would appear there is a lax attitude towards underage drinking among both their peers and their parents.” “There is a growing acceptance of alcohol use in young people which puts pressure on parents that do not wish their child to drink.” |

| Setting strict rules could be harmful | “I worry that totally banning the consumption of alcohol could potentially make it more desirable” “I feel it is challenging to set rules around drinking and yet make it clear that you will always come and help if called.” |

Table 2.

Parents' permissive attitudes towards supply of alcohol to adolescents and drinking at home.

| Parent feedback | Examples |

|---|---|

| Rare sips of alcohol are okay | “Small sips or tastes are allowed in my house for non-spirit alcohols.” “When we allow alcohol, it is a sip or half a glass at special occasions. It is not common.” |

| A glass of alcohol at dinner is okay/beneficial | “The European culture is so different from our own ‘binge’ drinking culture. Their children will often consume a small glass of wine with dinner. I find this attitude extremely healthy and educated” |

| Supervised drinking or drinking at home is safe, or educational | “I would prefer my teenagers know how alcohol affects them in a safe environment at home rather than drinking behind our backs.” “[I] allow [my] child to try drinking under supervision so they understand the effects and how they handle being intoxicated” |

5. Content and technical design

The design and initial content of the Climate Schools parent program was informed by the review of the literature and the PAS parent intervention, as well as the scoping survey described above. The parent program was designed to be delivered entirely online via a responsive website specifically optimized for smartphone use, but that also allowed it to be effectively accessed via any device. It consisted of three key parts:

-

1.

A webinar to introduce parents to key evidence-based strategies to prevent alcohol and cannabis use and harms among adolescents and to facilitate generation of a shared set of rules about alcohol and cannabis use for their children;

-

2.

Online modules that deliver key information for parents about the prevalence and harms of adolescent alcohol and cannabis use, practical evidence-based tips for preventing use and harms; and

-

3.

Parent lesson summaries of the material covered in the Climate Schools: Alcohol and Climate Schools: Alcohol and Cannabis courses for students.

5.1. Webinar

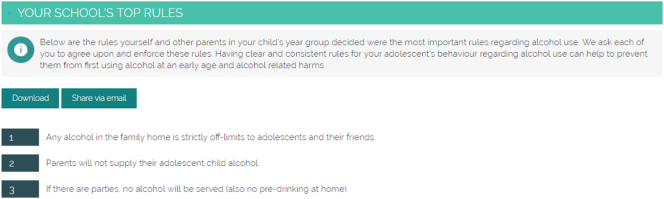

The webinar component of the program was adapted for an online setting from Koning's effective universal prevention program, PAS, in which parents receive a face-to-face presentation highlighting the importance of parental attitudes and behaviours with respect to alcohol and agree to a shared set of rules around adolescent alcohol use (Koning et al., 2009, Koning et al., 2015, Koning et al., 2013, Koning et al., 2011). In Climate Schools Plus, two 8-min, on-demand webinar presentations are made available to parents prior to students receiving the student program in schools. The first webinar focuses on alcohol use and is delivered when children of the parents involved are aged 13–14 years (Year 8 of secondary school in Australia), while the second webinar focuses on alcohol and cannabis use, and is delivered when the children are aged 14–15 years (Year 9 of secondary school in Australia). The webinars introduce the parent program; address key information about adolescent substance use and highlight, along with other modifiable parenting factors, the importance of strict rule-setting to prevent adolescent substance use (see Fig. 2). At the start of the school year, parents of students within an individual year group at a school are invited to log in to the Climate Schools Plus website (see Fig. 3), watch the on-demand webinar and rank, according to perceived importance, a list of five rules regarding adolescent substance use (generated from our review of the literature). The rule-ranking component is interactive and can be done at any time during the first 4 weeks of the program (see Fig. 4). The selections of parents are used to automatically generate a list of three rules considered to be most important by that group of parents, at that school. All parents are then asked to agree on this set of rules for their children. At the end of the 4 week rule-ranking period, all parents are automatically emailed the agreed rules to share with their partner, or other caregivers for their child, and these final rules are available to view, share and download on the Climate Schools Plus website.

Fig. 2.

Demonstrative screenshot of the webinar.

Fig. 3.

Climate Schools Plus parent component homepage.

Fig. 4.

Demonstrative screenshot of a school's list of alcohol-related rules.

5.2. Online Modules

The online module component consists of four brief, interactive modules addressing adolescent alcohol use which are made available to parents when their child is 13–14 years of age (Year 8). A booster module regarding alcohol use, and two additional modules regarding cannabis use are made available when children are aged 14–15 years (Year 9). The content of each of the modules is based on the existing literature, reviewed above and aims to both reinforce the active components of the PAS program and directly address key parenting factors found to be associated with adolescent substance use (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Module content.

| Module description | Target parent factors | |

|---|---|---|

| Year 8 |

|

↑ Alcohol-specific communication ↓ Favourable attitudes towards alcohol |

|

↑ Rule setting about alcohol ↑ Parental monitoring ↓ Favourable attitudes towards alcohol |

|

|

↑ Parental modelling of responsible alcohol use ↓ Parental supply of alcohol ↓ Parental alcohol use |

|

|

↑ Parental involvement ↑ General communication quality ↑ Alcohol-specific communication |

|

| Year 9 |

|

↑ Alcohol-specific communication ↑ Rule setting about alcohol ↑ Parental monitoring ↑ Parental modelling of responsible alcohol use ↑ Parental involvement ↓ Parental alcohol use ↓ Favourable attitudes towards alcohol ↓ Parental supply of alcohol |

|

↑ Cannabis-specific communication ↓ Favourable attitudes towards cannabis |

|

|

↑ Parental monitoring ↑ Parental involvement ↑ Cannabis-specific communication ↓ Favourable attitudes towards cannabis |

Based on our scoping research with parents, each module was designed to be brief, engaging and interactive. Each module begins with a clear statement of what is to be covered, why it is important and provides a link to relevant evidence. Modules were developed so that parents could explore key content in 10 min or less, with content delivered in a variety of interactive and engaging ways, including the use of expandable lists, ‘choose your own adventure’ vignettes, interactive images, quizzes and cartoons. Additionally, the online layout of modules was designed to allow some parents to quickly navigate the material and take away the core messages, while allowing others to delve more deeply into the content (see Fig. 5 for demonstrative screen shots).

Fig. 5.

Demonstrative screenshots of module content.

To ensure the educational and clinical validity of the modules, expert advisory group members were approached to review the information and content of the initial written module content. At least two expert reviewers reviewed the initial content of each module to assess readability, applicability and accuracy with respect to current research and behaviour change techniques. Changes made to the content as a result of this review process included: minor language changes to make the content more acceptable to parents and to clarify key points; the inclusion of more practical examples of how parents could implement recommendations made; and adding some additional content (e.g., the addition of information regarding “vaping” in the modules addressing cannabis use).

5.3. Parent summaries of student lessons

The content addressed in of each of the student lessons delivered to adolescents as a part of the Climate Schools: Alcohol and Cannabis course was summarized to produce the parent lesson summaries and reviewed by a parent member of the expert advisory group. These summaries teach parents about the prevalence, patterns of use, and short- and long-term effects of alcohol and cannabis use, which map on to the student program. The summaries are automatically emailed to parents each week, while their children complete the students' lessons during class. They are also available to view, share and download on the Climate Schools Plus website.

6. End-user consultation: Beta-testing

A beta-version of the Climate Schools Plus parent program was developed and reviewed by the expert advisory group described above, for usefulness and usability. Parents who completed the scoping survey were re-contacted and invited to provide feedback on the developed program. Research was approved by the University of New South Wales Human Research Ethics Committee (HC16887).

6.1. Recruitment and participants

15 parents of Australian high school students, and 10 relevant experts (79.2% female), registered for the Climate Schools Plus parent website and were asked to spend 3-min looking at the website and 5–10-min completing a designated module (randomly allocated), in detail. Participants were then asked a series of questions about the graphics, layout, usefulness and relevance of the program. These questions also included the Systems Usability Scale (SUS) (Brooke, 1996).

6.2. Results

Participants found the program to be attractive, with 83% of participants reporting that they liked/strongly liked the layout of the modules, and most found the module graphics appropriate (87.5%) and engaging (87.5%). All participants (100%), agreed/strongly agreed that the content is relevant to parents of high school students and most (80%), would recommend it to other parents. Similarly, 92% of participants reported that the information in the module they reviewed was informative; with the same number of participants reporting the information is appropriate.

CSP received an average score of 77.1 on the SUS (Brooke, 1996),which translates to an adjective rating between ‘good’ and ‘excellent’(Bangor et al., 2009). These positive evaluations of the CSP program were reflected in the open-ended comments left by participants:

Module was easy to read and complete. Very straightforward and to the point information. – Parent.

Very easy to follow, and engaging – Parent.

Easy to navigate. Uses neutral and non-judgemental tones – Parent.

I think it flows easily and simple straight forward advice without too much detail which could “bog people down” – Expert.

I like the use of cartoons and speech bubbles. I think that the information is conveyed simply and there is not too much text on the page. – Expert.

Participants also provided useful suggestions for the improvement of the program including: increasing the font size; adding instructions and extra navigability; reducing the amount of text used and adding more graphics. These suggestions were implemented in the final version of the program.

7. Timing of the combined intervention

The Climate Schools Plus: Parent Program was designed to be delivered in tandem with the Climate Schools: Alcohol and Climate Schools Alcohol and Cannabis student programs. As can be seen in Fig. 6, in the first week of the intervention students and parents register for the program and parents are invited to view the webinar, participate in interactive rule ranking and explore the modules. In week 2, students begin the Climate Schools programs in class and parents are emails summaries of the lessons they complete each week. Parents are able to participate in the interactive rule ranking between weeks 1 and 4 of the intervention, with the final set of agreed upon rules emailed to parents in week 5. The webinar and modules in the parent program are available for parents to complete at any time throughout the following school year. The same timeline is followed when participating students are in both year 8 and year 9.

Fig. 6.

Intervention timeline.

8. Discussion

The aim of the current paper was to describe the formative research and development process of the parenting component of the Climate Schools Plus program. This program was developed to address the need for an effective, evidence-based substance use prevention program, involving both adolescents and their parents (Newton et al., 2017; Özdemir and Koutakis, 2016; Onrust et al., 2016).

A review of the literature identified evidenced-based intervention targets; an effective model of a combined parent-student intervention, PAS (Koning et al., 2009); and highlighted the advantage of delivering the intervention online, as a method of overcoming a number of key barriers to parental uptake and engagement, as encountered in previous trials (Newton et al., 2017). Parent consultation highlighted the need for a parent-based substance use prevention program and provided insights into the desired features of such a program. Parents indicated the need for a brief, online program that was evidence-based and practical. They expressed concerns about their own confidence to prevent their children from becoming drunk and despite many parents reporting that they set strict rules around adolescent alcohol use, a substantial minority of parents reported more permissive behaviours regarding adolescent alcohol use, expressing a desire to teach adolescents how to drink ‘safely’ in a supervised environment. This finding is concerning given the wealth of research demonstrating that parental supply of alcohol and supervised drinking at home is associated with risky drinking and other alcohol-related harms (Yap et al., 2017; McMorris et al., 2011; Roebroek and Koning, 2016; Vorst et al., 2010; Mattick et al., 2018). Barriers to setting and implementing rules around alcohol use included concerns about other parents having different rules and expectations to their own.

A limitation of the consultation process was the low level of male participation (3.7%), despite attempts to increase male recruitment rates (including re-advertising for the survey targeting “fathers” specifically) and it is unclear why this occurred. Consequently, the feedback from the scoping survey may not be as relevant to fathers accessing the program in the future. A more concerning inference of the low male participation is that fathers may be unlikely to participate in the intervention. This would be consistent with the low-level of father participation in parenting interventions for behavioural and emotional problems (Sanders et al., 2010) and obesity (Morgan et al., 2017). While it is unclear whether father involvement is necessary for intervention success, some studies have reported that fathers' drinking is influential in determining adolescent and later-life drinking (Poelen et al., 2009; Seljamo et al., 2006) and may be especially influential for their sons' drinking (Wickrama et al., 1999). To increase father engagement, the Climate Schools Plus program communicates the importance of involving all caregivers in prevention and includes a “share” feature so that parents can easily email/message the intervention text and activities to their co-parent.

The Climate Schools Plus parent component has been informed by evidence and is brief, engaging and interactive. Each of the program components (webinar, modules and lesson summaries) are accessible on a web-responsive site and able to be accessed across mobile devices. The content development process was iterative and collaborative, with input from experts (academics and clinicians with expertise in school-based substance use prevention, substance use behavioural change and parenting interventions) reviewing content at each stage of development. It has been designed so that it requires no additional work from school staff to implement, beyond making parents aware of the program and providing them with the website's access details. All emails sent to parents throughout the intervention are sent automatically via the website and the webinar is pre-recorded, meaning the parent component is a sustainable add-on to the existing Climate Schools student programs.

The next step is to conduct a randomized controlled trial to test the feasibility, acceptability and efficacy of Climate Schools Plus in reducing adolescent alcohol and cannabis related harms. This will be the first trial, internationally, of an integrated online intervention for students and parents to prevent alcohol and cannabis use. If found to be effective, the parent component of Climate Schools Plus will be made available alongside the existing student lessons via the Climate Schools website, allowing for widespread implementation. This evidence-based intervention has the potential to provide a sustainable and scalable improvement to the wellbeing of young Australians and to reduce the substantial costs associated with substance use.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

This study is funded by the Australian Government Department of Health, and a Society for Mental Health Research Early Career Research Award to NN. This study was also funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) through a NHMRC Centre of Research Excellence (APP1041129).

Declaration of interest

MT and NN are two of the developers on the Climate Schools student program in Australia, which is distributed not for profit. IK led the development and evaluation of the combined Prevention of Alcohol use in Students (PAS) program. She derives no financial income from the PAS intervention. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- ABS . Canberra; Australian Bureau of Statistics: 2013. Remoteness Structure. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken A. Cohort profile: the Australian parental supply of alcohol longitudinal study (APSALS) Int. J. Epidemiol. 2017;46(2) doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . AIHW; Canberra: 2017. National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2016: detailed findings. (Drug Statistics series no. 31. PHE 214). [Google Scholar]

- Bangor A., Miller J., Kortum P. Determining what individual SUS scores mean: adding an adjective rating scale. J. Usability Stud. 2009;4(3):114–123. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett G.G., Glasgow R.E. The delivery of public health interventions via the internet: actualizing their potential. Annu. Rev. Public Health. 2009;30:273–292. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.031308.100235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botvin G.J., Griffin K.W. School-based programmes to prevent alcohol, tobacco and other drug use. Int. Rev. Psychiatry. 2007;19(6):607–615. doi: 10.1080/09540260701797753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briere F. Predictors and consequences of simultaneous alcohol and cannabis use in adolescents. Addict. Behav. 2011;36(7):785–788. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooke J. SUS: a 'quick and dirty' usbability scale. In: Jordan B.T. Patrick W., McClelland Ian Lyall, Weerdmeester Bernard., editors. Usability Evaluation in Industry. CRC Press; 1996. pp. 189–194. [Google Scholar]

- Champion K.E. A systematic review of school-based alcohol and other drug prevention programs facilitated by computers of the internet. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2013;32 doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2012.00517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champion K.E. A cross-validation trial of an internet-based prevention program for alcohol and cannabis: preliminary results from a cluster randomised controlled trial. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry. 2016;50(1):64–73. doi: 10.1177/0004867415577435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champion K.E., Newton N.C., Teesson M. Prevention of alcohol and other drug use and related harm in the digital age: what does the evidence tell us? Curr. Opin. Psychiatry. 2016;29(4):242–249. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell A.M. An adaptive approach to family intervention: linking engagement in family-centered intervention to reductions in adolescent problem behavior. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2007;75(4):568–579. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.4.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L. The increasing global health priority of substance use in young people. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(3):251–264. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00508-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doumas D.M. A randomized trial evaluating a parent based intervention to reduce college drinking. J. Subst. Abus. Treat. 2013;45(1):31–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faggiano F. Universal school-based prevention for illicit drug use. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014;(12) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003020.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foxcroft D.R., Tsertsvadze A. Universal school-based prevention programs for alcohol misuse in young people. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011;5:CD009113. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall W.D. Why young people's substance use matters for global health. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(3):265–279. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)00013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy E.A., Tanner-Smith E.E. Effectiveness of brief school-based interventions for adolescents: a meta-analysis of alcohol use prevention programs. Prev. Sci. 2015;16(3):463–474. doi: 10.1007/s11121-014-0512-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koning I.M., ter Bogt T. Unfinished business or, why is it so difficult to implement an evidence-based alcohol-use intervention program? Subst. Use Misuse. 2015;50(8–9):1131–1133. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2015.1010895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koning I.M. Preventing heavy alcohol use in adolescents (PAS): cluster randomized trial of a parent and student intervention offered separately and simultaneously. Addiction. 2009;104(10):1669–1678. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koning I.M. Long-term effects of a parent and student intervention on alcohol use in adolescents: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2011;40(5):541–547. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koning I.M. A cluster randomized trial on the effects of a parent and student intervention on alcohol use in adolescents four years after baseline; no evidence of catching-up behavior. Addict. Behav. 2013;38(4):2032–2039. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koning I.M. Effects of a combined parent–student alcohol prevention program on intermediate factors and adolescents' drinking behavior: a sequential mediation model. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2015;83(4):719. doi: 10.1037/a0039197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koutakis N., Stattin H., Kerr M. Reducing youth alcohol drinking through a parent-targeted intervention: the Orebro prevention program. Addiction. 2008;103(10):1629–1637. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumpfer K.L., Alvarado R., Whiteside H.O. Family-based interventions for substance use and misuse prevention. Subst. Use Misuse. 2003;38(11−13):1759–1787. doi: 10.1081/ja-120024240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche S., Kuntsche E. Parent-based interventions for preventing or reducing adolescent substance use - a systematic literature review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2016;45:89–101. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee N.K. What works in school-based alcohol education: a systematic review. Health Educ. J. 2016;75(7):780–798. [Google Scholar]

- Malmberg M. Effectiveness of the 'Healthy School and Drugs' prevention programme on adolescents' substance use: a randomized clustered trial. Addiction. 2014;109(6):1031–1040. doi: 10.1111/add.12526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmberg M. Substance use outcomes in the healthy school and drugs program: results from a latent growth curve approach. Addict. Behav. 2015;42:194–202. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattick R.P. Association of parental supply of alcohol with adolescent drinking, alcohol-related harms, and alcohol use disorder symptoms: a Prospective Cohort Study. Lancet Public Health. 2018;3(2):e64–e71. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30240-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride N. A systematic review of school drug education. Health Educ. Res. 2003;18 doi: 10.1093/her/cyf050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay M.T. Parental rules, parent and peer attachment, and adolescent drinking behaviors. Subst. Use Misuse. 2015;50(2):184–188. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2014.962053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMorris B.J. Influence of family factors and supervised alcohol use on adolescent alcohol use and harms: similarities between youth in different alcohol policy contexts. J. Stud. Alcohol Durgs Suppl. 2011;72(3):418–428. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midford R., Snow P., Lenton S. Centre fo Youth Drug Studies, Australian Drug Foundation; Melbourne: 2001. School-based Illicit Drug Education Programs: A Critical Review and Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Midford R. Principles that underpin effective school-based drug education. J. Drug Educ. 2002;32(4):363–386. doi: 10.2190/T66J-YDBX-J256-J8T9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan P.J. Involvement of fathers in pediatric obesity treatment and prevention trials: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2017;139(2) doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton N.C. Delivering prevention for alcohol and cannabis using the internet: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Prev. Med. 2009;48 doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton N.C. Internet-based prevention for alcohol and cannabis use: final results of the climate schools course. Addiction. 2010;105 doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton N.C. Developing the climate schools: alcohol and Cannabis module: a harm-minimization, universal drug prevention program facilitated by the internet. Subst. Use Misuse. 2011;46(13):1651–1663. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2011.613441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton N.C. A pilot study of an online universal school-based intervention to prevent alcohol and cannabis use in the UK. BMJ Open. 2014;4(5) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton N.C. A systematic review of combined student- and parent-based programs to prevent alcohol and other drug use among adolescents. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2017;36:337–351. doi: 10.1111/dar.12497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onrust S.A. School-based programmes to reduce and prevent substance use in different age groups: what works for whom? Systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2016;44:45–59. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Özdemir M., Koutakis N. Does promoting parents' negative attitudes to underage drinking reduce adolescents' drinking? The mediating process and moderators of the effects of the Örebro prevention Programme. Addiction. 2016;111(2):263–271. doi: 10.1111/add.13177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pankratz M.M. Implementation fidelity in a teacher-led alcohol use prevention curriculum. J. Drug Educ. 2006;36(4):317–333. doi: 10.2190/H210-2N47-5X5T-21U4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poelen E.A. Predictors of problem drinking in adolescence and young adulthood. A longitudinal twin-family study. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2009;18(6):345–352. doi: 10.1007/s00787-009-0736-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riesch S.K. Strengthening families program (10–14): effects on the family environment. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2012;34(3):340–376. doi: 10.1177/0193945911399108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roebroek L., Koning I.M. The reciprocal relation between Adolescents' School engagement and alcohol consumption, and the role of parental support. Prev. Sci. 2016;17(2):218–226. doi: 10.1007/s11121-015-0598-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossmanith A. School drug education: looking for direction of Substance. 2006;4(4):16–19. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan S.M., Jorm A.F., Lubman D.I. Parenting factors associated with reduced adolescent alcohol use. A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Aust NZ J Psychiatry. 2010;44 doi: 10.1080/00048674.2010.501759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan S.M. Parenting strategies for reducing adolescent alcohol use: a Delphi consensus study. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders M.R. What are the parenting experiences of fathers? The use of household survey data to inform decisions about the delivery of evidence-based parenting interventions to fathers. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2010;41(5):562–581. doi: 10.1007/s10578-010-0188-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seljamo S. Alcohol use in families: a 15-year prospective follow-up study. Addiction. 2006;101(7):984–992. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shortt A.L. Family, school, peer and individual influences on early adolescent alcohol use: first-year impact of the resilient families programme. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2007;26(6):625–634. doi: 10.1080/09595230701613817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit E. Family interventions and their effect on adolescent alcohol use in general populations: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;97(3):195–206. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teesson M. Preventing Harmful Substance Use. John Wiley & Sons Ltd.; 2009. Substance use and mental health in longitudinal perspective; pp. 43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Teesson M. The CLIMATE schools combined study: a cluster randomised controlled trial of a universal internet-based prevention program for youth substance misuse, depression and anxiety. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:32. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-14-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teesson M. Combined universal and selective prevention for adolescent alcohol use: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Psychol. Med. 2017;47(10):1761–1770. doi: 10.1017/S0033291717000198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toumbourou J.W. Reduction of adolescent alcohol use through family-school intervention: a randomized trial. J. Adolesc. Health. 2013;53(6):778–784. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Vorst H. The impact of alcohol-specific rules, parental norms about early drinking and parental alcohol use on adolescents' drinking behavior. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2006;47(12):1299–1306. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogl L. A computerised harm minimisation prevention program for alcohol misuse and related harms: randomised controlled trial. Addiction. 2009;104 doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogl L.E. A universal harm-minimisation approach to preventing psychostimulant and cannabis use in adolescents: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Subst. Abuse Treat. Prev. Policy. 2014;9(1):24. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-9-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Vorst H., Engels R.C., Burk W.J. Do parents and best friends influence the normative increase in adolescents' alcohol use at home and outside the home? J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs. 2010;71(1):105–114. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO Global health observatory data: Global information system on alcohol and health (GISAH) 2016. http://www.who.int/gho/alcohol/en/ Jan 4 2016; Available from.

- WHO . World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2014. Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wickrama K.A. The intergenerational transmission of health-risk behaviors: adolescent lifestyles and gender moderating effects. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1999;40(3):258–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yap M.B.H. Modifiable parenting factors associated with adolescent alcohol misuse: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Addiction. 2017;112(7):1142–1162. doi: 10.1111/add.13785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]