Abstract

Mixed findings regarding the long-term efficacy of cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) for the treatment of hoarding has led to the investigation of novel treatment approaches. “Blended” therapy, a combination of face-to-face (f2f) and online therapy, is a form of therapy that enables longer exposure to therapy in a cost-effective and accessible format. Blended therapy holds many benefits, including increased access to content, lower time commitment for clinicians, and lower costs. The aim of the present study was to develop and evaluate a “blended” treatment program for hoarding disorder (HoPE), involving 12-weeks of face-to-face group therapy, and an 8 week online therapist assisted program. A sample of 12 participants with hoarding symptomology were recruited from the Melbourne Metropolitan area, and were involved in one of two conditions; 12 weeks group therapy +8 weeks online therapy (bCBT) or 12 weeks group therapy +8 weeks waitlist +8 weeks online therapy. Questionnaires were completed at all time points. The 8-week online component consists of 8 CBT-based modules, addressing psychoeducation, goal setting, motivation, relapse prevention and other key components. No significant differences were found over time between the bCBT group and waitlist control group, however trends suggested continued improvement in overall hoarding scores for the bCBT group, when compared to the waitlist control group. There were significant differences in scores from pre-treatment to 28 weeks, suggesting that all participants who were involved in the online intervention showed continued improvement from pre-treatment to post-treatment. This study highlights the potential benefit of novel formats of treatment. Future research into the efficacy of blended therapy would prove beneficial.

Highlights

-

•

The study aimed to develop and evaluate a ‘blended’ treatment program for hoarding disorder (HoPE), consisting of 12-weeks of GCBT and an 8 week online component.

-

•

Results showed significant decreases in overall hoarding severity for all participants involved in blended program

-

•

No significant differences between bCBT and waitlist control, however, bCBT group demonstrated trends suggesting continued improvement

-

•

This study highlights the potential benefit of novel formats of treatment

1. Introduction

Hoarding disorder is a complex psychological disorder, characterized by excessive acquisition and difficulty in discarding possessions regardless of value (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013; Frost and Hartl, 1996). Hoarding Disorder has been suggested to be apparent in approximately 2–5% of the population (Cath et al., 2017; Iervolino et al., 2009; Nordsletten et al., 2013; Samuels et al., 2008), and has a significant impact on many domains of life, including daily functioning, interpersonal relationships and on occupation (Grisham et al., 2008; Tolin et al., 2008). While previously considered to be as a sub-category of OCD, hoarding disorder is now classified as a distinct disorder (APA, 2013), with research finding significant benefits of a range of hoarding-specific treatments (Tolin et al., 2015).

Psychological treatments for hoarding disorder are mainly based on a cognitive-behavioral model, with program elements including exposure to sorting and categorizing; psychoeducation, goal setting, cognitive challenging and restructuring, along with various homework tasks. A recent meta-analysis conducted by Tolin et al., 2015 examined the comparative effect sizes across CBT hoarding treatment studies. Studies have used varying treatment formats, including CBT-based treatment, pharmacotherapy, and bibliotherapy, with the number of sessions of psychological interventions ranging from 13 to 33 (M = 20.2). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of hoarding disorder was found to be highly effective in reducing overall hoarding severity, in both individual and group settings (Hedges's g = 0.82; Tolin, Frost, Steketee, & Muroff., 2015). However, a more recent meta-analysis found that aggregate data of long-term studies did not indicate that clutter and other hoarding-related symptoms continued to decrease after the termination of treatment (Fitzpatrick, Nedeljkovic, Moulding, & Kyrios, unpublished). These findings may suggest that continued improvement in clutter may require additional or ongoing support (Fitzpatrick et al. unpublished; Tolin et al., 2015). Hence, although the results of CBT-based programs for hoarding disorder are promising, the complex and pervasive nature of hoarding disorder may suggest a need for a more innovative treatment approach, which provides additional support that is more cost-effective and accessible. This is particularly the case, given that – while CBT-based treatments are effective in reducing symptoms – most people finish treatment with significant symptoms, with only 35% of participants reporting clinically significant change (Tolin et al., 2015).

Online treatment programs, particularly internet-based cognitive behavior therapy (iCBT) have had great success in treating a range of mental health conditions, such as depression, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and body dysmorphic disorder (Andersson et al., 2012; Andrews et al., 2014; Enander et al., 2016; Mewton et al., 2014; Wootton, 2016). In comparison to traditional face-to-face CBT, iCBT provides a consumer with benefits such as access to the programs at any time and place, reduced cost, and the potential to seek support in an anonymous environment (Carroll and Rounsaville, 2010). Several meta-analyses have demonstrated that iCBT for conditions such as anxiety is more effective than a no treatment comparison, and it is even more effective than face-to-face treatment in some trials (Andersson and Cuijpers, 2009; Andersson et al., 2014a, Andersson et al., 2014b; Berger et al., 2014; Cuijpers et al., 2009; Lewis et al., 2012; Romijn et al., 2015). Although still in its early stages, iCBT for hoarding disorder has been found to be beneficial. Muroff et al. (2010) examined the effectiveness of an existing online CBT-based self-help program for hoarding disorder, with both active intervention and waitlist control participants. Participants in the intervention condition were found to demonstrate modest improvement over a 6-month and 15-month period. However, the findings were not found to be comparable in efficacy to face-to-face CBT in other trials (Muroff et al., 2010). Interestingly, those who were engaged in the online intervention for a longer period of time reported milder symptoms at the conclusion of treatment than did shorter-term participants, which may suggest that extended access to treatment may prove beneficial in terms of sustaining change or even continuing progress. These findings may suggest that, although online treatment may demonstrate significant benefits, this treatment format may be limited due to a lesser capacity than a face-to-face medium to provide empathy and rapport, and a lesser ability to tailor content in an individualized fashion. Furthermore, participants in iCBT usually do not have the opportunity to benefit from the potential benefits of face-to-face therapy outside of the therapeutic techniques themselves; for example, group CBT for hoarding has a number of non-specific helpful factors, including normalization, mutual aid and social cohesion (Schmalisch et al., 2010).

1.1. Efficacy of blended therapy

Blended therapy (bCBT), the combination of face-to-face therapy and online therapy, is an innovative treatment option that has the potential to combine the benefits of both treatment formats. For those with hoarding disorder, bCBT could provide the individual with benefits such as increased engagement as well as rapport, but also provide a potential crucial ability for the person to extend therapy - continuing therapeutic supports. Furthermore, the online component of therapy, accessible “in the home”, enables individuals to engage in discarding and other tasks “during therapy”. This may increase the completion of homework tasks, traditionally prescribed in CBT treatment, which has previously been suggested to predict poor treatment compliance (Tolin and Steketee, 2007). Maintaining progress in therapy has been described as a continual struggle for those with hoarding disorder, and the momentum may be maintained when engaging in therapy at home. bCBT may therefore provide support beyond that available in a health care system with limited resources, thus increasing accessibility, in a cost-effective manner (Romijn et al., 2015). Providing psychotherapy through a modality that is less subject to time constraints, and in a format that does not create more demand on mental health service providers, may thus be a logical alternative to sole face-to-face therapy (Newman et al., 2003).

Although the concept of blended therapy is still in its infant stages, it has a number of potential benefits. As noted more generally by Ong et al. (2015), the potential benefits of bCBT include: (a) the client being able to access and review content at any time, (b) its having lower costs when compared to face-to-face treatment, (c) its having lower time commitment for clinicians, (d) its minimizing the waiting time between initial face-to-face group treatment programs and subsequent continued support, (e) its having the potential for a client to take more of an active role in treatment, given the self-paced nature of the iCBT component of treatment, (f) its providing an ability for individuals with hoarding disorder to actively de-clutter immediately after face-to-face treatment, using the online program to maintain their motivation and momentum, (g) its assisting with reducing feelings of social isolation commonly experienced in hoarding disorder, and finally (h) its enabling the transmission of photographs from the participant to therapist to track the client's continued progress and enhance accountability. Studies highlight the importance of integrating therapist contact into iCBT programs, with empirical research finding that the therapeutic alliance predicts treatment outcome regardless of the therapeutic approach (Richards and Simpson, 2015).

To date, the term “blended” therapy has been used to describe varying combinations of face-to-face and online support. Research has examined the integration of online modules with face-to-face therapy, for use either in-between face-to-face sessions, prior to face-to-face sessions in terms of preparing the client for therapy, or post-interventions as a form of supplemental therapy. In the form of face-to-face therapy with inter-session online therapy, bCBT has been suggested to help the therapeutic relationship and lead to further progress post-therapy (Kemmeren et al., 2016). Qualitative data from a blended acceptance and commitment-based program found that participants reported greater breadth, greater exposure to treatment, depth and quality of the face-to-face therapy as a result of the technological adjunct between therapy sessions (Richards and Simpson, 2015). Carroll et al. (2008) examined the role of between-session supplemental online therapy for substance use disorders, which involved weekly individual and group counseling, in addition to access to bi-weekly CBT-based modules for substance use reduction for six weeks. Carroll et al. found that those who had access to the additional bi-weekly modules showed significantly fewer positive drug screen results and had longer periods of abstinence when compared to those in the Treatment As Usual (TAU) group. These findings may suggest that additional support, in the form of an inter-session online CBT based program, may improve the quality, quantity and outcome of therapy.

1.2. Continued care post-treatment/aftercare

Researchers have attempted to integrate supplemental online CBT-based treatment programs into face-to-face therapy in a number of ways. Post-treatment programs, also known as “aftercare” or “maintenance phase treatments”, aim to provide psychological treatment after acute psychotherapy, and have been found to improve the likelihood of the outcome being sustained (Bockting et al., 2005; Ebert et al., 2013b; McKay et al., 1996). For example, Kordy et al. (2011) examined the use of an online aftercare program post-hospital discharge for 254 patients experiencing psychosomatic symptoms, finding that it led to sustainable, and significant improvements in psychological wellbeing, social difficulties and psychosocial abilities, when compared to a control condition. In a randomized controlled trial, Holländare et al. (2011) investigated the use of a 10-week iCBT program by people with major depression after completing face-to-face treatment with a psychologist or psychotherapist, compared to a control group of 84 participants. They found that significantly fewer participants demonstrated relapse in the online CBT group when compared to the waitlist control, with the differences between groups maintained for 6 months (Holländare et al., 2011). Studies have found brief blended programs have success in maintaining physical activity levels after a brief motivational interviewing intervention delivered by telephone or face-to-face (Fleig et al., 2013; Goyder et al., 2014). Research therefore suggests that the provision of continued care or aftercare post-treatment may play a key role in preventing relapse, but due to the novelty of such treatment plans, further research is required.

1.3. Intention of Hoarding Plus E-therapy (HoPE)

As noted previously, while face-to-face treatment is effective for hoarding disorder, a majority of individuals do not achieve clinically significant change, and without ongoing support, there appears to be limited improvement in the disorder, which is consistent with its chronic nature. Therefore, although bCBT is still in its early stages as an overall treatment modality, it holds potential benefit for hoarding, given its ability to provide, at a low cost, ongoing support. This is particularly important in a country such as Australia, where there are a number of rural and regional areas with low access to services, and where access to subsidized treatment includes a capped number of sessions via Medicare (Australia's publicly funded health care system). Developing a cost effective and accessible bCBT program, that is suitable to the local health care system, may assist in maintaining motivation, reducing the likelihood of relapse, and subsequently improving longer-term outcome (Andersson and Titov, 2014).

The aim of this study was to develop and evaluate the efficacy of a “blended” format of treatment in continuing to improve hoarding symptoms post face-to-face CBT, this program was denoted Hoarding Plus E-therapy (HoPE). The face-to-face component of a 12-session group therapy program, was supplemented by an 8-week CBT-based online program for hoarding, with online therapist support. Participants were allocated to the treatment group, which involved a 12-week face-to-face group-based CBT program plus an 8-week online CBT-based program, or a waitlist condition, which involved the same 12-week group plus an 8-week waitlist period, before these participants also undertook the 8-week online program. We hypothesized that the 12 + 8-week “blended” therapy program would result in a greater decrease in scores from pre-treatment to post-intervention on the Savings Inventory – Revised (SI-R), a well-validated measure of hoarding symptoms, when compared to the waitlist control group. In addition, we hypothesized that hoarding specific beliefs, and also mood (depression, anxiety and stress) would also decrease from post-treatment following the 8-week online intervention. Finally, we hypothesized that all participants, regardless of waitlist periods, would show a decline in scores on the SI-R after engaging in the online intervention.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Sixteen participants were recruited from the Melbourne Metropolitan areas by self-referral, referral from mental health professionals, primary care physicians, and housing authorities. All participants had taken part in the 12-week group cognitive behavior therapy program for Hoarding Disorder at Swinburne University of Technology (see Moulding et al., 2016). Three participants did not complete the program. Reasons for dropout included health problems requiring long-term hospitalization (n = 2), and other mental health concerns. Allocation to the waiting period was not random, but reflected the order of entering the study, with the first six participants being waitlisted. Therefore, six participants provided data for the waitlist period, and six participants started the program immediately after treatment. All participants in the waitlist condition also completed the online program after the waitlist period, however two participants did not provide post-bCBT data.

2.2. Measures

Savings Inventory-Revised (SI-R; Frost et al., 2004). The SI-R is designed to measure an individual's level of clutter, difficulty of discarding and excessive acquisition. This 23-item self-report measure was factor analytically derived and has been found to effectively distinguish between hoarding and non-hoarding groups (Frost et al., 2004). The SI-R has been found to have good internal consistency (α = 0.88) and test-retest reliability, and has demonstrated strong correlations with other measures of hoarding (Frost et al., 2004).

Savings Cognitions Inventory-Revised (SCI-R; Steketee et al., 2003). The SCI-R is a 31-item self-report measure, which was devised to assess the attitudes and beliefs among compulsive hoarders (Steketee et al., 2003). The SCI-R has four factor-analytically derived subscales, including emotional attachment, memory, control and responsibility. It has been found to have very good to excellent internal consistency (Cronbach's α = 0.86–0.95) and to effectively distinguish participants with hoarding from those with OCD and from community controls (Steketee et al., 2003). The SCI-R has also been found to show a moderately high correlation with the SI-R inventory (Steketee et al., 2003).

Depression and Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21; Lovibond and Lovibond, 1995). The DASS is a 21-item self-report scale measuring levels of depression, anxiety and stress. This scale has high reliability and concurrent validity, and each scale is suggested to have high internal consistency, with Cronbach's α ranging from 0.87 to 0.94.

The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview 5.0 (MINI; Sheehan et al., 1997). The MINI is a short structured interview established to identify psychiatric disorders, in accordance with the DSM-IV. At the initiation of this study (2012), a structured clinical assessment in accordance with the DSM-V was not available. So although this version of the MINI did not incorporate the diagnostic criteria for hoarding, the Scheduled Interview for Hoarding Disorder (SIHD) was also used to ensure adequate assessment for hoarding disorder, which discusses all relevant information relevant to the hoarding criteria later included into the DSM-V (APA, 2003). Research suggests the MINI to be a reliable and valid diagnostic tool, showing good inter-rater reliability and test-retest reliability (Lecrubier et al., 1997; Sheehan et al., 1997).

The Scheduled Interview for Hoarding Disorder (SIHD; Nordsletten et al., 2013a, Nordsletten et al., 2013b) is a semi-structured interview, which is designed to complement the new diagnostic criteria for hoarding disorder (HD) in the DSM-5, and also includes a risk assessment. The SIHD has been found to have “near perfect” inter-rater reliability and excellent convergent and discriminant validity. In addition, it has also been found to relate to existing hoarding measures (Nordsletten et al., 2013a, Nordsletten et al., 2013b).

2.3. Procedure

Participants were initially enrolled in a structured 12-week group program, but were provided information about the additional Internet component towards the completion of the program. If participants expressed interest, they were then followed up with a phone call to assess eligibility to be involved in the study. If eligible, the participant was given an initial assessment session over the phone, in order to complete the pre-assessment questionnaire, the MINI interview and to be talked through how to use the online program. If the participant did not have access to the Internet they were offered use of a tablet with wireless Internet. Participants were informed that there were eight modules, with one to complete each week. They were also informed of the e-therapist assistance, which involved email correspondence from the e-therapist each week, with the opportunity for the participant to respond for feedback or to ask questions. The participants were provided detailed instructions on how to use the program and were able to contact the e-therapist for assistance over the phone when getting started. After the 8-week online program, participants were directed to complete a survey online at 20 weeks (12 week group +8 week post-group). Participants in the waitlist condition were then directed to use the online program.

2.4. HoPE program development

The HoPE online supplemental intervention was created to provide individuals with continued support for their hoarding symptoms post-treatment. The content was informed by the Cognitive Behavior Group Therapy manual for Hoarding Disorder developed by Moulding et al., (2016), which was based on the CBT approach developed by Steketee and Frost (2006). Various materials were adapted to reinforce key material outlined in the group, as well as the addition of content around relapse prevention, motivational interviewing, relaxation, and examining barriers to continuation with de-cluttering. A clinical team involved in the face-to-face group therapy and experts in the field reviewed all content. The structure and format of the program was modeled off previous and current online interventions for other disorders (Klein et al., 2011; Kyrios et al., 2014). The Mental Health Online platform was used to host the program, an interface developed by the National eTherapy Centre (NeTC).

The program consisted of 8 weekly modules. Each module provided the participants with worksheets, interactive textboxes that the e-therapist could review, and vignettes of various challenges that individuals have faced with hoarding, and how these could be overcome. Based on the research of Muroff et al. (2010), a great focus was placed on interactive content in order to increase engagement and interest. There was also homework provided each week, and a review of this homework at the start of each module. These homework tasks aimed to reinforce what was learnt during sessions, and to encourage continued application of new knowledge in the home (Frost and Hartl, 1996).

Given research that suggests that the therapeutic relationship predicts treatment outcome, regardless of the therapeutic approach (Horvath et al., 2011; Norcross, 2002; Richards and Simpson, 2015; Ahn and Wampold, 2001), this program involved the option of therapist assisted email support, where the participants were given the option of sending up to two emails per week to their e-therapist. The provision of e-therapist support was intended to increase the participants' perceived support and to increase their adherence to the program (Richards and Simpson, 2015). The email format was chosen as it has been suggested to be the best form of adjunct therapy (Clough and Casey, 2011). The e-therapist nominated a day to each participant when they would expect a weekly response from the e-therapist. The e-therapist provided weekly feedback on homework tasks, provided support and encouragement for each participant's progress and to address their challenges, and helped to reinforce key components from the 8-week program. The e-therapist support enabled participants to continue to work on challenges that they encountered during the group and to identify barriers faced in progression after the termination of the group (Whisman, 1990; Andersson et al., 2014a, Andersson et al., 2014b). The e-therapist support required significantly less interaction than would face-to-face therapy, with the e-therapist spending an average of 11.5 min to respond to emails and check each participant's progress. This time was logged by each e-therapist after each interaction with the client. The e-therapist was a provisional psychologist (first author), who had close supervision by a clinical psychologist (second author) and training in the treatment of hoarding disorder (second and third author). Participants retained the same e-therapist throughout the program, and, at the conclusion of the program, the participants were able to have continued access to the program. The ability to review information provided at any time is a significant benefit of bCBT based programs, for example the ability of the participant to access various relaxation recorded exercises at times of distress (Kemmeren et al., 2016).

The program was designed to begin immediately after the group, as fewer days between the end of a treatment program and first appointment of continuation has been suggested to show increased engagement in post-intervention support (Clough and Casey, 2011). Furthermore, the program involves guidance, which has been found to demonstrate significantly better outcomes than treatment without guidance (Andersson and Titov, 2014; Richards et al., 2015; Spek et al., 2007; Palmqvist et al., 2007). An outline of the program structure can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1.

Contents in weekly modules for hoarding online plus.

| Content | Homework | |

|---|---|---|

| Module 1 | Recap of key themes and information learnt in the group | Engaging in pleasurable activities Thinking about goals for this program |

| Module 2 | Revisiting your hoarding model Vignette Goal setting |

Sorting sessions |

| Module 3 | Sorting/in-session sorting Anxiety around sorting |

Weekly planning Sorting sessions |

| Module 4 | Maintaining motivation Meditation Stages of change model Useful strategies |

Sorting Updating weekly planner Gathering paper for next in-session sorting module |

| Module 5 | Organization of belongings e.g., Paper planning |

Practicing organization skills Sorting sessions |

| Module 6 | Challenging your cognitions Values |

Positive activities Thinking about your values Sorting sessions |

| Module 7 | Managing set-backs Acquiring |

Developing personalized strategies to manage set-backs |

| Module 8 | Summary Planning and goals revisited Time management |

Sorting sessions and reviewing Module 7 |

2.5. Data analysis

Data was analyzed using SPSS v21 and SPSS Missing Value Analysis 7.5. Missing data was imputed using expectation maximization. A repeated measures Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was conducted to assess changes in hoarding behavior across three time points - pre-treatment, post face-to-face treatment (12-weeks) and post online intervention (20 weeks) for participants in the bCBT or intervention-waitlist condition. In addition, eight participants provided data at 28 weeks, with four of the participants that were initially in the waitlist condition providing data after involvement in the intervention. Effect sizes were calculated using partial eta squared, with 0.01, 0.06 and 0.14 interpreted as small, medium and large effect sizes, respectively (Cohen, 1988). Three participants did not provide post-intervention data, and therefore were excluded from the analysis. Post hoc analysis was undertaken where relevant. Participants demonstrated significant improvement on the SI-R from pre-treatment to post-treatment in the group program (F(1, 11) = 6.20, p = .03, η2ρ = 0.36). The sample demographics for the involved participants can be seen in Table 2.

Table 2.

Demographics of all participants included in the study.

| Characteristic | Participant characteristics N = 12 |

|---|---|

| Mean age (SD) | 55.20 (10.50) |

| % female | 90% |

| Martial status – single | 70% |

| Education level – post HS | 70% |

| Employed | 40% |

| Previous treatment | 40% |

| Medication – current use | 50% |

| Comorbidity | |

| MDD | 60% |

| GAD | 20% |

| OCD | 10% |

| SI-R < 42 | 17% |

| SI-R total | 60.99 (18.25) |

| SCI total | 96.74 (40.66) |

| DASS-21 total | 19.49 (13.28) |

Note. MDD = Major Depressive Disorder; GAD = Generalized Anxiety Disorder; OCD = Obsessive Compulsive Disorder; SI-R = Savings Inventory Revised, SCI = Savings Cognition Inventory, DASS-21 = Depression and Anxiety Stress Scale.

3. Results

3.1. Hoarding symptom changes

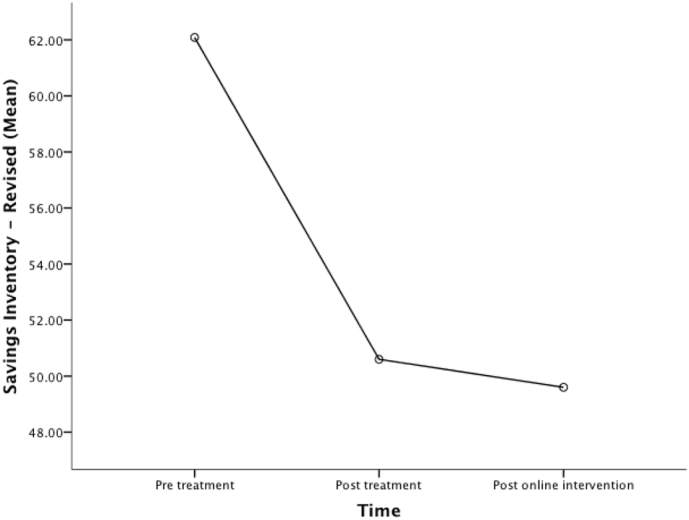

Analysis of scores on the SI-R revealed no significant main effect for time or time by condition interaction (F(1, 20) = 3.66, p = .07, η2ρ = 0.27). However, there were evident trends across the three time points, with notable declines from pre-treatment to post-treatment (12 weeks) and pre-treatment to 20 weeks in the bCBT condition, with the percentage of reduction in symptoms from baseline to be 15.62% and 18.86%, respectively (see Fig. 1). In comparison, those in the waitlist condition showed an increase in scores on the SI-R at 20 weeks, demonstrating a reduction of percentage change from 16.94% (change from pre-post treatment) to 9.78% (pre-treatment to 20 weeks). The effect sizes for participants in the bCBT condition were large, and relative to other published effect sizes within the literature, which is notable, considering the small sample size. SI-R subscales were also examined (clutter, difficulty discarding, acquisition), with the analysis of the clutter subscale revealing a significant effect for time (F(2, 20) = 4.32, p = .03, η2ρ = 0.30), but with no interaction between time and condition (see Fig. 2). Scores on the SI-R difficulty discarding and acquisition subscales showed no significant main effect for time or time by condition interaction, however, these subscales also demonstrated trends over the three time points (see Table 3). Finally, analyses of the SCI and DASS showed no effect for time or time by condition interaction (see Table 3).

Fig. 1.

Mean scores on SI-R across the blended intervention (n = 6) and waitlist conditions (n = 6).

Fig. 2.

Mean scores on the SI-R clutter subscale across the blended intervention (n = 6) and waitlist conditions (n = 6).

Table 3.

Mean scores, effect sizes and percentage change on all measures for mixed model ANOVA.

| Measure | N | Condition | Pre Mean (SD) | Post Mean (SD) | 20-week follow-up Mean (SD) | Within groups analysis (F) | p value | η2ρ | Cohen's d | % change baseline to pre-post treatment | % change baseline to 20 week follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SI-R total | 6 | Control | 62.81 (15.48) | 52.17 (14.65) | 56.67 (16.02) | F(1, 20) = 3.66 | .07a | 0.27 | 1.22 | 16.94 | 9.78 |

| 6 | Blended int. | 61.83 (19.88) | 52.17 (12.06) | 50.17 (12.37) | 15.62 | 18.86 | |||||

| SI-R Diff. | 6 | Control | 21.00 (3.74) | 17.67 (3.93) | 18.00 (3.95) | F(2,20) = 2.75 | .09 | 0.22 | 1.06 | 16.00 | 14.29 |

| 6 | Blended int. | 20.17 (6.27) | 17.58 (4.13) | 18.33 (4.37) | 12.84 | 9.12 | |||||

| SI-R Acq. | 6 | Control | 14.00 (7.32) | 12.33 (6.71) | 12.83 (7.14) | F(2,20) = 1.50 | .25 | 0.13 | 0.77 | 11.93 | 8.36 |

| 6 | Blended int. | 15.67 (7.81) | 13.00 (2.76) | 12.67 (3.50) | 17.04 | 19.14 | |||||

| SI-R clutter | 6 | Control | 27.81 (5.38) | 22.17 (5.42) | 25.67 (7.09) | F(2, 20) = 4.32 | .03⁎⁎ | 0.30 | 1.31 | 20.28 | 7.70 |

| 6 | Blended int. | 26.00 (6.54) | 21.58 (5.95) | 18.83 (5.89) | 17.00 | 27.58 | |||||

| SCI total | 6 | Control | 84.58 (37.32) | 81.17 (40.72) | 78.00 (36.93) | F(2, 18) = 0.52 | .60 | 0.06 | 0.51 | 4.03 | 7.78 |

| 5 | Blended int. | 113.08 (33.97) | 109.00(28.78) | 104.60(25.77) | 3.61 | 7.50 | |||||

| DASS | 5 | Control | 16.58 (10.24) | 16.00 (13.38) | 16.20 (16.84) | F(2, 18) = 0.05 | .95 | 0.01 | 0.20 | 3.50 | 2.29 |

| 5 | Blended int. | 22.20 (16.27) | 25.00 (9.98) | 23.20 (8.67) | +12.6 | +4.5 |

Note. SI-R = Savings Inventory Revised, SCI = Savings Cognition Inventory, DASS-21 = Depression and Anxiety Stress Scale, Diff = Difficulty Discarding; Acq = Acquisition.

Greenhouse Gessier correction.

p < .05.

3.2. Analyses including additional participants post-waitlist period

Additional analyses of four participants who undertook bCBT after the waitlist period were compared with the four participants who provided additional data at 28 weeks (see Table 4). Analysis of scores on the SI-R revealed a significant main effect for time (F(3, 18) = 3.88, p = .03, η2ρ = 0.39). Furthermore, post-hoc tests revealed that SI-R total scores significantly decreased from pre-treatment to post-treatment, and post-treatment to 28 weeks (p < .05). As evident in Fig. 3, there are apparent trends evident between the conditions, with those in the waitlist condition appearing to show a decline in improvement, followed by greater improvement after involvement in the bCBT intervention; however, the time by condition interaction analysis was not significant. These findings suggest that the participants in the waitlist condition appeared to show improvement in hoarding symptoms after involvement in the bCBT condition, in a similar pattern to those immediately involved in bCBT.

Table 4.

Mean scores, effect sizes and percentage change for participants who provided follow-up data.

| Measure | N | Condition | Pre Mean (SD) | Post Mean (SD) | 20-week follow-up Mean (SD) | 28-week follow-up Mean (SD) | Within groups analysis (F) | p value | η2ρ | Cohen's d | % change baseline to post-treatment | % change baseline to 20 weeks | % change baseline to 28 weeks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SI-R total | 4 | Control | 62.47 (19.97) | 48.35 (17.19) | 54.75 (20.32) | 47.00 (16.02) | F(3, 18) = 3.88 | .03⁎⁎ | 0.39 | 1.60 | 22.60% | 12.36% | 24.76% |

| 4 | Blended int. | 62.75 (22.49) | 48.00 (8.29) | 44.75 (11.00) | 46.5 (5.20) | 23.51% | 28.69% | 25.90% | |||||

| SI-R Diff. | 4 | Control | 21.25 (4.65) | 15.75 (3.30) | 16.50 (4.12) | 15.00 (3.83) | F(3, 18) = 3.79 | .029⁎⁎ | 0.39 | 1.60 | 25.88% | 22.35% | 29.41% |

| 4 | Blended int. | 19.75 (6.40) | 16.63 (3.35) | 16.50 (4.20) | 14.75 (3.30) | 15.80% | 16.46% | 25.32% | |||||

| SI-R Acq. | 4 | Control | 13.00 (9.20) | 11.25 (8.38) | 12.00 (9.06) | 15.50 (5.20) | F(3, 18) = 2.38 | .10 | 0.28 | 1.25 | 13.46% | 7.70% | +19.23% |

| 4 | Blended int. | 16.75 (8.30) | 12.00 (1.63) | 11.00 (2.58) | 15.00 (0.82) | 28.36% | 34.33% | 10.45% | |||||

| SI-R clutter | 4 | Control | 28.22 (6.45) | 21.25 (6.70) | 26.00 (9.13) | 18.00 (7.35) | F(3, 18) = 4.86 | .01⁎⁎ | 0.45 | 1.81 | 24.70% | 7.87% | 36.22% |

| 4 | Blended int. | 26.25 (8.18) | 19.38 (4.79) | 16.75 (6.13) | 19.25 (2.06) | 26.17% | 36.19% | 26.67% | |||||

| DASS | 3 | Control | 15.31 (13.54) | 9.67 (9.87) | 12.00 (17.44) | 18.33 (15.16) | F(3, 12) = 0.21 | .67 | 0.05 | 0.46 | 36.84% | 21.62% | +19.73% |

| 3 | Blended int. | 27.33 (20.75) | 29.00 (10.15) | 26.00 (10.58) | 26.00 (13.00) | +6.11% | 4.87% | 4.87% |

Note. SI-R = Savings Inventory Revised, DASS-21 = Depression and Anxiety Stress Scale, Diff = Difficulty Discarding; Acq = Acquisition; Blended int. = Blended intervention.

p < .05.

Fig. 3.

Mean scores on the SI-R across four time points for the blended intervention (n = 4) and waitlist conditions (n = 4) for participants who provided follow-up data.

3.3. Evaluation of bCBT for all participants

A repeated measured ANOVA was undertaken to examine the effect of time during treatment for all 10 participants (see Table 5). When examining pre-post scores and post bCBT scores for all participants in the intervention, there was a significant main effect for time (F(2, 18) = 4.86, p = .02, η2ρ = 0.35). Post hoc analyses revealed that there were significant differences in scores from pre to post-treatment and from pre-treatment to post online intervention, suggesting that all participants who were involved in the online intervention showed continued improvement from pre-treatment (see Fig. 4).

Table 5.

Mean scores, effect sizes and percentage change for all participants who completed bCBT.

| Measure | N | Pre Mean (SD) | Post Mean (SD) | Post online intervention Mean (SD) | Within groups analysis (F) | p value | η2ρ | Cohen's d | % change baseline to post-treatment | % change baseline to 28 weeks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SI-R total | 10 | 62.09 (18.78) | 50.60 (13.54) | 49.60 (11.67) | F(2,18) = 4.86 | .02⁎ | 0.35 | 1.47 | 18.50% | 20.12% |

| SI-R Diff. | 10 | 19.40 (5.85) | 16.15 (3.96) | 16.10 (3.57) | F(2,18) = 3.26 | .09 | 0.27 | 1.22 | 16.75% | 17.01% |

| SI-R Acq. | 10 | 19.98 (5.70) | 16.25 (4.65) | 15.30 (4.76) | F(2,18) = 4.41 | .05 | 0.33 | 1.40 | 18.67% | 23.42% |

| SI-R clutter | 10 | 25.60 (8.34) | 20.55 (5.73) | 19.60 (5.74) | F(2,18) = 4.91 | .05 | 0.35 | 1.47 | 19.73% | 23.44% |

| DASS | 8 | 19.62 (14.71) | 19.25 (12.15) | 19.38 (12.56) | F(2,14) = 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.001 | 0.06 | 1.89% | 1.22% |

Note. SI-R = Savings Inventory Revised, DASS-21 = Depression and Anxiety Stress Scale, Diff = Difficulty Discarding; Acq = Acquisition.

p < .05.

Fig. 4.

Mean scores for all participants after undertaking the online intervention (N = 10).

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to examine the efficacy of a “blended” format of treatment (bCBT) for hoarding disorder - a combination of face-to-face group therapy and online therapy. Contrary to the hypothesis, there were no significant differences over time on the SI-R total score between the bCBT group and waitlist control condition. However, there did appear to be trends evident in the data, showing a distinction between the bCBT group and the waitlist control. These trends seem to suggest that participants in the bCBT condition showed continued improvement in hoarding behavior whereas participants in the waitlist condition appeared to have an increase in hoarding behavior after the group. The bCBT condition also produced a large effect size on the SI-R total, which is comparable to other studies, with improvement ranging from 10 to 21% in group CBT (Muroff et al., 2010; Muroff et al., 2009, Steketee et al., 2000). These findings appear to provide support for the notion of “blended” therapy, and are consistent with findings from other “blended” treatment formats which have examined the benefits of continued maintenance treatment or “aftercare” post-inpatient discharge (Bauer et al., 2011; Ebert et al., 2013a, Ebert et al., 2013b; Golkaramnay et al., 2007; Kordy et al., 2011). Findings from these studies have highlighted the ability of internet-based programs to sustain treatment benefits post-discharge from face-to-face treatment. The lack of significant differences between groups may be due to a range of factors, however, further investigation with a larger sample size would prove beneficial.

Examination of the subscales found that there was a significant difference between the “blended” intervention group and waitlist control group from post f2f treatment to post-online treatment (20 weeks) on the clutter subscale only. These findings suggested that those who were involved in the bCBT condition showed further decline in their levels of clutter, whereas those in the waitlist condition appeared to demonstrate an increase in clutter scores at 20 weeks. Clutter showed the greatest improvement among all the measures, with a 27.58% change from pre-treatment to 20 weeks in the intervention condition, and a strong effect size of η2ρ = 0.30. This significant reduction in clutter is interesting, given that previous studies have highlighted that clutter generally shows weaker improvement than the other SI-R subscales (Tolin et al., 2015). These findings appear to support the notion that a greater duration of treatment for hoarding may be a key factor in a further reduction in clutter (Fitzpatrick et al., unpublished). Tolin et al. has also highlighted the importance of extended treatment, due to the timely nature of de-cluttering. The 20-week duration of blended therapy appears to enable continued support, in a format that may be more accessible to both consumers and clinicians with numerous time and monetary constraints. A program of this style may help meet the future demand and/or requirement for efficacious treatment programs for hoarding, providing extended access to resources and giving continued engagement.

There were no main effects of time and no time by condition interaction evident on scores on the Savings Cognition Inventory. These findings are inconsistent with previous research, which has found significant reduction in scores on the SCI, highlighting the importance of challenging beliefs and attachments in the treatment of hoarding (Frost et al., 2011a, Frost et al., 2012a, Frost et al., 2012b). The lack of significant findings may emphasize the difficult nature of challenging beliefs, and suggest that the greater focus on behavior change may eventually result in the challenging and reconstruction of core beliefs. The lack of significant changes in SCI may also be an indication of insufficient power.

There were no main effects of time nor a time by condition interaction of scores on mood as measured by the DASS. However, these findings appear to be consistent with previous research, which has found that mood has not followed the pattern of symptom change seen on the SI-R (Frost et al., 2011a; Frost et al., 2011b). A potential explanation of this may be due to the anxiety/stress provoking nature of undergoing treatment, particularly when treatment is evoking high levels of anxiety when participants are faced with decisions around discarding or non-acquisition (Timpano et al., 2011). It is not uncommon for anxiety and stress to be heightened when presenting for CBT for any condition, as the individual is generally aware that they will have to confront uncomfortable emotions. Indeed, both stress and anxiety rose (non-significantly) for both conditions, which appear to be consistent with the sensitive nature of the treatment/sorting. Given the sensitivity of individuals with hoarding symptoms to anxiety and other mood symptoms (Medley et al., 2013; Phung et al., 2015; Timpano et al., 2009; Wheaton et al., 2011), these findings may suggest a role for emotional regulation strategies in treatment, in order to provide individuals with more support in terms of regulating their stress or anxiety, rather than their avoiding decluttering.

The hypothesis that all participants, regardless of waitlist periods, would show a decline in scores on the SI-R after engaging in the online intervention was supported. The strong effect sizes demonstrated are comparable to other studies, particularly those with a longer duration (see Fitzpatrick et al., unpublished). These findings provide support for a bCBT format of treatment, with significant declines in the SIR total, clutter and acquisition subscales. Additional research into an integrated form of treatment, providing greater accessibility and in a cost effective format appears to be advantageous.

4.1. Clinical implications

The notable trends, significant differences between groups on the clutter subscale, and improvement when examining overall participants suggest that participants showed benefit from involvement in bCBT. This highlights the potential for “blended” therapy to be further examined and utilized, with its many practical advantages, such as continued support, in an accessible and cost effective format. One of the main drivers in the rationale of this study was to be able to develop a program that is congruent with the current healthcare model in Australia, where government rebates for psychological services are provided, but only for a limited number of sessions (originally 12, now reduced to 10); although the study is relevant to any system where access to services is limited by cost or accessibility. As we have seen in the hoarding literature to date, hoarding is a pervasive problem, and it requires significant time in treatment, particularly to address the large amounts of clutter. As such, knowledge of the benefits and usability of this novel form of treatment may assist in overcoming barriers due to limited accessibility of treatment – that is, a limited number of available and trained therapists, difficulty taking time off work, and associated stigma relating to mental health concerns. Internet-based support makes treatment flexible, and enables treatment without rigid time constraints (Carroll and Rounsaville, 2010; Hedman, 2014). Furthermore, enhanced accessibility enables access to content at times of distress, for people who are rurally/regionally located or who have physical ailments (Carroll and Rounsaville, 2010). Knowledge of the benefits of continued support may enable mental health practitioners to pursue alternative means of continuing treatment and help prevent relapse of clients. However, it is important to note that the requirement of bCBT does still involve the time of a therapist at the initial stage of the program. Therefore, the need for trained therapists, individuals taking time off work and the problem of stigma are issues that do still remain in the initial stages of treatment. Although pure iCBT does appear to address these concerns, the benefit of therapist involvement, particularly for engagement and accountability, are important, particularly with the presentation of hoarding.

Another important factor in the provision of treatment is cost. While the initial development of online programs incurs costs, as does development of secure online systems to provide the programs, once developed, computer-assisted therapies, especially with therapist assistance, are generally more cost-effective to deliver, as responding to queries/email assistance takes significantly less time per session (McCrone et al., 2004). Of course, reduction in travel and time off work for clients if they are employed further adds to indirect cost-benefits for the clients. Furthermore, various inconsistencies seen in clinical practice in standardized treatment may be less present in the standardized online programs, achieving a similar level of quality for each individual (Carroll et al., 2008). This is particularly important for hoarding, where the number of trained specialists is quite limited. Therefore, continued research into bCBT programs may enable clinicians to provide support to a greater number of clients, due to the lower time commitment.

Some might question why there needs to be a face-to-face component, and whether there is value in focusing instead on purely iCBT based therapy program. It is important to note that the face-to-face component in the treatment of hoarding is a significant component of treatment. It enables accountability that is likely to enhance commitment and adherence, provides the opportunity for the client to obtain support when faced with challenges, allows for encouragement from a clinician, particularly when small gains are made, and it enables tailored pacing and the ability to ask questions (Manber et al., 2015). Therefore, we believe that the “blended” format enables the individuals with the benefits of both aspects of treatment.

4.2. Limitations and future research

There are a number of limitations in this study. Firstly, the waitlist control condition was non-randomized, and reflected the order of entry into the study. Furthermore, like other studies, this study relied only on self-report data, with no clinician rated measure administered after the intake interview. Therefore, it is possible that participants have overemphasized or underemphasized their symptoms. The overemphasis of symptoms might suggest that individuals in the program may not have met the criteria for HD, since clutter was not visually assessed. Sixteen percent of individuals in the study did not reach the clinical cut-off of 42 points on the SI-R to be diagnosed with hoarding disorder. However, it is possible that this number may have been higher (or lower) with an assessment of clutter in the home for each participant. Other notable limitations include the low sample size, and the involvement of mostly female participants, although this is reflective of a majority of other hoarding studies (Moulding et al., 2016).

Future research examining the efficacy of “blended” therapy in hoarding disorder is essential. Although this study does suggest promising results, it is important for additional research, with larger sample sizes to further examine the treatment efficacy. In addition, future research into treatment that is tailored to the client would be beneficial. Current research in iCBT programs is examining the benefits of tailoring programs according to age/gender and other factors (Berger et al., 2014). Enhancing the personalization of the online component of “blended” therapy may improve engagement. Prochaska and Norcross (2001) highlight the importance of tailoring treatment programs, especially to a participants' stage of change, suggesting that this can enhance the outcome, and increase compliance and completion. In addition, future research examining the most effective format to structure “blended” treatment would be beneficial (stepped care mode, booster program, intermittent – between sessions), in addition to the level of involvement of the mental health practitioner, with previous research highlighting the importance of therapeutic alliance in iCBT.

4.3. Conclusion

A novel treatment approach, combining face-to-face therapy with an internet intervention, can provide the consumer with a more cost-effective and accessible treatment program, with added benefits of maintaining therapeutic alliance and providing the client ongoing support (Romijn et al., 2015). Furthermore, a treatment program of this format could potentially help the person maintain the gains of face-to-face treatment (Ebert et al., 2013a, Ebert et al., 2013b). Although there is limited research on the combination of both face-to-face and online interventions, it does appear that blended therapy may be a viable and attractive alternative to solely face-to-face or solely online-driven programs. It is therefore hoped that this study provides further impetus for development and evaluation of such programs, particularly for chronic disorders that require ongoing therapeutic support, such as hoarding disorder.

Role of funding sources

Funding for this study was provided by the Barbara Dicker Brain Sciences Foundation. The Barbara Dicker foundation had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Contributors

Author A and B designed the study, and developed the pilot program. Author A wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Author was involved in the initiation of the program on the online platform, and continual technical monitoring. All authors were involved in editing and approving the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interests with the authors.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the Barbara Dicker Brain Sciences Foundation for their generous funding.

Contributor Information

Molly Fitzpatrick, Email: mfitzpatrick@swin.edu.au.

Maja Nedeljkovic, Email: mnedeljkovic@swin.edu.au.

References

- Ahn H.N., Wampold B.E. Where oh where are the specific ingredients? A meta-analysis of component studies in counseling and psychotherapy. J. Couns. Psychol. 2001;48(3):251–257. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric, A . 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; Arlington, VA: 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson G., Cuijpers P. Internet-based and other computerized psychological treatments for adult depression: a meta-analysis. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2009;38(4):196–205. doi: 10.1080/16506070903318960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson G., Titov N. Advantages and limitations of internet-based interventions for common mental disorders. World Psychiatry. 2014;13(1):4–11. doi: 10.1002/wps.20083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson E., Enander J., Andrén P., Hedman E., Ljótsson B., Hursti T.…Rück C. Internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy for obsessive–compulsive disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Psychol. Med. 2012;42(10):2193–2203. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712000244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson E., Steneby S., Karlsson K., Ljótsson B., Hedman E., Enander J.…Rück C. Long-term efficacy of internet-based cognitive behavior therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder with or without booster: a randomized controlled trial. Psychol. Med. 2014;44(13):2877–2887. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714000543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson G., Cuijpers P., Carlbring P., Riper H., Hedman E. Guided internet-based vs. face-to-face cognitive behavior therapy for psychiatric and somatic disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry. 2014;13(3):288–295. doi: 10.1002/wps.20151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews G., Newby J., Williams A. Internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy for anxiety disorders is here to stay. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2014;17(1):1–5. doi: 10.1007/s11920-014-0533-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer S., Wolf M., Haug S., Kordy H. The effectiveness of internet chat groups in relapse prevention after inpatient psychotherapy. Psychother. Res. 2011;21(2):219–226. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2010.547530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger T., Boettcher J., Caspar F. Internet-based guided self-help for several anxiety disorders: a randomized controlled trial comparing a tailored with a standardized disorder-specific approach. Psychotherapy. 2014;51(2):207–219. doi: 10.1037/a0032527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bockting C., Schene A., Spinhoven P., Koeter M., Wouters L., Huyser J., Kamphuis J. Preventing relapse/recurrence in recurrent depression with cognitive therapy: a randomized controlled trial. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2005;73(4):647–657. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.4.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll K.M., Rounsaville B.J. Computer-assisted therapy in psychiatry: be brave-it's a new world. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2010;12(5):426–432. doi: 10.1007/s11920-010-0146-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll K., Ball S., Martino S., Nich C., Babuscio T., Nuro K.…Rounsaville B. Computer-assisted delivery of cognitive-behavioral therapy for addiction: a randomized trial of CBT4CBT. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2008;165(7):881–888. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07111835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cath D.C., Nizar K., Boomsma D., Mathews C.A. Age-specific prevalence of hoarding and obsessive compulsive disorder: a population-based study. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatr. 2017;25(3):245–255. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2016.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough B.A., Casey L.M. Technological adjuncts to increase adherence to therapy: a review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2011;31(5):697–710. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. 2nd ed. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, New Jersey: 1988. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers P., Marks I.M., van Straten A., Cavanagh K., Gega L., Andersson G. Computer-aided psychotherapy for anxiety disorders: a meta-analytic review. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2009;38(2):66–82. doi: 10.1080/16506070802694776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert D., Tarnowski T., Gollwitzer M., Sieland B., Berking M. A transdiagnostic internet-based maintenance treatment enhances the stability of outcome after inpatient cognitive behavioral therapy: a randomized controlled trial. Psychother. Psychosom. 2013;82(4):246–256. doi: 10.1159/000345967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert D.D., Hannig W., Tarnowski T., Sieland B., Götzky B., Berking M. Web-based rehabilitation aftercare following inpatient psychosomatic treatment. Rehabilitation (Germany) 2013;52(3):164–172. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1345191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enander J., Andersson E., Mataix-Cols D., Lichtenstein L., Alström K., Andersson G.…Rück C. Therapist guided internet based cognitive behavioural therapy for body dysmorphic disorder: single blind randomised controlled trial. BMJ [Br. Med. J.] 2016;352 doi: 10.1136/bmj.i241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleig L., Pomp S., Schwarzer R., Lippke S. Promoting exercise maintenance: how interventions with booster sessions improve long-term rehabilitation outcomes. Rehabil. Psychol. 2013;58(4):323–333. doi: 10.1037/a0033885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost R.O., Hartl T.L. A cognitive-behavioral model of compulsive hoarding. Behav. Res. Ther. 1996;34(4):341–350. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(95)00071-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost R.O., Steketee G., Grisham J. Measurement of compulsive hoarding: saving inventory-revised. Behav. Res. Ther. 2004;42(10):1163–1182. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2003.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost R.O., Maxner S., Pekareva-Kochergina A. The effectiveness of a biblio-based support group for hoarding disorder. Behav. Res. Ther. 2011;49:628. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2011.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost R.O., Steketee G., Tolin D.F. Comorbidity in hoarding disorder. Depress. Anxiety. 2011;28(10):876–884. doi: 10.1002/da.20861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost R.O., Ruby D., Shuer L.J. The Buried in Treasures Workshop: waitlist control trial of facilitated support groups for hoarding. Behav. Res. Ther. 2012;50(11):661–667. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost R.O., Steketee G., Tolin D.F. vol. 8. 2012. Diagnosis and Assessment of Hoarding Disorder; pp. 219–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golkaramnay V., Bauer S., Haug S., Wolf M., Kordy H. The exploration of the effectiveness of group therapy through an internet chat as aftercare: a controlled naturalistic study. Psychother. Psychosom. 2007;76(4):219–225. doi: 10.1159/000101500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyder E., Hind D., Breckon J., Dimairo M., Minton J., Everson-Hock E.…Cooper C. A randomised controlled trial and cost-effectiveness evaluation of 'booster' interventions to sustain increases in physical activity in middle-aged adults in deprived urban neighbourhoods. Health Technol. Assess. 2014;18(13):1–209. doi: 10.3310/hta18130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grisham J.R., Steketee G., Frost R.O. Interpersonal problems and emotional intelligence in compulsive hoarding. Depress. Anxiety. 2008;25(9):E63–71. doi: 10.1002/da.20327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedman E. Therapist guided internet delivered cognitive behavioural therapy. British Medical Journal. 2014;348(mar10):2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holländare F., Johnsson S., Randestad M., Tillfors M., Carlbring P., Andersson G., Engström I. Randomized trial of internet-based relapse prevention for partially remitted depression. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2011;124(4):285–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath A.O., Del Re A.C., Flückiger C., Symonds D. Alliance in individual psychotherapy. Psychotherapy. 2011;48(1):9–16. doi: 10.1037/a0022186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iervolino A.C., Perroud N., Fullana M.A., Guipponi M., Cherkas L., Collier D.A., Mataix-Cols D. Prevalence and heritability of compulsive hoarding: a twin study. Am. J. Psychiatr. 2009;166(10):1156–1161. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08121789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemmeren L.L., van Schaik D.J.F., Riper H., Kleiboer A.M., Bosmans J.E., Smit J.H. Effectiveness of blended depression treatment for adults in specialised mental healthcare: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16(1) doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0818-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein B., Meyer D., Austin D., Kyrios M. Anxiety online - a virtual clinic: preliminary outcomes following completion of five fully automated treatment programs for anxiety disorders and symptoms. J. Med. Internet Res. 2011;13(4) doi: 10.2196/jmir.1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kordy H., Theis F., Wolf M. Modern information and communication technology in medical rehabilitation. Bundesgesundheitsbl. Gesundheitsforsch. Gesundheitsschutz. 2011;54(4):458–464. doi: 10.1007/s00103-011-1248-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyrios M., Nedeljkovic M., Moulding R., Klein B., Austin D., Meyer D., Ahern C. Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial of internet-based cognitive-behavioural therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder. (Study protocol) BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:209. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-14-209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecrubier Y., Sheehan D.V., Weiller E., Amorim P., Bonora I., Harnett Sheehan K.…Dunbar G. The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI). A short diagnostic structured interview: reliability and validity according to the CIDI. Eur. Psychiatry. 1997;12(5):224–231. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis C., Pearce J., Bisson J.I. Efficacy, cost-effectiveness and acceptability of self-help interventions for anxiety disorders: systematic review. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2012;200(1):15–21. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.084756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovibond S.H., Lovibond P.F. Second edition. Psychology Foundation of Australia; Sydney, NSW: 1995. Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales. [Google Scholar]

- Manber R., Simpson N.S., Bootzin R.R. A step towards stepped care: delivery of CBT-I with reduced clinician time. Sleep Med. Rev. 2015;19:3–5. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrone P., Knapp M., Proudfoot J., Ryden C., Cavanagh K., Shapiro D.…Tylee A. Cost-effectiveness of computerised cognitive-behavioural therapy for anxiety and depression in primary care: randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2004;185:55–62. doi: 10.1192/bjp.185.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay D., Todaro J.F., Neziroglu F., Yaryura-Tobias J.A. Evaluation of a naturalistic maintenance program in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder: a preliminary investigation. J. Anxiety Disord. 1996;10(3):211–217. [Google Scholar]

- Medley A.N., Capron D.W., Korte J.K., Schmidt N.B. Anxiety sensitivity: a potential vulnerability factor for compulsive hoarding. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2013;42(1):45–55. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2012.738242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mewton L., Smith J., Rossouw P., Andrews G. Current perspectives on internet delivered cognitive behavioral therapy for adults with anxiety and related disorders. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2014;2014:37–46. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S40879. (default) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulding R., Nedeljkovic M., Kyrios M., Osborne D., Mogan C. Short-term cognitive-behavioural group treatment for hoarding disorder: a naturalistic treatment outcome study. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2016 doi: 10.1002/cpp.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muroff J., Steketee G., Rasmussen J., Gibson A., Bratiotis C., Sorrentino C. Group cognitive and behavioral treatment for compulsive hoarding: a preliminary trial. Depress. Anxiety. 2009;26(7):634–640. doi: 10.1002/da.20591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muroff J., Steketee G., Himle J., Frost R. Delivery of internet treatment for compulsive hoarding (D.I.T.C.H.) Behav. Res. Ther. 2010;48(1):79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman M.G., Erickson T., Przeworski A., Dzus E. Self-help and minimal-contact therapies for anxiety disorders: is human contact necessary for therapeutic efficacy? J. Clin. Psychol. 2003;59(3):251. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norcross J.C.A. Oxford University Press; Cary: 2002. Psychotherapy Relationships That Work: Therapist Contributions and Responsiveness to Patients. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordsletten A.E., Fernández de la Cruz L., Pertusa A., Reichenberg A., Hatch S.L., Mataix-Cols D. The Structured Interview for Hoarding Disorder (SIHD): development, usage and further validation. J. Obsessive-Compulsive Relat. Disord. 2013;2(3):346–350. [Google Scholar]

- Nordsletten A.E., Reichenberg A., Hatch S.L., Fernández De La Cruz L., Pertusa A., Hotopf M., Mataix-Cols D. Epidemiology of hoarding disorder. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2013;203(6):445–452. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.130195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong C., Pang S., Sagayadevan V., Chong S.A., Subramaniam M. Functioning and quality of life in hoarding: a systematic review. J. Anxiety Disord. 2015;32(0):17–30. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmqvist B., Carlbring P., Andersson G. Internet-delivered treatments with or without therapist input: does the therapist factor have implications for efficacy and cost? (Report) Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 2007;7(3):291. doi: 10.1586/14737167.7.3.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phung P.J., Moulding R., Taylor J.K., Nedeljkovic M. Emotional regulation, attachment to possessions and hoarding symptoms. Scand. J. Psychol. 2015;56(5):573–581. doi: 10.1111/sjop.12239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska J.O., Norcross J.C. Stages of change. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. Train. 2001;38(4):443–448. [Google Scholar]

- Richards P., Simpson S. Beyond the therapeutic hour: an exploratory pilot study of using technology to enhance alliance and engagement within face-to-face psychotherapy. Br. J. Guid. Couns. 2015;43(1):57–93. [Google Scholar]

- Richards D., Richardson T., Timulak L., McElvaney J. The efficacy of internet-delivered treatment for generalized anxiety disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Internet Interv. 2015;2(3):272–282. [Google Scholar]

- Romijn G., Riper H., Kok R., Donker T., Goorden M., van Roijen L.H.…Koning J. Cost-effectiveness of blended vs. face-to-face cognitive behavioural therapy for severe anxiety disorders: study protocol of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15(1) doi: 10.1186/s12888-015-0697-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuels J.F., Bienvenu O.J., Grados M.A., Cullen B., Riddle M.A., Liang K.Y.…Nestadt G. Prevalence and correlates of hoarding behavior in a community-based sample. Behav. Res. Ther. 2008;46(7):836–844. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmalisch C.S., Bratiotis C., Muroff J. Processes in group cognitive and behavioral treatment for hoarding. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 2010;17(4):414–425. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan D.V., Lecrubier Y., Harnett Sheehan K., Janavs J., Weiller E., Keskiner A.…Dunbar G. The validity of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) according to the SCID-P and its reliability. Eur. Psychiatry. 1997;12(5):232–241. [Google Scholar]

- Spek V., Nyklicek I., Smits N., Cuijpers P., Riper H., Keyzer J., Pop V. Internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy for subthreshold depression in people over 50 years old: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Psychol. Med. 2007;37(12):1797–1806. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707000542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steketee G., Frost R. Compulsive hoarding and acquiring therapist guide. In: Frost R., editor. Treatments That Work. Oxford University Press; Oxford, USA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Steketee G., Frost R.O., Wincze J., Greene K.A.I., Douglass H. Group and individual treatment of compulsive hoarding: A pilot study. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2000;28(3):259–268. [Google Scholar]

- Steketee G., Frost R.O., Kyrios M. Cognitive aspects of compulsive hoarding. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2003;27(4):463–479. [Google Scholar]

- Timpano K.R., Buckner J.D., Richey J.A., Murphy D.L., Schmidt N.B. Exploration of anxiety sensitivity and distress tolerance as vulnerability factors for hoarding behaviors. Depress. Anxiety. 2009;26(4):343–353. doi: 10.1002/da.20469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timpano K., Keough M.E., Traeger L., Schmidt N. General life stress and hoarding: examining the role of emotional tolerance. Int. J. Cogn. Ther. 2011;4(3):263–279. [Google Scholar]

- Tolin D.F., Steketee G. 2007. Buried in Treasures Help for Compulsive Acquiring, Saving, and Hoarding. [Google Scholar]

- Tolin D.F., Frost R.O., Steketee G., Gray K.D., Fitch K.E. The economic and social burden of compulsive hoarding. Psychiatry Res. 2008;160(2):200–211. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolin D.F., Frost R.O., Steketee G., Muroff J. Cognitive behavioral therapy for hoarding disorder: a meta-analysis. Depress. Anxiety. 2015;32(3):158–166. doi: 10.1002/da.22327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton M.G., Abramowitz J.S., Fabricant L.E., Berman N.C., Franklin J.C. Is hoarding a symptom of obsessive-compulsive disorder? Int. J. Cogn. Ther. 2011;4(3):225–238. [Google Scholar]

- Whisman M.A. The efficacy of booster maintenance sessions in behavior therapy: review and methodological critique. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 1990;10(2):155–170. [Google Scholar]

- Wootton B.M. Remote cognitive-behavior therapy for obsessive-compulsive symptoms: A meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2016;43:103–113. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]