Abstract

Background

Cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBTi) is considered the standard treatment. The internet has proven to be a useful and successful tool of providing CBTi. However, few studies have investigated the possible effect of unguided internet-delivered CBTi (ICBTi) on comorbid psychological symptoms and fatigue.

Methods

Based on a randomized controlled trial, we investigated whether unguided ICBTi had an effect on comorbid psychological symptoms. Adults with insomnia (n = 181; 67% women; mean age 44.9 years [SD 13.0]) were randomized to ICBTi (n = 95) or to an online patient education condition (n = 86) for a nine-week period.

Results

The results from mixed linear modelling yielded medium to large between-group effect sizes from pre- to post-treatment for symptoms of anxiety or depression (d = −0.57; 95% CI = 0.79–0.35) and fatigue (d = 0.92; 95% CI = 1.22–0.62). The ICBTi group was reassessed at a 6-month non-randomized follow-up, and the completing participants had on the average a significant increase (from the post-assessment) on symptoms of anxiety or depression, while the reduction in symptoms of fatigue (on post-assessment) was maintained. However, due to high dropout attrition and no control group data, caution should be made regarding the long-term effects. In conclusion, the present findings show that unguided ICBTi positively influence comorbid symptoms in the short-term, thereby emphasizing the clinical relevance of unguided ICBTi.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02261272

Keywords: Cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia, Internet-based intervention, Fatigue, Depression, Anxiety

Highlights

-

•

In a randomized controlled trial, we investigated whether unguided ICBTi had an effect on comorbid psychological symptoms.

-

•

181 were randomized to ICBTi (n=95) or to an online patient education condition (n=86) for a nine-week period.

-

•

Results yielded medium to large effect sizes from pre- to post-treatment for symptoms of anxiety or depression

-

•

The present findings indicate that unguided ICBTi positively influence comorbid symptoms in the short-term.

1. Introduction

Insomnia is the most common sleep disorder and impairs quality of life for millions of individuals worldwide (Ohayon, 1997; Pallesen et al., 2001). Reduced daytime functioning is an important aspect of the insomnia diagnosis, as insomnia affects mood, social functioning, work, cognitive functioning, and often leads to fatigue (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Additionally, mental illnesses, such as depression and anxiety are commonly comorbid with insomnia (Ohayon, 2007; Sanchez-Ortuno and Edinger, 2012). Traditionally insomnia has been viewed as a symptom of mental illnesses, but there is a growing body of literature indicating that insomnia may represent an independent disorder that can worsen and cause mental problems (Harvey, 2001). For instance, the symptoms of insomnia often persist after the comorbid disorder has been successfully treated, and it has been argued that this emphasizes the necessity of a separate treatment that focuses mainly on the symptoms of insomnia (Harvey, 2001; Sanchez-Ortuno and Edinger, 2012). Today, cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBTi) is considered the gold standard treatment (Morin et al., 2006, Wilson et al., 2010). CBTi has shown good results in reducing insomnia symptoms (Okajima et al., 2011), and some studies have examined if CBTi yields similar improvements regarding comorbid psychological symptoms and disorders, such as depression and anxiety (e.g., Bélanger et al., 2016; Ho et al., 2015).

The prevalence of insomnia is steadily growing and the need for effective treatment is urgent (Pallesen et al., 2014). To date, the availability of CBTi is still insufficient, due to economic costs and lack of qualified personnel offering this treatment face-to-face (Edinger and Means, 2005). As a means of enhancing the availability of CBTi, internet-delivered CBTi (ICBTi) (e.g. Ritterband et al., 2009) has been developed and found to be very effective in improving patients' sleep (Cheng and Dizon, 2012; Zachariae et al., 2016). Research also indicates that ICBTi may improve patient's comorbid symptoms (Ye et al., 2015; Christensen et al., 2016). Ye et al. (2015) conducted a meta-analysis, which included ten qualified RCTs on Internet-based CBTi interventions. The analysis revealed overall positive results; the combined effect sizes for comorbid depression and anxiety were −0.36 and −0.35, respectively. An RCT from Australia (Christensen et al., 2016) also examined the effect of internet-based CBTi (SHUTi) on symptoms of depression in individuals with insomnia and sub-clinical depression. The results at six weeks and at six months indicated that the participants who received the SHUTi treatment (n = 574) had a significantly lower level of depression symptoms, compared to participants who used an internet-based placebo control program.

The Sleep Healthy Using the Internet (SHUTi) program is an example of a sophisticated online adaptation of CBTi which have shown significant results (Ritterband et al., 2009; Ritterband et al., 2012). In the first clinical trial of SHUTi (Ritterband et al., 2009), findings indicated that nearly three out of four patients were in remission six months after treatment, which is similar to what is typically found in face-to-face CBTi. Further, the results indicated that the SHUTi intervention reduced comorbid psychological symptoms (Thorndike et al., 2013).

In the current study, a Norwegian translated version of the SHUTi was used to examine whether the treatment would have similar effects outside English speaking countries. The preliminary results showed that the SHUTi treatment improved the participants' sleep overall (Hagatun et al., 2017). Based on the lack of knowledge about how such unguided interventions affect comorbid disorders, the aim of the present paper was to examine how the SHUTi intervention affected symptoms of psychological distress and fatigue.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and procedures

The study protocol was approved by the Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics in Western Norway (2012/1934 REK, South East B). Details of the study procedure are reported in another forthcoming paper (Hagatun et al., 2017), and therefore only briefly summarized here: Participants were recruited through the media, and completed an online screening before they went through a screening interview by phone. Inclusion criteria were: minimum 18 years old and meeting the diagnostic criteria for insomnia. Exclusion criteria were: night work, presence of another sleep disturbance or mental problem/disorder (e.g. moderate or severe depression) that might impair sleep. Included participants were randomly allocated to either SHUTi or a web-based patient education condition over 9 weeks. Participants in the SHUTi group were followed-up after 6 months.

2.2. Interventions

The SHUTi program is a fully automated interactive online self-help program (Ritterband et al., 2009), based on traditional face-to-face CBTi. SHUTi comprises six weekly online modules, including sleep hygiene, sleep restriction, stimulus control, and cognitive restructuring. The program is mainly based on informative text for the participants to read, and the treatment content, CBTi, is then elaborated and rehearsed through interactive exercises, quizzes, animations, video vignettes, and expert explanations. In addition, the participants are assigned homework for practicing the content taught in that week's core. An essential aspect of the SHUTi program is that it provides personalised treatment recommendations, which are automatically generated, based on the information that each participant registers through the online sleep diaries and questionnaires. More detailed descriptions of the SHUTi program have been published elsewhere (Ritterband et al., 2009; Thorndike et al., 2008).

The control intervention of the current study comprised a patient education web site, containing information meant to resemble the kind of information individuals with insomnia may receive when they visit a general practitioner concerning their insomnia symptoms (Sivertsen et al., 2010). At this site, the participants could read about the symptoms of insomnia, potential causal and maintaining factors, as well as suggestions for strategies to improve sleep, including simple sleep hygiene strategies, as well as some of the most basic behavioral recommendations used in stimulus control. Hence, the information is mainly based on the treatment principles of CBTi. Although there is some overlap between the patient education intervention and the SHUTi intervention, the two interventions are very different in terms of the share volume of the self-help material and the therapeutic approach; while interactivity and personalised feedback are key elements in the comprehensive self-help intervention in SHUTi, the information provided in the patient education intervention was brief and static. Hence, all information in the patient education intervention was presented as text, without any elements of interactivity or feedback, and took about 30 min to read through. The participants in the patient education group were offered access to ICBTi (SHUTi) after completing the first post-assessment (after nine weeks), albeit no further data were collected from these participants.

2.3. Measurements

Symptoms of anxiety and depression were measured by The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (Zigmond and Snaith, 1983), and the Chalder Fatigue Scale (Chalder et al., 1993) was used to measure physical and mental symptoms of fatigue at baseline, post treatment and the 6-month non-randomized follow-up. Only the total HADS score was used, as research indicate that the HADS subscales' ability to differentiate between depression and anxiety is suboptimal (Cosco et al., 2012).

2.4. Statistical analyses

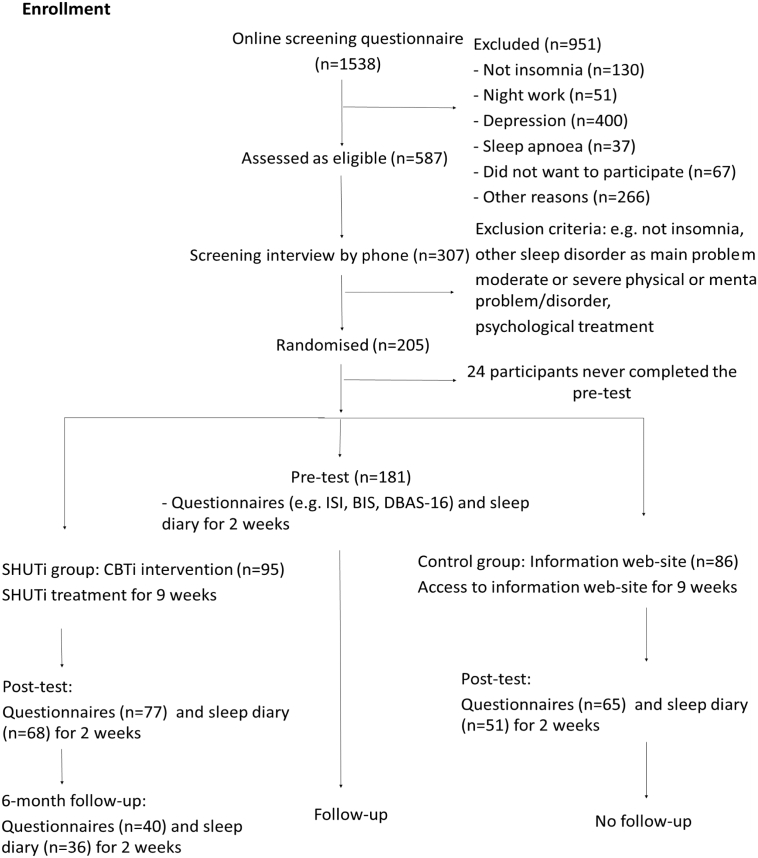

To examine the effect of the SHUTi program compared to the patient education website, a linear mixed model for repeated-measures analysis was performed using the intention to treat principle, such that all participants with baseline data were included in the analysis. In all, 24 of the randomized participants were not included in the analyses, as they never completed any questionnaire (see also Fig. 1). None of these 24 participants were aware of treatment allocation and none of them received any form of treatment. Not including these drop-outs in the analyses is therefore not considered a threat to the internal validity of the study. No constraints were imposed on the covariance structure for repeated measures (type = unstructured, R-matrix only). Mixed model analysis uses maximum likelihood estimation and can handle data that are missing at random (MAR) on dependent variables. Although there are no conclusive tests to prove the assumption of MAR, it is generally considered to be a more realistic assumption as compared to missing completely at random (MCAR). For the analysis, time (pre vs. post), group (SHUTi vs. control), and the interaction effect time x group were included in the model. A statistically significant (p < 0.05) interaction effect would indicate that the effect of time was different between the SHUTi and control group.

Fig. 1.

Participant flow.

An additional mixed model analysis was performed including data from 6-month follow-up of the SHUTi participants. For this purpose, time was modeled as a categorical variable, and backward difference coding was adopted to compare outcomes at post- vs. pre-assessment and 6-month follow-up vs. post-assessment. In this coding scheme, the mean of the dependent variable for one level of the categorical variable time is compared to the mean of the dependent variable for the prior adjacent level of time. For three time points, two parameters are thus estimated, and these represent the estimated mean difference of the dependent variable between post and pre, and between 6-month follow-up and post, respectively.

3. Results

In all, 181 adults with insomnia were included and allocated to SHUTi (n = 95) or the patient education group (n = 86).

3.1. Sample characteristics

There were no differences between the SHUTi and the patient education group on any baseline demographical characteristics. Mean age was 44.9 years (SD 13.0). The sample comprised more women (67%) than men, and the majority (66%) was married/living with a partner (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic information.

| Characteristic | SHUTi (n = 95) |

Patient education (n = 86) |

Total (n = 181) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 45.0 (12.4) | 44.8 (13.7) | 44.9 (13.0) |

| Gender (n) | |||

| Women | 64% (61) | 71% (61) | 67% (122) |

| Men | 36% (34) | 29% (25) | 33% (59) |

| BMIa, mean (SD) | 24.7 (4.0) | 24.1 (4.2) | 24.4 (4.1) |

| Marital status (n) | 46 | ||

| Married/partner | 64% (61) | 67% (58) | 66% (119) |

| Not married/no partner | 36% (34) | 33% (28) | 34% (62) |

| Education, y, mean (SD) | 16.3 (3.24) | 16.6 (2.71) | 16.4 (2.99) |

| Insomnia, duration | |||

| 3–11 months | 16% (15) | 14% (12) 21.0% (18) 33.7% (29) 30.2% (26) 12 | 15% (27) 21.0% (38) 34.3% (62) 28.7% (52) |

| 1–5 years | 24% (23) 34.7% (33) 27.8% (26) | 20% (17) | 22% (40) 21.0% (38) 34.3% (62) 28.7% (52) |

| 6–10 years | 34% (32) 34.7% (33) 27.8% (26) | 35% (30) 30.2% (26) | 34% (62) 21.0% (38) 34.3% (62) 28.7% (52) |

| >10 years | 26% (25) 34.7% (33) 27.8% (26) | 30% (26) 30.2% (26) | 28% (51) 21.0% (38) 34.3% (62) 28.7% (52) |

| Alcohol use (AUDIT-C)b, mean (SD) | 3.8 (1.7) | 3.5 (1.9) | 3.7 (1.8) |

| Smoking (n) | 8% (8) | 13% (11) | 11% (19) |

FTND = Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence.

BMI = Body Mass Index.

AUDIT-C = The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test.

3.2. Attrition

Questionnaires at post-assessment were not completed by 19 (20%) of the SHUTi participants and 24 (28%) of the control group participants (χ2(1181) = 1.56, p = 0.21). When comparing baseline characteristics of participants with missing data at post-treatment, only alcohol use was associated with missingness at follow-up. However, the correlations of alcohol use score with the outcome measures (symptoms of anxiety and depression, fatigue) were below 0.4 indicating that including this as an auxiliary variable in the mixed model analyses would have minimal impact (Enders, 2010). Attrition at 6-month follow-up was high as 59 (62%) of the SHUTi participants did not complete the questionnaire. Higher age was the only baseline characteristic that was associated with missingness at 6-month follow-up (t(67) = −2.06, p = 0.04), but also age was not included in the analyses due to weak correlations with the outcome variables.

3.3. Symptoms of anxiety or depression

Symptoms of anxiety or depression was significantly reduced in the SHUTi group (Meanpre = 9.72, Meanpost = 6.79, dwithin = 0.56; 95% CI = 0.73–0.39), and the improvement was significantly larger compared to the patient education group (dbetween = 0.57; 95% CI = 0.79–0.35) (Table 2). Among the completing SHUTi participants at the 6-month non-randomized follow-up, the treatment gains were slightly reduced (Mean6-month = 8.42), with effect size (6-month vs. post) dwithin = 0.30 (95% CI = 0.14–0.45). The difference between baseline and 6-month non-randomized follow-up trend towards borderline statistically significant (p = 0.06).

Table 2.

HADS and fatigue from pre-assessment and post-assessment for SHUTi participants and patient education participants.

| Sleep variable and time | SDpooled_pre | SHUTi |

Patient education |

Time × group effect |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (95% CI)a | dwithin (95% CI) | N | Mean (95% CI)a | dwithin (95%CI) | F | p-Value | dbetween (95% CI) | ||

| HADS | ||||||||||

| Pre-assessment | 5.21 | 95 | 9.72 (8.66, 10.77) | −0.56 (−0.73, −0.39) | 86 | 10.72 (9.61, 11.83) | 0.01 (−0.13, 0.15) | 23.05 | <0.001 | −0.57 (−0.79, −0.35) |

| Post-assessment | 76 | 6.79 (5.70, 7.88) | 62 | 10.79 (9.61, 11.97) | ||||||

| Fatigue | ||||||||||

| Pre-assessment | 5.75 | 95 | 18.90 (17.73, 20.06) | −1.04 (−1.30, −0.78) | 86 | 19.88 (18.66, 21.11) | −0.12 (−0.27, 0.03) | 36.62 | <0.001 | −0.92 (−1.22, −0.62) |

| Post-assessment | 68 | 12.91 (11.62, 14.12) | 64 | 19.22 (17.83, 20.61) | ||||||

Estimated marginal means from the mixed model analyses.

3.4. Fatigue

The average level of fatigue improved from pre- to post-treatment in the SHUTi group (Meanpre = 18.90, Meanpost = 12.91, dwithin = 1.04; 95% CI = 1.30–0.78), and was significantly greater than the patient education group (dbetween = −0.92; 95% CI = 1.22–0.62) (Table 2). Analyses of the 6-month follow-up data in the SHUTi group showed that the treatment effect was relatively stable among the completing participants (Mean6-month = 13.56), with effect size (6-month vs. post) dwithin = 0.13 (95% CI = 0.02–0.28) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Results at 6-month follow-up of SHUTi-participants.

| Estimated mean difference. (s.e.) | p-Value | SDpre | dwithin (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HADS | ||||

| Post. vs. pre | −2.93 (0.43) | <0.001 | 5.39 | −0.54 (−0.71, −0.37) |

| 6-months vs. post | 1.63 (0.61) | 0.01 | 0.30 (0.14, 0.45) | |

| 6-months vs. prea | −1.30 (0.68) | 0.06 | −0.24 (−0.48, 0.004) | |

| Fatigue | ||||

| Post. vs. pre | −6.03 (0.64) | <0.001 | 5.36 | −1.13 (−1.40, −0.86) |

| 6-months vs. post | −0.70 (0.67) | 0.31 | 0.13 (−0.02, 0.28) | |

| 6-months vs. prea | −5.34 (0.75) | <0.001 | −1.00 (−1.20, −0.80) | |

Note: The results from the 6-month follow-up are based on the SHUTi group only.

Based on an additional analysis with time coded as simple dummies.

4. Discussion

The findings from the current trial indicate that the SHUTi treatment had beneficial effects on psychological distress, in terms of symptoms of depression and anxiety, as well as daytime functioning, in terms of fatigue. Before treatment, both groups had an overall score on psychological distress (HADS-total) just above nine points, which is the recommended cut-off score for HADS-total (Kjærgaard et al., 2014). At the time of treatment completion, the SHUTi group scored below the cut-off, while the patient education group still had a mean score above cut-off. Hence, the SHUTi group improved significantly compared to the patient education group, indicating that the SHUTi intervention has a positive effect on level of psychological distress in patients with insomnia. Additionally, the level of fatigue was reduced significantly in the SHUTi group, compared to the patient education group.

Overall, the present findings regarding the effect of SHUTi on comorbid symptoms are in line with existing research indicating that CBT for insomnia also may lead to improvements in levels of comorbid symptoms of depression and anxiety in insomnia patients (Bélanger et al., 2016; Manber et al., 2008; Taylor et al., 2007). Moreover, the current results support previous research indicating that the effects of traditional CBTi on comorbid symptoms also applies to internet-based CBTi interventions (Christensen et al., 2016; Ye et al., 2015).

In terms of long-term efficacy, the overall results from the non-randomized 6-month assessment indicate that the beneficial effects of the treatment on comorbid psychological symptoms appears to be relatively long-lasting. One reason why symptoms of depression or anxiety seems to be returning somewhat at 6-month follow-up, may be because the SHUTi program is not directly aimed at symptoms of depression or anxiety. Nevertheless, the current trial revealed that the reduction in level of fatigue at the time of treatment completion (after nine weeks) was relatively stable at the 6-month follow-up. These findings extend previous trials exploring the efficacy of the SHUTi intervention on fatigue (e.g. Ritterband et al., 2012; Thorndike et al., 2013), with evidence of sustained effects beyond treatment completion.

Overall, the present study indicates that the efficacy of an unguided ICBTi treatment for insomnia goes beyond sleep outcomes; SHUTi improves comorbid symptoms as well, such as fatigue and symptoms of anxiety or depression. As many insomnia patients have such comorbid complaints, the present study supports the clinical relevance of an unguided ICBTi intervention. However, several limitations should be noted. The study only included individuals with mild symptoms of depression, which likely resulted in a ceiling effect and the results might have been even more substantive if those with greater levels of depression were included. On the other hand, inclusion of moderately or severely depressed patients could have decreased the effects of the treatment due to patients being too unwell to work with the materials. The participants were self-recruited; measures of fatigue and symptoms of depression or anxiety were based on self-report; and the dropout attrition rate was high at the non-randomized 6-month follow-up. A possible reason for the high dropout rate might be that beyond the automatic emails, no extra effort was made to obtain the follow up data. It should, however, be noted that available data from all participants were included in the analyses by means of LMM, which is known to provide valid estimates under the assumption of missing at random, and is superior to traditional methods for dealing with missing data (Enders, 2010). Some strengths should also be noted. There are some previous studies indicating that ICBTi treatments improve comorbid symptoms. However, the present study extends prior results by using an unguided treatment program, and having an active control group. Also, this is among the few studies of unguided ICBTi outside an English/US setting.

There is still a need for further studies to gain more in depth knowledge about the clinical efficacy of such interventions. Future studies should consider including patients with more severe symptoms of mental illnesses in their samples. In addition, there is a need for more studies with longer follow-up assessments with control groups, in order to gain further knowledge of the long-term durability of ICBTi.

Abbreviations

Conflict of interest

LMR and FPT report having part equity ownership in BeHealth Solutions, LLC, a company developing and making available products (incl. the SHUTi program) related to the research reported in this publication. The remaining authors report that they have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Author contributions

Author SH drafted the manuscript and SH and ORFS conducted the statistical analyses. Authors LMR, FPT, BS, ØV, and TN were responsible for conception and design of the study, and BS, OEH, and TN obtained funding. All authors gave critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Funding information

The study was funded by Norwegian Extra Foundation for Health and Rehabilitation (No 2013/2/0029), the Meltzer Research Fund, the Norwegian Institute of Public Health, the Norwegian Research Council (project number 239985).

References

- American Psychiatric Association . American Psychiatric Association; Washington, D. C.: 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-V. [Google Scholar]

- Bélanger L., Harvey A.G., Fortier-Brochu É. Impact of comorbid anxiety and depressive disorders on treatment response to cognitive behavior therapy for insomnia. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2016;84:659–667. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalder T., Berelowitz G., Pawlikowska T. Development of a fatigue scale. J. Psychosom. Res. 1993;37:147–153. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(93)90081-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S.K., Dizon J. Computerised cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychother. Psychosom. 2012;81:206–216. doi: 10.1159/000335379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen H., Batterham P.J., Gosling J.A. Effectiveness of an online insomnia program (SHUTi) for prevention of depressive episodes (the GoodNight study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. Psychiatry. 2016;3:333–341. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00536-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosco T.D., Doyle F., Ward M., Mcgee H. Latent structure of the Hospital Anxiety And Depression Scale: a 10-year systematic review. J. Psychosom. Res. 2012;72:180–184. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edinger J.D., Means M.K. Cognitive–behavioral therapy for primary insomnia. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2005;25:539–558. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders C.K. The Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2010. Applied Missing Data Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Hagatun S., Vedaa Ø., Nordgreen T. The short-term efficacy of an unguided internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia: a randomized controlled trial with a 6-month non-randomized follow-up. Behav. Sleep Med. 2017:1–23. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2017.1301941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey A.G. Insomnia: symptom or a diagnosis? Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2001;21:1037–1059. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(00)00083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho F.Y.-Y., Chung K.-F., Yeung W.-F. Self-help cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sleep Med. Rev. 2015;19:17–28. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2014.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjærgaard M., Arfwedson Wang C.E., Waterloo K., Jorde R. A study of the psychometric properties of the Beck depression inventory-II, the Montgomery and Åsberg depression rating scale, and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale in a sample from a healthy population. Scand. J. Psychol. 2014;55:83–89. doi: 10.1111/sjop.12090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manber R., Edinger J., Gress J., San Pedro-Salcedo M., Kuo T., Kalista T. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia enhances depression outcome in patients with comorbid major depressive disorder and insomnia. Sleep. 2008;31:489–495. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.4.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin C.M., Bootzin R.R., Buysse D.J., Edinger J.D., Espie C.A., Lichstein K.L. Psychological and behavioral treatment of insomnia:update of the recent evidence (1998–2004) Sleep. 2006;29:1398–1414. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.11.1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohayon M.M. Prevalence of DSM-IV diagnostic criteria of insomnia: distinguishing insomnia related to mental disorders from sleep disorders. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1997;31:333–346. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(97)00002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohayon M.M. Prevalence and comorbidity of sleep disorders in general population. Rev. Prat. 2007;57:1521–1528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okajima I., Komada Y., Inoue Y. A meta-analysis on the treatment effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy for primary insomnia. Sleep Biol. Rhythm. 2011;9:24–34. [Google Scholar]

- Pallesen S., Nordhus I.H., Nielsen G.H. Prevalence of insomnia in the adult Norwegian population. Sleep. 2001;24:771–779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallesen S., Sivertsen B., Nordhus I.H., Bjorvatn B. A 10-year trend of insomnia prevalence in the adult Norwegian population. Sleep Med. 2014;15:173–179. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2013.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritterband L.M., Thorndike F.P., Gonder-Frederick L.A. Efficacy of an internet-based behavioral intervention for adults with insomnia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2009;66:692–698. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritterband L.M., Bailey E.T., Thorndike F.P., Lord H.R., Farrell-Carnahan L., Baum L.D. Initial evaluation of an internet intervention to improve the sleep of cancer survivors with insomnia. Psycho-Oncology. 2012;21:695–705. doi: 10.1002/pon.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Ortuno M.M., Edinger J.D. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for the management of insomnia comorbid with mental disorders. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2012;14:519–528. doi: 10.1007/s11920-012-0312-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivertsen B., Nordhus I.H., Bjorvatn B., Pallesen S. Sleep problems in general practice: a national survey of assessment and treatment routines of general practitioners in Norway. J. Sleep Res. 2010;19:36–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2009.00769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor D.J., Lichstein K.L., Weinstock J., Sanford S., Temple J.R. A pilot study of cognitive-behavioral therapy of insomnia in people with mild depression. Behav. Ther. 2007;38:49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorndike F.P., Saylor D.K., Bailey E.T., Gonder-Frederick L.A., Morin C.M., Ritterband L.M. Development and perceived utility and impact of an internet intervention for insomnia. E-J. Appl. Psychol. 2008;4:32–42. doi: 10.7790/ejap.v4i2.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorndike F.P., Ritterband L.M., Gonder-Frederick L.A., Lord H.R., Ingersoll K.S., Morin C.M. A randomized controlled trial of an internet intervention for adults with insomnia: effects on comorbid psychological and fatigue symptoms. J. Clin. Psychol. 2013;69:1078–1093. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson S.J., Nutt D.J., Alford C. British Association for Psychopharmacology consensus statement on evidence-based treatment of insomnia, parasomnias and circadian rhythm disorders. J. Psychopharmacol. 2010;24(11):1577–1601. doi: 10.1177/0269881110379307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Y.-Y., Zhang Y.-F., Chen J. Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (ICBT-i) improves comorbid anxiety and depression—a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachariae R., Lyby M.S., Ritterband L.M., O'toole M.S. Efficacy of internet-delivered cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia – a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sleep Med. Rev. 2016;30:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2015.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond A.S., Snaith R.P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]