Abstract

Metastatic disease is the primary cause of death of patients with lung cancer, but the mouse models of lung adenocarcinoma do not accurately recapitulate the tumor microenvironment or metastatic disease observed in patients. In this study, we conditionally deleted E-cadherin in an autochthonous lung adenocarcinoma mouse model driven by activated oncogenic Kras and p53 loss. Loss of E-cadherin significantly accelerated lung adenocarcinoma progression and decreased survival of the mice. Kras;p53;E-cadherin mice had a 41% lung tumor burden, invasive grade 4 tumors, and a desmoplastic stroma just 8 weeks after tumor initiation. One hundred percent of the mice developed local metastases to the lymph nodes or chest wall, and 38% developed distant metastases to the liver or kidney. Lung adenocarcinoma cancer cell lines derived from these tumors also had high migratory rates. These studies demonstrate that the Kras;p53;E-cadherin mouse model better emulates the tumor microenvironment and metastases observed in patients with lung adenocarcinoma than previous models and may therefore be useful for studying metastasis and testing new lung cancer treatments in vivo.

Keywords: E-cadherin, Kras, metastasis, non–small cell lung cancer, p53

Clinical Relevance

These studies report a new mouse model of lung cancer that better emulates the tumor microenvironment and metastases observed in human lung adenocarcinoma patients. This mouse model may be useful for studying metastasis and testing new lung cancer treatments in vivo.

The majority of cancer-related deaths are caused by metastases, and lung cancer remains the leading cause of death from cancer worldwide, in large part because of its ability to aggressively metastasize. The surgeries and therapies used to treat lung tumors rarely prevent metastatic disease, and the average 5-year survival rate for non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is a dismal 17% (1). Very little is known about how lung tumor cells spread, and there is a scarcity of experimental systems to study metastatic lung cancer cells. New mouse models, which better recapitulate the high rates of metastatic disease observed in patients, need to be developed to improve understanding of metastatic lung cancer and combat this deadly disease.

There are several mouse models of lung adenocarcinoma, a type of NSCLC that accounts for 40% of total lung cancers, driven by activated oncogenic Kras and/or p53 loss. Adenomas and early-stage adenocarcinomas develop in Lox-Stop-Lox-KrasG12D (Kras) mice after adenovirus-expressing Cre recombinase (AdCre) is delivered to the lungs, but none of these mice develop metastases (2, 3). When p53flox/flox (p53) mice are crossed with these Kras mice, advanced-stage lung adenocarcinomas develop in the resulting Kras;p53 animals after lung AdCre administration (2). Some Kras;p53 tumors exhibit a desmoplastic stroma, and approximately 50% of Kras;p53 mice get metastases, most commonly to the mediastinal lymph nodes, a common site for metastases in patients with lung cancer (3).

E-cadherin is a cell–cell adhesion transmembrane protein that functions to organize the epithelium by strengthening intercellular adhesions and maintaining cell polarity. Loss of E-cadherin expression is associated with translocation of β-catenin to the nucleus and subsequent transcription of target proteins and the epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) (4). During EMT, epithelial cells lose their intercellular contacts and become motile, invasive, and thus metastatic. Reduced or absent NSCLC tumor E-cadherin expression is associated with an increased risk of developing metastases and unfavorable overall survival (5–8), indicating that loss of E-cadherin is correlated with tumor progression and poor patient prognosis. E-cadherin loss is also associated with worse survival specifically in lung adenocarcinomas (9–11).

In this study, we conditionally deleted E-cadherin in Kras;p53 murine tumors to generate Kras;p53;E-cadherin mice to determine if E-cadherin loss would accelerate lung adenocarcinoma progression and metastasis. We chose this model system because it is highly likely that E-cadherin is lost in a subset of human lung adenocarcinomas driven by oncogenic Kras and p53 loss. An average of 36% of lung adenocarcinomas have negative or low E-cadherin expression (9–11), approximately 27% have oncogenic Kras mutations, and 50% have p53 mutations or loss of expression (12). Loss of E-cadherin significantly decreased the survival of the mice. Tumors from Kras;p53;E-cadherin mice displayed higher rates of proliferation, greater amounts of desmoplastic stroma, and greater numbers of local metastases than Kras;p53 lung tumors. E-cadherin loss also promoted migration of lung adenocarcinoma cancer cell lines derived from these tumors. Our work demonstrates that this Kras;p53;E-cadherin mouse model better emulates the tumor microenvironment and metastases observed in patients with lung adenocarcinoma and may be useful in studying the mechanisms of metastasis and testing novel preclinical therapeutics.

Methods

Mice and Histology

All animal studies were approved by the Children’s Hospital Boston Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Lox-Stop-Lox-KrasG12D;p53flox/flox (Kras;p53, 129/C57BL/6) (3) and E-cadherinflox/flox (E-cad, C57BL/6) (13) mice were heterozygous for Kras and homozygous for p53 and E-cadherin alleles. Six- to 8-week-old male and female Kras;p53 (129/C57BL/6) and Kras;p53;E-cadherin (129/C57BL/6) mice were infected with 2.5 × 107 plaque-forming units of AdCre (University of Iowa Gene Transfer Vector Core) intranasally as previously described (14), and mice were killed 8–18 weeks after infections or when appearing moribund. Survival curves were generated, and a log-rank (Mantel-Cox) statistical test was performed. Standard procedures were used to harvest and fix organs. Lung, liver, kidney, lymph nodes, and chest wall were dissected from the animals, and tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) in accordance with standard procedures and analyzed for tumors by at least two investigators, including a pathologist with expertise in mouse lung cancer (R.T.B.). Contingency table chi-square analysis was performed for the percentages of mice of each genotype with local and distant metastases. Quantification of lung tumor nodules was performed by scanning H&E-stained lung sections and using ImageJ software (NIH) to calculate tumor burden (tumor area divided by total lung area). Quantification of the number of lung tumors and metastases was performed by a pathologist (R.T.B.) by counting the number of tumors per H&E-stained lung section from each animal. The grade of each tumor was blindly scored by a pathologist (R.T.B.) as described in the Results section. Cochran-Armitage tests were performed for tumor grade percentage statistical analysis. Masson’s trichrome staining was performed with a standard procedure.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry for E-cadherin, Ki-67, Nkx2-1, cleaved caspase-3, and CD34 was performed; sections were blindly reviewed by a pathologist (R.T.B.); and Cochran-Armitage tests were performed for immunohistochemistry score statistical analyses for each tumor grade. See the data supplement for further details.

qRT-PCR Gene Expression Analysis

RNA was extracted using the Absolutely RNA Microprep Kit (Agilent Technologies). cDNA was made using the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and analyzed using TaqMan assays (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for mouse E-cadherin (Mm01247357_m1; Thermo Fisher Scientific) with a StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and software as per the manufacturer’s recommendations. Mouse Gapdh was used as an endogenous control for normalization (4352339E; Thermo Fisher Scientific).

In Vitro Assays

See the data supplement for details on cell line generation as well as additional details of migration assays. All cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 media. Migration assays were performed with 24-well Transwell plates according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Corning).

Statistics

Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t tests and/or ANOVA were performed unless otherwise noted. The Prism (GraphPad Software), Excel (Microsoft), and Mstat (Mstat Software, McArdle Laboratory for Cancer Research, University of Wisconsin–Madison) software programs were used for graphing and statistical analyses. All experiments were performed independently at least three times, and pooled data are represented by the mean and SEM.

Results

Loss of E-Cadherin in Kras;p53 Lung Tumors Decreases Survival

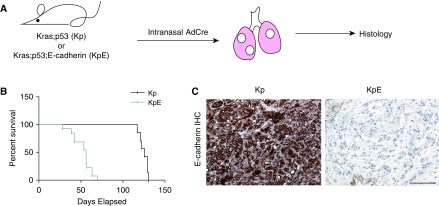

We first aimed to directly test if loss of E-cadherin in endogenous lung tumors would accelerate lung tumor progression and/or metastasis rates. Kras;p53 animals were bred with mice containing conditional E-cadherin–knockout alleles (E-cadherinflox/flox) (13) to generate Kras;p53;E-cadherin mice. Kras;p53 and Kras;p53;E-cadherin mice were infected intranasally with AdCre adenovirus and killed when they were moribund (Figure 1A). Kras;p53 mice survived an average of 17.8 weeks after AdCre delivery (Figure 1B). They lived significantly longer than the Kras; p53;E-cadherin mice (P < 0.01), which survived only an average of 7.5 weeks after administration of AdCre (Figure 1B). Immunohistochemistry confirmed that E-cadherin was knocked out in the lung tumors of the Kras;p53;E-cadherin mice (Figure 1C). These studies demonstrate that loss of expression of E-cadherin in the Kras;p53 murine lung tumors dramatically reduced survival.

Figure 1.

Deletion of E-cadherin in murine Kras;p53 (Kp) lung adenocarcinomas decreases survival. (A) Strategy to compare Kp and Kras;p53;E-cadherin (KpE) mouse lung tumors. (B) Survival curves of Kp (n = 7) and KpE (n = 13) mice after adenovirus-expressing Cre recombinase (AdCre) intranasal infections. P < 0.01. (C) Representative E-cadherin immunohistochemistry of the lung tumors from Kp (n = 6) and KpE (n = 8) mice 18 and 8 weeks after AdCre infection, respectively. Scale bars: 100 μm. IHC = immunohistochemical.

Loss of E-Cadherin in Kras;p53 Lung Tumors Increases Tumor Progression

To determine how lung tumor E-cadherin loss decreased survival, the histopathology of tumors from Kras;p53 and Kras;p53;E-cadherin mice 8 weeks after AdCre infection and Kras;p53 mice 18 weeks after AdCre infection were studied (see Figure E1A in the data supplement). First, the lung tumor burden, defined as the percentage of the total lung area filled with tumors, was measured. Strikingly, 8 weeks after AdCre infection, the lungs from the Kras;p53 mice contained an average tumor burden of 2%, whereas lungs from the Kras;p53;E-cadherin mice had a significantly higher average tumor burden of 41% (P < 0.01) (Figure 2A). There was no significant difference between the lung tumor burdens of Kras; p53;E-cadherin animals (41%) and those of Kras;p53 animals (34%) 8 and 18 weeks post-AdCre infection, respectively. Interestingly, at these time points, Kras;p53;E-cadherin and Kras;p53 mice had a significantly different number of tumors, with an average of 8.6 and 76.9 tumors per mouse, respectively (P < 0.01) (Figure 2B). This may be because the borders of the more advanced Kras;p53;E-cadherin tumors were not as well defined or because the Kras;p53;E-cadherin tumors were larger than the Kras;p53 tumors. Kras;p53 animals 8 weeks after AdCre infection had an average of 4.2 tumors per mouse (Figure 2B). These results demonstrate that it took an additional 10 weeks for the lungs from Kras;p53 animals to reach the same tumor burden as those from the Kras;p53;E-cadherin animals.

Figure 2.

KpE lung tumors are more advanced and desmoplastic than Kp lung tumors. (A) Quantification of lung tumor burden of Kp (n = 5) and KpE (n = 13) mice at 8 weeks after AdCre infection and Kp (n = 7) mice at 18 weeks after AdCre infection. (B) Average number of lung tumors of the mice analyzed in A. (C) Quantification of the highest-grade tumor of the mice analyzed in A. (D) Average number of invasive grade 4 lung tumors of the mice analyzed in A. (E) Representative trichrome staining of grade 4 lung tumors from KpE (n = 5) mice at 8 weeks after AdCre infection and Kp (n = 6) mice at 18 weeks after AdCre infection. Scale bars: 100 μm. (F) Quantification of the amount of Trichrome blue collagen staining from the tumors analyzed in D. All error bars represent mean ± SEM. *P < 0.01.

Next, the grade of each lung tumor was blindly scored by a pathologist, and the highest-grade lung tumor from each mouse was determined. Briefly, grade 1 tumors were uniform with normal nuclei; grade 2 tumors were uniform but had enlarged nuclei and prominent nucleoli; grade 3 tumors had enlarged cells with pleomorphic nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and nuclear molding; and grade 4 tumors had very large, pleomorphic nuclei with a high degree of nuclear atypia, giant multinucleated cells, and invasion into the blood or lymphatic vessels or through the basement membrane (14) (Figure E1B). Lung tumor grades from Kras;p53 mice were significantly less advanced than those from Kras;p53;E-cadherin mice 8 weeks after AdCre infection (P < 0.01) (Figure 2C). Whereas 20%, 60%, and 20% of the Kras;p53 mice contained at least one grade 1, 2, and 3 tumor, respectively, 100% of the Kras;p53;E-cadherin mice had at least one invasive grade 4 tumor (Figure 2C), indicating that all of the Kras;p53;E-cadherin mice had the potential to develop a metastasis. The majority of tumors of the Kras;p53 mice at 8 weeks, Kras;p53;E-cadherin mice at 8 weeks, and Kras;p53 mice at 18 weeks were grade 2, 4, and 3, respectively (Figure E1C), showing that Kras;p53;E-cadherin mice had the most advanced tumors. In fact, Kras;p53;E-cadherin animals had an average of 7.8 grade 4 tumors per mouse (Figure 2D). Kras;p53 mice 18 weeks post-AdCre had lung tumor grades similar to those of Kras;p53;E-cadherin mice 8 weeks after AdCre delivery. Fourteen percent and 86% of these Kras;p53 mice developed grade 3 and grade 4 tumors, respectively (Figure 2C), and the animals had an average of 1.7 grade 4 tumors per mouse (Figure 2D). These results demonstrate that loss of E-cadherin significantly and swiftly accelerated lung tumor progression.

Next, the amount of desmoplasia, which is the reactive fibronectin extracellular matrix (ECM) found in grade 4 murine lung adenocarcinomas, was measured by staining the tumors with Masson’s trichrome, which stains nuclei black; cytoplasm, muscle, and erythrocytes red; and collagen blue (Figure 2E). An average of 59% of the tumors from the Kras;p53;E-cadherin animals 8 weeks after AdCre infection stained positive for collagen, whereas only 5% of the tumors from Kras;p53 animals 18 weeks after AdCre infection were positive (P < 0.01) (Figure 2F). This shows that E-cadherin loss significantly enhanced the amount of desmoplastic stroma in the lung tumors, even in matched grade 4 tumors from the Kras;p53 and Kras;p53;E-cadherin mice. These large regions of desmoplasia may also have made the Kras;p53;E-cadherin tumor borders difficult to distinguish.

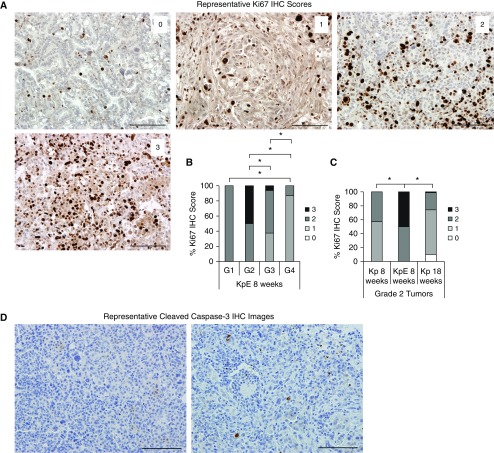

To investigate the mechanism by which the Kras;p53;E-cadherin lung tumors advanced so quickly, tumors from both genotypes of animals were stained for markers of proliferation, apoptosis, and angiogenesis and blindly scored by a pathologist. Lung tumors were first stained for Ki-67, a marker of proliferation, and scored on a 0–3 scale, with a score of 0 indicating absent staining and a score of 3 indicating a strong staining intensity (Figures 3A and E2A). The Ki-67 proliferative score of the Kras;p53;E-cadherin tumors significantly decreased as the tumors advanced: Grade 1 tumors had significantly higher scores than grade 4 tumors; grade 2 tumors had significantly higher scores than grades 3 and 4 tumors; and grade 3 tumors had significantly higher scores than grade 4 tumors (P < 0.03) (Figure 3B). Although the Kras;p53;E-cadherin tumors proliferated less as they progressed, there were no differences in Ki-67 staining scores between the grades 1–4 tumors in the Kras;p53 mice at 8 or 18 weeks post-AdCre (Figure E2A). Comparisons between the genotypes revealed that grade 2 Kras;p53;E-cadherin tumors were more proliferative than the Kras;p53 tumors at both 8 and 18 weeks after AdCre (P < 0.01) (Figure 3C). Although these results suggest that the early-grade Kras;p53;E-cadherin lung tumors may be highly proliferative and contribute to the rapid tumor progression observed in these mice, it must be noted that the grades 1 and 2 tumors still express E-cadherin, as described below (Figure 4D). Changes in the microenvironment may therefore be affecting the proliferation of these early-grade tumors. For example, the proliferation of fibroblasts and dense deposition of ECM that occur during desmoplasia have been shown to promote tumor growth through degradation of ECM components and subsequent release of growth factors normally sequestered in the ECM (15). Lung tumors were next stained for cleaved caspase 3, a marker of apoptosis. Lung tumors from both groups of animals at all time points had only sparse cleaved caspase-3–positive cells (Figure 3D). These slides were unable to be scored by a pathologist owing to the very low number of positive cells, indicating that loss of E-cadherin did not affect tumor apoptosis rates.

Figure 3.

KpE lung tumors have increased and equal numbers of Ki-67–positive and caspase-3–positive cells, respectively, compared with Kp lung tumors. (A) Representative images of Ki-67 IHC staining scores of lung tumors. Scale bars: 100 μm. (B) Quantification of the percentage of Ki-67–positive lung tumor cells from KpE mice (n = 5, with totals of 1, 10, 16, and 23 grades 1, 2, 3, and 4 [G1, G2, G3, and G4] tumors analyzed, respectively) at 8 weeks after AdCre infection. *P < 0.05. (C) Quantification of the percentage of Ki-67–positive lung tumor cells from Kp (n = 5, with a total of 21 grade 2 tumors analyzed) and KpE (n = 5, with a total of 10 grade 2 tumors analyzed) mice at 8 weeks after AdCre infection and Kp (n = 5, with a total of 178 grade 2 tumors analyzed) mice at 18 weeks after AdCre infection. *P < 0.05. (D) Representative cleaved caspase 3 IHC staining of lung tumors. Scale bars: 100 μm.

Figure 4.

KpE lung tumors have equal and decreased numbers of CD34-positive and E-cadherin–positive cells, respectively, compared with Kp lung tumors. (A) Representative images of CD34 IHC staining scores of lung tumors. Scale bars: 100 μm. (B) Quantification of the percentage of CD34-positive lung tumor cells from Kp (n = 5, with a total of 10 grade 2 tumors analyzed) and KpE (n = 3, with a total of 6 grade 2 tumors analyzed) mice at 8 weeks after AdCre infection and Kp (n = 5, with a total of 144 grade 2 tumors analyzed) mice at 18 weeks after AdCre infection. (C) Representative images of E-cadherin IHC staining scores of lung tumors. Scale bars: 100 μm. (D) Quantification of the percentage of E-cadherin–positive lung tumor cells from KpE mice (n = 8, with totals of 11, 4, 38, and 48 grades 1, 2, 3, and 4 tumors analyzed, respectively) at 8 weeks after AdCre infection. *P < 0.04.

Lung tumors were also stained for CD34, a marker of blood vessel endothelial cells, and scored on a 0–2 scale, with a score of 0 indicating an absence of staining and a score of 2 indicating a strong staining intensity (Figures 4A and E2B). There were no differences in CD34 staining scores between the tumor grades of each genotype and AdCre time point (Figure E2B). The grade 2 Kras;p53 tumors at 8 weeks post-AdCre infection had significantly fewer CD34-positive cells than the Kras;p53;E-cadherin and Kras;p53 tumors at 8 and 18 weeks after AdCre infection, respectively (P < 0.04) (Figure 4B). It therefore took an additional 10 weeks for the grade 2 lung tumors from the Kras;p53 animals to exhibit the same number of blood vessels as the Kras;p53;E-cadherin animals. However, the fact that there were no differences in CD34 scores between grade 1, 3, or 4 tumors among the groups of animals (Figure E2B) indicates that loss of E-cadherin did not robustly affect angiogenesis.

Lung tumors were also stained for E-cadherin and scored on a 0–3 scale, with a score of 0 indicating an absence of staining and a score of 3 indicating a strong staining intensity (Figures 4C and E2C). As expected, grades 3 and 4 tumors from Kras;p53;E-cadherin mice showed virtually no E-cadherin expression, suggesting that loss of E-cadherin leads to growth of the grades 3 and 4 tumors; however, 100% of grades 1and 2 tumors had E-cadherin expression (P < 0.01) (Figure 4D). This mostly likely indicates that the tumor recombination frequency of the E-cadherin allele is not 100%, so some of the grades 1 and 2 tumors may simply be Kras or Kras;p53 lesions. In support of this hypothesis, it has been reported that only 80% of tumors from Kras;p53 mice have recombination of the floxed p53 allele (3). Notably, grade 4 Kras;p53 tumors all expressed some level of E-cadherin, indicating that there was patchy but not whole tumor loss of E-cadherin in these tumors (Figure E2C).

Lung tumors were finally stained for Nkx2-1, a dual-function lineage transcription factor, and scored on a 0–4 scale, with a score of 0 indicating an absence of staining and a score of 4 indicating a strong staining intensity (Figure E3A). Nkx2-1 expression was lower in higher-grade Kras;p53 tumors (P < 0.01) (Figure E3B), as previously shown (16). There was also a trend of grade 4 Kras;p53;E-cadherin tumors having lower Nkx2-1 expression, but this difference was not statistically significant (Figure E3B). In addition, grade 4 Kras;p53 tumors had significantly lower Nkx2-1 expression than grade 4 Kras;p53;E-cadherin tumors (P < 0.01) (Figure E3B). Nkx2-1 downregulation may therefore contribute to loss of differentiation and increased metastases in both models (16), but reduced Nkx2-1 expression may be less crucial when E-cadherin expression is already lost.

Loss of E-Cadherin in Kras;p53 Lung Tumors Increases Metastasis

The metastases from the Kras;p53 and Kras;p53;E-cadherin lung tumors were next compared. Histology revealed metastases in the lymph nodes, liver, and kidney (Figure E4A). Whereas no Kras;p53 mice had any metastases 8 weeks after AdCre infection, 100% of Kras;p53;E-cadherin animals had local metastases to the lymph nodes or chest wall (P < 0.01), and 38% had distinct metastases to the liver or kidney (Figure 5A). Seventy-one percent and 14% of Kras;p53 mice developed local and distant metastases, respectively, 18 weeks after AdCre infection. There was no significant difference in metastasis rates between Kras;p53;E-cadherin mice 8 weeks post-AdCre infection and Kras;p53 18 weeks after AdCre infection (Figure 5A), indicating that it took an additional 10 weeks for the lung tumors from Kras;p53 animals to metastasize to the same degree as those from the Kras;p53;E-cadherin animals. However, Kras;p53;E-cadherin mice had an average of 6.5 local metastases per mouse, which was significantly higher than the average of 1.3 local metastases seen in the Kras;p53 animals at these time points (P < 0.01) (Figure 5B). All the lymph node metastases from Kras;p53 animals contained well-differentiated epithelial cells with high E-cadherin expression and little stroma, whereas the lymph node metastases from the Kras;p53;E-cadherin mice contained large areas of stroma with no E-cadherin expression (Figures E4B and E4C). The average number of distant metastases and the average size of both the local and distant metastases were similar between the genotypes (Figures 5C–5E). These results indicated that loss of E-cadherin in the Kras;p53 lung tumors significantly accelerated metastasis.

Figure 5.

Deletion of E-cadherin in Kp lung tumors promotes metastasis. (A) Percentage of Kp (n = 5) and KpE (n = 8) mice at 8 weeks after adenovirus-expressing Cre recombinase infection and Kp (n = 7) mice at 18 weeks after adenovirus-expressing Cre recombinase infection with local metastases to the lymph nodes or chest wall and distant metastases to the liver or kidney. (B) The average number of local metastases per mouse analyzed in A. (C) The average number of distant metastases per mouse analyzed in A. (D) The average size of local metastases per mouse analyzed in A. (E) The average size of distant metastases analyzed in A. All error bars represent mean ± SEM. *P < 0.01.

Finally, cell lines from Kras;p53 and Kras;p53;E-cadherin primary lung tumors were generated and characterized. Two cell lines derived from primary Kras;p53;E-cadherin lung tumors (Ecad-1 and Ecad-2) expressed 35-fold less E-cadherin transcript than the two cell lines derived from Kras;p53 primary lung tumors (CK1750 and SC241) (Figure 6A). Migration assays showed that Kras;p53;E-cadherin lung tumor cell lines were 2.7-fold more migratory than the Kras;p53 cell lines (Figure 6B). Importantly, proliferation was not significantly different between the Kras;p53 and Kras;p53;E-cadherin cell lines at 24 hours (Figure 6C), confirming that differences in migration rates were not attributable to altered proliferation. These studies demonstrate that loss of E-cadherin influences the migration step of the metastatic cascade.

Figure 6.

Loss of E-cadherin increases lung adenocarcinoma cell line migration. (A) qPCR analysis of E-cadherin expression of cell lines from Kp tumors (CK1750, SC241) or KpE tumors (Ecad-1, Ecad-2). n = 3. (B) Transwell assays showing relative migration of Kp cell lines (CK1750, SC241) and KpE cell lines (Ecad-1, Ecad-2) toward media supplemented with 10% FBS. n = 8. (C) Relative proliferation assays comparing Kp cell lines (CK1750, SC241) and KpE cell lines (Ecad-1, Ecad-2) using CellTiter-Glo viability assays (Promega) 24 hours after plating. n = 8. All error bars represent mean ± SEM. *P < 0.02; **P < 0.04.

Discussion

Our studies show that loss of E-cadherin accelerates lung adenocarcinoma progression and metastasis. Kras;p53 mice survived 2.4 times longer than Kras;p53;E-cadherin mice. The severe decrease in survival of the Kras;p53;E-cadherin mice was most likely due to the large lung tumor burden that developed just 8 weeks after AdCre infection. The Kras;p53;E-cadherin mice quickly developed invasive grade 4 tumors with a desmoplastic stroma. Desmoplasia gives structural support to tumor cells and is associated with tumor-associated fibroblasts and more aggressive/metastatic lesions (17, 18). It is commonly observed in NSCLC tumors, but it is not frequently found in mouse NSCLC models, so the Kras;p53;E-cadherin mouse phenotype more closely recapitulates human disease. All of the Kras;p53;E-cadherin mice had local metastases to the lymph nodes or chest wall, and 38% had distant metastases to the liver or kidney, showing that metastatic rates were also increased when E-cadherin expression was lost in the Kras;p53 tumors.

Although distant metastases kill the majority of patients with lung cancer, the Kras;p53;E-cadherin mice most likely die of their lung tumor burden. Because the Kras;p53;E-cadherin mouse tumors progress so quickly, it may be useful to lower the AdCre infection titer in the future so that fewer cells are infected and fewer tumors are initiated in the lungs. This may lower the lung tumor burden and allow the mice to survive longer so that more tumor cells are able to metastasize to distant sites.

When E-cadherin was conditionally deleted using doxycycline in a lung adenocarcinoma model driven by C-Raf in alveolar type II cells, large invasive tumors grew, which were positive for the endothelial marker CD31 (19). After a long latency of over 9 months, 25% of the mice developed lymph node micrometastases. Whereas we also saw an increase in metastasis rates when E-cadherin was conditionally deleted from Kras;p53 tumors, we did not observe an increase in tumor vascularization. We also observed metastases after 2 months. These disparities may be due to differences in oncogenic Kras versus C-Raf tumor initiation. Notably, Kras is mutated much more frequently than C-Raf, also known as Raf-1, in lung adenocarcinomas (20). The Kras;p53;E-cadherin mouse model may therefore be more reflective of patient disease than other existing mouse models.

The cell lines developed from the Kras;p53;E-cadherin tumors were more migratory than those from the Kras;p53 tumors. Loss of E-cadherin is therefore important in the migration step of the metastatic cascade, but it could affect other steps as well. These cell lines will be a valuable resource for future mechanistic studies.

Finally, it is important to note that the role of EMT in metastasis has been debated. Recent lineage-tracing experiments using various EMT promoters driving Cre expression have shown conflicting results, with some supporting a role of EMT in metastasis and others showing that EMT is dispensable for the process (21–23). This is most likely because the plasticity of epithelial and mesenchymal marker expression is difficult to recapitulate using a single promoter (24). Another controversy is that metastases usually have an epithelial and not mesenchymal morphology (24). Several mouse model studies with inducible EMT transcription factor expression have shown that cancer cells may use EMT to disseminate to other sites but then return to an epithelial state through a mesenchymal–epithelial transition to grow in these secondary sites (25, 26). The role of E-cadherin may therefore be context specific. Notably, the metastases of the Kras;p53;E-cadherin mice look similar to the grade 4 primary tumors and do not express E-cadherin (Figures E4B and E4C). One possible caveat of the Kras;p53;E-cadherin mouse model may therefore be that the metastases do not undergo mesenchymal–epithelial transition and return to an epithelial state. In addition, it has been shown that tumor cells can induce local stromal cells to become reactive and contribute to tumor cell invasion and metastasis through secretion of protumorigenic factors (27). Epithelial E-cadherin loss may therefore not be crucial for metastasis in all tumor types. The Kras;p53;E-cadherin mice will be most useful for gaining an understanding of the metastatic process in which epithelial cells have undergone E-cadherin loss.

Taken together, our studies support previous findings that E-cadherin is an important regulator of lung adenocarcinoma progression and metastasis. Kras;p53;E-cadherin mice rapidly develop advanced lung adenocarcinomas with a desmoplastic stromal microenvironment and many metastases just 8 weeks after tumor initiation. This mouse model may therefore be used to study the molecular mechanisms driving desmoplasia and metastasis in lung tumor biology and to test new therapies that target these processes.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors thank members of the Kim laboratory for critical reading of the manuscript and helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Supported by American Cancer Society Postdoctoral Fellowship PF-09-121-01-DDC, a Harvard Stem Cell Institute National Institutes of Health (NIH) training grant, the Free to Breathe (formerly the National Lung Cancer Partnership) 2012 Young Investigator Research Grant (K.W.S.). Support was also provided by the V Foundation for Cancer Research; American Cancer Society Research Scholar grant RSG-08-082-01-MGO; the Freeman Trust; the Harvard Stem Cell Institute; NIH/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants R01 HL090136, R01 HL132266, R01 HL125821, U01 HL100402, and RFA-HL-09-004; the Thoracic Foundation; the Ellison Foundation; Joan’s Legacy; and the Boston Children’s Hospital Faculty Career Development Fellowship (C.F.K.).

Author Contributions: K.W.S., K.J.B., J.B., and P.P.: designed and performed experiments and analyzed data; M.G. and C.F.B.: analyzed data; R.T.B.: analyzed histology; C.F.K.: designed experiments, analyzed data, and provided funding; and K.W.S. and C.F.K.: wrote the manuscript.

This article has a data supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2017-0210OC on February 15, 2018

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jackson EL, Willis N, Mercer K, Bronson RT, Crowley D, Montoya R, et al. Analysis of lung tumor initiation and progression using conditional expression of oncogenic K-ras. Genes Dev. 2001;15:3243–3248. doi: 10.1101/gad.943001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jackson EL, Olive KP, Tuveson DA, Bronson R, Crowley D, Brown M, et al. The differential effects of mutant p53 alleles on advanced murine lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65:10280–10288. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Onder TT, Gupta PB, Mani SA, Yang J, Lander ES, Weinberg RA. Loss of E-cadherin promotes metastasis via multiple downstream transcriptional pathways. Cancer Res. 2008;68:3645–3654. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu D, Huang C, Kameyama K, Hayashi E, Yamauchi A, Kobayashi S, et al. E-cadherin expression associated with differentiation and prognosis in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;71:949–954, discussion 954–955. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(00)02545-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu Y, Liu HB, Ding M, Liu JN, Zhan P, Fu XS, et al. The impact of E-cadherin expression on non-small cell lung cancer survival: a meta-analysis. Mol Biol Rep. 2012;39:9621–9628. doi: 10.1007/s11033-012-1827-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoo JY, Yang SH, Lee JE, Cho DG, Kim HK, Kim SH, et al. E-cadherin as a predictive marker of brain metastasis in non-small-cell lung cancer, and its regulation by pioglitazone in a preclinical model. J Neurooncol. 2012;109:219–227. doi: 10.1007/s11060-012-0890-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang YL, Chen MW, Xian L. Prognostic and clinicopathological significance of downregulated E-cadherin expression in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e99763. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim H, Yoo SB, Sun P, Jin Y, Jheon S, Lee CT, et al. Alteration of the E-cadherin/β-catenin complex is an independent poor prognostic factor in lung adenocarcinoma. Korean J Pathol. 2013;47:44–51. doi: 10.4132/KoreanJPathol.2013.47.1.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wen L, Sun L, Xi Y, Chen X, Xing Y, Sun W, et al. Expression of calcium sensing receptor and E-cadherin correlated with survival of lung adenocarcinoma. Thorac Cancer. 2015;6:754–760. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.12255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sowa T, Menju T, Sonobe M, Nakanishi T, Shikuma K, Imamura N, et al. Association between epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cancer stemness and their effect on the prognosis of lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Med. 2015;4:1853–1862. doi: 10.1002/cam4.556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Imielinski M, Berger AH, Hammerman PS, Hernandez B, Pugh TJ, Hodis E, et al. Mapping the hallmarks of lung adenocarcinoma with massively parallel sequencing. Cell. 2012;150:1107–1120. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boussadia O, Kutsch S, Hierholzer A, Delmas V, Kemler R. E-cadherin is a survival factor for the lactating mouse mammary gland. Mech Dev. 2002;115:53–62. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00090-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DuPage M, Dooley AL, Jacks T. Conditional mouse lung cancer models using adenoviral or lentiviral delivery of Cre recombinase. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:1064–1072. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bremnes RM, Dønnem T, Al-Saad S, Al-Shibli K, Andersen S, Sirera R, et al. The role of tumor stroma in cancer progression and prognosis: emphasis on carcinoma-associated fibroblasts and non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:209–217. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181f8a1bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Winslow MM, Dayton TL, Verhaak RG, Kim-Kiselak C, Snyder EL, Feldser DM, et al. Suppression of lung adenocarcinoma progression by Nkx2-1. Nature. 2011;473:101–104. doi: 10.1038/nature09881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen Z, Fillmore CM, Hammerman PS, Kim CF, Wong KK. Non-small-cell lung cancers: a heterogeneous set of diseases. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:535–546. doi: 10.1038/nrc3775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karagiannis GS, Poutahidis T, Erdman SE, Kirsch R, Riddell RH, Diamandis EP. Cancer-associated fibroblasts drive the progression of metastasis through both paracrine and mechanical pressure on cancer tissue. Mol Cancer Res. 2012;10:1403–1418. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-12-0307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ceteci F, Ceteci S, Karreman C, Kramer BW, Asan E, Götz R, et al. Disruption of tumor cell adhesion promotes angiogenic switch and progression to micrometastasis in RAF-driven murine lung cancer. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:145–159. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Campbell JD, Alexandrov A, Kim J, Wala J, Berger AH, Pedamallu CS, et al. Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Distinct patterns of somatic genome alterations in lung adenocarcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas. Nat Genet. 2016;48:607–616. doi: 10.1038/ng.3564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trimboli AJ, Fukino K, de Bruin A, Wei G, Shen L, Tanner SM, et al. Direct evidence for epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:937–945. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fischer KR, Durrans A, Lee S, Sheng J, Li F, Wong ST, et al. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition is not required for lung metastasis but contributes to chemoresistance. Nature. 2015;527:472–476. doi: 10.1038/nature15748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beerling E, Seinstra D, de Wit E, Kester L, van der Velden D, Maynard C, et al. Plasticity between epithelial and mesenchymal states unlinks EMT from metastasis-enhancing stem cell capacity. Cell Reports. 2016;14:2281–2288. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yeung KT, Yang J. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in tumor metastasis. Mol Oncol. 2017;11:28–39. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.12017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsai JH, Donaher JL, Murphy DA, Chau S, Yang J. Spatiotemporal regulation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition is essential for squamous cell carcinoma metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:725–736. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tran HD, Luitel K, Kim M, Zhang K, Longmore GD, Tran DD. Transient SNAIL1 expression is necessary for metastatic competence in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2014;74:6330–6340. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bussard KM, Mutkus L, Stumpf K, Gomez-Manzano C, Marini FC. Tumor-associated stromal cells as key contributors to the tumor microenvironment. Breast Cancer Res. 2016;18:84. doi: 10.1186/s13058-016-0740-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]