Abstract

Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress is evident in the alveolar epithelium of humans and mice with pulmonary fibrosis, but neither the mechanisms causing ER stress nor the contribution of ER stress to fibrosis is understood. A well-recognized adaptive response to ER stress is that affected cells induce lipid synthesis; however, we recently reported that lipid synthesis was downregulated in the alveolar epithelium in pulmonary fibrosis. In the present study, we sought to determine whether lipid synthesis is needed to resolve ER stress and limit fibrotic remodeling in the lung. Pharmacologic and genetic manipulations were performed to assess whether lipid production is required for resolving ER stress and limiting fibrotic responses in cultured alveolar epithelial cells and whole-lung tissues. Concentrations of ER stress markers and lipid synthesis enzymes were also measured in control and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis lung tissues. We found that chemical agents that induce ER stress (tunicamycin or thapsigargin) enhanced lipid production in cultured alveolar epithelial cells and in the mouse lung. Moreover, lipid production was found to be dependent on the enzyme stearoyl–coenzyme A desaturase 1, and when pharmacologically inhibited, ER stress persisted and lung fibrosis ensued. Conversely, lipid production was reduced in mouse and human fibrotic lung, despite there being an increase in the magnitude of ER stress. Furthermore, augmenting lipid production effectively reduced ER stress and mitigated fibrotic remodeling in the mouse lung after exposure to silica. Augmenting lipid production reduces ER stress and attenuates fibrotic remodeling in the mouse lung, suggesting that similar approaches might be effective for treating human fibrotic lung diseases.

Keywords: lipid synthesis, endoplasmic reticulum stress, unfolded protein response, pulmonary fibrosis, alveolar epithelium

Clinical Relevance

Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress is increased in the alveolar epithelium of rodents and humans with pulmonary fibrosis, but the mechanisms causing ER stress and the contribution of ER stress to fibrotic remodeling are unknown. This study provides a unifying mechanism linking ER stress to the development of pulmonary fibrosis. We show that metabolic dysfunction, namely the impairment of lipid synthesis, reduces the capacity of alveolar epithelial cells to resolve ER stress, leading to sustained cellular dysfunction and induction of fibrotic responses. We also provide evidence that pharmacological or dietary approaches to increasing lung lipids could be effective in treating pulmonary fibrosis.

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) fulfills many important cellular functions, including the regulation of intracellular calcium concentration, the production of lipids, and the synthesis of most membrane and secreted proteins. To ensure that proteins produced in the ER reach their final destination, the ER contains a vast array of enzymes and chaperone proteins to assist in folding and deployment of individual proteins. However, genetic mutations and numerous other cellular disturbances sometimes disrupt the ability of the ER to fold proteins, leading to the accumulation of misfolded or unfolded proteins in the ER lumen, also called ER stress. To minimize this stress, cells activate the unfolded protein response (UPR), which discards of improperly folded proteins in a rapid fashion.

The UPR is an evolutionarily conserved mechanism designed to improve protein folding and prevent organelle dysfunction or cell death caused by misfolded proteins. The UPR alleviates ER stress through a wide range of mechanisms, including by decreasing mRNA transcription and translation, enhancing ER chaperone production, and augmenting degradation of misfolded proteins. In addition, the UPR upregulates lipid synthesis to elongate the ER membrane and assist in the formation of lipid droplets, which help in targeting misfolded proteins to the ER-associated degradation pathway (1–3). Although activation of the UPR is usually effective in restoring ER homeostasis, when stress is severe or prolonged, the UPR becomes maladaptive and triggers apoptotic cell death (1).

Chronic ER stress is now recognized to contribute to a wide range of diseases, including neurodegenerative disorders, obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and pulmonary fibrosis (4–6). Initial evidence linking ER stress to pulmonary fibrosis came from observations in patients with familial interstitial pneumonia, in whom mutations causing misfolding of surfactant protein C were identified (7, 8). However, it has since been learned that ER stress is also prominently increased in alveolar epithelial type II (AE2) cells from patients with many other fibrotic lung disorders, including connective tissue–associated interstitial lung diseases, asbestosis, and various other conditions (7, 9). Together, these observations support the concept that AE2 cells are unable to manage their ER proteome in pulmonary fibrosis and that chronic ER stress may contribute to the development of disease.

Despite the connection between ER stress and pulmonary fibrosis, many questions remain regarding the relationship between these pathological conditions. First, the triggers for ER stress in patients not carrying mutations in surfactant proteins remain unknown. Second, it has not been determined whether ER stress actually plays a causal role in disease, because individuals who express mutant forms of surfactant proteins do not develop disease until adulthood, suggesting that a second “hit” may be needed (8). Consistent with this notion, mice genetically engineered to express mutant surfactant proteins or treated with an ER stress–inducing agent do not develop pulmonary fibrosis in the absence of some other additional insult(s), such as bleomycin (10). Thus, in some contexts, ER stress may be necessary but not sufficient to induce pulmonary fibrosis.

One explanation for why ER stress may not uniformly lead to the pulmonary fibrosis could be quantitative, meaning that the UPR triggers fibrotic remodeling only when excessive ER stress renders cell recovery impossible. In other words, fibrotic responses are induced only when UPR-mediated response is ineffective, as would occur if one or more components of the UPR were inoperable. With this in mind, we recently observed that diverse types of profibrotic pulmonary insults lead to a sustained downregulation of lipid synthesis in the alveolar epithelium (AE) of the mouse lung, suggesting that metabolic defects might contribute to an insufficient UPR (11). In this study, we tested the hypothesis that downregulation of lipid synthesis compromises the ability of the UPR to resolve ER stress, and we assessed whether augmenting lipid production can reduce ER stress and protect against pulmonary fibrosis in the mouse lung.

Methods

Mouse Studies

C57BL/6 mice (6–8 wk old) were employed in these studies. ER stress was induced by instilling tunicamycin (TM; 2 μg) into the lung twice weekly for 2 weeks (10). Lung fibrosis was caused by administering silica (10 mg; diameter, 1–5 μm) (11). To inhibit stearoyl–coenzyme A desaturase 1 (SCD1) activity, mice received MF-438 at 30 mg/kg once daily for 14 days. To augment lipid synthesis, mice received daily intraperitoneal injections of the liver X receptor α (LXRα) agonist T0901317 for 10 days beginning on Day 4 after silica (13, 14). All animal protocols were reviewed and approved by the institutional animal care and use committees at Thomas Jefferson University and complied with the National Research Council’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Human Subjects

The diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) was established on the basis of American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society criteria. Non-IPF lung tissues were acquired through the New England Donor Services Age, sex, and smoking history of individuals from whom samples were acquired are listed in Table E1 in the data supplement. All patient information was maintained in locked databases. The study was approved by the institutional review boards at Thomas Jefferson University and Harvard University.

Lipid Extraction and Analysis

Total lipids were extracted from lung tissues by employing a modified method of Bligh and Dryer in chloroform/methanol (2:1) (12). The lipid extracts were assayed for triglyceride (TAG), total cholesterol, and phospholipid (PL) content using commercially available kits.

Lung Histology and Immunohistochemistry

See the Methods section of the data supplement for details of lung histology and immunohistochemistry.

RNA Isolation and Analysis

Gene transcript amounts were quantified by RT-PCR. See the data supplement for details on the specific primers used.

Protein Analysis

Immunoblots were performed using published protocols with antibodies directed against activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), inositol-requiring enzyme 1 (IRE-1α), phosphorylated IRE-1α (p-IRE-1α), eukaryotic elongation factor 2 (elf2), phosphorylated elf2 (pelf2), CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein homologous protein (CHOP), caspase 3 (CASP3), fatty acid synthase (FAS), LXRα, latent transforming growth factor-β–binding protein 1 (LTBP1), latent transforming growth factor-β–binding protein 4 (LTBP4), sterol regulatory element–binding transcription factor 1 (SREBP1), diacylglycerol O-acyltransferase 1 (DGAT1), protein kinase R–like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK), and phosphorylated PERK (pPERK). See the data supplement for more details. Transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 was measured by ELISA.

In Vitro Assays

MLE12 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection and cultured as previously described. Cells were plated with or without one or more of the following: silica (9.25–150 μg/cm2), TM (0.25–1 μg/ml), thapsigargin (Tg; 1 μM), and SCD1 (1 μM).

Plasmid Transfections

Transient transfections were performed in MLE12 cells using the pSV-Sport-SREBP-1c or pSV-SPORT plasmid.

Boron Dipyrromethene Staining of Lipid Droplets

Cells were seeded into 6-well plates and fixed with 10% formalin before staining with boron dipyrromethene (BODIPY) 493/503 (1:1,000 dilution).

Lipidomic Analysis with Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry

Lipidomic analysis was performed by liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry as previously described (15). See the data supplement for details.

Statistical Analysis

Two-group comparisons were analyzed by unpaired Student’s t test, whereas multiple-group comparisons were performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc analysis. Statistical significance was achieved when the P value was less than 0.05 at the 95% confidence interval.

Findings

ER stress promotes lipid synthesis in lung epithelium

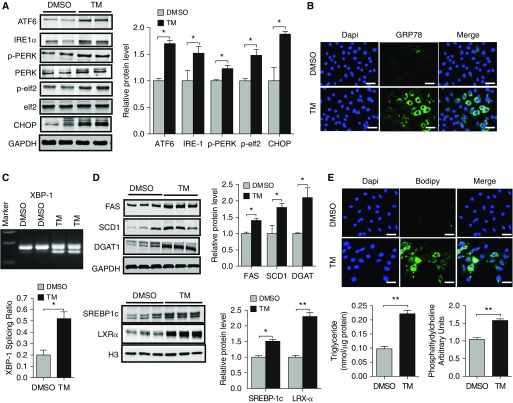

To assess whether ER stress induces lipid synthesis in AE, we cultured MLE12 cells with varying concentrations of TM, an antibiotic that promotes ER stress by blocking N-linked protein glycosylation. As expected, TM readily induced ER stress, as indicated by increased expression of the three major sensors of misfolded proteins (ATF6, IRE1α, and PERK) (Figures 1A and E1), as well as by increased expression of various downstream UPR effector molecules, including CHOP, the translation initiation factor ELF2, GRP78 (78 kD glucose-regulated protein), and the spliced form of XBP1 (X-box binding protein 1) (Figures 1A–1C). In addition, we found that induction of ER stress was associated with a dose-dependent increase in the expression of various components of the lipid synthetic machinery, including the rate-limiting enzymes FAS and SCD1, the TAG-synthesizing enzyme DGAT1, and the transcription factors SREBP1c and LXRα (Figures 1D and Figure E1). Time-course analysis indicated that the induction of ER stress was followed by upregulation in lipid synthesis enzymes (Figure E2), suggesting that lipid synthesis is needed for resolving ER stress. Consistent with an increase in the machinery for synthesizing lipids, we also found that TAG concentrations and neutral lipid concentrations (BODIPY stain) were dramatically increased after TM treatment (Figure 1E). Modest increases were also observed in PL concentrations (Figure 1E), whereas cholesterol concentrations were minimally affected by even high-dose TM (1 μg/ml) treatment (data not shown). Next, to assess whether induction of lipid synthesis was specific to TM, we exposed MLE12 cells to Tg, a plant extract that causes ER stress by blocking calcium entry into the ER lumen (16). Similarly to TM, Tg increased the expression of numerous UPR proteins (Figures E3A and E3B) and induced lipid synthesis as judged by increased concentrations of FAS, SCD1, DGAT1, LXRα, and SREBP1c (Figure E3C) as well as marked accumulation of intracellular neutral lipids (Figure E3D). Taken together, these findings indicate that chemically induced ER stress promotes lipid accumulation in the AE.

Figure 1.

Tunicamycin (TM) induces lipid synthesis in mouse lung epithelial 12 (MLE12) cells. (A) Western blots for activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), inositol-requiring enzyme 1 (IRE-1α), phosphorylated protein kinase R–like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (pPERK), PERK, phosphorylated eukaryotic elongation factor 2 (pelf2), elf2, and CCAAT/enhancer binding protein homologous protein (CHOP) in MLE12 cells cultured in media containing either vehicle (DMSO) or TM (1 μg/ml) for 24 hours (with GAPDH loading control). (B) 78 kD glucose-regulated protein (anti-Grp78) antibody (green) staining in control and TM-exposed MLE12 cells (blue represents DAPI nuclear stain). (C) Spliced X-box binding protein 1 (Xbp1) concentrations in control and TM-treated cells. (D) Western blots for fatty acid synthase (FAS), stearoyl–coenzyme A desaturase (SCD1), diacylglycerol O-acyltransferase 1 (DGAT1), sterol regulatory element–binding protein 1 (SREBP1c), and liver X receptor (LXR)-α in DMSO- or TM-exposed cells. (E) Boron dipyrromethene (BODIPY) neutral lipid staining of DMSO- and TM-treated cells. (F) Triacylglyceride and phospholipid concentrations in whole-cell lysates of DMSO- and TM-treated MLE12 cells. Immunoblots are representative of at least two different blots, and densitometric analyses (bar graphs) are representative of six or more mouse specimens (*P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 vs. DMSO, respectively). Scale bars: 20 μm. Data are expressed as mean ± SE, and statistical significance was assessed using an unpaired Student’s t test. H3 = histone 3.

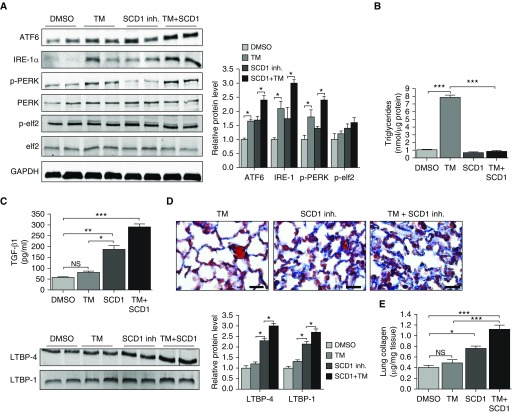

Blocking SCD1 induces ER stress and enhances fibrotic responses

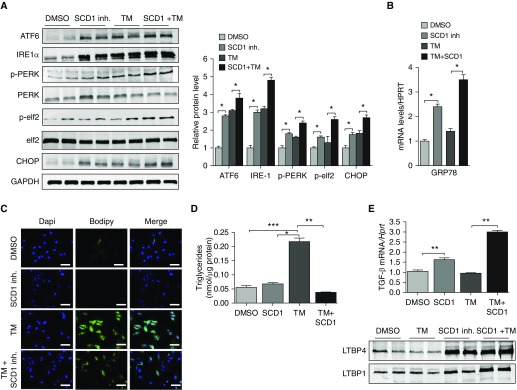

Prior studies in the obesity field have demonstrated that saturated fatty acids (FAs) induce ER stress, whereas monounsaturated FAs have ER stress–reducing capabilities (5, 17). With this in mind, we hypothesized that production of unsaturated FAs might be important for resolving ER stress in the AE. To test this, we exposed MLE12 cells to a pharmacological inhibitor of SCD1, followed by 24-hour treatment with TM. SCD1 was chosen because 1) we observed that SCD1 concentrations were markedly upregulated in mouse lung epithelium after TM treatment, and 2) others have shown that SCD1 activity is required to resolve ER stress to saturated FAs and is essential for inducing SREBP1c activation. As shown in Figures 2A and 2B, inhibition of SCD1 was, by itself, sufficient to induce ER stress in MLE12 cells, as evidenced by an upregulation in expression of numerous UPR proteins. However, whereas induction of ER stress was similar in magnitude to that observed with TM, inhibition of SCD1 did not engender accumulation of intracellular lipids (Figures 2C and 2D). Similarly, when an SCD1 inhibitor was administered with TM, intracellular lipids did not accumulate, even though markers of ER stress were elevated beyond what was observed with TM alone (Figures 2C and 2D). These findings indicate that SCD1 activity is required for enhancing lipid production in response to TM.

Figure 2.

Inhibition of SCD1 activity induces endoplasmic reticulum stress and promotes the production of profibrotic mediators. (A) Western blots for ATF6, IRE-1α, pPERK, PERK, and CHOP in MLE12 cells cultured in media alone or in media containing SCD1 inhibitor (1 μM), tunicamycin (TM; 1 μg/ml), or SCD1 inhibitor plus TM (with GAPDH loading control). (B) mRNA amounts for GRP78 in MLE12 cells treated with SCD1 inhibitor, TM, or SCD1 inhibitor plus TM. (C) Neutral lipid staining in MLE12 cells under various conditions. Scale bars: 20 μm. (D) Triacylglyceride concentrations in whole-cell lysates. (E) Transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 concentrations and expression of latent TGF-β–binding proteins (LTBP) 1 and LTBP4 in MLE12 cells. Images are representative of two different blots (n = 6 per group), and results of densitometric analysis are depicted in bar graphs. Statistical significance was assessed by analysis of variance: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 versus control group. HPRT = hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase; inh = inhibitor.

Because we previously showed that lipid synthesis is downregulated in the AE in response to several different profibrotic pulmonary insults, we hypothesized that inhibition of lipid synthesis might represent a “second hit” that triggers fibrosis in response to ER stress. To test this hypothesis, we examined whether profibrotic mediators are regulated in response to TM, an SCD1 inhibitor, or to the two treatments combined. As previously reported, TM did not enhance expression of TGF-β1 or LTBP1 and LTBP4 (Figure 2E) in cultured AE cells (12, 18). However, expression of these mediators was significantly increased when cells were exposed to either an SCD1 inhibitor alone or to an SCD1 inhibitor plus TM, indicating that loss of SCD1 activity is sufficient to trigger fibrotic responses in the AE.

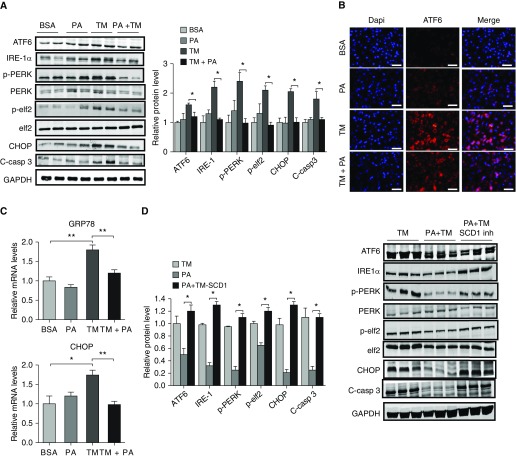

We next reasoned that if SCD1 activity is required for resolving ER stress, then supplying this enzyme with an additional substrate might facilitate the reduction of ER stress. To test this, we exposed MLE12 cells to different concentrations of the saturated FA palmitate and measured expression of ER stress markers. We first used low (physiologic) concentrations (100 μM) of palmitate, reasoning that higher concentrations might exceed maximal desaturase activity of this rate-limiting enzyme and promote ER stress in our model. As shown in Figure 3, we found that low concentrations of palmitate reduced ER stress in response to TM (Figures 3A–3C), and these effects were entirely abolished when SCD1 inhibitor was added to the culture media (Figure 3D). In contrast, high concentrations of palmitate (200 μM) were found to be toxic to cells, causing enhanced expression of ER stress markers (data not shown). Collectively, these findings support our hypothesis that production of unsaturated FAs is important for resolving ER stress.

Figure 3.

Treatment with palmitate attenuates endoplasmic reticulum stress in response to tunicamycin. (A) Expression of endoplasmic reticulum stress markers ATF6, IRE-1α, pPERK, PERK, pelf2, elf2, CHOP, and cleaved caspase 3 (C-casp 3) in MLE12 cells cultured with BSA or BSA plus palmitate (PA; 100 μM) in the presence or absence of TM (with GAPDH loading control). (B) ATF6 expression in MLE12 cells grown in chamber slides and treated with BSA, PA, TM, or TM + PA for 24 hours. Scale bars: 20 μm. (C) Treatment with palmitate reduced transcript amounts of GRP78 and CHOP in response to TM. (D) Treatment with palmitate reduced expression of ATF6, IRE-1α, pPERK, PERK, pelf2, elf2, CHOP, and cleaved caspase 3 in MLE12 cells, and these effects were abolished by adding SCD1 inhibitor to the culture media. Images are representative of two different blots, and results of densitometric analysis are depicted in bar graphs (n = 6, per group). Statistical significance was assessed by ANOVA: *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 versus control group.

TM promotes lipid synthesis in the lung

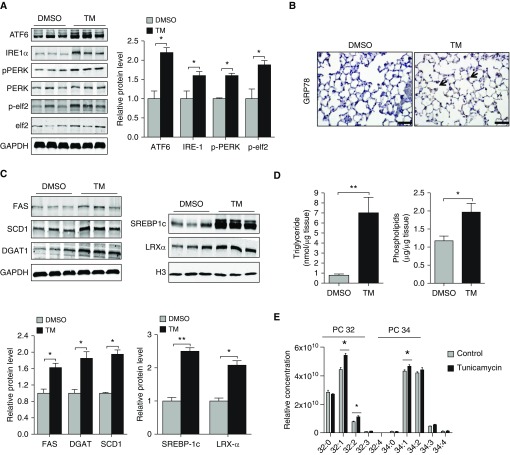

To test whether ER stress promotes a similar increase in lipid synthesis in the lung, we instilled TM into the airway of mice and assessed for effects on lipid production. Consistent with findings in vitro, TM-induced ER stress (Figures 4A and 4B) was associated with enhanced expression of FAS, SCD1, DGAT1, SREBP1c, and LXRα in the mouse lung (Figure 4C) and increased TAG and PL concentrations (Figure 4D). Next, we performed liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry analysis to quantify lipid species in control and TM-exposed lung tissues. Consistent with our hypothesis that production of unsaturated FAs is needed to resolve ER stress, we found that concentrations of monounsaturated fatty acyl chains on PLs were elevated in TM-treated mice (Figure 4E). In contrast, FA composition on acylcarnitines (16, 16:1, 18:0, 18:1, 18:2) was largely unaffected, indicating that TM treatment modulates endogenous FA production but has little to no effect on the composition of FA entering the lung from the pulmonary circulation.

Figure 4.

TM augments lipid production in the lung. (A) Western blots for ATF6, IRE-1α, pPERK, PERK, pelf2, and elf2 in control and TM-exposed (2 μg/mouse in 75 μl twice weekly) lung tissues (with GAPDH loading control). (B) Representative lung tissue sections from mice receiving TM treatment or DMSO show an increase in GRP78 staining in alveolar epithelial type II cells. Scale bars: 50 μm. (C) Western blots for FAS, DGAT1, SCD1, SREBP1c, and LXRα in whole-lung tissues after either DMSO or TM (with GAPDH or H3 loading control). (D) Triglyceride and phospholipid concentrations in the lung after twice-weekly instillation of DMSO or TM. (E) Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry analysis of lung tissue after DMSO or TM treatment. Statistical significance was assessed for A–D with Student’s t test: *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 versus control group (n = 6 in each group). For liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry, statistical significance was assessed by ANOVA: *P < 0.05 versus control group (n = 4 per group).

Blocking lipid synthesis causes lung fibrosis

To determine whether desaturase activity is important for resolving ER stress in vivo, we administered SCD1 inhibitor to mice for 14 days. Similar to findings in vitro, we found that inhibition of SCD1 was sufficient to induce ER stress in the lung (Figure 5A). As expected, activation of the UPR did not stimulate TAG accumulation in the lungs of mice treated with SCD1 inhibitor (Figure 5B). Similarly, we found that treatment with SCD1 inhibitor abrogated the lipid accumulation observed with TM treatment alone, indicating the importance of SCD1 activity in augmenting lipid production in the lung. Moreover, we found that inhibition of SCD1 activity markedly enhanced production of profibrotic factors TGF-β1, LTBP1, and LTBP4 (Figure 5C) and provoked tissue remodeling, as reflected by increased trichrome staining in the interstitial spaces of affected lungs (Figure 5D) and by elevated hydroxyproline concentrations in lung digests (Figure 5E). However, it is worth noting that lung fibrosis induced by SCD1 inhibition was subtle compared with classical pulmonary insults such as bleomycin, radiation, or silica dust, and it was devoid of inflammation and evident only based on careful histological examination of the lung. Together, these findings indicate that SCD1 activity is required for resolving ER stress and suppressing fibrotic remodeling in the lung.

Figure 5.

Inhibition of SCD1 induces endoplasmic reticulum stress and promotes fibrotic responses in the lung. (A) Western blots for ATF6, IRE-1α, pPERK, PERK, pelf2, and elf2 in mice treated with vehicle, SCD1 inhibitor (30 mg/kg daily), TM (20 μg/ml in 100 μl twice weekly), or SCD1 inhibitor plus TM (with GAPDH loading control). (B) Treatment with SCD1 inhibitor blocks TM-induced triglyceride accumulation in the lung. (C) TGF-β1, LTBP1, and LTBP4 concentrations in whole-lung tissues from mice treated with vehicle, TM, SCD1 inhibitor, or TM plus SCD1 inhibitor. (D) High-power view of trichrome-stained lung tissues (blue, collagen) and (E) collagen concentrations in lung tissues from mice treated with vehicle control, TM, SCD1 inhibitor, or TM plus SCD1. Scale bars: 40 μm. Statistical significance was assessed by ANOVA: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 versus control group (n = 6 per group). NS = not significant.

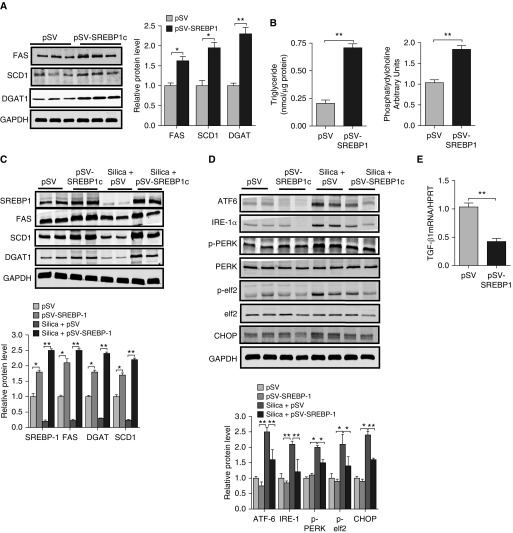

Enhancing lipid synthesis reduces ER stress and attenuates fibrosis in the lung

Because inhibition of lipid synthesis induced fibrotic responses, we reasoned that augmenting lipid production might reduce fibrotic responses to a known pulmonary insult. To test this, we transduced MLE12 cells with a plasmid containing the gene for SREBP1c under a constitutively active promoter to broadly increase lipid production. Consistent with the known activity of SREBP1c, we found that overexpression of SREBP1 resulted in increased expression of FAS, DGAT, and SCD1 (Figure 6A) as well as marked accumulation of TAGs and PLs (Figure 6B). Next, to assess whether augmenting lipid production attenuates fibrotic responses, we exposed control and SREBP1c-overexpressing cells to silica dust for 24 hours and assessed the effects on TGF-β1 production. Whereas high concentrations of silica exposure reduced lipid synthesis (Figure 6C), we found that lipid synthesis was actually upregulated in response to low concentrations of silica dust exposure (Figure E4). Moreover, the suppressive effect that high concentrations of silica had on lipid synthesis was partially reversed in cells engineered to overexpress SREBP1c (Figure 6C). Furthermore, we found that enhancing SREBP1 expression in cells exposed to high concentrations of silica had an attenuating effect on the expression of ER stress markers (Figure 6D) and significantly reduced TGF-β1 production (Figure 6E), supporting the notion that augmenting lipid synthesis can reduce ER stress and limit fibrotic remodeling in the lung.

Figure 6.

Overexpression of SREBP1c attenuates endoplasmic reticulum stress in MLE12 cells after exposure to silica dust. (A) Western blots for FAS, SCD1, and DGAT1 in MLE12 cells transduced with control or SREBP1c-expressing vectors (with GAPDH loading control). (B) Overexpression of SREBP1c increases triglyceride and phospholipid production in MLE12 cells. (C) Western blots for SREBP1c, FAS, SCD1, and DGAT in MLE12 cells transduced with control or SREBP1c-expressing vectors and cultured with or without silica dust. (D) Western blots for ATF6, IRE-1α, pPERK, PERK, pelf2, elf2, and CHOP in control and SREBP1c-expressing cells cultured with or without silica dust. (E) Transcript amounts for Tgfβ1 were significantly reduced in silica-exposed MLE12 cells overexpressing SREBP1c. Images are representative of two different blots, and results of densitometric analysis are depicted in bar graphs. Statistical significance was assessed by ANOVA: *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 versus control group (n = 6 or greater in all groups).

Next, to assess whether augmenting lipid synthesis has antifibrotic effects in vivo, we first confirmed that lipid synthesis is reduced in the lung after silica exposure. As shown in Figure E5, we detected an early and sustained decrease in mRNA and protein concentrations for numerous lipid-synthesizing molecules, including FAS, SCD1, and the transcription factors LXRα and SREBP1 (Figures E5A and E5B) in whole-lung tissues; these findings are similar to those reported in the bleomycin model (12). Moreover, this downregulation in lipid synthetic machinery was associated with a significant reduction in TAG concentrations in lung digests (Figure E5C) and enhanced expression of numerous ER stress markers (Figure E5D). Similarly, we observed an inverse association between the expression of lipid synthetic enzymes and expression of ER stress markers in primary AE2 cells isolated from the lungs of silica-exposed mice (Figure E6), and we observed a similar phenomenon in the lungs of humans affected by IPF (Figures E7A and E7B), suggesting that the findings in mice are applicable to human disease.

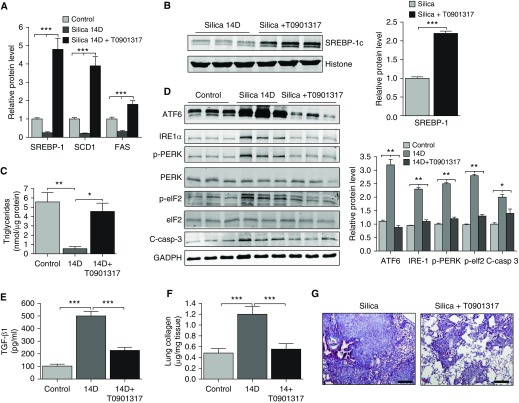

Finally, to test whether augmenting lipid production can attenuate pulmonary fibrosis in vivo, we administered the Lxrα agonist T0901317 to mice for 10 days beginning 4 days after exposure to silica. We selected T0901317 because it is a potent inducer of SREBP1c, whose activity was found to reduce ER stress and limit fibrotic responses to silica in vitro (14, 19). Consistent with our in vitro observations, treatment with T0901317 augmented expression of several lipid-synthesizing enzymes (Figures 7A and 7B) and dramatically increased TAG and PL concentrations in the lung (Figure 7C and not shown). Furthermore, we observed that treatment with T0901317 overcame the suppression of lipid synthesis engendered in response to exposure to silica (Figure 7C), markedly reduced expression of ER stress markers (Figure 7D), and significantly attenuated fibrotic remodeling in silica-exposed lungs, as assessed by biochemical (TGF-β1, hydroxyproline) and histological (trichrome staining) measures (Figures 7E–7G). Altogether, these data support the concept that augmenting lipid synthesis can resolve ER stress and prevent fibrotic remodeling in the lung.

Figure 7.

Treatment of mice with LXR agonists enhances lipid synthesis, decreases endoplasmic reticulum stress, and attenuates lung fibrosis in response to silica. (A) Transcript amounts for Srebp1, Scd1, and Fas in lungs of mice exposed to vehicle, silica, or silica plus T0901317 (30 mg/kg). (B) Western blots for SREBP1c at 14 days after silica administration in mice treated with or without T0901317 (with H3 loading control). (C) Triglyceride concentrations in lungs of mice treated with vehicle, silica, or silica plus T0901317. (D) Western blots for ATF6, IRE-1α, pPERK, PERK, pelf2, elf2, and cleaved caspase 3 protein in lungs of mice treated with vehicle, silica, or silica plus T0901317 (with Gapdh loading control). (E and F) Treatment with T0901317 reduced TGF-β1 and hydroxyproline concentrations in lungs of silica-exposed mice. (G) Low-power view of hematoxylin and eosin–stained lungs of silica-exposed mice treated with or without T0901317. Scale bars: 100 μm. Statistical significance was assessed by ANOVA: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 versus control group.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that de novo lipid synthesis is an essential compensatory response to ER stress that, when inhibited, promotes pulmonary fibrosis. Specifically, we observed that the response to ER stress in AE is to upregulate the synthesis of unsaturated FAs. Enhanced production of unsaturated FAs was both necessary and required to maintain ER homeostasis; inhibiting the desaturase enzyme SCD1 resulted in a maladaptive UPR that failed to resolve ER stress and triggered fibrosis in the lung. Importantly, we showed that augmenting lipid production attenuates ER stress and reduces silica-induced pulmonary fibrosis, suggesting that upregulating lipid production might be an effective therapy for fibrotic lung diseases.

Our work supports a unifying hypothesis linking reductions in lipid synthesis to the development of ER stress and pulmonary fibrosis. The importance of lipid synthesis to ER homeostasis is firmly established; it is recognized that ER size and shape change considerably, depending on a cell’s protein synthetic requirements (20). Differentiation of B cells to plasma cells, for example, is accompanied by substantial increases in ER size to meet the synthetic demands of antibody production. Although lipids are required to expand the ER membrane and increase the functional surface area of the ER, there is also emerging evidence that lipid production is needed for exporting misfolded proteins out of the ER lumen in lipid droplets (21, 22) and that lipid synthesis serves to alter ER membrane composition to activate the early steps in the ER-associated degradation pathway (3). Regardless of the mechanism, our findings suggest that augmenting lipid synthesis might be an effective treatment for pulmonary fibrosis.

Our data indicate that production of unsaturated FAs is essential for maintaining ER homeostasis in lung epithelium. These findings are consistent with observations in the obesity field, in which diets rich in monounsaturated FAs reduce ER stress in multiple tissues (4, 5). Our studies indicate that SCD1 plays a critical role in the production of lipids in response to TM; these findings are consistent with previous work showing that SCD1 is important for Srebp1c activation. Furthermore, our findings suggest that augmenting SCD1 activity might be effective for treating fibrotic lung diseases. One question raised by our work is whether dietary lipid manipulations might reduce ER stress in the lung epithelium. Support for such an approach is based on our finding that palmitate reduces TM-induced ER stress in cultured AE cells. However, because patients with IPF appear to have reduced SCD1 concentrations (Figure E7) in their lungs, diets containing even low concentrations of saturated FAs might have deleterious effects.

Although the UPR is considered an adaptive response to cellular stress, prolonged or severe ER stress is maladaptive and triggers activation of apoptotic cell death (1, 2). We show that ER stress induced by silica results in a dysfunctional UPR that fails to induce lipid synthesis (in contrast to TM or Tg). We postulate that injured lung AE cells are unable to upregulate lipid synthesis because of the enormous metabolic demands associated with lipid production and the cell’s need to use energy for other reparative functions. In addition, lipid synthesis appears to be compromised in the IPF lung, because several key lipid synthesis enzymes, including SCD1, were downregulated in patients with this disease. However, we recognize that expression of DGAT was not downregulated in the IPF lung, illustrating the fact that mouse model systems rarely, if ever, fully recapitulate findings in human disease. Although the mechanisms leading to downregulation of some lipid synthesis enzymes in IPF are unknown, we speculate that this might relate to emerging evidence which shows that mitochondrial function and the production of ATP are compromised in the AE in this disease (23).

Importantly, our study also demonstrated that a failed UPR is tied to the production of profibrotic mediators, which presumably serves to stabilize lung barrier function before these chronically “stressed” cells are driven down apoptotic cell death pathways. Because our studies were centered on the AE, we have yet to determine whether profibrotic responses are linked to ER stress in other cells or are specific to cells that perform barrier functions.

Finally, we observed that treating mice with an LXRα agonist, T0901317, reduced ER stress and decreased silica-induced pulmonary fibrosis. We reasoned that because LXRα enhances expression of multiple lipogenic enzymes, this treatment might more effectively drive global lipid production than strategies focused on any single lipogenic enzyme. Although LXRα has known antiinflammatory properties that may have contributed to its ability to mitigate fibrosis, our data indicate that an important feature of the response to T0901317 was enhanced lipid synthesis (13, 14). Notably, we attempted to reduce the effects of T0901317 on the immune system by initiating treatment several days after the initiation of injury. That said, in future studies, researchers need to clarify the precise mechanisms by which T0901317 mediates its effects and to test the ability of other Lxrα agonists, or other compounds that induce lipid synthesis, to inhibit fibrosis in the lung.

In summary, we have shown that lipid synthesis is essential for maintaining ER homeostasis in the lung. In the context of profibrotic insults, failure to adequately induce lipid synthesis in AE cells exacerbates ER stress, enhances the UPR, and induces pulmonary fibrosis. Enhancing lipid synthesis, particularly of unsaturated FAs, protects against ER stress and pulmonary fibrosis in response to insult. Our data suggest that increasing the concentration of unsaturated FAs in the AE might be effective for reducing fibrotic remodeling in the human lung.

Footnotes

Supported by National Heart, Lung, Blood Institute grants R01HL105490 and R01HL131784 (R.S.) and National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) grants P30-ES013508 and K22-ES026235 (N.W.S.). The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIEHS or the National Institutes of Health. The authors thank Erin Hayer and the students and faculty of Spring Cove and Martinsburg elementary schools for their generous donation to support research in Dr. Summer’s laboratory.

Author Contributions: Substantive analysis: F.R., D. Shah, D. Schriner, N.W.S., and R.S.; writing: F.R., C.B.K., J.B.H., N.W.S., and R.S.; planning: F.R., X.H., D. Shah, I.R., Z.G., J.B.H., C.M., A.M.C., N.W.S., and R.S.; funding: N.W.S. and R.S.; and data acquisition: F.R., X.H., D. Shah, Z.G., D. Schriner, J.B., H.S., J.B.H., C.M., N.W.S., and R.S. All authors participated in the intellectual revision of the manuscript and approved the final version.

This article has a data supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2017-0340OC on February 21, 2018

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Puthalakath H, O’Reilly LA, Gunn P, Lee L, Kelly PN, Huntington ND, et al. ER stress triggers apoptosis by activating BH3-only protein Bim. Cell. 2007;129:1337–1349. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walter P, Ron D. The unfolded protein response: from stress pathway to homeostatic regulation. Science. 2011;334:1081–1086. doi: 10.1126/science.1209038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.To M, Peterson CW, Roberts MA, Counihan JL, Wu TT, Forster MS, et al. Lipid disequilibrium disrupts ER proteostasis by impairing ERAD substrate glycan trimming and dislocation. Mol Biol Cell. 2017;28:270–284. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E16-07-0483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ozcan U, Cao Q, Yilmaz E, Lee AH, Iwakoshi NN, Ozdelen E, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress links obesity, insulin action, and type 2 diabetes. Science. 2004;306:457–461. doi: 10.1126/science.1103160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ozcan U, Yilmaz E, Ozcan L, Furuhashi M, Vaillancourt E, Smith RO, et al. Chemical chaperones reduce ER stress and restore glucose homeostasis in a mouse model of type 2 diabetes. Science. 2006;313:1137–1140. doi: 10.1126/science.1128294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shah D, Romero F, Guo Z, Sun J, Li J, Kallen CB, et al. Obesity-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress causes lung endothelial dysfunction and promotes acute lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2017;57:204–215. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2016-0310OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 7.Korfei M, Ruppert C, Mahavadi P, Henneke I, Markart P, Koch M, et al. Epithelial endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis in sporadic idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:838–846. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200802-313OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lawson WE, Crossno PF, Polosukhin VV, Roldan J, Cheng DS, Lane KB, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in alveolar epithelial cells is prominent in IPF: association with altered surfactant protein processing and herpesvirus infection. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;294:L1119–L1126. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00382.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kamp DW, Liu G, Cheresh P, Kim SJ, Mueller A, Lam AP, et al. Asbestos-induced alveolar epithelial cell apoptosis. The role of endoplasmic reticulum stress response. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2013;49:892–901. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2013-0053OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lawson WE, Cheng DS, Degryse AL, Tanjore H, Polosukhin VV, Xu XC, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress enhances fibrotic remodeling in the lungs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:10562–10567. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107559108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Romero F, Shah D, Duong M, Penn RB, Fessler MB, Madenspacher J, et al. A pneumocyte–macrophage paracrine lipid axis drives the lung toward fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2015;53:74–86. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2014-0343OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bligh EG, Dyer WJ. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can J Biochem Physiol. 1959;37:911–917. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitro N, Mak PA, Vargas L, Godio C, Hampton E, Molteni V, et al. The nuclear receptor LXR is a glucose sensor. Nature. 2007;445:219–223. doi: 10.1038/nature05449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Terasaka N, Hiroshima A, Koieyama T, Ubukata N, Morikawa Y, Nakai D, et al. T-0901317, a synthetic liver X receptor ligand, inhibits development of atherosclerosis in LDL receptor-deficient mice. FEBS Lett. 2003;536:6–11. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03578-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Snyder NW, Khezam M, Mesaros CA, Worth A, Blair IA. Untargeted metabolomics from biological sources using ultraperformance liquid chromatography-high resolution mass spectrometry (UPLC-HRMS) J Vis Exp. 2013;(75):e50433. doi: 10.3791/50433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Treiman M, Caspersen C, Christensen SB. A tool coming of age: thapsigargin as an inhibitor of sarco-endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPases. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1998;19:131–135. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(98)01184-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Estruch R, Ros E, Martínez-González MA. Mediterranean diet for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:676–677. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1306659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maitra M, Wang Y, Gerard RD, Mendelson CR, Garcia CK. Surfactant protein A2 mutations associated with pulmonary fibrosis lead to protein instability and endoplasmic reticulum stress. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:22103–22113. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.121467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zelcer N, Tontonoz P. Liver X receptors as integrators of metabolic and inflammatory signaling. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:607–614. doi: 10.1172/JCI27883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schuck S, Prinz WA, Thorn KS, Voss C, Walter P. Membrane expansion alleviates endoplasmic reticulum stress independently of the unfolded protein response. J Cell Biol. 2009;187:525–536. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200907074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Velázquez AP, Tatsuta T, Ghillebert R, Drescher I, Graef M. Lipid droplet-mediated ER homeostasis regulates autophagy and cell survival during starvation. J Cell Biol. 2016;212:621–631. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201508102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fei W, Wang H, Fu X, Bielby C, Yang H. Conditions of endoplasmic reticulum stress stimulate lipid droplet formation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem J. 2009;424:61–67. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bueno M, Lai YC, Romero Y, Brands J, St Croix CM, Kamga C, et al. PINK1 deficiency impairs mitochondrial homeostasis and promotes lung fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:521–538. doi: 10.1172/JCI74942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]