Abstract

Objective: To investigate the relationship between the hypermethylation of folic acid metabolism-related genes and the incidence and prognosis of esophageal cancer among ethnic Kazakhs in Xinjiang (China).

Methods: According to the standard of esophageal cancer diagnosis, exclusion and epidemiological investigation of the experimental and control groups. Ion capture immunoassays were used to measure serum folic acid levels, while methylation-specific polymerase chain reaction was used to detect gene promoter methylation levels. Log-rank tests and Cox regression models were used to identify prognostic factors in the patient population.

Results: Serum folic acid levels in the experimental (cancer) group were significantly lower than in the control (non-cancer) group (Z = -9.13, P < 0.001). Furthermore, the methylation rates of MTHFR, CBS, MGMT, P16, FHIT, and RASSF1A in the experimental group were significantly higher than in the control group. Multivariate analysis identified depth of tumor invasion, regional lymph node metastasis, tumor-node-metastasis stage, and CBS and RASSF1A gene methylation status as independent prognostic factors; female gender and high serum folic acid levels were favorable prognostic factors.

Conclusions: Low serum folic acid level is a risk factor for esophageal cancer among ethic Kazakhs. Moreover, methylation of MTHFR, CBS, MGMT, P16, FHIT, and RASSF1A is closely related to esophageal cancer tumorigenesis.

Keywords: DNA methylation, esophageal cancer, folic acid metabolism, Kazakh people, prognosis.

Introduction

Esophageal cancer is one of the most common gastrointestinal malignancies. It ranks among the top eight global cancers in incidence rate and is the sixth leading cause of cancer-related deaths. Esophageal cancer mainly includes esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) and esophageal adenocarcinoma. Because of the significant differences in risk factors between the two tumor types, their distributions and incidence rates are distinct. Esophageal adenocarcinoma is prevalent in Europe and the United States, while ESCC is more common in Eastern countries, such as China 1-4. The 5-year overall survival rates range from 15% to 25% 1. China has the highest esophageal cancer incidence and mortality rates. Of the approximate 260,000 new patients diagnosed with esophageal cancer each year, 70% are in China, with ESCC accounting for 90% of cases 5. Xinjiang is one of the regions with the highest incidence rate of esophageal cancer in China. In particular, the mortality rate of the region's Kazakh population is much higher than that of the other ethnic groups in the same region (88.7 vs. 22.3 per 100,000), owing to the disease 6.

Folic acid is a water-soluble B vitamin and is one of the essential nutrients for maintaining body function. It is mainly found in citrus fruits, green leafy vegetables, beans, cereals, and animal livers 7. The active form of folic acid in the body is tetrahydrofolic acid, a metabolic coenzyme that functions in the synthesis of methionine. Folic acid also plays an important role in DNA synthesis, integrity, and stability 8. Folate deficiency may lead to DNA instability and strand breaks. The destruction of specific gene methylation patterns may not only affect susceptibility to ESCC, but also influence progression once the disease manifests 9.

Tumorigenesis is a complex multi-step, multi-stage process of single-gene and polygenic alterations. Modern tumor theory suggests that the formation of tumors at the genetic level involves both genetic and epigenetic factors. Genetic factors include gene mutations, loss of genetic heterozygosity, and microsatellite instability, while epigenetic factors include other non-gene-related changes that can be stably transmitted during development and cell proliferation (e.g., DNA methylation, covalent histone modification, chromatin remodeling, gene silencing, and the regulation of non-coding RNA). Epigenetic modifications can be regulated and reversed under certain conditions, thus providing new ideas for the prevention and treatment of tumors. DNA methylation is one of the most important epigenetic modifications. It plays a key role in tumorigenesis by regulating the inactivation of tumor suppressor genes 10. Hypermethylation of the promoter regions of tumor suppressor genes is associated with the occurrence and development of esophageal cancer 11. Such changes in methylation status may be facilitated by low serum folic acid levels. Therefore, we investigated the relationship between the hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes and features of esophageal cancer in order to advance methods for the prevention, early diagnosis, and treatment of the disease.

Materials and Methods

Patients and study design

This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Xinjiang Medical University (Xinjiang, China). All participants provided informed written consent. Research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The experimental group consisted of Kazakh patients who were preoperatively diagnosed with esophageal cancer using endoscopic, radiographic, and pathological findings at the First Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University in the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region of China between 2010 and 2015. The control group consisted of Kazakh patients from the same hospital with no tumors or digestive diseases who were admitted for unrelated conditions during the same period. The control patients were from the same region, were of the same gender, and were of a similar age (within 5 years) of the experimental group. Local annual esophageal cancer screening records confirmed that there was no evidence of esophageal cancer in the control group, although patients with infection, fever, autoimmune diseases, and active diseases were excluded.

Esophageal cancer diagnosis

The standard of diagnosis for esophageal cancer is (1) esophageal barium meal X-ray film showing esophageal stenosis (wall tube not smooth, mucosal damage), (2) computed tomography revealing the depth of tumor invasion and the presence or absence of metastatic lesions (vertical wall), (3) gastric endoscopy/esophagoscopy showing esophageal mucosal destruction, ulcers, and new cauliflower-like structures, (4) cytological examination, and (5) histological examination.

Epidemiological investigations

The general survey included the name, gender, age, marital status, education level, and economic income of the study participants. Clinicopathological characteristics included histological type, pathological type, tumor size, tumor differentiation, depth of tumor invasion, regional lymph node metastasis (LNM), distant metastasis, and tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) staging of esophageal cancer (experimental group only). Follow-up included surgery, termination of observation, survival time, and survival outcome (alive, lost to follow-up, death, or death from other causes).

Serum folic acid assay

Serum samples (0.5 mL) were collected and their folic acid content determined by an automated chemiluminescence immunoassay (ion-capture immunoassay). In this assay, folic acid forms part of a negatively charged reaction complex that is captured by a positively charged surface, which is composed of fiberglass coated with a quaternary ammonium polymer compound. According to the principles of positive and negative electrostatic binding, the reaction complex is adsorbed on the fiber surface. The principle of complex phase reaction by antigen-antibody reaction and parallel fluorescent labeling, by linking the negatively charged polyanion complexes adsorbed on the fiber surface, is positively charged and, after a series of reaction steps, the fluorescence-intensity change rate is calculated to determine the folic acid content.

DNA extraction and methylation modification

DNA was extracted from the blood using a genomic DNA extraction kit (TianGen BioTech Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). DNA methylation modification was performed using a DNA methylation modification kit (TianGen BioTech Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) and stored at -20°C.

PCR amplification and sequence verification

The modified DNA was used as a template for polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The primer sequences are shown in Table 1. Two rounds of amplification were performed (RASSF1A was only amplified in the second round) 12. The PCR products (10.0 μL) were separated by electrophoresis on a 1.0% agarose gel and analyzed by a gel imaging system (Tanon 2500, Shanghai Tanon Science and Technology Co., Ltd., China). The visualized amplification bands corresponded to unmethylated DNA, partially methylated DNA (where both methylated and unmethylated bands were observed for the same sample), and fully methylated DNA (where only methylated bands were observed). The latter two conditions were considered methylation-positive. For sequence validation, methylation-specific PCR amplification products were randomly extracted from one case each of completely methylated and unmethylated DNA and were subjected to cloning and sequencing verification.

Table 1.

Primer sequences for methylation-specific polymerase chain reaction

| Primer | Upstream primer 5'→3' | Downstream primer 5'→3' | T (˚C) | Length (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MTHFR-P1 | GAGGGGTTATGAGAAAAGATTTT | ACTCCTAATCTCAATCCCAAAA | 59 | 406 |

| MTHFR-M | GTGCGGGTTTTACGTTTATC | GAAAAAACCACGTAACCGTC | 60 | 174 |

| MTHFR-U | GGGTGTGGGTTTTATGTTTATT | AAAAAAACCACATAACCATCCC | 60 | 176 |

| CBS-P1 | GTGTTAGTTTTTGTTAGTGGATATTT | ACTAAACCTAATCCCCCC | 57 | 276 |

| CBS-M | TTTTACGTGGTAGAGATCGC | AACCTACAACGAAAAACACG | 60 | 148 |

| CBS-U | TTTTATGTGGTAGAGATTGT | AACCTACAACAAAAAACACAAAC | 60 | 148 |

| MGMT-P1 | GGTATTGGGAGTTAGGATTTTA | TTTTCCTATCACAAAAATAATCC | 56 | 423 |

| MGMT-M | TATAGGTTTTGGAGGTTGTTTTTAC | TAATAAAAATCCCGATCCTACTCG | 58 | 147 |

| MGMT-U | ATAGGTTTTGGAGGTTGTTTTTATG | AATAAAAATCCCAATCCTACTCAAA | 58 | 145 |

| P16-PCR1 | TTAGATAGAAAGGTGGTATGTGG | CCAAACCTTACAAAAAAAAAAA | 55 | 319 |

| P16-M | ATTTTGAGTGAAATTTATTTATCGG | ATACAAACCCAAAACAAAACGAA | 58 | 131 |

| P16-U | ATTTTGAGTGAAATTTATTTATTGG | ATACAAACCCAAAACAAAACAAA | 58 | 131 |

| FHIT-P1 | TTTAGAAAGATTTAGAGTGGGGA | AAACTACAATTCCCAAAAAACC | 58 | 398 |

| FHIT-M | AGAAATTTAGTTAGTGGGAAGTCGT | AAAAAAATTTAAAACATAAATCGCA | 60 | 167 |

| FHIT-U | AGAAATTTAGTTAGTGGGAAGTTGT | AAAAAAATTTAAAACATAAATCACA | 60 | 167 |

| RASSF1A-M | TTAGCGTTTAAAGTTAGCGAAGTAC | AAAATCGCACCACGTATACGTA | 60 | 241 |

| RASSF1A-U | TTAGTGTTTAAAGTTAGTGAAGTATGG | CACAAAAATCACACCACATATACATA | 60 | 245 |

Abbreviations: bp: base pair; M: methylation primer; P1: first round amplification primer; T: annealing temperature; U: unmethylation primer.

Statistical analyses

Data are presented as the mean ± standard error. The t-test was used to compare normally distributed data between groups. When the data were not normally distributed, a non-parametric test was applied. The Chi-square (χ2) or Fisher's exact test was used to compare rates between groups. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression survival analysis was used to identify significant prognostic factors. All statistical analyses were conducted using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences for Windows (software version 17.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

General distribution of participants

The cohort comprised 192 patients in the experimental group (65.1% men, 34.9% women; mean age, 58.3 ± 8.0 years) and 200 patients in the control group (71.0% men, 29.0% women; mean age, 58.4 ± 9.0 years). The χ2 test showed a good balance between the groups in terms of age, gender, and marital status. However, education level and economic income were significantly different between the groups (χ2 = 41.69, P < 0.001 and χ2 = 31.33, P < 0.001, respectively) (Table 2).

Table 2.

General characteristics of the study participants

| Characteristic | Experimental group (n = 192) | Control group (n = 200) | Total | χ2 | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 125 (65.1) | 142 (71.0) | 267 | 1.568 | 0.211 | |

| Female | 67 (34.9) | 58 (29.0) | 125 | |||

| Age (years) | ||||||

| <50 | 35 (18.2) | 45 (22.5) | 80 | 3.743 | 0.291 | |

| 50-59 | 78 (40.6) | 58 (29.0) | 155 | |||

| 60-69 | 67 (34.9) | 77 (38.5) | 125 | |||

| ≥70 | 12 (6.3) | 20 (10.0) | 32 | |||

| Education level | ||||||

| Below junior high school | 125 (65.1) | 65 (32.5) | 190 | 41.693 | <0.001 | |

| Junior high school and above | 67 (34.9) | 135 (67.5) | 202 | |||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 177 (92.2) | 178 (89.0) | 355 | 5.944 | 0.092 | |

| Widowed | 14 (7.3) | 17 (8.5) | 31 | |||

| Divorced | 0 (0.0) | 5 (2.5) | 5 | |||

| Unmarried | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 | |||

| Monthly income (RMB [¥]) | ||||||

| ≤1,000 | 139 (72.4) | 89 (44.5) | 228 | 31.327 | <0.001 | |

| >1,000 | 53 (27.6) | 111 (55.5) | 164 | |||

Comparison of serum folic acid levels between the experimental and control groups

The serum folic acid levels in the experimental and control groups were 6.4 ± 2.7 and 9.0 ± 4.1 nmol/L, respectively. The data were normally distributed, although the variance was not homogeneous. Rank-sum test analysis revealed that mean serum folic acid levels were significantly lower in the experimental group than in the control group (Z = -9.13, P < 0.001). Serum folic acid levels were stratified into four groups according to the quartiles of serum folic acid levels in the control group: ≤6.26, 6.27-8.12, 8.13-10.20, and >10.20 nmol/L, respectively. Single factor logistic regression analysis showed that the risk of esophageal cancer in the 6.27-8.12 nmol/L group was 0.35-fold that of the ≤6.26 nmol/L group (χ2 = 15.28, P < 0.001). Moreover, the risk of disease in the 8.13-10.20 nmol/L group was 0.17-fold that of the ≤6.26 nmol/L group (χ2 = 32.65, P < 0.001). Lastly, the risk of developing esophageal cancer in the >10.20 nmol/L group was 0.15-fold that of the ≤6.26 nmol/L group (χ2 = 34.64, P < 0.001) (Table 3). These results suggest that elevated serum folic acid levels may be protective against esophageal carcinogenesis.

Table 3.

The effects of different serum folic acid levels on the risk of esophageal cancer

| Serum folic acid level (nmol/L) | Experimental group (n = 192) | Control group (n = 200) | Wald χ2 | P-value | OR | 95.0% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤6.26 | 114 | 50 | - | - | 1.000 | - |

| 6.27-8.12 | 40 | 50 | 15.281 | <0.001 | 0.350 | 0.207-0.593 |

| 8.13-10.20 | 20 | 50 | 32.650 | <0.001 | 0.167 | 0.090-0.308 |

| >10.20 | 18 | 50 | 34.642 | <0.001 | 0.150 | 0.080-0.282 |

Abbreviations: CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; χ2: Chi-square.

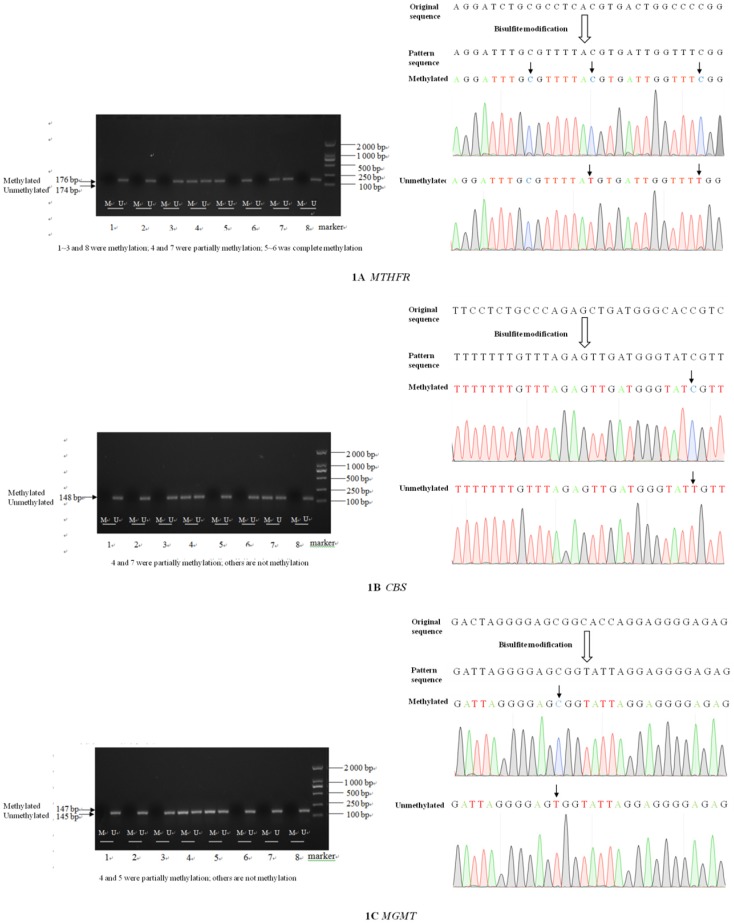

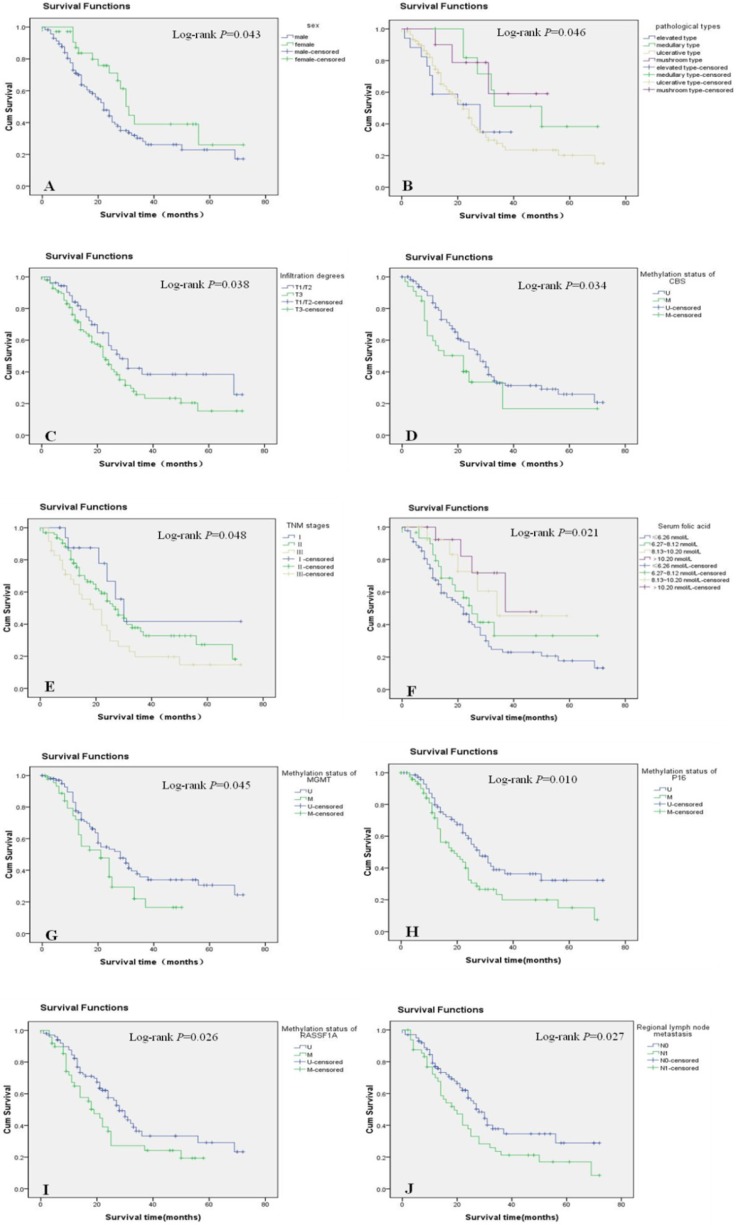

Electrophoresis and sequence verification of methylation-specific PCR amplification products

The sizes of the methylated and unmethylated products and sequence verification are shown in Figure 1A-F.

Figure 1.

Electrophoresis and sequence verification of methylation-specific polymerase chain reaction amplification products.

Detection of methylation rate in gene promoter regions

The methylation rates of MTHFR, CBS, MGMT, P16, FHIT, and RASSF1A were significantly higher in the experimental group than in the control group (P < 0.05) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Methylation of the promoter region of genes related to esophageal cancer in Kazakh patients

| Gene | Group | No methylation n (%) |

Partial methylation n (%) |

Methylation n (%) |

Total | χ2 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MTHFR | Exp. | 82 (42.7) | 61 (31.8) | 49 (25.5) | 192 | 45.144 | <0.001 |

| Control | 152 (76.0) | 26 (13.0) | 22 (11.0) | 200 | |||

| CBS | Exp. | 158 (82.3) | 19 (9.9) | 15 (7.8) | 192 | 18.465 | <0.001 |

| Control | 168 (84.0) | 32 (16.0) | 0 (0.0) | 200 | |||

| MGMT | Exp. | 137 (71.4) | 49 (25.5) | 6 (3.1) | 192 | 11.853 | 0.003 |

| Control | 153 (76.5) | 29 (14.5) | 18 (9.0) | 200 | |||

| P16 | Exp. | 105 (54.7) | 63 (32.8) | 24 (12.5) | 192 | 37.359 | <0.001 |

| Control | 166 (83.0) | 22 (11.0) | 12 (6.0) | 200 | |||

| FHIT | Exp. | 100 (52.1) | 48 (25.0) | 44 (22.9) | 192 | 46.608 | <0.001 |

| Control | 162 (81.0) | 32 (16.0) | 6 (3.0) | 200 | |||

| RASSF1A | Exp. | 112 (58.3) | 66 (34.4) | 14 (7.3) | 192 | 14.766 | 0.001 |

| Control | 153 (76.5) | 39 (19.5) | 8 (4.0) | 200 |

Abbreviations: Exp.: experimental; χ2: Chi-square.

Relationship between gene methylation status and the clinicopathological features of Kazakh patients with esophageal cancer

Analysis of the relationship between gene methylation status and the clinicopathological features of patients with esophageal cancer revealed that the methylation status of MTHFR differed significantly according to age, gender, and pathological type of esophageal cancer (χ2 = 12.80, P = 0.005; χ2 = 4.10, P = 0.043; and χ2 = 9.85, P = 0.020, respectively). CBS methylation status differed significantly according to pathological type, depth of tumor invasion, and TNM stage (χ2 = 24.46, P < 0.001; χ2 = 4.49, P = 0.034; and χ2 = 6.41, P = 0.041, respectively). MGMT methylation status differed significantly according to tumor size, tumor differentiation, regional LNM, and TNM stage (χ2 = 5.42, P = 0.020; χ2 = 7.41, P = 0.006; χ2 = 6.69, P = 0.010; and χ2 = 10.74, P = 0.005, respectively). P16 methylation status differed significantly according to the tumor differentiation, depth of tumor invasion, and TNM stage (χ2 = 6.36, P = 0.012; χ2 = 10.48, P = 0.001; and χ2 = 11.65, P = 0.003, respectively). FHIT methylation status differed significantly according to pathological type and TNM stage (χ2 = 15.48, P = 0.001 and χ2 = 12.56, P = 0.002, respectively). Finally, RASSF1A methylation status differed significantly according to tumor differentiation, regional LNM, and TNM stage (χ2 = 4.12, P = 0.042; χ2 = 14.88, P < 0.001; and χ2 = 6.71, P = 0.035, respectively).

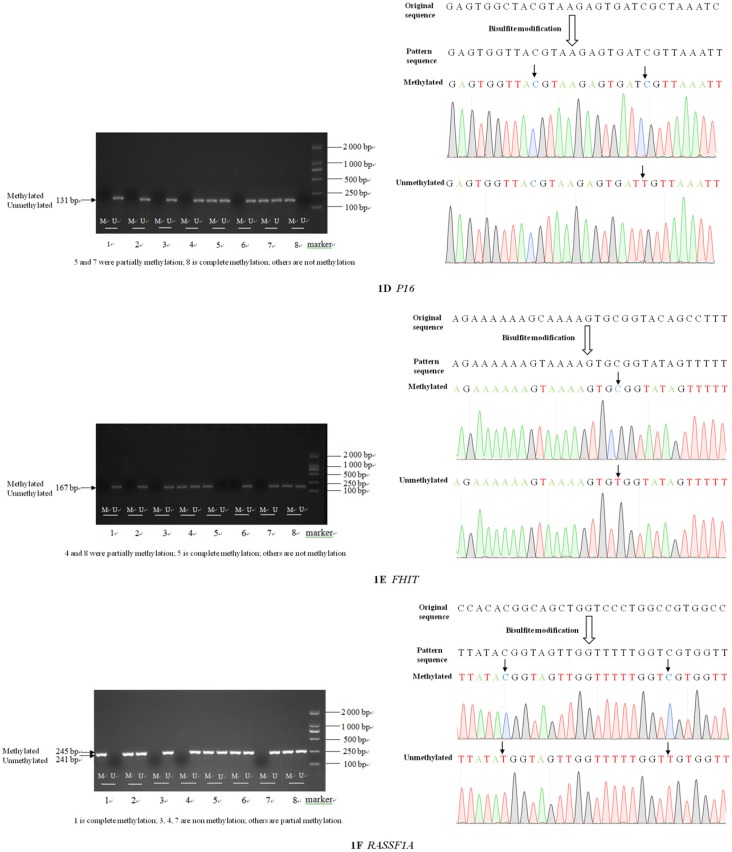

Prognostic factors for esophageal cancer

In the univariate analysis, gender, pathological type, depth of tumor invasion, regional LNM, TNM stage, serum folic acid levels, and the methylation status of CBS, MGMT, P16, and RASSF1A were significantly associated with the prognosis of esophageal cancer (P < 0.05) (Figure 2A-J). In contrast, age, histological type, tumor size, and the methylation status of MTHFR and FHIT were not significantly associated with the prognosis of esophageal cancer (data not shown). The survival rate was significantly higher in women than in men with esophageal cancer. Moreover, medullary carcinoma of the esophagus occurred significantly more frequently than other disease types. The survival rates of patients with T1/T2 esophageal cancer were significantly higher than those of patients with T3 esophageal cancer. Patients without LNM had higher survival rates than those with LNM. Additionally, survival significantly decreased as TNM stage progressed. Survival rates also decreased concomitantly with reductions in serum folic acid levels. Finally, patients with unmethylated CBS, MGMT, P16, and RASSF1A genes had longer survival times than those in whom these genes were methylated (Table 5).

Figure 2.

Survival curves of different groups of patients with esophageal cancer. Cum: cumulative; TNM: tumor-node-metastasis.

Table 5.

Univariate analysis of prognostic factors for esophageal cancer

| Factor | Survival rate | Median survival time (months) | Total | Log-rank test | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-year | 2-year | 3-year | Estimated (95.0% CI) | χ2 | P-value | |||

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 71.0 | 44.2 | 28.1 | 22.0 (17.8-26.2) | 116 | 4.108 | 0.043 | |

| Female | 87.1 | 71.1 | 39.0 | 31.0 (27.1-34.9) | 35 | |||

| Age (years) | ||||||||

| <50 | 85.1 | 56.4 | 26.3 | 26.0 (22.3-29.7) | 27 | 4.807 | 0.187 | |

| 50-59 | 65.4 | 34.9 | 23.3 | 16.0 (11.5-20.5) | 48 | |||

| 60-69 | 77.6 | 61.0 | 37.2 | 30.0 (23.5-36.5) | 64 | |||

| ≥70 | 70.7 | 42.4 | 28.3 | 21.0 (16.1-25.9) | 12 | |||

| Histological type | ||||||||

| SCC | 75.7 | 50.6 | 29.6 | 25.0 (21.2-28.8) | 139 | 0.212 | 0.645 | |

| ADC | 73.3 | 52.4 | 52.4 | 25.0 (21.1-28.9) | 12 | |||

| Pathological type | ||||||||

| Uplift | 58.8 | 52.3 | 34.9 | 28.0 (10.0-46.0) | 17 | 8.022 | 0.046 | |

| Medulla | 81.8 | 77.7 | 51.1 | 50.0 (25.2-74.8) | 13 | |||

| Ulcer | 74.8 | 43.1 | 24.2 | 22.0 (16.2-27.8) | 110 | |||

| Umbrella | 90.0 | 76.6 | 57.1 | 25.0 (20.2-29.8) | 11 | |||

| Tumor size (cm) | ||||||||

| <3.0 | 75.1 | 47.1 | 26.1 | 22.0 (9.5-34.5) | 34 | 0.001 | 0.971 | |

| ≥3.0 | 74.9 | 53.0 | 48.4 | 24.0 (20.8-27.2) | 117 | |||

| Depth of tumor invasion | ||||||||

| High-medium | 74.3 | 49.6 | 24.1 | 24.0 (20.9-27.1) | 75 | 0.609 | 0.435 | |

| Medium-low | 75.1 | 54.5 | 41.1 | 27.0 (17.0-37.0) | 76 | |||

| Differentiation | ||||||||

| T1/T2 | 87.1 | 56.5 | 38.4 | 28.0 (20.4-35.6) | 56 | 4.286 | 0.038 | |

| T3 | 72.6 | 44.7 | 24.1 | 22.0 (19.1-24.9) | 95 | |||

| Regional LNM | ||||||||

| N0 | 76.9 | 57.2 | 35.4 | 28.0 (22.7-33.3) | 101 | 4.907 | 0.027 | |

| N1 | 69.9 | 37.7 | 21.2 | 19.0 (12.7-25.3) | 50 | |||

| TNM stage | ||||||||

| I | 87.5 | 66.7 | 41.7 | 30.0 (22.9-37.1) | 18 | 6.068 | 0.048 | |

| II | 77.9 | 54.4 | 35.3 | 27.0 (21.0-33.0) | 97 | |||

| III | 64.8 | 36.0 | 19.7 | 19.0 (11.6-26.4) | 36 | |||

| Serum folic acid levels (nmol/L) | ||||||||

| ≤6.26 | 67.5 | 41.7 | 23.0 | 22.0 (17.0-27.0) | 90 | 9.710 | 0.021 | |

| 6.27-8.12 | 79.4 | 51.8 | 33.1 | 25.0 (18.4-31.6) | 30 | |||

| 8.13-10.20 | 92.3 | 61.7 | 45.4 | 34.0 | 16 | |||

| >10.20 | 92.3 | 73.8 | 47.9 | 37.0 | 15 | |||

| MTHFR | ||||||||

| Unmethylated | 74.0 | 49.2 | 38.0 | 24.0 (17.8-30.2) | 66 | 0.872 | 0.351 | |

| Methylated | 73.7 | 51.2 | 23.4 | 25.0 (20.6-29.4) | 85 | |||

| CBS | ||||||||

| Unmethylated | 80.7 | 54.5 | 31.8 | 28.0 (23.0-33.0) | 118 | 4.496 | 0.034 | |

| Methylated | 56.6 | 33.5 | 16.8 | 22.0 (11.5-32.5) | 33 | |||

| MGMT | ||||||||

| Unmethylated | 77.6 | 53.3 | 35.2 | 28.0 (19.5-36.5) | 105 | 4.007 | 0.045 | |

| Methylated | 72.0 | 35.8 | 17.8 | 21.0 (13.2-28.8) | 46 | |||

| P16 | ||||||||

| Unmethylated | 79.8 | 58.6 | 36.9 | 28.0 (22.2-33.8) | 75 | 6.694 | 0.010 | |

| Methylated | 71.5 | 32.4 | 19.9 | 19.0 (11.0-27.0) | 76 | |||

| FHIT | ||||||||

| Unmethylated | 75.8 | 44.4 | 30.4 | 24.0 (20.8-27.2) | 79 | 0.172 | 0.678 | |

| Methylated | 76.8 | 54.1 | 34.9 | 28.0 (19.2-36.8) | 72 | |||

| RASSF1A | ||||||||

| Unmethylated | 82.4 | 57.5 | 33.3 | 28.0 (23.4-32.6) | 102 | 4.926 | 0.026 | |

| Methylated | 64.8 | 36.3 | 24.3 | 19.0 (13.3-24.7) | 49 | |||

Abbreviations: ADC: adenocarcinoma; CI: confidence interval; LNM: lymph node metastasis; SCC: squamous cell carcinoma; TNM: tumor-node-metastasis; χ2: Chi-square.

Significant prognostic factors in the univariate analysis were entered into the Cox regression model for multivariate analysis, which revealed that the depth of tumor invasion, regional LNM, TNM stage, and CBS and RASSF1A gene methylation were independent prognostic factors for Kazakh patients with esophageal cancer. Female gender and serum folic acid levels were associated with a better prognosis (Table 6).

Table 6.

Multivariate analysis of prognostic factors for esophageal cancer

| Variable | Regression coefficient | SE | Wald χ2 | P-value | OR | 95.0% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | -0.597 | 0.267 | 4.981 | 0.026 | 0.751 | 0.526-0.930 |

| Depth of tumor invasion | 0.681 | 0.241 | 7.961 | 0.005 | 1.975 | 1.231-3.169 |

| Regional LNM | 0.831 | 0.207 | 16.135 | <0.001 | 2.295 | 1.530-3.443 |

| TNM stage | ||||||

| II | 0.468 | 0.214 | 4.789 | 0.029 | 1.596 | 1.050-2.426 |

| III | 0.649 | 0.237 | 7.509 | 0.006 | 1.914 | 1.203-3.046 |

| Serum folic acid levels (nmol/L) | ||||||

| 6.27-8.12 | -0.399 | 0.135 | 8.794 | 0.003 | 0.671 | 0.515-0.873 |

| 8.13-10.20 | -1.078 | 0.377 | 8.165 | 0.004 | 0.412 | 0.165-0.828 |

| >10.20 | -1.172 | 0.517 | 5.130 | 0.024 | 0.310 | 0.112-0.854 |

| CBS | 0.610 | 0.245 | 6.212 | 0.013 | 1.841 | 1.139-2.974 |

| RASSF1A | 0.569 | 0.226 | 6.355 | 0.012 | 1.766 | 1.135-2.749 |

Abbreviations: CI: confidence interval; LNM: lymph node metastasis; OR: odds ratio; SE: standard error; TNM: tumor-node-metastasis.

Discussion

DNA methylation mainly occurs in the gene promoter region that is rich in CpG islands, which causes changes in the chromatin structure, DNA conformation, DNA stability, and the interaction between DNA and protein to control gene expression 13. Esophageal cancer development is progressive, beginning with basal cell hyperplasia, dysplasia, carcinoma in situ, and finally advanced esophageal cancer. Aberrant methylation of tumor suppressor gene DNA can promote normal epithelial cells to transform into cancerous esophageal cells, which is an important factor in tumorigenesis 14. Tumorigenesis typically involves genome-wide hypomethylation accompanied by hypermethylation at specific sites. Ohta et al. 15 showed that abnormal methylation of DNA occurs in the precancerous stage of esophageal cancer and is an early molecular event that persists throughout the course of the disease. Unlike genetic changes, epigenetic modifications are reversible and can promote certain key tumor suppressor genes in tumors or precancerous lesions by demethylation to achieve early tumor prevention and even treatment of tumors 16. Therefore, to explore the potential of DNA methylation as a biomarker for early detection, diagnosis, and treatment of esophageal cancer, it is of particular importance to devise sound scientific strategies for the prevention and treatment of esophageal cancer.

The MTHFR gene encodes a key enzyme that is involved in folate metabolism. It may catalyze the irreversible conversion of 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate to 5-methyltetrahydrofolate, the main form of folic acid in the circulating blood, which promotes the conversion of homocysteine to methionine. The methyl donor, methionine, is further converted to S-adenosylmethionine 17. S-adenosylmethionine, a common methyl donor in vivo, plays an important role in DNA methylation. A previous study 9 showed that folic acid deficiency may increase the susceptibility to esophageal cancer and that folic acid is a protective factor for esophageal cancer. As a key enzyme for folic acid metabolism, changes in enzyme activity resulting from changes in the MTFHR gene may affect methyl group supply and DNA synthesis. Therefore, the MTFHR gene may be closely related to the occurrence of esophageal cancer.

The CBS gene encodes cystathionine beta-synthase, a key enzyme in the folic acid/homocysteine metabolic pathway. A previous study reported that methylation of the promoter region of the CBS gene leads to the inactivation of CBS messenger RNA, resulting in the loss of cystathionine beta-synthase protein expression, thereby affecting intracellular methylation metabolism and involvement in tumor development 18.

Inactivation of the MGMT gene causes DNA damage. Reduced O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase activity and expression of the repair enzyme weakens the efficiency of the repair process. As a result, gene mutations continue to accumulate, resulting in cancerous cells that form tumors. Several studies have reported on the emergence of MGMT gene methylation in the early stages of esophageal cancer 19.

The P16 gene (otherwise known as the MTS1 gene) is a basic gene involved in the regulation of the cell cycle. It negatively regulates cell proliferation and division and is the most common tumor suppressor gene in humans. Methylation of the P16 gene was detected in 81.0% of cases (n = 81) of esophageal cancer in the Das et al. 20 study, mainly due to the aberrant transcription of messenger RNA in the CpG island of the promoter, which blocked transcription. Therefore, it cannot play a corresponding role in the inhibition of cancer 21.

FHIT is a novel candidate tumor suppressor gene that is absent or inactive in many human tumors. Aberrant methylation of CpG islands in the promoter region of the FHIT gene can lead to epigenetic silencing, which results in loss of function of the gene and involvement in the development of cancer. Early ESCC has a poor prognosis in patients with hypermethylation of the FHIT gene 22.

RASSF1A is a novel candidate tumor suppressor gene that may inhibit tumor response by inactivation of the RAS/RASSF1/ERK pathway 23, 24. Mechanisms of RASSF1A gene inactivation include gene deletion, gene mutation, and promoter methylation. RASSF1A gene promoter methylation silences gene transcription and is the most important mechanism of inactivation. The methylation level of the CpG island promoter of the RASSF1A gene is not only closely related to the occurrence and development of esophageal cancer, but can also be used as an effective molecular marker for early diagnosis, targeted therapy, and prediction of prognosis in esophageal cancer. Therefore, there is great potential.

In this study, the methylation rates of MTHFR, CBS, MGMT, P16, FHIT, and RASSF1A were significantly higher in the experimental group than in the control group. MTHFR, CBS, MGMT, P16, FHIT, and RASSF1A were closely related to the development of esophageal cancer. A certain percentage of partial and full gene methylation events were present in both groups, suggesting that esophageal carcinogenesis involves specific timings and quantities of methylation events.

Univariate analysis showed that gender, pathological type, depth of tumor invasion, regional LNM, TNM stage, serum folic acid levels, and the methylation of CBS, MGMT, P16, and RASSF1A were associated with the prognosis of patients with esophageal cancer. Moreover, multivariate analysis revealed that depth of tumor invasion, regional LNM, TNM stage, and the methylation of CBS and RASSF1A were independent risk factors affecting the prognosis of Kazakh patients with esophageal cancer. Female gender and elevated serum folic acid levels were also protective factors that favorably influenced the prognosis of patients with esophageal cancer. The survival rates of patients with different pathological types and MGMT and P16 methylation patterns differed, but were not independent factors affecting overall prognosis. Depth of tumor invasion, regional LNM, and TNM stage were key predictors of eligibility for esophageal cancer surgery. Our findings also suggest that depth of tumor invasion is a risk factor for the prognosis of esophageal cancer, which may be related to esophageal serosa deficiency and local tumor spread. Esophageal cancer is characterized by local invasion, lymph node involvement, and blood-borne dissemination. The esophageal mucosa and submucosa contain abundant lymphatic capillaries, suggesting that LNM is an early event in esophageal cancer. Our study clearly demonstrates that such metastasis and the number of lymph nodes involved are important factors affecting the prognosis of patients with esophageal cancer.

Many factors have been reported to influence the prognosis of esophageal cancer. However, TNM stage is a commonly reported independent risk factor 25, which was also identified in the present study. Additionally, we identified CBS methylation status as an independent prognostic factor. Methylation of the CBS gene inactivates cystathionine beta-synthase protein expression. This affects intracellular methyl metabolism and may promote the occurrence and development of cancer. Moreover, Wang et al. 26 reported that the prognosis of patients with RASSF1A gene methylation is poor, which is also consistent with our findings. Methylation silencing of the RASSF1A gene activates the RAS/RASSF1/ERK pathway, which promotes cell proliferation, including in an oncogenic manner 27.

There was no significant effect of gender on the prognosis of patients with esophageal cancer. However, a previous study 28 reported that women with esophageal cancer have a better prognosis than men, which may be related to the earlier diagnosis of female patients. It has also been reported 29 that alcohol may inhibit natural killer cell activity and promote tumor metastasis. As such, chronic alcoholism can inhibit the innate immune response. Case-control and cohort studies have identified smoking and excessive drinking as risk factors for esophageal cancer, especially among men. For example, Hidaka et al. 30 reported that a greater proportion of men with esophageal cancer had a poorer prognosis than women, which could be related to higher alcohol consumption and smoking among men. Estrogen receptor has been found to be expressed in esophageal cancer cells 31. Since estrogen can inhibit tumor cell growth, it may influence the development of esophageal cancer. In our study, women with esophageal cancer had a better prognosis than men, which may be attributed to the aforementioned factors.

We found that elevated serum folic acid levels in patients with esophageal cancer were associated with prolonged median survival. Serum folic acid is, therefore, a favorable prognostic factor in Kazakh patients with esophageal cancer, which is consistent with the study by Lu et al. 32. The benefits of folic acid may be related to its role in one-carbon metabolism. Folic acid is reliant on exogenous intake. Therefore, it is recommended that Kazakh residents in Xinjiang increase their intake by consuming more fruits and vegetables that are rich in folic acid.

Due to their reversibility, epigenetic modifications, such as DNA methylation, may serve as potential reversible molecular targets for cancer treatment and chemoprevention. However, further investigations are required to fully understand the development of esophageal cancer and to provide better early detection methods, as well as, new treatment strategies.

The limitation of this study is that only Kazakh-related gene methylation has been associated with the prognosis of esophageal cancer and it has not been compared with that of the Han population. It has not been possible to compare the extent of methylation of related genes between different ethnic groups. We aim to address this in future work.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the First Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University (Xinjiang, China). The authors also wish to thank Editage (www.editage.cn) for English language editing.

Abbreviations

- ESCC

esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- LNM

lymph node metastasis

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- TNM

tumor-node-metastasis

- χ2

Chi-square.

References

- 1.Domper Arnal MJ, Ferrández Arenas Á, Lanas Arbeloa Á. Esophageal cancer: Risk factors, screening and endoscopic treatment in Western and Eastern countries. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:7933–43. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i26.7933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li JY. Epidemiology of esophageal cancer in China. Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1982;62:113–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rasool S, A Ganai B, Syed Sameer A. et al. Esophageal cancer: associated factors with special reference to the Kashmir Valley. Tumori. 2012;98:191–203. doi: 10.1177/030089161209800203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rubenstein JH, Shaheen NJ. Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Management of Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:302–17.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.04.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang LL, Han JW, Wang XL. et al. Mechanism of Bufalin in inhibiting the migration of TE13 esophageal cancer cells. Chin J Cancer Prev Treat. 2016;23:837–43. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang SY, Yin D, Deng YC. et al. Methylation of the ALDH1L1 gene in esophageal carcinoma in Kazakh and relationship with prognosis. Carcinogenesis, Teratogenesis & Mutagenesis. 2014;26:35–9. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Falk GW. Risk factors for esophageal cancer development. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2009;18:469–85. doi: 10.1016/j.soc.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu C, Xie H, Wang F. et al. Diet folate, DNA methylation and genetic polymorphisms of MTHFR C677T in association with the prognosis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:91. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yin Y, Palida T, Chen Y. Meta-analysis of the relationship between folate levels and esophageal cancer. J Xinjiang Med Univ. 2015;38:748–53. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li L, Deng YC, Zhao Y. et al. Methylation of the FHIT gene in esophageal carcinoma in Kazakh and Han and relationship with prognosis. Carcinogenesis, Teratogenesis & Mutagenesis. 2012;24:132–5. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gyobu K, Yamashita S, Matsuda Y. et al. Identification and validation of DNA methylation markers to predict lymph node metastasis of esophageal squamous cell carcinomas. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:1185–94. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1393-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhen Y, Yin Y, Xu Y. et al. The relationship of methylation level of MTHFR and CBS with Kazakh esophageal cancer. J Xinjiang Med Univ. 2017;40:535–9. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Portela A, Esteller M. Epigenetic modifications and human disease. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:1057–68. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agarwal A, Polineni R, Hussein Z. et al. Role of epigenetic alterations in the pathogenesis of Barrett's esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2012;5:382–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohta M, Mimori K, Fukuyoshi Y. et al. Clinical significance of the reduced expression of G protein gamma 7 (GNG7) in oesophageal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2008;98:410–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng HC, Ma J. Epigenetic modifications and tumors. J Intern Med Concepts Pract. 2009;4:72–5. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang K. Association between polymorphisms of MTHFR and the genetic susceptibility to esophageal cancer in Henan Han population. Zhenzhou Univ; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tu XH, H SX, L WS. et al. Correlation of methylation of CpG island in cystathionine beta synthase promoter and clinicopathological features in colorectal cancer. Chin J Oncol. 2013;35:351–355. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-3766.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.S YY. Study on the function of MGMT in esophageal cancer and its association with its function related genes. Southeast Univ; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Das M, Saikia BJ, Sharma SK. et al. p16 hypermethylation: a biomarker for increased esophageal cancer susceptibility in high incidence region of North East India. Tumour Biol. 2015;36:1627–42. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2762-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li CY, Xu ZX, Tan JJ. Methylation of P16 gene and the research progress of esophageal cancer. J Med Res. 2012;41:157–61. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee EJ, Lee BB, Kim JW. et al. Aberrant methylation of Fragile Histidine Triad gene is associated with poor prognosis in early stage esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:972–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Donninger H, Vos MD, Clark GJ. The RASSF1A tumor suppressor. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:3163–72. doi: 10.1242/jcs.010389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ram RR, Mendiratta S, Bodemann BO. et al. RASSF1A inactivation unleashes a tumor suppressor/oncogene cascade with context-dependent consequences on cell cycle progression. Mol Cell Biol. 2014;34:2350–8. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01506-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirahara N, Matsubara T, Hayashi H. et al. Impact of inflammation-based prognostic score on survival after curative thoracoscopic esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41:1308–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2015.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang C, Mao W, Ling Z. Methylation of Tumor Suppressor Genes and Clinical Significance in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Chin J Gastroenterol. 2012;17:19–22. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ram RR, Mendiratta S, Bodemann BO. et al. RASSF1A inactivation unleashes a tumor suppressor/oncogene cascade with context-dependent consequences on cell cycle progression. Mol Cell Biol. 2014;34:2350–8. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01506-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rohatgi PR, Correa AM, Swisher SG. et al. Gender-based analysis of esophageal cancer patients undergoing preoperative chemoradiation: differences in presentation and therapy outcome. Dis Esophagus. 2006;19:152–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2006.00557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bautista AP. Chronic alcohol intoxication primes Kupffer cells and endothelial cells for enhanced CC-chemokine production and concomitantly suppresses phagocytosis and chemotaxis. Front Biosci. 2002;7:a117–25. doi: 10.2741/a746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hidaka H, Hotokezaka M, Nakashima S. et al. Sex difference in survival of patients treated by surgical resection for esophageal cancer. World J Surg. 2007;31:1982–7. doi: 10.1007/s00268-007-9193-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tang S, Huang J, Dong JC. et al. Effects of sex on survival of patients with esophageal cancer from high- and low-incidence areas. Cancer Res Prev Treat. 2014;41:203–8. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jing C, Huang Z, Duan Y. et al. Folate intake, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase polymorphisms in association with the prognosis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13:647–51. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.2.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]