Abstract

Purpose To present an overview of the existing evidence on prognostic factors of (recurrent) sickness absence (SA) and return to work (RTW) among workers with a common mental disorder (CMD). This scoping review provides information about determinants for SA and RTW, which could be used to develop better interventions aimed at the prevention of SA and promotion of RTW among workers with a CMD. Methods Relevant articles were identified in PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO, PSYNDEX, and SINGLE up to October 2016. In order to be included, studies should provide insight into prognostic factors of SA or RTW of workers with a CMD. We classified all factors according to the domains of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Results Our searches identified 2447 possible relevant articles, of which 71 were included for data extraction. There is consistent evidence in ≥3 studies that previous episodes of CMD, higher symptom severity, previous absenteeism, co-morbidity, high job demands, low job control, high job strain, female gender, lower educational level, smoking behavior, and low perceived general health are predictors of SA in people with CMDs. Earlier RTW is consistently predicted by lower symptom severity, having no previous absenteeism, younger age, and positive expectations concerning sick-leave duration or RTW. Conclusions The amount of research on determinants for SA and RTW in workers with CMD has increased dramatically in recent years, although most studies are from the Netherlands and Scandinavia. There are some research gaps identified in this scoping review that need further attention in primary and secondary studies. Based on the summary of the evidence, we provide guidance for policy, practice and research.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10926-017-9730-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Common mental disorders, Sickness absence, Return to work, Prognostic factors, Scoping review

Introduction

Common mental disorders (CMDs) are long-lasting predictors of onset, duration and recurrence of sickness absence (SA), reduced productivity, work disability, and early retirement [1–3]. In the present study, the definition of CMD included anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, and stress-related disorders (adjustment disorders, burnout). Depression, for example, is estimated to be one of the ten leading contributors to disability in the world [4]. The prevalence of CMD among the general working population during the last 12 months preceding assessment has been estimated to be approximately 17.6% [5].

CMDs generate high direct and indirect costs for society at several levels [6, 7]. These not only have a financial burden on companies and governments, but also affect the wellbeing of individuals, who see their working- and earnings capacity reduced, or can no longer participate in the labor market. Tackling mental ill-health of the working-age population is becoming a key issue for labor market and social policies in OECD countries. Governments increasingly recognize that policy has to play a major role in keeping people with CMDs in employment or bringing those outside of the labor market back to it [8]. Therefore, understanding which factors help or hinder workers’ capacity to stay at work or successful return to work (RTW) when impaired by a CMD, is a relevant public health focus.

Only three systematic reviews have studied the prognostic factors of work outcomes in people among a working age population with mental illness [9–11]. Despite the relatively recent publication dates of these reviews, included studies were relatively outdated and focused not exclusively on CMDs. Although determinants for SA and RTW among people with a CMD have been studied in the past, an overview of these factors is lacking. From existing literature it is known that RTW-interventions for people with a CMD are scarce and that the effectiveness of RTW-interventions for workers with mental health problems is generally poor [12–15]. Clearly, there is a need to develop more adequate interventions to prevent SA and improve RTW for workers with a CMD, and also to carry on studies that investigate its effectiveness. When future interventions are designed based on the known prognostic factors for SA and RTW, their effectiveness can potentially be improved. Hence, there is a need for an overview of determinants for SA and RTW of workers with a CMD, and an indication of which determinants have the strongest prognostic value.

In this article we present a scoping review on the existing latest empirical evidence on the prognostic factors of SA and RTW among workers with a CMD. An overview of determinants for SA and RTW will allow us to report about the factors that have been studied so far, and to identify the omissions in the literature. Differences across countries will be discussed. The relevance of this scoping review was to improve the knowledge for researchers and practitioners on the factors that should be considered in designing better interventions aimed at preventing SA and improving RTW among the working population with a CMD.

Methods

This study was a scoping review, which uses a strict methodology for collecting, synthesizing, appraising and presenting findings from existing research on a topic [16]. A study protocol was designed a priori [17]. The methodological steps in this scoping review were adapted from Arksey and O’Malley [18]. These can be grouped into a framework of five main stages encompassing the whole process: (i) identifying the research question, (ii) identifying relevant studies, (iii) selecting studies for analysis, (iv) charting the data, and (v) collating, summarizing and reporting the results. Each stage of the research process is comprehensively described below.

Identifying the Research Question

The definition of the research question entailed a preliminary phase in which a broad set of questions were posed. The methodology of scoping reviews allows a post hoc narrowing of the research question and adoption of the criteria set a priori. Ultimately, the following research questions were defined:

Which potential risk factors for (recurrent) SA or RTW in workers with CMD have been studied so far?

What prognostic factors are related to SA due to CMDs?

What prognostic factors positively or negatively influence the (successful) RTW among employees with CMDs?

Which prognostic factors are related to the recurrence of SA due to CMDs?

Where are the omissions in the current knowledge or evidence?

Which recommendations can be made according to the results?

Identifying Relevant Studies

Relevant articles were identified by means of a computerized search up to 24 October 2016 in the bibliographic databases PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO, and PSYNDEX, which was followed by a manual search and a search for grey literature. The search strategy was initially formulated for PubMed and was adapted for use in the other databases. Controlled vocabulary search terms (MeSH terms, Emtree terms, PsycINFO and PSYNDEX Descriptors) and free text words were used. Three main terms about prognostic factors, SA and RTW, and CMD were combined with the Boolean operator ‘AND’ to identify studies (exact search strategy available upon request). In order to be included, studies should provide insight into determinants of (long-term) SA or RTW in workers with a CMD. We included systematic reviews of qualitative studies, prognostic studies, and primary studies (e.g. cross-sectional studies, cohort studies, case-control studies and qualitative studies). Narrative reviews, letters, editorials, commentaries, government reports, meeting abstracts, animal or human experimental studies, intervention studies (controlled and uncontrolled studies) were excluded. Additionally, we complemented the database search by a hand search of citations from 3 relevant systematic reviews retrieved by a systematic search in PubMed, EMBASE, PsycInfo and PSYNDEX [9–11], the reference lists of included primary studies, and a search for grey literature in the System for Information on Grey Literature in Europe (SINGLE: http://www.opengrey.eu). We also contacted experts in the field of mental disorders and occupational medicine for relevant studies.

Selecting Studies for Analysis

Two authors (AF/BW and ARS) independently screened the studies identified in each database on title and abstract. After this first selection, BW/ARS and HdV independently assessed the corresponding full versions of the articles to determine which articles should be included in the full review. Studies were excluded when both reviewers considered it not fulfilling the inclusion criteria. Discrepancies were solved by discussion; when needed a third reviewer (AF) was enrolled. The criteria for inclusion were developed in accordance to the PEO format for observational studies, where population (P) terms were combined with exposure (E) terms and outcomes (O) [19]. For an article to be included in this scoping review, it had to comply with the following three criteria:

Population Working-age population with a CMD, such as depressive disorders (ICD-10: F32-F34), anxiety disorders (ICD-10 diagnostic categories F40-F42), stress-related disorders, including adjustment disorders (ICD-10: F43) and somatoform disorders (ICD-10: F45), and burnout (ICD-10: Z73.0), but without severe mental disorders (schizophrenia, personality disorders, mental retardation, etc.). In the case that workers with other conditions were among the study population, it was necessary that a separate analysis was performed among the workers with a CMD. Cases where CMD was a comorbid condition, were also excluded. When more than 80 percent of the sample in a study had CMDs, the study was eligible for inclusion.

Exposure Studies evaluating the exposure to risk factors, or prognostic factors were included. When the research focus was only considering the CMD condition itself as prognostic factor, then the article was excluded.

Outcome SA, RTW or recurrent SA. The search included other outcomes, such as work ability, work satisfaction and work functioning, but ultimately in this scoping review we focused only on SA and RTW. Articles with the outcomes unemployment, work disability (not defined in terms of SA), work ability, work functioning, and (early) retirement were excluded.

Additionally, only studies published in English, German or Spanish were included.

Charting the Data

The relevant data for answering our research questions were summarized in a data extraction form by one of the authors (ARS). The accuracy of the extracted information was then corroborated by two other authors (HdV and AF), and improved or complemented when necessary.

We presented the data in chronological order of the outcomes SA, RTW, and recurrent SA. SA should be measured as the number of days or spells of absenteeism within a predetermined time frame, as a percentage in a predefined period, or as currently being absent or not. RTW should be related to an endpoint at which RTW is determined. We considered cessation of disability payments as an acceptable proxy for RTW. Comparison of studies using different RTW definitions appears valid as long as RTW status is not considered as a measure of functional status [20]. Recurrent SA always takes place after a period of RTW, and was defined as having recurrent SA at follow-up “yes” versus “no”, or defined as “time until recurrent SA”. The data extraction form included these main characteristics of the studies: authors, year of publication, geographic location of the study, type of study, time to follow-up, aim of the study, study population (general working population, specific occupational groups, patients with a mental disorder), prognostic factors under study, outcome measures used (definition or operationalization such as duration of SA, SA rates, time until RTW, RTW-rates, etc.), and the associations with corresponding confidence intervals (the maximal adjustment for confounders was chosen). These results are presented in Supplemental Table 1.

Collating, Summarizing and Reporting the Results

In this stage, we created an overview of all information relevant to answer our research questions. The characteristics of the included primary studies were numerically described, and thematically reported with referral to the research questions [21]. We classified all factors according to the domains of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) model, proposed by Heerkens et al.: disease related factors, body functions and structures, activity limitations, participation restrictions, environmental (work related) factors, and personal (work related) factors [22]. The ICF offers a valuable approach to understanding the contextual influences on employee mental health and work disability [23].

A detailed description of the features of the included primary studies allowed us to identify existent research gaps with respect to prognostic factors, outcome and study type. Based on the summary of this evidence, we discuss implications for policy, practice and research [21]. Additionally, in light of the gaps in research identified here, we were able to more clearly state what should be the scope of future systematic reviews or primary studies focusing on the topic of SA or RTW for workers with a CMD.

Results

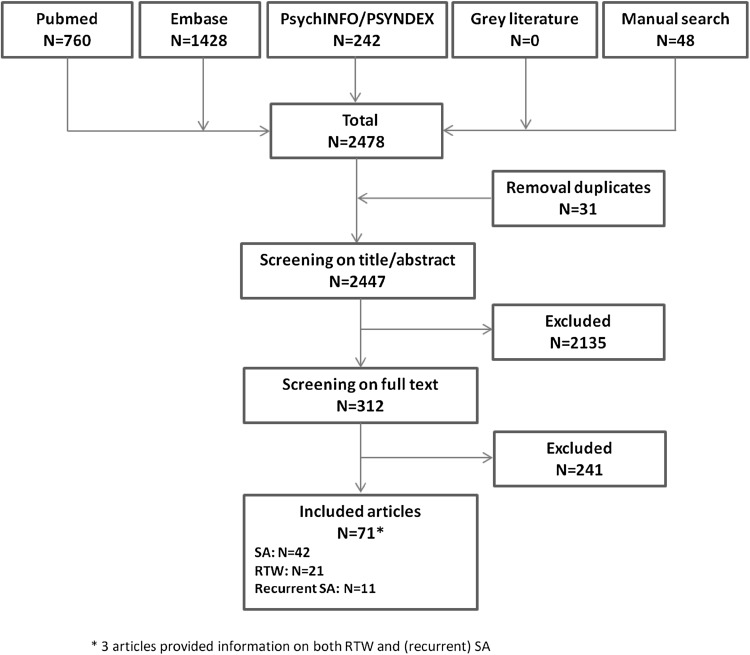

Figure 1 shows a flow chart with the results of the search process, in which the number of articles included in the scoping review are presented. Our searches identified 2478 articles. After removal of duplicates, a total of 2447 articles were screened for eligibility, of which 2135 were excluded because the inclusion criteria were not met. The hand search did add 48 articles to the results. After full-text screening of 312 articles, a total of 71 articles from 53 separate studies were deemed relevant and included for analysis. Three articles reported on both SA or RTW and recurrent SA.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of search results and screening stages

Articles that did not fulfill the predefined inclusion criteria were excluded. The reasons for exclusion after screening on title and abstract were because the study population, exposure or outcome were not relevant for this scoping review (children or adolescent, studies of disorders not meeting our CMD definition or only physical conditions, genetic conditions, etc.). At full-text screening, articles were excluded because no information on a CMD (sub)group was provided, no SA- or RTW related outcome was studied, or only diagnose itself was reported as prognostic factor. Study design (methodological papers dealing with specific methods to study RTW, randomized controlled trials and validation studies) was another reason for exclusion. Also language was a reason for exclusion. The reasons for exclusion in both steps were documented in all cases and can be provided upon request.

General Description of Articles

In Table 1 the general characteristics of the included articles are presented, categorized according to their main outcomes SA (n = 42), RTW (n = 21), and recurrent SA (n = 11). For SA, a total of 78 factors were studied and considered as potential predictors, for RTW 53 factors, and for recurrent SA 24 factors. Most studies were conducted after 2011, in earlier years studies on prognostic factors for SA or RTW in CMD were scarce. Although the studies were carried out in several countries, the predominant amount of studies was from the Netherlands and the Scandinavian countries. Just a few studies were included from the United States and no studies from Germany. Most studies were longitudinal cohort studies (N = 65), although in 6 studies a cross-sectional design was used, with a retrospective data collection on previous treatment, SA, or potential confounders. In 25 of all included studies, the cohort was a general working population, where workers with and without a CMD were compared. In the other 46 studies, a specific CMD population was analyzed longitudinally on SA and RTW outcomes.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included articles (n = 71)

| Sickness absence (N = 42) |

RTW (N = 21) |

Recurrent sickness absence (N = 11) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Year of publication | ||||||

| >2013 | 11 | 26 | 4 | 19 | 7 | 64 |

| 2010–2013 | 18 | 43 | 10 | 48 | 4 | 36 |

| 2006–2009 | 7 | 17 | 3 | 14 | ||

| 2002–2005 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 14 | ||

| <2002 | 3 | 7 | 1 | 5 | ||

| Country | ||||||

| Australia | 2 | 5 | 1 | 5 | ||

| Belgium | 2 | 5 | ||||

| Denmark | 5 | 12 | 4 | 19 | ||

| Finland | 6 | 14 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 18 |

| France | 1 | 2.3 | 1 | 5 | ||

| Great Britain | 1 | 2.3 | ||||

| Japan | 2 | 18 | ||||

| Norway | 2 | 5 | ||||

| Spain | 4 | 9 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 9 |

| Sweden | 5 | 12 | 2 | 9 | ||

| Canada | 1 | 2.3 | 1 | 5 | ||

| United States | 2 | 5 | 1 | 5 | ||

| The Netherlands | 11 | 26 | 9 | 43 | 6 | 55 |

| Study design | ||||||

| Longitudinal cohort study | 35 | 83 | 21 | 11 | 100 | |

| Cross-sectional study, with retrospective data collection | 7 | 17 | ||||

| Duration of study | ||||||

| >5 years | 5 | 12 | 1 | 5 | 7 | 64 |

| 1–5 years | 12 | 29 | 10 | 48 | 3 | 27 |

| 1 year | 15 | 36 | 8 | 38 | 1 | 9 |

| 6–12 months | 6 | 14 | 2 | 9 | ||

| Unclear | 4 | 9 | ||||

| Diagnose CMD group | ||||||

| Depression/anxiety | 8 | 19 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 9 |

| (Major) depression only | 17 | 40 | 3 | 14 | 2 | 18 |

| CMD | 14 | 33 | 12 | 57 | 8 | 73 |

| Burnout/stress | 3 | 7 | 4 | 19 | ||

| Unclear | 1 | 5 | ||||

| Study population | ||||||

| General working population | 21 | 50 | 3 | 14 | 3 | 27 |

| Specific CMD population | 21 | 50 | 18 | 86 | 8 | 73 |

Descriptive Numerical Summary

In Tables 2, 3 and 4 we present a descriptive numerical summary of all prognostic factors and their associations with respectively SA, RTW, and recurrent SA as outcome variables. For a complete description of all included studies, we refer to Supplemental Table 1.

Table 2.

Overview of prognostic factors of SA in workers with common mental disorders

| Factor | Result | Evidence | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disease related factors | |||

| Duration of illness last 5 years | Insufficient | ||

| van der Werff et al. [38] | No effect | SA last 6 months | |

| Past history of CMD | 3+, 3ne | ||

| Rytsala et al. [28] | Positive | SA or at work | |

| Souêtre et al. [24] | Positive | Past history of SA | |

| Hendriks et al. [60] | No effect | No SA, <2 or >2 weeks | |

| Recurrence | |||

| Rytsala et al. [28] | Positive | SA or at work | |

| van der Werff et al. [38] | No effect | SA last 6 months | |

| Hendriks et al. [60] | No effect | No SA, <2 or >2 weeks | |

| Symptom severity | 11+ | ||

| Rytsala et al. [28] | Positive | SA or at work | |

| Souêtre et al. [24] | Positive | Past history of SA | |

| van der Werff et al. [38] | Positive | SA last 6 months | |

| Verboom et al. [40] | Positive | days SA last 6 months | |

| Lerner et al. [27] | Positive | SA past 2 weeks | |

| Hees et al. [52] | Positive | % SA in last 4 weeks | |

| Hjarsbech et al. [45] | Positive | >3 weeks SA last year | |

| Hjarsbech et al. [51] | Positive | >3 weeks SA last year | |

| Lexis et al. [35] | Positive | Days SA last 10 months | |

| Stansfeld et al. [41] | Positive | Spells of SA 1991–1998 | |

| Hallsten et al. [46] | Positive | SA > 60 consecutive days | |

| Body functions and structures | |||

| Agreeableness | 2ne | ||

| Vlasveld et al. [53] | No effect | >2 weeks SA last 6 months | |

| Verboom et al. [40] | No effect | Days SA last 6 months | |

| Conscientiousness | 1+, 1− | ||

| Vlasveld et al. [53] | Negative | >2 weeks SA last 6 months | |

| Verboom et al. [40] | Positive | Days SA last 6 months | |

| Extraversion | 1−, 1ne | ||

| Vlasveld et al. [53] | Negative | >2 weeks SA last 6 months | |

| Verboom et al. [40] | No effect | Days SA last 6 months | |

| Openness | 2ne | ||

| Vlasveld et al. [53] | No effect | >2 weeks SA last 6 months | |

| Verboom et al. [40] | No effect | Days SA last 6 months | |

| Neuroticism | 2+ | ||

| Vlasveld et al. [53] | Positive | >2 weeks SA last 6 months | |

| Verboom et al. [40] | Positive | Days SA last 6 months | |

| Locus of control | Insufficient | ||

| Vlasveld et al. [53] | Negative | >2 weeks SA last 6 months | |

| Sleeping problems | 2+ | ||

| Lerner et al. [27] | Positive | SA past 2 weeks | |

| Salo et al. [48] | Positive | SA episode > 9 days | |

| Mental distress | 2+ | ||

| Foss et al. [36] | Positive | >8 weeks SA last 5 years | |

| Roelen et al. [57] | Positive | >3 weeks SA last year | |

| Fatigue severity | Insufficient | ||

| Roelen et al. [56] | Positive ♂ No effect ♀ |

>3 weeks SA last year | |

| Reduced concentration | Insufficient | ||

| Roelen et al. [56] | Positive ♂ No effect ♀ |

>3 weeks SA last year | |

| Activities | |||

| Activity limitations at work | Insufficient | ||

| Sanderson et al. [23] | No effect | SA days last 4 weeks | |

| Low level of physical activity | 1+, 1ne | ||

| Verboom et al. [40] | Positive | Days SA last 6 months | |

| Mather et al. [63] | No effect | SA spell last 5 years | |

| (Work) participation | |||

| Past history of absenteeism | 5+ | ||

| Souêtre et al. [24] | Positive | Past history of SA | |

| Hallsten et al. [46] | Positive | SA > 60 consecutive days | |

| Smith et al. [58] | Positive | Previous claim SA | |

| Riihimaki et al. [59] | Positive | Time spent SA last 5 years | |

| Elovainio et al. [50] | Positive | SA > 9 days last year | |

| Environmental factors | |||

| Family history of depression | Insufficient | ||

| Verboom et al. [40] | No effect | Days SA last 6 months | |

| Previous psychiatric treatment | 1+, 1ne | ||

| Elovainio et al. [50] | Positive | SA > 9 days last year | |

| Gasse et al. [49] | No effect | SA > 2 weeks | |

| Size social network | Insufficient | ||

| Verboom et al. [40] | No effect | Days SA last 6 months | |

| Social support (partner, friends) | Insufficient | ||

| Verboom et al. [40] | No effect | Days SA last 6 months | |

| Having had social assistance | Insufficient | ||

| Riihimaki et al. [59] | No effect | Time spent SA last 5 years | |

| Treatment condition (psychiatrist and psychologist vs no specialist) | Insufficient | ||

| Catalina-Romero et al. [39] | No effect | SA duration | |

| Environmental work related factors | |||

| Autonomy | Insufficient | ||

| Smith et al. [58] | No effect | Days of full SA last 2 years | |

| Benefit plan features (days between injury date and 1st day of compensation) | Insufficient | ||

| Smith et al. [58] | Positive | Days of full SA last 2 years | |

| Coworker support | 2ne | ||

| Munir et al. [44] | No effect | ≥3 weeks SA last 2 years | |

| Clumeck et al. [34] | No effect | SA incidence > 28 days | |

| Decision latitude | Insufficient | ||

| Munir et al. [44] | Negative | ≥3 weeks SA last 2 years | |

| Effort reward imbalance | 2ne | ||

| Janssens et al. [55] | No effect | SA ≥ 15 days last year | |

| Norlund et al. [43] | No effect | Risk of unchanged SA level | |

| Employment type (full-time vs part-time) | Insufficient | ||

| Smith et al. [58] | No effect | Days of full SA last 2 years | |

| Having a non-permanent contract | Insufficient | ||

| Real et al. [64] | Negative | Long-term SA > 60 days | |

| Function with time pressure | Insufficient | ||

| Smith et al. [58] | Positive | Days of full SA last 2 years | |

| Industry-sector | Insufficient | ||

| Smith et al. [58] | No effect | Days of full SA last 2 years | |

| Job control | 3−, 2ne | ||

| Virtanen et al. [33] | Negative | SA > 7 days | |

| Clumeck et al. [34] | Negative | SA incidence > 28 days | |

| Norlund et al. [43] | Negative | Risk of unchanged SA level | |

| Janssens et al. [55] | No effect | SA ≥ 15 days last year | |

| Mather et al. [63] | No effect | SA spell last 5 years | |

| Job demands | 5+, 5ne | ||

| Virtanen et al. [33] | Positive ♀ No effect ♂ |

SA > 7 days | |

| Clumeck et al. [34] | Positive ♂ No effect ♀ |

SA incidence > 28 days | |

| Norlund et al. [43] | No effect | Risk of unchanged SA level | |

| Janssens et al. [55] | No effect | SA ≥ 15 days last year | |

| Hjarsbech et al. [51] | No effect | >3 weeks SA last year | |

| Kivimaki et al. [37] | Positive | SA (yes vs no) | |

| Melchior et al. [31] | Positive | Days of SA | |

| Mather et al. [63] | Positive | SA spell last 5 years | |

| Job strain | 3+, 1ne | ||

| Virtanen et al. [33] | Positive | SA > 7 days | |

| Clumeck et al. [34] | Positive | SA incidence > 28 days | |

| Janssens et al. [55] | No effect | SA ≥ 15 days last year | |

| Mather et al. [63] | Positive | SA spell last 5 years | |

| Iso-strain (job strain and low support) | 2+, 1ne | ||

| Clumeck et al. [34] | Positive ♂ | SA incidence > 28 days | |

| No effect ♀ | |||

| Mather et al. [63] | Positive | SA spell last 5 years | |

| Organizational justice | 2− | ||

| Elovainio et al. [50] | Negative | SA > 9 days last year | |

| Hjarsbech et al. [54] | Negative | >3 weeks SA last year | |

| Overtime work > once a month | Insufficient | ||

| Norlund et al. [43] | No effect | Risk of unchanged SA level | |

| Predictability of work | Insufficient | ||

| Hjarsbech et al. [51] | No effect | >3 weeks SA last year | |

| Quality of leadership | 1−, 1ne | ||

| Munir et al. [44] | Negative | ≥ 3 weeks SA last 2 years | |

| Hjarsbech et al. [51] | No effect | >3 weeks SA last year | |

| Supervisor support | 1−, 2ne | ||

| Clumeck et al. [34] | No effect | SA incidence > 28 days | |

| Foss et al. [36] | Negative | >8 weeks SA last 5 years | |

| Janssens et al. [55] | No effect | SA ≥ 15 days last year | |

| Work environment | Insufficient | ||

| Sanderson et al. [23] | No effect | SA in days last 4 weeks | |

| Work pace | Insufficient | ||

| Hjarsbech et al. [51] | No effect | >3 weeks SA last year | |

| Work stress | Insufficient | ||

| Verboom et al. [40] | Negative | Days SA last 6 months | |

| Working with people | Insufficient | ||

| Norlund et al. [43] | No effect | Risk of unchanged SA level | |

| Personal factors | |||

| Older age | 6+, 2−, 6ne | ||

| Druss et al. [26] | Negative | Days SA last year | |

| Lerner et al. [27] | No effect | SA past 2 weeks | |

| Rytsala et al. [28] | Positive | SA or at work | |

| Vaez et al. [32] | Negative | Days SA last year | |

| Foss et al. [36] | No effect ♀ Positive ♂ |

>8 weeks SA last 5 years | |

| van der Werff et al. [38] | No effect | SA last 6 months | |

| Catalina-Romero et al. [39] | Positive | SA duration | |

| Hallsten et al. [46] | No effect | SA > 60 consecutive days | |

| Verboom et al. [40] | No effect | Days SA last 6 months | |

| Catalina-Romero et al. [47] | Positive | SA ≥ 6 months | |

| Gasse et al. [49] | Positive | SA > 2 weeks | |

| Riihimaki et al. [59] | No effect | Time spent SA last 5 years | |

| Real et al. [64] | Positive | Long-term SA > 60 days | |

| Gender (female vs male) | 6+, 1−, 8ne | ||

| Laitinen-Krispijn and Bijl [25] | Negative | ≥1 spell of SA last year | |

| Lerner et al. [27] | No effect | SA past 2 weeks | |

| Rytsala et al. [28] | Positive | SA or at work | |

| Vaez et al. [32] | No effect | Days SA last year | |

| Clumeck et al. [34] | No effect | SA incidence > 28 days | |

| Catalina-Romero et al. [39] | Positive | SA duration | |

| Foss et al. [36] | Positive | >8 weeks SA last 5 years | |

| van der Werff et al. [38] | No effect | SA last 6 months | |

| Hallsten et al. [46] | Positive | SA > 60 consecutive days | |

| Smith et al. [58] | No effect | Days of full SA last 2 years | |

| Gasse et al. [49] | Positive | SA > 2 weeks | |

| Elovainio et al. [50] | Positive | SA > 9 days last year | |

| Verboom et al. [40] | No effect | Days SA last 6 months | |

| Riihimaki et al. [59] | No effect | Time spent SA last 5 years | |

| Real et al. [64] | No effect | Long-term SA > 60 days | |

| High educational level | 4−, 1ne | ||

| Lerner et al. [27] | Negative | SA past 2 weeks | |

| Foss et al. [36] | Negative | >8 weeks SA last 5 years | |

| Catalina-Romero et al. [39] | Negative | SA duration | |

| Verboom et al. [40] | No effect | Days SA last 6 months | |

| Gasse et al. [49] | Negative | SA > 2 weeks | |

| Socio-economic position | 1+, 1−, 1ne | ||

| Vaez et al. [32] | No effect | Days SA last year | |

| Virtanen et al. [33] | Positive | SA > 7 days | |

| Elovainio et al. [50] | Negative | SA > 9 days last year | |

| Household income | Insufficient | ||

| Verboom et al. [40] | No effect | Days SA last 6 months | |

| Cohabiting with children | 1+, 1ne | ||

| Hallsten et al. [46] | No effect | SA > 60 consecutive days | |

| Gasse et al. [49] | Positive | SA > 2 weeks | |

| Co-morbidity | 6+, 3ne | ||

| Druss et al. [26] | Positive | Days SA last year | |

| Buist-Bouwman et al. [29] | Positive | Days SA last year | |

| Verboom et al. [40] | No effect | Days SA last 6 months | |

| Gasse et al. [49] | No effect | SA > 2 weeks | |

| Hallsten et al. [46] | Positive | SA > 60 consecutive days | |

| Catalina-Romero et al. [47] | Positive | SA ≥ 6 months | |

| van der Werff et al. [38] | No effect | SA last 6 months | |

| Hendriks et al. [60] | Positive | No SA, <2 or >2 weeks | |

| Riihimaki et al. [59] | Positive | Time spent SA last 5 years | |

| Adverse life events | Insufficient | ||

| Verboom et al. [40] | No effect | Days SA last 6 months | |

| Childhood trauma | Insufficient | ||

| Verboom et al. [40] | No effect | Days SA last 6 months | |

| Smoking behavior | 3+, 2ne | ||

| Elovainio et al. [50] | Positive | SA > 9 days last year | |

| Hallsten et al. [46] | No effect | SA > 60 consecutive days | |

| Foss et al. [36] | Positive ♀ No effect ♂ |

> 8 weeks SA last 5 years | |

| Mather et al. [63] | Positive | SA spell last 5 years | |

| Alcohol use | Insufficient | ||

| Mather et al. [63] | No effect | SA spell last 5 years | |

| Unhealthy behavior | Insufficient | ||

| Mather et al. [63] | Positive | SA spell last 5 years | |

| Good general health perception | 4− | ||

| Lerner et al. [27] | Negative | SA past 2 weeks | |

| Foss et al. [36] | Negative | >8 weeks SA last 5 years | |

| Peterson et al. [42] | Negative | >90 days SA last 3.5 years | |

| Roelen et al. [61] | Negative | SA > 16 consecutive days | |

| SF-12 domains | |||

| Poor physical functioning | Insufficient | ||

| Roelen et al. [61] | No effect | SA > 16 consecutive days | |

| Poor physical role limitations | Insufficient | ||

| Roelen et al. [61] | No effect | SA > 16 consecutive days | |

| Bodily pain | Insufficient | ||

| Roelen et al. [61] | No effect | SA > 16 consecutive days | |

| Poor vitality | Insufficient | ||

| Roelen et al. [61] | Positive | SA > 16 consecutive days | |

| Poor social functioning | Insufficient | ||

| Roelen et al. [61] | Positive | SA > 16 consecutive days | |

| Poor emotional role limitations | Insufficient | ||

| Roelen et al. [61] | Positive | SA > 16 consecutive days | |

| Poor mental health | Insufficient | ||

| Roelen et al. [61] | Positive | SA > 16 consecutive days | |

| Competitiveness | Insufficient | ||

| Moriana and Herruzo [30] | No effect | SA (yes vs no) | |

| Hostility | Insufficient | ||

| Moriana and Herruzo [30] | No effect | SA (yes vs no) | |

| Avoidance behavior | Insufficient | ||

| Hendriks et al. [60] | No effect | No SA, <2 or >2 weeks | |

| Personal work related factors | |||

| Work motivation | Insufficient | ||

| Roelen et al. [56] | Positive ♂ No effect ♀ |

>3 weeks SA last year | |

| Job satisfaction | Insufficient | ||

| Moriana and Herruzo [30] | Negative | SA (yes vs no) | |

| Bullying | Insufficient | ||

| Janssens et al. [55] | Positive | SA ≥ 15 days last year | |

| Covert coping towards supervisors and coworkers | Insufficient | ||

| Norlund et al. [43] | Negative | Risk of unchanged SA level | |

| Over commitment | Insufficient | ||

| Norlund et al. [43] | Negative | Risk of unchanged SA level | |

| Exhaustion | 2+ | ||

| Moriana and Herruzo [30] | Positive | SA (yes vs no) | |

| Peterson et al. [42] | Positive | >90 days SA last 3.5 years | |

| Disengagement | Insufficient | ||

| Peterson et al. [42] | No effect | >90 days SA last 3.5 years | |

| White vs blue collar | Insufficient | ||

| Catalina-Romero et al. [47] | Negative | SA ≥ 6 months | |

| Occupational category | 1+, 2ne | ||

| Lerner et al. [27] | No effect | SA past 2 weeks | |

| Hallsten et al. [46] | No effect | SA > 60 consecutive days | |

| Real et al. [64] | Positive | Long-term SA > 60 days | |

| Being a shift worker | Insufficient | ||

| Norder et al. [62] | No effect | Temporary SA | |

| Being self-employed | Insufficient | ||

| Real et al. [64] | Positive | Long-term SA > 60 days | |

+ positive related with SA, − negative related with SA, ne not related with SA

Table 3.

Overview of prognostic factors of RTW in workers with common mental disorders

| Factor | Result | Evidence | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disease related factors | |||

| Symptom severity | 4−, 2ne | ||

| Hees et al. [76] | Negative | Full RTW > 4 weeks | |

| Brouwer et al. [72] | No effect | Time to full RTW | |

| Brouwers et al. [71] | Negative | Full RTW (yes vs no) | |

| Vemer et al. [80] | No effect | Full RTW > 4 weeks | |

| Dewa et al. [67] | Negative | RTW part-time or full-time | |

| Hoedeman et al. [73] | Negative | Time until complete RTW | |

| Duration of illness | Insufficient | ||

| Brouwers et al. [71] | Negative | Full RTW (yes vs no) | |

| Body functions and structures | |||

| Conscientiousness | Insufficient | ||

| Hees et al. [76] | Positive | Full RTW > 4 weeks | |

| Activities | |||

| No factors were studied multivariate | |||

| (Work) participation | |||

| (Duration of) previous absenteeism | 4− | ||

| Engstrom and Janson [70] | Negative | RTW after SA > 28 days | |

| Nielsen et al. [74] | Negative | Time to RTW | |

| Brouwers et al. [71] | Negative | Full RTW (yes vs no) | |

| Prang et al. [85] | Negative | Time to sustained RTW > 30 days | |

| Full-time sick leave at baseline | Insufficient | ||

| Netterstrøm et al. [83] | Negative | RTW after 1 year (yes vs no) | |

| Environmental factors | |||

| Benefit plan features | |||

| High deductible | Insufficient | ||

| Salkever et al. [66] | Negative | Time to RTW (claim duration) | |

| Longer preexisting condition exclusion period | Insufficient | ||

| Salkever et al. [66] | Negative | Time to RTW (claim duration) | |

| Having a carve out | Insufficient | ||

| Salkever et al. [66] | Negative | Time to RTW (claim duration) | |

| Mental health benefits and services availability | Insufficient | ||

| Salkever et al. [66] | Positive | Time to RTW (claim duration) | |

| Disability management practices | Insufficient | ||

| Salkever et al. [66] | Positive | Time to RTW (claim duration) | |

| Long term disability policy provisions | |||

| Higher ratio disability benefits to predisability salary | Insufficient | ||

| Salkever et al. [66] | Negative | Time to RTW (claim duration) | |

| Inability to perform own occupation rather than any appropriate occupation | Insufficient | ||

| Salkever et al. [66] | Negative | Time to RTW (claim duration) | |

| Duration to identification of illness by the Occupational Health Service | Insufficient | ||

| Brouwer et al. [72] | No effect | Time to full RTW | |

| General social support | Insufficient | ||

| Brouwer et al. [72] | No effect | Time to full RTW | |

| Consulting a Psychologist or psychiatrist | Insufficient | ||

| Prang et al. [85] | Negative | Time to sustained RTW > 30 days | |

| Treatment condition | 2ne | ||

| Brouwers et al. [71] | No effect | Full RTW (yes vs no) | |

| Vemer et al. [80] | No effect | Full RTW > 4 weeks | |

| Environmental work related factors | |||

| Employment type (private or municipal) | 1−, 1ne | ||

| Nielsen et al. [77] | Negative | Time to RTW (benefits stopped) | |

| Engstrom and Janson [70] | No effect | RTW after SA > 28 days | |

| Size of workplace small | 1−, 1ne | ||

| Nielsen et al. [77] | No effect | Time to RTW (benefits stopped) | |

| Prang et al. [85] | Negative | Time to sustained RTW > 30 days | |

| Work week > 36 h | Insufficient | ||

| Vemer et al. [80] | Negative | Full RTW > 4 weeks | |

| High decision latitude | Insufficient | ||

| Vemer et al. [80] | Negative | Full RTW > 4 weeks | |

| Low decision authority | Insufficient | ||

| Netterstrøm et al. [83] | Negative | RTW after 1 year (yes vs) | |

| Variety in work | Insufficient | ||

| Norder et al. [84] | Positive | Time until full RTW | |

| High job demands | Insufficient | ||

| Netterstrøm et al. [83] | Negative | RTW after 1 year (yes vs no) | |

| Supervisory behavior | |||

| Communication with employee | Insufficient | ||

| Nieuwenhuijsen et al. [68] | Positive | Time to full RTW | |

| Promoting RTW | Insufficient | ||

| Nieuwenhuijsen et al. [68] | No effect | Time to full RTW | |

| Consulting with professionals | Insufficient | ||

| Nieuwenhuijsen et al. [68] | Negative | Time to full RTW | |

| Social support supervisor | 2+ | ||

| Vemer et al. [80] | Positive | Full RTW > 4 weeks | |

| Social support leader | |||

| Netterstrøm et al. [83] | Positive | RTW after 1 year (yes vs no) | |

| Coworker support | 2+ | ||

| Vemer et al. [80] | Positive | Full RTW > 4 weeks | |

| Netterstrøm et al. [83] | Positive | RTW after 1 year (yes vs no) | |

| Interactional justice with supervisor | Insufficient | ||

| Ekberg et al. [82] | Negative | RTW < 3 vs 3–12 months | |

| Contact OP in past 4 weeks | Insufficient | ||

| Brouwers et al. [71] | Negative | Full RTW (yes vs no) | |

| Personal factors | |||

| Older age | 8−, 4ne | ||

| Hees et al. [76] | No effect | Full RTW > 4 weeks | |

| Salkever et al. [66] | Negative | Time to RTW (claim duration) | |

| Engstrom and Janson [70] | Negative | RTW after SA > 28 days | |

| Dewa et al. [67] | Negative | RTW part-time or full-time | |

| Young and Russel [65] | Negative | RTW > 4 months | |

| Hoedeman et al. [73] | Negative | Time until complete RTW | |

| Nieuwenhuijsen et al. [69] | Negative | Time to full RTW | |

| Brouwer et al. [72] | No effect | Time to full RTW | |

| Vemer et al. [80] | Negative | Full RTW > 4 weeks | |

| Nielsen et al. [74] | No effect | Time to RTW | |

| Nielsen et al. [77] | No effect | Time to RTW (benefits stopped) | |

| Prang et al. [85] | Negative | Time to sustained RTW > 30 days | |

| Female gender | 1+, 3−, 6ne | Female gender | |

| Ekberg et al. [82] | No effect | RTW < 3 vs 3–12 months | |

| Engstrom and Janson [70] | Negative | RTW after SA > 28 days | |

| Dewa et al. [67] | No effect | RTW part-time or full-time | |

| Young and Russel [65] | Positive | RTW > 4 months | |

| Brouwer et al. [72] | No effect | Time to full RTW | |

| Vemer et al. [80] | Negative | Full RTW > 4 weeks | |

| Nielsen et al. [74] | No effect | Time to RTW | |

| Nielsen et al. [77] | No effect | Time to RTW (benefits stopped) | |

| Soegaard [79] | No effect | RTW rate | |

| Prang et al. [85] | Negative | Time to sustained RTW > 30 days | |

| Educational level high | 1+, 2−, 2ne | Educational level high | |

| Ekberg et al. [82] | Negative | RTW < 3 vs 3–12 months | |

| Hees et al. [76] | No effect | Full RTW > 4 weeks | |

| Nieuwenhuijsen et al. [69] | Negative | Time to full RTW | |

| Brouwer et al. [72] | Positive | Time to full RTW | |

| Nielsen et al. [77] | No effect | Time to RTW (benefits stopped) | |

| Low socio-economic position | Insufficient | ||

| Virtanen et al. [75] | Negative | RTW after SA ≥ 90 days | |

| Living with adult partner (no children) | Insufficient | ||

| Vemer et al. [80] | Negative | Full RTW > 4 weeks | |

| Co-morbidity | 2−, 2ne | ||

| Dewa et al. [67] | No effect | RTW part-time or full-time | |

| Hees et al. [76] | Negative | Full RTW > 4 weeks | |

| Engstrom and Janson [70] | Negative | RTW after SA > 28 days | |

| Nielsen et al. [77] | No effect | Time to RTW (benefits stopped) | |

| General health perception | 2+, 1ne | ||

| Hees et al. [76] | Positive | Full RTW > 4 weeks | |

| Sampere et al. [78] | No effect | Time to RTW | |

| Nielsen et al. [77] | Positive | Time to RTW (benefits stopped) | |

| Expectations of treatment | Insufficient | ||

| Ekberg et al. [82] | Positive | RTW < 3 vs 3–12 months | |

| Perceived relation between health and job | Insufficient | ||

| Sampere et al. [78] | Negative | Time to RTW | |

| Attributes cause of absenteeism to family problems | Insufficient | ||

| Brouwers et al. [71] | Negative | Full RTW (yes vs no) | |

| Personal work related factors | |||

| Work motivation | 1+, 1ne | ||

| Hees et al. [76] | Positive | Full RTW > 4 weeks | |

| Brouwer et al. [72] | No effect | Time to full RTW | |

| Bullying | 2− | ||

| Netterstrøm et al. [83] | Negative | RTW after 1 year (yes vs no) | |

| Prang et al. [85] | Negative | Time to sustained RTW > 30 days | |

| Self-efficacy | 2+, 3ne | ||

| Willingness to expend effort in completing a behavior | |||

| Brouwer et al. [72] | Positive | Time to full RTW | |

| Willingness to initiate behavior | |||

| Brouwer et al. [72] | No effect | Time to full RTW | |

| Persistence in the face of adversity | |||

| Brouwer et al. [72] | No effect | Time to full RTW | |

| General self-efficacy | |||

| Sampere et al. [78] | No effect | Time to RTW | |

| RTW self-efficacy | |||

| Nieuwenhuijsen et al. [81] | Positive | Time to full RTW | |

| Need for reduced demands at work | Insufficient | ||

| Ekberg et al. [82] | Negative | RTW < 3 vs 3–12 months | |

| Better workability score (WAI) | 2+, 1ne | ||

| Ekberg et al. [82] | Positive | RTW < 3 vs 3–12 months | |

| Sampere et al. [78] | No effect | Time to RTW | |

| Netterstrøm et al. [83] | Positive | RTW after 1 year (yes vs no) | |

| Expectations concerning sick leave duration or RTW | 4+, 1ne | ||

| Brouwers et al. [71] | Positive | Full RTW (yes vs no) | |

| Nieuwenhuijsen et al. [69] | Positive | Time to full RTW | |

| Sampere et al. [78] | Positive | Time to RTW | |

| Nielsen et al. [74] | Positive | Time to RTW | |

| Nieuwenhuijsen et al. [81] | No effect | Time to full RTW | |

| Job-turnover intentions | Insufficient | ||

| Ekberg et al. [82] | Negative | RTW < 3 vs 3–12 months | |

| White collar vs blue collar | Insufficient | ||

| Soegaard [79] | Positive | RTW rate | |

| Occupational category | 2ne | ||

| Engstrom and Janson [70] | No effect | RTW after SA > 28 days | |

| Nielsen et al. [74] | No effect | Time to RTW | |

| Holding a management function | Insufficient | ||

| Vemer et al. [80] | Positive | Full RTW > 4 weeks | |

+ positive related with RTW, − negative related with RTW, ne not related to RTW

Table 4.

Overview of prognostic factors of recurrent SA in workers with common mental disorders

| Factor | Result | Evidence | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disease related factors | |||

| No factors were studied | |||

| Body functions and structures | |||

| No factors were studied | |||

| Activities | |||

| No factors were studied | |||

| (Work) participation | |||

| Previous episode(s) of sickness absence | 2+ | ||

| Sado et al. [91] | Positive | Time to recurrent SA | |

| Koopmans et al. [88] | Positive | Recurrence of SA | |

| Environmental factors | |||

| Medication use | Insufficient | ||

| Arends et al. [90] | No effect | Recurrent SA at 12 months | |

| Environmental work related factors | |||

| Industry/sector | Insufficient | ||

| Koopmans et al. [88] | Positive | Recurrence of SA | |

| Company size > 100 | Insufficient | ||

| Arends et al. [90] | Positive | Recurrent SA at 12 months | |

| Supervisor support | Insufficient | ||

| Arends et al. [90] | No effect | Recurrent SA at 12 months | |

| Coworker support | Insufficient | ||

| Arends et al. [90] | No effect | Recurrent SA at 12 months | |

| Conflict with supervisor | Insufficient | ||

| Arends et al. [90] | Positive | Recurrent SA at 12 months | |

| Job demands | Insufficient | ||

| Endo et al. [92] | Positive | Recurrent SA | |

| Job control | Insufficient | ||

| Endo et al. [92] | No effect | Recurrent SA | |

| Type of social security contributions (general scheme vs self-employed) | Insufficient | ||

| Real et al. [64] | No effect | Recurrent SA | |

| Personal factors | |||

| Older age | 1+, 3−, 4ne | ||

| Koopmans et al. [86] | Negative ♀ No effect ♂ |

Recurrence of SA | |

| Koopmans et al. [88] | Negative | Recurrence of SA | |

| Roelen et al. [87] | No effect | Recurrent SA | |

| Sado et al. [91] | Negative | Time to recurrent SA | |

| Endo et al. [92] | No effect | Recurrent SA | |

| Real et al. [64] | No effect | Recurrent SA | |

| Norder et al. [93] | Positive | Recurrent SA episode | |

| Gender | 7ne | ||

| Sado et al. [91] | No effect | Time to recurrent SA | |

| Koopmans et al. [86] | No effect | Recurrence of SA | |

| Koopmans et al. [88] | No effect | Recurrence of SA | |

| Roelen et al. [87] | No effect | Recurrence of SA | |

| Norder et al. [93] | No effect | Recurrent SA episode | |

| Endo et al. [92] | No effect | Recurrent SA | |

| Real et al. [64] | No effect | Recurrent SA | |

| Low socio-economic position | 1+, 1ne | ||

| Roelen et al. [87] | No effect | Recurrence of SA | |

| Virtanen et al. [75] | Positive | Recurrence of SA ≥ 90 days | |

| Marital status unmarried | 1+, 3ne | ||

| Koopmans et al. [88] | Positive ♀ No effect ♂ |

Recurrence of SA | |

| Roelen et al. [87] | No effect | Recurrence of SA | |

| Norder et al. [93] | No effect | Recurrent SA episode | |

| Cohabiting | 2ne | ||

| Arends et al. [90] | No effect | Recurrent SA at 12 months | |

| Living alone | |||

| Endo et al. [92] | No effect | Recurrent SA | |

| Co-morbid conditions | 2+, 1− | ||

| Ervasti et al. [89] | Positive | Recurrence of SA | |

| Koopmans et al. [88] | Positive | Recurrence of SA | |

| Arends et al. [90] | Negative | Recurrent SA at 12 months | |

| Personal work related factors | |||

| Higher salary scale | 1−, 1ne | ||

| Koopmans et al. [88] | No effect | Recurrence of SA | |

| Roelen et al. [87] | Negative | Recurrence of SA | |

| Full-time vs part-time employed | 3ne | ||

| Koopmans et al. [88] | No effect | Recurrence of SA | |

| Roelen et al. [87] | No effect | Recurrence of SA | |

| Norder et al. [93] | No effect | Recurrent SA episode | |

| Being a shift worker (versus day worker) | Insufficient | ||

| Norder et al. [62] | No effect | Recurrent SA episode | |

| Working as a manager | Insufficient | ||

| Endo et al. [92] | No effect | Recurrent SA | |

| Shorter duration of employment (tenure) | 2−, 1ne | ||

| Koopmans et al. [88] | Negative ♀ No effect ♂ |

Recurrence of SA | |

| Roelen et al. [87] | Negative | Recurrence of SA | |

| Time for commute | Insufficient | ||

| Endo et al. [92] | No effect | Recurrent SA | |

| Job title | Insufficient | ||

| Endo et al. [92] | No effect | Recurrent SA | |

In Koopmans et al., Roelen et al., and Norder et al. recurrent was defined as SA > 28 days after RTW; in Real et al. recurrence was defined as within 180 days after RTW

+ positive related with recurrent SA, − negative related with recurrent SA, ne not related with recurrent SA

Sickness Absence

In total, 78 factors for SA in CMD were examined in 42 included articles [23–64]. Table 2 provides an overview of the detected prognostic factors for SA in workers with CMDs, categorized according to the domains of the ICF-framework. The direction of the effect of each factor on SA and the outcome is presented. Only multivariate results are presented. In the majority of the studies, SA was defined as an absence-spell (of certain length) during a certain time span (follow-up period). More detailed information on study objectives, study population, and association estimates with 95% confidence intervals is provided in Supplemental Table 1.

Predictors for SA were observed in all domains of the ICF-framework, except in the ‘activities’ domain. There is consistent evidence from three or more studies that previous episodes of CMD, higher symptom severity (depression, anxiety, burnout), a past history of absenteeism, co-morbidity, high job demands, low job control, high job strain, female gender, lower educational level, smoking behavior, and low perceived general health are predictors of SA in people with CMDs. In addition, there is consistent evidence from two studies that sleeping problems, mental distress, exhaustion, iso-strain (high strain combined with low support), and lower organizational justice are predictors of SA. Consistent evidence for ‘no effect’ was observed for agreeableness, openness, coworker support and effort-reward imbalance. The evidence on age and socio-economic position as predictors for RTW was inconsistent. Because several factors had been studied in only one study, the evidence was qualified as insufficient.

Most robust and modifiable factors, and therefore suitable to be used for interventions to prevent SA, are symptom severity (a positive relation between higher symptom severity and SA was reported in all 11 studies which focused on that factor), job demand and control, job strain, organizational justice, sleeping problems, smoking behavior, and perceived general health. Especially when high perceived job demands are combined with low control and when high strain jobs are combined with low support, there is a higher risk of SA [34, 63]. Higher perceptions of organizational justice were associated with 20–34% lower odds of SA due to CMDs [50]. In another study, organizational justice was only associated with SA for men [54].

Return to Work

In total, 53 predictive factors for RTW after SA in people with CMDs were examined in 21 included articles [65–85]. Table 3 provides an overview of the detected prognostic factors for RTW in workers with CMDs. In the majority of the studies, RTW was defined as time to (full) RTW. In Supplemental Table 1, a more detailed overview of the articles is provided.

In all domains of the ICF-framework predictors for RTW were observed, except in the ‘activities’ domain. There is consistent evidence from three or more studies that lower symptom severity, having no previous absenteeism, younger age, and positive expectations concerning sick-leave duration or RTW are predictors of (earlier) RTW in people with CMDs.

There is evidence from two studies that support from supervisor and coworkers, presence of co-morbidity, bullying, (work)self-efficacy beliefs, better general health perception, and higher Work Ability Index score are predictors of (earlier) RTW.

The evidence on gender and educational level being predictors for RTW was inconsistent, and there is evidence from two studies that occupational category is not a predictor for RTW. For many factors the evidence is insufficient because it was identified in only one study, e.g. decision latitude, variety in work, and job demands. Salkever et al. were the only authors who studied benefit plan features [66], and they found that employee mental health benefits and the availability of mental health treatment resources may influence RTW.

Recurrent Sickness Absence

In total, 24 factors for recurrent SA in CMD were investigated in 11 included articles [62, 64, 75, 86–93]. Table 4 provides an overview of all 24 factors, categorized in accordance with the framework of the ICF. In the ICF-domains ‘disease related factors’, ‘body functions and structures’, and ‘activities’ no factors were studied.

There is consistent evidence from two studies that having previous episode(s) of sickness absence and shorter duration of employment (tenure) is a predictor of recurrent SA in people with CMDs. There is consistent evidence from seven studies that gender is not a predictor for recurrent SA. In addition, there is evidence from two or more studies that marital status, cohabiting, and full-time work (vs part-time work) are not predictors of recurrent SA. There is inconsistent evidence for age and co-morbidity being predictors for recurrent SA.

Sub-analysis of the Relation Between CMD Diagnostic Groups and Work Outcomes

In 15 articles in which more than one CMD diagnostic group has been studied, the relation between diagnosis and work outcome was reported (see Supplemental Table 2). Overall, depression appears to be the strongest predictor for worse work outcomes. However, in the three studies that reported about somatoform disorders (somatization), it was concluded that these affected work outcomes even more than depression [57, 73, 79]. In total, 6 studies on SA and five studies on RTW reported different predictive values across diagnoses, and four studies found no differences in RTW or recurrent SA between the different diagnoses.

Discussion

In this scoping review we provided an overview of predictive factors for (recurrent) SA and RTW among workers with CMDs. Our results indicate that a variety of personal-, work-, and illness related determinants for SA and RTW have been identified so far by research.

Sickness Absence

In the earlier literature on work outcomes of people with a CMD, the focus of study was mainly on the prognostic value of the condition itself. Since we know that people with a CMD have higher odds to have problems with (sustainable) work participation, but the condition in itself provides an inadequate explanation, the research focus has become more on personal-, and environmental (e.g. work) related factors. The most relevant determinants for SA identified in our review, in terms of association and modifiability, are symptom severity, job demands and control, job strain, organizational (in)justice, sleeping problems, smoking behavior, and perceived general health. Individuals with a CMD with earlier episodes and a past history of absenteeism, who encounter high job demands, low job control, low support at work, sleeping problems, and low perceived health, are at high risk of SA.

There was consistent evidence that earlier episodes of CMD and high symptom severity are predictors for SA. From literature it is known that serious mental disorders are substantially underdiagnosed and undertreated among disability claimants [79, 94, 95], which is associated with inadequate availability and accessibility of care. Early recognition and diagnose of CMDs is very important, especially because interventions might prevent impairment of conditions and work disability. In the end, staying at work might be a powerful determinant for (mental) health of workers with a CMD [96]. However, symptom reduction due to psychosocial interventions is important, but is not a guarantee for reduction of sick-leave [97].

Although it is clear that having a CMD is related with SA, the causality of this relation is less obvious. Sanderson et al. reported that having a CMD was a consequence (and not a risk factor) of SA, limitations in work activities or unfavorable work environment [23]. In other studies, many workers believed that the most important causes of their CMDs were work related, and they reported factors such as work stress, leadership, reduced work participation, job dissatisfaction, work conflict, social work environment, job insecurity and change, workplace bullying, disrupted communication with supervisor, and physical strain [98, 99]. Therefore, preventive interventions for SA “should aim at decreasing psychosocial risk factors for the onset of CMDs at the workplace” [100].

There is consistent evidence that higher perceived job demands combined with low job control is related with SA of workers with CMD [31, 33, 34, 37, 43, 51, 55, 63]. A job with high decision latitude can largely neutralize the risk of high job demands. Therefore, interventions to prevent SA of workers with a CMD should involve the workplace [100]. Improving the work environment might not only prevent SA, it even may prevent the development of a CMD [98, 99].

Earlier episodes of CMD and having a past history of CMD-related SA is a predictor for future SA [24, 28, 38, 60], and therefore in the supervision of absent employees with CMDs more attention should be paid to previous episodes of mental illness. These workers at risk for future SA might be supported to stay at work, although account should be taken of stigmatization of workers.

Poor support or lack of support from the superior (positive feedback and appreciation of achievements) was observed as determinant of SA for workers with a CMD, it doubled the risk of absence for both genders [36]. The authors conclude that improving working conditions, such as social support, “may be an important step toward reducing the burden of SA due to mental conditions”.

Return to Work

The key determinants for RTW in workers with a CMD currently reported in the literature are symptom severity, duration of previous absenteeism, age, general health perception, bullying, social support from coworkers and supervisor, and positive expectations concerning sick-leave duration or RTW. For most environmental work related factors insufficient evidence was observed (Table 3).

Support from supervisor was variably associated with better work outcomes. Nieuwenhuijsen et al. concluded that supervisors should communicate more frequently with sick-listed employees with CMDs, and hold follow-up meetings more often, as this is associated with a faster RTW in those employees [68]. They advise supervisors to keep in touch with employees who are sick listed at least once every 2 weeks. However, promoting RTW by the supervisor had no effect, and consulting with professionals even had a negative effect on RTW. The explanation of the authors was that “supervisors may consult other professionals sooner if they foresee problems in the RTW-process” [68]. Patients with more social support from coworker or supervisor had a shorter time to RTW [80]. Other studies report no associations between supervisor support and SA [34, 55]. In a recent Swedish study, worse perceived interactional justice with the supervisor was associated with early RTW [82].

We found consistent evidence that the expectations concerning sick-leave duration or RTW are predictive for time to RTW, and may have a significant impact on the outcomes of interventions for RTW. Knowledge of workers’ expectations in the early phase of SA may contribute to shortening the time to RTW, and questioning workers about their expectations can serve as screening the risk of long-time SA [78]. Although expectations about sick-leave duration and RTW have predictive value, an explanation of these expectations should be examined in consultations with the individual employee. Workers’ expectations can be considered as a ‘canary in the coal mine’, and should give rise to a more detailed analysis of both individual- and work-related factors. Workers’ expectations are presumably based on the social context, the available social support both at home and at work, opportunities to realize work accommodations or to return to work gradually, and on the severity of illness. Nieuwenhuijsen et al. reported fatigue, suffering from depression, and workpace and workload as determinants for RTW perceptions [81]. Løvvik et al. reported a strong relationship between illness perceptions and RTW-expectations among people with CMD [101]. Addressing RTW-expectations in occupational healthcare services or vocational rehabilitation might be beneficial in early stages or even prior to a sick-leave episode [102]. Expectations for RTW [103] and self-efficacy [104] can be measured with a questionnaire, although the former needs further validation in a CMD population.

Recurrent Sickness Absence

About 19–37% of employees with SA due to CMDs at baseline had recurrent episodes after RTW during two year follow-up [86, 92]. It is recommended to follow workers who just returned to work for a longer period and not take their return for granted, because many workers with a CMD have recurrences of SA. The oversight of determinants for recurrent SA does not provide much consistent evidence in favor of certain prognostic factors. This is mainly caused by the fact that most factors were studied only once. The number of previous episode(s) of SA [88, 91] and a shorter tenure [87, 88] were consistently related to recurrent SA. Interventions to prevent recurrence of SA in people with CMDs in order to sustain employees at work, may aim at detection of workers with previous episode(s) of SA and workers with a shorter employment relationship. Furthermore, it sounds reasonable that the predictors for SA may also apply for recurrent SA, and that these could be used too. In one study, it was observed that conflict with supervisor was a risk factor [90]. Obviously, not only the absence of social support from supervisor, but also the presence of negative relationships may affect SA.

Strengths and Limitations

This scoping review provides a clear overview of the existing empirical evidence about the prognostic factors of SA and RTW among workers with a CMD. A total of 71 articles were identified, which is a far greater range than previously known. The classification of these factors in ICF-domains across work outcomes facilitates retrieval of information and comparison with other research. The data was collected in a systematic manner and the probability of missing important literature is quite low. A strength of this scoping review was that we differentiated between three chronologically occurring work outcomes (SA, RTW, and recurrent SA), and that we presented all applied outcomes.

One general limitation of a scoping review is that no thorough quality assessment of retrieved studies is performed. In order to overcome this limitation, we only presented results established through multivariate analyses, which controlled for possible confounders [105], although the kind of treatment(s) that participants followed was controlled for in only a few of the included studies.

The time to follow-up in the vast majority of studies was sufficient (1 or more years). Although a few studies had a cross-sectional design, in these cases a retrospective data collection was performed on previous treatment, SA, or potential confounders. Another limitation of this scoping review was that CMDs were studied as one group where no distinction was made between different diagnostic groups, such as anxiety disorders and depressive disorders, which makes interpretation less specific. Moreover, in a few studies the exact amount of people with a CMD was unclear. Frequently, more articles were published based on the same cohort study. In these cases, it was not always clear to what extend the research data of these articles overlapped, which occasionally might have led to double reporting.

The majority of studies identified in the review were performed in the Netherlands or the Scandinavian countries. In Denmark, the first period of disability is paid by the local government, the municipalities. In the Netherlands and in Sweden, the employer bears responsibility for sustainable work participation and RTW of employees. In case of continued sickness or disability, Dutch workers get 100% pre-injury earnings compensated by the employer during the first year. This could have the effect that workers are not motivated to get back to work quickly. However, because the employer has incentives and legal obligations to support the absent worker, the possibilities to adapt the work to the needs of workers are utilized when necessary. Thus, in the Netherlands, Denmark and Sweden the employer or the government has an interest in preventing SA and promoting RTW, and initiates interventions to succeed. In this context, it is understandable that a boom of research on SA and RTW was initiated in these countries. However, the question is to what extent these results can be generalized to other countries. A compensation policy that provides for economic support in case of sickness or disability does not exist in all countries. Thereby, the propensity to take sick-leave or to return to work will differ across jurisdictions, even across Australian state and territory workers’ compensation systems [106]. In the USA, social security disability insurance taxes may discourage individual firms from investing in RTW. Likewise, the jurisdictions for CMDs as accepted cause of SA differ across countries. Therefore, it is not easy to draw general conclusions about predictive factors for SA or RTW, because a promoting factor in one jurisdiction might be a limiting factor in another.

Gaps in the Current Knowledge

Factors from the activities domain of the ICF framework are under investigated. Probably, researchers think that activity level is unimportant or not relevant in people with a CMD because they have no activity limitations. On the other hand, inactivity is an important symptom in CMDs and is not conducive to recovery [107]. From this point of view, the relation of (in)activity should be analyzed more in future research. In our review we identified two articles which studied the relation between physical activity and SA, of which one concluded that physical activity was related [40] and the other found no association [63]. There is currently not enough evidence to draw conclusions about activities-related factors as determinant for SA or RTW.

Salkever et al. are the only authors who focused their study on benefit plan features, such as availability of mental health benefits and services, employers’ disability management practices, and long-term disability policy provisions provided by the employer [66]. It was concluded that integration of disability management with related services, and providing job accommodations was related to a higher probability of RTW. Provision of more generous benefits in terms of lower deductible, shorter preexisting condition exclusion period, and not having a carve out encouraged earlier RTW. Employees having a broader criterion for continuing disability had a lower probability of RTW. Because the effect of benefit plan features was only studied by Salkever et al., the evidence was classified as insufficient. Notwithstanding, the results are interesting. It was observed that benefit plan features may play a role in the RTW trajectories of workers with CMDs. This study demonstrates that the benefit plan features, which may differ across companies, individuals, and even countries, could possibly affect SA and RTW. To what extent these results are also valid in other benefit systems in countries other than the USA, where jurisdictions and legislation are different, is still unclear.

Organizational justice was observed as determinant for SA in people with a CMD [50, 54]. In a largely representative sample of employees in the Netherlands, it was found that both distributive and procedural justice contributed to lower depressive symptoms, and distributive justice contributed to lower SA [108]. Perceived injustice in general might be an important determinant, which is already studied among people with musculoskeletal problems [109]. Emerging evidence suggests that perceived injustice might be a relevant factor for many people with chronic non-specific back pain and is considered as a determinant for work disability [109, 110]. The feelings of injustice may be directed against the employer, the insurer, co-workers, healthcare workers, occupational physician, or the person who performed a functional capacity evaluation. Because perceived injustice is likely related to depressive feelings [108, 111], it could be addressed in future research and practice of CMDs.

In a systematic review exploring illness perception in mental health utilizing the self-regulation model, it was concluded that the dimensions of the self-regulation model were largely supported, and applicable to mental illness [112]. We did not find sufficient evidence in our review about illness perceptions as predictor for work outcomes among people with CMDs. Illness perceptions are derived from the self-regulatory model of health behavior [113], which provides a framework for understanding the processes by which an individual’s own implicit, common-sense beliefs about illness are associated with behavioral responses employed to manage outcomes. Five dimensions of illness perceptions are distinguished: identity (the label of the illness and the symptoms the patient views as being part of the disease); cause (personal ideas about etiology); time-line (how long the patient believes the illness will last); consequences (expected effects and outcome of the illness); and cure/control (how one recovers from, or controls, the illness) [113]. Løvvik et al. found that illness perceptions predicted benefit recipiency in people with CMDs in the unadjusted model, but not in the fully adjusted model [114]. Results from a recent systematic review suggest that illness perceptions may play an important role in mediating between illness and work outcomes [115]. Although expectations about recovery as earlier described in our review is part of illness perceptions, there are more interesting aspects of illness perceptions mentioned above which have not been studied yet in CMDs.

To what extent are the prognostic factors in the present study congruent to the opportunities and obstacles mentioned to be important for work outcomes by the workers with CMD themselves? In a meta-analysis of qualitative research on RTW among employees with CMDs, a number of obstacles and facilitators were identified [116]. Perfectionist character made it difficult for employees to slow down their work pace and to accept reduced work capacity. The possibility to gradually RTW (increase working hours, responsibilities, and workload), the realization of work accommodations, and social support from both supervisors and co-workers were reported as important facilitators by employees. Attitudes of employers and co-workers towards sick-leave and development of CMD affected the motivation to return to work significantly. Perceived injustice may occur when understanding of CMD symptoms is lacking, and when work accommodations are not acknowledged and respected [116]. The right timing for RTW, in other words the readiness for RTW, was indicated as an important factor. In a qualitative study, the RTW process of workers on sick leave due to CMD was studied [117]. The main perceived barriers experienced by the workers were the inability to set limits, decreased capacity, recognition of exhaustion, lack of support, and to control cognitions and behavior such as perfectionism. Indicated solutions were learning a new way of dealing with work demands, and treating mental or physical symptoms. Furthermore, an intention-behavior gap was observed between the solutions and intentions to full RTW. According to the authors, having a positive attitude and increasing self-confidence by extending the workload carefully towards a full RTW are prerequisites for the intent to proceed.

In a Delphi study, group consensus was sought among scientists and physicians with expertise in assessing work disability on factors predicting recurrent SA due to depression [118]. Workers at risk of recurrent SA due to depression may be identified by stressful life and work events, number and duration of earlier depressive episodes, psychological work demands, decision latitude, and commitment to work.

Recommendations for Future Research

In this scoping review we provided an oversight of prognostic factors for (recurrent) SA and RTW among people with a CMD. Further research is clearly required; there is a need for a systematic review or meta-analysis, in which the strength of prognostic values is investigated. The following factors are regarded as important by workers with CMDs and should be considered as subject for future primary research, because original primary studies are lacking: perfectionism, illness perceptions, acceptance of the illness and decreased work capacity, the possibility for gradual RTW and work accommodations, and perceived injustice. There is a need to develop more interventions to prevent SA and to improve RTW for workers with a CMD, and also to carry on studies that investigate its effectiveness. When future interventions are designed based on the known prognostic factors for SA and RTW, their effectiveness can potentially be improved.

More research on predictors for RTW in people with CMDs is needed in the ICF-domains ‘body functions and structures’, ‘activities’, and ‘environmental factors’. Concerning SA, RTW and recurrent SA, more research is needed on ‘environmental (work related) factors’, because the evidence in this domain was mostly insufficient as it came from only one study. Lastly, more research is needed on recurrent SA, because prognostic factors in the ICF-domains ‘disease related factors’, ‘body functions and structures’, and ‘activities’ were lacking.

Conclusions

The amount of research on determinants for SA and RTW in workers with CMD has increased dramatically in recent years. It is noticed that the majority of studies has been carried out in the Scandinavian countries and the Netherlands. A variety of personal-, work-, and illness-related determinants have been observed across the ICF domains. Although illness related factors are playing an important role in SA and RTW of workers with CMDs, health interventions alone are insufficient to prevent SA and to improve RTW. Symptom reduction due to psychosocial interventions does not automatically result in a reduction of sick-leave. Work-related interventions are essential and should always be part of a prevention or reintegration program. In care for people with CMDs, the management of expectations should be taken very seriously, because expectations often reveal issues in environmental and personal domains that bother the individual worker. Future interventions for improvement of work outcomes should be built with a variety of prognostic factors from different domains.

There is a lack of studies in the ICF domains ‘activities’ and ‘environmental factors’. In addition, there are some research gaps identified in this scoping review that need further attention in primary and secondary studies.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- 1.Ahola K, Virtanen M, Honkonen T, Isometsa E, Aromaa A, Lonnqvist J. Common mental disorders and subsequent work disability: a population-based health 2000 study. J Affect Disord. 2011;134(1–3):365–372. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wittchen HU, Jacobi F, Rehm J, Gustavsson A, Svensson M, Jonsson B, et al. The size and burden of mental disorders and other disorders of the brain in Europe 2010. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;21(9):655–679. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2011.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knudsen AK, Harvey SB, Mykletun A, Overland S. Common mental disorders and long-term sickness absence in a general working population: the Hordaland Health Study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2013;127(4):287–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2012.01902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 Collaborators Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2015;386(9995):743–800. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60692-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steel Z, Marnane C, Iranpour C, Chey T, Jackson JW, Patel V, et al. The global prevalence of common mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis 1980–2013. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(2):476–493. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]