Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

Hypomagnesaemia (blood Mg2+ <0.7 mmol/l) is a common phenomenon in individuals with type 2 diabetes. However, it remains unknown how a low blood Mg2+ concentration affects lipid and energy metabolism. Therefore, the importance of Mg2+ in obesity and type 2 diabetes has been largely neglected to date. This study aims to determine the effects of hypomagnesaemia on energy homeostasis and lipid metabolism.

Methods

Mice (n = 12/group) were fed either a low-fat diet (LFD) or a high-fat diet (HFD) (10% or 60% of total energy) in combination with a normal- or low-Mg2+ content (0.21% or 0.03% wt/wt) for 17 weeks. Metabolic cages were used to investigate food intake, energy expenditure and respiration. Blood and tissues were taken to study metabolic parameters and mRNA expression profiles, respectively.

Results

We show that low dietary Mg2+ intake ameliorates HFD-induced obesity in mice (47.00 ± 1.53 g vs 38.62 ± 1.51 g in mice given a normal Mg2+-HFD and low Mg2+-HFD, respectively, p < 0.05). Consequently, fasting serum glucose levels decreased and insulin sensitivity improved in low Mg2+-HFD-fed mice. Moreover, HFD-induced liver steatosis was absent in the low Mg2+ group. In hypomagnesaemic HFD-fed mice, mRNA expression of key lipolysis genes was increased in epididymal white adipose tissue (eWAT), corresponding to reduced lipid storage and high blood lipid levels. Low Mg2+-HFD-fed mice had increased brown adipose tissue (BAT) Ucp1 mRNA expression and a higher body temperature. No difference was observed in energy expenditure between the two HFD groups.

Conclusions/interpretation

Mg2+-deficiency abrogates HFD-induced obesity in mice through enhanced eWAT lipolysis and BAT activity.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00125-018-4680-5) contains peer-reviewed but unedited supplementary material, which is available to authorised users.

Keywords: β-Adrenergic receptor, Brown adipose tissue, Energy homeostasis, Hypomagnesaemia, Lipid metabolism, Lipolysis, Magnesium, Obesity, White adipose tissue

Introduction

Hypomagnesaemia (blood Mg2+ concentration <0.7 mmol/l) affects approximately 30% of individuals with type 2 diabetes [1, 2]. Hypomagnesaemia is an important risk factor for the development and progression of type 2 diabetes [3–5]. Low dietary Mg2+ intake and reduced serum Mg2+ concentrations have also been associated with obesity, although with conflicting results [1, 6–8]. Moreover, reduced blood Mg2+ levels have been correlated with elevated glucose and triacylglycerol concentrations in individuals with type 2 diabetes, suggesting that hypomagnesaemia is associated with insulin resistance and dyslipidaemia [1].

Mg2+ fulfils many roles including cell growth, membrane stability, enzyme activity and energy metabolism [9]. It is a cofactor for numerous enzymes, primarily because it stabilises ATP and facilitates phosphate transfer reactions [10, 11]. Mg2+ is essential for glycolysis and the citric acid cycle [12, 13]. Because Mg2+ is critical for insulin receptor tyrosine kinase activity, hypomagnesaemia has also been implicated in insulin resistance [14–16]. Recently, hypomagnesaemia in mice was shown to contribute to enhanced catabolism, but no in-depth metabolic phenotype analysis was performed [17].

In type 2 diabetes, restoring serum Mg2+ values by oral Mg2+ supplementation improves insulin sensitivity, decreases fasting glucose levels [18] and corrects the lipid profile [19–21]. Although Mg2+ is essential for key enzymes in lipid metabolism, including hepatic lipase and lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase [22, 23], the effects of chronic Mg2+ deficiency on adipocyte function and lipid metabolism remain largely unknown.

In this study, we explored the role of Mg2+ in energy homeostasis, insulin sensitivity and lipid metabolism, by feeding mice a low-fat diet (LFD) or a high-fat diet (HFD) combined with low or normal Mg2+ for 17 weeks. The resulting metabolic effects were extensively characterised. Data were confirmed by an independent replication experiment.

Methods

Seventeen-week mouse study: Radboud university medical center

This study was approved by the animal ethics board of the Radboud University Nijmegen (RU DEC 2015-0073) and the Dutch Central Commission for Animal Experiments (CCD, AVD103002015239). Forty-eight male C57BL6/J mice (Charles River Laboratories, Sulzfeld, Germany), aged 9–10 weeks, were randomly allocated to four experimental groups of n = 12 mice. Experimental diets consisted of 10% or 60% energy from palm oil plus 0.03% or 0.21% wt/wt magnesium oxide. Researchers and animal caretakers were blinded for Mg2+ content. On days −1, 84 and 112, mice were housed individually in metabolic cages for 24 h. Blood was collected via cheek puncture at days −1, 28, 56 and 84. At weeks 14 and 15, ITT and GTT, respectively, were performed. After 17 weeks on the diets, mice were anaesthetised by 4% vol./vol. isoflurane and exsanguinated via orbital sinus bleeding. See electronic supplementary material (ESM) for full methods.

Intraperitoneal insulin and glucose tolerance tests

After 14 weeks on the diets, mice underwent an intraperitoneal ITT. After 6 h of fasting, from 08:00 to 14:00, mice were injected with 0.75 U/kg body weight of human insulin (Novorapid, Novo Nordisk, Bagsværd, Denmark). Blood glucose levels were measured at 0, 20, 40, 60, 90 and 120 min. After 15 weeks on the diets, mice underwent an IPGTT. After an overnight fast, from 18:00 to 09:00, mice were injected with 2 g/kg body weight of d-glucose (Invitrogen, Bleiswijk, the Netherlands). Blood glucose was measured at 0, 15, 30, 60 and 120 min. See ESM for full methods.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK), subjected to DNase (Promega, Fitchburg, WI, USA) treatment and measured using the Nanodrop 2000c spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). RNA was reverse transcribed using Moloney murine leukaemia virus (M-MLV) reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Bleiswijk, the Netherlands). Gene expression levels were quantified by SYBR-Green (Bio-Rad, Veenendaal, the Netherlands) on a CFX96 real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad) and normalised for Gapdh. Primer sequences for Acadl, Adrb3, Atgl (also known as Pnpla2), Cact, Cd36, Cpt1-l (also known as Cpt1a), Cpt1-m (also known as Cpt1b), Cpt2, Fbp1, G6pase (also known as G6pc), Gapdh, Glut1 (also known as Slc2a1), Glut2 (also known as Slc2a2), Glut4 (also known as Slc2a4), Gs, Gyk, Hmgcs1, Hsl (also known as Lipe), Mgll, Pepck1, Pklr, Ppar-α (also known as Ppara), Ppar-γ (also known as Pparg), Srebp1 (also known as Srebf1) and Ucp1 are provided in ESM Table 1.

Histology

Epididymal fat and liver tissues were fixed in 10% vol./vol. neutral-buffered formalin (KLINIPATH, Duiven, the Netherlands) in PBS. Samples were dehydrated through alcohol, embedded in paraffin and cut into 4 μm sections. Sections were stained with H&E using standard procedures. The average cell size of 100–300 cells per mouse was determined manually using ImageJ software (v1.48, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA, RRID:SCR_003070). Liver samples were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, cut into 10 μm sections, stained with Oil Red O (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and counterstained with haematoxylin.

RNA sequencing

Five randomly selected samples of each group were analysed, with no technical replicates, by RNA sequencing. Quality control and RNA sequencing were performed by the Beijing Genomics Institute (BGI), Hong Kong, China. Per sample, 13 million reads were sequenced using the Hiseq 4000 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) using a 50 bp single-end module. Clean reads were mapped to Mus musculus transcriptome (GRCm38/mm10) using the HISAT/Bowtie2 tool (RRID:SCR_005476) [24, 25]. RSEM software v1.2.31 (RRID:SCR_013027) was used to quantify gene expression levels (fragments per kilobase million [FPKM] values) [26]. FPKM values were log2 transformed and further analysed in R (www.r-project.org, v3.4.1., RRID:SCR_001905). Heatmaps for individual GO terms were created using the ggplot2 library (r-project) [27]. See ESM for full method details.

Analytical procedures

Serum Mg2+ was determined using a spectrophotometric assay at 600 nm (Roche/Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Liver samples were weighed and lysed in lysis buffer (10% wt/vol.) containing 50 mmol/l Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 1 mmol/l EGTA, 1 mmol/l EDTA, 1% vol./vol. Triton X-100, 10 mmol/l glycerophosphate, 1 mmol/l sodium orthovanadate, 50 mmol/l sodium fluoride, 10 mmol/l sodium pyrophosphate and 150 mmol/l sodium chloride. Triacylglycerol concentrations in serum and liver lysate were assayed using an enzymatic kit (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN, USA), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Serum NEFA (NEFA-C kit, WAKO Diagnostics, Delfzijl, the Netherlands), cholesterol (Human Diagnostics, Wiesbaden, Germany), glucose (Instruchemie, Delfzijl, the Netherlands), leptin (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) and adiponectin (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) concentrations were determined according to manufacturers’ protocols.

3-Methoxytyramine and normetanephrine were analysed by a 6490 LC-MS/MS (Agilent Technologies, Amstelveen, the Netherlands) after solid phase extraction (SPE) Oasis WCX μElution sample cleanup (Waters, Etten-Leur, the Netherlands). A calibration curve was used with 3-methoxytyramine-HCl and normetanephrine-HCl (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) as calibrators. 3-Methoxytyramine-d4-HCl and normetanephrine-d3-HCl (Medical Isotopes, Pelham, NH, USA) were used as internal standards. An ethylene bridged hybrid (BEH) Amide 1.7 μm 100A, 2.1 × 100 mm column (Waters) was used as an analytical column.

Nine-week replication mouse study: MRC Harwell Institute

All experimental procedures were conducted in compliance with the UK Animals Scientific Procedures Act (1986) and University of Oxford ethical guidelines. Thirty-nine male C57BL6/J mice (Medical Research Council [MRC], Harwell, UK) were randomly allocated to four groups of n = 10 mice (n = 9 in the low Mg2+[LowMg]-LFD group). At 8 weeks old, mice were put on experimental diets identical to the Radboud university medical center experiment for 9 weeks. At day 14, mice were housed individually in metabolic cages (Tecniplast, Buguggiate, Italy). Blood was collected via tail bleed at days −1 and 14. Respiration metabolic cages (TSE PhenoMaster Cages, Bad Homburg, Germany) were used at days 28 and 56 and body temperatures were measured by rectal probe (ATP-instrumentation, Ashby, UK). Data were averaged per hour and plotted from 18:30 to 09:30 h. See ESM Methods for full details.

Lipolysis in 3 T3-L1 adipocytes

Differentiated 3 T3-L1 cells (mycoplasma-free, ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) were incubated for 20 h in DMEM, containing 0 or 1 mmol/l MgCl2. Aliquots of 50 μl medium were taken hourly and heated for 8 min at 65°C. The concentration of NEFA was assessed using the WAKO NEFA-C kit (Instruchemie, Delfzijl, the Netherlands). See ESM Methods for full details.

Statistics

For the animal experiments, a two-way ANOVA was used to look for a significant interaction effect between the two main variables (dietary fat and Mg2+ content). If there was none, significant differences between the groups were assessed using a two-way ANOVA approach with a Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. If the two-way ANOVA demonstrated a significant interaction effect between the two main variables, an unpaired multiple t test approach using the Holm–Sidak method for multiple comparisons was used. Statistical significance was determined using Graphpad Prism v7 (La Jolla, CA, USA, RRID: SCR_002798). For the lipolysis assays, an unpaired Student’s t test was used.

Differences with a p value of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Results are presented as mean ± SEM.

Results

Low dietary Mg2+ intake reduces diet-induced obesity in mice

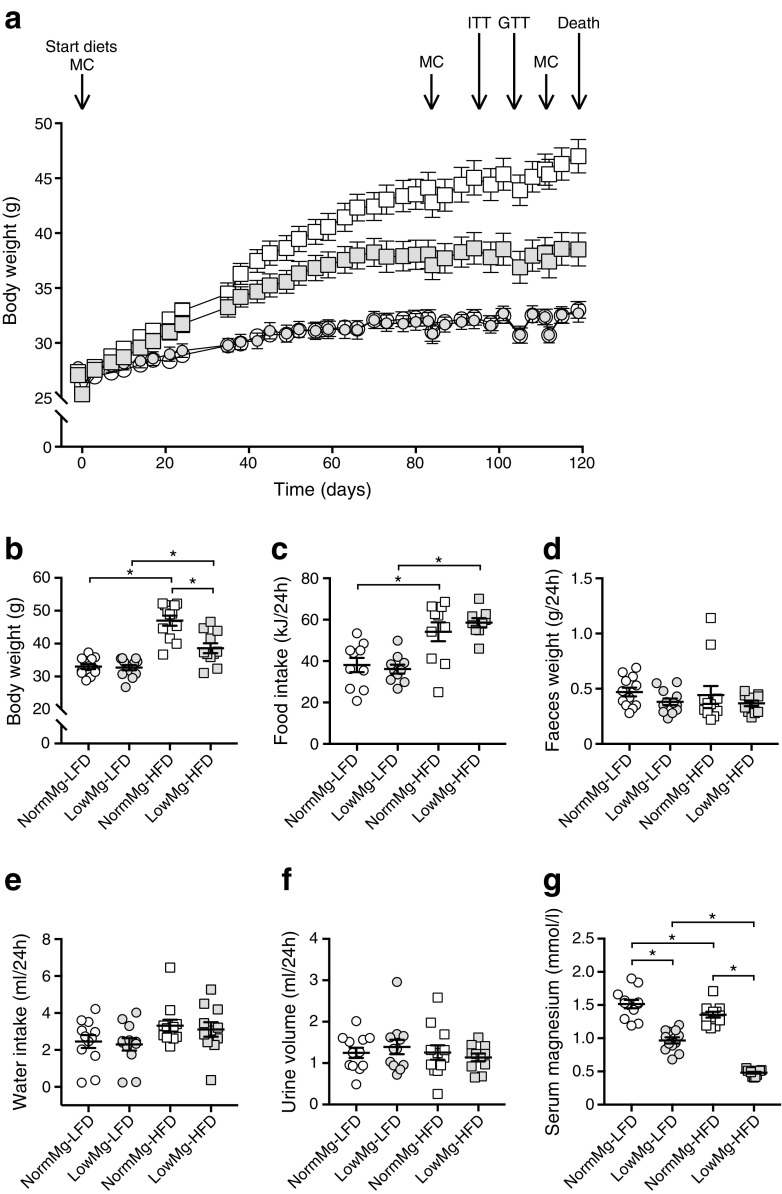

The mice were fed an LFD or HFD containing either a low (0.03% wt/wt) or normal (0.21% wt/wt) Mg2+ concentration for 17 weeks (Fig. 1a). There was no difference in body weight between low and normal Mg2+ groups on the LFD, but mice on the LowMg-HFD gained significantly less weight than those on the normal Mg2+(NormMg)-HFD (47.00 ± 1.53 g vs 38.62 ± 1.51 g in mice given a NormMg-HFD and LowMg-HFD, respectively, p < 0.05, Fig. 1a,b). The lower body weight of the LowMg-HFD group could not be explained by differences in dietary intake, as shown by similar food intake and faeces production between the two HFD groups (Fig. 1c,d). There was also no difference in water intake or urinary volume between the HFD groups (Fig. 1e,f). Hypomagnesaemia was detected in both the LowMg groups, but was significantly more pronounced in mice that were concomitantly fed an HFD (Fig. 1g).

Fig. 1.

Low dietary Mg2+ intake reduces diet-induced obesity in mice. Adult mice (n = 12 mice per group, n = 11 mice for the LowMg-HFD group) were fed a diet with either an LFD or an HFD, combined with a normal or low Mg2+ concentration, for 17 weeks. (a) Body weight, determined twice weekly. Arrows indicate experimental interventions: metabolic cage (MC), ITT and GTT. (b) The body weight of mice at week 17 (the end of the experiment). (c) Food intake, (d) total faeces weight, (e) water intake (two-way ANOVA for dietary fat effect p < 0.05) and (f) urine production determined over a period of 24 h, using metabolic cages, at week 16. (g) Serum Mg2+ levels at death. NormMg-LFD (white circles), LowMg-LFD (grey circles), NormMg-HFD (white squares), LowMg-HFD (grey squares). Data are mean ± SEM. Depending on the absence or presence of a significant interaction effect between dietary fat and Mg2+ content, either a two-way ANOVA (Tukey’s multiple comparison test) or an unpaired multiple t test (Holm–Sidak multiple comparison test) approach, respectively, was used to determine statistical significance. *p < 0.05 for the comparisons shown

Reduced diet-induced obesity in Mg2+-deficient mice is accompanied by improved insulin sensitivity

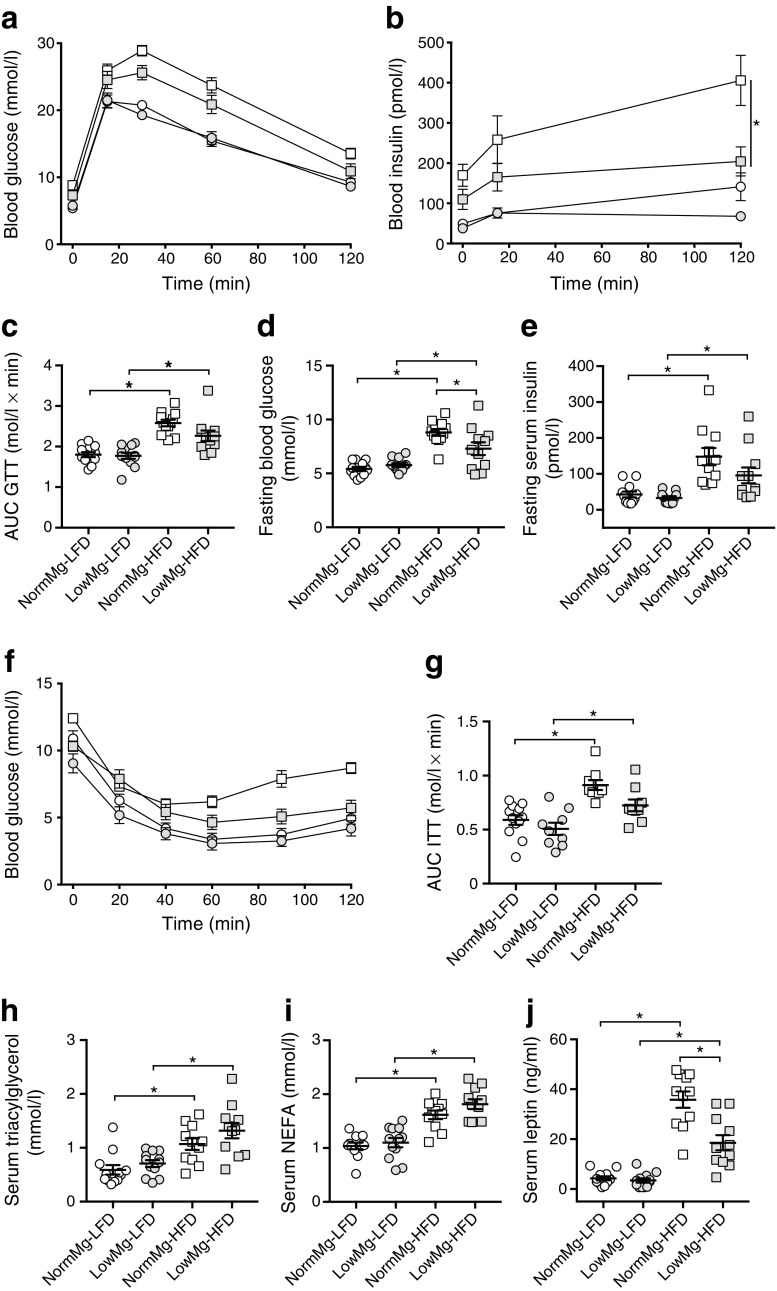

To explore glucose metabolism in more detail, beta cell function and insulin sensitivity were determined by IPGTT and IPITT. In the IPGTT (a measure for beta cell dysfunction and insulin resistance), glucose clearance was reduced in both HFD groups (Fig. 2a). Glucose clearance was not significantly different between NormMg-HFD-fed mice and LowMg-HFD-fed mice (2.58 ± 0.08 vs 2.26 ± 0.13 mol/l × min in NormMg-HFD- and LowMg-HFD-fed mice, respectively, p = 0.07, Fig. 2c). LowMg-HFD-fed mice required significantly less insulin than NormMg-HFD-fed mice to clear the glucose, consistent with LowMg-HFD-fed mice being more insulin sensitive (Fig. 2b). Fasting blood glucose and insulin concentrations were significantly increased in the HFD-fed mice, in accordance with the increased body weight (Fig. 2d,e). Compared with the NormMg-HFD-fed mice, fasting blood glucose was lower in the LowMg-HFD-fed mice (Fig. 2d). The effect of dietary Mg2+ on fasting insulin was not statistically significant (Fig. 2e, two-way ANOVA for dietary Mg2+ effect, p = 0.07).

Fig. 2.

Reduced diet-induced obesity in Mg2+-deficient mice is accompanied by high triacylglycerol levels and improved insulin sensitivity. (a) Glucose clearance determined by IPGTT at week 15. (b) Serum insulin measured at 0, 15 and 120 mins of the GTT. (c) AUC determined between 0 and 120 min. (d) Fasting blood glucose and (e) serum insulin measured during the GTT. (f) Blood glucose measured during an IPITT at week 14 (n = 9 mice per group, n = 12 for the NormMg-LFD. (g) AUC determined between 0 and 120 min (two-way ANOVA for dietary Mg2+ effect, p < 0.05). Non-fasted serum (h) triacylglycerol, (i) NEFA and (j) leptin concentrations at death (n = 12 mice for both LFD groups, n = 11 mice for both HFD groups). NormMg-LFD (white circles), LowMg-LFD (grey circles), NormMg-HFD (white squares), LowMg-HFD (grey squares). Data are mean ± SEM. Depending on the absence or presence of a significant interaction effect between dietary fat and Mg2+ content, either a two-way ANOVA (Tukey’s multiple comparison test) or an unpaired multiple t test (Holm–Sidak multiple comparison test) approach, respectively, was used to determine statistical significance. *p < 0.05 for the comparisons shown

Both HFD-fed groups demonstrated increased insulin resistance in the ITT compared with their respective controls (Fig. 2f,g). Low dietary Mg2+ content resulted in a significantly lower AUC of the ITT (Fig. 2g, two-way ANOVA for dietary Mg2+ effect p < 0.05). In the LowMg-HFD group compared with the NormMg-HFD-fed mice, the AUC of the ITT was not significantly different (0.91 ± 0.05 vs 0.72 ± 0.05 mol/l × min in NormMg-HFD-fed and LowMg-HFD-fed mice, respectively, Tukey’s test p = 0.07, Fig. 2f,g).

Insulin resistance is often accompanied by hyperlipidaemia, in particular, high triacylglycerol and NEFA levels. As expected, the HFD-fed mice had higher serum triacylglycerol and NEFA levels than LFD-fed mice (Fig. 2h,i). Interestingly, despite their lower body weight and increased insulin sensitivity, LowMg-HFD-fed mice also had high serum triacylglycerol and NEFA (Fig. 2h,i). In contrast, serum leptin levels correlated with body weight; hence, reduced leptin levels were observed in the LowMg-HFD-fed mice compared with NormMg-HFD-fed mice (Fig. 2j). No difference between the two HFD groups was observed in serum adiponectin and cholesterol (ESM Fig. 1a,b).

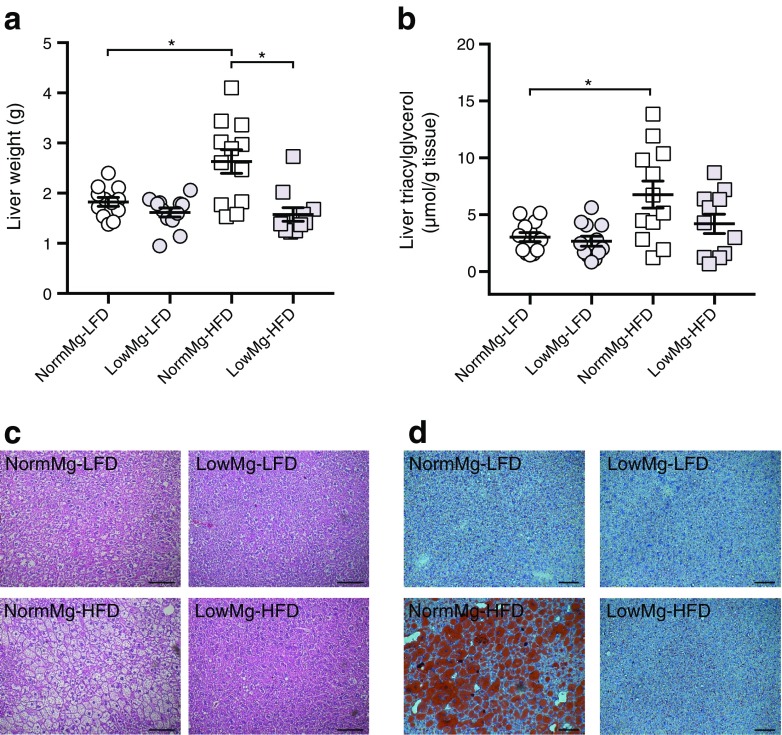

Mg2+ deficiency prevents diet-induced hepatic lipid storage

Liver function is often impaired in type 2 diabetes as a consequence of insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis [28]. Feeding mice a NormMg-HFD resulted in a significantly heavier liver. However, this effect was abrogated in mice fed a LowMg-HFD (Fig. 3a). In Mg2+-deficient mice, the HFD did not increase liver triacylglycerol content (Fig. 3b). In line with the triacylglycerol measurements, H&E and Oil Red O staining showed reduced hepatic lipid accumulation in the Mg2+-deficient HFD-fed mice (Fig. 3c,d, respectively). Hepatic mRNA expression of Cd36, a long-chain fatty acid transporter, was reduced in the LowMg-HFD-fed mice compared with the NormMg-HFD-fed mice (ESM Fig. 2a). Low dietary Mg2+ increased hepatic mRNA expression of sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1c (Srebp1c), which is involved in cholesterol and fatty acid metabolism, and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 1 (Pepck1), essential for gluconeogenesis, glyceroneogenesis and fatty acid re-esterification (ESM Fig. 2b,c, two-way ANOVA for dietary Mg2+ effect p < 0.05). No differences were observed between the two HFD-fed groups in the expression of key genes involved in hepatic glycolysis, ketogenesis and β oxidation (ESM Fig. 2d–l).

Fig. 3.

Mg2+ deficiency prevents diet-induced hepatic lipid storage. Liver (a) weight and (b) triacylglycerol content at death (17 weeks, n = 12 mice per group, n = 11 mice for the LowMg-HFD group). Representative images of livers stained with (c) H&E or (d) Oil Red O. Scale bars, 100 μm. NormMg-LFD (white circles), LowMg-LFD (grey circles), NormMg-HFD (white squares), LowMg-HFD (grey squares). Data are mean ± SEM. Depending on the absence or presence of a significant interaction effect between dietary fat and Mg2+ content, either a two-way ANOVA (Tukey’s multiple comparison test) or an unpaired multiple t test (Holm–Sidak multiple comparison test) approach was used to determine statistical significance, respectively. *p < 0.05 for the comparisons shown

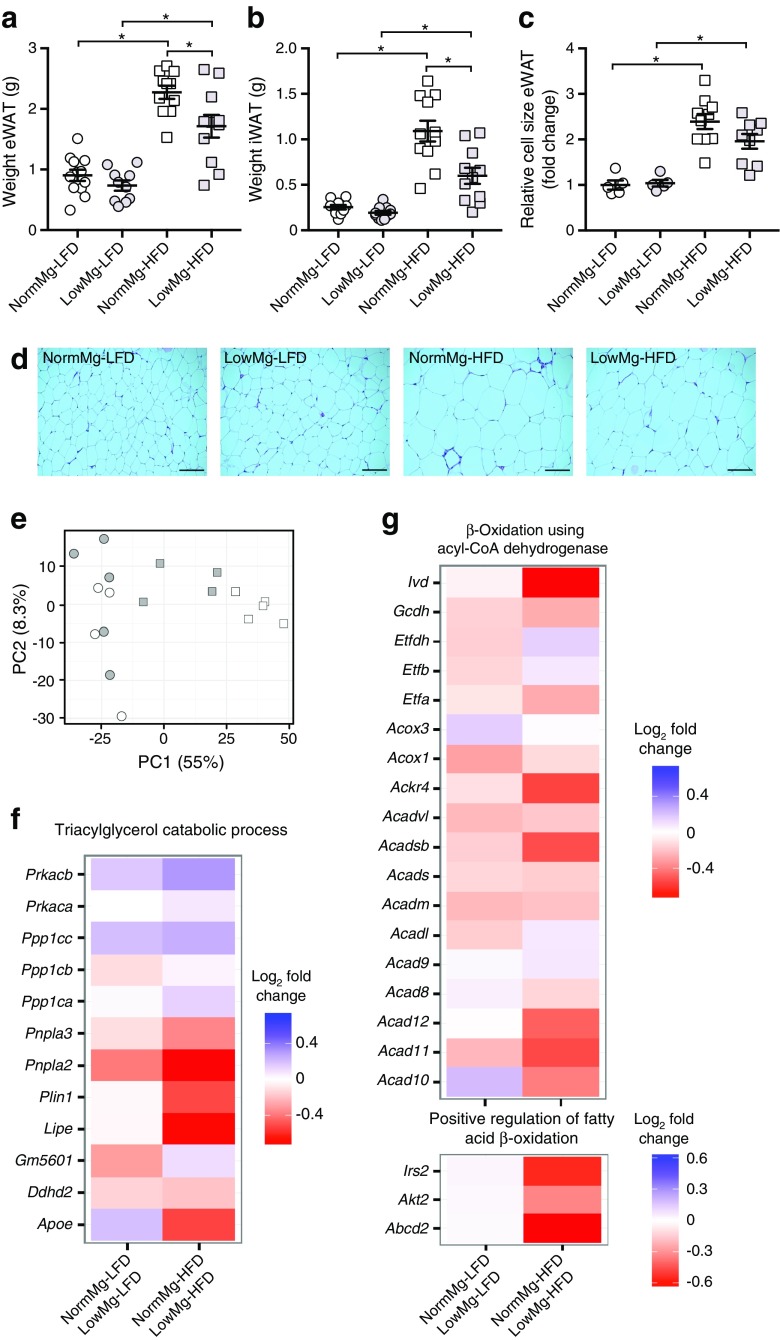

Reduced adipose tissue mass in Mg2+-deficient HFD-fed mice is associated with increased mRNA expression of lipolysis genes

Our results show that mice fed a LowMg-HFD diet exhibit reduced body weight and high triacylglycerol levels compared with their NormMg-HFD-fed littermates. Interestingly, the LowMg-HFD group had decreased mass of epididymal and inguinal white adipose tissue (eWAT and iWAT, respectively) (Fig. 4a,b), which may point towards defective lipid handling in white adipose tissue (WAT). The HFD increased adipocyte size (Fig. 4c,d), but no significant difference was observed between the two HFD groups (Fig. 4c,d). Nevertheless, quantitative PCR showed that mRNA expression of Srebp1c, Pepck1 and genes involved in β oxidation was increased in the eWAT of the LowMg-HFD group compared with the NormMg-HFD group (ESM Fig. 3a–f).

Fig. 4.

Reduced adipose tissue mass in Mg2+-deficient HFD-fed mice is associated with increased mRNA expression of lipolysis genes in eWAT. Weight of (a) eWAT, (b) iWAT and (c) eWAT cell size at death (17 weeks, n = 12 mice per group, n = 11 mice for the LowMg-HFD group). NormMg-LFD (white circles), LowMg-LFD (grey circles), NormMg-HFD (white squares), LowMg-HFD (grey squares). Data are mean ± SEM. Depending on the absence or presence of a significant interaction effect between dietary fat and Mg2+ content, either a two-way ANOVA (Tukey’s multiple comparison test) or an unpaired multiple t test (Holm–Sidak multiple comparison test) approach was used, respectively, to determine statistical significance. (d) Representative images of H&E stained eWAT. Scale bars, 100 μm. (e) Principal component (PC) analysis of RNA sequencing on eWAT. NormMg-LFD (white circles, n = 4), LowMg-LFD (grey circles, n = 5), NormMg-HFD (white squares, n = 5), LowMg-HFD (grey squares, n = 4). The percentages on the x-axis and y-axis indicate the total percentage of variance explained by the first two principal components, respectively. GO term analyses of the pathways (f) ‘triacylglycerol catabolic process’ and (g) ‘β-oxidation using acyl-CoA dehydrogenase’; and ‘positive regulation of fatty acid β-oxidation’. Gene expression changes are presented as log2 fold change with the NormMg2+ diet as reference, so that a negative value (in red) indicates a decrease in expression in the NormMg2+ vs LowMg2+ groups. *p < 0.05 for the comparisons shown

To determine the consequences of low Mg2+ on lipid metabolism, we performed RNA sequencing on eWAT. A principal component analysis using the log2 transformed expression values shows that the samples from both LFD groups cluster closely together, indicating the absence of a strong Mg2+ effect, whereas there is a clear separation of NormMg-HFD vs LowMg-HFD gene expression profiles (Fig. 4e). To investigate the effect of Mg2+ on specific biological pathways, the fold changes for groups of genes belonging to the same gene ontology (GO) were analysed. GO term analysis indicated that processes associated with adiposity (e.g. inflammation) were downregulated in LowMg-HFD-fed vs NormMg-HFD-fed mice, in accordance with decreased adipose tissue mass (ESM Table 2). Interestingly, despite the increased insulin sensitivity of the LowMg-HFD-fed mice, several key genes involved in the triacylglycerol catabolism pathway (lipolysis) were upregulated in the LowMg-HFD vs the NormMg-HFD group, which may explain the reduced lipid storage as well as the high serum NEFA levels (Fig. 4f). A modest increase in acyl-CoA dehydrogenase dependent β oxidation was observed in the LowMg-HFD-fed mice vs the NormMg-HFD-fed mice (Fig. 4g). The metabolic effects of Mg2+ in eWAT appear to be specific to lipid homeostasis, as there was no clear effect on glycolysis (ESM Fig. 3g). Although serum cholesterol levels were not different between the experimental groups, cholesterol biosynthesis was greatly reduced in the LowMg-HFD-fed vs the NormMg-HFD-fed mice (ESM Fig. 3h, ESM Table 2).

To investigate whether hypomagnesaemia has a direct effect on lipolysis in eWAT, we examined the effect of Mg2+ on lipolysis in differentiated 3 T3-L1 cells in vitro. Unstimulated lipolysis was not different at 0 or 1 mmol/l Mg2+, indicating that Mg2+ deficiency does not directly induce lipolysis in adipocytes (ESM Fig. 4a).

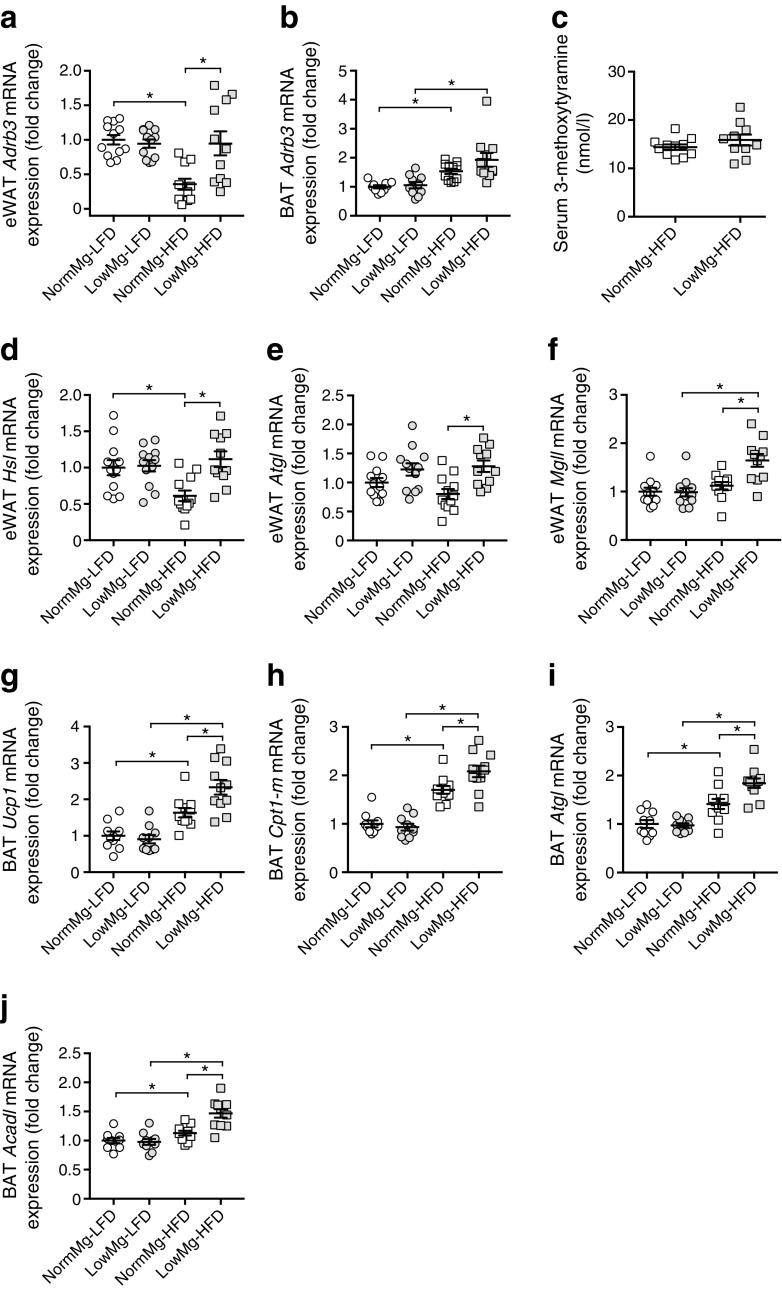

mRNA expression of the β3-adrenergic receptor is increased in LowMg-HFD mice

β3-Adrenergic receptors (ADRB3) are essential regulators of lipid metabolism, increasing brown adipose tissue (BAT) activity and reducing WAT lipid storage via activation of lipolysis [29–32]. We therefore explored whether enhanced β-adrenergic signalling could explain the high triacylglycerol levels, increased lipolysis and reduced body weight of Mg2+-deficient HFD-fed mice. Expression of Adrb3 was significantly increased by 2.5-fold in the eWAT of LowMg-HFD-fed compared with NormMg-HFD-fed mice (Fig. 5a). Additionally, both HFD-fed groups showed elevated mRNA expression of Adrb3 in BAT, but this upregulation was more pronounced in the LowMg-HFD group (Fig. 5b). To determine whether this was the result of enhanced adrenaline (epinephrine) release, serum levels of the dopamine metabolite 3-methoxytyramine and the adrenaline metabolite normetanephrine were measured. However, no significant increase was observed (Fig. 5c and ESM Fig. 5a). mRNA expression of the lipolysis genes adipose triacylglycerol lipase (Atgl), hormone-sensitive lipase (Hsl) and monoglyceride lipase (Mgll) was significantly increased in eWAT of Mg2+-deficient HFD-fed mice compared with the NormMg-HFD group (Fig. 5d–f).

Fig. 5.

mRNA expression of the β3-adrenergic receptor is increased in eWAT of LowMg-HFD-fed mice. Relative mRNA expression of Adrb3 in (a) eWAT and (b) BAT, normalised to Gapdh expression, relative to NormMg-LFD. (c) Serum 3-methoxytyramine concentration at death (17 weeks, n = 12 mice in the NormMg-HFD group, n = 11 in the LowMg-HFD group). eWAT mRNA expression of genes essential for lipolysis, (d) Hsl, (e) Atgl and (f) Mgll, normalised to Gapdh expression, relative to NormMg-LFD (n = 12 mice per group, n = 11 mice for the LowMg-HFD group). BAT mRNA expression of (g) Ucp1 and genes involved in fatty acid metabolism, (h) Cpt1-m, (i) Atgl and (j) Acadl, normalised to Gapdh expression, relative to NormMg-LFD (n = 10 mice for both LFD groups, n = 11 mice for both HFD groups). NormMg-LFD (white circles), LowMg-LFD (grey circles), NormMg-HFD (white squares), LowMg-HFD (grey squares). Data are mean ± SEM. Depending on the absence or presence of a significant interaction effect between dietary fat and Mg2+ content, either a two-way ANOVA (Tukey’s multiple comparison test) or an unpaired multiple t test (Holm–Sidak multiple comparison test) approach, respectively, was used to determine statistical significance. Statistical significance in 3-methoxytyramine levels was assessed using a t test. *p < 0.05 for the comparisons shown

Expression of Ucp1 in BAT, which is essential for non-shivering thermogenesis, was upregulated in NormMg-HFD-fed mice compared with NormMg-LFD-fed mice (Fig. 5g). In line with increased β3-adrenergic signalling, Ucp1 expression was further increased in BAT of LowMg-HFD-fed mice. BAT thermogenesis is strongly regulated by fatty acid availability [33]. Indeed, genes involved in NEFA metabolism of BAT are upregulated (Fig. 5h–j) (Atgl, Cpt1-m and Acadl). In contrast, mRNA levels of glucose transporters 1 and 4 (Glut1/4) in BAT were unchanged in LowMg-HFD-fed compared with NormMg-HFD-fed mice (ESM Fig. 5b,c). mRNA expression of the fatty acid transporter Cd36 and of the important metabolic transcription factors peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (Pparα) and gamma (Pparγ) remained unchanged in BAT between the NormMg-HFD-fed and LowMg-HFD-fed mice (ESM Fig. 5d–f).

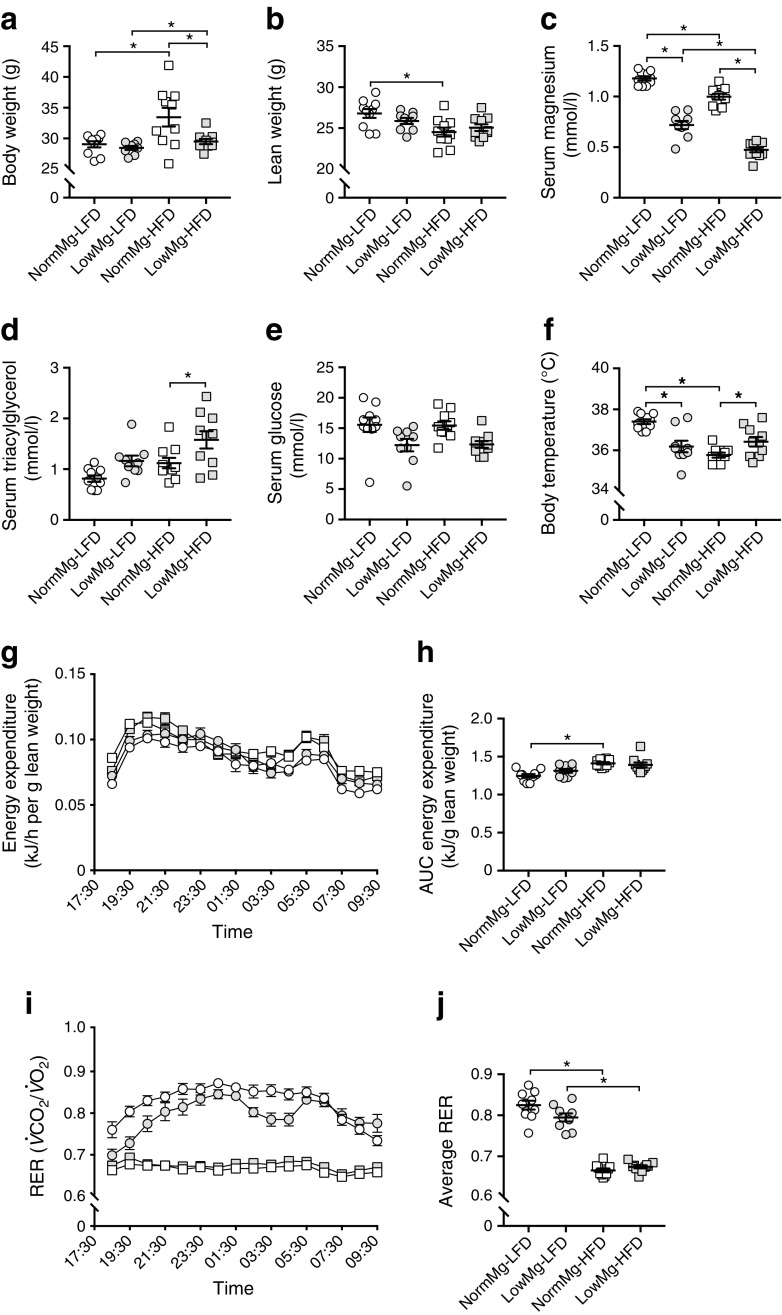

LowMg-HFD-fed mice have increased body temperature but equal energy expenditure

To investigate the energy metabolism in Mg2+-deficient HFD-fed mice, the dietary intervention study was repeated with respiratory cages. Respiration, body temperature and activity were measured at week 8, which was when the weight differences developed in our first experiment. In line with the previous experiment, no differences were observed in food and water intake between the two HFD-fed groups (ESM Fig. 6a–d); and the Mg2+-deficient HFD-fed mice had reduced body weight compared with the NormMg-HFD-fed mice (Fig. 6a). Lean body mass was not different between the two HFD groups, indicating that the weight difference depends on adipose tissue mass (Fig. 6b). As with our previous experiment, the HFD caused a reduction in serum Mg2+ levels (Fig. 6c). A significant increase was observed in serum triacylglycerol when the animals were killed (after 9 weeks) in the LowMg-HFD group compared with the NormMg-HFD group (Fig. 6d). Low dietary Mg2+-fed mice had decreased non-fasted serum glucose (Fig. 6e; two-way ANOVA for dietary Mg2+ effect p < 0.05), while the difference between the two HFD-fed groups was not significant (NormMg-HFD vs LowMg-HFD, Tukey’s test p = 0.07). Hypomagnesaemia and HFD decreased core body temperature (Fig. 6f). In contrast, the body temperature of LowMg-HFD-fed mice was higher than NormMg-HFD-fed mice (Fig. 6f; 35.8 ± 0.1 vs 36.4 ± 0.2°C in NormMg-HFD and LowMg-HFD, p < 0.05), in line with increased BAT activity. Moreover, mice fed a Mg2+-deficient diet showed increased locomotor activity (ESM Fig. 6e,f; two-way ANOVA for dietary Mg2+ effect p < 0.05). However, energy expenditure was not different between the two HFD-fed groups (Fig. 6g,h). In both HFD groups, the respiratory exchange ratio (RER) was approximately 0.7, indicating that fatty acids are the main energy source (Fig. 6i,j). Interestingly, in the LFD groups, hypomagnesaemia resulted in a reduction of the RER (Fig. 6i,j), suggesting an increased use of fatty acids as an energy substrate over glucose. However, this reduction was not statistically significant (Fig. 6j; 0.82 ± 0.01 vs 0.79 ± 0.01 average RER in NormMg-LFD and LowMg-LFD, respectively; p = 0.10).

Fig. 6.

LowMg-HFD-fed mice have increased body temperature but equal energy expenditure. To study energy expenditure, a replication animal study was performed for a duration of 9 weeks. (a) Body weight and (b) lean body weight of the animals (n = 10 mice per group, n = 9 mice in the LowMg-LFD group) at death (9 weeks). Non-fasted serum (c) Mg2+, (d) triacylglycerol and (e) glucose concentrations at death (glucose at 9 weeks, two-way ANOVA for dietary Mg2+ effect p < 0.05; NormMg-HFD vs LowMg-HFD Tukey’s test p = 0.07). (f) Body temperature measured by rectal probe after 8 weeks of dietary intervention. Respiratory metabolic cages were used to determine energy expenditure and RER. (g) Energy expenditure averaged per hour, measured after 8 weeks of dietary intervention and corrected for lean weight, (h) from which the AUC is calculated. NormMg-LFD (white circles, n = 10), LowMg-LFD (grey circles, n = 9), NormMg-HFD (white squares, n = 10), LowMg-HFD (grey squares, n = 10). (i) RER averaged per hour, measured after 8 weeks of dietary intervention. RER is determined by dividing the CO2 production by the O2 intake. (j) Average RER over the entire duration of the measurement (from 18:30 to 09:30 h). NormMg-LFD (white circles), LowMg-LFD (grey circles), NormMg-HFD (white squares), LowMg-HFD (grey squares). Data are mean ± SEM. Depending on the absence or presence of a significant interaction effect between dietary fat and Mg2+ content, either a two-way ANOVA (Tukey’s multiple comparison test) or an unpaired multiple t test (Holm–Sidak multiple comparison test) approach, respectively, was used to determine statistical significance. *p < 0.05 for the comparisons shown

Discussion

Hypomagnesaemia has been repeatedly reported in type 2 diabetes and the metabolic syndrome [1, 2, 14], but the role of Mg2+ in lipid metabolism has been largely overlooked. Here, we demonstrate that low dietary Mg2+ intake ameliorates HFD-induced obesity. The lower body weight results in beneficial metabolic effects including improved insulin sensitivity, reduced hepatic steatosis and lower WAT inflammation. Nevertheless, serum triacylglycerol and NEFA concentrations were increased in the low Mg2+ HFD group, corresponding to increased eWAT mRNA expression of lipolysis genes. These findings establish Mg2+ as an important regulator of body weight and lipid metabolism.

In this study, a Mg2+-deficient diet ameliorated HFD-induced weight gain in mice. This was the result of reduced adiposity, because lean body mass was similar between the two HFD groups and both eWAT and iWAT weight were lower in mice fed a LowMg-HFD compared with a NormMg-HFD. The reduced body weight was associated with favourable metabolic effects. IPGTT, IPITT and fasting glucose levels indicated enhanced insulin sensitivity. Moreover, the reduced body weight of the LowMg-HFD mice led to a complete absence of hepatic steatosis and RNA sequencing of the eWAT demonstrated downregulation of pro-inflammatory pathways. Despite these beneficial effects, blood lipid levels remained high. In line with our data, others have demonstrated that low dietary Mg2+ intake reduced body weight in several rat models of Mg2+ deficiency [34–37]. However, these studies did not address the underlying cause or investigate the effects on lipid metabolism.

Our animal data is strengthened by the results of Chubanov et al [17] where severe hypomagnesaemia via Trpm6 knockout also resulted in a catabolic phenotype and improved insulin sensitivity [17]. The catabolic phenotype of Mg2+-deficient mice leads to hyperlipidaemia, which has considerable adverse effects in individuals with type 2 diabetes [38, 39]. Nevertheless, the low Mg2+ HFD does not completely mimic the human situation because the hypomagnesaemia induced in mice is more severe [1]. Moreover, an unhealthy human diet consists of both high fat and sugar, whereas the HFD in mice purely depends on palm oil. Indeed, Mg2+-deficiency in high-fructose diets has adversely affected insulin sensitivity and lipid homeostasis in rats. This shows the considerable differences in the role of Mg2+ in the metabolism of lipids vs carbohydrates [40, 41]. Future studies should investigate the role of Mg2+ in combined fat and sugar diets. These differences may explain why, in humans, higher oral Mg2+ intake and Mg2+ supplementation have beneficial effects on metabolic variables, which apparently contrasts with our animal data [18–20].

In our study, the reduced WAT mass of LowMg-HFD-fed mice was associated with enhanced lipolysis gene expression, causing high serum NEFA and triacylglycerol levels. These findings suggest that LowMg-HFD-fed mice depend more on mitochondrial β-oxidation, rather than glycolysis, for energy production. However, our energy metabolism experiments demonstrated neither differences in energy expenditure nor in RER between the NormMg-HFD and LowMg-HFD groups. It should be noted, however, that both HFD groups mainly depend on lipids for energy metabolism, masking potential RER differences between these groups. Moreover, despite equal energy expenditure, the NormMg-HFD-fed mice are considerably heavier than LowMg-HFD-fed mice and therefore have a higher energy demand. Several studies have discussed the considerable difficulties associated with the interpretation of energy expenditure data and emphasised that body weight differences complicate interpretation [42, 43]. Increased thermogenesis may explain why energy expenditure does not differ between LowMg-HFD-fed and the heavier NormMg-HFD-fed mice. Although the effects are modest, the LowMg-HFD-fed mice had a significantly higher body temperature and increased Ucp1 expression in BAT, indicative of higher thermogenesis. Cold-exposure studies are necessary to further investigate the role of Mg2+ status in BAT activation, WAT browning and thermogenesis.

The increased lipolysis and brown adipose tissue activity were associated with higher β3-adrenergic receptor expression in eWAT and BAT of LowMg-HFD-fed mice. β3-receptor knockout mice have increased lipid stores and impaired WAT browning [44, 45]. Activation of the β3-adrenergic receptors in mice using agonist CL316243 decreases adipose tissue mass, improves insulin sensitivity, increases uncoupling protein-1 (UCP1)-dependent thermogenesis and activates a cycle of concomitant lipolysis and de novo lipogenesis [46, 47]. Interestingly, this is exactly the phenotype that was observed in the LowMg-HFD-fed mice, although to a lesser extent. A link between Mg2+, β-adrenergic signalling and lipolysis is not without precedent. Use of β-adrenergic agonists, which stimulate lipolysis, have been associated with decreased blood Mg2+ levels [1, 48, 49]. Mg2+ has also been shown to reduce catecholamine release from the adrenal medulla [50] and Mg2+ deficiency is associated with higher urinary levels of adrenaline and noradrenaline (norepinephrine) [37]. Moreover, Mg2+ supplementation has been suggested to regulate lipolysis, as it prevents hyperlipidaemia in diabetic rats and reduces serum triacylglycerol levels in individuals with type 2 diabetes [20, 51]. Further research is required to determine exactly how hypomagnesaemia increases β-adrenergic signalling and how β-adrenergic signalling can induce hypomagnesaemia.

A strength of this study is that the model used to induce type 2 diabetes and low dietary Mg2+ intake closely resembles the human situation. The Western diet contains high amounts of processed foods consisting of high energy and low Mg2+. Moreover, the extensive phenotyping of the animals in this study provides new avenues for research into the pivotal role of Mg2+ in metabolism. The data obtained in this study are robust, as a replicate animal experiment was performed in a separate institution, confirming our results.

Our study has limitations. First, because of the large weight differences induced by the Mg2+ deficient diet, it is difficult to specifically attribute the metabolic changes of the mice to their lower body weight or their Mg2+ deficiency. In addition, our study design did not allow us to study in more depth the contribution of disturbed β-adrenergic signalling to the differences in body weight, eWAT lipolysis, BAT activity and hyperlipidaemia. Although our data and previous studies support a role for Mg2+ in β-adrenergic signalling [37, 50], further studies are required to establish the exact role of Mg2+ in catecholamine secretion and signalling.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that hypomagnesaemia in mice prevents HFD-induced weight gain by enhanced BAT activity and increased eWAT lipolysis gene expression. Consequently, this led to improved insulin sensitivity and absent hepatic steatosis. These results underline the pivotal function of Mg2+ in maintaining a healthy energy metabolism.

Electronic supplementary material

(PDF 2710 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors thank M. Voet, F. Krewinkel, T. Peters, K. de Haas-Cremers, M. School, H. Janssen-Wagener, S. Mulder, T. van Herwaarden, A. Hijmans (Radboud Institute for Molecular Life Sciences, Radboud university medical center, Nijmegen, the Netherlands) for their excellent technical support with the animal study and measurements, and H. Cater, M. Rohm and M. Brereton (Department of Physiology, Anatomy & Genetics, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK) for their insights and scientific input. Some of the data were presented as an abstract and poster at the Experimental Biology meeting in Chicago in 2017.

Abbreviations

- BAT

Brown adipose tissue

- eWAT

Epididymal white adipose tissue

- HFD

High-fat diet

- GO

Gene ontology

- iWAT

Inguinal white adipose tissue

- LFD

Low-fat diet

- LowMg

Low Mg2+ (diet)

- NormMg

Normal Mg2+ (diet)

- RER

Respiratory exchange ratio

- WAT

White adipose tissue

Contribution statement

SK, JdB, JH, RB, FA and CT conceived and designed the study; SK, JdB, JvD, CO-B and WA contributed to data acquisition; SK, JdB, JvD and WA analysed the data; all authors interpreted the data, drafted the article, revised it and approved the final version. JdB is the guarantor of this work.

Funding

This work was supported by funding from the Radboud Institute for Molecular Life Sciences and by grants from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (J. Hoenderop, the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) VICI 016.130.668), the Wellcome Trust (884655, 089795) and the European Research Council (ERC; 322620). J. van Diepen is supported by a Veni Grant from NWO (NWO VENI 91616083). J. de Baaij is supported by grants from NWO (Rubicon 825.14.021, NWO VENI 016.186.012) and the Dutch Diabetes Research Foundation (2017.81.014). F. Ashcroft holds an ERC Advanced Investigatorship and a Royal Society Research Wolfson Merit Award.

Data availability

The data and materials that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The RNA sequencing data have been submitted to the gene expression omnibus (GEO) database (accession no. GSE116270).

Duality of interest

The authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

References

- 1.Kurstjens S, de Baaij JH, Bouras H, Bindels RJ, Tack CJ, Hoenderop JG. Determinants of hypomagnesaemia in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Eur J Endocrinol. 2017;176:11–19. doi: 10.1530/EJE-16-0517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pham PC, Pham PM, Pham SV, Miller JM, Pham PT. Hypomagnesaemia in patients with type 2 diabetes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2:366–373. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02960906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dong JY, Xun P, He K, Qin LQ. Magnesium intake and risk of type 2 diabetes: meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:2116–2122. doi: 10.2337/dc11-0518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gommers LM, Hoenderop JG, Bindels RJ, de Baaij JH. Hypomagnesaemia in type 2 diabetes: a vicious circle? Diabetes. 2016;65:3–13. doi: 10.2337/db15-1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kieboom BC, Ligthart S, Dehghan A, et al. Serum magnesium and the risk of prediabetes: a population-based cohort study. Diabetologia. 2017;60:843–853. doi: 10.1007/s00125-017-4224-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hassan SAU, Ahmed I, Nasrullah A, et al. Comparison of serum magnesium levels in overweight and obese children and normal weight children. Cureus. 2017;9:e1607. doi: 10.7759/cureus.1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kirii K, Iso H, Date C, Fukui M, Tamakoshi A, JACC Study Group Magnesium intake and risk of self-reported type 2 diabetes among Japanese. J Am Coll Nutr. 2010;29:99–106. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2010.10719822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guerrero-Romero F, Flores-Garcia A, Saldana-Guerrero S, Simental-Mendia LE, Rodriguez-Moran M. Obesity and hypomagnesaemia. Eur J Intern Med. 2016;34:29–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2016.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Baaij JH, Hoenderop JG, Bindels RJ. Magnesium in man: implications for health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2015;95:1–46. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00012.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harrison WH, Boyer PD, Falcone AB. The mechanism of enzymic phosphate transfer reactions. J Biol Chem. 1955;215:303–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilson JE, Chin A. Chelation of divalent cations by ATP, studied by titration calorimetry. Anal Biochem. 1991;193:16–19. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(91)90036-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garfinkel L, Garfinkel D. Magnesium regulation of the glycolytic pathway and the enzymes involved. Magnesium. 1985;4:60–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shigematsu M, Nakagawa R, Tomonaga S, Funaba M, Matsui T (2016) Fluctuations in metabolite content in the liver of magnesium-deficient rats. Br J Nutr 1–6 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Nadler JL, Buchanan T, Natarajan R, Antonipillai I, Bergman R, Rude R. Magnesium deficiency produces insulin resistance and increased thromboxane synthesis. Hypertension. 1993;21:1024–1029. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.21.6.1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suarez A, Pulido N, Casla A, Casanova B, Arrieta FJ, Rovira A. Impaired tyrosine-kinase activity of muscle insulin receptors from hypomagnesaemic rats. Diabetologia. 1995;38:1262–1270. doi: 10.1007/BF00401757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vicario PP, Bennun A. Separate effects of Mg2+, MgATP, and ATP4- on the kinetic mechanism for insulin receptor tyrosine kinase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1990;278:99–105. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(90)90236-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chubanov V, Ferioli S, Wisnowsky A, et al. Epithelial magnesium transport by TRPM6 is essential for prenatal development and adult survival. eLife. 2016;5:e20914. doi: 10.7554/eLife.20914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rodriguez-Moran M, Guerrero-Romero F. Oral magnesium supplementation improves insulin sensitivity and metabolic control in type 2 diabetic subjects: a randomized double-blind controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1147–1152. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.4.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hadjistavri LS, Sarafidis PA, Georgianos PI, et al. Beneficial effects of oral magnesium supplementation on insulin sensitivity and serum lipid profile. Med Sci Monit. 2010;16:CR307–CR312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lal J, Vasudev K, Kela AK, Jain SK. Effect of oral magnesium supplementation on the lipid profile and blood glucose of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Assoc Physicians India. 2003;51:37–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song Y, He K, Levitan EB, Manson JE, Liu S. Effects of oral magnesium supplementation on glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of randomized double-blind controlled trials. Diabet Med. 2006;23:1050–1056. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gueux E, Rayssiguier Y, Piot MC, Alcindor L. Reduction of plasma lecithin—cholesterol acyltransferase activity by acute magnesium deficiency in the rat. J Nutr. 1984;114:1479–1483. doi: 10.1093/jn/114.8.1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rayssiguier Y, Noe L, Etienne J, Gueux E, Cardot P, Mazur A. Effect of magnesium deficiency on post-heparin lipase activity and tissue lipoprotein lipase in the rat. Lipids. 1991;26:182–186. doi: 10.1007/BF02543968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim D, Langmead B, Salzberg SL. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods. 2015;12:357–360. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li B, Dewey CN. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:323. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wickham H. Ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. New York: Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hazlehurst JM, Woods C, Marjot T, Cobbold JF, Tomlinson JW. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and diabetes. Metab Clin Exp. 2016;65:1096–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Collins S. β-Adrenoceptor signaling networks in adipocytes for recruiting stored fat and energy expenditure. Front Endocrinol. 2011;2:102. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2011.00102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Souza CJ, Burkey BF. Beta 3-adrenoceptor agonists as anti-diabetic and anti-obesity drugs in humans. Curr Pharm Des. 2001;7:1433–1449. doi: 10.2174/1381612013397339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lowell BB, Flier JS. Brown adipose tissue, beta 3-adrenergic receptors, and obesity. Annu Rev Med. 1997;48:307–316. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.48.1.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meyers DS, Skwish S, Dickinson KE, Kienzle B, Arbeeny CM. Beta 3-adrenergic receptor-mediated lipolysis and oxygen consumption in brown adipocytes from cynomolgus monkeys. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:395–401. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.2.3738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Townsend KL, Tseng YH. Brown fat fuel utilization and thermogenesis. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2014;25:168–177. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bertinato J, Lavergne C, Rahimi S et al (2016) Moderately low magnesium intake impairs growth of lean body mass in obese-prone and obese-resistant rats fed a high-energy diet. Nutrients 8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Chaudhary DP, Boparai RK, Bansal DD. Effect of a low magnesium diet on in vitro glucose uptake in sucrose fed rats. Magnes Res. 2007;20:187–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kimura Y, Murase M, Nagata Y. Change in glucose homeostasis in rats by long-term magnesium-deficient diet. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol. 1996;42:407–422. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.42.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murasato Y, Harada Y, Ikeda M, Nakashima Y, Hayashida Y. Effect of magnesium deficiency on autonomic circulatory regulation in conscious rats. Hypertension. 1999;34:247–252. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.34.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Klop B, Elte JW, Cabezas MC. Dyslipidemia in obesity: mechanisms and potential targets. Nutrients. 2013;5:1218–1240. doi: 10.3390/nu5041218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hendrani AD, Adesiyun T, Quispe R, et al. Dyslipidemia management in primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: current guidelines and strategies. World J Cardiol. 2016;8:201–210. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v8.i2.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rayssiguier Y, Gueux E, Nowacki W, Rock E, Mazur A. High fructose consumption combined with low dietary magnesium intake may increase the incidence of the metabolic syndrome by inducing inflammation. Magnes Res. 2006;19:237–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Olatunji LA, Soladoye AO. Increased magnesium intake prevents hyperlipidemia and insulin resistance and reduces lipid peroxidation in fructose-fed rats. Pathophysiology. 2007;14:11–15. doi: 10.1016/j.pathophys.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guo J, Hall KD (2011) Challenges of indirect calorimetry in mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 300:R780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Tschop MH, Speakman JR, Arch JR, et al. A guide to analysis of mouse energy metabolism. Nat Methods. 2011;9:57–63. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jimenez M, Barbatelli G, Allevi R, et al. Beta 3-adrenoceptor knockout in C57BL/6J mice depresses the occurrence of brown adipocytes in white fat. Eur J Biochem. 2003;270:699–705. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Susulic VS, Frederich RC, Lawitts J, et al. Targeted disruption of the beta 3-adrenergic receptor gene. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:29483–29492. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.49.29483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mottillo EP, Balasubramanian P, Lee YH, Weng C, Kershaw EE, Granneman JG. Coupling of lipolysis and de novo lipogenesis in brown, beige, and white adipose tissues during chronic beta3-adrenergic receptor activation. J Lipid Res. 2014;55:2276–2286. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M050005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xiao C, Goldgof M, Gavrilova O, Reitman ML. Anti-obesity and metabolic efficacy of the beta3-adrenergic agonist, CL316243, in mice at thermoneutrality compared to 22 degrees C. Obesity. 2015;23:1450–1459. doi: 10.1002/oby.21124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Flink EB, Shane SR, Scobbo RR, Blehschmidt NG, McDowell P. Relationship of free fatty acids and magnesium in ethanol withdrawal in dogs. Metab Clin Exp. 1979;28:858–865. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(79)90213-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bodenhamer J, Bergstrom R, Brown D, Gabow P, Marx JA, Lowenstein SR. Frequently nebulized beta-agonists for asthma: effects on serum electrolytes. Ann Emerg Med. 1992;21:1337–1342. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0644(05)81898-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aguirre J, Pinto JE, Trifaro JM. Calcium movements during the release of catecholamines from the adrenal medulla: effects of methoxyverapamil and external cations. J Physiol. 1977;269:371–394. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1977.sp011907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Soltani N, Keshavarz M, Dehpour AR. Effect of oral magnesium sulfate administration on blood pressure and lipid profile in streptozocin diabetic rat. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;560:201–205. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 2710 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The data and materials that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The RNA sequencing data have been submitted to the gene expression omnibus (GEO) database (accession no. GSE116270).