Virus infections of phytopathogenic fungi occasionally impair growth, reproduction, and virulence, a phenomenon referred to as hypovirulence. Hypovirulence-inducing mycoviruses, therefore, represent a powerful means to defeat fungal epidemics on crop plants. However, the poor understanding of the molecular basis of hypovirulence induction limits their application. Using the devastating fungal pathogen on cereal crops, Fusarium graminearum, we identified an mRNA binding protein (named virus response 1, vr1) which is involved in symptom expression. Downregulation of vr1 in the virus-infected fungus and vr1 deletion evoke virus infection-like symptoms, while constitutive expression overrules the cytopathic effects of the virus infection. Intriguingly, the presence of a specific viral structural protein is sufficient to trigger the fungal response, i.e., vr1 downregulation, and symptom development similar to virus infection. The advancements in understanding fungal infection and response may aid biological pest control approaches using mycoviruses or viral proteins to prevent future Fusarium epidemics.

KEYWORDS: mycovirus, hypovirulence, fungal response, Fusarium graminearum, Chrysoviridae, FgV-ch9

ABSTRACT

Infections of fungi by mycoviruses are often symptomless but sometimes also fatal, as they perturb sporulation, growth, and, if applicable, virulence of the fungal host. Hypovirulence-inducing mycoviruses, therefore, represent a powerful means to defeat fungal epidemics on crop plants. Infection with Fusarium graminearum virus China 9 (FgV-ch9), a double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) chrysovirus-like mycovirus, debilitates Fusarium graminearum, the causal agent of fusarium head blight. In search for potential symptom alleviation or aggravation factors in F. graminearum, we consecutively infected a custom-made F. graminearum mutant collection with FgV-ch9 and found a mutant with constantly elevated expression of a gene coding for a putative mRNA-binding protein that did not show any disease symptoms despite harboring large amounts of virus. Deletion of this gene, named virus response 1 (vr1), resulted in phenotypes identical to those observed in the virus-infected wild type with respect to growth, reproduction, and virulence. Similarly, the viral structural protein coded on segment 3 (P3) caused virus infection-like symptoms when expressed in the wild type but not in the vr1 overexpression mutant. Gene expression analysis revealed a drastic downregulation of vr1 in the presence of virus and in mutants expressing P3. We conclude that symptom development and severity correlate with gene expression levels of vr1. This was confirmed by comparative transcriptome analysis, showing a large transcriptional overlap between the virus-infected wild type, the vr1 deletion mutant, and the P3-expressing mutant. Hence, vr1 represents a fundamental host factor for the expression of virus-related symptoms and helps us understand the underlying mechanism of hypovirulence.

IMPORTANCE Virus infections of phytopathogenic fungi occasionally impair growth, reproduction, and virulence, a phenomenon referred to as hypovirulence. Hypovirulence-inducing mycoviruses, therefore, represent a powerful means to defeat fungal epidemics on crop plants. However, the poor understanding of the molecular basis of hypovirulence induction limits their application. Using the devastating fungal pathogen on cereal crops, Fusarium graminearum, we identified an mRNA binding protein (named virus response 1, vr1) which is involved in symptom expression. Downregulation of vr1 in the virus-infected fungus and vr1 deletion evoke virus infection-like symptoms, while constitutive expression overrules the cytopathic effects of the virus infection. Intriguingly, the presence of a specific viral structural protein is sufficient to trigger the fungal response, i.e., vr1 downregulation, and symptom development similar to virus infection. The advancements in understanding fungal infection and response may aid biological pest control approaches using mycoviruses or viral proteins to prevent future Fusarium epidemics.

INTRODUCTION

Mycoviruses are ubiquitously found in all phyla of the true fungi (1). Very often, mycovirus infections remain symptomless (2), but some infections suppress asexual and sexual propagation, mycelial growth, and most notably, virulence, a phenomenon known as hypovirulence (3–5). Viruses that infect pathogenic fungi and thereby manipulate their pathogenic potential are a valuable tool in agronomics. The hypovirulence-related Cryphonectria hypovirus 1 (CHV1) has been applied for biological control of chestnut blight in Europe and the United States (6). White mold of rapeseed (Brassica napus) also was successfully constrained by use of a mycovirus (7).

The genetic and molecular mechanisms underlying fungal responses to viral infections, both symptomatic and asymptomatic, are widely unknown. Here, we investigate the virus infection response of the filamentous ascomycete Fusarium graminearum, the causal agent of fusarium head blight, a devastating disease of agriculturally important cereal crops in annual and worldwide epidemics. An F. graminearum infection results in a quantifiable crop yield reduction due to impaired development of kernels, as well as a qualitative reduction caused by fungal mycotoxins which poison the remaining kernels, threatening human and animal health if consumed (8). We recently described the infection of a Chinese isolate of F. graminearum (China 9) with FgV-ch9, a double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) chrysovirus-like mycovirus that slows down vegetative growth and causes significant reduction in virulence to wheat (9). The infecting virus consists of five dsRNA segments coding for the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase on segment 1 and two other structural proteins carried on segments 2 and 3, respectively. Two open reading frames on segment 4 and 5 encode nonstructural proteins with unknown functions (10, 11). Thus far, the mechanism by which the fungus gets debilitated is not known. Here, we describe a critical role of a putative poly(A)-binding protein (PABP), FGSG_05737 (here named vr1), which is an orthologue of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Nam8 and Aspergillus nidulans RrmA. The Schizosaccharomyces pombe Nam8 orthologue Csx1p was shown to regulate the expression of a large set of genes in response to oxidative stress, mainly by extending the half-life of the oxidative stress-responsive transcription factor Atf1 (12). In A. nidulans, RrmA regulates the turnover of transcripts involved in catabolism of nitrogen sources. Furthermore, RrmA is involved in translation initiation, arginine metabolism, and oxidative stress response (13). Hence, Csx1/RrmA-mediated mRNA stabilization covers several elementary physiological processes. In the present study, we, for the first time, implicate the F. graminearum Csx1/RrmA orthologue vr1 in the fungal response to a mycovirus infection. The expression level of vr1 is negatively affected by FgV-ch9 infection or in the presence of a viral structural protein and determines fungal fitness, as measured by vegetative growth, sporulation, and, most importantly, virulence. We propose a novel molecular determinant for symptom development in the virus-infected fungus linking hypovirulence to the presence of a viral structural protein and vr1 gene expression.

RESULTS

Infection of the F. graminearum reference strain PH1 with mycovirus FgV-ch9 causes hypovirulence.

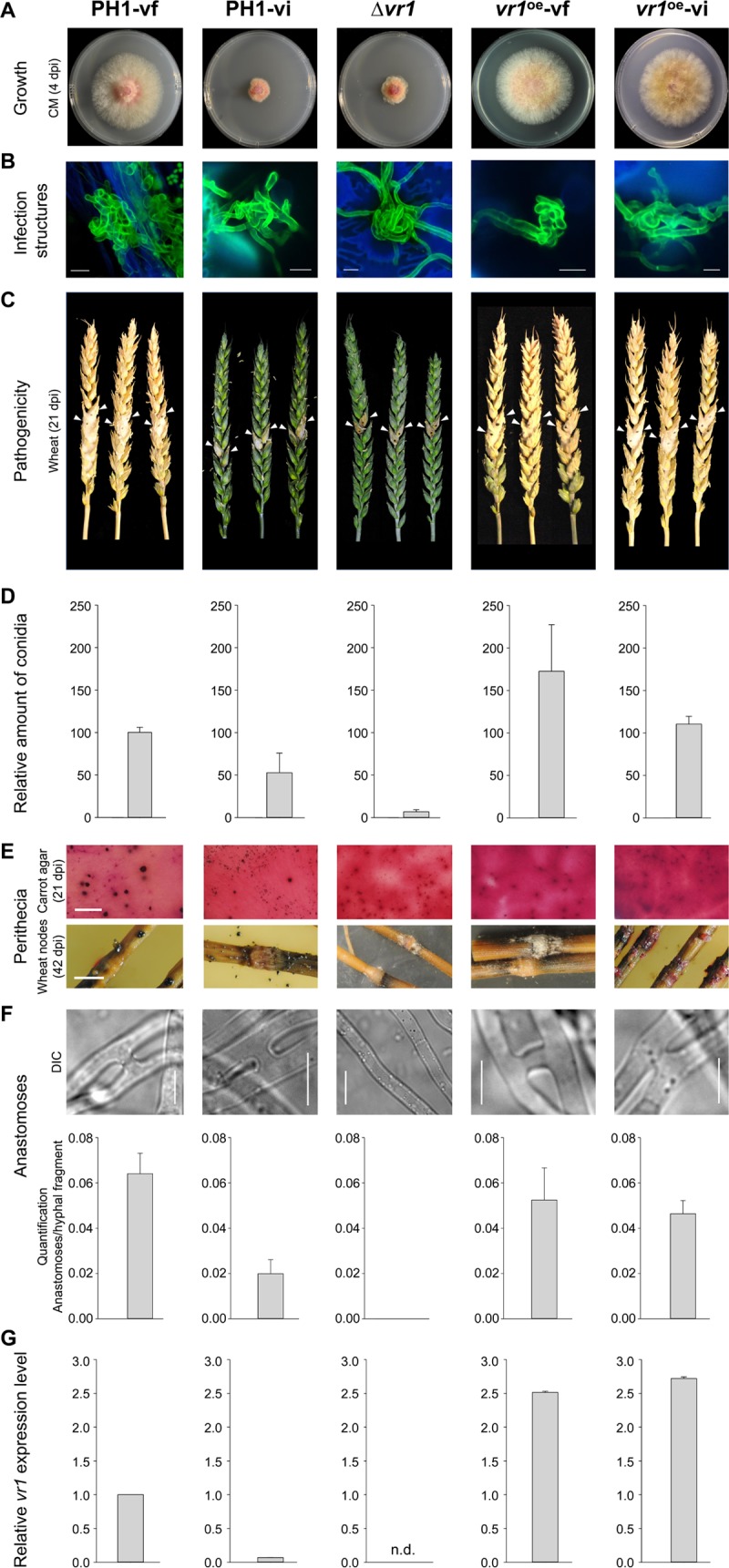

We succeeded in infecting the F. graminearum reference strain PH1 (14) with FgV-ch9 via hyphal fusion (anastomosis) (Fig. 1). The acceptor strain was separated from the donor strain, China 9, using a dominant selection marker (hygromycin resistance) introduced into PH1. Symptom development in PH1 was similar to that observed in the original Chinese isolate, i.e., virus-infected PH1 (PH1-vi) showed markedly reduced hyphal growth compared to virus-free PH1 (PH1-vf) (Fig. 2A). Fluorescence microscopy revealed that the development of infection cushions on wheat floral leaves was not affected, indicating that the initial infection is unchanged (Fig. 2B). However, in later stages virulence on wheat is drastically reduced in PH1-vi, and infection is restricted to the point-inoculated spikelet (Fig. 2C), unable to cross the rachis node for systemic infection. Virus presence in PH1 mycelia also reduced asexual sporulation to approximately 50% (Fig. 2D). Fruiting body formation still occurred, although ascospore-producing perithecia were significantly smaller in PH1-vi than in PH1-vf (Fig. 2E). Furthermore, the ability of PH1-vi mycelia to undergo anastomosis with themselves was reduced by approximately 70% compared to that of PH1-vf (Fig. 2F).

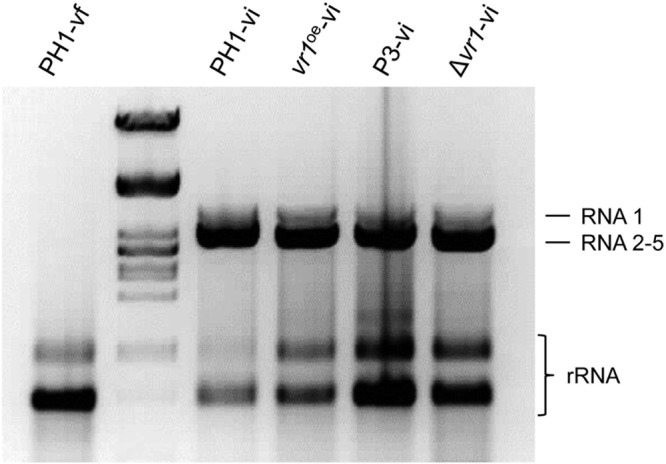

FIG 1.

Detection of viral dsRNA. Preparation of total RNA from mycelium of the virus-free wild type (PH1-vf), the virus-infected wild type (PH1-vi), a vr1 overexpression mutant (vr1oe-vi), a P3-expressing mutant (P3-vi), and a vr1 deletion strain (Δvr1-vi) grown in liquid complete medium for 3 days. Virus-infected strains harbor viral dsRNA at high molecular weight.

FIG 2.

FgV-ch9 and vr1-related phenotypes in Fusarium graminearum. The virus-free (PH1-vf) and virus-infected (PH1-vi) wild-type PH1, the vr1 deletion mutant (Δvr1), and the vr1 overexpression mutants (vr1oe-vf and vr1oe-vi) were tested for colony growth (3 dpi) (A), infection structure development (10 days on wheat glumes and stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate conjugated Triticum vulgare lectin [scale bar, 10 mm]) (B), virulence on wheat (21 dpi) (C), conidium production (D), perithecium formation (scale bar, 10 mm) (E), anastomosis formation (scale bar, 10 μm) (F), and relative vr1 gene expression (G). Virus infection triggers transcriptional downregulation of vr1 and causes phenotypes similar to those observed upon vr1 deletion. Overexpression of vr1 overrules the devastating effects of the virus infection, leading to a symptomless virus infection. The results for all strains are significantly different (P ≤ 0.05 by Student's t test) from those for the Δvr1 strain.

Constitutive overexpression of an mRNA-binding protein overrules virus-related symptoms.

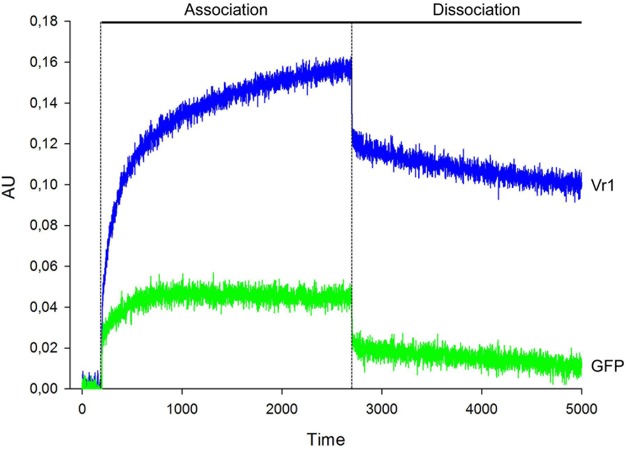

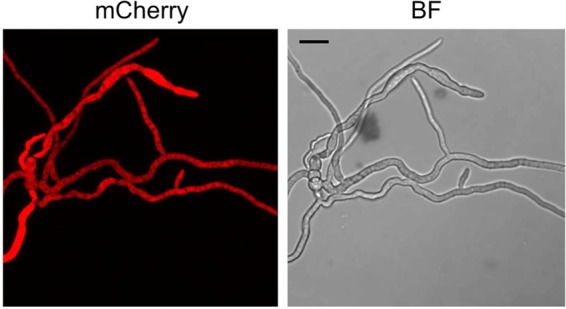

In the course of a candidate mutant screen approach within a custom-made mutant library, we identified a gene coding for a protein with three Nam8-like RNA recognition motifs (15) (FGSG_05737; NCBI accession number XP_011324319) as a host factor for the expression of virus infection-related symptoms. We named this gene virus response 1 (vr1). Fluorescence microscopy using mCherry-tagged Vr1 showed a cytoplasmic localization of the protein (Fig. 3). Biolayer interferometry (BLI) was performed to test whether purified Vr1 binds mRNA. Biotinylated fungal mRNA [enriched by poly(A)-oligo(dT)-based purification] was immobilized onto streptavidin-coated sensors, and binding to either polyhistidine-tagged Vr1 or GFP (expressed in Escherichia coli) was tested. The assay revealed that Vr1, but not GFP, can bind mRNA (Fig. 4). Therefore, we conclude that, in accordance to the bioinformatic predictions, Vr1 is an mRNA-binding protein. A genome database survey revealed that Vr1 is the only protein in F. graminearum containing three conserved Nam8-like RNA recognition motifs.

FIG 3.

Subcellular localization of vr1. The open reading frame of Vr1 was fused to the red fluorescent protein mCherry and expressed in mycelia of Fusarium graminearum. Fluorescence microscopy reveals an even distribution of Vr1 in the cytosol. Scale bar, 20 μm.

FIG 4.

Biolayer interferometry for binding affinities of purified, recombinant Vr1 and GFP to mRNA. Native, His6-tag-purified Vr1 and GFP were assayed for binding capacities for poly(A)-oligo(dT)-purified mRNA using biolayer interferometry. In the association phase, Vr1, but not GFP, strongly binds mRNA. The association is partially released in the dissociation phase. The measurement was repeated twice.

To test the importance of vr1 transcript level for symptom development, we first generated mutants in which vr1 expression is driven by the strong, constitutive gpdA promoter (16). Interestingly, vr1 overexpression (vr1oe) resulted in self-sterility and slightly reduced radial growth compared to that of PH1-vf (Fig. 2A and E). No other adverse phenotypes were observed in vr1oe-vf. Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) verified that gpdA promoter-driven vr1 expression in the vr1oe mutants was not affected by FgV-ch9 infection, with 2.5 (vr1oe-vf)- and 2.7 (vr1oe-vi)-fold higher expression levels of vr1 than that of PH1-vf and approximately 36- and 39-fold higher expression levels than that of PH1-vi, respectively (Fig. 2G). Strikingly, in the vr1oe mutants, virus infection did not cause symptoms with respect to vegetative growth (Fig. 2A), virulence (Fig. 2C), anastomosis formation (Fig. 2F), and asexual sporulation (Fig. 2D).

FgV-ch9 infection negatively affects vr1 mRNA level.

RNA interference-induced repression of vr1 transcripts (Table 1) and vr1 deletion impaired fungal growth. Furthermore, deletion of vr1 (Δvr1) strongly affected vegetative and sexual propagation, anastomosis formation, and virulence, similar to FgV-ch9 infection. Radial colony growth of the Δvr1 mutants was reduced by approximately 60% compared to that of PH1-vf and equal to that of PH1-vi (Fig. 2A). Asexual sporulation ceased almost completely. The Δvr1 mutants only released approximately 7% of the amount of conidia released by PH1-vf (Fig. 2D). In contrast to PH1-vi, Δvr1 mutants were sexually self-sterile and failed to form perithecia both on carrot agar and on wheat straw (Fig. 2E). The mutants were no longer able to form anastomosis (Fig. 2F), and virulence toward wheat was reduced to the same extent as that observed for PH1-vi (Fig. 2C), with no reduction in infection cushion development (Fig. 2B). We next tested whether mycovirus infection influences the vr1 gene expression level. qRT-PCR revealed a 15-fold drop of vr1 expression in PH1-vi compared to that in PH1-vf (Fig. 2G). Taken together, our results show that reduced vr1 expression causes virus infection-like symptoms, while elevated vr1 transcript levels render a virus infection symptomless.

TABLE 1.

Assay for vegetative growtha

| dsRNA | Growth (RFU) at: |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 h | 48 h | 72 h | 96 h | 170 h | |

| PVY | 3,308 (±6,544) | 4,998 (±4,509) | 17,478 (±2,949) | 81,097 (±28,598) | 93,001 (±27,500) |

| vr1 | 1,148 (±2,065) | 4,101 (±1,899) | 18,695 (±7,508) | 55,870 (±30,737) | 70,254 (±32,104) |

Vegetative growth was monitored by relative GFP fluorescence of PH1-GFP vf mutants in the presence of dsRNA targeted against vr1 and potato virus Y (PVY) as a control. dsRNA-mediated transcript repression of vr1, but not PVY, impaired fungal growth significantly (n = 30; P < 0.0001). RFU, relative fluorescence units.

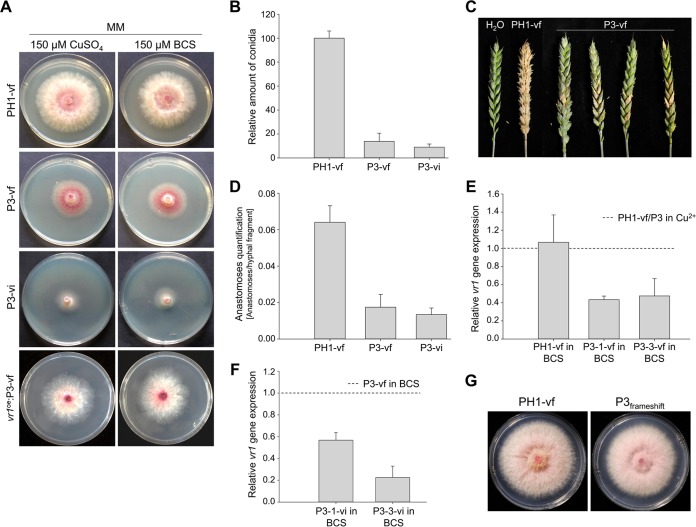

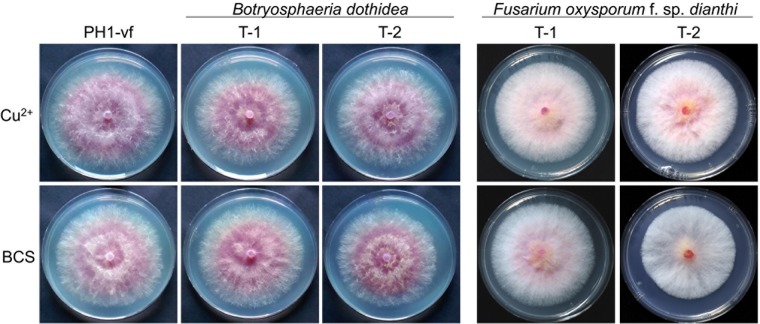

Heterologous expression of a viral structural protein elicits virus infection-like symptoms.

To test whether only the entire virus or also the expression of a viral protein could trigger vr1 downregulation and symptom development in F. graminearum, we heterologously expressed the FgV-ch9 structural protein P3. Several attempts to express the putative coat protein P3 constitutively in F. graminearum failed, suggesting that strong expression (gpdA promoter) impaired protoplast regeneration. Conditional expression using the copper-responsive tcu1 promoter, however, resulted in several mutants, all of which displayed disease-like symptoms similar to those of FgV-ch9 infection even under noninducing conditions in the presence of CuSO4 (Fig. 5; see also Data Set S1 in the supplemental material). Virus-free mutants expressing P3 (P3-vf) displayed reduction in growth (Fig. 5A), conidiation (Fig. 5B), virulence (Fig. 5C), and anastomosis formation (Fig. 5D), similar to PH1-vi and the Δvr1 mutants (Fig. 2). In accordance with the results with virus infection of PH1, induction of P3 expression between 2.7 (±0.2) and 13.4 (±1.7) by depletion of copper in the medium using the chelator bathocuproinedisulfonic acid disodium salt (BCS) (two independent mutants were tested) resulted in a 6-fold decrease in vr1 gene expression compared to that of PH1-vf (Fig. 5E). An additional virus infection of P3 mutants grown in medium containing BCS (P3-vi) (Fig. 1) further enhanced the downregulation by a factor between −1.8× and −4.4× compared to that of P3-vf in BCS (Fig. 5F) and further enhanced growth retardation (Fig. 5A). Hence, vr1 gene expression negatively correlates with the level of P3, indicating a quantitative effect. Accordingly, only minor symptoms could be observed when P3 was expressed in a vr1oe-vf background (Fig. 5A). The expression of a nontranslatable frameshift mutation introduced into the open reading frame (ORF) of P3 also did not evoke symptoms (Fig. 5G), indicating that the P3 protein rather than mRNA resulted in virus infection-like symptoms. Furthermore, the interaction is rather specific for P3 of FgV-ch9, since orthologues to P3 from related mycoviruses of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. dianthi (17) and Botryosphaeria dothidea (18) expressed in F. graminearum did not restrict mycelial growth (Fig. 6).

FIG 5.

Fusarium graminearum expressing the viral coat protein P3. (A) Colony morphology on minimal agar medium supplemented with CuSO4 for repression or bathocuproinedisulfonic acid disodium salt (BCS) for induction of P3 expression. Radial growth is reduced in the mutant expressing P3 (P3-vf) compared to that of the virus-free wild type (PH1-vf). Virus infection of P3 mutants enhances the phenotype. Constitutive expression of vr1 (vr1oe-vf) abolishes symptom development. (B) Conidium production assay. P3 expression and additional virus infection reduces the ability of the fungus to propagate vegetatively. (C) Virulence assay on wheat (21 dpi). The mutants expressing P3 are reduced in virulence compared to PH1-vf. (D) Assay for anastomosis formation. Expression of P3 and additional virus infection reduces the ability of F. graminearum to form anastomoses. (E and F) vr1 gene expression analysis. (E) Expression of P3 triggers the transcriptional downregulation of vr1 in 2 independent mutants (P3-1 and P3-3). Virus infection further enhances the downregulation of vr1. (G) Colony morphology on complete agar medium inoculated with PH1-vf and mutants expressing a P3 gene carrying a frameshift mutation. Expression of a nonsense transcript does not cause symptoms. Error bars indicate standard deviations. The dotted line refers to the respective reference conditions set to 1. The results for all strains are significantly different (P ≤ 0.05 by Student's t test) compared to those for PH1-vf and P3-vf, respectively.

FIG 6.

Heterologous expression of potential coat protein orthologues. The impact of the expression of potential coat proteins on vegetative growth on minimal medium (3 dpi) supplemented with 150 μM CuSO4 or 150 μM bathocuproinedisulfonic acid disodium salt (BCS) was assayed. None of the coat proteins showed adverse phenotypes compared to that of the wild type.

Taken together, these results show that downregulation of vr1 in response to virus infection and P3 expression is the main trigger for disease symptoms and that constitutive expression overrules the cytopathic effects of the virus infection.

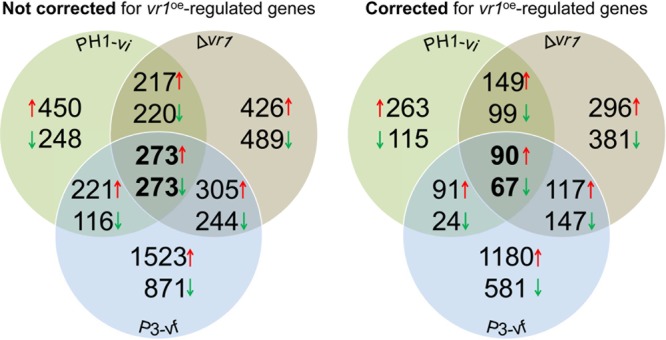

To identify specific genes affected in their expression and maybe contributing to symptom expression following virus infection, vr1 deletion, or P3 expression, comparative whole-transcriptome analysis using RNA sequencing was performed. All comparisons were performed against gene expression in PH1-vf. The comparative analysis revealed that virus infection of PH1, vr1 deletion, and P3 expression led to the significant upregulation of 1,161, 1,221, and 2,322 genes (considered differentially expressed genes, DEGs, when matching a log2 value of >2; adjusted P value [Padj] of <0.05), respectively. On the other hand, 857, 1,226, and 1,504 genes were found downregulated (log2 value of <−2; Padj value of <0.05) upon PH1 virus infection, vr1 deletion, and P3 expression, respectively (Fig. 7, Table 2, and Data Set S1). Between PH1-vi and Δvr1 strains, 217 and 220 genes were similarly up- and downregulated, respectively. Similarly, Δvr1 mutant and P3-vf expression shares a large number of concordantly regulated genes (305 upregulated and 244 downregulated). The same applies for the comparison between PH1-vi and P3-vf, in which 221 common genes were found upregulated and 116 downregulated in both samples. Overall, 273 genes, representing 16% of all DEGs, were concordantly upregulated and 273 genes downregulated in all three samples. Intriguingly, many fewer genes were found inversely regulated in the comparisons. Only 26 (PH1-vi against Δvr1 mutant), 72 (PH1-vi against P3-vf), and 57 (Δvr1 mutant against P3-vf) genes were inversely regulated (Table 2). This major transcriptional overlap supports the notion of a functional connection between vr1, P3 expression, and virus infection, and the large number of affected genes underscores the severity of physiological effects of the vr1-dependent host response. Moreover, the regulation pattern of certain genes may contribute to disease symptom development. To narrow down potential symptom determinants, we included RNA-seq data from the virus-tolerant vr1oe mutant (Fig. 7). This allowed us to exclude those genes from the analysis that are similarly regulated compared to PH1-vi, Δvr1 mutant, and P3-vf genes and, therefore, presumably do not contribute to symptom development. Gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of the group of 67 commonly downregulated genes that were not differentially regulated in the vr1oe-vi mutant revealed that global downregulation mostly affects signal transduction (GO:0007165). Accordingly, we found a total of 10 putative transcription factors downregulated in PH1-vi, P3-vi, and Δvr1 strains. Among them were three predicted top regulators (FGSG_00276, FGSG_00318, and FGSG_15877) according to Guo et al. (19) and two transcription factors (FGSG_00318 and FGSG_06542) that have an impact on sexual reproduction (20). Moreover, only one gene potentially involved in secondary metabolite biosynthesis (FGSG_03343, cluster K6) was downregulated. In contrast to that, PH1 virus infection, P3 expression, and vr1 deletion triggered the upregulation of a total of five potential cluster genes, among them FGSG_02324, encoding a signature gene of the aurofusarin biosynthesis cluster (21). GO annotation of upregulated genes showed an enrichment for metabolic processes (GO:0008152), oxidation-reduction processes (GO:0055114), and translation (GO:0006412). In total, three genes encoding protein kinases are significantly downregulated in PH1-vi, P3, and Δvr1 strains (FGSG_11812, FGSG_16828, and FGSG_05418). No gene encoding a protein kinase was found upregulated in the three samples.

FIG 7.

Venn diagram summarizing the global changes of transcription in F. graminearum due to virus infection (PH1-vi), vr1 deletion (Δvr1), and P3-expression (P3-vf). Transcriptomic profiling by RNA sequencing was performed using three biological replicates of each strain. Numbers represent genes that were significantly (Padj value of < 0.05) differentially (log2 >2, log2 <−2) regulated compared to PH1-vf.

TABLE 2.

Number of significantly differentially regulated genes in PH1-vi, Δvr1, and P3-vf strains compared to PH1-vf straina

| Strain | No. (%) of genes: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upregulated | Downregulated | Similarly regulated | Inversely regulated | |

| PH1-vi | 1,161 | 857 | 546 (9.2%) of 5,876 unique genes | 155 (2%) of 5,876 unique genes |

| Δvr1 | 1,221 | 1,226 | ||

| P3-vf | 2,322 | 1,504 | ||

Shown are the number of significantly differentially regulated genes (log2 values of <2, >2; Padj value of <0.05) in PH1-vi, Δvr1, and P3-vf strains compared to PH1-vf.

DISCUSSION

The Fusarium graminearum isolate China 9 harbors a chrysovirus-like dsRNA mycovirus. It is restricted in growth and hypovirulent on wheat and maize (9, 11). Using a hyphal anastomosis approach, we were able to infect the international F. graminearum reference strain PH1 (14) and convert this highly aggressive isolate to a hypovirulent one (PH1-vi). Similar to strain China 9, PH1-vi was restricted to the inoculated spikelet while PH1-vf infects wheat spikes systemically. Interestingly, this failure of systemic infection was not due to a reduction in the size and number of infection structures which are necessary for tissue penetration and invasion (22). The mitovirus Can-Bc-1, in contrast, negatively affects pseudoappressorium formation and reduces virulence of Botrytis cinerea (23). Given the fact that virus-infected F. graminearum is debilitated in essential aspects of the life cycle, first and foremost in growth vigor (Fig. 2), it seems likely that, due to the retarded growth, plant host defense responses are evoked and successfully defeat further infection. The rachis node of wheat is of central importance with respect to plant defense, as it represents a cell wall-associated physical barrier against fungal colonization (24, 25). The virus-infected fungi accordingly get stuck before entering the rachis node. The general fitness impairment of PH1-vi may also contribute to the reduced anastomosis formation and sporulation, both asexual and sexual. As yet, not much is known about the molecular trigger for anastomosis formation in F. graminearum. Hyphal fusions in general facilitate genetic exchange in a parasexual cycle and the exchange of nutrients and signals in a hyphal network (reviewed in reference 26). In F. graminearum, it was shown that growth retardation and defects in sensing environmental conditions affects anastomosis formation (22). Therefore, the observed reduction in hyphal fusion in PH1-vi, Δvr1, and the P3-expressing mutants may be linked to the impaired fitness but might also point to nutritional deficits in these strains. Interesting in this regard was finding the potential C6 transcriptional regulator FGSG_05958, the conserved hypothetical protein FGSG_10835 containing a WD40 domain, and the protein FGSG_04101, which is related to the mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase pathway-interacting protein Ubc2 downregulated in PH1-vi, Δvr1, and P3 mutants but not in the vr1oe-vi mutant. Orthologues of these genes were shown to be important for hyphal fusion in Neurospora crassa (L. Glass, personal communication). The formation of sexual organs and spores is affected by many environmental and genetic factors (27). Lin et al. (28) found that the size of perithecia in F. graminearum is regulated by the putative transcription factor MYT2. This gene (FGSG_07546) is not differentially regulated in FgV-ch9-infected mycelia (see Data Set S1 in the supplemental material). However, Son et al. (29) identified 51 transcription factors affecting sexual reproduction, and our transcriptomic approach revealed that the majority of them are downregulated upon FgV-ch9 infection (eight significantly downregulated compared to PH1-vf) (Data Set S1). Yu et al. (30) report that a reduction of conidiation is associated with the downregulation of the 3′-nucleotidase FgHal2 after infection with the hypovirus FgV1. In mycelia infected with FgV-ch9, however, FgHal2 (FGSG_09532) is not differentially regulated (Data Set S1), indicating that other factors influence conidiation in the FgV-ch9–F. graminearum interaction. Regarding the global transcription profile of FgV-ch9-infected PH1 (Fig. 7, Table 2, and Data Set S1), it is noteworthy that a large subset of genes is upregulated upon virus infection, contradicting the possibility of a general transcriptional shutoff as, for example, observed for influenza virus infecting human cell lines (31). The transcriptomic profiling of PH1-vi revealed a significant upregulation of approximately 8.4% of all predicted ORFs of F. graminearum, while only approximately 6.2% of all genes were downregulated and 85.4% were not significantly affected compared to PH1-vf. Hence, a transcriptional shutoff mediated by the virus does not occur. This is in accordance with the situation in F. graminearum mycelia infected with hypovirus FgV1-DK21, where the majority of genes were not affected, and among the regulated genes a nearly equal number of genes were found up- and downregulated due to virus infection (32). A proteomic approach revealed that protein synthesis, signal transduction, differentiation and biogenesis of cellular components, and defense response proteins are differentially expressed in F. graminearum upon FgV-DK21 infection. Several proteins with implications in fungal vigor and general fitness were detected to be downregulated (33). One of the genes transcriptionally downregulated in FgV-ch9-infected mycelium is vr1. Poly(A)-binding proteins like Vr1 are involved in the initiation of mRNA translation, which represents a common target of various viruses (34). Efficient mRNA translation in eukaryotes involves the formation of a loop structure in which the 5′ cap and the 3′ poly(A) tail of any mRNA are brought together. This mechanism depends on PABPs like Vr1 (35). Virus-induced host gene shutoff (VGS) is a general phenomenon encountered in many animal and plant hosts during virus replication (36). VGS can affect several steps in host gene expression, i.e., transcription initiation or protein maturation (reviewed in reference 34). A prevalent target for VGS is the inhibition of cap-dependent translation, since many viruses express their genes in a cap-independent manner (reviewed in reference 36). Translation of FgV-ch9 mRNA does not rely on PABPs due to a missing poly(A) tail. Therefore, FgV-ch9 can also replicate in the Δvr1 mutant (Fig. 1). Excess PABP capacities in the vr1oe strains results in sufficient translational capacities for both viral and host protein biosynthesis. Along these lines, the overexpression of vr1 efficiently counteracts the cytopathic effects of the virus infection. The observed sexual sterility of the vr1oe mutants is interesting in this regard. This observation provides a coherent explanation in terms of fungal evolution as to why vr1 expression is not permanently elevated. Perithecium formation is mandatory for sexual reproduction in the life cycle of F. graminearum (37), and ascospores start the infection cycle in the fields. A constitutive overexpression of vr1 would, therefore, render F. graminearum apathogenic. To a lesser extent than that of vr1, the constitutive overexpression of the transcription factor swi6 also attenuates symptoms due to an FgV1 infection (38). Hence, swi6, similar to vr1, might also represent a host factor that influences symptom development. However, it cannot be ruled out that swi6 overexpression results in a general fitness benefit leading to a slightly increased growth rate after virus infection. Given the asymptomatic growth, virulence, and sporulation in the vr1oe strains in the presence of FgV-ch9, it appears that vr1 is a specific host symptom alleviation factor. The Woronin-body protein Hex1, in contrast, is a host factor affecting fusarivirus V1 dsRNA accumulation in infected mycelia of F. graminearum in an expression level-dependent manner (39).

For several plant-virus interactions, the persistence of unknown virus-derived products rather than active viral replication causes symptoms (40). Our results related to P3 expression and vr1 overexpression suggest a similar situation in the FgV-ch9-F. graminearum interaction. The symptomless virus replication and P3 expression in the vr1oe mutant demonstrates that virus-induced phenotypes are caused by neither a posttranscriptional block of the host's translational machinery nor by RNA interference (RNAi)-related defense responses as deployed by, e.g., Cryphonectria parasitica infected with hypovirus (summarized in reference 41). This is in agreement with previous results, demonstrating that the RNAi machinery is not involved in growth, abiotic stress response, and pathogenesis in F. graminearum under tested conditions (42). Interestingly, vr1 transcript levels are also downregulated in the P3-expressing mutant that shows a virus infection-like phenotype. P3 expression in the vr1oe background only shows strongly attenuated symptoms. A viral polyprotein of the hypovirus CHV1-EP713 was shown to influence virus replication and vertical transmission in C. parasitica (43). The results related to the fungal response to P3 expression in F. graminearum also indicate that not virus replication itself but rather the presence of a viral protein causes symptoms. The facts that growth of P3-expressing mutants is further reduced after an additional virus infection and that it was impossible to generate mutants with a constantly high expression of P3 point to a quantitative effect of P3 expression on the observed phenotypes. Since the nontranslatable frameshift mutation in the ORF of P3 did not cause symptoms, it can be ruled out that the P3-mRNA contributes to the vr1-related host reaction. However, the intricate nature of P3-host interaction remains elusive. It appears that the F. graminearum-P3 interaction is rather specific with respect to P3 of FgV-ch9, since structural proteins of related mycoviruses of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. dianthi (17) and Botryosphaeria dothidea (18) expressed in F. graminearum did not cause disease symptoms. The presence of P3 of FgV-ch9 may act as an elicitor to prompt innate host responses, including vr1 downregulation, resulting in the impairment of general fungal fitness as measured by growth vigor, reproductive capacities, and, most importantly, pathogenic potential. An alternative hypothesis for vr1 regulation and symptom development would be that the virus (or viral proteins like P3) target vr1 transcripts. Therefore, virus infection and P3-mediated vr1 downregulation could diminish host translation and cause depletion of essential enzymes.

A single gene product found to be responsible for a cytopathic effect has also been described for the virus causing Sindbis fever in humans (44). Heterologous expression of Sindbis virus protein nsP2, like P3, also a coat protein, is cytotoxic and causes transcription inhibition. A similar result was obtained by Urayama et al. (45), who observed a cytopathic effect when they overexpressed the structural protein P4 of Magnaporthe oryzae chrysovirus 1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. While MoCV1 P4 and FgV-ch9 P3 are only distantly related on the protein sequence level, they both seem to be structural proteins and are therefore functional orthologues, as they both exert cytopathic effects (46, 47).

Taken together, we identified vr1 as a key host factor for the expression of virus-related disease symptoms. The elucidation of vr1 regulation in response to viral proteins helps to understand the molecular basis of hypovirulence. The findings may also contribute to future pest control strategies. With deeper knowledge about fungal host responses, mycoviruses or viral proteins may become applicable as potent biological pest control agents against Fusarium infections on diverse cereal crops.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fungal strains and culture conditions.

All strains described in this study (Table 3) originate from the F. graminearum wild-type strain PH1. For vector cloning, Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain FGSC 9721 (FY 834; uracil auxotroph; ura3) was used. Plasmids were amplified using Escherichia coli strain DH5α. Bacteria were cultivated in sterile lysogeny broth (LB) medium either as a liquid culture or on agar plates and then supplemented with 100 μg ml−1 ampicillin or 50 μg ml−1 kanamycin. Yeast cells were cultured in yeast extract-peptone-glycerol (YPG) and in SD medium lacking uracil.

TABLE 3.

Fusarium graminearum strains used in this study

| Strain | Characteristic(s) |

|---|---|

| PH1-vf | Fusarium graminearum, virus free |

| PH1-vi | F. graminearum, virus infected |

| Δvr1-vf | Deletion mutant of FGSG_05737 (vr1) |

| Δvr1-vi | Deletion mutant of vr1, virus infected |

| vr1oe-vf | Constitutive expression of vr1 in PH1, virus free |

| vr1oe-vi | Constitutive expression of vr1 in PH1, virus infected |

| PH1:P3-vf | Weak expression of viral coat protein P3 in PH1, virus free |

| PH1:P3-vi | Weak expression of viral coat protein P3 in PH1, virus infected |

| vr1oe:P3-vf | Weak expression of viral coat protein P3 in the vr1oe mutant, virus free |

Conidiation of F. graminearum was induced in liquid wheat medium (15 g wheat leafs, shredded and autoclaved in 1 liter H2O) incubated for 7 days at 28°C. Sexual reproduction was monitored on carrot agar plates and detached wheat nodes placed on water agar as described previously (48). For growth assays, mycelial plugs of all strains were taken from the edge of a 3-day-old colony on complete medium (CM) (29) and placed in the middle of the assay plates. All plates were incubated at 28°C for at least 3 days in the dark. Anastomosis formation was assayed using objective slides covered with a thin layer of carrot agar spot inoculated with 1,000 conidia of F. graminearum and incubated at 28°C in the dark for 24 h. Virus infection was accomplished by coinoculation of a donor and an acceptor strain carrying a dominant selection marker (resistance to antibiotics) on CM-agar plates. At 5 days postinfection (dpi), the acceptor strain was recovered and separated from the donor strain using selective pressure mediated by an appropriate antibiotic over at least three passages. Successful virus transfer was assayed using total RNA extraction as outlined below, and the genetic background of the strain was confirmed by PCR amplifying the respective resistance gene. Phenotypic characterizations were conducted using at least three independent biological replicates and, whenever possible, several independent mutants or strains, as indicated in the figure legends.

Vector construction.

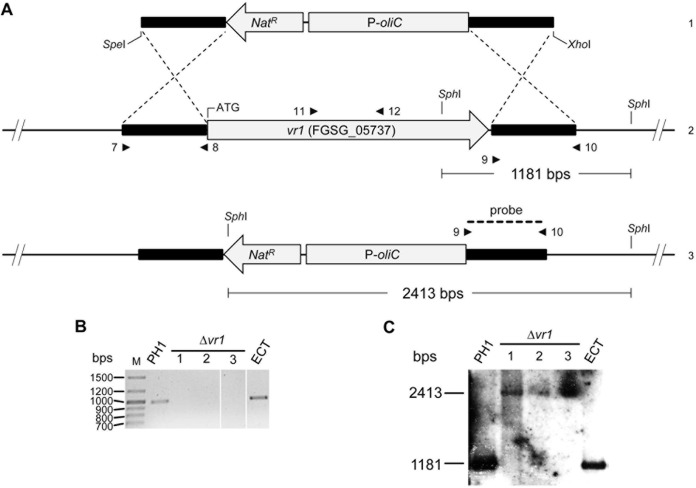

Fusarium graminearum vr1 (FGSG_05737) was deleted using a double homologous recombination approach. For vector construction, flanking regions (1,075 bp upstream and 1,047 bp downstream of vr1) were amplified by PCR from genomic DNA (gDNA) using primers 7 and 8 (left flank) and 9 and 10 (right flank), respectively. Primer sequences are listed in Table 4. The PCR was initiated by denaturation at 94°C for 4 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 45 s, 55°C for 45 s, and 68°C for 60 s. The PCR included a final extension step at 68°C for 10 min and a cooling step at 4°C. For the replacement construct, the gene flanks and a cassette comprising the gene encoding a nourseothricin (nat) resistance cassette, together with the linearized pRS426 plasmid comprising an ampicillin resistance marker and a gene facilitating uracil biosynthesis, were cotransformed into the uracil-auxotrophic yeast strain FGSC 9721 (FY 834). Overhangs identical to adjacent fragments facilitate fusion of all fragments to give rise to a circular plasmid, named pRS426:deltavr1, that confers prototrophy. Positive clones were selected and checked by PCR. Plasmids were isolated from PCR-positive clones and transformed into E. coli. The replacement construct was released from pRS426:deltavr1 by restriction with SpeI and XhoI and used for fungal transformation. For generation of overexpression mutants, the entire ORF of FGSG_05737 was amplified by PCR using primers 13 and 14 (Table 4), ligated into pGEM-T vector (Promega Corp., Madison, WI), sequenced, and restricted using BamHI restriction sites introduced into the primers. The BamHI-released fragment was then ligated into the BamHI-linearized vector p7_GluA containing the constitutive promoter of the glycerinaldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (gpdA) from Aspergillus nidulans, thereby generating plasmid p7GluA:vr1oe. This plasmid was inserted into the genome of F. graminearum by single crossover after linearization using AhdI. Successful integration and, therefore, overexpression of vr1 was verified by qRT-PCR using gene-specific primers 33 and 34 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). For generation of a plasmid carrying a C-terminal fusion of FGSG_05737 with the red fluorescent protein mCherry (pRS426:vr1-mCherry), the entire ORF of FGSG_05737 together with 1,384 bp of upstream sequence (fragment 1; primer 53 and 54) (Table 4), a cassette consisting of a poly-GA-linker and the mCherry-ORF (fragment 2; primer 55 and 56) (Table 4), and a 927-bp fragment of the 3′-untranslated region (UTR) of FGSG_05737 (fragment 3, primer 57 and 58) (Table 4) were amplified by PCR and used for yeast transformation as described above, together with a HYG cassette released from pan7-1 using restriction enzymes HindIII, PciI, BamHI, and BglII. Fragments 1 and 3 contained overhangs introduced into the primers that facilitate homologous recombination with adjacent fragments. The fragment for transformation was released by restriction of pRS426:vr1-mCherry with BamHI and KpnI.

TABLE 4.

Primers used in this study

| Name | Sequencea |

|---|---|

| 1 | GATTTGGATCCATGGCATCG |

| 2 | TTTAAGCTTTAACGTCGACGG |

| 3 | GGCGGCTTAATTAAATGGCATCGAACGCATTGTTCGAC |

| 4 | GGCGGCGGCGGATCCTTAACGTCGACGGTTCACGGTC |

| 5 | TATGCTATACGAAGTTATGCGGCCGCAATTCCGACTCGGTTGG |

| 6 | CCTTGCTCACCATGTTAATTAAGGTGATTTTGCTGATGAATATGTCTG |

| 7 | CCCGAATCGGGAATGCGGCTCTAGAGTAGAAAGCTGCACGCAGTAATATG |

| 8 | GCTCTAGAACTAGTGGATCCCCCGGGCCTGATCCCCATCAGCCTCGAAAC |

| 9 | GGCCCCCCCTCGAGGTCGACGGTCTCGATGGTGTGAAGGTACGGTACGTA |

| 10 | ACATGAGCATGCCCTGCCCCTGAGCGGCCATGATGAGCTTTACGAAAGT |

| 11 | GATCTGGCCCCGACTCTCC |

| 12 | GGTAGCCCTGCATCTGGTT |

| 13 | GGATCCATGAACCCTGGTTTCTCTGGTG |

| 14 | GGATCCATACTCCTAATTTGTCAGTACG |

| 15 | GCTATGTCATCTACCGTGTC |

| 16 | GGTTGATCCAGTAAGAGTTGAG |

| 17 | GGCCCCCCCTCGAGGTCGACGGTATCGATATTGATACGTGGATCTTGTAT |

| 18 | GGTGAACAGTCCCTCGCCCTTGCTCACCATATCCATGATGAGCTTTACGA |

| 19 | CTGGGATCCATGGTGAGCAAGGGCGAGGA |

| 20 | ACGCGGAGCTGAAGGAGTCGGGTCGTAAGATGGAGGAGGCGGAGGAGGAGGAGGGTATGAGTCCACCATCGAAGGCTTGTACAGCTCGTCCATGCCGTGAGTGA |

| 21 | CCTTCGATGGTGGACTCATACCCTCCTCCTCCTCCGCCTCCTCCATCTTACGACCCGACTCCTTCAGCTCCGCGTTAAGGCCGCTCAGGGGCAGGGCATGCTCATGC |

| 22 | GCTCTAGAACTAGTGGATCCCCCGGGCTGTAGAGCCGCATTCCCGATTCG |

| 25 | TGTCGACGACCAGTTCTCAGC |

| 26 | CGATGTCGGCGTCTTGGTAT |

| 27 | CTTCACTACACGCATCTACC |

| 28 | GACAGAAGAACTTTAGAGATGG |

| 29 | GGTGAACTTCAAGATCCGCC |

| 30 | GTGCTCAGGTAGTGGTTGTC |

| 31 | TCAACTTCGGAGGCAATCAC |

| 32 | GTTCACGGTCTTCTCAAACAC |

| 33 | GGCTACCCTATCGGTAACTC |

| 34 | TTAATACTCCTGAGGAGGGC |

| 35 | GCCCTCTAGATAACTTCGTATAATGTATG |

| 36 | CCAACCGAGTCGGAATTGCGGCCGCATAACTTCGTATAGCATA |

| 37 | CAGACATATTCATCAGCAAAATCACCTTAATTAACATGGTGAGCAAGG |

| 38 | CCTTGCTCACCATGTTAATTAAGGTGATTTTGCTGATGAATATGTCTG |

| 39 | TGCAGCGCAACCTGGCCA |

| 40 | ATGATGATGATGATGGTGCATGTATATCTCCTTC |

| 41 | ATGTCGACATTTTCAGCATCTTACAGTG |

| 42 | GTGCGCCTCGAGGCGCATCATGTTAG |

| 43 | GGATCCATGTCAGGACAATTGAACATTC |

| 44 | AAGCTTTTCCGAACCAAAACAC |

| 45 | TGCAACACCATGGCAACC |

| 46 | CTAGCTCGAGGTCTTTGCTGGC |

| 47 | TTCCCCGGGATGTATTCG |

| 48 | TGTTGTGTCCGGCAGTATG |

| 49 | ACTAGTCGGGATAGTTCCGACCTAG |

| 50 | CTCGAGTTATATAGATGTTCAGCTATGC |

| 51 | GTTAGCAGTACTATCTCAGTGG |

| 52 | AGTACTTTAAGAAGGAGATATAC |

| 53 | GGCCCCCCCTCGAGGTGACGGTATCGATGGACGCTGGATCTCAAACCTT |

| 54 | CCGGCTCCAGCGCCTGCACCAGCTCCATACTCCTAATTTGTCAGTACGTC |

| 55 | GGAGCTGGTGCAGGCGCTGGAGCCGGTGCCATGGTGAGCAAGGGCGAGGA |

| 56 | GAGGGCAAAGGAATAGAGTAGATGCCGTTACTTGTACAGCTCGTCCATGC |

| 57 | GCTTCCAAGCGGAGCAGGCTCGACGTTATTACAAAGCTGCACGCAGTAATA |

| 58 | GCTCTAGAACTAGTGGATCCCCCGGGCTGATCGCGGAGAAGCAAATTACG |

| 59 | AAGTGGGCCCAGATCATGACC |

| 60 | ATGCCCCTGCAGTGAGGAG |

| 61 | TGAGGATCCTGGTGYATHGARAAYGG |

| 62 | GCGGGATCC(T)17 |

Underlined sequences are restriction enzyme recognition sites.

For heterologous expression of FgV-ch9-ORF3 (P3) and P3 orthologues from other mycoviruses in F. graminearum, a versatile vector backbone was generated. Initially, three fragments were amplified by PCR from their respective sources. The FgTcu-1 promoter (1,500 bp upstream of ORF FGSG_06061) was amplified from F. graminearum gDNA using primers 5 and 6 (Table 4). The hph gene conferring resistance to hygromycin was amplified from pPP68 with primers 25 and 26 (Table 4). The mCherry gene coding for a fluorescent tag protein was amplified from pPP81 using primers 27 and 28 (Table 4). The resulting three fragments, hph (1.4 kb), FgTcu-1 promoter (1.8 kb), and mCherry (1 kb), had overlapping regions due to the construction of the primers used for their amplification and were subsequently ligated together and amplified by PCR to create a 3.74-kb fragment. This fragment was cut with BamHI and XbaI and ligated into pZErO-2 (Clontech/TaKaRa Bio USA, Mountain View, CA) that was digested with the same enzymes, giving rise to plasmid pBJ-1. The ORF of P3 was amplified from cDNA with primers 3 and 4 (Table 4). The ORFs encoding coat proteins of related mycoviruses (Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. dianthi mycovirus 1 [YP_009158915.1] and Botryosphaeria dothidea chrysovirus [AJD14831.1]) were synthesized (General Biosystems, Morrisville, NC). The mCherry ORF was released from pBJ-1 by PacI/NotI digestion. Similarly, the PCR product of FgV-ch9-P3 and the synthesized genes were digested using PacI/NotI restriction sites introduced into the termini of the sequences and subsequently ligated into pBJ-1. The resulting plasmids were used for transformation of the fungus after linearization with the restriction enzyme XbaI.

A nontranslatable frameshift mutation (deletion of the A in the translation start site) was introduced into pBJ-P3 by site-directed mutagenesis by following the manufacturer's instructions (Q5 site-directed mutagenesis kit; New England BioLabs) using primers 29 and 30 (Table 4).

For heterologous expression of enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) and Vr1 in E. coli, both ORFs were amplified from cDNA using primers 59 and 60 (Vr1) and 61 and 62 (GFP), respectively. Both fragments were cloned into pQE30 (Qiagen) using BamHI and HindIII restriction sites introduced into the primers.

Transformation of F. graminearum.

A solution of 30 to 50 μl containing approximately 10 μg DNA was used for protoplast transformation of F. graminearum. The protoplast transformation method was performed as described previously (48). Briefly, YEPD medium (100 ml of 0.3% yeast extract, 1% Bacto peptone, 2% d-glucose) was inoculated with 1 × 106 conidia and incubated overnight at 28°C and 150 rpm. The mycelia were collected by filtering with a 200-μm-diameter sieve and washed with double-distilled water, resuspended in a 20-ml mixture of Driselase and lysing enzymes (2.5%; 0.5% in 0.6 M KCl; Life Technologies, Darmstadt, Germany), and incubated for 2 to 3 h at 30°C and 80 rpm. Undigested hyphal material was removed from the protoplast suspension by filtration. The protoplasts were pelleted by centrifugation at 670 × g, washed once with 10 ml STC (20% sucrose, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 50 mM CaCl2), centrifuged again, and then resuspended and adjusted in STC at 1 × 108 protoplasts per ml. For transformation, 200 μl of the protoplast suspension was mixed with DNA. The samples were incubated at room temperature for 20 min. Subsequently, 1 ml PEG (40% polyethylene glycol 4000, 60% STC) was added and again incubated at room temperature for 20 min. The protoplast suspension was added to 5 ml TB3 medium (100 g sucrose, 0.3% yeast extract, 0.3% Casamino Acids) and shaken overnight at room temperature and 100 rpm for cell wall regeneration. The regenerated protoplasts were pelleted by centrifugation at 4,200 × g and then mixed with TB3 agar (1.5%). The mixture was then plated out on petri dishes (10 ml/plate). After 24 h, an overlay comprised of water agar (1.5%) and 500 μg ml−1 hygromycin B or 200 μg ml−1 nourseothricin was added to the plates. Putative transformants were obtained after 2 dpi at 28°C. They were transferred to fresh plates of CM supplemented with 250 μg/ml hygromycin B or 100 μg ml−1 nourseothricin and incubated at 28°C. All transformants were purified by single-spore isolation and subsequently checked by diagnostic PCR (Fig. 8 and data not shown). Gene deletion was accomplished by double homologous recombination using gene-homologous flanks enclosing a resistance cassette. In two separate transformation events, a total of three homokaryotic deletion mutants (Δvr1) were generated (verified by PCR using primers 11 and 12 and Southern blot analysis) (Fig. 8 and Table 4).

FIG 8.

Gene replacement, Southern hybridization, and diagnostic PCRs for vr1 deletion. (A) Replacement and Southern hybridization strategy for vr1. Deletion of vr1 (2) by homologous recombination using a replacement fragment excised from pRS426:deltavr1 using restriction enzyme SpeI and XhoI (1) (3, genotype of disrupted strains). Flanking regions are indicated as boldface black lines. The gene flanks were fused to a nourseothricin (nat) resistance cassette, consisting of the nat acetyltransferase gene fused to the A. nidulans oliC promoter (P-oliC). Primer binding sites for PCR are indicated as small arrows (numbering refers to that in Table 4). The region used as probe for Southern analysis is represented by the dashed line. Scheme not to scale. (B) PCR analysis of three independent Δvr1 strains, one ectopic mutant, and the wild type. Deletion of vr1 was verified in the Δvr1 mutants (analyzed after single-spore purification) using primers 11 and 12. The wild type and the ectopic strain (ECT) were PCR positive for the gene internal fragment (987 bp). (C) Southern analysis of Δvr1 and the wild type. DNA of the mutants and wild-type strain was digested using SphI, separated on agarose gels, blotted on membranes, and probed with a DIG-labeled probe for a fragment of the flanking region of vr1. The probe hybridized with the DNA of the disruption mutants (2,413 bp) and the wild type (1,181 bp).

Southern blot analysis.

For Southern hybridization analysis to verify gene deletion, approximately 3 μg of gDNA of the wild type, the vr1 (FGSG_05737) deletion strains, and the ectopic mutant strains were restricted with SphI overnight. The digested DNA was then separated on 0.8% agarose gels by electrophoresis at 70 V for 6 to 7 h. The DNA was transferred by capillary blotting onto Hybond NX membranes (GE Healthcare, Munich, Germany) and then hybridized with DIG (digoxigenin)-labeled (Roche, Penzberg, Germany) DNA probe amplified from the right flank of the deletion construct using primers 9 and 10 (Fig. 8 and Table 4). Detection and visualization procedures were carried out by following the manufacturer's manual (Roche, Penzberg, Germany).

RNAi experiments.

A 600-bp fragment of vr1 and an 800-bp fragment from potato virus Y (PVY; genus Potyvirus, family Potyviridae) were amplified with primers 59 and 60 (vr1) and 61 and 62 (PVY) (Table 4) by PCR. Both fragments were cloned into SmaI-linearized plasmid L4440 (plasmid 1654; Addgene). dsRNA was in vitro transcribed from PvuI-linearized constructs using T7 polymerase (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. For gene silencing, 50 nM dsRNA was incubated with 100 conidia of a GFP-expressing F. graminearum mutant in 100 μl liquid CM in a black 96-well plate at 28°C. Relative fluorescence levels were determined in a Mithras2 LB 943 multimode reader (Berthold Technologies, Bad Wildbad, Germany). GFP fluorescence was excited at 495/10 nm and recorded at 520/25 nm.

Virulence assays on wheat.

The susceptible spring wheat cultivar Nandu (Lochow-Petkus, Bergen-Wohlde, Germany) was used for wheat virulence assays. Plants were cultivated in a growth chamber at 20°C with a photoperiod of 16 h and 60% relative humidity and then transferred to infection chambers under optimized conditions. A suspension of 500 conidia of each strain in 10 μl for each sample was inoculated into each of two central spikelets at the early stages of anthesis. The inoculated spikes were enclosed in small plastic bags misted with water for the first 3 days and then monitored for up to 3 weeks in the infection chambers. Wheat spikes inoculated with 10 μl water were used as the negative control. Wheat infection assays were performed using at least two independent mutant strains and repeated 30 times for each strain.

In vitro infection assays were performed on wheat paleas as described previously (22, 49). Paleas were dissected from wheat florets and washed in 0.01% (vol/vol) Tween 20. Subsequently, paleas were washed twice with distilled water, placed on water agar, and inoculated with 5 μl of conidia suspension (20 conidia μl−1) of all strains (at least two independent mutants and five replicates). Water agar plates were sealed and incubated at 20°C with a photoperiod of 16 h. Microscopic screening for infection structure development was started 6 dpi. Epiphytic hyphae were fluorescently labeled using CF488A wheat germ agglutinin (Biotium, Hayward, CA).

Nucleic acid extraction and expression analysis by quantitative real-time PCR and RNA sequencing.

For virus identification, total RNA was extracted according to a previously published protocol (50). For expression analysis, RNAs from fungal mycelia were isolated using TriFast (Peqlab, Erlangen, Germany). For this, mycelia were grown for 3 days in liquid CM. Prior to RNA isolation, the samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen and freeze-dried overnight. For RT-PCR, SuperScript II RNase H− reverse transcriptase (Thermo Scientific, Schwerte, Germany) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. The resulting cDNA was later used as a template for quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) reactions. Transcript levels of the target genes were normalized against tubulin and ubiquitin gene expression. The qRT-PCRs were carried out using gene-specific primers (tubulin, 15 and 16; ubiquitin, 17 and 18; GFP, 19 and 20; P3, 21 and 22; vr1, 23 and 24) (Table 4), with LightCycler 480 SYBR green I master mix (Roche) in a volume of 20 μl in a LightCycler 480 (Roche). The PCR program was incubation for 2 min at 50°C, 2 min at 95°C, up to 40 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 55 to 58°C for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 15 s, followed by a melting curve analysis to check the specificity of fragment amplification. All measurements were repeated twice with three replicates each, using at least two independent mutants. Relative changes in gene expression were calculated using the comparative crossing point (Cp) method using REST software (51). RNA sequencing was performed as follows. Illumina libraries from RNA were generated using a NEBNext Ultra whole-transcriptome shotgun sequencing (RNA-seq) kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. A total of 1 μg total RNA quantified by Qubit (Invitrogen) after DNase treatment was subjected to mRNA isolation followed by size fragmentation. The RNA fragments were reverse transcribed and double-stranded DNA was generated. DNA fragment ends were adenylated prior to adaptor ligation and PCR amplification (15 cycles). Fragment length distribution of all libraries was analyzed on a 2100 Agilent Bioanalyzer high-sensitivity DNA chip. Diluted libraries (2 nM) were multiplex sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq 2500 instrument (50-bp single-end run, 30 to 40 million reads/sample). The genome and annotation of F. graminearum (version 3.2) was retrieved from the Munich Information Center for Protein Sequences (52). RNA-seq reads were aligned using STAR (v2.4.2a). The option –quantMode GeneCounts was applied to estimate the count of reads per gene simultaneously. Based on these counts, statistical analysis of differential expression was carried out with DESeq2 (v1.13.3). Genes with a minimum of 2-fold and significant (Padj value of <0.05) increase or decrease in expression between the two strains were considered differentially regulated. Gene ontology enrichment analysis was performed using the QuickGO browser at https://www.ebi.ac.uk/QuickGO/ (53).

BLI.

Biolayer interferometry (BLI) is a label-free technology to measure biomolecular interaction and binding events by measuring interference patterns of white light reflected from sensor surfaces. To test the mRNA-binding capacities of Vr1 and GFP, total RNA was extracted as described above and enriched for mRNA using poly(A)-oligo(dT)-based purification according to the manufacturer's guidelines (GeneRead pure mRNA kit; Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Subsequently, the mRNA was biotinylated using a Pierce RNA 3′-end biotinylation kit (ThermoFisher Scientific). Recombinant Vr1 and GFP were purified from E. coli using the nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) purification system (Life Technologies, Darmstadt, Germany) by following the protocol for native protein purification. Briefly, E. coli clones expressing His6-tag fusions with Vr1 and GFP were incubated overnight at 37°C and 200 rpm in 5 ml of LB medium containing ampicillin (100 μg ml−1). One milliliter of the overnight culture was used to inoculate 50 ml LB-Amp in a 250-ml Erlenmeyer flask. When reaching an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.6, 0.4 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added and further incubated at 37°C, 200 rpm, for approximately 4 h. Harvest and lysis of cells and affinity purification was done by following the instructions described in the manual (Ni-NTA purification system). Successful purification was checked by SDS-PAGE (data not shown). BLI was performed using Octet RED96 (Pall FortéBio, Fremont, CA) using streptavidin-coated biosensors that are loaded with biotinylated mRNA. Protein samples were diluted in kinetics buffer (Pall FortéBio) to a final concentration of 100 μg ml−1. The kinetic protein binding method was programmed as two mRNA-loaded biosensors moved in parallel to 1× kinetics buffer wells to equilibrate to the system and then were shifted to wells containing either Vr1 or GFP (association). After 10 min, the biosensors were moved to wells containing 1× kinetics buffer to monitor the dissociation of the protein from the mRNA. The whole experiment was repeated twice.

Microscopy.

Infection cushions stained with CF488A wheat germ agglutinin and vr1-mCherry were visualized using a Zeiss LSM 780 microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). Fluorescence of mCherry was excited at 561 nm, and the fluorescence was detected at 570 to 640 nm. Fluorescence of CF488A was excited at 488 nm and detected in the 520- to 631-nm range using a W Plan-Apochromat 40×, 1.0 differential interference contrast microscopy M27 objective. Average-intensity projections were generated from up to 60 separate images using CEN software (Zeiss). Anastomoses were visualized by bright-field microscopy using a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope equipped with a PlanApo VC 60×, 1.40-numerical-aperture objective with oil immersion.

Accession number(s).

All data are available at NCBI under BioProject code PRJNA416261.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Lanelle R. Connolly and Steven Friedman for critical readings of the manuscript, Cathrin Kröger, Birgit Hadeler, Lisa Fuhrmann, and Karen Van Zee for technical assistance, and Rodrigo Duarte Gonçalves for his help with protein purification. The plasmid carrying a cassette consisting of a poly-GA-linker and the mCherry-ORF was obtained from A. L. Martínez Rocha, University Hamburg, Germany. Plasmids pPP68 and pPP81 were obtained from Pallavi A. Phatale, Oregon State University (Corvallis, OR, USA).

The project was partially funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (BO 4098/3-1, Scha 559/6-1).

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.00326-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ghabrial SA, Caston JR, Jiang D, Nibert ML, Suzuki N. 2015. 50-Plus years of fungal viruses. Virology 479–480:356–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buck KW. 1998. Molecular variability of viruses of fungi, p 53–72. In Bridge P, Couteaudier Y, Clarkson J (ed), Molecular variability of fungal pathogens. Springer Science & Business Media, Berlin, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghabrial SA, Suzuki N. 2009. Viruses of plant pathogenic fungi. Annu Rev Phytopathol 47:353–384. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-080508-081932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nuss D. 2011. Mycoviruses, p 145–152. In Borkovich K, Ebbole D (ed), Cellular and molecular biology of filamentous fungi. ASM Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pearson MN, Beever RE, Boine B, Arthur K. 2009. Mycoviruses of filamentous fungi and their relevance to plant pathology. Mol Plant Pathol 10:115–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2008.00503.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Milgroom MG, Cortesi P. 2004. Biological control of chestnut blight with hypovirulence: a critical analysis. Annu Rev Phytopathol 42:311–338. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.42.040803.140325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu X, Li B, Fu Y, Xie J, Cheng J, Ghabrial SA, Li G, Yi X, Jiang D. 2013. Extracellular transmission of a DNA mycovirus and its use as a natural fungicide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:1452–1457. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213755110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goswami RS, Kistler HC. 2004. Heading for disaster: Fusarium graminearum on cereal crops. Mol Plant Pathol 5:515–525. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2004.00252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Darissa O, Adam G, Schäfer W. 2012. A dsRNA mycovirus causes hypovirulence of Fusarium graminearum to wheat and maize. Eur J Plant Pathol 134:181–189. doi: 10.1007/s10658-012-9977-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blum C, Götsch S, Heinze C. 2017. Duplications in the 3′ termini of three segments of Fusarium graminearum virus China 9. Arch Virol 162:897–900. doi: 10.1007/s00705-016-3174-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Darissa O, Willingmann P, Schäfer W, Adam G. 2011. A novel double-stranded RNA mycovirus from Fusarium graminearum: nucleic acid sequence and genomic structure. Arch Virol 156:647–658. doi: 10.1007/s00705-010-0904-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rodriguez-Gabriel MA, Burns G, McDonald WH, Martin V, Yates JR III, Bahler J, Russell P. 2003. RNA-binding protein Csx1 mediates global control of gene expression in response to oxidative stress. EMBO J 22:6256–6266. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krol K, Morozov IY, Jones MG, Wyszomirski T, Weglenski P, Dzikowska A, Caddick MX. 2013. RrmA regulates the stability of specific transcripts in response to both nitrogen source and oxidative stress. Mol Microbiol 89:975–988. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trail F, Common R. 2000. Perithecial development by Gibberella zeae: a light microscopy study. Mycologia 92:130–138. doi: 10.2307/3761457. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ekwall K, Kermorgant M, Dujardin G, Groudinsky O, Slonimski PP. 1992. The NAM8 gene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae encodes a protein with putative RNA binding motifs and acts as a suppressor of mitochondrial splicing deficiencies when overexpressed. Mol Gen Genet 233:136–144. doi: 10.1007/BF00587571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meyer V, Wanka F, van Gent J, Arentshorst M, van den Hondel CA, Ram AF. 2011. Fungal gene expression on demand: an inducible, tunable, and metabolism-independent expression system for Aspergillus niger. Appl Environ Microbiol 77:2975–2983. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02740-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lemus-Minor CG, Canizares MC, Garcia-Pedrajas MD, Perez-Artes E. 2015. Complete genome sequence of a novel dsRNA mycovirus isolated from the phytopathogenic fungus Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. dianthi. Arch Virol 160:2375–2379. doi: 10.1007/s00705-015-2509-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang L, Jiang J, Wang Y, Hong N, Zhang F, Xu W, Wang G. 2014. Hypovirulence of the phytopathogenic fungus Botryosphaeria dothidea: association with a coinfecting chrysovirus and a partitivirus. J Virol 88:7517–7527. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00538-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guo L, Zhao G, Xu JR, Kistler HC, Gao L, Ma LJ. 2016. Compartmentalized gene regulatory network of the pathogenic fungus Fusarium graminearum. New Phytol 211:527–541. doi: 10.1111/nph.13912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Son H, Seo YS, Min K, Park AR, Lee J, Jin JM, Lin Y, Cao P, Hong SY, Kim EK, Lee SH, Cho A, Lee S, Kim MG, Kim Y, Kim JE, Kim JC, Choi GJ, Yun SH, Lim JY, Kim M, Lee YH, Choi YD, Lee YW. 2011. A phenome-based functional analysis of transcription factors in the cereal head blight fungus, Fusarium graminearum. PLoS Pathog 7:e1002310. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sieber CM, Lee W, Wong P, Munsterkotter M, Mewes HW, Schmeitzl C, Varga E, Berthiller F, Adam G, Guldener U. 2014. The Fusarium graminearum genome reveals more secondary metabolite gene clusters and hints of horizontal gene transfer. PLoS One 9:e110311. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bormann J, Boenisch MJ, Brückner E, Firat D, Schäfer W. 2014. The adenylyl cyclase plays a regulatory role in the morphogenetic switch from vegetative to pathogenic lifestyle of Fusarium graminearum on wheat. PLoS One 9:e91135. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang L, De Wu M, Li GQ, Jiang DH, Huang HC. 2010. Effect of Mitovirus infection on formation of infection cushions and virulence of Botrytis cinerea. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol 75:71–80. doi: 10.1016/j.pmpp.2010.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blümke A, Falter C, Herrfurth C, Sode B, Bode R, Schäfer W, Feussner I, Voigt CA. 2014. Secreted fungal effector lipase releases free fatty acids to inhibit innate immunity-related callose formation during wheat head infection. Plant Physiol 165:346–358. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.236737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jansen C, Von Wettstein D, Schäfer W, Kogel K-H, Felk A, Maier FJ. 2005. Infection patterns in barley and wheat spikes inoculated with wild-type and trichodiene synthase gene disrupted Fusarium graminearum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:16892–16897. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508467102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Glass NL, Kaneko I. 2003. Fatal attraction: nonself recognition and heterokaryon incompatibility in filamentous fungi. Eukaryot Cell 2:1–8. doi: 10.1128/EC.2.1.1-8.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dyer PS, Ingram DS, Johnstone K. 1992. The control of sexual morphogenesis in the ascomycota. Biol Rev 67:421–458. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin Y, Son H, Min K, Lee J, Choi GJ, Kim JC, Lee YW. 2012. A putative transcription factor MYT2 regulates perithecium size in the ascomycete Gibberella zeae. PLoS One 7:e37859. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leach J, Lang BR, Yoder OC. 1982. Methods for selection of mutants and in vitro culture of Cochliobolus heterostrophus. Microbiology 128:1719–1729. doi: 10.1099/00221287-128-8-1719. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu J, Lee KM, Son M, Kim KH. 2015. Effects of the deletion and over-expression of Fusarium graminearum gene FgHal2 on host response to mycovirus Fusarium graminearum virus 1. Mol Plant Pathol 16:641–652. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vreede FT, Fodor E. 2010. The role of the influenza virus RNA polymerase in host shut-off. Virulence 1:436–439. doi: 10.4161/viru.1.5.12967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee KM, Cho WK, Yu J, Son M, Choi H, Min K, Lee YW, Kim KH. 2014. A comparison of transcriptional patterns and mycological phenotypes following infection of Fusarium graminearum by four mycoviruses. PLoS One 9:e100989. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kwon SJ, Cho SY, Lee KM, Yu J, Son M, Kim KH. 2009. Proteomic analysis of fungal host factors differentially expressed by Fusarium graminearum infected with Fusarium graminearum virus-DK21. Virus Res 144:96–106. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aranda M, Maule A. 1998. Virus-induced host gene shutoff in animals and plants. Virology 243:261–267. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wells SE, Hillner PE, Vale RD, Sachs AB. 1998. Circularization of mRNA by eukaryotic translation initiation factors. Mol Cell 2:135–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Walsh D, Mohr I. 2011. Viral subversion of the host protein synthesis machinery. Nat Rev Microbiol 9:860–875. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hallen HE, Huebner M, Shiu SH, Güldener U, Trail F. 2007. Gene expression shifts during perithecium development in Gibberella zeae (anamorph Fusarium graminearum), with particular emphasis on ion transport proteins. Fungal Genet Biol 44:1146–1156. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Son M, Lee Y, Kim KH. 2016. The transcription cofactor Swi6 of the Fusarium graminearum is involved in fusarium graminearum virus 1 infection-induced phenotypic alterations. Plant Pathol J 32:281–289. doi: 10.5423/PPJ.OA.12.2015.0267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Son M, Lee K-M, Yu J, Kang M, Park JM, Kwon S-J, Kim K-H. 2013. The HEX1 gene of Fusarium graminearum is required for fungal asexual reproduction and pathogenesis and for efficient viral RNA accumulation of Fusarium graminearum virus 1. J Virol 87:10356–10367. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01026-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Havelda Z, Varallyay E, Valoczi A, Burgyan J. 2008. Plant virus infection-induced persistent host gene downregulation in systemically infected leaves. Plant J 55:278–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dawe AL, Nuss DL. 2013. Hypovirus molecular biology: from Koch's postulates to host self-recognition genes that restrict virus transmission. Adv Virus Res 86:109–147. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394315-6.00005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen Y, Gao Q, Huang M, Liu Y, Liu Z, Liu X, Ma Z. 2015. Characterization of RNA silencing components in the plant pathogenic fungus Fusarium graminearum. Sci Rep 5:12500. doi: 10.1038/srep12500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Suzuki N, Maruyama K, Moriyama M, Nuss DL. 2003. Hypovirus papain-like protease p29 functions in trans to enhance viral double-stranded RNA accumulation and vertical transmission. J Virol 77:11697–11707. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.21.11697-11707.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Garmashova N, Gorchakov R, Frolova E, Frolov I. 2006. Sindbis virus nonstructural protein nsP2 is cytotoxic and inhibits cellular transcription. J Virol 80:5686–5696. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02739-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Urayama S, Ohta T, Onozuka N, Sakoda H, Fukuhara T, Arie T, Teraoka T, Moriyama H. 2012. Characterization of Magnaporthe oryzae chrysovirus 1 structural proteins and their expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Virol 86:8287–8295. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00871-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Urayama S-I, Kimura Y, Katoh Y, Ohta T, Onozuka N, Fukuhara T, Arie T, Teraoka T, Komatsu K, Moriyama H. 2016. Suppressive effects of mycoviral proteins encoded by Magnaporthe oryzae chrysovirus 1 strain A on conidial germination of the rice blast fungus. Virus Res 223:10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2016.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Urayama S, Fukuhara T, Moriyama H, Toh-E A, Kawamoto S. 2014. Heterologous expression of a gene of Magnaporthe oryzae chrysovirus 1 strain A disrupts growth of the human pathogenic fungus Cryptococcus neoformans. Microbiol Immunol 58:294–302. doi: 10.1111/1348-0421.12148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nguyen VT, Kröger C, Bönnighausen J, Schäfer W, Bormann J. 2013. The ATF/CREB transcription factor Atf1 is essential for full virulence, deoxynivalenol production and stress tolerance in the cereal pathogen Fusarium graminearum. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 26:1378–1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Boenisch MJ, Schäfer W. 2011. Fusarium graminearum forms mycotoxin producing infection structures on wheat. BMC Plant Biol 11:110. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-11-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rott ME, Jelkmann W. 2001. Characterization and detection of several filamentous viruses of cherry: adaptation of an alternative cloning method (DOP-PCR), and modification of an RNA extraction protocol. Eur J Plant Pathol 107:411–420. doi: 10.1023/A:1011264400482. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pfaffl MW, Horgan GW, Dempfle L. 2002. Relative expression software tool (REST) for group-wise comparison and statistical analysis of relative expression results in real-time PCR. Nucleic Acids Res 30:e36. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.9.e36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wong P, Walter M, Lee W, Mannhaupt G, Munsterkotter M, Mewes HW, Adam G, Guldener U. 2011. FGDB: revisiting the genome annotation of the plant pathogen Fusarium graminearum. Nucleic Acids Res 39:D637–D639. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Binns D, Dimmer E, Huntley R, Barrell D, O'Donovan C, Apweiler R. 2009. QuickGO: a web-based tool for Gene Ontology searching. Bioinformatics 25:3045–3046. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.