Abstract

Introduction

The effectiveness of inhaled therapies can be influenced by many factors, including the type of inhaler, which may have clinical implications. We report a real-world, multicenter, open-label, non-randomized, non-interventional study conducted by 200 pulmonologists across 200 centers in Hungary. The effectiveness of budesonide/formoterol inhalation therapy in daily clinical practice, delivered via the Bufomix Easyhaler®, was evaluated in patients with asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma-COPD overlap (ACO).

Methods

Effectiveness was assessed after 12 weeks of treatment by spirometry, the Asthma Control Test, mini-Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire, COPD Assessment Test and modified Medical Research Council dyspnea scale. Patient satisfaction with the Bufomix Easyhaler® and physicians’ assessments (ease of use and time taken to learn the technique) were also assessed.

Results

A total of 1498 patients with obstructive airway disease were evaluated (asthma: n = 621; COPD: n = 778; ACO: n = 99), of whom 455 (30.4%) were newly diagnosed inhaler-naïve patients and 1043 (69.6%) were switching from other inhalers. Significant improvements in lung function, disease control and health-related quality of life measures (all p ≤ 0.002) were reported after 12 weeks of Bufomix Easyhaler® use. Improvements were observed in both inhaler-naïve patients and those who switched to a Bufomix Easyhaler® from other devices. After switching, 72.4% of patients regarded the Bufomix Easyhaler® as ‘very good’ and > 90.0% of physicians described the Bufomix Easyhaler® as easy to teach; 73.8% and 98.9% of patients learned the technique within 5 and 10 min of teaching, respectively.

Conclusion

Twelve weeks’ treatment with the Bufomix Easyhaler® resulted in significant improvements in disease control and quality of life. The Bufomix Easyhaler® was considered easy to use, and most patients were satisfied with the inhaler. Results confirm the real-world effectiveness of the Bufomix Easyhaler® in the treatment of adult outpatients with obstructive airway disease.

Funding

Orion Corp., Orion Pharma.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s12325-018-0753-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Asthma, ACO, Budesonide/formoterol Easyhaler®, COPD, Effectiveness, Real-world study, Respiratory/pulmonary

Introduction

Asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are highly prevalent chronic respiratory diseases and leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide [1]. Asthma-COPD overlap (ACO) is a challenging phenotype of obstructive airway disease where patients have clinical features of both asthma and COPD [2, 3]. Despite the presence of established treatment guidelines for asthma [2], many asthma patients still experience persistent symptoms and therefore poor disease control [4, 5]. Recent data indicate that improvement of asthma control continues to be a public health concern in the USA and Europe, as asthma is not well controlled or managed on national levels [6, 7]. Furthermore, most patients with COPD are symptomatic [8], despite the available therapies, such as bronchodilators and inhaled corticosteroids (ICS).

Inhaled therapy is recommended as the primary route of administration for medication used to manage asthma [9] and COPD [10]. An additive effect in alleviating asthma symptoms has been demonstrated with combination therapy of budesonide (an ICS) and formoterol fumarate [a long-acting β2-adrenergic agonist (LABA)] (budesonide/formoterol) [11]. Budesonide/formoterol is also a recommended treatment alternative for patients with COPD who have a history of exacerbations [12]. In patients with ACO, treatment with low-to-moderate-dose ICS is recommended with the addition of a LABA and/or long-acting muscarinic receptor antagonists where necessary [2].

Many types of devices for delivery of inhaled drugs are available [13]. Effectiveness of the inhaler is crucial since a suboptimal inhalation technique may have clinical implications [14]; effectiveness can be influenced by several factors, including age, gender, education, inhalation technique and type of inhaler used [15, 16].

The Bufomix Easyhaler® (Orion Pharma, Espoo, Finland) is a multidose dry powder inhaler for the administration of budesonide/formoterol in combination, indicated for the treatment of adult patients with COPD and asthma, and adolescents (aged 12–17 years) with asthma [17], approved in several European countries. The Bufomix Easyhaler® has demonstrated similar in vitro flow rate dependency compared with the Turbuhaler®, using clinically relevant air flow rates collected from patients with asthma and COPD [18]. Additionally, superior dose consistency was observed compared with the Turbuhaler® at different clinically relevant in vitro flow rates [19]. Therapeutic equivalence and equivalent bronchodilator efficacy have also been reported between the two inhalers [20, 21].

Recent real-world evidence, collected in patients with asthma, has demonstrated the clinical effectiveness of the Bufomix Easyhaler® [22]; however, patient satisfaction with the Bufomix Easyhaler® is yet to be evaluated further. The aim of this non-randomized, open-label, real-world study was to evaluate the effectiveness of Bufomix Easyhaler® therapy for asthma, COPD and ACO in everyday clinical practice in Hungary.

Methods

Study Design

This real-world, multicenter, open-label, non-randomized, non-interventional study was conducted by 200 pulmonologists across 200 Hungarian centers and was a nationwide assessment of inhaler effectiveness in patients diagnosed with asthma, COPD and ACO who started using the Bufomix Easyhaler®, including those who switched from their current inhaler. The trial was registered with the National Pharmaceutical Institute of Hungary (registration no. OGYÉI/13,942-5/2016). Test devices were distributed from Orion Pharma to participating centers prior to the start of the study, which was conducted between 1 May 2016 and 31 December 2017. Patients made three visits to their pulmonologist; all measurements were evaluated as change from baseline (visit 1, when patients switched from their current inhaler to Bufomix Easyhaler®) to visit 3 (after 12 weeks’ treatment with Bufomix Easyhaler®). The dose and dosing regimen were agreed between the patient and their pulmonologist at the first visit. The following doses (μg/inhalation of budesonide/formoterol) were used, according to the Bufomix Easyhaler summary of product characteristics (SPC) [23, 24]: 160/4.5 in patients with asthma receiving 2 × 1 inhalations per day or patients with COPD receiving 2 × 2 inhalations per day; 320/9 in patients with asthma receiving 2 × 1 or 2 × 2 inhalations per day or patients with COPD receiving 2 × 2 inhalations per day. Patients with ACO were treated in accordance with Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) guidelines [2]. The daily dose, per patient, was the same across the whole study period.

Demographic data, spirometry, current medication and smoking history were recorded using asthma and COPD assessment forms, completed during each visit by recruiting physicians (see supplementary material).

Patients

Patients were identified based on their attendance at routine clinical appointments at widespread centers in Hungary that met Good Clinical Practice requirements. Eligible patients were adults (> 18 years old) with a physician-led diagnosis of asthma or COPD (according to GINA or Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease therapeutic guidelines [2, 10]) or ACO (also according to GINA guidelines) and without an exacerbation in the 4 weeks prior to enrollment. Additionally, patients whose disease could not be controlled with pre-existing therapy, whose proficiency in the usage of the previously prescribed inhaler was unsatisfactory, or who did not feel comfortable with their device, were also eligible for this study. Patients were excluded from the study if they had a hypersensitivity to budesonide, formoterol or lactose or if they were pregnant or breastfeeding [16]. The study was approved by the National Scientific and Research Ethics Committee of Hungary.

All procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the National Scientific and Research Ethics Committee of Hungary (the study was approved by this body) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study prior to study commencement.

End Points and Assessments

Primary outcomes were change in patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures after 12 weeks of treatment; PRO measures were assessed using the following co-primary end points: the Asthma Control Test (ACT) [25], mini-Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (mini AQLQ) [26], COPD Assessment Test (CAT) [27] and modified Medical Research Council dyspnea scale (mMRC) [28]. All other outcomes were assessed as secondary end points.

Disease control was assessed during each visit using either the ACT (ACT score ≤ 19 indicates poorly or not well controlled asthma) or the CAT (CAT score of > 20 indicates a high impact of COPD on their daily life); health-related quality of life (HRQoL) measures were assessed using the mini-AQLQ (mini-AQLQ score < 4 indicates very limited daily life due to asthma) and the mMRC (mMRC score > 1 indicates difficulty in walking due to breathlessness).

To evaluate the usage of a previous inhaler (if it existed) and the Bufomix Easyhaler® in everyday life, patients received a previously validated questionnaire (e.g., how easy was it to learn, use, clean and inhale from the inhaler, how much the inhaler use helped in everyday activities such as sports, walking, etc., and patients’ perception/preference for their inhaler) [29]. This self-assessment was completed during all visits (Table 1). Additionally, patient satisfaction using a previous inhaler (if it existed) or the Bufomix Easyhaler® was analyzed at visit one using closed questions scored on a six-point scale: one (very good) to six (unsatisfactory). Before the start of the study, participating pulmonologists were trained in how to use the Bufomix Easyhaler® by Orion Pharma staff; physicians then showed individual patients how to handle the device at the first visit, according to the SPC [23, 24]. After training the patient in using the Bufomix Easyhaler®, physicians were asked to assess the ease of use (through visits 1–3) and the time taken to teach the patient how to use the device (at visit 1) (Table S1). For patients whose disease could not be controlled with pre-existing therapy, or whose proficiency in the usage of their previous inhaler was unsatisfactory, pulmonologists assessed the use of the previous device by asking the same questions provided for the Bufomix Easyhaler®.

Table 1.

Patient assessment of the inhaler and complexity of the instructions for use

| Question | Please select most appropriate |

|---|---|

| Patient perspective on Easyhaler® use | |

| How easy was it to learn how to use the inhaler? | 1 (very easy)–6 (difficult) |

| How easy was it to prepare the inhaler? | 1 (very easy)–6 (difficult) |

| How easy was it to use the inhaler? | 1 (very easy)–6 (difficult) |

| How easy was it to successfully inhale from the inhaler? | 1 (very easy)–6 (difficult) |

| How easy was it to keep the inhaler clean and ready-to-use? | 1 (very easy)–6 (difficult) |

| How easy are daily activities (e.g., sports, walking) with the inhaler? | 1 (very easy)–6 (difficult) |

| How easy was it to handle the inhaler (according to the size and weight of the inhaler)? | 1 (very easy)–6 (difficult) |

| Do you feel any discomfort related to the following when using the inhaler? | |

| Smell | Yes/no |

| Taste | |

| Coughing | |

| Huskiness | |

| Other | |

| How would you evaluate the inhaler in general? | 1 (very good)–6 (not good) |

Forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) was determined using spirometry through visits 1–3 (measured as a pre-bronchodilator assessment), according to the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society task force guidelines [30, 31] and expressed as FEV1% predicted normal.

Statistical Analyses

All data were expressed as percentages or means with standard deviations. The Wilcoxon’s signed rank test was used to compare change from baseline; p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. No power calculations were performed because of the real-world nature of the study.

All questionnaires were provided in e-format case report forms (CRFs) by VIT Ltd., Hungary; scores were input into these CRFs by the pulmonologist at each visit after they read each question to the patient.

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS® software, version 9.4 for Windows (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Baseline Patient Characteristics

Overall, 1498 patients with obstructive airway disease were evaluated (asthma: n = 621; COPD: n = 778; ACO: n = 99). Baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 2. Patients with asthma were younger, with a mean age of 53.2 years [standard deviation (SD), 16.3], than those with COPD (mean age 64.1 years; SD, 9.9) and ACO (mean age 61.9 years; SD 10.6). Overall, patients had a mean FEV1 % predicted of 62.2% (21.8). The majority of patients were female (60.4%), had a smoking history (59.0%) and were educated up to high school (88.9%).

Table 2.

Baseline demographics and patient characteristics (N = 1498)

| Asthma (n = 621) | ACO (n = 99) | COPD (n = 778) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 53.2 (16.3) | 61.9 (10.6) | 64.1 (9.9) |

| Gender (female), n (%)a | 430 (69.4) | 60 (61.2) | 413 (53.2) |

| Height (cm), mean | 165.5 | 167.1 | 165.0 |

| Weight (kg), mean | 78.1 | 77.3 | 75.7 |

| FEV1% predicted | 76.7 (19.3) | 56.7 (18.3) | 51.3 (17.0) |

| Education, n (%)a | |||

| Primary school | 156 (25.2) | 43 (43.9) | 381 (49.1) |

| High school | 359 (58.1) | 49 (50.0) | 343 (44.2) |

| University or college degree | 103 (16.7) | 6 (6.1) | 52 (6.7) |

| Disease control, mean (SD) | |||

| ACT | 14.2 (4.1) | 13.6 (4.1) | n/a |

| CAT | n/a | 23.7 (6.5) | 24.2 (5.7) |

| HRQoL | |||

| Mini-AQLQ | 3.8 (0.9) | 3.7 (0.9) | n/a |

| mMRC dyspnea scale | n/a | 1.8 (0.9) | 1.9 (0.9) |

| Smoking status, n (%) | |||

| Current | 88 (14.2) | 35 (35.4) | 368 (47.3) |

| Former | 87 (14.0) | 37 (37.4) | 268 (34.4) |

| Never | 446 (71.8) | 27 (27.3) | 141 (18.1) |

ACO asthma-COPD overlap, ACT asthma control test, AQLQ asthma quality of life questionnaire, CAT COPD assessment test, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, FEV1 forced expiratory volume in 1 s, mMRC modified Medical Research Council, n/a not applicable, SD standard deviation

aPatients with missing data were excluded from percentage calculations

At baseline (visit 1), 455 (30.4%) patients were new to inhaler use, and 1043 (69.6%) patients switched to the Bufomix Easyhaler® from other inhalers. The three most commonly used inhalers were the Metered Dose Inhaler (MDI), Turbuhaler® and Diskus® (Fig. S1). At baseline, most of the 1498 participants had poorly controlled asthma or experienced a high impact of COPD on their daily life. Accordingly, 398 (64.1%) patients with asthma, 563 (72.4%) patients with COPD and 82 (82.8%) patients with ACO were using a maintenance medication at baseline.

Effect of Bufomix Easyhaler® on Disease Control

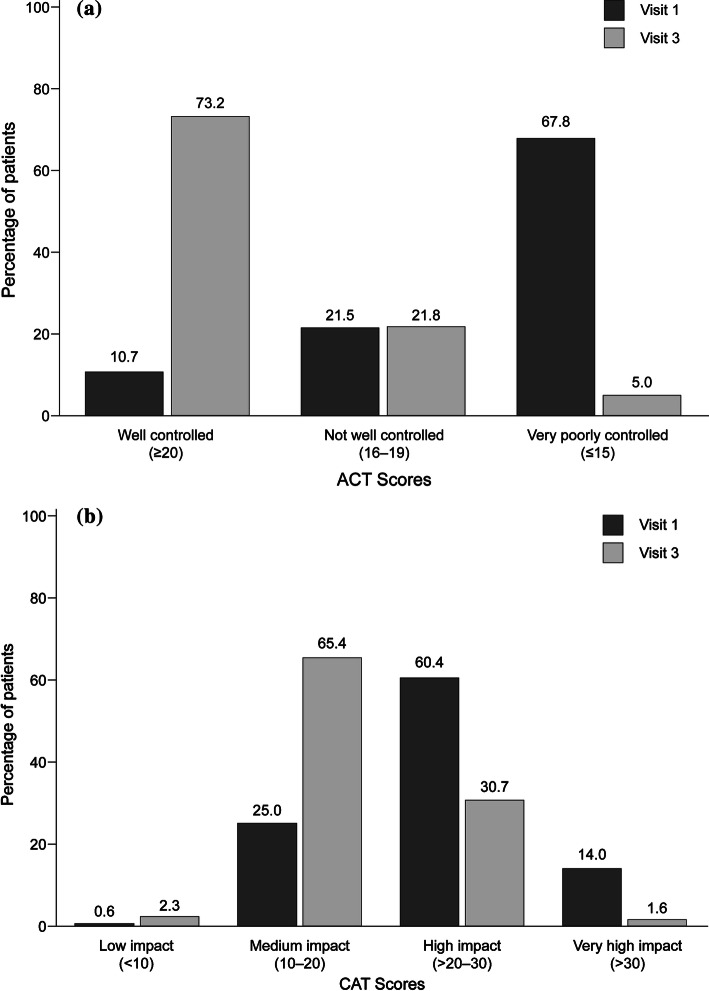

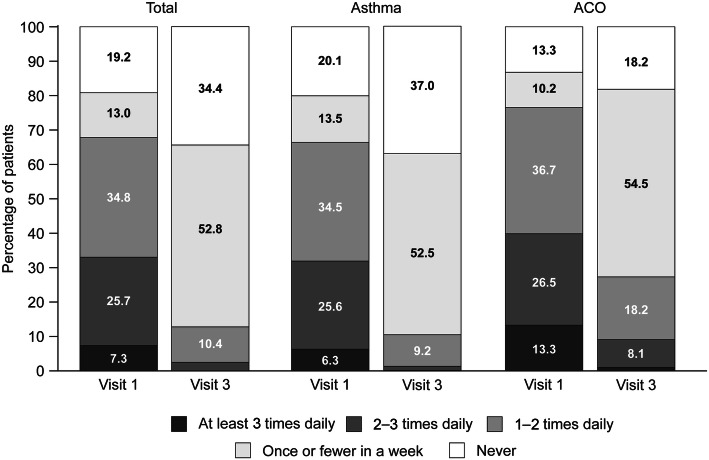

After switching to the Easyhaler® from other devices, significant improvement occurred in all groups of patients with asthma and COPD, including inhaler-naïve patients (Tables 3, 4). Patients with asthma had a mean (SD) ACT score of 14.2 (4.1) at baseline; disease control was significantly improved by visit 3 (p < 0.001), when the mean (SD) ACT score was 21.0 (2.7). By visit 3, 73.2% of all patients with asthma (asthma and ACO) had ‘well-controlled’ disease (Fig. 1a). Furthermore, a marked reduction in reliever inhaler use was observed at visit 3; 87.2% of all patients with asthma reportedly used their reliever inhaler no more than once a week compared with 32.2% of patients at visit 1 (Fig. 2).

Table 3.

Assessment of fixed-dose budesonide/formoterol fumarate combination therapy on changes in PRO measures and FEV1 (% predicted) in patients with asthma or ACO (n = 720)

| Asthma (n = 621) | ACO (n = 99) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visit 1 | Visit 3 | p value | Visit 1 | Visit 3 | p value | |

| Asthma control test | ||||||

| All patients | 14.2 (4.1) | 21.0 (2.7) | < 0.001 | 13.6 (4.1) | 18.7 (3.1) | < 0.001 |

| Inhaler-naïve patients | 14.3 (4.0) | 21.1 (2.6) | < 0.001 | 14.6 (3.0) | 18.9 (1.9) | 0.001 |

| Patients switching to Easyhaler® | 14.2 (4.2) | 20.9 (2.7) | < 0.001 | 13.4 (4.3) | 18.7 (3.3) | < 0.001 |

| Mini-AQLQ | ||||||

| All patients | 3.8 (0.9) | 5.2 (0.7) | < 0.001 | 3.7 (0.9) | 4.6 (0.8) | < 0.001 |

| Inhaler-naïve patients | 3.9 (0.9) | 5.3 (0.7) | < 0.001 | 4.0 (0.8) | 4.7 (0.7) | < 0.001 |

| Patients switching to Easyhaler® | 3.8 (0.9) | 5.1 (0.8) | < 0.001 | 3.6 (0.9) | 4.6 (0.8) | < 0.001 |

| FEV 1 (% predicted) | ||||||

| All patients | 76.7 (19.3) | 85.3 (20.3) | < 0.001 | 56.7 (18.3) | 62.4 (20.2) | < 0.001 |

| Inhaler-naïve patients | 77.1 (19.6) | 85.8 (19.7) | < 0.001 | 54.4 (17.3) | 64.1 (17.1) | < 0.001 |

| Patients switching to Easyhaler® | 76.4 (19.1) | 85.0 (20.6) | < 0.001 | 57.2 (18.5) | 62.0 (20.8) | < 0.001 |

Data are presented as mean (SD). p values refer to Wilcoxon’s signed rank test of change from baseline (visit 1) at visit 3 (week 12 of treatment)

ACO asthma-COPD overlap, AQLQ asthma quality of life questionnaire, PRO patient-reported outcome

Table 4.

Assessment of fixed-dose budesonide/formoterol fumarate combination therapy on changes in PRO measures and FEV1 (% predicted) in patients with COPD or ACO (n = 877)

| COPD (n = 778) | ACO (n = 99) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visit 1 | Visit 3 | p value | Visit 1 | Visit 3 | p value | |

| COPD assessment test | ||||||

| All patients | 24.2 (5.7) | 18.2 (5.1) | < 0.001 | 23.7 (6.5) | 18.3 (4.7) | < 0.001 |

| Inhaler-naïve patients | 23.8 (5.6) | 17.9 (4.9) | < 0.001 | 23.1 (6.0) | 18.7 (5.0) | < 0.001 |

| Patients switching to Easyhaler® | 24.4 (5.8) | 18.3 (5.1) | < 0.001 | 23.8 (6.6) | 18.3 (4.6) | < 0.001 |

| mMRC dyspnea scale | ||||||

| All patients | 1.9 (0.9) | 1.2 (0.8) | < 0.001 | 1.8 (0.9) | 1.1 (0.9) | < 0.001 |

| Inhaler-naïve patients | 1.7 (0.8) | 1.0 (0.7) | < 0.001 | 1.5 (0.9) | 0.8 (0.8) | 0.002 |

| Patients switching to Easyhaler® | 2.0 (0.9) | 1.2 (0.8) | < 0.001 | 1.9 (0.9) | 1.1 (0.9) | < 0.001 |

| FEV 1 (% predicted) | ||||||

| All patients | 51.3 (17.0) | 58.6 (17.9) | < 0.001 | 56.7 (18.3) | 62.4 (20.2) | < 0.001 |

| Inhaler-naïve patients | 54.9 (18.0) | 63.8 (19.5) | < 0.001 | 54.4 (17.3) | 64.1 (17.1) | < 0.001 |

| Patients switching to Easyhaler® | 49.9 (16.4) | 56.6 (16.9) | < 0.001 | 57.2 (18.5) | 62.0 (20.8) | < 0.001 |

Data are presented as mean (SD). p values refer to Wilcoxon’s signed rank test of change from baseline (visit 1) at visit 3 (week 12 of treatment)

ACO asthma-COPD overlap, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, mMRC modified medical research council, PRO patient-reported outcome

Fig. 1.

Evaluation of disease control in a. Patients with asthma or ACO (n = 720) and b. Patients with COPD or ACO (n = 876) following 12 weeks’ treatment with Bufomix Easyhaler®. a Patients with asthma or ACO (n = 720). b Patients with COPD or ACO (n = 876). ACO asthma-COPD overlap, ACT asthma control test, CAT COPD assessment test, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Fig. 2.

Frequency of reliever inhaler use in patients with asthma (n = 619) or ACO (n = 99) following 12 weeks’ treatment with the Bufomix Easyhaler®. ACO asthma-COPD overlap

Patients with COPD had a mean (SD) CAT score of 24.2 (5.7) at baseline. Disease control was significantly improved by visit 3 (p < 0.001) when the mean (SD) CAT score was 18.2 (5.1). By visit 3, 67.7% of all COPD patients (COPD and ACO) experienced low-medium disease impact on their QoL (CAT ≤ 20; Fig. 1b).

Overall, twelve weeks of treatment with the Bufomix Easyhaler® resulted in a significant improvement in lung function (FEV1% predicted). In total, mean (SD) FEV1% predicted increased from 62.2% (21.8) at baseline to 69.9% (23.1) at visit 3 (p < 0.001). Similar improvements in lung function were observed in all patient groups; patients with asthma, COPD and ACO (Tables 3, 4). Most importantly, significant improvement in lung function was observed in patients who switched to the Bufomix Easyhaler® from another inhaler.

Effect of Bufomix Easyhaler® on Health-related Quality of Life

Patients with asthma had a mean (SD) mini-AQLQ score of 3.8 (0.9) at baseline, indicating a moderate impairment of QoL from asthma. A significant improvement in mini-AQLQ score, indicating some impairment, was observed by visit 3 [5.2 (0.7); p < 0.001] (Table 3).

Patients with COPD had a mean (SD) mMRC score of 1.9 (0.9) at baseline, indicating that most patients walk more slowly than people of the same age because of breathlessness or must stop for breath when walking at their own pace. A significant improvement in the mMRC score was observed by visit 3 [1.2 (0.8); p < 0.001] (Table 4).

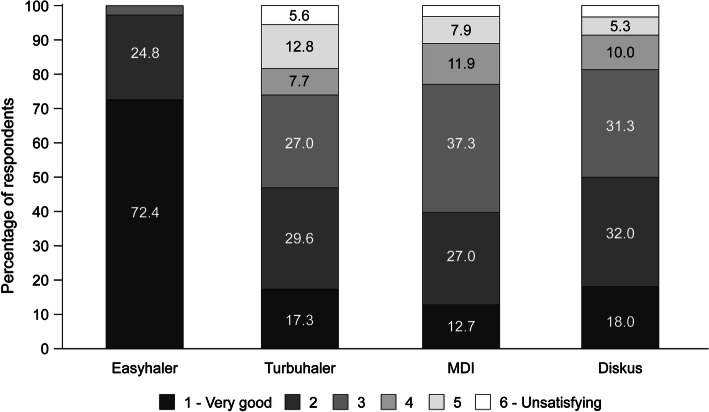

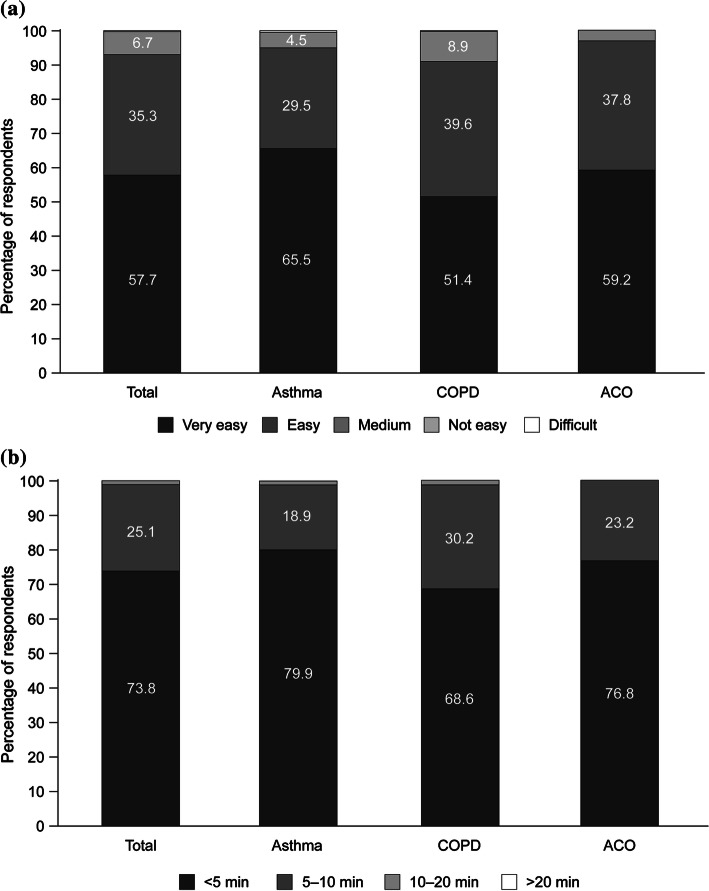

Patient Satisfaction with the Use of Bufomix Easyhaler® and Physicians’ Assessments

Patients were asked to describe their perceptions of different attributes of their current treatment from the multiple-choice questions (Table 1). Overall, patient satisfaction was higher for the Bufomix Easyhaler® than for the other inhalers (Fig. 3). Furthermore, more than 90.0% of physicians described the Bufomix Easyhaler® as easy to teach, with 98.9% of their patients having learned the technique within 10 min and 73.8% within 5 min of teaching (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Patient satisfaction by inhaler type (visit 3, following 12 weeks’ treatment with the Bufomix Easyhaler®; visit 1 for other devices) (n = 1043). MDI metered dose inhaler

Fig. 4.

Physician assessment of a. Ease of use* and b. Time taken to teach Easyhaler® use** (asthma: n = 617; COPD: n = 775; ACO: n = 98). *Evaluated at visits 1–3 (through 12 weeks’ treatment with the Bufomix Easyhaler®); **evalauted at visit 1, after initial teaching of Easyhaler use to the patient by the physician. ACO asthma-COPD overlap

Discussion

We present the first real-world PRO data collected from patients with obstructive airway disease using the Bufomix Easyhaler® in everyday practice in Hungary. The results obtained demonstrate that most patients with obstructive airway disease, treated with budesonide/formoterol fumarate combination therapy (Bufomix Easyhaler®), may obtain well-controlled disease or complete control (ACT score 20–25; CAT score < 20) when treated in a real-world study setting. Roughly 3 months after switching to the Bufomix Easyhaler®, patients had improved lung function, and all groups (including patients who switched from another device to the Bufomix Easyhaler®) showed significant improvement in the quality of life in all parameters assessed. No adverse events were reported by the participating physicians, supporting the safety profile of Bufomix Easyhaler® formulations for patients with obstructive airway disease.

Overall, patients considered the Bufomix Easyhaler® as portable, easy to use and easy to keep clean during daily activities. This statement is supported by the continued use of the Bufomix Easyhaler® throughout the study, with no discontinuations reported. Furthermore, study physicians reported that use of the Bufomix Easyhaler® was easy to teach, with their patients learning inhaler use quickly. Our data support previous patient preference data (based on studies in children and adults) that demonstrated the Easyhaler® was easy to teach, learn and use, coupled with more user satisfaction [18, 32]; findings were recently confirmed by a meta-analysis [19].

The Bufomix Easyhaler® achieved well-controlled disease or complete disease control despite a high proportion of patients being smokers. Patients were satisfied with the therapy, and the Easyhaler® was easy for them to use. Most of our patient population had primary or high school education; therefore, it is likely that ease of use and adequate training on how to use the inhaler were important in ensuring the optimal dosing, as a suboptimal inhalation technique may have clinical implications [14].

Our study provides real-world data using a large representative sample of Hungarian patients using the Bufomix Easyhaler® in everyday clinical practice. Although the analyses were robust and performed using verified questionnaires, the study has limitations. The study was an open-label, non-parallel design study with no comparator devices, and the study population may have biased the assessment of patient preferences for inhaler device, as only patients who were uncontrolled and therefore likely to have been unsatisfied with their previous inhaler were evaluated. Furthermore, data on patient adherence and product-specific training for previous inhalers were unavailable for inclusion. Conclusions on the effectiveness of the Bufomix Easyhaler® are also limited by the lack of exacerbation data for patients with asthma and COPD and direct comparisons between inhalers.

There is a limited body of real-world data for patient-reported outcomes with the Bufomix Easyhaler®. A similar trial to the current study (though conducted in patients with asthma only) was recently completed in Sweden; this will report non-inferiority of asthma control [as measured by ACT (primary end point)] in patients who switched from the Symbicort Turbuhaler® (Astrazeneca, Cambridge, UK) to Bufomix Easyhaler® [33]. Future studies should also evaluate whether improved effectiveness and QoL outcomes with the Bufomix Easyhaler® versus comparators also translate into improved long-term adherence.

Conclusion

The results obtained demonstrate the clinical effectiveness of the Bufomix Easyhaler® in the treatment of outpatients with obstructive airway disease in routine daily clinical practice. These data need to be verified in other populations where the Bufomix Easyhaler® is approved for use. Patients with uncontrolled airway obstruction may benefit from switching their inhaler therapy to the Bufomix Easyhaler®.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the patients who participated in this study.

Funding

Sponsorship for this study and article processing charges were provided by Orion Corp., Orion Pharma. All authors had full access to all of the data in the study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Medical Writing and Other Assistance

Mikko Vahteristo, MSc (Stat), of Orion Corp. provided assistance with statistical analyses. Medical writing support was provided by David Griffiths, PhD, and Jonathan Plumb, PhD, of Bioscript Medical, funded by Orion Corp., Orion Pharma.

Authorship

All authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Lilla Tamási, Maria Szilasi and Gabriella Gálffy have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

All procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the National Scientific and Research Ethics Committee of Hungary and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study, prior to study commencement.

Data Availability

The data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Footnotes

Enhanced digital content

To view enhanced digital content for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.6797690.

References

- 1.World Health Organisation. Global Health Observatory (GHO) Data. 2016. http://www.who.int/gho/ncd/mortality_morbidity/en/ Accessed 12 April 2018.

- 2.Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA), National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health. GINA report Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. http://ginasthma.org/2018-gina-report-global-strategy-for-asthma-management-and-prevention/. Accessed 12th April 2018.

- 3.Müller V, Gálffy G, Orosz M, et al. Characteristics of reversible and nonreversible COPD and asthma and COPD overlap syndrome patients: an analysis of salbutamol Easyhaler data. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:93–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peters SP, Ferguson G, Deniz Y, Reisner C. Uncontrolled asthma: a review of the prevalence, disease burden and options for treatment. Respir Med. 2006;100(7):1139–51. 10.1016/j.rmed.2006.03.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pavord ID, Mathieson N, Scowcroft A, Pedersini R, Isherwood G, Price D. Author correction: the impact of poor asthma control among asthma patients treated with inhaled corticosteroids plus long-acting beta2-agonists in the United Kingdom: a cross-sectional analysis. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2017;27(1):65. 10.1038/s41533-017-0063-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slejko JF, Ghushchyan VH, Sucher B, et al. Asthma control in the United States, 2008-2010: indicators of poor asthma control. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(6):1579–87. 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.10.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Price D, Fletcher M, van der Molen T. Asthma control and management in 8000 European patients: the REcognise Asthma and LInk to Symptoms and Experience (REALISE) survey. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2014;24:14009. 10.1038/npjpcrm.2014.9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miravitlles M, Ribera A. Understanding the impact of symptoms on the burden of COPD. Respir Res. 2017;18(1):67. 10.1186/s12931-017-0548-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Global Asthma Network. The global asthma Report. 2014. http://www.globalasthmareport.org/resources/Global_Asthma_Report_2014.pdf. Accessed 12 April 2018.

- 10.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of chronic obstructive lung disease. http://goldcopd.org/. Accessed 12th April 2018.

- 11.Pauwels RA, Löfdahl CG, Postma DS, et al. Effect of inhaled formoterol and budesonide on exacerbations of asthma. Formoterol and corticosteroids establishing therapy (FACET) international study group. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(20):1405–11. 10.1056/NEJM199711133372001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferguson GT, Tashkin DP, Skärby T, et al. Effect of budesonide/formoterol pressurized metered-dose inhaler on exacerbations versus formoterol in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the 6-month, randomized RISE (Revealing the Impact of Symbicort in reducing Exacerbations in COPD) study. Respir Med. 2017;132:31–41. 10.1016/j.rmed.2017.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laube BL, Janssens HM, de Jongh FH, et al. What the pulmonary specialist should know about the new inhalation therapies. Eur Respir J. 2011;37(6):1308–31. 10.1183/09031936.00166410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Selroos O, Pietinalho A, Riska H. Delivery devices for inhaled asthma medication. Clinical implications of differences in effectiveness. BioDrugs. 1996;6:273–99. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lavorini F, Magnan A, Dubus JC, et al. Effect of incorrect use of dry powder inhalers on management of patients with asthma and COPD. Respir Med. 2008;102(4):593–604. 10.1016/j.rmed.2007.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Melani AS, Bonavia M, Cilenti V, et al. Inhaler mishandling remains common in real life and is associated with reduced disease control. Respir Med. 2011;105(6):930–8. 10.1016/j.rmed.2011.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Orion Pharma. Bufomix Easyhaler® SPC. http://www.medicines.ie/medicine/16038/SPC/Bufomix+Easyhaler®+320+micrograms+9+micrograms/ Accessed 12th April 2018.

- 18.Malmberg LP, Everard ML, Haikarainen J, Lahelma S. Evaluation of in vitro and in vivo flow rate dependency of budesonide/formoterol Easyhaler((R)). J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2014;27(5):329–40. 10.1089/jamp.2013.1099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haikarainen J, Rytilä P, Roos S, Metsarinne S, Happonen A. Dose uniformity of budesonide Easyhaler(R) under simulated real-life conditions and with low inspiration flow rates. Chron Respir Dis. 2017. 10.1177/1479972317745733. 10.1177/1479972317745733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lähelmä S, Sairanen U, Haikarainen J, et al. Equivalent Lung dose and systemic exposure of budesonide/formoterol combination via easyhaler and turbuhaler. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2015;28(6):462–73. 10.1089/jamp.2014.1195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lähelmä S, Vahteristo M, Metev H, et al. Equivalent bronchodilation with budesonide/formoterol combination via easyhaler and turbuhaler in patients with asthma. Respir Med. 2016;120:31–5. 10.1016/j.rmed.2016.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pirożyński M, Hantulik P, Almgren-Rachtan A, Chudek J. evaluation of the efficiency of single-inhaler combination therapy with budesonide/formoterol fumarate in patients with bronchial asthma in daily clinical practice. Adv Ther. 2017;34(12):2648–60. 10.1007/s12325-017-0641-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.European Medicines Compendium. Orion pharma (UK) limited. Summary of product characteristics for fobumix easyhaler 160/4.5 inhalation powder. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/8706/smpc/ Accessed 22 June 2016.

- 24.European Medicines Compendium. Orion pharma (UK) limited. Summary of product characteristics for fobumix easyhaler 320 micrograms/9 micrograms, inhalation powder. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/8438/smpc/ Accessed 22 June 2016.

- 25.Thomas M, Kay S, Pike J, et al. The asthma control test (ACT) as a predictor of GINA guideline-defined asthma control: analysis of a multinational cross-sectional survey. Prim Care Respir J. 2009;18(1):41–9. 10.4104/pcrj.2009.00010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Cox FM, Ferrie PJ, King DR. Development and validation of the mini asthma quality of life questionnaire. Eur Respir J. 1999;14(1):32–8. 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.14a08.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones PW, Harding G, Berry P, Wiklund I, Chen WH, Kline Leidy N. Development and first validation of the COPD assessment test. Eur Respir J. 2009;34(3):648–54. 10.1183/09031936.00102509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hsu KY, Lin JR, Lin MS, Chen W, Chen YJ, Yan YH. The modified medical research council dyspnoea scale is a good indicator of health-related quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Singapore Med J. 2013;54(6):321–7. 10.11622/smedj.2013125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hantulik P, Wittig K, Henschel Y, Ochse J, Vahteristo M, Rytila P. Usage and usability of one dry powder inhaler compared to other inhalers at therapy start: an open, non-interventional observational study in Poland and Germany. Pneumonol Alergol Pol. 2015;83(5):365–77. 10.5603/PiAP.2015.0059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller MR, Crapo R, Hankinson J, et al. General considerations for lung function testing. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(1):153–61. 10.1183/09031936.05.00034505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(2):319–38. 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gälffy G, Mezei G, Németh G, et al. Inhaler competence and patient satisfaction with easyhaler(R): results of two real-life multicentre studies in asthma and COPD. Drugs R D. 2013;13(3):215–22. 10.1007/s40268-013-0027-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rytilä PH, Syk J, Vinge I, Sörberg M. Switch from Symbicort Turbuhaler to Budesonide/Formoterol Easyhaler; a real-life prospective study in asthma patients. Orion Pharma. Data on file 2018. Abstract accepted for presentation at the European Respiratory Society Meeting, to be published in a supplement of the European Respiratory Journal, September 2018.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.