Abstract

Purpose of Review

Adalimumab is one of the top-selling drugs worldwide. Its imminent patent expiration has seen the emergence of numerous biosimilar agents. In this article, we recap the evidence from bio-originator trials in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) to provide context for a critical review of biosimilar trial data.

Recent Findings

Currently, three adalimumab biosimilars are approved in Europe and/or the USA: Amgen’s ABP 501 (AMJEVITA/Solymbic), Boehringer Ingelheim’s BI 695501 (Cyltezo) and Samsung Bioepis’s SB5 (Imraldi). All three agents met their pre-specified equivalence criteria. Subtle differences in adverse events and clinical responses between the reference and biosimilar products were noted.

Summary

The introduction of adalimumab biosimilars will offer exciting opportunities in improving treatment access and increasing treatment options for RA and other licensed indications. Real-world data will further provide assurances on efficacy as well as safety.

Keywords: Adalimumab, Biosimilar, Rheumatoid arthritis, Amgevita, Cyltezo, Imraldi

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic, autoimmune, systemic inflammatory disease. If inadequately treated, it can lead to irreversible joint damage and disability at significant costs to the individual as well as the wider economy. Life expectancy of patients with severe RA is reduced by 10 years on average [1–3], whilst the total costs of RA to society were estimated at €45 billion in Europe and $52 billion in the USA in 2006 [4].

With improved understanding of RA’s molecular pathophysiology, increasingly targeted treatments were developed in addition to conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (csDMARDs) such as methotrexate (MTX). Around the turn of the century, biologic drugs were introduced that selectively targeted tumour necrosis factor (TNF). TNF inhibitors (TNFi), along with other biologic DMARDs (bDMARDs), formed an effective second-line for those with inadequate response to csDMARDs and dramatically improved mortality and outcomes for RA patients [5–7].

In 2002, Humira, the originator adalimumab, became the third TNFi to be approved in the USA after infliximab and etanercept. It is the best-selling drug worldwide, with global sales of $18 billion in 2017 alone [8]. It is also one of the most versatile, being additionally approved for use in ankylosing spondylitis/axial spondyloarthritis, plaque psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis, hidradenitis suppurativa and non-infectious uveitis [9]. It has become the benchmark agent against which newer biologic or targeted synthetic DMARDs are compared.

The inevitable patent expiration for TNFi stimulated programmes to develop molecules that, whilst not identical to the originator, could be considered to be a biological equivalent of a ‘generic’. Such ‘biosimilars’ are defined as biological agents that are similar in terms of quality, safety and efficacy to the licensed reference product (RP) [10]. Biosimilars of infliximab and etanercept are already established worldwide and, for most countries, biosimilar adalimumab will enter the market in the last quarter of 2018 when Humira’s exclusivity expires.

In this article, we summarise the pharmacology and clinical efficacy of adalimumab to provide context for a critical review of evidence from randomised controlled trials of its biosimilars in RA. We focus on biosimilars that are approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and/or the US Food and Drugs Administration (FDA).

Pharmacology

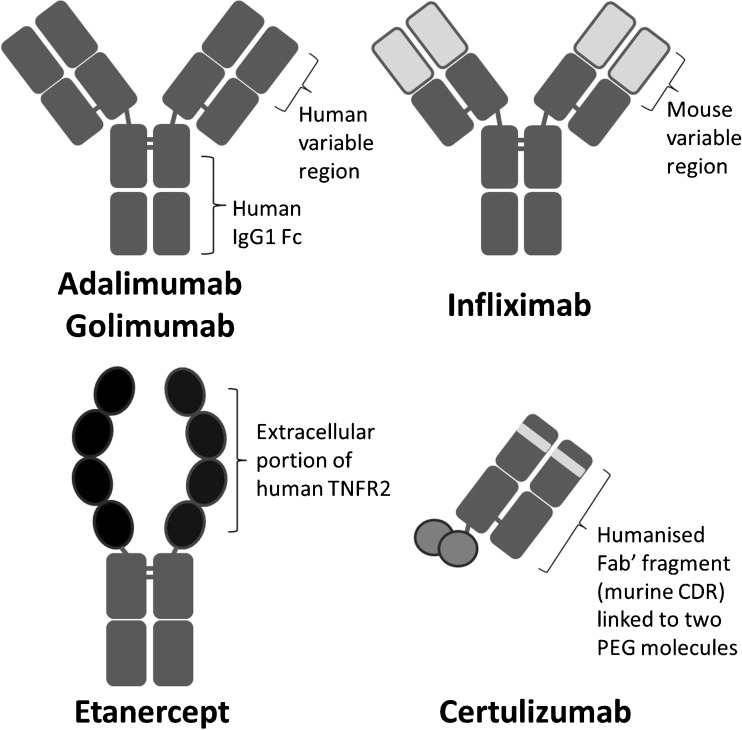

Adalimumab is a recombinant, fully human, IgG1 monoclonal antibody that is structurally and functionally indistinguishable from naturally occurring human IgG1 (Fig. 1). It was engineered through phage display technology and is produced in a Chinese hamster ovary cell line [11].

Fig. 1.

Adalimumab structure compared with other TNF inhibitors. TNFR2 TNF receptor 2, Fc fragment crystallisable region, Fab’ antigen-binding fragment, CDR complementarity-determining regions, PEG polyethylene glycol

Adalimumab is administered by subcutaneous injection, reaching peak serum concentrations after approximately 131 h [12]. It is widely distributed, including into the synovium. Similar to naturally occurring human IgG1, its elimination half-life is around 10 to 14 days. Adalimumab binds specifically to TNF-alpha (both soluble and membrane-bound) and blocks their interaction with p55 and p75 cell surface TNF receptors [12].

Despite being a fully human antibody, up to 30% of RA patients develop anti-drug antibodies (ADAb) to adalimumab [13]. ADAb can block the drug from binding to its target and/or form immune complexes; they have been shown to decrease serum drug levels and increase markers of inflammation in RA patients [13].

Clinical Efficacy of Adalimumab

The efficacy of adalimumab in both early and long-standing RA has been demonstrated by several phase III randomised controlled trials (Table 1) and open-label extensions [14, 15]. For the remainder of the review, we refer to the standard dosing of 40 mg every 2 weeks unless otherwise stated. Common outcome measures included ACR responses (20, 50 or 70% improvement in the ACR core set measurements), DAS28 remission (< 2.6), EULAR response (based on changes in DAS28) and patient-reported physical disability assessed via Health Assessment Questionnaires (HAQ). Radiographic progression was measured by modified or original total Sharp score.

Table 1.

Study and patient characteristics of adalimumab trials in rheumatoid arthritis

| Study | Trial size and duration | Treatment arms | Country | Treatment history | Age, years | Females, % | Disease duration, years | Mean TJC, n | Mean SJC, n | HAQ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weinblatt 2003 (ARMADA) |

n = 271 24 weeks |

Humira 20 mg + MTX Humira 40 mg + MTX Humira 80 mg + MTX Placebo + MTX |

35 sites in the USA and Canada | On stable MTX only, failed at least 1 DMARD, biologic naive | 55.5 | 77 | 12.3 | 28.9 | 17.2 | 1.56 |

| Keystone 2004 |

n = 619 52 weeks |

Humira 20 mg + MTX Humira 40 mg + MTX Placebo + MTX |

89 sites in the USA and Canada | On stable MTX only, biologic naive | 56.5 | 75 | 10.9 | 27.8 | 19.3 | 1.48 |

| Breedveld 2006 (PREMIER) |

n = 799 2 years |

Humira 40 mg + MTX Humira 40 mg + placebo Placebo + MTX |

11 sites in Australia, 85 Europe, 37 N. America | MTX naive | 52.0 | 74 | 0.7 | 31.6 | 21.7 | 1.5 |

| Furst 2003 (STAR) |

n = 636 24 weeks |

Humira 40 mg + standard DMARD Placebo + standard DMARD |

69 sites in the USA and Canada | Stable standard treatment (DMARD, low-dose steroids, NSAIDs, alnalgesia), biologic naive | 55.4 | 79 | 10.4 | 27.5 | 21.1 | 1.40 |

| van de Putte 2004 |

n = 544 26 weeks |

Humira 20 mg weekly Humira 20 mg alternate weeks Humira 40 mg weekly Humira 40 mg alternate weeks Placebo |

52 sites Europe, Canada, Australia | Failed at least one DMARD, biologic naive | 53 | 77 | 11 | 34.4 | 19.8 | 1.9 |

| Cohen 2016 |

n = 526 26 weeks |

ABP 501 + MTX Humira + MTX |

40 sites in E. Europe, 12 W. Europe, 38 N. America. 2 Mexico | Stable MTX, adalimumab naive, no more than 1 previous biologic | 55.9 | 81 | 9.4 | 24.1 | 14.4 | 1.49 |

| Weinblatt 2018 |

n = 544 52 weeks |

SB5 + MTX (rerandomised at w24) Humira + MTX |

51 sites in E. Europe and Republic of Korea | Stable MTX, biologic naive | 51.2 | 81 | 5.5 | 24.0 | 15.6 | 1.4 |

| Cohen 2018 |

n = 645 58 weeks |

BI 695501 + MTX (rerandomised at w24) Humira + MTX |

115 sites (68% E. Europe, 4% W. Europe, 19% USA, 8% Chile, 2% Asia) | Stable MTX, adalimumab naïve, no more than 1 previous biologic | 53.7 | 83 | 7.2 | 25.1 | 16.5 | 1.5 (median) |

| Jani 2016 |

n = 120 12 weeks |

ZRC3197 + MTX Humira + MTX |

11 sites in India | Stable MTX, biologic naive | 45 | 83 | 3.7 | 17.0 | 11.8 | 1.7 |

| Jamshidi 2017 |

n = 136 24 weeks |

CinnoRA + MTX Humira + MTX |

10 sites in Iran | Inadequate response to csDMARDs | 47.9 | 87 | – | 9.6 | 9.7 | 1.32 |

| Alten/Genovese 2017 (abstract) |

n = 728 24 weeks |

FKB327 + MTX Humira + MTX |

105 sites in E. and W. Europe, N. and S. America. | Stable MTX, adalimumab naïve | 55.3 | – | 8.5 | – | – | – |

MTX methotrexate, SJC swollen joint count, TJC tender joint count, HAQ Health Assessment Questionnaire

As monotherapy, adalimumab recipients had significantly better outcomes than placebo in terms of function, ACR and EULAR responses [16]. The exposure-time-adjusted incidence of adverse events (AEs) was comparable to placebo, including serious infections and malignancies. However, as biosimilar trials did not include monotherapy, it will not be discussed further in this review.

Adalimumab monotherapy was not superior to MTX monotherapy in terms of ACR response or DAS28 remission over 2 years in the PREMIER study (of MTX naive, early RA patients) [17]. It was, however, superior to MTX monotherapy at improving function and slowing/preventing radiographic progression. Both monotherapy groups had comparable incidences of AEs, including serious infections.

Adalimumab combination therapy with MTX was superior to adalimumab or MTX monotherapies for all clinical and radiographic outcomes in early as well as established disease [17–19]. ACR responses were superior when standard csDMARD treatment was combined with adalimumab than without [20]. Incidence of AEs was similar in combination and monotherapy groups [17–20]. Adalimumab combination therapy with MTX was associated with higher incidence of serious infections than MTX monotherapy [17, 19].

Other bDMARDs were similar in efficacy to adalimumab in head-to-head trials [21–24], network meta-analysis [25] and observational cohorts [26, 27]. Only IL6 inhibitors (as monotherapies) [28, 29] and the targeted synthetic DMARD, Baricitinib (as combination therapy), demonstrated superiority [30].

Adalimumab Biosimilars

Biosimilar approval does not require the manufacturer to re-establish efficacy but is instead based on the demonstration that there are no clinically meaningful differences from the RP [10, 31, 32]. Once biosimilarity has been established in one indication, the drug may be approved for additional indications held by the RP without comparative clinical trials. Extrapolation of indication reduces the number and size of clinical trials required, thus decreasing financial cost and, potentially, increasing access [32].

At the time of writing, three adalimumab biosimilars are approved in the EU and/or the USA: Amgen’s ABP 501, Boehringer Ingelheim’s BI 695501 and Samsung Bioepis’s SB5. In the following sections, we will review each in terms of clinical outcomes and trial characteristics. Other biosimilars will be mentioned in passing, including FKB327 by Fujifilm Kyowa Kirin Biologics which has phase III RA trial published in abstract form [33, 34]; Sandoz’s GP2017 which has phase III plaque psoriasis trial in abstract form [35] and has been accepted for regulatory review [36]; and CinnoRA (Iran) and Exemptia (India) which have published RCTs on PubMed [37, 38]. Additional pipeline biosimilars with completed/ongoing phase III trials are listed in Table 2. Torrent Pharmaceuticals (India) was the second company in the world to launch an adalimumab biosimilar, Adfrar [39]. However, its trial evidence is not PubMed accessible and will not be included in this review.

Table 2.

Adalimumab biosimilar pipeline as of April 2018

| Adalimumab biosimilar | Manufacturer | Trial status | Trial registration number |

|---|---|---|---|

| FKB327 | Fujifilm Kyowa Kirin Biologics | Phase III completed | NCT02260791 |

| PF-06410293 | Pfizer | Phase III completed | NCT02480153 |

| CHS-1420 | Coherus BioSciences | Phase III completed | NCT02489227 |

| M923 / BAX923 | Momenta | Phase III (PsO) completed | NCT02581345 |

| MYL-1401A | Mylan | Phase III (PsO) completed | NCT02714322 |

| LBAL | LG Life Sciences | Phase III ongoing | NCT02746380 |

| MSB11022 | Merck KGaA | Phase III ongoing | NCT03052322 |

| GP2017 | Sandoz | Phase III ongoing | EudraCT: 2015-003433-10 |

| BCD-057 | Biocad | Phase III (PsO) ongoing | NCT02762955 |

| ONS-3010 | Oncobiologics | Phase III (PsO) ongoing | EudraCT: 2015-004614-26 |

PsO plaque psoriasis

ABP 501

Amgen’s ABP 501 was the first adalimumab biosimilar to be approved by the FDA in 2016 (as AMJEVITA) and by the EMA in 2017 (as AMGEVITA/Solymbic). The manufacturer demonstrated that ABP 501 and the RP were highly similar in structure, function and pharmacokinetics (PK) [40–42]. Subsequent phase III studies were conducted in both plaque psoriasis [43] and RA [44•].

The RA trial was a randomised, double-blind, active comparator-controlled, 26-week equivalence study, comparing ABP 501 with US- and EU-sourced RP [44•]. Participants did not undergo switching between ABP 501 and the RP. The trial included 526 patients with moderate to severe active RA despite MTX. Unlike the original RP trials, 28% of patients had prior exposure to bDMARD (but not adalimumab); whether these participants failed prior bDMARDs due to inefficacy or AEs was not discussed.

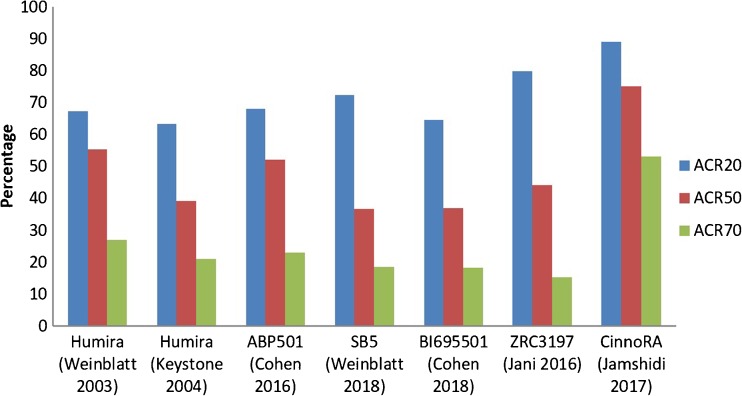

The primary endpoint was the risk ratio (RR) of achieving ACR20 at week 24, which was achieved in 74.6% of the ABP 501 group and 72.4% in the RP group (using Full Analysis Set (FAS))—numerically higher than response rates from pivotal RP trials. Results of the per-protocol set (PPS) analysis were similar (raw results were not provided). The ACR20 RR was 1.039 (90%CI 0.954 to 1.133), which was within the margin of 0.738 to 1.355 required to demonstrate equivalence. Equivalence was also demonstrated in patients with plaque psoriasis as monotherapy [43].

In the RA study, the RR of ACR20 for ABP 501 was 1.421 (95% CI 1.086 to 1.860) after 2 weeks, suggesting superiority over the RP [45, 46]. This was also seen at week 12. However, the difference was not statistically significant at other time points. Furthermore, there were no significant differences in secondary outcomes (ACR50/70, DAS28). The EMA therefore concluded that differences were likely a chance finding rather than superiority in onset of action.

The proportions of binding ADAb (38.3 vs 38.2%) and neutralising ADAb (9.1 vs 11.1%) were similar for ABP 501 and the RP, respectively. More patients discontinued treatment (6.8 vs 4.6%) and the study (8.0 vs 4.2%) in the ABP 501 group; there were no specific AEs leading to withdrawal. Liver enzyme elevations occurred in 4.9% of the ABP 501 group and in 3.8% in the RP group. This signal for ABP 501 was also seen in the psoriasis study (5.9 vs 2.5%) [43]. However, the EMA concluded that these events occurred to a large extent in subjects with abnormal baseline values [45, 46].

Injection site reactions were less common in the ABP 501 group (1.7 vs 5.2%). This was also seen in the psoriasis trial (1.3% v 3.8%) and explained as differences in the excipients rather than biosimilarity.

BI 695501

Boehringer Ingelheim’s BI 695501 (Cyltezo) was approved by the EMA and FDA in 2017. It was shown to be similar to the RP in structure, function and PK [47, 48•]. Equivalence studies were published in RA [48•], completed in plaque psoriasis (NCT02850965) and is ongoing in Crohn’s disease (NCT02871635).

VOLTAIRE-RA was a randomised, double-blind, parallel-arm, 58-week study, comparing BI 695501 with US-sourced RP [48•]. The trial cohort comprised 645 patients with moderate to severe RA despite MTX, 27% of whom had prior exposure to bDMARD (but not adalimumab); again, reasons for prior bDMARD failure were not provided. At week 24, patients on the RP were rerandomised to BI 695501 or to stay on the RP. At week 48, all patients were entered into an open-label extension until week 58.

Co-primary endpoints were percentage of patients achieving ACR20 at 12 and 24 weeks (using FAS). At week 12, 67.0% of BI 695501 recipients and 61.1% of RP recipients achieved ACR20. The difference (5.9%; 90%CI − 0.9 to 12.7) was within − 12 to 15% set by the FDA to demonstrate equivalence; PPS results were similar (4.3%; 95%CI − 2.8 to 11.3). At week 24, 69.0 and 64.5% of BI 695501 and RP recipients achieved ACR20, respectively. This difference of 4.5% (90%CI − 3.4 to 12.5) was within ± 15% set by the EMA (PPS 1.6%; 95%CI − 5.3 to 8.5). Secondary endpoints (ACR and EULAR responses, DAS28, SF-36) were also similar.

There was a trend for superior ACR20 response for BI 695501 [49]. At week 4 (the most steep and therefore sensitive part of the dose-response curve), 6.9% more of the BI 695501 group reached ACR20 than the RP group (confidence interval not provided). Similar trends were seen at weeks 4 and 12. However, differences between the two groups were smaller for ACR50 and ACR70 and did not persist over time. Another discrepancy was noted regarding persistence of ACR20 response: 74.3% of the BI 695501 group achieved ACR20 at week 24 but only 67.9% at week 48, while an increase was seen in the RP group (66.8 and 70.2%, respectively). Patients who switched from the RP to BI 695501 also showed trends of falling ACR 20 response (72.3% at week 24, 64% at week 48). This was dismissed as likely a chance finding since it was not seen with other outcome measures.

There were no clinically meaningful differences in proportions of ADAb (BI 695501 47.4%, RP 53.0% up to week 24); neutralising ADAb prevalence was also similar (raw results were not provided). The number of patients with at least one AE was 59.6% in the BI 695501 group and 60.0% in the RP group. Several safety outcomes were in favour of BI 695501: serious AEs (5.6 vs. 9.7%), injection site reactions (1.9 vs 5.7%), serious infections (0.6 vs 4.0%) and hypersensitivity reactions (2.8 vs 4.6%). However, three aspects of safety initially raised the concern about the safety profile of BI 695501. First, haematological disorders were more frequent in the continuous BI 695501 group than continuous RP group (5.2 vs 2.9%): anaemia (8 patients, 2.5%) and ‘haemoglobin decreased’ (2 patients, 0.6%) were reported exclusively in the BI 695501 group. These AEs were mostly mild to moderate and did not lead to drug discontinuation. Furthermore, five of these patients had low haemoglobin at baseline. Second, bone fractures occurred exclusively in the BI 695501 group (7 patients, 2.2%). This was also observed in the PK trial [47]. However, the incidence rate (20.8 per 1000 patient-years) was within the range of bone fracture risk in the general population (8.5 to 36.0 per 1000 patient-years). Third, patients who received BI 695501 more frequently screened positive for TB (no active cases) at week 48: 8 patients (2.8%) in the BI 695501 group, 1 patient (0.7%) in the RP group and 8 patients (5.7%) in the switch group (RP to BI 695501). All patients screened negative for TB at the start of the trial. The EMA accepted that all three were rare events and that the minor differences were likely a chance finding.

SB5

Samsung Bioepis’s SB5 (Imraldi) was approved by the EMA in 2017. Again, it was similar to the RP in structure, function and PK [50, 51•]. Its phase III study was a randomised, double-blind, parallel-arm, 52-week trial of 544 patients with moderate to severe RA despite MTX, comparing SB5 with US- and EU-sourced RP. Unlike the two biosimilar trials discussed above, all patients in this study were biologic naive at baseline. At week 24, patients on the RP were rerandomised to SB5 or the RP until week 52.

The primary endpoint was ACR20 response rate at week 24 using PPS, which was achieved by 72.4% of the SB5 and 72.2% of the RP group. The difference of 0.1% (95%CI − 7.8 to 8.1) was within ± 15% required to demonstrate equivalence. Results using FAS were similar (68.0 vs 67.4%, respectively) with a difference of 0.8% (95%CI - 7.0 to 8.6).

ACR20 and ACR50 at week 52 showed a trend of superior response in both SB5 and SB5/RP-switch groups compared to the RP group, using the PPS (upper limit of CI: 15.9%, exceeding ± 15%) but not using FAS [52]. The percentage of subjects who achieved major clinical response (ACR70 for 6 consecutive months) at week 52 was 15.7% in the SB5, 15.3% in the switch group and 9.7% in the RP group. Since the study was not designed to show similarity at week 52, these findings were not considered as superior response. Other response measures (ACR50/70, DAS28) were similar.

The incidence of ADAb was similar between SB5 and RP groups (33.1 vs 32.0% up to week 24, respectively). Overall, treatment emergent AEs occurred in 35.8% of the SB5 and 40.7% of the RP group; 10.1 and 11.7%, respectively, were considered related to the study drug. The number of injection site reactions was higher in RP recipients (32 reactions in 4 patients) compared to SB5 recipients (9 reactions in 8 patients) at week 52, although the proportions of patients were comparable (3.1 vs 3.0%, respectively). The rate of discontinuation due to AEs was lower in the SB5 than RP group (0.7 vs 3.3% at week 24; 1.5 vs 2.4% at week 52).

Equivalence and Switching

An interesting observation in biosimilar trials was that clinical responses in their RP groups were often different from responses reported in pivotal RP trials. For example in the EGALITY plaque psoriasis study, PASI75 response (75% improvement in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index) of the etanercept RP group (76%) was much higher than in previous RP studies (47 to 49%) [53–55]. Similarly, PASI75 response at week 16 to the RP was 86% in the ABP 501 trial but 71 to 80% in pivotal trials [43, 56, 57]. Similar trends have also been observed for etanercept and infliximab trials in RA [58]. These discrepancies may be attributable to fundamental differences in study design and/or characteristics of the study population.

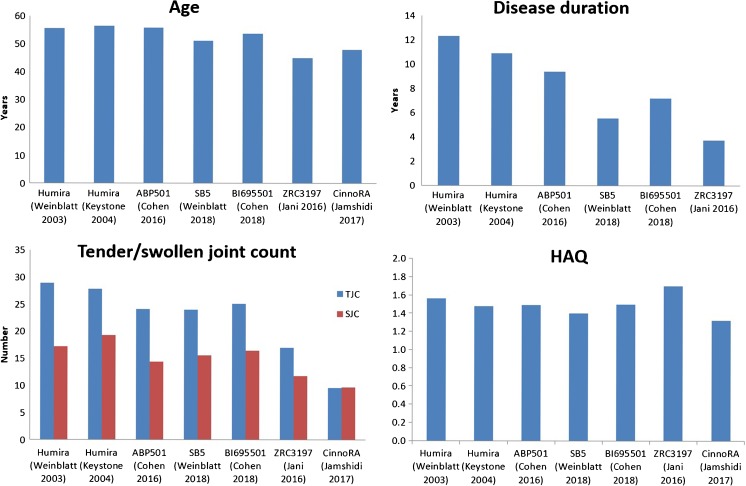

Unlike the pivotal RP trials that were mostly conducted in North America, trials for SB5, ABP 501 and BI 695501 were predominantly conducted in Eastern European countries (Table 1). These patients may receive better healthcare if enrolled, thereby incentivising trial engagement but possibly introducing bias. It is also possible that the greater response rates were due to these patients having less severe disease. The two Asian biosimilar trials both reported less severe disease at baseline; their RP group also had greater response than the pivotal RP trials (Fig. 2). These differences were less evident for the three EMA/FDA-approved adalimumab biosimilars. However, it is worth noting that patients in the ABP 501 and BI 695501 trials were not all biologic naive and yet had comparable response rates to the biologic naive cohorts of pivotal trials (Fig. 3); response to a second TNFi is recognised to be poorer [59, 60]. Unfortunately, neither studies stated whether participants stopped previous bDMARDs due to inefficacy or AEs. There were also subtle differences in participant age, disease duration and HAQ (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Differences in patient characteristics between pivotal and biosimilar trials of adalimumab

Fig. 3.

Differences in ACR response rates for the reference product in pivotal and biosimilar trials

These subtle differences in trial characteristics, as well as minor discrepancies in rare safety signals, should be considered when drawing conclusions on the true biosimilarity of these agents. This has implications for switching between the RP and biosimilars. Unlike biosimilar infliximab and etanercept [61•], there are not many open label extension or pharmacovigilance studies for biosimilar adalimumab. In the SB5 trial, patients receiving the RP (n = 273) were rerandomised to switch to SB5 (n = 125) or to continue with the RP (n = 129) at week 24, until the end of the study at week 52. Switching had no impact on efficacy, safety or immunogenicity [62]. An open -abel extension to 72 weeks has been published in abstract form and reports no additional concerns [63, 64]. In the BI 695501 trial, patients receiving the RP (n = 321) were rerandomised at week 24 to switch to BI 695501 (n = 147) or remain on the RP (n = 148) until week 42 [48•]. A small subgroup of patients was followed up until week 58 to assess safety. Again, no differences were reported for efficacy, safety or immunogenicity.

However, these RCTs were not powered to show the significance of differences in rare AEs. In addition, trials have stringent inclusion and exclusion criteria that may not reflect real-world patients, such as those with comorbidities. Therefore, pharmacovigilance studies are essential to gather clinical evidence of the benefits and risks of switching in all patients. We refer the reader to reference [61•] for a more detailed discussion on biosimilar switching.

Conclusion

The year 2018 will see several biosimilars of adalimumab emerge in clinical practices worldwide. The three EMA/FDA-approved agents discussed in this review each have robust RCT evidence that meet pre-defined equivalence criteria, although subtle differences in clinical responses and AEs between the reference and biosimilar products were noted. As with TNFi biosimilars already on the market, real-world data and pharmacovigilance studies are critical to developing long-term evidence to provide assurances on efficacy as well as safety. These adalimumab biosimilars, and many more in the pipeline, will offer exciting opportunities in improving treatment access and increasing treatment options worldwide.

Conflict of Interest

RJM has received research grant funding, acted as a scientific advisor to or spoken at meetings sponsored by: Abbvie, AKL, Biogen, BMS, Chugai, Eli Lilly, Genzyme, Hospira, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Roche, Sandoz, Sanofi, UCB Pharma; funding includes both bio-originator and biosimiliar companies.

EM has received research grants, funding and has been an advisor for Abbvie, BMS, Gema, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Sandoz, Sanofi and Roche.

Sizheng Zhao and Laura Chadwick have no conflicts of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Biosimilars

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance

- 1.Kvien TK. Epidemiology and burden of illness of rheumatoid arthritis. PharmacoEconomics. 2004;22(2 Suppl 1):1–12. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200422001-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Markusse IM, Akdemir G, Dirven L, Goekoop-Ruiterman YP, van Groenendael JH, Han KH, et al. Long-term outcomes of patients with recent-onset rheumatoid arthritis after 10 years of tight controlled treatment: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(8):523–531. doi: 10.7326/M15-0919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sparks JA, Lin TC, Camargo CA, Jr, Barbhaiya M, Tedeschi SK, Costenbader KH, Raby BA, Choi HK, Karlson EW. Rheumatoid arthritis and risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthma among women: a marginal structural model analysis in the Nurses’ Health Study. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2018;47(5):639–648. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2017.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lundkvist J, Kastang F, Kobelt G. The burden of rheumatoid arthritis and access to treatment: health burden and costs. Eur J Health Econ. 2008;8(Suppl 2):S49–S60. doi: 10.1007/s10198-007-0088-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smolen JS, Landewe R, Bijlsma J, Burmester G, Chatzidionysiou K, Dougados M, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2016 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(6):960–977. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacobsson LT, Turesson C, Nilsson JA, Petersson IF, Lindqvist E, Saxne T, et al. Treatment with TNF blockers and mortality risk in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(5):670–675. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.062497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Listing J, Kekow J, Manger B, Burmester GR, Pattloch D, Zink A, Strangfeld A. Mortality in rheumatoid arthritis: the impact of disease activity, treatment with glucocorticoids, TNFalpha inhibitors and rituximab. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(2):415–421. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.AbbVie. AbbVie Reports Full-Year and Fourth-Quarter 2017 Financial Results 2018. https://news.abbvie.com/news/abbvie-reports-full-year-and-fourth-quarter-2017-financial-results.htm. Accessed April 2018.

- 9.European Medicines Agency. European public assessment report (EPAR) for Humira. 2017. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Summary_for_the_public/human/000481/WC500050865.pdf. Accessed April 2018.

- 10.World Health Organization. Guidelines on evaluation of monoclonal antibodies as similar biotherapeutic products (SBPs). 2016. http://www.who.int/biologicals/biotherapeutics/similar_biotherapeutic_products/en/. March 2017.

- 11.Salfield J, Kaymakcalan J, Tracey D, Roberts A, Kamen R. Generation of fully human anti-TNF antibody D2E7. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41(9):S57-S. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cvetkovic RS, Scott LJ. Adalimumab: a review of its use in adult patients with rheumatoid arthritis. BioDrugs. 2006;20(5):293–311. doi: 10.2165/00063030-200620050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moots RJ, Xavier RM, Mok CC, Rahman MU, Tsai WC, Al-Maini MH, et al. The impact of anti-drug antibodies on drug concentrations and clinical outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with adalimumab, etanercept, or infliximab: results from a multinational, real-world clinical practice, non-interventional study. PLoS One. 2017;12(4):e0175207. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keystone EC, Breedveld FC, van der Heijde D, Landewe R, Florentinus S, Arulmani U, Liu S, Kupper H, Kavanaugh A. Longterm effect of delaying combination therapy with tumor necrosis factor inhibitor in patients with aggressive early rheumatoid arthritis: 10-year efficacy and safety of adalimumab from the randomized controlled PREMIER trial with open-label extension. J Rheumatol. 2014;41(1):5–14. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.130543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weinblatt ME, Keystone EC, Furst DE, Kavanaugh AF, Chartash EK, Segurado OG. Long term efficacy and safety of adalimumab plus methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: ARMADA 4 year extended study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65(6):753–759. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.044404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van de Putte LB, Atkins C, Malaise M, Sany J, Russell AS, van Riel PL, Settas L, Bijlsma JW, Todesco S, Dougados M, Nash P, Emery P, Walter N, Kaul M, Fischkoff S, Kupper H. Efficacy and safety of adalimumab as monotherapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis for whom previous disease modifying antirheumatic drug treatment has failed. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63(5):508–516. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.013052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Breedveld FC, Weisman MH, Kavanaugh AF, Cohen SB, Pavelka K, van Vollenhoven R, et al. The PREMIER study: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind clinical trial of combination therapy with adalimumab plus methotrexate versus methotrexate alone or adalimumab alone in patients with early, aggressive rheumatoid arthritis who had not had previous methotrexate treatment. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(1):26–37. doi: 10.1002/art.21519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weinblatt ME, Keystone EC, Furst DE, Moreland LW, Weisman MH, Birbara CA, Teoh LA, Fischkoff SA, Chartash EK. Adalimumab, a fully human anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha monoclonal antibody, for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in patients taking concomitant methotrexate: the ARMADA trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(1):35–45. doi: 10.1002/art.10697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keystone EC, Kavanaugh AF, Sharp JT, Tannenbaum H, Hua Y, Teoh LS, Fischkoff SA, Chartash EK. Radiographic, clinical, and functional outcomes of treatment with adalimumab (a human anti-tumor necrosis factor monoclonal antibody) in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis receiving concomitant methotrexate therapy: a randomized, placebo-controlled, 52-week trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(5):1400–1411. doi: 10.1002/art.20217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Furst DE, Schiff MH, Fleischmann RM, Strand V, Birbara CA, Compagnone D, Fischkoff SA, Chartash EK. Adalimumab, a fully human anti tumor necrosis factor-alpha monoclonal antibody, and concomitant standard antirheumatic therapy for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: results of STAR (Safety Trial of Adalimumab in Rheumatoid Arthritis) J Rheumatol. 2003;30(12):2563–2571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smolen JS, Burmester GR, Combe B, Curtis JR, Hall S, Haraoui B, van Vollenhoven R, Cioffi C, Ecoffet C, Gervitz L, Ionescu L, Peterson L, Fleischmann R. Head-to-head comparison of certolizumab pegol versus adalimumab in rheumatoid arthritis: 2-year efficacy and safety results from the randomised EXXELERATE study. Lancet. 2016;388(10061):2763–2774. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31651-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fleischmann R, Mysler E, Hall S, Kivitz AJ, Moots RJ, Luo Z, DeMasi R, Soma K, Zhang R, Takiya L, Tatulych S, Mojcik C, Krishnaswami S, Menon S, Smolen JS, Adams L, Ally MM, du Plooy MC, Louw IC, Nayiager S, Nel CB, Nel D, Reuter H, Soloman AS, Spargo CE, Hall S, Rischmueller M, Sharma SD, Will RK, Youssef PP, Arroyo C, Baes RP, Dulos RB, Hao LT, Lanzon AE, Lichauco JJT, Mangubat JH, Ramiterre EB, Reyes BHM, Tan PP, Choe JY, Kang YM, Kwon SR, Lee SH, Lee SS, Yoo DH, Lin HY, Luo SF, Tsai ST, Tsai WC, Tseng JC, Wei CCC, Asavatanabodee P, Nantiruj K, Nilganuwong S, Uea-Areewongsa P, Majstorovic LB, Bacic SM, Batalov AZ, Georgieva-Slavcheva G, Mihailova M, Nikolov NG, Penev DP, Spasov YA, Stanimirova K, Todorov S, Toncheva AR, Yordanova N, Mosterova Z, Novosad L, Prochazkova L, Stehlikova H, Stejfova Z, Kiseleva N, Pank L, Savi T, Alexandra BG, Amital H, Mevorach D, Rosner IA, Mihailova A, Stumbra-Stumberga E, Basijokiene V, Lietuvininkiene V, Unikiene D, Brzezicki J, Dudek AM, Glowacka-Kulesz MB, Grabowicz-Wasko B, Hajduk-Kubacka S, Hilt J, Hrycaj P, Jeka S, Kolasa R, Krogulec M, Mastalerz H, Olak-Popko A, Owczarek E, Ruzga Z, Walczak A, Ancuta CI, Ancuta I, Balanescu AR, Berghea F, Bojin S, Arvunescu MAI, Ionescu RM, Mociran E, Pavel M, Rednic S, Voie A, Zainea CM, Bugrova OV, Demin A, Ershova OB, Gavrisheva IA, Krechikova DG, Kuropatkin GV, Marusenko IM, Menshikova IV, Noskov SM, Rebrov AP, Smakotina SA, Yakushin SS, Zhilyaev E, Ramos JJA, Garcia FJB, Nebro AF, Esteban SP, Burson JMS, Sala RS, Ataman S, Hizmetli S, Kuru O, Douglas KM, Emery P, Moots RJ, Ong VH, Sheeran TP, Faraawi RY, Lessard C, Mendoza CA, Avila-Armengol HE, Zapata FIA, Irazoque-Palazuelos FC, Cecena MAM, Pacheco-Tena CF, Rizo-Rodriguez JC, Rodriguez-Torres IM, Aelion JA, Caciolo BA, Calmes JM, Chatpar P, Dayal N, de Jesus A, Dikranian AH, Diri E, Fairfax MJ, Fenton IF, Fleischmann RM, Gaylis NB, George RL, Halter DG, Hernandez P, Hole SA, Hou AC, Huff JP, Kafaja S, Kennedy AC, Kenney H, Kimmel SC, Kirby BS, Kivitz AJ, Legerton CW, Lindsey SM, Mallepalli JR, Mathews SD, Metyas SK, Mizutani WT, Najam S, Nascimento JM, Pang SW, Patel RC, Poiley JE, Ramirez CE, Reddy R, Rehman Q, Schnitz WM, Scoville CD, Shergy WJ, Silverfield JC, Singhal AK, Smallwood-Sherrer YR, Songcharoen SN, Stack MT, Stohl W, Su TIK, Udell J, Waraich S, Weidmann CE, Wei N, Wiesenhutter CW, Winkler AE, Zagar KE, Berman A, Mysler EF, Hidalgo RAP, Venarotti HO, Sariego IAG, Calabresse REJ, Ruiz-Tagle JIV, Vargas LFMB, Berrocal AE, Portocarrero MGL, Jesus F, Pena R. Efficacy and safety of tofacitinib monotherapy, tofacitinib with methotrexate, and adalimumab with methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (ORAL strategy): a phase 3b/4, double-blind, head-to-head, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;390(10093):457–468. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31618-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weinblatt ME, Schiff M, Valente R, van der Heijde D, Citera G, Zhao C, Maldonado M, Fleischmann R. Head-to-head comparison of subcutaneous abatacept versus adalimumab for rheumatoid arthritis: findings of a phase IIIb, multinational, prospective, randomized study. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(1):28–38. doi: 10.1002/art.37711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Porter D, van Melckebeke J, Dale J, Messow CM, McConnachie A, Walker A, Munro R, McLaren J, McRorie E, Packham J, Buckley CD, Harvie J, Taylor P, Choy E, Pitzalis C, McInnes IB. Tumour necrosis factor inhibition versus rituximab for patients with rheumatoid arthritis who require biological treatment (ORBIT): an open-label, randomised controlled, non-inferiority, trial. Lancet. 2016;388(10041):239–247. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00380-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singh JA, Christensen R, Wells GA, Suarez-Almazor ME, Buchbinder R, Lopez-Olivo MA, et al. A network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of biologics for rheumatoid arthritis: a Cochrane overview. CMAJ. 2009;181(11):787–796. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.091391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jorgensen TS, Turesson C, Kapetanovic M, Englund M, Turkiewicz A, Christensen R, et al. EQ-5D utility, response and drug survival in rheumatoid arthritis patients on biologic monotherapy: a prospective observational study of patients registered in the south Swedish SSATG registry. PLoS One. 2017;12(2):e0169946. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hetland ML, Christensen IJ, Tarp U, Dreyer L, Hansen A, Hansen IT, et al. Direct comparison of treatment responses, remission rates, and drug adherence in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with adalimumab, etanercept, or infliximab: results from eight years of surveillance of clinical practice in the nationwide Danish DANBIO registry. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(1):22–32. doi: 10.1002/art.27227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burmester GR, Lin Y, Patel R, van Adelsberg J, Mangan EK, Graham NM, et al. Efficacy and safety of sarilumab monotherapy versus adalimumab monotherapy for the treatment of patients with active rheumatoid arthritis (MONARCH): a randomised, double-blind, parallel-group phase III trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(5):840–847. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gabay C, Emery P, van Vollenhoven R, Dikranian A, Alten R, Pavelka K, Klearman M, Musselman D, Agarwal S, Green J, Kavanaugh A. Tocilizumab monotherapy versus adalimumab monotherapy for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (ADACTA): a randomised, double-blind, controlled phase 4 trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9877):1541–1550. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60250-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taylor PC, Keystone EC, van der Heijde D, Weinblatt ME, Del Carmen ML, Reyes Gonzaga J, et al. Baricitinib versus placebo or adalimumab in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(7):652–662. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1608345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Food and Drug Administration. Scientific Considerations in Demonstrating Biosimilarity to a Reference Product. 2015. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/ucm290967.htm. March 2017.

- 32.European Medicines Agency. Guideline on similar biological medicinal products containing biotechnology-derived proteins as active substance: non-clinical and clinical issues. 2015 http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/regulation/general/general_content_000408.jsp. March 2017.

- 33.Genovese MC, Glover J, Matsunaga N, Chisholm D, Alten R. Efficacy, safety and immunogenicity in randomized, double-blind (DB) and open label extension (OLE) studies comparing FKB327, an adalimumab biosimilar, with the adalimumab reference product (Humira (R); RP) in patients (pts) with active rheumatoid arthritis (RA) Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69:2. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alten R, Glover J, Matsunaga N, Chisholm D, Genovese M. Efficacy and safety results of a phase iii study comparing FKB327, an adalimumab biosimilar, with the adalimumab reference product in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:59. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-eular.2220. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blauvelt A, Lacour JP, Fowler J, Schuck E, Jauch-Lembach J, Balfour A, et al. Long-term efficacy, safety and immunogenicity results from a randomized, double-blind, phase III confirmatory efficacy and safety study comparing GP2017, a proposed biosimilar, with reference adalimumab. Arthritis Rheum. 2017;69:4. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sandoz. Sandoz proposed biosimilars adalimumab and infliximab accepted for regulatory review by the European Medicines Agency. 2017. https://www.sandoz.com/news/media-releases/sandoz-proposed-biosimilars-adalimumab-and-infliximab-accepted-regulatory-review. Apri 2018.

- 37.Jamshidi A, Gharibdoost F, Vojdanian M, Soroosh SG, Soroush M, Ahmadzadeh A, Nazarinia MA, Mousavi M, Karimzadeh H, Shakibi MR, Rezaieyazdi Z, Sahebari M, Hajiabbasi A, Ebrahimi AA, Mahjourian N, Rashti AM. A phase III, randomized, two-armed, double-blind, parallel, active controlled, and non-inferiority clinical trial to compare efficacy and safety of biosimilar adalimumab (CinnoRA(R)) to the reference product (Humira(R)) in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2017;19(1):168. doi: 10.1186/s13075-017-1371-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jani RH, Gupta R, Bhatia G, Rathi G, Ashok Kumar P, Sharma R, Kumar U, Gauri LA, Jadhav P, Bartakke G, Haridas V, Jain D, Mendiratta SK. A prospective, randomized, double-blind, multicentre, parallel-group, active controlled study to compare efficacy and safety of biosimilar adalimumab (Exemptia; ZRC-3197) and adalimumab (Humira) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Rheum Dis. 2016;19(11):1157–1168. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.12711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Business Standard. Torrent launches world's second biosimilar of generic auto-immune drug. 2016. http://www.business-standard.com/article/companies/torrent-launches-world-s-second-biosimilar-of-generic-auto-immune-drug-116011100615_1.html. April 2018.

- 40.Kaur P, Chow V, Zhang N, Moxness M, Kaliyaperumal A, Markus R. A randomised, single-blind, single-dose, three-arm, parallel-group study in healthy subjects to demonstrate pharmacokinetic equivalence of ABP 501 and adalimumab. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(3):526–533. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Velayudhan J, Chen YF, Rohrbach A, Pastula C, Maher G, Thomas H, Brown R, Born TL. Demonstration of functional similarity of proposed biosimilar ABP 501 to adalimumab. BioDrugs. 2016;30(4):339–351. doi: 10.1007/s40259-016-0185-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu J, Eris T, Li C, Cao S, Kuhns S. Assessing analytical similarity of proposed Amgen biosimilar ABP 501 to adalimumab. BioDrugs. 2016;30(4):321–338. doi: 10.1007/s40259-016-0184-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Papp K, Bachelez H, Costanzo A, Foley P, Gooderham M, Kaur P, Narbutt J, Philipp S, Spelman L, Weglowska J, Zhang N, Strober B. Clinical similarity of biosimilar ABP 501 to adalimumab in the treatment of patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: a randomized, double-blind, multicenter, phase III study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(6):1093–1102. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cohen S, Genovese MC, Choy E, Perez-Ruiz F, Matsumoto A, Pavelka K, et al. Efficacy and safety of the biosimilar ABP 501 compared with adalimumab in patients with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis: a randomised, double-blind, phase III equivalence study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(10):1679–1687. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.European Medicines Agency. European public assessment report: SOLYMBIC. 2017. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Public_assessment_report/human/004373/WC500225367.pdf. Accessed April 2018.

- 46.European Medicines Agency. European public assessment report: AMGEVITA. 2017. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Public_assessment_report/human/004212/WC500225231.pdf. Accessed April 2018.

- 47.Wynne C, Altendorfer M, Sonderegger I, Gheyle L, Ellis-Pegler R, Buschke S, Lang B, Assudani D, Athalye S, Czeloth N. Bioequivalence, safety and immunogenicity of BI 695501, an adalimumab biosimilar candidate, compared with the reference biologic in a randomized, double-blind, active comparator phase I clinical study (VOLTAIRE(R)-PK) in healthy subjects. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2016;25(12):1361–1370. doi: 10.1080/13543784.2016.1255724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.• Cohen SB, Alonso-Ruiz A, Klimiuk PA, Lee EC, Peter N, Sonderegger I, et al. Similar efficacy, safety and immunogenicity of adalimumab biosimilar BI 695501 and Humira reference product in patients with moderately to severely active rheumatoid arthritis: results from the phase III randomised VOLTAIRE-RA equivalence study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018; 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212245. This is large, high quality randomised controlled trial of an adalimumab biosimilar [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.European Medicines Agency. European public assessment report: Cyltezo. 2017. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Public_assessment_report/human/004319/WC500238609.pdf. Accessed April 2018.

- 50.Shin D, Lee Y, Kim H, Körnicke T, Fuhr R. A randomized phase I comparative pharmacokinetic study comparing SB5 with reference adalimumab in healthy volunteers. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2017;42:672–678. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.12583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weinblatt ME, Baranauskaite A, Niebrzydowski J, Dokoupilova E, Zielinska A, Jaworski J, et al. Phase III randomized study of SB5, an adalimumab biosimilar, versus reference adalimumab in patients with moderate-to-severe rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2018;70(1):40–48. doi: 10.1002/art.40336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.European Medicines Agency. European public assessment report: Imraldi. 2017. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Public_assessment_report/human/004279/WC500233922.pdf. Accessed April 2018.

- 53.Griffiths CEM, Thaci D, Gerdes S, Arenberger P, Pulka G, Kingo K, et al. The EGALITY study: a confirmatory, randomized, double-blind study comparing the efficacy, safety and immunogenicity of GP2015, a proposed etanercept biosimilar, vs. the originator product in patients with moderate-to-severe chronic plaque-type psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176(4):928–938. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Leonardi CL, Powers JL, Matheson RT, Goffe BS, Zitnik R, Wang A, Gottlieb AB, Etanercept Psoriasis Study Group Etanercept as monotherapy in patients with psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(21):2014–2022. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tyring S, Gottlieb A, Papp K, Gordon K, Leonardi C, Wang A, Lalla D, Woolley M, Jahreis A, Zitnik R, Cella D, Krishnan R. Etanercept and clinical outcomes, fatigue, and depression in psoriasis: double-blind placebo-controlled randomised phase III trial. Lancet. 2006;367(9504):29–35. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67763-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Menter A, Tyring SK, Gordon K, Kimball AB, Leonardi CL, Langley RG, Strober BE, Kaul M, Gu Y, Okun M, Papp K. Adalimumab therapy for moderate to severe psoriasis: a randomized, controlled phase III trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(1):106–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Saurat JH, Stingl G, Dubertret L, Papp K, Langley RG, Ortonne JP, Unnebrink K, Kaul M, Camez A, for the CHAMPION Study Investigators Efficacy and safety results from the randomized controlled comparative study of adalimumab vs. methotrexate vs. placebo in patients with psoriasis (CHAMPION) Br J Dermatol. 2008;158(3):558–566. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Moots Robert J., Curiale Cinzia, Petersel Danielle, Rolland Catherine, Jones Heather, Mysler Eduardo. Efficacy and Safety Outcomes for Originator TNF Inhibitors and Biosimilars in Rheumatoid Arthritis and Psoriasis Trials: A Systematic Literature Review. BioDrugs. 2018;32(3):193–199. doi: 10.1007/s40259-018-0283-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Smolen JS, Kay J, Doyle MK, Landewe R, Matteson EL, Wollenhaupt J, et al. Golimumab in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis after treatment with tumour necrosis factor alpha inhibitors (GO-AFTER study): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial. Lancet. 2009;374(9685):210–221. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60506-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Karlsson JA, Kristensen LE, Kapetanovic MC, Gulfe A, Saxne T, Geborek P. Treatment response to a second or third TNF-inhibitor in RA: results from the South Swedish Arthritis Treatment Group Register. Rheumatology. 2008;47(4):507–513. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Moots R, Azevedo V, Coindreau JL, Dorner T, Mahgoub E, Mysler E, et al. Switching between reference biologics and biosimilars for the treatment of rheumatology, gastroenterology, and dermatology inflammatory conditions: considerations for the clinician. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2017;19(6):37. doi: 10.1007/s11926-017-0658-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Weinblatt ME, Baranauskaite A, Dokoupilova E, Zielinska A, Jaworski J, Racewicz A, Pileckyte M, Jedrychowicz-Rosiak K, Baek I, Ghil J. Switching from reference adalimumab to SB5 (adalimumab biosimilar) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: fifty-two-week phase III randomized study results. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70:832–840. doi: 10.1002/art.40444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cohen S, Pablos JL, Wang H, Muller GA, Kivitz A, Matsumoto A, et al. ABP 501 biosmilar to adalimumab: final safety, immunogenicity, and efficacy results from an open-label extension study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:834–835. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-eular.3288. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cohen S, Pablos JL, Zhang N, Rizzo W, Muller G, Padmanaban D, et al. ABP 501 long-term safety/efficacy: interim results from an open-label extension study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:2. [Google Scholar]