Abstract

There are limited studies on heart failure in Indian population

Objective

Present study aimed to assess the in-hospital 90-day and two year outcomes in patients with ischemic (IHD-HF) and non ischemic heart failure (NIHD-HF).

Methods

Patients with NYHA Class III & IV, who were admitted to our intensive care unit with heart failure (HF), were evaluated and followed up for 2 years.

Results

In our cohort of 287 patients, there were 192 (66.9%) males and 95 (33.1%) females. Patients were divided into IHD-HF of 180 (62.7%) patients and NIHD-HF of 107 (37.3%) patients. Mean age of IHD-HF group was 66 (+/−10) and in the NIHD-HF group was 61 (+/−11). Prevalence of HF increased with age in the IHD-HF population and there was no relation with age in the NIHD-HF population .Patients readmitted within 90 days in the IHD-HF were 56 % (n−101) and in the NIHD-HF were 32.7 % (n-35) [p- 0.001]. Two- year recurrent admissions were 69.4 % (n-125) in the IHD-HF patients and 52.3 % (n-56) in the NIHD-HF patients, respectively (p-0.004). Mortality at 90 days in the IHD-HF patients was 26.6 % (n-48) and in NIHD-HF patients were 14.9 % (n-16) [p- 0.021]. Two-year mortality was 42.3 % (n-76) in the IHD-HF patients and 29.9 %(n-32) in the NIHD-HF patients, respectively (p-0.037).

Conclusions

HF in IHD-HF heralds a bad prognosis with recurrent hospitalizations and high mortality when compared to patients with NIHD-HF.

Keywords: Heart failure, Recurrent admissions, Mortality

1. Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is a common cardiovascular condition with increasing incidence and prevalence.1 Mortality rates of HF approach 20% per year in spite of the current medical therapy, and nearly one million patients are hospitalized with congestive HF annually in the United States alone.2 With the increasing longevity of Indian population, HF incidence is increasing with its attendant high mortality and morbidity. Despite advances in the treatment, chronic HF with systolic dysfunction, remain at high risk for re-hospitalization and higher mortality.3 This may be attributed to the aging of the population, progressive disease, and persistently high event rates. Up to 30% of patients experience a serious adverse cardiovascular event after every hospital admission for HF.4 The present study was to assess the in-hospital 90-day and two- year outcomes in patients with ischemic heart failure (IHD-HF) and non-ischemic heart failure (NIHD-HF) and the factors associated with re admissions and mortality.

2. Methods

2.1. Study population

This was a prospective descriptive study done at the Kerala Institute of Medical Sciences, Trivandrum, over a 2 year period from 1st June 2012. A cohort of 287 patients with chronic HF, who were admitted to our intensive care unit above the age of 40 were selected, as there were few patients below these age groups. Those who were not willing to provide informed consent were excluded. Diagnosis of HF was made by Framingham criteria 5 and by assessing left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) with echocardiography by biplane Simpson's method.6 Patients were evaluated clinically and all of them underwent routine cardiac investigations, including cardiac biomarkers and echocardiography. Follow-up of the patients were done by hospital visits and/or through telephone.

2.2. Follow-up

The patients were reevaluated at 90 days and 2 years, by revisit in outpatient department, by subsequent readmissions and through telephonic calls

2.3. Definitions

2.3.1. Ischemic heart failure (IHD-HF)

Heart failure patients admitted with a history of chronic stable angina or acute coronary syndrome or with evidence of significant coronary artery disease by coronary angiogram were labeled as IHD-HF.

2.3.2. Non ischemic heart failure (NIHD-HF)

Patients with dilated cardiomyopathy, valvular heart disease,hypertensive heart disease, cor pulmonale, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, primary pulmonary hypertension, drug induced cardiomyopathy, congenital heart disease and restrictive cardiomyopathies were labeled as NIHD-HF.

2.3.3. Optimal medical management

The “optimal” medical management was defined as a combination of beta blockers, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI) or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB), and aldosterone receptor blockers in patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction (LVSD, EF <45%).7 This was in addition to diuretics and digoxin, as and when necessary.

2.4. Statistical methods

The categorical variables were presented as proportions, and continuous variables as means with standard deviation (SD) or as median with inter-quartile range (IQR). Chi-square test applied to find the association between categorical variables among the two groups. The multivariate model included all covariates which were ‘significant’ (p < 0.05) in the univariate analysis. The final model included demographic variables (age and sex), baseline comorbidities (diabetes, hypertension, pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, and stroke), etiology of HF, behavioral risk factors (tobacco use), ejection fraction and optimal treatment status. Analyses were carried out using the statistical software's (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) SPSS Version 16.0 and STATISTICA.

3. Results

3.1. Age and gender wise distribution of patients

A total of 287 patients were analyzed, there were 192 (66.9%) males and 95 (33.1%) females. There were 180 (62.7%) patients with IHD-HF and 107 (37.3%) patients with NIHD-HF. The mean age of the IHD-HF patients was 66 (+/−10) and in the NIHD-HF patients were 61(+/−11).

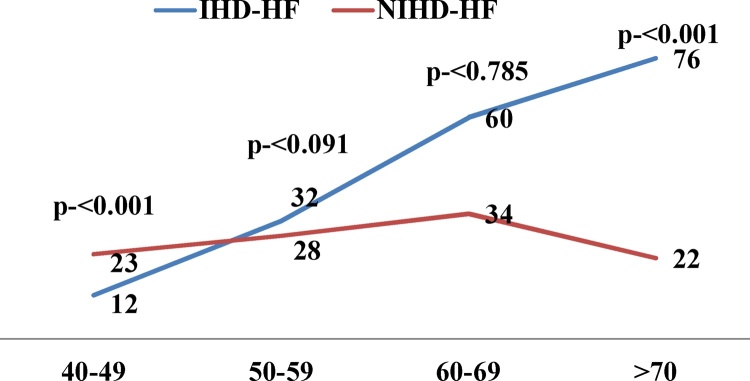

Males predominated in the IHD-HF group (n- 140/77.7%) and females predominated in the NIHD-HF group (n-55/51.5%). Patients were divided into 4 age group intervals ranging from 40 to 90 years. Prevalence of heart failure increased with advancing age in IHD-HF group, while it likely decreased in NIHD-HF group. (Fig. 1). In this cohort, 174 (60.6%) patients were in the NYHA functional class four and rest of the 113 (39.4%) patients was in functional class three.

Fig. 1.

Showing the age wise distribution of patients.

3.2. Etiology of chronic heart failure

In IHD-HF patients with history of old STEMI was the primary diagnosis in 116 (64.4%) patients and history of old NSTEMI in 64 (35.6%) patients. In the STEMI patients, only 14 (7.8%) had primary PCI and 9 (5%) had rescue PCI. Thrombolytic therapy was received by 19 (10.6%) patients. The interval between the first medical contact to the interventionist varied from 1 h to 24 h. Diagnostic angiogram was performed in all patients with coronary artery disease. Triple vessel disease was present in 121 (67.3%) patients, double vessel disease in 37 (20.5%) and single vessel disease in 22 (12.2) patients. Coronary artery bypass graft was done in 38 (21.1%) patients, angioplasty in 67 (37.3%) patients and 75 (41.6%) patients were on medical management. Medical management was instituted in 75 (41.6%) patients, of whom 11 (6.1%) patients had severe diffused triple vessel disease and 64 (35.5%) patients did not give consent for any interventional management. All IHD-HF patients had reduced ejection fraction.

NIHD-HF patients (Table 2) includes, dilated cardiomyopathy (n-36), valvular heart disease (n-21), heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) which includes hypertensive heart disease (n-13) and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (n-6), cor pulmonale (n-13), primary pulmonary hypertension (n-6), drug induced (n-6), restrictive cardiomyopathies (n-3) and congenital heart diseases (n-3).

Table 2.

Etiology of heart failure.

| Etiology | n(%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| IHD- HF | 180 (62.7) | ||

| NIHD- HF n-107 (37.3%) | a-dilated cardiomyopathy | 36 (12.6) | |

| b-valvular heart disease | 21 (7.4) | ||

| c- HFpEF | 1-hypertensive heart disease | 13 (4.5) | |

| 2-Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | 6 (2.1) | ||

| d- Cor pulmonale | 13 (4.5) | ||

| e- Chemotherapy induced | 6 (2.1) | ||

| f- Primary PAH | 6 (2.1) | ||

| g- Restrictive cardiomyopathy | 3 (1.0) | ||

| h- Congenital heart disease | 3 (1.0) | ||

| Total | 287 (100) | ||

3.3. Co morbid factors in IHD-HF and NIHD-HF patients

IHD-HF patients had significant increase in incidence of diabetes, systemic hypertension and dyslipidemia as described in literature. The risk factors were directly related to the development of IHD-HF. There were 133 (73.9%) patients with diabetes mellitus in IHD-HF patients and 57(53.3%) patients in NIHD-HF (p- < 0.001). Systemic hypertension was found in 117 (65%) in IHD-HF patients, compared with 50 (46.7%) in the NIHD-HF patients (p-0.002), chronic renal disease in 91 (50.6%) patients in IHD-HF patients and 32 (29.9%) in the NIHD-HF patients (p- < 0.001). Dyslipidemia in 131 (72.8%) patients in IHD-HF and 44 (41.1%) in the NIHD-HF patients (p- <0.001). Levels of high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol (38 ± 8.8) remains low in IHD-HF patients. Smokers were more in IHD-HF patients ie 81 (45%) and in NIHD-HF patients, it was 29 (27.1%) (p- 0.003).

3.4. Hospital stay, re-admissions and mortality

There was no significant difference in duration of hospital stay in both groups (7 ± 8 days, 7 ± 5 days). In IHD-HF group, 101 (56.1%) patients were readmitted at 90 days and 125 (69.4%) patients at 2 years. However, only 35 (32.7) patients were readmitted at 90 days and 56 (52.3) patients at 2 years in NIHD-HF group. Ninety days mortality was significantly higher in IHD-HF patients (p-0.021) (Table 3). This trend continued for our follow-up till 2 years (p-0.037). There were 19 (6.6) HF patients with preserved ejection fraction; among them 9 patients expired in the two year follow up. Mean EF of entire cohort was 37.4% (±10.2), mean EF of IHD-HF was 32.9% (±4.48) and mean EF of NIHD-HF was 44.9%(±12.4). Mean EF of patients who died was 30.5% (±2.6) and who survived was 32.9% (±5.0) in the IHD-HF group (p- 0.64).

Table 3.

Mortality of patients with heart failure.

| Duration | Expired | 1st group (n-180) (IHD-HF) n (%) | 2nd group (n-107) (NIHD-HF) n (%) | Total n-287 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 90 days | In hospital | 19 (10.6) | 4 (3.8) | 23 (8.01) | 0.039 |

| Out of hospital | 29 (16.1) | 12 (11.2) | 41 (14.3) | 0.253 | |

| 2 years | In hospital | 31 (17.2) | 6 (5.6) | 37 (12.9) | 0.004 |

| Out of hospital | 45 (25.0) | 26 (24.3) | 71 (24.7) | 0.894 |

3.5. 90 days and 2 yrs in and out of hospital mortality of patients with IHD-HF and NIHD-HF

Death appeared to be occurring at homes, where prompt medical care is not available. It was surprising to find that mortality in IHD-HF patients on 2 year follow-up was significantly more due to the complex scenario in which they were admitted at 2 years. NT Pro BNP levels were done in all patients at the time of admission. The mean NT Pro BNP levels (Table 1) were higher in patients with IHD-HF (p- < 0.001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with heart failure in our study.

| 1 group (n-180) [IHD-HF] | 2 group (n107) (NIHD-HF) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 67 (60–74) | 61(50–68) | <0.001 |

| Мale | 66 ± 10 (57–72) | 60 ± 12.5(50 69) | <0.001 |

| Female | 73 ± 7.6 (67–75) | 62 ± 11(51–67) | <0.001 |

| HB | 12.1(10.4–13.7) | 12.4 (10.7–14.1) | 0.060 |

| HbA1C | 7,8(6,8–9,8) | 7,1(6,3–7,4) | <0.001 |

| NT Pro BNP | 5971(3872;18913) | 3524(2395;8900) | <0.001 |

| Trop T Hs | 39(23;66) | 22(14;35) | <0.001 |

| Total cholesterol | 156(134;176) | 156(123;177) | 0.867 |

| Triglycerides | 96(77;121) | 88(71;113) | 0.013 |

| HDL | 38(33;44) | 44(38;52) | <0.001 |

| LDL | 90(74;110) | 92(75;114) | 0.630 |

| Serum Createnine | 1,4(1,0;2,0) | 1,1(0,9;1,8) | 0.001 |

| GFR | 88(78–94) | 94(92–95) | <0.001 |

| Ejection fraction | 32.9% (±4.48) | 44.9%(±12.4). | <0.001 |

3.6. Causes for re-admissions

The common causes of readmissions in IHD-HF patients were due to the worsening of HF (21.1%) and renal failure (12.7%). However, pneumonia (14.9%) became a complicating factor in NIHD-HF patients. In addition to this, multiple co morbidities were present at the time of readmissions in both groups.

3.7. Optimal medical therapy (OMT) of patients with heart failure

Optimal medical therapy could not be given due to co morbidities. Among the IHD-HF group, 33(18.4%) patients could be given OMT and in NIHD-HF patients, only 19 (17.8%) received OMT. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) was implanted in 6 (3.3%) patients, in which 2 patients expired on a two year follow-up. In IHD-HF there were 20 patients with left bundle branch block (LBBB) (QRS >120 ms) of whom 15 patients expired on a 2 year follow-up. In NIHD-HF patients, 6 patients had LBBB, in whom 2 patients expired on 2 year follow-up. None of them was prepared for cardiac resynchronized therapy.

Loop diuretics were received by 156 (86.6%) patients in IHD-HF and 98 (88.7%) in NIHD-HF patients (p-0.60). Spironolactone was received in 72 (40.0%) and 34 (31.7%) patients in IHD-HF and NIHD-HF groups respectively (p -0.16). Beta-blockers were prescribed to 88 (48.8%) patients in IHD-HF and to 64 (35.5%) patients in NIHD-HF (p-0.02). ACE/ARBs were given more in the NIHD-HF patients than IHD-HF i.e. 51 (47.6%) and 64 (35.5%) patients, respectively (p-0.043). There were limitations in giving optimal medical therapy for patients with HF due to multiple co-morbidities like renal failure in 32.1% (n-92), hypotension in 32.4% (n-93), bradycardia in 7.7% (n-22), bronchial asthma in 6.6% (n-19) and COPD in 3.1% (n-9) of patients. In IHD-HF patients, 39 (21.7%) patients received Vitamin K antagonists. The indication was atrial fibrillation in 22 (12.2%) patients and left ventricular (LV) apical thrombus in 17 (9.5%) patients.

4. Discussion

This is the largest single-center report of cardiac failure of 287 patients followed up for a period of 2 years from India. Etiology of HF could be due to many diseases existing in the same patient. However, it is easy to identify one among them as the primary cause of HF. In the Framingham study, hypertension appears to be the most common cause of HF. Primary cause in 30% in men and 20% of women, and a co-factor in a further 33% and 25%, respectively.8 In our series, we found that the common cause of HF is ischemic heart disease (IHD). It came as a surprise for us that systemic hypertension formed only 4.5% (n-13) as a single etiology of HF in our study. But as a co- factor, it presents in 58.2% (n-167) in our cohort of 287 patients. It should be noted that 65% (n-117) of patients with IHD, systemic hypertension was present.

Our patients were younger with a male predominance in ischemic group and there was no significant gender difference in non ischemic patients. In a study by Kirkwood F et al women were older than men when the primary etiology was ischemic heart disease but ages were similar in patients with a non ischemic etiology.9 We also observed similar findings. Mean age of women in IHD-HF (Table 1) was 73 (+/−7) and men was 66 (+/−10) and in the NIHD-HF the mean age of women was 62 (+/−11) and men was 60 (+/−12).

A recent HF study by Seth et al reported a mortality of 30.8% when they followed up to 6 months in northern part of India.10 The 90 days total in-hospital mortality in Trivandrum HF registry (South India) was 8.46%,11 it is almost similar to (8.01%) our study. In Trivandrum HF registry they didn’t mention the out of hospital mortality of their patients, but this was more at 90 days as well as two years in our study. This study was conducted in an urban tertiary care center with highly compliance patients, but in peripheral centers, mortality may be higher than this. In the Spanish HF study (MUSIC), the mortality was 26.9% when they followed the patients for 44 months.12 Ferran Pons et al13 in 3 years period, recorded a mortality of about 30%. The mortality remains higher 37.6% (n-108) in our population when we followed up these patients for two years. Rotterdam study in Europe showed 1-year and 5-year mortality rate of 11% and 41%, respectively.14 This higher mortality in our patients may be because 64 patients in IHD-HF refused intervention and 11 patients with triple vessel disease refused coronary artery bypass surgery. All patients in our study belonged to functional class three and four by NYHA. HF with preserved ejection fraction included patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and hypertensive heart disease. This group of patients had the higher possibilities of sudden cardiac death due to higher incidence of fatal arrhythmias.15,16

Many large mortality trials in HF reported that mortality was lower in patients with NIHD-HF than in those with IHD-HF. Franciosa et al reported a mortality rate in patients with coronary artery disease of 46% and 69% at 1 and 2 years, compared with 23% and 48% at 1 and 2 years in those with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy (p < 0.01).17 In V-HeFT-I trial 18 the mortality in the IHD patients was 57% and in the NIHD-HF patients were 46% when they were followed for 2.3 years. In PROMISE trial 19 for a follow-up of 6.1 months the mortality in the ischemic and non IHD patients were 27% and 20%, respectively.

During follow up of 90 days and 2 years in our study the mortality of IHD-HF was 26.6% and 42.2% and in the NIHD-HF group, it was 14.9% and 29.9% respectively. But the non ischemic etiology differs from the others (they included only idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy). The mortality in ischemic group is higher in our population and that is probably because of the late presentation to hospital after myocardial infarction.20 .Among the 180 patients with ischemic heart disease, 117 (64.5%) patients had history of old STEMI and 64 (35.5%) patients had history of old NSTEMI.

Duration of hospital stay is 3–5 days longer than ADHERE 21 and the OPTIMIZE 22 HF registries and almost similar to Trivandrum heart failure registry. In some of the pivotal trials of ACE inhibitors in HF23,24 there was a more favorable effect on mortality in NIHD-HF than in IHD-HF. ACE/ARBs were received more in the non-ischemic group (p-0.043) in our study group. Majority of IHD-HF patient could not receive these drugs because of renal failure and hypotension. Clinical trials have shown that beta-blockers improve hemodynamics, LV function and clinical status in patients with HF of ischemic or non ischemic etiology.25 In our analysis, beta-blockers were received more in IHD-HF patients than in NIHD-HF patients (p- 0.02). Our patients were more of advanced HF; they were in functional class NYHA 3 and 4. Hence, the mortality was high.

5. Conclusion

Mortality was high in our population compared to other HF registries. Out- of- the hospital mortality was high in both groups. Optimal medical therapy could not be given due to co morbidities in our subjects. IHD-HF patients had a worse prognosis than NIHD-HF as their initial treatment was often delayed due to social problem. When they develop HF, co-morbidities prevent the use of beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers and aldosterone receptor antagonists.

In a country like India, patient education and health awareness programs has an important role to play in seeking early medical management and interventional treatment. Government should take the necessary steps in rural and urban areas for early detection of patients who presents with myocardial infarction and should give prompt treatment at the right time. Government should also start preventive clinics for reducing this universal burden of IHD and HF.

6. Limitations

We took only patients above the age of 40 years because we had very few patients admitted with HF in our tertiary care center during that period.

Conflict of interest

None

Contributor Information

Suman O.S., Email: suman_os@yahoo.com.

Vijayaraghavan G., Email: drvijayaraghavan@gmail.com.

Muneer A.R., Email: dr.reenum@yahoo.com.

Ramesh N., Email: natarajanramesh79@gmail.com.

Harikrishnan S., Email: drharikrishnan@outlook.com.

Kalyagin A.N., Email: akalagin@yandex.ru.

References

- 1.Yusuf S., Pitt B. A lifetime of prevention the case of heart failure. Circulation. 2002;106:2997–2998. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000046804.13847.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lloyd-Jones D. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2010 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;121:46–215. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lloyd-Jones D., Adams R., Carnethon M. American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2009 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2009;119:480–486. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.191259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Connor C.M., Stough W.G., Gallup D.S., Hasselblad V., Gheorghiade M. Demographics, clinical characteristics, and outcomes of patients hospitalized for decompensated heart failure: observations from the IMPACT-HF registry. J Card Fail. 2005;11:200–205. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2004.08.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McKee P.A., Castelli W.P. The natural history of congestive heart failure: theFramingham study. N Engl J Med. 1971;285(26):1441–1446. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197112232852601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Otterstad J.E. Measuring left ventricular volume and ejection fraction with the biplane Simpson's method. Heart. 2002;88:559–560. doi: 10.1136/heart.88.6.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vahanian A., Alfieri O. Guidelines on the management of valvular heart disease (version 2012): the joint task force on the management of valvular heart disease of the european society of cardiology (ESC) and the european association for cardio-thoracic surgery (EACTS) Eur Heart J. 2012;33(19):2451–2496. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.John McMurray J., Stewart Simon. Epidemiology, aetiology, and prognosis of heart failure. Heart. 2000;83:596–602. doi: 10.1136/heart.83.5.596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adams Kirkwood F., Jr., Stephanie M.D., Dunlap H. Relation between gender, etiology and survival in patients with symptomatic heart failure. JACC. 1996;28(7):1781–1788. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(96)00380-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seth Sandeep, Khanal Suraj, Sivasubramanian Sivasubramanian, Gupta Namit, Bahl Vinay K. Epidemiology of acute decompensated heart failure in India: the AFAR study (Acute failure registry study) JPCS. 2015;2:35–38. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harikrishnan S., Sanjay G., Anees T. Trivandrum heart failure registry. clinical presentation, management, in-hospital and 90-day outcomes of heart failure patients in Trivandrum, Kerala, India : the trivandrum heart failure registry. Eur J Heart Fail. 2015;17(8):794–800. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vazquez R., Bayes-Genis A., Cygankiewicz I. MUSIC Investigators: the MUSIC Risk score: a simple method for predicting mortality in ambulatory patients with chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:1088–1096. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pons Ferran. Mortality and cause of death in patients with heart failure: findings at a specialist multidisciplinary heart failure unit. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2010;63:303–313. doi: 10.1016/s1885-5857(10)70063-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bleumink G.S. Quantifying the heart failure epidemic: prevalence, incidence rate, lifetime risk and prognosis of heart failure. The Rotterdam study. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:1614–1619. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghali Jalal K., Kadakia Sunil, Cooper Richard S., Liao Youlian. Impact of left ventricular hypertrophy on ventricular arrhythmias In the absence of coronary artery disease. JACC. 1991;17(May (6)):1277–1282. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(10)80135-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elliott P.M., GimenoBlanes J.R., Mahon N.G., Poloniecki J.D., McKenna W.J. Relation between severity of left-ventricular hypertrophy and prognosis in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Lancet. 2001;357:420–424. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Franciosa J.A., Wilen M., Ziesche S., Cohn J.N. Survival in men with severe chronic left ventricular failure due to either coronary heart disease or idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 1983;51:831–836. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(83)80141-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohn J., Aichibald D.G., Ziesche S. Effect of vasodilator therapy on mortality in chronic congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1986;314 doi: 10.1056/NEJM198606123142404. 1547–. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Packer M., Carver R., Rodeheffer Effect of oral milrinone on mortality in severe chronic heart failure. The PROMISE study research group. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1468–1475. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199111213252103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mohanan P.P., Mathew R., Harikrishnan S. Kerala ACS registry investigators. presentation, management, and outcomes of 25 748 acute coronary syndrome admissions in Kerala, India : results from the Kerala ACS registry. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(2):121–129. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adams K.F., Fonarow G.C., Emerman C.L. Characteristics and outcomes of patients hospitalized for heart failure in the United States: rationale, design, and preliminary observations from the first 100,000 cases in the Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry (ADHERE) Am Heart J. 2005;149(February (2)):209–216. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abraham W.T., Fonarow G.C., Albert N.M. Predictors of in-hospital mortality in patients hospitalized for heart failure: insights from the organized program to initiate lifesaving treatment in hospitalized patients with heart failure (OPTIMIZE-HF) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008 Jul 29;52(5):347–356. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.SOLVD Investigators Effect of enalapril on survival in patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fractions and congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:293–302. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199108013250501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohn J.N., Johnson G., Ziesche S. A comparison of enalapril with hydralazine-isosorbide dinitrate in the treatment of chronic congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:303–310. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199108013250502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cleland J.G.F., Bristow M.R., Erdmann E., Remme W.J., Swedberg K., Waagstein F. Beta-blocking agents in heart failure. Should they be used and how? Eur Heart J. 1996;17:1629–1639. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a014745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]