Abstract

Background

Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli (DEC) is one of the most important etiological agents of diarrheal diseases. In this study we investigated the prevalence, virulence gene profiles, antimicrobial resistance, and molecular genetic characteristics of DEC at a hospital in western China.

Methods

A total of 110 Escherichia coli clinical isolates were collected from the First Affiliated Hospital of Chengdu Medical College from 2015 to 2016. Microbiological methods, PCR, antimicrobial susceptibility test, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and multilocus sequence typing were used in this study.

Results

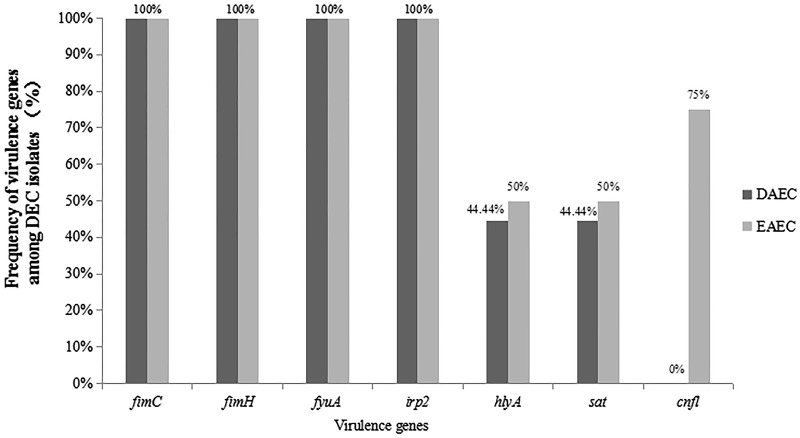

Molecular analysis of six DEC pathotype marker genes showed that 13 of the 110 E. coli isolates (11.82%) were DEC including nine (8.18%) diffusely adherent Escherichia coli (DAEC) and four (3.64%) enteroaggregative Escherichia coli (EAEC). The adherence genes fimC and fimH were present in all DAEC and EAEC isolates. All nine DAEC isolates harbored the virulence genes fyuA and irp2 and four (44.44%) also carried the hlyA and sat genes. The virulence genes fyuA, irp2, cnf1, hlyA, and sat were found in 100%, 100%, 75%, 50%, and 50% of EAEC isolates, respectively. In addition, all DEC isolates were multidrug resistant and had high frequencies of antimicrobial resistance. Molecular genetic characterization showed that the 13 DEC isolates were divided into 11 pulsed-field gel electrophoresis patterns and 10 sequence types.

Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this study provides the first report of DEC, including DAEC and EAEC, in western China. Our analyses identified the virulence genes present in E. coli from a hospital indicating their role in the isolated DEC strains’ pathogenesis. At the same time, the analyses revealed, the antimicrobial resistance pattern of the DEC isolates. Thus, DAEC and EAEC among the DEC strains should be considered a significant risk to humans in western China due to their evolved pathogenicity and antimicrobial resistance pattern.

Keywords: Diarrhea, Escherichia coli, Virulence genes, Antimicrobial resistance, Molecular genetics

Background

Diarrheal illnesses are the major cause of morbidity and mortality in both infants and young children and pose a severe public health problem. Diarrheal diseases are most prevalent in low- and middle-income areas in Africa, Asia, and Latin America because of poor living conditions [1, 2]. In China, infectious diarrhea continues to be one of the foremost public health issues, with up to 70,000,000 infectious diarrheal cases annually; the incidence of diarrhea is in the top three of the 38 notifiable infectious diseases [3, 4].

The bacterium Escherichia coli is one of the most important etiological agents of diarrheal diseases. E. coli strains have evolved by acquiring various functions through horizontal gene transfer, enabling them to successfully persist in hosts [2, 5, 6]. The acquisition of different groups of virulence genes has resulted in the formation of specific types of diarrheagenic E. coli (DEC) [5].

DEC consist of six major pathotypes: enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC), enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC; e.g., Shiga toxin-producing E. coli, STEC), enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC), enteroinvasive E. coli (EIEC), enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC), and diffusely adherent E. coli (DAEC) [5]. EAEC is characterized by the presence of the transcriptional activator gene aggR and/or the serine protease precursor gene (pic) and/or the enteroaggregative heat stable toxin 1 (EAST-1) gene (astA). The presence of Shiga toxin genes (stx1 and stx2) is attributed to EHEC. EPEC is characterized by the presence of the intimin gene (eae) and/or the bundle forming pili gene (bfp). The product of the eae gene enables attachment and effacement on intestinal epithelial cells, while bfp is encoded on the EPEC adherence factor (EAF) plasmid. EIEC harbors an invasion plasmid encoding several invasion genes including ipaH. ETEC is defined by two toxin genes, heat labile (elt) and/or heat-stable (est). Similar to most DEC characterized, DAEC carries two F1845 fimbrial adhesion genes (daaD and/or daaE), which are highly conserved and probably involved in the virulence mechanism [2, 7, 8].

In DEC pathogenesis, adherence is generally the initial, prerequisite step in successful colonization of a specific host mucosal tissue and fimbriae play an important role in adherence [9–13]. The adherence genes examined in this study are all structural genes of different fimbriae. Type 1 fimbriae (encoded by fimC and fimH) bind to mannose-containing receptors on epithelial cells [14–16]. The aggregative adherence fimbria (AAF/I-AAF/V) family includes five types; aggA, aafA, agg3A, and agg4A encode aggregative adherence fimbria (AAF/I-AAF/IV), respectively [17–21], which mediate localized adherence, the aggregative (AA) pattern, and biofilm formation [22–24]. The long polar fimbriae (LPF) are encoded by the conservative fimbrial gene (lpfA) in some DEC strains [25, 26]. Additional adherent genes have been used to screen DEC including sfa (S fimbriae) and pap (P fimbriae) [27].

Following adhesion, DEC produces cytotoxic effects on the intestinal mucosa by secreting virulence factors, in order to induce mucosal inflammation [28–30]. Pathogenicity islands (PIs) are large regions of microbial genomes; in same species, they are present in pathogenic, but not in non-pathogenic strains [31]. The high pathogenicity island (HPI) appears to be widespread in Enterobacteriaceae [32–34]. The irp2 and fyuA genes are important structural genes of HPI [35–37]. Another PI, known as the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE), can induce attaching and effacing (AE) lesions [38]. LEE is organized in five operons (LEE1 to LEE5) [39–41] including the escJ, escN, escV, and espP structural genes [42]. In addition to LEE, various non-LEE (Nle) effectors (encoding nleB, nleE, and ent/espL2) [40, 43, 44] are located outside of the LEE region [45, 46]. Nle proteins contribute to increased bacterial virulence [44].

The remaining virulence factors examined in this study have been reported in previous studies. E. coli strains isolated in the 1980s from intestinal or extra-intestinal infections were designated as either cytotoxic necrotizing factor type 1 (CNF1) or cytotoxic necrotizing factor type 2 (CNF2) [47–49]. In 1987, an E. coli strain isolated from a diarrheal patient was found to possess cytolethal distending toxin (CDT) [50]. In 1990, Watanabe et al. [51] discovered the InvE protein, which is considered as an essential factor for virulence gene expression in Shigella sonnei. In the 1990s, α-hemolysin (HlyA) was shown to belong to a group of pore-forming leukotoxins containing RTX repeats. HlyA is a known virulence factor in E. coli [52–54]. In 1998, Navarro-Garcia et al. demonstrated that Pet (plasmid encoded toxin) is a cytotoxin that modifies the cytoskeleton of enterocytes, causing rounding and cell detachment in EAEC [55]. In 2001, Henderson and Nataro reported that secreted autotransporter toxin (Sat) belongs to the serine protease autotransporter subfamily of Enterobacteriaceae (SPATE) toxins [56]. In 2004, Paton et al. [57] revealed that some E. coli strains isolated from patients produced an AB5 toxin subtilase (SubAB).

DEC strains have been reported more and more frequently in diarrheal patients in different regions of China including Beijing [58], Shanghai [59], Henan Province [60], Wuhan [61], Kunming [62], Zhejiang Province [63] and Hongkong [64]. However, no data is available regarding DEC strains in western China and their virulence genes. Thus, in this study, we investigated the prevalence and characteristics of DEC at a hospital in western China.

Results

Prevalence of DEC among 110 E. coli strains

In order to investigate the prevalence of DEC, we categorized the clinical E. coli (n = 110) isolates into different DEC pathotypes based on the PCR results for virulence marker genes. Thirteen (11.82%) of the 110 E. coli strains were identified as DEC; nine (8.18%) and four (3.64%) of these 13 DEC strains were shown to be DAEC and EAEC, respectively. No EPEC, EHEC, ETEC, or EIEC strains were detected in this study. These results suggest the existence of a certain incidence of DEC at this hospital in western China.

Prevalence of DAEC and EAEC among DEC

Nine of the 13 DEC isolates were DAEC, giving a positive rate of 69.23% among DEC and 8.18% among the 110 E. coli samples. All nine DAEC isolates were daaD-positive and daaE-negative.

The four EAEC isolates carried the pic gene; however, the other two EAEC virulence marker genes (aggR and astA) were not detected in any of the 110 E. coli strains. The positive rate of EAEC was 30.77% in DEC and 3.64% in the 110 E. coli samples. These results suggest that DAEC was the most common of the six major pathotypes in this study, followed by EAEC.

Presence of adherence and virulence genes

All DAEC and EAEC strains were tested by PCR to detect the nine adherent genes and 18 toxin-encoding genes. As shown in Table 1 and Fig. 1, all nine DAEC strains harbored the fimC, fimH, fyuA, and irp2 genes (100%) and four (44.44%) also contained the hlyA and sat genes.

Table 1.

Distribution of virulence gene incidence among DEC

| DEC group | Virulence genes, % (n) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fimC | fimH | fyuA | irp2 | hlyA | sat | cnf1 | |

| DAEC | 100 (9) | 100 (9) | 100 (9) | 100 (9) | 44.44 (4) | 44.44 (4) | 0 (0) |

| EAEC | 100 (4) | 100 (4) | 100 (4) | 100 (4) | 50 (2) | 50 (2) | 75 (3) |

Fig. 1.

Frequency of virulence genes among DEC isolates

Concomitantly, all four EAEC strains were positive for fimC, fimH, fyuA and irp2 (100%). The cnf1 gene was identified in three (75%) EAEC strains and the hly and sat genes were both found in two (50%) of the four EAEC strains (Table 1 and Fig. 1).

All DAEC and EAEC isolates were negative for the remaining adherence and toxin-encoding genes tested (aggA, aafA, agg3A, agg4A, lpfA, sfa, pap, escJ, escN, escV, espP, nleB, nleE, ent/espL2, cnf2, cdt-I, cdt-II, invE, pet, and subAB). Therefore, our data indicate that fimC, fimH, fyuA, irp2, hlyA, and sat contribute to DAEC pathogenesis, while fimC, fimH, fyuA, irp2, cnf1, hlyA, and sat are involved in EAEC pathogenesis.

Antimicrobial resistance

The antimicrobial resistance of these DEC isolates against 23 antibiotics was examined; both the DAEC and EAEC isolates exhibited high frequencies of antimicrobial resistance. All nine DAEC isolates were resistant to sulfonamide, doxycycline, and tetracycline. The resistance rates to cefotaxime, ampicillin, ticarcillin, nalidixic acid, cefoperazone, piperacillin, gentamicin, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, ofloxacin, tobramycin, cefoxitin, ceftazidime, minocycline, aztreonam, kanamycin, amikacin, meropenem, imipenem, and ertapenem were 88.89% (8/9), 88.89% (8/9), 88.89% (8/9), 77.78% (7/9), 66.67% (6/9), 66.67% (6/9), 55.56% (5/9), 55.56% (5/9), 44.44% (4/9), 44.44% (4/9), 33.33% (3/9), 22.22% (2/9), 22.22% (2/9), 22.22% (2/9), 22.22% (2/9), 11.11% (1/9), 0% (0/9), 0% (0/9), 0% (0/9), and 0% (0/9), respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Antimicrobial resistance among DEC

| Antibiotic | DAEC | EAEC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | n | % | n | |

| SSS | 100 | 9 | 100 | 4 |

| DOX | 100 | 9 | 75 | 3 |

| TET | 100 | 9 | 75 | 3 |

| CTX | 88.89 | 8 | 25 | 1 |

| AMP | 88.89 | 8 | 75 | 3 |

| TIC | 88.89 | 8 | 75 | 3 |

| NA | 77.78 | 7 | 100 | 4 |

| CFP | 66.67 | 6 | 25 | 1 |

| PIP | 66.67 | 6 | 50 | 2 |

| GEN | 55.56 | 5 | 50 | 2 |

| CIP | 55.56 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| LEV | 44.44 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| OFX | 44.44 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| TOB | 33.33 | 3 | 25 | 1 |

| FOX | 22.22 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| CAZ | 22.22 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| MIN | 22.22 | 2 | 50 | 2 |

| ATM | 22.22 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| KAN | 11.11 | 1 | 25 | 1 |

| AMK | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MERO | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| IMP | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ETP | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

SSS sulfonamide, DOX doxycycline, TET tetracycline, CTX cefotaxime, AMP ampicillin, TIC ticarcillin, NA nalidixic acid, CFP cefoperazone, PIP piperacillin, GEN gentamicin, CIP ciprofloxacin, LEV levofloxacin, OFX ofloxacin, TOB tobramycin, FOX cefoxitin, CAZ ceftazidime, MIN minocycline, ATM aztreonam, KAN kanamycin, AMK amikacin, MERO meropenem, IMP imipenem, ETP ertapenem

The resistance rates of the EAEC strains for sulfonamide, nalidixic acid, doxycycline, tetracycline, ampicillin, ticarcillin, gentamicin, minocycline, piperacillin, tobramycin, kanamycin, cefoperazone, and cefotaxime were 100% (4/4), 100% (4/4), 75% (3/4), 75% (3/4), 75% (3/4), 75% (3/4), 50% (2/4), 50% (2/4), 50% (2/4), 25% (1/4), 25% (1/4), 25% (1/4), and 25% (1/4), respectively (Table 2). All EAEC isolates were susceptible to the remaining 10 antibiotics.

Importantly, we found that all DEC isolates, including the nine DAEC and four EAEC strains, were multidrug resistant (MDR). These results suggest that clinical abuse of antibiotics is already a very serious problem in China.

Frequency of virulence genes among antimicrobial resistant DEC isolates

Virulence gene frequencies among the antimicrobial resistant DAEC and EAEC isolates are shown in Tables 3 and 4. The frequency of the fimC, fimH, fyuA, and irp2 virulence genes among resistant DEC isolates reached 100%, while the frequency of the remaining genes (hlyA, sat, and cnf1) among resistant isolates was mostly ≥ 50%.

Table 3.

Frequency of virulence genes among antimicrobial resistant DAEC isolates

| Antibiotic (n) | Virulence genes, % (n) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fimC | fimH | fyuA | irp2 | hlyA | sat | |

| SSS (9) | 100 (9) | 100 (9) | 100 (9) | 100 (9) | 44.44 (4) | 44.44 (4) |

| DOX (9) | 100 (9) | 100 (9) | 100 (9) | 100 (9) | 44.44 (4) | 44.44 (4) |

| TET (9) | 100 (9) | 100 (9) | 100 (9) | 100 (9) | 44.44 (4) | 44.44 (4) |

| CTX (8) | 100 (8) | 100 (8) | 100 (8) | 100 (8) | 50 (4) | 37.5 (3) |

| AMP (8) | 100 (8) | 100 (8) | 100 (8) | 100 (8) | 50 (4) | 37.5 (3) |

| TIC (8) | 100 (8) | 100 (8) | 100 (8) | 100 (8) | 50 (4) | 37.5 (3) |

| NA (7) | 100 (7) | 100 (7) | 100 (7) | 100 (7) | 42.86 (3) | 57.14 (4) |

| CFP (6) | 100 (6) | 100 (6) | 100 (6) | 100 (6) | 33.33 (2) | 50 (3) |

| PIP (6) | 100 (6) | 100 (6) | 100 (6) | 100 (6) | 33.33 (2) | 50 (3) |

| GEN (5) | 100 (5) | 100 (5) | 100 (5) | 100 (5) | 40 (2) | 40 (2) |

| CIP (5) | 100 (5) | 100 (5) | 100 (5) | 100 (5) | 40 (2) | 40 (2) |

| LEV (4) | 100 (4) | 100 (4) | 100 (4) | 100 (4) | 25 (1) | 50 (2) |

| OFX (4) | 100 (4) | 100 (4) | 100 (4) | 100 (4) | 25 (1) | 50 (2) |

| TOB (3) | 100 (3) | 100 (3) | 100 (3) | 100 (3) | 0 (0) | 66.67 (2) |

| FOX (2) | 100 (2) | 100 (2) | 100 (2) | 100 (2) | 50 (1) | 0 (0) |

| CAZ (2) | 100 (2) | 100 (2) | 100 (2) | 100 (2) | 0 (0) | 50 (1) |

| MIN (2) | 100 (2) | 100 (2) | 100 (2) | 100 (2) | 50 (1) | 50 (1) |

| ATM (2) | 100 (2) | 100 (2) | 100 (2) | 100 (2) | 0 (0) | 50 (1) |

| KAN (1) | 100 (1) | 100 (1) | 100 (1) | 100 (1) | 0 (0) | 100 (1) |

SSS sulfonamide, DOX doxycycline, TET tetracycline, CTX cefotaxime, AMP ampicillin, TIC ticarcillin, NA nalidixic acid, CFP cefoperazone, PIP piperacillin, GEN gentamicin, CIP ciprofloxacin, LEV levofloxacin, OFX ofloxacin, TOB tobramycin, FOX cefoxitin, CAZ ceftazidime, MIN minocycline, ATM aztreonam, KAN kanamycin

Table 4.

Frequency of virulence genes among antimicrobial resistant EAEC isolates

| Antibiotic (n) | Virulence genes, % (n) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fimC | fimH | fyuA | irp2 | cnf1 | hlyA | sat | |

| SSS (4) | 100 (4) | 100 (4) | 100 (4) | 100 (4) | 75 (3) | 50 (2) | 50 (2) |

| NA (4) | 100 (4) | 100 (4) | 100 (4) | 100 (4) | 75 (3) | 50 (2) | 50 (2) |

| DOX (3) | 100 (3) | 100 (3) | 100 (3) | 100 (3) | 50 (2) | 25 (1) | 25 (1) |

| TET (3) | 100 (3) | 100 (3) | 100 (3) | 100 (9) | 50 (2) | 25 (1) | 25 (1) |

| AMP (3) | 100 (3) | 100 (3) | 100 (3) | 100 (3) | 50 (2) | 25 (1) | 25 (1) |

| TIC (3) | 100 (3) | 100 (3) | 100 (3) | 100 (3) | 50 (2) | 25 (1) | 25 (1) |

| GEN (2) | 100 (2) | 100 (2) | 100 (2) | 100 (2) | 25 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| MIN (2) | 100 (2) | 100 (2) | 100 (2) | 100 (2) | 25 (1) | 25 (1) | 25 (1) |

| PIP (2) | 100 (2) | 100 (2) | 100 (2) | 100 (2) | 25 (1) | 25 (1) | 25 (1) |

| TOB (1) | 100 (1) | 100 (1) | 100 (1) | 100 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| KAN (1) | 100 (1) | 100 (1) | 100 (1) | 100 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| CFP (1) | 100 (1) | 100 (1) | 100 (1) | 100 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| CTX (1) | 100 (1) | 100 (1) | 100 (1) | 100 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

SSS sulfonamide, NA nalidixic acid, DOX doxycycline, TET tetracycline, AMP ampicillin, TIC ticarcillin, GEN gentamicin, MIN minocycline, PIP piperacillin, TOB tobramycin, KAN kanamycin, CFP cefoperazone, CTX cefotaxime

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis

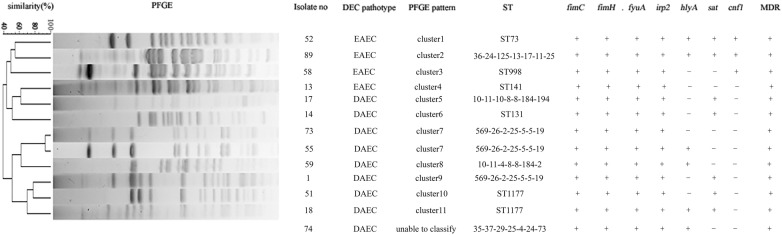

The 13 DEC isolates (nine DAEC and four EAEC) were analyzed by PFGE to determine their genetic relationships. All isolates, except for no. 74, produced clear bands. The DEC PFGE results were analyzed with a Dice similarity index of 80%, according to which the 13 DEC could be divided into 11 clusters (cluster 1 to cluster 11) [65]. Isolates no. 73 and 55 belonged to one cluster, while the remaining isolates revealed another 10 distinct clusters (Fig. 2). There were no identical pulsotypes, demonstrating notable genetic diversity among the 13 DEC isolates.

Fig. 2.

PFGE profiles of 13 DEC. The isolate number, DEC pathotype, PFGE pattern, sequence type (ST), virulence genes (fimC, fimH, fyuA, irp2, hlyA, sat, and cnf1) and multidrug resistance (MDR) are listed on the right. “+” indicates gene positive or MDR; “−” indicates gene negative or not MDR

Multilocus sequence typing

The homology of the 13 DEC isolates was examined by MLST. Six of the 13 DEC isolates could be divided into five known sequence types (STs), as detailed in Fig. 2. ST1177 was the most frequent ST, represented by isolates no. 18 and 51. The remaining seven isolates could be divided into five novel STs based on their allelic profiles as detailed in Fig. 2, and are being prepared for submission. The same allelic profile (569-26-2-25-5-5-19) was detected in isolates no. 1, 55, and 73. Furthermore, the STs and PFGE patterns of the 13 DEC isolates were sporadic and heterogeneous, indicating diverse genetic backgrounds.

Discussion

In recent years, DEC isolates have been reported in diarrheal patients in a number of studies in China; however, limited information is available regarding their prevalence in western China and virulence genes. In our study, we investigated DEC at a hospital in western China, extending our knowledge of the prevalence and characteristics of DEC in China.

The proportion of DEC among E. coli in our study was 11.82%, which is comparable to previous reports in Shanghai (11.6%) [66] and the Henan Province (12.05%) [60]. DEC occurrence in our study was higher than in Beijing (4.6%) [58] and the southeast coast (7.6%) of China [67]. In contrast, the detected rate of DEC was 30.2% in India [68], 39% in Brazil [69], and 30% in Peru [70], much higher than the rate in this study. These results suggest that the occurrence of DEC is comparatively low in China.

Interestingly, nine DAEC isolates were identified among the 13 DEC strains, giving a positive rate of 69.23%, indicating that DAEC was the most common major pathotype in this study. The proportion of DAEC among E. coli strains was 8.18% (9/110), demonstrating a certain incidence rate of DAEC at this hospital in western China. The prevalence of DAEC among E. coli was higher than in the neighboring Japan and in South American countries such as Peru and Colombia [70–72]. Limited information is available regarding DAEC, the sixth DEC pathotype, in China. This is the first report of the occurrence of DAEC at a hospital in western China, demonstrating that the prevalence of DAEC is comparatively high.

In the present study, 3.64% of E. coli isolates were EAEC, which is lower than reported in other regions in China [60, 62, 67] and much lower than reported in India, Brazil, and Peru [68–70]. However, these data show that we detected a certain level of EAEC in this study, second only to DAEC levels.

The type 1 fimbriae encoding genes fimC and fimH were identified in 100% of DAEC and EAEC isolates in our study. This adhesin is present in nearly all E. coli strains [34]. Lopes et al. detected daaE, aggA, agg3A, sfa, pap, and fimH in DAEC, with fimH the most frequently (48%) identified [73] and Lima et al. detected agg3A, aafA, aggA, and agg4A in EAEC [74]. However, we only detected the daaD, fimC, and fimH adherence genes, suggesting that the DAEC and EAEC strains in our study may have adhered via adhesins other than those previously described.

The HPI marker genes fyuA and irp2, first identified in Yersinia enterocolitica, were detected in 100% of DAEC and EAEC isolates in this study; fyuA and irp2 encode the bacterial siderophore yersiniabactin. The yersiniabactin-mediated iron-uptake system is clustered in HPI and its presence is correlated with the virulence of highly pathogenic Yersinia [32, 75]. HPI has been shown to be widespread in various Enterobacteriaceae [32–34]. Therefore, it is possible that HPI could spread horizontally between Yersinia and DAEC/EAEC and contribute to the pathogenesis of DAEC and EAEC.

The hlyA gene had a positive rate of 44.44% and 50% in DAEC and EAEC, respectively. HlyA is frequently detected in EAEC and DAEC strains [23, 76]; depending on its concentration and the type of cell affected, HlyA either displays cytolytic activity or hijacks innate immune signaling pathways [54, 77, 78]. The high percent of hlyA in this study suggests that HlyA is involved in the mechanisms of DAEC and EAEC pathogenicity.

The sat gene showed a positive rate of 44.44% and 50% in DAEC and EAEC, respectively. Guignot et al. [79] have demonstrated that Sat can induce lesions on tight junctions of epithelial cells, which in turn may cause an increase in their permeability; Spano et al. [69] reported that 26.2% of DAEC and 14.5% of EAEC were positive for sat; Mansan-Almeida et al. [80] found that 66.7% of DAEC isolated from adult patients carried sat; and Lima et al. [74] identified sat in 38.3% of EAEC. The rate of DAEC harboring sat in our study is between that reported by Spano et al. and Mansan-Almeida et al., while the prevalence of sat in EAEC was higher than reported by Spano et al. and Lima et al. Taken together, we conclude that Sat may play a role in the pathogenesis of DAEC and EAEC.

The cnf1 gene was found in three (75%) EAEC isolates, but not in any DAEC isolates, while cnf2 was not detected in any DAEC and EAEC isolates. Cytotoxic necrotizing factor type 1 (CNF1) and cytotoxic necrotizing factor type 2 (CNF2) are two monomeric proteins that lead to necrosis in rabbit skin cells and multinucleation of different eukaryotic cells in culture [47, 49, 81]. Lopes et al. [73] found cnf in 1.8% of DAEC strains and Bouzari et al. [82] detected the cnf1 and cnf2 genes in 29.4% and 23.1% of DEC strains, respectively. In this study, we found cnf1 in 23.1% (3/13) of DEC strains, but did not detect cnf2 in any DEC strains. These results indicate that in this study the occurrence of cnf1 and cnf2 was lower in DEC strains, especially in DAEC.

In the current study, pet was not detected in any DAEC and EAEC strains. The cytotoxic mechanism of Pet arises from the degradation of α-fodrin, which is an enterocyte membrane protein [55]. Spano et al. [69] reported that 54.8% of DAEC and 55.3% of EAEC strains were positive for pet and Lima et al. [74] found pet in 10.5% of EAEC strains. These observations support our findings that few DAEC and EAEC strains in this study carry pet.

The antimicrobial resistance of the DAEC and EAEC strains was also examined. First-line antibiotics, such as gentamicin, cefotaxime, tetracycline, ciprofloxacin, ampicillin, and sulfonamide, showed low activity against the DAEC and EAEC strains. In particular, DAEC resistance to sulfonamide, doxycycline, and tetracycline reached 100%, while the resistance of EAEC to sulfonamide and nalidixic acid was also 100%. The resistance rates of these two pathotypes were higher than reported in developing countries including India, Brazil, and Peru [68–70]. Moreover, we found that all DAEC and EAEC isolates were MDR; only imipenem, meropenem, ertapenem, and amikacin remained effective against the nine DAEC and four EAEC isolates in this study. These results suggest that clinical abuse of antibiotics has become an increasingly serious issue in China. In addition, we found that the DEC strains not only exhibited high frequencies of antimicrobial resistance, but also showed a high frequency of carrying virulence genes (Tables 3 and 4). These properties enable DEC to successfully infect hosts and hinder effective antibiotic treatment.

Of the many genetic fingerprinting methods employed for epidemiological molecular typing, PFGE is considered to be the gold standard [83–85]. Here, using a high-resolution PFGE method, we identified a high degree of genetic diversity among the DEC isolates. Except for one isolate that we were unable to classify, we observed 11 clusters from 13 DEC isolates. None of the isolates had an identical pulsotype. These data demonstrate high genotype diversity among the DEC isolates.

MLST based on DNA sequence variations in slowly-evolving housekeeping genes has been used in epidemiological studies [86, 87]. In the present study, the 13 DEC strains could be divided into 10 STs including five novel STs. Chen et al. [86] reported that most clinical DEC isolates circulating in southeast China show a high degree of genetic diversity within a relatively small area, in agreement with our findings.

In summary, the 13 DEC isolates showed different PFGE patterns and STs, but harbored similar virulence genes (fimC, fimH, fyuA, irp2, sat, hlyA, and cnf1) and exhibited high antimicrobial resistance (Fig. 2). Strain phylogenetic origin changes according to ecological niche, lifestyle, and propensity to cause disease [88]. The exchange of virulence and other genes may favor such genetic relatedness. Genes associated with various pathotypes are acquired by many different DEC lineages and some lineages are more competitive than others because of the acquired virulence genes [85, 89]. In our study, the different DEC isolates exhibited diverse genotypes, but demonstrated a similar phenotype. This can be attributed to the fact that the strains harbored comparable virulence gene profiles, further indicating that virulence genes play an important role in DEC pathogenesis.

Conclusions

This study provides the first report of DEC, including DAEC and EAEC, in western China. Our findings expand our knowledge of DEC prevalence and characteristics in China and elucidate the role of virulence genes in DEC pathogenesis. In this study, we found that the DEC strains not only exhibited high frequencies of antimicrobial resistance, but also showed a high frequency of carrying virulence genes. These properties enable DEC to successfully infect hosts and hinder effective antibiotic treatment. Furthermore, they suggest that clinical abuse of antibiotics is already a very serious issue in China. However, further investigations are needed including additional hospitals in western China and a greater number of DEC isolates.

Methods

Bacterial isolates

A total of 110 non-duplicated E. coli clinical isolates were collected from 110 different patients in various departments (gastroenterology, endocrinology, neurosurgery, and other wards) at the First Affiliated Hospital of Chengdu Medical College, Chengdu, Sichuan, China from 2015 to 2016. Isolates were identified using standard laboratory methods and the ATB New system (bioMérieux, Lyons, France). Each isolate was further verified by PCR amplification of a 369-bp internal control region from the E. coli marker gene alr [90]. All strains were stored at − 80 °C and bacteria were grown on MacConkey Agar (Oxoid, Hampshire, UK).

Identification of DEC by PCR

All E. coli isolates were examined by PCR to detect the following virulence markers: aggR, pic, and astA for EAEC; stx1 and stx2 for EHEC; eae and bfp for EPEC; ipaH (invasion plasmid antigen H) for EIEC; est and elt (enterotoxins) for ETEC; and daaD and daaE for DAEC. The primers used to amplify these genes are listed in Table 5.

Table 5.

Gene primers used in this study

| Gene | Primer sequence (5′-3′) | PCR product (bp) | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| alr | F: CTGGAAGAGGCTAGCCTGGACGAG R: AAAATCGCCACCGGTGGAGCGATC |

369 | [90] |

| pic | F: GGGTATTGTCCGTTCCGAT R: ACAACGATACCGTCTCCCG |

1176 | [93] |

| astA | F: CCATCAACACAGTATATCCGA R: GGTCGCGAGTGACGGCTTTGT |

111 | [73] |

| aggR | F: ACGCAGAGTTGCCTGATAAAG R: AATACAGAATCGTCAGCATCAGC |

400 | [94] |

| stx1 | F: CGATGTTACGGTTTGTTACTGTGACAGC R: AATGCCACGCTTCCCAGAATTG |

244 | [94] |

| stx2 | F: GTTTTGACCATCTTCGTCTGATTATTGAG R: AGCGTAAGGCTTCTGCTGTGAC |

324 | [94] |

| eae | F: TGAGCGGCTGGCATGAGTCATAC R: TCGATCCCCATCGTCACCAGAGG |

241 | [95] |

| bfp | F: GACACCTCATTGCTGAAGTCG R: CCAGAACACCTCCGTTATGC |

324 | [94] |

| ipaH | F: GTTCCTTGACCGCCTTTCCGATACCGTC R: AAAATCGCCACCGGTGGAGCGATC |

619 | [7] |

| est | F: ATTTTTCTTTCTGTATTGTCTT R: CACCCGGTACAGGCAGGATT |

190 | [96] |

| elt | F: GGCGACAGATTATACCGTGC R: CGGTCTCTATATTCCCTGTT |

450 | [96] |

| daaD | F: TGAACGGGAGTATAAGGAAGATG R: GTCCGCCATCACATCAAAA |

444 | [97] |

| daaE | F: GAACGTTGGTTAATGTGGGGTAA R: TATTCACCGGTCGGTTATCAGT |

542 | [8] |

| fimC | F: GGGTAGAAAATGCCGATGGTG R: CGTCATTTTGGGGGTAAGTG |

477 | [98] |

| fimH | F: CGAGTTATTACCCTGTTTGCTG R: ACGCCAATAATCGATTGCAC |

878 | [73] |

| aggA | F: GCTAACGCTGCGTTAGAAAGACC R: GGAGTATCATTCTATATTCGCC |

421 | [73] |

| aafA | F: ATGTATTTTTAGAGGTTGAC R: TATTATATTGTCACAAGCTC |

518 | [20] |

| agg3A | F: GTATCATTGCGAGTCTGGTATTCAG R: GGGCTGTTATAGAGTAACTTCCAG |

462 | [73] |

| agg4A | F: TGAGTTGTGGGGCTAYCTGGACACC R: ATAAGCCGCCAAATAAGC |

169 | [74] |

| lpfA | F: AGGCGGTGCATTCACTCTGGCATCT R: CCGCGTCGATAGCGGTATAGGCAGA |

446 | [99] |

| sfa | F: CTCCGGAGAACTGGGTGCATCTTAC R: CGGAGGAGTAATTACAAACCTGGCA |

408 | [73] |

| pap | F: GACGGCTGTACTGCAGGGTGTGGCG R: ATATCCTTTCTGCAGGGATGCAATA |

328 | [73] |

| irp2 | F: AAGGATTCGCTGTTACCGGAC R: TCGTCGGGCAGCGTTTCTTCT |

264 | [100] |

| fyuA | F: TGATTAACCCCGCGACGGGAA R: CGCAGTAGGCACGATGTTGTA |

785 | [34] |

| escJ | F: CACTAAGCTCGATATATAGAACCC R: GTCAATGTTGATGTCGTATCTAAG |

824 | [80] |

| escN | F: CGCCTTTTACAAGATAGAAC R: CATCAAGAATAGAGCGGAC |

854 | [101] |

| escV | F: GATGACATCATGAATAAACTC R: GCCTTCATATCTGGTAGAC |

2128 | [80] |

| espP | F: AAACAGCAGGCACTTGAACG R: GGAGTCGTCAGTCAGTAGAT |

1830 | [93] |

| nleB | F: GGAAGTTTGTTTACAGAGACG R: AAAATGCCGCTTGATACC |

297 | [43] |

| nleE | F: GTATAACCAGAGGAGTAGC R: GATCTTACAACAAATGTCC |

260 | [43] |

| ent/espL2 | F: GAATAACAATCACTCCTCACC R: TTACAGTGCCCGATTACG |

233 | [43] |

| cnf1 | F: GGCGACAAATGCAGTATTGCTTGG F: GACGTTGGTTGCGGTAATTTTGGG |

552 | [93] |

| cnf2 | F: GTGAGGCTCAACGAGATTATGCACTG R: CCACGCTTCTTCTTCAGTTGTTCCTC |

839 | [93] |

| cdt-I | F: CAATAGTCGCCCACAGGA R: ATAATCAAGAACACCACCAC |

412 | [102] |

| cdt-II | F: GAAAGTAAATGGAATATAAATGTCCG R: TTTGTGTTGCCGCCGCTGGTGAAA |

556 | [102] |

| invE | F:CGATCAAGAATCCCTAACAGAAGAATCAC R: CGATAGATGGCGAGAAATTATATCCCG |

766 | [94] |

| hlyA | F: GCATCATCAAGCGTACGTTCC R: AATGAGCCAAGCTGGTTAAGCT |

533 | [100] |

| pet | F: TTTCCAGCACTTCCTGTTCC R: ATTTCCAACGTCTACGCCAT |

297 | [103] |

| sat | F: GCAGCAAATATTGATATATCA R: GTTGTTGACCTCAGCAAGGAA |

2913 | [80] |

| subAB | F: TATGGCTTCCCTCATTGCC R: TATAGCTGTTGCTTCTGACG |

556 | [104] |

Detection of adherence and virulence genes

All DEC isolates were subjected to PCR to detect nine adherence genes (fimC, fimH, aggA, aafA, agg3A, agg4A, lpfA, sfa, and pap) and 18 virulence genes (irp2, fyuA, escJ, escN, escV, espP, nleB, nleE, ent/espL2, cnf1, cnf2, cdt-I, cdt-II, invE, hlyA, pet, sat, and subAB). The primers used to amplify these genes are listed in Table 5.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

The minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 23 antimicrobial agents for DEC were determined by the agar dilution methods according to the 2017 Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines [91]. We tested the following 23 antimicrobial agents: sulfonamide, doxycycline, tetracycline, cefotaxime, ampicillin, ticarcillin, nalidixic acid, cefoperazone, piperacillin, gentamicin, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, ofloxacin, tobramycin, cefoxitin, ceftazidime, minocycline, aztreonam, kanamycin, amikacin, meropenem, imipenem, and ertapenem. The results were used to classify isolates as resistant or susceptible to a particular antibiotic using standard reference values [91].

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE)

Genomic DNA from the DEC isolates were digested with XbaI and separated by PFGE according to the protocol of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (http://www.cdc.gov/pulsenet/pathogens/index.html). Gel images were captured with the Gel Doc XR+ system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). An unweighted pair-group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA) dendrogram was constructed using BioNumerics software (Applied Maths, Sint-Martens-Latem, Belgium).

Multilocus sequence typing

All DEC isolates were analyzed by multilocus sequence typing (MLST) according to the MLST website (http://mlst.warwick.ac.uk). Briefly, the internal fragments of seven housekeeping genes (adk, fumC, gyrB, icd, mdh, purA, and recA) were amplified by PCR [92] and their sequences were compared with existing sequences in the MLST database for the assignment of allelic numbers. Sequence types (STs) were assigned according to the allelic profiles.

Authors’ contributions

DL, XJ and YM designed the project, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; YX and CL collected samples; and DL, MS, WW, JW, and XL carried out the experiments. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

None.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

Data of the study can be available upon request from the corresponding author (XJ).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Chengdu Medical College Ethics Committee.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants 31470246 and 31300659), Scientific Research and Innovation Team of Sichuan Province (Grant 15TD0025), Preeminent Youth Fund of Sichuan Province (Grant 2015JQO019) and Huimin Project of Chengdu Science and Technology Bureau (Grant 2015-HM01-00543-SF), Natural Science Foundation of Sichuan Provincial Education Department (Grant 15ZB0239), Natural Science Foundation of Chengdu Medical College (Grant CYZ11-008).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- DEC

diarrheagenic E. coli

- EAEC

enteroaggregative E. coli

- EHEC

enterohemorrhagic E. coli

- EPEC

enteropathogenic E. coli

- EIEC

enteroinvasive E. coli

- ETEC

enterotoxigenic E. coli

- DAEC

diffusely adherent E. coli

- SSS

sulfonamide

- DOX

doxycycline

- TET

tetracycline

- CTX

cefotaxime

- AMP

ampicillin

- TIC

ticarcillin

- NA

nalidixic acid

- CFP

cefoperazone

- PIP

piperacillin

- GEN

gentamicin

- CIP

ciprofloxacin

- LEV

levofloxacin

- OFX

ofloxacin

- TOB

tobramycin

- FOX

cefoxitin

- CAZ

ceftazidime

- MIN

minocycline

- ATM

aztreonam

- KAN

kanamycin

- AMK

amikacin

- MERO

meropenem

- IMP

imipenem

- ETP

ertapenem

- MDR

multidrug resistant

- PFGE

pulsed-field gel electrophoresis

- MLST

multilocus sequence typing

Contributor Information

Dan Li, Email: 106408082@qq.com.

Min Shen, Email: shenmincmc@163.com.

Ying Xu, Email: yingxu825@126.com.

Chao Liu, Email: liuchao520@outlook.com.

Wen Wang, Email: wangwen25@126.com.

Jinyan Wu, Email: 771867357@qq.com.

Xianmei Luo, Email: 3148075489@qq.com.

Xu Jia, Email: fdjiaxu@gmail.com.

Yongxin Ma, Email: mayongxin@gmail.com.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . World Health statistics. Geneva: WHO Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Croxen MA, Law RJ, Scholz R, Keeney KM, Wlodarska M, Finlay BB. Recent advances in understanding enteric pathogenic Escherichia coli. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2013;26(4):822–880. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00022-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qu M, Deng Y, Zhang X, Liu G, Huang Y, Lin C, et al. Etiology of acute diarrhea due to enteropathogenic bacteria in Beijing, China. J Infect. 2012;65(3):214–222. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2012.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang Y, Zhao Y, Ding K, Wang X, Chen X, Liu Y, et al. Analysis of bacterial pathogens causing acute diarrhea on the basis of sentinel surveillance in Shanghai, China, 2006–2011. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2014;67(4):264–268. doi: 10.7883/yoken.67.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nataro JP, Kaper JB. Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11(1):142–201. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.1.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaper JB, Nataro JP, Mobley HL. Pathogenic Escherichia coli. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2(2):123–140. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barletta F, Ochoa TJ, Cleary TG. Multiplex real-time PCR (MRT-PCR) for diarrheagenic. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;943:307–314. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-353-4_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chandra M, Cheng P, Rondeau G, Porwollik S, McClelland M. A single step multiplex PCR for identification of six diarrheagenic E. coli pathotypes and Salmonella. Int J Med Microbiol IJMM. 2013;303(4):210–216. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2013.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sack RB. Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli: identification and characterization. J Infect Dis. 1980;142(2):279–286. doi: 10.1093/infdis/142.2.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gaastra W, de Graaf FK. Host-specific fimbrial adhesins of noninvasive enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli strains. Microbiol Rev. 1982;46(2):129–161. doi: 10.1128/mr.46.2.129-161.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klemm P. Fimbrial adhesions of Escherichia coli. Rev Infect Dis. 1985;7(3):321–340. doi: 10.1093/clinids/7.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levine MM. Escherichia coli that cause diarrhea: enterotoxigenic, enteropathogenic, enteroinvasive, enterohemorrhagic, and enteroadherent. J Infect Dis. 1987;155(3):377–389. doi: 10.1093/infdis/155.3.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stamm WE, Hooton TM, Johnson JR, Johnson C, Stapleton A, Roberts PL, et al. Urinary tract infections: from pathogenesis to treatment. J Infect Dis. 1989;159(3):400–406. doi: 10.1093/infdis/159.3.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ofek I, Beachey EH. Mannose binding and epithelial cell adherence of Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1978;22(1):247–254. doi: 10.1128/iai.22.1.247-254.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Orndorff PE, Falkow S. Organization and expression of genes responsible for type 1 piliation in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1984;159(2):736–744. doi: 10.1128/jb.159.2.736-744.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klemm P, Christiansen G. Three fim genes required for the regulation of length and mediation of adhesion of Escherichia coli type 1 fimbriae. Mol Gen Genet. 1987;208(3):439–445. doi: 10.1007/BF00328136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nataro JP, Deng Y, Maneval DR, German AL, Martin WC, Levine MM. Aggregative adherence fimbriae I of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli mediate adherence to HEp-2 cells and hemagglutination of human erythrocytes. Infect Immun. 1992;60(6):2297–2304. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.6.2297-2304.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elias WP, Jr, Czeczulin JR, Henderson IR, Trabulsi LR, Nataro JP. Organization of biogenesis genes for aggregative adherence fimbria II defines a virulence gene cluster in enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1999;181(6):1779–1785. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.6.1779-1785.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bernier C, Gounon P, Le Bouguenec C. Identification of an aggregative adhesion fimbria (AAF) type III-encoding operon in enteroaggregative Escherichia coli as a sensitive probe for detecting the AAF-encoding operon family. Infect Immun. 2002;70(8):4302–4311. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.8.4302-4311.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boisen N, Struve C, Scheutz F, Krogfelt KA, Nataro JP. New adhesin of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli related to the Afa/Dr/AAF family. Infect Immun. 2008;76(7):3281–3292. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01646-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jonsson R, Struve C, Boisen N, Mateiu RV, Santiago AE, Jenssen H, et al. Novel aggregative adherence fimbria variant of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 2015;83(4):1396–1405. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02820-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Debroy C, Yealy J, Wilson RA, Bhan MK, Kumar R. Antibodies raised against the outer membrane protein interrupt adherence of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1995;63(8):2873–2879. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.8.2873-2879.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suzart S, Aparecida T, Gomes T, Guth BE. Characterization of serotypes and outer membrane protein profiles in enteroaggregative Escherichia coli strains. Microbiol Immunol. 1999;43(3):201–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1999.tb02394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Monteiro-Neto V, Bando SY, Moreira-Filho CA, Giron JA. Characterization of an outer membrane protein associated with haemagglutination and adhesive properties of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli O111:H12. Cell Microbiol. 2003;5(8):533–547. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2003.00299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Torres AG, Kanack KJ, Tutt CB, Popov V, Kaper JB. Characterization of the second long polar (LP) fimbriae of Escherichia coli O157:H7 and distribution of LP fimbriae in other pathogenic E. coli strains. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2004;238(2):333–344. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2004.07.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tatsuno I, Mundy R, Frankel G, Chong Y, Phillips AD, Torres AG, et al. The lpf gene cluster for long polar fimbriae is not involved in adherence of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli or virulence of Citrobacter rodentium. Infect Immun. 2006;74(1):265–272. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.1.265-272.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Le Bouguenec C, Archambaud M, Labigne A. Rapid and specific detection of the pap, afa, and sfa adhesin-encoding operons in uropathogenic Escherichia coli strains by polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30(5):1189–1193. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.5.1189-1193.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hicks S, Candy DC, Phillips AD. Adhesion of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli to pediatric intestinal mucosa in vitro. Infect Immun. 1996;64(11):4751–4760. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.11.4751-4760.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harrington SM, Dudley EG, Nataro JP. Pathogenesis of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli infection. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2006;254(1):12–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2005.00005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Navarro-Garcia F, Elias WP. Autotransporters and virulence of enteroaggregative E. coli. Gut Microbes. 2011;2(1):13–24. doi: 10.4161/gmic.2.1.14933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morschhauser J, Kohler G, Ziebuhr W, Blum-Oehler G, Dobrindt U, Hacker J. Evolution of microbial pathogens. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2000;355(1397):695–704. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2000.0609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schubert S, Rakin A, Karch H, Carniel E, Heesemann J. Prevalence of the “high-pathogenicity island” of Yersinia species among Escherichia coli strains that are pathogenic to humans. Infect Immun. 1998;66(2):480–485. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.2.480-485.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schubert S, Cuenca S, Fischer D, Heesemann J. High-pathogenicity island of Yersinia pestis in enterobacteriaceae isolated from blood cultures and urine samples: prevalence and functional expression. J Infect Dis. 2000;182(4):1268–1271. doi: 10.1086/315831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson JR, Stell AL. Extended virulence genotypes of Escherichia coli strains from patients with urosepsis in relation to phylogeny and host compromise. J Infect Dis. 2000;181(1):261–272. doi: 10.1086/315217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rakin A, Schneider L, Podladchikova O. Hunger for iron: the alternative siderophore iron scavenging systems in highly virulent Yersinia. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2012;2:151. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bobrov AG, Kirillina O, Fetherston JD, Miller MC, Burlison JA, Perry RD. The Yersinia pestis siderophore, yersiniabactin, and the ZnuABC system both contribute to zinc acquisition and the development of lethal septicaemic plague in mice. Mol Microbiol. 2014;93(4):759–775. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brumbaugh AR, Smith SN, Subashchandrabose S, Himpsl SD, Hazen TH, Rasko DA, et al. Blocking yersiniabactin import attenuates extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli in cystitis and pyelonephritis and represents a novel target to prevent urinary tract infection. Infect Immun. 2015;83(4):1443–1450. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02904-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McDaniel TK, Jarvis KG, Donnenberg MS, Kaper JB. A genetic locus of enterocyte effacement conserved among diverse enterobacterial pathogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92(5):1664–1668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Elliott SJ, Sperandio V, Giron JA, Shin S, Mellies JL, Wainwright L, et al. The locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE)-encoded regulator controls expression of both LEE- and non-LEE-encoded virulence factors in enteropathogenic and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 2000;68(11):6115–6126. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.11.6115-6126.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Deng W, Puente JL, Gruenheid S, Li Y, Vallance BA, Vazquez A, et al. Dissecting virulence: systematic and functional analyses of a pathogenicity island. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(10):3597–3602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400326101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dean P, Kenny B. The effector repertoire of enteropathogenic E. coli: ganging up on the host cell. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2009;12(1):101–109. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gartner JF, Schmidt MA. Comparative analysis of locus of enterocyte effacement pathogenicity islands of atypical enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 2004;72(11):6722–6728. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.11.6722-6728.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Coombes BK, Wickham ME, Mascarenhas M, Gruenheid S, Finlay BB, Karmali MA. Molecular analysis as an aid to assess the public health risk of non-O157 Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli strains. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74(7):2153–2160. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02566-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Santos AS, Finlay BB. Bringing down the host: enteropathogenic and enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli effector-mediated subversion of host innate immune pathways. Cell Microbiol. 2015;17(3):318–332. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wong AR, Pearson JS, Bright MD, Munera D, Robinson KS, Lee SF, et al. Enteropathogenic and enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli: even more subversive elements. Mol Microbiol. 2011;80(6):1420–1438. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vossenkamper A, Macdonald TT, Marches O. Always one step ahead: how pathogenic bacteria use the type III secretion system to manipulate the intestinal mucosal immune system. J Inflamm. 2011;8:11. doi: 10.1186/1476-9255-8-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Caprioli A, Falbo V, Roda LG, Ruggeri FM, Zona C. Partial purification and characterization of an Escherichia coli toxic factor that induces morphological cell alterations. Infect Immun. 1983;39(3):1300–1306. doi: 10.1128/iai.39.3.1300-1306.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.De Rycke J, Guillot JF, Boivin R. Cytotoxins in non-enterotoxigenic strains of Escherichia coli isolated from feces of diarrheic calves. Vet Microbiol. 1987;15(1–2):137–150. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(87)90139-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.De Rycke J, Gonzalez EA, Blanco J, Oswald E, Blanco M, Boivin R. Evidence for two types of cytotoxic necrotizing factor in human and animal clinical isolates of Escherichia coli. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28(4):694–699. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.4.694-699.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Johnson WM, Lior H. A new heat-labile cytolethal distending toxin (CLDT) produced by Escherichia coli isolates from clinical material. Microb Pathog. 1988;4(2):103–113. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(88)90052-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Watanabe H, Arakawa E, Ito K, Kato J, Nakamura A. Genetic analysis of an invasion region by use of a Tn3-lac transposon and identification of a second positive regulator gene, invE, for cell invasion of Shigella sonnei: significant homology of invE with ParB of plasmid P1. J Bacteriol. 1990;172(2):619–629. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.2.619-629.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Welch RA. Pore-forming cytolysins of gram-negative bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5(3):521–528. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bhakdi S, Bayley H, Valeva A, Walev I, Walker B, Kehoe M, et al. Staphylococcal alpha-toxin, streptolysin-O, and Escherichia coli hemolysin: prototypes of pore-forming bacterial cytolysins. Arch Microbiol. 1996;165(2):73–79. doi: 10.1007/s002030050300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Linhartova I, Bumba L, Masin J, Basler M, Osicka R, Kamanova J, et al. RTX proteins: a highly diverse family secreted by a common mechanism. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2010;34(6):1076–1112. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2010.00231.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Navarro-Garcia F, Eslava C, Villaseca JM, Lopez-Revilla R, Czeczulin JR, Srinivas S, et al. In vitro effects of a high-molecular-weight heat-labile enterotoxin from enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1998;66(7):3149–3154. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.7.3149-3154.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Henderson IR, Nataro JP. Virulence functions of autotransporter proteins. Infect Immun. 2001;69(3):1231–1243. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.3.1231-1243.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Paton AW, Srimanote P, Talbot UM, Wang H, Paton JC. A new family of potent AB(5) cytotoxins produced by Shiga toxigenic Escherichia coli. J Exp Med. 2004;200(1):35–46. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Qu M, Lv B, Zhang X, Yan H, Huang Y, Qian H, et al. Prevalence and antibiotic resistance of bacterial pathogens isolated from childhood diarrhea in Beijing, China (2010–2014) Gut Pathog. 2016;8:31. doi: 10.1186/s13099-016-0116-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Huang Z, Pan H, Zhang P, Cao X, Ju W, Wang C, et al. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance patterns of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli in Shanghai, China. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016;35(8):835–839. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhao JY, Zhang BF, Su J, Xie ZQ, Mu YJ, Huang XY, et al. The etiological and molecular typing research of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli in Henan province in 2013. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2016;50(6):525–529. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-9624.2016.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhu XH, Tian L, Cheng ZJ, Liu WY, Li S, Yu WT, et al. Viral and bacterial etiology of acute diarrhea among children under 5 years of age in Wuhan, China. Chin Med J. 2016;129(16):1939–1944. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.187852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang SX, Yang CL, Gu WP, Ai L, Serrano E, Yang P, et al. Case–control study of diarrheal disease etiology in individuals over 5 years in southwest China. Gut Pathog. 2016;8:58. doi: 10.1186/s13099-016-0141-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yu F, Wang RN, Chen X, Zheng SF, Wang YY, Chen Y. Studies on the serum types and identification efficiency on diarrheagenic Escherichia coli isolated from diarrhea patients, in Zhejiang province. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2017;38(6):800–804. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2017.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Biswas R, Nelson EA, Lewindon PJ, Lyon DJ, Sullivan PB, Echeverria P. Molecular epidemiology of Escherichia coli diarrhea in children in Hong Kong. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34(12):3233–3234. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.12.3233-3234.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Carrico JA, Pinto FR, Simas C, Nunes S, Sousa NG, Frazao N, et al. Assessment of band-based similarity coefficients for automatic type and subtype classification of microbial isolates analyzed by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(11):5483–5490. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.11.5483-5490.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Huang Z, Xu H, Guo JY, Huang XL, Li Y, Hou Q, et al. Assessment and application of a molecular diagnostic method on the detection of four types of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2013;34(6):614–617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zheng S, Yu F, Chen X, Cui D, Cheng Y, Xie G, et al. Enteropathogens in children less than 5 years of age with acute diarrhea: a 5-year surveillance study in the Southeast Coast of China. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16(1):434. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1760-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mandal A, Sengupta A, Kumar A, Singh UK, Jaiswal AK, Das P, et al. Molecular epidemiology of extended-spectrum beta-Lactamase-producing Escherichia coli pathotypes in diarrheal children from low socioeconomic status communities in Bihar, India: emergence of the CTX-M type. Infect Dis. 2017 doi: 10.1177/1178633617739018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Spano LC, da Cunha KF, Monfardini MV, de Fonseca RD, Scaletsky ICA. High prevalence of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli carrying toxin-encoding genes isolated from children and adults in southeastern Brazil. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):773. doi: 10.1186/s12879-017-2872-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ochoa TJ, Ruiz J, Molina M, Del Valle LJ, Vargas M, Gil AI, et al. High frequency of antimicrobial drug resistance of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli in infants in Peru. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;81(2):296–301. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Meraz IM, Arikawa K, Nakamura H, Ogasawara J, Hase A, Nishikawa Y. Association of IL-8-inducing strains of diffusely adherent Escherichia coli with sporadic diarrheal patients with less than 5 years of age. Braz J Infect Dis. 2007;11(1):44–49. doi: 10.1590/S1413-86702007000100012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gomez-Duarte OG, Arzuza O, Urbina D, Bai J, Guerra J, Montes O, et al. Detection of Escherichia coli enteropathogens by multiplex polymerase chain reaction from children’s diarrheal stools in two Caribbean–Colombian cities. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2010;7(2):199–206. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2009.0355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lopes LM, Fabbricotti SH, Ferreira AJ, Kato MA, Michalski J, Scaletsky IC. Heterogeneity among strains of diffusely adherent Escherichia coli isolated in Brazil. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(4):1968–1972. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.4.1968-1972.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lima IF, Boisen N, Quetz Jda S, Havt A, de Carvalho EB, Soares AM, et al. Prevalence of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli and its virulence-related genes in a case–control study among children from north-eastern Brazil. J Med Microbiol. 2013;62(Pt 5):683–693. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.054262-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Carniel E. The Yersinia high-pathogenicity island: an iron-uptake island. Microbes Infect. 2001;3(7):561–569. doi: 10.1016/S1286-4579(01)01412-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jallat C, Livrelli V, Darfeuille-Michaud A, Rich C, Joly B. Escherichia coli strains involved in diarrhea in France: high prevalence and heterogeneity of diffusely adhering strains. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31(8):2031–2037. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.8.2031-2037.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gur C, Coppenhagen-Glazer S, Rosenberg S, Yamin R, Enk J, Glasner A, et al. Natural killer cell-mediated host defense against uropathogenic E. coli is counteracted by bacterial hemolysinA-dependent killing of NK cells. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;14(6):664–674. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wiles TJ, Mulvey MA. The RTX pore-forming toxin alpha-hemolysin of uropathogenic Escherichia coli: progress and perspectives. Future Microbiol. 2013;8(1):73–84. doi: 10.2217/fmb.12.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Guignot J, Chaplais C, Coconnier-Polter MH, Servin AL. The secreted autotransporter toxin, Sat, functions as a virulence factor in Afa/Dr diffusely adhering Escherichia coli by promoting lesions in tight junction of polarized epithelial cells. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9(1):204–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mansan-Almeida R, Pereira AL, Giugliano LG. Diffusely adherent Escherichia coli strains isolated from children and adults constitute two different populations. BMC Microbiol. 2013;13:22. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-13-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Caprioli A, Donelli G, Falbo V, Possenti R, Roda LG, Roscetti G, et al. A cell division-active protein from E. coli. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1984;118(2):587–593. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(84)91343-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bouzari S, Oloomi M, Oswald E. Detection of the cytolethal distending toxin locus cdtB among diarrheagenic Escherichia coli isolates from humans in Iran. Res Microbiol. 2005;156(2):137–144. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Swaminathan B, Barrett TJ, Hunter SB, Tauxe RV, Force CDCPT PulseNet: the molecular subtyping network for foodborne bacterial disease surveillance, United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001;7(3):382–389. doi: 10.3201/eid0703.017303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Noller AC, McEllistrem MC, Pacheco AG, Boxrud DJ, Harrison LH. Multilocus variable-number tandem repeat analysis distinguishes outbreak and sporadic Escherichia coli O157:H7 isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41(12):5389–5397. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.12.5389-5397.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wirth T, Falush D, Lan R, Colles F, Mensa P, Wieler LH, et al. Sex and virulence in Escherichia coli: an evolutionary perspective. Mol Microbiol. 2006;60(5):1136–1151. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05172.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chen Y, Chen X, Zheng S, Yu F, Kong H, Yang Q, et al. Serotypes, genotypes and antimicrobial resistance patterns of human diarrhoeagenic Escherichia coli isolates circulating in southeastern China. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20(1):52–58. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Eichhorn I, Heidemanns K, Semmler T, Kinnemann B, Mellmann A, Harmsen D, et al. Highly virulent non-O157 enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC) serotypes reflect similar phylogenetic lineages, providing new insights into the evolution of EHEC. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;81(20):7041–7047. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01921-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Clermont O, Gordon D, Denamur E. Guide to the various phylogenetic classification schemes for Escherichia coli and the correspondence among schemes. Microbiology. 2015;161(Pt 5):980–988. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.000063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chattaway MA, Dallman T, Okeke IN, Wain J. Enteroaggregative E. coli O104 from an outbreak of HUS in Germany 2011, could it happen again? J Infect Dev Ctries. 2011;5(6):425–436. doi: 10.3855/jidc.2166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Preethirani PL, Isloor S, Sundareshan S, Nuthanalakshmi V, Deepthikiran K, Sinha AY, et al. Isolation, biochemical and molecular identification, and in-vitro antimicrobial resistance patterns of bacteria isolated from bubaline subclinical mastitis in South India. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(11):e0142717. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.CLSI . Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. 27. Wayne: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lau SH, Reddy S, Cheesbrough J, Bolton FJ, Willshaw G, Cheasty T, et al. Major uropathogenic Escherichia coli strain isolated in the northwest of England identified by multilocus sequence typing. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46(3):1076–1080. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02065-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bai X, Zhao A, Lan R, Xin Y, Xie H, Meng Q, et al. Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in yaks (Bos grunniens) from the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau, China. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(6):e65537. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Muller D, Greune L, Heusipp G, Karch H, Fruth A, Tschape H, et al. Identification of unconventional intestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli isolates expressing intermediate virulence factor profiles by using a novel single-step multiplex PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73(10):3380–3390. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02855-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Pass MA, Odedra R, Batt RM. Multiplex PCRs for identification of Escherichia coli virulence genes. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38(5):2001–2004. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.5.2001-2004.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Chakraborty S, Deokule JS, Garg P, Bhattacharya SK, Nandy RK, Nair GB, et al. Concomitant infection of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli in an outbreak of cholera caused by Vibrio cholerae O1 and O139 in Ahmedabad, India. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39(9):3241–3246. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.9.3241-3246.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Antikainen J, Tarkka E, Haukka K, Siitonen A, Vaara M, Kirveskari J. New 16-plex PCR method for rapid detection of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli directly from stool samples. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009;28(8):899–908. doi: 10.1007/s10096-009-0720-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Oh JY, Kang MS, Yoon H, Choi HW, An BK, Shin EG, et al. The embryo lethality of Escherichia coli isolates and its relationship to the presence of virulence-associated genes. Poult Sci. 2012;91(2):370–375. doi: 10.3382/ps.2011-01807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Prorok-Hamon M, Friswell MK, Alswied A, Roberts CL, Song F, Flanagan PK, et al. Colonic mucosa-associated diffusely adherent afaC+ Escherichia coli expressing lpfA and pks are increased in inflammatory bowel disease and colon cancer. Gut. 2014;63(5):761–770. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-304739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Arikawa K, Meraz IM, Nishikawa Y, Ogasawara J, Hase A. Interleukin-8 secretion by epithelial cells infected with diffusely adherent Escherichia coli possessing Afa adhesin-coding genes. Microbiol Immunol. 2005;49(6):493–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2005.tb03754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kyaw CM, De Araujo CR, Lima MR, Gondim EG, Brigido MM, Giugliano LG. Evidence for the presence of a type III secretion system in diffusely adhering Escherichia coli (DAEC) Infect Genet Evol. 2003;3(2):111–117. doi: 10.1016/S1567-1348(03)00008-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Patzi-Vargas S, Zaidi MB, Perez-Martinez I, Leon-Cen M, Michel-Ayala A, Chaussabel D, et al. Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli carrying supplementary virulence genes are an important cause of moderate to severe diarrhoeal disease in Mexico. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9(3):e0003510. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Arikawa K, Nishikawa Y. Interleukin-8 induction due to diffusely adherent Escherichia coli possessing Afa/Dr genes depends on flagella and epithelial Toll-like receptor 5. Microbiol Immunol. 2010;54(9):491–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2010.00244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Paton AW, Paton JC. Multiplex PCR for direct detection of Shiga toxigenic Escherichia coli strains producing the novel subtilase cytotoxin. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(6):2944–2947. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.6.2944-2947.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data of the study can be available upon request from the corresponding author (XJ).