Abstract

Compared to white girls, sexual maturation is accelerated in African American girls as measured by indicators of pubertal development, including age at first menses. Increasing epidemiological evidence suggests that the timing of pubertal development may have strong implications for cardio-metabolic health in adolescence and adulthood. In fact, younger menarcheal age has been related prospectively to poorer cardiovascular risk factor profiles, a worsening of these profiles over time, and an increase in risk for cardiovascular events, including non-fatal incident cardiovascular disease and cardiovascular-specific and all-cause mortality. Yet, because this literature has been limited almost exclusively to white girls/women, whether this same association is present among African American girls/women has not been clarified. In the current narrative review, the well-established vulnerability of African American girls to experience earlier pubertal onset is discussed as are findings from literatures examining the health outcomes of earlier pubertal timing and its antecedents, including early life adversity exposures often experienced disproportionately in African American girls. Gaps in these literatures are highlighted especially with respect to the paucity of research among minority girls/women, and a conceptual framework is posited suggesting disparities in pubertal timing between African American and white girls may partially contribute to well-established disparities in adulthood risk for cardio-metabolic disease between African American and white women. Future research in these areas may point to novel areas for intervention in preventing or lessening the heightened cardio-metabolic risk among African American women, an important public health objective.

Keywords: menarche, puberty, pubertal timing, race, race disparities, cardiovascular disease

Overview

Compared to white girls, African American girls experience more accelerated sexual maturation as assessed by several indicators of pubertal development, including age at first menses (Chumlea et al., 2003; Freedman et al., 2002; Herman Giddens et al., 1997; Wu, Mendola, & Buck, 2002). A growing epidemiological literature suggests that the timing of pubertal onset may be a key determinant of cardio-metabolic health in adolescence and adulthood. Younger menarcheal age has been related prospectively to poorer cardiovascular risk factor profiles, a worsening of these profiles over time, and an increased risk for cardiovascular events, including non-fatal incident cardiovascular disease and cardiovascular-specific and all-cause mortality (G. Cooper et al., 1999; Frontini, Srinivasan, & Berenson, 2003; Jacobsen, Heuch, & Kvale, 2007; Jacobsen, Oda, Knutsen, & Fraser, 2009; Lakshman et al., 2009; Remsberg et al., 2005). To date, however, this literature has focused almost exclusively on white girls/women, limiting our knowledge of whether links between pubertal timing and cardio-metabolic health are also present among African American girls/women.

Understanding such links among African American girls/women is especially important in addressing a timely research question: Does the tendency to experience earlier pubertal onset put African American girls at disproportionate risk for poorer cardio-metabolic health later in life, potentially explaining (at least in part) well-established disparities in adulthood risk for cardio-metabolic disease between African American and white women? Moreover, evidence suggests that some of the risk factors for earlier pubertal onset, including early life adversity exposures, are experienced disproportionately among African American girls. In this context, better understanding race disparities in pubertal timing, their antecedents (e.g., early life adversity), and their potential differential impacts on health is a critical area for future investigation with important public health and health-equity implications for African American women.

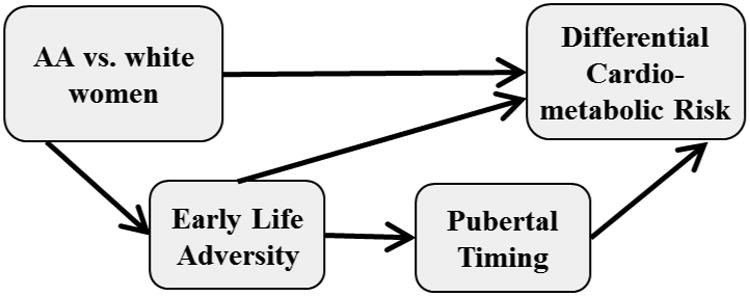

The primary goal of the current review is to provide a narrative examination of the pubertal timing literatures with a specific focus on findings relevant to African American girls/women. The well-established vulnerability of African American girls to experience earlier pubertal onset is discussed as well as findings from literatures examining the antecedents, including early life adversity exposures, and health consequences of earlier pubertal timing. The current review highlights gaps in these literatures especially in relation to the paucity of research among minority girls/women. We posit a conceptual framework that suggests disparities in pubertal timing between African American and white girls may partially contribute to well-established disparities in adulthood risk for cardio-metabolic disease between African American and white women (Figure 1). More specifically, Figure 1 reflects a preliminary model representing one mechanistic pathway (i.e., race [African American vs. white] → early life adversity → pubertal timing → differential cardio-metabolic disease risk) through which race may contribute to differential risk for cardio-metabolic disease between African American and white women.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model representing a mediated pathway through which race effects on differential risk for cardio-metabolic disease between African American and white women may be transmitted.

The secondary goal of the current review is to generate hypotheses for future research studies targeting minority (and especially African-American) girls/women in order to test and further elaborate on the preliminary model proposed here (Figure 1). This review highlights the importance of drawing on life course models, which specifically consider the timing and time course of relevant risk exposures over the life course (Ben-Shlomo & Kuh, 2002; Lynch & Smith, 2005) as well as the potential social patterning of these risk exposures (Smith, Gunnell, & Ben Shlomo, 2001). Building on these literatures, novel hypotheses may be generated that address, for example, whether risk exposures experienced more commonly among African American vs. white girls may account for earlier pubertal onset (cumulative risk model) and/or whether the risk associated with earlier pubertal onset is exacerbated in certain contexts more common among African American vs. white girls (interactional model). In sum, the current review offers a preliminary conceptual framework for considering these and related research questions to begin to better characterize the role pubertal timing may play in explaining observed increases in cardio-metabolic disease risk among African American girls/women.

To aid the reader, here, we describe the organization of the current review: First, we define puberty and the terminology used in the literature to describe aspects of pubertal development, including pubertal timing and tempo. Next, we review parallel findings in two well-established literatures showing race disparities in pubertal timing and cardio-metabolic health. We then review findings in two relevant but incomplete literatures showing earlier pubertal timing may confer risk for poorer cardio-metabolic health and early life adversity may confer risk for earlier pubertal timing. Finally, although speculative, we describe common biological processes that may underlie links between childhood adversity, pubertal timing, and cardio-metabolic health. The organization and review of these literatures, reflecting varying degrees of strength and quality, provide support for the model presented in Figure 1. However, as described above, the relations represented in this model are meant to be hypothesis-generating, requiring future research to clarify the nature of these relations, including whether they are correlational only, possibly causal, or even potentially spurious.

It is also noteworthy that this review considers findings related to girls/women only. To date, studies of pubertal timing in boys are scarce. This is true, in part, because there is no obvious marker of pubertal timing in boys as there is in girls (e.g., menarcheal age), making research in this area more challenging methodologically. Among the limited studies of boys, some findings suggest there may be a relation between earlier pubertal timing and increased cardio-metabolic risk (Hardy, Kuh, Whincup, & Wadsworth, 2006; Hulanicka, Lipowicz, Koziel, & Kowalisko, 2007; Kindblom et al., 2006; Widen et al., 2012) with preliminary data also indicating a potential relation between early life adversity and pubertal timing/tempo (Brown, Cohen, Chen, Smailes, & Johnson, 2004; Negriff, Blankson, & Trickett, 2015). However, findings are mixed with respect to the association between obesity and pubertal timing as well as secular trends in the timing of puberty in boys (Tinggaard et al., 2012). This limited and mixed literature precludes consideration of the proposed model (Figure 1) among boys/men at this time.

Pubertal Timing

Puberty reflects a set of biological processes through which sexual maturation and the potential for human reproduction are achieved. In particular, gonadarche describes the activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis; an increase in the pulsatile release of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) from the hypothalamus signals the release of gonadotropins from the pituitary which, in turn, promotes ovarian follicle maturation and the synthesis of sex steroids that cause the primary physical changes in female puberty, including menarche and ovulation (Ebling, 2005; Plant & Barker-Gibb, 2004). Adrenarche, an independent process typically preceding gonadarche, describes the maturation of the adrenal glands; an increase in androgen production from the adrenal cortex causes pubic hair growth, body odor, and acne (Plant & Barker-Gibb, 2004). In the pubertal timing literature, markers of gonadarche and adrenarche are used to index the timing and the rate of progression (or tempo) through these events, commonly including (but not limited to) age at the onset of breast development (termed “thelarche”), age at the onset of pubic hair growth (termed “pubarche”), and age at the onset of menses (terms “menarche”), with tempo defined as the interval of time in-between these milestones (e.g., in-between pubertal onset and menarche) (Llop-Vinolas et al., 2004; Pantsiotou et al., 2008).

By and large, the majority of studies to date have utilized age at the onset of menses as a marker of female pubertal timing. These studies typically ask adult women to report the age of their first menstrual period retrospectively. Although retrospective, such reports of menarcheal age have been shown to be highly reliable (Bergsten-Brucefors, 1976; Koprowski, Coates, & Bernstein, 2001), with one study showing real-time adolescent reports to correlate .79 with retrospective adulthood reports 33 years later (Must et al., 2002). Fewer studies have included medical provider assessments of Tanner stages (I-V), a well-established system for identifying stages of sexual maturation. In this system, the stages of sexual maturity for breast and pubic hair development are rated separately between stage I (pre-puberty) and stage V (full sexual maturity) based on specified physical characteristics (Marshall & Tanner, 1969). Menarche typically occurs in Tanner stage IV breast development, approximately two to three years after the initiation of breast development (breast budding) (Biro et al., 2006). Notably, support for the use of menarcheal age as a marker of pubertal timing is evidenced by its correlation (r = .53) with pubertal onset (defined as the age at which any evidence of breast or pubic hair development was observed on a physical exam) (Belsky 2007). Throughout the current review, the terms “age at menarche” or “menarcheal age” are used interchangeably. When another indicator of pubertal timing or tempo is available, this indicator is defined accordingly.

Race Differences in Pubertal Timing

Compared to white girls, African American girls experience more accelerated sexual maturation as indicated by observed race differences on several markers of pubertal development, including the initiation of pubic hair and breast development, as well as menarche (Chumlea et al., 2003; Freedman et al., 2002; Herman Giddens et al., 1997; Wu et al., 2002). For example, findings from three large studies, the Bogalusa Heart Study (n = 2,058), the Pediatric Research in Office Settings (PROS) Study (n = 17,066), and the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) (n = 1,623), show the mean age at menarche was 12.3, 12.2, and 12.1 years for African American girls, respectively, whereas the mean age at menarche for white girls was 12.6, 12.9, and 12.7 years, respectively. In these studies, the significant observed race differences in pubertal development were largely independent of body size. That is, in the Bogalusa Heart Study and the PROS Study (Freedman et al., 2002; Herman Giddens et al., 1997), race differences in pubertal development persisted after adjustment for height and weight; and, in the NHANES III (Wu et al., 2002), race differences in pubic hair and breast development (but not menarcheal age) persisted after adjustment for both socioeconomic status and body mass index (BMI). In a more recent analysis, models examining race effects on menarcheal age showed that the inclusion of SES indicators reduced the effect estimates of being African American and Hispanic (versus white) by 40% and 50%, respectively, highlighting the importance of SES-related exposures (Deardorff, Abrams, Ekwaru, & Rehkopf, 2014). Notably, race effects of being African American or being Hispanic (versus white) remained significant, however, though limited statistical power in this study precluded formal testing of differences between these race/ethic groups (Deardorff et al., 2014).

In a recent review, Ramnitz & Lodish (2013) summarized available data from several landmark epidemiological studies (including those referenced above: Bogalusa Heart Study, the PROS Study, and the NHANES III) to examine race differences in pubertal development as well as how these differences have changed over time. A consensus panel examining data between years 1940 to 1994 confirmed a secular trend in the US in which the ages at breast development and menarche declined over time (Euling et al., 2008); due to the underrepresentation of minority girls in older studies, however, fewer data were available to definitively address how this secular trend may differ across race/ethnic groups. Nonetheless, the data available to date are intriguing. For example, in the Bogalusa Heart Study, the median menarcheal age of white girls decreased by 2.0 months over a 20-year study period compared to a 9.5-month decrease for African American girls (Freedman et al., 2002). Similarly, another study documented a smaller decline in median menarcheal age over time for white girls (3.24-month decline) compared to African American girls (5.84-month decline) (Ramnitz & Lodish, 2013). In contrast, with respect to thelarche, age at the onset of breast development was significantly earlier (9.62 versus 9.96 years) for white girls in the more recent Breast Cancer and the Environment Research Program (BCERP, 2004-2008) compared to the older PROS Study (1992-1993), but no historical differences in thelarche were observed for African American girls (Biro et al., 2013). In summary, these findings, at least with respect to menarche, frame the possibility that African American girls, compared to white girls, not only experience pubertal onset at younger ages but may also show sharper decreases in the age of pubertal onset over time.

Race Differences in Cardio-Metabolic Disease Risk

The proposed conceptual model (Figure 1) aims to explain (in part) the well-established race disparities in adulthood risk for cardio-metabolic disease between African American and white women. In this context, we describe the current literature pertaining to these disparities. Specifically, we briefly summarize the literature regarding race differences in cardiovascular risk factors, preclinical atherosclerotic disease, and incident cardiovascular events.

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in all women as well as in all major race/ethnic subgroups of women in the US (Day, 1996; Rosamond et al., 2007; Y. Zhang, 2010). An abundant literature suggests there are race/ethnic differences in cardiovascular risk factors, markers of preclinical atherosclerotic disease, and incident cardiovascular events, with a general pattern showing increased risk among African American women compared to white women. With respect to cardiovascular risk factors, this pattern has been observed for anthropometric indicators (Matthews et al., 2005; Mensah, Mokdad, Ford, Greenlund, & Croft, 2005; Winkleby, Kraemer, Ahn, & Varady, 1998), lipid profiles (Jha et al., 2003; Matthews et al., 2005), insulin resistance (Giles, Kittner, Hebel, Losonczy, & Sherwin, 1995; Jha et al., 2003; Matthews et al., 2005; Winkleby et al., 1998), blood pressure (Burt et al., 1995; R. S. Cooper, Liao, & Rotimi, 1996; Cornoni-Huntley, Lacroix, & Havlik, 1989; Giles et al., 1995; Jha et al., 2003; Johnson, Heineman, Heiss, Hames, & Tyroler, 1986; Lloyd-Jones et al., 2005; Matthews et al., 2005; Mensah et al., 2005; Nesbitt, 2004; Winkleby et al., 1998), and systemic inflammation (Albert, Glynn, Buring, & Ridker, 2004; Kelley-Hedgepeth et al., 2008; Khera et al., 2005; Matthews et al., 2005; Nazmi & Victora, 2007). Increased risk among African American women has also been observed for preclinical atherosclerotic disease (Janssen et al., 2012; Lewis et al., 2009; Ohira et al., 2012; Ranjit et al., 2006), including carotid artery IMT and aortic/coronary calcification as well as incident disease (Giles et al., 1995; Gillum, Mussolino, & Madans, 1997; Johnson et al., 1986; Mensah et al., 2005; Roger et al., 2011; Rosamond et al., 2007), including cardiac-related hospitalizations, myocardial infarction, stroke, and cardiac-specific death. With a few exceptions (Karlamangla, Merkin, Crimmins, & Seeman, 2010; Scuteri et al., 2008), the vast majority of studies show the effects of race/ethnicity on cardiovascular risk persist independently of statistical control for covariates including SES, although it is widely accepted that variability in SES across race/ethnic groups explains a significant proportion of these effects (e.g.(Matthews et al., 2005)).

Pubertal Timing and Health

The proposed conceptual model (Figure 1) depicts a potential pathway between pubertal timing and differential risk for cardio-metabolic health between African American and white women. In this context, we describe the current literature relating pubertal timing to both cardio-metabolic risk factors and cardiovascular-related incident events. Thereafter, we highlight that this literature is primarily limited to white girls/women with two notable exceptions (Feng et al., 2008; Frontini et al., 2003).

Pubertal timing and cardio-metabolic risk factors

Longitudinal investigations have shown that earlier pubertal timing, typically indexed by self-reports of menarcheal age, predicts adulthood obesity and type 2 diabetes (Hardy et al., 2006; He et al., 2010; Laitinen, Power, & Jarvelin, 2001; Lakshman et al., 2008). Younger menarcheal age has also been related prospectively to a host of cardiovascular risk factors in adolescence and adulthood as well as to a worsening of these risk factors over time (Feng et al., 2008; Frontini et al., 2003; Hoyt & Falconi, 2015; Hulanicka et al., 2007; Kivimaki et al., 2008; Lakshman et al., 2009; Pierce, Kuh, & Hardy, 2010; Remsberg et al., 2005; Widén et al., 2012). For example, girls with earlier menarche, defined at the 25th percentile or less (11.9 years), experienced greater increases in insulin, glucose, systolic blood pressure (SBP), and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) over the 13-year study period (ages 8 to 21); these changes were observed independently of correlated changes in body composition (marked by indicators: fat-free mass and percent body fat) (Remsberg et al., 2005). Similarly, girls with an earlier menarche (<12 years) experienced greater fasting insulin levels in periods of childhood (5-11), adolescence (12-18 years), and adulthood (19-37 years), greater homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) levels in periods of childhood and adolescence, and greater increases in insulin and HOMA-IR over time; in analyses also including indicators of body composition, earlier menarche was related independently to body fatness and insulin (Frontini et al., 2003). Finally, girls with earlier menarche were at increased odds of experiencing a clustering of cardio-metabolic risk factors in adulthood defined as having 3 or 4 metabolic syndrome components (across components: BMI, fasting insulin, SBP, total cholesterol to HDL ratio) (Frontini et al., 2003).

Pubertal timing and cardiovascular-related incident events

Younger menarcheal age has similarly been related prospectively to cardiovascular-related incident events, including incident cardiovascular disease, incident coronary heart disease, cardiovascular-specific mortality, and all-cause mortality (G. Cooper et al., 1999; Hoyt & Falconi, 2015; Jacobsen et al., 2007; Jacobsen et al., 2009; Lakshman et al., 2009). Associations have been observed in large samples (e.g., 61,319 women) and over long periods of follow-up (e.g., up to 37 years) (Jacobsen et al., 2007). Moreover, associations between younger menarcheal age and cardiovascular-related incident events have been observed even after adjusting for a myriad of covariates, including SES, health behaviors, reproductive factors, and markers of body composition (e.g. BMI, waist circumference) (Lakshman et al., 2009). By and large, findings relating pubertal timing both to cardiovascular risk factors and to cardiovascular events, do not appear to be attributable to variability in body composition (G. Cooper et al., 1999; Feng et al., 2008; Frontini et al., 2003; Hulanicka et al., 2007; Jacobsen et al., 2007; Jacobsen et al., 2009; Lakshman et al., 2009; Remsberg et al., 2005; Widén et al., 2012), although, in a minority of studies, associations between pubertal timing and cardiovascular risk outcomes were attenuated after adjustment for BMI (Kivimaki et al., 2008; Pierce et al., 2010).

Although the extant findings to date generally document a relation between pubertal timing and cardiovascular risk, these studies have focused almost entirely on white girls/women. That is, the studies represented in this literature include ones that have limited their analyses to the examination of white girls/women only (e.g., Adventist Health Study; Fels Longitudinal Study (Jacobsen et al., 2009; Remsberg et al., 2005)); studies that are almost entirely comprised of white girls/women (e.g., Nurses' Health Study (He et al., 2010)); and studies, some birth cohorts, of white women conducted in European countries, including England, Finland, Poland and Norway (Hardy et al., 2006; Hulanicka et al., 2007; Jacobsen et al., 2007; Kivimaki et al., 2008; Pierce et al., 2010; Widen et al., 2012). Two notable exceptions include a study of Chinese women in which the predicted relation between earlier pubertal timing and poorer cardio-metabolic health was also observed (Feng et al., 2008) and the Bogalusa Heart Study, comprised of 65% white and 35% African American women (Frontini et al., 2003). The Bogalusa Heart Study was unique in that it included a subset of African American women sizable enough to be analyzed separately, with findings suggesting that, in both white and African American women, younger menarcheal age predicted the development of a clustering of adverse levels of metabolic syndrome components in adulthood (Frontini et al., 2003).

In summary, study findings strongly suggest that the timing of pubertal development has important impacts on cardio-metabolic health that begin in adolescence and extend into adulthood, possibly accounting for significant disease-related morbidity and mortality in later life. This literature points to the processes of pubertal development in playing a possible mechanistic role in promoting risk for cardio-metabolic disease, but is limited by its almost exclusive focus on girls/women of white backgrounds. This is particularly problematic given the notable finding that African American girls, compared to white girls, experience more accelerated pubertal development. As such, it is imperative to gain a better understanding of how the experience of having an earlier pubertal onset may place African American girls at disproportionate risk for poorer cardio-metabolic health.

Early Life Adversity and Pubertal Timing

The proposed conceptual model (Figure 1) depicts a potential pathway between early life adversity and pubertal timing as a mechanism through which race effects on differential risk for cardio-metabolic disease between African American and white women may be (partially) transmitted. In this context, we describe the unique challenges faced by African American girls/women that may put them at disproportionate risk for early life adversity exposures. Next, we describe the current literature relating early life adversity exposures to pubertal timing as well as this literature's major shortcoming that it is primarily limited to white girls/women. Finally, findings are discussed in the context of life course models, including the “weathering” hypothesis (Geronimus, 1992; Geronimus et al., 2010), to provide conceptual framing for future research questions to test and further elaborate on the preliminary proposed model (Figure 1). It is suggested that such models should consider the timing and time course of relevant risk exposures over the life course (Ben-Shlomo & Kuh, 2002; Lynch & Smith, 2005) as well as the potential social patterning of these risk exposures (Smith et al., 2001).

Early life adversity in African American populations

Early life adversity has been defined variably across studies. Here, we use the term “early life adversity” in reference to a range of family-based, socioeconomic, and race-based hardships experienced in the pre-pubertal period. Evidence that African American girls are disproportionately burdened by adversity exposures in early life is suggested by data from the U.S. Census Bureau, estimating that poverty rates are more than twice as high for African American compared to white families (26% versus 12%, respectively) (Macartney, Bishaw, & Fontenot, 2013). In the 100 largest US metropolitan areas, the vast majority (76%) of African American children lived in neighborhoods that were more impoverished than the neighborhoods of the “worst-off” white children (i.e., top 25% of poverty distribution) (Acevedo-Garcia, Osypuk, McArdle, & Williams, 2008). Accounting for these poverty-related findings, at least in part, rates of mother-only family groups were found to be three times higher for African American versus white families (29% and 10%, respectively) (Vespa, Lewis, & Kreider, 2013).

In a recent review, Williams (Williams, 2012) describes how such difficult circumstances may contribute to observed race disparities in health. Williams (2012) details evidence that (compared to white) African Americans experience 1) increased prevalence rates in 10 of the 15 major causes of death; 2) earlier onset and poorer prognosis of numerous diseases, including CVD (Jolly, Vittinghoff, Chattopadhyay, & Bibbins-Domingo, 2010); and 3) greater impacts of risk exposures even when the exposures are similar to their white counterparts (e.g., smoking) (Berger, Lund, & Brawley, 2007). Experiences, often unique to African Americans, such as institutional racism (e.g., residential segregation) and personal experiences of discrimination may operate 1) by limiting access to resources and opportunities for improved health; 2) by increasing exposures to other health-damaging stressors especially in contexts of concentrated poverty (e.g., unemployment, single parenthood, social disorder, and violence) (Massey, 1995, 2004); and 3) by potentiating risk in so far as high baseline levels of psychosocial stress may intensify the impacts of other risk exposures (e.g., environment pollutants) (Gee & Payne-Sturges, 2004).

Linking early life adversity and pubertal timing

Study findings show that, in addition to established risk factors for earlier pubertal onset, including larger pre-pubertal body size and younger maternal menarcheal age (Ahmed, Ong, & Dunger, 2009; Brooksgunn & Warren, 1988; Lassek & Gaulin, 2007; Sloboda, Hart, Doherty, Pennell, & Hickey, 2007; Towne et al., 2005), family-related adversity exposures have an independent effect on pubertal timing and tempo. In longitudinal studies, girls who experienced greater adversity in early life had an earlier pubertal onset and faster rate of pubertal development; some of these early life adversity experiences included exposures to marital conflict, father absence, negative parenting practices, parent-child relationship difficulties, and greater socioeconomic disadvantage as well as fewer positive parenting and family-based interactions (Belsky, Houts, & Fearon, 2010; Belsky, Steinberg, Houts & Halpern-Felsher, 2010; Belsky et al., 2007; Campbell & Udry, 1995; Deardorff et al., 2011; Ellis & Essex, 2007; Ellis & Garber, 2000; Ellis, McFadyen-Ketchum, Dodge, Pettit, & Bates, 1999; Ellis, Shirtcliff, Boyce, Deardorff, & Essex, 2011; Graber, Brooksgunn, & Warren, 1995; Moffitt Caspi, Belsky, & Silva, 1992; Saxbe & Repetti, 2009; Wierson, Long, & Forehand, 1993).

Specifically, in the Wisconsin Study of Families, lower parental support and greater marital conflict predicted earlier adrenarche (indexed by higher salivary dehydroepiandrosterone [DHEA] levels, a steroid hormone produced by the adrenal glands), while lower parental support and lower SES predicted earlier breast development (Ellis & Essex, 2007). In the NICHD Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development (SECCYD), harsh/controlling parenting predicted earlier menarche (Belsky, Steinberg, et al., 2010; Belsky et al., 2007), whereas the classification of insecure (vs. secure) infant-mother attachment style at 15 months predicted earlier initiation and completion of puberty as well as earlier menarche (Belsky, Houts, et al., 2010). Earlier initiation of puberty was coded dichotomously as any evidence of breast or pubic hair development and completion of puberty was coded dichotomously as completed breast or pubic hair development, both using Tanner staging data (Belsky, Houts, et al., 2010). Moreover, a sizable collection of cross-sectional studies show similar associations between early life adversity exposures and earlier/faster pubertal maturation (Bleil et al., 2013; Hoier, 2003; Kim & Smith, 1998; Kim, Smith, & Palermiti, 1997; Maestripieri, Roney, DeBias, Durante, & Spaepen, 2004; Manuck, Craig, Flory, Halder, & Ferrell, 2011; Quinlan, 2003; Romans, Martin, Gendall, & Herbison, 2003).

The literature examining the familial antecedents of pubertal timing, however, is almost exclusively limited to white girls. Studies in this literature have typically excluded African Americans or African American participants have represented such a small proportion of the total sample that they could not be analyzed separately (Belsky et al., 2007; Ellis & Essex, 2007; Ellis & Garber, 2000; Ellis et al., 1999; Graber et al., 1995; Saxbe & Repetti, 2009; Wierson et al., 1993). As a result, whether early life adversity experiences confer risk for earlier pubertal onset and faster pubertal development in African American girls remains inconclusive, as do possible race/ethnic differences in the link between early life adversity and pubertal timing/tempo. This gap in the literature is especially problematic as there are particular early life adversity exposures (described above) that African American girls experience disproportionately and, therefore, may put these girls at increased risk for an earlier pubertal onset and, by extension, poorer cardio-metabolic health.

Although this literature emphasizes family relationships in explaining why some girls experience puberty earlier than their same-age peers, it is notable that Belsky et al. (Belsky, Steinberg, & Draper, 1991) have suggested that greater contextual stress in the family, including lower SES, may accelerate sexual maturation as well via the promotion of more problematic family relationships. More broadly, life history theories posit that, in early life, sexual maturation is shaped by the availability of resources in the environment (Chisholm, 1993; Ellis, 2004; Ellis, Figueredo, Brumbach, & Schlomer, 2009), elements of which would be marked by the family's socioeconomic standing. In fact, in previous studies, lower SES in childhood was related to earlier pubertal onset indexed by pubic hair and breast development (measured as a composite of mother and daughter ratings using Tanner staging sketches and mother reports on the Pubertal Development Scale (Petersen, Crockett, Richards, & Boxer, 1988)) (Ellis & Essex, 2007) as well as younger age at menarche (Campbell & Udry, 1995).

Findings are not entirely consistent, however, as null findings have been reported as well (Ellis & Garber, 2000; Ellis et al., 1999; Moffitt et al., 1992). Research is also mixed with respect to whether SES in childhood correlates with the quality of family relationships. For example, Ellis et al. (Ellis et al., 1999) found that lower SES was related to a host of problematic outcomes such as harsher discipline, greater marital conflict, and less mother-daughter affection/positivity, but in other work, SES was unrelated to similar family-related variables (e.g., father absence, marital stress, problematic family relationships) (Ellis & Garber, 2000). The role of family- and SES-related adversity exposures in relation to pubertal timing, thus, is an area in need of further clarification, especially among African American girls in whom poverty-related risk exposures are more prevalent.

Early life adversity and adulthood health

A growing number of studies document links between early life adversity exposures and risk for poorer cardio-metabolic health in adulthood. Reviews of this literature show early life adversity exposures are related to CVD-specific outcomes (CHD, stroke, angina, and atherosclerosis) (Galobardes, Smith, & Lynch, 2006) as well as all-cause and disease-specific mortality (Galobardes, Lynch, & Smith, 2004, 2008). Early life adversity exposures have also been linked to intermediate health outcomes, including adulthood risk for obesity and central adiposity, conventional cardiovascular risk factors, and incident metabolic syndrome and Type 2 diabetes (Alastalo et al., 2013; Danese et al., 2009; Janicki-Deverts, Cohen, Matthews, & Jacobs, 2012; Lehman, Taylor, Kiefe, & Seeman, 2005, 2009; Midei & Matthews, 2011; Midei, Matthews, Chang, & Bromberger, 2013; Rich-Edwards et al., 2010; Riley, Wright, Jun, Hibert, & Rich-Edwards, 2010). Interestingly, effect sizes are sometimes largest in samples of women (Wegman & Stetler, 2009) and in some studies associations were present in women only (Galobardes et al., 2006). To date, the pathways potentially explaining observed links between early life adversity and adulthood health have not been elucidated. In the current review, we focus on pubertal timing (known to be influenced by pre-pubertal adversity exposures) as a mediated pathway (Figure 1) through which race effects on differential risk for cardio-metabolic disease in adult women may be (partially) transmitted. However, the current model is not meant to exclude consideration of other mediated pathways or possible direct links between early life adversity exposures and adulthood health.

Utilizing life course models in understanding adulthood health

Seeking to explain variability in the emergence of poor health and disease in adulthood, life course epidemiology, as detailed in Lynch & Smith (Lynch & Smith, 2005), considers the timing and time course of relevant risk exposures over the life course—inclusive of a range of socio-environmental factors (Ben-Shlomo & Kuh, 2002). In this framework, life course models have focused on critical and sensitive periods (e.g., in utero, puberty) during which times the occurrence of risk exposures are hypothesized to be particularly salient if not determinative (Barker, 1992; Bleil et al., 2015; Jasik & Lustig, 2008) as well as on the accumulation of risk exposures, accounting for the number of risk exposures, their duration, sequence (“chains of risk”), and potential clustering (Goosby, Cheadle, & McDade, 2016; Kuh, Ben-Shlomo, Lynch, Hallqvist, & Power, 2003; Lynch & Smith, 2005). But no matter the specific conceptual emphasis of a given life course model, it is widely accepted across these models that such risk exposures do not occur at random but rather are socially patterned (Smith et al., 2001). As such, these models may help to explain profound social and racial inequalities in health both at the individual and population levels.

The “weathering” hypothesis in particular proposes that stress exposures, many experienced disproportionately (and some uniquely—i.e., racial discrimination) in marginalized groups, may accumulate over time, resulting in excessive wear and tear on the body and subsequent increased risk for poor health and disease (Geronimus, 1992; Geronimus et al., 2010). In fact, a growing body of evidence documents associations between experiences of racial discrimination and deleterious health outcomes among African Americans (Goosby & Heidbrink, 2013; Goosby, Malone, Richardson, Cheadle, & Williams, 2015). Future research would be well served to leverage these life course models in considering how the experiences of African American girls in early life may independently, in sequence, and/or in interaction with other social and biological risk factors promote race disparities in pubertal onset and subsequent cardio-metabolic disease. As an example, leveraging of the “weathering” hypothesis may raise alternate interpretations of the proposed model (Figure 1) by suggesting that pubertal development is not a mechanism per se but rather that accelerated biological aging may simply shift concomitant trajectories of pubertal and cardio-metabolic disease development downwardly. This is highlighted as an example only regarding how existing life course models may be applied in the context of the current review.

In summary, study findings are strongly suggestive that, even independently of well-established risk factors for earlier pubertal onset (i.e., pre-pubertal BMI), early life adversity exposures may promote trajectories of earlier/faster pubertal maturation. This literature is important in pointing to modifiable, family-based risk factors that appear to set the stage for pubertal development and possible future risk for cardio-metabolic disease. It is limited, however, by its almost exclusive focus on white girls. This is true despite a robust literature suggesting African American girls are disproportionately burdened by early life adversity exposures especially with respect to poverty-related hardships which may be promoted and/or exacerbated by experiences of institutional racism and discrimination (Massey, 2004; Williams, 2012). In this context, it is imperative to more fully understand how the early life adversity experiences, including a range of family- and SES-related stressors that African American girls face, may contribute to their risk for earlier pubertal onset and subsequent cardio-metabolic disease. In addition, consideration of these relations would be best addressed in the context of life course models which provide a framework for examining the timing and time course of risk exposures as well as their social patterning, both in explaining variations in the emergence of disease generally (Ben-Shlomo & Kuh, 2002; Lynch & Smith, 2005; Smith et al., 2001) as well as in explaining race disparities in the emergence of disease (Geronimus, 1992; Geronimus et al., 2010).

Biological Mechanisms Linking Childhood Adversity, Pubertal Timing, and Cardio-metabolic Health

The study findings described in this review raise the possibility that variations in pubertal development have consequential and lasting impacts on adulthood health. However, why the biological underpinnings of puberty, when experienced earlier versus later and/or at differing rates, promote cardio-metabolic disease in adulthood remains unknown. Although speculative, it is possible that the critical organizational processes that occur during puberty may be disrupted under circumstances of higher pre-pubertal risk—including greater early life adversity—inalterably affecting the course of sexual maturation and associated hormonal and metabolic factors relevant to the development of adulthood cardio-metabolic diseases. Specific mechanisms relevant to the role of pubertal development in cardio-metabolic health include obesity, insulin resistance, and inflammation-related processes. Evidence supporting a role for these processes as potential biological mechanisms in explaining links between early life adversity, pubertal timing, and cardio-metabolic health is described below.

First, with respect to the role of insulin resistance, study findings show markers of early life adversity are related prospectively to obesity, insulin resistance, glycemic control (in non-diabetic persons), incident metabolic syndrome, as well as type 2 diabetes (Midei & Matthews, 2011; Midei et al., 2013; Rich-Edwards et al., 2010; Widom, Czaja, Bentley, & Johnson, 2012). In addition, earlier pubertal timing has been shown to predict post-pubertal weight gain and greater increases in insulin resistance over time, even independently of pre-pubertal body mass (Frontini et al., 2003; Remsberg et al., 2005). Finally, evidence shows obesity, central adiposity, and insulin resistance predict type 2 diabetes and CVD morbidity and mortality (Carey et al., 1997; Janssen, Katzmarzyk, & Ross, 2002; Lapidus et al., 1984; Ogden, Yanovski, Carroll, & Flegal, 2007).

Second, with respect to the role of inflammation, study findings show markers of early life adversity are related prospectively to higher levels of inflammation in adolescence and adulthood (Danese et al., 2009; Danese, Pariante, Caspi, Taylor, & Poulton, 2007; G. Miller & Chen, 2007; G. E. Miller & Chen, 2010; Slopen, Kubzansky, McLaughlin, & Koenen, 2013; Slopen et al., 2010). In addition, younger menarcheal age as well as smaller gains in height over time (an indirect marker of faster pubertal tempo) has been related to higher C-reactive protein (CRP) levels (Clancy, Klein, et al., 2013; McDade, Reyes-Garcia, Tanner, Huanca, & Leonard, 2008; S. M. M. Zhang et al., 2007). More generally, common reproductive functions such as ovulation involve inflammatory processes (Clancy, Baerwald, & Pierson, 2013; Critchley, Kelly, Brenner, & Baird, 2001; Espey, 1980).

Finally, evidence suggests inflammation may be a causal factor in promoting hypertension, insulin resistance, and atherosclerosis, leading to longer-term disease outcomes such as diabetes and CVD (Black, 2003; Hotamisligil, 2006; Libby & Theroux, 2005; Pradhan, Manson, Rifai, Buring, & Ridker, 2001; Pradhan & Ridker, 2002; Ridker, Hennekens, Buring, & Rifai, 2000; Ridker, Rifai, Stampfer, & Hennekens, 2000). Taken together, these findings suggest future studies should consider how variations in the biology of pubertal timing may overlap with metabolic and inflammatory processes possibly explaining links to cardio-metabolic health. Such studies of shared biological underpinnings should be examined in the context of life course models in which correlated trajectories of risk are considered over time.

Summary and Conclusions

In summary, African American (compared to white) girls experience more accelerated sexual maturation as marked by indicators of earlier pubertal timing. A growing epidemiological literature suggests that earlier pubertal timing may be a key risk factor for poorer cardio-metabolic health in adolescence and adulthood. To date, however, studies have focused almost exclusively on white girls/women, limiting our knowledge of whether associations between pubertal timing and cardio-metabolic health are also present among African American girls/women. This omission is striking given the well-established observation that African American (compared to white) women are at considerable increased risk for cardio-metabolic disease.

In this context, the current review posed the question: Does the tendency to experience an earlier pubertal onset put African American girls at disproportionate risk for poorer cardio-metabolic health, potentially explaining (at least in part) well-established disparities in adulthood risk for cardio-metabolic disease between African American and white women? Moreover, evidence suggests that some of the risk factors for earlier pubertal onset, including early life adversity exposures, are experienced disproportionately among African American girls. In Figure 1, a conceptual framework is presented representing one mechanistic pathway (i.e., race [African American vs. white] → early life adversity → pubertal timing → differential cardio-metabolic disease risk) through which race effects on differential risk for cardio-metabolic disease between African American and white women may be (partially) transmitted. We suggest that future investigations be conducted that draw on life course models to examine the timing, time course, and social patterning of risk factors among African American girls/women that may help elucidate the role of pubertal maturation in explaining long-standing race disparities in cardio-metabolic health. Studies, some existing already (e.g., The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health), that have some, if not all, of the necessary data should begin to test and elaborate on the proposed conceptual model (Figure 1). Ultimately, these efforts may point to novel areas for intervention in preventing or lessening cardio-metabolic risk in African American girls/women, an important public health objective.

Acknowledgments

Funding source: The preparation of this manuscript was supported by the sponsors of the meeting “How the Social Environment Gets Under the Skin – Developmental Perspectives” held on June 17-18, 2015 in Bethesda, MD, including the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) of the United Kingdom, and the Research Councils United Kingdom (RCUK); as well as the grant NIH/NIA (K08 AG03575).

Footnotes

The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- Acevedo-Garcia D, Osypuk TL, McArdle N, Williams DR. Toward a policy-relevant analysis of geographic and racial/ethnic disparities in child health. Health Affairs. 2008;27(2):321–333. doi: 10.1077/hlthaff.27.2.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed ML, Ong KK, Dunger DB. Childhood obesity and the timing of puberty. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2009;20(5):237–242. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alastalo H, Raikkonen K, Pesonen AK, Osmond C, Barker DJP, Heinonen K, et al. Eriksson JG. Early life stress and blood pressure levels in late adulthood. Journal of Human Hypertension. 2013;27(2):90–94. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2012.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert MA, Glynn RJ, Buring J, Ridker PM. C-reactive protein levels among women of various ethnic groups living in the United States - (from the Women's Health Study) American Journal of Cardiology. 2004;93(10):1238–1242. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.01.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker DJP. The Fetal and Infant Origins of Adult Disease. 1st. London: British Medical Journal Books; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Houts RM, Fearon RMP. Infant attachment security and the timing of puberty: testing an evolutionary hypothesis. Psychological Science. 2010;21(9):1195–1201. doi: 10.1177/0956797610379867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Steinberg L, Draper P. Childhood experience, interpersonal development, and reproductive strategy - an evolutionary theory of socialization. Child Development. 1991;62(4):647–670. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Steinberg L, Houts RM, Halpern-Felsher BL. The development of reproductive strategy in females: early maternal harshness -> earlier menarche -> increased sexual risk taking. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46(1):120–128. doi: 10.1037/a0015549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Steinberg LD, Houts RM, Friedman SL, DeHart G, Cauffman E, et al. Susman E. Family rearing antecedents of pubertal timing. Child Development. 2007;78(4):1302–1321. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shlomo Y, Kuh D. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology: conceptual models, empirical challenges and interdisciplinary perspectives. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2002;31(2):285–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger M, Lund M, Brawley O. Racial disparities in lung cancer. Current Problems in Cancer. 2007;31(3):202–210. doi: 10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergsten-Brucefors A. Accuracy of recalled age at menarche. Annals of Human Biology. 1976;3(1):71–73. doi: 10.1080/03014467600001151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biro FM, Greenspan LC, Galvez MP, Pinney SM, Teitelbaum S, Windham GC, et al. Wolff MS. Onset of Breast Development in a Longitudinal Cohort. Pediatrics. 2013;132(6):1019–1027. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-3773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biro FM, Huang B, Crawford PB, Lucky AW, Streigel-Moore R, Barton BA, Daniels S. Pubertal correlates in black and white girls. Journal of Pediatrics. 2006;148(2):234–240. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black PH. The inflammatory response is an integral part of the stress response: Implications for atherosclerosis, insulin resistance, type II diabetes and metabolic syndrome X. Brain Behavior and Immunity. 2003;17(5):350–364. doi: 10.1016/s0889-1591(03)00048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleil ME, Adler NE, Appelhans BM, Gregorich SE, Sternfeld B, Cedars MI. Childhood adversity and pubertal timing: Understanding the origins of adulthood cardiovascular risk. Biological Psychology. 2013;93(1):213–219. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleil ME, Appelhans BM, Latham MD, Irving MA, Gregorich SE, Adler NE, Cedars MI. Neighborhood socioeconomic status during childhood versus puberty in relation to endogenous sex hormone levels in adult women. Nursing Research. 2015;64(3):211–220. doi: 10.1097/nnr.0000000000000096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooksgunn J, Warren MP. Mother daughter differences in menarcheal age in adolescent girls attending national dance company schools and non-dancers. Annals of Human Biology. 1988;15(1):35–44. doi: 10.1080/03014468800009441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J, Cohen P, Chen H, Smailes E, Johnson JG. Sexual trajectories of abused and neglected youths. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2004;25(2):77–82. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200404000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt VL, Whelton P, Roccella EJ, Brown C, Cutler JA, Higgins M, et al. Labarthe D. Prevalence of hypertension in the US adult population - results from the 3rd National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1991. Hypertension. 1995;25(3):305–313. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.25.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell BC, Udry JR. Stress and age at menarche of mothers and daughters. Journal of Biosocial Science. 1995;27(2):127–134. doi: 10.1017/s0021932000022641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey VJ, Walters EE, Colditz GA, Solomon CG, Willett WC, Rosner BA, et al. Manson JE. Body fat distribution and risk of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in women - The Nurses' Health Study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1997;145(7):614–619. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm JS. Death, hope, and sex - life history theory and the development of reproductive strategies. Current Anthropology. 1993;34(1):1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Chumlea WC, Schubert CM, Roche AF, Kulin HE, Lee PA, Himes JH, Sun SS. Age at menarche and racial comparisons in US girls. Pediatrics. 2003;111(1):110–113. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clancy KBH, Baerwald AR, Pierson RA. Systemic inflammation is associated with ovarian follicular dynamics during the human menstrual cycle. Plos One. 2013;8(5):8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clancy KBH, Klein LD, Ziomkiewicz A, Nenko I, Jasienska G, Bribiescas RG. Relationships between biomarkers of inflammation, ovarian steroids, and age at menarche in a rural polish sample. American Journal of Human Biology. 2013;25(3):389–398. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.22386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper G, Ephross S, Weinberg C, Baird D, Whelan E, Sandler D. Menstrual and reproductive risk factors for ischemic heart disease. Epidemiology. 1999;10(3):255–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper RS, Liao YL, Rotimi C. Is hypertension more severe among US blacks, or is severe hypertension more common? Annals of Epidemiology. 1996;6(3):173–180. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(96)00009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornoni-Huntley J, Lacroix AZ, Havlik RJ. Race and sex differentials in the impact of hypertension in the United States - the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey-I Epidemiology Follow-up Study. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1989;149(4):780–788. doi: 10.1001/archinte.149.4.780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critchley HOD, Kelly RW, Brenner RM, Baird DT. The endocrinology of menstruation - a role for the immune system. Clinical Endocrinology. 2001;55(6):701–710. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2001.01432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danese A, Moffitt TE, Harrington H, Milne BJ, Polanczyk G, Pariante CM, et al. Caspi A. Adverse childhood experiences and adult risk factors for age-related disease depression, inflammation, and clustering of metabolic risk markers. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2009;163(12):1135–1143. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danese A, Pariante CM, Caspi A, Taylor A, Poulton R. Childhood maltreatment predicts adult inflammation in a life-course study. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104(4):1319–1324. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610362104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day JC. Population projections of the United States by age, sex, race, and Hispanic origin: 1995-2050. Washington (DC): US Bureau of the Census; 1996. Document P25-1130. [Google Scholar]

- Deardorff J, Abrams B, Ekwaru JP, Rehkopf DH. Socioeconomic status and age at menarche: an examination of multiple indicators in an ethnically diverse cohort. Annals of Epidemiology. 2014;24(10):727–733. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2014.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deardorff J, Ekwaru JP, Kushi LH, Ellis BJ, Greenspan LC, Mirabedi A, et al. Hiatt RA. Father absence, body mass index, and pubertal timing in girls: differential effects by family income and ethnicity. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2011;48(5):441–447. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebling FJP. The neuroendocrine timing of puberty. Reproduction. 2005;129(6):675–683. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BJ. Timing of pubertal maturation in girls: An integrated life history approach. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130(6):920–958. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.6.920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BJ, Essex MJ. Family environments, adrenarche, and sexual maturation: A longitudinal test of a life history model. Child Development. 2007;78(6):1799–1817. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BJ, Figueredo AJ, Brumbach BH, Schlomer GL. Fundamental dimensions of environmental risk. Human Nature-an Interdisciplinary Biosocial Perspective. 2009;20(2):204–268. doi: 10.1007/s12110-009-9063-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BJ, Garber J. Psychosocial antecedents of variation in girls' pubertal timing: Maternal depression, stepfather presence, and marital and family stress. Child Development. 2000;71(2):485–501. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BJ, McFadyen-Ketchum S, Dodge KA, Pettit GS, Bates JE. Quality of early family relationships and individual differences in the timing of pubertal maturation in girls: A longitudinal test of an evolutionary model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77(2):387–401. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.77.2.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BJ, Shirtcliff EA, Boyce WT, Deardorff J, Essex MJ. Quality of early family relationships and the timing and tempo of puberty: Effects depend on biological sensitivity to context. Development and Psychopathology. 2011;23(1):85–99. doi: 10.1017/s0954579410000660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espey LL. Ovulation as an inflammatory reaction - hypothesis. Biology of Reproduction. 1980;22(1):73–106. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod22.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Euling SY, Herman-Giddens ME, Lee PA, Selevan SG, Juul A, Sorensen TIA, et al. Swan SH. Examination of US puberty-timing data from 1940 to 1994 for secular trends: Panel findings. Pediatrics. 2008;121:S172–S191. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1813D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y, Hong XM, Wilker E, Li ZP, Zhang WB, Jin DL, et al. Xu X. Effects of age at menarche, reproductive years, and menopause on metabolic risk factors for cardiovascular diseases. Atherosclerosis. 2008;196(2):590–597. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman DS, Khan LK, Serdula MK, Dietz WH, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS. Relation of age at menarche to race, time period, and anthropometric dimensions: The Bogalusa Heart Study. Pediatrics. 2002;110(4) doi: 10.1542/peds.110.4.e43. doi:e43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frontini MG, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS. Longitudinal changes in risk variables underlying metabolic Syndrome X from childhood to young adulthood in female subjects with a history of early menarche: The Bogalusa Heart Study. International Journal of Obesity. 2003;27(11):1398–1404. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galobardes B, Lynch JW, Smith GD. Childhood socioeconomic circumstances and cause-specific mortality in adulthood: Systematic review and interpretation. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2004;26:7–21. doi: 10.1093/expirev/mxh008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galobardes B, Lynch JW, Smith GD. Is the association between childhood socioeconomic circumstances and cause-specific mortality established? Update of a systematic review. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2008;62(5):387–390. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.065508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galobardes B, Smith GD, Lynch JW. Systematic review of the influence of childhood socioeconomic circumstances on risk for cardiovascular disease in adulthood. Annals of Epidemiology. 2006;16(2):91–104. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2005.06.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee GC, Payne-Sturges DC. Environmental health disparities: A framework integrating psychosocial and environmental concepts. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2004;112(17):1645–1653. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geronimus A. The weathering hypothesis and the health of African-American women and infants: Evidence and speculations. Ethnicity and Disease. 1992;2(3):207–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geronimus A, Hicken M, Pearson J, Seashols S, Brown K, Cruz T. Do US Black Women Experience Stress-Related Accelerated Biological Aging? Human Nature-an Interdisciplinary Biosocial Perspective. 2010;21(1):19–38. doi: 10.1007/s12110-010-9078-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles WH, Kittner SJ, Hebel JR, Losonczy KG, Sherwin RW. Determinants of black-white differences in the risk of cerebral infarction - the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Epidemiologic Follow-up Study. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1995;155(12):1319–1324. doi: 10.1001/archinte.155.12.1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillum RF, Mussolino ME, Madans JH. Coronary heart disease incidence and survival in African-American women and men - The NHANES I epidemiologic follow-up study. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1997;127(2):111–&. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-2-199707150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goosby B, Cheadle J, McDade T. Birth weight, early life course BMI, and body size change: Chains of risk to adult inflammation? Social Science & Medicine. 2016;148:102–109. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.11.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goosby B, Heidbrink C. The transgenerational consequences of discrimination on African-American health outcomes. Sociology Compass. 2013;7:630–643. doi: 10.1111/soc4.12054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goosby B, Malone S, Richardson E, Cheadle J, Williams D. Perceived discrimination and markers of cardiovascular risk among low-income African American youth. American Journal of Human Biology. 2015;27(4):546–552. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.22683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graber JA, Brooksgunn J, Warren MP. The antecendents of menarcheal age - heredity, family environment, and stressful life events. Child Development. 1995;66(2):346–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy R, Kuh D, Whincup PH, Wadsworth MEJ. Age at puberty and adult blood pressure and body size in a British birth cohort study. Journal of Hypertension. 2006;24(1):59–66. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000198033.14848.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He CY, Zhang CL, Hunter DJ, Hankinson SE, Louis GMB, Hediger ML, Hu FB. Age at menarche and risk of type 2 diabetes: results from 2 large prospective cohort studies. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2010;171(3):334–344. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman Giddens ME, Slora EJ, Wasserman RC, Bourdony CJ, Bhapkar MV, Koch GG, Hasemeier CM. Secondary sexual characteristics and menses in young girls seen in office practice: A study from the pediatric research in office settings network. Pediatrics. 1997;99(4):505–512. doi: 10.1542/peds.99.4.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoier S. Father absence and age at menarche - A test of four evolutionary models. Human Nature-an Interdisciplinary Biosocial Perspective. 2003;14(3):209–233. doi: 10.1007/s12110-003-1004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature. 2006;444(7121):860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature05485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyt LT, Falconi AM. Puberty and perimenopause: Reproductive transitions and their implications for women's health. Social Science & Medicine. 2015;132:103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulanicka B, Lipowicz A, Koziel S, Kowalisko A. Relationship between early puberty and the risk of hypertension/overweight at age 50: Evidence for a modified Barker hypothesis among Polish youth. Economics & Human Biology. 2007;5(1):48–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen BK, Heuch I, Kvale G. Association of low age at menarche with increased all-cause mortality: A 37-year follow-up of 61,319 Norwegian women. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2007;166(12):1431–1437. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen BK, Oda K, Knutsen SF, Fraser GE. Age at menarche, total mortality and mortality from ischaemic heart disease and stroke: the Adventist Health Study, 1976-88. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2009;38(1):245–252. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janicki-Deverts D, Cohen S, Matthews KA, Jacobs DR. Sex differences in the association of childhood socioeconomic status with adult blood pressure change: The CARDIA Study. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2012;74(7):728–735. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31825e32e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen I, Katzmarzyk PT, Ross R. Body mass index, waist circumference, and health risk. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2002;162(18):2074–2079. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.18.2074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen I, Powell LH, Jasielec MS, Matthews KA, Hollenberg SM, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Everson-Rose SA. Progression of Coronary Artery Calcification in Black and White Women: Do the Stresses and Rewards of Multiple Roles Matter? Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2012;43(1):39–49. doi: 10.1007/s12160-011-9307-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasik CB, Lustig RH. Adolescent obesity and puberty: The “Perfect Storm”. In: Gordon CM, Welt C, Rebar RW, Hillard PJA, Matzuk MM, Nelson LM, editors. Menstrual Cycle and Adolescent Health. Vol. 1135. 2008. pp. 265–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jha AK, Varosy PD, Kanaya AM, Hunninghake DB, Hlatky MA, Waters DD, et al. Shlipak MG. Differences in medical care and disease outcomes among black and white women with heart disease. Circulation. 2003;108(9):1089–1094. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000085994.38132.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JL, Heineman EF, Heiss G, Hames CG, Tyroler HA. Cardiovascular disease risk factors and mortality among black women and white women aged 40-64 years in Evans County, Georgia. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1986;123(2):209–220. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolly S, Vittinghoff E, Chattopadhyay A, Bibbins-Domingo K. Higher Cardiovascular Disease Prevalence and Mortality among Younger Blacks Compared to Whites. American Journal of Medicine. 2010;123(9):811–818. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlamangla AS, Merkin SS, Crimmins EM, Seeman TE. Socioeconomic and Ethnic Disparities in Cardiovascular Risk In the United States, 2001-2006. Annals of Epidemiology. 2010;20(8):617–628. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley-Hedgepeth A, Lloyd-Jones DM, Colvin A, Matthews KA, Johnston J, Sowers MR, et al. Investigators S. Ethnic differences in C-reactive protein concentrations. Clinical Chemistry. 2008;54(6):1027–1037. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.098996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khera A, McGuire DK, Murphy SA, Stanek HG, Das SR, Vongpatanasin W, et al. de Lemos JA. Race and gender differences in C-reactive protein levels. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2005;46(3):464–469. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.04.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, Smith PK. Retrospective survey of parental marital relations and child reproductive development. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 1998;22(4):729–751. [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, Smith PK, Palermiti AL. Conflict in childhood and reproductive development. Evolution and Human Behavior. 1997;18(2):109–142. [Google Scholar]

- Kindblom JM, Lorentzon M, Norjavaara E, Lonn L, Brandberg J, Angelhed JE, et al. Ohlsson C. Pubertal timing is an independent predictor of central adiposity in young adult males - The Gothenburg Osteoporosis and Obesity Determinants study. Diabetes. 2006;55(11):3047–3052. doi: 10.2337/db06-0192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivimaki M, Lawlor DA, Smith GD, Elovainio M, Jokela M, Keltikangas-Jarvinen L, et al. Raitakari OT. Association of age at menarche with cardiovascular risk factors, vascular structure, and function in adulthood: the Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns study. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2008;87(6):1876–1882. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.6.1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koprowski C, Coates RJ, Bernstein L. Ability of young women to recall past body size and age at menarche. Obesity Research. 2001;9(8):478–485. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuh D, Ben-Shlomo Y, Lynch J, Hallqvist J, Power C. Life course epidemiology. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2003;57(10):778–783. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.10.778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laitinen J, Power C, Jarvelin MR. Family social class, maternal body mass index, childhood body mass index, and age at menarche as predictors of adult obesity. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2001;74(3):287–294. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/74.3.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakshman R, Forouhi N, Luben R, Bingham S, Khaw K, Wareham N, Ong KK. Association between age at menarche and risk of diabetes in adults: results from the EPIC-Norfolk cohort study. Diabetologia. 2008;51(5):781–786. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-0948-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakshman R, Forouhi NG, Sharp SJ, Luben R, Bingham SA, Khaw KT, et al. Ong KK. Early age at menarche is associated with cardiovascular disease and mortality. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2009;94(12):4953–4960. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapidus L, Bengtsson C, Larsson B, Pennert K, Rybo E, Sjostrom L. Distribution of adipose-tissue and risk of cardiovascular-disease and death - A 12 year follow up of participants in The Population Study of Women In Gothenburg, Sweden. British Medical Journal. 1984;289(6454):1257–1261. doi: 10.1136/bmj.289.6454.1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassek WD, Gaulin SJC. Brief communication: Menarche is related to fat distribution. American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 2007;133(4):1147–1151. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.20644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman BJ, Taylor SE, Kiefe CI, Seeman TE. Relation of childhood socioeconomic status and family environment to adult metabolic functioning in the CARDIA study. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2005 Nov-Dec;67(6):846–854. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000188443.48405.eb. 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman BJ, Taylor SE, Kiefe CI, Seeman TE. Relationship of early life stress and psychological functioning to blood pressure in the CARDIA Study. Health Psychology. 2009;28(3):338–346. doi: 10.1037/a0013785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis TT, Everson-Rose SA, Colvin A, Matthews K, Bromberger JT, Sutton-Tyrrell K. Interactive Effects of Race and Depressive Symptoms on Calcification in African American and White Women. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2009;71(2):163–170. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31819080e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libby P, Theroux P. Pathophysiology of coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2005;111(25):3481–3488. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.105.537878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llop-Vinolas D, Vizmanos B, Monasterolo RC, Subias JE, Fernandez-Ballart JD, Marti-Henneberg C. Onset of puberty at eight years of age in girls determines a specific tempo of puberty but does not affect adult height. Acta Paediatrica. 2004;93(7):874–879. doi: 10.1080/08035250410025979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Jones DM, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Patel AS, Matthews KA, Pasternak RC, Everson-Rose SA, et al. Chae CU. Ethnic variation in hypertension among premenopausal and perimenopausal women - Study of women's health across the nation. Hypertension. 2005;46(4):689–695. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000182659.03194.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch J, Smith GD. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology. Annual Review of Public Health. 2005;26:1–35. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macartney S, Bishaw A, Fontenot K. Poverty rates for selected detailed race and Hispanic groups by state and place. Washington DC: US Census Bureau; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Maestripieri D, Roney JR, DeBias N, Durante KM, Spaepen GM. Father absence, menarche and interest in infants among adolescent girls. Developmental Science. 2004;7(5):560–566. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2004.00380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manuck SB, Craig AE, Flory JD, Halder I, Ferrell RE. Reported early family environment covaries with menarcheal age as a function of polymorphic variation in estrogen receptor-alpha. Development and Psychopathology. 2011;23(1):69–83. doi: 10.1017/s0954579410000659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in pattern of pubertal changes in girls. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 1969;44(235):291–&. doi: 10.1136/adc.44.235.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey D. Getting away with murder - segregation and violent crime in urban America. University of Pennsylvania Law Review. 1995;143(5):1203–1232. doi: 10.2307/3312474. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Massey D. Segregation and Stratification: A Biosocial Perspective. Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race. 2004;1(1):7–25. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews KA, Sowers MF, Derby CA, Stein E, Miracle-McMahill H, Crawford SL, Pasternak RC. Ethnic differences in cardiovascular risk factor burden among middle-aged women: Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN) American Heart Journal. 2005;149(6):1066–1073. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDade TW, Reyes-Garcia V, Tanner S, Huanca T, Leonard WR. Maintenance versus growth: Investigating the costs of immune activation among children in lowland Bolivia. American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 2008;136(4):478–484. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.20831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mensah GA, Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Greenlund KJ, Croft JB. State of disparities in cardiovascular health in the United States. Circulation. 2005;111(10):1233–1241. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000158136.76824.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midei AJ, Matthews KA. Interpersonal violence in childhood as a risk factor for obesity: a systematic review of the literature and proposed pathways. Obesity Reviews. 2011;12(501):e159–e172. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00823.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midei AJ, Matthews KA, Chang YF, Bromberger JT. Childhood physical abuse is associated with incident metabolic syndrome in mid-life women. Health Psychology. 2013;32(2):121–127. doi: 10.1037/a0027891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller G, Chen E. Unfavorable socioeconomic conditions in early life presage expression of proinflammatory phenotype in adolescence. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2007;69(5):402–409. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318068fcf9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GE, Chen E. Harsh family climate in early life presages the emergence of a proinflammatory phenotype in adolescence. Psychological Science. 2010;21(6):848–856. doi: 10.1177/0956797610370161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Belsky J, Silva PA. Childhood experience and the onset of menarche - a test of a sociobiological model. Child Development. 1992;63(1):47–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb03594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Must A, Phillips SM, Naumova EN, Blum M, Harris S, Dawson-Hughes B, Rand WM. Recall of early menstrual history and menarcheal body size: After 30 years, how well do women remember? American Journal of Epidemiology. 2002;155(7):672–679. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.7.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazmi A, Victora CG. Socioeconomic and racial/ethnic differentials of C-reactive protein levels: a systematic review of population-based studies. Bmc Public Health. 2007;7 doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-212. doi:21210.1186/1471-2458-7-212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negriff S, Blankson AN, Trickett PK. Pubertal Timing and Tempo: Associations With Childhood Maltreatment. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2015;25(2):201–213. doi: 10.1111/jora.12128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesbitt SD. Hypertension in black patients: special issues and considerations. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2004;6(6):416–420. doi: 10.1007/s11886-004-0048-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden CL, Yanovski SZ, Carroll MD, Flegal KM. The epidemiology of obesity. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(6):2087–2102. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohira T, Roux AVD, Polak JF, Homma S, Iso H, Wasserman BA. Associations of Anger, Anxiety, and Depressive Symptoms With Carotid Arterial Wall Thickness: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2012;74(5):517–525. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31824f6267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantsiotou S, Papadimitriou A, Douros K, Priftis K, Nicolaidou P, Fretzayas A. Maturational tempo differences in relation to the timing of the onset of puberty in girls. Acta Paediatrica. 2008;97(2):217–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen AC, Crockett L, Richards M, Boxer A. A self-report measure of pubertal status--reliability, validity, and initial norms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1988;17(2):117–133. doi: 10.1007/bf01537962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce MB, Kuh D, Hardy R. Role of lifetime body mass index in the association between age at puberty and adult lipids: findings from men and women in a british birth cohort. Annals of Epidemiology. 2010;20(9):676–682. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plant TM, Barker-Gibb ML. Neurobiological mechanisms of puberty in higher primates. Human Reproduction Update. 2004;10(1):67–77. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmh001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan AD, Manson JE, Rifai N, Buring JE, Ridker PM. C-reactive protein, interleukin 6, and risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus. Jama-Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;286(3):327–334. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.3.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan AD, Ridker PM. Do atherosclerosis and type 2 diabetes share a common inflammatory basis? European Heart Journal. 2002;23(11):831–834. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2001.3052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]