Abstract

Histopathological examination is considered as gold standard procedure for arriving at a final diagnosis of various lesions of the human body. However, it is limited by a number of alterations of normal morphologic and cytological features that occur as a result of presence of artifacts. These artifacts may occur during surgical removal, fixation, tissue processing, embedding and microtomy and staining and mounting procedures. They can even lead to complete uselessness of the tissue. It is therefore essential to identify the commonly occurring artifacts during histopathological interpretations of tissue sections. This article reviews the common artifacts encountered during slide examination alongside the remedial measures which can be undertaken to differentiate between an artifact and tissue constituent.

Keywords: Artifact, diagnosis, histopathology, microtome, tissue specimen

INTRODUCTION

The accurate diagnosis of various lesions under microscope requires preparation of tissue sections, usually stained, that represents as closely as possible their structures in life. The preparation of high-quality sections requires skill and experience in the field of laboratory discipline. Most often, pathologists encounter slides that are either improperly fixed or mishandled during tissue processing, resulting in alterations in tissue details. Such changes are classified as “artifacts.” Artifact refers to “An artificial structure or tissue alteration on a prepared microscopic slide as a result of an extraneous factor.”[1] They are the major source of diagnostic problem. The aim of this article is to review the various causes of artifacts and how to identify and prevent them from interfering in the accurate diagnosis of lesions.

Classification of artifacts:[2]

Prefixation artifacts

Fixation artifacts

Artifacts related to bone tissue

Tissue-processing artifacts

Artifacts related to microtomy

Artifacts related to floatation and mounting

Staining artifacts

Mounting artifacts.

Prefixation artifacts

Injection artifact

Intralesional injection of anesthetic solution should be avoided as it can cause bleeding with extravasation and separation of connective tissue bands, with vacuolization [Figures 1 and 2].[3,4] For example, bulla formation in gingival tissue or edema which may lead to confusion in the diagnosis of Crohn's disease or orofacial granulomatosis.[5]

Figure 1.

Histopathological image shows separation of connective tissue bands due to intralesional injection of anesthetic solution (H&E stain, ×10)

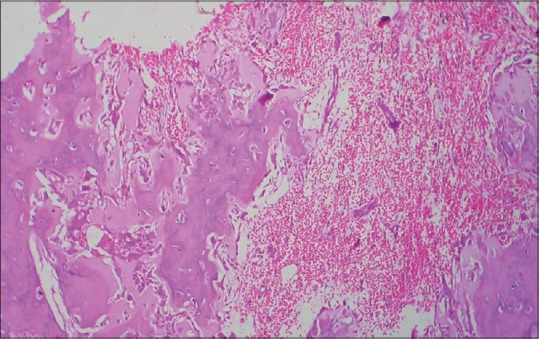

Figure 2.

Histopathological image shows hemorrhage occurring during surgery which may be misinterpreted as pathological change (H&E, ×10)

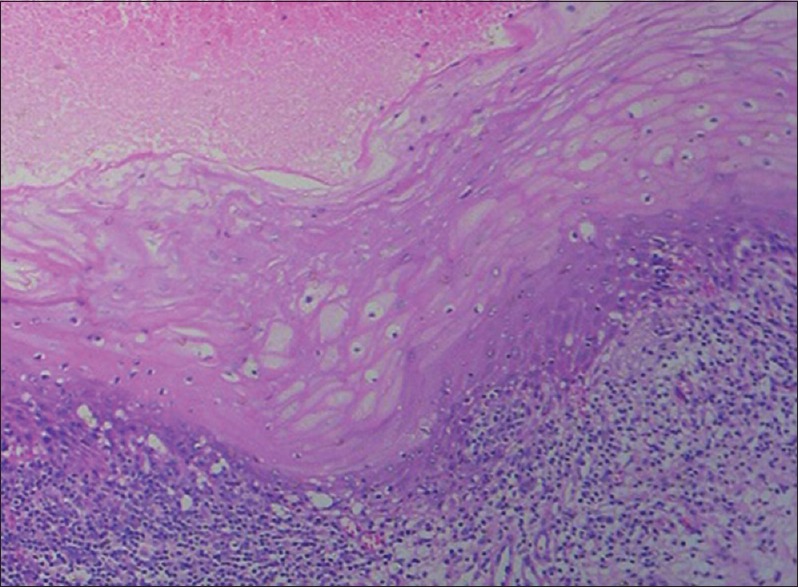

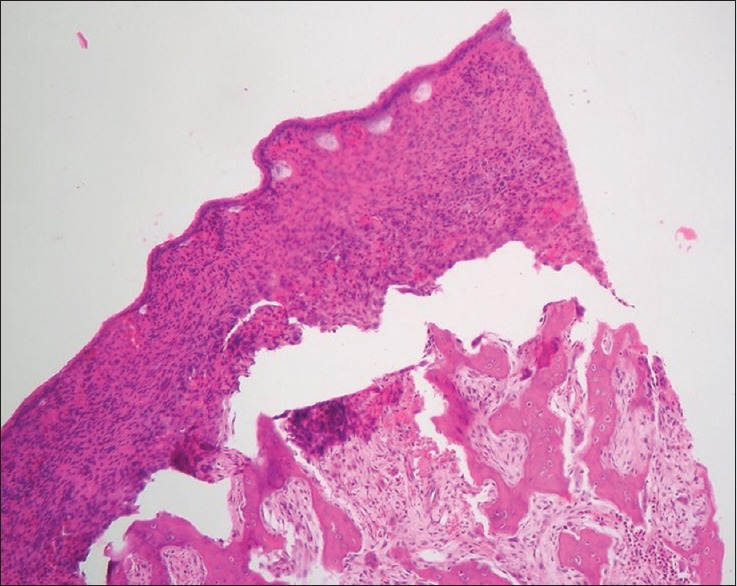

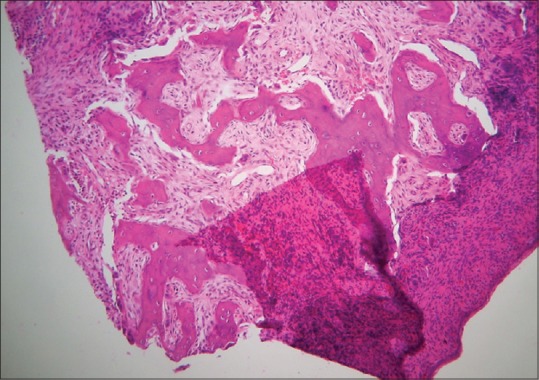

Squeeze artifact

This is the form of tissue distortion resulting from even the most minimal compression of tissue by forceps or other surgical instrument. It includes crush, hemorrhage, splits, fragmentation and pseudo-cysts [Figures 3 and 4].[3,4] Microscopically, in crush artifacts, the cellular details are not recognizable and nuclei appear darkly stained and distorted [Figure 5]. This can be avoided by placing a suture within the mucosa that is to be removed and holding its ends by an artery forcep.[5]

Figure 3.

Histopathological image shows tissue tear due to rough handling by forcep (H&E, ×10)

Figure 4.

Histopathological image shows tissue tear and folds due to rough handling by forcep (H&E, ×10)

Figure 5.

Histopathological image shows crush artifact (H&E, ×10)

Fulguration artifact

It occurs during electrosurgical or laser cutting of tissue resulting in a zone of thermal necrosis and tissue distortion. The epithelium and connective tissue show an amorphous appearance due to coagulation of proteins. The epithelial cells appear detached from connective tissue and the nuclei assume a spindled, palisading configuration. This can be prevented by using the cutting and not the coagulation electrodes when obtaining the specimen.[2]

Starch artifact

Starch powder, a lubricant of surgical gloves, is a common contaminant of cytological and histological specimens. In hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections, they appear as numerous blue, small, spherical structures. In oral cytosmear, they appear as refractile, glassy, polygonal bodies 5–20 μm in diameter, with a central dot or Y-shaped structure that may be misinterpreted as a pyknotic nucleus or for cell undergoing mitosis. These might also resemble epithelial cells. They are Periodic acid–Schiff (PAS)-positive and under polarized light microscopy exhibit “Maltese cross” birefringence pattern.[6] Other foreign bodies such as fragment of suture material can occasionally be found in histological sections [Figure 6].

Figure 6.

Histopathological image shows sutural artifact (H&E, ×10)

Autolysis artifact

Ideally, tissues should be fixed immediately and completely from the living state to prevent loss of enzymes, mitochondrial damage, RNA and protein degradation and decrease in mitosis because of the ensuing anoxia. Autolyzed tissue shows increased eosinophilia due to loss of normal basophilia imparted by RNA in the cytoplasm and increased binding of eosin to denatured intracytoplasmic proteins and vacuolization of cytoplasm. Nuclear changes include pyknosis, karyolysis and karryohexis [Figure 7].[7]

Figure 7.

Histopathological image shows tissue autolysis due to delayed fixation (H&E, ×10)

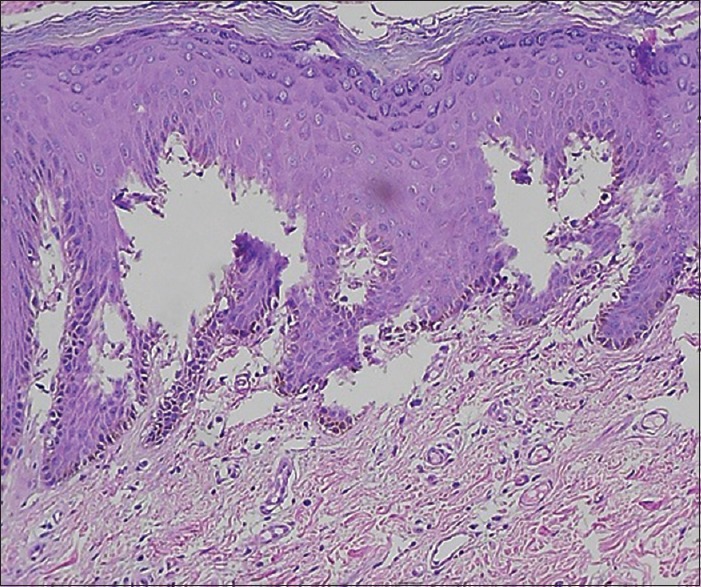

Improper prefixation

Solutions such as normal saline do not fix the tissue and tissue will undergo autolysis. Microscopically, such a section will show features of autolysis artifact as well as separation of epithelium from the connective tissue (simulate vesiculobullous lesions such as pemphigus) [Figure 8].[8]

Figure 8.

Histopathological image shows separation of epithelium from the connective tissue simulating vesiculobullous lesion (H&E, ×10)

Fixation artifacts

Formalin pigments

Formaldehyde has a natural tendency to be oxidized, producing formic acid. Heme from red blood cells and formalin bind each other to form formalin–heme complex that appears as brown-black amorphous to microcrystalline granules in tissue sections. The pigment is a derivative of hematin and exhibits many physical and histochemical properties similar to pigments produced by some animal parasites as in malaria, schistosoma and pulmonary mites. They are removed from tissue sections by immersion in saturated alcoholic picric acid. The use of buffered neutral formalin will minimize this problem.[9]

Mercury pigments

Mercuric chloride containing fixative usually, but not invariably, produces dark brown granular deposits. Mercuric chloride pigment is extracellular and can be removed by treatment in alcoholic iodine.[9]

Osmolality of the fixative solution

Hypertonic fixative solutions cause cellular shrinkage and increased extracellular spaces, whereas isotonic (300–320 mOsm) and hypotonic fixatives could result in cell swelling. Best results were obtained using slightly hypertonic solution (400–450 mOsm).[10]

Ice-crystal artifact

It results from slow freezing of tissue, inappropriate quenching techniques or the selection of tissue samples too large to permit rapid freezing. It appears as intercellular clefts in highly cellular tissue and intracellular clefts and vacuoles in skeletal muscle.[11] Carbon dioxide expansion freezers are quite satisfactory for the prevention of gross ice crystals in fresh tissue, including materials for rapid diagnosis prior to cryostat microtomy.

Freezing artifact

Appear as Swiss cheese holes in epithelium (Interstitial vacuoles along with vacuoles inside the cell cytoplasm) and tissue spaces. They represent the areas where ice crystals rupture the tissue. This mechanism primarily consists of osmotic damage derived from ice formation in the fixative solution in which the biopsies are customarily dispensed.[3]

Streaming artifact

This is due to diffusion of unfixed material to give false localization by coming to rest in a place other than its original location, for example, false localization with glycogen and enzymes in histochemistry. It is most often seen in formalin-fixed tissue. It can be avoided by using glycogen fixatives (formol-alcohol or Bouin) or by freeze drying.[10]

Microwave fixation artifact

Optimum temperature for microwave fixation is 45° C–55°C. Underheating results in poor sectioning quality, whereas overheating produces vacuolation, overstained cytoplasm and pyknotic nuclei.[10]

Artifacts related to bone tissue

Bone dust artifacts

Undecalcified resin sections of bone when cut, dust is produced. Some of these fragments are deposited on the cut surfaces while others may be implanted more deeply in the specimen. In hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections, it stains strongly with hematoxylin. When deposited in bone marrow, it stains black with von kossa, indicating its origin from calcified trabecular matrix. In undecalcified sections, this could lead to an erroneous diagnosis of metastatic calcification. Its extent may be reduced by ensuring that saw blades and drills are sharp and by the trimming of blocks to final size with a knife or razor blade after decalcification rather than with a saw initially. It is sometimes recommended to gently brush the surface of blocks with a soft brush after sawing to remove debris.[12]

Decalcification

Acid-decalcifying fluids have hydrolytic actions that can cause digestion of cellular and other tissue components more rapidly when the tissue is unfixed or partially fixed. Impairment or loss of tissue basophilia, inactivation of enzymes, loss of iron and ribonucleic acid and destruction of tooth enamel can occur. This can be reduced by thorough fixation of specimen before decalcification.[13]

Overdecalcification

Overdecalcified sections stain strongly with eosin and show a marked loss of nuclear basophilia. Nuclear and cytoplasmic detail is poorly preserved. The damaging effect of acid-decalcifying fluid may be reduced by thorough fixation of specimen before decalcification and by the radiographic check of the progress and completion of decalcification.[12]

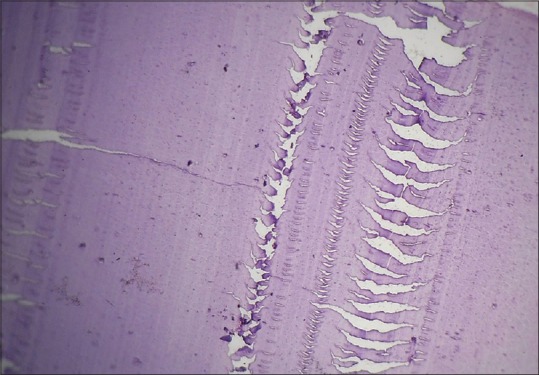

Effect of incomplete decalcification

This can result in damage to the microtome knife and to the soft tissue surrounding the calcified area when trimming the paraffin block. Bony trabeculae stain strongly with hematoxylin (indicating residual calcium) and the adjacent soft tissue is severely disrupted [Figure 9].[12]

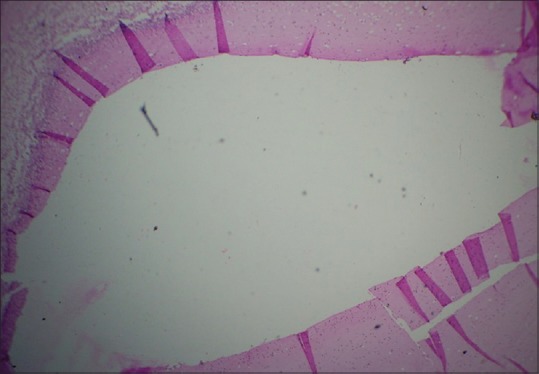

Figure 9.

Histopathological image shows bone trabeculae stained strongly with hematoxylin due to incomplete decalcification (H&E, ×10)

Tissue-processing artifacts

Improper dehydration

Too long treatment in higher concentration of alcohol results in high degree of shrinkage of the tissue referred as shrinkage artifacts.[3] Too long treatment in lower dilution of alcohol macerates the tissue seen as vacuolization. These two procedures will also make the tissue brittle and interfere with staining properties.[14] When tissue is not completely dehydrated, the paraffin will not infiltrate properly and the block is difficult to cut resulting in tearing artifacts and holes. When this occurs, rehydrate the tissue section and repeat the processing.[15] Dehydration should be always gradual starting from 50%.[16]

Improper clearing

Prolonged treatment in xylene will make the tissue brittle, leading to crumbling and crystallization during cutting. Conversely, if specimen is not cleared properly in xylene, the paraffin will not impregnate properly and will lead to distortion of tissue during sectioning.[16]

Improper embedding

Exposing the specimen too long during embedding procedure causes excessive hardening so that it becomes friable and sectioning will give rise to cracks.[14]

Orientation artifact

Improper orientation will lead to disorderly arranged histological features in slide. For orientation of skin, it must be positioned so that the epithelial edges, the subcutaneous tissue and deeper layers all flat to the bottom so that all strata will be seen in the finished slide. When embedding more than one specimen, all the pieces of tissue should be embedded firmly to the bottom of the container so that the cut section will present a valid presentation of the tissue submitted.[2]

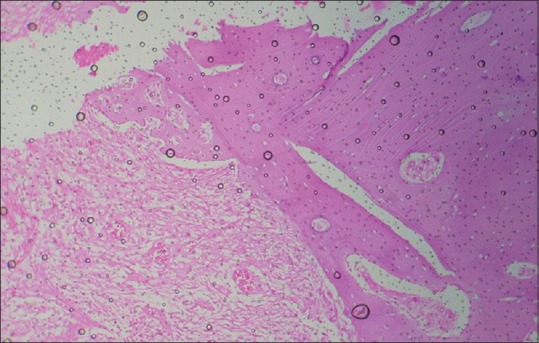

Loss of soluble substances

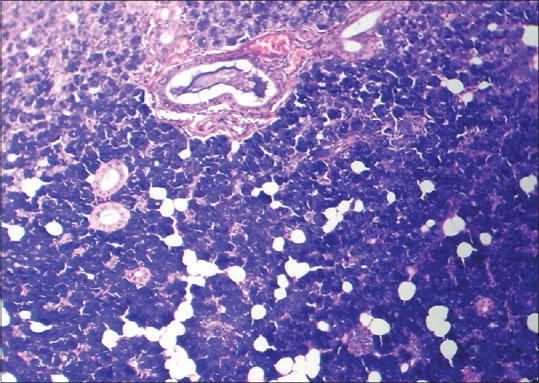

The preparation of paraffin wax, cellulose nitrate and most synthetic resin embedded sections entails the use of fat solvents. Thus, the fat will dissolve from fat cells during processing of adipose tissue and will appear as ovoid spaces surrounded by a rim of cytoplasm, for example, lipoma and cholesterol clefts in odontogenic cysts [Figure 10].[2]

Figure 10.

Histopathological image shows cholesterol clefts in odontogenic cysts (H&E, ×10)

Artifacts related to microtomy

Scores and tearing in sections

These are caused either by a nick or blemish in the knife edge and when sectioning hard particles such as foci of calcification, debris within the block. In the former instance, the tear usually extends across the whole section [Figure 11]. It is avoided using different part of knife or resharpenening it. In the latter, it may start from that point. It is avoided by removing the hard particle with fine sharp-pointed scalpel or by re-embedding in fresh filtered wax or by surface decalcification before cutting.[17]

Figure 11.

Histopathological image shows scoring and tearing of section due to nick in knife edge (H&E, ×10)

Chatters

Chatters refer to thick and thin zones parallel to the knife edge.

Chatter/Venetian blind artifact: Chatters refer to thick and thin zones parallel to the knife edge [Figure 12].[18]

Figure 12.

Histopathological image shows venetian blind artifact due to vibration of knife edge (H&E, ×10)

These are caused by:

Tiny vibrations in the knife edge: Ensure that the knife is securely clamped into its holder and the holder to the microtome

Excessive hardness and brittleness of the block: Cutting thinner sections or softening the blocks (softening fluid or surface decalcification), using sharp heavy duty knife or heavy duty microtome

Excessive steep knife angle: Reduce clearance angle to minimum, but still leaving clearance (3°C–8°C).

Compression artifact

It is caused by:[17]

Blunt knife: Displacement of tissue components, especially bone is a common finding [Figure 13]. Sharpen the knife

Bevel of the knife too wide: Resharpen to produce secondary bevels or have regrounded

Wax too soft for tissue or sectioning condition: Cool block with ice or use higher melting point wax.

Figure 13.

Histopathological image shows displacement of bone during microtomy in association with the use of dull knife (H&E, ×10)

Moth-eaten effect (holes from roughing)

It occurs due to excessively rough trimming of the paraffin blocks with greater thickness. This pulls out the tissue fragments from the block face and these appear as void spaces or holes in subsequent thin sections with their long axis parallel to the knife edge. To avoid these artifacts, the knife should be sharpened regularly and the rough cutting carried out at a lower thickness setting.[17] If the tissue is cut tangentially, the connective tissue cores may become entrapped within the epithelium, giving a false impression of invasive squamous cell carcinoma [Figure 14].[2]

Figure 14.

Histopathological image shows tangential cut artifact (H&E, ×10)

Floater artifact

Floaters are pieces of tissue that appear on slides that do not belong there. They may have floated during processing and may result from sloppy procedures on cutting bench using dirty towel, knife, gloves and improper cleaning of water bath. These can have tissues that are carried over to the next case.[16]

Alternate thick and thin sections

Alternate thick and thin sections are produced when the wax is too soft for tissue, block or blade is loose, clearance angle is insufficient or mechanism of microtome is faulty. Remedy is to cool the block with ice, tighten the blade and increase the clearance angle.[17] Also, wrinkling and curling in tissue can occur at this stage [Figure 15].

Figure 15.

Histopathological image shows curling artifact due to folding of tissue due to blunt microtome knife (H&E, ×10)

Artifacts related to floatation and mounting

Prolonged floating of sections on the water bath

Tissue may expand beyond their original size and become distorted and give epithelium an acantholytic appearance mimicking edema.[10]

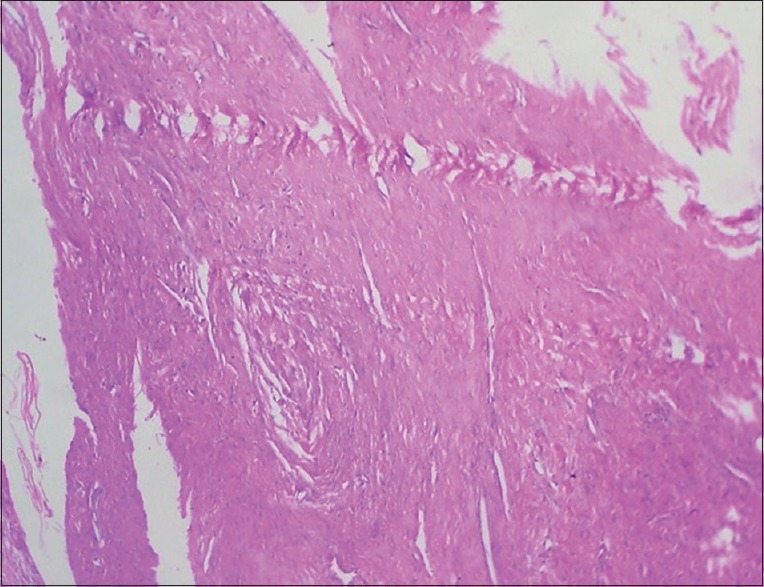

Folds and wrinkles in section

Wrinkles and folding of tissue sections occur when very thin paraffin sections are forced to stretch unevenly around other structures which have different consistencies. These artifacts appear as darker-stained strands [Figure 16]. Any remaining wrinkles and fords in section on water bath can be removed by stretching and gental tapping with forcep. During these procedures, overstretching may cause tear in the tissue section leading to acantholytic appearance in epithelium.[10,16]

Figure 16.

Histopathological image shows wrinkles and folds due to uneven stretching of tissue sections (H&E, ×10)

Contamination

The water bath may sometimes get contaminated with dust, hair, residual cells of previous section, etc., Contamination with squamous epithelial cells and keratinous debris has been shown to be caused by fingers to remove air bubbles or sneezes or cough.[19] Frequent cleaning of the surface of the water is recommended and this is best carried out by floating a sheet of thin paper across the surface of the water. To reduce the incidence of artifacts, distilled water rather than tap water should be used. False-positive Prussian blue reactions have been traced to iron in the tap water for floating sections.[10]

Air bubbles

As the tissue sections are flattened in the water bath, bubbles of air may become trapped beneath them. Collapsed bubble artifact occurs due to collapsing of air bubbles entrapped beneath the sections leaving cracked areas when dry, which fail to adhere to the glass slide properly and show altered staining. This can be prevented by using freshly boiled water in floatation bath.[20]

Staining artifacts

Residual wax

Failure to remove the wax from parts of a section before staining will result in incomplete or partial staining in that area. This can result in the Pink disease artifact. This artifact was studied in detail by Nedzel et al. in 1951. This author described the presence of intranuclear birefringent (paraffin wax) inclusions, particularly in the lymphocytes.[21]

Artifact related to addition of acetic acid to eosin

The effect of acetic acid is to increase ionization of tissue amino groups which results in more dye attaching, so addition of acetic acid can sometimes improve eosin staining by increasing the depth of coloration. If excess amount of acetic acid is added, it causes undifferentiated completely homogenous and flat deep pink-stained mass.[10]

Artifact due to mordent of hematoxylin

Aluminum potassium sulfate is used as a mordent in many hematoxylin. If the hematoxylin solution is not mixed properly during staining, conversion of aluminum potassium sulfate to crystalline form occurs resulting in deterioration of solution and a black pigment will appear throughout the section. This pigment is identified as hematin which precipitates due to the absence of mordent.[15]

Artifact due to fluorescent sheen of hematoxylin

Active alum hematoxylin solution sometimes develops a fluorescent sheen on the surface of the solution. If this fluorescent sheen is not removed properly, sheets or clumps of dye particle will be seen in finished slide [Figure 17].[15]

Figure 17.

Histopathological image shows stain deposit due to formation of fluorescent sheen in hematoxylin solution (H&E, ×10)

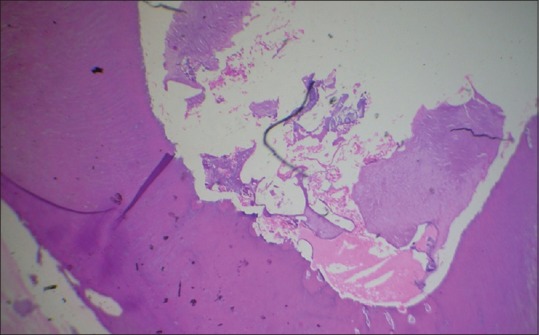

Mounting artifacts:

Residual water and air bubbles

Air bubbles are formed under the cover-slip when the mounting medium is too thin and as it dries, more air gets sucked under the edges [Figure 18]. This can be prevented by using mounting medium of adequate thickness and removal of air bubbles from under the slide.[2]

Figure 18.

Histopathological image shows air bubbles formed during mounting procedure (H&E, ×10)

Dry mounting artifact

The slides should not be allowed to dry during the application of coverslip. An artifact with the following three distinct features can be produced:

Section may exhibit brown stippling which resembles pigment

Highly refractile lines outlining cells and tissue

Trapped air may be seen in the nuclei leading to dark nuclei lacking details (corn-flake artifact).

This artifact can be corrected by removing coverslip in xylene and placing in xylene for few minute and then remounting before drying the slide.[22]

Artifact related to excessive use of mounting media

Excessive use of mounting media or the mounting media will result in foggy appearance. This artifact can be prevented by using adequate amount of mounting media with proper consistency.[10]

CONCLUSION

Tissue artifacts can be introduced into tissue specimen during any one of the many steps through which a specimen is carried before its microscope features are examined by the pathologist. Hence, proper handling of tissue along with prompt fixation and careful tissue processing will minimize the artifacts. The first article regarding artifacts was published by Zegarelli in 1978. Since then, very few articles appeared on this subject.[23] Through this review article, I have illustrated some of the important artifacts that prevent proper diagnosis as well as suggested some techniques of minimizing these problems.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Seoane J, Varela-Centelles PI, Ramírez JR, Cameselle-Teijeiro J, Romero MA. Artefacts in oral incisional biopsies in general dental practice: A pathology audit. Oral Dis. 2004;10:113–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1354-523x.2003.00983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rastogi V, Puri N, Arora S, Kaur G, Yadav L, Sharma R, et al. Artefacts: A diagnostic dilemma – A review. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:2408–13. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2013/6170.3541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Margarone JE, Natiella JR, Vaughan CD. Artifacts in oral biopsy specimens. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1985;43:163–72. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(85)90154-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ficarra G, McClintock B, Hansen LS. Artefacts created during oral biopsy procedures. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1987;15:34–7. doi: 10.1016/s1010-5182(87)80012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oliver RJ, Sloan P, Pemberton MN. Oral biopsies: Methods and applications. Br Dent J. 2004;196:329–33. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4811075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lovas GL, Howell RE, Peters E, Gardner DG. Starch artifacts in oral cytologic specimens. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1985;60:195–6. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(85)90292-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Srinivasan M, Sedmak D, Jewell S. Effect of fixatives and tissue processing on the content and integrity of nucleic acids. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:1961–71. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64472-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abbey LM, Sweeney WT. Fixation artifacts in oral biopsy specimens. Va Dent J. 1972;49:31–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pizzolato P. Formalin pigment (acid hematin) and related pigments. Am J Med Technol. 1976;42:436–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bancroft JD, Gamble M. Theory and Practice of Histological Technique. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone, Elsevier Health Sciences; 2008. pp. 53–105. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okun MR, Ellerin P, Piotrowicz MA. Prevention of ice crystal damage to biopsy specimens in transport. Arch Dermatol. 1972;105:458–9. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1972.01620060088022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carleton HM, Drury RA, Wallington EA. Carleton's Text Book of Histological Techniques. 5th ed. Vol. 41. The University of Michigan: Oxford University Press; 1967. p. 269. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cook SF, Ezra Cohn HE. A comparison of methods of decalcifying bone. J Histochem Cytochem. 1962;10:560–3. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krishnanand PS, Kamath VV, Nagaraja A, Badni M. Artefacts in oral mucosal biopsies: A review. J Orofac Sci. 2010;2:57–62. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chatterjee S. Artefacts in histopathology. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2014;18:S111–6. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.141346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Culling CF, Allison RT, Barr WT. Cellular Pathology Technique. 4th ed. Vol. 78. London, Boston: Butterworths; 1985. p. 18. 78, 611. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Culing CF, Allison RT, Barr WT, Culling CA. Cellular Pathology Techniques. 4th ed. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 1985. In microtome and microtomy. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bindhu P, Krishnapillai R, Thomas P, Jayanthi P. Facts in artifacts. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2013;17:397–401. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.125206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Woods AE, Ellis RC, editors. Laboratory Histopathology: A Complete Reference. Edinburg: Churchill Livingstone; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Niemann TH, Tranovich JG, De Young BR. Biopsy bag artifact. Am J Clin Pathol. 1998;110:224–6. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/110.2.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Faoláin EO, Hunter MB, Byrne JM, Kelehan P, Lambkin HA, Byrne HJ, et al. Raman spectroscopic evaluation of efficacy of current paraffin wax section dewaxing agents. J Histochem Cytochem. 2005;53:121–9. doi: 10.1177/002215540505300114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rolls GO, Farmer NJ, Hall JB. Artefacts in Histological and Cytological Preparations. 1st ed. Melbourne (Australia): Leica Biosystems Pty Ltd; 2012. p. 106. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zegarelli DJ. Common problems in biopsy procedure. J Oral Surg. 1978;36:644–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]