Abstract

Objectives

Children with acute bloody diarrhea are at risk of being infected with Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli (STEC) and of progression to hemolytic uremic syndrome. Our objective was to identify clinical and laboratory factors associated with STEC infection in children who present with acute bloody diarrhea.

Methods

We performed a prospective cohort study of consecutive children younger than 18 years who presented with acute (<2-week duration) bloody diarrhea between August 1, 2013, and August 1, 2014. We excluded patients with a chronic gastrointestinal illness and/or an obvious noninfectious source of bloody stool. We obtained a standardized history and study laboratory tests, performed physical examinations, and recorded patient outcomes.

Results

Of the 135 eligible patients, 108 were enrolled; 27 declined consent. The median patient age was 3 years, and 56% were male. Ten (9%) patients tested positive for STEC (E coli O157:H7, n = 8; E coli O111, n = 1; E coli O103, n = 1), and 62 had negative stool culture results. Children infected with STEC were older (8.5 vs 3 years, respectively) (P < .001) and more likely to have abdominal tenderness (83% vs 17%, respectively) than those in the other groups. D-Dimer concentrations had a 70% sensitivity and 55% specificity for differentiating children with STEC from those with another cause of bloody diarrhea and 75% sensitivity and 70% specificity in differentiating children with a bacterial etiology from those with negative stool culture results.

Conclusion

Clinical assessment and laboratory data cannot reliably exclude the possibility that children with bloody diarrhea have an STEC infection and are at consequent risk of developing hemolytic uremic syndrome. Abnormal D-dimer concentrations (>0.5 μg/mL) were insufficiently sensitive and specific for distinguishing patients with STEC from those with another bacterial cause of bloody diarrhea. However, this marker might be useful in identifying children whose bloody diarrhea is caused by a bacterial enteric pathogen.

Keywords: D-dimer, hemolytic uremic syndrome, infectious colitis

Basic laboratory results and clinical presentation do not differentiate children with Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli infection from those with another cause of bloody diarrhea. D-Dimer concentrations are elevated in those with a bacterial cause of bloody diarrhea.

Children with acute bloody diarrhea are at risk of having a Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli (STEC) infection and, by extension, hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) [1–3]. Depending on the region and the season, up to 15% of children who present to an emergency facility with acute bloody diarrhea are infected with STEC, and 15% to 20% of these children will develop HUS in the 2 weeks after the onset of diarrhea [3–6]. Most children with stringently defined (urinalysis-independent) HUS experience anuria, and the risk of chronic sequelae is related directly to the occurrence and duration of anuria [7–20]. In many centers, children with bloody diarrhea or proven STEC infection are not admitted until HUS develops [21], so the opportunity to mitigate disease progression is missed [22, 23].

Vigorous volume expansion early in the course of the illness and lesser degrees of hemoconcentration when HUS is diagnosed are associated with improved outcomes, especially avoidance of anuria and death [22–27]. Given this evidence, an approach to management is to hospitalize all patients with acute bloody diarrhea for intravenous volume expansion pending stool culture results [23]. However, such an “admit-all” approach would overhospitalize children who are at no risk of renal injury because they are infected with a pathogen that does not cause HUS. Risk stratification of children who present with acute bloody diarrhea could lead to more cost-effective practices by assessing the likelihood of a patient having an STEC infection and, by extension, the risk of developing HUS. However, most analyses of children with acute bloody diarrhea in emergency settings are nested within larger studies of children with any cause of diarrhea [28].

D-Dimer concentrations have been found to be abnormal in children with STEC infection compared with those in healthy controls, which prompts us to consider their use as a screening test with which to identify those with a STEC infection. D-Dimers, which are formed as intravascular fibrin clots undergo degradation, reflect intravascular thrombin accretion; small-vessel thrombi are hallmarks of HUS, and their levels are also elevated before the onset of profound vascular injury. However, it is unknown if circulating D-dimer concentrations are elevated in people with another infectious cause of bloody diarrhea.

Here, we report the results of a pilot prospective cohort study designed to identify clinical and laboratory risk factors in children who present with acute bloody diarrhea and to test the specific hypothesis that plasma D-dimer concentrations, which are known to be abnormal in people with a STEC infection [5], can predict STEC infection and, therefore, risk for HUS.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This prospective cohort study included consecutive children younger than 18 years with bloody diarrhea who presented to the emergency department (ED) or were admitted directly to the gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition inpatient service at St. Louis Children’s Hospital between August 1, 2013, and August 1, 2014. We excluded patients whose bloody diarrhea was of greater than 2 weeks’ duration or who were known to have a chronic gastrointestinal illness (eg, inflammatory bowel disease), who had an obvious noninfectious source of bloody stool (eg, hemorrhoid or fissure), who were wards of the state, and/or whose families had English language barriers. Research assistants or trained staff enrolled patients in the ED or on the inpatient ward 24 hours/day. Missed eligible patients were identified by chart review using International Statistical Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes. The study was approved by the Washington University institutional review board. Informed consent was obtained from each patient’s parents or guardians, and assent was obtained from patients aged 7 years or older.

Interventions

A standardized history and physical examination form that detailed each patient’s course of illness was completed by trained staff. D-Dimer concentrations were measured up to 2 times, at enrollment and during the next clinically indicated blood draw. Supernatants of plasma anticoagulated with citrate were frozen at −80°C. D-Dimer testing was performed using a latex-enhanced microparticle turbidimetric assay on an STA-Compact system (Diagnostica Stago, Asnieres sur Seine, France) and are reported in fibrinogen equivalent units (FEU) (upper limit of normal, 0.5 μg/mL). Results of the participants’ stool cultures and daily laboratory tests and clinical outcomes were obtained from the electronic medical records. Per St. Louis Children’s Hospital protocol, all patients with acute bloody diarrhea are admitted for intravenous volume expansion and daily blood tests (to obtain hemoglobin, electrolyte, and creatinine concentrations) until STEC infection has been excluded or, if a patient is infected with STEC, until hematologic stabilization is achieved [1]. Stool cultures in our institution are routinely plated on receipt in the laboratory, at all hours and on all days, on blood agar containing ampicillin, Hektoen enteric agar, MacConkey agar, sorbitol-MacConkey agar (SMAC) agar, Campylobacter blood agar, Yersinia selective agar, and Gram-negative (GN) broth to recover enteric pathogens (all media are from Remel, Lenexa, Kansas). Sorbitol-nonfermenting colonies are sought on the SMAC agar and, when present, are tested with an E coli O157 latex agglutination test and autoagglutination control (Remel) to identify E coli O157. The Premier enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay is performed on overnight GN broth culture to identify the presence of Shiga toxins 1 and 2 (Meridian Bioscience, Inc, Cincinnati, Ohio). All E coli O157 isolates and positive GN broths (if enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay results were positive and SMAC agar culture results were negative), are forwarded to the Missouri State Public Health Laboratory (Jefferson City, Missouri) for STEC isolation and characterization, including serotyping. All clinical decisions that involve study participants were made at the discretion of each patient’s physician/provider(s) independent of study participation.

Definitions

Bloody diarrhea was defined as at least 1 grossly bloody loose stool in the 24 hours before presentation. HUS was defined as a hematocrit level of <30%, a platelet count of <150 × 109/µL, and a creatinine concentration above the upper limit of normal for age [29]. The first day of illness was considered to be the first day of diarrhea.

Statistical Analysis

We report continuous data as medians with the interquartile range (IQR) and categorical data as proportions with the 95% confidence interval (CI). Categorical variable comparisons for the STEC and non-STEC groups and for the culture-positive and culture-negative groups are presented as differences in proportions with the 95% CI. The significance of differences between medians for continuous variables among groups was determined by the 2-tailed Mann-Whitney U test. We used SPSS for Windows 22 (IBM, Armonk, New York) for all analyses.

Sample Size

On the basis of previous ED and microbiological data, we estimated that we typically treat ~100 patients with bloody diarrhea per year, mostly during summer months. We also estimated that of these 100 patients, 10 to 15 would have an STEC infection and 3 would develop HUS.

Outcomes

Our primary outcome was stool culture results that were positive for STEC.

RESULTS

Of 135 eligible children, 7 refused consent, and 20 were missed, most of whom were hospitalized for <24 hours and were infected with Shigella sonnei as a result of a local community outbreak. No missed patient was infected with STEC or developed HUS. The median age of the 108 enrollees was 3 years (IQR, 1–7 years), and 56% were male. The median durations of illness and of bloody diarrhea before presentation were 3 days (IQR, 2–5 days) and 1 day (IQR, 1–1 day), respectively. Ten (9%) patients tested positive for STEC (E coli O157:H7, n = 8; E coli O111, n = 1; E coli O103, n = 1), and 2 developed HUS, both of whom were infected with E coli O157:H7; neither of these patients required dialysis. The median interval between admission to the ED or the inpatient service and the receipt of a specimen for culture in the laboratory was 2.3 hours (IQR, 1.5–3.2 hours). The median time to resumptive positive report after receipt was 24.5 hours (IQR, 20–37 hours). No other patient developed HUS. Stools from 34 (32%) patients contained a non-STEC bacterial pathogen (S. sonnei, n = 26; Salmonella species, n = 6; Campylobacter jejuni, n = 1; Clostridium difficile, n = 1). No culture contained more than 1 bacterial enteric pathogen. For 2 of these 108 subjects, new-onset ulcerative colitis was found during their hospitalization, and their stool culture results were negative, as expected. Compared to children with another identifiable (usually infectious) cause of bloody diarrhea, children infected with STEC were older, were more likely to have abdominal tenderness, and had higher hemoglobin and creatinine concentrations at presentation. D-Dimer concentrations did not significantly differ between the groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical and Laboratory Characteristics in the STEC and Non-STEC Groups

| Characteristics | STEC Group (n = 10)a | Non-STEC Group (n = 98)a | Difference (95% CI) or P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Categorical | |||

| Male sex | 7/10 (70) (39 to 89) | 54/98 (55) (45 to 65) | 15 (−21 to 39) |

| Race | |||

| Black/African American | 6/10 (60) | 45/98 (46) | 14 (−20.2 to 42) |

| White | 3/10 (30) | 47/98 (48) | 18 (−18 to 42) |

| Asian | 1/10 (10) | 4/98 (4) | 6 (−6 to 42) |

| American Indian/Alaskan | 0/10 (0) | 1/98 (1) | 1 (−34 to 6) |

| Nonbloody diarrhea that turned bloody | 5/7 (71) (38 to 94) | 59/94 (63) (53 to 72) | 9 (−34 to 34) |

| Presence of incontinence | 1/9 (11) (1 to 40) | 40/98 (41) (32 to 51) | 30 (−10 to 45) |

| Vomiting | 2/9 (22) (46 to 52) | 30/97 (31) (22 to 41) | 9 (−30 to 30) |

| History of fever before presentation (family report) | 1/7 (14) (1 to 48) | 46/95 (48) (39 to 58) | 34 (−11 to 51) |

| History of abdominal pain | 9/9 (100) (74 to 100) | 68/87 (78) (69 to 86) | 22 (−16 to 32) |

| Pain worse during bowel movement | 4/7 (57) (25 to 85) | 41/51 (80) (68 to 90) | 23 (−11 to 61) |

| Antibiotic use in past 30 days | 1/8 (12) (1 to 43) | 7/46 (15) (7 to 27) | 3 (−40 to 21) |

| Contacts with nonbloody diarrhea | 2/8 (25) (5 to 57) | 21/91 (23) 15 to 32) | 2 (−21 to 42) |

| Contacts with bloody diarrhea | 2/8 (25) (5 to 57) | 4/90 (44%) (1 to 10) | 21% (−1 to 60) |

| Febrile in ED (≥38°C) | 0/7 (0) (0 to 31) | 12/89 (14) (8 to 22) | 14 (−31 to 23) |

| Ill appearing | 2/5 (40) (11 to 76) | 32/96 (33) (25 to 43) | 7 (−28 to 51) |

| Presence of dehydrationb | 1/6 (17) (1 to 53) | 33/96 (34) (25 to 44) | 18 (−30 to 37) |

| Abdominal tenderness on physical examination | 5/6 (83) (48 to 99) | 16/96 (17) (10 to 25) | 67 (19 to 84) |

| Continuous | |||

| Age (years) | 8.5 (6.75–11.5) | 3 (1–5.25) | <.001 |

| Duration of symptoms on presentation (days) | 5 (3–6) | 2 (2–5) | .26 |

| No. of stools in previous 24 hours | 11 (4–19) | 7 (4–10) | .35 |

| Temperature in ED (°C) | 36.8 (36.4–36.9) | 37 (36.7–37.4) | .18 |

| Heart rate (beats per min) | 84 (77–140) | 116 (100–136) | .10 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 117 (113–121) | 102 (92–112) | .05 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 73 (69–78) | 65 (56–74) | .08 |

| Respiratory rate (breaths per minute) | 24 (20–26) | 24 (20–29.5) | .75 |

| WBC count (103/µL) | 10.8 (8.3–13.3) | 9.9 (7.2–13.2) | .34 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.3 (11.9–14.3) | 12.1 (11.2–13.1) | .002 |

| Platelets (109/ µL) | 280 (209–314) | 313 (246–366) | .09 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.4 (0.38–0.53) | 0.3 (0.2–0.4) | .02 |

| D-Dimer 1 (µg/mL) | 0.54 (0.36–1.1) | 0.48 (0.32–0.89) | .22 |

| D-Dimer 2 (µg/mL) | 0.9 (0.44–1.63) | 0.54 (0.32–1.2) | .006 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; ED, emergency department; STEC, Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli; WBC, white blood cell.

aValues shown are n/N (%) (95% CI) or median (interquartile range).

bClinical dehydration score [28].

We further analyzed differences in clinical and laboratory characteristics of children with stool culture results that were positive for any organism and those with negative stool culture results (Table 2). As a group, patients whose stools contained any bacterial pathogen were older, had more stools in the 24 hours before presentation, more frequently reported fever and incontinence, and were more likely to have been in contact with people with bloody and nonbloody diarrhea.

Table 2.

Clinical and Laboratory Variables in the Positive- and Negative-Culture-Result Groups

| Characteristics | Positive-Culture-Result Group (n = 45)a | Negative-Culture-Result Group (n = 63)a | Difference (95% CI) or P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Categorical | |||

| Male sex | 26/45 (58) (13 to 39) | 35/63 (56) (23 to 47) | 22 (−18 to 22) |

| ≤5 years of age | 29/45 (64) (16 to 42) | 47/63 (75) (35 to 59) | 10. (−8 to 29) |

| Nonbloody diarrhea that turned bloody | 29/41 (71) (15 to 43) | 35/61 (57) (23 to 47) | 13 (−7 to 32) |

| >5 stools in past 24 hours | 33/40 (83) (18 to 48) | 31/61 (51) (19 to 43) | 32 (11 to 48) |

| >10 stools in past 24 hours | 16/44 (36) (5 to 27) | 10/63 (16) (3 to 17) | 21 (3 to 38) |

| Presence of incontinence | 12/40 (30) (2 to 22) | 6/62 (10) (0 to 12) | 20 (4 to 38) |

| Vomiting | 9/43 (21) (0.5 to 17.6) | 23/63 (37) (13 to 33) | 16 (−4 to 32) |

| Presence of fever before presentation (family report) | 30/39 (77) (16 to 44) | 16/62 (26) (7 to 25) | 51 (30 to 66) |

| History of abdominal pain | 33/40 (83) (19 to 47) | 38/52 (73) (25 to 51) | 9 (−10 to 27) |

| Pain worse during bowel movement | 20/26 (77) (5 to 35) | 25/30 (83) (10 to 41) | 6 (−17 to 30) |

| Antibiotic use past 30 days | 2/21 (10) (−4 to 8) | 6/31 (19) (−2 to 14) | 10 (−15 to 30) |

| Nonbloody contacts | 14/38 (37) (3 to 25) | 9/61 (15) (2 to 16) | 22 (3 to 41) |

| Bloody contacts | 5/36 (14) (−2 to 12) | 1/62 (2) (−2 to 4) | 12 (0 to 29) |

| Febrile in ED (≥38°C) | 6/38 (16) (−2 to 14) | 3/55 (5) (−2 to 8) | 10 (−3 to 27) |

| Ill appearing | 14/38 (37) (3 to 25) | 20/62 (32) (10 to 30) | 5 (−15 to 25) |

| Presence of dehydrationb | 13/40 (33) (3 to 23) | 21/62 (34) (11 to 31) | 1 (−19 to 20) |

| Abdominal tenderness on physical examination () | 8/40 (20) (−2 to 10) | 13/62 (21) (5 to 21) | 1 (−18 to 17) |

| Continuous | |||

| Age (years) | 4 (2–7.75) | 2 (1–6) | .013 |

| Duration of symptoms on presentation in days | 2.5 (2–4.25) | 3 (2–5) | .41 |

| No. of stools in previous 24 hours | 9.5 (6–15) | 6 (3.75–10) | <.001 |

| Temperature in ED (°C) | 37.2 (36.8–37.7) | 36.8 (36.5–37.2) | .003 |

| Heart rate (beats per minute) | 130 (91–145) | 110 (100–129) | .31 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 101 (93–115.5) | 103 (91–115.5) | .84 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 68 (56.5–73.5) | 65 (57.5–75) | .52 |

| Respiratory rate (breaths per minute) | 24 (22–26) | 24 (20–30.5) | .92 |

| WBC count (103/µL) | 10.5 (7.9–12.8) | 9.2 (7.2–13.2) | .23 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.1 (11.2–13.4) | 12.1 (11.3–13.1) | .45 |

| Platelets (109/ µL) | 292 (221.5–325.25) | 317 (251.5–401.0) | .02 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.4 (0.3–0.4) | 0.3 (0.2–0.4) | .001 |

| D-Dimer 1 (µg/mL) | 0.67 (0.49–1.06) | 0.38 (0.24–0.68) | <.001 |

| D-Dimer 2 (µg/mL) | 0.54 (0.39–1.22) | 0.36 (0.25–0.55) | .003 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; ED, emergency department; STEC, Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli; WBC, white blood cell.

aValues shown are n/N (%) (95% CI) or median (interquartile range).

bClinical Dehydration Score [28].

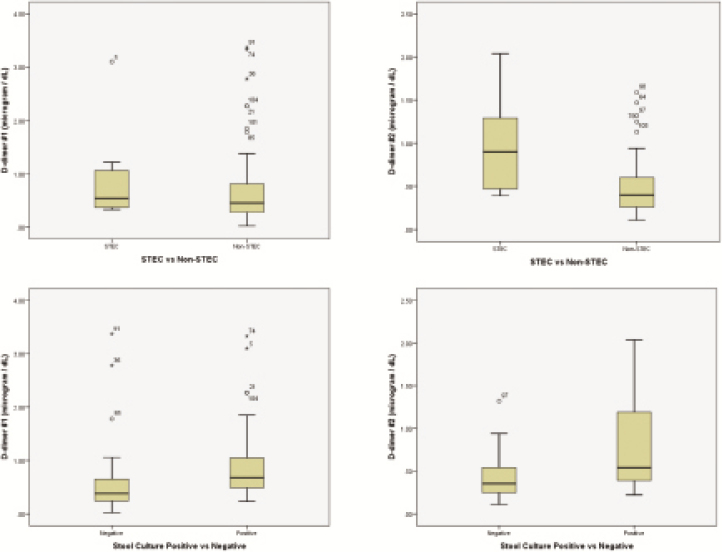

D-Dimer concentrations differentiated patients with bloody diarrhea caused by any bacterial pathogen from those with a negative stool culture result (positive likelihood ratio, 2.47 [95% CI, 1.6–3.82]) (Figure 1 and Table 3).

Figure 1.

D-Dimer concentrations: STEC versus non-STEC and positive- versus negative-culture-result groups. (Top Left) Comparison of initial D-dimer concentrations between the STEC and non-STEC groups. (Top Right) Comparison of subsequent D-dimer concentrations 12 to 24 hours after admission between the STEC and non-STEC groups. (Bottom Left) Comparison of initial D-dimer concentrations between the positive and negative stool culture groups. (Bottom Right) Comparison of subsequent D-dimer concentrations 12 to 24 hours after admission between the positive and negative stool culture groups.

Table 3.

Initial D-Dimer Test Characteristics in STEC and Non-STEC and Positive- and Negative-Culture-Result Groups

| Test Characteristics | STEC vs Non-STEC Group | Positive- vs Negative-Culture-Result Group |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity (% [95% CI]) | 70.0 (34.8–93.0) | 75 (58.8–87.3) |

| Specificity (% [95% CI]) | 54.7 (43.6–65.4) | 69.6 (55.9–81.2) |

| Positive predictive value (% [95% CI]) | 15.2 (6.4–29.0) | 63.8 (48.5–77.3) |

| Negative predictive value (% [95% CI]) | 94 (83.4–98.7) | 79.6 (65.7–89.7) |

| Positive likelihood ratio (95% CI) | 1.5 (1.0–2.46) | 2.47 (1.6–3.82) |

| Negative likelihood ratio (95% CI) | 0.55 (0.2–1.4) | 0.36 (0.2–0.63) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; STEC, Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to have focused exclusively on a cohort of children who presented to a pediatric ED with acute bloody diarrhea. As expected, many of them were infected with a bacterial enteric pathogen. Although some clinical and laboratory features increased the likelihood of an STEC infection, no characteristic was categorically distinguishing.

Chandler et al [5] found D-dimer concentrations in patients with E coli O157:H7 infection to be elevated significantly over those in healthy controls, but they did not test patients infected with any other bacterial pathogen. We, too, documented concentrations of circulating D-dimers well above normal in STEC-infected patients; however, these abnormal D-dimer concentrations did not have sufficient sensitivity or specificity to distinguish STEC infections from other bacterial causes of bloody diarrhea. The elevated D-dimer concentration in those with any bacterial etiology indicates that some form of vascular prothrombotic activation resulting in fibrin deposition occurred in these patients, which suggests that the vascular system might play some role in host response to enteric infections and should be the subject of future investigations. Elevated D-dimer concentrations cannot be explained simply as a host response to a breach in the intestinal vasculature, because the children with bloody diarrhea without an identifiable microbial cause had considerably lower circulating D-dimer concentrations.

Holtz et al [1] proposed characteristics of patients with an STEC infection, including nonbloody diarrhea that becomes bloody after 1 to 3 days, no fever at the point of presentation, a tender abdomen, more than 5 stools in the previous 24 hours, and pain worsening during defecation. We found that abdominal tenderness on physical examination differed significantly between children infected with STEC and those with another bacterial pathogen or a negative stool culture result. Interesting to note is that although they resembled data from an ED study in Seattle, the duration of illness, defecation frequency, and report of pain during defecation also were not differentiating. Nonbloody diarrhea that subsequently became bloody, number of stools in the previous 24 hours, and history of abdominal pain were not differentiating.

Klein et al [28] identified travel outside the United States, history of blood in stool, greater than 10 episodes of diarrhea in previous 24 hours, abdominal pain, and abdominal tenderness as characteristics of enteric bacterial infection. History of antibiotic use in the previous 30 days, duration of symptoms greater than 10 days, and vomiting were more characteristic of nonbacterial infections. In our study, children with positive stool culture results (all bacterial pathogens) were older, had a greater number of stools in the previous 24 hours, had a history of fever and incontinence, and were more likely to have been in contact with people with diarrhea. Ten percent of children in the positive- culture-result group and 19% of those in the negative-culture- result group reported recent previous antibiotic use. Unlike in the comparison of the STEC and non-STEC groups, we did not find that abdominal pain or tenderness distinguished between the culture-positive and culture-negative groups; however, D-dimer concentrations were significantly higher in the group of those who tested positive for any bacterial enteric pathogen.

Although none of the clinical or laboratory risk factors seem to have enough sensitivity in isolation to differentiate patients with an STEC infection from those with another cause of bloody diarrhea at presentation, we were able to profile these children partially. D-Dimer concentrations distinguished patients with a bacterial etiology from those for whom no bacterial etiology was identified with stool culture. These data can be used to build larger studies that integrate clinical and laboratory variables to derive clinical decision models and pathways in patients with bloody diarrhea. Creating such models will be important particularly in making judicious and cost-effective use of emerging and promising technologies such as multiplex polymerase chain reaction analysis of stool [30].

New rapid molecular diagnostic tests such as multiplex polymerase chain reaction will likely improve detection of STEC infection in the ED in the near future. However, the indiscriminate use of these tests, particularly in patients with a low pretest probability of STEC infection, might result in false-positive results and high costs. Decision models for the use of molecular testing, including clinical factors and simple laboratory tests such as measuring a patient’s D-dimer concentration, could be studied to increase the yield and decrease the cost of these emerging technologies. Although applying exclusion criteria for culture analysis to children with acute bloody diarrhea might be impractical, tests such as the measurement of D-dimer concentrations might be useful in cases of nonbloody diarrhea, in which a bacterial pathogen is much less likely to be the culprit. However, until these data are validated, we believe that all children who present to a pediatric ED with acute painful bloody diarrhea should be assumed to have an STEC infection and therefore be at risk for HUS.

We note several limitations to this study. First, our relatively small sample size did not enable us to construct complex decision models or study subgroups according to time of presentation (as clinical and laboratory profiles change over the course of an infection). However, all our patients presented within 1 day of the identification of blood in the stool. Second, in view of geographic, interinstitutional, and seasonal differences in the etiologies and incidences of bloody diarrhea, our data might not be universally applicable. Nonetheless, to our knowledge, this is the largest study to date to have focused exclusively on ED presentation of acute bloody diarrhea in children and, as such, can be used to inform future studies.

CONCLUSION

In this study, D-dimer concentrations did not have sufficient sensitivity or specificity to distinguish children with an STEC infection from those with any other cause of bloody diarrhea at the time of presentation. However, D-dimer concentrations might be able to distinguish children with bloody diarrhea from an infectious etiology and those with any other cause of bloody diarrhea. We found older age and abdominal tenderness to be statistically significant in distinguishing children with an STEC infection; however, it would be difficult to clinically dismiss the risk of STEC infection in younger children or those without abdominal tenderness. At this time, no reliable clinical or laboratory predictors accurately identify children with an STEC infection and who therefore are at risk of HUS at the time of presentation. Therefore, we strongly believe that any child with bloody diarrhea should be considered to have an emergent condition, such as an STEC infection, that requires timely diagnosis and intervention.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society online.

Author contributions. R. S. M. conceptualized and designed the study, carried out the initial analyses, drafted the initial manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted; P. I. T., D. J. D., and D. S. conceptualized and designed the study, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted; and R. C. assisted with statistical analysis and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments. We thank our patients and their families, the ED and inpatient nursing staff, and our clinical microbiologists at Washington University in St. Louis for their participation in this project.

Financial support. This study was supported by the Barnes-Jewish Hospital Foundation and the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences (grant UL1 TR000448) and the National Institutes of Health (grant P30 DK052574 [Biobank, Digestive Disease Research Core Center] to P. I. T.).

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Holtz LR, Neill MA, Tarr PI. Acute bloody diarrhea: a medical emergency for patients of all ages. Gastroenterology 2009; 136:1887–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Denno DM, Shaikh N, Stapp JR, et al. Diarrhea etiology in a pediatric emergency department: a case control study. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 55:897–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Klein EJ, Stapp JR, Clausen CR, et al. Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli in children with diarrhea: a prospective point-of-care study. J Pediatr 2002; 141:172–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Petruzziello-Pellegrini TN, Yuen DA, Page AV, et al. The CXCR4/CXCR7/SDF-1 pathway contributes to the pathogenesis of Shiga toxin-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome in humans and mice. J Clin Invest 2012; 122:759–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chandler WL, Jelacic S, Boster DR, et al. Prothrombotic coagulation abnormalities preceding the hemolytic-uremic syndrome. N Engl J Med 2002; 346:23–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wong CS, Jelacic S, Habeeb RL, et al. The risk of the hemolytic-uremic syndrome after antibiotic treatment of Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections. N Engl J Med 2000; 342:1930–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Oakes RS, Kirkham JK, Kirkhamm JK, et al. Duration of oliguria and anuria as predictors of chronic renal-related sequelae in post-diarrheal hemolytic uremic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol 2008; 23:1303–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Loirat C. Post-diarrhea hemolytic-uremic syndrome: clinical aspects. Arch Pediatr 2001; 8:776s–84s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Siegler RL, Milligan MK, Burningham TH, et al. Long-term outcome and prognostic indicators in the hemolytic-uremic syndrome. J Pediatr 1991; 118:195–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Siegler RL, Pavia AT, Christofferson RD, Milligan MK. A 20-year population-based study of postdiarrheal hemolytic uremic syndrome in Utah. Pediatrics 1994; 94:35–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Garg AX, Suri RS, Barrowman N, et al. Long-term renal prognosis of diarrhea- associated hemolytic uremic syndrome: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. JAMA 2003; 290:1360–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Robson WL, Leung AK, Brant R. Relationship of the recovery in the glomerular filtration rate to the duration of anuria in diarrhea-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome. Am J Nephrol 1993; 13:194–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tönshoff B, Sammet A, Sanden I, et al. Outcome and prognostic determinants in the hemolytic uremic syndrome of children. Nephron 1994; 68:63–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hüseman D, Gellermann J, Vollmer I, et al. Long-term prognosis of hemolytic uremic syndrome and effective renal plasma flow. Pediatr Nephrol 1999; 13:672–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mizusawa Y, Pitcher LA, Burke JR, et al. Survey of haemolytic-uraemic syndrome in Queensland 1979–1995. Med J Aust 1996; 165:188–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Spizzirri FD, Rahman RC, Bibiloni N, et al. Childhood hemolytic uremic syndrome in Argentina: long-term follow-up and prognostic features. Pediatr Nephrol 1997; 11:156–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gianantonio CA, Vitacco M, Mendilaharzu F, et al. The hemolytic-uremic syndrome. Nephron 1973; 11:174–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mencía Bartolomé S, Martínez de Azagra A, de Vicente Aymat A, et al. Uremic hemolytic syndrome. Analysis of 43 cases. An Esp Pediatr 1999; 50:467–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Balestracci A, Martin SM, Toledo I, et al. Capacity of the oligoanuric period in the prediction of renal sequelae in patients with postdiarrheal hemolytic uremic syndrome. Arch Argent Pediatr 2012; 110:221–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stapp JR, Jelacic S, Yea YL, et al. Comparison of Escherichia coli O157:H7 antigen detection in stool and broth cultures to that in sorbitol-MacConkey agar stool cultures. J Clin Microbiol 2000; 38:3404–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Freedman SB, Eltorki M, Chui L, et al. Province-wide review of pediatric Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli case management. J Pediatr 2017; 180:184–190.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ake JA, Jelacic S, Ciol MA, et al. Relative nephroprotection during Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections: association with intravenous volume expansion. Pediatrics 2005; 115:e673–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hickey CA, Beattie TJ, Cowieson J, et al. Early volume expansion during diarrhea and relative nephroprotection during subsequent hemolytic uremic syndrome. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2011; 165:884–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mody RK, Gu W, Griffin PM, et al. Postdiarrheal hemolytic uremic syndrome in United States children: clinical spectrum and predictors of in-hospital death. J Pediatr 2015; 166:1022–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Balestracci A, Martin SM, Toledo I, et al. Dehydration at admission increased the need for dialysis in hemolytic uremic syndrome children. Pediatr Nephrol 2012; 27:1407–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ardissino G, Daccò V, Testa S, et al. Hemoconcentration: a major risk factor for neurological involvement in hemolytic uremic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol 2015; 30:345–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Grisaru S XJ, Samuel S, Hartling L, et al. Associations between hydration status, intravenous fluid administration, and outcomes of patients infected with Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli; a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr 2017;171:68–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Klein EJ, Boster DR, Stapp JR, et al. Diarrhea etiology in a children’s hospital emergency department: a prospective cohort study. Clin Infect Dis 2006; 43:807–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wong CS, Mooney JC, Brandt JR, et al. Risk factors for the hemolytic uremic syndrome in children infected with Escherichia coli O157:H7: a multivariable analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 55:33–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stockmann C PA, Graham B, Vaughn M, et al. Detection of 23 gastrointestinal pathogens among children who present with diarrhea. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 2017: 6:231–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.