Abstract

Molecular docking provides a computationally efficient way to predict the atomic structural details of protein–RNA interactions (PRI), but accurate prediction of the three-dimensional structures and binding affinities for PRI is still notoriously difficult, partly due to the unreliability of the existing scoring functions for PRI. MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA are more theoretically rigorous than most scoring functions for protein–RNA docking, but their prediction performance for protein–RNA systems remains unclear. Here, we systemically evaluated the capability of MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA to predict the binding affinities and recognize the near-native binding structures for protein–RNA systems with different solvent models and interior dielectric constants (εin). For predicting the binding affinities, the predictions given by MM/GBSA based on the minimized structures in explicit solvent and the GBGBn1 model with εin = 2 yielded the highest correlation with the experimental data. Moreover, the MM/GBSA calculations based on the minimized structures in implicit solvent and the GBGBn1 model distinguished the near-native binding structures within the top 10 decoys for 117 out of the 148 protein–RNA systems (79.1%). This performance is better than all docking scoring functions studied here. Therefore, the MM/GBSA rescoring is an efficient way to improve the prediction capability of scoring functions for protein–RNA systems.

Keywords: binding free energy, docking, MM/GBSA, MM/PBSA, protein–RNA interactions

INTRODUCTION

In many biological processes, protein–RNA interactions play crucial roles, such as regulation of gene expression, RNA splicing, protein synthesis, etc. (Glisovic et al. 2008; Licatalosi et al. 2008; Wang et al. 2012). Some protein–RNA interactions are even involved in a number of diseases, ranging from neurological disorders to cancers (Lukong et al. 2008). In fact, RNA rarely acts alone, and most RNAs function only in complex with specific proteins (Dawson and Bujnicki 2016). Therefore, revealing the protein–RNA specific recognitions and binding patterns is quite significant for both understanding the important processes of life and designing new drugs (Zhang et al. 2017). Several experimental methods have been developed to determine RPIs (Anko and Neugebauer 2012; Campbell and Wickens 2015), such as ultraviolet crosslinking and immunoprecipitation (CLIP) (Ule et al. 2003), high-throughput sequencing of CLIP cDNA library (HITS-CLIP) (Licatalosi et al. 2008), photoactivatable-ribonucleoside-enhanced crosslinking and immunoprecipitation (PAR-CLIP) (Hafner et al. 2010), individual nucleotide resolution CLIP (iCLIP) (Konig et al. 2010), targets of RNA-binding protein identified by editing (TRIBE) (McMahon et al. 2016), covalent RNA marks (Lapointe et al. 2015), interactome capture (IC) (Castello et al. 2012), and serial RNA interactome capture (Ser IC) (Conrad et al. 2016), etc. By combining high-throughput experimental methods with cross-linking, next-generation sequencing, microarrays, and mass spectrometry, thousands of proteins interacting with RNAs have been simultaneously identified in human cells, where 30% of these had not been reported as RNA-binding proteins previously (Hafner et al. 2010; Baltz et al. 2012; Castello et al. 2012; Ray et al. 2013; Iwakiri et al. 2016). The best way to uncover the underlying mechanisms of PRI is to analyze the atomic details of interactions based on the three-dimensional structures of protein–RNA complexes (Iwakiri et al. 2016). However, there is a clear underrepresentation of protein–RNA structures in the RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) because the experimental structural determination of protein–RNA complexes at high resolution is still challenging and much more difficult than that of the isolated components (Perez-Cano et al. 2017). By August 2017, the number of biological macromolecular structures reached up to 131,905 in PDB, but only 2028 are protein–RNA complexes. More specifically, 1556 protein–RNA complexes were solved by X-ray crystallography, 115 by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, 351 by electron microscopy, and six by other methods.

As a promising tool that is complementary to experimental methods, the computational technique is urgently required to elucidate PRI at the atomic level (Puton et al. 2012; Tuszynska et al. 2014; Si et al. 2015; Iwakiri et al. 2016). In recent years, some protein–protein docking methods have been modified and adapted to deal with nucleic acid molecules as receptors and/or ligands (Puton et al. 2012). However, there are many different features between protein–RNA interfaces and protein–protein interfaces (Huang et al. 2013): (i) The atom packing of protein–RNA interfaces is looser than that of protein–protein interfaces; (ii) positively charged amino acids and negatively charged phosphate groups in RNA prefer to appear at protein–RNA interfaces (Perez-Cano et al. 2010); (iii) stacking interactions of the bases of nucleotides with aromatic rings of charged amino acids often occur at protein–RNA interfaces (Gupta and Gribskov 2011; Iwakiri et al. 2012; Li et al. 2012). These features of protein–RNA interfaces are largely responsible for the poor prediction capability for protein–RNA complexes by using protein–protein docking approaches.

To the best of our knowledge, only two standalone docking software packages, including NPDock (Tuszynska et al. 2015) and 3dRPC (Huang et al. 2013), have been developed specifically for predicting protein–RNA complexes. Similar to most docking protocols, a protein–RNA docking approach includes two steps: sampling and scoring (Zhang et al. 2017). Several approaches have been developed to solve the sampling issue, such as the information-driven method used in HADDOCK (Dominguez et al. 2003), the fast Fourier transformation (FFT) algorithm in GRAMM (Vakser and Aflalo 1994) and FTDock (Katchalskikatzir et al. 1992), the distance geometry algorithm in DOCK (Kuntz et al. 1982), and the genetic algorithm in DARWIN (Taylor and Burnett 2000). However, there is no ideal scoring function developed specifically for protein–RNA scoring, where the scoring function is the real way to characterize the main difference between protein–protein interactions and protein–RNA interactions (Zhang et al. 2017). Thus, there is an urgent need to explore a reliable scoring function specific to protein–RNA docking. Up to now, several scoring methods have been developed for protein–RNA docking, such as the QUASI-RNP and DARS-RNP developed by Tuszynska and Bujnicki (2011), DECK-RP by Huang et al. (2013), ITScore-PR by Huang and Zou (2014), RpveScore by Li (Zhang et al. 2017), and 3dRPC-Score by Xiao (Li et al. 2017), etc. Also, several other scoring methods originally developed for protein–protein docking were modified to adapt the systems involving RNA and DNA, such as the modified RosettaDock (Guilhot-Gaudeffroy et al. 2014) and the modified ZDOCK (Iwakiri et al. 2016). These scores have gained success in some protein–RNA systems. Kashyap (Kashyap et al. 2015) found that the moderate-affinity hydrogen bonding network between the nitrogen bases in the stem–loop RNA and a concave face on the RRM surface primarily mediate TAF15-RRM RNA interaction. Fan et al. (2017) found that the poly(A)-like sequence and sMLD of tmRNA are all involved in the protein–RNA interaction, through charged interaction and hydrogen bonds. However, the few reported docking algorithms for PRI show limited predictive capability, mainly due to incomplete sampling of the conformational space of both protein and RNA molecules, as well as the inaccuracy of the scoring function in identifying the correct docking models (Perez-Cano et al. 2017). As such, the reliability of their predictions may be compromised (Chen et al. 2004; Zheng et al. 2007; Perez-Cano et al. 2010; Setny and Zacharias 2011; Tuszynska and Bujnicki 2011; Walia et al. 2012). Fortunately, three protein–RNA docking benchmarks were published (Barik et al. 2012; Perez-Cano et al. 2012; Huang and Zou 2013), which provide an opportunity to evaluate and optimize the existing protein–RNA docking protocols more exhaustively and objectively, and finally construct a framework to develop new ones (Perez-Cano et al. 2017).

The protein–RNA interactions are difficult to be predicted or modeled because of two reasons: (i) the inherent flexibility of RNA molecules and (ii) the highly negatively charged RNA molecules (Guilhot-Gaudeffroy et al. 2014). Numerous studies highlighted the importance of electrostatic interactions between the positively charged amino acids of proteins and the negatively charged phosphate groups of RNA (Allers and Shamoo 2001; Ellis et al. 2007; Bahadur et al. 2008; Gupta and Gribskov 2011; Kondo and Westhof 2011; Iwakiri et al. 2012, 2013), which is one of the major challenges for developing a reliable scoring function to model the protein–RNA interactions. Due to the good performance of the molecular mechanics/Poisson Boltzmann surface area (MM/PBSA) and molecular mechanics/generalized Born surface area (MM/GBSA) methodologies in predicting protein–small molecule complexes and protein–protein complexes, these two approaches have become attractive to predicting protein–RNA complexes (Genheden and Ryde 2015). Our group has comprehensively evaluated the performance of MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA in predicting the binding affinities for extensive protein–small molecule data sets and protein–protein data sets and has examined their reranking capability to recognize the near-native binding poses from the decoys generated by traditional molecular docking (Hou et al. 2011a,b; Xu et al. 2013; Sun et al. 2014a,b; Chen et al. 2016). However, up to now, no study has been done to evaluate the performance of MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA for protein–RNA systems based on extensive benchmarks. Hence, in this study, we evaluated the capability of MM/GBSA and MM/PBSA in predicting the binding affinities of 55 protein–RNA complexes. Then we investigated the ranking capability of MM/GBSA and MM/PBSA to identify the near-native structures from the protein–RNA decoys generated by the modified ZDOCK based on three protein–RNA complex benchmarks (Barik et al. 2012; Perez-Cano et al. 2012; Huang and Zou 2013). The conclusion of the MM/GBSA application from this study is valid only in the case when both protein and RNA structures have been experimentally solved but the complex structure or the binding free energy is unknown.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Performance of the existing docking software in predicting binding affinities of protein–RNA interactions

Before investigating the performance of MM/GBSA and MM/PBSA in predicting protein–RNA interactions, we first tested the performance of three docking scores, DARS, QUASI, and DECK, to predict the binding affinities (pKd) for the 55 protein–RNA complexes in data set I. As shown in Figure 1, all correlation coefficients between the docking scores and the observed pKds are relatively low, where QUASI shows better prediction capability (rp = −0.468 and rs = −0.438) than DARS (rp = −0.414 and rs = −0.379) and DECK (rp = −0.034 and rs = 0.018). This is to say, the existing docking scores might not give reliable predictions for protein–RNA interactions, and we need to explore better scoring methods for the prediction of protein–RNA binding affinities. According to our previous experience in protein–small molecule and protein–protein predictions that MM/GB(PB)SA rescoring may improve the performance of traditional molecular docking calculations, therefore, MM/GBSA and MM/PBSA were used to predict the binding affinities of the protein–RNA complexes in data set I.

FIGURE 1.

Correlation between docking scores (DECK, DARS, and QUASI) and experimental data (pKd). rp is Pearson correlation coefficient and rs is Spearman ranking coefficient.

Investigating the MM/GBSA approach in predicting pKds with the implicit solvent model

First, the 55 complexes in data set I were minimized in the implicit solvent model, and then their binding free energies were predicted by MM/GBSA. As shown in Figure 2, GBGBn1 exhibits the best prediction capability, and GBGBn2 shows the worst capability. The MM/GBSA predictions based on GBGBn1 and εin = 2 yield the best correlation between the predicted ΔGbinds and pKds (rp = −0.539 and rs = −0.483). When εin was set to 2, the MM/GBSA predictions based on GBHCT, GBOBC1, and GBOBC2 exhibit similar prediction capability (rp = −0.522 to −0.524), and those based on GBGBn2 still show the worst prediction capability (rp = −0.248 and rs = −0.109). The results reported in this study are different from those reported in our previous study for protein–protein systems, where the ΔGs calculated from the GBOBC1 model with a low interior dielectric constant (εin = 1) show the best correlation with the experimental binding affinities (Hou et al. 2011a; Chen et al. 2016). What is noteworthy is that the GBn method is not recommended for systems involving nucleic acids according to the AMBER14 reference manual. However, in this study GBn is the best choice for the binding affinity predictions. One possible reason may be that this study focuses on the prediction of binding affinities based on crystal structures rather than MD trajectories.

FIGURE 2.

(A) The correlations (|rp|) of the experimental pKd and ΔGs predicted by MM/GBSA based on the minimized structures in implicit solvent. (B) Scatter plots of the experimental pKd (x-axis) versus ΔGs predicted by MM/GBSA (y-axis) based on the minimized structures in the implicit solvent.

Investigating the εin effects in predicting pKds with the implicit solvent model

As shown in our previous studies, the MM/GBSA and MM/PBSA approaches are quite sensitive to εin for protein–small molecule systems and protein–protein systems (Dwyer et al. 2000; DeLano 2002; Kastritis and Bonvin 2013; Chen et al. 2016). But the phenomenon is not noticeable in protein–RNA systems. The MM/GBSA calculations with εin = 1 can get the remarkable improved prediction capabilities compared with εin = 2, 4, or 6 in protein–protein systems. However, the scenario is quite different for protein–RNA systems with most GB models (GBHCT, GBOBC2, and GBGBn1), where when εin is set to 1, 2, 4, and 8, the rps range from −0.508 to −0.524 and the rss range from −0.470 to −0.483, indicating that the protein–RNA systems are not quite sensitive to the change of the interior dielectric constant in most cases. Whereas there is an exception of the GBGBn2 model, the prediction accuracy is related to εin (Fig. 2). In summary, for the minimized structures with the ff14SB force field, the MM/GBSA calculations based on the GBGBn1 model with a relatively low interior dielectric constant (εin = 2) can achieve the best predictions (rp = −0.539 and rs = −0.483, Fig. 2).

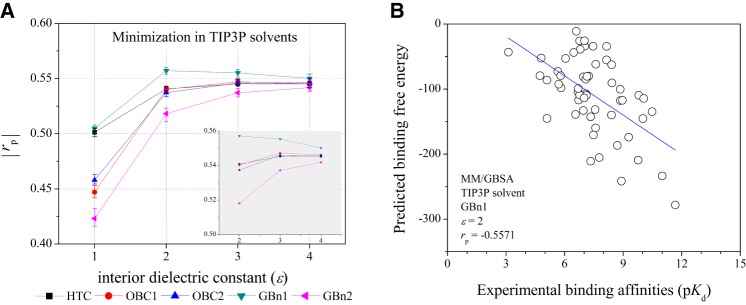

Improving the performance of MM/GBSA with the explicit solvent model

To study the influence of solvent models on ΔGs calcualtions, we also calculated the ΔGs based on the minimized structures with the TIP3P explicit solvent model. As shown in Figure 3, the ΔGs calculated by MM/GBSA based on GBGBn1 and εin = 2 yield the best correlation with the experimental data (rp = −0.557 and rs = −0.519, Fig. 3). On the whole, the prediction accuracy of MM/GBSA based on the structures minimized with explicit solvent is better than that based on the structures minimized with implicit solvent. Especially, the rps based on the minimized structures with the explicit water model are −0.423, −0.518, −0.537, and −0.542 for εin = 1, 2, 4, and 8, respectively, using the GBGBn2 model, which are significantly improved in comparison with those estimated using the implicit water model (0.172, −0.247, −0.467, and −0.508 for εin = 1, 2, 4, and 8, respectively). Taken together, our results suggest that minimizations in explicit water are necessary to improve the prediction capability of MM/GBSA for protein–RNA systems. The predictions given by MM/GBSA based on the GBGBn1 model with εin = 2 can yield the best correlation between the predicted binding free energies and the experimental data (rp = −0.557 and rs = −0.519), and they are also better than those given by MM/PBSA (rp = −0.501, see below) and a number of empirical scoring functions used in protein–RNA docking (rp = −0.468).

FIGURE 3.

(A) The |rp|s of the experimental pKd and ΔGs predicted by MM/GBSA based on the minimized structures in explicit solvent model. (B) Scatter plots of the experimental pKd (x-axis) versus ΔGs predicted by MM/GBSA (y-axis) based on the minimized structures in explicit solvent model.

Investigating the effect of MD simulation on the performance of MM/GBSA

To take the conformation fluctuation into account, we then ran 1 nsec MD simulations for all the complexes using two types of solvent models (TIP3P explicit solvent and GB implicit solvent) and calculated the ΔGs based on the MD trajectories. As shown in Figure 4, for implicit solvent, the predictions of MM/GBSA based on the 1 nsec MD trajectories are very good, with the rps of GBHCT, GBOBC1, GBOBC2, and GBGBn1 ranging from −0.508 to −0.555 and rss = −0.497 to −0.515.

FIGURE 4.

(A) The |rp|s between the experimental pKd and ΔGs predicted by MM/GBSA based on the 1 nsec MD trajectories. (B) Scatter plots of the experimental pKd (x-axis) versus ΔGs predicted by MM/GBSA (y-axis) based on the 1 nsec MD trajectories.

As shown in Figure 4, for MM/GBSA, the GBGBn1 model with εin = 8 can achieve the best predictions (rp = −0.578 and rs = −0.568). On the whole, the prediction based on the 1 nsec MD trajectories in explicit solvent is better than those based on the implicit solvent model. The results show that compared with the minimized structures, short MD simulations (1 nsec) in the TIP3P explicit solvent can slightly improve the prediction accuracy (as shown in Fig. 4). However, considering the high computational cost, MD simulations may not be the best choice for most protein–RNA systems, which typically have 100,000+ atoms in TIP3P water boxes.

Performance of MM/PBSA in predicting pKds

Besides MM/GBSA, we have also examined the predicting accuracy of MM/PBSA. As shown in Figure 5, based on the minimized structures, the rps ranged from −0.04 to −0.43, whereas the prediction accuracy of MM/PBSA can be dramatically improved based on the 1 nsec MD trajectories (rps = −0.24 to −0.50 and rss = −0.29 to −0.50), indicating that MM/PBSA, a physically more rigorous model, is more sensitive to the conformation samplings of the binding poses. This observation is consistent with our previous studies on protein–small molecule systems (Chen et al. 2016). Taking all the results into account, MM/PBSA performs much worse than MM/GBSA, and even worse than some docking scoring functions. Thus, MM/PBSA is not recommended to predict the binding free energies for protein–RNA systems. Again, this observation is also consistent with our previous study (Hou et al. 2011b; Chen et al. 2016).

FIGURE 5.

The |rp|s of the experimental pKd and ΔGs predicted by MM/PBSA.

Performance of docking software in identifying the near-native structures

In protein–RNA docking, RNAs are usually considered as ligands, and a decoy structure will be considered as a near-native structure if the RMSD between the docked RNA and the crystallized RNA is less than a threshold. However, up to now, there is no unified criterion for the selection of a RMSD threshold. A threshold of 10 Å was used in Iwakiri's study (Iwakiri et al. 2016), while a threshold of 5 Å was used in Puton's study (Puton et al. 2012). Hence, we first evaluated the effect of the threshold values on the success rates of protein–RNA docking. ZDOCK_M was used to generate the rigid-body docking decoys for the protein–RNA complexes with the bound-state structures as the reference coordinates. Here, we investigated three thresholds of RMSD values (3 Å, 5 Å, and 10 Å). The calculated success rates for each threshold value are illustrated in Figure 6.

FIGURE 6.

Percentage of cases in which a near-native solution is found within the 3600 decoys for the three benchmark cases according to different thresholds of “near-native” structures.

When 3 Å was used as the threshold, we found that ZDOCK_M was able to produce near-native structures 77%, 82%, and 78% of protein–RNA complexes collected in the Barik benchmark, Huang benchmark, and Perez benchmark, respectively (Barik et al. 2012; Perez-Cano et al. 2012; Huang and Zou 2013). The success rates could reach up to 93%, 96%, and 91%, when 5 Å was used as the threshold, and 98%, 97%, and 96% with 10 Å as a threshold for the three above-mentioned data sets sequentially. Hence, we chose 5 Å as the threshold because of the reasonable success rate.

Figure 7 illustrates the performance of the four docking scores (ZDOCK_M, 3dRPC, DARS, and QUASI) evaluated by the three benchmarks. For the Barik benchmark, the success rates of ZDOCK_M for the top1, top10, and top100 predicted decoys are 54.6%, 70.4%, and 84.0%, respectively. In contrast, the success rates for DARS decrease to 31.8%, 50.0%, and 65.9% for the top1, top10, and top100 predicted decoys, respectively. And a similar result was obtained for the QUASI scoring function: 29.5% for top1, 43.1% for top10, and 70.4% for top100. It should be noted that 3dRPC performs the worst in the four docking scores. Moreover, ZDOCK_M performs the best among the four docking scores for the other two benchmarks (Huang benchmark and Perez benchmark). In summary, counting the average numbers of the near-native structures found within the top10 predicted structures (decoys), the hits generated by ZDOCK_M were almost 1.5 – 1.9 times more than those generated by 3dRPC, DARS, and QUASI for the Barik benchmark, 1.6 – 3.0 times more for the Huang benchmark and 1.6–2.0 times more for the Perez benchmark. Therefore, ZDOCK_M is the best docking score in recognizing the near-native structures for protein–RNA systems.

FIGURE 7.

Comparison of prediction performances for ZDOCK_M, 3dRPC, DARS, and QUASI for (A) 45 protein–RNA complexes of Barik benchmark, (B) 71 protein–RNA complexes of Huang benchmark, (C) 104 protein–RNA complexes of Perez benchmark. Success rates for top100-scored decoys are shown in an inset. Success rate is the percentage of target protein–RNA complexes for which the docking software matches at least one near-native prediction within a given number of top-scored decoys.

As mentioned above, there is no widely established criterion to define a success rate. Thus, before comparing the success rates of different scoring functions, we have to define a ranking level. However, this is not an easy thing because different criterions may lead to very different results. For example, compared to the Barik benchmark, in terms of the top1 level, DARS is better than QUASI (the success rate is 31.8% for DARS and 29.5% for QUASI). While in terms of the top15 level, the success rate of DARS is the same as that of QUASI (50.0%). However, in terms of the top18 level, DARS is worse than QUASI, where the success rate is 50.0% for DARS and 52.2% for QUASI. Therefore, a comprehensive index is necessary to characterize the overall performance of the scoring functions. Here, the area under the success rate curve (ASC) was used as an index to evaluate the performance of docking scores and other rescoring results (i.e., MM/GB[PB]SA). The larger the value of ASC, the better the ranking capability of a scoring function. Taking the Barik data set (Fig. 7A) as an example, the ASC values for ZDOCK_M, 3dRPC, DARS, and QUASI are 3148, 2890, 3008, and 2950, respectively. Hence, the order of the overall performance is ZDOCK_M > DARS > QUASI > 3dRPC.

Capability of MM/GBSA in recognizing the correct protein–RNA binding poses

As shown above, MM/GBSA has an outstanding prediction capability in predicting the binding affinities for protein–RNA systems, implying that MM/GBSA may have great potential to identify the correct binding structures from the decoys generated by protein–RNA docking. Therefore, we examined the reranking capability of MM/GBSA using the three benchmarks. For each protein–RNA complex, the top100 structures ranked by the ZDOCK_M scores were minimized in an implicit solvent model (GBOBC1) and an explicit solvent model, and were rescored by MM/GBSA. The reranking capabilities of MM/GBSA with four different interior dielectric constants (1, 2, 4, and 8) were compared. The calculated ASCs of MM/GBSA are shown in Figure 8.

FIGURE 8.

The area under the success rate curves of the MM/GBSA rescoring. (A) Minimized structure in implicit solvent of Barik benchmark; (B) minimized structure in implicit solvent of Huang benchmark; (C) minimized structure in implicit solvent of Perez benchmark; (D) minimized structure in TIP3P solvent of Barik benchmark; (E) minimized structure in TIP3P solvent of Huang benchmark; (F) minimized structure in TIP3P solvent of Perez benchmark.

The prediction accuracy of the MM/GBSA calculations based on the minimized structures in the implicit water model could be improved with lower εin. When εin was set to 1, MM/GBSA yielded the best ranking capability among the four dielectric constants (εin = 1, 2, 4, and 8), no matter which GB model was used in MM/GBSA. Among the five GB models, the GBGBn1 model exhibits the best ranking capability, where the ASC is 81.6 for the Barik benchmark, 87.9 for the Huang benchmark, and 84.8 for the Perez benchmark. On the contrary, based on the minimized structures in the explicit water model, the prediction accuracy of MM/GBSA could be improved with a higher εin. When εin was set to 8, MM/GBSA yields a better ranking capability, where the ASC is 76.6 for the Barik benchmark, 81.6 for the Huang benchmark, and 81.6 for the Perez benchmark. Through comparing the results based on implicit and explicit water models, we reach a conclusion that the explicit water model is not quite necessary to improve the reranking capability of MM/GBSA.

After removing the redundant crystal structures collected by the three benchmarks, we generated a database with 148 protein–RNA complexes. The comparison of ZDOCK_M, 3dRPC, NPDock (DARS and QUASI), and MM/GBSA (GBGBn1 model) is shown in Figure 9. In terms of the top1 level and the top10 level, the success rates of ZDOCK_M are 57.4% and 72.3%, respectively, which are better than those of DARS (29.0% and 45.2%), QUASI (21.0% and 39.9%), and 3dRPC (12.2% and 30.4%).

FIGURE 9.

Success rate of the best MM/GBSA model (GBGBn1) based on implicit solvent for all the benchmarks.

It is exciting to observe that MM/GBSA can further improve the performance of distinguishing the near-native binding structures from the decoys based on the ZDOCK_M scores. For the 148 protein–RNA complexes, when εin is set to 1, the success rates of the GBGBn1 model are 61.4% at the top1 level and 79.1% at the top10 level. When εin is set to 2, the success rates of GBGBn1 are 54.7% at the top1 level and 75.6% at the top10 level. However, for relatively high interior dielectric constants (εin = 4 or 8), the reranking capability of MM/GBSA is worse than that of ZDOCK_M, where the success rates at εin = 4 are 45.9% and 70.3% and the success rates at εin = 8 are 43.2% and 65.6%. In conclusion, MM/GBSA based on the GBGBn1 model with εin = 1 achieves the best reranking capability (top1: 61.4% and top10: 79.1%), and can be used for rescoring the binding poses generated by ZDOCK_M.

Performance of MM/PBSA in poses reranking

The reranking capability was also tested for MM/PBSA, and the corresponding ASCs are shown in Figure 10. The best ASC comes from the minimized structures in implicit water with εin = 8, but the ASCs are only 70.08, 70.76, and 73.24 for the Barik, Huang, and Perez benchmarks, respectively. Therefore, MM/PBSA is worse in reranking the docking poses, and this result is consistent with our previous conclusions on protein-small molecule systems and protein–protein systems (Sun et al. 2014b; Chen et al. 2016).

FIGURE 10.

The area under the success rate curves of the MM/PBSA rescoring.

Conclusion

In this study, we examined the capability of MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA in predicting the binding free energies and identifying the correct binding poses for protein–RNA complexes. Our conclusions are as follows:

We evaluated the performance of MM/GBSA and MM/PBSA to predict the binding free energies of 55 protein–RNA complexes. The best predictions come from MM/GBSA calculated by the GBGBn1 model with εin = 8 based on 1 nsec MD trajectories in the TIP3P explicit solvent (rp = −0.578 and rs = −0.568).

As to the binding affinity prediction for protein–RNA complexes, considering the balance of computational cost and prediction accuracy, the computational protocol of simple minimization of binding poses in explicit solvent using the ff14SB force field, and calculating the binding free energies using the GBGBn1 model with εin = 2 yields a satisfactory correlation (rp = −0.557) between the predicted and measured binding affinities, which is better than MM/PBSA (rp = −0.510) and a number of empirical scoring functions used in protein–RNA docking (rp = −0.468).

For identifying the near-native binding structures of protein–RNA complexes, MM/GBSA calculated by the GBGBn1 model with εin = 1 based on minimized structures in implicit solvent can improve the ranking capability of the near-native structures from the decoys given by ZDOCK_M. Taking the success rate of top1 as the criterion, the successful rate for MM/GBSA, 79.1%, is superior to those for ZDOCK_M (72.3%), DARS of NPDock (45.2%), QUASI of NPDock (39.9%), and 3dRPC (30.4%), suggesting that MM/GBSA is a powerful scoring function for protein–RNA docking studies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Benchmark data sets

The benchmark data set (data set I) was collected from PDBbind (http://pdbbind.org.cn/) (Liu et al. 2017), where three criteria were used in searching: (i) Entries must be “Protein-Nucleic Acid Complexes,” (ii) the protein name field must be “Protein,” (iii) the ligand name field must be “RNA.” The search result list contains 67 protein–RNA complexes with crystallographic structures and experimental binding affinities (Kd/Ki/IC50). Generally, the structure of a protein–RNA complex is not suitable for docking if its binding interface is formed by multiple separate chains (Huang and Zou 2014). Specifically, we empirically allowed for no more than two chains in a protein or RNA to ensure the interpretability of results provided by docking or MM/GBSA calculations. Finally, after carefully examining the original experimental data, such as counting the number of chains in the downloaded PDB files and reviewing the experimental binding affinities reported by the original papers, only 55 out of the 67 protein–RNA complexes were used in this study (Supplemental Table S1). Within this data set, the complex of the ribosomal protein tthl1 and 80 nt 23s RNA (PDB entry: 3U4M) has the highest binding affinity (Kd = 2.14 × 10−12 mol/L), and the Nab3 RRM—UCUU complex (PDB entry: 2L41) has the lowest binding affinity (Kd = 7.63 × 10−4 mol/L). The experimental binding affinities cover an extremely broad range of nine orders of magnitude.

The decoy data set (data set II) was obtained from three existing protein–RNA complex benchmarks for the near-native binding structure recognition, including the Barik benchmark (Barik et al. 2012), Huang benchmark (Huang and Zou 2013), and Perez benchmark (Perez-Cano et al. 2012). After carefully checking, such as checking the downloaded PDB files to ensure no duplicates in the benchmark, we have constructed a benchmark of 148 nonredundant protein–RNA complexes, which were used to evaluate the reranking capability of MM/GBSA and MM/PBSA (Supplemental Table S2). The PDB entries of the decoy data set are listed in the Supplemental Material.

The protein–RNA docking and scoring

The protein–RNA rigid docking was accomplished by the modified ZDOCK algorithm (ZDOCK_M) (Iwakiri et al. 2016). By incorporating the partial charges and van der Waals radii of the RNA atoms (derived from the nucleic acid force field) into the scoring function of ZDOCK (Pierce et al. 2014), the electrostatic interaction and shape complementarity score provided by the scoring function of ZDOCK_M are particularly effective in improving the prediction accuracy of ZDOCK. In this study, the angular step size for the rotational sampling of the RNA (docked ligand) was set to 15°, and a total of 3600 decoy structures sorted by the ZDOCK_M scores were generated for each protein–RNA complex. Here, if the root-mean-structure-deviation (RMSD) between the docked RNA and the crystallized RNA is <5 Å, the predicted decoy was defined as a “near-native” structure. It should be noticed that the computational protocol used in this study is designed for the structures whose conformations do not change markedly between bound forms and Apo forms in comparison to the binding free energy.

Moreover, the binding affinities for the 55 complexes in data set I were predicted by three scoring functions, including DARS-RNP (DARS), QUASI-RNP (QUASI), and DECK-RP (DECK), which are the only three complete protocols (include sampling and scoring) specifically developed for protein–RNA docking. According to the framework of the DARS and QUASI scoring functions in NPDock (http://genesilico.pl/NPDock), there are four energy terms, including distance, angular, site-dependent energy terms and a penalty term for steric clashes, in both scoring functions. On the contrary, the DECK scoring function in 3dRPC (http://biophy.hust.edu.cn/3dRPC.html) uses a distance- and environment-dependent, coarse-grained and knowledge-based potential to characterize the RNA–protein interactions. The default parameters were used for the three scoring functions.

Systems preparation and minimization

For each protein–RNA complex in data set I and data set II, the crystal structure was downloaded from the RCSB Protein Data Bank, and MSE residues were converted into MET, HIS residues were converted into HID, HIE, or HIP according to their protonated states, CYS residues involved in disulfide bonds according to PDB files were converted into CYX, small molecules were removed, a “TER” label was added to the location of missing residues in order to satisfy the requirement of the AMBER software (Case et al. 2005). The protonation states of residues were determined using the H++ web server (http://biophysics.cs.vt.edu/).

Each protein–RNA complex was prepared by the tleap module in Amber14. The ff14SB force field was used for the proteins and RNAs (Maier et al. 2015). Each system was immersed in a TIP3P (Price and Brooks 2004) water box with 8 Å out of the solute in each direction. Counterions, Na+ or Cl−, were added to neutralize the unbalanced charges. Following the routine steps of minimization in the AMBER program, each system was then minimized by three steps: First, all the heavy atoms in the backbone of the protein were restrained with an elastic constant of 50 kcal·mol−1·Å−2 (2000 cycles of steepest descent and 3000 cycles of conjugate gradient minimizations); next, the elastic constant was weakened to 10 kcal·mol−1·Å−2 (2000 cycles of steepest descent and 3000 cycles of conjugate gradient minimizations); finally, the whole system was minimized for 5000 steps without any restraint (2000 cycles of steepest descent and 3000 cycles of conjugate gradient minimizations). The cutoff for calculating the short-range interactions (electrostatic and van der Waals interactions) was set to 8 Å, and the particle mesh Ewald (PME) algorithm was used to handle the long-range electrostatic interactions (Darden et al. 1993).

Moreover, in order to investigate the impact of implicit and explicit solvent models on the performance of MM/GBSA and MM/PBSA for protein–RNA systems, each complex was prepared in vacuo and minimized with the modified GB model developed by Onufriev et al. (2000) for 5000 steps without any restraint (2000 cycles of steepest descent and 3000 cycles of conjugate gradient minimizations).

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations

Each system was gradually heated from 0 to 300 K during a period of 50 ps in the NVT ensemble. Then, 1 nsec equilibration simulation was performed in the NTP (T = 300 K and P = 1 atm) ensemble. In the MD simulation process, the SHAKE algorithm was used to constrain all of the covalent bonds involving hydrogen atoms (Ryckaert et al. 1977), and the time step was set to 2 fsec. The snapshots were collected at an interval of 10 psec. Finally, 100 frames were used for the following MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA calculations.

MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA calculations

For each system, the binding free energy was calculated by the MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA approaches based on the final structure derived from the minimization stage or the 100 snapshots extracted from the 1 nsec MD trajectory (Equations 1 to 4).

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

where ΔGbind represents the total binding free energy, and it can be decomposed into three terms: gas-phase interaction energy (ΔEMM), which contains electrostatic (ΔEelectrostatic) and van der Waals (ΔEvdw) interactions, desolvation energy (ΔGsol), which contains polar (ΔGPB/GB) and nonpolar (ΔGSA) parts, and the change of the conformational entropy (−TΔS), which was not considered here due to the high computational cost and low prediction accuracy (Muzzioli et al. 2011; Xu et al. 2012, 2013; Sun et al. 2014b). In the MM/PBSA calculations, the atomic radii optimized by Tan and Luo were used (Tan et al. 2006), where the grid size was set to 0.5 Å. The partial charges of proteins and RNAs used in the PB calculations were taken from the force field parameters. In the MM/GBSA calculations, five GB models were used to estimate the polar part of desolvation (ΔGGB), including the GB model developed by Hawkins and coworkers (GBHCT) (Hawkins et al. 1996), two modified GB models developed by Onufriev and coworkers (referred to as GBOBC1 and GBOBC2) (Onufriev et al. 2000), and two modified GB models developed by Roe and coworkers (referred to as GBGBn1 and GBGBn2) (Roe et al. 2007; Nguyen et al. 2013). In order to evaluate the impact of the dielectric constant on the performance of MM/GBSA and MM/PBSA, four interior dielectric constants, 1, 2, 4 or 8, were used for both the MM/GBSA and MM/PBSA calculations. The nonpolar part of the solvation energy (ΔGSA) was estimated by using the LCPO algorithm: ΔGSA = γΔA + b (Weiser et al. 1999), where γ and b were set to 0.0072 and 0, respectively. In this study, we assumed that the conformational entropies of the subunits did not have remarkable differences in different complex structures for each protein–RNA system.

Estimation methods

For data set I, Pearson correlation coefficient (rp) was used to evaluate the linear correlation between ΔGbind and Kd, and Spearman ranking coefficient (rs) was used to evaluate the capability of MM/GBSA or MM/PBSA to rank Kd (Chen et al. 2016). For data set II, success rate was used to evaluate the reranking efficiency of MM/GBSA, i.e., the proportion of the success case, determined by the number of near-native structures that could be found in the top N predictions (Chen et al. 2016).

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplemental material is available for this article.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2016YFA0501701); National Natural Science Foundation of China (81603031, 81773632, 21575128, 21607126); National Institutes of Health (R01-GM079383, R21-GM097617); and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2017QNA7034, 2017QNA7033).

Footnotes

Article is online at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.065896.118.

REFERENCES

- Allers J, Shamoo Y. 2001. Structure-based analysis of protein-RNA interactions using the program ENTANGLE. J Mol Biol 311: 75–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anko ML, Neugebauer KM. 2012. RNA-protein interactions in vivo: global gets specific. Trends Biochem Sci 37: 255–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahadur RP, Zacharias M, Janin J. 2008. Dissecting protein-RNA recognition sites. Nucleic Acids Res 36: 2705–2716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltz AG, Munschauer M, Schwanhausser B, Vasile A, Murakawa Y, Schueler M, Youngs N, Penfold-Brown D, Drew K, Milek M, et al. 2012. The mRNA-bound proteome and its global occupancy profile on protein-coding transcripts. Mol Cell 46: 674–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barik A, Nithin C, Manasa P, Bahadur RP. 2012. A protein-RNA docking benchmark (I): nonredundant cases. Proteins 80: 1866–1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell ZT, Wickens M. 2015. Probing RNA-protein networks: biochemistry meets genomics. Trends Biochem Sci 40: 157–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case DA, Cheatham TE, Darden T, Gohlke H, Luo R, Merz KM, Onufriev A, Simmerling C, Wang B, Woods RJ. 2005. The Amber biomolecular simulation programs. J Comput Chem 26: 1668–1688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castello A, Fischer B, Eichelbaum K, Horos R, Beckmann BM, Strein C, Davey NE, Humphreys DT, Preiss T, Steinmetz LM, et al. 2012. Insights into RNA biology from an atlas of mammalian mRNA-binding proteins. Cell 149: 1393–1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Kortemme T, Robertson T, Baker D, Varani G. 2004. A new hydrogen-bonding potential for the design of protein-RNA interactions predicts specific contacts and discriminates decoys. Nucleic Acids Res 32: 5147–5162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F, Liu H, Sun HY, Pan PC, Li YY, Li D, Hou TJ. 2016. Assessing the performance of the MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods. 6. Capability to predict protein-protein binding free energies and re-rank binding poses generated by protein-protein docking. Phys Chem Chem Phys 18: 22129–22139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad T, Albrecht AS, Costa VRD, Sauer S, Meierhofer D, Orom UA. 2016. Serial interactome capture of the human cell nucleus. Nat Commun 7: 11212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darden T, York D, Pedersen L. 1993. Particle mesh Ewald: an N•log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J Phys Chem 98: 10089–10092. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson WK, Bujnicki JM. 2016. Computational modeling of RNA 3D structures and interactions. Curr Opin Struct Biol 37: 22–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLano WL. 2002. Unraveling hot spots in binding interfaces: progress and challenges. Curr Opin Struct Biol 12: 14–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez C, Boelens R, Bonvin A. 2003. HADDOCK: a protein-protein docking approach based on biochemical or biophysical information. J Am Chem Soc 125: 1731–1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer JJ, Gittis AG, Karp DA, Lattman EE, Spencer DS, Stites WE, Garcia-Moreno B. 2000. High apparent dielectric constants in the interior of a protein reflect water penetration. Biophys J 79: 1610–1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis JJ, Broom M, Jones S. 2007. Protein-RNA interactions: structural analysis and functional classes. Proteins 66: 903–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y, Dai YZ, Hou MJ, Wang HL, Yao HW, Guo CY, Lin DH, Liao XL. 2017. Structural basis for ribosome protein S1 interaction with RNA in trans-translation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 487: 268–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genheden S, Ryde U. 2015. The MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods to estimate ligand-binding affinities. Expert Opin Drug Discov 10: 449–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glisovic T, Bachorik JL, Yong J, Dreyfuss G. 2008. RNA-binding proteins and post-transcriptional gene regulation. FEBS Lett 582: 1977–1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilhot-Gaudeffroy A, Froidevaux C, Aze J, Bernauer J. 2014. Protein-RNA complexes and efficient automatic docking: expanding RosettaDock possibilities. PLoS One 9: e108928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A, Gribskov M. 2011. The role of RNA sequence and structure in RNA-protein interactions. J Mol Biol 409: 574–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafner M, Landthaler M, Burger L, Khorshid M, Hausser J, Berninger P, Rothballer A, Ascano M, Jungkamp AC, Munschauer M, et al. 2010. Transcriptome-wide identification of RNA-binding protein and microRNA target sites by PAR-CLIP. Cell 141: 129–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins GD, Cramer CJ, Truhlar DG. 1996. Parametrized models of aqueous free energies of solvation based on pairwise descreening of solute atomic charges from a dielectric medium. J Phys Chem 100: 19824–19839. [Google Scholar]

- Hou TJ, Wang JM, Li YY, Wang W. 2011a. Assessing the performance of the MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods: I. The accuracy of binding free energy calculations based on molecular dynamics simulations. J Chem Inf Model 51: 69–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou TJ, Wang JM, Li YY, Wang W. 2011b. Assessing the performance of the molecular mechanics/Poisson Boltzmann surface area and molecular mechanics/generalized Born surface area methods. II. The accuracy of ranking poses generated from docking. J Comput Chem 32: 866–877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang SY, Zou XQ. 2013. A nonredundant structure dataset for benchmarking protein-RNA computational docking. J Comput Chem 34: 311–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang SY, Zou XQ. 2014. A knowledge-based scoring function for protein-RNA interactions derived from a statistical mechanics-based iterative method. Nucleic Acids Res 42: e55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YY, Liu SY, Guo DC, Li L, Xiao Y. 2013. A novel protocol for three-dimensional structure prediction of RNA-protein complexes. Sci Rep 3: 1887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwakiri J, Tateishi H, Chakraborty A, Patil P, Kenmochi N. 2012. Dissecting the protein-RNA interface: the role of protein surface shapes and RNA secondary structures in protein-RNA recognition. Nucleic Acids Res 40: 3299–3306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwakiri J, Kameda T, Asai K, Hamada M. 2013. Analysis of base-pairing probabilities of RNA molecules involved in protein-RNA interactions. Bioinformatics 29: 2524–2528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwakiri J, Hamada M, Asai K, Kameda T. 2016. Improved accuracy in RNA-protein rigid body docking by incorporating force field for molecular dynamics simulation into the scoring function. J Chem Theory Comput 12: 4688–4697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashyap M, Ganguly AK, Bhavesh NS. 2015. Structural delineation of stem-loop RNA binding by human TAF15 protein. Sci Rep 5: 17298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastritis PL, Bonvin A. 2013. On the binding affinity of macromolecular interactions: daring to ask why proteins interact. J R Soc Interface 10: 20120835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katchalskikatzir E, Shariv I, Eisenstein M, Friesem AA, Aflalo C, Vakser IA. 1992. Molecular-surface recognition: determination of geometric fit between proteins and their ligands by correlation techniques. Proc Natl Acad Sci 89: 2195–2199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo J, Westhof E. 2011. Classification of pseudo pairs between nucleotide bases and amino acids by analysis of nucleotide-protein complexes. Nucleic Acids Res 39: 8628–8637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konig J, Zarnack K, Rot G, Curk T, Kayikci M, Zupan B, Turner DJ, Luscombe NM, Ule J. 2010. iCLIP reveals the function of hnRNP particles in splicing at individual nucleotide resolution. Nat Struct Mol Biol 17: 909–915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntz ID, Blaney JM, Oatley SJ, Langridge R, Ferrin TE. 1982. A geometric approach to macromolecule-ligand interactions. J Mol Biol 161: 269–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapointe CP, Wilinski D, Saunders HAJ, Wickens M. 2015. Protein-RNA networks revealed through covalent RNA marks. Nat Methods 12: 1163–1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li CH, Cao LB, Su JG, Yang YX, Wang CX. 2012. A new residue-nucleotide propensity potential with structural information considered for discriminating protein-RNA docking decoys. Proteins 80: 14–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li HT, Huang YY, Xiao Y. 2017. A pair-conformation-dependent scoring function for evaluating 3D RNA-protein complex structures. PLoS One 12: e0174662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licatalosi DD, Mele A, Fak JJ, Ule J, Kayikci M, Chi SW, Clark TA, Schweitzer AC, Blume JE, Wang XN, et al. 2008. HITS-CLIP yields genome-wide insights into brain alternative RNA processing. Nature 456: 464–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu ZH, Su MY, Han L, Liu J, Yang QF, Li Y, Wang RX. 2017. Forging the basis for developing protein-ligand interaction scoring functions. Acc Chem Res 50: 302–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukong KE, Chang KW, Khandjian EW, Richard S. 2008. RNA-binding proteins in human genetic disease. Trends Genet 24: 416–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier JA, Martinez C, Kasavajhala K, Wickstrom L, Hauser KE, Simmerling C. 2015. ff14SB: improving the accuracy of protein side chain and backbone parameters from ff99SB. J Chem Theory Comput 11: 3696–3713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon AC, Rahman R, Jin H, Shen JL, Fieldsend A, Luo WF, Rosbash M. 2016. TRIBE: hijacking an RNA-editing enzyme to identify cell-specific targets of RNA-binding proteins. Cell 165: 742–753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzzioli E, Del Rio A, Rastelli G. 2011. Assessing protein kinase selectivity with molecular dynamics and MM-PBSA binding free energy calculations. Chem Biol Drug Des 78: 252–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen H, Roe DR, Simmerling C. 2013. Improved generalized Born solvent model parameters for protein simulations. J Chem Theory Comput 9: 2020–2034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onufriev A, Bashford D, Case DA. 2000. Modification of the generalized Born model suitable for macromolecules. J Phys Chem B 104: 3712–3720. [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Cano L, Solernou A, Pons C, Fernandez-Recio J. 2010. Structural prediction of protein-RNA interaction by computational docking with propensity-based statistical potentials. Pac Symp Biocomput : 293–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Cano L, Jimenez-Garcia B, Fernandez-Recio J. 2012. A protein-RNA docking benchmark (II): extended set from experimental and homology modeling data. Proteins 80: 1872–1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Cano L, Romero-Durana M, Fernandez-Recio J. 2017. Structural and energy determinants in protein-RNA docking. Methods 118: 163–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce BG, Wiehe K, Hwang H, Kim BH, Vreven T, Weng ZP. 2014. ZDOCK server: interactive docking prediction of protein-protein complexes and symmetric multimers. Bioinformatics 30: 1771–1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price DJ, Brooks CL III. 2004. A modified TIP3P water potential for simulation with Ewald summation. J Chem Phys 121: 10096–10103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puton T, Kozlowski L, Tuszynska I, Rother K, Bujnicki JM. 2012. Computational methods for prediction of protein-RNA interactions. J Struct Biol 179: 261–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray D, Kazan H, Cook KB, Weirauch MT, Najafabadi HS, Li X, Gueroussov S, Albu M, Zheng H, Yang A, et al. 2013. A compendium of RNA-binding motifs for decoding gene regulation. Nature 499: 172–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roe DR, Okur A, Wickstrom L, Hornak V, Simmerling C. 2007. Secondary structure bias in generalized Born solvent models: comparison of conformational ensembles and free energy of solvent polarization from explicit and implicit solvation. J Phys Chem B 111: 1846–1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryckaert JP, Ciccotti G, Berendsen HJ. 1977. Numerical integration of the cartesian equations of motion of a system with constraints: molecular dynamics of n-alkanes. J Comput Phys 23: 327–341. [Google Scholar]

- Setny P, Zacharias M. 2011. A coarse-grained force field for protein-RNA docking. Nucleic Acids Res 39: 9118–9129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Si JN, Cui J, Cheng J, Wu RL. 2015. Computational prediction of RNA-binding proteins and binding sites. Int J Mol Sci 16: 26303–26317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun HY, Li YY, Shen MY, Tian S, Xu L, Pan PC, Guan Y, Hou TJ. 2014a. Assessing the performance of MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods. 5. Improved docking performance using high solute dielectric constant MM/GBSA and MM/PBSA rescoring. Phys Chem Chem Phys 16: 22035–22045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun HY, Li YY, Tian S, Xu L, Hou TJ. 2014b. Assessing the performance of MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods. 4. Accuracies of MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methodologies evaluated by various simulation protocols using PDBbind data set. Phys Chem Chem Phys 16: 16719–16729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan CH, Yang LJ, Luo R. 2006. How well does Poisson-Boltzmann implicit solvent agree with explicit solvent? A quantitative analysis. J Phys Chem B 110: 18680–18687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JS, Burnett RM. 2000. DARWIN: a program for docking flexible molecules. Proteins 41: 173–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuszynska I, Bujnicki JM. 2011. DARS-RNP and QUASI-RNP: new statistical potentials for protein-RNA docking. BMC Bioinformatics 12: 348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuszynska I, Matelska D, Magnus M, Chojnowski G, Kasprzak JM, Kozlowski LP, Dunin-Horkawicz S, Bujnicki JM. 2014. Computational modeling of protein-RNA complex structures. Methods 65: 310–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuszynska I, Magnus M, Jonak K, Dawson W, Bujnicki JM. 2015. NPDock: a web server for protein-nucleic acid docking. Nucleic Acids Res 43: W425–W430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ule J, Jensen KB, Ruggiu M, Mele A, Ule A, Darnell RB. 2003. CLIP identifies Nova-regulated RNA networks in the brain. Science 302: 1212–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vakser IA, Aflalo C. 1994. Hydrophobic docking: a proposed enhancement to molecular recognition techniques. Proteins 20: 320–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walia RR, Caragea C, Lewis BA, Towfic F, Terribilini M, El-Manzalawy Y, Dobbs D, Honavar V. 2012. Protein-RNA interface residue prediction using machine learning: an assessment of the state of the art. BMC Bioinformatics 13: 89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ET, Cody NAL, Jog S, Biancolella M, Wang TT, Treacy DJ, Luo SJ, Schroth GP, Housman DE, Reddy S, et al. 2012. Transcriptome-wide regulation of pre-mRNA splicing and mRNA localization by muscleblind proteins. Cell 150: 710–724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiser J, Shenkin PS, Still WC. 1999. Approximate atomic surfaces from linear combinations of pairwise overlaps (LCPO). J Comput Chem 20: 217–230. [Google Scholar]

- Xu L, Li YY, Li L, Zhou SY, Hou TJ. 2012. Understanding microscopic binding of macrophage migration inhibitory factor with phenolic hydrazones by molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulations and free energy calculations. Mol Biosyst 8: 2260–2273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L, Sun HY, Li YY, Wang JM, Hou TJ. 2013. Assessing the performance of MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods. 3. The impact of force fields and ligand charge models. J Phys Chem B 117: 8408–8421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Lu L, Zhang Y, Li CH, Wang CX, Zhang XY, Tan JJ. 2017. A combinatorial scoring function for protein-RNA docking. Proteins 85: 741–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng S, Robertson TA, Varani G. 2007. A knowledge-based potential function predicts the specificity and relative binding energy of RNA-binding proteins. FEBS J 274: 6378–6391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.