Abstract

Novel fluorinated 2-amino-4-oxo-6-substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine analogues 7–12 were synthesized and tested for selective cellular uptake by folate receptors (FRs) α and β or the proton-coupled folate transporter (PCFT) and for antitumor efficacy. Compounds 8, 9, 11, and 12 showed increased in vitro antiproliferative activities (~11-fold) over the nonfluorinated analogues 2, 3, 5, and 6 toward engineered Chinese hamster ovary and HeLa cells expressing FRs or PCFT. Compounds 8, 9, 11, and 12 also inhibited proliferation of IGROV1 and A2780 epithelial ovarian cancer cells; in IGROV1 cells with knockdown of FRα, 9, 11, and 12 showed sustained inhibition associated with uptake by PCFT. All compounds inhibited glycinamide ribonucleotide formyltransferase, a key enzyme in the de novo purine biosynthesis pathway. Molecular modeling studies validated in vitro cell-based results. NMR evidence supports the presence of an intramolecular fluorine−hydrogen bond. Potent in vivo efficacy of 11 was established with IGROV1 xenografts in severe compromised immunodeficient mice.

INTRODUCTION

Several successful clinically useful cancer chemotherapy agents target folate and nucleotide metabolism, demonstrating the importance of these one-carbon metabolism pathways to the malignant phenotype. Pemetrexed (PMX) and methotrexate (MTX) are successful agents used in treating hematologic malignancies and solid tumors.1 Although clinical responses to therapy are notable, drawbacks include severe toxicities and drug resistance, resulting in treatment failure. The causes of drug toxicity are complex but invariably reflect a lack of selectivity for tumors over normal cells.

The reduced folate carrier (RFC) is one of three principal transporters for cellular uptake of folate cofactors and classical antifolates into mammalian cells,2 the others being the proton-coupled folate transporter (PCFT)3,4 and folate receptors (FRs) α and β.5 While RFC is the major mechanism for cellular uptake of MTX and PMX and is an important determinant of clinical antitumor efficacy of these agents, RFC does not provide for tumor-selective uptake of cytotoxic folate-based analogues, as RFC is abundantly expressed in normal tissues, as well as tumors.2

FRα is expressed in a subset of normal tissues including kidney, choroid plexus, and placenta.5–10 FRα is overexpressed in several malignancies, including epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) and non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and in renal, endometrial, colorectal, and certain breast cancers.5–11 Whereas in normal tissues, FRα is localized to the luminal surface without exposure to systemic circulation,5 in tumors FRα is accessible to the circulation.12 These characteristics of FRα provide compelling rationale for developing FR-selective therapeutics for tumors.12–14 FRβ is expressed in hematologic malignancies such as acute myeloid leukemia5 and is also expressed in placenta and white blood cells of the myeloid lineage, including tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs).15 In addition to directly targeting FRβ-expressing leukemias,12 FRβ-positive TAMs may play an important role in the tumor microenvironment in relation to tumor metastasis and angiogenesis by releasing proangiogenic factors, including vascular endothelial growth factor and matrix metalloproteinase.16 Accordingly, TAMs may constitute an additional potential therapeutic target in assorted cancers for FRβ-targeted agents.15

PCFT is a proton symporter that is modestly expressed in most normal tissues other than the duodenum and jejunum where it is highly expressed and mediates dietary folate absorption.17 PCFT is also expressed in the liver and kidney.3,4,18 PCFT is expressed in human tumors with particularly high levels in NSCLC,19 EOC,11 and malignant pleural mesothelioma.20 PCFT functions in the cellular uptake of folates and antifolates at acidic pHs characterizing the microenvironments of many solid tumors.3,21

Progress has been made in developing tumor-targeted therapies, based on selective targeting FRs or PCFT over RFC. Examples of FR-targeted therapies tested in clinical trials include the monoclonal antibody farletuzumab (Morphotech),22 the FR-targeted antibody−drug conjugate IMGN853 (ImmunoGen),23 and cytotoxic folic acid drug conjugates including vintafolide (EC145), EC1456, and EC1788 (Endocyte).13,14,24 In 2016, IMN853 was granted orphan drug designation by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for ovarian cancer.

We previously described novel 6-substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine benzoyl L-glutamate antifolates 2 and 3 (Figure 1) as preferred transport substrates for PCFT and FRα over RFC and as inhibitors of de novo purine nucleotide biosynthesis at glycinamide ribonucleotide (GAR) formyltransferase (GARFTase).25,26 Replacements of the side-chain phenyl group with a thiophene resulted in novel compounds 5 and 6, respectively,27,28 while replacement of the phenyl moiety of 2 by a pyridine resulted in compound 429 (Figure 1). Compounds 4–6, like 2 and 3,25,26 are all selective for PCFT and FR cellular uptake over RFC and inhibited GARFTase, resulting in cytotoxicity and inhibition of tumor cell proliferation.27–29

Figure 1.

6-Substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine analogues. Structures are shown for previously studied 6-substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine compounds (2–6)25,27–29 and their corresponding fluorinated analogues (7–12) and compound 1.30

Introduction of fluorine atoms into bioactive molecules is a well-established strategy for modifying the biological properties of drugs, as exemplified by the growing percentage of FDA-approved fluorinated drugs (from 20% in 2010 to about 30% currently).31,32 The superior target affinity and ADME profile upon fluorine introduction in a lead molecule is a consequence of its direct (amphiphatic character, resulting in polar and hydrophobic interactions) or indirect (metabolism, lipophilicity, changes in acidity and basicity, etc.) effects.33–39 For example, Pendergast et al.40 observed that a 2′-fluoro substitution of a benzo[f ]quinazoline antifolate increased antitumor activity, which was attributed to the conformational restriction of the side-chain L-glutamate via a fluorine−hydrogen bond.41

It has been our long-standing goal to provide potent folate-based inhibitors as targeted antitumor agents with selectivity for FRs and PCFT over RFC. In the current investigation, we extended our systematic structure–activity relationship (SAR) study of tumor-targeted antifolates by strategically introducing a fluorine into the side-chain (hetero)aromatic ring of our previously reported analogues. Particular focus was on 2′ and 3′ fluorinated analogues (7–12) of parent 6-substituted pyrrolo-[2,3-d]pyrimidine compounds with 3 (3, 6) or 4 (2, 4, 5) carbon bridge lengths and side-chain phenyl (2, 3), pyridyl (4), or thienyl (5, 6) moieties (Figure 1). Among the new analogues reported in this study, 11, the 3′-fluorine-substituted analogue of 5 has emerged as a promising compound with unusually high potency and specificity for PCFT and FR over RFC, resulting in antitumor efficacy in vivo.

CHEMISTRY

Commercially available aromatic acids 13a–d (Scheme 1) were peptide-coupled with L-glutamate diethyl ester using N-methyl morpholine (NMM) and 2,4-dimethoxy-6-chloro-triazine (CDMT) as the coupling reagents to afford the glutamylated, (hetero)aromatic bromides 14a–d, respectively. Bromides 14a–d were then Sonogashira coupled with the intermediate alkyne 1542 under microwave heating to afford the 2-amino-4-oxo-6-substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine alkynes 16a–d. Palladium-catalyzed reduction of the alkynes 16a–d, and subsequent saponification of the L-glutamate esters afforded target compounds 7, 8, 10, and 11, respectively.

Scheme 1.

Reagents and conditions: (a) NMM, 2,4-dimethoxy-6-chloro-triazine, diethyl-L-glutamate, DMF, rt, 12 h, 63–84%; (b) Cul, Pd(0), TEA, DMF, 70 °C, μW, 12 h, 42–59%; (c) (i) 10% Pd/C, H2 12 h; (ii) 1 N NaOH, rt, 1 h, 55–72%.

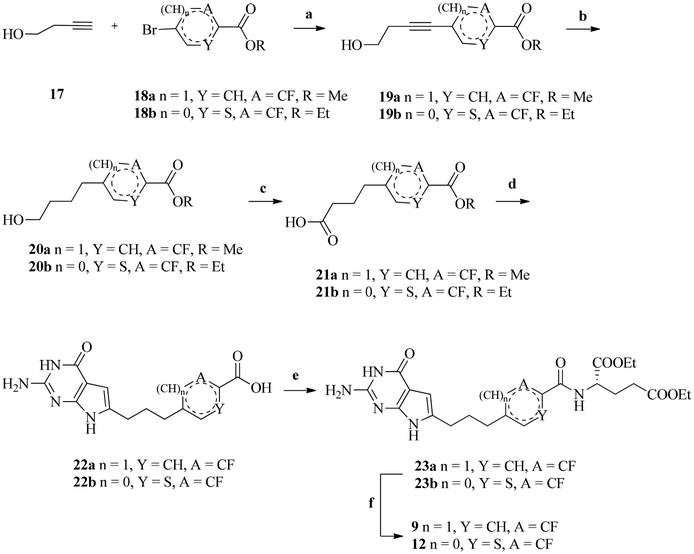

The alkyne-coupled aromatic esters 19a,b (Scheme 2) were synthesized by Sonogashira coupling of commercially available butyn-1-ol 17 with the appropriate bromides 18a,b. Catalytic hydrogenation of 19a,b reduced the alkynes to afford their respective saturated alkanes 20a,b.

Scheme 2.

Reagents and conditions, (a) PdCl2, Ph3P, TEA, CuI, ACN, μW, 100 °C, 30 min, 65–66%; (b) H2, Pd/C, 10%, quant; (c) H5IO6, PCC, ACN, 0 °C to rt, 3–12 h, 80–96%; (d) (i) (COCl)2, DCM, reflux, 1 h; (ii) CH2N2, (Et)2O, 0 °C to rt, 1 h; (iii) 48% HBr, (Et)2O, 50 °C, 2 h; (iv) 2,6-diaminopyrimidin-4(3H)-one, DMF, rt, 3 days; (v) IN, NaOH, rt, 12 h, 14–15%; (e) NMM, CDMT, diethyl-L-glutamate, DMF, rt, 12 h, 28–50%; (f) IN, NaOH, rt, 1 h, 75–88%.

Subsequent oxidation of the alcohols 20a,b using periodic acid and PCC gave acids 21a,b. The terminal aliphatic carboxylic acids 21a,b were activated to acid chlorides and immediately reacted with diazomethane (in situ generated), followed by 48% HBr in water, to give the terminal α-bromomethylketones.28 The α-bromomethylketones were immediately condensed with 2,6-diamino-3H-pyrimidin-4-one in DMF at room temperature for 3 days and hydrolyzed to afford the 2-amino-4-oxo-6-substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]-pyrimidine scaffold-containing pteroic acids 22a,b. Subsequent peptide coupling of 22a and 22b with L-glutamate diethyl ester, using NMM and CDMT as the coupling reagents, afforded the precursor diester intermediates 23a and 23b. Saponification of 23a and 23b gave the respective target compounds 9 and 12.

BIOLOGICAL EVALUATION AND DISCUSSION

Antiproliferative Effects of Fluorinated 6-Substituted Pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine Analogues in Relation to Mechanisms of Folate Transport.

In this study, our goal was to explore the antiproliferative and cytotoxic effects of novel fluorinated 6-substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine anti-folates (Figure 1) toward tumor cells including EOCs and to establish whether fluorine substitutions in previously characterized analogues of this series could enhance targeted inhibitory activities or specificities for FRs and PCFT compared to RFC.

To gauge the selectivity of each compound toward the various human folate transporters (RFC, PCFT, FRα and β), we utilized isogenic Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) sublines that were engineered to individually express human RFC (PC43–10), PCFT (R2/PCFT4), FRα (RT16), or FRβ (D4), all derived from a transporter-null CHO cell line MTXRIIOuaR2–4 (R2)25,43–46 For these experiments, the cells were continuously treated with the novel 6-substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine analogues, and proliferation was measured after 4 days with a fluorescence-based assay. IC50 values (corresponding to the drug concentration that resulted in 50% inhibition) were determined, and results for the novel fluorinated antifolates were directly compared to those for the corresponding nonfluorinated analogues (see groups a, b, c, d, and e in Table 1).

Table 1.

Cell Proliferation Assays with 6-Substituted Pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine Analoguesa

| CHO (IC50, nM) | HeLa (IC50, nM) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RFC | FRα | FRβ | PCFT | RFC | PCFT | FRα | ||||

| group | antifolate | 2′/3′-F | PC43–10 | R2 | RT16 | D4 | R2/PCFT4 | R1–11-RFC2 | R1–11-PCFT4 | R1–11-FR2 |

| − | 1 | − | 106(17) | 249(25) | 0.31(0.15) | 0.16(0.02) | 3.3(0.5) | 444(5) | 53.1(15.5) | 30.2(5.6) |

| a | 2 | − | >1000 | >1000 | 6.3(1.6) | 6.3(1.6) | 213(28) | >1000 | 5.21(1.33) | 11.6(2.7) |

| a | 8 | + | >1000 | >1000 | 0.58(0.12) | 1.6(0.44) | 23(2) | >1000 | 4.57(1.48) | 7.78(1.89) |

| b | 3 | − | 304(89) | >1000 | 4.1(1.6) | 5.6(1.2) | 23.0(3.3) | >1000 | 9.71(2.78) | 12.2(4.4) |

| b | 9 | + | 62(12)* | 140(27)* | 1.12(0.37)* | 3.87(0.14)* | 3.82(0.27)* | 507(76) | 5.54(3.35) | 5.22(1.32) |

| c | 4 | − | >1000 | >1000 | 1.3(0.1) | 0.51(0.09) | 30.4 (10.7) | 634(43.9) | 8.98(3.64) | 6.54(1.29) |

| c | 10 | + | 468(142) | >1000 | 0.69(0.39) | 0.44(0.13) | 67(25) | >1000 | 21.57(4.54)* | 21.7(3.9)* |

| d | 5 | − | >1000 | >1000 | 2.5(0.5) | 0.43(0.14) | 41.5(3.1) | >1000 | 72.6(18.1) | 35.3(6.2) |

| d | 11 | + | >1000 | >1000 | 0.36(0.13) | 0.75(0.42) | 6.00(0.94)* | 213(9) | 5.01(2.12)* | 2.84(0.67)* |

| e | 6 | − | 197(49) | 355(10) | 0.33(0.15) | 0.34(0.03) | 5.4(1.3) | 62.9(3.8) | 40.0(9.8) | 7.57(1.16) |

| e | 12 | + | 20.1(6.2)* | 20.5(1.6)* | 0.14(0.03)* | 0.19(0.02) | 1.5(0.4)* | 66.2(6.2) | 20.4(4.7)* | 3.11(0.69)* |

| − | PMX | − | 26.2(5.5) | 138(13) | 42(9) | 60(8) | 8.3(2.7) | 23.8(1.5) | 66.8(4.8) | 863(81) |

Growth inhibition assays were performed using CHO sublines derived from RFC-, PCFT-, and FR-null MTXRIIOuaR2–4 CHO cells (R2) engineered to express human RFC (PC43–10), PCFT (R2/hPCFT4), FRα (RT16), or FRβ (D4).25,43–46 Additional experiments were performed with isogenic HeLa sublines derived from RFC-, PCFT-, and FR-null R1–11 HeLa cells, expressing RFC (R1–11RFC2), PCFT (R1–11PCFT4), or FRα (R1–11FR2).28,47,48 For all experiments, folate-free RPMI 1640 with 10% dialyzed FBS and antibiotics was used including 2 nM LCV (RT16 and D4 CHO) or 25 nM LCV (R2, PC43–10, and R2/PCFT4 CHO; R1–11RFC2, R1–11PCFT4, R1–11FR2 HeLa). Results are shown as mean values from three to five experiments (± standard errors in parentheses) and are presented as calculated IC50 values representing the concentrations at which growth of 50% of cells was inhibited relative to untreated cells. IC50 values of fluorinated compounds that are statistically different from the corresponding non-fluorinated compounds within each cell line are marked with * (p < 0.05). Groups a, b, c, etc. designated paired structural homologs differing by virtue of the absence or presence of a 2′ or 3′ fluorine.

There are varying degrees of predictability associated with fluorine substitutions in bioactive molecules, often necessitating “fluorine scanning” approaches for discovering optimized fluorine-substituted drugs. For the present study, initially, compound 2 was substituted with a fluorine on either the 3′ position [meta (m-) to the L-glutamate] (7) or 2′ position [ortho (o-) to the L-glutamate] (8) (Figure 2). Compound 7 increased growth inhibition compared to the parent desfluoro 2 toward CHO cells expressing FRα (IC50 1.4 ± 0.15 nM versus 6.3 ± 1.6 nM, respectively, with RT16 cells) and FRβ (IC50 0.93 ±0.02 nM versus 5.6 ± 1.2 nM, respectively, for D4 cells) but had no impact on PCFT-targeting (IC50 207 ± 30 nM and 213 ± 28 nM, respectively, with R2/PCFT4 cells). In contrast, the 2′-fluoro substitution in 8 dramatically increased anti-proliferative activity mediated through all 3 transporters, with the largest impact (11- and 9-fold, respectively) on the FRα-and PCFT-expressing CHO cell lines (Table 1). These results indicate that not only does fluorine substitution influence the activity but its regioisomeric position dictates the improvement or loss of activity. As dual PCFT- and FR-targeting provides the greatest utility of our targeted analogues,11,21 these results prompted further systematic studies into the impact of o-fluoro substitutions on the growth inhibitory activities of our leading 6-substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine compounds toward FR-and PCFT-expressing cells.

Figure 2.

6-Substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine antifolates. Compound 2 and its 3′- and 2′-fluorinated analogues 7 and 8, respectively.

Based on results with 2 and 8, we focused on fluorine substitutions ortho to the L-glutamate, that is, the 2′ (benzoyl)-and 3′ (thienoyl)-fluoro-substituted analogues of compounds 3–6 (9–12, respectively) (Figure 1).25,27–29 Both the fluorinated and nonfluorinated analogues inhibited proliferation of FR- and PCFT-expressing CHO cells (as reflected in IC50 values); antiproliferative activities were substantially reduced toward the RFC-expressing PC43–10 and transporter-null R2 cells (Table 1). Toward FR- and PCFT-expressing cells, relative inhibitions were notably increased for the fluorinated over the nonfluorinated homologues, with the largest increases (reduced IC50 values) for 8/2 (11-fold) and 11/5 (7-fold) for FRα-expressing RT16 cells and 8/2 (9-fold), 9/3 (6-fold), and 11/5 (7-fold) for PCFT-expressing R2/PCFT4 cells. For R2/PCFT4 cells, IC50 values for these fluorinated analogues approximated that for compound 1, a 6-substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine thienoyl antifolate and the most potent PCFT-targeted compound yet described.30 In other cases, differences were more subtle. For certain analogues (3 and 6), the modest growth inhibitions previously reported for RFC-expressing PC43–10 cells25,27 were increased (~5- and ~10-fold, respectively) for their fluorinated counterparts (9 and 12) (Table 1), although still less than for the FR- and PCFT-expressing CHO sublines. As these inhibitions extended to R2 cells, they must reflect a nonmediated uptake component.

We performed additional proliferation assays in engineered HeLa cells developed from a RFC-, PCFT-, and FR-null R1–11 HeLa cell line,44 including R1–11-RFC2 (expresses RFC), R1–11-PCFT4 (expresses PCFT), and R1–11-FR2 (expresses FRα) cell lines.28,47,48 Although there were some quantitative differences from the results with the engineered CHO cells, drug sensitivity patterns in the CHO cells were generally preserved for the HeLa sublines, with all the pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine analogues showing substantially increased activities (decreased IC50 values) toward PCFT- and FR-expressing cells over RFC-expressing cells. The fluorinated compounds 11 and 12 again showed significantly increased inhibitions of R1–11-PCFT4 cells over nonfluorinated 5 and 6, respectively, whereas 10 showed decreased inhibition toward R1–11-PCFT4 cells over compound 4, paralleling results in the R2/PCFT4 CHO cells (Table 1). With FRα-expressing R1–11-FR2 HeLa cells, 12 inhibited proliferation with a statistically significant ~2–3-fold reduced IC50 from that for its nonfluorinated counterpart 6, similar to the RT16 CHO cells. A dramatic ~11-fold decreased IC50 was measured for 11 over 5 in R1–11-FR2 HeLa cells, paralleling the impact of fluorination in 11 in the FRα-expressing RT16 CHO subline.

Again, both compounds 9 and 11 showed IC50 values for R1–11-PCFT and R1–11-FR2 cells well below those for compound 1 (10-fold for both compounds with R1–11-PCFT and 6- and 15-fold, respectively, for R1–11-FR2). Drug selectivities for PCFT and FRα versus RFC (defined as IC50 R1–11-RFC2/IC50 R1–11-PCFT and IC50 R1–11-RFC2/IC50 R1–11-FR2, respectively) were calculated as ~92 for 9 and ~43 for 11 versus ~8 for 1 for PCFT and as ~97 for 9 and ~75 for 11 versus ~15 for 1 for FRα. Interestingly, the transport selectivity ratio for 12, the 3-carbon bridge analogue of 11, was only ~3 for PCFT over RFC and ~21 for FRα over RFC. With PMX, a 5-substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine compound and an excellent substrate for both PCFT and RFC with modest FR activity,18 the PCFT/RFC selectivity was 0.36, and FRα/RFC selectivity was 0.027. This indicates a total lack of PMX selectivity for cells expressing PCFT and FRα over RFC-expressing cells.

Transport Specificities of 6-Substituted Pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine Analogues for the Major Folate Transporters.

The in vitro drug efficacies for the isogenic CHO and HeLa sublines (Table 1) directly reflect differences in transport specificities for the major folate transporters. To further explore the transport specificities of the fluorinated pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine series versus their nonfluorinated counterparts (Figure 1), we assessed relative binding affinities of the individual compounds for PCFT and FRs versus RFC.

For PCFT, we initially tested the capacities of the novel analogues at 1 and 10 μM to inhibit uptake of [3H]MTX (0.5 μM) in PCFT-expressng R2/PCFT4 CHO cells at pH 5.5 and pH 6.8 (compared to untreated control R2/PCFT4 and to PCFT-null R2 cells). Results for the 6-substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine analogues were compared to those for PMX, an excellent PCFT substrate49 (positive control), and for PT523, a RFC-specific substrate without PCFT substrate activity42 (negative control). At pH 5.5 (Figure 3A), all the fluorinated compounds were inhibitory at 1 μM (~60% to ~85% inhibition) and 10 μM (~90% to ~95% inhibition), with the fluorinated compounds showing slightly increased (8, 9, 11, 12) or decreased (10) inhibitions over the corresponding nonfluorinated analogues (most obvious at 1 μM competitor). These patterns were further reflected as differences (2–4-fold) in Ki values for PCFT between the fluorinated and non-fluorinated compounds, measured at pH 5.5 over a range of inhibitor concentrations (0.05 μM to 0.5 μM) with constant (0.5 μM) [3H]MTX (Table 2). Analogous albeit less pronounced inhibitions were seen at pH 6.8 (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

PCFT transport inhibition by the fluorinated and nonfluorinated 6-substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine analogues. Inhibition of PCFT [3H]MTX transport by nonradioactive 6-substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine analogues in R2/PCFT4 CHO cells at pH 5.5 (A) and pH 6.8 (B). Transport activities were measured as described in Experimental Methods over 2 min in the presence of [3H]MTX (0.5 μM), with 1 or 10 μM of inhibitor or without additions. Results are presented as mean values ± standard errors for three experiments. Results are normalized to transport measured in the absence of any additions. The fluorinated and nonfluorinated paired analogues are noted by brackets. Results noted with asterisks were statistically different from those for the corresponding nonfluorinated analogue (Figure 1, Table 1) at the same inhibitor concentration (p <0.05) by paired t test analysis.

Table 2.

Kinetic Inhibition Analysis of 6-Substituted Pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine Analogues Compared to PMX in R2/PCFT4 Cellsa

| substrate | 2′/3′-F | Ki |

|---|---|---|

| PMX | − | 0.12(0.03) |

| 1 | − | 0.14(0.02) |

| 2 | − | 0.46(0.05) |

| 8 | + | 0.17(0.01)* |

| 3 | − | 0.63(0.13) |

| 9 | + | 0.26(0.01)* |

| 4 | − | 0.24(0.02) |

| 10 | + | 0.46(0.06)* |

| 5 | − | 0.36(0.03) |

| 11 | + | 0.25(0.01)* |

| 6 | − | 0.28(0.07) |

| 12 | + | 0.07(0.04)* |

[3H]MTX uptake was assayed at using R2/PCFT4 cells at pH 5.5 over 2 min at 37 °C. To determine Ki values, cells were incubated with 0.5 μM [3H]MTX with pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine antifolates as competitors from 0.05 to 0.5 μM, with results analyzed by Dixon plots. Data are presented as mean values ± standard errors (in parentheses) from four independent experiments. For the fluorinated antifolates (8–12), values significantly different from those of the corresponding non-fluorinated antifolates (2–6, respectively) are marked with * (p < 0.05).

Analogous experiments were performed in RFC-expressing R1–11-RFC2 and transporter-null R1–11 HeLa cells incubated with [3H]MTX (at 0.5 μM) at pH 7.2, in the presence of 1 or 10 μM inhibitor (Supplementary data, Figure 1S). Inhibition of RFC-transport was insignificant for both fluorinated and nonfluorinated compounds, although minor (less than 30%) inhibition was detected at 10 μM of 6 and 12. Thus, binding to RFC, as reflected in the inhibition of [3H]MTX uptake at neutral pH, parallels the results from the cell proliferation experiments (Table 1).

Collectively, these results suggest that both the fluorinated and nonfluorinated 6-substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine analogues (Figure 1) bind avidly and selectively to PCFT over RFC, as predicted from the findings of the cell outgrowth experiments in Table 1. Fluorination significantly increased binding to PCFT for several series. Notably, the fluorinated compound (12) with the most potent inhibition of PCFT-expressing R2/PCFT4 CHO cells also has the lowest Ki value for PCFT; however, differences in relative PCFT affinities were only partly (e.g., 10/3, 11/5, 12/6) reflected in differences in inhibition of cell proliferation (Table 1), likely due to multiple factors that contribute to drug efficacy.

We also measured binding of the fluorinated and non-fluorinated pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidines to FRα and FRβ in engineered CHO cells (RT16 and D4, respectively) by direct competition for binding with 50 nM [3H]folic acid over a range (10–1000 nM) of inhibitor concentrations25,27,28,30,42,45,50,51 (Figure 4). IC50 values were normalized to that for folic acid, and results were compared to MTX as a negative control. Relative binding affinities were calculated as the inverse molar ratios of unlabeled ligands required to inhibit [3H]folic acid binding by 50%, where the value of folic acid is assigned a value of 1. There was a range of calculated binding affinities between analogues, with significant differences between structurally analogous fluorinated and nonfluorinated compounds (e.g., 8/2, 10/4, 11/5 and 12/6) (Figure 4). These differences generally paralleled relative IC50 values for the FRα-expressing CHO or HeLa sublines with 10/4, 11/5, and 12/6 (Table 1).

Figure 4.

FRα and FRβ binding affinities. Binding of the 6-substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine analogues to FRα in RT16 cells (A) and FRβ in D4 cells (B) relative to folic acid (FA). Relative binding affinities for assorted folate/antifolate substrates were determined over a range of ligand concentrations from 0 to 1000 nM and were calculated as the inverse molar ratios of unlabeled compounds required to inhibit [3H]folic acid binding by 50% (the relative affinity of folic acid was assigned a value of 1). Results are presented as mean values ± standard errors from 3 experiments. The fluorinated and non-fluorinated paired analogues are noted by brackets. The results noted with asterisks were statistically different from those for the corresponding nonfluorinated parent compound (Figure 1 and Table 1) (p < 0.05) by paired t test analysis.

Antitumor Efficacies of 6-Substituted Pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine Compounds toward EOC Cell Lines.

We extended our growth inhibition studies of the novel fluorinated pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine compounds and their nonfluorinated counterparts to the EOC cell lines IGROV1 and A2780, characterized by similar levels of PCFT expression and an ~11-fold difference in FRα (IGROV1 > A2780).11 We measured the antiproliferative efficacies of these compounds in the presence of 25 nM leucovorin (LCV) (approximating physiologic folate concentrations in human serum); the results are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

IC50 Values (nM) for Antifolate Inhibition of Parental and FRα Knockdown EOC Sublinesa

| IGROV1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | 2′/3′-F | A2780 | WT | WT (Ade/Thd/AICA) | NTC | FR KD-4 | FR KD-10 |

| PMX | − | 39.4(9.2) | 104(11) | Thd/Ade | 71.0(8.5) | 46.6(10.4) | 22.2(6.6) |

| 1 | − | 27.4(3.4) | 16.7(3.4) | Ade/AICA | 10.1(1.5) | 190(99) | 74.6(33.9) |

| 2 | − | 14.2(3.6) | 4.37(0.95) | Ade/AICA | 5.21(1.59) | >1000 | >1000 |

| 8 | + | 13.6(4.2) | 5.44(0.81) | Ade/AICA | 6.89(1.13) | >1000 | >1000 |

| 3 | − | 2.72(0.53) | 2.01(0.14) | Ade/AICA | 1.97(0.69) | 453(262) | 190(48) |

| 9 | + | 2.14(0.18) | 1.67(0.30) | Ade/AICA | 1.14(0.25) | 41.0(12.7) | 19.2(4.3)* |

| 4 | − | 5.42(1.39) | 1.87(0.19) | Ade/AICA | 1.55(0.18) | 64.1(6.5) | 30.5(0.5) |

| 10 | + | 15.7(3.6)* | 6.36(1.04)* | Ade/AICA | 5.17(1.34)* | >1000 | >1000* |

| 5 | − | 28.8(1.4) | 54.3(4.8) | Ade/AICA | 40.7(5.8) | >1000 | >1000 |

| 11 | + | 3.11(0.14)* | 1.90(0.15)* | Ade/AICA | 1.79(0.19)* | 138(6.8) | 66.9(28.3)* |

| 6 | − | 21.7(1.5) | 12.1(1.6) | Ade/AICA | 12.8(1.4) | 80.5(24.2) | 30.3(2.1) |

| 12 | + | 7.6(1.0)* | 6.92(1.03)* | Ade/AICA | 5.61(1.20)* | 85.6(3.9) | 42.2(11.2) |

Growth inhibition assays were performed using the A2780 and IGROV1 EOC cell lines, as well as FRα-knockdown sublines (KD-4, KD-10) and non-targeted control (NTC) cells derived from IGROV1 cells.11 Results are shown as a mean values from five experiments (± standard errors in parentheses) as IC50 values, representing the concentrations at which growth of 50% of cells was inhibited relative to untreated cells. IC50 values of fluorinated compounds that were statistically different from those of the corresponding parent compounds (Figure 2 and Table 1) within each cell line are marked with * (p < 0.05). Results are also summarized for IGROV1 cells for the protective effects of adenosine (60 μM), thymidine (10 μM), or 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide (320 μM). For compounds 3, 8, 10 and 11, nucleoside/AICA protection results are shown in Figure 6. Methods are summarized in the Experimental Methods. Undefined abbreviations: Ade, adenosine; AICA, 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide; Thd, thymidine.

In most cases, the results with the EOC cell lines recapitulated findings with the engineered isogenic CHO and HeLa sublines in Table 1. For instance, in IGROV1 EOC cells, which expressed the highest level of FRα, all analogues were quite active, as reflected in their nanomolar IC50 values, although for 5 activity was somewhat decreased. Relative drug sensitivities were decreased overall in the A2780 EOC subline compared to IGROV1 cells. Generally, the analogues that showed the highest levels of PCFT-targeted activity in R2/PCFT4 and R1–11-PCFT cells (e.g., 9, 11, 12; Table 1) also showed the greatest potencies toward the EOC sublines, and these fluorinated compounds were 2- to >12-fold more potent than 1 (Table 3).

To further demonstrate the relative impact of FRα versus PCFT on drug efficacy, we tested the antiproliferative effects of the novel compounds with IGROV1 sublines in which FRα was knocked down ~90% by shRNA lentivirus,11 compared to nontargeted control (NTC) cells (Table 2). PMX efficacy was slightly increased (~2–3-fold) upon FRα knockdown, reflecting its modest FRα substrate activity and likely decreased intracellular folate pools accompanying loss of FRα, analogous to the impact of loss of facilitated folate transport.52 However, for the 6-substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine compounds, drug effects were decreased (increased IC50 values) upon FRα knockdown, albeit to variable degrees. Thus, compounds with the least PCFT-targeted activities (in R2/PCFT4 CHO and R1–11-PCFT4 HeLa cells, Table 2), including 2, 5, 8, and 10, showed a complete loss of growth inhibition up to 1000 nM drug. Analogues with the greatest extent of PCFT-targeted activities (Table 1), including 4, 6, 9, 11, and 12 (along with 1) (Table 2), preserved substantial antiproliferative activities (19–138 nM) in IGROV1 knockdown cells, despite significant loss of FRα. This likely reflects PCFT transport. Notably, these studies were performed at neutral pH; the impact of PCFT-targeting on in vitro drug efficacy should be even greater under the acidic pH conditions (pH 6.5–6.8) of the microenvironment of solid tumors.18,53–55

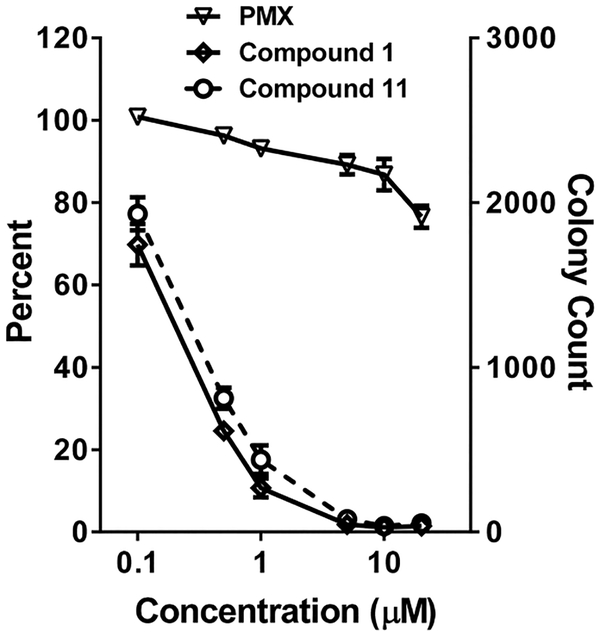

To simulate drug exposures at acidic pHs, we performed colony-forming assays in IGROV1 EOC cells with 11, compared to 1 and PMX. IGROV1 cells were treated with drugs at pH 6.8 for 24 h (conditions that strongly favor cellular uptake by PCFT) at concentrations up to 20 μM. Cells were washed with PBS, then plated in drug-free media up to 10 days. In this assay, both 1 and 11 potently inhibited colony formation (IC50 values of 0.27 and 0.20 μM, respectively) (Figure 5). As previously reported,11 PMX was marginally active under these experimental conditions (IC50 > 20 μM). For 11, like 1 previously,11 these results confirm greater than 99% cell killing.

Figure 5.

Colony-forming assay to assess cytotoxicity of 6-subsituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine analogues. IGROV1 EOC (~10 000) cells were plated in 100 mm dishes in complete folate-free RPMI 1640 (pH 7.2), 10% dialyzed FBS, and 25 nM LCV. After 24 h, cells were treated with PMX, 1, or 11 at varying concentrations (0.1 to 20 μM) in complete folate-free RPMI 1640 adjusted to pH 6.8 and supplemented with 25 nM LCV. After an additional 24 h, cells were rinsed with PBS, then incubated in complete folate-free RPMI 1640 supplemented with 25 nM LCV (pH 7.2–7.4) for 10 days. Colonies were stained with methylene blue; colony numbers were electronically counted, and results were normalized to the controls. Plots show mean ± SE values, representative of triplicate experiments. IC50 values (μM) were as follows: PMX, >20 μM; 11, 0.27 μM, 1, 0.20 μM.

Metabolic Effects of Fluorinated and Nonfluorinated 6-Substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine Analogues.

Previous reports established that the nonfluorinated 6-substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine compounds 2–6 are all potent inhibitors of de novo purine nucleotide biosynthesis at GARFTase, the first folate-dependent enzyme in this pathway.25,27–29

To identify the targeted pathway(s) of the fluorinated pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine analogues 8–12, we assessed the growth inhibition of IGROV1 EOC cells by this series in the presence of thymidine (10 μM) or adenosine (60 μM).25,27,28,30,42,45,50 As depicted in Figure 6 for compounds 8, 10, and 11, along with 3, and summarized in Table 3 for all the fluorinated and desfluorinated analogues in this report, adenosine completely reversed the drug effects, whereas thymidine was completely ineffective. 5-Aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide (AICA) (320 μM) was also effective at reversing drug effects. Since AICA circumvents the GARFTase step to provide substrate (AICA ribonucleotide or ZMP) for the AICARFTase reaction (the ninth reaction in the purine pathway), this strongly suggests that GARFTase is the principal intracellular target for all the inhibitors.25,27,28,30,42,45,50

Figure 6.

Protection experiments: growth inhibition of IGROV1 EOC cells and protection by excess folic acid, nucleosides, and AICA. IGROV1 cells were plated (2000 cells/well) in folate-free RPMI 1640 medium with 10% dialyzed FBS, antibiotics, L-glutamine, and 25 nM LCV with a range of drug concentrations in the presence of folic acid (200 nM), adenosine (60 μM), thymidine (10 μM), or AICA (320 μM). Cell proliferation was assayed with Cell Titer Blue (Promega) using a fluorescence plate reader. Data are representative of at least triplicate experiments. Error bars represent the standard errors. These data and those for the other 6-substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine analogues are summarized in Table 3.

To further verify GARFTase inhibition and determine relative inhibition potencies in cells, we utilized an in situ GARFTase assay, which measures the accumulation of [14C]formyl GAR from [14C]glycine in IGROV1 cells treated with azaserine (4 μM).25,27,28,30,42,45,50 IGROV1 cells were treated with a range of concentrations of the targeted fluorinated and nonfluorinated analogues at pH 6.8 for 24 h. Compound 1,30 an established GARFTase inhibitor, was included as a positive control and PMX, which modestly inhibits GARFTase, was used as a negative control. All the 6-substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine analogues were potent GARFTase inhibitors, and with the exception of 2 and 8, all compounds showed IC50 values less than 3 nM that were not statistically different (Figure 7). For PMX, the IC50 was 29.2 nM. Only for compounds 3 and 9 was the extent of GARFTase inhibition significantly different between the fluorinated antifolate and its nonfluorinated counterpart (IC50 of 1 nM compared to 2.5 nM; p < 0.05) (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Inhibition of GARFTase activity in IGROV1 EOC cells by fluorinated and nonfluorinated pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine compounds. Incorporation of [14C(U)]glycine into [14C]formyl GAR was used as an in situ measure of endogenous GARFTase activity in IGROV1 EOC cells. Cells were treated with a range of drug concentrations in media, which was adjusted to pH 6.8. Experimental details are summarized in the Experimental Methods. IC50 values (nM) were calculated and are listed with standard errors (in parentheses). Data are representative of triplicate experiments.

Molecular Modeling.

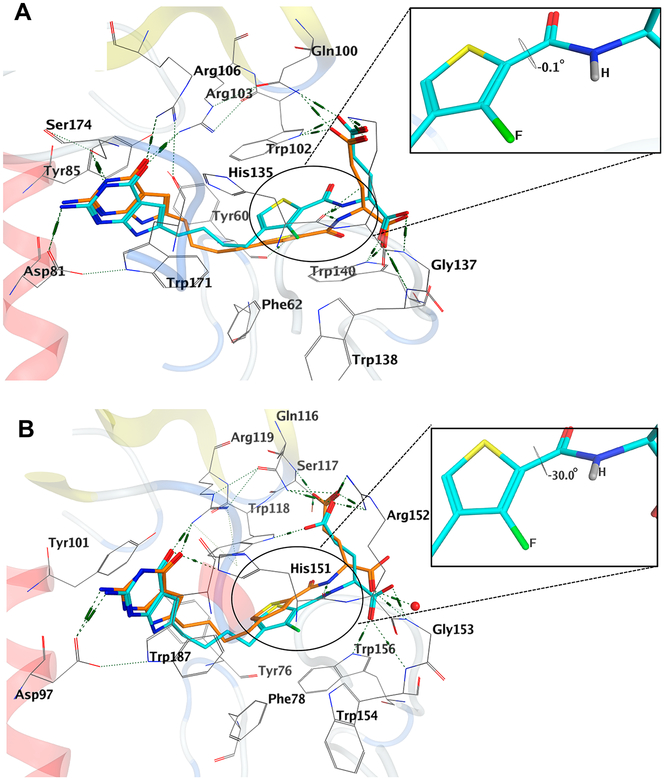

Molecular modeling studies were carried out using our X-ray crystal structures of human FRα (5IZQ),56 FRβ (4KN2),57 and GARFTase (5J9F)56 to provide further validation of these drug targets for our tumor-targeted analogues.

The results of molecular modeling studies in the folate binding cleft of FRα and FRβ for the lead compound 5 and its fluorinated analogue 11 are shown in Figure 8 as an example of our docking analyses. The compounds display similar interactions as the native crystal structure ligands56 (not shown here for clarity), by maintaining key interactions involving the bicyclic scaffolds and the benzoyl L-glutamate tail.

Figure 8.

Molecular modeling studies using the human FRα (PDB 5IZQ)56 and FRβ (PDB 4KN2)57 crystal structures. (A) Superimposition of the docked pose of 11 (cyan) with the docked pose of 5 (orange) in FRα. (B) Superimposition of the docked pose of 11 (cyan) with the docked pose of 5 (orange) in FRβ.

The docked pose of 5 in FRα (Figure 8A) shows the 2-NH2 of 5 interacting in a hydrogen bond with Asp103 (81) (for FRα, full-length gene product numbers are designated along with numbering of the mature protein in parentheses). The 3-NH of 5 forms a hydrogen bond with the side-chain hydroxyl of Ser196 (174), and the 4-oxo moiety of 5 forms two hydrogen bonds, one each with side-chain nitrogens of Arg125 (103) and Arg128 (106). The pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine scaffold is stacked amid the hydrophobic aromatic side chains of Tyr82 (60), Tyr107 (85) and Trp193 (171), similar to that seen with the bicyclic ring of the crystallized ligand (for van der Waals and hydrophobic interactions).56 The L-glutamate moiety of 5 occupies a similar binding space as the corresponding L-glutamate of the native ligand.56 The amide NH of 5 forms a hydrogen bond with the backbone carbonyl of His157 (135). The α-carboxylate of 5 forms a network of hydrogen bonds involving the backbone NH of Gly159 (137) and Trp160 (138), and the side-chain NH of Trp162 (140), while the γ-carboxylic acid of 5 forms ionic interactions with the side-chain protonated amine of Lys158 (136) and the side-chain NH of Gln122 (100) and Trp124 (102). The four carbon bridge of 5 is positioned in a hydrophobic region formed by Tyr82 (60), Phe84 (62), Trp124 (102), and His157 (135).

In Figure 8B, the docked poses of 5 and 11 in FRβ are shown. In the docked pose of 5 with FRβ, the 2-NH2 group of the ligand interacts in a hydrogen bond with Asp99 (97) (again for FRβ, the full-length gene product numbers are designated with numbering of the mature protein in parentheses), and the 4-oxo moiety forms two hydrogen bonds, one each with the side-chain nitrogens of Arg121 (119) and His153 (151). The pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine scaffold is stacked amid the hydro-phobic aromatic side chains of Tyr103 (101) and Tyr189 (187) (for van der Waals and hydrophobic interactions) similar to that seen with the bicyclic ring of the crystallized ligand.57 The L-glutamate moiety of 5 occupies a similar binding space as the corresponding L-glutamate of the native ligand.57 The amide NH of 5 forms a hydrogen bond with the backbone carbonyl of His153 (151). The α-carboxylate of 5 forms a hydrogen bond with the backbone NH of Gly155 (153) and a conserved water molecule, while the γ-carboxylic acid of 5 forms a salt bridge with the side chain of Arg138 (136) and hydrogen bonds with the side-chain, as well as the backbone, NH of Ser119 (117) and the backbone NH of Gln118 (116). The bridge and the thiophene ring of 5 is positioned in a hydrophobic region formed by Tyr78 (76), Phe80 (78), Trp120 (118), and Trp158 (156).

The docked poses of 11 in FRα and FRβ (Figures 8A,B) retain the interactions seen for the lead compound 5. Additionally, in FRβ, the α-carboxylate of 11 forms hydrogen bonds with the side chain of Trp158 (156) and the backbone NH of Gly155 (153). The γ-carboxylate alternatively forms a hydrogen bond with Trp120 (118) instead of Ser119 (117). The docked scores for 5 and 11 in FRα were −47.54 and −50.87 kJ/mol, respectively; in FRβ, the docked scores for 5 and 11 were −55.42 and −55.02 kJ/mol, respectively.

Figure 9 shows the docked poses of the lead compound 5 and the fluorinated compound 11 in the GARFTase active site. The pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine scaffold of 5 binds in the same region as that occupied by the bicyclic scaffold of the native ligand in the GARFTase crystal structure (PDB 5J9F, native ligand not shown for clarity).56 The scaffold is stabilized in the binding site by multiple interactions, a hydrogen bond between the N1 nitrogen of 5 and the backbone of Leu899, 2-NH2 of 5 and the carbonyl of Leu899, N3 of 5 and the backbone carbonyl of Ala947, and the 4-oxo of 5 and the amide of Asp951. Additionally, the 4-oxo of 5 forms a water-mediated hydrogen bonding network via a conserved water molecule with Ala947, Ala952, and Asp949. The N7-nitrogen of 5 forms a hydrogen bond with the backbone carbonyl of Arg897. The pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine bicyclic scaffold of 5 also participates in van der Waals interactions with Val950. The amide NH of the L-glutamate of 5 forms a hydrogen bond with the carbonyl of Met896. The L-glutamate of 5 is oriented with the α-carboxylate forming a salt bridge with the side-chain of Arg897 and a hydrogen bond interaction with the backbone amide NH of Ile898. The γ-carboxylate forms ionic interactions with the side-chain of Lys844.

Figure 9.

Molecular modeling studies with human GARFTase (PDB 5J9F).56 Superimposition of the docked pose of 11 (cyan) with the docked pose of 5 (orange).

The docked pose of 11 retains the same interactions in GARFTase as the parent analogue 5 (Figure 9). Additionally, the 2-NH2 of 11 hydrogen bonds with the backbone carbonyl of Glu948. The docked scores of 5 and 11 in GARFTase were −58.66 and −64.10 kJ/mol, respectively.

Comparing the docked poses of the parent 5 and fluorinated 11 in FRα, FRβ, and GARFTase (Figures 8 and 9), the slight increase in size at the 3′-position with C(sp2)F (1.32 Å) replacement of a C(sp2)H (1 Å) bond, preserved the required orientation and interactions of the scaffold and side-chain groups. In all of the docked poses (Figures 8A,B and 9), the fluorine atom and the amide NH of the L-glutamate are positioned on the same side in a syn conformation (−0.1° to −30° dihedral angles, Figures 8A,B and 9) for a favorable intramolecular hydrogen bond. This hydrogen bond is not observed in the docked structure, as the NH is involved in a much stronger and more productive hydrogen bond with the backbone carbonyl of the target proteins. However, if such an intramolecular N–H···F interaction exists in the low energy state of the unbound ligand, the conformation of the side-chain NH could stabilize the bound conformation and thus provide an entropic benefit upon binding.

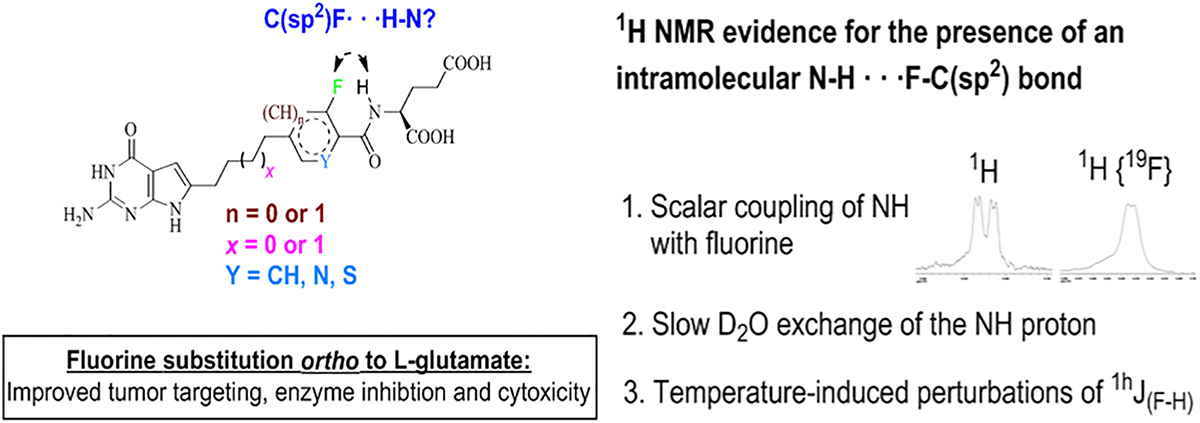

NMR Evidence for the Presence of Intramolecular N−H···F−C(sp2) Hydrogen Bond in Solution State of the Fluorinated Analogues.

The relative syn conformations (−0.1° to −30° dihedral angles of the fluorinated analogues (Figures 8A,B and 9) in the target proteins prompted a conformational study of the orientations of the fluorinated (het)arylamide side chains of the analogues in their unbound solution state. Energy minimization of the free ligand 8 (representative example, Figure 10A) orients the fluorine and the amide NH in a syn conformation, facilitating a weak intramolecular fluorine–hydrogen bond (bond energy = −0.5 kcal·mol−1). The NMR spectra in DMSO-d6 of the fluorinated analogues 8, 9, 11, and 12 confirmed the presence of spin−spin coupling between fluorine and the amide NH. The 1H NMR of the NH proton is a doublet of a doublet due to scalar coupling with the α-CH proton and the fluorine atom (Figure 10B) which collapsed to a doublet when decoupled from the α-CH proton (Figure 10C, J(H,F) = 1.54 Hz) and in 1H {19F} NMR (Figure 10D, 3J(H–H) = 7.11 Hz). This indicates nuclear spin coupling with fluorine.25,27–29 Such coupling between a fluorine atom and the amide proton of the side chain of L-glutamate was generalized in previous reports as a N–H···F−C(sp2) hydrogen bond.41,58

Figure 10.

Representative example with compound 8 (yellow) of an energy minimization study and its NH signal by 1H NMR. (A) Intramolecular fluorine−hydrogen bond (bond energy = −0.5 kcal·mol−1) detected in energy-minimized free ligand 8 using MOE 2016.08.59 (B) 400 MHz 1H NMR, doublet of a doublet NH peak. (C) 400 MHz 1H NMR α-CH decoupled signal of NH proton (1hJ(F−H) = 1.54 Hz). (D) 500 MHz 1H NMR,1H{19F} NMR signal of NH proton (3J(H−H) = 7.11 Hz). NMR studies were carried out in DMSO-d6, and the excessive broadening of the NH signal is due to 14N quadrapolar relaxation.

Though the collapse of the doublet of doublets in both decoupling NMR spectra (Figure 10b,c) confirm coupling between 19F and 1H, it is still ambiguous whether nuclear spin information is transmitted through bond or through space (hydrogen bond). We observed that when equal concentrations of the compounds dissolved in DMSO-d6 were D2O exchanged, the amide NH proton of the fluorinated analogues take longer time periods (>1 h) to exchange completely (Supporting Information, Figure 1S) compared to the nonfluorinated analogues (<5 min). This observation supports, in part, the notion of a significant involvement of the NH proton (in the fluorinated analogues) in a fluorine−hydrogen bond.60 Evidence has been published supporting the concept that a fluorine substituted on an sp2 carbon can serve as a hydrogen bond acceptor.61 The presence of a fluorine−hydrogen bond in analogues 8, 9, 11, and 12 is further supported by literature reports confirming the occurrence of hydrogen bonds in 2-fluorobenzamide derivatives.62–64 This NMR study (Figure 10) strongly indicates that the fluorine and amide NH are in a relative syn orientation akin to the docked (bound) conformations in the target proteins (FRα/β and GARFTase, Figures 8A,B and 9).

The detection of “through-space” couplings between the nuclei directly involved in hydrogen bonding can establish the presence of an −NH···F−C(sp2) hydrogen bond in the analogues 8, 9, 11, and 12.64 However, the 1H−19F HOESY (heteronuclear NOESY) NMR for 8 (representative example) did not detect any through-space coupling between the fluorine and the NH proton. This observation is ambiguous as the absence of an observable interaction in the 2D HOESY NMR does not necessarily rule out the presence of a weak hydrogen bond.65

Temperature-induced perturbations of 1hJ(F−H) are of particular interest as increased temperature disrupts intra-molecular hydrogen bonds and consequently diminishes the intensity of the observable 1hJ(F−H) coupling. Compound 8 was subjected to temperature perturbations over the range of 292–352 K in DMSO-d6 and ΔJ(F−H) were monitored. The J(F−H) varied from 1.54 (292 K) to 3.12 (352 K) Hz, which is uncommon for spin−spin couplings across covalent bonds. This clear variation of J(F−H) with temperature is a strong indicator of through space scalar 1hJ(F−H) coupling (the observable spin−spin coupling constants of the other protons in the 1H NMR did not change significantly). The numerical values of 1hJ(F−H) at varied temperatures are reported (Table 4).

Table 4.

Variation of J(F–H) in 8 with Temperature

| |

|---|---|

| temp (K) | 1hJ(F–H) (Hz) |

| 292 | 1.54 |

| 312 | 2.38 |

| 332 | 2.70 |

| 352 | 3.12 |

However, contrary to an expected loss, increased 1hJ(F−H) interaction at higher temperatures was observed. It remains to be determined if the −NH···F−C(sp2) hydrogen bond in 8 is stabilized at higher temperatures owing to a conformational shift to a more linear −NH···F bond angle and geometric proximity.

Though a fluorine−hydrogen bond is characterized by weak binding energies (~1–4 kcal·mol−1), such an interaction can be expected to be energetically important. As can be observed from the in vitro studies, a general trend of improved uptake, enzyme inhibition, and cytotoxicity was observed upon substitution of a fluorine ortho to the L-glutamate. Our hypothesis is that, if the intramolecular fluorine−hydrogen bond is maintained in the anionic form of the analogues at body temperature (~310 K, Table 4) within the aqueous environment in vivo, it may not only restrict the number of conformations of the aromatic side chain and the amide group but also stabilize the relative syn conformation of the (het)aryl amide side chain in its bound form, thus providing an entropic benefit upon binding.32,37,66 It is imperative that the weak fluorine−hydrogen bond breaks upon binding, as the amide NH is involved in a very critical and energetically more favorable hydrogen bond with the target proteins (Figures 8 and 9).

In Vivo Antitumor Efficacy for Compound 11 with IGROV1 EOC Xenografts.

Based on the in vitro efficacies of 11 toward IGROV1 human EOC cells (Table 3), we extended our studies to an in vivo drug efficacy trial. The in vivo trial was performed with female NCR severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mice bilaterally (subcutaneous) implanted with IGROV1 human EOC xenografts. In vivo efficacy for 11 was compared to that for 1, the most active PCFT-targeted pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine analogue previously identi-fied.11,19,30,67 For the trial, the mice were fed a folate-deficient diet ad libitum to reduce serum folate concentrations to levels approximating those reported in humans.68 A control cohort included tumor-bearing mice fed standard (folate-replete) chow. Mice were nonselectively randomized into control and treatment groups (5 mice/group). The pyrrolo[2,3-d]-pyrimidine compounds were administered intravenously (iv) beginning on day 3 following tumor engraftment, using doses slightly below their respective maximum tolerated doses. Dosing was as follows: 11, Q4dX4 at 95 (mg/kg)/inj, for a total dose of 380 mg/kg; and 1, Q4dX3 at 32 (mg/kg)/inj, for a total dose of 96 mg/kg. The tumors were measured twice each week; overall health and body weights of the mice were recorded daily. For mice on the folate-deficient diet, both compounds 1 and 11 were efficacious. On day 60, the median tumor burdens were 700 mg (range, 259–1153 mg) for the control, 108 mg (range, 0–196 mg) for 1, and 0 mg (range, 0–523 mg) for 11, giving T/C values (based on median tumor measurements) of 15% for 1 and 0% for 11. Tumor growth delays (T − C to reach 1000 mg in days) of 28 days for 1 and 35 days for 11 were recorded (Figure 11). Treatments with 1 and 11 were generally well tolerated with moderate weight losses (15.7% median nadir on day 14 and 12.1% median nadir on day 18) that were completely reversible upon conclusion of therapy. For mice on the standard (high folate) diet, antitumor activities for 1 and 11 were ablated. No weight losses or other adverse symptoms were observed.

Figure 11.

In vivo efficacies of compounds 11 and 1 toward the IGROV1 EOC xenografts. Female ICR SCID mice (10 weeks old; 20 g average body weight) were maintained on a folate-deficient diet ad libitum for 14 d prior to subcutaneous tumor implantation to decrease serum folate to a concentration approximating that in human serum. Human IGROV1 tumors were implanted bilaterally, and mice were nonselectively randomized into 5 mice/group. Dosing began on day 3 following engraftment and was as follows: 11, Q4dX4 at 95 (mg/kg)/inj, total dose of 380 mg/kg; and 1, Q4dX3 at 32 (mg/kg)/inj, total dose of 96 mg/kg. The drugs were dissolved in 5% ethanol (v/v), 1% Tween-80 (v/v), and 0.5% NaHCO3 and were administered intravenously (0.2 mL/injection). The tumors were measured twice each week.

The results from the in vivo efficacy trial with FRα- and PCFT-expressing IGROV1 human EOC xenografts substantiate our in vitro antitumor efficacy results and establish that at equitoxic dose levels, 11 is more efficacious in vivo than 1, as reflected in the T/C and T − C metrics, albeit with a higher dose requirement. For both 1 and 11, there were no acute or long-term toxicities other than completely reversible loss of weight.

Conclusions.

In this report, we synthesized 2′ and 3′ (o- to L-glutamate) fluorinated analogues (9–12) based on their parent molecules (Figure 1) with the goal of improving activity spectra, including their cellular uptake by PCFT or FRs and GARFTase inhibition, resulting in increased potent antitumor efficacy. Introduction of fluorine atoms in a bioactive molecule is a well-established strategy for increasing biological activities of drugs.31,32 As a consequence of direct effects in increasing their amphipathic character (resulting in polar and hydrophobic interactions with receptors and enzyme targets) or indirect effects involving drug metabolism, lipophilicity, changes in acidity and basicity, etc.,33–38 fluorination frequently imparts superior target affinities and enhanced ADME profiles to drugs. Further, 18F-labeled drugs can also be utilized as theranostic agents for PET imaging, providing a measure of tumor burden and drug uptake by tumors in individual patients.69

Our current studies confirmed that strategic insertion of fluorine atoms in the side-chain aromatic ring resulted in significant changes in drug pharmacodynamic parameters. These include both increased (8, 9, 11, 12) and decreased binding affinities (10) for PCFT and FRα that at least in part impact in vitro drug efficacies toward isogenic CHO or HeLa cell line models engineered to individually express these transport systems. In general, the results with the CHO and HeLa cell lines were recapitulated in IGROV1 and A2780 EOC cell lines, which express similar RFC and PCFT levels but differ ~11-fold in amounts of FRα.11 Despite appreciable differences in FR levels, drug activities toward both IGROV1 and A2780 EOC cells were substantial, with the analogues showing the greatest PCFT-targeted activity (i.e., 9, 11, 12) also showing the greatest potencies toward the EOC cells independent of the level of FRα. The critical role of PCFT as a determinant of overall drug activity in IGROV EOC cells was further demonstrated by knocking down FRα. Under these conditions, significant in vitro efficacy was preserved, albeit only for the compounds with the most potent PCFT-targeted activity. Notably, in vitro efficacies of these fluorinated compounds toward the EOC cells were equal to or exceeded those for 1, previously the most potent 6-substituted pyrrolo[2,3-d]-pyrimidine analogue we have discovered.11,19,30,67 For 9 and 11, selectivity toward PCFT and FRα over RFC (as reflected in IC50 values toward engineered HeLa cells expressing only RFC versus PCFT or FRα) far exceeded that for 1. While fluorine-substituted analogues, like their nonfluorinated counterparts, all inhibited GARFTase with nanomolar IC50 values, with the exception of compounds 3 and 9, fluorine substitution in itself had no apparent impact on the potency of GARFTase inhibition as the potencies of the fluorinated and non-fluorinated analogues toward cellular GARFTase were similar.

Molecular modeling indicated that the fluorinated analogues adopted bound conformations in FRα/β and GARFTase where the fluorine is positioned on the same side (syn) as the NH of the L-glutamate. NMR studies indicated that in DMSO-d6, these fluorinated analogues favor similar conformations as the unbound forms with a N−H···F−C(sp2) bond.

Based on in vitro studies with 11 in IGROV1 EOC cells, we performed a head-to-head comparison of 11 with 1 in an in vivo efficacy trial with IGROV1 EOC subcutaneous xenografts in SCID mice. In this study, compound 11 showed greater antitumor efficacy than 1, albeit with a somewhat greater dose requirement. Importantly, for both 11 and 1, toxicity, as reflected in reversible weight loss as a consequence of drug treatment, was completely manageable.

In conclusion, we established that 2′ and 3′ (ortho to L-glutamate) fluorine substitutions in the side-chain aromatic ring of 6-substituted bridged pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine analogues preserve substantial antitumor efficacy for this series, while impacting pharmacodynamic properties related to drug uptake by the PCFT and FRα. The lead fluorinated compounds in this report including 9 and 11 showed significantly greater selectivity than 1 for transport via FRα, FRβ, and PCFT over RFC and equal or greater antitumor efficacies. We hypothesize that the significant increases in the activities of the fluorinated compounds over their parent analogues are at least in part a consequence of an intramolecular F···NH bond, as observed in our NMR studies. This can provide an entropic benefit upon binding by restricting the number of side-chain conformations of the unbound ligand and also by promoting the bound conformation. Additional SAR studies are underway to further test this hypothesis. These novel compounds may find new applications for targeted therapies of cancer in their own right and could be also used as theranostics, which combine 18F labeling and PET imaging with targeted therapy based on their selective uptake into tumors by PCFT and FRs over RFC.

EXPERIMENTAL METHODS

Evaporation in vacuo was carried out using a rotary evaporator and a high vacuum pump. CHEM-DRY drying apparatus was used to dry the final compounds over P2O5 at 50 °C. Uncorrected FLUKE 51 K/J electronic thermometer equipped MEL-TEMP II melting point apparatus was used to record melting points. 1H NMR and 19F NMR were recorded using a Bruker WH-400 (400 MHz) spectrometer or a Bruker AV-III 500 MHz spectrometer using a BBFO-Plus probe. The solutions of the synthesized molecules were prepared in the NMR solvent CDCl3 or DMSO-d6. Th6e 1H homonuclear decoupling experiments were carried out individually at each elevated temperature (data acquisition each time was delayed until the temperature was stabilized). The 2D HOESY NMR was carried out using a standard 1H/19F HOESY experiment with 19F detection. 1H and 19F spectra were referenced to TMS and trifluoroacetic acid, respectively, as the internal standards to express the chemical shifts in ppm (parts per million): s, singlet; d, doublet; t, triplet; q, quartet; quin, quintet; m, multiplet; bs, broad singlet. Chemical names follow IUPAC nomenclature. Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was performed on Whatman Sil G/UV254 silica gel plates with a fluorescent indicator, and the spots were visualized under a UV lamp at 254 and 365 nm illumination. All analytical samples were run in three different solvent systems on TLC to test for homogeneity. For chromatography, columns of silica gel (230–400 mesh) (Fisher, Somerville, NJ) were used. Despite 24–48 h of drying in vacuo, solvents could not be completely removed and the fractional moles of water in the analytical samples were confirmed by their presence in their respective 1H NMR spectra. Chemicals and solvents were purchased from Matrix scientific, Oakwood chemical, Ark Pharm. Inc., Aldrich Chemical Co., or FisherScientific Co. and were used as received. Elemental analysis (C, H, N, F, S) was performed by Atlantic Microlab, Inc. (Norcross, GA). Element compositions were within 0.4% deviation from the calculated values and validated >95% purity of all the compounds submitted for biological evaluation (Supporting Information, Table 1S).

General Procedure for the Synthesis of Compounds 7, 8, 10, and 11.

To a Parr flask with 10% palladium on activated carbon soaked in ethanol (60 mg) was added a methanolic solution of 16a−d. Hydrogenation was carried out at 55 psi of H2 for 12 h. The reaction mixture was filtered through Celite, washed with MeOH and concentrated under reduced pressure to give the reduced alkanes as sticky solids. To the concentrate was added 1 N NaOH, and the mixture was stirred under N2 at room temperature for 1 h. TLC showed the disappearance of the starting material (Rf = 0.45) and one major spot at the origin (CHCl3/MeOH 5:1). The solution was cooled in an ice bath, and the pH was adjusted to 3–4 with dropwise addition of 1 N HCl. The resulting suspension was cooled to 4–5 °C in the refrigerator overnight and filtered. The residue was thoroughly washed with cold water and dried in vacuum using P2O5 to afford the target compounds 7, 8, 10, and 11.

General Procedure for the Synthesis of Target Compounds 9 and 12.

The glutamate esters 23a,b were saponified by dissolving in 1 N NaOH and stirring at room temperature for 1 h. Upon completion of the hydrolysis, TLC indicated consumption of the starting material (Rf = 0.45) and generation of one major spot at the baseline (CHCl3/MeOH 5:1). The solution was cooled in an ice bath and the pH was adjusted to 3–4 by dropwise addition of 1 N HCl. The resulting suspension was cooled to 4–5 °C in the refrigerator overnight, and filtered. The resultant residue was washed with a small amount of cold water and dried in vacuo using P2O5 to afford the target compounds 9 and 12 as powders.

(4-(4-(2-Amino-4-oxo-4,7-dihydro-3H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-6-yl)butyl)-3-fluorobenzoyl)-L-glutamic Acid (7).

Compound 7 was prepared using the general method described for the preparation of 7, 8, 10, and 11 from 16a (100 mg, 0.2 mmol) to give 50 mg (65%) of 7 as a light yellow powder. Mp 163.1 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 1.59–1.60 (m, 4 H, CH2CH2), 1.93–2.15 (m, 2 H, β-CH2),2.34–2.37 (m, 2H, γ-CH2), 4.35–4.43 (m, 1 H, α-CH), 5.85–5.86 (d, J = 4.41 Hz, 1 H, C5-CH), 5.97 (s, 2 H, 2-NH2, exch), 7.40–7.42 (d, J = 8.88 Hz, 1 H, Ar), 7.65–7.67 (m, 2 H, Ar), 8.63–8.66 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1 H, CONH, exch), 10.13 (s, 1 H, 3-NH, exch), 10.80 (s, 1 H, 7-NH, exch). Anal. Calcd for (C22H24FN5O6·1.51H2O). C, H, N, F.

(4-(4-(2-Amino-4-oxo-4,7-dihydro-3H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-6-yl)butyl)-2-fluorobenzoyl)-L-glutamic Acid (8).

Compound 8 was prepared using the general method described for the preparation of 7, 8, 10, and 11, from 16b (80 mg, 0.15 mmol) to give 40 mg (55.5%) of 8 as a light yellow powder. Mp 137.4 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 1.57–1.58 (m, 4 H, CH2CH2), 1.81–2.14 (m, 2 H, β-CH2), 2.32–2.37 (m, 2 H, γ-CH2), 2.63ȁ32.66 (t, J = 6.40, 6.40 Hz, 2 H, Ar-CH2), 4.36–4.41 (m, 1 H, α-CH), 5.85–5.86 (d, J = 2.10 Hz, 1 H, C5-CH), 6.02 (s, 1 H, 2-NH2, exch), 7.10–7.15 (m, 2 H, Ar), 7.50–7.54 (t, J = 7.86, 7.86 Hz, 1 H), 8.41–8.43 (dd, J = 2.08, 7.83 Hz, 1 H, CONH, exch), 10.18 (s, 1 H, 3-NH, exch), 10.83 (s, 1 H, 7-NH, exch). Anal. Calcd for (C22H24FN5O6·0.82H2O): C, H, N, F.

(4-(3-(2-Amino-4-oxo-4,7-dihydro-3H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-6-yl)propyl)-2-fluorobenzoyl)-L-glutamic Acid (9).

Compound 9 was prepared using the general method described for the preparation of 9 and 12 from 23a (70 mg, 0.15 mmol) to give 55 mg (88%) of 9 as a light yellow powder. Mp 139.4 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 1.87–2.11 (m, 4 H, CH2, β-CH2), 2.33–2.37 (dt, J = 2.92, 7.89, 8.12 Hz, 2 H, γ-CH2), 2.64–2.67 (t, J = 7.53, 7.53 Hz, 2 H, Ar-CH2), 4.37–4.41 (m, 1 H, α-CH), 5.89–5.90 (d, J = 2.11 Hz, 1 H, C5-CH), 6.01 (s, 2 H, 2-NH2, exch), 7.13–7.17 (m, 2 H, Ar), 7.53–7.56 (t, J = 7.80, 7.80 Hz, 1 H, Ar), 8.44–8.46 (dd, J = 2.12, 7.64 Hz, 1 H, CONH, exch), 10.17 (s, 1 H), 10.86 (s, 1 H). Anal. Calcd for (C21H22FN5O6·1.11H2O): C, H, N, F.

(5-(4-(2-Amino-4-oxo-4,7-dihydro-3H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-6-yl)butyl)-3-fluoropicolinoyl)-L-glutamic Acid (10).

Compound 10 was prepared using the general method described for the preparation of 7, 8, 10, and 11 from 16c (116 mg, 0.22 mmol) to give 70 mg (67%) of 10 as a dark brown powder. Mp 200.6 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 1.60–1.63 (s, 4 H, CH2CH2), 1.96–2.0 (m, 2 H, β- CH2), 2.27–2.32 (m, 2H, γ-CH2), 2.70–2.73 (m, 2 H, Ar-CH2), 4.31–4.37 (m, 1 H, α-CH), 5.87–5.88 (d, J = 2.12 Hz, 1 H, C5-CH), 5.98 (s, 2 H, 2-NH2, exch), 7.71–7.75 (d, J = 1.41 Hz, 1 H, Ar), 8.37 (s, 1 H), 8.68–8.70 (d, J = 7.81 Hz, 1 H, CONH, exch), 10.15 (s, 1 H, 3-NH, exch), 10.81 (s, 1 H, 7-NH, exch). Anal. Calcd for (C21H23FN6O6·1.79H2O·0.45HCl). C, H, N, F, Cl.

(5-(4-(2-Amino-4-oxo-4,7-dihydro-3H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-6-yl)butyl)-2-fluorothiophene-3-carbonyl)-L-glutamic Acid (11).

Compound 11 was prepared using the general method described for the preparation of 7, 8, 10, and 11 from 16d (92 mg, 0.17 mmol) to give 60 mg (72%) of 11 as a yellow powder. Mp 162 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 1.59–1.6 (m, 4 H, CH2CH2), 1.91–2.16 (m, 2 H, β-CH2), 2.30–2.34 (t, J = 7.36, J = 7.36 Hz, 2 H, γ-CH2), 4.35–4.44 (m, 1 H, α-CH), 5.86–5.87 (d, J = 1.80 Hz, 1 H, C5-CH), 5.97 (s, 1H, 2-NH2, exch), 7.51–7.52 (d, J = 4.85 Hz, 1 H, Ar), 7.97–8.0 (dd, J = 2.91, 7.88 Hz, 1 H, CONH, exch), 10.14 (s, 1 H, 3-NH, exch), 10.83 (s, 1 H, 7-NH, exch). Anal. Calcd for (C20H22FN5O6S·1.26 H2O). C, H, N, F, S.

(4-(3-(2-Amino-4-oxo-4,7-dihydro-3H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-6-yl)propyl)-3-fluorothiophene-2-carbonyl)-L-glutamic Acid (12).

Compound 12 was prepared using the general method described for the preparation of 9 and 12 from 23b (30 mg, 0.06 mmol) to give 20 mg (75%) of 12 as a yellow powder. Mp 207.8 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 1.84–2.14 (m, 4 H, CH2, β-CH2), 2.30–2.34 (t, J = 7.37, 7.37 Hz, 2 H, γ-CH2), 4.35–4.44 (m, 1 H, α-CH), 5.91–5.92 (d, J = 1.69 Hz, 1 H, C5-CH), 5.99 (s, 2 H, 2-NH2, exch), 7.55–7.56 (d, J = 4.53 Hz, 1 H, Ar), 7.98–8.01 (dd, J = 3.47, 7.42 Hz, 1 H, CONH, exch), 10.15 (s, 1 H, 3-NH, exch), 10.78 (s, 1 H, 7-NH, exch). Anal. Calcd for (C19H20FN5O6S·1.15H2O). C, H, N, F, S.

General Procedure for the Synthesis of Compounds 14a−d.

A mixture of bromo-fluoro-(het)arylcarboxylic acids (13a−d) (1 equiv), N-methylmorpholine (1.2 equiv), and 2-chloro-4,6-dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazine (1.2 equiv) in anhydrous DMF in a round bottomed flask was stirred for 1.5 h at room temperature. Subsequently, N-methylmorpholine (1.2 equiv) and L-glutamic acid diethyl ester hydrochloride (1.5 equiv) was added to the mixture and stirred at room temperature for 5 h. After evaporation of the solvent in vacuo, MeOH was added followed by silica gel, and the solvent was evaporated by further drying. The resulting plug was loaded onto a silica gel column and eluted with hexanes followed by gradual increase of EtOAc to 10% EtOAc in hexanes. Fractions with the desired Rf (TLC) were pooled and evaporated to afford glutamate esters 14a−d as colorless liquids.

Diethyl (4-Bromo-3-fluorobenzoyl)-L-glutamate (14a).

Compound 14a was prepared using the general method described for the preparation of 14a−d from 4-bromo-3-fluorobenzoic acid, 13a (0.5 g, 2.3 mmol), to give 0.78 g (85%) of 14a as a colorless liquid. TLC Rf = 0.45 (hexane/EtOAc, 1:1). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 1.24–1.27 (dd, J = 0.78, 7.09 Hz, 3 H, γ-COOCH2CH3), 1.32–1.35 (dd, J = 0.76, 7.12 Hz, 3 H, α-COOCH2CH3), 2.12–2.53 (m, 4 H, α-CH2, β-CH2), 4.12–4.16 (dq, J = 2.95, 7.11, 7.04, 7.04 Hz, 2H, γ-COOCH2CH3), 4.24–4.3 (q, J = 6.37, 6.37, 6.50 Hz, 2 H, α-COOCH2CH3), 4.73–4.78 (dt, J = 4.97, 7.51, 7.63 Hz, 1 H, α-CH), 7.25–7.27 (d, J = 7.31 Hz, 1 H, Ar), 7.49–7.51 (dd, J = 1.77, 8.27 Hz, 1 H, Ar), 7.63–7.69 (m, 2 H, Ar, CONH, exch).

Diethyl (4-Bromo-2-fluorobenzoyl)-L-glutamate (14b).

Compound 14b was prepared using the general method described for the preparation of 14a–d from 4-bromo-2-fluorobenzoic acid, 13b (2 g, 9 mmol), to give 2.45 g (67%) of 14b as a colorless liquid. TLC Rf = 0.45 (hexane/EtOAc, 1:1). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 1.24–1.27 (t, J = 7.15, 7.15 Hz, 3 H, γ-COOCH2CH3), 1.32–1.35 (t, J = 7.14, 7.14 Hz, 3 H, α-COOCH2CH3), 2.12–2.53 (m, 4 H, β-CH2, γ-CH2), 4.11-.4.16 (dq, J = 0.60, 7.12, 7.07, 7.07 Hz, 2H, γ-COOCH2CH3), 4.24–4.3 ((dq, J = 1.70, 7.14, 7.12, 7.12 Hz, 2 H, α-COOCH2CH3), 4.83–4.87 (ddt, J = 2.02, 5.11, 7.33, 7.33 Hz, 1 H, α-CH), 7.36–7.39 (m, 2 H, Ar, CONH, exch), 7.43–7.45 (dd, J = 1.71, 8.44 Hz, 1 H, Ar), 7.95–7.99 (t, J = 8.38 Hz,1 H, Ar).

Diethyl (5-Bromo-3-fluoropicolinoyl)-L-glutamate (14c).

Compound 14c was prepared using the general method described for the preparation of 14a−d from 5-bromo-3-fluoropicolinic acid, 13c (2 g, 9 mmol), to give 2.7 g (73%) of 14c as a colorless liquid. TLC Rf = 0.45 (hexane/EtOAc, 1:1). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 1.28–1.33 (m, 6H, COOCH2CH3), 2.13–2.36 (m, 2 H, β-CH2), 2.52 (m, 2 H γ-CH2), 4.16–4.27 (m, 4 H, COOCH2CH3), 4.83 (m, 1 H, α-CH), 6.78–6.80 (d, J = 7.52 Hz, 1 H, CONH, exch), 7.18–7.2 (d, 2 H, Ar).

Diethyl (4-Bromo-3-fluorothiophene-2-carbonyl)-L-glutamate (14d).

Compound 14d was prepared using the general method described for the preparation of 14a−d from 4-bromo-3-fluorothiophene-2-carboxylic acid, 13d (1.75 g, 7.8 mmol), to give 2 g (63%) of 2d as a colorless liquid. TLC Rf = 0.44 (hexane/EtOAc, 1:1). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 1.15–1.21 (m, 6H, COOCH2CH3), 1.95–2.16 (m, 2 H, β-CH2), 2.38–2.42 (m, 2 H, γ-CH2), 4.02–4.14 (m, 4 H, COOCH2CH3), 4.34–4.43 (m, 2 H, α-CH), 7.45 (s, 1 H, Ar), 8.26–8.29 (dd, J = 2.22, 7.49 Hz, 1 H, CONH, exch).

General Procedure for the Synthesis of Compounds 16a−d.

To a round-bottomed flask equipped with a magnetic stirrer and purged with N2 was added a mixture of tetrakis(triphenylphosphine)-palladium(0) (0.16 equiv), triethylamine (10 equiv), 14a−d (1.5 equiv), and anhydrous DMF. To the stirred mixture, under N2, was added copper(I) iodide (0.16 equiv) and 15 (1 equiv), and the reaction mixture was stirred at 70 °C for 12 h in a microwave. After evaporation of solvent under reduced pressure, MeOH was added followed by silica gel, and the solvent was evaporated. The resulting plug was loaded onto a silica gel column and eluted with CHCl3 followed by gradual increase to 1% MeOH in CHCl3 and then to 10% MeOH in CHCl3. Fractions with desired Rf (TLC) were pooled and evaporated to afford the alkynes 16a−d.

Diethyl 4-(4-(2-Amino-4-oxo-4,7-dihydro-3H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]-pyrimidin-6-yl)but-1-yn-1-yl)-3-fluorobenzoyl)-L-glutamate (16a).

Compound 16a was prepared using the general method described for the preparation of 16a−d from 15 (100 mg, 0.5 mmol) and diethyl (4-bromo-3-fluorobenzoyl)glutamate, 14a (300 mg, 0.74 mmol), to give 110 mg (42%) of 16a as a brown sticky solid. TLC Rf 0.5 (CHCl3/MeOH 5:1). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 1.12–1.18 (m, 6 H, COOCH2CH3), 1.95–2.13 (m, 2 H, β-CH2), 2.40–2.44 (m, 2H, γ-CH2), 2.65–2.67 (m, 2H, CH2), 4.01–4.12 (m, 4H, COOCH2CH3), 4.38–4.43 (m, 1 H, α-CH), 5.88 (s, 1 H, C5-CH), 6.0 (s, 2 H, 2-NH2, exch), 7.37–7.41 (m, 1 H, Ar), 7.59–7.64 (m, 2 H, Ar), 8.77–8.80 (d, J = 8.26 Hz, 1 H, CONH, exch), 10.23 (s, 1 H, 3-NH, exch), 10.83 (s, 1 H, 7-NH, exch).

Diethyl 4-(4-(2-Amino-4-oxo-4,7-dihydro-3H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]-pyrimidin-6-yl)but-1-yn-1-yl)-2-fluorobenzoyl)-L-glutamate (16b).

Compound 16b was prepared using the general method described for the preparation of 16a−d, from 15 (100 mg, 0.5 mmol) and diethyl (4-bromo-2-fluorobenzoyl)glutamate, 14b (300 mg, 0.74 mmol), to give 80 mg (31%) of 16b as a golden-brown sticky solid. TLC Rf 0.5 (CHCl3/MeOH 5:1). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 1.13–1.20 (m, 6H, COOCH2CH3), 1.83–2.16 (m, 2 H, β-CH2), 2.34–2.40 (m, 2H, γ-CH2), 4.03–4.15 (m, 4H, COOCH2CH3), 4.38–4.43 (m, 1H, α-CH), 5.9–6.01 (m, 3H, C5-CH, 2-NH2, exch), 7.12–7.17 (m, 2 H, Ar), 7.53–7.58 (t, J = 7.86, 7.86 Hz, 1 H, Ar), 8.44–8.47 (dd, J = 2.08, 7.83 Hz, 1 H, CONH, exch), 10.20 (s, 1H, 3-NH, exch), 10.87 (s, 1H, 7-NH, exch).

Diethyl (5-(4-(2-Amino-4-oxo-4,7-dihydro-3H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]-pyrimidin-6-yl)but-1-yn-1-yl)-3-fluoropicolinoyl)-L-glutamate (16c).

Compound 16c was prepared using the general method described for the preparation of 16a−d from 15 (100 mg, 0.5 mmol) and diethyl (5-bromo-3-fluoropicolinoyl)glutamate, 2c (0.3 g, 0.74 mmol), to give 116.6 mg (45%) of 16c as a brown sticky solid. TLC Rf = 0.5 (CHCl3/MeOH 5:1). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 1.14–1.21 (m, 6H, COOCH2CH3), 1.95–2.18 (m, 2H, β-CH2), 2.38–2.42 (t, J = 8.07, 8.07 Hz, 2H, γ-CH2), 4.01–4.15 (m, 4H, COOCH2CH3), 4.44–4.49 (m, 1H, α-CH), 6.01–6.04 (m, 3H, C5-CH, 2-NH2, exch), 7.92–7.96 (dd, J = 1.53, 11.24 Hz, 1H, Ar), 8.47–8.48 (d, J = 1.33 Hz, 1H, Ar), 8.98–9.00 (d, J = 7.89 Hz, 1H, CONH, exch), 10.17 (s, 1H, 3-NH, exch), 10.91–10.92 (s, 1H, 7-NH, exch).

Diethyl (5-(4-(2-Amino-4-oxo-4,7-dihydro-3H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]-pyrimidin-6-yl)but-1-yn-1-yl)-2-fluorothiophene-3-carbonyl)-L-glutamate (16d).

Compound 16d was prepared using the general method described for the preparation of 16a−d, from 15 (60 mg, 0.3 mmol), and diethyl (4-bromo-3-fluorothiophene-2-carbonyl)-glutamate, 14d (0.18 g, 0.44 mmol) to give 92 mg (59%) of 16d as a brown sticky solid. TLC Rf 0.5 (CHCl3/MeOH 5:1). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 1.15–1.24 (m, 6H, COOCH2CH3), 1.96–2.15 (m, 2H, β-CH2), 2.39–2.42 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H, γ-CH2), 4.01–4.14 (m, 4H, COOCH2CH3), 4.37–4.43 (m, 1H, α-CH), 6–6.02 (m, 3H, C5-CH, 2-NH2, exch), 7.94–7.95 (d, J = 4.13 Hz, 1H, Ar), 8.35–8.36 (dd, J = 0.66, 7.87 Hz, 1H, CONH, exch), 10.17 (s, 1H, 3-NH, exch), 10.88 (s, 1H, 7-NH, exch).

General Procedure for the Synthesis of Compounds 19a,b.

To a solution of bromo-(het)arylcarboxylic esters, 18a,b (1.04 equiv) in anhydrous acetonitrile was added palladium chloride (0.04 equiv), triphenylphosphine (0.04 equiv), copper iodide (0.16 equiv), triethylamine (10 equiv), and but-3-yn-1-ol, 17 (1 equiv). The reaction mixture was heated to 100 °C and run for 0.5 h under microwave heating. A silica plug was prepared by adding silica gel and methanol followed by evaporation of the solvent in vacuo, which was then loaded on to a silica gel column and eluted with hexane followed by 50% EtOAc in hexane. The desired fractions (TLC) were pooled and evaporated to afford the (hetero)aryl coupled alkynols 19a,b as oils.

Methyl 2-Fluoro-4-(4-hydroxybut-1-yn-1-yl)benzoate (19a).

Compound 19a was prepared using the general method described for the preparation of 19a,b from 17 (0.58 g, 8.25 mmol) and 18a (2 g, 8.6 mmol) to give 1.2 g (65%) of 19a as a colorless oil. TLC Rf = 0.2 (hexane/EtOAc, 1:1). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 2.73–2.76 (t, J = 6.02, 6.02 Hz, 2H, CH2), 3.85–3.88 (t, J = 6.09, 6.09 Hz, 2H, CH2), 3.95 (s, 3H, COOCH3), 7.18–7.29 (m, 2H, Ar), 7.87–7.91 (t, J = 7.77, 7.77 Hz, 1H, Ar).

Methyl 3-Fluoro-4-(4-hydroxybut-1-yn-1-yl)thiophene-2-carbox ylate (19b).

Compound 19b was prepared using the general method described for the preparation of 19a,b from 17 (0.5 g, 7.13 mmol) and 18b (1.9 g, 7.42 mmol) to give 1.1 g (64%) of 19b as a yellow oil. TLC Rf = 0.33 (hexane/EtOAc, 1:1). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 2.70–2.73 (t, J = 6.23, 6.23 Hz, 2H, CH2), 3.83–3.86 (t, J = 6.23, 6.23 Hz, 2H, CH2), 3.80 (s, COOCH3), 7.46–7.47 (d, J = 4.15 Hz, 1H, Ar).

General Procedure for the Synthesis of Compounds 20a,b.

To 10% palladium on activated carbon (1:1 wt equiv) in a Paar flask, ethanol was added to quench. Methanolic solutions of alcohols 19a,b were added, and hydrogenation was carried out at 55 psi of H2 for 12 h. The reaction mixture was filtered through Celite, washed with MeOH, passed through a short silica gel column (3 cm × 5 cm), and concentrated under reduced pressure to give 20a,b as oils.

Methyl 2-Fluoro-4-(4-hydroxybutyl)benzoate (20a).

Compound 20a was prepared using the general method described for the preparation of 20a,b from 19a (1.2 g, 5.4 mmol) to give 1.17 g (96%) of 20a as a colorless oil. TLC Rf = 0.2 (hexane/EtOAc, 1:1). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 1.57–1.79 (m, 4 H, CH2CH2), 2.67–2.71 (t, J = 7.60, 7.60 Hz, 2 H, CH2), 3.65–3.69 (t, J = 6.37, 6.37 Hz, 2 H, CH2), 3.92 (s, 3 H), 6.95–6.99 (d, J = 1.32 Hz, 1 H, Ar), 7.01–7.04 (dd, J = 1.50, 8.02 Hz, 1 H, Ar), 7.83–7.87 (t, J = 7.84, 7.84 Hz, 1 H, Ar).

Methyl 3-Fluoro-4-(4-hydroxybutyl)thiophene-2-carboxylate (20b).

Compound 20b was prepared using the general method described for the preparation of 20a,b, from 19b (1.1 g, 4.54 mmol) to give 1.1 g (98%) of 20b as a yellow oil. TLC Rf = 0.33 (hexane/EtOAc 1:1). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 1.39–1.46 (td, J = 6.47, 6.47, 13.30 Hz, 2 H, CH2), 1.54–1.62 (td, J = 7.63, 7.63, 15.45 Hz, 2 H, CH2), 3.80 (s, 3 H, COOCH3), 3.38–3.42 (dd, J = 6.32, 11.63 Hz, 2 H, CH2), 7.65–7.67 (d, J = 4.80 Hz, 1 H, Ar).

General Procedure for the Synthesis of Compounds 21a,b.

To acetonitrile, periodic acid (2.65 equiv) was added and stirred for 15 min. To this solution at 0 °C (in an ice−water bath), compounds 20a,b (1 equiv) were then added followed by the addition of PCC (0.03 equiv). The mixture was then stirred for 6 h until no starting material was detected on TLC. The solvent was evaporated in vacuo to give a residue, which was dissolved in EtOAc, washed successively with brine−water, satd aq NaHSO3 solution, and brine, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, and concentrated to give 21a,b as oils.

4-(3-Fluoro-4-(methoxycarbonyl)phenyl)butanoic Acid Benzoate (21a).

Compound 21a was prepared using the general method described for the preparation of 21a,b from 20a (1.17 g, 5.17 mmol) to give 1.2 g (97%) of 21a as a colorless oil. TLC Rf = 0.58 (hexane/EtOAc 1:1). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 1.97–2.04 (m, 2 H, CH2), 2.39–2.43 (t, J = 7.31, 7.31 Hz, 2 H), 2.72–2.76 (m, 2 H, CH2), 3.94 (s, 3 H, COOCH3), 6.98–7.01 (d, J = 1.23 Hz, 1 H, Ar), 7.04–7.07 (dd, J = 1.37, 8.01 Hz, 1 H, Ar), 7.87–7.91 (t, J = 7.82, 7.82 Hz, 1 H, Ar).

4-(4-Fluoro-5-(methoxycarbonyl)thiophen-3-yl)butanoic Acid (21b).

Compound 21b was prepared using the general method described for the preparation of 21a,b from 20b (1.4 g, 6 mmol) to give 1.2 g (79%) of 21b as a yellow oil. TLC Rf = 0.58 (hexane/EtOAc 1:1). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 1.94–2.01 (td, J = 7.34, 7.34, 14.47 Hz, 2 H, CH2), 2.41–2.45 (t, J = 7.29, 7.29 Hz, 2 H), 2.62–2.66 (t, 2 H, CH2), 3.91 (s, 3 H, COOCH3), 7.11–7.21 (d, J = 4.29 Hz, 1 H).

General Procedure for the Synthesis of Compounds 22a,b.