Abstract

HIV testing uptake continues to be low among Female Sex Workers (FSWs). We synthesizes evidence on barriers and facilitators to HIV testing among FSW as well as frequencies of testing, willingness to test, and return rates to collect results. We systematically searched the MEDLINE/PubMed, EMBASE, SCOPUS databases for articles published in English between January 2000 and November 2017. Out of 5036 references screened, we retained 36 papers. The two barriers to HIV testing most commonly reported were financial and time costs—including low income, transportation costs, time constraints, and formal/informal payments—as well as the stigma and discrimination ascribed to HIV positive people and sex workers. Social support facilitated testing with consistently higher uptake amongst married FSWs and women who were encouraged to test by peers and managers. The consistent finding that social support facilitated HIV testing calls for its inclusion into current HIV testing strategies addressed at FSW.

Keywords: HIV diagnosis, HIV testing, Female sex workers (FSWs), Systematic review

Resumen

La aceptación a realizar las pruebas de VIH continúa siendo baja entre las Mujeres Trabajadoras Sexuales (MTS). Nosotros sintetizamos evidencias sobre las barreras y las facilidades para realizar las pruebas de VIH entre las MTS, así como sobre las frecuencias de la prueba, voluntad de evaluar y tasa de retorno para recoger los resultados. Se realizaron búsquedas sistemáticas en las bases de datos MEDLINE/PubMed, EMBASE,SCOPUS para artículos publicados en inglés entre enero del 2000 y noviembre de 2017. De 5036 referencias examinadas, elegimos 36 artículos. Las dos barreras más comunes para las pruebas de VIH fueron los costos financieros y de tiempo, incluyendo: bajos ingresos, costos de transporte, limitaciones de tiempo y pagos formales/informales, así como el estigma y la discriminación atribuidos a las personas y trabajadoras sexuales seropositivas. El apoyo social facilitó las pruebas de VIH con una mayor aceptación entre las MTS casadas y las mujeres a quienes sus compañeros y gerentes les animaron a realizarlas. El hallazgo consistente en que el apoyo social facilitó las pruebas de VIH requiere su inclusión en las estrategias actuales de pruebas de VIH realizadas en MTS.

Introduction

Worldwide, early HIV testing is a public health priority especially among key populations such as female sex workers (FSWs) [1–3]: out of the estimated 33 million people living with HIV in the world, 19 million do not know their status [1]. Early HIV diagnosis has gained significant attention within key global health institutions, including the Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and the recently established 90-90-90 targets [4]. It is proposed that by 2020, 90% of all people living with HIV should know their HIV status, 90% of all people with diagnosed HIV should receive sustained antiretroviral treatment, and 90% of all people receiving antiretroviral treatment should reach viral suppression [4]. Historically, HIV prevention efforts focused on key populations, including sex workers, as an effective approach to reduce HIV transmission, particularly in the early phase of the epidemic [5].

Several systematic reviews have examined HIV prevalence [6–8] and effectiveness of different HIV prevention interventions for SWs [9–12]. Shahmanesh et al. presented evidence for the efficacy of multi-component interventions, and⁄or structural interventions [9]. A Cochrane review of behavioral interventions concluded that, compared with standard care or no intervention, behavioral interventions are effective in reducing HIV and the incidence of STIs amongst FSWs [10]. A systematic review of community empowerment interventions in low- and middle-income countries demonstrated significant protective combined effect for HIV infection (prevalence), STIs such as gonorrhea and chlamydia, and increase of consistent condom use with all clients [12]. A systematic review of community empowerment interventions in generalized and concentrated epidemics has shown their positive impact on HIV prevalence, estimated number of averted infections among SWs and adult population, and expanded coverage of ART [11]. These previous studies did not systematically assess HIV testing approaches, but rather examined the combined effect of a variety of prevention activities. Thus, they failed to address unique determinants of different HIV testing approaches.

HIV testing activities among sex workers were assessed in only two papers including a meta-analysis of community-based approaches [13], and a study of barriers to HIV testing in Europe [14]. According to these studies, community-based HIV testing leads to higher HIV testing rates than facility-based testing, and the most common barriers to HIV testing are low-risk perception, fear and worries, poor accessibility to healthcare services, health providers’ reluctance to offer the test, and scarcity of financial and human resources. Still, neither of those studies focused on FSWs nor systematically reviewed unique facilitators and barriers to HIV testing faced by this group. The present review compiles existing evidence on HIV testing among FSWs in order to better meet the needs of this group while implementing the first target of the 90-90-90 strategy. Our specific objectives are: (1) to summarize data on key barriers and facilitators to HIV testing among FSWs, and (2) to systematically review frequencies of testing, willingness to test, and return rates to collect HIV test results in this population.

Methods

We applied a free text strategy and MeSH terms to systematically scan the electronic databases MEDLINE/PubMed using the platform OVID, and EMBASE and SCOPUS. We employed a combination of terms that covered the concepts ‘HIV’, ‘Sex work’ and ‘Test’. We conducted several scoping searches to identify the most efficient search strategy, which we provide in “Annex 1: Search strategy”. Guidelines, reports and policy documents were searched using Google Scholar and employed to inform the discussion of findings. We exported all identified references (5036) into the bibliographic management software ENDNOTE X7.

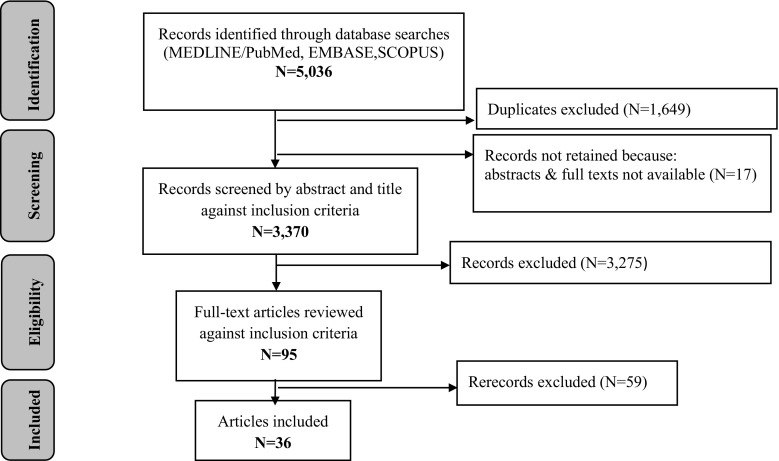

The first author (AT) screened titles and abstracts against the following inclusion criteria: (1) published in a peer-reviewed journal between January 2000 and November 2017; (2) written in English; and (3) presenting data on HIV testing among FSWs. We excluded duplicates and studies for which no abstract or full text was available (N = 17). After reviewing the full text of 95 pre-selected articles against the above mentioned inclusion criteria, 36 papers were retained for a more detailed review. The first author extracted data systematically using a standardized form that included information on the period of study, location, study population, design, research questions, key findings, and conclusions (“Annex 2: Data extraction form”). Next the quality of qualitative papers was assessed using the guide for critically appraising qualitative research by Spencer et al. [15]. The modified Downs and Black checklist was applied to quantitative and mixed-methods papers [16]. We used a midpoint score of 9 for qualitative papers and 12.5 for quantitative ones as a cut off between low- and high-quality studies. Overall, two quantitative papers with score of 10 [18] and 9 [17] points failed to meet the criteria; three papers received 12 points [19, 20]. The vast majority of quantitative papers lacked information needed for assessment. We were unable to appraise four abstracts: three, for the limited data presented, and one, being a mathematical modeling paper [21] that did not fit well with the quality appraisal tools employed. We decided to include all papers into the review in order to provide a comprehensive picture; at the same time, we considered it important to stress the results of the quality assessment (“Annex 3: Quality assessment”). The results of the search and screening process are described in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow chart of citations

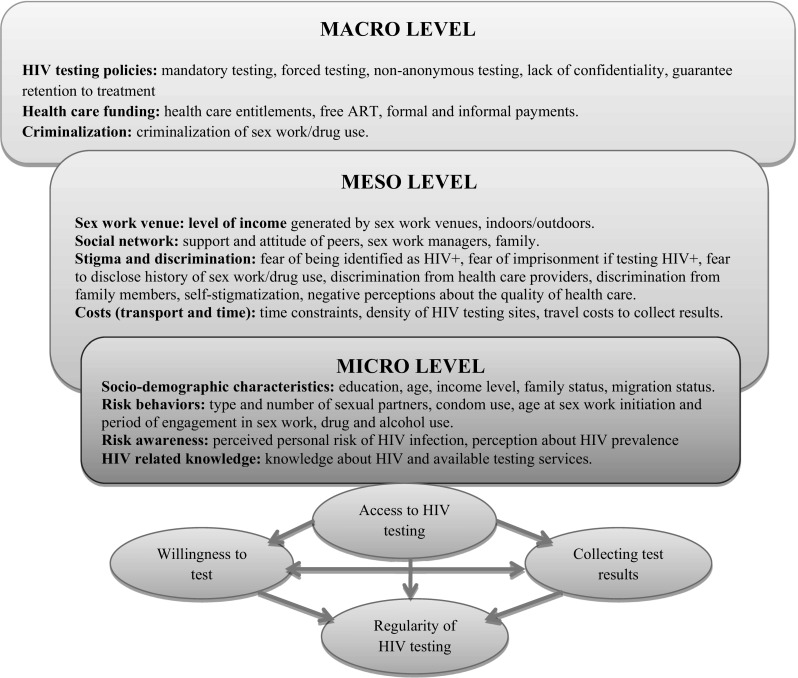

Guided by the socio-ecological model (SEM) developed by Blanchard et al. [22] we classified data into three levels: macro-, meso-, and micro-level factors (Table 1). The macro level consisted of economic and policy factors. The meso level included social networks, organizations, cultural norms, and values. The micro level included individual socio-demographic characteristics, knowledge, risk awareness, and behavioral factors. We also extracted data on previous experiences of HIV testing and ways to encourage uptake. The PRISMA check list is provided as “Annex 4: PRISMA 2009 Checklist”.

Table 1.

Overview of selected studies

| Study reference | Location | Study population (N, population group) | Study design | HIV testing uptake | Micro-level factors | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barriers | Facilitators | |||||

| 1. Aho et al. [26] | Guinea | N = 421 FSWs |

Mixed (QN,CS & QL) | Ever tested:26.6% Acceptance:100% Collected result:92.3% |

n/a | Higher perceived risk |

| 2. Ameyan et al. [47] | Ethiopia | N = 20 FSWs N = 3 community counsellors N = 3 HCWs N = 3 program managers N = 2 hotel owners |

QL | n/a | Lower perceived risk | Young age HIV knowledge Pregnancy, children |

| 3. Batona et al. [28] | Benin | N = 450 FSWs |

QN,CS | Ever tested:87% Past year::65.3% Past 3 months:40% 3–6 months:21% Acceptance:98.9% Willing:69.4% |

n/a | Previous testing Having kids |

| 4. Beattie et al. [48] | India | N = 302 FSWs = 125 MSM = 56 TSG = 6 Female peer educators = 87 Male peer educators = 28 |

QL | n/a | No ill health symptoms Poor VCT knowledge |

Improved quality &duration of life (ART) Having kids |

| 5. Bengtson et al. [27] | Kenya | N = 818 FSWs |

QN, CS | Ever tested:88.6% Never tested:11% Every 3 months:45% Every 6 months:15% Every 1–3 months:12% Once:16% |

31 years and older Less than 7 years of SW Alcohol use |

Having kids |

| 6. Burke et al. [54] | Uganda | N = 88 N = 11 FSWs N = 10 Fish men/boat owners N = 12 HCWs N = 55 community members |

QL | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| 7. Chanda et al. [49] | Zambia | N = 40 FSWs |

QL | n/a | n/a | Pregnancy Protecting one’s child Seeking birth control Family planning Higher HIV knowledge |

| 8. Chiao et al. [45] | Philippines | N = 980 FSWs (baseline) N = 903 FSWs (post test) |

QN, randomized quasi-experimental | n/a | n/a | Older age Better educated Longer employed in SW Regular SP Higher income Higher HIV knowledge Higher perceived risk |

| 9. Dandona et al. [18] | India | N = 6648 FSWs |

QN,CS | Ever tested:7.9% Unwilling:73% |

16–17 years old Low income |

Engaged in SW > 5 years Higher income |

| 10. Deering et al. [37] | Canada | N = 291 SWs |

QN,CS | Past year: 69.4% | n/a | n/a |

| 11. Deering et al. [25] | Canada | N = 435 SWs |

QN,CS | Ever tested:87.4% Past year:76.1% |

Migrant/new migrant Language barriers |

Older age of SW initiation Aboriginal ancestry Inconsistent condom use with clients Injecting drugs Contact with nursing program |

| 12. Dugas et al. [29] | Benin | N = 66 FSWs N = 24 HCWs |

QL | Every 6 months:46% Never tesed:26% |

No symptoms Migration Language barriers |

n/a |

| 13. Grayman et al. [30] | Vietnam | N = 610 FSWs | QN,CS | Ever tested:30.9% | Never married 5 or fewer clients per week |

n/a |

| 14. Hong et al. [31] | China | N = 1022 FSWs | QN,CS | Ever tested:48% | Lower perceived risk Inconsistent condom use with client/stable SP Poor VCT knowledge |

Higher HIV knowledge Older age Low education |

| 15. King et al. [46] | Russia | N = 29 FSWs |

QL | Ever tested:100% | Drug use Poverty |

Having money |

| 16. King et al. [46] | Russia | N = 139 FSWs | QN,CS | n/a | Older age Longer duration of drug use |

n/a |

| 17. King et al. [34] | Russia | N = 139 FSWs N = 29 FSWs |

Mixed (QN,CS& QL) | Ever tested: 97–100% | Drug use Drug use for ≥ 4 years Poor knowledge where to test |

Higher HIV knowledge Perceived risk High HIV incidence Knowing someone who is HIV+ Wanting to protect others (children, parents) |

| 18. Johnston et al. [40] | Dominican Republic | N = 2781 FSWs |

QN, CS | Past year: 16.6–30.8% | n/a | Higher HIV knowledge Regular HC checks- |

| 19. Ngo et al. [50] | Vietnam | N = 30 FSWs (in-depth interview) N = 94 FSWs (FGDs) |

QL | n/a | Poor VCT knowledge Perceived risk |

Fear of HIV Visual STI symptoms Drug use of intimate SP |

| 20. Nhurod et al. [43] | Thailand | N = 1006 FSWs | QN,CS | Acceptance:91.2% collected result:at clinic-100% at mobile point-14.8% |

n/a | n/a |

| 21. Park et al. [38] | China | N = 348 FSWs |

QN,CS | Past year:22% | n/a | Higher HIV knowledge Participation in HIV prevention program Income Education Regular STI checks |

| 22. Parriault et al. [17] | Boarder between Brazil and French Guiana | N = 213 FSWs |

QN, CS | Never tested: 31% | Older age HIV knowledge Poor knowledge where to test Lower perceived risk |

n/a |

| 23. Sayarifard et al. [36] | Iran | N = 128 FSWs | QN,CS | Past year:25% | Poor knowledge | n/a |

| 24. Scorgie et al. [52] | four countries of east and southern Africa (Kenya, Zimbabwe, Uganda and South Africa) | N = 106 FSWs N = 26 MSWs N = 4 TSG | QL | n/a | Poor VCT knowledge | n/a |

| 25. Shokoohi et al. [35] | Iran | N = 1005 FSWs | QN, CS | Past year 27.5% | n/a | Older age at first SW HIV knowledge Knowledge where to test Injecting drugs ever in life Receiving free condoms during 12 months Higher perceived risk |

| 26. Shokoohi et al. [39] | Iran | N = 1337 FSWs |

QN, CS | Ever tested:80.6% Past year 70.4% |

n/a | Higher educational level Higher HIV knowledge Knowledge of where to test More than 5 paying SP More than one none-paying SP Consistent condom use Receiving HR services Health service utilization Higher perceived risk |

| 27. Simonovikj et al. [53] | Macedonia | N = 106 SWs | Case report | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| 28. Todd et al. [32] | Uzbekistan | N = 448 FSWs | QN,CS | Ever tested:83.9% | Younger age Initiated SW before age 18 Shared drugs with clients Consistent condom use with clients Shorter period of SW Fewer SP Poor VCT knowledge |

n/a |

| 29. Tran et al. [33] | Vietnam | N = 1998 FSWs | QN,CS | Ever tested: 34.4% ESWs 24.4%-SSWs Collected result:86.9% |

Ever injected drugs Having IDUs as clients Inconsistent condom use with non-commercial SP lover and husband) |

Duration of SW Inconsistent condom use with clients Higher HIV knowledge (information via communication campaign) Higher perceived risk |

| 30. Wang et al. [41] | China | N = 17 FSWs N = 12 pimps |

QL | Willing:88% | Poor HIV knowledge (receiving information through TV on decrease of HIV P) HIV negative-peers/friends Lower perceived risk Consistent condom use |

Higher risk awareness (receiving information through TV on increase of HIV P) Someone close diagnosed HIV+ Concerned about friends and family Concerned about one’s health |

| 31. Wang et al. [19] | China | N = 970 FSWs |

QN,CS | Willing:69% Unwilling:7.2% |

n/a | Married Engaged in SW for longer Higher VCT knowledge Higher perceived risk Condom use Leave SW Previous HIV testing |

| 32. Wang et al. [20] | China | N = 970 FSWs |

QN, Prospective cohort | Willing:69% Acceptance:11% |

Lower perceived risk | Engaged in SW > 12 months Condom use Willing to test Changing job |

| 33. Wanyenze et al. [51] | Uganda | N = 190 FSWs | QL | n/a | Poor HIV knowledge Misconceptions Limited awareness of services |

n/a |

| 34. Wilson et al. [21] | Australia | N = n/a SWs |

Mathematical model | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| 35. Xun et al. [42] | China | N = 371 MSM N = 405 FSWs N = 361 VCT clients |

QN,CS | Willing:72.1% -54.3% at home |

n/a | Willing to pay 4.8 USD for oral test Higher risk awareness |

| 36. Xu et al. [23] | China | N = 164 FSWs |

QN longitudinal |

Ever tested:32.1%-HIV+ , 16.1%-HIV− Collected result:47.8% |

n/a | More than 9 years of schooling Less than 5 clients per week Having a regular SP Drug use Pelvic pain during last 12 months Higher perceived risk |

| Study reference | Meso-level factors | Macro-level factors | Strategies to encourage HIV testing | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barriers | Facilitators | Barriers | Facilitators | ||

| 1. Aho et al. [26] | HIV stigma SW stigma Managers’ negative attitude |

Peer support | n/a | Free treatment | n/a |

| 2. Ameyan et al. [47] | HIV stigma and discrimination Time restriction Higher travel costs Negative attitude of HCWs Negative experience of peers/brothel owners |

Private hospitals Financial incentives |

Need to show ID Poor confidentiality |

Free treatment and other HC services | Involvement of brothel owners Involvement of media Media |

| 3. Batona et al. [28] | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| 4. Beattie et al. [48] | Fear of HIV+ result, HIV +status/SW disclosure Fear to leave the brothel (violence) Discrimination of FSWs/HIV+ Higher travel costs Time costs |

Peer support | Lack of confidentiality Bribes ID and retention Need to have retention “buddy” |

n/a | Peer educators |

| 5. Bengtson et al. [27] | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| 6. Burke et al. [54] | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | Self-testing |

| 7. Chanda et al. [49] | Fear of stigma and discrimination HIV stigma SW stigma Intimate partner violence Potential financial Time restrictions |

Community/close social network | Fear of poor confidentiality | n/a | Community empowerment Norm-changing interventions |

| 8. Chiao et al. [45] | n/a | Support from peers and managers | n/a | n/a | Education of peers and managers |

| 9. Dandona et al. [18] | Non-participation in self support group | Non street-based Participation in support group |

n/a | n/a | n/a |

| 10. Deering et al. [37] | n/a | High density of testing sites Lower travel costs |

n/a | n/a | n/a |

| 11. Deering et al. [25] | Indoor SW | n/a | Criminalization of SW | n/a | n/a |

| 12. Dugas et al. [29] | Fear of HIV+ test result Fear of SW disclosure Low quality of HC |

Peer-educators Pimps’ support |

n/a | n/a | Peer educators Home/work testing Community mobilization |

| 13. Grayman et al. [30] | n/a | n/a | n/a | Time ever spent in rehabilitation centre for drug addicts | n/a |

| 14. Hong et al. [31] | Fear of HIV+ status disclosure Fear of SW disclosure Higher time costs |

Working at high income venues | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| 15. King et al. [46] | Perceived low quality of public HC services Social marginalization |

Family support Having relatives employed as medical professionals Personal “connections” with HC system Referrals of NGOs More accessible private hospital |

Bribes Residence permit Fear of registration as drug user, STI patient or HIV+ in official medical records Need to give up possibility of anonymity Underfunding of HC Illegal SW |

Outreach program/referrals | Outreach with the referrals |

| 16. King et al. [46] | HIV stigma Refusal of medical care (IDUs, FSWs) |

SW stigma | Poor confidentiality | n/a | n/a |

| 17. King et al. [34] | Higher time and travel costs Fear of HIV+ test result SP reaction if tested HIV+ Stigma and discrimination |

Social support Perceived better conditions in private clinics |

Poor confidentiality High costs residence permit Fear of registration as drug user, STI patient or HIV+ in official medical records |

Free treatment Outreach van |

Outreach testing |

| 18. Johnston et al. [40] | n/a | Social support | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| 19. Ngo et al. [50] | Street based SW Higher time costs (waiting lists) Lack of money&time Fear of HIV+ result Fear to be recognized as SW Discrimination, unfriendly perceived low quality of public hospitals Fear of imprisonment if diagnosed HIV+ |

Venue-based SW Managers requirement to test Perceived high quality (no waiting, less of private) private HC facilities |

Poor confidentiality, HC costs at private hospitals | Less perceived discrimination at private clinics Free treatment Abortion, giving birth or rehabilitation centre for drug addicts |

Involvement of managers Peer-referrals |

| 20. Nhurod et al. [43] | Higher time costs Money needed to travel to collect test result check |

Required negative result to be employed as SW | n/a | n/a | Mobile VCT Rapid testing |

| 21. Park et al. [38] | n/a | SW venue | n/a | n/a | Cooperation of NGO and FSWs’ network |

| 22. Parriault et al. [17] | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| 23. Sayarifard et al. [36] | Fear of HIV+ result Fear of result disclosure |

n/a | Higher costs | n/a | Training program for FSWs |

| 24. Scorgie et al. [52] | Self-stigma Fear of HIV+ result Fear of isolation and discrimination Higher transportation costs |

NGO established clinic Perceived higher quality of private HC facilities |

Forced testing without consent Denial of testing Illegal SW |

n/a | Training of health providers Supporter or advocate in HC facilities Collective action of SWs |

| 25. Shokoohi et al. [35] | n/a | n/a | n/a | Rapid testing | |

| 26. Shokoohi et al. [39] | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | Referral’s Community-based outreach testing Self-testing |

| 27. Simonovikj et al. [53] | n/a | n/a | Cases of forced testing during police arrest | n/a | n/a |

| 28. Todd et al. [32] | n/a | n/a | Compulsory testing during police detainment Illegal SW Fees for testing and treatment |

n/a | Change in criminal law Guarantee anonymous testing Establishment of “friendly cabinets” |

| 29. Tran et al. [33] | n/a | n/a | 54% were tested voluntarily, other were forced | n/a | n/a |

| 30. Wang et al. [41] | Fear of HIV+ result Meeting friends at VCT sites Fear of HIV+ diagnosis Lack of confidentiality Fear of HIV + disclosure Fear of sex work disclosure Stigma Higher time costs |

Support from peers and managers | Fear of being quarantined Higher medical cost Mistrust in governmental free services |

n/a | Education information Dissemination |

| 31. Wang et al. [19] | Stigmatization and discrimination | Support from peers, family, and managers | n/a | Free treatment | Peer education -VCT promotion |

| 32. Wang et al. [20] | Stigmatization and discrimination SW disclosure |

Support from peers | n/a | Free treatment | Peer education |

| 33. Wanyenze et al. [51] | Fear of stigma and discrimination Unwelcoming attitude of HC workers and discrimination Stigmatization by fellow sex workers, families and the community Unfavourable opening hours of health facility The pace at which HIV services are delivered |

Social networks | Costs (“tips” to healthcare providers) Fear of breach of confidentiality Illegal SW |

Faster service delivery at private facilities | Use of media Establishing specific facilities or clinics for SWs Provision of health information on phones Motivation and sensitization of HC providers to work with FSWs |

| 34. Wilson et al. [21] | n/a | n/a | Mandatory HIV testing not cost effective | n/a | n/a |

| 35. Xun et al. [42] | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | Oral fluid test Home testing |

| 36. Xu et al. [23] | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

ART antiretroviral therapy, CS cross sectional, EES entertainment-based sex workers, FGDs focus group discussions, FSWs female sex workers, HC health care, HCWs healthcare workers, HIV human immunodeficiency virus, HIV P HIV prevalence, HR harm reduction, IDUs injection drug users, ID identity card, MSM men who have sex with men, MSWs male sex workers, NGO non-governmental organizations, SP sexual partner, STI sexually transmitted infections, SSWs street-based sex workers, SW sex work, TSG transgender, QN quantitative, QL qualitative, n/a non applicable, VCT voluntary counselling and testing

Results

Out of the 36 studies retained for review, most were quantitative (N = 20) and conducted in Asia (N = 18). Nine papers reported work conducted in Africa, three in Europe, three in Russia, and one in Macedonia. Three studies were conducted in Latin America, two in Canada and one in Australia. Eighteen studies were cross-sectional, and twenty-five focused exclusively on FSWs.

Previous Experience of HIV Testing

We summarized evidence on previous experience of HIV testing and approaches to facilitate testing (Table 1). Fifteen studies [17, 18, 23–35] focused on ever in life testing. The highest rate was reported in a study in Russia where all recruited FSWs (100%, N = 29) were tested [24] followed by Kenya (88.6%, N = 818) [27]. The lowest rate was reported in a study conducted in India (7.9%, N = 6648) [18]. Ten studies examined recent testing [25, 27–29, 35–40], which varied extensively from 76.1% in Canada (N = 435) [25] to 22% in China (N = 970) [38]. Six studies addressed willingness to test [18–20, 28, 41, 42], and this ranged from 88% (N = 17) in China [41] to 73.2% in India (N = 6648) [18]. Three studies reported that willingness facilitated actual HIV testing [20, 28, 41]. Only four studies assessed frequencies of collecting test results [23, 26, 33, 43], and these ranged widely from 92.3% in Guinea [26] to 14.8% in Thailand [43].

We identified a high variability of outcome measures employed in the studies reviewed. For example, the frequency of HIV testing was measured using different time frames and included “last month” and “recent testing” with a time period corresponding to “recent” that varied from 1 year to 1 month.

Conceptual Framework: Barriers and Facilitators of HIV Testing Amongst FSWs

In this study we employed an adapted version of the socio-ecological framework developed by Blanchard et al. [22] to organize and analyze our findings systematically. As shown in Fig. 2, we conceptualized HIV test uptake as the result of a number of interrelated factors that operate simultaneously at the micro, meso and macro levels. Most articles focused on the micro (N = 30) and meso (N = 24) levels, and about half of all papers addressed the macro (N = 19) level. Ten studies analyzed concurrently two levels of the social ecology, while nine addressed simultaneously the micro, meso, and macro levels.

Fig. 2.

Conceptual framework: barriers and facilitators of HIV testing amongst FSWs.

Reproduced with Permission from Blanchard et al. [22]

Micro-level Factors

Socio Demographic Characteristics

Sixteen articles focused on socio-demographic characteristics. We found no consistent associations [18, 27, 31, 32, 44–46] of education and age [23, 31, 45] with HIV testing uptake. Highly educated women in the Philippines and Iran were more likely to test [39, 45], but studies in China reported higher HIV testing uptake amongst women with both high [23] and low education level [31]. In two studies conducted in China and one in the Philippines, older age facilitated HIV testing [31, 44, 45], but in Russia, Ethiopia and Kenya older-aged FSWs [46, 47] and those aged + 30 [27] were less likely to test compared to younger FSWs. In Uzbekistan and India, younger age decreased testing [18, 32]. Higher income was associated with testing in India and the Philippines [18, 45] and in Russia poverty impeded access to healthcare, including HIV testing [24].

Ten studies reported that having children and/or being pregnant and/or being in a permanent relationship facilitated HIV testing [19, 23, 27, 28, 30, 34, 45, 47–49]. Married women in China [19] and those with a regular sexual partner in the Philippines [45] and in China [23] were more likely to test. According to a study conducted in Vietnam, unmarried women were less likely to test [30]. In Kenya, Zambia, Benin, Ethiopia, Russia and India, having children or being pregnant facilitated HIV testing [27, 28, 34, 47–49]. In Iran, incarceration was associated with recent testing [39].

In Canada and Benin, migrant FSWs [25, 29] had limited access to healthcare because of language barriers, which led to low HIV testing rates.

Risk Behaviors

Seven studies reported nearly inconsistent patterns on how regular condom use influenced HIV testing. Using condoms during every instance of each sexual intercourse both facilitated and impeded testing depending on the type of sexual partner [19, 20, 25, 31, 33, 39, 41]. Three articles reported that inconsistent condom use with a client -facilitated testing [25, 31, 33], but using condoms inconsistently with a husband or lover was negatively associated with testing [33]. In China, a quantitative study identified that condom use was associated with HIV testing [20], although in a previous qualitative study the same author found that FSWs who used condoms consistently felt to be sufficiently protected from HIV and not in need of testing [41]. In Iran, consistent condom use during each sexual intercourse was associated with recent testing [39].

Initiation of sex work at an older age [18, 20, 33, 35, 45] and engaging in sex work for a longer period of time [18, 20, 33, 45] facilitated HIV testing. In Uzbekistan, FSWs who started sex work before the age of 18 were less likely to test [32], and in Canada older age of sex work initiation was positively associated with recent testing [25]. FSWs who engaged in sex work for a longer time had a higher uptake of testing [18, 20, 33, 45] and willingness to test [19]. FSWs employed for shorter periods [27, 32] were less likely to test.

Having a lower number of clients/sexual partners was associated with HIV testing in China [23], but was reported to decrease testing in Vietnam [30], Iran [39] and Uzbekistan [32].

Most studies identified drug use and alcohol consumption to impede HIV testing [24, 25, 27, 32–34, 46]. Still, in Iran and Canada drug use among FSWs did not hinder testing [25, 35].

Risk Awareness

We reviewed thirteen articles that focused on individual perceptions towards HIV risks [19, 20, 23, 26, 31, 33–35, 39, 41, 45, 47, 50]. Low perceived risk was associated with lower likelihood to test [31, 45, 47], and FSWs would be less likely to test if they believed that HIV prevalence to be decreasing and no one in their social network was infected [41]. Conversely, high perceived risk was associated with HIV testing [19, 23, 26, 33–35, 39, 41, 45, 50].

HIV-Related Knowledge

Seventeen articles examined HIV knowledge, including knowledge of available HIV testing sites in the area [19, 29, 31, 33–36, 38–41, 45, 47–51]. FSWs who had heard prevention messages in HIV communication campaigns were more likely to test [33, 47, 51]. Similarly, FSWs were reluctant to test if they had poor HIV-related knowledge [29, 36, 41, 48, 49, 51] and were not well informed about local testing sites [31, 41, 48, 50–52].

Meso-level Factors

Sex Work Venue

Of the six articles that addressed sex work venues [18, 25, 31, 41, 45, 50], most reported that working indoors and at high-income venues generating higher income impelled HIV testing. Working in a high-income venue and out of the street predicted testing in China, Vietnam and India [18, 31, 50]. However, in Canada, FSWs working indoors were less likely to have recently tested for HIV than those working outdoors [25].

Social Support

About half of the articles reviewed assessed how FSWs’ social interactions influenced their decision to test for HIV [18–20, 24, 26, 29, 34, 38, 40, 41, 43, 45, 47–51]. Positive attitudes and support from peers, family and partners facilitated HIV testing [19, 20, 24, 26, 29, 34, 40, 41, 45, 48–51]. In China, women were more likely to test if accompanied by peers [19, 20]. In Russia, family support was an important condition for accessing healthcare, including HIV testing, as women could rely on their family financially and emotionally [24]. Participation in self-support groups in India [18] and Uganda [51] and receiving condoms from HIV prevention programs in China [38] facilitated testing. Positive views of FSWs’ employers towards HIV testing [41, 45] or requiring the test [43, 50] increased the uptake. However, in China and Ethiopia, employers expressed concerns towards HIV testing and how it could impact the sex work business [41, 47]. In Guinea, HIV testing was forbidden by some managers [26]. In Zambia and Russia, fear of negative reaction of their sexual partner if diagnosed HIV-positive, prevented women from engaging in HIV testing [34, 49].

Stigma and Discrimination

A total of fourteen articles focused on stigma and discrimination of HIV+ people and/or sex workers [20, 24, 26, 29, 31, 34, 36, 41, 46–52]. Fears of being identified as HIV+ [24, 26, 31, 34, 36, 41, 47–51] or as a sex worker [20, 26, 31, 34, 41, 46–52] were reported as barriers to testing in a number of studies. FSWs could refuse HIV testing [29, 36, 41, 48, 50, 52] or fail to collect test results [48] if afraid of receiving an HIV+ diagnosis.

In Benin, healthcare workers reported that women did not like to be recognized as FSWs, and that this could prevent them from seeking healthcare [29]. In several African countries, health providers discriminated against sex workers and their family members [52]. In Russia, FSWs were concerned that they would be treated badly or denied healthcare if identified as sex workers or drug users [46]. In China, FSWs worried about meeting an acquaintance at the testing site and being recognized as HIV+ [41], while in Vietnam, they feared imprisonment if diagnosed with HIV [50]. Self-stigma resulting from widespread negative views of HIV+ people and sex work decreased testing across several African countries [52]. Thirteen articles reported that anticipated stigma and discrimination at health facilities hampered service utilization [19, 20, 24, 26, 29, 37, 41, 46, 48–52]. In Russia, Vietnam, Uganda and several African countries, private hospitals were defined by FSWs as more friendly and of higher quality than public health facilities, and were reported to be preferable places to get healthcare services, including HIV testing [24, 50–52].

Time and Transport Costs

Eleven articles reported that time and transport costs hampered access to healthcare [24, 31, 34, 36, 37, 41, 43, 47, 49–52]. Time restraints impeded testing in China [31, 41], India [48], Thailand [43], Vietnam [50], Uganda [51], Zambia [49], Ethiopia [47] and several other African countries (Kenya, Zimbabwe, Uganda and South Africa) [52]. In Uganda, Zambia and Russia, FSWs expressed dissatisfaction with opening hours of health facilities as they did not correspond with women’s schedules and caused financial and time loss [34, 49, 51]. In Canada, higher density of testing sites and little time needed to get there were associated with having tested recently [37]. In Thailand, travel costs were reported to prevent users from collecting their HIV test results [43].

Macro Level Factors

HIV Testing Policies

Eleven articles focused on HIV testing policies [21, 24, 32, 34, 41, 46–48, 50–52] pointed to shortcomings in the range of services that should be provided together with HIV testing. These include informed Consent, Confidentiality, Counseling, Correct test results, and Connection to care and treatment, known as the “5 Cs” principles [3].

In China [41], Vietnam [50], India [48], Uganda [51], Zambia [49], Ethiopia [47] and Russia [46], lack of confidentiality was reported as a major barrier to HIV testing. Unwillingness to be included in official registers of HIV+ people decreased access to testing in China [41] and Russia [24]. In Russia, FSWs without a residence permit or passport are not entitled to accessing healthcare. Free-of-charge HIV testing is available only upon giving up anonymity, and if a woman utilizes state-sponsored HIV testing at a local clinic, the results are officially recorded into her personal medical records [24]. In India and Ethiopia, to access HIV and AIDS treatment, women are required to show an identity card [47, 48]. In Uganda, all women diagnosed HIV positive were given two papers indicating test result and further referrals while all diagnosed HIV negative were given one paper with test result only [51].

FSWs were forced to test against their will or were tested surreptitiously without consent in Kampala (Uganda), Hillbrow and Limpopo (South Africa) [52] and during police detainment in Uzbekistan [32] and Macedonia [53]. In Vietnam, among the FSWs who tested for HIV, only 54% did it voluntarily [33]. FSWs who had spent time in rehabilitation or detention centers [24, 30, 50] or had ever been pregnant [24, 50] were more likely to have undergone HIV testing. In Victoria, Australia, screening of sex workers is mandatory despite its lack of cost-effectiveness [21].

Healthcare Funding

Eleven articles reported how limited healthcare funding decreased HIV testing [19, 20, 24, 26, 32, 36, 41, 48, 50–52]. High medical care costs in China [41], Iran [36], several African countries (Kenya, Zimbabwe, Uganda and South Africa) [52] and informal payments in Russia [24], Uganda [51] and India [48] reduced access to healthcare, including testing. Five articles suggested that free treatment might increase testing [19, 20, 26, 47, 50].

Criminalization

Eight studies reported how current criminalized approaches to sex work and drug use inhibited FSWs from accessing healthcare [24, 25, 27, 32, 34, 51, 52, 54]. Sex work criminalization in Kenya, Zimbabwe, Uganda and South Africa, Canada, Uzbekistan and Russia [24, 25, 27, 32, 51, 52, 54] and fear of registration as a drug-user in Russia [24, 34] are seen to have hampered access to healthcare, including testing.

Testing Modalities

A total of twenty studies examined different ways to encourage HIV testing among FSWs including self-testing [39, 54], home-based [25, 29, 42], rapid testing [35, 43], work-based [29], oral fluid tests [42], “friendly cabinets” (newly established anonymous testing centers) at public STI clinics [32, 51], mobile services [43], outreach with referrals [24, 34, 39], community mobilization [29, 52], community empowerment [49] and involvement of peers, managers and healthcare workers [19, 20, 39, 45, 47, 49–52]. In one study examining hypothetical circumstances around self-testing, participants reported to anticipate significant benefits (entire privacy, avoiding travel and time costs, ability to test before sex early diagnosis), although these same features raised concerns when associated with lack of supportive counseling and linkage to care [54].

These studies suggest that HIV testing might increase if FSWs can easily access testing sites and receive support from peers, friends and healthcare workers along with educational activities [19, 20, 45, 50–52].

Discussion

This systematic review of barriers and facilitators to HIV testing amongst FSWs found that the two barriers to HIV testing most commonly reported are (1) costs, including transportation, formal/informal payments, and time, and (2) stigma, including fear of involuntary disclosure of HIV status/history of sex work, negative attitudes of healthcare workers, and discriminatory policies. Social support facilitated HIV testing, with consistently higher uptake amongst married FSWs, and those encouraged to test by peers, healthcare workers or employers.

The majority of the studies reviewed were conducted in low and middle-income countries with only three studies identified in high-income settings. Only one study evaluated the cost-effectiveness of HIV testing amongst FSWs. Most studies addressed micro, or micro and meso levels of the SEM with predominance of micro-level factors. Thirteen studies analyzed concurrently the macro, meso and micro levels. Our findings support previous calls to develop HIV testing strategies that fully account for structural factors [55, 56] and highlight the need for a more nuanced investigation of how micro-, meso- and macro-level factors intersect to influence HIV testing uptake.

Few studies assessed frequencies of collecting test results or compared them with testing frequencies. The outcome most frequently assessed was “ever in life” testing although this outcome measure fails to capture the frequency of HIV testing. Furthermore, the highest percentage of recently tested FSWs was reported by a Canadian study and constituted 76.1%, an outcome too low to meet either WHO recommendations [3, 57] or the “90-90-90” target [1], which highlights necessity to increase efforts to promote HIV testing amongst FSWs. Taken together, our results suggest addressing simultaneously several outcome measures when assessing HIV testing programs among female sex workers, including accessibility of testing, willingness to be tested, regularity and collecting test results.

In line with previous studies of HIV testing behavior of different populations [14, 58, 59], we found that scarcity of financial resources, low perceived risk and poor HIV knowledge were barriers to HIV testing for FSWs.

Similar to the results reported for female migrants [58], we observed an association between having children and HIV testing uptake. This might be manifestation of women’s and particularly pregnant women’s greater exposure to HIV testing, as an offer of HIV testing became generally the norm in reproductive and antenatal care settings [3, 60]. On the other hand, several papers reviewed suggested that women in permanent relationships and with children might have higher motivation to stay healthy and thus, might seek out testing themselves. For example, in Vietnam, FSWs in permanent relationships were more likely to be tested in the year 2000 before HIV testing became widely implemented as a part of national antenatal health care program across the country [61]. Overall, social support from family, peers, sex work managers and healthcare workers are instrumental for promoting HIV testing uptake among FSWs, yet the same sources might contribute to further stigma and discrimination.

We did not find any consistent associations between age of participants [58] or their educational level [58, 59] and HIV testing, but working in the sex industry for a longer period and starting sex work at older ages were associated with higher HIV testing uptake. These findings suggest that the willingness to test for HIV might increase with time and relate closely with HIV risk awareness.

The inconsistency of results on how condom use and number of clients influenced testing might be explained by FSWs’ engagement in different types of concurrent sexual partnerships. While using condoms with commercial clients might be perceived as prevailing acceptable behavior [62], the decision to use a condom in cohabiting relationships or with a husband might be influenced by interpersonal factors related to partnership intimacy (e.g., trust, emotional closeness, power or reproductive desires) [63]. Moreover, there is a need to account not only for the type of partnerships, but also for their duration. Consistency of condom use might decrease with longer duration of relationships with non-paying partners [63], but may increase with commercial permanent partners [64]. The relationship intimacy may be at play in the HIV testing decision-making process among FSWs and for consistent condom use. Testing behavior might be influenced by increased trust, emotional closeness and familiarity. A more nuanced understanding of how HIV testing behavior is influenced by risky sexual behaviors in different types of partnerships and how it changes over time is needed. In turn, relationship power might be an important modifiable factor, which might be considered when developing HIV testing interventions for FSWs.

The inconsistencies between results in relation to sexual/drug use behavior and HIV testing might be due to differences in targets of HIV testing approaches across countries. For example, in Canada efforts were concentrated on reaching street-based sex workers and those injecting drugs, leaving out those working indoors, in more high-income venues. Nevertheless, at that time sex work was fully decriminalized in Canada [65]. In contrast, in Uzbekistan and Russia HIV testing might be less accessible for sex workers and drug users because of punitive laws. In these countries, HIV testing is provided solely through government-affiliated settings, including so-called “friendly cabinets” and thus, sex workers and drug users might avoid state clinics or at least avoid disclosing who they are, as they might be stigmatized by healthcare providers or even arrested. Our results demonstrate how laws might diminish promising health-promoting interventions in some countries while in others, supporting policies and concentrated efforts might lead to the successful enrolment of most vulnerable populations.

Furthermore, factors, such as violations of human rights when forcing FSWs to test, lack of confidentiality and anonymity, discriminatory attitudes of healthcare workers, fear of testing HIV+ and being identified as a sex worker and/or a drug user, are manifestations of prevailing stigma. Unfortunately, there are still cases where the violation of basic human rights is “justified” and sex workers are perceived as victims and objects of pity, who should be helped when applying mandatory or forced testing. Our findings highlight the importance to tackle overlapping stigma and discrimination across all three levels of SEM in order to promote HIV testing among sex workers [66]. This is in line with the WHO’s call to enforce the 5 Cs principles and to institutionalize policies preventing discrimination and promoting tolerance towards sex workers and people living with HIV [61, 67]. As reported before, introduction of discriminative laws and policies criminalizing sex work and/or HIV transmission may fuel stigma [65, 68–70].

This review has several limitations. It is restricted to studies published in English, but only three pre-selected studies were excluded for this reason, so the impact upon the findings is likely to be minimal. We included studies published during the last 17 years to account for recent HIV testing approaches. It is unlikely that the content of previously published articles would have substantially altered our findings, as rapid HIV testing started in the early 2000s. We excluded eight citations with neither abstract, nor title available. We acknowledge that our findings are based on the topics presented by the selected studies, and thus, are restricted by the reported information. Despite the limitations mentioned above, this study provides a broad overview of the different aspects of HIV testing across the global SEM, provides important insights on how HIV testing uptake could be promoted among FSWs, and suggests avenues for further research.

Conclusion

The consistent finding that social support facilitated HIV testing calls for the inclusion of meso- level factors into current HIV testing strategies directed at FSW. Studies on the role of macro-level factors and their intersections with the meso and micro levels are needed to inform interventions that facilitate HIV testing uptake amongst FSWs.

Acknowledgements

AT was financed by the TransGlobal Health Program as a part of the Erasmus Mundus Joint Doctorate Programme. MR received funds from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (MINECO) as part of a “Ramon y Cajal” fellowship (RYC-2011-08428), and the Agència de Gestió d’Ajuts Universitaris i de Recerca, Regional Government of Catalonia (AGAUR Grant 2014SGR26). I would like to thank Jacob Osborne, MSc Research Master Global Health, for his help with editing this paper. I would like to thank Alyona Mazhnaya, Department of Health, Behavior & Society, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Baltimore, USA, for helping with updating search. ISGlobal is a member of the CERCA Programme, Generalitat de Catalunya.

Annex 1: Search Strategy

| HIV (human Immunodeficiency virus) (AND combined with) |

HIV testing/test/tested (AND combined with) |

Sex work (AND combined with) |

|---|---|---|

| OR acquired immunodeficiency syndrome OR AIDS | OR voluntary counselling and testing OR VCT | OR people who sell sex |

| OR HIV OR human immunodeficiency virus |

OR provider initiated testing and counselling OR PITC | OR sex industry/sex business |

| OR provider initiated counselling and testing OR PICT | OR prostitution | |

| OR diagnostic/diagnosed | OR FSW OR female sex workers | |

| OR screening/screened | OR CSW OR commercial sex workers | |

| OR routine testing, Opt-In, Opt-Out | OR sex services | |

| OR positive result | OR escort services | |

| OR testing and counselling OR HTC | OR paid sex | |

| OR transactional sex |

The final search strategy was defined as:

Search terms for HIV;

Search term for Sex workers;

Search term for HIV testing;

1 AND 2 AND 3.

Date of search: 03/November/2017;

Searched fields: abstract, key words, subject headings, title;

Databases searched:

- Results: Ovid MEDLINE(R)-1,877studies

- Embase-2516 studies

- SCOPUS-2591 studies

HIV.ab,kw,sh,ti.

AIDS.ab,kw,sh,ti.

Human Immunodeficiency virus.ab,kw,sh,ti.

Acquired Immunodeficiency syndrome.ab,kw,sh,ti.

1 or 2 or 3 or 4

“test* “.ab,kw,sh,ti.

“counsel* “.ab,kw,sh,ti.

HTC.ab,kw,sh,ti.

VCT.ab,kw,sh,ti.

(Voluntary counsel* and test*).ab,kw,sh,ti.

(Provider Initiated test* and counsel*).ab,kw,sh,ti.

PITC.ab,kw,sh,ti.

PICT.ab,kw,sh,ti.

(Provider Initiated counsel* and test*).ab,kw,sh,ti.

“diagnos* “.ab,kw,sh,ti.

“screen* “.ab,kw,sh,ti.

“Routine test* “.ab,kw,sh,ti.

Opt-In.ab,kw,sh,ti.

OPt-Out.ab,kw,sh,ti.

Positive results.ab,kw,sh,ti.

6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20

“Sex* work* “.ab,kw,sh,ti.

“people who sell sex* “.ab,kw,sh,ti.

“sex* industry “.ab,kw,sh,ti.

“sex* business “.ab,kw,sh,ti.

“sex* service* “.ab,kw,sh,ti.

“prostitut* “.ab,kw,sh,ti.

“female sex* work* “.ab,kw,sh,ti.

“commercial sex* work* “.ab,kw,sh,ti.

“Escort* service* “.ab,kw,sh,ti.

“paid sex* “.ab,kw,sh,ti.

“transactional sex* “.ab,kw,sh,ti.

“FSW* “.ab,kw,sh,ti.

“CSW* “.ab,kw,sh,ti.

22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27 or 28 or 29 or 30 or 31 or 32 or 33 or 34

5 and 21 and 35

(“2000” or “2001” or “2002” or “2003” or “2004” or “2005” or “2006” or “2007” or “2008” or “2009” or “2010” or “2011” or “2012” or “2013” or “2014” or “2015” or “2016” or “2017”).yr.

36 and 37

Annex 2: Data Extraction Form

| Title |

| Date published |

| Date of research |

| Authors |

| Study design |

| Research objectives/research questions |

| Country |

| Study population |

| Main methods of research |

| Main results |

| Main conclusions |

| Comments*(if needed) |

Annex 3: Quality Assessment

The quality of the qualitative papers (Table 1) was assessed using the guide for critically appraising qualitative research [15].The checklist consisted of 18 items assessing findings, design, sample, data collection, analysis, reporting, reflexivity and neutrality, ethics and auditability. As in previous research [66] we used a midpoint score of 9 as a cut off between low- and high-quality studies.

We assessed the quality of the quantitative and mixed-methods papers using the modified Downs and Black checklist [16]. The 26 questions of the checklist represented items of reporting, external and internal validity, and power. As the majority of studies did not report power calculations of the sample size and none was single or double blinded, we excluded the power (#27) and the blinding (#13, 14) questions. Thus, the modified checklist consisted of 24 questions with a maximum score of 25 points). A midpoint score of 12.5 was considered to distinguish the high-quality studies (Table 2).

Table 2.

Quality assessment of the 36 studies

| Study reference | Study design | Summary score for quality assessment |

|---|---|---|

| Qualitative methods (Spencer et al. [15]) | ||

| Ameyan et al. [47] | QL | 61% (11/18) |

| Beattie et al. [48] | QL | 72% (13/18) |

| Burke et al. [54] | QL | 61% (11/18) |

| Chanda et al. [49] | QL | 67% (12/18) |

| Dugas et al. [29] | QL | 50% (9/18) |

| King et al. [46] | QL | 50% (9/18) |

| Ngo et al. [50] | QL | 72% (13/18) |

| Scorgie et al. [52] | QL | 67% (12/18) |

| Wang et al. [41] | QL | 67% (12/18) |

| Wanyenze et al. [51] | QL | 72% (13/18) |

| Quantitative methods (modified Downs and Black [16]) | ||

| Batona et al. [28] | QN | 56% (14/25) |

| Bengtson et al. [27] | QN | 52% (13/25) |

| Chiao et al. [45] | QN | 72% (18/25) |

| Dandona et al. [18] | QN | 40% (10/25) |

| Deering et al. [25] | QN | 60% (15/25) |

| Grayman et al. [30] | QN | 48% (12/25) |

| Hong et al. [31] | QN | 52% (13/25) |

| Johnston et al. [40] | QN | 64% (16/25) |

| King et al. [46] | QN | 52% (13/25) |

| Nhurod et al. [43] | QN | 56% (14/25) |

| Parriault et al. [17] | QN | 36% (9/25) |

| Shokoohi et al. [35] | QN | 56% (14/25) |

| Shokoohi et al. [35] | QN | 60% (15/25) |

| Todd et al. [32] | QN | 52% (13/25) |

| Tran et al. [33] | QN | 52% (13/25) |

| Wang et al. [19] | QN | 48% (12/25) |

| Wang et al. [20] | QN | 48% (12/25) |

| Wilson et al. [21] | QN, mathematical modeling | n/a |

| Xun et al. [42] | QN | 56% (14/25) |

| Xu et al. [23] | QN | 64% (16/25) |

| Mixed methods (modified Downs and Black [16]) | ||

| Aho et al. [26] | QN & QL | 68% (17/25) |

| King et al. [34] | QN & QL | 48 (12/25) |

| Abstracts | ||

| Deering et al. [37] | QN | n/a |

| Park et al. [38] | QN | n/a |

| Sayarifard et al. [36] | QN | n/a |

| Simonovikj et al. [53] | Case report | n/a |

QL qualitative, QN quantitative

Annex 4: PRISMA 2009 checklist

| Section/topic | # | Checklist item | Reported (Yes/No) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Title | |||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a systematic review, meta-analysis, or both. | Yes |

| Abstract | |||

| Structured summary | 2 | Provide a structured summary including, as applicable: background; objectives; data sources; study eligibility criteria, participants, and interventions; study appraisal and synthesis methods; results; limitations; conclusions and implications of key findings; systematic review registration number. | Yes |

| Introduction | |||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of what is already known. | Yes |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of questions being addressed with reference to participants, interventions, comparisons, outcomes, and study design (PICOS). | Not applicable |

| Methods | |||

| Protocol and registration | 5 | Indicate if a review protocol exists, if and where it can be accessed (e.g., Web address), and, if available, provide registration information including registration number. | Not available |

| Eligibility criteria | 6 | Specify study characteristics (e.g., PICOS, length of follow-up) and report characteristics (e.g., years considered, language, publication status) used as criteria for eligibility, giving rationale. | Yes |

| Information sources | 7 | Describe all information sources (e.g., databases with dates of coverage, contact with study authors to identify additional studies) in the search and date last searched. | Yes |

| Search | 8 | Present full electronic search strategy for at least one database, including any limits used, such that it could be repeated. | Yes (“Annex 1: Search strategy”) |

| Study selection | 9 | State the process for selecting studies (i.e., screening, eligibility, included in systematic review, and, if applicable, included in the meta-analysis). | Yes (Fig. 1) |

| Data collection process | 10 | Describe method of data extraction from reports (e.g., piloted forms, independently, in duplicate) and any processes for obtaining and confirming data from investigators. | Yes (“Annex 2: Data extraction form”) |

| Data items | 11 | List and define all variables for which data were sought (e.g., PICOS, funding sources) and any assumptions and simplifications made. | Yes |

| Risk of bias in individual studies | 12 | Describe methods used for assessing risk of bias of individual studies (including specification of whether this was done at the study or outcome level), and how this information is to be used in any data synthesis. | Not available |

| Summary measures | 13 | State the principal summary measures (e.g., risk ratio, difference in means). | Yes |

| Synthesis of results | 14 | Describe the methods of handling data and combining results of studies, if done, including measures of consistency (e.g., I2) for each meta-analysis. | Not applicable |

| Risk of bias across studies | 15 | Specify any assessment of risk of bias that may affect the cumulative evidence (e.g., publication bias, selective reporting within studies). | Yes |

| Additional analyses | 16 | Describe methods of additional analyses (e.g., sensitivity or subgroup analyses, meta-regression), if done, indicating which were pre-specified. | Not available |

| Results | |||

| Study selection | 17 | Give numbers of studies screened, assessed for eligibility, and included in the review, with reasons for exclusions at each stage, ideally with a flow diagram. | Yes (Fig. 1) |

| Study characteristics | 18 | For each study, present characteristics for which data were extracted (e.g., study size, PICOS, follow-up period) and provide the citations. | Yes (Table 1) |

| Risk of bias within studies | 19 | Present data on risk of bias of each study and, if available, any outcome level assessment (see item 12). | Not available |

| Results of individual studies | 20 | For all outcomes considered (benefits or harms), present, for each study: (a) simple summary data for each intervention group (b) effect estimates and confidence intervals, ideally with a forest plot. | Not applicable |

| Synthesis of results | 21 | Present results of each meta-analysis done, including confidence intervals and measures of consistency. | Not applicable |

| Risk of bias across studies | 22 | Present results of any assessment of risk of bias across studies (see Item 15). | Yes |

| Additional analysis | 23 | Give results of additional analyses, if done (e.g., sensitivity or subgroup analyses, meta-regression [see Item 16]). | Not available |

| Discussion | |||

| Summary of evidence | 24 | Summarize the main findings including the strength of evidence for each main outcome; consider their relevance to key groups (e.g., healthcare providers, users, and policy makers). | Yes (Table 1) |

| Limitations | 25 | Discuss limitations at study and outcome level (e.g., risk of bias), and at review-level (e.g., incomplete retrieval of identified research, reporting bias). | Yes |

| Conclusions | 26 | Provide a general interpretation of the results in the context of other evidence, and implications for future research. | Yes |

| Funding | |||

| Funding | 27 | Describe sources of funding for the systematic review and other support (e.g., supply of data); role of funders for the systematic review. | Not available |

Moher et al. [71]. For more information, visit: www.prisma-statement.org.

Author Contributions

Conceived the study: MR, AT. Developed the search strategy: AT, MR. Conducted online database searches and screened data: AT. Extracted and analyzed the data: AT. Wrote the paper: AT. Contributed to writing the paper: MR. Provided critical comments on the manuscript: MR, JEB, JB. Approved the final version of the manuscript: AT, MR, JEB, JB.

Funding

AT was financed by the TransGlobal Health Program as a part of the Erasmus Mundus Joint Doctorate Programme (ERASMUS MUNDUS 2009-2013, EMJD, Action 1B, Agreement No. 2013-0039). MR received funds from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (MINECO) as part of a “Ramon y Cajal” fellowship (RYC-2011-08428), and the Agència de Gestió d’Ajuts Universitaris i de Recerca, Regional Government of Catalonia (AGAUR Grant 2014SGR26).

Conflict of interest

Author AT declares that she has no conflict of interest. Author JEWB declares that she has no conflict of interest. Author JB declares that he has no conflict of interest Author MR declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Contributor Information

Anna Tokar, Phone: +34 93 227 1806, Email: anna.tokar@isglobal.org.

Jacqueline E. W. Broerse, Email: j.e.w.broerse@vu.nl

James Blanchard, Email: blanchard@cc.umanitoba.ca.

Maria Roura, Email: maria.roura@ul.ie.

References

- 1.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). The Gap report. 2014: Geneva,Switzerlan. UNAIDS/JC2684.

- 2.European Center of Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), HIV Testing: increase uptake and effectiveness in the European Union. 2010: Solna, Sweden.

- 3.World Health Organization (WHO), Consolidated guidelines on HIV testing services 2015. July, 2015:Geneva, Switzerlan. [PubMed]

- 4.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). 90-90-90 An ambitious treatment to help end the AIDS epidemic. 2014: Geneva, Switzerlan.

- 5.Aral OS, Blanchard FJ. Phase specific approaches to the epidemiology and prevention of sexually transmitted diseases. Sex Transm Infect. 2002;78(1):1–12. doi: 10.1136/sti.78.suppl_1.i1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Platt L, Grenfell P, Fletcher A, Sorhaindo A, Jolley E, Rhodes T, Bonell C. Systematic review examining differences in HIV, sexually transmitted infections and health-related harms between migrant and non-migrant female sex workers. Sex Transm Infect. 2013;89:311–319. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2012-050491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Platt L, Jolley E, Rhodes T, Hope V, Latypov A, Reynolds L, Wilson D. Factors mediating HIV risk among female sex workers in Europe: a systematic review and ecological analysis. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e002836. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baral S, Beyrer C, Muessig K, Poteat T, Wirtz LA, Decker RM, Sherman GS, Kerrigan D. Burden of HIV among female sex workers in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:538–549. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shahmanesh M, Patel V, Mabey D, Cowan F. Effectiveness of interventions for the prevention of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections in female sex workers in resource poor setting: a systematic review. Trop Med Int Health. 2008;13(5):59–679. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wariki W.M., Ota E., Mori R., Koyanagi A., Hori N., Shibuya K., Behavioral interventions to reduce the transmission of HIV infection among sex workers and their clients in low- and middle-income countries (Review). TheCochraneCollaboration and published in TheCochrane Library, 2012(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Andrea L, Wirtz CP, Beyrer C, Baral S, Decker RM, Sherman GS. Epidemic impacts of a community empowerment intervention for HIV prevention among female sex workers in generalized and concentrated epidemics. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(2):e88047. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kerrigan LD, Stromdahl S, Fonner AV, Kennedy EC. Community empowerment among female sex workers is an effective HIV prevention intervention: a systematic review of the peer-reviewed evidence from low- and middle-income countries. AIDS Behav. 2013;17:1926–1940. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0458-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suthar AB, et al. Towards universal voluntary HIV testing and counselling: a systematic review and meta-analysis of community-based approaches. PLoS Med. 2013;10(8):e1001496. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deblonde J., De Koker P., Hamers F. F., Fontaine J., Luchters S., Temmerman M., Barriers to HIV testing in Europe: a systematic review. 2010. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Spencer L., Ritchie J., Jane Lewis J., Dillon L., Quality in Qualitative Evaluation: A framework for assessing research evidence, in National Centre for Social Research. 2003.

- 16.Downs HS, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1997;52:377–384. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.6.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parriault MC, et al. HIV-testing among female sex workers on the border between Brazil and French Guiana: the need for targeted interventions. Cadernos de Saude Publica. 2015;31(8):1615–1622. doi: 10.1590/0102-311X00138514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dandona R, et al. HIV testing among female sex workers in Andhra Pradesh, India. AIDS. 2005;19(17):2033–2036. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000191921.31808.8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Y, et al. Reported willingness and associated factors related to utilization of voluntary counseling and testing services by female sex workers in Shandong Province, China. Biomed Environ Sci. 2010;23(6):466–472. doi: 10.1016/S0895-3988(11)60009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Y, et al. Factors associated with utilization of a free HIV VCT clinic by female sex workers in Jinan City, North China. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(4):702–710. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9703-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilson DP, et al. Sex workers can be screened too often: a costeffectiveness analysis in Victoria, Australia. Sex Transm Infect. 2010;86(2):117–125. doi: 10.1136/sti.2009.036673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blanchard FJ, Aral OS. Emergent properties and structural patterns in sexually transmitted infection and HIV research. Sex Transm Infect. 2010;86(3):4–9. doi: 10.1136/sti.2010.046037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu J, et al. Factors associated with HIV testing history and HIV-test result follow-up among female sex workers in two cities in Yunnan, China. Sex Trans Dis. 2011;38(2):89–95. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181f0bc5e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.King EJ, Maman S. Structural barriers to receiving health care services for female sex workers in Russia. Qual Health Res. 2013;23(8):1079–1088. doi: 10.1177/1049732313494854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deering KN, et al. Successes and gaps in uptake of regular, voluntary HIV testing for hidden street- and off-street sex workers in Vancouver, Canada. AIDS Care. 2015;27(4):499–506. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2014.978730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aho J, et al. High acceptability of HIV voluntary counselling and testing among female sex workers: impact of individual and social factors. HIV Med. 2012;13(3):156–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2011.00951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bengtson AM, et al. Levels of alcohol use and history of HIV testing among female sex workers in Mombasa, Kenya. AIDS Care. 2014;26(12):1619–1624. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2014.938013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Batona G, et al. Understanding the intention to undergo regular HIV testing among female sex workers in Benin: a key issue for entry into HIV care. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1999;2015(68):S206–S212. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dugas M, et al. Outreach strategies for the promotion of HIV testing and care: closing the gap between health services and female sex workers in Benin. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1999;2015(68):S198–S205. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grayman JH, et al. Factors associated with HIV testing, condom use, and sexually transmitted infections among female sex workers in Nha Trang, Vietnam. AIDS Behav. 2005;9(1):41–51. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-1680-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hong Y, et al. HIV testing behaviors among female sex workers in Southwest China. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(1):44–52. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9960-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Todd CS, et al. Prevalence and correlates of condom use and HIV testing among female sex workers in Tashkent, Uzbekistan: implications for HIV transmission. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(3):435–442. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9155-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tran BX, et al. HIV voluntary testing and perceived risk among female sex workers in the Mekong Delta region of Vietnam. Glob Health Action. 2013;6:20690. doi: 10.3402/gha.v6i0.20690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.King EJ, et al. Motivators and barriers to HIV testing among street-based female sex workers in St. Petersburg, Russia. Global Public Health. 2017;12(7):876–891. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2015.1124905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shokoohi M, et al. Correlates of HIV Testing among Female Sex Workers in Iran: findings of a National Bio-Behavioural Surveillance Survey. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(1):e0147587. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sayarifard A, Kolahi A, Hamedani MH. Frequency of performing HIV test and reasons of not-testing among female sex workers. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173:S197. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Deering K, et al. Mapping spatial barriers and facilitators to HIV testing by work environments among sex workers in Vancouver, Canada. J Int AIDS Soc. 2012;15:171–172. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Park M, Yi H. HIV prevention support ties determine access to HIV testing among migrant female sex workers in Beijing, China. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173:S223. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq447. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shokoohi M, et al. Remaining gap in HIV testing uptake among female sex workers in Iran. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(8):2401–2411. doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-1844-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johnston GL, et al. Associations of HIV testing, sexual risk and access to prevention among female sex workers in the dominican republic. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(8):2362–2371. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1616-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang Y, et al. Factors related to female sex workers’ Willingness to utilize VCT service: a qualitative study in Jinan City, Northern China. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(5):866–872. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9446-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xun H, et al. Factors associated with willingness to accept oral fluid HIV rapid testing among most-at-risk populations in China. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(11):87. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nhurod P, et al. Access to HIV testing for sex workers in Bangkok, Thailand: a high prevalence of HIV among street-based sex workers. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2010;41(1):153–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hong Y, et al. Environmental support and HIV prevention behaviors among female sex workers in China. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35(7):662–667. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31816b322c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chiao C, et al. Promoting HIV testing and condom use among filipina commercial sex workers: findings from a quasi-experimental intervention study. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(5):892–901. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9418-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.King EJ, et al. The influence of stigma and discrimination on female sex workers’ access to HIV services in St. Petersburg, Russia. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(8):2597–2603. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0447-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ameyan W, et al. Attracting female sex workers to HIV testing and counselling in Ethiopia: a qualitative study with sex workers in Addis Ababa. Afr J AIDS Res. 2015;14(2):137–144. doi: 10.2989/16085906.2015.1040809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Beattie TS, et al. Personal, interpersonal and structural challenges to accessing HIV testing, treatment and care services among female sex workers, men who have sex with men and transgenders in Karnataka state, South India. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2012;66:42–48. doi: 10.1136/jech-2011-200475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chanda MM, et al. Barriers and facilitators to HIV testing among Zambian female sex workers in three transit hubs. AIDS Pat Care Stds. 2017;31(7):290–296. doi: 10.1089/apc.2017.0016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ngo AD, et al. Health-seeking behaviour for sexually transmitted infections and HIV testing among female sex workers in Vietnam. AIDS Care. 2007;19(7):878–887. doi: 10.1080/09540120601163078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wanyenze RK, et al. “When they know that you are a sex worker, you will be the last person to be treated”: perceptions and experiences of female sex workers in accessing HIV services in Uganda. BMC Int Health Human Rights. 2017;17(1):11. doi: 10.1186/s12914-017-0119-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Scorgie F, et al. ‘We are despised in the hospitals’: sex workers’ experiences of accessing health care in four African countries. Culture Health Sex. 2013;15(4):450–465. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2012.763187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Simonovikj SH, Tosheva M. Model of human rights protection of sex workers exposed to forced HIV/STI testing through combination of court litigation and psycho-social support. J Int AIDS Soc. 2012;15:223. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Burke VM, et al. HIV self-testing values and preferences among sex workers, fishermen, and mainland community members in Rakai, Uganda: a qualitative study. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(8):e0183280. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shannon K, Goldenberga MS, Deeringa NK, Steffanie A, Strathdee S, et al. HIV infection among female sex workers in concentrated and high prevalence epidemics: why a structural determinants framework is needed. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2014;9(2):174–182. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shannon K., Strathdee A. S., Goldenberg M. S., Duff P., Mwangi P., Rusakova M., Reza-Paul S., Lau J., Deering K., Pickles R. M., Boily M. C., Goldenberg S. M., Deering K. N., Strathdee S. A., Global epidemiology of HIV among female sex workers: infl uence of structural determinants. Lancet HIV and sex workers Series, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.World Health Organization (WHO), Delivering HIV test results and messages for re-testing and counselling in adults. 2010: Geneva, Switzerlan. [PubMed]

- 58.Sarah J, Blondell BK, Mark P, Durham JG. Barriers and facilitators to HIV testing in migrants in high-income countries: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2015;21:2012–2024. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1095-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Alvarez-del Arco D, Monge S, Azcoaga A, Rio I, Hernando V, Gonzalez C, Alejos B, Caro MA, Perez-Cachafeiro S, Ramirez-Rubio O, Bolumar F, Noori T, Del Amo J. HIV testing and counselling for migrant populations living in high-income countries: a systematic review. Eur J Pub Health. 2012;23(6):1039–1045. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cks130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Owens GM. Gender differences in health care expenditures, resource utilization, and quality of care. J Manag Care Phar. 2008;4(3):2–6. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2008.14.S3-A.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.World Health Organization, W., Global update on the health sector response to HIV, 2014. 2014.

- 62.Barrington C, Kerrigan D. Debe cuidarse en la calle: Normative influences on condom use among the steady male partners of female sex workers in the Dominican Republic. Cult Health Sex. 2015;16:273–287. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2013.875222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Deering NK, Bhattacharjee P, Bradley J, Moses SS, Shannon K, Shaw YS, Washington R, Lowndes MC, Boily MC, Ramesh MB, Rajaram S, Gurav K, Alary M. Condom use within non-commercial partnerships of female sex workers in southern India. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(6):S11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-S6-S11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kerrigana D, Ellenb M. Environmental-structural factors significantly associated with consistent condom use among female sex workers in the Dominican Republic. AIDS. 2003;17:415–423. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200302140-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Factbook, 100 Countries and Their Prostitution Policies. 2015 Last updated on: 4/1/2015; Available from: http://prostitution.procon.org/view.resource.php?resourceID=000772.

- 66.Stangl LA, Lloyd JK, Brady ML, Hollandand EC, Baral S. A systematic review of interventions to reduce HIV-related stigma and discrimination from 2002 to 2013: how far have we come? J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16(2):S32. doi: 10.7448/IAS.16.3.18734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.World Health Organization (WHO), Guideline on HIV disclouser conselling for children up to 12 years of age. 2011, Geneva, Switzerlan. [PubMed]

- 68.Grossman I. C., Stangl L. A., Global action to reduce HIV stigma and discrimination. Journal of the International AIDS Society 2013.16(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 69.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), Policy brief: Criminalisation of HIV transmission. 2008: Geneva, Switzerlan.

- 70.Global Network of People Living with HIV, The global criminalisation scan report. 2010.

- 71.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(6):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]