Abstract

Background

Gastric adenocarcinoma is the second most common cancer-related death globally. Assessing survival trends can help evaluate changes in detection and treatment. We aimed to determine recent prognosis trends in gastric non-cardia and cardia adenocarcinoma in an unselected cohort with complete follow-up.

Methods

Population-based nationwide cohort study, including 17,491 patients with gastric non-cardia adenocarcinoma and 4698 with cardia adenocarcinoma recorded in the Swedish Cancer Registry in 1990–2013 with follow-up until 2017. Observed and relative 5-year survival was calculated and stratified by resectional surgery and no such surgery. Prognostic factors were evaluated using multivariable Cox regression.

Results

The relative overall 5-year survival remained stable at 18% for gastric non-cardia adenocarcinoma throughout the study period and increased from 12 to 18% for cardia adenocarcinoma. Concurrently, the proportion of patients who underwent resectional surgery decreased from 49 to 38% for non-cardia adenocarcinoma and from 48 to 33% for cardia adenocarcinoma. The relative postoperative 5-year survival increased from 33 to 44% for non-cardia adenocarcinoma and from 21 to 43% for cardia adenocarcinoma, whereas in nonoperated patients it decreased from 3 to 2% in non-cardia adenocarcinoma and increased from 3 to 5% in cardia adenocarcinoma. Poor prognostic factors were higher tumor stage, older age, and more comorbidity.

Conclusions

Despite decreasing resectional rates, the 5-year overall survival has remained unchanged for gastric non-cardia adenocarcinoma and improved for cardia adenocarcinoma over the last two decades in Sweden and is now similar for these sublocations. The postoperative survival has improved for both sublocations, but particularly for cardia adenocarcinoma.

Gastric cancer is the fifth most common cancer and the second most common cancer-related death globally.1 Adenocarcinoma is the dominant histologic type, accounting for > 95% of all gastric cancers.2 Gastric adenocarcinoma can be classified into two topographical subgroups, i.e., non-cardia and cardia, because these tumors have different incidence patterns, etiology and prognosis.3–7 The incidence of gastric non-cardia adenocarcinoma has steadily decreased over the past decades, while it has increased for gastric cardia adenocarcinoma, at least until recently.8–11 The strongest risk factor for gastric non-cardia adenocarcinoma is Helicobacter pylori infection.3–5,12 Gastroesophageal reflux and obesity are the main risk factors for gastric cardia adenocarcinoma.12 Gastric adenocarcinoma has a poor overall prognosis; tumor stage and fitness (comorbidity and age) are the strongest prognostic factors but have great variability worldwide.1,3 The prognosis in non-cardia adenocarcinoma is generally better than that in cardia adenocarcinoma.13,14 However, an analysis of survival trends in Sweden in 1970–2008 identified a declining survival in gastric non-cardia adenocarcinoma and an improving survival in gastric cardia adenocarcinoma.15 Surgery is the main curative treatment, and for locally advanced disease, oncological therapy is usually added to surgery.3

Assessing changes in survival over time is important in the evaluation of changes in detection and treatment of gastric adenocarcinoma. Sweden offers excellent opportunities to assess population-based and nationwide survival trends in cancer because all individuals in Sweden are since long registered for cancer and mortality in updated nationwide highly complete registries. This study assessed the survival trends in gastric non-cardia and cardia adenocarcinoma in patients having undergone resectional surgery and no such surgery in a population-based cohort study in Sweden.

Methods

Design

This nationwide, Swedish, population-based cohort study examined the prognosis in patients diagnosed with gastric non-cardia adenocarcinoma and gastric cardia adenocarcinoma between 1990 and 2013 with follow-up until May 14, 2017. The data were collected from three well-established nationwide Swedish registries (presented below). The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm, Sweden (diary number 2015/1916-31/1).

Data Collection

The patients with gastric adenocarcinoma were identified through data from the Swedish Cancer Registry. This registry was established in 1958 and has 98% completeness in the recording of gastric adenocarcinoma.16 The Cancer Registry provided accurate information regarding date of diagnosis, histological type and location, tumor stage, age at diagnosis, and sex. The 7th version of the International Classification of Diagnoses (ICD-7) was used for coding of cancer diagnoses and WHO/HS/CANC/24/24.1 for coding of histological type of cancer. Gastric non-cardia adenocarcinoma was coded as ICD-7 code 151.0, 151.8 or 151.9 combined with the histology code 096, and cardia adenocarcinoma was coded as ICD-7 code 151.1 combined with the histology code 096. Histologic types other than adenocarcinoma were excluded because they are not comparable in terms of treatment or prognosis. Tumor stage data were added in the Swedish Cancer Registry from June 2004 onwards and were based on the classification of the 6th edition of the TNM-staging system of the Union Internationale Contre le Cancer.17

Data regarding surgical tumor resection and comorbidities at the time of diagnosis were retrieved from the Swedish Patient Registry. This is a registry with a national completeness of above 99% and a positive predictive value of 99.6% for resectional surgery of upper gastrointestinal cancer.18,19 Resectional surgery included total gastrectomy or subtotal gastrectomy, coded according to the Swedish Surgical Codes, 6th edition as 4430, 4432, 4434, 4435 or 4411–4420, 4422, 4424–4426, or 4429. Comorbidity was defined according to the most updated version of the well-validated Charlson Comorbidity Index.20

Mortality was assessed from the Swedish Causes of Death Registry, which has virtually 100% complete information on date of death for all deceased Swedish residents from 1952 onwards.21

Statistical Analysis

Observed and relative survival was analyzed at 1 and 5 years following the diagnosis of gastric non-cardia adenocarcinoma or gastric cardia adenocarcinoma, analyzed separately. Observed survival with 95% confidence interval (CI) was estimated using the life-table method, where the event was defined as death from any cause, i.e., all-cause mortality.22 To assess disease-specific mortality, relative survival with 95% CIs was calculated as the ratio of the observed to the expected survival. The expected survival was derived from a matched cohort from the entire general Swedish population. The survival in the general Swedish population was available from the start of the study (1990) until end of 2015. The relative survival rates for years 2016 and 2017 were based on the mortality rates of 2015. The results were analyzed for all patients as well as stratified by resectional surgery (representing “curative treatment”) and no such surgery (representing “palliative treatment”).

The observed survival was further stratified by calendar periods (1990–1994, 1995–1999, 2000–2004, 2005–2009, and 2010–2013), age groups (< 60, 60–69, 70–79, and ≥ 80 years), sex (male and female), and comorbidity (Charlson Comorbidity Index score 0, 1, and ≥ 2). Surgically treated patients were also stratified by tumor stage (0–I, II, and III–IV) from year 2005 onwards, when tumor stage data were of good quality and completeness according to a recent validation study from our group.23 To manage partial missing data for tumor stage (19.5% for gastric non-cardia adenocarcinoma and 11.0% for cardia adenocarcinoma), both complete case analysis and multiple imputation analysis were used. The number of imputed datasets were 20 and the monotone logistic method in PROC MI in SAS was used under the assumption that missing data were missing at random.24 The variables included in the imputation were 5-year mortality, tumor stage (0–I, II, or III–IV), calendar period (2005–2009 or 2010–2013), age (continuous), sex (male or female), and Charlson Comorbidity Index score (0, 1, or ≥ 2). PROC MIANALYZE in SAS was used to combine the results from the analyses of the 20 datasets.

To also examine prognostic factors, Cox regression modelling was used to calculate crude and adjusted hazard ratios (HR) of mortality with 95% CIs for each of the stratification variables above, which were thus considered potential prognostic factors. The estimates for each of these potential prognostic factors were adjusted for the other factors, using the same categorization as presented above.

An experienced biostatistician (FM) conducted all data management and statistical analyses according to a detailed and pre-defined study protocol. All analyses were conducted using the SAS Statistical Package (version 9.4, SAS Institute Inc., Gary, NC).

Results

Patients

This study included 17,491 patients diagnosed with non-cardia adenocarcinoma and 4698 with cardia adenocarcinoma (Table 1). Men were slightly overrepresented in patients with non-cardia adenocarcinoma (58%) and strongly so in patients with cardia adenocarcinoma (76%; Table 2).

Table 1.

Observed and relative 1- and 5-year survival with 95% confidence intervals (CI) across calendar periods in gastric non-cardia adenocarcinoma and gastric cardia adenocarcinoma, stratified by treatment strategy in 1990–2013, with follow-up until 2017

| Gastric non-cardia adenocarcinoma | Gastric cardia adenocarcinoma | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | Observed survival in % (95% CI) | Relative survival in % (95% CI) | Patients | Observed survival in % (95% CI) | Relative survival in % (95% CI) | |||||||

| Calendar period | Number (%) | Median age | 1 year | 5 years | 1 year | 5 years | Number (%) | Median age | 1 year | 5 years | 1 year | 5 years |

| All patients | ||||||||||||

| 1990–1994 | 5052 (29) | 74 | 39 (38–0.7) | 15 (14–16) | 42 (40–43) | 18 (17–19) | 960 (20) | 71 | 36 (33–39) | 10 (8–12) | 38 (35–41) | 12 (9–14) |

| 1995–1 999 | 4095 (23) | 75 | 39 (38–41) | 16 (15–17) | 42 (40–43) | 19 (18–21) | 976 (21) | 72 | 33 (33–39) | 9 (7–11) | 38 (35–41) | 11 (9–13) |

| 2000–2004 | 3472 (20) | 75 | 40 (38–42) | 14 (13–15) | 42 (40–44) | 17 (16–18) | 956 (20) | 71 | 37 (34–40) | 10 (8–12) | 39 (36–42) | 11 (9–13) |

| 2005–2009 | 2830 (16) | 75 | 41 (39–42) | 14 (13–15) | 43 (41–44) | 16 (15–18) | 986 (21) | 69 | 44 (41–47) | 14 (12–16) | 46 (43–49) | 16 (14–19) |

| 2010–2013 | 2042 (12) | 74 | 42 (40–44) | 16 (15–18) | 44 (42–46) | 18 (17–20) | 820 (17) | 69 | 47 (43–50) | 16 (13–18) | 49 (45–52) | 18 (15–21) |

| Surgery | ||||||||||||

| 1990–1994 | 2498 (32) | 73 | 63 (62–65) | 27 (25–29) | 66 (64–68) | 33 (31–35) | 461 (25) | 67 | 59 (54–63) | 17 (14–21) | 62 (57–67) | 21 (17–25) |

| 1995–1999 | 1872 (24) | 73 | 66 (64–68) | 30 (28–32) | 70 (67–72) | 36 (34–39) | 384 (21) | 67 | 64 (60–69) | 21 (17–25) | 68 (63–73) | 25 (20–30) |

| 2000–2004 | 1544 (20) | 73 | 68 (66–71) | 29 (27–31) | 72 (69–74) | 34 (32–37) | 378 (20) | 67 | 66 (62–71) | 21 (17–25) | 70 (65–75) | 25 (20–30) |

| 2005–2009 | 1128 (14) | 72 | 73 (70–75) | 32 (29–35) | 76 (73–79) | 37 (33–40) | 363 (20) | 64 | 77 (73–81) | 33 (28–37) | 80 (76–85) | 37 (32–43) |

| 2010–2013 | 786 (10) | 71 | 77 (74–80) | 39 (36–43) | 80 (77–83) | 44 (40–48) | 269 (15) | 66 | 84 (80–89) | 39 (33–45) | 88 (83–92) | 43 (33–54) |

| No surgery | ||||||||||||

| 1990–1994 | 2554 (26) | 76 | 16 (15–18) | 3 (2–3) | 17 (16–19) | 3 (2–4) | 499 (18) | 75 | 15 (12–18) | 2 (0.9–4) | 16 (13–19) | 3 (1–4) |

| 1995–1999 | 2223 (23) | 77 | 17 (15–18) | 4 (3–5) | 18 (16–19) | 5 (4–6) | 592 (21) | 76 | 17 (14–20) | 1 (0.2–2) | 18 (15–22) | 1 (0.3–2) |

| 2000–2004 | 1928 (20) | 77 | 17 (15–19) | 2 (2–3) | 18 (16–20) | 3 (2–4) | 578 (20) | 74 | 18 (15–21) | 2 (0.9–3) | 19 (16–22) | 3 (1–4) |

| 2005–2009 | 1702 (18) | 78 | 19 (18–21) | 2 (2–3) | 20 (18–22) | 3 (2–3) | 623 (22) | 73 | 24 (21–28) | 3 (2–5) | 26 (22–29) | 4 (2–3) |

| 2010–2013 | 1256 (13) | 76 | 20 (18–22) | 2 (1–3) | 21 (19–23) | 2 (1–3) | 551 (19) | 70 | 28 (25–32) | 4 (3–6) | 30 (26–34) | 5 (3–7) |

Table 2.

Observed 5-year survival and adjusted hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for gastric non-cardia adenocarcinoma and gastric cardia adenocarcinoma 1990–2017

| Covariate | Category | Gastric non-cardia adenocarcinoma | Gastric cardia adenocarcinoma | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients (%) | Observed 5-year survival (95% CI) | HR (95% CI)a | Number of patients | Observed 5-year survival (95% CI) | HR (95% CI)a | ||

| All patients | |||||||

| Calendar period | 1990–1994 | 5052 (29) | 15 (14–16) | 1.11 (1.05–1.17) | 960 (20) | 10 (8–12) | 1.31 (1.18–1.45) |

| 1995–1999 | 4095 (23) | 16 (15–17) | 1.08 (1.02–1.15) | 976 (21) | 9 (7–11) | 1.33 (1.20–1.47) | |

| 2000–2004 | 3472 (20) | 14 (13–15) | 1.09 (1.03–1.16) | 956 (20) | 10 (8–12) | 1.25 (1.13–1.38) | |

| 2005–2009 | 2830 (16) | 14 (13–15) | 1.07 (1.01–1.14) | 986 (21) | 14 (12–16) | 1.07 (0.97–1.19) | |

| 2010–2013 | 2042 (12) | 16 (15–18) | 1 (reference) | 820 (17) | 16 (13–18) | 1 (reference) | |

| Age (years) | < 60 | 2438 (14) | 23 (21–25) | 1 (reference) | 963 (26) | 18 (16–20) | 1 (reference) |

| 60–69 | 3417 (20 | 20 (18–21) | 1.08 (1.02–1.15) | 1238 (32) | 15 (13–17) | 1.10 (1.01–1.21) | |

| 70–79 | 6168 (35) | 16 (15–17) | 1.18 (1.12–1.24) | 1505 (21) | 10 (9–12) | 1.31 (1.19–1.43) | |

| ≥ 80 | 5468 (31) | 7 (7–8) | 1.65 (1.56–1.74) | 992 (21) | 3 (2–4) | 1.99 (1.80–2.20) | |

| Sex | Male | 10,132 (58) | 15 (14–16) | 1 (reference) | 3593 (76) | 12 (11–13) | 1 (reference) |

| Female | 7359 (42) | 15 (15–16) | 0.99 (0.56–1.02) | 1105 (24) | 11 (9–13) | 1.04 (0.97–1.12) | |

| Comorbidity score | 0 | 9160 (52) | 19 (18–20) | 1 (reference) | 2653 (56) | 14 (13–15) | 1 (reference) |

| 1 | 5947 (34) | 12 (11–13) | 1.29 (1.24–1.33) | 1405 (30) | 10 (8–11) | 1.0 (1.12–1.29) | |

| ≥ 2 | 2384 (14) | 9 (7–10) | 1.38 (1.31–1.45) | 640 (14) | 5 (3–6) | 1.38 (1.26–1.51) | |

| Surgery | |||||||

| Calendar period | 1990–1994 | 2498 (32) | 27 (25–29) | 1.46 (1.32–1.62) | 461 (25) | 17 (14–21) | 2.08 (1.73–2.51) |

| 1995–1999 | 1872 (24) | 30 (28–32) | 1.34 (1.20–1.48) | 384 (21) | 21 (17–25) | 1.81 (1.50–2–20) | |

| 2000–2004 | 1544 (20) | 29 (27–31) | 1.37 (1.23–1.52) | 378 (20) | 21 (17–25) | 1.72 (1.42–2.09) | |

| 2005–2009 | 1128 (14) | 32 (29–35) | 1.20 (1.07–1.34) | 363 (20) | 33 (28–37) | 1.26 (1.03–1.54) | |

| 2010–2013 | 786 (10) | 39 (36–43) | 1 (reference) | 269 (15) | 39 (33–45) | 1 (reference) | |

| Age (years) | < 60 | 1296 (17) | 39 (37–42) | 1 (reference) | 516 (28) | 30 (26–34) | 1 (reference) |

| 60–69 | 1763 (23) | 35 (33–37) | 1.10 (1.01–1.21) | 617 (33) | 26 (22–29) | 1.14 (0.99–1.31) | |

| 70–79 | 3109 (40) | 29 (27–31) | 1.25 (1.15–1.35) | 601 (32) | 22 (19–25) | 1.24 (1.07–1.42) | |

| ≥ 80 | 1660 (21) | 20 (18–22) | 1.61 (1.47–1.76) | 121 (7) | 15 (9–22) | 1.60 (1.28–1.99) | |

| Sex | Male | 4597 (59) | 29 (28–31) | 1 (reference) | 1491 (80) | 24 (22–26) | 1 (reference) |

| Female | 3231 (41) | 31 (29–33) | 0.96 (0.91–1.02) | 364 (20) | 29 (25–34) | 0.86 (0.75–0.99) | |

| Comorbidity score | 0 | 4578 (58) | 35 (33–36) | 1 (reference) | 1211 (65) | 27 (25–30) | 1 (reference) |

| 1 | 2445 (31) | 25 (23–26) | 1.28 (1.20–1.35) | 480 (26) | 24 (20–28) | 1.17 (1.03–1.32) | |

| ≥2 | 805 (10) | 21 (18–24) | 1.41 (1.29–1.54) | 164 (9) | 11 (6–16) | 1.60 (1.34–1.91) | |

| No surgery | |||||||

| Calendar period | 1990–1994 | 2554 (26) | 3 (2–3) | 1.22 (1.14–1.30) | 499 (18) | 2 (0.9–4) | 1.41 (1.24–1.59) |

| 1995–1999 | 2223 (23) | 4 (3–5) | 1.12 (1.04–1.20) | 592 (21) | 1 (0.2–2) | 1.41 (1.25–1.59) | |

| 2000–2004 | 1928 (20) | 2 (2–3) | 1.10 (1.02–1.18) | 578 (20) | 2 (0.9–3) | 1.26 (1.12–1.42) | |

| 2005–2009 | 1702 (18) | 2 (2–3) | 1.07 (0.99–1.15) | 623 (22) | 3 (2–5) | 1.09 (0.97–1.23) | |

| 2010–2013 | 1256 (13) | 2 (1–3) | 1 (reference) | 551 (19) | 4 (3–6) | 1 (reference) | |

| Age (years) | < 60 | 1142 (12) | 4 (3–5) | 1 (reference) | 447 (16) | 4 (2–6) | 1 (reference) |

| 60–69 | 1654 (17) | 4 (3–4) | 1.07 (0.99–1.15) | 621 (22) | 3 (2–5) | 1.02 (0.90–1.16) | |

| 70–79 | 3059 (32) | 3 (2–4) | 1.15 (1.07–1.23) | 904 (32) | 3 (2–4) | 1.10 (0.97–1.23) | |

| ≥ 80 | 3808 (39) | 1 (1–2) | 1.17 (1.09–1.26) | 871 (31) | 1 (0.5–2) | 1.18 (0.98–1.17) | |

| Sex | Male | 5535 (57) | 3 (2–3) | 1 (reference) | 2102 (74) | 3 (1–3) | 1 (reference) |

| Female | 4128 (43) | 2 (2–3) | 0.98 (0.94–1.02) | 741 (26) | 2 (1–3) | 1.07 (0.98–1.17) | |

| Comorbidity score | 0 | 4582 (47) | 4 (3–5) | 1 (reference) | 1442 (51) | 3 (2–4) | 1 (reference) |

| 1 | 3502 (36) | 3 (1–4) | 1.18 (1.13–1.23) | 925 (33) | 2 (2–3) | 1.10 (1.01–1.20) | |

| ≥ 2 | 1579 (16) | 2 (1–3) | 1.11 (1.05) | 476 (17) | 2 (1–4) | 1.08 (0.97–1.20) | |

aAdjusted for calendar period, age, sex, and comorbidity

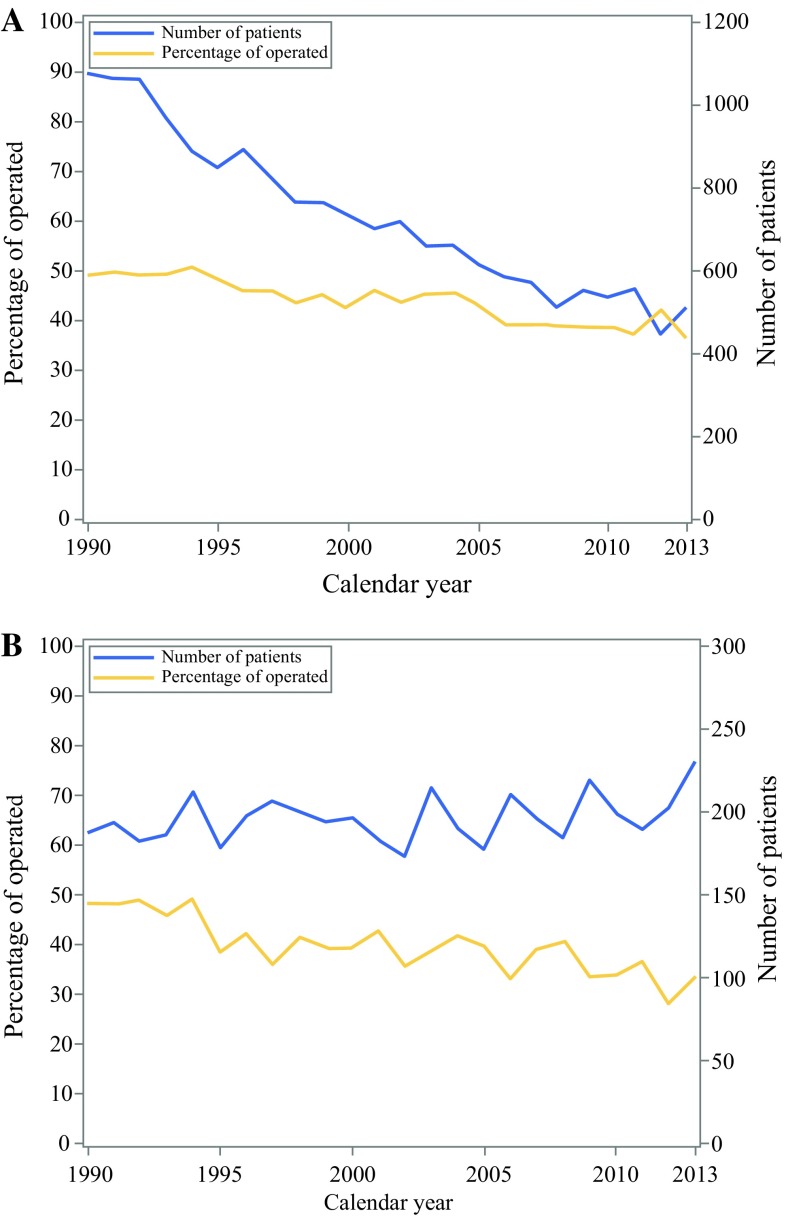

Resectional Surgery

Surgical resection was conducted in 7828 (45%) of all patients with gastric non-cardia adenocarcinoma and in 1855 (39%) of those with cardia adenocarcinoma. Comparing patients who underwent surgery during the first (1990–1994) and last (2010–2013) calendar periods, the proportion of operated patients decreased from 49 to 38% for gastric non-cardia adenocarcinoma and from 48 to 33% for cardia adenocarcinoma (Table 1) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The graphs show number of gastric non-cardia adenocarcinoma (a) and gastric cardia adenocarcinoma (b) patients diagnosed in Sweden by year from 1990 to 2013 (with follow-up until 2017). The curves show the number of patients diagnosed with cancer (solid line) and proportion of patients undergoing surgery (dotted line)

Survival Trends in Gastric Non-cardia Adenocarcinoma

The observed and relative survival data for gastric non-cardia adenocarcinoma are presented in Table 1. Because the results for observed survival closely mirrored the relative survival, only the latter are presented here.

All Patients

The 5-year relative survival rate in non-cardia adenocarcinoma remained unchanged at 18% (95% CI 17–20%) throughout the study period (1990–2013 with follow-up until 2017; Table 1).

Surgically Treated Patients

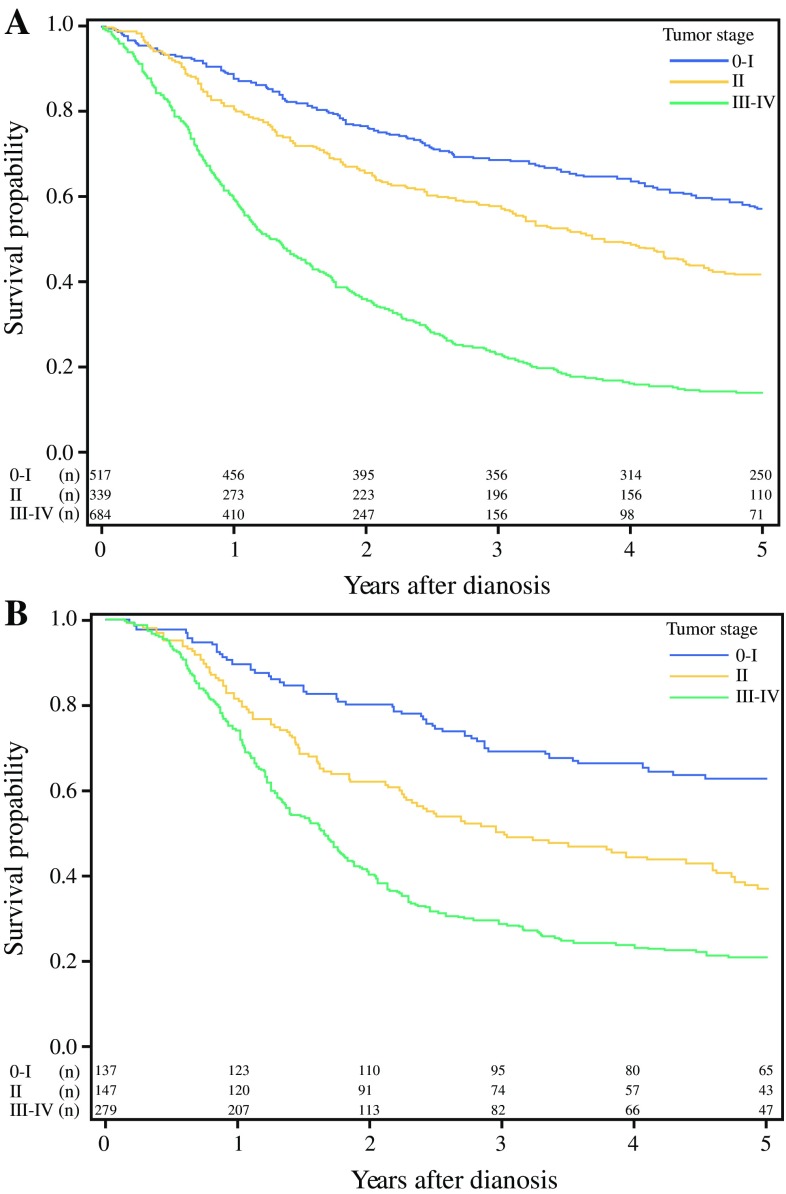

In patients who underwent resectional surgery for non-cardia adenocarcinoma the 5-year relative survival increased from 33% (95% CI 31–35%) to 44% (95% CI 40–48%) between the first and last calendar period (Table 1) (Fig. 2). Comparing the observed 5-year tumor-stage specific survival for calendar period 2005–2009 with 2010–2013, the survival increased from 56% (95% CI 50–61) to 59% (95% CI 52–66) for stage 0–I tumors, from 34% (95% CI 27–41) to 53% (95% CI 45–61) for stage II tumors, and from 11% (95% CI 8–14) to 18% (95% CI 13–23) for stage III–IV tumors (Table 3) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves showing observed 5-year survival for gastric non-cardia adenocarcinoma (a) and gastric cardia adenocarcinoma (b) stratified by surgical treatment (yes or no). Patients undergoing tumor resection for gastric non-cardia adenocarcinoma (c) and gastric cardia adenocarcinoma (d) are further stratified by calendar periods. Survival of the patients not undergoing surgery for gastric non-cardia adenocarcinoma (e) and gastric cardia adenocarcinoma (f) are shown stratified by calendar period

Table 3.

Hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) of 5-year mortality after surgery for gastric non-cardia adenocarcinoma and gastric cardia adenocarcinoma 2005-2017. Observed 5-year survival after surgery stratified by tumor stage in 2005–2017. Observed 5-year survival stratified by tumor-stage for calendar period 2005–2009 and 2010–2013

| Gastric non-cardia adenocarcinoma | Gastric cardia adenocarcinoma | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariates | Number of patients (%) | Tumor stageb | Observed 5-year survival (95% CI) | Crude HR (95% CI) | Adjusted HR (95% CI)a | Number of patients (%) | Tumor stageb | Observed 5-year survival (95% CI) | Crude HR (95% CI) | Adjusted HR (95% CI)a |

| Tumor stageb | ||||||||||

| 0–I | 517 (34) | 58 (54–62) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 137 (24) | 64 (57–72) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||

| II | 339 (22) | 41 (36–46) | 1.55 (1.28–1.88) | 1.61 (1.33–1.95) | 147 (26) | 35 (28–42) | 2.05 (1.45–2.89) | 2.09 (1.47–2.95) | ||

| III–IV | 684 (44) | 13 (11–15) | 3.72 (4.36) | 3.97 (3.39–4.65) | 279 (50) | 20 (16–25) | 3.47 (2.55–4.72) | 3.73 (2.73–5.10) | ||

| Calendar period | ||||||||||

| 2005–2009 | 893 (58) | 1.22 (1.07–1.38) | 1.30 (1.15–1.48) | 314 (56) | 1.22 (0.99–1.50) | 1.28 (1.04–1.58) | ||||

| 2010–2013 | 647 (42) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 249 (44) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| Age (years) | ||||||||||

| < 60 | 289 (26) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 157 (28) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| 60–69 | 394 (34) | 1.23 (1.01–1.51) | 1.20 (0.98–1.47) | 216 (38) | 1.22 (0.94–1.59) | 1.42 (1.08–1.86) | ||||

| 70–79 | 521 (22) | 1.43 (1.18–1.73) | 1.36 (1.12–1.66) | 155 (28 | 1.33 (1.00–1.76) | 1.52 (1.13–2–03) | ||||

| ≥ 80 | 336 (19) | 2.24 (1.83–2.73) | 2.24 (1.82–2.75) | 35 (6) | 1.81 (1.18–2.79) | 2.08 (1.33–3.23) | ||||

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Male | 872 (57) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 451 (80) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| Female | 668 (43) | 0.92 (0.81–1.04) | 0.94 (0.83–1.07) | 112 (20) | 0.76 (0.58–1.00) | 0.82 (0.62–1.08) | ||||

| Comorbidity score | ||||||||||

| 0 | 916 (59) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 355 (63) | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | ||||

| 1 | 436 (28) | 1.25 (1.09–1.44) | 1.19 (1.03–1.37) | 154 (27) | 1.17 (0.92–1.48) | 1.19 (0.93–1.52) | ||||

| ≥ 2 | 188 (12) | 1.40 (1.16–1.69) | 1.28 (1.05–1.55) | 54 (10) | 1.74 (1.25–2.41) | 1.49 (1.07–2.09) | ||||

| Calendar period | ||||||||||

| 2005–2009 | 306 | 0–I | 56 (50–61) | 71 | 0–I | 65 (54–76) | ||||

| 2005–2009 | 192 | II | 34 (27–41) | 85 | II | 39 (28–49) | ||||

| 2005–2009 | 395 | III–IV | 11 (8–14) | 158 | III–IV | 16 (10–22) | ||||

| 2010–2013 | 211 | 0–I | 59 (52–66) | 66 | 0–I | 62 (50–74) | ||||

| 2010–2013 | 147 | II | 53 (45–61) | 62 | II | 34 (21–47) | ||||

| 2010–2013 | 289 | III–IV | 18 (13–23) | 121 | III–IV | 28 (20–36) | ||||

aAdjusted for calendar period, age, sex, comorbidity, and tumor stage

b374 (19.5%) patients with gastric non-cardia adenocarcinoma and 69 (11%) patients with gastric cardia adenocarcinoma had missing tumor stage and are excluded from this analysis

Fig. 3.

Kaplan-Meier survival curve showing stage-specific observed 5-year survival for gastric non-cardia adenocarcinoma (a) and cardia adenocarcinoma (b) for patients operated 2005–2013

Nonoperated Patients

Among nonoperated patients with gastric non-cardia adenocarcinoma, the 5-year relative survival decreased slightly from 3% (95% CI 2–4%) to 2% (95% CI 1–3%) between the first and last calendar period (Table 1) (Fig. 2).

Risk Factors for 5-year Mortality in Gastric Non-cardia Adenocarcinoma

In the multivariable analysis of all patients with gastric non-cardia adenocarcinoma, the adjusted HR of mortality within 5 years of diagnosis was higher in earlier calendar periods (HR 1.11, 95% CI 1.05–1.17, first vs. last calendar period), older age groups (HR 1.65, 95% CI 1.56–1.74, age ≥ 80 vs. < 60 years), and in patients with more comorbidity (HR 1.38, 95% CI 1.31–1.45, comorbidity score ≥ 2 vs. 0), whereas sex did not clearly influence the risk of mortality (Table 2). The risk factors for mortality within 5 years of diagnosis were the same in operated and nonoperated patients (Table 2). In addition, in surgically treated patients, where tumor stage was available, higher tumor stage was a poor prognostic factor (HR 3.97, 95% CI 3.39–4.65, stage 0–I vs. III–IV). The results from the multiple imputation were similar to those in the complete case analysis (Tables 2, 3).

Survival Trends in Gastric Cardia Adenocarcinoma

The observed and relative survival data for gastric cardia adenocarcinoma were similar (Table 1), but only the latter are presented here.

All Patients

The 5-year relative survival in gastric cardia adenocarcinoma increased from 12% (95% CI 9.3–14%) to 18% (95% CI 15–21%) between the first and the last calendar period (Table 1).

Surgically Treated Patients

In patients who underwent resectional surgery for cardia adenocarcinoma, the 5-year relative survival increased from 21% (95% CI 17–25%) to 43% (95% CI 37–50%) between the first and the last calendar period (Table 1) (Fig. 2). Comparing the observed 5-year, tumor stage-specific survival in operated patients for the calendar period 2005–2009 with 2010–2013, the survival decreased from 65% (95% CI 54–76%) to 62% (95% CI 50–74%) for tumor stage 0-I, from 39% (95% CI 28–49%) to 32% (95% CI 21–47%) for tumor stage II, but increased from 16% (95% CI 10–22%) to 28% (95% CI 20–36%) for tumor stage III–IV (Table 3) (Fig. 3).

Nonoperated Patients

In nonoperated patients with cardia adenocarcinoma, the 5-year relative survival increased from 3% (95% CI 1–4%) to 5% (95% CI 3–7%) between the first and the last calendar period (Table 1) (Fig. 2).

Risk Factors for 5-year Mortality in Gastric Cardia Adenocarcinoma

In the multivariable analysis of all patients, operated patients, and nonoperated patients with gastric cardia adenocarcinoma, the prognostic factors were the same as those for gastric non-cardia adenocarcinoma, except for that females who underwent surgery had a slightly lower HR of 5-year mortality than operated males (HR 0.86, 95% CI 0.75–0.99; Table 2).

Discussion

This study indicates an unchanged overall survival in all patients with gastric non-cardia adenocarcinoma and an improved survival in all patients with cardia adenocarcinoma, but particularly in resected patients, during the last two decades in Sweden. These trends occurred despite of a gradually lower proportion of patients undergoing resectional surgery. In resected patients, the survival in non-cardia adenocarcinoma increased in all tumor stages but only in more advanced tumor stages in cardia adenocarcinoma. Higher tumor stage, older age, and comorbidity were poor prognostic factors.

Strengths of this study include the population-based design, enabled by the Swedish personal identity numbers combined with high-quality and complete nationwide registries of cancer, treatment, and mortality. The sample size was large enough to permit analyses of time trends in subgroups of patients and to assess prognostic factors. A weakness is potential tumor misclassification, mainly regarding cardia adenocarcinoma. However, some level of misclassification is unavoidable in any study examining this tumor, and the Swedish Cancer Registry has a reasonably good accuracy in the recording of this tumor.16 The lack of some clinical variables, such as use of neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatment is a limitation. Use of neoadjuvant treatment could improve the survival. However, few patients have definite chemoradiotherapy for gastric adenocarcinoma and the palliative strategy in the vast majority of nonoperated patients is mirrored by the very low 5-year survival rates. We had no data on hospital volume, but the ongoing centralization of gastric cancer surgery probably contributes to the positive trends. Data on tumour stage were partially missing in 19.5% of patients with non-cardia adenocarcinoma and in 11.0% in those with cardia adenocarcinoma. However, complete case analysis and multiple imputation analysis provided similar results, indicating that the missing data did not influence the findings.

Earlier studies examining the time trends in long-term prognosis in gastric adenocarcinoma report different results. A European registry-based study (EUROCARE-5) showed an overall slightly increased 5-year relative survival rate from 23 to 25% for all gastric cancer in 1999–2007 in Europe.13 A recent registry-based study of 150,700 patients diagnosed with gastric cancer in the United States found a slight improvement in the 5-year age-standardized survival from 26% in 2001–2003 to 29% in 2004–2009.25 A Korean registry-based study suggested greatly improving relative 5-year survival rates for all gastric cancers from 43% in 1993–1995 to 74% in 2010–2014.26 Unfortunately, none of these three studies separated non-cardia and cardia cancer or excluded other histological types than adenocarcinoma. On the other hand, a Dutch population-based study found that the overall 5-year survival decreased from 22 to 14% for gastric non-cardia adenocarcinoma and remained stable at 10% for cardia adenocarcinoma between 1990 and 2006.14

In contrast to the findings of the present study, which found a similar prognosis in non-cardia adenocarcinoma and cardia adenocarcinoma during the last study period, the majority of existing data globally, indicate a clearly lower 5-year survival for gastric cardia adenocarcinoma compared to gastric non-cardia adenocarcinoma.13,27,28 This discrepancy might be at least partly explained by the fact that the present study included a more recent time period than earlier studies. With a continued unchanged survival for gastric non-cardia adenocarcinoma and increasing survival for cardia adenocarcinoma, the reported survival rates will eventually become more equal also in other studies examining more recent data.

This study showed a clear decline in the proportion of patients undergoing resectional surgery in both gastric non-cardia and cardia adenocarcinoma, possibly explained by stricter selection of patients for surgery which might be driven by developments in diagnostic tools. It also showed a substantially improved prognosis over time for those who underwent surgery, likely explained by the better selection of patients for surgery, general introduction of multidisciplinary team meetings, centralization of services to fewer surgical centers, and a more widespread use of neo-adjuvant chemotherapy.29,30 The fact that the prognosis in all patients (operated and nonoperated combined) with non-cardia adenocarcinoma has been stable and even improved in cardia adenocarcinoma indicates that the selection for surgery is reasonably accurate. This is a slightly different trend from what was seen in the previous Swedish study examining survival trends in 1970–2008, where patients with non-cardia adenocarcinoma had a worsening prognosis. This change in survival is likely due to the improved prognosis for those operated as mentioned above. In Sweden, the surgical treatment of cardia adenocarcinoma has been increasingly centralized to larger centers, but this development has been slower for gastric non-cardia adenocarcinoma. The lack of improvement in non-cardia adenocarcinoma overall survival whilst the corresponding prognosis has improved in cardia adenocarcinoma indicates a need for further centralization for non-cardia adenocarcinoma. The on-going centralization in Sweden has led to that number of centers conducting surgery for gastric cardia cancer declined from more than 20 in 2007 to 7 in 2016, and from more than 50 in 2007 to 15 in 2016 for gastric non-cardia cancer.

More advanced tumor stage, earlier calendar period, older age, and more comorbidity were poor prognostic risk factors for both gastric non-cardia and cardia adenocarcinoma, which was expected and in line with previous research.

In conclusion, this population-based and nationwide Swedish study with long and complete follow-up indicates that the overall prognosis in patients with gastric non-cardia adenocarcinoma has remained stable during the last two decades, whereas the prognosis in gastric cardia adenocarcinoma has improved, and the 5-year survival is now equal between these groups in Sweden. For the decreasing proportion of patients who underwent resectional surgery, the survival has improved substantially, likely due to a more strict selection of patients for surgery. The lack of improvement in overall prognosis in non-cardia adenocarcinoma indicates a need for increased centralization to larger centers of these patients, similar to what has taken place for gastric cardia adenocarcinoma.

Funding

This work was supported by the Swedish Research Council and the Swedish Cancer Society. The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

References

- 1.Balakrishnan M, George R, Sharma A, Graham DY. Changing trends in stomach cancer throughout the world. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2017;19(8):36. doi: 10.1007/s11894-017-0575-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127(12):2893–2917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Cutsem E, Sagaert X, Topal B, Haustermans K, Prenen H. Gastric cancer. Lancet (London, England) 2016;388(10060):2654–2664. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30354-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ladeiras-Lopes R, Pereira AK, Nogueira A, et al. Smoking and gastric cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Cancer Causes Control CCC. 2008;19(7):689–701. doi: 10.1007/s10552-008-9132-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zali H, Rezaei-Tavirani M, Azodi M. Gastric cancer: prevention, risk factors and treatment. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2011;4(4):175–185. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colquhoun A, Arnold M, Ferlay J, Goodman KJ, Forman D, Soerjomataram I. Global patterns of cardia and non-cardia gastric cancer incidence in 2012. Gut. 2015;64(12):1881–1888. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.HACC group Gastric cancer and Helicobacter pylori: a combined analysis of 12 case control studies nested within prospective cohorts. Gut. 2001;49(3):347–353. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.3.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amini N, Spolverato G, Kim Y, et al. Clinicopathological features and prognosis of gastric cardia adenocarcinoma: a multi-institutional US study. Journal of surgical oncology. 2015;111(3):285–292. doi: 10.1002/jso.23799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arnold M, Karim-Kos HE, Coebergh JW, et al. Recent trends in incidence of five common cancers in 26 European countries since 1988: analysis of the European Cancer Observatory. European Journal of Cancer (Oxford, England: 1990) 2015;51(9):1164–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ang TL, Fock KM. Clinical epidemiology of gastric cancer. Singapore medical journal. 2014;55(12):621–628. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2014174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carcas LP. Gastric cancer review. Journal of carcinogenesis. 2014;13:14. doi: 10.4103/1477-3163.146506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Martel C, Forman D, Plummer M. Gastric cancer: epidemiology and risk factors. Gastroenterology clinics of North America. 2013;42(2):219–240. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2013.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson LA, Tavilla A, Brenner H, et al. Survival for oesophageal, stomach and small intestine cancers in Europe 1999–2007: Results from EUROCARE-5. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England: 1990) 2015;51(15):2144–2157. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dassen AE, Lemmens VE, van de Poll-Franse LV, et al. Trends in incidence, treatment and survival of gastric adenocarcinoma between 1990 and 2007: a population-based study in the Netherlands. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England: 1990) 2010;46(6):1101–1110. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lagergren J, Mattsson F. Diverging trends in recent population-based survival rates in oesophageal and gastric cancer. PloS one. 2012;7(7):e41352. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ekstrom AM, Signorello LB, Hansson LE, Bergstrom R, Lindgren A, Nyren O. Evaluating gastric cancer misclassification: a potential explanation for the rise in cardia cancer incidence. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1999;91(9):786–790. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.9.786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amin MB, Greene FL, Edge SB, The Eighth Edition AJCC, et al. Cancer Staging Manual: Continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more “personalized” approach to cancer staging. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2017;67(2):93–99. doi: 10.3322/caac.21388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A, et al. External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC public health. 2011;11:450. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lagergren K, Derogar M. Validation of oesophageal cancer surgery data in the Swedish Patient Registry. Acta oncologica (Stockholm, Sweden) 2012;51(1):65–68. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2011.633932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Armitage JN, van der Meulen JH. Identifying co-morbidity in surgical patients using administrative data with the Royal College of Surgeons Charlson Score. Br J Surg. 2010;97(5):772–781. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Swedish Causes of Death Registry: Bortfall och kvalitet i dödsorsaksregistret. 2010.

- 22.Cutler SJ, Ederer F. Maximum utilization of the life table method in analyzing survival. J Chronic Dis. 1958;8(6):699–712. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(58)90126-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brusselaers N, Vall A, Mattsson F, Lagergren J. Tumour staging of oesophageal cancer in the Swedish Cancer Registry: a nationwide validation study. Acta oncologica (Stockholm, Sweden) 2015;54(6):903–908. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2015.1020968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. Chicester: Wiley; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jim MA, Pinheiro PS, Carreira H, Espey DK, Wiggins CL, Weir HK. Stomach cancer survival in the United States by race and stage (2001-2009): Findings from the CONCORD-2 study. Cancer. 2017;123(Suppl 24):4994–5013. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jung KW, Won YJ, Oh CM, Kong HJ, Lee DH, Lee KH. Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, Survival, and Prevalence in 2014. Cancer Res Treat. 2017;49(2):292–305. doi: 10.4143/crt.2017.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zheng L, Wu C, Xi P, et al. The survival and the long-term trends of patients with gastric cancer in Shanghai, China. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:300. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao J, Zhao J, Du F, et al. Cardia and non-cardia gastric cancer have similar stage-for-stage prognoses after R0 resection: a large-scale, multicenter study in China. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;20(4):700–707. doi: 10.1007/s11605-016-3089-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Young JA, Shimi SM, Kerr L, McPhillips G, Thompson AM. Reduction in gastric cancer surgical mortality over 10 years: an adverse events analysis. Ann Med Surg (2012) 2014;3(2):26–30. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nelen SD, Heuthorst L, Verhoeven RHA, et al. Impact of centralizing gastric cancer surgery on treatment, morbidity, and mortality. J Gastrointest Surg. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]