Abstract

Dermacentor reticulatus is the second most important tick species in Poland. Although the north-eastern region of Poland is considered typical for D. reticulatus and is treated as a contiguous area of Eastern populations of the meadow ticks, the occurrence of this tick species in this region to date has been recorded as separate foci. The present report supplements data on the geographical distribution of D. reticulatus in urban and natural biotopes of north-eastern Poland (Warmia and Mazury province). In 2015–2017 (during the springtime activity of ticks) adult questing D. reticulatus were found in 13 of 25 monitored localities. Six sites are located in urbanized areas, within the administrative borders of the city of Olsztyn and seven sites are in natural biotopes in the central part of Warmia and Mazury. A total of 398 adult D. reticulatus ticks, including 257 females and 141 males, were collected. A comparison of data grouped according to urban and natural type of area revealed no statistical differences between them. Taking into account the habitat type, the mean tick density was the highest in open landscapes. The identification of new foci D. reticulatus in the endemic areas of Lyme borreliosis, tick-borne encephalitis and canine babesiosis is crucial for determining the risk of diseases transmitted by ticks and taking proper preventive measures.

Keywords: Dermacentor reticulatus, TICKS, Geographical distribution, Habitats, Poland

Introduction

The meadow tick D. reticulatus (Fabricius, 1974) is the second most abundant tick species in many parts of Europe after Ixodes ricinus. Due to the high adaptability of D. reticulatus to changing environmental conditions and a wide range of hosts, including livestock, domestic animals and humans, the veterinary-medical importance of this species has increased within in the last 20 years. Pathogens that can be transmitted to the host by D. reticulatus include the protozoa Babesia canis, bacteria of the genera Rickettsia and Anaplasma, and tick-borne encephalitis virus (Földvári et al. 2016). The significance of D. reticulatus in the transmission of Borrelia burgdorferi s.l. is still unclear, although the specific DNA of this pathogen has been detected in meadow ticks (Reye et al. 2013; Mierzejewska et al. 2015b; Kubiak et al. 2017; Zając et al. 2017), but this does not prove its role as a vector.

The geographical distribution of D. reticulatus in Europe ranges from northern Portugal, the western border of France and England through the countries of central Europe to Ukraine and to the east of Kazakhstan (Rubel et al. 2016). Until the 1980s the range of D. reticulatus was clearly divided between West-European and Eastern populations with an area from the Baltic Sea coast through central Germany, western Poland to the southern border of Hungary (Karbowiak 2014) where the meadow tick had never been reported. Nowadays, D. reticulatus shows a tendency of expansion into new areas in Germany (Dautel et al. 2006), Poland (Karbowiak and Kiewra 2010; Nowak 2011; Kiewra and Czulowska 2013; Mierzejewska et al. 2016), Slovakia (Bullová et al. 2009), the Czech Republic (Široký et al. 2011), Lithuania, Latvia (Paulauskas et al. 2015) and Romania (Chitimia-Dobler 2015) and has also been observed in countries of western Europe in locations where it had not been reported previously (Jongejan et al. 2015). The spread of D. reticulatus is influenced by many factors including climate changes due to global warming, changes in the way of using green areas, which contributes to the increase in the number and diversity of hosts as well as the development of tourism and transport between countries (Karbowiak 2014; Mierzejewska et al. 2017; Kloch et al. 2017).

Long-term monitoring of D. reticulatus in Poland has shown that the north-eastern and eastern parts of the country (east of the Vistula River) are endemic for this tick species (Szymański 1986; Siuda 1993; Bogdaszewska 2004; Biaduń 2011; Bartosik et al. 2011; Karbowiak 2014; Mierzejewska et al. 2016). In contrast, the western area of Poland between the Oder River (western border of the country) and the Vistula River, until the 1990s was considered to be free of this tick species (Szymański 1986; Siuda 1993; Bartosik et al. 2011; Karbowiak 2014). However, within the last two decades, due to the detection of new numerous localities of D. reticulatus, this part of Poland has been considered as an expansion area (Kadulski and Izdebska 2009; Karbowiak and Kiewra 2010; Nowak 2011; Kiewra and Czulowska 2013; Mierzejewska et al. 2016). The low genetic polymorphism between D. reticulatus from eastern Poland (eastern population), and newly emerged foci in western Poland, as well as considerable differences from the nearby German population, show that the foci in western Poland originated from the eastern D. reticulatus population (Kloch et al. 2017).

The present report supplements the data on the geographical distribution of D. reticulatus in the urban and natural biotopes of north-eastern Poland (Warmia and Mazury). Identification of new foci of D. reticulatus in the endemic areas of Lyme borrelioses, tick-borne encephalitis (TBE) and canine babesiosis (NIH-PZH; Mierzejewska et al. 2015b) is crucial for determining the risk of diseases transmitted by ticks and taking proper preventive measures.

Materials and methods

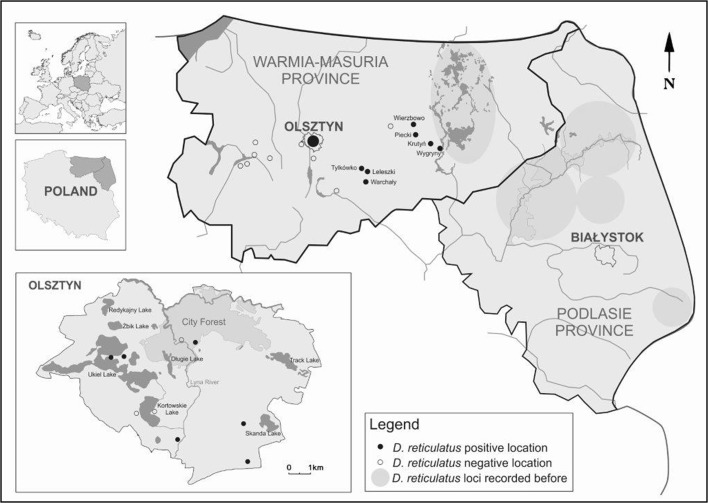

The occurrence of D. reticulatus was studied in 16 localities, across six districts of Warmia and Mazury from Szałkowo (N53°39′52.0″ E19°37′03.8″) in the west to Wygryny (N53°40′15.8″ E21°32′17.1″) in the east, in north-eastern Poland. Additionally, monitoring was carried out on the nine localities designated within the administrative boundaries of Olsztyn (88.0 km2), the capital of Warmia and Mazury (Table 1, Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Localities and the number of questing adult Dermacentor reticulatus ticks collected in 2015–2017 in the Warmia and Mazury region, north-eastern Poland

| Locality | Geographical coordinates | Habitats | Number of specimens | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |||||||||

| F | M | T | F | M | T | F | M | T | |||

| Olsztyn-City Forest | 53°47′51.9″N 20°28′35.0″E | Ecotone (meadow/forest) | 7 | 3 | 10 | 18 | 7 | 25 | 14 | 7 | 21 |

| Olsztyn-Brzeziny | 53°44′46.9″N 20°27′34.8″E | Open landscape | 7 | 8 | 15 | 10 | 8 | 18 | 45 | 22 | 67 |

| Olsztyn-Mazurskie | 53°45′39.4″N 20°31′06.1″E | Open landscape | 12 | 10 | 22 | 39 | 36 | 75 | 15 | 3 | 18 |

| Olsztyn-Teczowy Las | 53°43′54.2″N 20°29′50.5″E | Ecotone (grassy path/forest) | nc | 12 | 5 | 17 | 11 | 6 | 17 | ||

| Olsztyn-Ukiel Lake (public watering area) | 53°46′36.3″N 20°26′58.7″E | Ecotone (forested areas and lake shore vegetation | nc | 7 | 1 | 8 | nc | ||||

| Olsztyn-Ukiel Lake (Miła Bay) | 53°46′23.9″N 20°26′25.1″E | Ecotone (forested areas and lake shore vegetation) | nc | 2 | 0 | 2 | nc | ||||

| Tylkówko | 53o37′02.6 N 20o43′17.3E |

Open landscapes | nc | 16 | 10 | 26 | nc | ||||

| Leleszki | 53°37′31.9″N 20°49′51.7″E | Ecotone (grassy path/forest) | nc | 14 | 4 | 18 | 3 | 0 | 3 | ||

| Warchały (Barajnickie Lake) | 53°32′15.6″N 20°49′14.6″E | Ecotone (forested areas and lake shore vegetation) | nc | 4 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 2 | ||

| Wierzbowo (close Mrągowo) | 53°48′24.0″N 21°19′25.6″E | Ecotone (grassy path/forest) | nc | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 8 | ||

| Piecki | 53°48′01.7″N 21°19′33.1″E | Forest landscapes | nc | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Krutyń | 53°42′09.0″N 21°26′21.4″E | Forest landscapes | nc | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Wygryny (close Ruciane Nida) | 53°40′15.8″N 21°32′17.1″E | Ecotone (grassy path/forest) | nc | 6 | 3 | 9 | 3 | 1 | 4 | ||

F females, M males, T total, nc no ticks collected

Fig. 1.

Dermacentor reticulatus positive and negative locations in north-eastern Poland

Tick sampling was conducted in the springtime activity of ticks (March–May) of 2015–2017 in different types of habitat: (a) in forest landscapes (mature mixed and deciduous forests and its borders), (b) in ecotones (zones between grassy and forested areas such as paths near forest borders, and forested areas and lake shore vegetation, (c) in open landscapes (meadows that are sparsely covered by trees or bushes; pastures), (d) in the urban landscape (city parks).

Ticks were collected from vegetation using the flagging method in the daytime between 9 a.m. and 3 p.m. by two persons for at least 30 min at each site. A site was qualified as positive if questing D. reticulatus were collected directly from vegetation, and was negative when none of the ticks were present on the blanket. Collected ticks were preserved in 70% ethanol and in the laboratory were identified to the species, sex and developmental stage using taxonomic keys (Siuda 1993; Nowak-Chmura 2013).

For a given location, the density of D. reticulatus ticks was estimated by determining the number of ticks per 100 m2 for each individual flagging event at a specific site. The differences in the abundance of ticks between urban and natural areas and in the different types of a habitat were estimated on the basis of the density of ticks collected in April 2016 (a month when all study localities were monitored). The data were analyzed using the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test (α = 0.05). The test was conducted using the software package SPSS v.22.0 for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

In north-eastern Poland, in 2015–2017, adult questing D. reticulatus were found in 13 of 25 monitored localities (Table 1, Fig. 1). Six sites are located in urbanized areas, within the administrative borders of the city of Olsztyn. The remaining seven sites are in natural biotopes in the central part of Warmia and Mazury. The localities where D. reticulatus was detected are in Szczytno (Tylkówko, Leleszki, Warchały), Mrągowo (Wierzbowo, Piecki, Krutyń) and Pisz (Wygryny) districts.

D. reticulatus ticks in Warmia and Mazury were collected in habitats typical for this species. Both in urban and non-urban areas, the habitats of D. reticulatus are ecotones—areas between forest and grassy paths or forest and lake shore vegetation or open landscapes such as meadows (Table 1). Only the Piecki and Krutyń localities are covered by mature deciduous trees. Ticks were not found in dense mature deciduous, coniferous and mixed forests or in the city park at Lake Kortowskie in Olsztyn.

During 2015–2017 a total of 398 adult D. reticulatus ticks were collected, including 257 females and 141 males (Table 1). In April 2016, depending on the locality, the density of ticks per 100 m2 ranged from 0.2 (Wierzbowo, Piecki) to 6.3 (Olsztyn–Mazurskie) (Fig. 2). Comparison of data grouped according to urban and natural type of area revealed no statistical differences between them, although the D. reticulatus tick density was slightly higher in an urban area (Table 2). Taking into account the habitat type, the mean tick density was the highest in open landscapes with 4.08 ticks per 100 m2. The D. reticulatus abundance in this habitat was significantly different only in comparison with the ecotone between forest and lake shore vegetation (Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Dermacentor reticulatus density in the Warmia and Mazury region, north-eastern Poland (April, 2016)

Table 2.

Mann–Whitney U test of differences in occurrence of Dermacentor reticulatus between habitats in north-eastern Poland (April, 2016)

| Habitats | Mean density ± SD | Median (min–max) values | Mann–Whitney U | Asymptomatic significance (2-tailed) | Exact significance [2·(1-tailed significance)] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban | 2.72 ± 2.615 | 2.60 (0.33–9.50) | 30.0 | 0.441 | 0.479 |

| Natural | 1.87 ± 1.637 | 2.00 (0.20–4.33) | |||

| Ecotone (grassy path/forest) | 2.60 ± 1.383 | 2.60 (0.20–4.00) | 12.0 | 0.371 | 0.432 |

| Open landscape | 4.08 ± 3.270 | 3.00 (0.89–9.50) | |||

| Ecotone (grassy path/forest) | 2.60 ± 1.383 | 2.60 (0.20–4.00) | 5.0 | 0.088 | 0.109 |

| Ecotone (forested areas and lake shore vegetation) | 0.89 ± 0.754 | 0.61 (0.33–2.00) | |||

| Ecotone (grassy path/forest) | 2.60 ± 1.383 | 2.60 (0.20–4.00) | 1.5 | 0.104 | 0.111 |

| Forest landscapes | 0.40 ± 0.283 | 0.40 (0.20–0.60) | |||

| Open landscape | 4.08 ± 3.270 | 3.00 (0.89–9.50) | 1.0 | 0.027 | 0.032 |

| Ecotone (forested areas and lake shore vegetation) | 0.89 ± 0.754 | 0.61 (0.33–2.00) | |||

| Open landscape | 4.08 ± 3.270 | 3.00 (0.89–9.50) | 0.0 | 0.053 | 0.095 |

| Forest landscapes | 0.40 ± 0.283 | 0.40 (0.20–0.60) | |||

| Ecotone (forested areas and lake shore vegetation) | 0.89 ± 0.754 | 0.61 (0.33–2.00) | 2.0 | 0.926 | 0.533 |

| Forest landscapes | 0.40 ± 0.283 | 0.40 (0.20–0.60) |

Discussion

The presented report supplements the data on the distribution of D. reticulatus in north-eastern Poland belonging to the endemic area for tick-borne diseases (TBDs). According to Vu Hai et al. (2014), one of the current tools for estimating the burden and risk of TBDs in Europe is an assessment of a tick’s distribution in relation to biotope, landscape, urbanization, climate and a description of its extension and potential risk area. The region of north-eastern Poland is considered typical for D. reticulatus and should be treated as a contiguous area of eastern populations of the meadow tick (Bogdaszewska 2004). However, to date the occurrence of D. reticulatus in this region has been recorded as separated foci of this tick species. In the province of Podlasie, the occurrence of D. reticulatus has been documented in the Augustów Primeval Forest (the Augustów focus), the Knyszyn Primeval Forest (the Knyszyn focus), the Biebrza Basin (the Biebrza focus) (Siuda 1993; Karbowiak 2014) and in the Białowieża National Park (Biernat et al. 2014) (Fig. 1). In Warmia and Mazury, D. reticulatus were found in the Mazury Lake District and Piska Primeval Forest (the Mazury focus) which covers the Pisz, Giżycko, Węgorzewo and Mrągowo districts (Siuda 1993; Bogdaszewska 2004; Karbowiak 2014; Mierzejewska et al. 2015a, b, c, 2016).

A 3-year-long monitoring of tick prevalence in north-eastern Poland demonstrated that D. reticulatus was permanently present in the central part of Warmia and Mazury (Olsztyn subregion), outside of the areas associated with the Mazury Lake District where, according to Bogdaszewska (2004), the reservoirs of this species and its transmission are impacted by increasing populations of roe deer and elk. Our observations have shown that in this area D. reticulatus is found both in natural biotopes and in habitats situated in a city, often close to housing complexes, and its density is comparable in both environments. Accordingly, Mierzejewska et al. (2015a) reported that the average density of D. reticulatus was higher in sites located near the capital city of Warsaw compared with the semi-natural biotopes typical of the Mazury Lake District. The adaptation of this tick species to the environmental conditions of large cities is evidenced by data on the host-seeking adult specimens on vegetation and domestic animals (mainly dogs) in other cities in Poland, such as Warsaw (Zygner 2006; Zygner et al. 2009), Wrocław (the west of Poland) (Kiewra and Czulowska 2013; Król et al. 2016), Lublin and Lubartów (the east of Poland) (Biaduń 2011) and also Kyiv (Didyk et al. 2017), Budapest (Földvári et al. 2016) and Košice (Bullová et al. 2009). In cities, D. reticulatus is usually found near large natural forest complexes surrounding the city, such as our locations: Olsztyn–Tęczowy Las, Olsztyn-City Forest or Olsztyn–Ukiel; or other locations in Warsaw (Supergan and Karbowiak 2009; Zygner et al. 2009). It makes the migration of mammals and other animals from natural forests to city green areas possible, along with any accompanying parasites and attached ticks (Karbowiak 2014). In urbanized areas, an important role can be played by birds, as they serve as hosts of the young stages of ticks. Other host may be companion animals, such as dogs or horses (Földvári et al. 2016). This was confirmed in the studies carried out by Mierzejewska et al. (2015c) who demonstrated that in D. reticulatus endemic areas in Poland, dogs and livestock (cows, horses) are their main hosts.

In urban areas, small city parks are usually unfavourable locations for ticks (Földvári et al. 2011; Rizzoli et al. 2014; Paulauskas et al. 2015), e.g. Lake Kortowskie in Olsztyn, where no specimens of this species were collected, although this location presents a typical habitat for D. reticulatus. Most probably, it results from the lack of large mammalian hosts and regular maintenance of greeneries (mowing, leaf raking). The ways in which the green areas that are D. reticulatus habitats are used significantly impacts a reduction in the density of this species (Mierzejewska et al. 2017). In the Warmia and Mazury region, meadows that were regularly harvested or post-fire sites have demonstrated a substantially lower density of D. reticulatus ticks in comparison with the adjacent undisturbed fallow lands. According to the author, it proves that an increase in the surface of fallows and changes in the methods of land usage (ceasing extensive land burning) will increase the number of habitats that are favourable for meadow ticks in Poland. This is further supported by the highly fragmented landscape within a large patch of homogeneous vegetation in proximity to permanent watercourses or reservoirs. The identified D. reticulatus habitats in north-eastern Poland confirm this relation. Most described habitats consist of untreated green wastelands that are often located at the border of forest and grass pathways or lakeside greeneries. In turn, the forest habitats, such as Krutyń, are situated near lakes and may be a part of game animal water tracks.

In north-eastern Poland, both in the urban areas and natural biotopes the presence of D. reticulatus ticks demonstrated in the study increases the risk of tick-borne diseases in humans and animals. It is thus warranted to monitor tick distribution and to determine the level of pathogen contamination in ticks in such areas, which is important from both medical and veterinary points of view.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ambros A. and Zarzycka K. for assistance in tick collection and Tański A. for drawing the map (Fig. 1).

Funding

This study was funded by the Faculty of Health Sciences University of Warmia and Mazury in Olsztyn, Poland (Grant No. 62.610.001-300).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- Bartosik K, Wiśniowski Ł, Buczek A. Abundance and seasonal activity of adult Dermacentor reticulatus (Acari: Amblyommidae) in eastern Poland in relation to meteorological conditions and the photoperiod. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2011;18:340–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biaduń W. New habitats of Dermacentor reticulatus (Fabricius, 1794) in the Lublin region. Polish J Environ Stud. 2011;20:263–266. [Google Scholar]

- Biernat B, Karbowiak G, Werszko J, Stańczak J. Prevalence of tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV) RNA in Dermacentor reticulatus ticks from natural and urban environment, Poland. Exp Appl Acarol. 2014;64:543–551. doi: 10.1007/s10493-014-9836-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdaszewska Z. Występowanie i ekologia kleszcza łąkowego Dermacentor reticulatus (Fabricius, 1794) w ognisku mazurskim. I. Określenie obecnego zasięgu występowania (Range and ecology of Dermacentor reticulatus (Fabricius, 1794) in Mazuria focus. I. Defining current range) Wiadomości Parazytol. 2004;50:727–730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullová E, Lukáň M, Stanko M, Peťko B. Spatial distribution of Dermacentor reticulatus tick in Slovakia in the beginning of the 21st century. Vet Parasitol. 2009;165:357–360. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2009.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitimia-Dobler L. Spatial distribution of Dermacentor reticulatus in Romania. Vet Parasitol. 2015;214:219–223. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2015.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dautel H, Dippel C, Oehme R, et al. Evidence for an increased geographical distribution of Dermacentor reticulatus in Germany and detection of Rickettsia sp. RpA4. Int J Med Microbiol. 2006;296:149–156. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2006.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Didyk YM, Blaňárová L, Pogrebnyak S, et al. Emergence of tick-borne pathogens (Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato, Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Ricketsia raoultii and Babesia microti) in the Kyiv urban parks, Ukraine. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2017;8:219–225. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Földvári G, Rigó K, Jablonszky M, et al. Ticks and the city: Ectoparasites of the Northern white-breasted hedgehog (Erinaceus roumanicus) in an urban park. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2011;2:231–234. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Földvári G, Široký P, Szekeres S, et al. Dermacentor reticulatus: a vector on the rise. Parasite Vectors. 2016;9:314. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1599-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jongejan F, Ringenier M, Putting M, Berger L, et al. Novel foci of Dermacentor reticulatus ticks infected with Babesia canis and Babesia caballi in the Netherlands and in Belgium. Parasite Vectors. 2015;8:232. doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-0841-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadulski S, Izdebska J. New data on distribution of Dermacentor reticulatus (Fabr.) (Acari, Ixodidae) in Poland. In: Buczek A, Błaszak Cz, editors. Arthropods. Invasions their control. Lublin: Liber; 2009. pp. 53–58. [Google Scholar]

- Karbowiak G. The occurrence of the Dermacentor reticulatus tick: its expansion to new areas and possible causes. Ann Parasitol. 2014;60:37–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karbowiak G, Kiewra D. New locations of Dermacentor reticulatus ticks in Western Poland: the first evidence of the merge in D. reticulatus occurrence areas? Wiadomości Parazytol. 2010;56:333–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiewra D, Czulowska A. Evidence for an increased distribution range of Dermacentor reticulatus in south-west Poland. Exp Appl Acarol. 2013;59:501–506. doi: 10.1007/s10493-012-9612-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloch A, Mierzejewska EJ, Karbowiak G, et al. Origins of recently emerged foci of the tick Dermacentor reticulatus in central Europe inferred from molecular markers. Vet Parasitol. 2017;237:63–69. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2017.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Król N, Obiegala A, Pfeffer M, et al. Detection of selected pathogens in ticks collected from cats and dogs in the Wrocław Agglomeration, South-West Poland. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9:351. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1632-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubiak K, Sielawa H, Tylkowska A et al (2017) Prevalence of tick-borne pathogens in questing Dermacentor reticulatus (Fabr. 1794) ticks in north-eastern Poland. In: The XVI conference of Ukrainian scientific society of parasitologists (abstracts), 18–21 September, 2017, Lviv, Ukraina, p 103

- Mierzejewska EJ, Alsarraf M, Behnke JM, Bajer A. The effect of changes in agricultural practices on the density of Dermacentor reticulatus ticks. Vet Parasitol. 2015;211:259–265. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2015.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mierzejewska EJ, Pawełczyk A, Radkowski M, et al. Pathogens vectored by the tick, Dermacentor reticulatus, in endemic regions and zones of expansion in Poland. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:490. doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-1099-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mierzejewska EJ, Welc-Falęciak R, Karbowiak G, et al. Dominance of Dermacentor reticulatus over Ixodes ricinus (Ixodidae) on livestock, companion animals and wild ruminants in eastern and central Poland. Exp Appl Acarol. 2015;66:83–101. doi: 10.1007/s10493-015-9889-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mierzejewska EJ, Estrada-Peña A, Alsarraf M, et al. Mapping of Dermacentor reticulatus expansion in Poland in 2012–2014. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2016;7:94–106. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2015.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mierzejewska EJ, Estrada-Peña A, Bajer A. Spread of Dermacentor reticulatus is associated with the loss of forest area. Exp Appl Acarol. 2017;72:399–413. doi: 10.1007/s10493-017-0160-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIH-PZH Infectious diseases and poisonings in Poland in 2013–2016. Natl Inst Public Heal-Natl Inst Hyg-Dep Epidemiol http://www.pzh.gov.pl/oldpage/epimeld/index_p.htm

- Nowak M. Discovery of Dermacentor reticulatus (Acari: Amblyommidae) populations in the Lubuskie Province (Western Poland) Exp Appl Acarol. 2011;54:191–197. doi: 10.1007/s10493-010-9422-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak-Chmura M. Fauna kleszczy (Ixodida) Europy Środkowej. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu Pedagogicznego; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Paulauskas A, Radzijevskaja J, Mardosaite-Busaitiene D, et al. New localities of Dermacentor reticulatus ticks in the Baltic countries. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2015;6:630–635. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2015.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reye AL, Stegniy V, Mishaeva NP, et al. Prevalence of tick-borne pathogens in Ixodes ricinus and Dermacentor reticulatus ticks from different geographical locations in Belarus. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e54476. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzoli A, Silaghi C, Obiegala A, et al. Ixodes ricinus and its transmitted pathogens in urban and peri-urban areas in Europe: new hazards and relevance for public health. Front Public Heal. 2014;2:251. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2014.00251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubel F, Brugger K, Pfeffer M, et al. Geographical distribution of Dermacentor marginatus and Dermacentor reticulatus in Europe. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2016;7:224–233. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2015.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Široký P, Kubelová M, Bednář M, et al. The distribution and spreading pattern of Dermacentor reticulatus over its threshold area in the Czech Republic: How much is range of this vector expanding? Vet Parasitol. 2011;183:130–135. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siuda K (1993) Kleszcze Polski (Acari: Ixodida). Systematyka i rozmieszczenie część II. (Ticks (Acari: Ixodida) of Poland. Part II Taxonomy and Distribution) Polskie Towarzystwo Parazytologiczne, Warszawa

- Supergan M, Karbowiak G. The estimation scale of endangerment with tick attacks on recreational towns areas. Prz Epidemiol. 2009;63:67–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szymański S. Distribution of the tick Dermacentor reticulatus (Fabricius, 1794) (Ixodidae) in Poland. Acta Parasitol Pol. 1986;31:143–154. [Google Scholar]

- Vu Hai V, Almeras L, Socolovschi C, et al. Monitoring human tick-borne disease risk and tick bite exposure in Europe: available tools and promising future methods. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2014;5:607–619. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2014.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zając V, Wójcik-Fatla A, Sawczyn A, et al. Prevalence of infections and co-infections with 6 pathogens in Dermacentor reticulatus ticks collected in eastern Poland. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2017;24:26–32. doi: 10.5604/12321966.1233893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zygner W. Occurence of hard ticks in dogs from Warsow area. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2006;13:355–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zygner W, Górski P, Wçdrychowicz H. New localities of Dermacentor reticulatus tick (vector of Babesia canis canis) in central and eastern Poland. Pol J Vet Sci. 2009;12:549–555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]