Abstract

BACKGROUND/OBJECTIVES

obtaining one or more low scores across a battery of cognitive tests is common for non-demented older adults. We investigated the implications of this for diagnosing mild cognitive impairment (MCI).

DESIGN

observational longitudinal study

PARTICIPANTS

participants in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNIGO, ADNI2) labeled as normal controls (NC, n = 280) or MCI (n = 415) according to Petersen criteria were reclassified using both Jak/Bondi criteria and novel, number of impaired tests (NIT) criteria.

MEASUREMENTS

Diagnostic statistics and hazard ratios of progression to AD were compared across diagnostic criteria.

RESULTS

the NIT criteria were a better predictor of progression to AD than both Petersen and Jak/Bondi criteria, with optimal values of sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive value.

CONCLUSION

considering normal variability in cognitive test performance for diagnosing MCI may help to identify with greater certainty individuals at greatest risk of progression to AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, progression, dementia, diagnosis, mild cognitive impairment

INTRODUCTION

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is considered an intermediate stage between normal cognitive ageing and dementia1,2, with annual progression rates to dementia being 10–15% for clinical samples and 6%–10% for community samples3–5. Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common type of dementia in the elderly9, but a proportion of individuals with MCI never progress to AD6, and some revert to normal cognition7,8. Being able to accurately identify the individuals with MCI at greatest risk of progression to AD (risk-AD) is a research and clinical priority.

Standard criteria for MCI9,10 include the presence of objective cognitive impairment, but values for the prevalence of MCI are influenced by the definition of low test scores and how many are required11. These are important considerations given that normal cognitive variability means some healthy older adults will obtain low scores on one or more tests when multiple measures are administered12, with up to around 70% obtaining a score <1SD below the mean, and at least 30% obtaining a score <1.5SD below the mean13–15. The percentage of individuals obtaining a number of low scores is labeled the base rate of low scores (BRLS), and not accounting for this when interpreting performance on cognitive tests has clear implications for diagnosing MCI. This is illustrated by the finding that Petersen et al.9 criteria for MCI misclassified 24% of a sample compared to comprehensive criteria that required two scores ≤1SD within a cognitive domain16. While requiring two low scores goes some way to overcome the effects of normal cognitive variability, the optimal number of tests to use will depend upon the number and type of measures in the test battery.

Individuals with more low scores than expected for the BRLS would be more likely to have true impairment, rather than simply exhibiting normal variability in cognitive performance. Making allowances for low scores in line with the BRLS may help to minimize false positives when diagnosing MCI. The aim of this study was to test this idea, by comparing risk-AD of participants classified as having MCI using standard approaches, and when the BRLS is considered. In using the BRLS for diagnosing MCI, we expected to find individuals with MCI to have a higher risk-AD than normal controls, and better prediction of progression to AD compared to standard criteria.

METHODS

Data were obtained from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database (adni.loni.usc.edu), launched in 2003 as a public-private partnership, led by Principal Investigator Michael W. Weiner, MD. The first ADNI period (ADNI1) was updated in the ADNIGO and ADNI2 grant periods. Information about magnetic resonance imaging, positron emission tomography, other biological markers and clinical and neuropsychological assessment are available for more than 1,000 normal controls, individuals with MCI, and individuals with mild dementia17 (www.adni-info.org). The ethical committee at each participating site approved the project. All ADNI participants provided written consent.

ADNI dataset

Eligibility criteria for this study were a) normal control (NC) or MCI diagnosis at baseline, b) with cognitive and follow-up data. Progression to AD was classified using published criteria18,19. Participants in ADNI2 and ADNIGO were administered fewer tests than ADNI1 participants, and we excluded the latter to avoid differences in the BRLS because of the administration of additional tests. Baseline data were available for the Clock Drawing test (CD, copy and design), the Logical Memory subtest from the Wechsler Memory Scale – 3rd Ed. (LM, delayed recall), the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT, delayed recall, recognition), verbal fluency (animals), the Trail Making Test (TMT, Parts A and B), and the Boston Naming test (BNT).

Of 1,730 ADNI2/ADNIGO participants, 285 NCs and 471 participants with MCI had baseline/screening data. We excluded 27 individuals with MCI lacking follow-up data, and 36 individuals (5 NC and 29 MCI) having a follow-up diagnosis incongruent with previous status (e.g., NC at baseline and conversion from MCI to AD at follow-up without a previous progression from NC to MCI), leaving data available for 695 individuals (ADNI2: 584, ADNIGO: 111).

Diagnostic procedures

Classifications were made using four sets of criteria: Petersen et al.9, as originally used in ADNI, Winblad et al.10, Jak/Bondi20, and as based on the number of impaired tests (NIT criteria).

Petersen criteria

Clinical characterization of individuals in the ADNI database is detailed elsewhere17,21. All participants received physical and neurological examinations, screening laboratory tests, and provided blood samples for DNA and APOE testing. Criteria for MCI were subjective cognitive complaints (SCC), Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score ≥24, Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale score ≤0.5 (mandatory memory box score ≥0.5), abnormal education-corrected scores on one LM delayed recall paragraph, general cognition and functional performance remaining largely intact, and not meeting criteria for dementia. As objective cognitive impairment was based on LM test performance, all participants in the Petersen-MCI group were labeled as amnestic-MCI. Normal controls (Petersen-NC) had no memory complaints, CDR = 0, MMSE ≥24, normal education-corrected LM subtest scores, and no significant impairments in activities of daily living.

In order to apply each of Winblad’s, Jak/Bondi’s and NIT criteria, means and SDs of the NC group were used to calculate regression-based scores in both the NC and MCI groups, as per previous studies22,23. Raw scores were transformed to T-scores (M = 50, SD = 10) and regressed on age, sex and education. Residual z-scores [(Predicted T-score – Actual T-score) / standard error] were used to identify objective impairment

Winblad criteria

Both Winblad-NC and Winblad-MCI groups were the same as the Petersen groups, but the MCI group was subtyped as sd-aMCI if low scores (≤1.5SD) were found only in memory tests, and as md-aMCI if low scores were found on at least one non-memory test.

Jak/Bondi criteria

Three cognitive domains were used for MCI diagnosis24: attention/graphomotor speed (TMT A and B), language (semantic fluency, BNT), and verbal memory (RAVLT delayed recall and recognition). Criteria for MCI were a) a low score (<1SD) on both measures within at least one cognitive domain, or b) at least one low score (<1SD) in each of the three domains. Participants were separated into sd-aMCI, md-aMCI, sd-naMCI or md-naMCI according to their impairment pattern, with aMCI diagnosed when either each memory score or at least one score in each domain was <1SD.

NIT criteria

Participants were classified as NC or MCI using 9 scores derived from 6 tests (section ADNI dataset). MCI was diagnosed when the number of low scores equaled or exceeded the number of low scores obtained by the worst performing 10% (see12,13) of the Petersen-NC group. The NIT-MCI group was subtyped as sd-aMCI, md-aMCI, sd-naMCI and md-naMCI according to impairment patterns, with md-aMCI diagnosed when at least one of the low scores required for MCI was a memory score and sd-aMCI diagnosed when all the scores required for MCI were memory scores.

Statistical analysis

Age, gender, education and MMSE scores were compared between the original NC and the MCI groups, and the magnitude of significant differences was gauged from effect sizes25–27.

To test whether the number of low tests obtained by <10% of individuals gave the optimum cut-point for predicting progression to dementia, we produced a Receiver Operating Curve (ROC) using the 695 ADNI sample individuals with the number of low tests as the predictor variable and dementia status at final assessment as the outcome. The chosen cut-point for the number of low tests had the optimal sensitivity and specificity.

Cox proportional hazard regressions were used to analyze differences in risk-AD between MCI and NC groups, with age, sex, years of education and MMSE scores as covariates in each diagnostic criteria, separately and combined in the same regression. To test for multicollinearity, the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) was calculated for each of the diagnostic criteria in a regression model, with VIFs > 10 indicating multicollinearity28. Sensitivity (Sens), specificity (Spec), positive and negative predictive values (PPV, NPV) were calculated for each diagnostic criteria. Diagnostic agreement between the three sets of criteria was assessed with Cohen’sκ, with values between 0.00–0.20, 0.21–0.40, 0.41–0.60, 0.61–0.80, and 0.81–1.00 indicating slight, fair, moderate, substantial, and almost perfect agreement, respectively29. Given that all MCI participants in ADNI had verbal memory impairments, and the focus of this work was on aMCI, individuals classified as naMCI with either Jak/Bondi or NIT criteria were excluded from the analyses.

The annual progression rate (APR) was calculated by dividing the risk-AD by the mean years of follow-up. Alpha was set at .05. All analyses were conducted using SPSS v.22.

RESULTS

Petersen criteria

The Petersen-NC and Petersen-MCI groups included 280 and 415 individuals, respectively, with a mean follow up of 2.86 years (SD = 1.33) (see table 1 for data on demographics). Four individuals (1.43%) in the Petersen-NC and 90 (21.69%) in the Petersen-MCI group progressed to AD. Diagnostic statistics showed an unacceptably low specificity (45%), with more than half of those not progressing diagnosed with MCI (table 2). Proportional hazards for each of the diagnostic criteria are shown in Supplementary Figure S1a–c.

Table 1.

Differences in demographics between groups classified using Petersen et al. criteria9

| NC (n = 280) | MCI (n = 415) | t(693) | P values | Effect size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Age | 73.05 (6.13) | 71.87 (7.34) | 2.209 | .027 | 0.17 |

| Sex (f/m) | 150/130 | 181/234 | 6.645a | .010 | −0.09b |

| Education | 16.6 (2.56) | 16.2 (2.67) | 1.970 | .049 | 0.16 |

| MMSE | 29.02 (1.25) | 28.05 (1.69) | 8.211 | <.001 | 0.63 |

NC: normal control. MCI: mild cognitive impairment. MMSE: Mini-Mental state Examination

χ2(2,695).

Phi coefficient

Table 2.

Risk of progression to dementia. All the models include age, sex, years of education and MMSE scores as a covariates

| Petersen criteria | Winblad criteria | Jak/Bondi criteria | NIT criteria | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |

|

|

||||||||

| NC | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||

| MCI | 11.23 (4.08, 30.89) | <.001 | 11.23 (4.08, 30.89) | <.001 | 6.46 (3.75, 11.13) | <.001 | 7.29 (4.40, 12.07) | <.001 |

| sd-aMCI | - | 6.13 (2.08, 18.10) | .001 | 5.49 (3.04, 9.94) | <.001 | 9.26 (4.20, 20.38) | <.001 | |

| md-aMCI | - | 16.14 (5.80, 44.94) | <.001 | 8.29 (4.46, 15.41) | <.001 | 7.00 (4.18, 11.75) | <.001 | |

| Sens | 95.7 | 95.7 | 80.9 | 76.6 | ||||

| Spec | 45.9 | 45.9 | 66.4 | 76.9 | ||||

| PPV | 21.7 | 21.7 | 27.3 | 34.1 | ||||

| NPV | 98.6 | 98.6 | 95.7 | 95.5 | ||||

HR: hazard ratio. CI: confidence interval. NC: normal controls. MCI: mild cognitive impairment. Sens: sensitivity. Spec: specificity. PPV: positive predictive value. NPV: negative predictive value. Ref. reference category.

Winblad criteria

Within the MCI group, 173 individuals (41.69%) were classified as Winblad sd-aMCI and 242 (58.31%) as Winblad md-aMCI. Nineteen individuals (10.98%) in the Winblad sd-aMCI and 71(29.34%) in the Winblad md-aMCI progressed to AD. Winblad sd-aMCI and md-aMCI were both more likely to progress to AD than Winblad-NC, and md-aMCI was more likely to progress than sd-aMCI.

Jak/Bondi criteria

There were 417 participants classified as NC, 190 as aMCI (115 sd-aMCI, 75 md-aMCI), and 88 sd-naMCI. Fifty-eight (30.53%) participants in the Jak MCI group and 18 (4.32%) in the Jak NC group progressed to AD. Jak/Bondi criteria exhibited increased specificity but decreased sensitivity compared to Petersen criteria. Agreement between the Petersen and Jak/Bondi criteria was only fair (κ = .26, P < .001).

NIT criteria

The number of low scores obtained by Petersen-NC group members is shown in table 3. The closest cumulative percentage to a 10% cut-off was 7.86% with 3 or more low scores, and thus participants were labeled as MCI when the number of low scores was ≥3. This number of low tests was supported by the best levels of sensitivity and specificity (AUC = .827, P < .001, Sens: 76.6%, Spec: 76.9%). Using 2 or more low tests increased sensitivity (92.6%) but decreased specificity (55.9%), whereas using ≥4 low tests decreased sensitivity (51.1%) and increased specificity (88%).

Table 3.

Number of low scores in the ADNI NC group (low scores ≤1.5SD) out of 9 tests. N = 280

| N low scores | n | % | Cum % |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≥6 | 0 | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| 5 | 3 | 1.07% | 1.07% |

| 4 | 1 | 0.36% | 1.43% |

| 3 | 18 | 6.43% | 7.86% |

| 2 | 45 | 16.07% | 23.93% |

| 1 | 78 | 27.86% | 51.79% |

| 0 | 135 | 48.21% | 100.00% |

Bold cells indicate the <10% cut-off point. Cum %: cumulative percentage of individuals obtaining a number of low test scores from 0 to ≥6.

Memory category includes three variables: LM delayed recall, RAVLT delayed recall and recognition

Non-memory category includes six variables: CD test copy and drawing, TMT Parts a and B, semantic fluency and BNT.

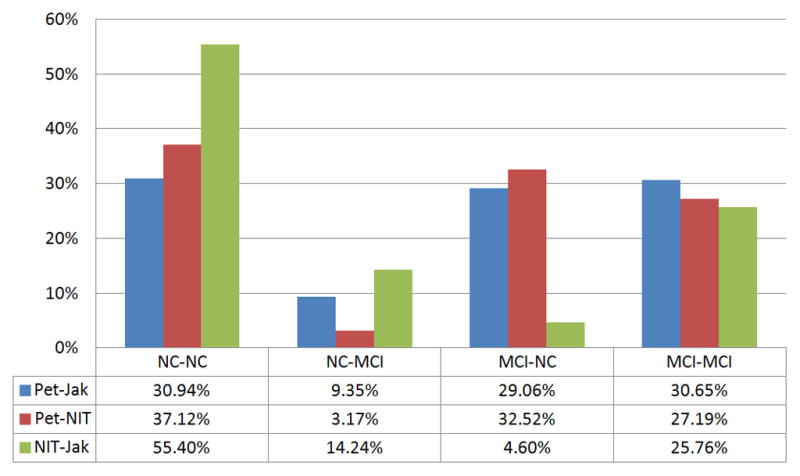

There were 484 individuals classified as NIT-NC and 211 as NIT-MCI (21 sd-aMCI, 180 md-aMCI, 10 md-naMCI). Twenty-two (4.55%) NIT-NC and 69 (34.33%) NIT-MCI progressed to AD. The NIT-MCI group as a whole, and both NIT sd-aMCI and NIT md-aMCI, had a greater risk-AD compared to NIT-NC. The NIT criteria gave a better balance between sensitivity and specificity, and also between PPV and NPV, compared to both Petersen and Jak/Bondi criteria. Agreement was only fair between NIT and Petersen criteria (κ = 0.34, P < .001), and moderate to substantial between NIT and Jak/Bondi criteria (κ = 0.59, P < .001) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Agreement in NC and MCI classifications between diagnostic sets. The first term in the NC-NC, NC-MCI, MCI-NC and MCI-MCI classifications pairs corresponds to the first term in diagnosis pairs.

Regression analysis suggested that multicollinearity among diagnostic criteria was not a concern. VIFs for Petersen, Jak/Bondi and NIT criteria were 1.19, 1.58 and 1.73 respectively. After excluding individuals with naMCI, the total sample size (NCs and aMCI) was 604. When in the same model, both Petersen (HR = 4.53, 95%CI: 1.59, 12.94, P = .005) and NIT criteria (HR = 3.88, 95%CI: 1.85, 8.12, P < .001) had higher risk estimates than Jak/Bondi criteria (HR = 2.08, 95%CI: 1.03, 4.19, P = .040). Table 4 shows the APR for each group in each diagnostic criteria.

Table 4.

Progression to Alzheimer’s disease by diagnosis criteria & group

| Progression rate (%) | 95% CI | APR (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Petersen et al.9 | NC | 1.43 | (0.04, 2.82) | 0.50 |

| MCI | 21.69 | (17.72, 25.65) | 7.58 | |

| Winblad et al.10* | sd-aMCI | 10.98 | (6.32, 15.64) | 3.84 |

| md-aMCI | 29.34 | (23.60, 35.08) | 10.26 | |

| Jak/Bondi 20 | NC | 4.32 | (2.37, 6.27) | 1.51 |

| MCI | 30.53 | (23.98, 37.07) | 10.67 | |

| sd-aMCI | 26.09 | (18.06, 34.11) | 9.12 | |

| md-aMCI | 37.33 | (26.39, 48.28) | 13.05 | |

| NIT criteria | ||||

| NC | 4.55 | (2.69, 6.40) | 1.59 | |

| MCI | 32.70 | (26.37, 39.03) | 11.43 | |

| sd-aMCI | 42.86 | (21.69, 64.02) | 14.99 | |

| md-aMCI | 33.33 | (26.45, 40.22) | 11.66 | |

APR: annual progression rate to Alzheimer’s disease. NC: normal control. MCI: mild cognitive impairment. sd: single-domain. md: multiple-domain. aMCI: amnestic MCI. CI: confidence interval

NC and MCI groups for Winblad criteria are the same as those of Petersen criteria.

DISCUSSION

This is, to our knowledge, the first work investigating the risk-AD when objective cognitive impairment is defined using the BRLS. Consistent with previous work12,13,30,31, we observed varying numbers of low scores among NCs reflecting normal cognitive variability. Using a bottom 10% of the sample cut-off we defined cognitive impairment as 3 or more low scores from among 9 tests administered. These NIT criteria showed moderate agreement in MCI and NC classifications with Jak/Bondi criteria, but more balanced values of sensitivity and specificity, as well as the highest PPV, compared to both Jak/Bondi and Petersen criteria.

The false negative NC diagnosis rate was 9.35% between Petersen and Jak/Bondi criteria (i.e., Petersen-NC identified as Jak/Bondi MCI), similar to the 7% error rate previously reported32. This rate was lower at 3.2% between Petersen and NIT criteria, in line with most cognitively healthy individuals obtaining a number of low scores because of normal variability. When NIT and Jak/Bondi criteria were compared, Jak/Bondi criteria showed a rate of false positive MCI diagnosis of 14.24% and a rate of false negative NC diagnosis of 4.6%. These findings, along with a lower PPV for Jak/Bondi than NIT criteria, suggest that the proportion of cognitively normal individuals misdiagnosed as having MCI is greater with Jak/Bondi criteria than with NIT criteria. Obtaining 2 low scores (<1.28SD) within the verbal memory domain is reportedly uncommon at 6.1%30. However, the percentage of cognitively normal individuals obtaining three or more low scores is reportedly 26.4% when a battery of five or more tests addresses different domains30, and 51.1% when the cut-off for abnormality is <1SD12. The use of <1SD in two tests per cognitive domain, or one test within each of three cognitive domains, may explain the higher rate of false positive and negative diagnoses for Jak/Bondi compared to NIT criteria (18.8%). The NIT criteria may be more sensitive to true cognitive impairment and more useful to identify individuals with a higher risk-AD.

We found a higher risk-AD for NIT sd-aMCI than for NIT md-aMCI, which contrasts with a higher rate of progression for md-aMCI than for sd-aMCI in a study using different tests and criteria to define md- and sd-aMCI, a memory-clinic sample, and a slightly shorter follow-up of 2 years33. Our results suggest that the severity of memory impairments, rather than the number of low test scores, might be primarily associated with the risk-AD. However, among the participants with md-aMCI, the most commonly impaired non-memory test was the BNT, followed by the clock-drawing test (see Supplementary table). This might indicate a profile of impairments in addition to pure episodic memory that increases the risk-AD, and that potentially relates to semantic memory and/or visuo-perceptual abilities, one or both of which is tapped by the BNT34 and clock drawing tests to some extent35. Future studies using multiple tests that assess each of these abilities will be needed to determine if a cognitive profile other than pure episodic memory impairment increases risk-AD. It would also be useful to expand the range of episodic memory tests beyond the aurally presented, verbal tests used in ADNI.

Our study’s use of regression-based scores is a strength22,23. However, there are limitations associated with the sample characteristics given that MCI classification in the ADNI database did not include cognitive abilities other than memory. In line with our findings, a potential outcome of using only one test for diagnosing MCI is false positives. Indeed, a previous report suggests that some participants diagnosed as MCI in the ADNI database have a cognitive profile similar to those labeled as NC when using MCI criteria that allow for some low scores36. Another limitation is using the original ADNI NC group to calculate regression-based z scores, given the chances of diagnostic errors36. To enhance generalizability, NIT criteria need to be evaluated in samples with non-amnestic profiles, with aMCI assessed using more and different memory tests, and with different educational levels, given low score numbers are strongly related to intellectual abilities15. It should be noted that the use of different tests is unlikely to impede the generalizability of our results, as long as a sufficient number of tests is used and a range of cognitive domains is covered. This is because our finding of a small number of low test scores being associated with normal cognitive functioning is similar to when different test batteries are used12–15.

We acknowledge that replication and further studies using different approaches are needed to validate our results. This could include testing the NIT criteria in samples other than the ADNI database, and analyzing the effects of other variables used in MCI diagnosis such as SCC or functional status. The use of biomarkers such as amyloid-b or tau protein load, as well as functional neuroimaging, will help to evaluate the accuracy of diagnoses achieved with NIT criteria.

An additional consideration is that our use of a ≤10% cut-off for defining abnormal performance is somewhat arbitrary, and could have implications for both the prevalence of MCI and the risk-AD5 that should be further explored. The NIT criteria showed a slightly higher APR to AD of 9.8–14% in MCI compared to 6.3–10% previously reported5. However, the studies reviewed in that report may have underestimated the true progression rate by not considering normal variability when diagnosing MCI. The optimal cut-point when using NIT criteria will depend upon characteristics of the particular test battery administered, including the total number of tests, their reliability, the pattern of inter-correlations between the tests, as well as the actual distribution of the abilities measured by the tests and the education level of the examinees15,38.

Our findings regarding the NIT criteria have clinical implications. Diagnosing an individual with MCI only when the number of low scores exceeds the bounds of normal variation requires a battery that generates a sufficient number of test scores. However, this might not always be practical, and only apply to patients close to the threshold for diagnosis and/or when there is more time and resources to administer a neuropsychological test battery rather than only a brief global or screening test. Another clinical approach to avoiding a false positive or “accidental” case of MCI could involve a second assessment39,40 to help determine whether low scores in the first were associated with normal variation or truly with MCI.

Taking account of the normal variability in a sample of healthy controls when several cognitive measures are included is straightforward when the BRLS is known or can be calculated, and could help reduce the heterogeneity in the risk-AD as compared with standard approaches.

Supplementary Material

Profile of cognitive impairments in multi-domain amnestic MCI

Survival function from Cox proportional regressions for each MCI diagnostic criteria.

Acknowledgments

Data collection and sharing for this project was funded by the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) (National Institutes of Health Grant U01 AG024904) and DOD ADNI (Department of Defense award number W81XWH-12-2-0012). ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and through generous contributions from the following: AbbVie, Alzheimer’s Association; Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation; Araclon Biotech; BioClinica, Inc.; Biogen; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; CereSpir, Inc.; Cogstate; Eisai Inc.; Elan Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; EuroImmun; F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd and its affiliated company Genentech, Inc.; Fujirebio; GE Healthcare; IXICO Ltd.; Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research & Development, LLC.; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development LLC.; Lumosity; Lundbeck; Merck & Co., Inc.; Meso Scale Diagnostics, LLC.; NeuroRx Research; Neurotrack Technologies; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Pfizer Inc.; Piramal Imaging; Servier; Takeda Pharmaceutical Company; and Transition Therapeutics. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research is providing funds to support ADNI clinical sites in Canada. Private sector contributions are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (www.fnih.org). The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer’s Therapeutic Research Institute at the University of Southern California. ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at the University of Southern California.

This work is part of a doctoral thesis (J.O-C.).

Conflict of interests: the authors have no conflict of interests to disclose

Author contributions: JO-C, MS-S, RF-C, JP-V and LC designed the study; JO-C, DL, PS and JC analyzed the data. JO-C, MS-S, RF-C, DL, PS, JC, JP-V and LC prepared the manuscript. All the authors accepted the manuscript in its final form

Sponsor’s role: this work had no sponsors

Footnotes

Impact statement: We certify that this work is novel

The potential impact of this research on clinical care or health policy includes the following: A more accurate diagnostic approach to identify individuals with MCI at a greater risk of progression to Alzheimer’s disease

Funding sources: none

References

- 1.Morris JC. Revised Criteria for Mild Cognitive Impairment May Compromise the Diagnosis of Alzheimer Disease Dementia. Arch Neurol. 2012;69(6):700–708. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.3152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petersen R. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J Intern Med. 2004;256(3):183–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gao S, Hendrie HC, Hall KS, Hui S. The relationships between age, sex, and the incidence of dementia and Alzheimer disease: a meta-analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55(9):809–815. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.9.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knopman DS, Boeve BF, Petersen RC. Essentials of the proper diagnoses of mild cognitive impairment, dementia, and major subtypes of dementia. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78(10):1290–1308. doi: 10.4065/78.10.1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitchell A, Shiri-Feshki M. Rate of progression of mild cognitive impairment to dementia - Meta-analysis of 41 robust inception cohort studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2009;119(4):252–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petersen R, Stevens JC, Ganguli M, Tangalos EG, Cummings JL, DeKosky ST. Practice parameter: Early detection of dementia: Mild cognitive impairment (an evidence-based review) Neurology. 2001;56(9):1133–42. doi: 10.1212/WNL.56.9.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xie H, Mayo N, Koski L. Identifying and Characterizing Trajectories of Cognitive Change in Older Persons with Mild Cognitive Impairment. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2011;31(2):165–172. doi: 10.1159/000323568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sachdev PS, Lipnicki DM, Crawford J, et al. Factors Predicting Reversion from Mild Cognitive Impairment to Normal Cognitive Functioning: A Population-Based Study. In: Ginsberg SD, editor. PLoS ONE. 3. Vol. 8. 2013. p. e59649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petersen R, Smith G, Waring S, Ivnik R, Tangalos T, Kokmen E. Mild cognitive impairment: Clinical characterization and outcome. Arch Neurol. 1999;56(3):303–308. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.3.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Winblad B, Palmer K, Kivipelto M, et al. Mild cognitive impairment--beyond controversies, towards a consensus: report of the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Intern Med. 2004;256(3):240–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kochan NA, Slavin MJ, Brodaty H, et al. Effect of different impairment criteria on prevalence of mild cognitive impairment in a community sample. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(8):711–722. doi: 10.1097/jgp.0b013e3181d6b6a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Binder LM, Iverson GL, Brooks BL. To err is human: “abnormal” neuropsychological scores and variability are common in healthy adults. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2009;24(1):31–46. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acn001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mistridis P, Egli SC, Iverson GL, et al. Considering the base rates of low performance in cognitively healthy older adults improves the accuracy to identify neurocognitive impairment with the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease-Neuropsychological Assessment Battery (CERAD- Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2015;265(5):407–417. doi: 10.1007/s00406-014-0571-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brooks B, Iverson G, White T. Substantial risk of “Accidental MCI” in healthy older adults: Base rates of low memory scores in neuropsychological assessment. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2007;13(03):490–500. doi: 10.1017/S1355617707070531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brooks B, Iverson G, Holdnack J, Feldman H. Potential for misclassification of mild cognitive impairment: a study of memory scores on the Wechsler Memory Scale-III in healthy older adults. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2008;14(3):463–78. doi: 10.1017/S1355617708080521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jak AJ, Bondi MW, Delano-Wood L, et al. Quantification of five neuropsychological approaches to defining mild cognitive impairment. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry Off J Am Assoc Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17(5):368–375. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31819431d5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aisen PS, Petersen RC, Donohue M, Weiner MW. Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative 2 Clinical Core: Progress and plans. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11(7):734–739. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McKhann GM, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: Report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group* under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34(7):939–939. doi: 10.1212/WNL.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):263–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bondi MW, Edmonds EC, Jak AJ, et al. Neuropsychological Criteria for Mild Cognitive Impairment Improves Diagnostic Precision, Biomarker Associations, and Progression Rates. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;42(1):275–289. doi: 10.3233/JAD-140276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petersen RC, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, et al. Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI): Clinical characterization. Neurology. 2010;74(3):201–209. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181cb3e25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parmenter BA, Testa SM, Schretlen DJ, Weinstock-Guttman B, Benedict RHB. The utility of regression-based norms in interpreting the minimal assessment of cognitive function in multiple sclerosis (MACFIMS) J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2010;16(01):6. doi: 10.1017/S1355617709990750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tabert MH, Manly JJ, Liu X, et al. Neuropsychological Prediction of Conversion to Alzheimer Disease in Patients With Mild Cognitive Impairment. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(8):916. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.8.916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jak AJ, Preis SR, Beiser AS, et al. Neuropsychological Criteria for Mild Cognitive Impairment and Dementia Risk in the Framingham Heart Study. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2016;22:1–7. doi: 10.1017/S1355617716000199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fritz CO, Morris PE, Richler JJ. Effect size estimates: Current use, calculations, and interpretation. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2012;141(1):2–18. doi: 10.1037/a0024338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olivier J, Bell ML. Effect sizes for 2×2 contingency tables. PloS One. 2013;8(3):e58777. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zakzanis K. Statistics to tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth Formulae, illustrative numerical examples, and heuristic interpretation of effect size analyses for neuropsychological researchers. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2001;16(7):653–667. doi: 10.1016/S0887-6177(00)00076-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’brien RM. A Caution Regarding Rules of Thumb for Variance Inflation Factors. Qual Quant. 2007;41(5):673–690. doi: 10.1007/s11135-006-9018-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Landis J, Koch G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Palmer B. Base Rates of “Impaired” Neuropsychological Test Performance Among Healthy Older Adults. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 1998;13(6):503–511. doi: 10.1016/S0887-6177(97)00037-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rotrou J, Wenisch E, Chausson C, Dray F, Faucounau V, Rigaud A-S. Accidental MCI in healthy subjects: a prospective longitudinal study. Eur J Neurol. 2005;12(11):879–885. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2005.01100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Edmonds EC, Delano-Wood L, Jak AJ, Galasko DR, Salmon DP, Bondi MW. for the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, editor. “Missed” Mild Cognitive Impairment: High False-Negative Error Rate Based on Conventional Diagnostic Criteria. In: Brandt J, editor. J Alzheimers Dis. 2. Vol. 52. 2016. pp. 685–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mitchell A, Arnold R, Dawson K, Nestor PJ, Hodges JR. Outcome in subgroups of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is highly predictable using a simple algorithm. J Neurol. 2009;256(9):1500–9. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-5152-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baldo JV, Arévalo A, Patterson JP, Dronkers NF. Grey and white matter correlates of picture naming: Evidence from a voxel-based lesion analysis of the Boston Naming Test. Cortex. 2013;49(3):658–667. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shulman KI. Clock-drawing: is it the ideal cognitive screening test? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;15(6):548–561. doi: 10.1002/1099-1166(200006)15:6<548::aid-gps242>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Edmonds EC, Delano-Wood L, Clark LR, et al. Susceptibility of the conventional criteria for mild cognitive impairment to false-positive diagnostic errors. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11(4):415–424. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Didic M, Felician O, Barbeau EJ, et al. Impaired Visual Recognition Memory Predicts Alzheimer’s Disease in Amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2013;35(5–6):291–299. doi: 10.1159/000347203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brooks B, Iverson G. Comparing Actual to Estimated Base Rates of “Abnormal” Scores on Neuropsychological Test Batteries: Implications for Interpretation. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2010;25(1):14–21. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acp100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Duff K, Lyketsos CG, Beglinger LJ, et al. Practice Effects Predict Cognitive Outcome in Amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;19(11):932–939. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318209dd3a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hassenstab J, Ruvolo D, Jasielec M, Xiong C, Grant E, Morris JC. Absence of practice effects in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychology. 2015;29(6):940–948. doi: 10.1037/neu0000208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Profile of cognitive impairments in multi-domain amnestic MCI

Survival function from Cox proportional regressions for each MCI diagnostic criteria.