SUMMARY

The large yybP-ykoY family of bacterial riboswitches is broadly distributed phylogenetically. Previously, these gene-regulatory RNAs were proposed to respond to Mn2+. X-ray crystallography revealed a binuclear cation-binding pocket. This comprises one hexacoordinate site, with six oxygen ligands, which preorganizes the second, with five oxygen and one nitrogen ligands. The relatively soft nitrogen ligand was proposed to confer affinity for Mn2+, but how this excludes other soft cations remained enigmatic. By subjecting representative yybP-ykoY riboswitches to diverse cations in vitro, we now find that these RNAs exhibit limited transition metal ion selectivity. Among the cations tested, Cd2+ and Mn2+ bind most tightly, and comparison of three new Cd2+-bound crystal structures suggests that these riboswitches achieve selectivity by enforcing heptacoordination (favored by high-spin Cd2+ and Mn2+, but otherwise uncommon) in the softer site. Remarkably, the Cd2+- and Mn2+-selective bacterial transcription factor MntR also uses heptacoordination within a binuclear site to achieve selectivity.

eToc

Bachas and Ferré-D’Amaré demonstrate how the broad family of yybP-ykoY riboswitches use heptacoordination to selectively bind transition metal ions. Heptacoordination is further generalized as a convergent selectivity mechanism adopted by protein and RNA metalloregulators that sense similar transition metals.

INTRODUCTION

Transition metal ions have important cellular functions, as enzyme cofactors, structurally stabilizing metalloproteins, and in signal transduction and gene regulation mediated by metal ion-binding proteins (Foster et al., 2014; Palmer and Skaar, 2016; Que et al., 2015). At high concentrations, however, they can be toxic due to non-cognate interactions (Imlay, 2014; Nies, 2003). A variety of mechanisms have evolved to sense and regulate intracellular transition metal ion concentrations (Brown et al., 1998; O’Halloran, 1993), including metal ion-sensing transcription factors, metal ion importers and exporters, metal ion-detoxifying enzymes, and scavenger metalloproteins (Bruins et al., 2000; Chandrangsu et al., 2017; Brown et al., 1998).

Recently, several riboswitches have been identified that respond to intracellular metal ions (Brantl, 2006; Saunders and DeRose, 2016; Wedekind et al., 2017). Riboswitches are cis-acting gene-regulatory mRNA domains that are widespread in bacteria, where they typically couple cognate ligand binding in their aptamer domains to modulation of transcription, translation or RNA stability (Jones and Ferré-D’Amaré, 2017; Montange and Batey, 2008; Peselis and Serganov, 2014; Roth and Breaker, 2009). The M-box riboswitch controls the Mg2+ exporters MgtA and MgtE (Cromie et al., 2006; Dann et al., 2007), the NiCo riboswitch, selectively responds to Ni2+ and Co2+ (Furukawa et al., 2015), while the yybP-ykoY riboswitches have been shown to upregulate exporters in response to high Mn2+ concentrations (Auffinger et al., 2011; Price et al., 2015).

Because RNA is a polyanion, its folding is strongly dependent on cations, with polyvalent cations being particularly effective in structure stabilization (Auffinger et al., 2011; Draper, 2008; Draper et al., 2005; Ferré-D’Amaré and Winkler, 2011). Crystallographic analyses of metal ion-responsive riboswitches have illustrated some molecular strategies that give rise to selective cation binding. The M-box riboswitch binds a number of Mg2+ ions using non-bridging phosphate oxygens (NBPOs) as well as nucleobase oxygens (Dann et al., 2007). These hard (i.e., of limited polarizability) binding sites are not highly selective for Mg2+ over other hard cations, but the riboswitch achieves biological specificity because this is the only divalent cation whose intracellular concentration matches the modest affinity of the RNA. Structures of NiCo and yybP-ykoY riboswitches show that their cation binding sites include the N7 nitrogens of purines as ligands (Furukawa et al., 2015); Price et al., 2015). Nitrogen is a softer ligand than oxygen, and this may result in preferential binding of soft cations. However, how selectivity arises for particular soft cations present in the cell at comparable concentrations is unclear.

More than 1000 candidates of the yybP-ykoY element distributed across bacterial phyla have been identified, making the yybP-ykoY family of riboswitches one of the largest characterized to date (Barrick et al., 2004; Meyer et al., 2011). Long an “orphan” riboswitch, it was recently shown to respond to Mn2+ in vitro and in vivo, consistent with some of the members of the family being associated with the putative Mn2+ exporter MntP (Waters et al., 2011; Dambach et al., 2015; Price et al., 2015). We have now examined representative yybP-ykoY riboswitches in vitro, and found that rather than exhibiting strict Mn2+ specificity, these RNAs bind to and respond transcriptionally to a number of transition metal ions. Cd2+ and Mn2+ bound with the highest affinity, and structural analysis reveals a plastic cation binding site that preferentially recognizes these two cations not by their hardness, but by exploiting their ability to achieve heptacoordination. Unlike hexacoordination, heptacoordination is atypical among transition metal ions (Casanova et al., 2003). A metalloregulatory protein, MntR, also responds to Cd2+ and Mn2+, and previous crystallographic studies have shown that it also employs heptacoordination as a cation selectivity filter (Kliegman et al., 2006). Thus, a riboregulator and a metalloprotein have converged on the same mechanism for cation selectivity.

RESULTS

Various Transition Metal Ions Activate yybP-ykoY Riboswitches

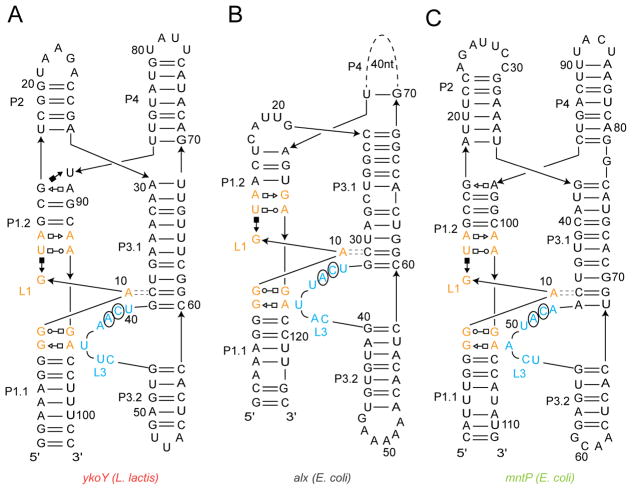

Previously, it was demonstrated through transcription termination experiments that the Escherichia coli mntP and the Lactococcus lactis ykoY riboswitches respond in vitro to Mn2+ (Dambach et al., 2015; Price et al., 2015). We examined whether three representative yybP-ykoY riboswitches (from the E. coli alx and mntP genes, and the L. lactis ykoY gene; hereafter alx, mntP, and ykoY) respond to other transition metal ions. The crystal structures of the mntP and ykoY aptamer domains have been reported (Price et al., 2015). Phylogenetic conservation indicates that yybP-ykoY riboswitch aptamer domains adopt a common fold consisting of two coaxial helical stacks joined by a 4-way junction (Figure 1). The transition metal ion-binding site results from association of the irregular loop L3 with the overwound, non-canonical L1 helix. The L1 sequence is highly conserved, and the principal sequence variation that is likely to impact cation recognition is in L3. Indeed, the mntP and ykoY aptamer domain structures are globally similar, with divergence in the cation binding site likely reflecting both, different L3 sequence and ion occupancy (Price et al., 2015). Unlike their aptamer domains, the expression platforms of yybP-ykoY riboswitches are highly variable; different members of this family of riboregulators control gene expression either transcriptionally or translationally.

Figure 1. Schematic Secondary Structure of Representative yybP-ykoY Riboswitch Aptamer Domains.

(A) Lactococcus lactis ykoY crystallization construct (Price et al., 2015). Lines with arrowheads denote chain connectivity. Canonical and non-canonical base pairs are indicated by the symbols of Leontis and Westhof (2001). Loops L1 and L3 are in orange and blue, respectively. GAAA tetraloops (gray) were introduced for crystallization. Parallel dashes denote A-minor interaction between L1 and L3.

(B) Predicted secondary structure of the Escherichia coli alx riboswitch aptamer domain.

(C) Predicted secondary structure of the E. coli mntP riboswitch aptamer domain. Residues in (B) and (C) are numbered using the ykoY convention (Price et al., 2015).

To examine the regulation of the alx, mntP, and ykoY riboswitches by diverse transition metal ions while avoiding confusion arising from sequence variability as well as their transcriptional or translational modes of action, we generated chimeric transcriptional reporters by mutating the L3 residues of the full-length L. lactis ykoY riboswitch to match those of the E. coli alx and mntP riboswitches (Figure 1; hereafter ykoYalx and ykoYmntP). By using a low-reduction, low-chelation transcription buffer, we were able to maximize the activity of divalent transition metal ions, while employing lower overall ion concentrations, thereby reducing their undesired inhibitory effects on RNA polymerase (Methods).

In the absence of transition metal ions, wild-type ykoY and the ykoYalx and ykoYmntP chimeras exhibited strong transcription termination (Figure 2; Figure S1). The first two yielded <10% full-length transcripts, while ykoYmntP was ~2-fold more permissive (Figure 2D). A higher basal level of read-through has been reported for the wild-type mntP riboswitch in vitro and in vivo (Dambach et al., 2015), suggesting that transplantation of the mntP L3 sequence into the ykoY riboswitch has endowed the ykoYmntP chimera with the metalloregulatory properties of mntP. Addition of 100 μM Ca2+ or Mg2+ did not result in more full-length transcript, confirming that the riboswitches are not responsive to these group II metal ions at such concentrations (Figure 2). In the presence of 100 μM of the transition metal ions Cd2+, Co2+, Cu2+, Fe2+, Mn2+, and Ni2+, the three reporters exhibited variable increases in transcriptional readthrough. Cd2+, Fe2+ and Ni2+ yielded transcriptional read-through similar to that observed for Mn2+ (~40%), and Co2+ and Cu2+ elicited the highest readthrough (although the transcripts are nonspecifically degraded in the presence of the latter). Under these conditions, addition of Zn2+ did not produce statistically significant increase in readthrough (Figure 2D).

Figure 2. In Vitro Riboswitch Activation by Diverse Transition Metal Ions.

(A) Autoradiogram of gel-electrophoretic analysis of ykoY transcription termination assays. “T” and “RT” denote terminated and read-through RNA products. 100 μM transition metal ions present where indicated.

(B) Autoradiogram of gel-electrophoretic analysis of ykoYalx chimera transcription termination assays.

(C) Autoradiogram of gel-electrophoretic analysis of ykoYmntP chimera transcription termination assays.

(D) Summary of transcription activation induced by divalent cations. Mean activation of ykoY, ykoYalx, and ykoYmntP are denoted by red, black and green bars. Error bars represent the standard deviation of duplicate experiments. (*) inidicates no significant difference (t-test, p > 0.5).

yybP-ykoY Riboswitches Bind Cd2+ and Mn2+ Comparably

We next used isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) to examine binding by the wild-type aptamer domains of alx, mntP, and ykoY to Co2+, Cd2+, Mn2+, and Ni2+. These ions were chosen because Co2+ and Ni2+ yielded high levels of riboswitch transcriptional activation in vitro (Figure 2), while Cd2+ has coordination chemistry very similar to that of Mn2+, the reported cognate activator of yybP-ykoY riboswitches. All titrations were in the presence of near-physiologic Mg2+ (5 mM), and with buffer-matched transition metal ion solutions. The excess of Mg2+ would minimize effects of RNA folding or non-cognate-site cation binding.

Co2+, Cd2+, Mn2+, and Ni2 all exhibited saturable binding to riboswitch aptamer domains (Figure 3A–F). The three RNAs displayed idiosyncratic reaction enthalpies. Thus, mntP and ykoY bound exothermically to all four ions, while alx displayed endothermic binding for Cd2+ and Mn2+ and exothermic binding for Co2+ and Ni2+ (Figure 3, Table S1). Isotherms were well fitted by a model with two independent binding sites (Methods). Overall, our ITC results are consistent with published live-cell and biochemical observations that different yybP-ykoY riboswitches are tuned to varying Mn2+ concentrations, covering as a family a 1000-fold range. Thus, mntP displays low nanomolar dissociation constant (Kd) for Mn2+, alx low micromolar Kd, and ykoY a Kd of 25 μM. The latter is comparable to what has been reported for the full-length ykoY riboswitch in transcriptional and SHAPE experiments (Price et al., 2015). Also in agreement with the trends observed by ITC, in vivo studies have shown that mntP is more sensitive to Mn2+ than alx (Dambach et al., 2015).

Figure 3. ITC Analysis of Divalent Cation Binding.

(A) Endothermic thermograms for alx aptamer domain binding to Mn2+ (purple) and Cd2+ (blue). Data were corrected by subtracting the heats of dilution from titrating transition metal ions into buffer. Black lines depict non-linear least square fits to a random, two-site binding model.

(B) Exothermic thermograms for mntP aptamer domain binding to Mn2+ and Cd2+.

(C) Exothermic thermograms for ykoY (C) aptamer domain binding to Mn2+ and Cd2+.

(D) Exothermic thermograms for alx aptamer domain binding to Co2+ (cyan) and Ni2+ (blue)..

(E) Exothermic thermograms for mntP aptamer domain binding to Co2+ (cyan) and Ni2+ (blue).

(F) Exothermic thermograms for ykoY aptamer domain binding to Co2+ (cyan) and Ni2+ (blue). Data in panels (B) through (F) were corrected and fitted as in (A)

(G) Comparison of mean dissociation constants for transition metal ions of mntP, alx, ykoY, ykoYalx aptamer domain RNAs. Error bars represent the standard deviation of duplicate experiments.

(H) Enthalpies associated with transition metal ion binding, color-coded as in G.

(I) Entropies associated with transition metal ion binding, color-coded as in G. (*) in panels (G) through (I) denote experiments that could not be fitted by non-linear regression.

Our ITC studies also demonstrate that yybP-ykoY riboswitches bind divalent transition metal ions other than Mn2+ with comparable affinity (Figure 3G, Table S1). Thus, the ykoY aptamer domain binds Cd2+, Co2+ and Ni2+ with dissociation constants (20 – 150 μM) similar to its modest affinity for Mn2+, while the alx aptamer domain binds Cd2+, Co2+ and Ni2+ with similar Kd’s (mean ~ 300 nM) that is actually ~10-fold smaller than what it exhibits for Mn2+. The aptamer domain of mntP bound to Co2+ and Ni2+ with Kd’s of 90 nM and 300 nM, respectively. This aptamer domain bound Cd2+ with a Kd of only 15 nM, which is within 2-fold of its affinity for Mn2+. Thus, of the three RNAs examined, mntP has the highest affinity for the metal ions tested. Our analyses indicate that yybP-ykoY riboswitches bind to transition metal ions with limited selectivity, and that these riboregulators do not distinguish markedly between the chemically similar Cd2+ and Mn2+ ions.

ITC analyses of the chimeric aptamer domains ykoYalx and ykoYmntP show that transplantation of the L3 sequences of alx and mntP into the ykoY framework has endowed the resulting RNAs with both the affinity and selectivity of the donor riboswitch (Figure 3G). Thus, ykoYalx exhibits comparable (~ 300 nM) affinity for Co2+ and Ni2+, and binds Mn2+ more weakly, and ykoYmntP has low nM dissociation constants for Cd2+ and Mn2+, and binds less tightly to Co2+ and Ni2+. The similarities between the ykoYalx and ykoYmntP chimeras and the wild-type alx and mntP aptamer domains extends to their specific endothermic or exothermic response to cation binding (Figure 3H), and quantitatively, to their entropic behavior (Figure 3I). This supports our hypothesis that the sequence of L3 determines the transition metal ion-binding properties of members of the yybP-ykoY riboswitch family.

Conformational Variability of the Transition Metal Ion Binding Site

We employed X-ray crystallography to examine how yybP-ykoY riboswitches recognize Cd2+, and to compare this to the Mn2+ recognition mechanism inferred from the reported 2.8 Å-resolution crystal structure of the ykoY aptamer domain crystallized in the presence of a mixture of Ba2+, Mg2+, and Mn2+ ions (Price et al., 2015). Highly ordered crystals of the ykoY aptamer domain that diffracted X-rays beyond 1.9 Å resolution could be grown in the presence of Ba2+, Cd2+, and Mg2+. Less ordered (resolution limit ~3.3 Å) crystals of the same RNA were obtained from solutions containing Cd2+, and Mg2+ as the only divalent cations. We also obtained crystals of the chimeric aptamer domains of ykoYalx and ykoYmntP that diffracted X-rays to 2.6 Å and 2.7 Å resolution, respectively. These RNAs crystallized from solutions containing Ba2+, Cd2+, and Mg2+ (ykoYalx) and Cd2+ and Mg2+ (ykoYmntP). All our crystal forms contain two independent RNA molecules in the crystallographic asymmetric unit (hereafter, molecules A and B). The structures were solved by molecular replacement and refined to the respective resolution limits, except for the low-resolution ykoY crystal form, which was not refined (Methods, Table 1, and Figure S2). The identity of the ions bound in the specific binding sites near L3 was established through inspection of anomalous difference Fourier syntheses, B-factor refinement, and comparison of crystals grown in the presence of different divalent cations. Overall, our structures illustrate a remarkable range of different coordination schemes for Cd2+ by riboswitches of the same family.

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| ykoY | ykoY | ykoY alx | ykoYmntP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cd2+ Ba2+ | Cd2+ | Cd2+ Ba2+ | Cd2+ | |

| Data collection | ||||

| Space group | P31 | C2221 | P31 | C2 |

| Cell dimensions | ||||

| a, b, c (Å) | 73.1 73.1 117.6 | 71.8 126.4 170.6 | 73.1 73.08.3 117.1 | 125.5 68.3 83.4 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90 90 120 | 90 90 90 | 90 90 120 | 90 98 90 |

| Resolution (Å) | 50.00–1.9 | 85.30–3.3 | 46.66 – 2.6 | 46.66 – 2.7 |

| Rmerge | 0.11 (0.82) | 0.17 (0.83) | 0.11(0.83) | 0.11 (0.80) |

| Rp.i.m | 0.05(0.74) | 0.09(0.44) | 0.06(0.49) | 0.07(0.50) |

| CC1/2 | 0.81(0.29) | 0.77(0.36) | 0.80(0.41) | 0.94(0.73) |

| <I>/<σ(I)> | 25.7 (1.0) | 16.15 (1.00) | 33.99 (1.36) | 17.6 (1.2) |

| Completeness (%) | 100 (99.9) | 99.9 (99.6) | 92.3 (99.0) | 99.0 (91.4) |

| Redundancy | 5.5 (4.4) | 6.0 (5.5) | 3.8 (3.2) | 3.7 (3.5) |

| Refinement | ||||

| Resolution (Å) | 43.1 – 1.9 | 46.6 – 2.6 | 46.6 – 2.7 | |

| No. reflections | 56199 (5601) | 22931 (2288) | 19173 (1767) | |

| Rwork/Rfree | 0.14(0.26)/0.17(0.29) | 0.22(0.43)/0.28(0.49) | 0.20(0.40)/0.25(0.43) | |

| No. atoms | 4710 | 4269 | 4247 | |

| RNA | 4250 | 4126 | 4114 | |

| Ligand/ion | 57 | 32 | 28 | |

| Water | 343 | 51 | 45 | |

| B-factors | ||||

| RNA | 38.8 | 60.8 | 79.4 | |

| Ligand/ion | 60.6 | 78.7 | 105.1 | |

| Water | 43.5 | 56.2 | 52.3 | |

| R.m.s deviations | ||||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.013 | 0.002 | 0.002 | |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.6 | 0.67 | 0.51 | |

Highest resolution shell is shown in parenthesis.

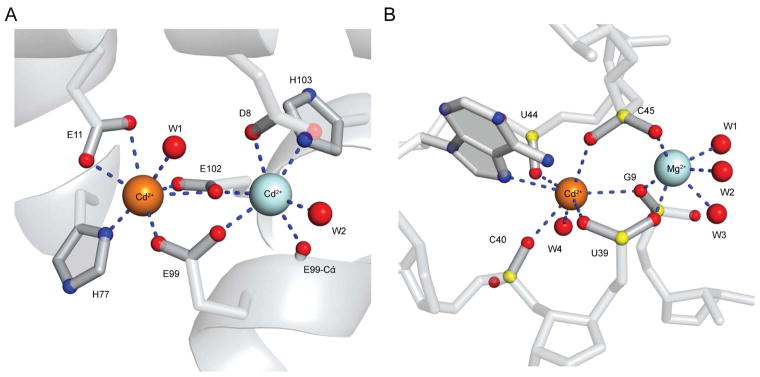

The anomalous difference Fourier maps for the ykoY aptamer domain crystals grown in the presence of Ba2+, Cd2+, and Mg2+ show three and two prominent peaks in the binding sites of molecules A and B, respectively (Figure S3A). The corresponding maps of the ykoY crystals grown in conditions containing only Cd2+ and Mg2+ show two peaks in each aptamer domain molecule (Figure S3B). Based on their presence in both crystal forms (and on comparable refined B-factors for the third cation of molecule A in the former crystal form), all sites were assigned as Cd2+. The binuclear and trinuclear Cd2+ binding modes of ykoY have distinctly different coordination geometries. In the binuclear case, one cation (MA, hereafter) is coordinated by five non-bridging phosphate oxygen (NBPO) atoms from residues in L1 and L3, and a water molecule completes its coordination sphere, while the other cation (MB, hereafter) is coordinated by five NBPOs and the N7 of residue A41. None of the ligands are shared between MA and MB, although the phosphates of G9, U39 and C45 use either of their two NBPOs to coordinate to the two bound Cd2+ ions (Figure 4A, Table S2). The trinuclear arrangement is distinctly different; MA is heptacoordinate and more hydrated (three inner-sphere water molecules, three NBPOs, and the O2 of U44), the six inner-sphere ligands of MB include the two exocyclic oxygen atoms of the nucleobase of U44, and MC, which adopts an irregular heptacoordinate scheme, is coordinated by four water molecules, the 2′-OH of A41, the NBPO of U43, and the O4 of U44 (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. Structural Plasticity of the Transition Metal Ion Binding Site.

(A) Ball-and-stick representation of the trinuclear transition metal ion-binding site in chain A of the Cd2+-bound ykoY aptamer domain crystal structure. Cd2+ and select water molecules are depicted as orange and red spheres, respectively. Dashed lines denote cation coordination.

(B) The binuclear transition metal ion-binding site in chain B of the Cd2+-bound ykoY aptamer domain crystal structure.

(C) The binuclear transition metal ion-binding site of the Cd2+-bound ykoYalx aptamer domain crystal structure.

(D) The binuclear transition metal ion-binding site of the Cd2+ and Mg2+-bound ykoYmntP aptamer domain crystal structure. Green sphere depicts Mg2+.

(E) Cartoon representation of the L1–L3 interface of chain A of the Cd2+-bound ykoY aptamer domain crystal structure. Nucleobases in cyan, purple and green participate in the A-minor motif, stack underneath the A-minor motif or are flipped out of the stack, respectively.

(F) The L1–L3 interface of chain B of the Cd2+-bound ykoY aptamer domain crystal structure, colored as in E.

(G) The L1–L3 interface of chain B of the Cd2+-bound ykoYalx aptamer domain crystal structure, colored as in E.

(H) The L1–L3 interface of chain B of the Cd2+ and Mg2+-bound ykoYmntP aptamer domain crystal structure, colored as in E.

(I) Structural superposition of the Cd2+ and Mg2+-bound ykoYmntP (orange) and the Mg2+ and Mn2+-bound ykoY (grey, PDB ID:4YI1; Price et al., 2015) structures. Least-squares fit performed using all non-hydrogen atoms.

(J) Analytical size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) analysis of mntP aptamer domain in the presence of various transition metal ions. Chromatograms are colored according to cations in the legend. The void volume of the column used is 8.20 ml.

Of the two aptamer domains in the asymmetric unit of the ykoYalx chimera, residues 39–44 of the L3 loop of molecule A were poorly ordered, but most NBPOs and both coordinated metal ions within the binuclear binding site could be built. We assigned Cd2+ to MB and Mg2+ to MA based on a single anomalous peak and B-factor refinement (Figure S3C). The L3 of molecule B was well-ordered, however, and the two anomalous peaks were assigned to Cd2+, based on B-factor refinement (Figure S3C). MA of this binuclear site is very similar to that of the ykoY binuclear site, except that at the current resolution limit, the water molecule that completes the octahedral coordination could not be resolved. MB is different in being heptacoordinate. While it shares most of the ligands with MB of the binuclear wild-type ykoY, both of the NBPOs of residue 44 (an adenine in the chimera, instead of the uridine in the wild-type) coordinate this Cd2+ ion (Figure 4C, Table S2).

In the case of ykoYmntP, which was crystallized in the presence of 5 mM Cd2+ and 100 mM Mg2+, only one anomalous peak was present in each of the two RNAs in the asymmetric unit (Figure S3D), while electron density was present for two bound cations (Figure S2D). Thus, for both crystallographically independent RNAs, MA was modeled as Mg2+ and MB as Cd2+. The two RNAs in the asymmetric unit, and their cation binding modes, are very similar, except for disorder in the distal portion of helix P4 in molecule B. For this RNA, MA is coordinated by three water molecules and the NBPOs of G9, A39 and C45. Unlike in the ykoY and ykoYalx structures, the NBPO of G8 and A10 do not participate in binding this cation. Notably, the G9 NBPO that coordinates MA in the ykoYmntP chimera is the pro-SP, rather than the pro-RP observed in the wild-type ykoY and the binuclear site of the ykoYalx chimera. Unlike in the wild-type ykoY, the Cd2+ in site MB of the ykoYmntP chimera is heptacoordinate. In addition to a water molecule and the N7 of A41, it is coordinated by five NBPOs. Uniquely among the cation binding sites described here, one of these NBPOs (the pro-SP oxygen of G9) is shared with MA, in a μ-oxo arrangement (Figure 4D).

Overall, the five ordered, crystallographically independent aptamer domains in our three crystal structures exhibit four different modes of Cd2+ coordination (Figure 4A,B,C,D), underscoring the conformational variability of the transition metal ion binding site of this family of riboswitches. This is not solely a function of the different L3 sequences present in our ykoY, ykoYalx, and ykoYmntP constructs, as the two conformations of the wild-type ykoY RNA display the most divergent (binuclear vs. trinuclear) cation recognition schemes.

In light of the presence of two or three Cd2+ ions per binding site in our crystals of ykoY, we reanalyzed the previously reported diffraction data for the Mn2+-bound ykoY structure (Price et al., 2015), and discovered further structural variability of the cation binding site. Anomalous difference Fourier maps calculated with the data of Price et al. (2015) show strong peaks in both the MA and MB sites (Figure S4A,B). In contrast, in our ykoYmntP structure, which is similar in resolution, anomalous features are localized to the MB site (Figure S3D). This, and re-analysis of the B-factors and anomalous scattering factors support two distinct binding modes: molecule A contains Mn2+ in site MA and Ba2+ in site MB while molecule B has Mn2+ in both sites (Figure S4C,D). These cation occupancies probably result from the presence of high concentrations of Ba2+ (20 mM) in the crystallization conditions of Price et al (2015). Our Cd2+-containing ykoYmntP crystals were grown in the presence of a large excess of Mg2+. Thus, this binuclear structure, with Mg2+ in MA and a transition metal ion in MB is likely the best available example of the physiologic activated state of a yybP-ykoY riboswitch.

Global Structural Correlates of Cation Coordination

The variability in coordination geometry among our three Cd2+-bound structures reflects subtle structural changes in the riboswitch aptamer domain. The transition metal ion-binding site arises from L1 and L3 associating through A-minor as well as cation-mediated interactions, and in each of our structures, the conformation of L3 is different, depending on whether residues 42–45 stack under A41 or flip out (Figure 4E, F, G. H). The positions of residues 39–41 are well conserved, in contrast, as they participate directly in formation of the A-minor motif. The various conformations of L3 are accompanied by near-rigid-body translations and rotations of the two coaxial helical stacks of the aptamer domain, which in turn give rise to varying degrees of global compaction (Figure S5A). Overall, the ykoYmntP structure showed the largest compaction, as a result of a 5 Å shift between P1 and P4 and a 6 Å shift between P1 and P3, relative to the to the Mn2+-bound ykoY structure (Figure 4I).

To determine if transition metal ion-dependent aptamer domain compaction occurs in solution we subjected the mntP aptamer domain, which has the highest Mn2+ and Cd2+ affinity among those examined, to size-exclusion chromatography. This RNA exists as a mixture of dimers and monomers, and the elution volume (Ve) of the monomer peak in the presence of transition metal ions correlates with the affinity of the RNA for those ions as determined by ITC (Figure 4J). In the presence of 1 mM Mg2+ alone, the monomer elutes at 9.71 ± 0.01 ml, but its Ve becomes 9.78 and 9.79 ml when 50 μM Cd2+ or Mn2+, respectively, are added. In the presence of Co2+, which bound more than 10-fold weaker than Cd2+ or Mn2+, the RNA eluted at 9.73 ml. Addition of 50 μM Ba2+ or Zn2+, which do not bind tightly, gave Ve of 9.70 and 9.69 ml, respectively. This shows that specific transition metal ion binding by the mntP aptamer domain produces hydrodynamic compaction proportional to cation affinity.

We also examined aptamer domain compaction in the presence of 1 mM MgCl2 and 4 mM transition metal ion (approximating our crystallization conditions). In these experiments, the transition metal ions induced substantially larger Ve changes relative to control (5 mM MgCl2; Figure S5B). Mn2+ and Ba2+ resulted in the largest Ve changes, while Cd2+ resulted in no change relative to MgCl2. RNA in buffer containing 2 mM each Ba2+ and Cd2+ eluted with Ve similar to when 4mM Mn2+ was included in buffer. Previously, ykoY riboswitch activation was observed in the absence of transition metal ions at high concentrations of MgCl2 (Price et al., 2015). The Ve’s observed in our experiments likely correspond to riboswitches compacted beyond their functional dynamic range, and suggest that concentrations of transition metal ions that exceed physiologic Mg2+ levels can over-compact the riboswitches and cause non-specific activation.

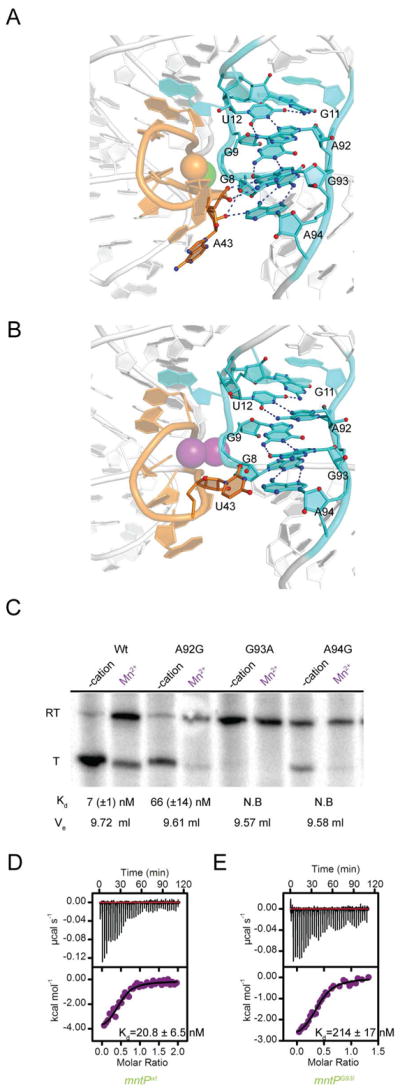

Key L1–L3 Interactions for High-affinity Cation Binding and Activation

How do the L3 sequences of different yybP-ykoY riboswitches control their transition metal ion affinity? A notable difference between the L3 of different riboswitches is the presence of either an adenine or an uracil at position 43 (Figure 1; ykoY numbering scheme of Price at al., 2015). Comparison of the structures of ykoYmntP bound to Cd2+ (with Mg2+ in MA; Figure 5A) and wild-type ykoY (Price et al., 2015) bound to Mn2+ in both MA and MB (Figure 5B) shows that the presence of adenine at position 43 of mntP gives rise to hydrogen bonding interactions between L1 and L3 that are absent in ykoY (Figure 5A,B). The nucleobase of A43 in the former stacks at the bottom of L3, allowing its extruded ribose and phosphate to interact with the Watson-Crick faces of G93 and A94 from L1 (Figure 5A). G93 uses its Hoogsteen face to pair with G9, and in the ykoYmntP structure, its Watson-Crick face makes a bidentate interaction with the phosphate of A43 (the pro-Rp and pro-SP NBPOs hydrogen bond to N1 and N2 of G93, respectively). A94 pairs with the sugar edge of G8 using its Hoogsteen face, and in the ykoYmntP structure, the 2′-OH of A43 is positioned to hydrogen bond to both, the N1 of A94 and the 2′-OH of G8. These L1–L3 tertiary interactions are absent from ykoY (Figure 5B), as the base of U43 flips out of L3 but only makes limited van der Waals interactions with L1 (closest contact is 3.6 Å between U43 N3 and G93 C2; a similar orientation of A43 might clash with L1). By extending the interaction between L1 and L3, A43 would facilitate greater compaction of the riboswitches (such as mntP) that bear it.

Figure 5. A Variable L3 Nucleotide Contributes to L1 Interactions and Riboswitch Activation.

(A) Cartoon representation of the interface between L1 (cyan) and L3 (orange) in the crystal structure of Cd2+- and Mg2+-bound ykoYmntP aptamer domain. Dashed lines depict hydrogen bonds.

(B) Interface between L1 (cyan) and L3 (orange) in the crystal structure of the Mn2+-bound ykoY aptamer domain (PDB ID:4YI1).

(C) Autoradiogram of gel-electrophoretic analysis of wild-type and mutant ykoYmntP transcription termination assays. Where noted, 400 M was present. Dissociation constants for Mn2+ μMnCl2 derived from ITC experiments with the corresponding aptamer domain, and SEC elution volumes (Ve) in the presence of the transition metal ion are indicated. N.B indicates that no binding enthalpy was detected by ITC.

(D) ITC thermogram of Mn2+ binding by the bimolecular construct of the wild-type mntP aptamer domain.

(E) ITC thermogram of Mn2+ binding by the bimolecular construct of the G93I mntP aptamer domain. In panels (D) and (E), dissociation constant (Kd) and standard deviation from duplicate experiments.

We examined the importance of L1–L3 association through single transition mutants at residues A92, G93 and A94, which are near-invariant in yybP-ykoY riboswitches and whose interactions within L1 are preserved in all structures. A92 uses its Hoogsteen face to make two hydrogen bonds with the Watson Crick face of U12, which forms a base triple with G11. The A92G mutation would disrupt one of these, and it results in a riboswitch that while retaining the ability to activate transcription in a Mn2+-dependent manner, binds this transition metal ion 10-fold weaker than the wild-type, and is also significantly less hydrodynamically compact in the presence of 5 mM MgCl2 (Figure 5C; since these mutants may pair alternatively in transcriptional switching, we made compensatory mutations in the terminator helix, Methods). The reduction in affinity is accompanied by a shift from exothermic to endothermic binding, and the unfavorable enthalpy is compensated by a 3-fold increase in entropy (Table S1). The G93A mutation would disrupt one of the two hydrogen bonds it makes with the base of G9, and also abolish the hydrogen bond it makes with the pro-Sp NBPO of A43. This mutant has lost transcriptional response to Mn2+, does not detectably bind transition metal ions by ITC, and has lost transition metal ion-dependent compaction. The presence of the N2 exocyclic amine in the A94G mutant would potentially give rise to steric clash with the ribose O4′ of A43. This mutant retains some transcriptional response to Mn2+, but has lost transition metal ion binding and compaction. These results indicate that the transition metal-ion response of yybP-ykoY riboswitches is highly sensitive to the precise atomic interactions between L1 and L3, even of nucleotides that do not directly participate in cation coordination.

The mutation G93A had the strongest impact on transition metal ion response among those we examined, but would disrupt both, one hydrogen bond within L1 and one between L1 and L3. To determine if the L1–L3 interaction mediated by the pro-Sp NBPO of G43 is functionally important, we generated the single-atom mutant in which the guanine is replaced by inosine. This G43I mutant aptamer domain was prepared by annealing a synthetic oligonucleotide to an RNA transcript (Methods). The corresponding wild-type control bimolecular RNA bound to Mn2+ with a dissociation constant of 20.8 ± 6.5 nM (Figure 5D). The G43I bimolecular construct bound Mn2+ over ten-fold weaker (214 ± 17 nM, Figure 5E), indicating that the single hydrogen bond donated by the pro-Sp NBPO of G43 contributes substantially to the ~3000-fold difference in affinity for the transition metal ion between ykoY and mntP, and loss of activity of the G93A mutant (Figure 5C) is not due solely to disruption of the structure of L1.

DISCUSSION

Based on crystallographic analyses of Mn2+ recognition by ykoY, which suggested that under physiologically relevant conditions the L1–L3 interfacial binding sites MA and MB would be occupied by Mg2+ and Mn2+, respectively, it was proposed that the presence of a lone soft ligand, the N7 of A41 in the latter site, was responsible for the Mn2+ selectivity of the riboswitch (Price et al., 2015). How a single soft ligand could yield selective binding of octahedral Mn2+ over other soft octahedrally coordinated cations has remained unclear. Our ITC analysis of three representative yybP-ykoY riboswitches demonstrates that these RNAs exhibit Kd’s from <10 nM to >20 μM for Mn2+. Unexpectedly, ITC also showed that these RNAs bind with comparable affinities to Cd2+, Co2+ and Ni2+. In particular, Cd2+ is bound with affinity equivalent, or higher, than Mn2+ by mntP and ykoY, and alx (Figure 3 and Table S1). Nonetheless, individual RNAs show preferential cation binding. In the case of mntP, which among the RNAs investigated has the highest transition metal ion affinity (Kd = 7 and 15 nM for Mn2+ and Cd2+, respectively), preference is 6- to 12-fold over Ni2+, and 20- to 43-fold over Co2+ (relative to Cd2+ and Mn2+, respectively, Table S1). Thus, yybP-ykoY riboswitches, while not specific for Mn2+, do have cation selectivity filters of varying degrees of effectiveness. The affinities observed lie within the critical toxicity concentration range for Cd2+-sensitive and Cd2+-resistant soil bacterial isolates (Kanazawa and Mori, 1996; Lin et al., 2016). Most of the candidate yybP-ykoY riboswitches identified bioinformatically (Barrick et al., 2004; Meyer et al., 2011), were present in soil or aquatic species, which are more vulnerable to the accumulation of various environmental toxic metals (Dambach et al., 2015). The majority of these putative riboswitches were associated with membrane proteins that are homologous to metal resistance transporters. Our discovery of broad yybP-ykoY riboswitch transition metal selectivity supports an expanded role for these riboregulators and their associated membrane proteins in bacterial metal ion homoeostasis.

Phylogenetic and structural analyses of yybP-ykoY riboswitches suggested that these riboregulators adopt a common architecture in which a 4-helix junction closely juxtaposes an irregular, overwound helix formed by L1 with the unpaired nucleotides of L3. The interface between these two elements creates the specific transition metal ion binding site, and is also bridged by a canonical type-I A-minor interaction (Nissen et al., 2001) between A10 and the C38•G61 base pair (ykoY numbering scheme). The nucleotides that form the non-canonical base pairs of L1, those that participate in the A-minor motif, and A41 (on the 5′ side of L3) are all highly conserved (Barrick et al., 2004). Because nucleotides on the 3′ side of L3 are more phylogenetically varied, we hypothesized that the identity of these may be primarily responsible for the range of transition metal ion affinities and specificities exhibited by yybP-ykoY riboswitches. To test this hypothesis, we generated chimeric riboswitches in which the L3 sequences of alx and mntP were grafted onto the ykoY framework. The resulting ykoYalx and ykoYmntP aptamer domains recapitulated in detail the ITC response of the L3 donors to Co2+, Cd2+, Mn2+, and Ni2+. Our experiments indicate that L3 is key in tuning the transition metal ion affinity and specificity of yybP-ykoY riboswitches, and justifies the use of chimeric riboswitches such as ykoYalx and ykoYmntP to compare the gene-regulatory response of riboswitches with divergent L3 sequences under one set of experimental conditions.

Within the conserved framework of their overall fold, the transition metal ion binding site of yybP-ykoY riboswitches is structurally plastic (Figure 4); the varying ionic radii of transition metal ions are unlikely to be primary determinants for selectivity. Our analyses demonstrate that L3 of the higher-affinity mntP riboswitch augments the L1–L3 interface distal to the specific transition metal ion site, and these interactions contribute to the affinity of the RNA for transition metals ions, as well as to the cation binding-induced compaction of the aptamer domain. Riboswitch aptamer domains compact concomitant with ligand or cation binding (Baird & Ferré-D’Amaré, 2010; Zhang et al., 2014), and comparison of yybP-ykoY riboswitch structures shows ykoYmntP bound to Cd2+ to be the most compact (Figure 4I and Figure S4B). Since mntP also exhibits the highest transition metal ion affinity and selectivity (Table S1), its mode of cation coordination (Figure 4D) likely corresponds to the most stable arrangement of the yybP-ykoY riboswitch ligand binding site among the different conformations sampled by the RNA.

A remarkable feature of MB of the binuclear cation binding site of the ykoYmntP riboswitch (occupied by Cd2+ in our structure) is the presence of seven ligands arranged as an approximate pentagonal bipyramid. In addition to A41 N7, five of these are NBPOs and one is a water. This water (W4, Figure 4D) has the longest coordination distance of the seven inner-sphere ligands (3.2 Å vs. 2.7 Å, on average, for the other six ligands), and therefore the Cd2+ ion is more precisely described as pseudo-heptacoordinate. Such geometry is well documented in high-spin Cd2+ complexes, but also for Mn2+ (Casanova et al., 2003). Since the riboswitch discriminates poorly (~2-fold) between these two transition metal ions, when bound to MB, Mn2+ probably will also be heptacoordinate. Heptacoordination is infrequent in complexes of other transition metal ions (Casanova et al., 2003). Thus, we propose that an important component of the cation selectivity of yybP-ykoY riboswitches is the preference for heptacoordination at the “soft” binding site MB. In this light, it is noteworthy that a crystallographically well-ordered water molecule with the approximate location of W4 of the ykoYmntP-Cd2+ complex is present even in hexacoordinate MB sites, where it lies outside of inner-coordination distance (Figure S6). Thus, the architecture of the RNA appears to be primed for facilitating pseudo-heptacoordination at MB.

Our discovery of pseudo-heptacoordination of the specifically bound transition metal ion of a yybP-ykoY riboswitch has a biological parallel in the structural mechanism of cation selection by the manganese transport regulator protein (MntR). Expression of the Mn2+ efflux pump MntP is controlled transcriptionally and translationally by MntR and the mntP riboswitch, respectively (Dambach et al., 2015). MntR also represses a Mn2+ importer when the intracellular concentration of the cation reaches toxic levels (Huang et al., 2017; Waters et al., 2011). MntR binds Cd2+ ions 1000-fold tighter than Mn2+, and although other transition metals such as Co2+ and Ni2+ bind the protein, only Cd2+ and Mn2+ relieve gene repression by MntR (Golynskiy et al., 2005; Lieser et al., 2003). The crystal structures of MntR bound to Mn2+ and Cd2+ demonstrate that in the activated state, the MntR dimer has two binuclear transition metal ion binding sites. Each of these comprises one hexacoordinate and one heptacoordinate cations (Figure 6A). In the latter, a high-spin Cd2+ or Mn2+, is coordinated by one soft nitrogen ligand (a histidine Nδ), five carboxylate oxygens, and one water molecule (Glasfeld et al., 2003; Kliegman et al., 2006), precisely the same types of ligands present in the high-spin MB site of the yybP-ykoY riboswitch (Figure 6B). The similarity extends to the presence of one μ-oxo oxygen (from a carboxylate and a phosphate, in the protein and the RNA, respectively). MntR is the most specific metal-responsive member of the DxtR/MntR family of transcription factors (McGuire et al., 2013); our analysis therefore demonstrates the convergent use of spin transition and atypical metal coordination geometry as the selectivity filter for a transcription factor and a metalloregulatory RNA that do not simply rely on softness or ionic radii for specific recognition.

Figure 6. Convergent Evolution of Transition Metal Ion Binding Protein and RNA Genetic Regulators.

(A) Ball-and-stick representation of the binuclear transition metal ion binding site of Cd2+-bound MntR protein (PDB ID: 2EV0; Kliegman et al., 2006). Pseudo-heptacoordinate and hexacoordinate cations are depicted as orange and cyan spheres, respectively.

(B) Ball-and-stick representation of the binuclear transition metal ion binding site of Cd2+-and Mg2+-bound ykoYmntP, oriented approximately and colored as in (A).

Crystal structures of metalloproteins have provided insight into metal ion selectivity. An important theme from such studies is the use of atypical coordination schemes coupled with structural restraints of the protein to enforce discrimination (Chen and He, 2008; Finney and O’Halloran, 2003; Ma et al., 2009). For instance, the metalloproteins CueR and ZntR from the MerR family of transcription regulators are similar in structure, but are specific for Cu+ and Zn2+, respectively (Finney and O’Halloran, 2003). In the case of CueR, a single metal ion is sterically restricted to linear geometry in the metal binding site, whereas ZntR uses a binuclear binding site that cooperatively binds two Zn2+ ions with tetrahedral geometry (Changela et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2003; Outten and O’Halloran, 2001). Their respective binding mechanisms explain how high specificity for the cognate metal ion and discrimination against other ions is achieved. Other atypical coordination schemes such as tricoordination and heptacoordination have been observed (Chen and He, 2008; Kliegman et al., 2006; Peariso et al., 2003; Xue et al., 2008). In all cases, atypical coordination is coupled to distinct protein conformational states required for activity. Our analysis of the yybP-ykoY riboswitches shows how a widespread class of riboregulators employs the same principles to achieve biological specificity.

STAR*METHODS

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCES SHARING

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact Adrian R. Ferré-D’Amaré: adrian.ferre@nih.gov

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

All RNA used in our studies was prepared by in vitro transcription or chemical synthesis. No animals or cell lines have been used in this work.

METHOD DETAILS

RNA synthesis

The twelve RNAs employed in this study (Key Resources Table) were prepared by in vitro transcription and purified by denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis as described (Xiao et al., 2008). Plasmids containing genes for all twelve riboswitches were purchased from Eurofins Scientific. 2 μg of plasmid DNA templates were amplified in 1 mL PCR reactions and transcribed in 5 mL T7 transcription buffer [25 mM Tris-HCl, 2 mM spermidine-HCl, 0.01% (v/v) Triton X-100, pH 8.0] containing 2.5 mM each ATP, UTP, CTP and GTP, 30 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 1 unit/mL inorganic pyrophosphatase (Sigma-Aldrich), and 100 μg/ml T7 RNA polymerase for 12 hrs. Riboswitch transcripts were then purified by electrophoresis on 10% polyacrylamide, 8 M urea gels, and electroeluted into TBE buffer. After purification, RNAs were washed in 1M KCl, desalted extensively and stored in aqueous solution at 4°C until use.

Key Resources Table.

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Chemicals | ||

| MgCl2 hexahydrate 99.997% trace metals basis | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat:255777 |

| MnCl2 >99% trace metals basis | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat:244589 |

| CdCl2 99.99% trace metals basis | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat:202908 |

| FeCl2 98% trace metals basis | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat:372870 |

| CoCl2 97% trace metals basis | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat:232696 |

| ZnCl2 99.99% trace metals basis | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat:229997 |

| NiCl2 99.99% trace metals basis | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat:451193 |

| BaCl2 99.9% trace metals basis | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat:342920 |

| CaCl2 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat:C4901 |

| RNA Constructs | ||

| RNA1 (Wild-type L. lactis ykoY aptamer domain used in ITC/SEC experiments) 5′GGCAAAGGGGAGUAGCGUCGGUAAGACCGAAACAAAGUC GUCAAUUCGUGAGAUUCUCACCGGCUUUGUUGACAUACUU AUGUAUGUUUAGCAAGACCUUUGCC3′ |

In Vitro transcription | N/A |

| RNA2 (Wild-type E. coli alx aptamer domain used in ITC/SEC experiments) 5′CCGGCAAAGGGGAGUAACUUCAUUGCCGGUCGAUCGUCAU UACGAUGUGUGAAAAAACACAUCCGGUCACCGGGCAACCCG AAAGGAAUACGCAGACGUAUUCCUUUUUUGUUGUAAGUGA GACCUUGCCGG3′ |

In Vitro transcription | N/A |

| RNA3 (Wild-type E. coli mntP aptamer domain used in ITC/SEC experiments) 5′UCATUUUGGGGAGUAGCCGAUUUCCAGAUUCCGGAAAUG UACGUGUCAACAUACUCGUUGCAAAACGUGGCACGUACGG ACUGAAUACUUUCAGUCAGGCGAGACCAUAUG3′ |

In Vitro transcription | N/A |

| RNA4 (ykoYalx chimeric aptamer domain used in ITC experiments) 5′GGCAAAGGGGAGUAGCGUCGGUAAGACCGAAACAAAGUC GUCAUUACGUGAGAUUCUCACCGGCUUUGUUGACAUACUU AUGUAUGUUUAGCAAGACCUUUGCC3′ |

In Vitro transcription | N/A |

| RNA5 (ykoYmntp chimeric aptamer domain used in ITC experiments) 5′GGCAAAGGGGAGUAGCGUCGGUAAGACCGAAACAAAGUC GACAUACUGUGAGAUUCUCACCGGCUUUGUUGACAUACUU AUGUAUGUUUAGCAAGACCUUUGCC3′ |

In Vitro transcription | N/A |

| RNA6 (Wild-type L. lactis ykoY aptamer domain used in crystallization) 5′GAAAGGGGAGUAGCGUCGGGAAACCGAAACAAAGUCGUC AAUUCGUGAGGAAACUCACCGGCUUUGUUGACAUACGAAA GUAUGUUUAGCAAGACCUUUCC3′ |

In Vitro transcription | N/A |

| RNA7 (ykoYalx chimeric aptamer domain used in crystallization) 5′GAAAGGGGAGUAGCGUCGGGAAACCGAAACAAAGUCGUC AUUACGUGAGGAAACUCACCGGCUUUGUUGACAUACGAAA GUAUGUUUAGCAAGACCUUUCC3′ |

In Vitro transcription | N/A |

| RNA8 (ykoYmntP chimeric aptamer domain used in crystallization) 5′GAAAGGGGAGUAGCGUCGGGAAACCGAAACAAAGUCGAC AUACUGUGAGGAAACUCACCGGCUUUGUUGACAUACGAAA GUAUGUUUAGCAAGACCUUUCC3′ |

In Vitro transcription | N/A |

| RNA9 (mntP A92G aptamer domain used in ITC/SEC experiments) 5′GGAUUUGGGGAGUAGCCGAUUUCCAGAUUCCGGAAAUGU ACGUGUCAACAUACUCGUUGCAAAACGUGGCACGUACGGAC UGAAUACUUUCAGUCAGGCGGGACCAUAUCC3′ |

In Vitro transcription | N/A |

| RNA10 (mntP G93A aptamer domain used in ITC/SEC experiments) 5′GGAUUUGGGGAGUAGCCGAUUUCCAGAUUCCGGAAAUGU ACGUGUCAACAUACUCGUUGCAAAACGUGGCACGUACGGAC UGAAUACUUUCAGUCAGGCGAAACCAUAUCC3′ |

In Vitro transcription | N/A |

| RNA11 (mntP A94G aptamer domain used in ITC/SEC experiments) 5′GGAUUUGGGGAGUAGCCGAUUUCCAGAUUCCGGAAAUGU ACGUGUCAACAUACUCGUUGCAAAACGUGGCACGUACGGAC UGAAUACUUUCAGUCAGGCGAGGCCAUAUCC3′ |

In Vitro transcription | N/A |

| RNA12 (transcript strand used for annealed bimolecular constructs) 5′GGGCAUUUGGGGAGUAGCCGAUUUCCAGAUUCCGGAAAU GUACGUGUCAACAUACUCGUUGCAAAACGUGGCACGUACG GACUGAAUACUUUC3′ |

In Vitro transcription | N/A |

| RNA13 (wild-type synthetic oligonucleotide for annealed bimolecular construct) 5′AGTCAGGCGAGACCATATGCCC3′ |

Dharmacon | N/A |

| RNA14 (G93I synthetic oligonucleotide for annealed bimolecular construct; I denotes inosine) 5′AGTCAGGCGAIACCATATGCCC3′ |

Dharmacon | N/A |

| DNA templates used in In Vitro transcription termination assay | ||

| IVT1 (Wild-type ykoY) 5′GCGTCAGCATTGATTTATATTACGAAGAATATTCGGGATTG TATTTAAAATCAAAGCGCTTTTTAGATCAAATGGAAAGCATG AAACAUCTTATGGGTGAAAACAAAAGTTGACATTTGGTCCAT CTTTTTATATGATCATTTACAAAGGGGAGTAGCGTCGGTAAG ACCGAAACAAAGTCGTCAATTCGTGAGATTCTCACCGGCTTT GTTGACATACTTATGTATGTTTAGCAAGACCTTTGCCAGTTTT GATATCTGGCAGAGGTCTTTTTTTGTAAAACCTCTCATGATAT CAGTTAGAAATAAAGGAGAATCATTATG3′ |

Eurofins Genomics | N/A |

| IVT2 (ykoYalx chimera) 5′GCGTCAGCATTGATTTATATTACGAAGAATATTCGGGATTG TATTTAAAATCAAAGCGCTTTTTAGATCAAATGGAAAGCATG AAACAUCTTATGGGTGAAAACAAAAGTTGACATTTGGTCCAT CTTTTTATATGATCATTTACAAAGGGGAGTAGCGTCGGTAAG ACCGAAACAAAGTCGTCATTACGTGAGATTCTCACCGGCTTT GTTGACATACTTATGTATGTTTAGCGAGACCTTTGCCAGTTTT GATATCTGGCAGAGGTCTTTTTTTGTAAAACCTCTCATGATAT CAGTTAGAAATAAAGGAGAATCATTATG3′ |

Eurofins Genomics | N/A |

| IVT3 (ykoYmntP chimera) 5′GCGTCAGCATTGATTTATATTACGAAGAATATTCGGGATTG TATTTAAAATCAAAGCGCTTTTTAGATCAAATGGAAAGCATG AAACAUCTTATGGGTGAAAACAAAAGTTGACATTTGGTCCAT CTTTTTATATGATCATTTACAAAGGGGAGTAGCGTCGGTAAG ACCGAAACAAAGTCGACAUACUGTGAGATTCTCACCGGCTTT GTTGACATACTTATGTATGTTTAGCGAGACCTTTGCCAGTTTT GATATCTGGCAGAGGTCTTTTTTTGTAAAACCTCTCATGATAT CAGTTAGAAATAAAGGAGAATCATTATG3′ |

Eurofins Genomics | N/A |

| IVT4 (ykoYmntP A92G U126C chimera) 5′GCGTCAGCATTGATTTATATTACGAAGAATATTCGGGATTG TATTTAAAATCAAAGCGCTTTTTAGATCAAATGGAAAGCATG AAACATCTTATGGGTGAAAACAAAAGTTGACATTTGGTCCAT CTTTTTATATGATCATTTACAAAGGGGAGTAGCGTCGGTAAG ACCGAAACAAAGTCGTCAATTCGTGAGATTCTCACCGGCTTT GTTGACATACTTATGTATGTTTAGCAGGACCTTTGCCAGTTTT GATATCTGGCAGAGGTCCTTTTTTGTAAAACCTCTCATGATAT CAGTTAGAAATAAAGGAGAATCATTATG3′ |

Eurofins Genomics | N/A |

| IVT5 (ykoYmntP G93A C125U chimera) 5′GCGTCAGCATTGATTTATATTACGAAGAATATTCGGGATTG TATTTAAAATCAAAGCGCTTTTTAGATCAAATGGAAAGCATG AAACATCTTATGGGTGAAAACAAAAGTTGACATTTGGTCCAT CTTTTTATATGATCATTTACAAAGGGGAGTAGCGTCGGTAAG ACCGAAACAAAGTCGTCAATTCGTGAGATTCTCACCGGCTTT GTTGACATACTTATGTATGTTTAGCAAAACCTTTGCCAGTTTT GATATCTGGCAGAGGTTTTTTTTTGTAAAACCTCTCATGATAT CAGTTAGAAATAAAGGAGAATCATTATG3′ |

Eurofins Genomics | N/A |

| IVT6 (ykoYmntP A94G U124C chimera) GCGTCAGCATTGATTTATATTACGAAGAATATTCGGGATTGT ATTTAAAATCAAAGCGCTTTTTAGATCAAATGGAAAGCATGA AACATCTTATGGGTGAAAACAAAAGTTGACATTTGGTCCATC TTTTTATATGATCATTTACAAAGGGGAGTAGCGTCGGTAAGA CCGAAACAAAGTCGTCAATTCGTGAGATTCTCACCGGCTTTG TTGACATACTTATGTATGTTTAGCAAGGCCTTTGCCAGTTTTG ATATCTGGCAGAGGCCTTTTTTTGTAAAACCTCTCATGATATC AGTTAGAAATAAAGGAGAATCATTATG |

Eurofins Genomics | N/A |

| Deposited Structures | ||

| Crystal Structure of L. lactis ykoY riboswitch bound to Cd2+ ion | This study | PDB:6CB3 |

| Crystal Structure of ykoYalx chimeric riboswitch bound to Cd2+ ion | This study | PDB:6CC1 |

| Crystal Structure of ykoYmntP chimeric riboswitch bound to Cd2+ ion | This study | PDB:6CC3 |

| Lactococcus lactis yybP-ykoY Mn riboswitch bound to Mn2+ | Price et al., 2015 | PDB:4Y1I |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| HKL2000 | Otwinowski and Minor, 1997 | http://www.hkl-xray.com/ |

| Phenix | Adams et al., 2010 | https://www.phenix-online.org/ |

| Coot | Emsley and Cowtan, 2004 | https://www2.mrc-lmb.cam.ac.uk/personal/pemsley/coot/ |

| Erraser | Chou et al., 2013 | https://www.phenix-online.org/documentation/reference/erraser.html |

| Rcrane | Keating and Pyle, 2010 | http://pylelab.org/form/rcrane |

In vitro transcription termination

Templates for transcription (IVT 1–3, Key Resources Table) were amplified from plasmids by PCR, purified by electrophoresis through 2% (w/v) agarose gels, and extracted using GeneJet kits (Thermo Scientific). 20 nM of linear templates were incubated in 10 μl transcription buffer [20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.0, 50 mM NaCl, 250 μM MgCl2, 100 μM TCEP and 5% (v/v) glycerol] containing 20 μM each ATP, UTP and GTP, 0.15 μCi•ml−1 α-32P-ATP, 100 μM ApC dinucleotide and 0.01 units E. Coli polymerase holoenzyme (Epicenter) at 37 °C to generate stalled transcription complexes and pre-labeled transcripts. Transition metal ions or control group II cations (Mg2+, Ca2+) to a final concentration of 100 μM, and 100 mM each ATP, UTP, CTP, GTP were then added. Reactions were terminated by mixing 1:1 with loading buffer [95% (v/v) formamide, 0.001% (w/v) xylene cyanol, 0.001% (w/v) bromophenol blue] and analyzed on 8% acrylamide (29:1 acrylamide:bisacrylamide) 8M urea polyacrylamide gels. Gels were imaged by autoradiography using a Typhoon imager (GE healthcare). Experiments with mutants (IVT 3–6, Key Resources Table) were performed as above, but with 400 μM (instead of 100 μM) MnCl2 added to the reactions.

Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC)

Prior to ITC experiments (MicroCal ITC200 calorimeter, GE Healthcare), RNAs 1–5 in ITC buffer [30 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, adjusted to pH 6.8 with NaOH] were heated to 95 °C for 2 min and placed on ice for 10 min. MgCl2 was then added to a final concentration of 5 mM, and the RNAs incubated at 21°C for 15 min. The RNAs were washed extensively in ITC buffer supplemented with 5 mM MgCl2 by centrifugal ultrafiltration, concentrated, and filtered (0.2 μm). Divalent cations were dissolved in ITC buffer and filtered. Experiments were performed with 50–200 μM RNA (cell) and 0.3–3 mM cation (syringe) at 25 °C, depending on affinity and magnitude of enthalpy. Data were corrected for heats of dilution by subtracting the enthalpies of cations titrated into ITC buffer from raw data and analyzed using a two-site random binding model using Origin (Originlab). Other binding models, such as single-site, or sequential two and three-site, were tested, and resulted in larger residuals.

Crystallization and diffraction data collection

Wild-type L. lactis ykoY aptamer domain (RNA6, Key Resources Table) in crystallization buffer (10 mM Na-Cacodylate pH 7.0, 50 mM NaCl) was heated to 95 °C for 2 min, incubated on ice for 10 min, and then held at 21 °C for 10 min (Price et al., 2015). MgCl2 was added to a concentration of 10 mM, and the RNA held at 21 °C for 15 min. CdCl2 was next added to a concentration of 5 mM and the RNA held at 21 °C for 15 min. The RNA was then concentrated by ultrafiltration to 200–250 μM. Hanging drops prepared by mixing one volume of RNA solution with two volumes of a reservoir solution comprised of 40 mM Na-Cacodylate pH 7.0, 80 mM NaCl, 20 mM BaCl2, 5 mM CdCl2, 12 mM spermine tetrahydrochloride, and 12% (v/v) 2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol (MPD) were equilibrated by vapor diffusion at 21 °C. Plate-shaped crystals grew over 5 days to maximum dimensions of 200 × 50 × 50 μm3. Crystals were transferred to reservoir solution containing 30% (v/v) MPD. Crystals of RNA6 containing Cd2+ but no Ba2+ were grown in the same manner, but using a reservoir solution comprised of 40 mM Na-Cacodylate pH 7.0, 80 mM NaCl, 10 mM CdCl2, 10 mM MgCl2, 12mM spermine tetrahydrochloride, and 12% (v/v) MPD. Plate-shaped crystals grew over 5 days at 21 °C to maximum dimensions of 200 × 50 × 50 μm3. These crystals were also cryoprotected in reservoir solution containing 30% (v/v) MPD. Crystals of L. lactis ykoY aptamer-alx chimera (RNA7, ykoYalx, Key Resources Table) were grown under the same conditions as those used for the Ba2+ and Cd2+-containing wild-type L. lactis (RNA4, Key Resources Table) crystals discussed above. These plate-shaped crystals grew over 5 days at 21 °C to maximum dimensions of 200 × 50 × 50 μm3 and were cryoprotected in reservoir solution containing 30% (v/v) MPD. Crystals of ykoY aptamer-mntP chimera (RNA8, ykoYmntP, Key Resources Table) were grown by hanging-drop vapor diffusion by mixing one volume of RNA with two volumes of a reservoir comprised of 0.1 M magnesium formate and 15% (w/v) PEG 3350. Plate-shaped crystals grew in one day at 21 °C to maximum dimensions of 100 × 20 × 20 μm3 and were cryoprotected by plunging into a solution containing 0.1 M magnesium formate, 15% (w/v) PEG 3350, and 25% (v/v) PEG 400. All crystals were mounted in nylon loops and flash-frozen by plunging into liquid nitrogen. Diffraction data were collected at 100 K at beamlines 5.0.1 and 5.0.2 of the Advanced Light Source (ALS), Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. Data were reduced using the HKL package (Otwinowski and Minor, 1997) (Table 1).

Structure determination

Analysis (Adams et al., 2010; Winn et al., 2011) of RNA6 data indicated merohedral twinning. The structure was determined by molecular replacement (McCoy et al., 2007) using the Mn2+-bound ykoY aptamer domain structure (PDB code:4Y1I) as a search model. Searches in trigonal space groups failed to produce molecular replacement solutions, but a search using data reduced in space group P1 produced a solution with 6 copies of the RNA in the asymmetric unit and a TFZ score of 14.5. A complete model with RNAs in two different conformations and with a (R factor 16.3%, free-R factor 20.5%) was produced by iterative rounds of model building and refinement (Adams et al., 2010; Emsley and Cowtan, 2004; Keating and Pyle, 2010). The two conformers were used for further molecular replacement in data reduced in space group P31, yielding a solution with a TFZ score of 35.3. Subsequent model building and refinement, including TLS parameter (Painter and Merritt, 2006) and RNA geometry (Chou et al., 2013) optimization produced the current model in space group P31 with a R factor of 14.0% and free-R factor of 17.4% using the twin law (h, −h–k, −l). This crystallographic model contains all the residues of two aptamer domain RNAs in the asymmetric, except for the 3′-terminal cytosines, which are presumed disordered, 40 Cd2+, 14 Ba2+, and 4 Mg2+ ions, and 506 water molecules (Supplementary Table 1). The structure of RNA6 in untwinned crystals that contained Cd2+ but no Ba2+ with the symmetry of space group C222 was solved by molecular replacement (McCoy et al., 2007) using the Mn2+-bound ykoY aptamer domain structure (PDB code:4Y1I) as a search model. The top solution had a TFZ score of 21.4. The RNA crystallized with two molecules in the asymmetric unit, but contained several regions that were disordered throughout the crystal. The location of Cd2+ ions in each molecule were confirmed by anomalous difference Fourier syntheses. The structure of RNA7 crystals (also twinned) was solved by molecular replacement (McCoy et al., 2007) using the RNA4 dimer as a search model, yielding a solution with a TFZ score of 32.3. L3 residues of chain A were disordered and could not be built. All residues of chain B, except the 3′-terminal cytosine were built. The current model comprises in addition 28 Cd2+, 8 Ba2+, and 1 Mg2+ ions and 83 water molecules. The structure of RNA8 crystals (which were not twinned) were solved in space group C2 using PDB ID 4Y1I as a search model. Two copies of the RNA monomer were located in the asymmetric unit with a combined TFZ score of 30.1. Both molecules contained similar conformations, except that chain B was disordered in the P4 region. Refinement was carried out as above for RNA4. The final RNA6 structure contained 12 Cd2+ ions, 16 Mg2+ ions and 46 waters. All models were subjected to multiple rounds of simulated-annealing refinement using a maximum likelihood target function during initial stages of refinement using the program Phenix (Adams et al., 2010). Manual model building for all structures were performed in Coot (Emsley and Cowtan, 2004) with the Rcrane plugin (Keating and Pyle, 2010). Final models were validated using Phenix and the PDB structure validation server. Structure figures were prepared using PyMol.

Reanalysis of the Mn2+-bound ykoY structure

The Mn2+-bound ykoY structure was re-refined (Adams et al., 2010) against deposited structure factor amplitudes (PDB ID:4Y1I) keeping the free set of Price et al. (2015). For reassessment of transition metal ion identity at sites MA and MB of both RNAs in the asymmetric unit, the imaginary component of the anomalous scattering factors (f″) corresponding to ions in these two sites was allowed to vary, while f″ was fixed to standard values at the X-ray energy reported for data collection for the rest of the heavy metal ion substructure of Price et al (2015). The real component of the anomalous scattering factors (f′) was not refined for any heavy metal ion. The occupancy of all heavy atoms was fixed to unity and their B-factors allowed to vary during substructure refinement. After reassessing the ions in the binding sites (Figure S4), the new riboswitch model was subjected to further simulated-annealing, individual isotropic B-factor and positional refinement.

Analytical size-exclusion chromatography (SEC)

SEC experiments were conducted using a Superdex 75 10/300 GL column (GE healthcare). Samples of RNA1 (Key Resources Table) were folded in SEC buffer [20mM HEPES, 150mM NaCl, adjusted to pH 7.0 with NaOH] by heated to 95 °C for 2 min, incubated on ice for 10 min, and then held at 21 °C for 10 min. Next, RNA solutions were mixed with 1 mM (Figure S12A) or 5 mM MgCl2 and incubated at 21 °C for 15 mins. Subsequently, samples were diluted with SEC buffer containing 1 mM MgCl2 and 50 μM transition metals (Figure S12A), 5 mM MgCl2 (Figure S12B control experiments), or 1mM MgCl2 and 4 mM transition metals to 20 μM final concentrations. 100 μL of 0.2 μm-filtered samples were loaded by injection and eluted in SEC buffer containing corresponding divalent ions at a flow rate of 1 ml/min and monitored at 260 nm wavelength.

Bimolecular mntP and mntP (G93I) aptamer domain experiments

Bimolecular mntP aptamer domains was prepared by annealing an in vitro transcribed RNA (RNA12, Key Resources Table) with synthetic oligonucleotides (Dharmacon, GE Healthcare) with either the wild-type (RNA13, Key Resources Table) or G93I sequence (RNA14, Key Resources Table). Transcript and oligonucleotide were mixed in ITC buffer, heated 95 °C for 2 min and placed on ice immediately for 10 min. MgCl2 was then added to a final concentration of 5 mM, and the RNAs incubated at 21°C for 15 min. Next, reactions in ITC buffer were fractionated by SEC (Superdex 75 10/300 GL, GE healthcare) to remove excess RNA. Annealed RNA fractions were pooled, concentrated, and filtered. ITC Experiments were conducted with 50 μM annealed RNA in the cell and 500 μM MnCl2 in the syringe. Thermograms were fitted as described above.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The intensities of transcripts from in vitro transcription experiments were quantified using the program ImageJ. Duplicate experiments were averaged and the standard deviation of the mean were calculated using the GraphPad Prism software. For specific datasets two-tailed Student’s t-test analysis were conducted in GraphPad Prism and data with p-values >0.05 were considered to be statistically insignificantly different. Correction and linear regression analysis of ITC thermograms were conducted using the program Origin with built-in binding models. The mean and standard deviation for Kd, ΔH and ΔS for duplicate experiments were calculated in GraphPad Prism.

DATA AND SOFTWARE AVAILABILITY

All software reported in Method Details and indicated in the Key Resources Table.

The accession codes for the coordinates and structure factors of all new structures in this paper have been deposited with the PDB as indicated in Key Resources Table.

Supplementary Material

SIGNIFICANCE.

The structural basis for selective cation binding by RNA is poorly understood. Analysis of the phylogenetically widespread yybP-ykoY riboswitches demonstrates that they can bind and be activated by various transition metal ions. The limited selectivity arises from structural plasticity of their transition metal ion-binding sites. The chemically similar Cd2+ and Mn2+ are bound most tightly, and crystallographic structure determination reveals them coordinated by seven ligands. Among transition metal ions, high-spin Cd2+ and Mn2+ are most commonly heptacoordinate, and the yybP-ykoY riboswitches exploit this to achieve selectivity. Remarkably, the bacterial transcription factor MntR, which also responds to Cd2+ and Mn2+, employs a similar heptacoordinate binding site for ion selectivity, showing that a protein and an RNA can rely on the same chemical principles for transition metal ion recognition.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Members of the large yybP-ykoY riboswitch family bind diverse transition metal ions

Cd2+ and Mn2+ are bound most tightly and with comparable affinity

The RNA achieves transition metal ion selectivity by enforcing heptacoordination

This riboswitch and the protein MntR have the same selectivity mechanism

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of beamlines 5.0.1 and 5.0.2. of the Advanced Light Source, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (ALS) for crystallographic data collection, G. Piszczek of the Biophysics Core Facility of the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) for ITC data collection and data analysis, M. Dambach and G. Storz for initiating the project and sharing unpublished data, and N. Baird, N. Demeshkina, C. Fagan, C. Jones, T. Numata, L. Skejloca, R. Trachman and J. Zhang discussions. This work was supported by the intramural program of the NHLBI, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.B and A.R.F. designed experiments; S.B conducted the experiments; S.B and A.R.F. analyzed results and prepared the manuscript.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkóczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auffinger P, Grover N, Westhof E. Metal ion binding to RNA. Metal Ions Life Sci. 2011;9:1–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrick JE, Corbino KA, Winkler WC, Nahvi A, Mandal M, Collins J, Lee M, Roth A, Sudarsan N, Jona I, et al. New RNA motifs suggest an expanded scope for riboswitches in bacterial genetic control. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:6421–6426. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308014101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brantl S. Bacterial gene regulation: metal ion sensing by proteins or RNA. Trends Biotech. 2006;24:383–386. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown NL, Lloyd JR, Jakeman K, Hobman JL, Bontidean I, Mattiasson B, Csöregi E. Heavy metal resistance genes and proteins in bacteria and their application. Biochem Soc Trans. 1998;26:662–665. doi: 10.1042/bst0260662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruins MR, Kapil S, Oehme FW. Microbial resistance to metals in the environment. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2000;45:198–207. doi: 10.1006/eesa.1999.1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanova D, Alemany P, Bofill JM, Alvarez S. Shape and symmetry of heptacoordinate transition-metal complexes: structural trends. Chemistry. 2003;9:1281–1295. doi: 10.1002/chem.200390145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrangsu P, Rensing C, Helmann JD. Metal homeostasis and resistance in bacteria. Nature Rev Microbiol. 2017;15:338–350. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Changela A, Chen K, Xue Y, Holschen J, Outten CE, O’Halloran TV, Mondragón A. Molecular basis of metal-ion selectivity and zeptomolar sensitivity by CueR. Science. 2003;301:1383–1387. doi: 10.1126/science.1085950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, Yuldasheva S, Penner-Hahn JE, O’Halloran TV. An atypical linear Cu(I)-S2 center constitutes the high-affinity metal-sensing site in the CueR metalloregulatory protein. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:12088–12089. doi: 10.1021/ja036070y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen PR, He C. Selective recognition of metal ions by metalloregulatory proteins. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2008;12:214–221. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou FC, Sripakdeevong P, Dibrov SM, Hermann T, Das R. Correcting pervasive errors in RNA crystallography through enumerative structure prediction. Nature Methods. 2013;10:74–76. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cromie MJ, Shi Y, Latifi T, Groisman EA. An RNA sensor for intracellular Mg2+ Cell. 2006;125:71–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dambach M, Sandoval M, Updegrove TB, Anantharaman V, Aravind L, Waters LS, Storz G. The ubiquitous yybP-ykoY riboswitch Is a manganese-responsive regulatory element. Mol Cell. 2015;57:1099–1109. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dann CE, Wakeman C, Sieling C, Baker S, Irnov I, Winkler W. Structure and mechanism of a metal-sensing regulatory RNA. Cell. 2007;130:878–892. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draper DE. RNA folding: thermodynamic and molecular descriptions of the roles of ions. Biophys J. 2008;95:5489–5495. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.131813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draper DE, Grilley D, Soto AM. Ions and RNA folding. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2005;34:221–243. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.34.040204.144511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferré-D’Amaré AR, Winkler WC. The roles of metal ions in regulation by riboswitches. Metal Ions Life Scii. 2011;9:141–173. doi: 10.1039/9781849732512-00141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finney LA, O’Halloran TV. Transition metal speciation in the cell: insights from the chemistry of metal ion receptors. Science. 2003;300:931–936. doi: 10.1126/science.1085049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster AW, Osman D, Robinson NJ. Metal preferences and metallation. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:28095–28103. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R114.588145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa K, Ramesh A, Zhou Z, Weinberg Z, Vallery T, Winkler WC, Breaker RR. Bacterial riboswitches cooperatively bind Ni(2+) or Co(2+) ions and control expression of heavy metal transporters. Mol Cell. 2015;57:1088–1098. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasfeld A, Guedon E, Helmann JD, Brennan RG. Structure of the manganese-bound manganese transport regulator of Bacillus subtilis. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:652–657. doi: 10.1038/nsb951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golynskiy MV, Davis TC, Helmann JD, Cohen SM. Metal-induced structural organization and stabilization of the metalloregulatory protein MntR. Biochemistry. 2005;44:3380–3389. doi: 10.1021/bi0480741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Shin JH, Pinochet-Barros A, Su TT, Helmann JD. Bacillus subtilis MntR coordinates the transcriptional regulation of manganese uptake and efflux systems. Mol Microbiol. 2017;103:253–268. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imlay JA. The mismetallation of enzymes during oxidative stress. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:28121–28128. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R114.588814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CP, Ferré-D’Amaré AR. Long-range interactions in riboswitch control of gene expression. Annu Rev Biophys. 2017;46:455–481. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-070816-034042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanazawa S, Mori K. Isolation of cadmium-resistant bacteria and their resistance mechanisms .1. Isolation of Cd-resistant bacteria from soils contaminated with heavy metals. Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 1996;42:725–730. [Google Scholar]

- Keating KS, Pyle AM. Semiautomated model building for RNA crystallography using a directed rotameric approach. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:8177–8182. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911888107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliegman JI, Griner SL, Helmann JD, Brennan RG, Glasfeld A. Structural basis for the metal-aelective activation of the manganese transport regulator of Bacillus subtilis. Biochemistry. 2006;45:3493–3505. doi: 10.1021/bi0524215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leontis NB, Westhof E. Geometric nomenclature and classification of RNA base pairs. RNA. 2001;7:499–512. doi: 10.1017/s1355838201002515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieser SA, Davis TC, Helmann JD, Cohen SM. DNA-binding and oligomerization studies of the manganese(II) metalloregulatory protein MntR from Bacillus subtilis. Biochemistry. 2003;42:12634–12642. doi: 10.1021/bi0350248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin XY, Mou RX, Cao ZY, Xu P, Wu XL, Zhu ZW, Chen MX. Characterization of cadmium-resistant bacteria and their potential for reducing accumulation of cadmium in rice grains. Sci Total Envrion. 2016;569:97–104. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.06.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Z, Jacobsen FE, Giedroc DP. Coordination chemistry of bacterial metal transport and sensing. Chem Rev. 2009;109:4644–4681. doi: 10.1021/cr900077w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy A, Grosse-Kunstleve R, Adams P, Winn M, Storoni L, Read R. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Cryst. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire AM, Cuthbert BJ, Ma Z, Grauer-Gray KD, Brunjes Brophy M, Spear KA, Soonsanga S, Kliegman JI, Griner SL, Helmann JD, et al. Roles of the A and C sites in the manganese-specific activation of MntR. Biochemistry. 2013;52:701–713. doi: 10.1021/bi301550t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer MM, Hammond MC, Salinas Y, Roth A, Sudarsan N, Breaker RR. Challenges of ligand identification for riboswitch candidates. RNA Biol. 2011;8:5–10. doi: 10.4161/rna.8.1.13865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montange RK, Batey RT. Riboswitches: emerging themes in RNA structure and function. Annual Rev Biophys. 2008;37:117–133. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.130000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nies DH. Efflux-mediated heavy metal resistance in prokaryotes. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2003;27:313–339. doi: 10.1016/S0168-6445(03)00048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nissen P, Ippolito JA, Ban N, Moore PB, Steitz TA. RNA tertiary interactions in the large ribosomal subunit: the A-minor motif. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:4899–4903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081082398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Halloran TV. Transition metals in control of gene expression. Science. 1993;261:715–725. doi: 10.1126/science.8342038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Meth Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Outten CE, O’Halloran TV. Femtomolar sensitivity of metalloregulatory proteins controlling zinc homeostasis. Science. 2001;292:2488–2492. doi: 10.1126/science.1060331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Painter J, Merritt EA. Optimal description of a protein structure in terms of multiple groups undergoing TLS motion. Acta Crystallographica Section D: Biological Crystallography. 2006;62:439–450. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906005270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer LD, Skaar EP. Transition Metals and Virulence in Bacteria. Annu Rev Genet. 2016;50:67–91. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-120215-035146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peselis A, Serganov A. Themes and variations in riboswitch structure and function. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1839:909–918. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2014.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peariso K, Huffman DL, Penner-Hahn JE, O’Halloran TV. The PcoC copper resistance protein coordinates Cu(I) via novel S-methionine interactions. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:342–343. doi: 10.1021/ja028935y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price IR, Gaballa A, Ding F, Helmann JD, Ke A. Mn2+-sensing mechanisms of yybP-ykoY orphan riboswitches. Mol Cell. 2015;57:1110–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Que EL, Bleher R, Duncan FE, Kong BY, Gleber SC, Vogt S, Chen S, Garwin SA, Bayer AR, Dravid VP, et al. Quantitative mapping of zinc fluxes in the mammalian egg reveals the origin of fertilization-induced zinc sparks. Nat Chem. 2015;7:130–139. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]