Highlights

-

•

Aggressive behavior of SCC in young patients is uncommon.

-

•

Diagnosed a year after first signs of the lesion; One previously diagnosed as an abscess, the other as necrotizing fasciitis.

-

•

These delayed diagnoses might be a contributing factor to the tumor aggressiveness.

-

•

Hence, a tissue diagnosis is necessary to rule out malignancy in chronic lesions, taking Marjolin’s ulcer into account.

Keywords: Squamous cell carcinoma, Marjolin’s ulcer, Abscess, Young patients

Abstract

Introduction

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is a common skin cancer, second in incidence only to basal cell carcinoma (BCC). The incidence of SCC increases significantly with age; thus, it is rarely diagnosed in young patients. In this paper, we present two cases of young patients who presented clinically with purulent lesions that were later diagnosed as large primary SCCs.

Materials and methods

A review of the medical records of two patients who were admitted to the department of plastic surgery with a final clinical diagnosis of cutaneous SCC was conducted. Information of the review included history, physical examination, laboratory tests, imaging studies and histology. A literature review was also conducted and discussed.

Results

Two female patients under the age of 45 presented with large, purulent lesions that were initially clinically suggestive of an infectious etiology. The lesions were surgically treated by incision and drainage without sending tissue samples to pathology. Biopsies of the lesions were performed to obtain a tissue diagnosis due to recurrence approximately one year after the initial treatment. Histological evaluation revealed well differentiated squamous cell carcinomas. Surgical intervention with wide excision with adjuvant chemotherapy was recommended based on biopsy and CT scan results.

Discussion

Aggressive behavior of SCC in young patients is uncommon. The patients in this report were diagnosed only one year after the first sign of the lesion. One patient was first diagnosed with an abscess, and the other with necrotizing fasciitis. The delayed diagnosis of SCC in these two patients is a potential contributing factor to the aggressiveness of the tumors. Therefore, it is imperative to perform skin biopsies of chronic or persistent purulent lesions to rule out malignancies including Marjolin’s ulcer.

Conclusion

Aggressive SCC should be suspected in cases of persistent and relapsing purulent lesions in all patients.

1. Introduction

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the second most common skin malignancy after basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and can present with a wide variety of clinical manifestations [1,2]. It accounts for approximately 20% of all nonmelanoma skin cancers in the United States [[1], [2], [3], [4]]. The incidence of SCC increases with age and is 5–10 times higher for those 75 years of age or older [5,6]. There are numerous environmental and genetic risk factors that contribute to the development of SCC, which include UV light, radiation, immunosuppression, chronic inflammation, smoking, HPV infection, drugs, family history, inherited disorders such as xeroderma pigmentosum and others [1,2,[7], [8], [9], [10]].

SCC is most commonly seen in fair-skinned individuals in locations that are frequently exposed to the sun [11]. A thorough and complete physical examination, including lymph nodes, is necessary to detect potential lesions, and the final diagnosis is made by histopathologic analysis of skin biopsy specimens [1,11,12]. Treatment of SCC involves surgical excision, with radiation and systemic therapy in case of a regional or metastatic disease. The patient specific treatment plan is based on a risk assessment for local recurrence and metastasis [[13], [14], [15], [16]]. Regional lymph node involvement and metastases are rare and associated with increased mortality [[17], [18], [19], [20], [21]]. Although the five-year cure rate is greater than 90%, all patients require long term oncologic follow up even after successful treatment.

Marjolin’s ulcer refers to a rare but highly aggressive ulcerating SCC, which presents as a non-healing wound or painless ulcer [22]. It is associated with chronic inflammatory states, such as venous ulcers, lupus vulgaris, vaccination scars, snake bite scars, pressure sores, osteomyelitis zones and radiotherapy areas. The majority of purulent Marjolin’s ulcer lesions described in the literature are pilonidal abscesses [11,[22], [23], [24]].

Here we discuss two cases of rare Marjolin’s ulcer in northern Israel.

2. Case reports

2.1. Case 1

A thirty-two-year-old female presenting with a left-sided gluteal abscess was hospitalized in the general surgery department. Her medical history included spina bifida (meningocele) with resultant paraplegia and urinary retention requiring self-catheterization. During the hospitalization, she underwent debridement of the involved gluteal skin and received intravenous antibiotics. However, a biopsy of the affected gluteal tissue was not taken, hence a histopathologic analysis was not performed. The patient was offered a diverting colostomy to keep the abscessed area clean to facilitate healing, however, this intervention was declined. On the second post-operative day, the patient became septic despite receiving intravenous antibiotics. A subsequent CT scan revealed multiple abscesses, which were then incised and drained in the operating room. The patient was discharged following an uneventful postoperative course.

Eight months later, the patient was admitted to our hospital and diagnosed with necrotizing fasciitis in the same left-sided gluteal region. She refused any definitive surgical treatment but agreed to a biopsy, which revealed a well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (see Fig. 1). An initial CT scan showed multiple burrows and enlarged lymph nodes (see Fig. 2a–c). Additional CT scans of the thorax and abdomen demonstrated no evidence of distant metastases. Repeat biopsies of the lesion were performed, and the diagnosis of a well differentiated squamous cell carcinoma was confirmed (see Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

The gluteal area showing extensive tumor formation with ulcerative surface.

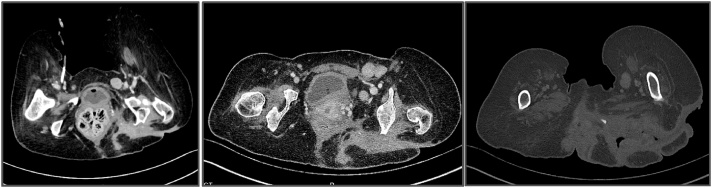

Fig. 2.

a–c: CT scan showed multiple burrows and enlarged lymph nodes.

Fig. 3.

Histological biopsies confirmed the diagnosis of a well differentiated squamous cell carcinoma.

A multidisciplinary team including plastic surgeons, orthopedic oncologic surgeons, general surgeons and medical oncologists advised her to undergo extensive surgical intervention including hemipelvectomy, abdominoperineal resection (APR) and colostomy. The patient refused any surgical intervention. She was then referred for chemotherapy and began treatment with a regimen of cis-platinum, 5-fluorouracil (5FU), and Erbitux (cetuximab). This chemotherapy was unsuccessful, and the patient passed away within a few months. The extensive spread and aggressive behavior of the lesion was highly suspicious for Marjolin’s ulcer arising from a chronic pressure sore.

2.2. Case 2

A forty-two-year-old female with a history of morbid obesity and hypertension, status post bariatric surgery (laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding and sleeve gastrectomy) resulting in a significant weight loss, presented in July 2016 with what was initially diagnosed as an infected epidermal inclusion cyst in the axilla. The patient’s family history was significant for breast cancer and melanoma. She was initially treated at an outpatient clinic by a general surgeon who performed an incision and drainage.

One year later, the lesion reappeared, and the clinical signs were highly suspicious for malignancy (see Fig. 4). A biopsy of the lesion was performed, and the histopathologic results confirmed our suspicion of a well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. A subsequent CT scan revealed focal calcification within the large primary lesion and an additional axillary mass (3.9 cm) with a necrotic lymph node; there was no additional lymphadenopathy (see Fig. 5 a and b). Four other cysts (7.2 cm) in the anterior thorax wall were also observed.

Fig. 4.

Left axillary area showing an extensive SCC tumor with ulceration.

Fig. 5.

a and b: The CT scan revealed focal calcification within the large lesion, an additional axillary mass (3.9 cm) with a necrotic lymph node and no additional lymphadenopathy. Four other cysts (7.2 cm) in the anterior thorax wall were also observed.

The patient underwent a wide excision of the lesions under general anesthesia. The histological results showed moderately differentiated SCC with involved margins (see Fig. 6). Soon after receiving these results, the patient underwent a second surgery, which included a wide excision and additional dissection of nine lymph nodes. The pathology results showed SCC with free margins and lymph nodes without metastasis. The patient is currently being monitored regularly at our clinic and has been referred to oncology for radiation treatment.

Fig. 6.

The histological results showed moderately differentiated SCC with involved margins.

3. Discussion

SCC is a common cutaneous malignancy that is rarely aggressive unlike the presentations in these two cases. One explanation of the aggressive nature of the SCC in our cases might be related to their delayed diagnoses. In addition, the presentation of Marjolin’s ulcer in unusually young patients may further explain the tumors’ aggressive behavior. Although it is very uncommon for this aggressive tumor to appear at an early age [[1], [2], [3], [4]], our cases demonstrate the importance of having a wide differential diagnosis and high level of suspicion for malignancy when treating a chronic wound. The probable chronic irritation and inflammation, combined with the toxin and co-carcinogen theories, may shed light on the evolution of these rapidly evolving ulcerated carcinomas [11,24].

There is a paucity of literature describing Marjolin's ulcer cases in the setting of pressure sores of spina bifida patients or epidermal inclusion cysts [11,20,24,25]. Hence, the natural history of the ulcerated tumors presented in these two cases remains a mystery. However, the aggressive nature of this disease emphasizes the need for early tissue biopsy of purulent lesions that present in the setting of chronic or non-healing wounds.

There are numerous Treatment options for low risk SCC tumors [26,27] including surgical excision, cryotherapy, electrosurgery, topical treatment, radiation and photodynamic therapy. The risk of recurrence and metastasis is important for determining the appropriate treatment [[13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23]]. Marjolin’s ulcer falls into the category of high risk tumors. In these cases, surgery is still the cornerstone of treatment with adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation if necessary. Although the prognosis is excellent for low risk tumors, high risk lesions are associated with increased mortality and require lifelong monitoring, such as the two cases presented here [[17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24]].

The work presented in this paper meets the PROCESS criteria [28].

4. Conclusion

These two cases of highly aggressive SCC in relatively young patients demonstrate the importance of having an increased suspicion of malignancy when evaluating non-healing wounds with or without infection, even in non-sun-exposed locations. Thus, we recommend having a low threshold to perform biopsies in this setting in order to ensure the correct diagnosis is made to facilitate early intervention.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval has been exempted by our institution.

Funding

None.

Conflict of interest statement

None.

Guarantor

Dr. Yeela.

Consent

For one patient, we have written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

For the other patient we could not get signed consent, so head of the medical team-hospital takes responsibility that exhaustive attempts have been made to contact the family and that the paper has been sufficiently anonymised not to cause harm to the patient or their family.- uploaded sign document.

Author contribution

Dr. Yeela – study concept or design, data collection, data analysis or interpretation, writing the paper.

Research registration number

researchregistry3876.

References

- 1.2018. Epidemiology and Risk Factors for Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma.http://www.uptodate.com [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Cancer Society . 2003. Cancer Facts and Figures.www.cancer.org/docroot/STT/stt_0_2003.asp?sitearea=STT&level=1 (Accessed on 01 April 2004) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller D.L., Weinstock M.A. Nonmelanoma skin cancer in the United States: incidence. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1994;30:774. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(08)81509-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alam M., Ratner D. Cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001;344:975. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103293441306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karagas M.R., Greenberg E.R., Spencer S.K. Increase in incidence rates of basal cell and squamous cell skin cancer in New Hampshire, USA. New Hampshire Skin Cancer Study Group. Int. J. Cancer. 1999;81:555. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990517)81:4<555::aid-ijc9>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gray D.T., Suman V.J., Su W.P. Trends in the population-based incidence of squamous cell carcinoma of the skin first diagnosed between 1984 and 1992. Arch. Dermatol. 1997;133:735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brash D.E., Rudolph J.A., Simon J.A. A role for sunlight in skin cancer: UV-induced p53 mutations in squamous cell carcinoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1991;88:10124. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.22.10124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsai K.Y., Tsao H. The genetics of skin cancer. Am. J. Med. Genet. C Semin. Med. Genet. 2004;131C:82. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vitaliano P.P., Urbach F. The relative importance of risk factors in nonmelanoma carcinoma. Arch. Dermatol. 1980;116:454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gallagher R.P., Hill G.B., Bajdik C.D. Sunlight exposure, pigmentation factors, and risk of nonmelanocytic skin cancer. II. Squamous cell carcinoma. Arch. Dermatol. 1995;131:164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.2018. Clinical Features and Diagnosis of Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC)http://www.uptodate.com [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amid M.B., editor. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. Springer; New York: 2017. Part II head and neck. p. 53. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ad Hoc Task Force, Connolly S.M., Baker D.R. AAD/ACMS/ASDSA/ASMS 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery: a report of the American academy of dermatology, american college of mohs surgery, american society for dermatologic surgery association, and the american society for mohs surgery. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2012;67:531. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lansbury L., Bath-Hextall F., Perkins W. Interventions for non-metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the skin: systematic review and pooled analysis of observational studies. BMJ. 2013;347:f6153. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f6153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lansbury L., Leonardi-Bee J., Perkins W. Interventions for non-metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007869.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brodland D.G., Zitelli J.A. Surgical margins for excision of primary cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1992;27:241. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(92)70178-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rowe D.E., Carroll R.J., Day C.L., Jr. Prognostic factors for local recurrence, metastasis, and survival rates in squamous cell carcinoma of the skin, ear, and lip. Implications for treatment modality selection. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1992;26:976. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(92)70144-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kwa R.E., Campana K., Moy R.L. Biology of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1992;26:1. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(92)70001-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kraus D.H., Carew J.F., Harrison L.B. Regional lymph node metastasis from cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 1998;124:582. doi: 10.1001/archotol.124.5.582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Michalopoulos N., Sapalidis K., Laskou S., Triantafyllou E., Raptou G., Kesisoglou I. Squamous cell carcinoma arising from chronic sacrococcygeal pilonidal disease: a case report. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2017;15(1):65. doi: 10.1186/s12957-017-1129-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.2018. Treatment and Prognosis of Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma.http://www.uptodate.com [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kerr-Valentic M.A., Samimi K., Rohlen B.H., Agarwal J.P., Rockwell W.B. Marjolin’s ulcer: modern analysis of an ancient problem. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2009;123:184–191. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181904d86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fairbairn N.G., Hamilton S.A. Management of Marjolin’s ulcer in a chronic pressure sore secondary to paraplegia: a radical surgical solution. Int. Wound J. 2011;8(5):533–536. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-481X.2011.00831.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nthumba P.M. Marjolin’s ulcers: theories, prognostic factors and their peculiarities in spina bifida patients. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2010;8:108–110. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-8-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Terada Tadashi. Squamous cell carcinoma originated from an epidermal cyst. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2012;5(5):479–481. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.2018. NCCN Guidelines™ and Clinical Resources.http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nmsc.pdf (Accessed on 22 June 2013) [Google Scholar]

- 27.Farasat S., Yu S.S., Neel V.A. A new American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: creation and rationale for inclusion of tumor (T) characteristics. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2011;64:1051. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Rammohan S., Barai I., Orgill D.P., PROCESS Group The PROCESSStatement: preferred reporting of case series in surgery. Int. J. Surg. 2016;36(Pt A):319–323. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]