Abstract

The relation between traumatic brain injury (TBI) and memory dysfunction is well established, yet imprecise. Here, we investigate whether mild TBI causes a specific deficit in spatial episodic memory. Fifty-eight (29 TBI, 29 sham) mice were run in a spatial recognition task. To determine which phase of memory might be affected in our task, we assessed rodent performance at three different delay times (3 min, 1 h, and 24 h). We found that sham and TBI mice performed equally well at 3 min, but TBI mice had significantly impaired spatial recognition memory after a delay time of 1 h. Neither sham nor injured mice remembered the test object locations after a 24-h delay. In addition, the TBI-specific impairment was accompanied by a decrease in exploratory behavior during the first 3 mins of the initial exposure to the test objects. These memory and exploratory behavioral deficits were linked as branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) dietary therapy restored both memory performance and normal exploratory behavior. Our findings 1) support the use of BCAA therapy as a potential treatment for mild TBI and 2) suggest that poor memory performance post-TBI is associated with a deficit in exploratory behavior that is likely to underlie the encoding needed for memory formation.

Keywords: : BCAA therapy, spatial memory, traumatic brain injury

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) affects more than 2.5 million people every year in the United States.1 The majority of these injuries are mild TBI,2 which is defined as loss of consciousness and/or confusion and disorientation for less than 30 min or post-traumatic amnesia for less than 24 h.3 Memory deficits are a common complaint among TBI survivors,4 but it is currently unknown which aspect of memory is affected by mild TBI.5

Memory can be divided into broad categories, including working memory,6 semantic memory,7 and episodic memory,8 which can be further divided into subtypes, including recollection,9 familiarity,10 object memory,11 source memory,12 and many others. Although the precise boundaries of these categorizations are often hotly debated,13 subdividing memory into smaller subcategories has proven pivotal to identifying the neuroanatomical basis of different types of memory.14–16 Independent of category, memory is composed of three fundamental phases: encoding, maintenance, and retrieval.8 Thus, the term memory is a very general concept and is perhaps better thought of as general class of cognition, the specific implementation of which will depend on the category (semantic, episodic, working, etc.), and phase (encoding, maintenance, or retrieval) that is activated. Importantly, different implementations of memory involve different brain regions and neural computations. In order to treat the memory deficits caused by TBI, it is thus imperative to identify the specific categories and phases of memory that are impaired.

Previous work has begun to identify particular aspects of memory affected by TBI. Several studies have used the T-maze test,17–19 which measures working memory and depends on interaction between the hippocampus and medial pre-frontal cortex.20 For example, moderate injury produced no memory deficits during T-maze performance when the delay time between sample and choice phase lasted up to 15 sec.17–19 However, when the delay-time interval was increased, injured mice made more errors compared to their sham counterparts.18,19,21 Other work in mild TBI is less straightforward to interpret; for instance, using the Morris water maze, a test of spatial memory, Hylin and colleagues22 demonstrated that spatial memory is affected. However, the delay times used in that study were very short, and it is unclear whether these tasks were testing working memory (short delay) or episodic memory (longer delay), which engage completely different neural circuits.14,23

Here, our aim was to examine spatial episodic memory in a rodent model of mild lateral fluid percussion injury (LFPI) and assess memory performance as a function of time since training after 1 week post-injury. We sought to determine whether mild TBI causes a specific problem with spatial episodic memory and also to establish which phase of spatial episodic memory might be affected. Further, we tested whether BCAA (branched-chain amino acid) therapy was able to improve memory function post-TBI. BCAA therapy has been shown to restore the balance between excitation and inhibition in the hippocampus and improve contextual fear conditioning, indicating that it may improve memory after brain injury.24,25 BCAA therapy was further shown to rescue electroencephalogram rhythms associated with normal wakefulness post-TBI.26 Here, we tested the ability of BCAA therapy to mitigate specific spatial memory deficits.

Methods

Animals

Experiments were performed on 77 (29 TBI, 29 sham, 11 TBI + BCAA, and 8 sham + BCAA) 5- to 7-week-old (20–25 g) male C57BL/6J mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME). All mice were maintained on a 12-h/12-h light-dark cycle, with light on at 7:00 am, and all experiments were performed during the dark cycle. Mice had access ad libitum to food and water. All experimental procedures and protocols for animal studies were approved by the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee in accord with the international guidelines on the ethical use of animals (see Johnson and colleagues27; National Research Council, National Academy Press, Washington, DC, 1996). Experiments were designed to minimize the number of mice required.

Lateral fluid percussion injury

On day 1, all mice were anesthetized with ketamine (10 mg/100 g body weight; JHP Pharmaceuticals, Parsippany, NJ) and xylazine (1 mg/100 g body weight; Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Phoenix, AZ) mixture and placed in a mouse stereotactic frame (Stoelting Co., Wood Dale, IL). The scalp was incised and reflected. The following was conducted under × 0.7–3.5 magnifications. A craniotomy was performed using a 3-mm trephine over the right parietal area between bregma and lambda, just medial to the sagittal suture and lateral to the lateral cranial ridge. The dura remained intact throughout the craniotomy procedure. A Luer Lock needle hub (3-mm inner diameter) was secured above the skull over the opening with Loctite adhesive and subsequently with cyanoacrylate plus dental acrylic. The Luer Lock needle hub was filled with isotonic sterile saline, and the hub was capped. Mice were then placed on a heating pad until spontaneously mobile and returned to the home cage. On day 2, mice were briefly placed under isoflurane anesthesia; the hub was filled with saline and connected by high-pressure tubing to the LFPI device (Department of Biomedical Engineering, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA). Injury was induced by a brief pulse of saline onto the intact dura, which delivers a pressure of 1.5 atmospheres, generating a mild brain injury. Immediately post-injury, mice were reanesthetized with isoflurane for hub removal from the skull and scalp closure. Mice were warmed with an electric heating pad until they could move freely, before they were returned to their cages and fed with regular diet and tap water. Sham mice received all of the above procedures except the fluid pulse. Each mouse was allowed 6 days to recover before performing the behavioral task.

Object spatial-location recognition task

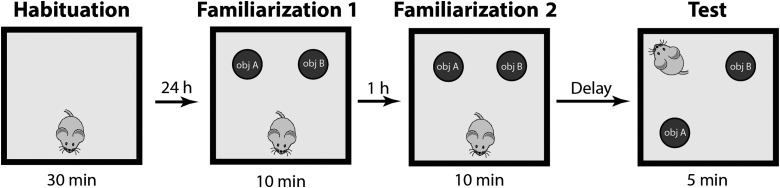

All mice were handled for 5 min each day for the duration of the experiment. Mice were tested on a memory task that assesses hippocampal-dependent memory for the locations of the objects.28 As schematically shown in Figure 1, after a period of 6 days from injury/sham procedure, mice were habituated to a square testing apparatus (30 × 30 cm) with visual cues present on the walls and no other objects in the environment for a 30-min period (habituation phase, H).29 Items in the recording room were maintained constant across the experiment and served as distal cues. Each behavioral experiment consisted of two different phases—familiarization (F) and test (T) with rest between them. Specifically, the familiarization phase was split into two subphases: familiarization 1 (F1) and familiarization 2 (F2). During F1, mice were allowed to explore the environment for a 10-min period with two identical novel objects located in two different quadrants of the apparatus. After F1, mice rested for 1 h before F2 began. During F2, mice were re-exposed to the identical apparatus setting (the same novel objects in the same location) for another 10 min. The next part of the experiment after familiarization was the test phase (T). Before the test phase (T), objects were removed and replaced with another pair. This new pair was indistinguishable from the first pair. In other words, the objects were physically different, but morphologically identical. One object was left in the previous location, and the other object was placed in a previously empty quadrant. The test phase lasted 5 min, during which time mice explored the new apparatus setting. The test phase tested the ability to identify the new location in the already well-known environment. We restricted our analysis to the first 3 min of the test phase to avoid the habituation phase.30

FIG. 1.

Behavioral task. The spatial object recognition task consists of three different phases interlaid by resting time. In the first phase (Habituation), animals explored an empty apparatus. In the second phase (Familiarization) animals were exposed to two identical objects (filled circles) with 1-h interphase rest. In the third phase (Test), one object was displayed to a previous empty quadrant and the animal entered the field from a different starting point. Between familiarization 2 and test, the delay interval was randomly chosen between 3 min, 1 h, and 24 h. Each animal performed the task with one delay time.

One goal of this experiment was to explore how memory performance changes across time. To accomplish this, we varied the time between familiarization (F) and test (T). Specifically, we used three different delay times between familiarization (F) and test (T): 3 min (sham 10, TBI 10), 1 h (sham 10, TBI 10), and 24 h (sham 9, TBI 9). Mice were randomly assigned to each of these groups. All analyses were made with experimenters blinded to both experimental conditions: 1) injury versus sham and 2) the delay time between familiarization and test.

Treatment

In order to test the efficacy of our BCAA therapy on memory task performance, an additional group of mice (11 TBI, 8 sham) were treated with BCAA dietary therapy. Specifically, drinking water was supplemented with 100 mM of leucine, isoleucine, and valine amino acids and consumed ad libitum. Mice started the treatment 48 h after injury and continued until the test phase of the task. The rationale for initiating treatment after 48 h was that previous evidence has demonstrated that it was effective.24,25 As described above, mice were allowed to recover for 6 days, and then behavior testing was performed with a 1-h delay between familiarization and test.

Statistical analysis

Data collection and analysis were performed blinded to the experimental group. Statistical analyses were performed using custom software written in Matlab (The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA).

We quantified exploratory behavior as the time the mouse spent with its nose directed toward any object within a distance of <2 cm. Of note, other behaviors, such as sitting on top of the object and looking around while sitting or resting against the object, were not considered exploratory behavior.29 Any mouse with less than 15 sec of exploratory behavior during familiarization, or with less than 10 sec of exploratory behavior during the test, was excluded from all analyses and not included in this article. Novelty preference was quantified with the discrimination index (DI), which was defined as the absolute difference in time spent exploring the novel and the familiar object divided by the total time spent exploring both objects. A preference score of 1 indicated that mice explored only the object in the new location, a score of 0 denoted no preference or equal time exploring the object in the new and old location, and a score of −1 indicated that mice explored only the object in the familiar location.

We found the DI for each mouse during the three testing intervals: 3 min, 1 h, and 24 h. In addition, we also calculated the percentage of time during F1, F2, and T that each mouse spent in exploratory behavior (EB). We also calculated the EB values across time during F1 and F2. Specifically, we segmented the F1/F2 into 90-sec sliding windows with 15-sec increments (80% overlap). We found the percentage of time in EB in each time window, and compared these values across time for sham and TBI. We also ran an identical analysis with 200-sec, nonoverlapping windows during F1/F2.

For the statistical approach, we used an unpaired t-test to compare TBI and sham DI values for all time delays between the familiarization and the test phase. For the unpaired t-test, the null hypothesis is that the TBI and sham DI values are drawn from the same distribution with identical mean and standard deviation (SD). In general, we used unpaired t-tests when comparing DI or EB values between TBI and sham groups because the number and SD of the DI/EB values in TBI and sham conditions were not identical. We also used paired t-tests when determining whether a within-group, single distribution of DI values (TBI or sham) showed any location preference. We performed this test because the expected value of DI is zero under the null hypothesis that the animal is unable to discriminate new and old spatial locations (chance performance). Thus, two-tailed, paired t-tests were used to compare within-group distributions of DI against the chance value of zero (Figs. 2, 3, and 4B), similar to the approach used by others in the field.46 Finally, we also used a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to investigate whether there was an effect of experimental conditions as well as time on EB values (Figs. 3 and 4A). The ANOVA allowed us to test both the main effects of time and experimental condition on EB values, as well as the interaction of these two factors. Of note, post-hoc t-tests were done to compare the effects across conditions, and a significance value of 0.05 was used. Again, post-hoc unpaired t-tests were used to compare across sham and TBI conditions for both EB and DI values, and paired t-tests were used to compare with group DI values against a chance value of zero.

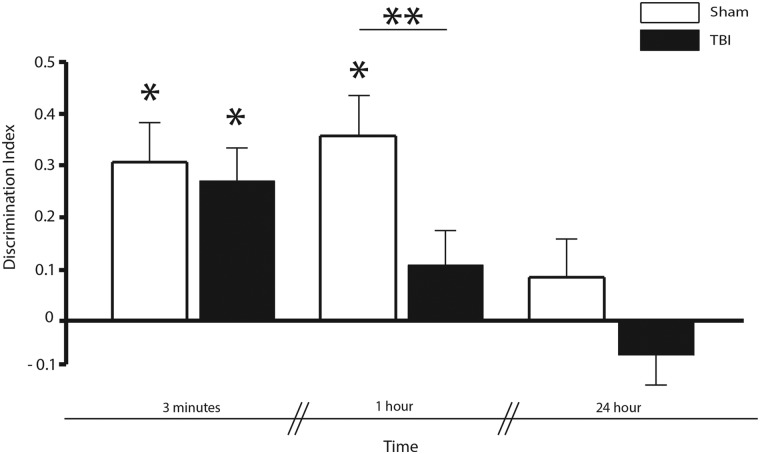

FIG. 2.

Memory retrieval: Novelty preference during test phase. Novelty preference was assessed in sham and TBI condition during the test performance after 3 min, 1 h, and 24 h. There was no difference in performance between TBI and sham animals when discrimination was tested after 3-min delay. However, after 1 h, mice in the TBI condition had a decrease in performance compared to sham mice (**p < 0.05). Both conditions were not able to discriminate after 24 h. DI different from zero in sham and TBI after 3-min delay and in sham after 1-h delay (*p < 0.05). Bars shows mean and error bars show SEM. DI, discrimination index; SEM, standard error of the mean; TBI, traumatic brain injury.

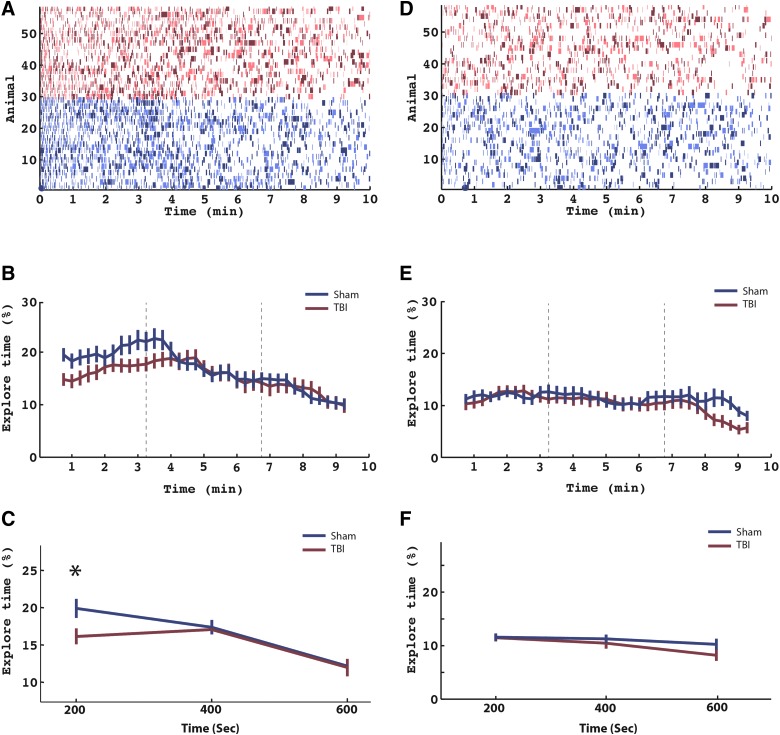

FIG. 3.

Memory encoding: exploration time during first and second familiarization. (A) Entire behavioral data for all mice (TBI and sham) during encoding (familiarization 1). Each row represents an animal (red, TBI, N = 29; blue, sham, N = 29). Colored lines in each row represent time windows in which the mouse was interacting with the objects (see Methods). Light colors and dark colors represent one of object 1 and object 2, respectively. (B) Data in (A) were segmented into thirty-four 90-sec time windows incremented by 15-sec intervals (80% overlap). The percentage of time spent interacting (percent interaction) with the objects was recorded for each animal for each time window. The percentage interaction was then averaged across animals separately for TBI (red line) and sham (blue line) animals. Error bars represent SEM. (C) To statistically analyze the data, we simplified the time periods in to three nonoverlapping windows of 200-sec duration. Percent interaction was calculated in each time window for all animals, and a two-way ANOVA was performed with time and condition as factors. There was a main effect across time (p < 0.001) and an interaction effect between time and condition (p < 0.05) that was driven by an increase in exploration time for sham mice in the first time window (asterisk plot, on post-hoc t-test, T(56) = −2.25; p < 0.03). Error bars represent SEM. (D–F) These panels follow the same format as (A), (B), and (C), but refer to the second familiarization. ANOVA, analysis of variance; SEM, standard error of the mean; TBI, traumatic brain injury. Color image is available online at www.liebertpub.com/neu

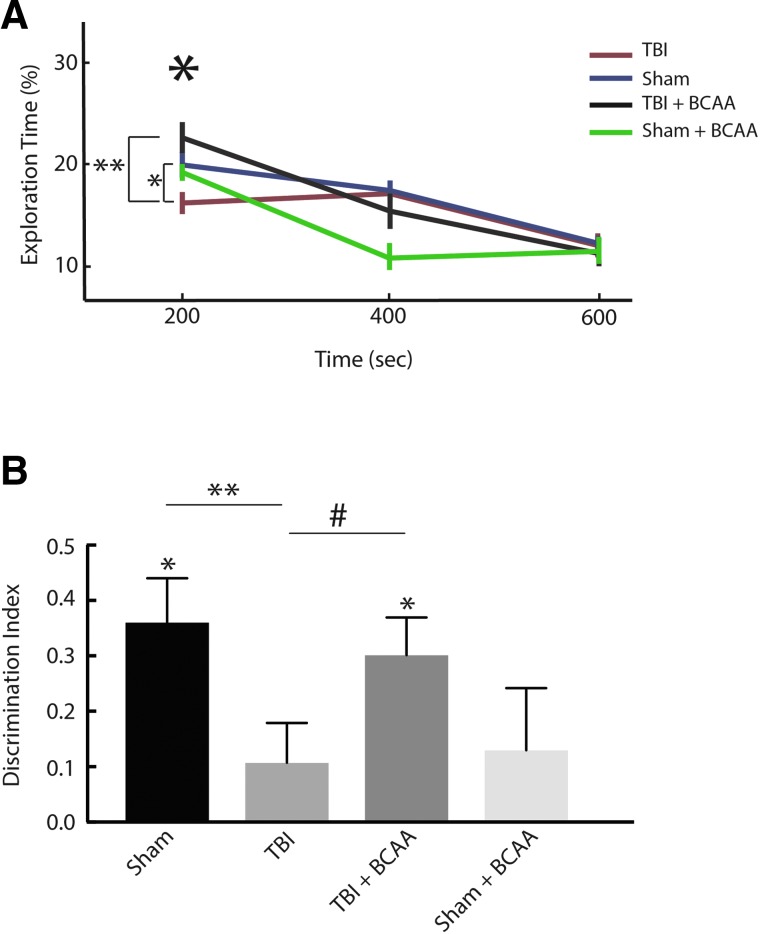

FIG. 4.

Effect of BCAA therapy on memory encoding and retrieval. (A) Analysis of Figure 3C was repeated to include a cohort of animals that were fed with a BCAA-rich diet starting 48 h after injury or sham condition. From the figure, TBI-BCAA mice experience a high rate of object exploration during the encoding period of the task compared to the untreated TBI. (**p < 0.01). (B) Novelty preference assessed during test phase in sham (n = 10), TBI (n = 10), TBI + BCAA (n = 11), sham + BCAA (n = 8) after 1-h delay between the second familiarization and test. TBI-BCAA mice showed an improvement in the task performance (**p < 0.05; #p = 0.06) and a significant ability to discriminate (*DI different than 0, p < 0.05). Bars show mean and error bars show SEM. BCAA, branched-chain amino acid; SEM, standard error of the mean; TBI, traumatic brain injury. Color image is available online at www.liebertpub.com/neu

Results

To determine whether a particular phase of spatial episodic memory (encoding, maintenance, or retrieval) was disproportionately impaired after mild TBI, we ran 58 mice in a spatial episodic memory task, half of which were subjected to a mild TBI using an LFPI model (see Methods). Specifically, we compared the TBI versus sham DI (see Methods) for all time delays between F and T (Fig. 2). We found that both sham and injured mice had a significant preference for the novel location when tested 3 min after F2 (i.e., the DI was significantly different from zero; T(9) = 3.10, p < 0.05 for sham; T(9) = 4.89, p < 0.05 for TBI). However, only sham showed a significant preference for the novel location after a 1-h delay (T(9) = 4.53; p < 0.05); further, the difference in DI between TBI and sham at the 1-h delay time was significant (T(18) = 2.36; p < 0.05). Neither TBI nor sham had a DI significantly greater than zero at the 24-h time delay (p > 0.2). These comparisons are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Exploratory Behavior (EB) and Discrimination Index (DI) in the Spatial Object Recognition Task

| Sham | TBI | Sham | TBI | Sham | TBI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 9 |

| Familiarization | ||||||

| F1 | ||||||

| EB(s) | Sham: 93.7 (3.4) TBI: 86.0 (3.3) | |||||

| DI | Sham: 0.004 (0.003) TBI: 0.01 (0.03) | |||||

| F2 | ||||||

| EB(s) | Sham: 62.8 (3.1) TBI: 57.5 (3.3) | |||||

| DI | Sham: 0.03 (0.03) TBI: −0.01 (0.03) | |||||

| Test | ||||||

| 3 min | ||||||

| EB(s) | 27.5 (2.3) | 24.1 (2.2) | ||||

| DI | 0.31 (0.09) | 0.27 (0.08) | ||||

| 1 h | ||||||

| EB(s) | 19.7 (2.9) | 19.7 (1.8) | ||||

| DI | 0.36 (0.07) | 0.11 (0.07) | ||||

| 24 h | ||||||

| EB(s) | 20.9 (3.0) | 23.1 (3.7) | ||||

| DI | 0.08 (0.02) | −0.15 (0.07) | ||||

Illustrated for each group is the mean (+SEM).

s, seconds; TBI, traumatic brain injury.

We next measured the time spent in EB during F1. Of note, when analyzing the F1 period, we combined mice from all test delay groups (58 mice, 29 TBI and 29 sham). We first compared the time spent in EB during F1 for both TBI and sham, and we found that there was no difference in total EB between TBI and sham across the entire 10-min F1 interval (p > 0.2) nor was one object preferred over the other (p > 0.2; the “novel” location for F1 was arbitrarily chosen as the location that was subsequently changed). Table 1 summarizes these comparisons and shows that there is no difference in EB or DI, when averaged across the entire 10-min F1 and F2 intervals, for TBI and sham mice.

We next analyzed EB as a function of time during F1. Figure 3A represents the entire behavioral data for all mice during F1: Each row represents a mouse, and each color represents a discrete episode of EB during F1. Figure 3B collapses this information separately across TBI and sham—by averaging, across mice, the percentage of time spent in EB for a series of 90-sec time epochs centered about the indicated times. As shown in Figure 3B, sham mice spent a disproportionate time in EB very early in F1. To test this, we constructed two-factor ANOVA assessing the EB across both injury condition and time during F1. For this analysis, we defined three time windows during F1: early (0.0–3.3 min), middle (3.4–6.6 min), and late (6.7–10.0 min). We found a significant main effect across time (F(2,198) = 26.32; p < 0.001) and an interaction effect between time and injury condition time (F(4,198) = 2.59; p < 0.05). Post-hoc t-test revealed that the interaction effect was driven by a decreased EB in TBI during the first time window in the F1 time epochs (T(56) = −2.25; p < 0.03) than sham mice.

We also examined the F2 time period to determine whether the increase in EB observed during F1 is also observed during F2. Figure 3D–F shows the same analyses repeated for F2. Of note, the increase in EB observed during the first part of F1 is not observed during F2. More specifically, the same ANOVA applied to the F2 time interval did not show a main effect across time, injury condition, or an interaction effect.

Next, we provided BCAA therapy to a subset of the TBI and sham mice. We put a separate group of TBI (n = 11) and sham (n = 8) on a diet enriched with BCAAs (100 mM each of leucine, isoleucine, and valine) in ad libitum drinking water beginning at 48 h post-injury and continuing through the test day. Mice were tested after a 1-h delay between the second familiarization and test. In Figure 4A, a two-way ANOVA shows a main effect across time (p < 0.001) and an interaction effect between time and TBI versus sham versus BCAA condition (p < 0.05). Post-hoc t-tests showed that these results were driven by a recovery of exploration in the TBI group after therapy (TBI vs. TBI + BCAA post-hoc t-test; p < 0.01). Of note, the sham and TBI data in Figure 4A are the same as that in Figure 3. In Figure 4B, we found that BCAA therapy improved animal performance during the test phase of task, that is, TBI-BCAA mice had a significant preference for the novel location (DI during test = 0.3; paired t-test; T(10) = 4.42; p < 0.05). Of note, the sham and TBI data in Figure 4B are the same as that in Figure 2. Also, there was a trend for greater DI of the treated TBI mice compared to the untreated TBI mice (unpaired t-test, p = 0.06). Further, BCAA mice also had a specific increase in EB during the first 3 min of F1 compared to TBI mice (unpaired t-test, T(38) = −3.22; p < 0.05). In contrast, sham-BCAA mice showed a decreased ability to discriminate spatial location after 1-h delay (Fig. 4B).

Discussion

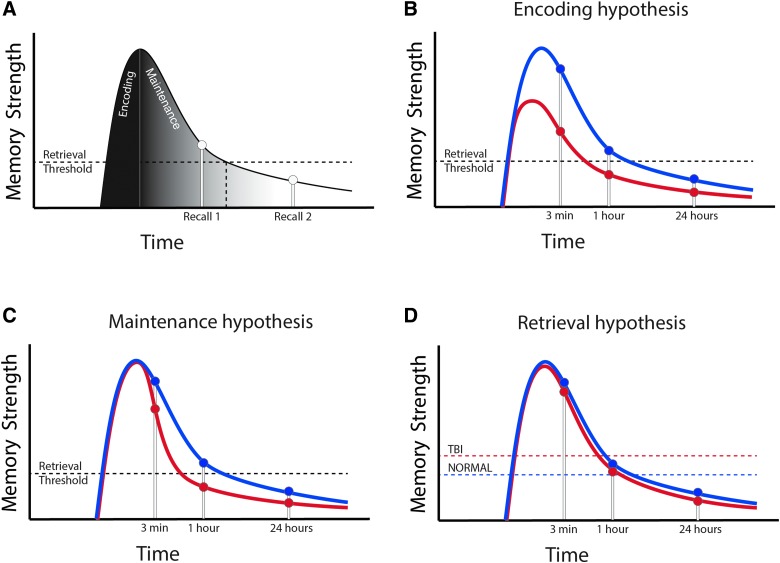

In this article, the object spatial-location recognition task (specifically, the DI metric) was designed to quantify the integrity of the spatial episodic memory system. In other words, a deficit of spatial episodic memory should cause a change in DI. We found that both TBI and sham mice successfully retrieved object location information after a 3-min delay; however, TBI mice showed a faster memory decay than sham mice. Specifically, injured mice “forgot” object location after 1 h, whereas sham mice “forgot” objection location after 24 h (Fig. 2). This result suggests that injured mice have a deficit in spatial (episodic) memory. Given that memory is composed of encoding, maintenance, and retrieval,31 there are three independent mechanisms that could result in a decrease in spatial episodic memory, which are outlined in the model represented in Figure 5 and discussed below.

FIG. 5.

Memory model to explain memory deficits after TBI. (A) Behavioral results can be understood in terms of strength model of memory. In this case, there are three hypotheses that could explain the data: (B) a deficit of encoding; (C) a deficit of maintenance; and (D) a deficit of retrieval. Data presented are most consistent with a deficit of encoding. See Discussion for details. TBI, traumatic brain injury. Color image is available online at www.liebertpub.com/neu

In Figure 5A, we briefly outline a strength theory view of episodic memory. Strength theory is a simple and well-accepted model of human episodic memory (in particular, recognition memory)32 and is based on the premise that each item can be scored on a numerical scale (for the purpose of theoretical and experimental consideration) to represent how well the item triggers a memory response.33 In Figure 5A, one item's strength is shown across time. With regard to the current task, an item represents the combined information about one object (spatial location, object information, and current context). During encoding, the memory strength for that object increases rapidly while the mouse explores the object. During the maintenance period, the item is not encountered and the strength gradually decreases over time (i.e., the item is forgotten). Finally, during retrieval, if the item's strength is above a given threshold, then the item can be recalled with perfect fidelity (Recall 1), or if the memory strength is below the retrieval threshold, the item is forgotten (Recall 2). Thus, TBI could lead to a decrease in memory function in three ways. First, TBI could lead to a deficit in encoding (encoding hypothesis; Fig. 5B). In terms of strength theory, this would be represented by a decrease in the strength of the item during the initial encoding interval. Alternatively, TBI could cause a problem of memory maintenance (maintenance hypothesis; Fig. 5C), causing injured mice to have a faster decay period (i.e., faster forgetting rate) than sham mice. Finally, TBI mice could have a problem in memory retrieval (retrieval hypothesis; Fig. 5D) and require more memory strength for each individual item to trigger a memory event. Specifically, an increased retrieval threshold for memory-related performance in TBI leads to a poorer retrieval than in sham for a memory of equal strength.

We suggest that the data are most consistent with a decrease in episodic encoding for the following reasons. First, when we analyzed the exploratory behavior of mice as a function of time during the familiarization phase, we found that there was a significant decrease in EB during the first 200 sec of F1 (Fig. 3A–C). These data suggest that TBI mice explore object location less than sham mice specifically during the episodic encoding time window, which results in a decreased ability to recall object location during the test phase. Of note, sham mice do not have an increase in EB during the first 200 sec of F2. Thus, there is only an increase in EB the first time sham mice are placed in the field. This observation makes it less likely that the increase in EB is related to a generic exploration initialization signal. Rather, the increase in EB is specific to the very first time the mouse interacts with the objects, consistent with an episodic encoding signal. If this is the case, then interventions that reverse the deficit in memory performance should also reverse the decrease in EB during F1. We therefore next reversed the memory deficits post-TBI with BCAA therapy, and, consistent with the episodic encoding postulate, we found that the effect of EB was also reversed (Fig. 4). Taken together, these data show that reversing the TBI-related deficit in episodic encoding (as reflected by, and perhaps caused by, the deficiency in exploratory behavior) is associated with a rescue of the memory deficit.

Formalizing the data in this way should yield more insightful experiments. For example, here we suggest that the data are consistent with an encoding problem, not a maintenance problem. To test that, we could run a task that keeps the test interval constant with a short delay (3 min) and change the load of the encoding process parametrically. If the encoding hypothesis is true, there it should be a point at which TBI will not perform as well as sham because the information is less well encoded. If the maintenance hypothesis is true, there will be no difference. We leave this for future research.

An important caveat is that, in similar fashion to other pathologies of memory (Alzheimer's disease, cognitive decline of aging, etc.), TBI likely is a global problem leading to a deficit in encoding, maintenance, and retrieval. However, these processes are theoretically independent34 and have different electrophysiological signatures.35–36 Thus, the question of whether TBI disproportionately affects one of these processes more than the others will lend insight into the neuroanatomical basis of the effects of TBI on memory.

We also note that this article is the first to demonstrate that branched amino-acid therapy reverses spatial memory deficits after TBI. BCAAs serve a dual role in the central nervous system (CNS). In addition to the fundamental use of amino acids for protein synthesis, these specific amino acids (valine, leucine, and isoleucine) are pivotal in glutamate synthesis given that they contribute 50% of the nitrogen in glutamate.37,38 Further, de novo glutamate synthesis contributes a significant amount (approximately 40%) of releasable synaptic glutamate.39,40

Previous work has demonstrated that TBI induced by lateral fluid percussion leads to a significant reduction in ipsilateral BCAA concentration, which can be restored by our dietary therapy.24 Further, previous work has shown that BCAA therapy for 5 days administered 48 h post-injury rescues contextual fear conditioning memory after 7 days post-injury, highlighting the potential neurorestorative role of this therapy. Indeed, BCAA therapy as well as in vitro BCAA application has been shown to also reverse injury-induced shifts in net synaptic efficacy24 as well as an inability to maintain wakefulness.26 Further work is needed to show that BCAA therapy reverses other effects associated with TBI. In particular, there has not been a demonstration that BCAA therapy reverses the in vivo electrophysiological effects of TBI in this TBI model. In contrast, Sham-BCAA mice showed a decreased memory performance. In previous work, we did not see improved performance in sham animals on BCAAs when assayed in contextual fear conditioning. However, the current object spatial-location task might be more sensitive, and it highlights the important aspect of the safety dose for this therapy, which we leave for further research.

We found that neither sham or TBI mice were able to perform the object location-recognition task after 24 h delay. There is always a point at which episodic information will not be able to be retrieved. That is, the expectation is that the mice will not be able to perform the task after some indeterminate long delay, the precise duration of which will depend on multiple factors including, but not limited to, strength of temporal context, duration of the original encoding, salience of encoded objects, arousal state of the mouse, and so forth. However, this “forgetting point” should not be generalized to all episodic memory.

TBI affects EB during familiarization (Fig. 3; Table 1). Here, we suggest that this decrease in EB represents a decrease in episodic encoding in TBI mice. The link between EB and episodic encoding is supported in the extant literature, especially in electrophysiological studies. In rodents, exploratory and oriented-volunteer behaviors are known to be related with theta oscillations in the hippocampus. 41 Theta oscillations are hypothesized to facilitate the formation of maps and episodic memory.42,43 Indeed, theta oscillations are one of the most well-studied electrophysiological markers of encoding.44 Thus, the data support a link between episodic encoding and EB, which is consistent with the hypothesis that TBI disproportionally affects memory encoding.

A limitation in this study is the ability to discern between attention and memory. For example, if TBI led to a global decrease in attention, then there would be an overall decrease in the quality of encoding as well. This relation results from the finding that increasing attention leads to better encoding.32 In general, this is a difficult limitation because attention is a component of the memory process.45 One method to overcome this limitation is to use invasive electrophysiological techniques, which can identify memory processing by measuring hippocampal activation. We leave this as a topic for further research.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute of Child Health and Human Development at the National Institutes of Health (R37-HD059288 to A.S.C.), the National Institute of Neurological Disease and Stroke at the National Institutes of Health (R21NS096618 to A.S.C.), and the post-doctoral training grant T32 HL07713. The authors thank Brian N. Johnson and John F. Burke for helpful discussion and input.

Author Disclosure Statement

A.S.C. and the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia hold a provisional patent for the use of BCAAs as a therapeutic intervention for traumatic brain injury: U.S. Provisional Patent Application Nos. 61/883,526 and 61/812,352, filed under the title “Compositions and methods for the treatment of brain injury.”

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). Report to congress on traumatic brain injury in the United States: epidemiology and rehabilitation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Langlois J.A., Rutland-Brown W., and Wald M.M. (2006). The epidemiology and impact of traumatic brain injury: a brief overview. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 21, 375–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carroll L.J., Cassidy J.D., Holm L., Kraus J., and Coronado V.G.; WHO Collaborating Centre Task Force on Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. (2004). Methodological issues and research recommendations for mild traumatic brain injury: the WHO Collaborating Centre Task Force on Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Rehabil. Med. 43 Suppl., 113–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McAllister T.W., Sparling M.B., Flashman L.A., Guerin S.J., Mamourian A.C., and Saykin A.J. (2001). Differential working memory load effects after mild traumatic brain injury. Neuroimage 14, 1004–1012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paterno R., Folweiler K.A., and Cohen A.S. (2017). Pathophysiology and treatment of memory dysfunction after traumatic brain injury. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 17, 52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baddeley A. (1992). Working memory. Science 255, 556–559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tulving E. (1972). Episodic and semantic memory, in: Organization of Memory. London: Academic, pps. 382–404 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tulving E. (1985). Elements of episodic memory. Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eichenbaum H., and Cohen N.J. (2004). From Conditioning to Conscious Recollection: Memory Systems of the Brain. Oxford Psychology Series, no. 35 Oxford University Press: New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yonelinas A.P. (2002). The nature of recollection and familiarity: a review of 30 years of research. J. Mem. Lang. 46, 441–517 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manns J.R., and Eichenbaum H. (2009). A cognitive map for object memory in the hippocampus. Learn. Mem. 16, 616–624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glisky E.L., Polster M.R., and Routhieaux B.C. (1995). Double dissociation between item and source memory. Neuropsychology 9, 229–235 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moscovitch M. (2008). The hippocampus as a “stupid,” domain-specific module: implications for theories of recent and remote memory, and of imagination. Can. J. Exp. Psychol. 62, 62–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zola-Morgan S., and Squire L. R. (1993). Neuroanatomy of memory. Annual review of neuroscience, 16(1), 547–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tulving E., and Markowitsch H.J. (1998). Episodic and declarative memory: role of the hippocampus. Hippocampus 8, 198–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scoville W.B., and Milner B. (1957). Loss of recent memory after bilateral hippocampal lesions. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 20, 11–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lyeth B.G., Jenkins L.W., Hamm R.J., Dixon C.E., Phillips L.L., Clifton G.L., and Hayes R.L. (1990). Prolonged memory impairment in the absence of hippocampal cell death following traumatic brain injury in the rat. Brain Res. 526, 249–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whiting M.D., and Hamm R.J. (2006). Traumatic brain injury produces delay-dependent memory impairment in rats. J. Neurotrauma 23, 1529–1534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sweet J.A., Eakin K.C., Munyon C.N., and Miller J.P. (2014). Improved learning and memory with theta-burst stimulation of the fornix in rat model of traumatic brain injury. Hippocampus 24, 1592–1600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Euston D.R., Gruber A.J., and McNaughton B.L. (2012). The role of medial prefrontal cortex in memory and decision making. Neuron 76, 1057–1070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eakin K., and Miller J.P. (2012). Mild traumatic brain injury is associated with impaired hippocampal spatiotemporal representation in the absence of histological changes. J. Neurotrauma 29, 1180–1187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hylin M.J., Orsi S.A., Zhao J., Bockhorst K., Perez A., Moore A.N., and Dash P.K. (2013). Behavioral and histopathological alterations resulting from mild fluid percussion injury. J. Neurotrauma 30, 702–715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Müller N.G., and Knight R.T. (2006). The functional neuroanatomy of working memory: contributions of human brain lesion studies. Neuroscience 139, 51–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cole J.T., Mitala C.M., Kundu S., Verma A., Elkind J.A., Nissim I., and Cohen A.S. (2010). Dietary branched chain amino acids ameliorate injury-induced cognitive impairment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107, 366–371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elkind J., Lim M.M., Johnson B.N., Palmer C.P., Putnam B.J., Kirschen M.P., and Cohen A.S. (2015). Efficacy, dosage and duration of action of branched chain amino acid therapy for traumatic brain injury. Front. Neurol. 6, 73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lim M.M., Elkind J., Xiong G., Galante R., Zhu J., Zhang L., and Cohen A.S. (2013). Dietary therapy mitigates persistent wake deficits caused by mild traumatic brain injury. Sci. Transl. Med. 5(215), 215ra173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson B.N., Palmer C.P., Bourgeois E.B., Elkind J.A., Putnam B.J., and Cohen A.S. (2014). Augmented inhibition from cannabinoid-sensitive interneurons diminishes CA1 output after traumatic brain injury. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 19, 435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ennaceur A., and Delacour J. (1988). A new one-trial test for neurobiological studies of memory in rats. 1: Behavioral data. Behav. Brain Res. 31, 47–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bevins R.A., and Besheer J. (2006). Object recognition in rats and mice: a one-trial non-matching-to-sample learning task to study ‘recognition memory’. Nat. Prot. 1, 1306–1311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dix S.L., and Aggleton J.P. (1999). Extending the spontaneous preference test of recognition: evidence of object-location and object-context recognition. Behav. Brain Res. 99, 191–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tulving E. (1995). Organization of memory: quo vadis, in: The Cognitive Neurosciences. Gazzaniga M.S. (ed). MIT Press: Cambridge, MA [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kahana M.J. (2012). Foundations of Human Memory. Oxford University Press: New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 33.Norman D.A., and Wickelgren W.A. (1969). Strength theory of decision rules and latency in retrieval from short-term memory. J. Math. Psychol. 6, 192–208 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eldridge L.L., Engel S.A., Zeineh M.M., Bookheimer S.Y., and Knowlton B.J. (2005). A dissociation of encoding and retrieval processes in the human hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 25, 3280–3286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Montgomery S.M., and Buzsáki G. (2007). Gamma oscillations dynamically couple hippocampal CA3 and CA1 regions during memory task performance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104, 14495–14500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carr M.F., Jadhav S.P., and Frank L.M. (2011). Hippocampal replay in the awake state: a potential substrate for memory consolidation and retrieval. Nat. Neurosci. 14, 147–153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kanamori K., Ross B.D., Kondrat R.W. (1998). Rate of glutamate synthesis from leucine in rat brain measured in vivo by 15N NMR. J. Neurochem. 70, 1304–1315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sakai R., Cohen D.M., Henry J.F., Burrin D.G., Reeds P.J. (2004). Leucine-nitrogen metabolism in the brain of conscious rats: its role as a nitrogen carrier in glutamate synthesis in glial and neuronal metabolic compartments. J. Neurochem. 88, 612–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lapidot A., and Gopher A. (1994). Cerebral metabolic compartmentation. Estimation of glucose flux via pyruvate carboxylase/pyruvate dehydrogenase by 13C NMR isotopomer analysis of D-[U-13C] glucose metabolites. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 27198–27208 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lieth E., LaNoue K.F., Berkich D.A., Xu B., Ratz M., Taylor C., and Hutson S.M. (2001). Nitrogen shuttling between neurons and glial cells during glutamate synthesis. J. Neurochem. 76, 1712–1723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vanderwolf C.H. (1969). Hippocampal electrical activity and voluntary movement in the rat. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 26, 407–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Buzsáki G. (2005). Theta rhythm of navigation: link between path integration and landmark navigation, episodic and semantic memory. Hippocampus 15, 827–840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nyhus E., and Curran T. (2010). Functional role of gamma and theta oscillations in episodic memory. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 34, 1023–1035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Buzsáki G., and Moser E. I. (2013). Memory, navigation and theta rhythm in the hippocampal-entorhinal system. Nat. Neurosci. 16, 130–138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chun M.M., and Turk-Browne N. B. (2007). Interactions between attention and memory. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 17, 177–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dere E., Huston J.P., and De Souza Silva M.A. (2005). Episodic-like memory in mice: simultaneous assessment of object, place and temporal order memory. Brain Res. Brain Res. Protoc. 16, 10–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]