Abstract

Background

Interleukin-33 (IL-33) participates in various types of diseases including cancers. Previous studies of this cytokine in cancers mainly focused on its regulation on immune responses by which IL-33 modulated cancer progression. The IL-33 triggered signals in cancer cells remain unclear.

Methods

We analyzed IL-33 gene expression in human colorectal cancer (CRC) tissues and carried out gene enrichment analysis with TCGA Data Portal. We studied CRC proliferation in vivo by inoculating MC38 tumors in IL-33 transgenic mice. We investigated the cell proliferation in vitro with primary CRC cells isolated from fresh human CRC tissues, human CRC cell line HT-29 and mouse CRC cell line MC38. To evaluate the proliferation modulating effects of recombinant IL-33 incubation and other administrated factors, we measured tumor growth, colony formation, cell viability, and the expression of Ki67 and proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA). We used several inhibitors, prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) neutralizing antibody, ST2 blocking antibody and specific shRNA expressing plasmid to study the pathway mediating IL-33-induced CRC proliferation. The IL-33 receptor ST2 in human CRC tissues was detected by immunohistochemistry staining and western blotting. The ST2-positive or negative subsets of primary CRC cells were acquired by flow cytometry sorting.

Results

We found that IL-33 expression was correlated with the gene signature of cell proliferation in 394 human CRC samples. The MC38 tumors grew more rapidly and the tumor Ki67 and PCNA were expressed at higher levels in IL-33 transgenic mice than in wild-type mice. IL-33 promoted cell growth, colony formation and expression of Ki67 and PCNA in primary CRC cells as well as CRC cell lines. IL-33 activated cycloxygenase-2 (COX2) expression and increased PGE2 production, whereas the COX2 selective inhibitor and PGE2 neutralizing antibody abolished the proliferation promoting effect of IL-33. ST2 blockade, ST2-negative sorting, NF-κB specific inhibitor and NF-κB specific shRNA (shP65) abrogated the COX2 induction caused by IL-33.

Conclusion

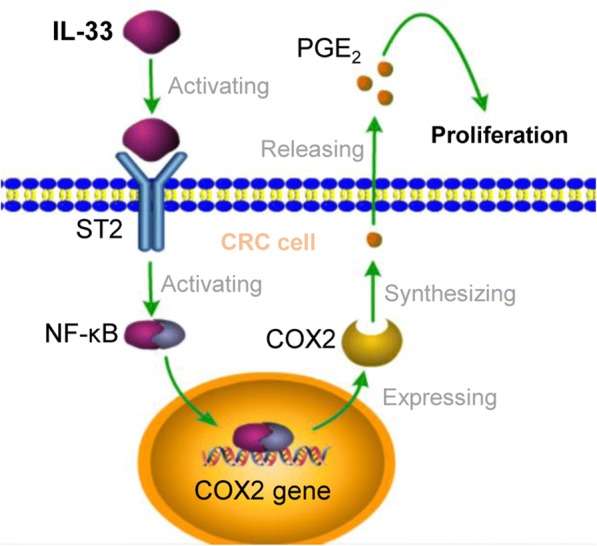

IL-33 facilitates proliferation of colorectal cancer dependent on COX2/PGE2. IL-33 functions via its receptor ST2 and upregulates COX2 expression through NF-κB signaling. Understanding the IL-33 signal transduction in CRC cells provides potential therapeutic targets for clinical treatment.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13046-018-0839-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: IL-33, Proliferation, Colorectal cancer, COX2, PGE2

Background

Interleukin-33 (IL-33), a pro-inflammatory cytokine, displays immunomodulatory functions by promoting inflammatory responses and driving Th2-type immune responses [1–3]. IL-33 mediates its biological effects mainly through specific receptor ST2, a member of Toll like receptor family [2, 4, 5]. IL-33 combined with ST2 stimulates numerous signal proteins by phosphorylation to mediate a series of physiological and pathological processes [1, 6]. IL-33 mediated pancreatic myofibroblast proliferation and migration by promoting IκBα and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) phosphorylation and inducing inflammatory mediators [7]. IL-33/ST2 axis promoted NF-κB-dependent IL-6 and IL-8 production in human fibroblasts [8]. IL-33 activated NF-κB signal in cardiomyocytes via upregrulating phenylephrine and angiotensin II to regulate cardiac fibrosis and hypertrophy [9]. IL-33/ST2 axis accelerated cytokine secretion from vascular endothelial cells to induce inflammatory reaction by activating extracellular signal-regulated kinase1/2 (ERK1/2) [10]. The increasing amount of evidence implies that IL-33-triggered signals may be involved in cancer progression. IL-33 is predominantly expressed in endothelial and epithelial cells [1, 11, 12]. Elevated levels of IL-33 protein were detectable in sera from non-small cell lung cancer (NSLC) patients, gastric cancer patients, hepatic carcinoma patients and metastatic pancreatic carcinoma patients [13–15]. Abnormally high IL-33 expression was also found in human colorectal cancer (CRC) tissues [4].

Previous studies showed IL-33 modulated tumor progression indirectly by regulating tumor stroma cells. IL-33/ST2 negatively regulated antitumor responses by promoting the function of regulatory T cells (Tregs) [16] or stimulating accumulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) [17, 18]. In oncogene-induced cholangio carcinoma, IL-33 stimulated cholangiocytes to produce the pro-tumorigenic cytokine IL-6 [19]. Recent studies revealed that IL-33 could directly regulate cancer cells [4, 20, 21]. Carcinoma-associated fibroblasts-derived IL-33 promoted cancer cell epithelial-to-mesenchymal transdifferentiation (EMT) to regulate head and neck squamous cell carcinoma invasion and migration [22]. The function of IL-33/ST2 axis in cancer cells is poorly understood.

IL-33-associated inflammation has profound influence on tumorigenesis of CRC [23, 24]. IL-33/ST2 signal impaired permeability of epithelial barrier and triggered immune cells to produce IL-6 during CRC progression [25, 26]. Stroma-derived IL-33 drove CRC neoplastic transformation from adenoma to carcinoma by promoting angiogenesis [27]. IL-33 induced CRC carcinogenesis and liver metastasis by remodeling tumor microenvironment and activating angiogenesis [28]. In this study, we found that IL-33 was positively correlated with proliferation of CRC both in human data and in transgenic mice. We further investigated the direct proliferation promoting role of IL-33 with primary CRC cells and CRC cell lines.

Methods

TCGA data and statistics analysis

The global gene expression data of 394 colorectal cancer samples were acquired from the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database (https://gdc.cancer.gov/). The clinical information of CRC patients was listed in Additional file 1: Table S1. Gene expression levels of IL-33, ST2 and COX2 included in the data were subjected to Kolmogorov-Smirnov (K-S) test of normality. The gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was performed using the program GSEA v2.2.0. Gene sets for GSEA were obtained from the Molecular Signature Database (MSigDb) (http://www.broadinstitute.org/gsea/msigdb/index.jsp.). The Log2-rank test was used to make gene enrichment statistical comparisons. P-value (P < 0.05) was regarded statistically significant. Pearson’s correlation test was performed using SPSS software with COX2 and ST2 expression levels extracted from the downloaded data. P-value (P < 0.05) was regarded statistically significant. For experimental data, statistical analysis was performed using the GraphPad Prism 5 software. Student's t-test was used for comparison of paired groups. Multiple group comparisons were performed using analysis of variance, ANOVA.

Reagents

PGE2 and human recombinant IL-33 were purchased from ProteinTech. The mouse recombinant IL-33 was purchased from Pepro Tech. The following antibodies were used: ST2 antibody (R&D systems), PGE2 antibody (Cayman), COX2 antibody (Abclonal), and control IgG (Santa Cruz). The following chemical reagents were used: SB203580 (Cayman, 10 μg/mL), PD98059 (Cayman, 20 μg/mL), SP600125 (Cayman, 10 μg/mL), BIX01294 (MCE, 2 μM), 5-Aza (Sigma, 10 μM), SC-560 (Cayman, 0.1 μg/mL), Celecoxib (Sigma, 20 μg/mL) and BAY11–7082 (Cayman, 10 μM).

Cell lines and animals

Primary CRC cell lines were isolated as described previously [4, 29] from fresh human CRC tissues of three patients. Human CRC cell line HT29 was bought from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). Murine CRC cell line MC38 was provided by Dr. Weiping Zou (Michigan, USA) and was tested in 2011 [30]. These cells were all cultured in RPMI1640 medium with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 IU/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin at 37 °C in a cell incubator with a 5% (v/v) CO2 humidified atmosphere. C57/BL6 wild type mice were bought from Beijing HFK Bioscience Co. Ltd. C57/BL6 IL-33 transgenic mice were from Dr. Zhanguo Li (Beijing, China) and Dr. Lianfeng Zhang (Beijing, China) [4]. All mice were housed in specific pathogen free (SPF) animal room of Tongji Medical College.

Animal models

Six-week-old IL-33 transgenic mice and wild-type male C57/BL6 mice were used in tumor growth experiments. Each mouse was inoculated with 1 × 106 MC38 cells subcutaneously on the back. Once visible tumors generated, tumor sizes were measured every 2 days. Tumor volumes were calculated by the formula V = 1/2 × length×width2 (mm3). For comparing the tumor growth rates, seven mice were set in each group. Another same set of experiment was performed for harvesting tumor tissues.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry staining was performed as described previously [31]. The tumors removed from the wild-type or IL-33 transgenic mice at Day 22 post tumor inoculation were fixed with 4% formaldehyde and embedded with paraffin. The sections were labeled with anti-Ki67 antibody (Arigo, 1:200) and anti-PCNA antibody (Boster, 1:200). Quantification of Ki67 and PCNA expression was independently performed by two pathologists. The positively staining cells were quantified by ImageJ software. Twenty CRC tissues and adjacent normal tissues were obtained from surgery in Union hospital (Wuhan) with the permission of each patient. The ST2 staining was performed with anti-ST2 antibody (R&D, 1:200).

Measurement of cell viability

Primary CRC cells were seeded in 96-well plates (6000 cells per well) and incubated with RPMI1640 medium with IL-33 (0, 50, 100, 200 ng/mL) or PGE2 (50 ng/mL). Cell viability was measured with the Cell Counting Kit-8 (Biosharp) at 24th, 48th or 72nd h. The curves of cell viability were plotted by the absorbance of each time point.

Real-time quantitative PCR

Primary CRC cells, HT29 cells or MC38 cells were seeded in 12-well plates (2 × 105 cells per well) and incubated with the following reagents: human/mouse recombinant IL-33 proteins (0, 50 or 100 ng/mL), celecoxib (20 μg/mL), ST2 antibody (2 μg/mL) or BAY11–7082 (10 μM) for 24 h. Three parallel wells were set for each treatment. Total RNA was isolated with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and was reversely transcribed into complementary DNA with RNA reverse transcriptase (Vazyme). Real-time PCR was performed on ABI StepOne Plus Detector System (Applied Biosystem). Relative mRNA expression of human genes was normalized to GAPDH, and for mouse genes the mRNA levels were normalized to mouse Hprt gene. Each experiment was repeated three times and representative results were shown. The primers used are listed in Additional file 1: Table S2.

Flat colony formation

CRC cells were seeded in 12-well plates at a density of 500 viable cells per well. Then the cells were incubated in RPMI1640 medium with recombinant IL-33 protein (added at Day 1, 3 and 5), celecoxib, the ST2 antibody or the BAY11–7082. Colonies were photographed and counted at Day 10 or 15 to allow all wells undergoing different treatments to generate visible colonies. Three parallel wells were set for each treatment. Each experiment was repeated three times and representative results were shown.

Western blotting

Primary CRC cells, HT29 cells or MC38 cells were seeded in 6-well plates (5 × 105 cells per well). The CRC cells receiving different treatments were scraped and collected by low speed centrifugation and lysed using Cell Lysis Buffer. The Western blotting was performed as previously described [32]. Blots were performed with a COX2 antibody (Abcolonal), ST2 antibody (R&D systems), NF-κB P65 antibody (CUSABIO) and β-actin antibody (Proteintech). Specific bands were detected using ECL detection reagents (Millipore, USA). Each experiment was repeated three times and representative results were shown.

ELISA for quantification of PGE2

Primary CRC cells seeded in 6-well plates (5 × 105 cells per well) were incubated in RPMI1640 medium or RPMI1640 medium containing rhIL-33 protein (100 ng/mL) for 24 h. The culture supernatants were collected. The concentration of PGE2 was measured by the ParameterTM PGE2 assay kit (R&D) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Flow cytometry analysis and sorting

Primary CRC cells (5 × 106) were collected from culture plates by low speed centrifugation and made into signal-cell suspensions. Primary CRC cells were stained with PE-conjugated specific antibody to ST2 (bs-2382R, Bioss, China) and PE-conjugated isotype IgG (bs-0295P-PE, Bioss, China). The sample was diluted into a concentration of 2 × 106 cells/mL for sorting. The sorting was performed by a high speed flow sorter (FACSAria II, BD). The sorting system was fluxed using ethanol 70% for 10 min to reduce pollution. Sheath fluid was using autoclaved and filtered (0.22 μm) phosphate saline buffer (1 × PBS). Sorting rate typically was 3000 events/s, and cells were acquired at a rate of 300–500 cells/s. By comparing to the negative control, the PE positively stained subset was gated for sorting as the ST2-positive subset of primary CRC cells. The rest cells were collected and used as ST2-negative primary CRC cells. Cells were recovered into a 15 mL Eppendorf tube with washing buffer. Before being used for experimental assay, the sorted ST2-positive and ST2-negative cells were subjected to flow cytometry analysis with the same program and testing with the same gating condition used for sorting. Purity of sorted cell subsets was > 90% as verified by flow cytometry. Flow cytometry data was analyzed by Flow Jo 7.6.1 software.

Results

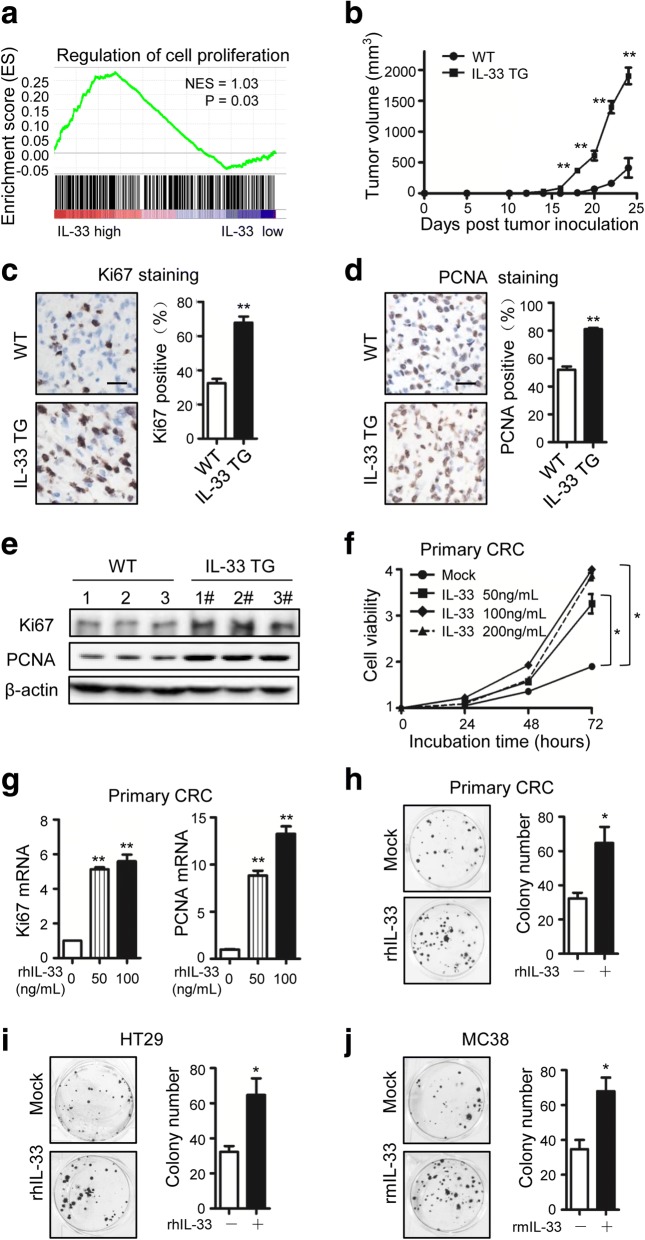

IL-33 promotes the proliferation of CRC cells

To investigate the signaling of IL-33 in CRC, we analyzed the gene expression data from TCGA Data Portal that consisted of 394 CRC samples. Enrichment analysis revealed that the gene signature of cell proliferation was significantly correlated with IL-33 expression (Fig. 1a; Additional file 1: Table S3). This indicates that IL-33 might regulate the proliferation of CRC cells. Thus, we performed experiments to test this notion. By inoculating MC38 CRC cells in animals, we found the tumor growth in IL-33 transgenic mice was more rapidly than that in wild-type mice (Fig. 1b). The immunohistochemical staining showed that the cell proliferation marker Ki67 and the proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) were expressed significantly higher in the tumors generated in IL-33 transgenic mice than in the tumors from wild-type mice (Fig. 1c, d). The increased Ki67 and PCNA expression in the tumors from IL-33 transgenic mice were verified by Western blotting (Fig. 1e). To determine whether IL-33 facilitated the proliferation of CRC cells directly or via regulating other factors in vivo, we incubated primary CRC cells isolated from human cancer tissues with recombinant IL-33 protein. We found that IL-33 increased cell viability of primary CRC cells and upregulated the expression of Ki67 and PCNA in a dose dependent manner (Fig. 1f, g). To confirm the direct effects of IL-33 on the proliferation of CRC cells, we performed colony formation assay with human CRC cell line HT-29, mouse CRC cell line MC38 as well as the primary human CRC cells. IL-33 significantly facilitated the colony formation of all the three types of cells (Fig. 1h, i, j). Therefore, we concluded that IL-33 accelerated proliferation of CRC.

Fig. 1.

IL-33 promotes CRC proliferation both in vivo and in vitro. a Correlation between IL-33 transcripts and the genes involved in the regulation of cell proliferation in CRC. Gene set enrichment analysis was performed using CRC TCGA database. NES = 1.03, P = 0.03. b Growth curves of MC38 tumors inoculated in IL-33 transgenic mice (IL-33 TG) or wild-type mice (WT). n = 7. c, d Immunohistochemical staining of Ki67 (c) and PCNA (d) in the MC38 tumors recovered from wild-type and IL-33 transgenic mice at Day 22 post inoculation. The representative images and the statistical proportions of positive cells are shown. Scale bar, 50 μm. n = 7. Data expressed as mean ± SEM. **, P < 0.01. e Western blot of Ki67 and PCNA in the MC38 tumors recovered from wild-type and IL-33 transgenic mice. n = 3. f Cell viabilities of human primary CRC cells incubated with 0, 50, 100 or 200 ng/mL of rhIL-33 in medium at 24th, 48th and 72nd h. Six parallel wells were set for each treatment. The experiment was performed three times. Data expressed as mean ± SEM. * P < 0.05. g Ki67 and PCNA mRNA levels in primary CRC cells incubated with rhIL-33 (0, 50 or 100 ng/mL) for 24 h. Each experiment was performed three times. Three parallel wells were set for each treatment. Data expressed as mean ± SEM. ** P < 0.01. h, i, j The flat colony formation with 500 primary CRC cells (h) and 500 HT29 cells (i) incubated with rhIL-33 (100 ng/mL) and the flat colony formation with 500 MC38 cells (j) incubated with rmIL-33 (100 ng/mL). The number of colony was counted at Day 10. Each experiment was performed three times. Three parallel wells were set for each treatment. The representative images of colonies and the statistical data are shown. Data expressed as mean ± SEM. * P < 0.05

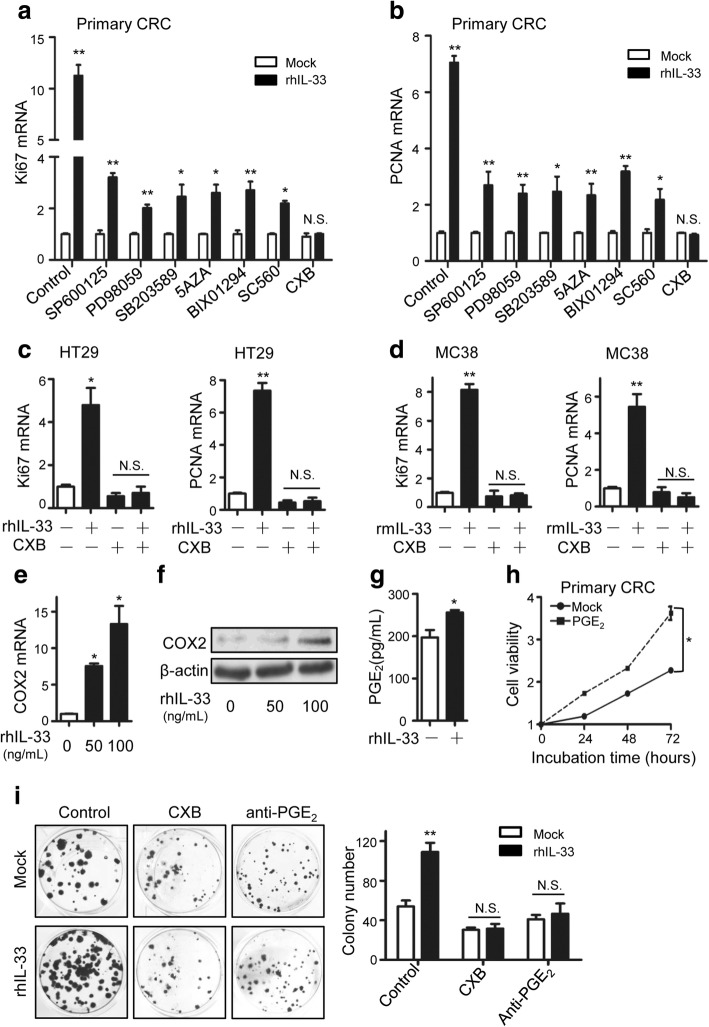

IL-33 facilitates CRC proliferation dependent on COX2/PGE2

We next sought to investigate the mechanism how IL-33 facilitated CRC proliferation. We screened tumor proliferation associated signals: DNA and histone methylation and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) synthesis using inhibitors. The IL-33-induced Ki67 and PCNA were detected when the primary CRC cells were treated with the P38 inhibitor SB203580, the MAPK/ERK kinase (MEK) inhibitor PD98059, the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) inhibitor SP600125, the histone methyltransferase inhibitor BIX01294, the DNA methyltransferase inhibitor 5-Aza, COX1 selective inhibitor SC-560, and the COX2 selective inhibitor celecoxib. We found that in celecoxib treated primary CRC cells IL-33 did not elevate Ki67 or PCNA (Fig. 2a, b). In CRC cell lines HT-29 and MC38, celecoxib also effectively abrogated the IL-33-induced elevation of Ki67 and PCNA (Fig. 2c, d). COX2 functions as a key enzyme in the synthesis of PGE2 that potently accelerates tumor proliferation [33–35]. These indicate that COX2/PGE2 might mediate the proliferation promoting function of IL-33. In accordance with this notion, IL-33 incubation increased COX2 mRNA and protein levels in the primary CRC cells in a dose dependent manner (Fig. 2e, f). CRC cells incubated with IL-33 produced significantly higher level of PGE2 (Fig. 2g). The artificially synthesized PGE2 increased the cell viability of the primary CRC cells (Fig. 2h), verifying its function in promoting tumor proliferation characterized previously. To confirm the autocrine of PGE2 mediated the IL-33-induced acceleration of proliferation, we performed colony formation with CRC cells incubated with a PGE2 neutralizing antibody as well as the inhibitor celecoxib. Both PGE2 neutralizing antibody and celecoxib blocked the increase of colony numbers induced by IL-33 (Fig. 2i). Together, IL-33 facilitated CRC proliferation via increasing PGE2 production.

Fig. 2.

COX2/PGE2 mediates the proliferation promoting function of IL-33. a, b The relative mRNA levels of Ki67 (a) and PCNA (b) in primary CRC cells responding to rhIL-33 (100 ng/mL) incubation and/ or indicated inhibitors (SB203580, 10 μg/mL; PD98059, 20 μg/mL; SP600125, 10 μg/mL; BIX01294, 2 μM; 5Aza, 10 μM; SC560, 0.1 μg/mL; celecoxib, 20 μg/mL) for 24 h. c The relative mRNA levels of Ki67 and PCNA in HT-29 cells incubated with rhIL-33 (100 ng/mL) or/ and celecoxib (CXB) (20 μg/mL) in medium for 24 h. d The relative mRNA levels of Ki67 and PCNA in MC38 cells incubated with rmIL-33 (100 ng/mL) or/ and celecoxib (CXB) (20 μg/mL) in medium for 24 h. e, f The mRNA (e) and protein (f) expression of COX2 in primary CRC cells incubated with 0, 50 or 100 ng/mL of rhIL-33 in medium for 24 h. g PGE2 concentrations in the supernatants of primary CRC cells incubated with rhIL-33-contained RPMI medium or blank RPMI medium for 48 h. h Cell viabilities of primary CRC cells incubated with or without PGE2 (50 ng/mL) in medium. i The flat colony formation of primary CRC cells incubated for 15 days in medium containing different factors as indicated (IL-33, 100 ng/mL; celecoxib, 20 μg/mL; anti-PGE2, 2 μg/mL). The representative images of colonies and the statistical data are shown. Three parallel wells were set for each treatment. Each experiment was performed three times. Data expressed as mean ± SEM. * P < 0.05. ** P < 0.01

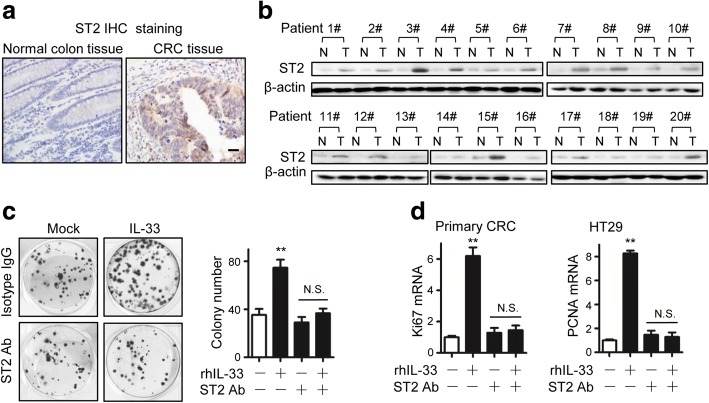

The receptor ST2 mediates the proliferation promoting function of IL-33

We previously reported that cultured CRC cells expressed functional IL-33-recceptor ST2 [4]. Here we further detected the receptor in human CRC. By immunohistochemical staining, we found positive ST2 expression in most of CRC samples (19/20), whereas ST2-positive staining was rarely observed in the adjacent normal tissues (Fig. 3a). The ST2 expression in CRC tissues was also verified by Western blotting (Fig. 3b). Although ST2 has been identified as IL-33 receptor, IL-33 can function in an ST2-independent fashion [36]. We checked whether IL-33 promoted CRC proliferation through its receptor by using an ST2 blockade antibody. ST2 blockade abolished the increase of colony numbers caused by IL-33 incubation (Fig. 3c). The antibody treatment also suppressed the IL-33-elevated Ki67 and PCNA levels (Fig. 3d). Thus, we demonstrated that IL-33 facilitates CRC proliferation by signaling through its receptor ST2.

Fig. 3.

IL-33 facilitated CRC proliferation by signaling its receptor ST2. a Immunohistochemical staining of ST2 in the CRC tissues and the adjacent normal colon tissues (20 pairs). The representative images are shown. Scale bar, 20 μm. b ST2 expression levels in the paired CRC tissues (T) and the adjacent normal colon tissues (N) analyzed by Western blotting. c The flat colony formation of primary CRC cells incubated for 15 days in RPMI medium or RPMI medium containing rhIL-33 (100 ng/mL) or/ and ST2 antibody (2 μg/mL). Three parallel wells were set for each treatment. Each experiment was performed three times. The representative images of colonies and the statistical data are shown. Data expressed as mean ± SEM. ** P < 0.01. d Ki67 and PCNA expression in primary CRC cells responding to the incubation with rhIL-33 (100 ng/mL) or/ and ST2 antibody (2 μg/mL) for 24 h. Three parallel wells were set for each treatment. Each experiment was performed three times. Data expressed as mean ± SEM. ** P < 0.01

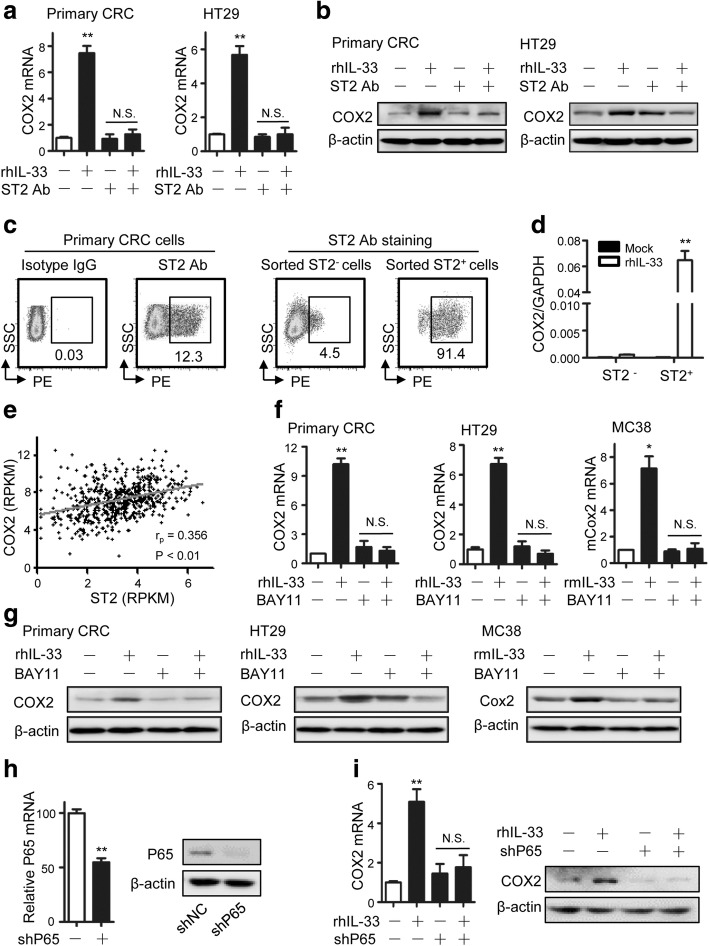

IL-33/ST2 axis induces COX2 expression by activating NF-κB signaling

When ST2 was blocked, IL-33 did not upregulate the mRNA and protein levels of COX2 in primary CRC cells or HT-29 cells anymore (Fig. 4a, b). As shown by flow cytometry assay, 12.3% of primary CRC cells were obviously ST2 positive (Fig. 4c). To further verify COX2 induction was dependent on ST2, we sorted the ST2-positive subset and the ST2-negative subset from primary CRC cells (Fig. 4c). The folds of COX2 induction caused by IL-33 were markedly higher in ST2-positive CRC cells than in ST2-negative CRC cells (Fig. 4d). By analyzing TCGA data, we found that COX2 levels in human CRC were positively correlated with ST2 expression (Fig. 4e). These demonstrate that IL-33 induces COX2/PGE2 via ST2-mediated signaling.

Fig. 4.

IL-33/ST2 upregulates COX2 expression through NF-κB signaling. a,b The COX2 mRNA (a) and protein (b) expression in primary CRC cells or HT29 cells responding to the incubation with rhIL33 (100 ng/mL) or/ and ST2 antibody (2 μg/mL) for 24 h. Each experiment was performed three times. Data expressed as mean ± SEM. ** P < 0.01. c ST2 expression distribution in primary CRC cells, sorted ST2-negative and sorted ST2-positive primary CRC cells. The proportion of ST2 positive subset is shown. d Relative COX2 mRNA levels in ST2-negative or ST2-positive primary CRC cells responding to IL-33 (100 ng/mL) incubation for 24 h in 24-well plates (1 × 105 cells per well). Three parallel wells were set for each treatment. Data expressed as mean ± SEM. ** P < 0.01. e The correlation between COX2 and ST2 transcripts in 394 CRC samples recorded in TCGA database. These two sets of data both have a normal distribution. Pearson r = 0.356, P < 0.01. f COX2 mRNA levels in primary CRC cells, HT29 cells and MC38 responding to the incubation with IL-33 (100 ng/mL) or/ and BAY11–7082 (10 μM). Three parallel wells were set for each treatment. Each experiment was performed three times. Data expressed as mean ± SEM. * P < 0.05. ** P < 0.01. g COX2 protein levels in primary CRC cells, HT29 cells and MC38 responding to the incubation with IL-33 (100 ng/mL) or/ and BAY11–7082 (10 μM). Each experiment was performed three times. h The knocking-down efficiency of NF-κB P65 in HT29 cells. The P65 mRNA (left panel) and protein (right panel) were both detected. Data expressed as mean ± SEM. ** P < 0.01. i COX2 mRNA (left panel) and protein (right panel) levels responding to IL-33 incubation (100 ng/mL) for 24 h in HT29 cells transfected with short hairpin RNA expressing plasmid against NF-κB P65 (shP65) or nonsense RNA expressing plasmid (shNC). Each experiment was performed three times. Data expressed as mean ± SEM. ** P < 0.01

Previous studies have revealed the COX2 gene activation relies on assistance of several transcriptional factors including NF-κB, NF-AT, C/EBP and CREB [37–39]. IL-33/ST2 axis could directly stimulate NF-κB nuclear factors in different cell types [40]. Thus, we checked whether the NF-κB signaling mediated the process where IL-33/ST2 axis induced COX2. As expected, the NF-κB specific inhibitor blocked the induction of COX2 mRNA and protein caused by IL-33 in primary CRC cells, HT29 cells and MC38 cells (Fig. 4f, g). In line with this, the NF-κB specific shRNA (shP65) repressed COX2 mRNA and protein levels induced by IL-33 (Fig. 4h, i). Therefore, we concluded that IL-33/ST2 axis induces COX2 through NF-κB signaling.

Discussion

Previous studies have indicated that IL-33 could regulate proliferation of some types of cells directly or indirectly. IL-33 upregulated CCL2/CCR2 by activating NF-κB and ERK1/2 to facilitate proliferation of decidual sromal cells [41]. Macrophage-derived IL-33 at the maternal-fetal interface promoted trophoblast cells proliferation by activating AKT and ERK1/2 signaling [42]. IL-33 promoted epidermal proliferation to influence wound healing process [43]. IL-33 also induced proliferation of myeloid lineage cells [44] and pancreatic myofibroblasts [7]. The IL-33-triggering signals in cancer cells are poorly understood because cancer cells do not always express its unique receptor ST2. Our previous work revealed that ST2 was expressed in primary CRC cells and HT-29 cells [4]. IL-33 is positive correlated with the CRC proliferation both in human data and in animal experiments (Fig. 1a, b). IL-33 may regulate tumor growth by affecting stromal cells or immune responses [17, 18, 27, 28]. The GSEA showed low degree but statistically significant correlation (Fig. 1a, NES = 1.03, P = 0.03) between IL-33 and proliferation regulation gene sets. IL-33 exerts multifunction in cancer progression besides cell proliferation such as immunomodulatory functions by producing chemokines, promoting inflammatory responses, driving Th2-type immune responses, and enhancing cancer stem-like properties [45–47]. Here, we highlight that the IL-33/ST2 axis in CRC cells accelerates proliferation.

By screening the proliferation associated signals, we found that the COX2 inhibitor celecoxib blocked IL-33-induced CRC proliferation. The other six inhibitors also partly impaired the induction-folds of Ki67 and PCNA. Previous studies have revealed that COX2 expression can be reduced by the JNK inhibitor SP600125 [48], the ERK/MAPK inhibitor SB203589 [49], and MEK1/2 inhibitor PD98059 [50]. DNA methyltransferase 5-Aza and the histone methyltransferase inhibitor BIX02189 also regulated COX2 expression [51, 52]. The inhibitor SC-560 could reduce total PGE2 production through inhibiting COX1, although it did not inhibit COX2 at the used concentration [53]. Therefore, we speculated that these six inhibitors may modulate the induction folds of Ki67 and PCNA through regulating COX2 and PGE2. However, we think that there may be other possibilities to explain the effects of these inhibitors. DNA methyltransferase, JNK, ERK and MAPK are involved in the mechanism of COX2 induced proliferation [54–56]; so it is reasonable that the inhibitors of these signals partly impair the effect of COX2 on Ki67 and PCNA expression. Therefore, we hypothesized that COX2/PGE2 dominantly mediated IL-33-induced CRC proliferation and performed the following experiments.

It is well known that COX2, a key enzyme for PGE2 synthesis, can be effectively inhibited by the FDA-approved drug celecoxib [57, 58]. We have circumspectly selected appropriate dosages of SC-560 and celecoxib to inhibit COX1 and COX2, respectively, as their selectivity depends on the concentrations [59–61]. COX2 expression and PGE2 production in CRC cells could be elevated by IL-33. Even though celecoxib exhibited complete blockade effect, it was insufficient to certify the COX2/PGE2-dependence of IL-33-induced proliferation. This was due to the pharmacodynamics complexity of celecoxib. Celecoxib is usually used as a selective inhibitor of COX2 to prevent PGE2 production, but it also exerts effects via other mechanisms. Celecoxib inhibits interleukin-12 subunit folding and secretion by a COX2-independent mechanism involving chaperones of the endoplasmic reticulum [62]. Celecoxib inhibits proliferation of a head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cell line through ER stress response that was proved as a COX2-independent anticancer mechanism [63]. To exclude these COX2-independent mechanisms, we have further provided evidence. The PGE2 neutralization assay well demonstrated that PGE2 mediated the IL-33-induced proliferation. Therefore, we report that IL-33 facilitates proliferation of CRC cells by a COX2/PGE2-dependent mechanism.

COX2 and PGE2 exert critical roles in promoting CRC progression [33, 64]. The mechanism of PGE2-induced CRC proliferation has been well described. The receptor EP2 signaled by PGE2 promotes CRC proliferation through a Gs-axin-beta-catenin signaling axis [65]. PGE2 combines the other receptor EP4 to stimulate CRC proliferation via phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway [66]. PGE2 also activated Ras-mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade to induce intestinal adenoma growth [34].

The recombinant IL-33 concentration used for in vitro experiments are much higher than detected in vivo concentrations [14]. We consider that the biological activity of recombinant IL-33 protein is poorer than endogenous IL-33. This distinction on IL-33 activity may result from the IL-33 cleavage mechanisms. Evidence revealed that full-length IL-33 can be cleaved into a more bioactive form by many proteases in vivo [67, 68]. The cleaved IL-33 has a 10 to 30-fold higher activity than full-length IL-33 in cellular assays [67, 68]. Because of this, many researchers chose much higher doses of recombinant IL-33 for in vitro experiments than in vivo concentrations [4, 69–71]. Thus, the IL-33 concentrations we used in this study are reasonable.

Conclusion

Therefore, we suggest a model to illustrate how IL-33 facilitates CRC proliferation (Fig. 5). IL-33/ST2 axis upregulates COX2 expression through NF-κB signaling, and consequently increases PGE2 production; the elevated PGE2 mediates the proliferation promoting function of IL-33.

Fig. 5.

The pathway through which IL-33 stimulates the proliferation signaling of CRC cells

Additional file

Table S1. Characteristics of the colorectal cancer patients analyzed in this study. Table S2. The primers used in this study. Table S3. The output of the Gene Set Enrichment Analysis. (DOC 604 kb)

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Zhanguo Li (Beijing University Medical School People’s Hospital, Beijing, China) and Dr. Lianfeng Zhang (Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, China) for generously providing IL33 transgenic mice. We also thank Dr. Weiping Zou (University of Michigan School of Medicine, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA) for providing MC38 CRC cells. We thank Dr. Ying Zhu (Collage of Life Science, Wuhan University, Wuhan, China) and Dr. Shi Liu (Collage of Life Science, Wuhan University, Wuhan, China) for providing shP65 expressing plasmid.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China Programs 81502572, 81272559, and 81572866; the International Science and Technology Corporation Program of Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology S2014ZR0340; the Science and Technology Program of Chinese Ministry of Education 113044A; the Independent Innovation Program of Huazhong University of Science and Technology 2014QN067; the Frontier Exploration Program of Huazhong University of Science and Technology 2015TS153; the Natural Science Foundation Program of Hubei Province 2015CFA049; he Integrated Innovative Team for Major Human Diseases Program of Tongji Medical College, HUST, and the Hubei Hundreds of Talents Program.

Availability of data and materials

The data and materials of this study are available from the corresponding authors for reasonable requests.

Abbreviations

- COX2

Cycloxygenase-2

- CRC

Colorectal cancer

- IL-33

Interleukin-33

- PCNA

Proliferating cell nuclear antigen

- PGE2

Prostaglandin E2

Authors’ contributions

LW, ZW, GW and YL designed the study. YL, JS, SQ, JZ, DP and ZC. performed these experiments. YL carried out statistical analysis of experimental data and flow cytometry. JS carried out cell viability assay, gene enrichment analysis, flat colony formation and immunohistochemistry staining. SQ carried out animal experiments. JZ, DP and ZC participated in qRT-PCR and western blot. YL and JS wrote the manuscript. GW, ZW, and LW inspected the experiments and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The experiments with animals and human samples in this study were conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Tongji Medical College at Huazhong University of Science and Technology (Wuhan, Hubei, China).

Consent for publication

All patients signed informed consent for the publication of the clinical images and their clinical details.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yongkui Li, Email: lyklxq@126.com.

Jie Shi, Email: sj199011@yeah.net.

Shanshan Qi, Email: 13212746481@163.com.

Jian Zhang, Email: 13628649365@163.com.

Dong Peng, Email: donnapd@163.com.

Zhenzhen Chen, Email: 272171662@qq.com.

Guobin Wang, Email: wgb@hust.edu.cn.

Zheng Wang, Email: zhengwang@hust.edu.cn.

Lin Wang, Email: lin_wang@hust.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Liew FY, Pitman NI, McInnes IB. Disease-associated functions of IL-33: the new kid in the IL-1 family. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10(2):103–110. doi: 10.1038/nri2692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmitz J, Owyang A, Oldham E, Song Y, Murphy E, McClanahan TK, Zurawski G, Moshrefi M, Qin J, Li X, et al. IL-33, an interleukin-1-like cytokine that signals via the IL-1 receptor-related protein ST2 and induces T helper type 2-associated cytokines. Immunity. 2005;23(5):479–490. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saigusa R, Asano Y, Taniguchi T, Hirabayashi M, Nakamura K, Miura S, Yamashita T, Takahashi T, Ichimura Y, Toyama T, et al. Fli1-haploinsufficient dermal fibroblasts promote skin-localized transdifferentiation of Th2-like regulatory T cells. Arthritis research & therapy. 2018;20(1):23. doi: 10.1186/s13075-018-1521-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fang M, Li Y, Huang K, Qi S, Zhang J, Zgodzinski W, Majewski M, Wallner G, Gozdz S, Macek P, et al. IL33 promotes Colon Cancer cell Stemness via JNK activation and macrophage recruitment. Cancer Res. 2017;77(10):2735–2745. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dinarello CA. An IL-1 family member requires caspase-1 processing and signals through the ST2 receptor. Immunity. 2005;23(5):461–462. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kakkar R, Lee RT. The IL-33/ST2 pathway: therapeutic target and novel biomarker. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7(10):827–840. doi: 10.1038/nrd2660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nishida A, Andoh A, Imaeda H, Inatomi O, Shiomi H, Fujiyama Y. Expression of interleukin 1-like cytokine interleukin 33 and its receptor complex (ST2L and IL1RAcP) in human pancreatic myofibroblasts. Gut. 2010;59(4):531–541. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.193599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ivanov VN, Zhou H, Ghandhi SA, Karasic TB, Yaghoubian B, Amundson SA, Hei TK. Radiation-induced bystander signaling pathways in human fibroblasts: a role for interleukin-33 in the signal transmission. Cell Signal. 2010;22(7):1076–1087. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sanada S, Hakuno D, Higgins LJ, Schreiter ER, McKenzie AN, Lee RT. IL-33 and ST2 comprise a critical biomechanically induced and cardioprotective signaling system. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(6):1538–1549. doi: 10.1172/JCI30634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aoki S, Hayakawa M, Ozaki H, Takezako N, Obata H, Ibaraki N, Tsuru T, Tominaga S, Yanagisawa K. ST2 gene expression is proliferation-dependent and its ligand, IL-33, induces inflammatory reaction in endothelial cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2010;335(1–2):75–81. doi: 10.1007/s11010-009-0244-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pichery M, Mirey E, Mercier P, Lefrancais E, Dujardin A, Ortega N, Girard JP. Endogenous IL-33 is highly expressed in mouse epithelial barrier tissues, lymphoid organs, brain, embryos, and inflamed tissues: in situ analysis using a novel Il-33-LacZ gene trap reporter strain. J Immunol. 2012;188(7):3488–3495. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cayrol C, Girard JP. Interleukin-33 (IL-33): a nuclear cytokine from the IL-1 family. Immunol Rev. 2018;281(1):154–168. doi: 10.1111/imr.12619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun P, Ben Q, Tu S, Dong W, Qi X, Wu Y. Serum interleukin-33 levels in patients with gastric cancer. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56(12):3596–3601. doi: 10.1007/s10620-011-1760-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bergis D, Kassis V, Ranglack A, Koeberle V, Piiper A, Kronenberger B, Zeuzem S, Waidmann O, Radeke HH. High serum levels of the Interleukin-33 receptor soluble ST2 as a negative prognostic factor in hepatocellular carcinoma. Transl Oncol. 2013;6(3):311–318. doi: 10.1593/tlo.12418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hu LA, Fu Y, Zhang DN, Zhang J. Serum IL-33 as a diagnostic and prognostic marker in non- small cell lung cancer. Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention : APJCP. 2013;14(4):2563–2566. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2013.14.4.2563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schiering C, Krausgruber T, Chomka A, Frohlich A, Adelmann K, Wohlfert EA, Pott J, Griseri T, Bollrath J, Hegazy AN, et al. The alarmin IL-33 promotes regulatory T-cell function in the intestine. Nature. 2014;513(7519):564–568. doi: 10.1038/nature13577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang JR, Tsai YC, Chang YJ, Wu JC, Hung JT, Lin KH, Wong CH, Yu AL. alpha-Galactosylceramide but not phenyl-glycolipids induced NKT cell anergy and IL-33-mediated myeloid-derived suppressor cell accumulation via upregulation of egr2/3. J Immunol. 2014;192(4):1972–1981. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jovanovic IP, Pejnovic NN, Radosavljevic GD, Pantic JM, Milovanovic MZ, Arsenijevic NN, Lukic ML. Interleukin-33/ST2 axis promotes breast cancer growth and metastases by facilitating intratumoral accumulation of immunosuppressive and innate lymphoid cells. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 2014;134(7):1669–1682. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamada D, Rizvi S, Razumilava N, Bronk SF, Davila JI, Champion MD, Borad MJ, Bezerra JA, Chen X, Gores GJ. IL-33 facilitates oncogene-induced cholangiocarcinoma in mice by an interleukin-6-sensitive mechanism. Hepatology. 2015;61(5):1627–1642. doi: 10.1002/hep.27687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu X, Zhu L, Lu X, Bian H, Wu X, Yang W, Qin Q. IL-33/ST2 pathway contributes to metastasis of human colorectal cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;453(3):486–492. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.09.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu XX, Hu Z, Shen X, Dong LY, Zhou WZ, Hu WH. IL-33 promotes gastric Cancer cell invasion and migration via ST2-ERK1/2 pathway. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60(5):1265–1272. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3463-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen SF, Nieh S, Jao SW, Wu MZ, Liu CL, Chang YC, Lin YS. The paracrine effect of cancer-associated fibroblast-induced interleukin-33 regulates the invasiveness of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J Pathol. 2013;231(2):180–189. doi: 10.1002/path.4226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cacev T, Radosevic S, Krizanac S, Kapitanovic S. Influence of interleukin-8 and interleukin-10 on sporadic colon cancer development and progression. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29(8):1572–1580. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pastorelli L, Garg RR, Hoang SB, Spina L, Mattioli B, Scarpa M, Fiocchi C, Vecchi M, Pizarro TT. Epithelial-derived IL-33 and its receptor ST2 are dysregulated in ulcerative colitis and in experimental Th1/Th2 driven enteritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(17):8017–8022. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912678107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sedhom MA, Pichery M, Murdoch JR, Foligne B, Ortega N, Normand S, Mertz K, Sanmugalingam D, Brault L, Grandjean T, et al. Neutralisation of the interleukin-33/ST2 pathway ameliorates experimental colitis through enhancement of mucosal healing in mice. Gut. 2013;62(12):1714–1723. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mertz KD, Mager LF, Wasmer MH, Thiesler T, Koelzer VH, Ruzzante G, Joller S, Murdoch JR, Brummendorf T, Genitsch V, et al. The IL-33/ST2 pathway contributes to intestinal tumorigenesis in humans and mice. Oncoimmunology. 2016;5(1):e1062966. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1062966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cui G, Qi H, Gundersen MD, Yang H, Christiansen I, Sorbye SW, Goll R, Florholmen J. Dynamics of the IL-33/ST2 network in the progression of human colorectal adenoma to sporadic colorectal cancer. Cancer immunology, immunotherapy : CII. 2015;64(2):181–190. doi: 10.1007/s00262-014-1624-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Y, Davis C, Shah S, Hughes D, Ryan JC, Altomare D, Pena MM. IL-33 promotes growth and liver metastasis of colorectal cancer in mice by remodeling the tumor microenvironment and inducing angiogenesis. Mol Carcinog. 2017;56(1):272–287. doi: 10.1002/mc.22491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kryczek I, Lin Y, Nagarsheth N, Peng D, Zhao L, Zhao E, Vatan L, Szeliga W, Dou Y, Owens S, et al. IL-22(+)CD4(+) T cells promote colorectal cancer stemness via STAT3 transcription factor activation and induction of the methyltransferase DOT1L. Immunity. 2014;40(5):772–784. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tanikawa T, Wilke CM, Kryczek I, Chen GY, Kao J, Nunez G, Zou W. Interleukin-10 ablation promotes tumor development, growth, and metastasis. Cancer Res. 2012;72(2):420–429. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yuan JH, Yang F, Wang F, Ma JZ, Guo YJ, Tao QF, Liu F, Pan W, Wang TT, Zhou CC, et al. A long noncoding RNA activated by TGF-beta promotes the invasion-metastasis cascade in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2014;25(5):666–681. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li Y, Xie J, Xu X, Liu L, Wan Y, Liu Y, Zhu C, Zhu Y. Inducible interleukin 32 (IL-32) exerts extensive antiviral function via selective stimulation of interferon lambda1 (IFN-lambda1) J Biol Chem. 2013;288(29):20927–20941. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.440115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Greenhough A, Smartt HJ, Moore AE, Roberts HR, Williams AC, Paraskeva C, Kaidi A. The COX-2/PGE2 pathway: key roles in the hallmarks of cancer and adaptation to the tumour microenvironment. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30(3):377–386. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang D, Buchanan FG, Wang H, Dey SK, DuBois RN. Prostaglandin E2 enhances intestinal adenoma growth via activation of the Ras-mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade. Cancer Res. 2005;65(5):1822–1829. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baryawno N, Rahbar A, Wolmer-Solberg N, Taher C, Odeberg J, Darabi A, Khan Z, Sveinbjornsson B, FuskevAg OM, Segerstrom L, et al. Detection of human cytomegalovirus in medulloblastomas reveals a potential therapeutic target. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(10):4043–4055. doi: 10.1172/JCI57147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luzina IG, Pickering EM, Kopach P, Kang PH, Lockatell V, Todd NW, Papadimitriou JC, McKenzie AN, Atamas SP. Full-length IL-33 promotes inflammation but not Th2 response in vivo in an ST2-independent fashion. J Immunol. 2012;189(1):403–410. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Inoue H, Yokoyama C, Hara S, Tone Y, Tanabe T. Transcriptional regulation of human prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase-2 gene by lipopolysaccharide and phorbol ester in vascular endothelial cells. Involvement of both nuclear factor for interleukin-6 expression site and cAMP response element. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(42):24965–24971. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.42.24965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim Y, Fischer SM. Transcriptional regulation of cyclooxygenase-2 in mouse skin carcinoma cells. Regulatory role of CCAAT/enhancer-binding proteins in the differential expression of cyclooxygenase-2 in normal and neoplastic tissues. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(42):27686–27694. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.42.27686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamamoto K, Arakawa T, Ueda N, Yamamoto S. Transcriptional roles of nuclear factor kappa B and nuclear factor-interleukin-6 in the tumor necrosis factor alpha-dependent induction of cyclooxygenase-2 in MC3T3-E1 cells. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(52):31315–31320. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.52.31315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mirchandani AS, Salmond RJ, Liew FY. Interleukin-33 and the function of innate lymphoid cells. Trends Immunol. 2012;33(8):389–396. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hu WT, Li MQ, Liu W, Jin LP, Li DJ, Zhu XY. IL-33 enhances proliferation and invasiveness of decidual stromal cells by up-regulation of CCL2/CCR2 via NF-kappaB and ERK1/2 signaling. Mol Hum Reprod. 2014;20(4):358–372. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gat094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fock V, Mairhofer M, Otti GR, Hiden U, Spittler A, Zeisler H, Fiala C, Knofler M, Pollheimer J. Macrophage-derived IL-33 is a critical factor for placental growth. J Immunol. 2013;191(7):3734–3743. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oshio T, Komine M, Tsuda H, Tominaga SI, Saito H, Nakae S, Ohtsuki M. Nuclear expression of IL-33 in epidermal keratinocytes promotes wound healing in mice. J Dermatol Sci. 2017;85(2):106–114. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2016.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Talabot-Ayer D, Martin P, Vesin C, Seemayer CA, Vigne S, Gabay C, Palmer G. Severe neutrophil-dominated inflammation and enhanced myelopoiesis in IL-33-overexpressing CMV/IL33 mice. J Immunol. 2015;194(2):750–760. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen H, Chen Y, Liu H, Que Y, Zhang X, Zheng F. Integrated expression profiles analysis reveals correlations between the IL-33/ST2 Axis and CD8(+) T cells, regulatory T cells, and myeloid-derived suppressor cells in soft tissue sarcoma. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1179. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gao X, Wang X, Yang Q, Zhao X, Wen W, Li G, Lu J, Qin W, Qi Y, Xie F et al: Tumoral expression of IL-33 inhibits tumor growth and modifies the tumor microenvironment through CD8+ T and NK cells. J Immunol 2015, 194(1):438–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Li J, Razumilava N, Gores GJ, Walters S, Mizuochi T, Mourya R, Bessho K, Wang YH, Glaser SS, Shivakumar P et al: Biliary repair and carcinogenesis are mediated by IL-33-dependent cholangiocyte proliferation. J Clin Invest 2014, 124(7):3241–3251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Nieminen R, Lahti A, Jalonen U, Kankaanranta H, Moilanen E. JNK inhibitor SP600125 reduces COX-2 expression by attenuating mRNA in activated murine J774 macrophages. Int Immunopharmacol. 2006;6(6):987–996. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2006.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sun Q, Liu L, Mandal J, Molino A, Stolz D, Tamm M, Lu S, Roth M. PDGF-BB induces PRMT1 expression through ERK1/2 dependent STAT1 activation and regulates remodeling in primary human lung fibroblasts. Cell Signal. 2016;28(4):307–315. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lu J, Reese J, Zhou Y, Hirsch E. Progesterone-induced activation of membrane-bound progesterone receptors in murine macrophage cells. J Endocrinol. 2015;224(2):183–194. doi: 10.1530/JOE-14-0470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Toyota M, Shen L, Ohe-Toyota M, Hamilton SR, Sinicrope FA, Issa JP. Aberrant methylation of the cyclooxygenase 2 CpG island in colorectal tumors. Cancer Res. 2000;60(15):4044–4048. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Coward WR, Feghali-Bostwick CA, Jenkins G, Knox AJ, Pang L. A central role for G9a and EZH2 in the epigenetic silencing of cyclooxygenase-2 in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2014;28(7):3183–3196. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-241760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smith CJ, Zhang Y, Koboldt CM, Muhammad J, Zweifel BS, Shaffer A, Talley JJ, Masferrer JL, Seibert K, Isakson PC. Pharmacological analysis of cyclooxygenase-1 in inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(22):13313–13318. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.13313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sharma S, Xing F, Liu Y, Wu K, Said N, Pochampally R, Shiozawa Y, Lin HK, Balaji KC, Watabe K. Secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine (SPARC) mediates metastatic dormancy of prostate Cancer in bone. J Biol Chem. 2016;291(37):19351–19363. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.737379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang Y, Wang J, Lv Z, Zhao D, Luo M. Cox-2 promotes mesenchymal stem cells differentiation into cardiocytes by activating JNK and ERK pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;480(1):101–105. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.09.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tarnawski AS, Ahluwalia A. Molecular mechanisms of epithelial regeneration and neovascularization during healing of gastric and esophageal ulcers. Curr Med Chem. 2012;19(1):16–27. doi: 10.2174/092986712803414088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Saloustros E, Liu S, Mertz EL, Bhattacharyya N, Starost MF, Salpea P, Nesterova M, Collins M, Leikin S, Stratakis CA. Celecoxib treatment of fibrous dysplasia (FD) in a human FD cell line and FD-like lesions in mice with protein kinase a (PKA) defects. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2017;439:165–174. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2016.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kurtova AV, Xiao J, Mo Q, Pazhanisamy S, Krasnow R, Lerner SP, Chen F, Roh TT, Lay E, Ho PL, et al. Blocking PGE2-induced tumour repopulation abrogates bladder cancer chemoresistance. Nature. 2015;517(7533):209–213. doi: 10.1038/nature14034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yasumaru M, Tsuji S, Tsujii M, Irie T, Komori M, Kimura A, Nishida T, Kakiuchi Y, Kawai N, Murata H, et al. Inhibition of angiotensin II activity enhanced the antitumor effect of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors via insulin-like growth factor I receptor pathway. Cancer Res. 2003;63(20):6726–6734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Swamy MV, Herzog CR, Rao CV. Inhibition of COX-2 in colon cancer cell lines by celecoxib increases the nuclear localization of active p53. Cancer Res. 2003;63(17):5239–5242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zamuner SR, Warrier N, Buret AG, MacNaughton WK, Wallace JL. Cyclooxygenase 2 mediates post-inflammatory colonic secretory and barrier dysfunction. Gut. 2003;52(12):1714–1720. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.12.1714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Alloza I, Baxter A, Chen Q, Matthiesen R, Vandenbroeck K. Celecoxib inhibits interleukin-12 alphabeta and beta2 folding and secretion by a novel COX2-independent mechanism involving chaperones of the endoplasmic reticulum. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69(5):1579–1587. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.020669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cha W, Park SW, Kwon TK, Hah JH, Sung MW. Endoplasmic reticulum stress response as a possible mechanism of cyclooxygenase-2-independent anticancer effect of celecoxib. Anticancer Res. 2014;34(4):1731–1735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang D, Dubois RN. Prostaglandins and cancer. Gut. 2006;55(1):115–122. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.047100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Castellone MD, Teramoto H, Williams BO, Druey KM, Gutkind JS. Prostaglandin E2 promotes colon cancer cell growth through a Gs-axin-beta-catenin signaling axis. Science. 2005;310(5753):1504–1510. doi: 10.1126/science.1116221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sheng H, Shao J, Washington MK, DuBois RN. Prostaglandin E2 increases growth and motility of colorectal carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(21):18075–18081. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009689200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lefrancais E, Roga S, Gautier V, Gonzalez-de-Peredo A, Monsarrat B, Girard JP, Cayrol C. IL-33 is processed into mature bioactive forms by neutrophil elastase and cathepsin G. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(5):1673–1678. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115884109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lefrancais E, Duval A, Mirey E, Roga S, Espinosa E, Cayrol C, Girard JP. Central domain of IL-33 is cleaved by mast cell proteases for potent activation of group-2 innate lymphoid cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(43):15502–15507. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1410700111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yang Y, Andersson P, Hosaka K, Zhang Y, Cao R, Iwamoto H, Yang X, Nakamura M, Wang J, Zhuang R, et al. The PDGF-BB-SOX7 axis-modulated IL-33 in pericytes and stromal cells promotes metastasis through tumour-associated macrophages. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11385. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Akimoto M, Hayashi JI, Nakae S, Saito H, Takenaga K. Interleukin-33 enhances programmed oncosis of ST2L-positive low-metastatic cells in the tumour microenvironment of lung cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7:e2057. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Malik A, Sharma D, Zhu Q, Karki R, Guy CS, Vogel P, Kanneganti TD. IL-33 regulates the IgA-microbiota axis to restrain IL-1alpha-dependent colitis and tumorigenesis. J Clin Invest. 2016;126(12):4469–4481. doi: 10.1172/JCI88625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Characteristics of the colorectal cancer patients analyzed in this study. Table S2. The primers used in this study. Table S3. The output of the Gene Set Enrichment Analysis. (DOC 604 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The data and materials of this study are available from the corresponding authors for reasonable requests.