Abstract

Background

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is associated with mental health problems and functional impairment across many domains. However, how the longitudinal course of ADHD affects later functioning remains unclear.

Aims

To disentangle how ADHD developmental patterns are associated with young adult functioning.

Methods

The Environmental Risk (E-Risk) Longitudinal Twin Study is a population-based cohort of 2,232 twins born in England and Wales in 1994-1995. We assessed ADHD in childhood at ages 5, 7, 10, and 12 and in young adulthood at age 18. We examined three developmental patterns of ADHD from childhood to young adulthood— remitted, persistent, and late–onset ADHD— and compared these groups to one another and to non-ADHD controls on age-18 functioning. We additionally tested whether group differences were due to childhood IQ, childhood conduct disorder, or familial factors shared between twins.

Results

Compared to individuals without ADHD, those with remitted ADHD showed poorer physical health and socioeconomic outcomes in young adulthood. Individuals with persistent or late-onset ADHD showed poorer functioning across all domains including mental health, substance use, psychosocial, physical health, and socioeconomic outcomes. Overall, these associations were not explained by childhood IQ, childhood conduct disorder or shared familial factors.

Conclusions

Long-term associations of childhood ADHD with adverse physical health and socioeconomic outcomes underscore the need for early intervention. Young adult ADHD showed stronger associations with poorer mental health, substance use, and psychosocial outcomes, emphasizing the importance of identifying and treating adults with ADHD.

Declaration of interest

None.

Introduction

Children with ADHD are at increased risk for a wide variety of adverse outcomes in adulthood including mental health problems, substance abuse disorders, and lower educational attainment.1 Adults with ADHD also exhibit poor functioning, such as higher rates of anxiety and depression, divorce, unemployment, and criminal convictions.2,3 A meta-analysis of studies of children with ADHD found about 15% will continue to meet criteria for the disorder in adulthood.4 While many studies have documented poor adult outcomes among children with ADHD, fewer have distinguished between remitted and persistent ADHD groups, thus whether developmental patterns of ADHD have an impact on adult functioning remains unclear. Children with ADHD may fare more poorly in adulthood because childhood problems set them on a course for poorer outcomes in later life. Alternatively, it could be that poor adult functioning is largely due to challenges of coping with current ADHD, with adverse outcomes concentrated amongst those individuals whose ADHD persists into adulthood. Furthermore, recent population-based research has identified a third developmental pattern of ADHD in which adults with ADHD did not meet diagnostic criteria for the disorder in childhood.5–7 These studies found ‘late-onset’ ADHD accounted for 67-90% of adult ADHD cases. However, many questions remain regarding late-onset ADHD, including the role substance use disorders may play in later emerging ADHD symptoms.8 While those with late-onset ADHD state their symptoms interfere with their lives5,7, it is unclear the extent to which functioning may be adversely affected compared to those with childhood-onset ADHD and those without ADHD. The aim of the current study was to disentangle how patterns of ADHD across development, specifically ADHD remission, persistence and late-onset, were associated with young adult functioning. If those with remitted ADHD show poorer functioning in young adulthood, this would suggest that childhood ADHD may exert a long-term effect on functioning. Alternatively, if poor functioning is concentrated among those with young adult ADHD (persistent or late-onset), this would suggest that ADHD may exert a concurrent effect on functioning. By taking a developmental approach to systematically examining outcomes among remitted, persistent and late-onset developmental patterns of ADHD in a longitudinal population-based cohort, we can clarify how childhood and adult ADHD affect young adult functioning to inform the nature and timing of interventions.

Methods

Study cohort

Participants were members of the Environmental Risk (E-Risk) Longitudinal Twin Study, a birth cohort of 2,232 British children drawn from a larger birth register of twins born in England and Wales in 1994-95.9 Full details about the sample are reported elsewhere.10 The E-Risk sample was constructed in 1999-2000 when 1,116 families (93% of those eligible) with same-sex 5-year-old twins participated in home-visit assessments. This sample comprised 56% monozygotic (MZ) and 44% dizygotic (DZ) twin pairs; sex was evenly distributed within zygosity (49% male). Families were recruited to represent the UK population with newborns in the 1990s on the basis of residential location throughout England and Wales and mother’s age; teenaged mothers with twins were over-selected to replace high-risk families who were selectively lost to the register through non-response. Older mothers having twins via assisted reproduction were under-selected to avoid an excess of well-educated older mothers. At follow up, the study sample represented the full range of socioeconomic conditions in the UK, as reflected in the families’ distribution on a neighbourhood-level socioeconomic index (ACORN [A Classification of Residential Neighbourhoods], developed by CACI Inc. for commercial use];11 specifically, E-Risk families’ ACORN distribution matched that of households nation-wide.

Follow-up home visits were conducted when the children were aged 7 (98% participation), 10 (96%), 12 (96%), and 18 years (93%). Home visits at ages 5-12 years included assessments with participants and their mother; we conducted full interviews with participants only at age 18 (n=2,066). There were no differences between those who did and did not take part at age 18 on socioeconomic status when the cohort was initially defined (X2=0.86, p=0.65), age-5 IQ (t=0.98, p=0.33), internalizing or externalizing problems (t=0.40, p=0.69 and t=0.41, p=0.68), or rates of childhood ADHD at ages 5, 7, 10 or 12 (X2=2.12, p=0.71). With parents’ permission, questionnaires were mailed to the children’s teachers, who returned questionnaires for 94% of children at age 5, 93% of those followed up at age 7, 90.1% at age 10, and 83% at age 12. The Joint South London and Maudsley and the Institute of Psychiatry Research Ethics Committee approved each phase of the study. Parents gave informed consent and twins gave assent between 5-12 years and then informed consent at age 18.

Childhood ADHD diagnoses

We ascertained childhood ADHD diagnoses on the basis of mother and teacher reports of 18 symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity derived from DSM-IV diagnostic criteria and the Rutter Child Scales.12 Participants had to have six or more symptoms reported by mothers or teachers in the past 6 months, and the other informant must have endorsed at least two symptoms. We considered participants to have a diagnosis of childhood ADHD if they met criteria at age 5, 7, 10 or 12. At age 5, 6.8% (n=131) of participants met criteria for ADHD, 5.4% (n=102) at age 7, 3.4% (n=65) at age 10 and 3.4% (n=64) at age 12. In childhood, 0.8% of the study population (n=17) was taking ADHD medication based on maternal report; rates of medication use were similar to those in the UK overall13.

Age-18 ADHD diagnosis

We ascertained ADHD diagnosis at age 18 based on private structured interviews with participants regarding 18 symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity according to DSM-5 criteria.5 Participants had to endorse five or more inattentive and/or five or more hyperactivity–impulsivity symptoms to be diagnosed; we also required that symptoms interfere with individual’s life at “home, or with family and friends” and at “school or work”, thereby meeting impairment and pervasiveness criteria. The requirement of symptom onset prior to age 12 was met if parents or teachers reported more than two ADHD symptoms at any childhood assessment. A total of 8.1% of participants (n=166) met criteria for ADHD at age 18. Analyses were restricted to those individuals with information on childhood and young adult ADHD (N = 2,040).

Participants additionally nominated two people who knew them well to provide information about the participant on questionnaires, including eight items related to ADHD. In total, 99.3% of participants had information from co-informants, including 81.1% from both a parent and co-twin, 17.2% from a co-twin only and 1.7% from a parent only.

Remitted, persistent and late-onset ADHD groups

We identified three groups of individuals with ADHD across childhood and young adulthood: 9.5% of participants (n=193) showed remitted ADHD (met diagnostic criteria in childhood but not at age 18), 2.6% (n=54) persistent ADHD (met diagnostic criteria in childhood and age 18), and 5.5% (n=112) ‘late-onset’ ADHD (did not meet diagnostic criteria in childhood but did at age 18). At age 18, 0.6% (n=13) of the study population reported taking ADHD medication, 15.4% (n=8) of those with persistent ADHD and 4.5% (n=5) of those with late-onset ADHD. A total of 82.4% participants (n=1,681) did not meet criteria for ADHD in childhood or adulthood.

Young adult outcomes

Mental health

Participants were interviewed for the presence of depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and conduct disorder, according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) criteria.14 Assessments were conducted in face-to-face interviews using the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS),15 with the exception of conduct disorder which was included in a computer-assisted module. Suicide attempt was defined as any self-reported suicide attempt between ages 12 and 18 years. Self-harm was defined as positive response to the question “have you ever tried to hurt yourself to cope with emotional stress or pain?”.

Substance use

Alcohol and cannabis dependence over the previous 12 months were evaluated with DSM-IV criteria during face-to-face interviews using the DIS.15 Other illicit substance use included non-prescription use of stimulants, sedatives, cocaine/crack, painkillers, street opiates, club drugs, hallucinogens, inhalants, and “other drugs”.

Psychosocial outcomes

Life satisfaction was assessed by the Satisfaction With Life Scale16 and social isolation via the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support.17 Problematic technology use was assessed using the Compulsive Internet Use Scale,18 adapted to include use of the internet, email, social networking sites and tools, mobile phones and text messaging to update the measure to reflect the current nature of online activities and communication.

Physical health

Body Mass Index (BMI) was calculated by dividing weight in kilograms by height in metres squared; obesity was defined as a BMI greater than or equal to 30. Daily cigarette smoking was assessed by asking the participant if they had ever smoked a cigarette, followed by if and when they began smoking every day; current daily smokers were participants who endorsed daily smoking within the past year. Participants self-reported whether they had visited an Accident and Emergency department in the past year.

Socioeconomic outcomes

Low educational attainment was assessed by whether participants did not obtain or scored low (grade D-G) on their General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE). GCSEs are a standardised examination taken at the end of compulsory education at age 16 years. Individuals were considered to be not in education, employment, or training (NEET) if they reported that they were neither studying, nor working in paid employment, nor pursuing a vocational qualification or apprenticeship training (not due to being on holiday or being a parent). Criminal cautions/convictions were assessed through the UK Police National Computer records searched by the UK Ministry of Justice, and include participants cautioned or convicted in the UK through age 19.

Childhood confounders

All regression models adjusted for gender and childhood socioeconomic status (SES). Childhood SES reflected a composite of parental income, education and occupation. Individuals with ADHD are more likely to have lower IQ and comorbid conduct disorder,12,19 and it is possible that these factors, rather than ADHD, lead to poor outcomes. Childhood IQ was assessed at age 5 using two subtests of the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence (WPPSI Revised).20 Childhood conduct disorder was assessed using DSM-IV criteria with the Achenbach family of instruments and additional items covering aggressive and nonaggressive conduct problems, deceitfulness or theft, and rule violations as reported by mothers and teachers from ages 5 to 12.21

Statistical analyses

To understand how different developmental patterns of ADHD were associated with young adult functioning, we compared groups with remitted, persistent and late-onset ADHD by age 18 to individuals who never had ADHD. We estimated effect sizes and significance of differences between groups using logistic and linear regressions, adjusting for gender and childhood SES. We further adjusted for childhood conduct disorder and IQ in models predicting young adult outcomes. To assess whether findings could be artefacts due to self-report of ADHD symptoms at age 18, we also conducted sensitivity analyses replacing ADHD diagnosis based on self-report with co-informant rated ADHD symptoms at age 18. All of the above analyses adjusted for the non-independence of twin observations by using the sandwich variance estimator in Stata version 14.22 Aspects of the home environment and genetic makeup influence both the risk for ADHD and for poor outcomes in young adulthood, therefore we compared functioning between co-twins discordant for ADHD. Using logistic regression, MZ twins with ADHD (either in childhood and/or young adulthood, N=91 twin pairs, 55.5% male) were compared to their co-twin who never had ADHD.

Results

Young adult ADHD appeared to be a more salient risk factor for poor mental health than childhood ADHD per se. Overall, individuals with ADHD only in childhood (remitted ADHD) did not have poorer mental health at age 18 compared to those who never had ADHD, with the exception of conduct disorder (Table 1). However, those with persistent and late-onset ADHD had more depression, anxiety, conduct disorder, and suicide/self-harm compared to those who never had ADHD. Persistent and late-onset ADHD groups appeared to be equally impaired for mental health as indicated by comparable effect sizes for these groups.

Table 1.

Mental health and functional outcomes at age 18 years comparing remitted, persistent, and late-onset ADHD groups with those who never had ADHD

| Young adult outcomes | Never ADHD | Remitted ADHD | Persistent ADHD | Late-onset ADHD | Persistent vs remitted | Persistent vs late-onset | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=1681 | N=193 | N=54 | N=112 | ||||||

| Mental health | N (%) | N (%) | OR, p value | N (%) | OR, p value | N (%) | OR, p value | OR, p value | OR, p value |

| Depression | 300 (17.9) | 41 (21.4) | 1.40, 0.096 | 19 (35.2) | 2.73, 0.002 | 48 (42.9) | 3.41, <0.001 | 2.00, 0.049 | 0.75, 0.451 |

| Anxiety | 108 (6.4) | 11 (5.8) | 1.18, 0.647 | 13 (24.1) | 6.07, <0.001 | 18 (16.1) | 2.91, <0.001 | 5.35, 0.001 | 1.80, 0.209 |

| Conduct disorder | 200 (11.9) | 45 (23.6) | 1.53, 0.033 | 20 (38.5) | 3.49, <0.001 | 39 (35.1) | 4.16, <0.001 | 2.22, 0.031 | 0.93, 0.863 |

| Suicide/self-harm | 218 (13.0) | 25 (13.0) | 1.09, 0.711 | 15 (27.8) | 2.88, 0.003 | 30 (26.8) | 2.37, <0.001 | 2.64, 0.014 | 1.36, 0.454 |

| Substance use | N (%) | N (%) | OR, p value | N (%) | OR, p value | N (%) | OR, p value | OR, p value | OR, p value |

| Cannabis dependence | 54 (3.2) | 11 (5.7) | 1.11, 0.780 | 8 (14.8) | 3.91, 0.006 | 13 (11.6) | 3.96, <0.001 | 3.16, 0.020 | 1.21, 0.745 |

| Illicit drug use | 260 (15.5) | 42 (21.8) | 1.18, 0.422 | 16 (29.6) | 1.94, 0.052 | 34 (30.4) | 2.35, <0.001 | 1.62, 0.171 | 0.92, 0.840 |

| Alcohol dependence | 182 (10.8) | 32 (16.6) | 1.47, 0.074 | 7 (13.0) | 1.12, 0.796 | 35 (31.5) | 3.88, <0.001 | 0.78, 0.601 | 0.30, 0.014 |

| Psychosocial | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | β, p value | Mean (SD) | β, p value | Mean (SD) | β, p value | β, p value | β, p value |

| Life satisfaction | 3.92 (0.7) | 3.75 (0.7) | -0.05, 0.034 | 3.48 (0.9) | -0.09, 0.004 | 3.44 (0.8) | -0.15, <0.001 | -0.15, 0.064 | 0.01, 0.913 |

| Social isolation | 3.11 (4.2) | 3.73 (4.6) | 0.01, 0.626 | 4.45 (5.2) | 0.04, 0.189 | 4.41 (4.7) | 0.07, 0.007 | 0.07, 0.346 | 0.02, 0.797 |

| Problematic technology use | 4.18 (3.6) | 4.80 (4.2) | 0.05, 0.066 | 7.77 (5.4) | 0.16, <0.001 | 8.01 (4.7) | 0.23, <0.001 | 0.31, 0.001 | 0.03, 0.792 |

| Physical health | N (%) | N (%) | OR, p value | N (%) | OR, p value | N (%) | OR, p value | OR, p value | OR, p value |

| Obesity | 139 (8.4) | 24 (12.7) | 1.74, 0.040 | 9 (17.0) | 2.35, 0.046 | 13 (11.8) | 1.34, 0.353 | 1.38, 0.519 | 1.58, 0.342 |

| Daily cigarette smoking | 316 (18.8) | 70 (36.3) | 2.06, <0.001 | 20 (37.0) | 2.29, 0.005 | 44 (39.6) | 2.60, <0.001 | 1.09, 0.779 | 0.87, 0.683 |

| Emergency department visit | 321 (19.1) | 47 (24.4) | 1.22, 0.287 | 17 (31.5) | 1.81, 0.044 | 34 (30.4) | 1.79, 0.006 | 1.51, 0.223 | 0.99, 0.987 |

| Socioeconomic | N (%) | N (%) | OR, p value | N (%) | OR, p value | N (%) | OR, p value | OR, p value | OR, p value |

| Low educational attainment | 263 (15.7) | 96 (50.3) | 4.73, <0.001 | 35 (64.8) | 10.80, <0.001 | 37 (33.0) | 2.43, <0.001 | 2.07, 0.032 | 4.23, <0.001 |

| NEET status | 151 (9.0) | 43 (22.3) | 2.57, <0.001 | 16 (29.6) | 4.11, <0.001 | 20 (17.9) | 1.91, 0.025 | 1.60, 0.221 | 1.89, 0.123 |

| Criminal cautions/convictions | 133 (7.9) | 50 (25.9) | 2.59, <0.001 | 13 (25.0) | 2.70, 0.003 | 17 (15.3) | 1.97, 0.031 | 1.08, 0.832 | 1.22, 0.647 |

Statistical comparisons and effect sizes adjusted for gender and parental socioeconomic status. Statistically significant findings are presented in bold. OR=odds ratio, β=standardized beta, NEET = not in education, employment or training. Groups with childhood ADHD were more likely to be male (remitted 72.5%, persistent 66.7%), compared with the never ADHD group (44.2% male, both p<0.001); there was no significant difference in the gender distribution between the never ADHD and late-onset ADHD groups (late-onset 44.6% male). All ADHD groups were more likely to have parents with lower SES than those who never had ADHD (remitted 48.7% p<0.001, persistent= 44.4% p= 0.03, late-onset 42.0 p=0.01, compared with never ADHD 30.5%).

Similarly, those with persistent and late-onset ADHD showed elevated risk for cannabis dependence and illicit drug use at age 18 compared to individuals who never had ADHD, while those with remitted ADHD did not. Again, effect sizes for the late-onset group were similar to those of the persistent group. Only the late-onset ADHD group showed increased alcohol dependence compared to those without ADHD, while the persistent and remitted ADHD groups did not.

Psychosocial outcomes showed a similar pattern of findings, in which those with remitted ADHD had minimal impairment compared to those who never had ADHD, while persistent and late-onset ADHD groups showed poorer functioning. The remitted ADHD group showed only lower life satisfaction compared to those without ADHD, while the persistent group had lower life satisfaction and more problematic technology use. The late-onset ADHD group showed poorer outcomes across each psychosocial outcome compared to those who never had ADHD, of a similar effect size as the persistent ADHD group.

The pattern of findings was mixed for physical health outcomes. Both remitted and persistent groups showed greater obesity risk compared to those who never had ADHD while the late-onset group did not, suggesting a long-term effect of childhood ADHD. The risk of daily cigarette smoking was elevated in all ADHD groups, with similar effect sizes across all groups. For visits to emergency department, however, those with remitted ADHD showed no increased risk while both the persistent and late-onset groups did.

All ADHD groups showed poorer socioeconomic outcomes at age 18. Risk for low educational attainment was further elevated among individuals with persistent ADHD compared to those whose ADHD remitted and those with late-onset ADHD. Remitted, persistent and late-onset ADHD groups also showed higher risk for being NEET and for criminal cautions/convictions, suggesting the presence of both long-term and concurrent associations of ADHD with these outcomes.

Adjusting for childhood IQ and conduct disorder

Overall, further adjustment for childhood IQ and conduct disorder did not account for poorer age-18 functioning among individuals with remitted, persistent or late-onset ADHD (Table 2). Exceptions to this were concentrated among physical health and socioeconomic outcomes: for example, after controlling for childhood IQ and conduct disorder the risk of daily cigarette smoking was reduced, especially among the persistent ADHD group, and the risk of criminal cautions/convictions was lowered, to non-significance among the persistent and late-onset ADHD groups.

Table 2.

Mental health and functional outcomes at age 18 years among participants with remitted, persistent and late-onset ADHD compared to those who never had ADHD, further adjusting for childhood IQ and conduct disorder

| Remitted ADHD | Persistent ADHD | Late-onset ADHD | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young adult outcome | ||||||

| Mental health | OR (95% CI) | p value | OR (95% CI) | p value | OR (95% CI) | p value |

| Depression | 1.27 (0.84, 1.92) | 0.265 | 2.68 (1.40, 5.13) | 0.003 | 3.37 (2.24, 5.06) | <0.001 |

| Anxiety | 1.10 (0.50, 2.41) | 0.811 | 6.47 (3.09,13.53) | <0.001 | 2.95 (1.72, 5.04) | <0.001 |

| Conduct disorder | 1.03 (0.66, 1.58) | 0.911 | 2.15 (1.03, 4.49) | 0.041 | 3.48 (2.20, 5.49) | <0.001 |

| Suicide/self-harm | 0.92 (0.58, 1.48) | 0.740 | 2.38 (1.13, 5.00) | 0.023 | 2.18 (1.39, 3.43) | 0.001 |

| Substance use | OR (95% CI) | p value | OR (95% CI) | p value | OR (95% CI) | p value |

| Cannabis dependence | 0.82 (0.41, 1.65) | 0.576 | 2.65 (1.05, 6.72) | 0.040 | 3.02 (1.46, 6.25) | 0.003 |

| Illicit drug use | 1.01 (0.66, 1.55) | 0.971 | 1.63 (0.82, 3.25) | 0.162 | 2.13 (1.32, 3.43) | 0.002 |

| Alcohol dependence | 1.34 (0.85, 2.12) | 0.206 | 1.01 (0.39, 2.61) | 0.988 | 3.70 (2.38, 5.76) | <0.001 |

| Psychosocial | β (95% CI) | p value | β (95% CI) | p value | β (95% CI) | p value |

| Life satisfaction | -0.03 (-0.07, 0.02) | 0.251 | -0.08 (-0.14, -0.01) | 0.021 | -0.14 (-0.19, -0.08) | <0.001 |

| Social isolation | -0.01 (-0.07, 0.04) | 0.653 | 0.03 (-0.04, 0.09) | 0.413 | 0.06 (0.01, 0.11) | 0.025 |

| Problematic technology use | 0.03 (-0.03, 0.08) | 0.337 | 0.14 (0.07, 0.21) | <0.001 | 0.23 (0.17, 0.28) | <0.001 |

| Physical health | OR (95% CI) | p value | OR (95% CI) | p value | OR (95% CI) | p value |

| Obesity | 1.63 (0.91, 2.93) | 0.098 | 2.18 (0.91, 5.23) | 0.080 | 1.19 (0.63, 2.26) | 0.597 |

| Daily cigarette smoking | 1.56 (1.07, 2.28) | 0.021 | 1.53 (0.79, 2.95) | 0.203 | 2.24 (1.45, 3.47) | <0.001 |

| Emergency department visit | 1.10 (0.75, 1.63) | 0.616 | 1.55 (0.84, 2.87) | 0.164 | 1.69 (1.10, 2.58) | 0.016 |

| Socioeconomic | OR (95% CI) | p value | OR (95% CI) | p value | OR (95% CI) | p value |

| Low educational attainment | 3.39 (2.27, 5.07) | <0.001 | 5.84 (3.12, 10.91) | <0.001 | 1.98 (1.20, 3.25) | 0.007 |

| NEET status | 2.05 (1.32, 3.18) | 0.001 | 2.76 (1.33, 5.73) | 0.006 | 1.57 (0.87, 2.86) | 0.136 |

| Criminal cautions/convictions | 1.65 (1.08, 2.50) | 0.020 | 1.51 (0.75, 3.06) | 0.250 | 1.42 (0.74, 2.73) | 0.289 |

Comparison group is those who never had ADHD. Analyses adjusted for gender and parental SES. Statistically significant results are presented in bold. OR=odds ratio, β=standardized beta, CI=confidence interval, NEET = not in education, employment or training.

Accounting for familial and genetic influences

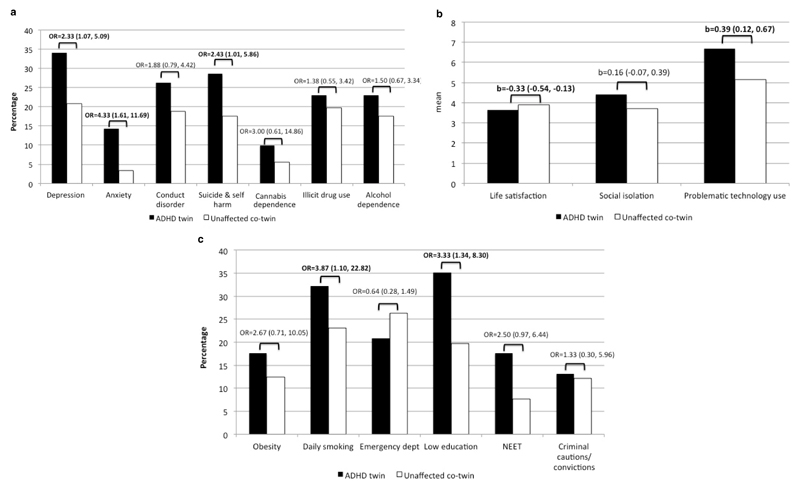

Compared with their unaffected co-twin, twins with ADHD in childhood or adulthood were more likely to experience young adult depression, anxiety, suicide/self-harm, daily smoking, low educational attainment, lower life satisfaction and more problematic technology use (Figure 1). Therefore, these poor outcomes among participants with ADHD were not due to risk factors shared with their MZ co-twin, including genetic or family environmental factors, such as parental psychopathology or chaotic home environment.

Figure 1. Discordant monozygotic twin analyses (N=91 twin pairs) comparing outcomes among twins with ADHD versus their unaffected co-twin, with significant differences in bold.

Panel a. Mental health and substance use

Panel b. Psychosocial functioning

Panel c. Physical health and socioeconomic outcomes

Sensitivity analyses using co-informant report of ADHD symptoms at age 18

Results were unchanged for all outcomes using co-informant-rated ADHD symptoms. For mental health, substance use, and psychosocial outcomes, co-informant-rated symptoms in young adulthood were a more salient risk factor compared with childhood ADHD diagnosis. Both co-informant-rated ADHD symptoms and childhood ADHD were associated with risk of daily cigarette smoking, low educational attainment and NEET status, mirroring results using self-report. Additionally, as with self-reported ADHD, co-informant-reported ADHD symptoms in young adulthood were not associated with increased obesity risk.

Supplemental analyses

In supplemental analyses, we ruled out the possibility that the associations between young adult ADHD and age-18 functioning were due to individuals with persistent ADHD having more frequent diagnoses of ADHD across childhood (Supplemental table 1), or to sub-threshold childhood ADHD symptoms among those with late-onset ADHD (Supplemental table 2). Additionally because recent research has suggested late-onset ADHD may be accounted for by substance use disorders,8 we examined findings excluding participants with alcohol dependence, marijuana dependence or illicit drug use (Supplemental table 3); overall results were similar, however daily cigarette smoking and visits to the emergency room were no longer significantly elevated among both the persistent and late-onset ADHD groups.

Discussion

Children and adults with ADHD are more likely to experience a range of negative outcomes in adulthood, which are distressing for the affected individual, concerning for family members, and costly for society.23 Poor mental health and functioning in the transition to adulthood can have far-reaching consequences into later life: young adult outcomes such as depression, low educational attainment, smoking and obesity may have a major impact on quality of life into midlife and beyond, and can even lead to premature mortality. In the current study we found that the developmental pattern of ADHD from childhood into young adulthood influences functional outcomes, and this effect varies by outcome domain. Those with remitted ADHD showed poor socioeconomic and physical health outcomes in young adulthood, suggesting that childhood ADHD has a long-term association with these domains, even if an individual no longer meets criteria for the disorder. Conversely, those with young adult ADHD (both persistent and late-onset) showed adverse socioeconomic and physical health outcomes, as well as poorer mental health, substance use, and psychosocial outcomes.

Long-term effects of childhood ADHD

Childhood ADHD appears to maintain a long-term effect on later functioning for those outcomes more overtly cumulative in nature. For example, educational attainment builds on past performance, and it may be difficult to rebound from prior school failures even if ADHD symptoms abate. Our finding of lower educational attainment among those with remitted and persistent ADHD is consistent with another population-based study that showed participants with ‘high’ as well as ‘declining’ inattention symptom trajectories both had lower rates of graduating high school compared to those with consistently ‘low’ symptom levels.24

Childhood ADHD was also associated with a more than 70% increased risk for obesity at age 18, even when the disorder remitted by young adulthood. Studies have found children with ADHD are more likely to be obese compared to those without.25 One possibility for the long-term effect is that higher BMI, once established in childhood, is relatively intractable such that later changes to ADHD symptom levels may not affect BMI. Additionally, recent research has found overlap in genetic risk for ADHD and obesity;26 indeed our twin analyses did not show significant differences in obesity between ADHD-discordant MZ twins, so we cannot rule out that shared genetics may increase risk both for ADHD and obesity.

Concurrent effects of young adult ADHD

While remission of ADHD appeared to be associated with a corresponding normalisation of risk for most mental health problems, substance use and psychosocial problems, ADHD in young adulthood was associated with poor functioning across each of these domains. More proximal pathways may link young adult ADHD with risk for other mental health problems, for example individuals with young adult ADHD may have more interpersonal problems, failures at school, or frustrations at work, which could lead to depression or anxiety. Additionally, the outcomes most affected by young adult ADHD may be those that more explicitly tap into current functioning, for example problematic technology use or daily cigarette smoking may reflect ways in which individuals cope with their ADHD symptoms.

That individuals with persistent ADHD fared more poorly than those who remit is consistent with recent studies in referred samples of ADHD children and adolescents, which indicate that those with persistent ADHD have poorer mental health, higher risk of self-injurious behaviour and more substance use disorders.27–29 We have extended these findings in a population-based cohort and showed that poorer functioning among those with persistent ADHD was not accounted for by childhood lower IQ or conduct disorder, nor was it because those with persistent ADHD had more frequent ADHD diagnoses across childhood compared to those who remitted. Additionally, discordant twin analyses revealed that these associations were not due to childhood family environmental risk factors (e.g. parental psychology) or genes that increase risk for ADHD and other disorders, as despite sharing both a home environment and 100% of their genes, the twin with ADHD had significantly poorer mental health and psychosocial functioning than the twin without.

We have also extended prior research to show that young adult ADHD was associated with poor functioning not only for those whose ADHD persisted from childhood, but also for those with late-onset ADHD. Functioning in the late-onset ADHD group was as impaired as the persistent group across several domains: for example over a quarter of both groups had attempted suicide or engaged in self-harm behaviour. Poor outcomes were not attributable to the late-onset ADHD group in having lower SES, IQ, or more conduct disorder in childhood. Additionally our supplemental analyses showed that poorer functioning in young adulthood in this group was not explained by subthreshold ADHD symptoms in childhood among those who later met criteria for late-onset ADHD. Furthermore, functioning was also poorer amongst those with late-onset ADHD who did not have a comorbid substance use problem. Exceptions to this were daily cigarette smoking and emergency room visits, for which risk was no longer significantly elevated compared to controls among the persistent and late-onset ADHD groups after excluding those with substance misuse, suggesting perhaps a specific pathway between young adult ADHD and these outcomes operating through substance use problems. While much about late-onset ADHD remains to be explored, our finding that individuals with late-onset ADHD were as impaired as those with persistent ADHD in many domains in young adulthood points to the need for appropriate clinical attention for these individuals.

Limitations

The current study has several strengths, including multiple assessments of ADHD across childhood and into young adulthood in a population-based cohort with an over 90% retention rate. However, we need to consider our findings in light of some limitations. While the temporal ordering of childhood ADHD and age-18 outcomes is clear, we were more limited in the causal inferences we can draw between young adult ADHD and age-18 outcomes as they were assessed concurrently. Therefore, it is possible, for example, that lower educational attainment contributed to the persistence of ADHD, rather than persistent ADHD affecting educational attainment. Additionally, we derived ADHD diagnoses at age 18 from self-reported information only, rather than parental report. Concerns have been raised about individual’s ability to report on their own ADHD symptoms. However, prior work in this cohort found co-informant report of ADHD symptoms at age 18 to corroborate self-reports: those with self-reported late-onset ADHD have significantly more co-informant-rated ADHD symptoms than those without ADHD, and those with persistent ADHD are rated by co-informants as having more ADHD symptoms at age 18 than those with remitted ADHD.5 Furthermore, recent research using a self-reported ADHD symptom scale found high specificity and positive predictive value compared with a diagnostic interview administered by clinicians.30 Additionally, in sensitivity analyses our results regarding the salience of childhood versus young adult ADHD for later functioning did not change using co-informant-rated ADHD symptoms at age 18. The E-Risk sample does not include a follow-up assessment between the ages of 12 and 18, therefore we cannot determine exactly the age at which ADHD remitted or emerged if it did so in adolescence. Our sample comprised twins, thus results may not generalize to singletons; however, as reported previously, the prevalence of ADHD at each age in our cohort is well within ranges estimated in other samples.31 In addition, childhood ADHD was associated with previously identified risk factors,32 and our rate of ADHD persistence is similar to that found by a meta-analysis.4 Finally, we have followed participants only to the beginning of young adulthood and future research is needed to parse the long-term effects of childhood versus concurrent ADHD in later life, which can include additional outcomes such as longer-term employment issues, parenting behaviours, and chronic disease.

Conclusions and implications

If ADHD resolves, children with ADHD are not destined to experience negative sequelae across all domains of functioning in young adulthood. However, the long-term effect of childhood ADHD on physical health and socioeconomic outcomes underscores the need for early intervention. For mental health, substance use, and psychosocial outcomes, young adult ADHD showed a stronger association with functioning, emphasizing the importance of identifying and treating young adult ADHD. The presence of significant impairments in the late-onset ADHD group suggests that individuals with this developmental pattern, who may not be captured with the current classification systems, require attention and possibly treatment.

Supplementary Material

Table 3.

Mental health and functional outcomes at age 18 years, simultaneously adjusting for young adult co-informant-rated ADHD symptoms and childhood ADHD diagnosis

| Mental health | OR | 95% CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | |||

| Co-informant-rated ADHD symptoms | 1.22 | (1.13, 1.31) | <0.001 |

| Childhood ADHD diagnosis | 1.25 | (0.86, 1.82) | 0.239 |

| Anxiety | |||

| Co-informant-rated ADHD symptoms | 1.12 | (1.01, 1.24) | 0.028 |

| Childhood ADHD diagnosis | 1.53 | (0.88, 2.64) | 0.130 |

| Conduct disorder | |||

| Co-informant-rated ADHD symptoms | 1.30 | (1.20, 1.40) | <0.001 |

| Childhood ADHD diagnosis | 1.21 | (0.83, 1.78) | 0.323 |

| Suicide/self-harm | |||

| Co-informant-rated ADHD symptoms | 1.24 | (1.15, 1.35) | <0.001 |

| Childhood ADHD diagnosis | 1.03 | (0.67, 1.59) | 0.890 |

| Substance use | OR | 95% CI | p value |

| Cannabis dependence | |||

| Co-informant-rated ADHD symptoms | 1.32 | (1.19, 1.48) | <0.001 |

| Childhood ADHD diagnosis | 0.94 | (0.45, 1.97) | 0.870 |

| Illicit drug use | |||

| Co-informant-rated ADHD symptoms | 1.24 | (1.15, 1.35) | <0.001 |

| Childhood ADHD diagnosis | 0.95 | (0.63, 1.42) | 0.785 |

| Alcohol dependence | |||

| Co-informant-rated ADHD symptoms | 1.18 | (1.09, 1.27) | <0.001 |

| Childhood ADHD diagnosis | 1.03 | (0.67, 1.58) | 0.898 |

| Psychosocial | b | 95% CI | p value |

| Life satisfaction | |||

| Co-informant-rated ADHD symptoms | -0.09 | (-0.13, -0.06) | <0.001 |

| Childhood ADHD diagnosis | -0.07 | (-0.18, 0.04) | 0.234 |

| Social Isolation | |||

| Co-informant-rated ADHD symptoms | 0.33 | (0.16, 0.50) | <0.001 |

| Childhood ADHD diagnosis | 0.06 | (-0.66, 0.76) | 0.871 |

| Problematic technology use | |||

| Co-informant-rated ADHD symptoms | 0.34 | (0.07, 1.47) | <0.001 |

| Childhood ADHD diagnosis | 0.77 | (-0.68, 0.08) | 0.030 |

| Physical health | OR | 95% CI | p value |

| Obesity | |||

| Co-informant-rated ADHD symptoms | 1.07 | (0.96, 1.19) | 0.215 |

| Childhood ADHD diagnosis | 1.80 | (1.13, 2.88) | 0.013 |

| Daily cigarette smoking | |||

| Co-informant-rated ADHD symptoms | 1.35 | (1.25, 1.46) | <0.001 |

| Childhood ADHD diagnosis | 1.44 | (1.02, 2.03) | 0.039 |

| Emergency department visit | |||

| Co-informant-rated ADHD symptoms | 1.11 | (1.02, 1.19) | 0.012 |

| Childhood ADHD diagnosis | 1.16 | (0.82, 1.64) | 0.400 |

| Socioeconomic | OR | 95% CI | p value |

| Low educational attainment | |||

| Co-informant-rated ADHD symptoms | 1.20 | (1.10, 1.30) | <0.001 |

| Childhood ADHD diagnosis | 4.65 | (3.28, 6.60) | <0.001 |

| NEET status | |||

| Co-informant-rated ADHD symptoms | 1.23 | (1.12, 1.35) | <0.001 |

| Childhood ADHD diagnosis | 2.39 | (1.60, 3.57) | <0.001 |

| Criminal cautions/convictions | |||

| Co-informant-rated ADHD symptoms | 1.20 | (1.09, 1.31) | <0.001 |

| Childhood ADHD diagnosis | 1.97 | (1.34, 2.90) | 0.010 |

Statistical analyses adjusted for gender and parental socioeconomic status. OR=odds ratio, b=regression coefficient, CI=confidence interval, NEET = not in education, employment or training.

Acknowledgements

The E-Risk Study is funded by the Medical Research Council (UKMRC grant G1002190). Additional support was provided by National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (grant HD077482) and by the Jacobs Foundation. Jessica Agnew-Blais is an MRC Skills Development Fellow. Louise Arseneault is the ESRC Mental Health Leadership Fellow. The authors are grateful to the Study members and their families for their participation. Our thanks to the Avielle Foundation, CACI, Inc., the UK Ministry of Justice, and to members of the E-Risk team for their dedication, hard work, and insights.

We are grateful to the study mothers and fathers, the twins, and the twins' teachers for their participation. Our thanks to Avshalom Caspi, PhD (Duke University and King’s College London) and Sir Michael Rutter, MD PhD (King’s College London) for their involvement in establishing the E-Risk cohort. No compensation was received for this involvement.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Erskine HE, Noman RE, Ferrari AJ, et al. Long-term outcomes of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and conduct disorder: A systematic review and meta-analyses. J Am Acad Child Adol Psychiatry. 2016;55(10):841–850. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kessler RC, Adler LA, Barkley R, et al. Patterns and predictors of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder persistence into adulthood: Results from the national comorbidity survey replication. Biol Psychiatr. 2005;57(11):1442–1451. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lichtenstein P, Halldner L, Zetterqvist K, et al. Medication for attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder and criminality. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(21):2006–2014. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1203241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Faraone SV, Biederman J. What is the prevalence of adult ADHD? Results from a population screen of 966 adults. J Atten Disord. 2005;9(2):384–391. doi: 10.1177/1087054705281478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agnew-Blais JC, Polanczyk GV, Danese A, Wertz J, Moffitt TE, Arseneault L. Persistence, remission and emergence of ADHD in young adulthood: Results from a longitudinal, prospective population-based cohort. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(7):713–720. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.0465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caye A, Rocha TBM, Anselmi L, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder trajectories from childhood to young adulthood: Evidence from a birth cohort supporting a late-onset syndrome. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(7):705–712. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.0383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moffitt TE, Houts R, Asherson P, et al. Is adult ADHD a childhood-onset neurodevelopmental disorder? Evidence from a four-decade longitudinal cohort study. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(10):976–977. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.14101266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sibley MH, Rohde LA, Swanson JM, et al. Late-onset ADHD reconsidered with comprehensive repeated assessments between ages 10 and 25. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(2):140–149. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.17030298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trouton A, Spinath F, Plomin R. Twins Early Development Study (TEDS): a multivariate, longitudinal genetic investigation of language, cognition and behavior problems in childhood. Twin Res. 2002;5(5):444–448. doi: 10.1375/136905202320906255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moffitt TE, E-Risk Study Team Teen-aged mothers in contemporary Britain. J Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;43(6):727–742. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Odgers C, Caspi A, Russell M, Sampson R, Arseneault L, Moffitt TE. Supportive parenting mediates neighborhood socioeconomic disparities in children's antisocial behavior from ages 5 to 12. Devel Psychopathol. 2012;24(3):705–721. doi: 10.1017/S0954579412000326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuntsi J, Eley TC, Taylor A, et al. Co-occurrence of ADHD and low IQ has genetic origins. Am J Med Genet Part B (Neuropsychiatric Genetics) 2004;124B:41–47. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.20076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCarthy S, Wilton L, Murray ML, Hodgkins P, Asherson P, Wong IC. The epidemiology of pharmacologically treated attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children, adolescents and adults in UK primary care. BMC Pediatrics. 2012;12(1):78. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-12-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robins L, Cottler L, Bucholz K, Compton W. Diagnostic Interview Schedule for DSM-IV. St. Louis, MP: Washington University School of Medicine; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. J Pers Assess. 1985;49:71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zimet G, Dahlem N, Zimet S, Farley G. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1988;52:30–41. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meerkerk GJ, Van Den Eijnden RJ, Vermulst AA, Garretsen HF. The compulsive internet use scale (CIUS): some psychometric properties. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2009;12(1):1–6. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2008.0181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Biederman J, Newcorn J, Sprich S. Comorbidity of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder with conduct, depressive, anxiety, and other disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:564–577. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.5.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wechsler D. Wechsler preschool and primary scale of intelligence-- revised. London, England: The Psychological Corporation; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4-18 and 1991 Profile. Burlington: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 22.STATA [computer program]. Version 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Birnbaum HG, Kessler RC, Lowe SW, et al. Costs of attention deficit–hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in the US: excess costs of persons with ADHD and their family members in 2000. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;21(2):195–205. doi: 10.1185/030079904X20303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pingault JB, Tremblay RE, Vitaro F, et al. Childhood trajectories of inattention and hyperactivity and prediction of educational attainment in early adulthood: a 16-year longitudinal population-based study. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:1164–1170. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10121732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cortese S, Moreira-Maia CR, St Fleur D, Morcillo-Peñalver C, Rohde LA, Faraone SV. Association between ADHD and obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(1):34–43. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15020266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Demontis D, et al. Discovery of the first genome-wide significant risk loci for ADHD. 2018 doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0269-7. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klein RG, Mannuzza S, Ramos Olazagasti MA, et al. Clinical and functional outcome of childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder 33 years later. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(12):1295–1303. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hechtman L, Swanson JM, Sibley MH, et al. Functional adult outcomes 16 years after childhood diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: MTA results. J Am Acad Child Adol Psychiatry. 2016;55(11):945–952. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.07.774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Swanson EN, Owens EB, Hinshaw SP. Pathways to self-harmful behaviors in young women with and without ADHD: a longitudinal examination of mediating factors. J Child Psychol Psychiatr. 2014;55(5):505–515. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ustun B, Adler LA, Rudin C, et al. The World Health Organization Adult Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Self-Report Screening Scale for DSM-5. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(5):520–526. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Polanczyk G, de Lima MS, Horta BL, Biederman J, Rohde LA. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: A systematic review and metaregression analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:942–948. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scahill L, Schwab-Stone M, Merikangas KR, Leckman JF, Zhang H, Kasl S. Psychosocial and clinical correlates of ADHD in a community sample of school-age children. J Am Acad Child Adol Psychiatr. 1991;38(8):976–984. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199908000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.