Abstract

Tryptophyquinone-bearing enzymes contain protein-derived cofactors formed by posttranslational modifications of Trp residues. Tryptophan tryptophylquinone (TTQ) is comprised of a di-oxygenated Trp residue, which is cross-linked to another Trp residue. Cysteine tryptophylquinone (CTQ) is comprised of a di-oxygenated Trp residue, which is cross-linked to a Cys residue. Despite the similarity of these cofactors, it has become evident in recent years that the overall structures of the enzymes that possess these cofactors vary, and that the gene clusters that encode the enzymes are quite diverse. While it had been long assumed that all tryptophylquinone enzymes were dehydrogenases, recently discovered classes of these enzymes are oxidases. A common feature of enzymes that have these cofactors is that the posttranslational modifications that form the mature cofactors are catalyzed by a modifying enzyme. However, it is now clear that modifying enzymes are different for different tryptophylquinone enzymes. For methylamine dehydrogenase a di-heme enzyme, MauG, is needed to catalyze TTQ biosynthesis. However, no gene similar to mauG is present in the gene clusters that encode the other enzymes, and the recently characterized family of CTQ-dependent oxidases, termed LodA-like proteins, require a flavoenzyme for cofactor biosynthesis.

Keywords: Amine dehydrogenase, Amine oxidase, Quinoprotein, Posttranslational modification, Redox cofactor, Tryptophan

Introduction

Tryptophylquinone enzymes possess tryptophan residues that have undergone posttranslational modifications that enable them to participate in catalysis and redox reactions. They are members of a broader group of enzymes that contain a variety of protein-derived cofactors [1], in which catalytic and redox centers of the enzymes are formed from irreversible posttranslational modification of one or more amino acid residues. Two types of tryptophan- derived cofactors have been identified (Figure 1), tryptophan tryptophylquinone (TTQ) [2] and cysteine tryptophylquinone (CTQ) [3]. In both TTQ and CTQ, two oxygen atoms are inserted into the indole ring of a specific Trp residue. In TTQ, this modified side chain is cross-linked to the indole ring of another Trp. In CTQ, it is cross-linked to a Cys sulfur. The tryptophylquinone enzymes that have been characterized thus far are similar in that each oxidizes primary amines. Methylamine dehydrogenase (MADH) [4] and aromatic amine dehydrogenase (AADH) [5] possess TTQ. Quinohemoprotein amine dehydrogenase (QHNDH) possesses CTQ, as well as two c-type hemes [3]. The lysine ε-oxidase, LodA [6], and the glycine oxidase, GoxA [7], each possess CTQ. There are striking differences in the overall structures of these enzymes. However, comparison of these structures reveals that features of the active sites of the enzymes are conserved. While the initial steps in the reactions catalyzed by the tryptophylquinone enzymes are similar, there are some notable differences in the overall reaction mechanisms. The genes present in the operons that encode the enzymes vary considerably. While each of these enzymes requires a modifying enzyme to catalyze posttranslational modifications that form the quinone cofactor, the nature of modifying enzyme varies depending upon the enzyme that bears the tryptophylquinone cofactor.

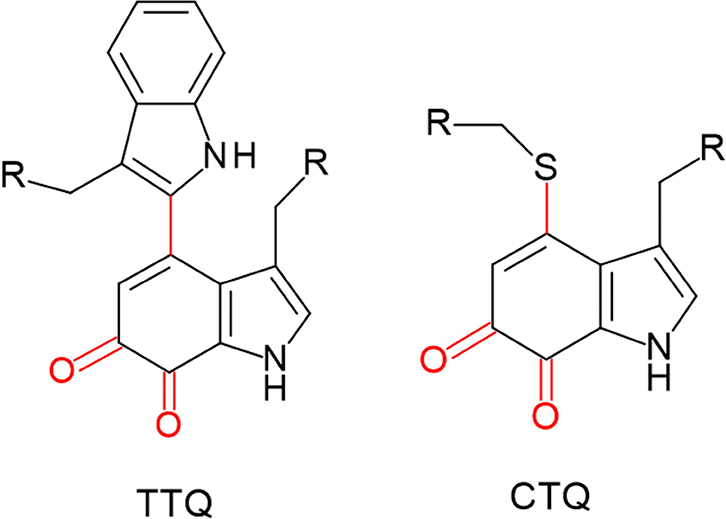

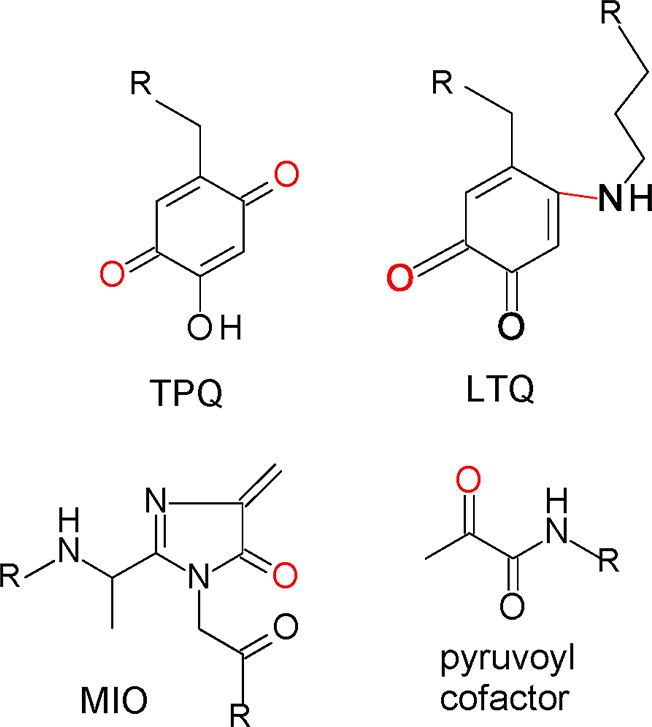

Figure 1.

Tryptophan tryptophylquinone (TTQ) and cysteine tryptophylquinone (CTQ). The posttranslational modifications of the residues are shown in red and R indicated point on the protein where the residues are attached.

Structures of tryptophylquinone enzymes

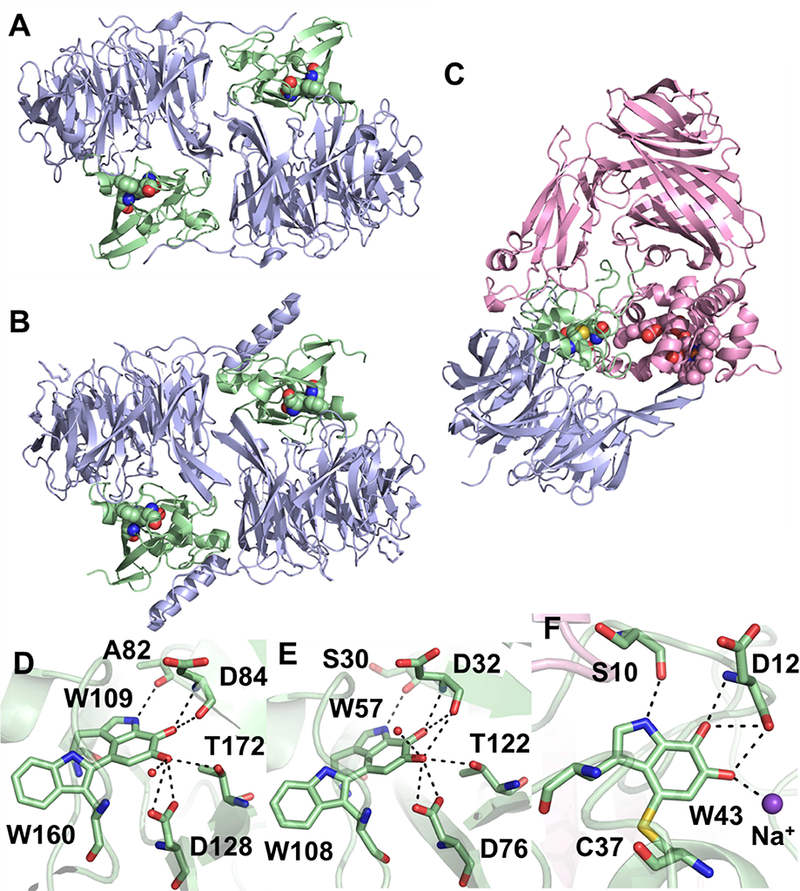

Crystal structures for the TTQ-containing enzymes, MADH and AADH, and the CTQ- containing enzymes, QHNDH, LodA and GoxA, have been solved to high resolution (Table 1 and references therein). AADH (Figure 2A) and MADH (Figure 2B) are α2β2 heterotetramers with similar structures (rmsd = 2.2 Å for α-carbons) and high sequence identity in both α (40%) and β (23%) chains. The TTQ cofactor (Figure 2D,E) in each of these enzymes is formed between two Trp residues in the smaller β subunit. QHNDH is an αβγ heterotrimer (Figure 2C) with the active site formed from Cys and Trp residues on the γ subunit (Figure 2F). The 𝛼 subunits of MADH and AADH are structurally similar to the β subunit of QHNDH, each forming a 7-bladed beta-propeller, while the quinone-containing subunits share no similarity. The α subunit of QHNDH is composed of four domains. The N-terminal domain (αd1) houses two c-type hemes. The remaining 𝛼 domains are comprised of antiparallel beta-barrels.

Table 1.

Representative crystal structures of the TTQ- and CTQ-containing enzymes

| Protein | Organism | Cofactor | Activity | Resolution | PDB code |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MADH |

Paracoccus denitrificans |

TTQ | dehydrogenase | 1.86 Å | 3SWS | [58] |

| MADH |

Paracoccus versutus |

TTQ | dehydrogenase | 2.50 Å | 3C75 | [59] |

| AADH | Alcaligenes faecalis | TTQ | dehydrogenase | 1.20 Å | 2AH1 | [60] |

| QHNDH |

Paracoccus denitrificans |

CTQ + 2 heme C | dehydrogenase | 2.05 Å | 1JJU | [3] |

| QHNDH |

Pseudomonas putida |

CTQ + 2 heme C | dehydrogenase | 1.90 Å | 1JMX | [61] |

| LodA |

Marinomonas mediterranea |

CTQ | oxidase | 1.93 Å | 3WEU | [6] |

| GoxA |

Pseudoalteromonas luteoviolaceae |

CTQ | oxidase | 2.05 Å | 6BYW | [7] |

Figure 2.

(A) AADH from Alcaligenes faecalis (PDB ID: 2AH1) and (B) MADH from Paracoccus denitrificans (PDB ID: 3SWS with the MauG chains omitted) with the α and β subunits shown as blue and green cartoon, respectively. The TTQ cofactors are shown as spheres. (C) QHNDH from Paracoccus denitrificans (PDB ID: 1JJU) with the α, β and γ subunits shown as pink, blue and green cartoon, respectively. The CTQ and heme cofactors are shown as spheres. Stick representations of the quinone cofactors from AADH (D), MADH (E) and QHNDH (F) showing interactions at < 3.5 Å with protein residues shown as sticks, water molecules shown as red spheres or a Na+ shown as a purple sphere.

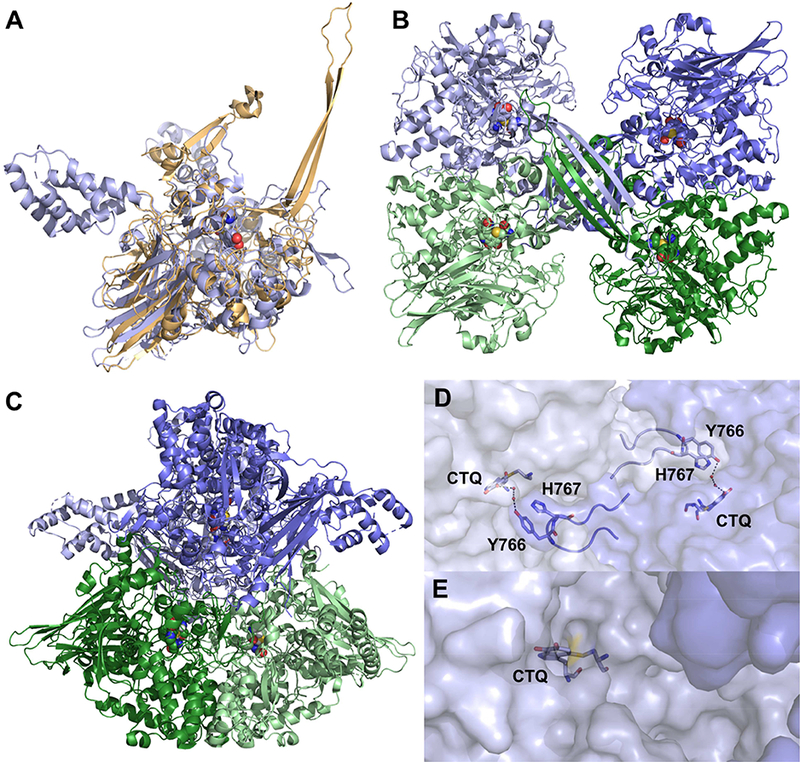

LodA from Marinomonas mediterranea and GoxA from Pseudoalteromonas luteoviolacea are currently the only structures of a recently identified group of CTQ-containing enzymes called LodA-like proteins, which are widespread among bacterial species [8]. They share a novel fold featuring a large a-helical region and a beta-barrel (Figure 3A). GoxA contains an additional alpha helical domain of unknown function while LodA contains two long “arms” consisting of two antiparallel beta strands. Crystallographically, both proteins form homotetramers (Figure 3B and C), although only GoxA exhibits a molecular weight consistent with this in size exclusion chromatography [7], while LodA is predicted to exist as a homodimer in solution [9]. Interestingly, the subunit interfaces are completely different between the proteins. In LodA, two possible dimer interactions are mediated by the “arms” mentioned above. These structures are completely absent in GoxA, which instead exhibits tight intersubunit interactions to form a dimer of dimers. A particularly intriguing feature of the GoxA structure is the insertion of a loop of one subunit into the active site of another. Tyr766 and His767 of this loop interact with the CTQ cofactor through water molecules, generating a very small, buried active site (Figure 3D). This is in contrast to the relatively open active site of LodA (Figure 3E). The size of the active site pocket as determined by quaternary structure is thus a likely contributor to the high specificity of LodA and GoxA for lysine and glycine, respectively.

Figure 3.

(A) Alignment of GoxA from Pseudoalteromonas luteoviolaceae (blue, PDB ID: 6BYW) and LodA from Marinomonas mediterranea (gold, PDB ID: 3WEU). The homotetrameric assembly of LodA (B) and GoxA (C) are presented with subunits shown in shades of blue and green. Intersubunit interactions in GoxA (D) illustrate how the CTQ active site is closed versus the open active site of LodA (E). Subunits are shown in shades of blue.

Catalytic mechanisms of tryptophylquinone enzymes

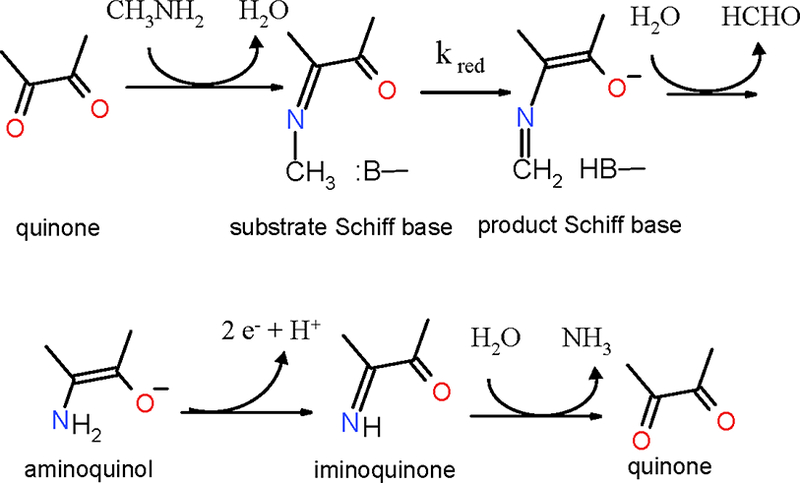

The kinetic and chemical reaction mechanisms of MADH and AADH have been characterized (Figure 4). Each exhibits a ping-pong kinetic mechanism with discrete reductive and oxidative half-reactions. The first step is the formation of a covalent imine (substrate Schiff base) adduct between the primary amino group of the substrate and TTQ. This is followed by abstraction of a proton from the α carbon of the bound substrate by an as yet unidentified active- site base. This proton abstraction results in reduction of TTQ and formation of the product Schiff base. Hydrolysis of the product Schiff base releases the aldehyde product and leaves a reduced aminoquinol form of TTQ [10]. This intermediate is then oxidized by the electron acceptor, converting the aminoquinol to an iminoquinone. The substrate-derived ammonia product is either released by hydrolysis or is displaced imine exchange with direct substrate Schiff base formation with another molecule of substrate in the steady-state reaction [11, 12]. The electron acceptors are Type 1 copper proteins, amicyanin [13] for MADH and azurin for AADH [14]. MADH and AADH each exhibited an anomalously large deuterium kinetic isotope effect (KIE) of 17.2 [15] and 11.7 [16], respectively, on the rate of reduction of TTQ by substrate in single-turnover kinetics studies. This indicates that the proton abstraction in the reductive half-reaction occurred by quantum mechanical proton tunneling [17].

Figure 4.

Reaction mechanism of MADH. Only a portion of the TTQ cofactor is shown. B indicates and active site base.

Analogous kinetic studies of QHNDH are complicated by the fact that QHNDH possesses not only CTQ, but also two covalent c-type hemes. As such, the electron acceptors for the reduced CTQ are present in the same enzyme, making it difficult to distinguish the reductive and oxidative half-reactions. Transient kinetic studies of the CTQ-dependent reduction of heme in QHNDH by amine substrates yielded deuterium KIE values of 3.9 and 8.5, respectively, for the reactions with butylamine and benzylamine [18], indicating that the abstraction of a proton from the α-methylene group of the substrate is at least partially rate-limiting the CTQ-dependent reduction of hemes in QHNDH by these amine substrates. In this respect, QHNDH is similar to MADH and AADH.

LodA and GoxA are oxidases rather than dehydrogenases. LodA has also been shown to exhibit a ping-pong kinetic mechanism with lysine and O2 as substrates [19]. The reaction of GoxA, however, is more complicated. This enzyme does not obey Michaelis-Menten kinetics but shows cooperativity towards the glycine substrate [7, 20]. In contrast to the dehydrogenases, the rate of reduction of CTQ by deuterated glycine by GoxA exhibited a negligible primary KIE of 1.08 [7]. Also in contrast to the dehydrogenases, it was shown for GoxA that the reduced CTQ- product adduct is not immediately hydrolyzed after the reductive half-reaction. It remains bound, and it is not released until it is exposed to O2 [7]. Future studies will hopefully determine the basis for this resistance to hydrolysis and the mechanism by which O2 facilitates hydrolysis.

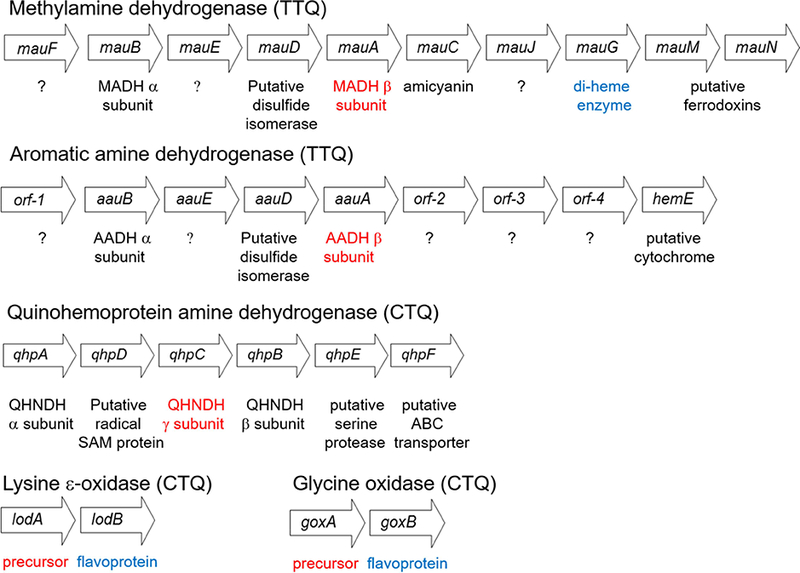

Organization of gene clusters encoding tryptophylquinone enzymes

The diversity in the overall structures of tryptophylquinone enzymes is reflected in the gene clusters, which contain the genes encoding the structural proteins (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Gene clusters which encode different enzymes with TTQ or CTQ cofactors. These are the genes present in MADH from P. denitrificans [22], AADH from Alcalgenes faecalis [31], QHNDH from P. denitrificans [32], LodA from M. mediteranea [35], and GoxA from M. mediteranea [34]. The quinone-bearing gene products are indicated in red and the known modifying enzymes are indicated in blue.

MADH.

The genes that encode the structural subunits of MADH are present in a relatively large methylamine utilization (mau) gene cluster [21]. The mau cluster of P. denitrificans, as well as most other bacteria which express MADH, contains 11 genes [22]. The genes mauB and mauA, encode the α and β subunits of MADH, respectively. Amicyanin, the electron acceptor for reduced MADH is encoded by mauC [23]. Four additional genes are required for expression of active MADH, mauF [24], mauE [25], mauD [25] and mauG [22]. It should be noted that expression of active MADH requires not only biosynthesis of TTQ, but also formation of six disulfide bounds on the 131 residue TTQ-bearing β subunit and translocation of the subunits to the periplasm. The functions of mauF and mauE are unknown. The sequence of mauD suggests that it may be a disulfide isomerase, which could be required for correct disulfide bond formation, although this protein has never been isolated. As predicted from the sequence of mauG, the gene product MauG possesses two c-type hemes [26, 27]. This enzyme has been shown to catalyze the final three two-electron oxidation reactions during the formation of TTQ from the two Trp residues on the precursor protein of MADH [26–30] (discussed later). The roles of the mauJ, mauM and mauN are unknown and they are not required for MADH production.

AADH.

The aromatic amine utilization (aau) gene cluster also possesses several genes [31]. The genes that encode the structural subunits of AADH and the intervening two genes (aauBEDA) are similar to mauBEDA in the mau cluster. However, the rest of the gene cluster is quite different. There is no amicyanin gene, which is consistent with the role of azurin, a constitutively expressed protein, serving as the electron acceptor for AADH. There is also no mauG ortholog present. The sequence of orf-2 is predicted to encode a monoheme c-type cytochrome with no known function. The functions of the remaining genes are unknown.

QHNDH.

The gene cluster that encodes QHNDH [32] is even less similar to that of MADH, consistent with the lack of overall structural similarity. An interesting feature of the CTQ-bearing γ subunit of this enzyme, which is encoded by qhpC, is that it lacks the multiple disulfide bonds seen in the corresponding subunits in MADH and AADH. Instead, this 82-residue subunit contains three covalent thioether cross-links between a Cys sulfur and a side-chain carbon of an Asp or Glu residue [3]. A gene predicted to encode a putative disulfide isomerase is not present in this cluster. Instead, the operon contains qhpD, which encodes a radical SAM enzyme. Evidence has been presented that this gene product is required for formation of the thioether bonds [33]. The mechanism of CTQ formation in QHNDH is unknown. It is noteworthy that while no mauG-like gene is present, the a subunit encoded by qhpA contains two c-type hemes. This suggests the possibility that the diheme subunit might catalyze CTQ formation, as does MauG, but remains bound to function in catalysis in the mature enzyme. However, no evidence has been obtained to support this idea. It is also possible that additional genes are required that that have not been identified.

LodA-like proteins.

The operon for the CTQ-dependent LodA is completely different from those of the other TTQ and CTQ-dependent dehydrogenases, which are described above. In addition to lodA, which encodes the single subunit precursor protein, there is a second gene lodB, which is predicted to encode a flavoprotein. Coexpression of lodB with lodA is required to generate the active enzyme with mature CTQ [34, 35]. The same has been shown for glycine oxidase, where coexpression of goxA with goxB is required to obtain the active enzyme with CTQ [34, 36]. In this case, it has been demonstrated that GoxB is a flavoprotein [36] as predicted from sequence. Genome mining phylogenetic analysis of microbial genomes reported in 2015 identified 168 LodA-like proteins that clustered in five different major groups [8]. LodA was present in group I and GoxA was present in group II.

Mechanisms of tryptophylquinone cofactor biogenesis

The requirement for a modifying enzyme for tryptophylquinone biosynthesis has been experimentally demonstrated for TTQ in MADH [27, 28], and for CTQ in LodA [34, 35] and GoxA [34, 36]. In each case, expression in the absence of the modifying enzyme yielded inactive protein without the cofactor, and analysis of the inactive protein by proteolysis and mass spectrometry reveled the initial hydroxylation of the Trp had occurred in the absence of the modifying enzyme [34]. This indicated that this first step was an autocatalytic reaction. Mutation of the structurally conserved βAsp76 in the active site of MADH resulted in production of protein with no modifications at all [37]. Similarly, mutation of the corresponding Asp512 in LodA affected this first hydroxylation step [34]. In this case, about 95% of the isolated protein had no modifications, but about 5% of the protein was active and possessed CTQ. Metal analysis and spectroscopic analysis of the inactive and active variants strongly suggested that the initial hydroxylation is a copper-dependent process, and that after cofactor maturation the copper is no longer present or required for catalysis. It was proposed that an active site Asp residue dictates the selectivity for copper binding in the unmodified protein and that the hydroxylation proceeds via a Cu3+-OH intermediate, which is stabilized by a Cys sulfur and oxidizes the Trp [38].

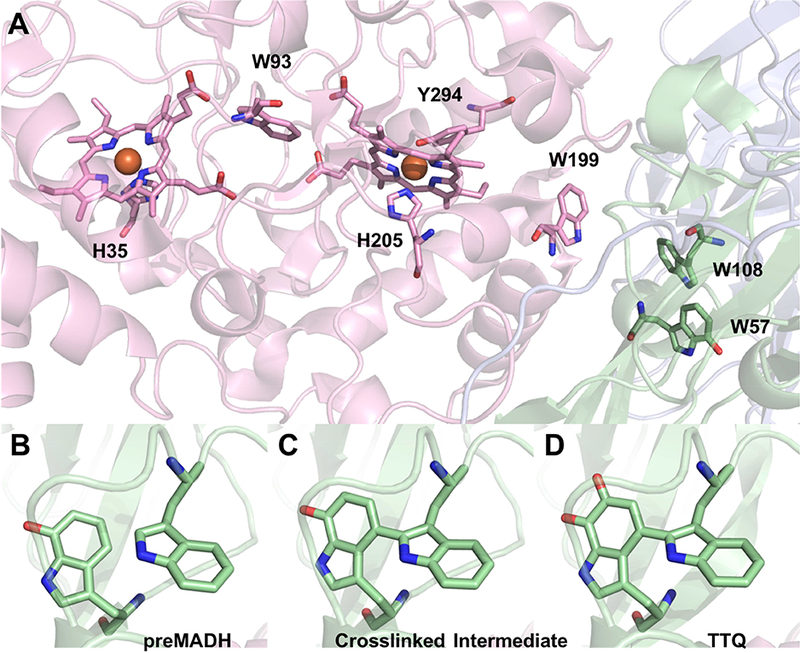

The conversion of the monohydroxylated precursor of MADH (preMADH) to mature MADH by MauG has been achieved in vitro [30]. Catalysis of the posttranslational modifications by the diheme enzyme MauG requires addition of either H2O2, or a reductant plus O2 [39]. Either of these generates a bis-FeIV state of MauG in which one heme is FeIV=O with a His axial ligand and the other is FeIV with axial ligation by a His and a Tyr with no external ligand [40]. This novel high-valent species was characterized by EPR and Mossbauer [40], and X-ray absorption [41] spectroscopy. A Trp residue between the hemes mediates charge- resonance stabilization of the two FeIV hemes [40, 42]. The complex of MauG and preMADH was crystallized (Figure 6A) and it was possible to observe the biosynthesis of TTQ in the crystal after exposure to H2O2 [26]. The distances between the residues on preMADH that are modified and the heme irons on MauG are 40.1 Å and 19.4 Å. Thus, the catalytic oxidation reactions require long-range electron transfer from the amino acid residues that are modified (Figure 6B) to the hemes. Site directed mutagenesis and kinetic studies indicated that this involved a holehopping mechanism of electron transfer [43, 44]. Mutation of a conserved MauG Trp residue at the MauG-preMADH interface blocked the reaction [43] and analysis of the electron transfer rates by Marcus Theory was consistent with the reactions occurring by a multi-step hole-hopping mechanism rather than a single electron tunneling step [44].

Figure 6.

(A) Crystal structure of the MauG-preMADH complex (PDB ID: 3L4M). MauG is shown in pink, α-MADH in blue and β-MADH in green cartoon. Important residues and cofactors are shown as sticks colored according to element. Structure of the preMADH site (B), the cross-linked intermediate (PDB ID: 3FAN) (C) and the mature TTQ cofactor (PDB ID: 3FA1) (D).

The overall biosynthetic reaction requires three two-electron oxidations. Rapid freeze- quench and high-frequency high-field EPR studies revealed that the initial intermediate that is formed by the first two-electron transfer is a di-radical, with one electron removed from the monohydroxylated Trp and the other removed from the other unmodified Trp [29]. Consistent with these data was the observation in the crystal of the preMADH-MauG complex that the covalent crosslink between these two Trps is the product of the first two-electron oxidation [29] (Figure 6C). Given the long distance between the residues that are modified and the oxygenbinding heme of MauG, the second oxygen that is inserted into the monohydroxylated Trp moiety must be acquired from solvent in the active site of the substrate protein during maturation of TTQ, after the second two-electron transfer generates another radical intermediate. The final two-electron transfer then oxidizes the quinol cofactor to the mature TTQ (Figure 6D).

There is evidence for the requirement of a modifying enzyme for CTQ biosynthesis in LodA and GoxA. This was demonstrated by knocking out lodB in the native system [35], thus preventing formation of active LodA, and in the recombinant systems where coexpression of lodB with lodA, and goxB with goxA, are required to express active LodA and GoxB, respectively, with mature CTQ [34]. The biosynthesis of CTQ from the precursor proteins has not yet been achieved in vitro. However, from the data presented thus far there are clear distinctions in the mechanisms of cofactor biogenesis between the TTQ-dependent dehydrogenases and the CTQ-dependent oxidases. Whereas biosynthesis of TTQ in MADH is catalyzed by a diheme enzyme, MauG, for LodA and GoxA the biosynthesis of CTQ is catalyzed by a flavoenzyme, LodB or GoxB. Furthermore, the sequence of cofactor biosynthesis and subunit assembly appears to differ between the two groups of enzymes. The biosynthesis of TTQ on preMADH appears to occur after the assembly of the α2β2 heterotetramer. The crystal structure of preMADH in the complex with MauG is essentially identical to that of the structure of the mature MADH [4], except for the lack of posttranslational modifications that form TTQ. Two MauG molecules interact with preMADH in the symmetrical complex [26]. GoxA from two different species has been expressed; Marinomonas mediterranea [36] and Pseudoalteromonas luteoviolacea [7]. In the case of GoxA from M. mediterranea, it appears that CTQ formation precedes subunit assembly. Two forms of GoxA were isolated during the recombinant coexpression with goxB. One was active GoxA with CTQ that migrated as a homodimer on size exclusion chromatography. The other was inactive and lacked CTQ, and was isolated in complex with GoxB [36]. This species migrated as a complex of one GoxA and one GoxB. When the inactive preGoxA was isolated, in the absence of GoxB the preGoxA tended to form large aggregates. This suggests that during the biosynthesis of CTQ on each preGoxA monomer precedes formation of the native homodimer.

That tryptophylquinone enzymes require modifying enzymes for the posttranslational modifications necessary to form TTQ and CTQ distinguishes these enzymes from enzymes that possess other types of protein-derived cofactors. This is especially true for enzymes which possess other protein-derived cofactors with reactive carbonyl groups that are formed by posttranslational modification (Figure 7). The tyrosylquinone cofactors, 2,4,5- trihydroxyphenylalanine-quinone (TPQ) [45] and lysine tyrosylquinone (LTQ) [46], are present in copper-containing amine oxidases and lysyl oxidase-like proteins, respectively [47]. In TPQ two oxygen atoms have been inserted into a Tyr side-chain. In LTQ, one oxygen has been inserted into a Tyr side-chain and it forms a crosslink with nitrogen on a Lys side-chain. The formation of these cofactors is an autocatalytic process that requires only the presence of copper and O2 [48–50]. There are two other protein derived carbonyl cofactors that are not quinones (Figure 7). One is 4-methylideneimidazole-5-one (MIO) that is found in certain aminomutases and ammonia lyases [51]. Formation of MIO is a process during which an internal Ala-Ser-Gly segment of the protein is modified. MIO formation proceeds via autocatalytic cyclization of that triad of amino acid residues and dehydration reactions [52, 53]. The pyruvoyl cofactor [54] is present in certain decarboxylases and reductases. It is formed on a precursor protein, which undergoes cleavage of an internal peptide bond resulting in two tightly bound protein subunits with the catalytically active pyruvoyl group at the N terminus of one of the chains. This process has been considered autocatalytic [55], although there is now evidence that in at least some cases an accessory protein is required [56, 57]. However, it appears to function as a chaperone rather than play a direct role in catalysis.

Figure 7.

Other protein-derived carbonyl cofactors. The posttranslational modifications of the residues are shown in red and R indicates point on the protein where the residues are attached.

Summary

Recent characterization of the CTQ-dependent oxidases, LodA and GoxA, have highlighted the fact that the structures, functions, and mechanisms of cofactor biogenesis of tryptophylquinone enzyme are more diverse than previously believed. While the mechanism of TTQ biosynthesis in MADH is well characterized, more detailed characterizations of the mechanisms of cofactor biosynthesis in the other enzymes is likely to describe novel reaction mechanisms of catalysis by other modifying enzymes. As more tryptophylquinone enzymes are characterized, it is also likely the range of reactions that they catalyze will be expanded.

Acknowledgments

Funding

Work from the author’s laboratory was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number R37GM41574 (V.L.D.).

Abbreviations:

- AADH

aromatic amine dehydrogenase

- CTQ

cysteine tryptophylquinone

- KIE

kinetic isotope effect

- QHNDH

quinohemoprotein amine dehydrogenase

- LTQ

lysine tyrosylquinone

- MADH

methylamine dehydrogenase

- MIO

4-methylideneimidazole-5-one

- TPQ

2,4,5-trihydroxyphenylalanine-quinone

- TTQ

tryptophan tryptophylquinone

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Davidson VL, Protein-derived cofactors. Expanding the scope of post-translational modifications, Biochemistry 46 (2007) 5283–5292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].McIntire WS, Wemmer DE, Chistoserdov A, Lidstrom ME, A new cofactor in a prokaryotic enzyme: tryptophan tryptophylquinone as the redox prosthetic group in methylamine dehydrogenase, Science 252 (1991) 817–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Datta S, Mori Y, Takagi K, Kawaguchi K, Chen ZW, Okajima T, Kuroda S, Ikeda T, Kano K, Tanizawa K, Mathews FS, Structure of a quinohemoprotein amine dehydrogenase with an uncommon redox cofactor and highly unusual crosslinking, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98 (2001) 14268–14273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Chen L, Doi M, Durley RC, Chistoserdov AY, Lidstrom ME, Davidson VL, Mathews FS, Refined crystal structure of methylamine dehydrogenase from Paracoccus denitrificans at 1.75 A resolution, J Mol Biol 276 (1998) 131–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Sukumar N, Chen ZW, Ferrari D, Merli A, Rossi GL, Bellamy HD, Chistoserdov A, Davidson VL, Mathews FS, Crystal structure of an electron transfer complex between aromatic amine dehydrogenase and azurin from Alcaligenes faecalis, Biochemistry 45 (2006) 13500–13510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Okazaki S, Nakano S, Matsui D, Akaji S, Inagaki K, Asano Y, X-Ray crystallographic evidence for the presence of the cysteine tryptophylquinone cofactor in L-lysine epsilon-oxidase from Marinomonas mediterranea, J Biochem 154 (2013) 233–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Andreo-Vidal A, Mamounis K, Sehanobish E, Avalos D, Campillo-Brocal JC, Sanchez-Amat A, Yukl ET, Davidson VL, Structure and enzymatic properties of an unusual cysteine tryptophylquinone-dependent glycine oxidase from Pseudoalteromonas luteoviolacea, Biochemistry 57 (2018) 1155–1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Campillo-Brocal JC, Chacon-Verdu MD, Lucas-Elio P, Sanchez-Amat A, Distribution in microbial genomes of genes similar to lodA and goxA which encode a novel family of quinoproteins with amino acid oxidase activity, BMC Genomics 16 (2015) 231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Lucas-Elio P, Hernandez P, Sanchez-Amat A, Solano F, Purification and partial characterization of marinocine, a new broad-spectrum antibacterial protein produced by Marinomonas mediterranea, Biochim Biophys Acta 1721 (2005) 193–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Bishop GR, Valente EJ, Whitehead TL, Brown KL, Hicks RT, Davidson VL, Direct detection by 15N-NMR of the tryptophan tryptophylquinone aminoquinol reaction intermediate of methylamine dehydrogenase., J.Am.Chem.Soc 118 (1996) 12868–12869. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Zhu Z, Davidson VL, Identification of a new reaction intermediate in the oxidation of methylamine dehydrogenase by amicyanin, Biochemistry 38 (1999) 4862–4867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Davidson VL, Sun D, Evidence for substrate activation of electron transfer from methylamine dehydrogenase to amicyanin, J Am Chem Soc 125 (2003) 3224–3225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Husain M, Davidson VL, An inducible periplasmic blue copper protein from Paracoccus denitrificans. Purification, properties, and physiological role, J Biol Chem 260 (1985) 14626–14629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Hyun YL, Davidson VL, Electron transfer reactions between aromatic amine dehydrogenase and azurin, Biochemistry 34 (1995) 12249–12254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Brooks HB, Jones LH, Davidson VL, Deuterium kinetic isotope effect and stopped-flow kinetic studies of the quinoprotein methylamine dehydrogenase, Biochemistry 32 (1993) 2725–2729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Hyun YL, Davidson VL, Unusually large isotope effect for the reaction of aromatic amine dehydrogenase. A common feature of quinoproteins?, Biochim Biophys Acta 1251 (1995) 198–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Basran J, Patel S, Sutcliffe MJ, Scrutton NS, Importance of barrier shape in enzyme- catalyzed reactions. Vibrationally assisted hydrogen tunneling in tryptophan tryptophylquinone- dependent amine dehydrogenases, J Biol Chem 276 (2001) 6234–6242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Sun D, Ono K, Okajima T, Tanizawa K, Uchida M, Yamamoto Y, Mathews FS, Davidson VL, Chemical and kinetic reaction mechanisms of quinohemoprotein amine dehydrogenase from Paracoccus denitrificans, Biochemistry 42 (2003) 10896–10903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Sehanobish E, Shin S, Sanchez-Amat A, Davidson VL, Steady-state kinetic mechanism of LodA, a novel cysteine tryptophylquinone-dependent oxidase, FEBS Lett 588 (2014) 752–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Sehanobish E, Williamson HR, Davidson VL, Roles of conserved residues of the glycine oxidase GoxA in controlling activity, cooperativity, subunit composition, and cysteine tryptophylquinone biosynthesis, J Biol Chem 291 (2016) 23199–23207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Chistoserdov AY, Boyd J, Mathews FS, Lidstrom ME, The genetic organization of the mau gene cluster of the facultative autotroph Paracoccus denitrificans, Biochem Biophys Res Commun 184 (1992) 1181–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].van der Palen CJ, Slotboom DJ, Jongejan L, Reijnders WN, Harms N, Duine JA, van Spanning RJ, Mutational analysis of mau genes involved in methylamine metabolism in Paracoccus denitrificans, Eur J Biochem 230 (1995) 860–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].van Spanning RJ, Wansell CW, Reijnders WN, Oltmann LF, Stouthamer AH, Mutagenesis of the gene encoding amicyanin of Paracoccus denitrificans and the resultant effect on methylamine oxidation, FEBS Lett. 275 (1990) 217–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Chistoserdov AY, Chistoserdova LV, McIntire WS, Lidstrom ME, Genetic organization of the mau gene cluster in Methylobacterium extorquens AM1: complete nucleotide sequence and generation and characteristics of mau mutants, J Bacteriol 176 (1994) 4052–4065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].van der Palen CJ, Reijnders WN, de Vries S, Duine JA, van Spanning RJ, MauE and MauD proteins are essential in methylamine metabolism of Paracoccus denitrificans, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 72 (1997) 219–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Jensen LM, Sanishvili R, Davidson VL, Wilmot CM, In crystallo posttranslational modification within a MauG/pre-methylamine dehydrogenase complex, Science 327 (2010) 1392–1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Wang Y, Graichen ME, Liu A, Pearson AR, Wilmot CW, Davidson VL, MauG, a novel diheme protein required for tryptophan tryptophylquinone biogenesis, Biochemistry 42 (2003) 7318–7325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Pearson AR, de la Mora-Rey T, Graichen ME, Wang Y, Jones LH, Marimanikkupam S, Aggar SA, Grimsrud PA, Davidson VL, Wilmot CW, Further insights into quinone cofactor biogenesis: Probing the role of mauG in methylamine dehydrogenase TTQ formation, Biochemistry 43 (2004) 5494–5502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Yukl ET, Liu F, Krzystek J, Shin S, Jensen LM, Davidson VL, Wilmot CM, Liu A, Diradical intermediate within the context of tryptophan tryptophylquinone biosynthesis, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110 (2013) 4569–4573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Davidson VL, Wilmot CM, Posttranslational biosynthesis of the protein-derived cofactor tryptophan tryptophylquinone, Annu Rev Biochem 82 (2013) 531–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Chistoserdov AY, Cloning, sequencing and mutagenesis of the genes for aromatic amine dehydrogenase from Alcaligenes faecalis and evolution of amine dehydrogenases, Microbiology 147 (2001) 2195–2202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Nakai T, Deguchi T, Frebort I, Tanizawa K, Okajima T, Identification of genes essential for the biogenesis of quinohemoprotein amine dehydrogenase, Biochemistry 53 (2014) 895–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Ono K, Okajima T, Tani M, Kuroda S, Sun D, Davidson VL, Tanizawa K, Involvement of a putative [Fe-S]-cluster-binding protein in the biogenesis of quinohemoprotein amine dehydrogenase, J Biol Chem 281 (2006) 13672–13684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Chacon-Verdu MD, Campillo-Brocal JC, Lucas-Elio P, Davidson VL, Sanchez- Amat A, Characterization of recombinant biosynthetic precursors of the cysteine tryptophylquinone cofactors of l-lysine-epsilon-oxidase and glycine oxidase from Marinomonas mediterranea, Biochim Biophys Acta 1854 (2015) 1123–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Gomez D, Lucas-Elio P, Solano F, Sanchez-Amat A, Both genes in the Marinomonas mediterranea lodAB operon are required for the expression of the antimicrobial protein lysine oxidase, Mol Microbiol 75 (2010) 462–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Sehanobish E, Campillo-Brocal JC, Williamson HR, Sanchez-Amat A, Davidson VL, Interaction of GoxA with its modifying enzyme and its subunit assembly are dependent on the extent of cysteine tryptophylquinone biosynthesis, Biochemistry 55 (2016) 2305–2308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Jones LH, Pearson AR, Tang Y, Wilmot CM, Davidson VL, Active site aspartate residues are critical for tryptophan tryptophylquinone biogenesis in methylamine dehydrogenase, J Biol Chem 280 (2005) 17392–17396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Williamson HR, Sehanobish E, Shiller AM, Sanchez-Amat A, Davidson VL, Roles of copper and a conserved aspartic acid in the autocatalytic hydroxylation of a specific tryptophan residue during cysteine tryptophylquinone biogenesis, Biochemistry 56 (2017) 997–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Li X, Jones LH, Pearson AR, Wilmot CM, Davidson VL, Mechanistic possibilities in MauG-dependent tryptophan tryptophylquinone biosynthesis, Biochemistry 45 (2006) 13276–13283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Li X, Fu R, Lee S, Krebs C, Davidson VL, Liu A, A catalytic di-heme bis-Fe(IV) intermediate, alternative to an Fe(IV)=O porphyrin radical, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105 (2008) 8597–8600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Jensen LM, Meharenna YT, Davidson VL, Poulos TL, Hedman B, Wilmot CM, Sarangi R, Geometric and electronic structures of the His-Fe(IV)=O and His-Fe(IV)-Tyr hemes of MauG, J Biol Inorg Chem 17 (2012) 1241–1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Geng J, Dornevil K, Davidson VL, Liu A, Tryptophan-mediated charge-resonance stabilization in the bis-Fe(IV) redox state of MauG, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110 (2013) 9639–9644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Abu Tarboush N, Jensen LMR, Yukl ET, Geng J, Liu A, Wilmot CM, Davidson VL, Mutagenesis of tryptophan199 suggets that hopping is required for MauG-dependent tryptophan tryptophylquinone biosynthesis, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 108 (2011) 16956–16961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Choi M, Shin S, Davidson VL, Characterization of electron tunneling and hole hopping reactions between different forms of MauG and methylamine dehydrogenase within a natural protein complex, Biochemistry 51 (2012) 6942–6949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Janes SM, Mu D, Wemmer D, Smith AJ, Kaur S, Maltby D, Burlingame AL, Klinman JP, A new redox cofactor in eukaryotic enzymes: 6-hydroxydopa at the active site of bovine serum amine oxidase, Science 248 (1990) 981–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Wang SX, Mure M, Medzihradszky KF, Burlingame AL, Brown DE, Dooley DM, Smith AJ, Kagan HM, Klinman JP, A crosslinked cofactor in lysyl oxidase: redox function for amino acid side chains, Science 273 (1996) 1078–1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Finney J, Moon HJ, Ronnebaum T, Lantz M, Mure M, Human copper-dependent amine oxidases, Arch Biochem Biophys 546 (2014) 19–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Kim M, Okajima T, Kishishita S, Yoshimura M, Kawamori A, Tanizawa K, Yamaguchi H, X-ray snapshots of quinone cofactor biogenesis in bacterial copper amine oxidase, Nat. Struct. Biol 9 (2002) 591–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Moore RH, Spies MA, Culpepper MB, Murakawa T, Hirota S, Okajima T, Tanizawa K, Mure M, Trapping of a dopaquinone intermediate in the TPQ cofactor biogenesis in a copper-containing amine oxidase from Arthrobacter globiformis, J Am Chem Soc 129 (2007) 11524–11534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Klinman JP, Bonnot F, Intrigues and intricacies of the biosynthetic pathways for the enzymatic quinocofactors: PQQ, TTQ, CTQ, TPQ, and LTQ, Chem Rev 114 (2014) 4343–4365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Parmeggiani F, Weise NJ, Ahmed ST, Turner NJ, Synthetic and therapeutic applications of ammonia-lyases and aminomutases, Chem Rev 118 (2018) 73–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Poppe L, Methylidene-imidazolone: a novel electrophile for substrate activation, Curr Opin Chem Biol 5 (2001) 512–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Retey J, Discovery and role of methylidene imidazolone, a highly electrophilic prosthetic group, Biochim Biophys Acta 1647 (2003) 179–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].van Poelje PD, Snell EE, Pyruvoyl-dependent enzymes, Ann. Rev. Biochem 59 (1990) 29–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Ramjee MK, Genschel U, Abell C, Smith AG, Escherichia coli L-aspartate-alpha- decarboxylase: preprotein processing and observation of reaction intermediates by electrospray mass spectrometry, Biochem J 323 (1997) 661–669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Monteiro DC, Patel V, Bartlett CP, Nozaki S, Grant TD, Gowdy JA, Thompson GS, Kalverda AP, Snell EH, Niki H, Pearson AR, Webb ME, The structure of the PanD/PanZ protein complex reveals negative feedback regulation of pantothenate biosynthesis by coenzyme A, Chem Biol 22 (2015) 492–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Trip H, Mulder NL, Rattray FP, Lolkema JS, HdcB, a novel enzyme catalysing maturation of pyruvoyl-dependent histidine decarboxylase, Mol Microbiol 79 (2011) 861–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Yukl ET, Jensen LM, Davidson VL, Wilmot CM, Structures of MauG in complex with quinol and quinone MADH, Acta Crystallogr Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun 69 (2013) 738–743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Cavalieri C, Biermann N, Vlasie MD, Einsle O, Merli A, Ferrari D, Rossi GL, Ubbink M, Structural comparison of crystal and solution states of the 138 kDa complex of methylamine dehydrogenase and amicyanin from Paracoccus versutus, Biochemistry 47 (2008) 6560–6570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Masgrau L, Roujeinikova A, Johannissen LO, Hothi P, Basran J, Ranaghan KE, Mulholland AJ, Sutcliffe MJ, Scrutton NS, Leys D, Atomic description of an enzyme reaction dominated by proton tunneling, Science 312 (2006) 237–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Satoh A, Kim JK, Miyahara I, Devreese B, Vandenberghe I, Hacisalihoglu A, Okajima T, Kuroda S, Adachi O, Duine JA, Van Beeumen J, Tanizawa K, Hirotsu K, Crystal structure of quinohemoprotein amine dehydrogenase from Pseudomonas putida. Identification of a novel quinone cofactor encaged by multiple thioether cross-bridges, J Biol Chem 277 (2002) 2830–2834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]