Abstract

Having accidental deaths from opioid overdoses almost quadrupled over the past fifteen years, there is a strong need to develop new, non-addictive medications for chronic pain to stop one of the deadliest epidemics in American history. Given their potentially fewer on-target overdosing risks and other adverse effects compared to classical opioid drugs, attention has recently shifted to opioid allosteric modulators and G protein-biased opioid agonists as likely drug candidates to prevent and/or reverse opioid overdoses. Understanding how these molecules bind and activate their receptors at an atomistic level is key to developing them into effective new therapeutics, and molecular dynamics-based strategies are contributing tremendouslyto this understanding.

Keywords: Receptor, structure, allosteric modulator, functional selectivity, biased agonism

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Opioid drugs are still considered the “gold-standard” for pain treatment notwithstanding the different adverse effects (e.g., respiratory depression, constipation, dependence, etc.) that accompany their analgesic properties. Unfortunately, misuse of prescription opioids (e.g., oxycodone, hydrocodone, methadone, etc.) or unintended use of very potent synthetic opioids (e.g., fentanyl or carfentanil) that are often mixed with, or substituted for heroin by drug dealers [1], have recently resulted in a very serious public health crisis with more than 90 Americans dying daily from opioid overdose [2]. According to a recent report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), deaths from opioids have more than quadrupled since 1999, totaling more than half a million fatalitiesbetween years 2000 and 2015 in the US alone.

Drug-induced activation of the mu-opioid receptor (MOR), a Gprotein -coupled receptor (GPCR) located in part on brainstem neurons that control respiration, is one of the likely causes of deaths from drug overdose. Although the opioid antagonist naloxone can reverse opioidoverdoses [3], it may be ineffective against the most potent drugs (e.g., carfentanil) if not administered promptly. Thus, developing non-addictive opioid analgesics that are devoid of side effects remains high on the list of possible scientific solutions to end the current opioid epidemics, a need that has also been recently recognized by NIH leadership[4].

In search of new medicines, attention has recently shifted to atypical opioid chemotypes that either target the (orthosteric) binding site of the endogenous ligand but preferentially activate the G-protein pathway over the β-arrestin one (so-called G protein-biased agonists) or target binding sites that are different from the orthosteric site (so-called allosteric modulators). The following sections provide an overview of published examples of these opioid molecules as well as atomic-level insights from molecular dynamics (MD) simulations into the way they bind and activate opioid receptors.

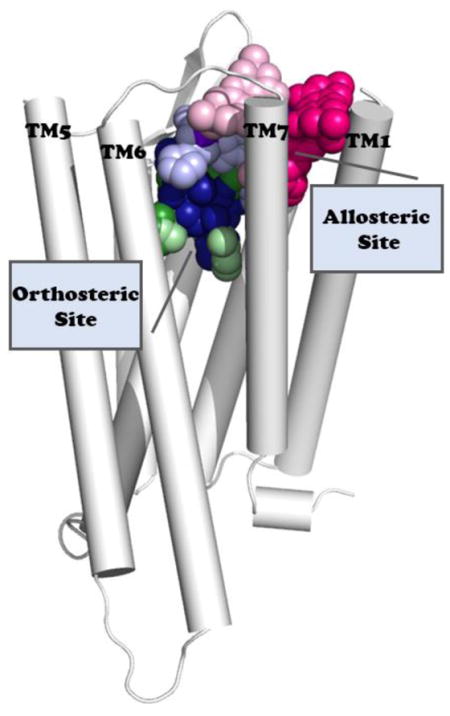

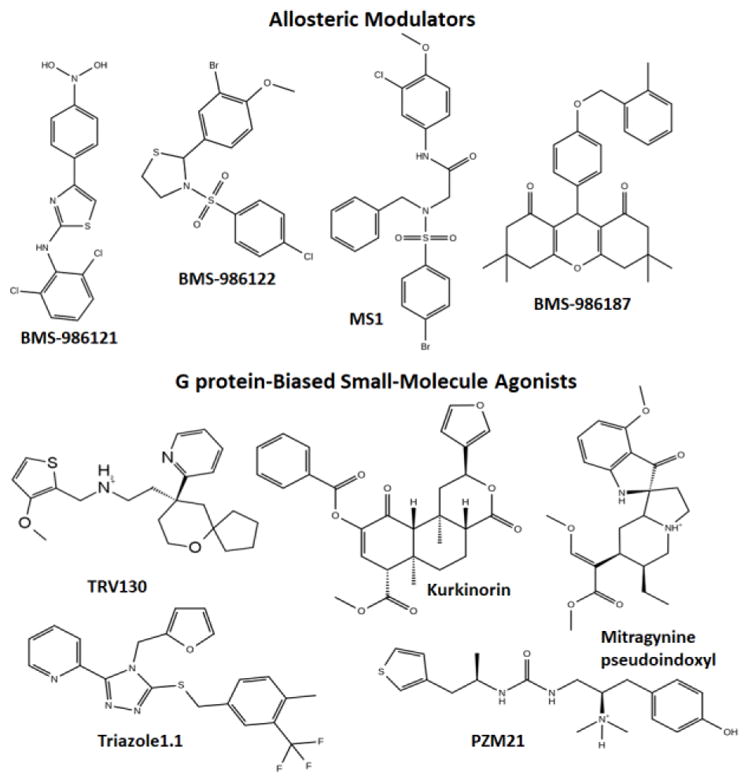

2. Confirmed small-molecule allosteric modulators of opioid receptors

While cations have been known to allosterically modulate ligand binding and signaling of opioid receptors since the seventies [5, 6], published examples of small-molecule allosteric modulators that can enhance or reduce the affinity and/or efficacy of orthosteric opioid ligands are more recent (see [7] for a recent review). These molecules have been termed positive allosteric modulators (PAMs) and negative allosteric modulators (NAMs) respectively, though silent allosteric modulators (SAMs) have also been described in the literature. Figure 1 shows two-dimensional (2D) structures of confirmed PAMs at the μ- and/or δ-opioid receptors (MOR and DOR, respectively), specifically: the MOR-PAMs BMS-986121 [8], BMS-986122 [8], and MS1 [9], and the DOR-PAM BMS-986187 [10], which shows 100-fold weaker PAM activity at MOR. A few natural products such as cannabinoid type-1 receptor (CB1) agonists cannabidiol and Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol [11], the potent κ-opioid receptor (KOR) orthosteric agonist salvinorin A [12], and ignavine [13] have also been suggested to exhibit allosteric properties at opioid receptors, but not without reservation [7]. Although SCH202676 has also been suggested to act as an allosteric modulator at DOR, MOR, and KOR [14], there are reports that suggest that this compound binds covalently to the receptor, and is therefore not an allosteric modulator [15, 16]. At the time of this writing, there are no published examples of allosteric modulators at KOR or the nociceptin receptor (NOP) [7], and no confirmed NAM at any of the opioid receptor subtypes. The interest in allosteric modulators of opioid receptors as a new avenue towards improved therapeutics mainly stems from the expectation that they exhibit fewer on-target overdosing given that their effect is limited by their cooperativity with the orthosteric agonist. This so-called “probe dependence” may of course also constitute a serious drawback as the different activities of these compounds depend on the orthosteric agonist they are used in combination with [17, 18]. Since these molecules exert an activity only in the presence of an endogenous ligand, they offer the additional advantage of preserving the temporal and spatial fidelity of signaling in vivo, and can therefore avoid the compensatory mechanisms deriving from chronic MOR activation, including those correlating with dependence, tolerance and increased toxicity. It is also expected that used in combination with classical analgesics such as morphine, opioid PAMs would require lower doses of the drug, thus limiting its tolerance and dependence.

Figure 1. Confirmed small-molecule allosteric modulators and G protein-biased small-molecule agonists of opioid receptors.

Two-dimensional structures of MOR- (BMS-986121, BMS-986122, and MS1), and DOR- (BMS-986187) positive allosteric modulators and G protein-biased MOR (TRV130 or oliceridine, kurkinorin, PZM21, and mitragynine pseudoindoxyl) and G protein-biased KOR (triazole 1.1) agonists.

3. Small-molecule G protein-biased agonists of opioid receptors

The differential ligand-induced activation of G-protein signaling over β-arrestin signaling and vice versa has been termed “functional selectivity” or “biased agonism” in the literature [19–24]. In the case of opioids, this differential activation has been linked to a possible separation between the beneficial analgesic effect of these drugs and their side effects, especially respiratory depression and constipation. Notably, the anti-nociceptive action of morphine has been attributed to the activation of MOR-mediated G protein signaling pathways based on inferences from studies of β-arrestin2 knockout mice [25, 26]. In contrast, some of the side effects of morphine, including respiratory depression and constipation, have been shown to depend on MOR-mediated β-arrestin recruitment [26–28]. Accordingly, it has been suggested that G protein-biased MOR agonists may offer new avenues toward the development of improved analgesics.

At the time of this writing, there are only a few published examples of small-molecule opioid ligands that exhibit G protein-biased agonism in vitro and a promising therapeutic profile in rodents. These are: (a) the atypical opioid chemotypes oliceridine (TRV130) [29], kurkinorin [30–32], PZM21 [33], and the mitragynine pseudoindoxyl derivative of the kratom’s major alkaloid mitragynine [34, 35] at MOR, and (b) the G protein-biased DOR agonist TRV250 [36], and (c) the G protein-biased KOR agonist triazole 1.1 [37]. These compounds, whose two-dimensional structures (with the exception of TRV250) are shown in Figure 1, exhibit analgesic properties as well as a far superior side-effect profile over classical opioids in rodents, including, reduced respiratory depression and constipation (e.g., [29]), no dysphoria or sedation (e.g., [38, 39]), and/or lack of reward effects (e.g., [35]).

To the best of my knowledge, among all published examples of G protein-biased opioid ligands with promising therapeutic profile in vivo, only TRV250 and TRV130 have so far been tested in humans. While TRV250 is currently in phase I clinical trials for migraine, TRV130 has recently progressed from phase II [40, 41] to phase III clinical trials for relief of moderate to severe pain. Trevena’s website [42] also lists TRV734 as an additional G protein-biased MOR agonist that is currently in phase I clinical trials for pain relief with improved safety and/or tolerability.

4. Mode of binding of atypical chemotypes and allosteric modulators at opioid receptors

Although several high-resolution crystal structures of opioid receptors in either inactive [43–48] or activated [49, 50] conformations have been obtained since 2012, they only explain the way classical opioid ligands bind to the orthosteric binding site of the receptor. The mode of binding of atypical orthosteric ligands or allosteric modulators at opioid receptors is unknown experimentally, and it is difficult to predict using automated docking algorithms. The reason is mainly twofold: 1) atypical opioid ligands may bind, in part, to highly flexible loop regions of the receptor, which are treated rigidly in most automated docking applications, and 2) different binding poses are difficult to discriminate using approximated scoring functions.

To study the binding of atypical opioid chemotypes to flexiblereceptors embedded in an explicit, hydrated, membrane-mimetic (e.g., 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoylphosphatidylcholine (POPC)/10% cholesterol) environment, MD simulations represent a suitable strategy. We have recently used standard or enhanced MD simulations to predict the binding mode of atypical chemical scaffolds such as TRV130 [51] and kurkinorin [30] at the MOR orthosteric site, as well as that of the allosteric modulator BMS-986187 at DOR [52]. We were first to propose the use of enhanced MD-based algorithms to more efficiently study lengthy processes mediated by GPCRs, including ligand binding (e.g., see [53]), receptor activation (e.g., see [54]), and oligomerization (e.g., see [55]), and our applications seem to have recently inspired other labs in the use of these methods (e.g., see [56]).

Unlike the binding simulations of kurkinorin and BMS-986187, TRV130 binding from the bulk to the MOR orthosteric binding site was simulated by carrying out ~44 μs of simulations at a high concentration of TRV130 [51]. The ligand visited different positions of the extracellular region of MOR, including a “vestibule” region near TM2, TM3, and TM7 before reaching the orthosteric binding site. Although this multi-step ligand binding process where metastable states are identified at a vestibule region was also noted in other GPCR systems [57], we revealed, for the first time, the presence of bound states outside the ligand’s reactive binding pathway to the orthosteric site which trap the ligand within the vestibule region, and possibly modulate the ligand binding kinetics. Among the residues involved in stabilizing intermediate states along the reactive binding pathway of TRV130 to MOR is N1272.63. Since this residue is replaced by a lysine in DOR and a valine in KOR, we speculated [51] that N1272.63 engages in interactions that the alternative residues in KOR and DOR cannot reproduce, and this may justify the selectivity that TRV130 has for MOR [29]. Note that the superscript number here and throughout the manuscript refers to the Ballesteros-Weinstein generic numbering scheme with the first digit corresponding to the helix the residue belongs to and the second one referring to the position in the helix, relative to the most conserved residue.

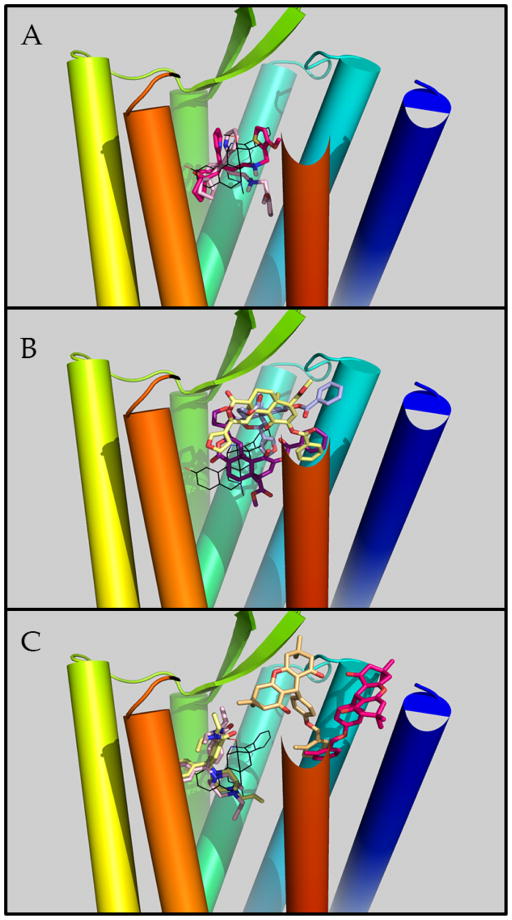

After spending time sampling the vestibule region, TRV130 proceeded towards the accepted orthosteric site of MOR. At this site, TRV130 assumed conformations that partially overlapped with the co-crystallized ligand BU72 in the active MOR, with the 6-oxaspiro[4.5]decan-9-yl moiety of TRV130 oriented towards TM5-TM6, a water-mediated interaction with D1473.32, and the methoxy-thiophen moiety oriented towards the center of the helical bundle or, for a much smaller population of ligand poses, towards the extracellular side of the receptor. Figure 2A shows these two different conformers of TRV130 within the orthosteric binding pocket of active MOR, relative to the crystallographic pose of BU72.

Figure 2. Predicted binding modes of TRV130 and kurkinorin at MOR or BMS-986187 at DOR.

Receptor’s transmembrane helices 1 through 7 are colored blue to red (please note that the extracellular side of TM7 has been eliminated to allow better visualization of ligand binding poses). The crystallographic ligand BU72 at the orthosteric binding pocket is depicted with black lines. Panel A depicts TRV130 molecules at the orthosteric binding site in light pink and magenta colors. Panel B depicts three different low-energy poses of kurkinorin in purple, light yellow, and light blue. The light yellow and light pink molecules depicted in panel C refer to the DOR orthosteric agonist SNC80 whereas light orange and magenta colors are used to illustrate the two different, low-energy poses of BMS-986187 at the DOR allosteric site.

To efficiently sample the binding of the MOR-selective and potent salvinorin A analogue kurkinorin to the receptor’s orthosteric binding pocket, we run well-tempered multiple-walker metadynamics simulations [30]. Three different low-energy bound conformations of this non-nitrogenous opioid ligand with comparable free energies were identified by these simulations. Among them, only one is partially overlapping with the co-crystallized ligand BU72 whereas the other two are located more towards the receptor extracellular side (Figure 2B). In the pose partially overlapping with BU72 (purple in Figure 2B), the furan ring of kurkinorin is oriented towards TM5 whereas the ligand’s phenyl ring is extending towards TM2. In the two more superficial poses, the ligand interacts with residues in TM1/2/6/7 or primarily with TM2/3. While in one of these poses (light blue in Figure 2B) the ligand’s phenyl ring forms interactions with residues in TM1, 2, and 7, the same ring interacts with TM2 only in the other binding pose (yellow in Figure 2B). Similarly, while the ligand’s furan ring forms interactions with TM7 in one pose (yellow in Figure 2B), it interacts with TM3 and TM2 residues in the other (light blue in Figure 2B).

As expected, our predicted binding pocket for the recently identified allosteric modulator BMS-986187 at DOR [10] is also located towards the extracellular side of the receptor and it is surrounded by TM1, TM2, and TM7 helices, with some involvement of TM6, according to the results of metadynamics simulations of BMS-986187 binding to DOR in an explicit lipid-water environment and with the selective DOR agonist SNC-80 bound at the orthosteric site [52]. During these simulations, BMS-986187 adopts multiple metastable binding states, with the two most stable and energetically equivalent ones shown in Figure 2C. While representative structures of these states have the 2-methyl benzyl group interacting similarly with the receptor, they show different orientations of the ligand’s fused tricyclic group within a binding pocket of DOR. Functional assays conducted at the wild-type and selected mutants of DOR helped us validate the predicted binding pocket by assessing the contribution of selected DOR residues (e.g., Y56(1.39)A, Q105(2.60)A, K108(2.63)A, K108(2.63)N, Y109(2.64)A, Y109(2.64)I, W284(6.58)K, L300(7.35)W, H301(7.36)R, and H301(7.36)Y) to the affinity of BMS-986187 and its ability to allosterically modulate the binding and/or the efficacy of the orthosteric agonist SNC-80. Among the tested mutants, Q105(2.60)A, Y109(2.64)I, W284(6.58)K, L300(7.35)W, and H301(7.36)Y were shown to reduce BMS-986187 binding affinity (KB) with respect to the wild-type receptor, supporting the predicted direct or water-mediated ligand-receptor interactions seen during simulations. The pronounced effect of W284(6.58)K and L300(7.35)W on the affinity and efficacy of SNC-80 is in line with the hypothesized direct receptor interactions with the orthosteric ligand (see [52] for details).

Notably, the L300(7.35)W mutation also displayed a significant increase in the functional cooperativity between BMS-986187 and SNC-80 as did K108(2.63)N, while H301(7.36)R affected binding cooperativity. Moreover, the experimental data gave higher support to one predicted binding state (yellow color in Figure 2C) over the other, although they could not unambiguously discriminate between them. Notwithstanding obvious differences in the binding of TRV130 and kurkinorin to MOR, there are similarities as well that would be interesting to compare with the ligand-receptor interactions of other G-protein biased ligands.

5. Receptor conformational changes induced by a G protein-biased opioid ligand vs. a classical opioid ligand

To identify possible differences in the receptor dynamics induced by a G protein-biased agonist (e.g., TRV130) compared to a classical opioid drug (e.g., morphine), we recently carried out a Markov State Model (MSM) analysis of close to half millisecond MD simulations of MOR bound to either ligand [58]. Specifically, we applied a high-throughput molecular dynamics (HTMD) adaptive sampling protocol [59] consisting of running thousands of simulations in sequential batches, and increasing exploration of under-sampled regions of the system’s conformational space by starting new simulations guided by MSMs derived from previous batches. Dynamic and kinetic signatures of biased agonism at MOR emerged from these simulations which would be interesting to verify against other G protein-biased ligands.

To begin, we learned that in opioid receptor systems the equivalent interaction to the TM3-TM6 salt bridge in other GPCRs, i.e., the MOR’s R1653.50 T2796.34 hydrogen bond, is broken in both the morphine-bound and the TRV130-bound inactive or activated MOR systems. We also discovered two distinct intermediate metastable regions with a different number of kinetic macrostates in the morphine-bound and TRV130-bound MOR systems in addition to activated and inactive conformations of MOR. The interest in these intermediate macrostates, which contain dynamics signatures of functional selectivity, stems from their possible value in in silico campaigns to discover improved therapeutics. Moreover, since published simulations of the β2-adrenergic receptor (β2AR) deactivation [60] and ligand-free M2 muscarinic receptor (M2R) activation [61] had identified only one of these two intermediate metastable regions, it is tempting to speculate that the two identified intermediate macrostates along the activation pathway of MOR may be specific to opioid receptors or perhaps only dependent on the exhaustive conformational sampling achieved by our study. Notably, although multiple activation/deactivation pathways between inactive and active states of the receptor were identified for both morphine-bound and TRV-130-bound MOR systems, most transitions occurred through only one of these two intermediate states, with a transition to the inactive state of the receptor happening faster for the morphine-bound MOR system compared to the TRV130-bound MOR system.

Another interesting observation of our recent study [58] is that the most probable kinetic macrostates of MOR bound to either a classical or G protein-biased ligand, resemble an inactive state of the receptor. This is in line with the observation that binding of G protein mimetics is required for full MOR activation and the lack of these agents in our simulations, may have affected the outcome. Notably, the slowest dynamic motions recorded in the morphine-bound and TRV130-bound MOR systems are substantially different. While the cytoplasmic ends of TM6, TM3, and TM5 are the only regions contributing significantly to slowest motions in the morphine-bound MOR system, residues spread across different regions of the receptor are involved in the slow dynamics of TRV130-bound MOR. Thus, the G protein-biased ligand TRV-130 and the classical opioid ligand morphine appear to affect the allosteric communication across MOR differently, making the transfer of information across the receptor more pronounced in the presence of TRV-130, than morphine.

A number of residues were identified as receivers, transmitters, or connectors of this information, providing testable hypotheses of how to modulate ligand bias and/or affect the allosteric coupling between different regions of MOR. Notably, simulations of the TRV-130-bound MOR system revealed a larger number of key transmitters, receivers, or connectors at specific regions of the receptor (e.g., a larger number of transmitters at the intracellular end of TM6) compared to the morphine-bound MOR system. Some of the TM6 residues identified as transmitters in the TRV-130-bound MOR system were connectors in the morphine-bound MOR system, supporting their involvement in aspects of functional selectivity. Similarly, residues surrounding the ligand-binding pocket that were connectors in the TRV-130-bound, but not the morphine-bound MOR system (e.g., W3187.35 and Y3267.43), were suggested to control ligand bias at MOR, as was also proven experimentally [62]. Other residues that belonged to different groups in the TRV-130-bound and morphine-bound MOR systems were the Na+-coordinating residue N1503.35 and the so-called toggle switch residue W2936.48. Indeed, mutation of N1503.35 was proven to modulate agonist binding in DOR as well as to enhance β-arrestin constitutive activity [63]. As per the W2936.48 residue, its sidechain was found to be very flexible in several TRV-130-bound MOR kinetic macrostates, but not in the kinetic macrostates characterized for the morphine-bound MOR system. Finally, the most novel aspect of our recently published study on MOR [58] pertains to considerations of the time scale required by an active-like MOR conformation to transition to an inactive-like structure in the presence of either ligand. In rough agreement with NMR estimates of microseconds to low milliseconds for MOR bound to an agonist [64], our calculated transition time scales of MOR bound to TRV130 or morphine was of the order of tens of microseconds, with rearrangements of the receptor intracellular regions involved in the slowest motions, as also seen in recently published NMR experiments of MOR [64]. Interestingly, the time-limiting conformational changes in the morphine-bound MOR system, but not in the TRV-130-bound receptor, corresponded to the rearrangement of the intra-helical H-bonding network at the intracellular end of TM6, rather than the larger outward movement of TM6 relative to TM3.

However, the calculated timescales for ligand-induced MOR activation (tens of microseconds) are faster than experimental ones derived from intramolecular FRET studies of prototypic GPCRs [65, 66] (i.e., tens of milliseconds). This observation suggests that the slowest degrees of freedom in opioid receptor activation are other than the receptor conformational changes that precede or accompany interactions with intracellular partners.

6. Conclusions

Given that we are currently facing the deadliest drug overdose crisis in American history, the discovery of potent analgesics with reduced side effects, especially respiratory depression, with respect to classical opioid drugs remains the main focus of several research laboratories. The availability of high-resolution structural information on opioid receptors as well as insights from several different biophysical, biochemical, and pharmacological methods, including MD simulations offer unprecedented opportunities for opioid research. Interesting new trends in the development of improved therapeutics, including allosteric modulators and G protein-biased agonists, have emerged which hold a great potential as likely candidates to better drugs. However, the fine details underlying their molecular mechanisms are largely unknown. A more concerted effort involving structural biologists, computational and experimental biophysicists, molecular biologists, and pharmacologists will eventually be necessary to develop better therapeutics for chronic pain. As computer architectures, force-field parameterizations, and big data analysis platforms and tools continue to improve the characterization of key metastable conformational states, as well as important thermodynamics and kinetics properties, molecular dynamics simulations will more effectively contribute unique insights into open questions related to ligand binding, activation, and oligomerization of opioid receptors towards the development of better opioid drugs.

Highlights.

Misuse or accidental use of opioids have recently resulted in a very serious public health crisis

Non-addictive medications for chronic pain are desperately needed to stop the opioid epidemics

Attention has recently shifted towards opioid allosteric modulators and G protein-biased opioid agonists as likely candidates to combat the opioid crisis.

Understanding how opioid allosteric modulators and G protein-biased opioid agonists bind and activate their receptors at an atomistic level is key to developing them into effective new therapeutics

Molecular dynamics-based strategies contribute unique information to the development of improved therapeutics.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Dr. Davide Provasi and Dr. Abhijeet Kapoor in the Filizola lab for providing material to make the figures included in this manuscript, as well as to Ms. Suzanne Small for editorial assistance. Computations described in this manuscript were run on resources available through the Scientific Computing Facility at Mount Sinai, and the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment under MCB080077, which is supported by National Science Foundation grant number ACI-1053575.

Funding Sources

Work on opioids in the Filizola lab is supported by National Institutes of Health grants DA026434, DA034049 and DA038882.

Footnotes

Competing Interests Statement

No competing interests to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Tomassoni A, Hawk K, Jubanyik K, Nogee DP, Durant T, Lynch KL, Patel R, Dinh D, Ulrich A, D’Onofrio G. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep; Multiple Fentanyl Overdoses; New Haven, Connecticut. June 23, 2016; 2017. pp. 107–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, Scholl L. Increases in Drug and Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths — United States, 2010–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:1445–1452. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm655051e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fairbairn N, Coffin PO, Walley AY. Naloxone for heroin, prescription opioid, and illicitly made fentanyl overdoses: Challenges and innovations responding to a dynamic epidemic. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;46:172–179. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Volkow ND, Collins FS. The Role of Science in Addressing the Opioid Crisis. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:391–394. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1706626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pasternak GW, Snyder SH. Identification of novel high affinity opiate receptor binding in rat brain. Nature. 1975;253:563–565. doi: 10.1038/253563a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pert CB, Pasternak G, Snyder SH. Opiate agonists and antagonists discriminated by receptor binding in brain. Science. 1973;182:1359–1361. doi: 10.1126/science.182.4119.1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Livingston KE, Traynor JR. Allostery at opioid receptors: modulation with small molecule ligands. Br J Pharmacol. 2017 doi: 10.1111/bph.13823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burford NT, Clark MJ, Wehrman TS, Gerritz SW, Banks M, O’Connell J, Traynor JR, Alt A. Discovery of positive allosteric modulators and silent allosteric modulators of the mu-opioid receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:10830–10835. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1300393110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bisignano P, Burford NT, Shang Y, Marlow B, Livingston KE, Fenton AM, Rockwell K, Budenholzer L, Traynor J, Gerritz SW, Alt A, Filizola M. Ligand-Based Discovery of a New Scaffold for Allosteric Modulation of the mu-Opioid Receptor. Journal of Chemical Information & Modeling. 2015;55:1836–1843. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.5b00388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burford N, Livingston K, Canals M, Ryan M, Budenholzer L, Han Y, Shang Y, Herbst J, O’Connell J, Banks M, Zhang L, Filizola M, Bassoni D, Wehrman T, Christopoulos A, Traynor J, Gerritz SW, Alt A. Discovery Synthesis and Molecular Pharmacology of Selective Positive Allosteric Modulators of the δ-Opioid Receptor. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2015;58:4220–4229. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kathmann M, Flau K, Redmer A, Trankle C, Schlicker E. Cannabidiol is an allosteric modulator at mu- and delta-opioid receptors. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2006;372:354–361. doi: 10.1007/s00210-006-0033-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rothman RB, Murphy DL, Xu H, Godin JA, Dersch CM, Partilla JS, Tidgewell K, Schmidt M, Prisinzano TE. Salvinorin A: allosteric interactions at the mu-opioid receptor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;320:801–810. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.113167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohbuchi K, Miyagi C, Suzuki Y, Mizuhara Y, Mizuno K, Omiya Y, Yamamoto M, Warabi E, Sudo Y, Yokoyama A, Miyano K, Hirokawa T, Uezono Y. Ignavine: a novel allosteric modulator of the mu opioid receptor. Sci Rep. 2016;6:31748. doi: 10.1038/srep31748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fawzi AB, Macdonald D, Benbow LL, Smith-Torhan A, Zhang H, Weig BC, Ho G, Tulshian D, Linder ME, Graziano MP. SCH-202676: An allosteric modulator of both agonist and antagonist binding to G protein-coupled receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;59:30–37. doi: 10.1124/mol.59.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goblyos A, de Vries H, Brussee J, Ijzerman AP. Synthesis and biological evaluation of a new series of 2,3,5-substituted [1,2,4]-thiadiazoles as modulators of adenosine A1 receptors and their molecular mechanism of action. J Med Chem. 2005;48:1145–1151. doi: 10.1021/jm049337s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewandowicz AM, Vepsalainen J, Laitinen JT. The ‘allosteric modulator’ SCH-202676 disrupts G protein-coupled receptor function via sulphydryl-sensitive mechanisms. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;147:422–429. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keov P, Sexton PM, Christopoulos A. Allosteric modulation of G protein-coupled receptors: a pharmacological perspective. Neuropharmacology. 2011;60:24–35. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wootten D, Savage EE, Valant C, May LT, Sloop KW, Ficorilli J, Showalter AD, Willard FS, Christopoulos A, Sexton PM. Allosteric modulation of endogenous metabolites as an avenue for drug discovery. Mol Pharmacol. 2012;82:281–290. doi: 10.1124/mol.112.079319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kenakin T. New concepts in drug discovery: collateral efficacy and permissive antagonism. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4:919–927. doi: 10.1038/nrd1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kenakin T. Collateral efficacy in drug discovery: taking advantage of the good (allosteric) nature of 7TM receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28:407–415. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kenakin T. Biased agonism. F1000 Biol Rep. 2009;1:87. doi: 10.3410/B1-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mailman RB. GPCR functional selectivity has therapeutic impact. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28:390–396. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Urban JD, Clarke WP, von Zastrow M, Nichols DE, Kobilka B, Weinstein H, Javitch JA, Roth BL, Christopoulos A, Sexton PM, Miller KJ, Spedding M, Mailman RB. Functional selectivity and classical concepts of quantitative pharmacology. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;320:1–13. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.104463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bohn LM. Selectivity for G protein or arrestin-mediated signaling. In: NK, editor. Functional Selectivity of G Protein-Coupled Receptor Ligands. Humana Press; Totowa, NJ: 2009. pp. 71–85. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kieffer BL. Opioids: first lessons from knockout mice. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1999;20:19–26. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(98)01279-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bohn LM, Lefkowitz RJ, Gainetdinov RR, Peppel K, Caron MG, Lin FT. Enhanced morphine analgesia in mice lacking beta-arrestin 2. Science. 1999;286:2495–2498. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5449.2495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raehal KM, Walker JK, Bohn LM. Morphine side effects in beta-arrestin 2 knockout mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;314:1195–1201. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.087254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maguma HT, Dewey WL, Akbarali HI. Differences in the characteristics of tolerance to μ-opioid receptor agonists in the colon from wild type and β-arrestin2 knockout mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2012;685:133–140. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DeWire SM, Yamashita DS, Rominger DH, Liu G, Cowan CL, Graczyk TM, Chen XT, Pitis PM, Gotchev D, Yuan C, Koblish M, Lark MW, Violin JD. A G protein-biased ligand at the mu-opioid receptor is potently analgesic with reduced gastrointestinal and respiratory dysfunction compared with morphine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2013;344:708–717. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.201616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crowley R, Riley A, Sherwood A, Shivaperumal N, Groer C, Biscaia M, Paton K, Schneider S, Provasi D, Kivell B, Filizola M, Prisinzano TE. Synthetic Studies of Neoclerodane Diterpenes from Salvia divinorum: Identification of a Potent and Centrally Acting μ Opioid Analgesic with Reduced Abuse Liability. J Med Chem. 2016 doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu H, Partilla JS, Wang X, Rutherford JM, Tidgewell K, Prisinzano TE, Bohn LM, Rothman RB. A comparison of noninternalizing (herkinorin) and internalizing (DAMGO) mu-opioid agonists on cellular markers related to opioid tolerance and dependence. Synapse. 2007;61:166–175. doi: 10.1002/syn.20356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lamb K, Tidgewell K, Simpson DS, Bohn LM, Prisinzano TE. Antinociceptive effects of herkinorin, a MOP receptor agonist derived from salvinorin A in the formalin test in rats: new concepts in mu opioid receptor pharmacology: from a symposium on new concepts in mu-opioid pharmacology. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;121:181–188. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manglik A, Lin H, Aryal DK, McCorvy JD, Dengler D, Corder G, Levit A, Kling RC, Bernat V, Hubner H, Huang XP, Sassano MF, Giguere PM, Lober S, Da D, Scherrer G, Kobilka BK, Gmeiner P, Roth BL, Shoichet BK. Structure-based discovery of opioid analgesics with reduced side effects. Nature. 2016;537:185–190. doi: 10.1038/nature19112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kruegel AC, Gassaway MM, Kapoor A, Varadi A, Majumdar S, Filizola M, Javitch JA, Sames D. Synthetic and Receptor Signaling Explorations of the Mitragyna Alkaloids: Mitragynine as an Atypical Molecular Framework for Opioid Receptor Modulators. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:6754–6764. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b00360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Varadi A, Marrone GF, Palmer TC, Narayan A, Szabo MR, Le Rouzic V, Grinnell SG, Subrath JJ, Warner E, Kalra S, Hunkele A, Pagirsky J, Eans SO, Medina JM, Xu J, Pan YX, Borics A, Pasternak GW, McLaughlin JP, Majumdar S. Mitragynine/Corynantheidine Pseudoindoxyls As Opioid Analgesics with Mu Agonism and Delta Antagonism, Which Do Not Recruit beta-Arrestin-2. J Med Chem. 2016;59:8381–8397. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Broom DC, Nitsche JF, Pintar JE, Rice KC, Woods JH, Traynor JR. Comparison of receptor mechanisms and efficacy requirements for delta-agonist-induced convulsive activity and antinociception in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;303:723–729. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.036525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou L, Lovell KM, Frankowski KJ, Slauson SR, Phillips AM, Streicher JM, Stahl E, Schmid CL, Hodder P, Madoux F, Cameron MD, Prisinzano TE, Aube J, Bohn LM. Development of functionally selective, small molecule agonists at kappa opioid receptors. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:36703–36716. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.504381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brust TF, Morgenweck J, Kim SA, Rose JH, Locke JL, Schmid CL, Zhou L, Stahl EL, Cameron MD, Scarry SM, Aube J, Jones SR, Martin TJ, Bohn LM. Biased agonists of the kappa opioid receptor suppress pain and itch without causing sedation or dysphoria. Sci Signal. 2016;9:ra117. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aai8441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martin T, Kim S, Rose J, Jones S, Aube J, Bohn L. (361) A novel G-protein biased kappa opioid that displays analgesic but not dysphoric actions in the rat. J Pain. 2016;17:S65. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Viscusi ER, Webster L, Kuss M, Daniels S, Bolognese JA, Zuckerman S, Soergel DG, Subach RA, Cook E, Skobieranda F. A randomized, phase 2 study investigating TRV130, a biased ligand of the μ-opioid receptor, for the intravenous treatment of acute pain. Pain. 2016;157:264–272. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Singla N, Minkowitz HS, Soergel DG, Burt DA, Subach RA, Salamea MY, Fossler MJ, Skobieranda F. A randomized, Phase IIb study investigating oliceridine (TRV130), a novel micro-receptor G-protein pathway selective (mu-GPS) modulator, for the management of moderate to severe acute pain following abdominoplasty. J Pain Res. 2017;10:2413–2424. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S137952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.http://www.trevena.com/trevena-pipeline.php.

- 43.Manglik A, Kruse AC, Kobilka TS, Thian FS, Mathiesen JM, Sunahara RK, Pardo L, Weis WI, Kobilka BK, Granier S. Crystal structure of the micro-opioid receptor bound to a morphinan antagonist. Nature. 2012;485:321–326. doi: 10.1038/nature10954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Granier S, Manglik A, Kruse AC, Kobilka TS, Thian FS, Weis WI, Kobilka BK. Structure of the delta-opioid receptor bound to naltrindole. Nature. 2012;485:400–404. doi: 10.1038/nature11111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fenalti G, Giguere PM, Katritch V, Huang XP, Thompson AA, Cherezov V, Roth BL, Stevens RC. Molecular control of delta-opioid receptor signalling. Nature. 2014;506:191–196. doi: 10.1038/nature12944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fenalti G, Zatsepin NA, Betti C, Giguere P, Han GW, Ishchenko A, Liu W, Guillemyn K, Zhang H, James D, Wang D, Weierstall U, Spence JC, Boutet S, Messerschmidt M, Williams GJ, Gati C, Yefanov OM, White TA, Oberthuer D, Metz M, Yoon CH, Barty A, Chapman HN, Basu S, Coe J, Conrad CE, Fromme R, Fromme P, Tourwe D, Schiller PW, Roth BL, Ballet S, Katritch V, Stevens RC, Cherezov V. Structural basis for bifunctional peptide recognition at human delta-opioid receptor. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2015;22:265–268. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu H, Wacker D, Mileni M, Katritch V, Han GW, Vardy E, Liu W, Thompson AA, Huang XP, Carroll FI, Mascarella SW, Westkaemper RB, Mosier PD, Roth BL, Cherezov V, Stevens RC. Structure of the human kappa-opioid receptor in complex with JDTic. Nature. 2012;485:327–332. doi: 10.1038/nature10939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thompson AA, Liu W, Chun E, Katritch V, Wu H, Vardy E, Huang XP, Trapella C, Guerrini R, Calo G, Roth BL, Cherezov V, Stevens RC. Structure of the nociceptin/orphanin FQ receptor in complex with a peptide mimetic. Nature. 2012;485:395–399. doi: 10.1038/nature11085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang W, Manglik A, Venkatakrishnan AJ, Laeremans T, Feinberg EN, Sanborn AL, Kato HE, Livingston KE, Thorsen TS, Kling RC, Granier S, Gmeiner P, Husbands SM, Traynor JR, Weis WI, Steyaert J, Dror RO, Kobilka BK. Structural insights into mu-opioid receptor activation. Nature. 2015;524:315–321. doi: 10.1038/nature14886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Che T, Majumdar S, Zaidi SA, Ondachi P, McCorvy JD, Wang S, Mosier PD, Uprety R, Vardy E, Krumm BE, Han GW, Lee MY, Pardon E, Steyaert J, Huang XP, Strachan RT, Tribo AR, Pasternak GW, Carroll FI, Stevens RC, Cherezov V, Katritch V, Wacker D, Roth BL. Structure of the Nanobody-Stabilized Active State of the Kappa Opioid Receptor. Cell. 2018;172:55–67. e15. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schneider S, Provasi D, Filizola M. Binding Pathways of a G-Protein Biased μ-opioid Receptor agonist under Clinical Evaluation. Biophysical Journal. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.1011.3155. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shang Y, Yeatman HR, Provasi D, Alt A, Christopoulos A, Canals M, Filizola M. Proposed Mode of Binding and Action of Positive Allosteric Modulators at Opioid Receptors. ACS Chemical Biology. 2016 doi: 10.1021/acschembio.5b00712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Provasi D, Bortolato A, Filizola M. Exploring Molecular Mechanisms of Ligand Recognition by Opioid Receptors with Metadynamics. Biochemistry. 2009;48:10020–10029. doi: 10.1021/bi901494n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Provasi D, Filizola M. Putative Active States of a Prototypic G-Protein-Coupled Receptor from Biased Molecular Dynamics. Biophysical Journal. 2010;98:2347–2355. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.01.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Johnston JM, Aburi M, Provasi D, Bortolato A, Urizar E, Lambert NA, Javitch JA, Filizola M. Making Structural Sense of Dimerization Interfaces of Delta Opioid Receptor Homodimers. Biochemistry. 2011 doi: 10.1021/bi101474v. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Saleh N, Ibrahim P, Saladino G, Gervasio FL, Clark T. An Efficient Metadynamics-Based Protocol To Model the Binding Affinity and the Transition State Ensemble of G-Protein-Coupled Receptor Ligands. J Chem Inf Model. 2017;57:1210–1217. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.6b00772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Granier S, Kobilka B. A new era of GPCR structural and chemical biology. Nature chemical biology. 2012;8:670–673. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kapoor A, Martinez-Rosell G, Provasi D, de Fabritiis G, Filizola M. Dynamic and Kinetic Elements of micro-Opioid Receptor Functional Selectivity. Sci Rep. 2017;7:11255. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-11483-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Doerr S, Harvey MJ, Noe F, De Fabritiis G. HTMD: High-Throughput Molecular Dynamics for Molecular Discovery. J Chem Theory Comput. 2016;12:1845–1852. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.6b00049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dror RO, Arlow DH, Maragakis P, Mildorf TJ, Pan AC, Xu H, Borhani DW, Shaw DE. Activation mechanism of the β2-adrenergic receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:18684–18689. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110499108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Miao Y, Nichols SE, Gasper PM, Metzger VT, McCammon JA. Activation and dynamic network of the M2 muscarinic receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:10982–10987. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1309755110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hothersall JD, Torella R, Humphreys S, Hooley M, Brown A, McMurray G, Nickolls SA. Residues W320 and Y328 within the binding site of the μ-opioid receptor influence opiate ligand bias. Neuropharmacology. 2017;118:46–58. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fenalti G, Giguere PM, Katritch V, Huang XP, Thompson AA, Cherezov V, Roth BL, Stevens RC. Molecular control of δ-opioid receptor signalling. Nature. 2014;506:191–196. doi: 10.1038/nature12944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sounier R, Mas C, Steyaert J, Laeremans T, Manglik A, Huang W, Kobilka BK, Déméné H, Granier S. Propagation of conformational changes during μ-opioid receptor activation. Nature. 2015;524:375–378. doi: 10.1038/nature14680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vilardaga JP, Bünemann M, Krasel C, Castro M, Lohse MJ. Measurement of the millisecond activation switch of G protein-coupled receptors in living cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:807–812. doi: 10.1038/nbt838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hoffmann C, Gaietta G, Bünemann M, Adams SR, Oberdorff-Maass S, Behr B, Vilardaga JP, Tsien RY, Ellisman MH, Lohse MJ. A FlAsH-based FRET approach to determine G protein-coupled receptor activation in living cells. Nat Methods. 2005;2:171–176. doi: 10.1038/nmeth742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]