Abstract

The effect of some sugars (maltose, sucrose, and d-allulose) on different starch sources (normal corn, normal rice, waxy corn and waxy rice) to produce edible film was studied. Films were prepared using 3% (w/w) starch and 20% (w/w) sugar as a plasticizer. The relative crystallinity of films increased with addition of sugars and extended storage. The thickness of films was increased with addition of sugar. The morphology of films surface became homogeneous with sugars. Sugars decreased breaking stress and increased breaking strain immediately after preparation and during storage. The flow behavior of all the starch film suspensions showed shear-thinning properties determined using the Power law model. The apparent viscosity of the suspensions changed during the drying process resulting from the added sugar and starch type. Adding sugar as a plasticizer showed different effects on the crystallization, the thickness, the morphology of the film surface, the mechanical properties of the film and the flow behavior during drying. Both types of sugar and starch that could interact and inhibited starch chain mobility due to size of sugar, hydroxyl group, and hydrogen bond.

Keywords: Starch, Sugar, Film, Plasticizer

Introduction

Plastic is the most common material used for food packaging to help protect food or retard food spoilage. Presently, the amount of plastic used is increasing and waste from food wrapping or food containers has exceeded a million tons per year (Espitia et al. 2014). There have been many studies on materials to replace plastic as food packaging. Accordingly, biodegradable and edible films are of interest.

Starch is one of the most common materials used for producing biodegradable and edible films because of its low cost and various properties. Edible films have different base materials with different properties, such as elongation, tensile strength, and the ability to act as an oxygen and vapor barrier (Bourtoom 2008; Dhanapal et al. 2012; Tongdeesoontorn et al. 2011). Edible films must have suitable physical, mechanical, and rheological properties, but some types of starch do not have suitable properties for film. Thus, plasticizers have been studied as an additive to improve the properties of edible film because plasticizer reduced interactions between starch molecules and render film more flexible (Dias et al. 2010; Espitia et al. 2014; Ghasemlou et al. 2013; Skurty et al. 2010; Zhang and Han 2006).

Sugar is food additive that affects to the physical properties of food during processing to the finished product and after storage. Sugars such as sucrose and maltose are known to affect on rheological properties and recrystallization (Smits et al. 2003; Yoo and Yoo 2005). The effect of sucrose on the starch system has been shown in previous studies. Sucrose inhibits retrogradation, increases breaking strain and has a higher plasticizing effect, compared with sorbitol and glycerol (Souza et al. 2012; Veiga-Santos et al. 2007; Yoo and Yoo 2005). Maltose and sucrose have also been shown to be more effective in decreasing breaking stress compared with glucose and fructose during storage because sugar disrupts starch chains interaction and thus prevent recrystallization (Smits et al. 2003).

d-allulose is one type of rare sugar that is beneficial to health (lower calories, beneficial to blood glucose levels, inhibits body fat accumulation) and also improves the processing characteristics of food (Ikeda et al. 2014; O’Charoen et al. 2014). O’Charoen et al. (2014) found that adding D-psicose to meringue increases breaking stress and breaking strain. Moreover, Ikeda et al. (2014) showed that d-allulose can decrease gelatinization enthalpy; the degree of retrogradation in rice flour cake with d-allulose was less than that in rice flour cake without sugar and with sucrose. However, the effect of sugar as a plasticizer on the physical properties of film are related to the type of sugar, which interacts with starch in the system, and the source of starch (Chang et al. 2004; Ploypetchara et al. 2015; Zhang and Han 2006). The effect of plasticizer on the flow behavior of the starch system before the drying process has been shown in many previous studies (Chang et al. 2004; Yoo and Yoo 2005) whereas the change in flow behavior during the drying process has been little studied. Moreover, the relationship between the mechanical properties and characteristics of starch film with added sugar was unclear.

Thus, the aim of this study was to examine the rheological, crystallization and the morphology effect of sugar type on different starch sources during film preparation and after storage to produce edible film.

Materials and methods

Materials

Starch samples used in this study were normal corn starch, normal rice starch, waxy corn starch and waxy rice starch (Matsutani Company Limited, Japan). Sugars used as plasticizer were maltose, sucrose (Nacalai Tesque, Inc., Kyoto, Japan) and d-allulose (Kagawa Rare Sugar Cluster, Kagawa, Japan).

Film suspension preparation and film formation

Film suspensions were prepared by adding starch 3% (w/w) in pure water as a control and 20% plasticizer (maltose, sucrose, and d-allulose) (w/w of starch weight) and stirring for 30 min. After that, the samples were heated at 95 °C for 30 min in a water bath. The suspensions were then cooled to room temperature to investigate flow characteristics. Films were prepared from the film suspensions by drying 8 g of film suspension in Petri dishes (7.7 cm diameter). The film suspensions were dried at 50 °C in a drying oven (SANYO, Japan) for around 5 h and the dried films were maintained at 25 °C overnight before removing from the Petri dishes. The film samples were stored within plastic bags under dry atmosphere by silica gel in desiccators at 25 °C until measurement (Rodríguez et al. 2006; Sanyang et al. 2015).

Film crystallinity

X-ray diffraction patterns of the starch films were determined by using Nano-viewer (Rigaku, Japan) equipped with a PILATUS at an applied voltage and filament current of 40 kV and 30 mA, respectively. The wavelength of the radiation source was 0.154 nm. The diffraction angle (2θ) was from 0 to 27°. Crystallinity of film was evaluated with relative crystallinity (%) calculated as follows:

| 1 |

where If is the integral of crystalline area of film sample on the X-ray diffraction (peak at 15, 17, 18, 20 and 23°) and Is is the integral of crystalline area of raw starch sample on the X-ray diffraction (Primo-Martín et al. 2007). The crystalline area was estimated with Igor Pro software (Multi-peak Fit version 2.0).

Film thickness

Film thickness was determined with a micrometer (Niigata Seiki, Japan) and thicknesses at 10 random positions of the film were averaged (Rodríguez et al. 2006).

Film morphology

Film morphology was measured with scanning electron microscope (SEM). Starch film samples were mounted on sample holders using double-side sticky tape. The sample was coated with Pt–Pd by a magnetron sputter coater (MSP-1S, Vacuum Device Inc., Tokyo, Japan) and observed using JEOL JSM-6060 Scanning electron microscope (Jeol Lid., Japan) with LM mode at 5 kV accelerating voltage. Surface micrograph were present at 500× magnification (Gómez-Luría et al. 2017).

Mechanical properties

Breaking stress and breaking strain were determined using a Rheoner II Creep meter RE2-33005B (Yamaden, Japan) with a 20 N load cell. Film samples were cut to 5 mm width and 15 mm length and subjected to a tensile test at a crosshead speed of 1 mm/s (Saberi et al. 2016). The breaking stress and breaking strain of the film samples were measured on the day of preparation (day 0), and after 7 and 28 days.

Flow behavior of the film suspensions

Flow behavior of the film suspensions was investigated in the samples after becoming gelatinized and after drying at 50 °C in an oven for 3 h. Samples were measured using a Viscometer (Toki Sangyo Co., Ltd., Japan) using a 1°34′ × R24 cone at 25 °C and operated between a shear rate of 3.830 (s−1) and 76.60 (s−1) to investigate shear stress and viscosity in Time-Independent behavior. The low behavior of the film suspensions was calculated with using the Power Law model equation:

| 2 |

where τ is the shear stress (Pa), k is the consistency index, n is the flow behavior index, and γ is the shear rate s−1 (Abdou and Sorour 2014).

Statistical analysis

All the samples were analyzed statistically using SPSS version 17. Different means were investigated by one-way analysis of variance and Duncan’s multiple range tests at a level of significance of 0.05. Correlation of variables was determined using Pearson Bivariate Correlations at the 0.01 and 0.05 significance levels.

Results and discussion

Film crystallinity

The X-ray diffraction pattern of the normal starch film showed a peak at 15, 17, 18, 20 and 23° (Table 1), whereas the waxy starch film showed less relative crystallinity than the normal starch on the day of preparation and during storage time. Normal crystallization of film depended on the level of amylose dissolution and on the number of hydrogen bonds built within the film because the crystallization of amylose was faster than amylopectin due to amylose network formation in the high amylose matrix, which produced a strong physical crosslink by hydrogen bonding (Shah et al. 2015; Van Soest and Vliegenthart 1997).

Table 1.

Relative crystallinity and thickness of starch film with and without added sugar

*Different letters in the same column within each starch indicates significant difference at p ≤ 0.05

During the preparation period, crystallinity increased more in the starch film with the added sugar because increased macromolecular mobility can form microcrystalline junctions and recrystallization (Apriyana et al. 2016). Table 1 shows relative crystallinity with d-allulose at 0 and 28 days tends to be lowest for all starch films with sugar.

Sugar acts as an effective plasticizer but makes film more brittle because of changes in hydrogen bond network and in matrix mobility through the interaction between water and plasticizer (Ploypetchara et al. 2015; Shah et al. 2015). However, d-allulose might inhibit recrystallization in starch film unlike maltose and sucrose. Ikeda et al. (2014) found that d-allulose can decrease recrystallization of starch owing to re-association with starch. A lower amount of unbound water of sucrose than of d-allulose could increase re-association with starch, more so than with d-allulose. The OH groups of sugar inhibit recrystallization by interaction with polymeric chains because of interference in the alignment of the polymer chains by steric hindrance (Apriyana et al. 2016). A smaller sugar is easy to move and crystallizes with the remaining structure nucleation of starch by starch chain mobility, whereas some larger plasticizers penetrate the starch chain and prevent re-crystallization (Apriyana et al. 2016; Smits et al. 2003).

Apriyana et al. (2016) found that crystallinity decreases after 8 weeks’ storage in sugar palm starch film, which contains a high concentration of glycerol (50%), because the film absorbed more water from the environment by the hydrophilic film matrix, the single helical structure in film matrix decreased after storage, and the interaction of amylose and water was increased then inhibited glycerol to form complex with amylose. However, recrystallization depends on many variables such as the amylose/amylopectin ratio of starch, temperature during storage time, and the type and concentration of additive (Chang et al. 2004; Ploypetchara et al. 2015).

Film thickness

The effect of sugars on starch film thickness is shown in Table 1. All the starch films with added sugar were thicker compared with the films without added sugar. The increase in thickness may be due to the occurrence of particles or an increase in the size of the particles. It is presumed that the particles were produced by the recrystallization of starch. Apriyana et al. (2016) and Hafnimardiyanti and Armin (2016) reported that film thickness increased with increasing total solid content in the film suspension due to increased residual mass in the film. As shown in Table 1, the waxy rice starch film was thinner than waxy corn starch film. Film thickness increases with increasing particle size as shown with the corn starch film, which has increased stiffness whereas rice starch, which has a smaller particle size, is required for very thin film (Chiu and Solark 2009; Jane et al. 1992).

The effect of d-allulose on thickening the starch films was lower than the effect of the other sugars as shown in Table 1. The less low effect of d-allulose may be attributed to the low recrystallization of starch as previously described. The thickness of the starch films with added sucrose and maltose increased more than the films with added d-allulose because of the higher molecular weight of the plasticizer (180.16, 342.30 and 360.31 g/mol for d-allulose, sucrose, and m2011altose, respectively). The lower molecular weight monosaccharides were closely packed in the polymer chain matrix leading to a thinner film (Piermaria et al. 2011). This may be due to the presence of lower amount of d-allulose in the system than maltose and sucrose, similar to the results of Zhang and Han (2006) who found that glycerol-plasticized starch film was the thinnest compared with glucose, fructose, and mannose due to lower solid content (plasticizer + starch). Further investigation is required to determine the role of particle size in starch film.

Film morphology

The surface morphology of films shown in Fig. 1 The morphology results presented homogeneous and smooth with sugar addition in all types of starch due to plasticizing mechanism and smaller molecule compared with the amylose–amylopectin chains (Dias et al. 2010). Starch film with d-allulose appeared more compact and denser structure than that with maltose and sucrose addition. These results were related to mechanical properties shown in Fig. 2 that starch film with d-allulose indicated higher breaking strain than that with maltose and sucrose. Saberi et al. (2017) reported that surface of pea starch-guar gum film with polyethylene glycol and sucrose was rougher than that with glucose; the film containing with low molecular weight plasticizer would show more compact, homogeneous, and denser structure than that with high molecular weight structure. The good indicator of integrity film structure was homogeneous of film matrix that would be expected for good mechanical property (Dias et al. 2010).

Fig. 1.

Surface of starch film with and without added sugar from SEM. Number letter: 1 = normal corn, 2 = normal rice, 3 = waxy corn and 4 = waxy rice. Small letter: a = without sugar, b = added maltose, c = added sucrose and d = added d-allulose

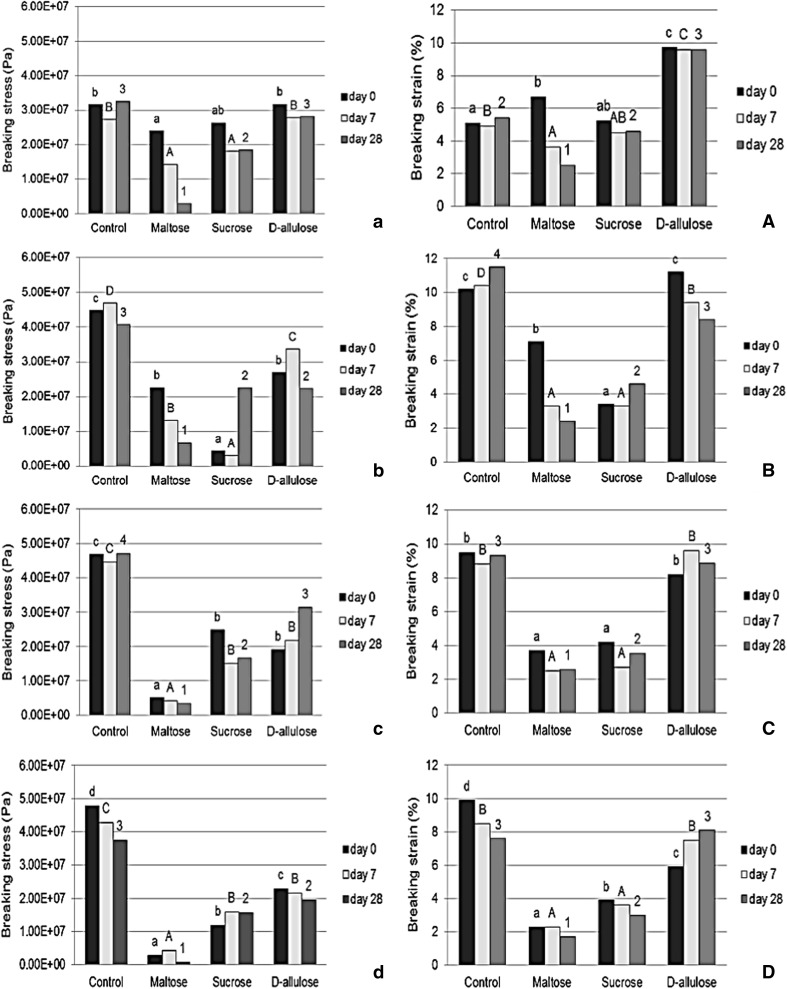

Fig. 2.

Breaking stress of starch film with and without added sugar (left): a = normal corn, b = normal rice, c = waxy corn and d = waxy rice, and breaking strain (right): A = normal corn, B = normal rice, C = waxy corn and D = waxy rice. *Different small letters in each column indicates difference at 0 day, significant difference at p≤0.05. **Different capital letters in each column indicates difference at 7 days, significant difference at p≤0.05. ***Different number letters in each column indicates difference at 28 day significant difference at p≤0.05

Mechanical properties

Figure 2 shows that all the starch films with added sugar had lower breaking stress. This was similar to the results of Apriyana et al. (2016) and Sanyang et al. (2015) who found that tensile strength decreased with increasing plasticizer concentration, which was related to a reduction in strength of the intramolecular starch chain attraction and increased hydrogen bond formation between the plasticizer and starch. The breaking stress showed a negative relationship with film thickness (the correlation coefficient is more than − 0.5 as shown in Table 2) in that thickness increased while breaking stress decreased. After 28 days, the breaking stress of the starch films with added sugar remained lower than the control films of all the starches.

Table 2.

Correlation coefficient between properties of starch films

| n | k | thickness | Crystal0 | Crystal7 | Crystal28 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Starch type | − 0.742** | 0.881** | 0.231 | − 0.518* | − 0.603* | − 0.620* |

| n | 1 | − 0.964** | 0.082 | 0.526* | 0.557* | 0.641** |

| k | − 0.964** | 1 | 0.016 | − 0.559* | − 0.635** | − 0.685** |

| Bstress0 | 0.201 | − 0.235 | − 0.575* | 0.101 | 0.224 | 0.214 |

| Bstress7 | 0.044 | − 0.014 | − 0.749** | − 0.248 | − 0.297 | − 0.186 |

| Bstress28 | 0.382 | − 0.394 | − 0.488 | − 0.117 | − 0.022 | 0.006 |

| Bstrain0 | 0.262 | − 0.206 | − 0.513* | − 0.053 | − 0.078 | 0.007 |

| Bstrain7 | 0.123 | − 0.091 | − 0.627** | − 0.267 | − 0.230 | − 0.178 |

| Bstrain28 | 0.171 | − 0.143 | − 0.617* | − 0.293 | − 0.204 | − 0.168 |

n = flow behavior index after becoming gelatinized; k = consistency index after becoming gelatinized; Bstress = breaking stress; Bstrain = breaking strain; crystal = relative crystallinity. The number shown after each treatment indicates storage time (preparation day, 7 days, and 28 days). * and ** indicate the correlation is significant at the 0.05 and 0.01 levels (two-tailed), respectively

The decrease in breaking stress was related to plasticizer, which attracts water molecules. Plasticizers can reduce the force of inter- and intramolecular interaction between starch molecules and increase starch polymer chain mobility to increase flexibility and extensibility of film (Souza et al. 2012; Veiga-Santos et al. 2007; Zhang and Han 2006). Sugars reduced the breaking stress of the starch films more than control during storage time. In particular, maltose and sucrose decreased breaking stress more than d-allulose because of the number of hydroxyl (OH) groups, which has the important role of hydration ability in sugar (Kawai et al. 1992). The number of OH groups and/or the size of the molecules of sucrose and maltose compared with that of d-allulose could affect the stabilization of water surrounding the sugar molecule and as a result retard the reorder of starch polymer chains during storage time (Chang et al. 2004; Souza et al. 2012).

The breaking strain of the normal corn starch film increased with added d-allulose as a plasticizer because of the decreased interaction between amylose, amylopectin, and amylose–amylopectin in the starch system caused by the hydrogen bonds between d-allulose and starch. The decreased breaking strain with maltose and sucrose might be attributed to the strong interaction between sugar and starch, which could inhibit the mobility of macromolecules and weaken the interaction between starch polymers, and so that cohesive force of polymer chains would decrease (Sanyang et al. 2015). The results showed a decrease in breaking stress and an increase in breaking strain when d-allulose was added might be related to film thickness and film morphology. The thickness of the starch films with added d-allulose was significantly different to the film with added maltose and sucrose.

Flow behavior of the film suspensions

Flow behavior, a one of rheological properties, is important to process evaluation, process control and consumer acceptability of food products. The flow behavior of blending film suspension affects the edible coating film formation and mechanical properties (Abdou and Sorour 2014). The flow behaviors of the suspensions in the present study were calculated using the Power Law model, achieving similar results to those Yoo and Yoo (2005) who showed that a rice starch–sucrose composite was a non-Newtonian fluid with shear-thinning behavior pseudo-plastic fluid as n was less than 1, for which the disruption rate of existing intermolecular entanglement changed to higher than the reformation rate of intermolecular entanglement with increasing shear rate, leading to the low resistance to flow. The linkage between molecules could break down during shearing by hydrodynamic force (Rao 1999).

The flow curves of the starch film suspensions after gelatinization were not clearly distinct between the suspensions with and without sugar (Fig. 3I) for every system in the study. After drying for 3 h (Fig. 3II), the starch suspensions were very thick and showed a different flow behavior characteristic affected by the added sugar. The flow behavior index (n) of the starch suspensions after being dried for 3 h tended to increase with added sugar in rice starch (Table 3) similar to Yoo and Yoo (2005) in rice starch–sucrose composites. From the results, consistency index (k) of normal starch suspension was less than waxy starch suspension after gelatinization but k of normal starch more increased than waxy starch after dried 3 h. Consistency index and apparent viscosity increased by the presence of insoluble solids. In starch-based system, the viscosity was changed by structural due to irreversible swelling of starch granules and amylose leaching out from the amorphous region during gelatinization (Nascimento et al. 2012). Moreover, consistency index of waxy starch suspension after dried 3 h increased with sugar addition. This corresponded to the report of Nascimento et al. (2012) who found the consistency index increased when clay nanoparticle incorporated with mesocarp passion fruit flour film solution. Abu-Jdayil et al. (2004) found that the consistency index increased with increase in sugar concentration in a wheat starch paste system. The increased flow behavior index with increasing sugar concentration was due to a lowering of shear-thinning behavior. Adding sugar caused a decrease in the rate of initial conformation double helix formation (Chang et al. 2004). Flow behavior was a result of the sugar-plasticized effect caused by sugar penetration in the starch system, which produced disorder inside the starch granules that may be related to film process preparation, plasticizer type and concentration, and sugar type and concentration (Abu-Jdayil et al. 2004; Liu et al. 2009).

Fig. 3.

Flow behavior (I) and apparent viscosity (III) of starch film suspensions after becoming gelatinized: a = normal corn, b = normal rice, c = waxy corn and d = waxy rice. Flow behavior (II) and apparent viscosity of starch film suspensions after dried for 3 h (IV): A = normal corn, B = normal rice, C = waxy corn and D = waxy rice

Table 3.

Flow behavior index of starch film suspensions

| Starch | Normal corn | Normal rice | Waxy corn | Waxy rice | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | n | k | R2 | n | k | R2 | n | k | R2 | n | k | |

| After becoming gelatinized | ||||||||||||

| Control | 0.98 | 0.40a | 0.62bc | 0.96 | 0.50b | 0.40a | 1.00 | 0.42bc | 1.86a | 0.97 | 0.17a | 6.17c |

| Maltose | 0.95 | 0.44b | 0.60ab | 1.00 | 0.50b | 0.38a | 1.00 | 0.44c | 1.81a | 0.99 | 0.20a | 5.37b |

| Sucrose | 0.97 | 0.44b | 0.54a | 1.00 | 0.44a | 0.49b | 0.99 | 0.39a | 2.23b | 1.00 | 0.24b | 4.72a |

| d-allulose | 0.94 | 0.41ab | 0.67c | 1.00 | 0.49b | 0.37a | 1.00 | 0.41b | 1.92a | 1.00 | 0.24b | 4.73a |

| After drying for 3 h | ||||||||||||

| Control | 0.98 | 0.38AB | 24.84C | 1.000 | 0.27A | 35.92AB | 1.00 | 0.40AB | 8.19A | 0.99 | 0.23A | 19.03A |

| Maltose | 0.99 | 0.39AB | 13.76A | 1.00 | 0.29A | 41.83B | 1.00 | 0.39A | 9.15A | 0.99 | 0.26B | 23.51B |

| Sucrose | 0.99 | 0.36A | 22.39C | 1.00 | 0.29A | 29.58A | 1.00 | 0.41AB | 9.13A | 0.99 | 0.26B | 23.62B |

| d-allulose | 0.97 | 0.342B | 17.44B | 1.00 | 0.32B | 31.07A | 1.00 | 0.42B | 9.40A | 0.99 | 0.25B | 23.04B |

*Different small letters in the same column within each starch after becoming gelatinized indicates significant difference at p≤0.05

**Different capital letters in the same column within each starch after drying 3 h indicates significant difference at p≤0.05

Apparent viscosity

The apparent viscosity of the suspensions measured after becoming gelatinized and drying for 3 h are shown in Fig. 3III, IV, respectively. The normal corn starch suspension with maltose and d-allulose had decreased apparent viscosity after being dried for 3 h, whereas the normal rice starch suspension with maltose had increased apparent viscosity. The interaction of starch molecule and sugar would form by sugar-bridge between hydroxyl group of sugar and starch in amorphous region (Spies and Hoseney 1982). The structure of starch is composed of α-D-glucopyranose unit in which each glucose unit has three hydroxyl group positions that could interact with another molecule. The hydroxyl group of sugar would interact with starch by hydrogen bond. The hydroxyl group of sugar was effectively to substitute for water molecule, reducing starch granule swelling and granule breakdown (Ploypetchara et al. 2015). Thus, viscosity of starch suspension would decrease when sugar addition. Van Soest and Vliegenthart (1997) reported that the network of formation was composed of polymer–polymer and polymer–sugar interaction through hydrogen bonds and van der Waals forces, while breaking and melting of starch granule would be resulted by plasticizer content and process operation. Saberi et al. (2016) reported similar results with glycerol added to a pea starch suspension resulting in decreased apparent viscosity because the added plasticizer was incorporated in the polysaccharide network through competition for hydrogen bonds between the starch–starch chains and starch-plasticizer. The plasticizer leads to a reduction in network rigidity.

Chang et al. (2004) who found the viscosity of bulk water around sugar increased with the decreasing motion of stabilized water in the starch–water system and the motion of starch chain was inhibited. On the other hand, the apparent viscosity of the waxy starch suspension tended to increase with addition of sugar in the sample after drying for 3 h. This behavior might be influenced by the sugar and starch structure that inhibited starch chain mobility in the amorphous region to reorganize and result in sugar–starch interaction. This interaction may have prevented chain reordering and decreased viscosity by the equatorial hydroxyl groups, whereas the axial hydroxyl groups showed the opposite effect (Abu-Jdayil et al. 2004; Ploypetchara et al. 2015).

Correlation between properties of the starch films

A summary of the Pearson Bivariate Correlation of flow behavior properties, mechanical properties, relative crystallinity, and thickness of the starch films with and without added sugars is shown in Table 2. The flow behavior index and consistency index after becoming gelatinized correlated with starch type. The thickness of the starch films correlated with the mechanical properties (breaking stress and breaking strain) of the films during storage time. The negative correlation of thickness with the mechanical properties showed that addition of sugar increased thickness and decreased breaking stress. Suitable condition could be necessary as a plasticizer to the film such as type and concentration of starch, and type and concentration of sugar that interacts with starch (Chang et al. 2004; Piermaria et al. 2011; Ploypetchara et al. 2015; Sanyang et al. 2015; Shah et al. 2015; Zhang and Han 2006).

Conclusion

Mechanical properties of films prepared using various starches and sugars were investigated. Crystallization was more pronounced by adding sugar and by storage. Sugar could be homogeneous and miscible with starch film. Added sugar decreased breaking stress during storage time when maltose, sucrose, and d-allulose were used as plasticizers. The results of flow behavior showed shear-thinning properties as determined by the Power law model, and flow behavior was more clearly different during the drying process. The apparent viscosity of the waxy starch suspension tended to increase with added sugar in the sample in which sugar interaction inhibited starch chain mobility in the amorphous region. The effect of sugars as plasticizers on the properties of the starch films was related to both the type of starch and type of sugar. Moreover, adding sugar had an important effect on the mechanical properties, which need to be further investigated.

Contributor Information

Thongkorn Ploypetchara, Email: mo_2u@hotmail.com.

Shoichi Gohtani, Phone: +81878 913103, Email: gohtani@ag.kagawa-u.ac.jp.

References

- Abdou ES, Sorour MA. Preparation and characterization of starch/carrageenan edible film. IFRJ. 2014;2(1):189–193. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Jdayil B, Mohameed HA, Eassa A. Rheology of wheat starch-milk-sugar systems: effect of starch concentration, sugar type and concentration, and milk fat content. J Food Eng. 2004;64:207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2003.09.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Apriyana W, Poeloengasih CD, Hernawan, Hayati SN, Pranoto Y (2016) Mechanical and microstructural properties of sugar palm (Arenga pinnata Merr.) starch film: effect of aging. In: AIP conference proceedings 1755:150003

- Bourtoom T. Edible film and coating: characteristics and properties. IFRJ. 2008;15(3):237–248. [Google Scholar]

- Chang YH, Lim ST, Yoo B. Dynamic rheology of corn starch-sugar composite. J Food Eng. 2004;64:521–527. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2003.08.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu C, Solark D. Starch: chemistry and technology. Chapter 17: modification of starches. 3. Cambridge: Academic Press; 2009. p. 640. [Google Scholar]

- Dhanapal A, Sasikala P, Rajamani L, Kavitha V, Yazhini G, Bana MS. Edible films from polysaccharides. Food Sci Qual Manag. 2012;3:9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Dias AB, Muller CMO, Larotonda FDS, Laurindo JB. Biodegradable films based on rice starch and rice flour. J Cereal Sci. 2010;51:213–219. doi: 10.1016/j.jcs.2009.11.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Espitia PJP, Du WX, Avena-Bustillos RDJ, Soares NDFF, McHugh TH. Edible films from pectin: physical-mechanical and antimicrobial properties—a review. Food Hydrocoll. 2014;35:287–296. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2013.06.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghasemlou M, Aliheidari N, Fahmi R, Shojaee-Aliabadi S, Keshavarz B, Cran MJ, Khaksar R. Physical, mechanical and barrier properties of corn starch films incorporated with plant essential oils. Carbohydr Polym. 2013;98:1117–1126. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Luría D, Vernon-Carter EJ, AlvarezRamirez J. Films from corn, wheat, and rice starch ghost phase fractions display overall superior performance than whole starch films. Starch/Stärke. 2017;69:1–11. doi: 10.1002/star.201700059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hafnimardiyanti H, Armin MI. Effect of plasticizer on physical and mechanical characteristics of edible film from mocaf flour. Der Phamacia Lettre. 2016;8(19):301–308. [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda S, Furuta C, Fujita Y, Gohtani S. Effects of D-psicose on gelatinization and retrogradation of rice flour. Starch/Stärke. 2014;66:773–779. doi: 10.1002/star.201300259. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jane J, Shen L, Wang L, Manigat CC. Preparation and properties of small-particle corn starch. Cereal Chem. 1992;69(3):280–283. [Google Scholar]

- Kawai H, Sakurai M, Inoue Y, Chûjô R, Kobayashi S. Hydration of oligosaccharides: anomalous hydration ability of trehalose. Cryobiology. 1992;29:599–606. doi: 10.1016/0011-2240(92)90064-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Xie F, Yu L, Chen L, Li L. Thermal processing of starch based polymers. Prog Polym Sci. 2009;34:1348–1368. doi: 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2009.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento TA, Calado V, Carvalho CWP. Development and characterization of flexible film based on starch and passion fruit mesocarp flour with nanoparticles. Food Res Int. 2012;49:588–595. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2012.07.051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Charoen S, Hayakawa S, Matsumoto Y, Ogawa M. Effect of D-psicose used as sucrose replacer on the characteristics of meringue. JFS. 2014;79:E2463–E2469. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.12699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piermaria J, Bosch A, Pinotti A, Yantorno O, Garcia MA, Abraham AG. Kefiran films plasticized with sugar and polyol: water vapor barrier and mechanical properties in relation to their microstructure analyzed by ATR/FT-IR spectroscopy. Food Hydrocoll. 2011;25:1261–1269. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2010.11.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ploypetchara T, Suwannaporn S, Pechyen C, Gohtani S. Retrogradation of rice flour gel and dough: plasticization effects of some food additives. Cereal Chem. 2015;92(2):198–203. doi: 10.1094/CCHEM-07-14-0165-R. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Primo-Martín C, van Nieuwenhuijzen NH, Hamer RJ, van Vliet T. Crystallinity changes in wheat starch during the bread-making process: starch crystallinity in the bread crust. J Cereal Sci. 2007;45:219–226. doi: 10.1016/j.jcs.2006.08.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rao MA. Rheology of fluid and semisolid foods principles and applications. Chapter 2 flow and functional models for rheological properties of fluid foods. Gaithersburg: Aspen Publishers, Inc.; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez M, Osés J, Ziani K, Maté JI. Combined effect of plasticizers and surfactants on the physical properties of starch based edible films. Food Res Int. 2006;39:840–846. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2006.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saberi B, Vuong QV, Chockchaisawasdee S, Golding JB, Scarlett CJ, Stathopoulos CE. Mechanical and physical properties of pea starch edible films in the presence of glycerol. J Food Process Preserv. 2016;40(6):1339–1351. doi: 10.1111/jfpp.12719. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saberi B, Chockchaisawasdee S, Golding JB, Scarlett CJ, Stathopoulos CE. Physical and mechanical properties of a new edible film made of pea starch and guar gum as affected by glycols, sugars and polyols. Int J Biol Macromol. 2017;104:345–359. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.06.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanyang ML, Sapuan SM, Jawaid M, Ishak MR, Sahari J. Effect of plasticizer type and concentration on tensile, thermal and barrier properties of biodegradable films based on sugar plam (Arenga pinnata) starch. Polymer. 2015;7:1106–1124. doi: 10.3390/polym7061106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah U, Gani A, Ashwar BA, Shah A, Ahmad M, Gani A, Wani IA, Masoodi FA. A review of the recent advances in starch as active and nanocomposite packaging films. Cogent Food Agric. 2015;1:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Skurty O, Acevedo A, Pedreschi F, Enrione J, Osorio F, Aguilera JM. Food hydrocolloid edible films and coatings. New York: Nova-Science Publishers; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Smits ALM, Kruiskamp PH, van Soest JJG, Vliegenthart JFG. The influence of various small plasticisers and malto-oligosaccharides on the retrogradation of (partly) gelatinized starch. Carbohydr Polym. 2003;51:417–424. doi: 10.1016/S0144-8617(02)00206-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Souza AC, Benze R, Ferrão ES, Ditchfield C, Coelho ACV, Tadini CC. Cassava starch biodegradable films: influence of glycerol and clay nanoparticles content on tensile and barrier properties and glass transition temperature. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2012;46:110–117. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2011.10.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spies RD, Hoseney RC. Effect of sugars on starch gelatinization. Cereal Chem. 1982;59:128–131. [Google Scholar]

- Tongdeesoontorn W, Maues LJ, Wongruong S, Sriburi P, Rachtanapun P. Effect of carboxymethyl cellulose concentration on physical properties of biodegradable cassava starch based film. Chem Cent J. 2011;5:6. doi: 10.1186/1752-153X-5-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Soest JJG, Vliegenthart JFG. Crystallinity in starch plastics: consequences for material properties. Trends Biotechnol. 1997;15:208–212. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(97)01021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veiga-Santos P, Oliveira LM, Cereda MP, Scamparini ARP. Sucrose and invert sugar as plasticizer: effect on cassava starch gelatin film mechanical properties, hydrophilicity and water activity. Food Chem. 2007;103:255–262. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.07.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo D, Yoo B. Rheology of rice starch-sucrose composites. Starch/Stärke. 2005;57:254–261. doi: 10.1002/star.200400356. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Han JH. Mechanical and thermal characteristic of pea starch film plasticized with monosaccharides and polyols. JFS. 2006;71(2):109–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2006.tb08891.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]