Abstract

This study evaluated the effect of bambara groundnut supplementation on the physicochemical properties of local rice flour and baked crackers. Bulk and true density, porosity, water absorption index, oil absorption capacity, pasting properties by RVA, morphological appearance by SEM, color by calorimetry, and textural properties by TA.XT2 analysis of wheat and two formulations of rice–legume flours and crackers were studied. Moisture (10.94%) and carbohydrate (77.42%) levels were significantly greater in wheat flour than the rice–legume flours, while the reverse was true for fat and ash. Also rice–legume flours had significantly greater water and oil absorption capacity and lower water solubility compared to wheat flour. Compared to wheat crackers, rice–legume crackers had greater fat and ash, 20.51 and 3.57%, respectively, while moisture was significantly lower in the rice–legume crackers by 41 to 58%. Rice legume crackers were significantly harder and had significantly increased spread ratio. The results obtained from the development of locally grown rice and underutilized legume bambara groundnut showed great promise in physicochemical and functional properties and may be a good replacement for wheat flour to serve as a gluten-free product.

Keywords: Bambara groundnut, Rice, Crackers, Physicochemical properties

Introduction

Rice is considered to be the second most important grain food staple in Ghana and also ranked first among imported cereal in the country accounting for 58% of cereal imports (Sampson 2013). Rice is a non-allergenic, gluten free and source of carbohydrate, vitamins, and minerals with low fat content (Umadevi et al. 2012). The rising number of fast food restaurants and vendors in the major cities in Ghana has increased the demand for rice, therefore high quality white rice is consumed on a regular basis in urban areas where the concentration of people with a stable income is high, while local rice is left in rural areas to be consumed by farmers and their households (Aguda 2009). Ghanaian policy makers have shown great concern about the massive dependency on rice imports in the country, especially after food prices soared in 2008 (Omari et al. 2015).

Legumes serve as a good source of protein to a large proportion of the population in poor and developing countries (Chadha and Oluoch 2003). The levels of consumption of food legumes, such as bambara groundnuts, are also low in a number of developing countries, making it necessary to increase the consumption levels by incorporating them in complementary foods like snacks (Afoakwa et al. 2007). The demand and consumption rate of inexpensive ready-to-eat, convenient snacks have increased, and they are commonplace in most developing countries (Omoba et al. 2013). The development of snacks from locally grown rice and underutilized legume would add value to these crops and provide inexpensive nutritious snacks. Utilizing legumes such bambara groundnut and local rice in product development would also help improve food insecurity and increase the consumption of local products. There is sufficient evidence to suggest that improving rural agro-based activities, such as value addition of local varieties of rice cultivated in rural areas, could result in long-term sustainable reduction in poverty (FAO 2002) and provide food security in the country.

People with celiac disease are not able to consume wheat, rye and barley, because of the protein gluten found in these foods. Studies have shown that people with gluten intolerance would be able to consume this product (Okafor 2010). Rice and bambara groundnut (legume) do not contain the gluten proteins (Duodu and Apea-Bah 2017) and their usage in the production of crackers will serve as a good snack for people with celiac disease (Vivas 2013).

The development of rice-based snacks would also reduce the demand for wheat flour, which is costly due to importation, especially in developing countries (Marco and Rosell 2008). Wheat is the most common cereal used in the production of snacks such as crackers, because of its viscoelastic property that assists in sheeting and forming properties. Therefore, the objective of this research was to compare the properties of bambara groundnut supplemented rice flours and crackers to wheat flour and crackers.

Materials and methods

Materials

Rice (O. Sativa Amankwatia variety) was obtained from the Crop Research Institute (CRI), Kumasi. Bambara groundnut seeds (Vigna subterranea (L.) Verdc. variety) were purchased from the Central Market in Kumasi. The bambara groundnut and the rice were both milled into flour using a disc attrition mill (Hunt and Co, UK) and passed through a 44 mesh sieve (600 μm) to obtain a uniform size. Formulations were determined based on protein content. One formulation consisted of 9% bambara groundnut flour with 91% rice flour and was named RBG. The second formulation consisted of 18% bambara groundnut with 82% rice flour and was named HRBG. The wheat flour control and flour mixtures were prepared in triplicate and stored in sealed plastic bags at − 18 °C until further analysis. Wheat flour, salt, cheddar cheese and parmesan cheese were purchased from Walmart (USA) and kept at 0 °C until further analysis.

Proximate analyses of wheat flour and rice–bambara groundnut flours and crackers

Proximate composition of the wheat, RBG and HRBG flours were determined on a wet basis using standard AOAC methods (1995). A nitrogen factor of 6.23 was used for protein determination. Carbohydrate content was determined by subtracting moisture, protein, fat, crude fiber and ash contents from 100%. Water activity was determined on the crackers after baking using a water activity meter (OHAUS MB45 Moisture Analyzer, OHAUS, Parsippany, NJ, USA).

Bulk density of wheat flour and rice–bambara groundnut flours

Flours (3 g) were weighed into a 10 mL graduated cylinder and then the cylinder was gently tapped on a rubber sheet laden table top until there was no observed change in volume (approximately 10 times). The volume occupied by the flour was measured according to the method of Okafor (2010). The bulk density of the flour was calculated as the weight of flour per volume occupied after tapping (g/mL).

True density of wheat flour and rice–bambara groundnut flours

True density was determined by liquid displacement method. One gram of flour was weighed into a 10 mL graduated cylinder containing (5 mL) of toluene. The increase in volume was noted and true density was calculated by the following equation: true density (g/mL) = weight of the flour (g)/volume of toluene displaced by the flour (mL) (ASAE, 2001).

Porosity of wheat flour and rice–bambara groundnut flours

Percent porosity of the flours was estimated according to the method described by Adedeji and Ngadi (2011). Porosity was determined by subtracting bulk density from true density and dividing by true density then multiplying by 100.

Water absorption index (WAI) and water solubility index (WSI) of wheat flour and rice–bambara groundnut flours

WAI and WSI were determined by suspending a known mass of each flour mixture in a ratio of 1:1 flour to water for 30 min at room temperature. The suspension was gently stirred and then centrifuged (Sorvall RC6 plus, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at 3000×g at 25 °C for 15 min. The supernatants were decanted into an evaporating dish, and then heated at 65 °C in a laboratory oven for 24 h. The WSI was the weight of dry solids in the supernatant expressed as a percentage of the original sample weight. WAI was recorded as the weight of the residue obtained after removal of the supernatant per unit weight of original flours (Yağcı and Göğüş 2008) were used.

Oil absorption capacity (OAC) of wheat flour and rice–bambara groundnut flours

The oil absorption capacity was determined with slight modification to the method described by Ige et al. (1984). Centrifuge tubes (50 mL) were weighed and 2.5 g of flour mixed with 32.5 mL of refined oil were weighed into the tubes and vortexed (Vortex MaxiMix II, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) for 10 min. The tubes were centrifuged (Sorvall RC 6 plus, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) for 25 min at 3000×g at 25 °C. The oil was drained off and the centrifuge tubes were weighed. Oil absorption capacity was calculated as the difference of the final weight after centrifuging and the initial weight of the sample and expressed as grams of oil absorbed per 100 g of original flour.

Foaming capacity and stability

Foaming capacity (FC) and foam stability (FS) were determined according to Narayana and Rao (1982). Two grams of flour of each formulation were weighed and added into 50 mL of distilled water at room temperature, followed by mixing with a vortexer (MaxiMix II, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) for 45 s. The volume of the foam was recorded after 30 s and FC was expressed as percentage increase in volume. The foam volume after 1 h was used to determine FS.

Pasting properties of wheat flour and rice–bambara groundnut flours

Pasting properties were determined for wheat flour and rice–bambara groundnut flours using a Rapid Visco Analyzer (RVA Tecmaster, Perten, Australia) following AACCI Method 61-02.01. An aqueous dispersion of 3 g of each flour in 25 mL deionized water was equilibrated for 1 min at 50 °C, heated at the rate of 12.2 °C/min to 95 °C and held at 95 °C for 2.5 min. The sample was cooled to 50 °C and held for about 2 min. The samples were stirred at 160 rpm during the RVA analysis. Pasting parameters were determined by the RVA program.

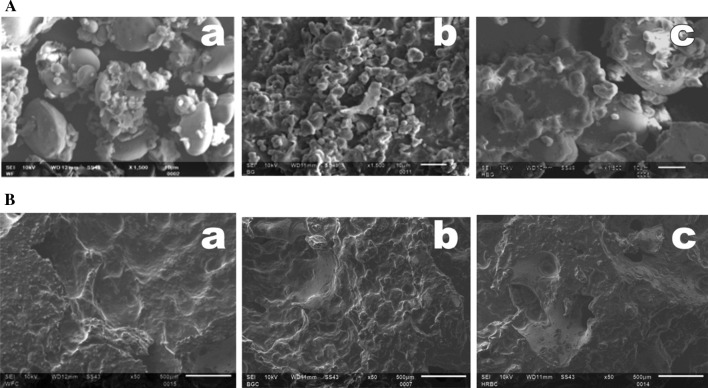

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) of flours and crackers

All three flours and the inner integral part of the crackers were mounted on aluminum SEM stubs and coated with argon in an Edwards S150 sputter coater at an accelerating potential of 10 kV. The samples were examined under scanning electron microscope JSM-6610LM (JEOL Ltd, Akishima, Tokyo, Japan) at magnification of 1500 × for the flour samples and 50 × for cracker images.

Cracker formulation and preparation

Crackers were prepared starting with an online recipe (“Food wishes,” 2013) with slight modifications. The temperature and time of cooking were optimized based on similarity of properties of the mixed flour crackers (RBGC—9% bambara groundnut flour with 91% rice flour cracker and HRBGC—18% bambara groundnut flour with 82% rice flour cracker) to the wheat flour cracker (WFC). Fifty seven grams of wheat flour or rice–bambara groundnut flours, 32 g of unsalted butter mixed with 62 g of grated cheddar cheese, 23 g of parmesan cheese and 0.16 g of salt were mixed and 10 mL of cold water was added to form dough. Dough weighs of each formulation were controlled. The dough was kept at 4 °C for 30 min, after which it was kneaded and sheeted to a uniform thickness of 0.30 cm and cut into rectangular shapes. They were baked in an oven at 370 °C for 15 min. Crackers were allowed to cool before being packaged into sealed zip-lock bags and held for further analysis. For each formulation crackers were prepared in triplicate.

Physical properties of crackers

The weight, diameter, thickness, spread ratio and hardness were measured using the method of Cheng and Bhat (2016). Four crackers (n = 4) were randomly selected from each formulation and weighed. They were placed next to one another and the measurement of the total diameter was recorded using a Vernier caliper. All crackers were rotated by 90° and the new diameter was recorded, the average of both diameters were divided by four and recorded as the average diameter of the cracker. Thickness was measured by stacking the four crackers one on top of the other, then they were restacked four times and the average height was recorded as the thickness. The measurements for the diameter and thickness were used to determine the spread ratio of the crackers by diameter/thickness. The hardness of the crackers was measured with a texture analyzer (TA.XT Plus, Stable Micro Systems, Godalming, Surrey, UK) using a sharp cutting blade probe. Hardness and maximum peak force were measured with eight crackers for each sample. The peak force used in snapping the crackers was reported as fracture force in N. The surface color of the crackers was measured on the basis of CIE-L*a*b* color space system was carried out using a Hunterlab Colorimeter fitted with optical sensor (Hunter Associates Laboratory Inc., Reston, VA, USA). Five crackers were measured for each of triplicate analyses. L* represents lightness, and a* (red/green) and b* (blue/yellow) represent chromaticity units. The colorimeter was calibrated with a standard white plate.

Statistical analysis

Results obtained were tabulated into Microsoft Excel 2010 and the data was exported to Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS version 20, 2011). The data were subjected to one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the significance differences among the means were determined with Tukey’s post hoc test. p values ≥ 0.05 were considered as statistically not significant. All analyses were done in triplicate.

Results and discussion

The proximate composition of wheat flour and the two formulated rice–legume flour mixtures are shown in Table 1. The moisture contents of the flours were 10.94, 9.40 and 9.60% for WFC, RBG and HRBG, respectively. Wheat flour protein content (9.85%) was similar to that reported by Ribotta et al. (2005). Rice flour typically has a very low protein content of 6.7% as reported by others (Umadevi et al. 2012). The protein content for the rice–legume flour mixtures was 2.1 to 2.7% greater than that reported for rice alone due to the addition of the bambara groundnut which typically has a protein content range of 17–24% (Kiin-Kabari et al. 2015). The fat content of bambara groundnut is about 7.90% as reported by Madukwe et al. (2013), whereas rice flour has a fat content ranging from 0.5 to 3.5%. The rice–legume formulated flours had greater fat and ash content as compared to wheat flour, and both increased with an increase in bambara groundnut percentage. Therefore the greater fat content of the rice–legume flours mixtures, 7.9 to 9%, may likely be due to the addition of bambara groundnut (Table 1). The higher ash content in rice–bambara groundnut flour implies that it contains relatively greater mineral content, which could be attributed to the bambara groundnut flour as it is known to have high values for ash content. Similar results were reported by Yousif and Safaa (2014) where rice flour had lower ash content compared to chickpea and sweet flour. Bambara groundnut and chickpea flour have been reported to have greater nutritional value than wheat flour due to greater protein and iron levels (Madukwe et al. 2013). This is also in agreement with research done by Kohajdová et al. (2013) on pea flour.

Table 1.

Proximate composition of Rice and bambara groundnut mixture flours and wheat flour on a wet basis

| Parameters % | Samples | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| WF | RBG | HRBG | |

| Moisture | 10.94a ± 0.007 | 9.40b ± 0.035 | 9.60c ± 0.042 |

| Protein | 9.85a ± 0.070 | 8.81a ± 0.212 | 9.38a ± 0.042 |

| Fat | 1.02a ± 0.057 | 7.89b ± 0.283 | 9.01c ± 0.035 |

| Crude Fiber | 0.39a ± 0.007 | 0.43a ± 0.057 | 0.51a ± 0.035 |

| Ash | 0.40a ± 0.014 | 0.63b ± 0.018 | 0.87c ± 0.021 |

| Carbohydrate | 77.42a ± 0.813 | 72.85b ± 0.354 | 70.65b ± 0.021 |

Data reported as mean ± standard deviation of triplicate analysis. Means values in the same row with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05)

Functional properties of legume flour and cereal flour mixed with legume flour are regarded as very important parameters to consider in food product development due to their effects on texture and mouth feel as well as the consistency of the product (Bhat and Yahya 2014). Understanding some of these intrinsic behaviors helps in setting the parameters for producing different products (Rahman et al. 2011). The results of the functional properties of the three flours used in this study are given in Table 2. The bulk density of wheat flour and the two formulated rice–legume flours were similar at 0.70, 0.78 and 0.74 g/mL, respectively although RBG had significantly greater bulk density than the other two flours. Determining the bulk density of flours and flour blends is important for consumer expectation of a filled package as well as for shipping purposes (Kaletunc and Breslauer 2003). RBG, HRBG and wheat flour had similar true density values. Porosity, WSI, foaming capacity and foaming stability were greater for wheat flour than RBG and HRBG. Water and oil binding capacity of flours depend on intrinsic factors, such as amino acid composition, protein conformation and surface polarity (Kaushal et al. 2012). Water absorption of a food product is said to be the maximum amount of water the product absorbs or the increased volume of the starch after swelling in excess water (Kaushal et al. 2012). WAI was greater for the RBG and HRBG than wheat flour. Fats help to retain flavor in foods and increase the mouthfeel of the foods. For oil absorption capacity (OAC) there is physical entrapment of the oil within the protein as well as hydrophobic interaction (Lawal and Adebowale 2004). RBG and HRBG had greater OAC than wheat flour (p < 0.05), implying that bambara groundnut had greater hydrophobic protein content since the protein levels of all flours were not statistically different (Table 3).

Table 2.

Functional properties of rice and bambara groundnut mixture flours and wheat flour

| Functional properties | WF | RBG | HRBG |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bulk density (g/mL) | 0.70a ± 0.025 | 0.78b ± 0.012 | 0.74a ± 0.021 |

| True density (g/mL) | 1.42a ± 0.029 | 1.44a ± 0.004 | 1.44a ± 0.008 |

| Porosity (%) | 50.37a ± 0.013 | 45.67b ± 0.007 | 48.81a ± 0.012 |

| Water absorption index (g/g) | 2.11a ± 0.014 | 3.11b ± 0.053 | 3.04b ± 0.024 |

| Water solubility index (g/100 g) | 3.98a ± 0.120 | 2.45b ± 0.110 | 3.23c ± 0.053 |

| Oil absorption capacity (g/100 g) | 2.31a ± 0.044 | 3.29b ± 0.033 | 3.04b ± 0.108 |

| Foaming capacity (%) | 18.67a ± 0.155 | 7.33b ± 0.155 | 7.33b ± 0.155 |

| Foaming stability (%) | 6.67a ± 0.005 | 3.33b ± 0.105 | 2.00b ± 0.001 |

Data reported as mean ± standard deviation of triplicate analysis. Means values in the same row with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05). WF—wheat flour, RBG—9% rice bambara groundnut blend, HRBG—18% rice bambara groundnut blend

Table 3.

Pasting properties of wheat flour and rice–bambara groundnut flours

| Parameter | WF | RBG | HRBG |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peak viscosity (cP) | 1596.50a ± 16.50 | 2021.50b ± 24.50 | 2552.50c ± 3.50 |

| Trough viscosity (cP) | 832.00a ± 1.00 | 1714.00b ± 10.00 | 1412.00c ± 15.00 |

| Break down (cP) | 833.50a ± 3.54 | 755.00b ± 2.83 | 544.50c ± 4.95 |

| Final viscosity (cP) | 1871.00a ± 1.41 | 3429.00b ± 12.73 | 3180.00c ± 5.66 |

| Setback (cP) | 1046.00a ± 9.89 | 1686.50b ± 13.44 | 1698.00b ± 15.56 |

| Pasting temperature (°C) | 83.25a ± 0.000 | 77.90a ± 1.950 | 82.00a ± 0.40 |

Data reported as mean ± standard deviation of triplicate analysis. Means values in the same row with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05). WF—wheat flour, RBG—9% rice bambara groundnut blend, HRBG—18% rice bambara groundnut blend

Foaming capacity (FC) varied significantly between the wheat flour, 18.67%, and the rice–legume flours, 7.33%. FC was calculated as the increase in volume when mixed, implying that the proteins in wheat could hold air more readily than the proteins in bambara and rice. The very low FC recorded for the rice–legume flours could be due to inadequate electrostatic repulsions, hence, protein–protein interactions to form aggregates that are detrimental to foam formation (Chavan et al. 2001). Wheat flour had significantly (p < 0.05) greater foaming stability of 6.67% than the rice–legume flours, 2.0 to 3.3%.

Pasting temperature (PT) is the minimum temperature required to cause starch granules to rupture due to the swelling of the granule and occurs post gelatinization. Granule swelling power is determined by the rigidity of starch granules (Kaushal et al. 2012). From the results, PT values showed no significant difference among the three flours of 83.25, 77.90, and 82.00 °C for WF, RBG and HRBG, respectively. Peak viscosity (PV) showed significant difference among the three flours ranging 1596 cP for WF to 2552 cP for HRBG. The rice legume flours showed an increase in PV with an increase in bambara groundnut which was unexpected. The greater the protein content in a flour, the greater the probability of that the starch granules will become embedded within a stiff protein matrix, thereby limiting the access of the starch to water and restricting the swelling (Kaushal et al. 2012). Trough viscosity, break down, final viscosity and setback all showed significant difference (p < 0.005) between wheat flour and the rice–legume composition. Final viscosity indicating the ability of the material to form a viscous paste is largely dependent on the retrogradation of soluble amylose upon cooling. Final viscosity ranged between 1871 and 3429 cP with significant differences among the three flours, with the rice–legume flours decreasing in final viscosity with an increase in bambara supplementation. Breakdown was lower for rice–legume flour mixtures compared to wheat flour, which indicates that the addition of bambara groundnut flour stabilized the starch to shear.

The results obtained for proximate composition of wheat and rice–bambara crackers are shown in Table 4. The moisture was greater for wheat crackers which served as the control, while the ash content was lower compared to rice–legume crackers. Fat content was greater, while crude fiber was lower for HRBGC than WFC and RBGC. The increase in fat content with increase in bambara groundnut in the crackers was due to the fat content of bambara groundnut of 6.58% as reported by Rahman et al. (2011). The moisture content of the crackers ranged from 2.34 to 5.61%, which is acceptable since most freshly baked products have moisture content usually below 5% (Cauvain and Young 2009). Although the moisture contents of wheat crackers was slightly greater than 5%, while the rice–legume crackers had lower moisture levels for RBGC and HRBGC (3.29 and 2.34%). Water activity (aw) values of the freshly baked rice–legume crackers were 0.423 and 0.387 for RBGC and HRBGC, respectively, while the aw of wheat crackers was 0.573 (Table 4). These results implied that the rice–legume crackers might be more stable with longer shelf-life.

Table 4.

Proximate composition of three formulations of crackers on wet basis

| Parameters % | Samples | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| WFC | RBGC | HRBGC | |

| Moisture | 5.61a ± 0.20 | 3.29b ± 0.014 | 2.34c ± 0.03 |

| Protein | 22.01a ± 0.62 | 21.32a ± 0.40 | 22.12a ± 0.41 |

| Fat | 18.23a ± 0.001 | 18.67a ± 0.21 | 20.51b ± 0.51 |

| Crude fiber | 0.73a ± 0.28 | 0.84a ± 0.02 | 0.60b ± 0.03 |

| Ash | 3.46a ± 0.007 | 3.57b ± 0.02 | 3.55b ± 0.02 |

| Carbohydrate | 49.98a ± 0.98 | 47.68a ± 0.60 | 49.11a ± 0.19 |

| Water activity (aW) | 0.573a ± 0.000 | 0.423a ± 0.000 | 0.386a ± 0.001 |

Data reported as mean ± standard deviation of triplicate analysis. Means values in the same row with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05). WFC—wheat flour control cracker, RBGC—9% rice bambara groundnut blend cracker, HRBGC—18% rice bambara groundnut blend cracker

The spread ratio is an important factor in determining quality of baked products. The spread ratio is highly dependent on the dough viscosity (Pareyt and Delcour 2008). From the results, WFC crackers were the lightest, softest and had the lowest spread ratio compared to the rice–legume crackers (Table 5). The lower weight and hardness in WFC than the rice–legume crackers might be due to the gluten trapping air in the product. There were no significant differences in the physical parameters between RBGC and HRBGC except for thickness. HRBGC, which had the lowest moisture content, showed an expected relationship between moisture content and hardness, whereas WFC had the greatest moisture content and lowest hardness. Contrary to what Cheng and Bhat (2016) found for the relationship of higher protein content restricting spread, the crackers made with rice–legume mixture had greater spread ratio even though protein levels did not vary from the wheat control (Table 5) The gluten in the wheat flour may have helped to minimize spread ratio, in the wheat flour crackers, by creating a tighter structure through disulfide bonding. Greater fat content in the rice–legume crackers than in WFC may have also contributed to greater spread ratio by acting a lubricating agent for the batter (Hui 2008).

Table 5.

Physical and color characteristics of crackers

| Parameter | WFC | RBGC | HRBGC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (g) | 9.89a ± 0.06 | 14.78b ± 0.62 | 18.35b ± 0.73 |

| Diameter (mm) | 99.48a ± 3.89 | 130.92b ± 1.59 | 132.50b ± 5.57 |

| Thickness (mm) | 34.67a ± 1.16 | 27.67b ± 0.76 | 32.67a ± 1.52 |

| Spread ratio | 2.87a ± 0.11 | 4.73b ± 0.79 | 4.08b ± 0.49 |

| Hardness (N) | 5.16a ± 0.39 | 6.67b ± 0.75 | 7.66b ± 0.998 |

| L* | 68.58a ± 0.37 | 65.41b ± 0.54 | 63.11c ± 0.54 |

| a* | 12.16a ± 0.01 | 8.66b ± 0.28 | 8.39b ± 0.31 |

| b* | 27.21a ± 0.39 | 22.11b ± 0.31 | 21.77b ± 0.94 |

Data reported as mean ± standard deviation of triplicate analysis. Means values in the same row with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05). WFC—wheat flour control cracker, RBGC—9% rice bambara groundnut blend cracker, HRBGC—18% rice bambara groundnut blend cracker

Color is also another important parameter in determining the acceptability of crackers. The lightness (L*) values of the crackers were 68.58, 65.41 and 63.11 for WFC, RBGC and HRBGC respectively (Table 5). Wheat flour crackers had the greatest L* value implying that they wheat were lighter in color than crackers made with rice–legume mixture. Maillard browning is an important contributor to the color of baked foods. The high lysine content of legumes may promote Maillard reactions resulting in the darker color of the legume supplemented crackers (Ward et al. 1998). In terms of a* (redness) and b* (yellowness), the values ranged between 8.39 to 12.16 and 21.77 to 27.21 respectively (Table 5). The control crackers had significantly greater redness and yellowness than the two rice–legume crackers, which followed the greater lightness observed for the wheat crackers.

The morphology of the flours and crackers are shown in Fig. 1A and B, respectively. The shape of the starch granules are polygonal and angular and are more dispersed for WF and clumped for RBG (Fig. 1A). The typical starch granule size for bambara groundnut ranges between 10–35 μm (Kaptso et al. 2015). The sizes of the both formulated rice legume flours were 10 μm. Rice has smaller granule size in the range of 2.4–4.8 μm (Sodhi and Singh 2003). The granule size for the rice–legume formulation was 10 μm and could be due to the addition of the legume. However, the structure was destroyed after baking and the protein was denatured with the formation of impermeable surfaces (Fig. 1B). Figure 1B.a shows the large cavities cause by larger gas bubbles due to the strong elastic protein of gluten that can help trap gas in the dough, whereas Fig. 1B.b shows lots of smaller cavities caused by smaller gas bubbles since rice protein lacks gluten (Nammakuna et al. 2016). The remaining large cavities may be due to the protein from the bambara groundnut providing some elasticity. There are more large gas bubble cavities due to the greater level of bambara groundnut flour added (Fig. 1B.c). Bambara groundnut flour may have provided enough protein to overcome the limitations of no gluten protein in rice flour to provide more elastic structure through interactions of proteins (Nammakuna et al. 2016).

Fig. 1.

SEM images of three types of flour (A) namely, WF—100% wheat flour (a) RBG—9% bambara groundnut with 91% rice flour (b) and HRBG—18% bambara groundnut with 82% rice flour (c) and three types of crackers (B) made with the same flour composition, namely, WFC (a), RBGC (b), and HRBGC (c). Magnification was × 50. WF—wheat flour, RBG—9% rice bambara groundnut blend, HRBG—18% rice bambara groundnut blend

Conclusions

The results of all parameters analyzed for the development of baked crackers made from rice from Ghana and underutilized legume bambara groundnut holds great promise with regard to physicochemical and functional properties. Results showed comparable properties to wheat crackers in proximate and functional parameters. The reported work is expected to increase the consumption and utilization of locally grown rice and bambara groundnut. This formulation could be used as a replacement for wheat in crackers for gluten free diets.

Acknowledgements

Millicent Yeboah-Awudzi is a fellow of the Norman E. Borlaug Leadership Enhancement in Agriculture Program funded by USAID.

References

- Adedeji AA, Ngadi M. Porosity determination of deep-fat-fried coatings using pycnometer. Int J Food Sci Technol. 2011;46:1266–1275. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2011.02631.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Afoakwa EO, Budu AS, Merson AB. Application of response surface methodology for optimizing the pre-processing conditions of bambara groundnut (Voandzei subterranea) during canning. Int J Food Eng. 2007 doi: 10.1080/09637480601154277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguda ND (2009) Bringing food home: a study on the changing nature of household interaction with urban food markets in Accra, Ghana. Ph.D. Dissertation. Queen’s University, Ontario Canada

- Bhat R, Yahya N. Evaluating belinjau (Gnetum gnemon L.) seed flour quality as a base for development of novel food products and food formulations. Food Chem. 2014;156:42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.01.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauvain SP, Young LS. Bakery food manufacture and quality: water control and effects. London: Blackwell Science Ltd; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Chadha ML, Oluoch MO. Home-based vegetable gardens and other strategies to overcome micro nutrient malnutrition in developing countries. Food Nutr Agric. 2003;32:17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Chavan UD, McKenzie DB, Shahidi F. Functional properties of protein isolates from Beach Pea (Lathyrus maritimus L.) Food Chem. 2001;74:177–187. doi: 10.1016/S0308-8146(01)00123-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng YF, Bhat R. Functional, physicochemical and sensory properties of novel cookies produced by utilizing underutilized jering (Pithecellobium jiringa Jack.) legume flour. Food Biosci. 2016;14:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.fbio.2016.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duodu KG, Apea-Bah FB. African legumes: nutritional and health-promoting attributes. In: Taylor J, Awika J, editors. Gluten-free ancient grains. Cereals, pseudocereals, and legumes: sustainable, nutritious, and health-promoting foods for the 21st century. 1. Cambridge: Woodhead Publishing; 2017. pp. 223–269. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) (2002) Briefs on import surges-countries No. 5 Ghana: rice, poultry and tomato paste. https://webapps.aljazeera.net/aje/custom/2014/italiantomato/img/fao.pdf. Accessed 2 September 2017

- Hui YH. Bakery products: science and technology. Malden: Blackwell; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ige MM, Ogunsua AO, Oke OL. Functional properties of the proteins of some Nigerian oilseeds: conophor seeds and three varieties of melon seeds. J Agric Food Chem. 1984;32:822–825. doi: 10.1021/jf00124a031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaletunc G, Breslauer KJ. Calorimetry of Pre- and Post-Extruded Cereal Flours”. In: Kaletunc G, Breslauer K, editors. Characterization of cereals and flours: properties, analysis, and applications. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2003. pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Kaptso KG, Njintang YN, Goletti Nguemtchouin MM, Scher J, Hounhouigan J, Mbofung CM. Physicochemical and micro-structural properties of flours, starch and proteins from two varieties of legumes: bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea) J Food Sci Technol. 2015;52:4915–4924. doi: 10.1007/s13197-014-1580-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaushal P, Kumar V, Sharma HK. Comparative study of physico-chemical, functional, anti-nutritional and pasting properties of taro (Colocasia esculenta), rice (Oryza sativa), pegion pea (Cajanus cajan) flour and their blends. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2012;48:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2012.02.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kiin-Kabari DB, Eke-Ejiofor J, Giami SY. Functional and pasting properties of wheat/plantain flours enriched with bambara groundnut protein concentrate. Int J Food Sci Nutr Eng. 2015;5(2):75–81. [Google Scholar]

- Kohajdová Z, Karovičová J, Magala M. Rheological and qualitative characteristics of pea flour incorporated cracker biscuits. Croat J Food Sci Technol. 2013;5:11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Lawal OS, Adebowale KO. Effect of acetylation and succinylation on the solubility profile, water absorption capacity, oil absorption capacity and emulsifying properties of Mucuna bean (Mucuna pruriens) protein concentrates. Nahrung Food. 2004;48:129–136. doi: 10.1002/food.200300384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madukwe EU, Edeh RI, Obizoba IC. Nutrient and organoleptic evaluation of cereal and legume based cookies. Pak J Nutr. 2013;12:154–157. doi: 10.3923/pjn.2013.158.161. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marco C, Rosell CM. Functional and rheological properties of protein enriched gluten free composite flours. J Food Eng. 2008;88:94–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2008.01.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nammakuna N, Barringer SA, Ratanatriwong P. The effects of protein isolates and hydrocolloids complexes on dough rheology, physicochemical properties and qualities of gluten-free crackers. Food Sci Nutr. 2016;4:143–155. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayana K, Rao MSN. Functional properties of raw and heat processed winged bean (Psophocarpus tetragonolobus) flour. J Food Sci. 1982;47:1534–1538. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1982.tb04976.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Okafor NJ. Production and evaluation of extruded snacks from composite flour of bambara grounnut, Hungry rice and carrot. Nsukka: University of Nigeria,; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Omari R, Essegbey G, Ruivenkamp G. Barriers to the use of locally produced food products in Ghanaian restaurants: opportunities for investments. J Sci Res Rep. 2015;4:561–573. [Google Scholar]

- Omoba OS, Awolu OO, Olagunju AI, Akomolafe AI. optimisation of plantain-brewers’ spent grain biscuit using response surface methodology. J Sci Res Rep. 2013;2:665–681. [Google Scholar]

- Pareyt B, Delcour JA. The role of wheat flour constituents, sugar, and fat in low moisture cereal based products: a review on sugar-snap cookies. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2008;48:824–839. doi: 10.1080/10408390701719223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman A, Eltayeb SM, Ali AO, Abou-Arab AA, Abu-Salem FM. Chemical composition and functional properties of flour and protein isolate extracted from bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranean) Afr J Food Sci. 2011;5:82–90. [Google Scholar]

- Ribotta PD, Arnulphi SA, León AE, Añón MC. Effect of soybean addition on the rheological properties and breadmaking quality of wheat flour. J Sci Food Agric. 2005;85:1889–1996. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.2191. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson K. Consumer preferences and willingness to pay for locally produced rice in kumasi metropolis of Ghana. Kumasi: Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sodhi NS, Singh N. Morphological, thermal and rheological properties of starches separated from rice cultivars grown in India. Food Chem. 2003;80:99–108. doi: 10.1016/S0308-8146(02)00246-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Umadevi M, Pushpa R, Sampathkumar KP, Bhowmik D. Rice-traditional medicinal plant in India. J Pharmacogn Phytochem. 2012;1:6–12. [Google Scholar]

- Vivas MB. Development of gluten-free bread formulations. Barcelona: Autonomous University of Barcelona; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ward CDW, Resurreccion AVA, McWatters KH. Comparison of acceptance of snack chips containing cornmeal, wheat flour and cowpea meal by US and West African consumers. Food Qual Prefer. 1998;9:327–332. doi: 10.1016/S0950-3293(98)00023-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yağcı S, Göğüş F. Response surface methodology for evaluation of physical and functional properties of extruded snack foods developed from food-by-products. J Food Eng. 2008;86:122–132. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2007.09.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yousif MRG, Safaa MF. Supplementation of gluten-free bread with some germinated legumes flour. J Am Sci. 2014;1010:84–93. [Google Scholar]