Abstract

The Bully-Sexual Violence Pathway theory has indicated that bullying perpetration predicts sexual violence perpetration among males and females over time in middle school, and that homophobic name-calling perpetration moderates that association among males. In this study, the Bully-Sexual Violence Pathway theory was tested across early to late adolescence. Participants included 3549 students from four Midwestern middle schools and six high schools. Surveys were administered across six time points from Spring 2008 to Spring 2013. At baseline, the sample was 32.2% White, 46.2% African American, 5.4% Hispanic, and 10.2% other. The sample was 50.2% female. The findings reveal that late middle school homophobic name-calling perpetration increased the odds of perpetrating sexual violence in high school among early middle school bullying male and female perpetrators, while homophobic name-calling victimization decreased the odds of high school sexual violence perpetration among females. The prevention of bullying and homophobic name-calling in middle school may prevent later sexual violence perpetration.

Keywords: Bullying, Sexual violence, Homophobic name-calling, Middle school, Adolescents

Introduction

Bullying, homophobic name-calling, and sexual violence perpetration emerge during early adolescence and appear to be associated with one another both in cross-sectional and longitudinal studies (Espelage et al. 2015a; Espelage et al. 2012). These associations have been supported with the Bully-Sexual Violence Pathway theory (Espelage et al. 2012) supported by Espelage et al. (2015a), who found that bullying perpetration was a predictor of sexual violence perpetration over a two-year middle school longitudinal study. Further, the association between bullying and sexual violence was moderated by homophobic name-calling perpetration among males; the link between bullying and sexual violence for males was strongest among students who reported directing homophobic epithets at other students. However, the bully-sexual violence pathway has not been examined across later adolescence when sexual violence perpetration is more prevalent. Thus, the present study sought to replicate the Bully-Sexual Violence Pathway theory by examining homophobic name-calling perpetration as a moderator of bullying and sexual violence into high school. In addition, this study extends our understanding of the pathway by examining homophobic name-calling as a mediator of the bully-sexual violence pathway.

Definitions and Prevalence of Bullying, Homophobic Name-Calling, and Sexual Violence

Bullying is defined as recurring acts of aggression by another youth or group of youth that include abuse of power, which can be physical (e.g., hitting), verbal (e.g., name-calling), relational (e.g., social exclusion), or result in damage to property, and can happen in person or through online media (e.g., text messaging, e-mail, chats; Gladden et al. 2014; Olweus et al. 1999; Ybarra et al. 2014). Among a 2015 nationally representative sample of high school students (grades 9–12), 20.2% reported being bullied on school property in the past year (Kann et al. 2016). Also, in a recent U.S. national survey, 28–37% of 12 to 18-year-old students reported they had been bullied at school during the school year (Robers et al. 2015). A recent meta-analysis of 80 studies of prevalence of cyber and face-to-face bullying among adolescents found 34.5% were perpetrators of face-to-face bullying and 36% were victims of face-to-face traditional bullying (Modecki et al. 2014).

Homophobic name-calling is primarily understood as a form of gender-based harassment, consisting of pejorative labels or denigrating phrases aimed at youth perceived to be sexual or gender minorities (Meyer 2008). However, research demonstrates that these epithets are not only targeted toward sexual and gender minority youth, but may also be directed at heterosexual youth (Tucker et al. 2016). Bullying perpetration and homophobic name-calling are overlapping, yet distinct, forms of peer aggression (Espelage et al. 2012; Espelage et al. 2017). Homophobic name-calling (sometimes called teasing or bantering) often occurs among friends and strangers (Espelage et al. 2012; Tucker et al. 2016), and has been found to be common among middle and high school students (Kosciw and Diaz 2006). Among friends, this type of harassment or teasing may serve as a form of gender role enforcement where friends perpetrate homophobic name-calling to enforce their own status while warning others not to deviate from socially sanctioned gendered behavior. Such epithets targeted toward sexual and gender minority youth are likely used to punish and stigmatize them for having already deviated from such norms, which includes compulsory heterosexuality.

In 2015, the Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network (GLSEN) reported from a nationally representative sample of 7000 lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender (LGBT) middle and high school students that 67.4% had heard homophobic remarks like “fag” or “dyke” frequently or often, and 85.2% had been verbally harassed in the past year (Kosciw et al. 2016). Among 722 high school students (55% female, 87% white, 86% heterosexual), 66.8% had observed at least one instance of homophobic behavior in the past 30 days (Poteat and Vecho 2015). Further, because these epithets are often exchanged within peer groups, homophobic name-calling perpetration and victimization are highly correlated (r = .70; Rinehart and Espelage 2016) and often co-occur (Poteat and Espelage 2005).

Sexual violence is defined as a sexual act committed or attempted without freely given consent of the victim, including acts such as forced or alcohol/drug facilitated penetration, unwelcomed sexual touching, or non-contact acts of a sexual nature such as verbal harassment (Basile et al. 2015). Sexual harassment has also been defined legally in the educational setting to include unsolicited sexual behavior, either verbal or physical, that hinders the victim from obtaining equal education (Hill and Kearl 2011). Sexual harassment (e.g., unwelcome comments, touching, intimidation or force to do something sexual) is prevalent among youth: 56% of females and 40% of males reported sexual harassment victimization by another student between 7th and 12th grade from 2010 to 2011 (Hill and Kearl 2011), and 14% of females and 18% of males reported perpetrating sexual harassment either in-person or electronically. For the purpose of this study, we use the term sexual violence to encompass the constellation of sexually violating behaviors, including sexual harassment.

Bully-Sexual Violence Pathway Theory—Moderation by Homophobic Name-Calling

Early adolescence is a developmental period during which youth intensely explore their gender and sexual identities, with attitudes and behavior being shaped by their peer groups and larger social context. Homophobic name-calling serves, in part, to shame sexual and gender minority youth for violating gender roles, which includes compulsory heterosexuality. Among boys and young men, specifically, homophobic name-calling is a way of setting and enforcing rules for what constitutes acceptable masculinity—effectively excluding sexual minority boys and young men from the circle of “accepted, legitimate masculinities” (Phoenix et al. 2003; Slaatten et al. 2014; Stoudt 2006). Among heterosexual young men, the enforcement of hegemonic masculinity further creates an environment where sexual violence and other forms of gender-based harassment emerge and is often preceded by other forms of peer aggression (Birkett and Espelage 2015; Herek 2000; Kimmel and Mahler 2003; Poteat et al. 2011; Theodore and Basow 2000). The Bully-Sexual Violence Pathway theory (Espelage et al. 2012) provides one potential explanation by which peer aggression predicts the onset of gender-based harassment. The Bully-Sexual Violence Pathway theory posits that bullying perpetration is a precursor to gender-based harassment in the form of homophobic name-calling (Poteat and Espelage 2005) and sexual violence (Espelage et al. 2015a; Miller et al. 2013; Pellegrini 2001). Poteat and Espelage (2005, 2007) found that bullying perpetration was associated with greater use of homophobic epithets (e.g., homo, gay) directed toward other students over the middle school years. There is reason to believe that this Bully-Sexual Violence Pathway would extend to high school given the association between bullying and sexual violence in several high school studies, and increased pressure to maintain heteronormativity across this developmental time period (Poteat et al. 2012; Poteat and Rivers 2010; Poteat and Vecho 2015). In a cross-sectional study of 961 middle school students and 935 high school students, Pepler and colleagues (2006) found that students who bullied were more likely to report sexual harassment perpetration than those who did not. In a longitudinal study of 795 7th graders over three time points, Miller and colleagues (2013) found 15% of students reported involvement in bully perpetration and victimization as well as sexual harassment victimization. However, these studies did not examine homophobic name-calling as a mediating variable explaining the bully-sexual violence link. Thus, in the current study, we focused on replicating the Bully-Sexual Violence Pathway supported by Espelage et al. (2015a) by examining homophobic name-calling perpetration as a moderator of middle school bullying and high school sexual violence perpetration.

Bully-Sexual Violence Pathway Theory Extended— Mediation by Homophobic Name-Calling

It is equally plausible that involvement in homophobic name-calling, either as a victim or perpetrator, could also mediate the association between bullying in early middle school and high school sexual violence perpetration. Overlap among bullying, homophobic name-calling, and sexual violence perpetration suggests that youth who display one type of aggression (e.g., bullying) are likely to display other types (e.g., sexual violence; Basile et al. 2009), especially when these behaviors emerge as a result of maintaining gender norms including heteronormativity (Poteat et al. 2007); however, these relationships have not been tested longitudinally. Perpetrating bullying against other students might also lead to being a target of homophobic epithets, given bullying and homophobic name-calling perpetration and victimization are often co-occurring in middle school (Poteat and Espelage 2005). Poteat and colleagues (2012), in a two-year longitudinal study of homophobic name-calling, found that bullying perpetration was associated with increases in homophobic victimization across the first year of high school. Further, McMaster and colleagues (2002) found that homophobic name-calling was commonly expressed by both males and females in the 6th–8th grades, and that cross-gendered sexual harassment increased in frequency during that time. Being a target of this type of gender-based harassment, which often happens in public spaces, may lead to pressure to demonstrate one’s heterosexuality. This could take the form of sexual violence toward the opposite sex (Messerschmidt 2000; Meyer 2008; Stein 1995; Stein et al. 1993) as adolescents age into high school. The current study’s focus on the longitudinal examination of bullying, homophobic name-calling, and sexual violence across early and late adolescence represents an important next step in this area of research.

Bully-Sexual Violence Pathway—Sex Differences

The relationships among bullying, homophobic name-calling, and sexual violence perpetration appear to be stronger among males than females. Literature on the sex differences in bullying and homophobic name-calling consistently finds that males engage in these behaviors more frequently than females (McMaster et al. 2002; Poteat and DiGiovanni 2010; Slaatten et al. 2014). Adolescent males report that homophobic name-calling is one of the most serious and provocative actions used against one another (Pascoe 2007; Plummer 2001)—the seriousness of this offense then may result in violence or aggression among those youth attempting to assert their hegemonic masculinity. Poteat and Rivers (2010) explored the association between bullying roles (e.g., primary bully, assistant to bully, defender of victim, remaining uninvolved) and the use of homophobic name-calling and found that males who engaged in multiple bullying roles also reported greater homophobic name-calling. On the other hand, Poteat and Espelage (2005) found a significant association between bully perpetration and homophobic name-calling for both males and females in middle school. Poteat et al. (2012) found that bullying perpetration was associated with longitudinal increases in both homophobic name-calling perpetration and victimization among high school male students. In addition, as noted previously, the Bully-Sexual Violence Pathway was moderated by homophobic name-calling perpetration for males only (Espelage et al. 2015a). Thus, all of the analyses in the present study considered sex differences across the relationships among bullying, homophobic name-calling, and sexual violence.

Current Study

The current study replicates and extends Espelage et al. (2015a) where the Bully-Sexual Violence Pathway theory was supported; the association between bullying and sexual violence perpetration was moderated by homophobic name-calling perpetration among middle school youth. Three hypotheses are evaluated. Consistent with Espelage et al. (2015a) and the Bully-Sexual Violence Pathway theory, we first hypothesized that early middle school homophobic name-calling perpetration (grades 5–7) would moderate the association between early middle school bullying perpetration (grades 5–7) and high school sexual violence perpetration (grades 9–11), only among males (Hypothesis 1). Second, we extended the Bully-Sexual Violence Pathway theory and hypothesized that both homophobic name-calling victimization and perpetration in later middle school (grades 7–8) would mediate the relationship between early bullying perpetration (grades 5–7) and sexual violence perpetration in high school (grades 9–11) (Hypothesis 2). Third, we further extended the previous theory by estimating multi-mediator models by biological sex. That is, mediation models with both homophobic name-calling victimization and perpetration entered as the intermediary (mediating) variables between early middle school bullying perpetration and high school sexual violence perpetration, and these models were estimated for males and females, simultaneously. We hypothesized that homophobic perpetration and victimization would be significant mediators between bullying perpetration and sexual violence perpetration for males but not females (Hypothesis 3).

Methods

Participants

Participants included 3549 students from four Midwestern middle schools and six high schools. Surveys were administered across six time points including Spring/Fall 2008, Spring/Fall 2009, Spring 2010, 2012, and 2013. At baseline the sample was 32.2% White, 46.2% African American, 5.4% Hispanic, and 10.2% other. The sample was 50.2% female. At baseline, students were in 5th (4.0%), 6th (34.1%), 7th (34.2%), and 8th (27.7%) grade. In wave six, participants had become freshmen, sophomores, or juniors in high school. See Table 1 for more information on basic demographics.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Variable | M(SD) or n% N = 3549 |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Age | 12.8 (1.08) |

| Female n (%) | 1781 (50.2) |

| African-American n (%) | 1638 (46.2) |

| White n (%) | 1145 (32.2) |

| Other n (%) | 281 (7.9) |

| Hispanic n (%) | 190 (5.4) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander n (%) | 80 (2.3) |

| Mother high school education n (%) | 2484 (70.1) |

| Study variables | |

| Bullying perpetration | .473 (.340) |

| Homophobic name-calling perpetration | .827 (.563) |

| Homophobic name-calling victimization | .492 (.376) |

| Sexual violence perpetration | .101 (.108) |

Note: Mother’s education was coded as 1 = high school or below and 0 = more than high school

Procedure

Parental consent

The current study was formally announced in school newsletters, school district newsletters, and e-mails from the principals prior to the Spring of 2008. Upon receiving approval from the institutional review board (IRB) and district school board, a waiver of active consent was distributed to each parent/guardian of the students enrolled in the school. The passive consent included a letter containing information about the purpose of the study, and parents/guardians were also invited to attend information meetings held in each community. Parents/guardians who did not wish to have their child participate in the study were asked to sign the information letter and return it to the researchers.

After parents/guardians turned in these forms, it was determined that 95% of students initially participated in the study. Students were asked to consent to participate in the study through an assent procedure described on the coversheet of the survey distributed to all remaining students. Surveys were later de-identified with code numbers so researchers could track their responses over multiple time points and ensure confidentiality.

Survey administration

Students were initially informed about the nature of the study by one of the six trained research assistants, the principal investigator, or another faculty member who administered the survey. Surveys were conducted in classrooms ranging from 10 to 25 students. The survey took approximately 40–45 min to complete. Members of the research team ensured confidentiality by ensuring students were sitting far enough away from one another. The survey was administered and read aloud while students responded individually.

Because the content of the survey could be upsetting to students, researchers assured them that their participation in the study was entirely voluntary and that they could skip any question or stop participating in the survey at any time. At least one appropriately trained doctoral-level psychology student was on site to provide immediate support to any student and direct him or her to necessary services. Students were also provided the contact information of the research team to seek more information about the study. Also, students were reminded about in-school resources available to them (e.g., guidance counselors) should they feel the need to talk to someone as a result of completing the survey.

Measures

Each participant completed demographic information that included questions about his or her sex (male or female), age, grade, and race/ethnicity. For race, participants were given six options: African American (not Hispanic), Asian, White (not Hispanic), Hispanic, Native American, or Pacific Islander. Students could mark all that applied. Then, students completed questions about bullying perpetration and homophobic name-calling perpetration during middle school (first four waves) and then a sexual violence perpetration measure in high school (last two waves).

Middle school bullying perpetration

The nine-item Illinois Bully Scale (Espelage and Holt 2001) was used to assess the frequency of bullying perpetration in middle school. For example, students were asked how often in the past 30 days they engaged in each behavior (e.g., teased other students, excluded others from their group of friends, threatened to hit or hurt another student). Response options included “Never”, “1 or 2 times”, “3 or 4 times”, “5 or 6 times”, and “7 or more times” on a 5-point Likert scale (0–4). The construct validity of this scale has been supported via exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis (Espelage and Holt 2001). Higher scores indicated more self-reported bullying behaviors. The scale correlated moderately with the Youth Self-Report Aggression Scale (r = .65; Achenbach 1991), suggesting that it was somewhat unique from general aggression. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were: .86 for Wave 1, .86 for Wave 2, .84 for Wave 3, and .88 for Wave 4 perpetration (Malpha=.86).

Middle school homophobic name-calling perpetration and victimization

The 10-item Homophobic Content Agent Target Scale was used to assess homophobic name-calling perpetration and victimization in middle school (Poteat and Espelage 2007). Students were asked how often in the past 30 days they directed homophobic epithets at other students (perpetration) or were targets of this language (victimization). For the perpetration scale, students were presented with the following stem “How many times in the last 30 days did YOU say homo, gay, lesbo, or fag to the following individuals?” Then they were presented the five items: (1) a friend, (2) someone you did not know well, (3) someone you did not like, (4) someone you thought was gay or lesbian, and (5) someone you did not think was gay or lesbian. Response options included “Never”, “1 or 2 times”, “3 or 4 times”, “5 or 6 times”, and “7 or more times” on a 5-point Likert scale (0–4). The five-item victimization scale consisted of the same items and response options, except that students were asked how often others (e.g., friends) called them homophobic epithets. Construct validity has been supported through exploratory and confirmatory analyses and the victimization scale correlates significantly with measures of bullying victimization (Poteat and Espelage 2007). Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were: .85 for Wave 1, .84 for Wave 2, .84 for Wave 3 and .86 for Wave 4 for perpetration (Malpha=.85), and .76 for Wave 1, .85 for Wave 2, .81 for Wave 3, and .82 for Wave 4 for victimization (Malpha=.81).

Sexual violence perpetration

An abbreviated six-item version of the American Association of University Women (AAUW) Sexual Harassment Survey was used to assess sexual violence perpetration during high school (Hill and Kearl 2011; Rinehart et al. 2017). Students were asked “During this school year, did you do any of the following to other students at school?” Participants were presented with six items on unwanted verbal sexual harassment (i.e., sexual comments, sexual rumor spreading, and showing sexual pictures), and forced sexual contact (i.e., touching in a sexual way, physically intimidating in a sexual way, and forcing to do something sexual). Response options were “Never”, “1 or 2 times”, “3 or 4 times”, “5 or 6 times”, and “7 or more times” on a 5-point Likert scale (0–4). We assessed the structure of this modified AAUW scale by splitting the sample into two separate subsamples, comparing fit statistics for a one-and two-factor solution in an exploratory factor analysis, and then fitting a confirmatory factor analysis to the best fitting model. Results of the exploratory factor analysis using the first subsample suggested that a one-factor solution fit the data best; all factor loadings ranged from .75 to .97 (CFI = 1.0, RMSEA = 0.00, X2 = 9.73(9), p = .76). Results from a confirmatory factor analysis with the second subsample indicated excellent model fit (CFI = 1.0, RMSEA = 0.01, X2 = 9.74(9), p = .37). Cronbach’s alpha was .76. Because the distribution for perpetration was heavily skewed, it was dichotomized into (1) ever engaging in sexual violence perpetration or (2) never engaging in sexual violence perpetration during the last two waves (high school). Of note, the same items were used to measure middle school sexual violence perpetration at each of two high school waves.

Data Analytic Plan

To address our hypotheses (both replication and extension) we ran a series of moderation and mediation models. All models were estimated using Mplus version 7.4 (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2012). Hypotheses are restated here, so the reader does not need to refer to these hypotheses earlier in this manuscript.

Hypothesis 1

To address our first hypothesis that the association between middle school bully perpetration and high school sexual violence perpetration would be moderated by middle school homophobic name-calling, we estimated a multi-group logistic regression model to directly replicate and expand findings from Espelage and colleagues (2015a). Multi-group models were used to estimate odds of sexual violence perpetration for males and females simultaneously. Specifically, we ran two models: the first was a main effects model assessing the effect of early middle school bullying perpetration on sexual violence in high school. The second model included an interaction term with bullying perpetration and homophobic name-calling perpetration. Each model controlled for sexual violence perpetration across three time points in middle school, maternal education (high school or less as reference group), and race (nonwhite as reference) at baseline. Unlike Espelage and colleagues (2015a), we also controlled for homophobic name-calling victimization at baseline. All variables were centered at the grand mean before interaction terms were entered into the model. We used the MODEL TEST command in Mplus to determine if parameter estimates were significantly different from each other across biological sex.

Hypothesis 2

For our second hypothesis that middle school homophobic name-calling victimization and perpetration would mediate the relationship between middle school bully perpetration and high school sexual perpetration, we ran a series of multi-variable mediation models (e.g., two mediating variables entered simultaneously). In these models the c path was represented by the main effect of early middle school bullying perpetration on high school sexual violence perpetration, the a paths (two a paths for each mediator) represented the effect of early middle school bullying perpetration on late middle school homophobic name-calling victimization (a1) and perpetration (a2) (controlling for early middle school homophobic name-calling), and the b paths represented the effect of late middle school homophobic name-calling victimization (b1) or perpetration (b2) on high school sexual violence perpetration (controlling for middle school sexual violence perpetration). To assess if homophobic name-calling victimization and perpetration mediated the effect of early bullying perpetration on high school sexual violence perpetration, we estimated bootstrapped (iterations = 5000) indirect effects models. Indirect effects are interpreted as the amount that the outcome variable (sexual violence perpetration) is expected to change as the independent variable (early middle school bullying perpetration) changes by one unit as a result of the independent variable on the mediator (later middle school homophobic name-calling victimization and perpetration). Partial mediation was assessed when the indirect effect was significant, but a reduction in the direct effect was evident but remained significant. In addition to controlling for early homophobic name-calling and sexual violence across three time points in middle school, we also controlled for biological sex, race, and maternal education at baseline.

Hypothesis 3

For our third hypothesis, we continued to extend the bullying sexual violence theory by estimating the multi-mediator models by biological sex, expecting significant indirect effects for males and not females. That is, the mediation model, described above, with both homophobic name-calling victimization and perpetration was estimated for males and females, simultaneously, using the multi-group method in Mplus. The multi-group method allows us to test for actual differences in both direct (e.g., early middle school bullying perpetration on high school sexual violence perpetration) and indirect (e.g., relationship mediated by either homophobic name-calling victimization or perpetration) effects across biological sex.

Missing Data

Missing data ranged from 4–25% across the study period. Mplus adjusts for missing data using a maximum likelihood estimator under the assumption that data are missing at random and uses all data that are available for each participant. Each continuous construct and co-variate were grand mean centered so that zero was functionally meaningful. Although there is no explicit method to formally test the missing at random (MAR) assumption without knowing the values of the missing dependent variable (i.e., sexual violence), we took various steps to examine missing data patterns (Enders 2010). We examined missing patterns by our co-variates for all variables used in our models. Compared with their male counterparts, females had significantly more missing data on sexual violence perpetration (X2 = 9.34, df = 1, p = .002). Further, nonwhite participants had significantly more missing data on early middle school bullying perpetration (X2 = 13.9, df = 1, p = .002), late middle school homophobic name-calling perpetration (X2 = 11.4, df = 1, p = .002), homophobic name-calling victimization (X2 = 10.8, df = 1, p = .002), and sexual violence perpetration in high school (X2 = 8.09, df = 1, p = .002). Additionally, individuals with higher SES had a larger proportion of missing data on sexual violence (X2 = 8.09, df = 1, p = .004), early middle school bullying perpetration (X2 = 13.55, df = 1, p = .001), and sexual violence perpetration in high school (X2 = 49.84, df = 1, p = .001). Finally, we found that individuals who reported higher levels of early middle school sexual violence perpetration had significantly more missing data on late middle school homophobic name-calling victimization (t = 10.5, df = 1006, p = .001). Because females, those reporting higher sexual violence perpetration in middle school, individuals identifying as nonwhite, and individuals with higher family SES had more missing data, we included biological sex, early middle school sexual violence perpetration, SES, and race/ethnicity in our co-variance matrix to aid in accounting for the missing data patterns when using the maximum likelihood estimator. As such, due to the moderate amount of missing data coupled with the large sample size, and adjusting for potential bias due to missingness on various demographic and individual variables, we believe the data are MAR.

Results

Prevalence Rates of Bullying, Homophobic Name-Calling Perpetration and Victimization, and Sexual Violence

At the simplest level of analysis, we dichotomized our variables of interest to understand how frequent youth were reporting perpetration and victimization across all variables used in the models. In early middle school, 30% of youth reported engaging in bullying perpetration. In late middle school 18.5 and 14% of youth reported homophobic name-calling perpetration and victimization, respectively. Finally, 34.5% of youth reported sexual violence perpetration in high school.

Bully-Sexual Violence Pathway Theory—Moderation by Homophobic Name-Calling (Hypothesis 1)

In Table 2, Model 1 presents the main effects of early middle school bullying and homophobic name-calling perpetration. For males, those who engaged in bullying behaviors in early middle school had 4.48 (95% CI [1.23, 9.17]) higher odds of engaging in sexual violence perpetration in high school. Further, males who engaged in homophobic name-calling perpetration in early middle school had 3.02 (95% CI [2.05, 4.46]) higher odds of engaging in sexual violence perpetration in high school. Similar results for main effects were found for females such that bullying (AOR = 1.93, 95% CI [1.15, 3.25]) and homophobic name-calling perpetration (AOR = 2.65, 95% CI [1.87, 3.50]) were associated with higher odds of perpetrating sexual violence in high school.

Table 2.

Multi-group logistic regression moderation models by biological sex

| Model 1

|

Model 2

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main effects

|

Homophobic name-calling perpetration moderation

|

|||

| Parameter | 95% CI | Parameter | 95% CI | |

| Males | ||||

| Threshold | 1.61 | (0.12) | 1.08 | (0.14) |

| Early bullying perpetration | 4.48 | [1.23, 9.17] | 10.6 | [5.01, 22.4] |

| Early homophobic name-calling perpetration | 3.02 | [2.05, 4.46] | 4.40 | [3.02, 6.38] |

| Early homophobic name-calling victimization | 0.77 | [0.42, 1.41] | 0.74 | [0.54, 1.01] |

| Bullying × homophobic name-calling perpetration | 0.37 | [0.26, 0.53] | ||

| Females | ||||

| Threshold | ||||

| Early bullying perpetration | 1.93 | [1.15, 3.25] | 5.13 | [2.41, 10.9] |

| Early homophobic name-calling perpetration | 2.65 | [1.87, 3.50] | 4.42 | [2.92, 6.70] |

| Early homophobic name-calling victimization | 0.70 | [0.50, 0.96] | 0.94 | [0.62, 1.48] |

| Bullying × homophobic name-calling perpetration | 0.60 | [0.32, 1.13] | ||

Note: Not all control variables are displayed for ease of reading. Each model controlled for sexual violence perpetration during middle school (three time points), race/ethnicity, and maternal education

Parameter [95% CI]

Early = Early middle school (5th, 6th, or 7th grade)

Bold = Confidence interval does not include 1

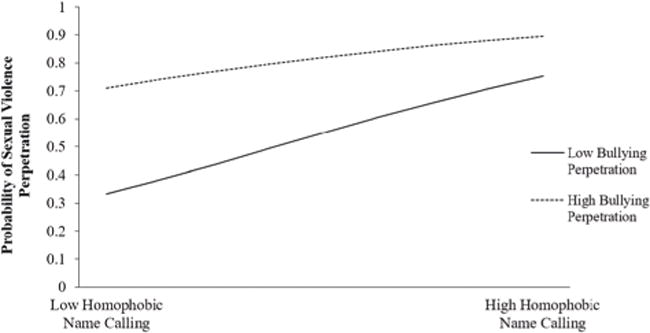

Results of our replication model (bully-sexual violence pathway moderated by homophobic name-calling; Table 2, Model 2) reveal a direct replication of Espelage et al. (2015a) such that interaction between bullying perpetration and homophobic name-calling perpetration predicting sexual violence perpetration was only significant for males (OR = .37, 95% CI [.26, .53]) but not for females (OR = .59, 95% CI [.32, 1.13]). Prototypical plots are displayed in Fig. 1 for males. As hypothesized, males who report greater bullying perpetration and high homophobic name-calling have the highest odds of perpetrating sexual violence in high school.

Fig. 1.

Interaction between bullying perpetration and homophobic name-calling perpetration among males. Low = 1 standard deviation below the mean, High = 1 standard deviation above the mean

Bully-Sexual Violence Pathway Theory Extended— Mediation by Homophobic Name-Calling (Hypothesis 2)

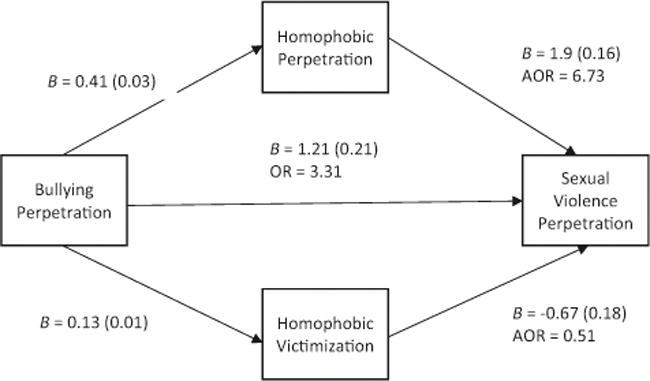

Extending prior research and theory, we sought to understand if late middle school homophobic name-calling perpetration and victimization acted as a mechanism between early middle school bullying perpetration and high school sexual violence perpetration. We estimated a multi-mediator model (e.g., both homophobic name-calling perpetration and victimization entered simultaneously; see Fig. 2). Table 3 displays path coefficients and odds ratios as well as indirect effects in the multi-mediator model. We found support for the indirect effect for homophobic name-calling perpetration (indirect effect = .78, 95% CI [.62, .94]), indicating a .78 increase in the odds of perpetrating sexual violence in high school for every unit increase in bullying perpetration via homophobic name-calling perpetration. Put differently, youth who engage in bullying perpetration in early middle school are more likely to engage in homophobic name-calling perpetration in late middle school (b = .41), and this increased homophobic name-calling perpetration is associated with a 6 times higher odds of ever perpetrating sexual violence in high school.

Fig. 2.

Multi-mediator model for homophobic name-calling perpetration and homophobic name-calling victimization. Note: Bullying perpetration is measured in early middle school (5th, 6th and 7th grade), homophobic name-calling perpetration and victimization are measured in late middle school (7th and 8th grade), and sexual violence perpetration is measured in high school (9th–11th Grade). Model controls for early middle school homophobic name-calling perpetuation, homophobic name-calling victimization, and sexual violence perpetration as well as participant age, sex, race, and maternal education. Solid lines indicate significant path

Table 3.

Multi-mediator indirect effect model

| Parameter [95% CI]

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

AOR [95% CI]

| |||

| Parm/AOR | 95% CI | ||

| A1 path (Bullying perpetration → Homophobic name-calling perpetration) | Parm | .41 | [.35, .46] |

| A2 path (Bullying perpetration → Homophobic name-calling victimization) | Parm | .13 | [.09, .14] |

| B1 path (Homophobic name-calling perpetration → Sexual violence perpetration) | Parm AOR |

1.91 6.73 |

[1.60, 2.21] [4.95, 9.15] |

| B2 path (Homophobic name-calling victimization → Sexual violence perpetration) | Parm OR |

−0.67 0.51 |

[−1.03, −.316] [0.36, 0.73] |

| C′ path (Bullying perpetration → Sexual violence perpetration) | Parm AOR |

1.20 3.31 |

[.795, 1.60] [2.21, 4.96] |

| Total effect | Parm | 1.20 | [0.79, 1.60] |

| Indirect effect 1 (Homophobic name-calling perpetration) | Parm | 0.78 | [0.62, 0.94] |

| Indirect effect 1 (Homophobic name-calling perpetration) | Parm | −0.08 | [0.12, −0.03] |

Parm parameter estimate, OR odds ratio

→ = direction of regression. Variables on the left side of the arrow are the independent variable, variables on the right of the arrow are the dependent variable

Bold = confidence interval does not include 1 (if Odds ratio) or 0 (if parameter)

However, contrary to our hypotheses for homophobic name-calling victimization, the indirect effect was significant but negative (indirect effect = −.08, 95% CI [−.12, −.03]). This indicates that the odds of being a sexual violence perpetrator in high school is lower when youth experience homophobic name-calling victimization. That is, early bullying perpetration is, in fact, associated with higher homophobic name-calling victimization; however, a unit increase in homophobic name-calling victimization is associated with a .51 decrease in the odds of perpetrating sexual violence in high school.

Bully-Sexual Violence Pathway—Sex Differences (Hypothesis 3)

We also estimated this multi-mediator model using multi-group functions to assess indirect effects for males and females (Hypothesis 3). Table 4 displays parameter and odds ratio estimates for the multi-group multi-mediator model. In general, results remain robust for homophobic name-calling perpetration with significant indirect effects for both males (indirect effect = 1.00, 95% CI [.63, 1.38]) and females (indirect effect = .66, 95% CI [.47, .85]). However, while the indirect effects remain negative for homophobic name-calling victimization for both males and females, it only remains significant for females (indirect effect = −.08, 95% CI [−.13, −.02]). Using the MODEL TEST command in Mplus, we directly compared indirect effect estimates to determine empirical differences across males and females. Results indicate that indirect effects for homophobic name-calling perpetration are significantly different from each other, with males having the larger effect (Wald test = 3.69, df = 1, p = .04). No differences were found for indirect effects of the homophobic name-calling victimization pathways (Wald test = .01, df = 1, p = .92), indicating that, while the effect emerges only for females, these effects are not significantly different from males.

Table 4.

Multi-group multi-mediator indirect effect model

| Males | Parameter/AOR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A1 path (Bullying perpetration → Homophobic name-calling perpetration) | Parm. | 0.49 | [0.41, 0.57] |

| A2 path (Bullying perpetration → Homophobic name-calling victimization) | Parm | 0.12 | [0.08, 0.15] |

| B1 path (Homophobic name-calling perpetration → Sexual violence perpetration) | Parm AOR |

2.00 7.40 |

[1.51, 2.49] [4.52, 12.11] |

| B2 path (Homophobic name-calling victimization → Sexual violence perpetration) | Parm AOR |

−0.69 0.50 |

[−1.34, −0.04] [0.25, 0.10] |

| C′ path (Bullying perpetration → Sexual violence perpetration) | Parm AOR |

1.11 3.03 |

[0.51, 1.73] [1.65, 5.46] |

| Total effect | Parm | 2.02 | [1.28, 2.76] |

| Indirect effect 1 (Homophobic name-calling perpetration) | Parm | 1.00 | [0.62, 1.38] |

| Indirect effect 2 (Homophobic name-calling victimization) | Parm | −0.09 | [−0.20, 0.01] |

| Females | |||

| A1 path (Bullying perpetration → Homophobic name-calling perpetration) | Parm | 0.36 | [0.29, 0.43] |

| A2 path (Bullying perpetration → Homophobic name-calling victimization) | Parm | 0.67 | [0.65, 0.70] |

| B1 path (Homophobic name-calling perpetration → Sexual violence perpetration) | Parm AOR |

1.82 6.19 |

[1.42, 2.22] [4.17, 9.19] |

| B2 path (Homophobic name-calling victimization → Sexual violence perpetration) | Parm AOR |

−0.66 0.52 |

[−1.09, −0.23] [0.31, 0.86] |

| C′ path (Bullying perpetration → Sexual violence perpetration) | Parm AOR |

1.27 3.59 |

[0.73, 1.82] [2.08, 6.18] |

| Total effect | Parm | 1.86 | [1.21, 2.53] |

| Indirect effect 1 (Homophobic name-calling perpetration) | Parm | 0.66 | [0.47, 0.85] |

| Indirect effect 2 (Homophobic name-calling victimization) | Parm | −0.08 | [−0.13, −0.02] |

Parm parameter estimated, AOR adjusted Odds ratio

→ = direction of regression. Variables on the left side of the arrow are the independent variable, variables on the right of the arrow are the dependent variable

Bold = confidence interval does not include 1 (if Odds ratio) or 0 (if parameter)

Sensitivity/Alternative Analyses

To assess the robustness of our hypotheses, we ran several alternative iterations of our models. Starting with the mediation modeling, in addition to assessing the multi-mediator model we also assessed each mediator (homophobic name-calling perpetration and homophobic name-calling victimization) separately. We began by estimating indirect effect models for homophobic name-calling perpetration. We found support for partial mediation for homophobic name-calling perpetration (indirect effect = .69, 95% CI [.53, .86]), which was supported in our more parsimonious multi-mediator model. Similarly, we estimated a model with just homophobic name calling victimization and found, like prior models, evidence of partial mediation (indirect effect = .06, 95% CI [.03, .09]) (see Supplemental Table 1, Supplemental Figs. 1, 2). To understand these processes, individually, in terms of biological sex, we next ran a multi-group mediation model where indirect effects for males and females were estimated for both homophobic name-calling perpetration and victimization (see Supplemental Table 2). In separate models, both males (indirect effect = .56, 95% CI [.41, .71]) and females (indirect effect = .77, 95% CI [.55, .99]) showed significant positive indirect effects for homophobic name-calling perpetration. However, unlike the multi-mediator model we found a significant indirect effect for homophobic name-calling victimization for males (indirect effect = .06, 95% CI [.02, .10]) but not females (indirect effect = .05, 95% CI [−.01, .12]). While this is contrary to the multi-mediator findings, we should also point out that the sign of the effect has flipped. That is, males who engage in early middle school bullying perpetration are more likely to experience homophobic name-calling victimization and, in turn, report engagement in sexual violence in high school.

Discussion

In this study, the Bully-Sexual Violence Pathway theory was tested across early to late adolescence in a longitudinal design. Originally, this theory posited that homophobic name-calling perpetration moderates the association between bullying perpetration and sexual violence perpetration among middle school youth. The current study examined whether homophobic name-calling perpetration continued to serve as a moderator between bullying and sexual violence perpetration as these youth entered high school. Also, homophobic name-calling perpetration and victimization were examined as mediators in the Bully-Sexual Violence Pathway. Findings suggest that male and female students who perpetrated bullying or homophobic name-calling in middle school had higher odds of perpetrating sexual violence in high school (direct effects). These results are consistent with our first hypothesis as well as findings from Espelage et al. (2015a) and support the applicability of the Bully-Sexual Violence Pathway theory into high school. Our second hypothesis was partially supported in that both late middle school homophobic name-calling perpetration and victimization mediated the relationship between early middle school bullying and sexual violence perpetration in high school, but victimization actually slightly reduced the odds of sexual violence perpetration. Findings related to our third hypothesis were mixed in that homophobic perpetration and victimization were found to be significant mediators between bullying and sexual violence perpetration for males and females, inconsistent with our hypothesis that these mediators would be found only for males.

Homophobic name-calling perpetration seems to have operated as we expected for males, and was also a significant mediator for females. We surmise that these findings are consistent with the Bully-Sexual Violence Pathway, where adolescents who bully are adding homophobic epithets to their repertoire as they develop, and these same students are likely to perpetrate sexual violence as they transition into high school. Homophobic name-calling may be a way of setting rules for what constitutes acceptable masculinity (Phoenix et al. 2003; Slaatten et al. 2014; Stoudt 2006) and reinforces an environment where sexual violence emerges (Birkett and Espelage 2015; Herek 2000; Kimmel and Mahler 2003; Poteat et al. 2011; Theodore and Basow 2000). We anticipated a relationship between homophobic name-calling victimization and sexual violence perpetration based upon the work of others such as Messerschmidt (2000), which may shed light on males’ experiences with homophobic name-calling victimization and how it could relate to later sexual violence perpetration for some youth, although this was not borne out in the present study. In his book, Messerschmidt describes the life histories of three adolescent males who perpetrated sexual violence. In all cases, the males experienced bullying victimization (e.g., called a wimp) and homophobic name-calling victimization in school (e.g., called a fag). They described their subsequent sexual violence perpetration as a way to feel powerful in one part of their life given they felt powerless at school (and in two cases, they were also abused and powerless at home). Sexual violence was a way to express masculinity and redeem power that they lost in other parts of their life (Messerschmidt 2000). In this way, sexual violence was not simply “the personification of male power” (Messerschmidt 2000, p. 100), it was a way to regain power lost from the ongoing victimization they experienced. It could be that sexual violence is committed for both reasons (i.e., to regain power or maintain power), depending on whether male adolescents had been victimized by or perpetrated either bullying or homophobic name-calling. It is interesting that homophobic name-calling victimization slightly decreased sexual violence perpetration in females even after previous bullying perpetration. We anticipate that being victimized by homophobic epithets may not influence females to be sexually aggressive in the same way or for the same reasons as male adolescents. Also, this finding could be associated with the type of victimization that boys and girls experience. As girls are more likely to be relationally victimized and boys more likely to be physically victimized and be the targets of homophobic name-calling (Espelage et al. 2014), boys’ aggression might escalate more than girls.

The findings from this study extend our knowledge of the role of homophobic name-calling in understanding the relationship between bullying and sexual violence. We extended the work of Espelage and colleagues (2015a) by demonstrating longitudinally that homophobic name-calling not only moderates the relationship between bullying and sexual violence perpetration as youth transition into high school, but it also mediates the relationship. Understanding how bullying perpetration and homophobic name-calling interact during early adolescence to predict later sexual violence perpetration provides valuable information about the timing and content of sexual violence prevention efforts. Primary prevention efforts for sexual violence would be best if they started before high school and incorporated content related to bullying and homophobic name-calling, as this study suggests homophobic name-calling may be the glue that connects bullying and sexual violence perpetration. As part of a comprehensive and developmental approach to sexual violence prevention, bullying prevention efforts are important in early middle school and would be better timed in elementary school for primary prevention, given that this and other studies have shown that bullying behavior is already prevalent in middle school (Robers et al. 2015), particularly among sexual and gender minority youth (Gruber and Fineran 2008; Kosciw et al. 2016). Further, while all 50 states have anti-bullying laws, only 19 states have laws that prohibit bullying on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity (Cornell and Limber 2015). When schools have comprehensive anti-bullying or harassment policies that explicitly protect sexual and gender minorities, staff are more likely to intervene in instances of homophobic name-calling (Kosciw et al. 2016), which, as borne out by this research, would benefit all youth, not solely sexual and gender minority (SGM) youth.

Ongoing prevention programming throughout middle school and during the transition to high school seems to be critical to prevent middle school aggression as well as sexual violence in high school. As outlined in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s STOP SV: A Technical Package to Prevent Sexual Violence (Basile et al. 2016), there are numerous approaches with evidence of effectiveness in preventing sexual violence, such as social emotional learning (SEL) approaches that focus on enhancing adolescents’ skills around communication, problem-solving, empathy, and conflict management. For example, Second Step: Student Success through Prevention, is a SEL program for middle school students that also includes content related to bullying and homophobic name-calling. A rigorous multi-site evaluation found Second Step to be effective in reducing homophobic name-calling victimization by 56% and sexual violence perpetration by 39% in one of the two states in which it was implemented (Espelage et al. 2015b). The results of the current study suggest that programs such as Second Step may disrupt the cycle of adolescent aggression that results in later sexual violence perpetration in high school. More research is needed to evaluate additional promising sexual violence prevention programs that address bullying and homophobic name-calling in early adolescence, particularly studies that include SGM youth.

A few limitations are worth noting. First, we used an abbreviated version of AAUW to measure sexual violence which was limited to sexual violence of “students at school”, so while the scale had high internal consistency, we are likely underestimating the prevalence of sexual violence among this sample. Second, this study did not include an examination of the sexual orientation of students, nor did it differentiate between same and cross-sex bullying, homophobic name-calling, or sexual violence perpetration. Same-sex vs. cross-sex perpetration may be better analyzed separately in the future as these are distinct phenomena, and cross-sex perpetration, but not same-sex perpetration, has been shown to increase in frequency as youth age (McMaster et al. 2002). Further, research that explores if or how the patterns found in this study vary for sexual and gender minority youth would be beneficial to the field. In addition, the analytic technique used in this study only examined between-person differences and not within-person variation and change over time. This would be a good next step for future research. Finally, it would be worthwhile to examine the role traditional masculinity plays in the patterns uncovered in this study, given previous studies that have found that adhering to traditional masculinity ideologies is associated with greater homophobic name-calling and gender-based aggression (Birkett and Espelage 2015; Tucker et al. 2016). Continued research including traditional masculinity may help explain why and how homophobic name-calling is so important in understanding the link between bullying and later sexual violence perpetration.

Conclusion

This study adds to a growing body of literature on sexual violence among adolescents. At the most basic descriptive level, bullying, homophobic name-calling, and sexual violence perpetration occurs with regular frequency and should be addressed directly in prevention programs during middle school. Also, this study was the first to examine the longitudinal associations among bullying and gender-based aggression across early to late adolescence. Bullying among middle school youth and its association with later sexual violence perpetration during the high school years was found to be moderated and mediated by homophobic name-calling. Students who bully their peers were more likely to report sexually harassing their peers across early to late adolescence when they had engaged in homophobic name-calling. These findings suggest that prevention of sexual violence perpetration among high school students should begin to address bullying and homophobic name-calling during the middle school years.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Middle school data in this manuscript were drawn from a grant from the CDC (1U01/CE001677) to D.E. (PI). High school data in this manuscript were drawn from a grant from the National Institute of Justice (Grant #2011-90948-IL-IJ) to D.E. (PI). Analyses and manuscript preparation was supported through an inter-personnel agency agreement (IPA) between University of Florida (Espelage) and the CDC (17IPA1706096).

Biographies

Dorothy L. Espelage is a Professor of Psychology at the University of Florida. Her research interests include bullying, sexual violence, dating violence, and school-based Interventions.

Kathleen C. Basile is a Senior Scientist in the Division of Violence Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Her research interests include sexual violence and intimate partner violence definitions, etiology, and evidence-based prevention strategies.

Ruth W. Leemis is a Behavioral Scientist in the Division of Violence Prevention at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Her research interests include the primary prevention of sexual violence, sex trafficking, and suicide as well as identification of effective crosscutting violence prevention strategies that incorporate a shared risk and protective factor approach.

Tracy N. Hipp is an ORISE Research Fellow in the Division of Violence Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Her research interests include sexual violence, gender-based violence, polyvictimization, LGBTQ violence and health disparities.

Jordan P. Davis is an Assistant Professor in the Suzanne Dworak-Peck School Social Work, Department of Children Youth and Families at the University of Southern California. His research interests include intersection between development and intervention outcomes among at risk youth in substance use disorder treatment; early childhood trauma and current victimization on stress response systems; personality assessment across clinical and developmental samples and how it relates to intervention outcomes and psychosocial development.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-018-0827-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Authors’ Contributions D.L.E. conceptualized and designed the study, collected the data, maintained ethics board approval, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the entire manuscript; K.C.B. helped conceptualize and design the study, drafted the initial discussion, edited the initial introduction, and reviewed and revised the entire manuscript; R.W.L. and T.N.H. helped conceptualize and design the study, edited the initial Introduction, helped draft the initial discussion, and reviewed and revised the entire manuscript; J.P.D. helped con-ceptualize and design the study, carried out the analyses, wrote the methods and results sections, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Sharing Declaration This manuscript’s data will not be deposited.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval This study was approved by the University of Illinois Institutional Review Board. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the youth self-report and 1991 profile. Burlington: Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Basile KC, DeGue S, Jones K, Freire K, Dills J, Smith SG, et al. STOP SV: a technical package to prevent sexual violence. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Basile KC, Espelage DL, Rivers I, McMahon PM, Simon TR. The theoretical and empirical links between bullying behavior and male sexual violence perpetration. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2009;14(5):336–347. [Google Scholar]

- Basile KC, Smith SG, Breiding MJ, Black MC, Mahendra RR. Sexual violence surveillance: uniform de finitions and recommended data elements, version 2.0. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Birkett M, Espelage DL. Homophobic name-calling, peer-groups, and masculinity: the socialization of homophobic behavior in adolescents. Social Development. 2015;24:184–205. doi: 10.1111/sode.12085. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caryle KE, Steinman KJ. Demographic differences in the prevalence, co-occurrence and correlates of adolescent bullying at school. Journal of School Health. 2007;77:623–629. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00242.x. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornell D, Limber SP. Law and policy on the concept of bullying at school. American Psychologist. 2015;70(4):333–343. doi: 10.1037/a0038558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK. Applied missing data analysis. New York, NY: Guilford; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Espelage DL, Basile KC, Hamburger ME. Bullying experiences and co-occurring sexual violence perpetration among middle school students: shared and unique risk factors. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2012;50:60–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohea. lth.2011.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espelage DL, Basile KC, Rue DL, Hamburger ME. Longitudinal associations among bullying, homophobic teasing, and sexual violence perpetration among middle school students. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2015a;30(14):2541–2561. doi: 10.1177/0886260514553113. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espelage DL, Holt ML. Bullying and victimization during early adolescence: peer influences and psychosocial correlates. Journal of Emotional Abuse. 2001;2(3):123–142. doi: 10.1300/J135v02n02_08. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Espelage DL, Hong JS, Rinehart S, Doshi N. Understanding types, locations, & perpetrators of peer-to-peer sexual harassment in US middle schools: a focus on sex, racial, and grade differences. Children and Youth Services Review. 2016;71:174–183. [Google Scholar]

- Espelage DL, Hong SJ, Merrin GJ, Davis JP, Rose CA, Little TD. A longitudinal examination of homophobic name-calling in middle school: bullying, traditional masculinity, and sexual harassment as predictors. Psychology of Violence. 2017 doi: 10.1037/vio0000083. . [DOI]

- Espelage DL, Holt MK, Henkel RR. Examination of peer-group contextual effects on aggression during early adolescence. Child Development. 2003;74:205–220. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00531. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espelage DL, Low S, Rao MA, Hong JS, Little TD. Family violence, bullying, fighting, and substance use among adolescents: a longitudinal mediational model. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2014;24:337–349. doi: 10.1111/jora.12060. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Espelage DL, Van Ryzin M, Low S, Polanin J. Clinical trial of Second Step© middle-school program: impact on bullying, cyberbullying, homophobic teasing & sexual harassment perpetration. School Psychology Review. 2015b;44(4):464–479. doi: 10.17105/spr-15-0052.1. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gladden RM, Vivolo-Kantor AM, Hamburger ME, Lumpkin CD. Bullying surveillance among youths: uniform definitions for public health and recommended data elements, version 1.0. 2014 https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/bullying-definitions-final-a.pdf.

- Gruber JE, Fineran S. Comparing the impact of bullying and sexual harassment victimization on the mental and physical health of adolescents. Sex Roles. 2008;59(1–2):1. [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM. The psychology of sexual prejudice. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2000;9(1):19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Hill C, Kearl H. Crossing the line: sexual harassment at school. Washington, DC: American Association of University Women; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hodges EVE, Perry DG. Personal and interpersonal antecedents and consequences of victimization by peers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;76(4):677–685. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.76.4.677. http://doi.org.proxy2.library.illinois.edu/10.1037/0022-3514.76.4.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, McManus T, Harris WA, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Surveil Summ 2016. 2016;65(SS-06):1–174. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6506a1. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/ss/pdfs/ss6506.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel MS, Mahler M. Adolescent masculinity, homophobia, and violence: random school shootings, 1982–2001. American Behavioral Scientist. 2003;46(10):1439–1458. [Google Scholar]

- Kosciw JG, Diaz EM. The 2005 National School Climate Survey: the experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth in our nation’s schools. New York, NY: Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kosciw JG, Greytak EA, Giga NM, Villenas C, Dani-schewski DJ. The 2015 National School Climate Survey: the experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer youth in our nation’s schools. New York, NY: GLSEN; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- McMaster LE, Connolly J, Pepler D, Craig WM. Peer to peer sexual harassment in early adolescence: a developmental perspective. Development and Psychopathology. 2002;14(1):91–105. doi: 10.1017/s0954579402001050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messerschmidt JW. Nine lives: adolescent masculinities, the body, and violence. Boulder, CO: Westview Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer EJ. Gendered harassment in secondary schools: understanding teachers’ (non) interventions. Gender and Education. 2008;20:555–570. doi: 10.1080/09540250802213115. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller S, Williams J, Cutbush S, Gibbs D, Clinton-Sherrod M, Jones S. Dating violence, bullying, and sexual harassment: longitudinal profiles and transitions over time. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2013;42(4):607–618. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-9914-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modecki KL, Minchin JM, Harbaugh AG, Guerra NG, Runions KC. Bullying prevalence across contexts: a meta-analysis measuring cyber and traditional bullying. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2014;55:602–611. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.06.007. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus statistical analysis with latent variables: User’s guide. Los Angeles, CA: Authors; 1998–2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nansel TR, Overpeck M, Pilla RS, Ruan WJ, Simons-Morton B, Scheidt P. Bullying behaviors among US youth: prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;285(16):2094–2100. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.16.2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olweus D, Limber S, Mahalic SF. Bullying prevention program. Boulder, CO: Center for the Study and Prevention of Violence, Institute of Behavioral Science, University of Colorado Boulder; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe CJ. What if a guy hits on you? Intersections of gender, sexuality, and age in fieldwork with adolescents. In: Best AL, editor. Representing youth: methodological issues in critical youth studies. New York, NY: New York University Press; 2007. pp. 226–249. [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini AD. A longitudinal study of heterosexual relationships, aggression, and sexual harassment during transition from primary school through middle school. Applied Developmental Psychology. 2001;22:119–133. [Google Scholar]

- Pepler DJ, Craig WM, Connolly JA, Yuile A, McMaster L, Jiang D. A developmental perspective on bullying. Aggressive Behavior. 2006;32:376–384. doi: 10.1002/ab.20136. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phoenix A, Frosh S, Pattman R. Producing contradictory masculine subject positions: narratives of threat, homophobia and bullying in 11–14 year old boys. Journal of Social Issues. 2003;59(1):179–195. [Google Scholar]

- Plummer DC. The quest for modern manhood: Masculine stereotypes, peer culture and the social significance of homophobia. Journal of Adolescence. 2001;24(1):15–23. doi: 10.1006/jado.2000.0370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poteat VP, DiGiovanni CD. When biased language use is associated with bullying and dominance behavior: the moderating effect of prejudice. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2010;39(10):1123–1133. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9565-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poteat VP, Espelage DL. Exploring the relation between bullying and homophobic verbal content: the Homophobic Content Agent Target (HCAT) scale. Violence and Victims. 2005;20(5):513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poteat VP, Espelage DL. Predicting psychosocial consequences of homophobic victimization in middle school students. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2007;27:175–191. doi: 10.1177/0272431606294839. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Poteat P, Espelage DL, Green H. The socialization of dominance: peer group contextual effects on heterosexist and dominance attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;92(6):1040–1050. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.6.1040. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poteat VP, Kimmel MS, Wilchins R. The moderating effects of support for violence beliefs on masculine norms, aggression, and homophobic behavior during adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2011;21(2):434–447. [Google Scholar]

- Poteat VP, O’Dwyer LM, Mereish EH. Changes in how students use and are called homophobic epithets over time: patterns predicted by gender, bullying, and victimization status. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2012;104:393–406. doi: 10.1037/a0026437. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Poteat VP, Rivers I. The use of homophobic language across bullying roles during adolescence. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2010;31:166–172. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2009.11.005. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Poteat VP, Vecho O. Who intervenes against homophobic behavior? Attributes that distinguish active bystanders. Journal of School Psychology. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2015.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rinehart SJ, Espelage DL. A multilevel analysis of school climate, homophobic name-calling, and sexual harassment victimization/perpetration among middle school youth. Psychology of Violence. 2016;6:213–222. doi: 10.1037/a0039095. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rinehart SJ, Espelage DL, Bub KL. Longitudinal effects of gendered harassment perpetration and victimization on mental health outcomes in adolescence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2017 doi: 10.1177/0886260517723746. Online publication. . [DOI] [PubMed]

- Robers S, Zhang A, Morgan RE. NCES 2015-072/NCJ 248036. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics; 2015. Indicators of school crime and safety: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Slaatten H, Anderssen N, Hetland J. Endorsement of male role norms and gay-related name-calling. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2014;15(3):335. [Google Scholar]

- Stein ND. Sexual harassment in K-12 schools: the public performance of gendered violence. Harvard Educational Review. 1995;65:145–162. [Google Scholar]

- Stein N, Marshall NL, Tropp LR. Secrets in public: sexual harassment in our schools. Wellesley, MA: Wellesley College Center for Research on Women; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Stoudt BG. “You’re either in or you’re out” school violence, peer discipline, and the (re) production of hegemonic masculinity. Men and Masculinities. 2006;8(3):273–287. [Google Scholar]

- Theodore PS, Basow SA. Heterosexual masculinity and homophobia: a reaction to the self? Journal of Homosexuality. 2000;40(2):31–48. doi: 10.1300/J082v40n02_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JS, Ewing BA, Espelage DL, Green HD, Jr, de lH K, Pollard MS. Longitudinal associations of homophobic name-calling victimization with psychological distress and alcohol use during adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2016;59(1):110–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.03.018. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner HA, Finkelhor D, Hamby SL, Shattuck A, Ormrod RK. Specifying type and location ofpeer victimization in a national sample of children and youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2011;40(8):1052–1067. doi: 10.1007/s10964-011-9639-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Education, Office of Civil Rights. Revised sexual harassment guidance: harassment of students by school employees, other students, or third parties: title IX. 2001 http://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/shguide.html.

- Ybarra M, Espelage DL, Mitchell KJ. Differentiating youth who are bullied from other victims of peer-aggression: the importance of differential power and repetition. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2014;55:293–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.02.009. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.